- Department of History, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

In recent decades, various initiatives have been established to support the professional development of teachers and their school context. In some cases, they provide teachers the opportunity to combine their profession with doctoral studies. This paper explores factors that support teacher research as part of school practice and academia. It takes the perspective of teachers as a starting point and examines their experiences through the lens of the learning potential of boundaries. A review of empirical studies was conducted from various international educational contexts through an integrative literature review. The selected empirical studies (n = 13) contributed to a better understanding of the complexity of this undertaking, and three themes were generated as main factors: (1) a stimulating school culture; (2) engaging with the academic community; (3) and aligning the research design with the practitioners’ needs.

1 Introduction

It has long been acknowledged that for teachers, conducting research contributes to professional development (Vulliamy and Webb, 1992; Jablonski, 2001; Leuverink and Aarts, 2018). In recent decades, various individual or collaborative initiatives have been established to support professional development of teachers and their school context (Sjölund et al., 2022; Zeichner, 2003). These initiatives primarily relied on a university-school partnership (Arhar et al., 2013; Aydin et al., 2018). One of the ways the dialog between a university and a school can take shape is through doctoral programs for teachers (Burgess et al., 2006; Wildy et al., 2015).

Initiatives that provide teachers with the opportunity to conduct doctoral studies go by a variety of names. Internationally, they are mostly referred to as professional doctorates (Scott et al., 2004; Wadham and Parkin, 2017). In higher education, these programs are gaining influence and becoming common qualifications for both pre-service and in-service professionals (Wildy et al., 2015). They are considered more relevant to contemporary society compared to traditional PhDs, which tend to focus more on developing professional researchers and contributing to knowledge production (Bourner et al., 2001; Jones, 2018).

More specifically, for the field of education, the degree of educational doctorate (EdD) was set up in the light of continuing professional development purposes for professionals who wish to be involved in additional doctoral studies (Burgess et al., 2006). As a professional practice degree, the EdD mostly requires that its participants possess prior professional experience, ensuring that the research is grounded in practical and real-world contexts. These participants are not limited to teachers; they often include school leaders, administrators, school social workers or psychologists, and educational researchers. Moreover, while the doctoral study can be considered a part-time position not all participants receive a financial compensation. In some cases, participants even continue to work full-time along their doctoral studies. Consequently, the implementation and participant experience of EdD programs vary significantly across higher education institutions worldwide.

In the United States, where the EdD has long been established, these programs have also faced considerable criticism (Levine, 2005; Shulman et al., 2006). According to Shulman et al. (2006), for example, the research skills learned during the program were not sufficiently aligned with the practice context and mostly failed to meet the needs of the targeted population. This criticism prompted a comprehensive redesign, culminating in the establishment of the Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (CPED) in 2007, which aimed to transform the EdD programs by better aligning them with the needs of practitioners. Although the EdD and the PhD have different purposes, the operational distinction between both programs in higher education is often very limited (Foster et al., 2023).

In the present, the success of EdD programs can differ according to the context, and it appears these programs seem to be predominantly anchored in the Anglo-world. Nevertheless, even in international terms, it remains mostly unclear what support these teachers need during their challenging dual situation (Lindsay et al., 2018). In this respect, Armsby et al. (2018) found that professional doctorate courses are usually designed by universities while the input of relevant stakeholders from the practitioner’s side is lacking. Moreover, Cochran-Smith and Lytle (2009, p. 112) point to the fact that practitioner research is not commonly integrated into the content of the courses taught at universities in teacher or doctoral education, as it “disrupts university culture by challenging the existence of a knowledge base for practice that has been constructed almost entirely by university-based researchers.”

In general, there seems little guidance for universities in the peer-reviewed literature to support this diverse group of educational professionals doing doctoral studies. However, it can be assumed that, particularly for teachers in this group, the challenge of combining school-based and university-based contexts is substantial at an individual level. In some cases, for example, the teachers are also expected to perform other tasks at the university, such as assisting in teacher training. These situations raise issues of practicality and methodology considering the alignment of both activities.

The main purpose of this paper is to offer an overview of factors conducive for teachers active in primary or secondary education while doing doctoral studies. It aims to map relevant research findings through an integrative literature review. The literature review will contribute to a better alignment of school-based and university-based contexts and their institutionalized traditions and practices.

2 Theoretical background

A considerable body of literature reports on or advocates for collaborations between schools and academic institutions (Lewis, 2013; Sjölund et al., 2022). Many of these collaborations are set up in light of initial teacher education, where field schools serve as training grounds for pre-service teachers to engage in authentic learning activities under the guidance of experienced teachers. However, in these partnerships, pre-service teachers seem to face a variety of cultural differences, such as contrasting expectations or demands, between the university-based program and practice in the field schools (Labaree, 2003; Smedley, 2001; Wang et al., 2022; White et al., 2022). Moreover, Beauchamp and Thomas (2011) investigated the difficulties of new teachers entering the profession after their initial teacher training and emphasized the importance of providing sufficient support during the transition. It can be assumed that in-service teachers that take on a role in both a university and a school simultaneously as part of doctoral programs encounter similar discontinuities. Nevertheless, publications by these teachers mainly focus on the results of their research. Arguably, less attention in the research output is being paid to the organizational and methodological aspects of combining two contexts. Reports where these teachers are a subject of study themselves are limited and mostly tend to focus on the motivational factors of the undertaking (Kowalczuk-Waledziak et al., 2017). To a lesser extent, literature has emerged in recent years that involves studies that serve an introspective aim of teachers during their doctoral research (Russo, 2020; Savva and Nygaard, 2021; Smith, 2022).

These studies on in-service teachers conducting doctoral research account of two units of work that hold different kinds of engagements. In schools, for example, teachers are expected to develop and provide a series of lessons during the semester while also investing time in extracurricular activities or supervising the playground. Although a considerable body of more general research (Darling-Hammond, 2017; Labone and Long, 2016; White, 2021) points to the need for supportive conditions to allow teacher research, schools seem to lack such a stimulating culture. In academia, by contrast, it can be argued that the faculty staff is responsible for conducting research as its main focus, while education is assigned a less important role (Juhl and Buch, 2019). For this reason, one of the main challenges seems to be the dual context of the teacher-researchers. While schools mostly lack a tradition of research, universities, on the other hand, excel in scholarly and innovative work. Although both contexts can be understood as highly demanding, they differ significantly (Labaree, 2003; Cochran-Smith and Lytle, 2009).

Teachers doing doctoral studies continuously need to go back and forth between schools and university settings. In doing so, they may encounter or experience various difficulties. For example, in her reflective account, Smith (2022) described the challenging situation of pursuing an EdD and indicated that embracing a suitable methodological approach is beneficial to succeed. Overcoming differences between both contexts (school and academia) may contribute to the professional development of educators during doctoral research (Burton, 2020; Jablonski, 2001) and is also believed to help to bridge the research-practice divide (Levin, 2013). In this regard, organizations or individuals positioned between research and practice are often labeled as knowledge mobilizers, research brokers, or boundary spanners (Farley-Ripple et al., 2018; Malin and Brown, 2020). Although what actually happens in the space between research and practice remains generally vague in the literature, it is proposed that such organizations or individuals should have a deep contextual understanding of both research and practice (Rycroft-Smith, 2022). Considering primary or secondary school teachers doing doctoral studies, little is known about how they organize their different activities and which strategies they use to achieve their goals. How this dual situation at the individual level should take shape and which factors prove to be conducive remains mostly unclear or, at least, is not presented in an integrative way.

This paper explores active primary and secondary teachers conducting doctoral research in terms of boundaries between school-based and university-based contexts. In doing so, it draws on the influential literature review of Akkerman and Bakker (2011, p. 133) in the field of educational theory that defines a boundary in learning situations as “a sociocultural difference leading to discontinuity in action or interaction.” This delineation of the boundary concept is grounded in dynamism in a way that the potential of overcoming such a boundary in social and cultural practices is stressed. Moreover, Akkerman and Bakker (2011, p. 153) propose to shift the focus from the systemic differences across contexts to “a micro-perspective, describing who experiences a particular discontinuity in which interactions or actions. In this way, it becomes possible to study how sociocultural differences play out in and are being shaped by knowledge processes, personal and professional relations, and mediations, but also in feelings of belonging and identities.” Therefore, this paper takes the perspective of active teachers during doctoral studies as a starting point and examines their experiences through the lens of the learning potential of boundaries.

Scholars often conceptualized the dichotomy between two contexts in terms of boundaries. However, based on a literature review, Akkerman and Bakker (2011) emphasize that, in these studies, boundary as a term is not always well defined. For them, boundaries are more than just barriers, but offer the potential for learning as well. Considering the scope of this paper, these boundaries can be experienced by teachers, active in more than one context sharing the same institutionalized practices or traditions. In this respect, there has been an increase in research attention during recent years on ways to overcome such boundaries across contexts. Wang et al. (2022), for example, investigated the learning of a pre-service teacher, mainly focusing on the experiences she encountered going back and forth between the authentic learning activities at the field school and the teacher education program at the university. Their findings indicated that the recursive movement across these boundaries supported the professional growth of the pre-service teacher by fostering meaningful connections between the knowledge and experiences gained in both settings. However, they argued that sufficient communication between the field school and the university is crucial for this process to be successful.

According to Akkerman and Bakker (2011), the concepts of “boundary crossing” and “boundary objects” are mostly employed in grasping the learning potential of such sociocultural differences. In general terms, boundary crossing originates from studies focused on learning at the workplace and indicates the attempt of professionals when establishing bridges between work contexts (Suchman, 1994; Engestrom et al., 1995). Bakker and Akkerman (2013, p. 225) describe boundary crossing as “the efforts by individuals or groups at boundaries to establish or restore continuity in action or interaction across practices.” The concept of boundary objects draws on the conceptualization of Star and Griesemer (1989) and refers to resources that facilitate the connection between two, often related, sociocultural practices. For instance, Anagnostopoulos et al. (2007) employed the concept to bridge university teacher training and the actual teaching in classroom practice drawing on the creation of educational tools that can be used in both contexts, such as a subject-specific rubric. Although the literature on how this can be done in practical terms remains scarce, theoretically, both concepts (boundary crossing and boundary objects) seem to play a crucial role in narrowing the divide between a university-based context engaged in research and a school-based context focused on professional practice.

3 Research question and aim

Taking the background context in mind and informed by the theoretical framework, the following research question was formulated:

Which factors support teachers as educational professionals doing doctoral studies?

As the literature review presented in this paper is exploratory, it does not seek to build an all-encompassing model to overcome the complexity of the challenges ahead. Rather the main aim lies in setting up an evidence-informed practice for teachers involved. Considering this specific teacher’s point of view, the conclusions in this paper will mainly focus on strategies for facilitating the professional development of teachers. The findings of this study may also contribute to the growing international body of literature concerned with the learning of a diverse group of educational professionals doing doctoral studies.

4 Materials and methods

Based on the distinction of Snyder (2019) and the purposes of Torraco (2016a), the integrative literature review was chosen as the most appropriate strategy. The main reason for this is to be found in the outcome. Integrative literature reviews draw on empirical findings collected from (a selection of) qualitative studies and, therefore, provide a deep and rich understanding of an emerging topic (Elsbach and van Knippenberg, 2020). Considering the aim of this paper, the experiences of the teachers doing doctoral studies will form an empirical basis. More than a synthesis, the outcome must provide a new and informed perspective on the initial research problem. Therefore, it should transcend a rather descriptive nature. The integrative literature review allows new perspectives to be developed (Torraco, 2016b). Nevertheless, this requires a thorough theoretical insight of the researcher and, subsequently, a transparent and rigorous research methodology (Snyder, 2019). To protect against the potential bias that can occur, a systematic data analysis is needed.

This literature review follows the research methodology described by Whittemore and Knafl (2005). Their method distinguishes five key stages: (1) identifying the problem, (2) searching the literature, (3) evaluating the data, (4) analysing the data, and (5) presenting the data. While the first stage has been outlined in the introduction, the following three stages are included in the method section. The last stage is, given its importance, elaborated in a separate results section. However, regarding this presentation stage, Torraco (2016b) differentiates between analysing and synthetizing data. The former, on the one hand, is used to critically dismantle and evaluate the various aspects of a particular topic. The latter, on the other hand, is needed in order to construct new perspectives. Therefore, considering the purpose of this paper, the data analysis will be followed by a synthesis as part of the concluding discussion.

4.1 Search methods

The search was performed in two electronic databases: Web of Science (WOS) and Scopus. The databases are multidisciplinary and easily accessible in performing a structured search. Although Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) has the advantage of being a discipline-specific database, it was left out due to its limited advanced search options. Google Scholar was excluded due to its wide coverage in combination with its inherent limitations regarding the filter options. It does not, for example, allow filtering on a specific discipline, such as education.

To address the ambiguity between the EdD and the PhD in higher education, a broad search should be favored in order to manually select on relevancy of the programs in light of the research question. Moreover, this paper adopts the perspective of teachers that remain active in their school practice during doctoral studies. Therefore, the integration of their research findings, along with the interplay between their practical experiences and research outcomes, is crucial. Accordingly, the search should specifically focus on teachers who characterize their work as teacher research. Consequently, the two databases were inquired using the keywords “teacher research*” AND “PhD” OR “EdD” OR “doctoral degree” OR “postgraduate studies” OR “professional doctorate.” The actual search was conducted on September 15, 2022.

4.2 Screening criteria

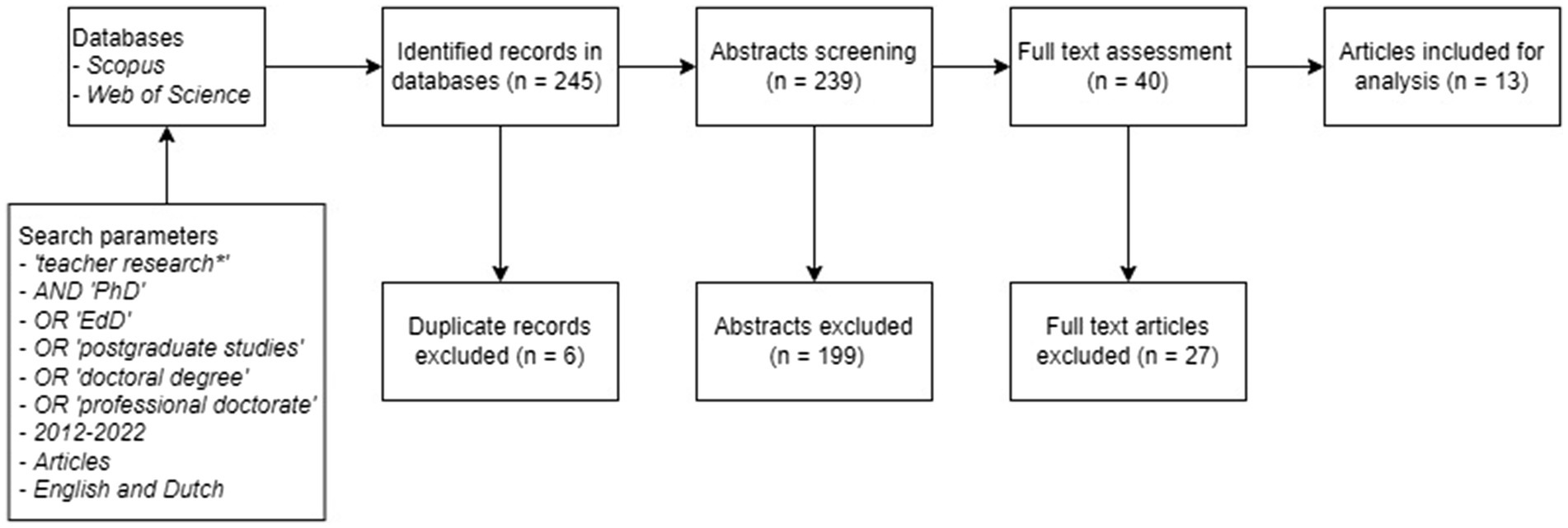

The inquiry in Scopus searched within article titles, abstracts, and keywords, while the WoS search focused solely on abstracts. Moreover, the latter was limited to the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and filtered on the category “Education Educational Research.” Subsequently, the scope needed to be further narrowed. Therefore, for reasons of academic validity, the review was limited to peer-reviewed articles only. Moreover, as it concerns a relatively young and emerging research topic, only articles published during the last decade (2012–2022) were taken into account. Finally, the language filter was set to English and Dutch. The search query identified a total of 245 papers, of which 225 were in WoS and 20 in Scopus. In this initial sample, 6 duplicate records were removed, leaving a list of 239 papers.

In the next step, due to the specificity of the topic, the abstracts of the 239 papers were screened manually. To be included, they needed to provide a clear description of the participants’ dual role as both part-time teachers in a school setting and doctoral researchers at a university. When in doubt (e.g., ambiguous descriptions), the article was included for the next stage of full-text assessment. Only articles where teacher researchers acted as participants in empirical studies were included. The screening focused on results in the context of primary and secondary education. Empirical findings of teaching activities in higher education (e.g., university) in combination with a PhD program were left out. Based on the results of Pratt et al. (2015), it can be assumed that, in these cases, research and teaching contexts seemed too close together to be assessed as relevant in light of the research question. The manual selection process did not filter on the level of teaching subjects or research topics, as the research question is focused on challenging aspects of combining two contexts. The concepts of “boundary crossing” and “boundary objects” were not used as inclusion criteria. This stage of the screening process excluded 199 records.

Finally, the full text of the remaining 40 articles was closely read. This resulted in the exclusion of 27 records. In 18 cases, the reason was to be found in the focus of the study (e.g., participating teachers were not involved in doctoral studies during their research). Nine cases were rejected as they were not empirical studies. Figure 1 provides a flowchart of the review process.

4.3 Data evaluation

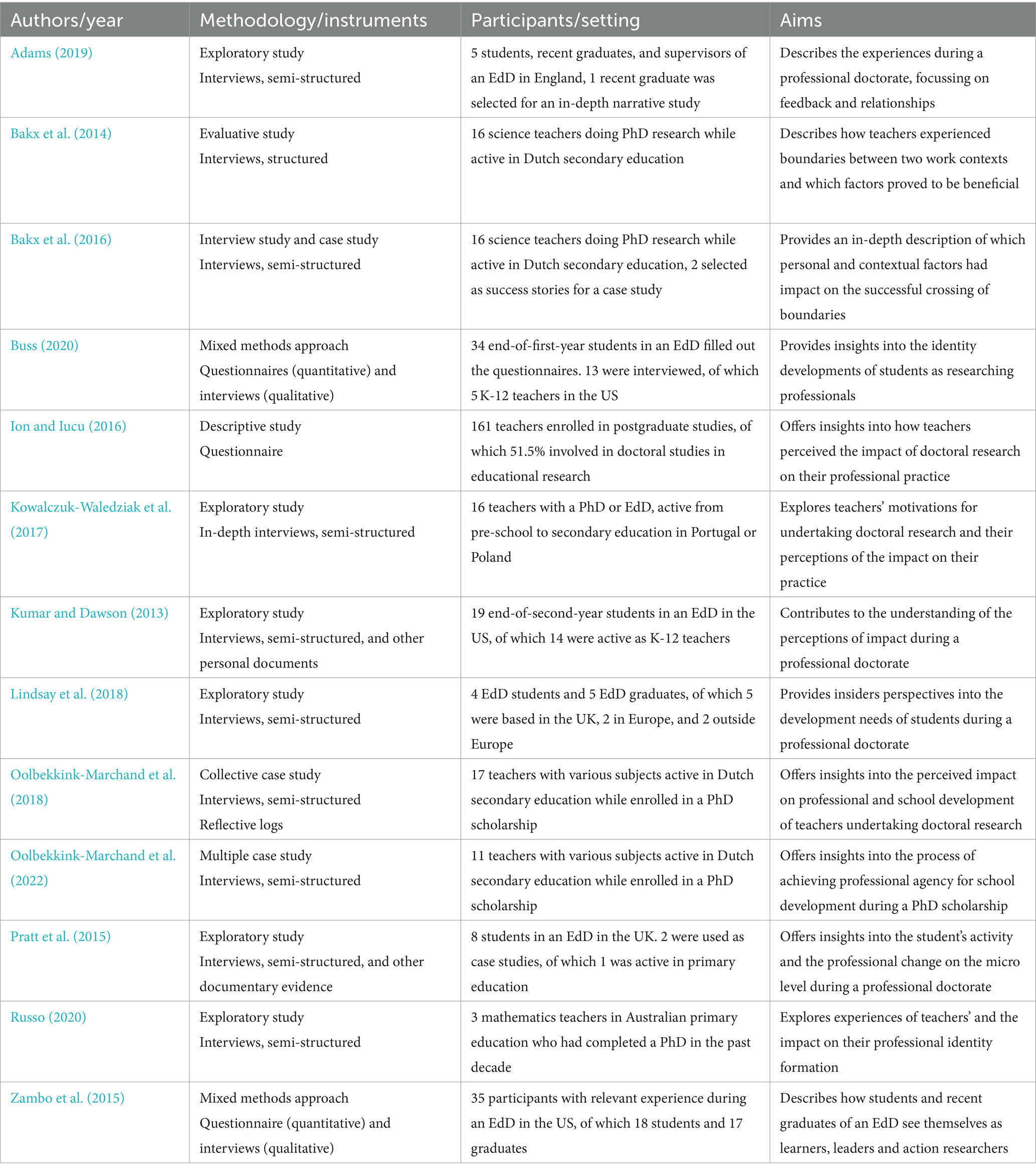

After examining all full texts, a set of articles (n = 13) was identified to start the evaluation stage. Almost all selected articles (n = 11) were based on a qualitative research design. Two studies relied on a mixed methods approach. To investigate the quality, the set of articles was subjected to a critical appraisal using the tool, in its totality, from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2018). Although the tool consists of 10 evaluative questions that assess the strengths and limitations of articles following a qualitative paradigm, it does not rely on a scoring system. While these fixed response options have limitations, the tool’s structured approach can be of value to facilitate the critical appraisal process and distinguish relative research quality (Long et al., 2020). However, as all the articles have an empirical base and have been subjected to the academic process of peer review, the main aim of this critical appraisal is not to exclude certain studies based on a score, but to examine and organize which sections can be prioritized or need to weigh less during the analysis stage. Moreover, none of the selected studies contained significant inconsistencies and, therefore, offered a (small) body of relevant evidence. Table 1 provides an overview of the characteristics of each article.

4.4 Data analysis

The analysis was informed by the guidelines on reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2021). In general, the study can be situated in a qualitative paradigm. Epistemologically, it was guided by a constructivist stance, suited for the chosen analytic approach. This entails the researchers’ positionality shapes the meanings conveyed in the research. According to Braun and Clarke (2021, pp. 333–334), the researchers’ subjectivity—even without the support of a team—is to be considered as a resource, and the analysis “is a situated interpretative reflexive process.” Since no previous frameworks exist, engagement with the data was done inductively and performed by the author, who was, at the time of the study, active as a teacher doing doctoral studies. The concept of boundary crossing informed the analysis, providing a lens for interpreting the interaction between different contexts. This theoretical perspective helped to identify moments of transition and learning across contexts, and to understand participants’ experiences.

In their article on standards for (reflexive) thematic analysis, Braun and Clarke (2021) describe a process of six phases. In this paper, the six phases were interpreted and operationalized as follows. First, after evaluating the quality of the articles, they were read closely for a second time to familiarize with the data. This was done one at a time while highlighting relevant text fragments or making notes. Second, initial codes were developed from the results, discussion, and conclusion sections of the articles. To systematically develop an understanding of the literature, the performed analysis was an iterative process of going back and forth between the set of articles and the codes. Third, themes were generated, informed by codes that seemed to share meaning. In the fourth phase, the relationship between the codes and themes was thoroughly checked. The fifth phase involved a refinement and further development of the initial themes (e.g., renaming them). Finally, the results were linked back to the research question.

5 Results

Three factors that support teachers as educational professionals doing doctoral studies were identified from the literature: (1) a stimulating school culture; (2) engaging with the academic community; (3) and aligning the research design with the practitioners’ needs. The factors are presented in more detail below.

5.1 A stimulating school culture

In relation to the first factor, seven studies were included. These studies focus on the school context. Two subthemes were explored: a mutual understanding with the school leader; and an inspiring interest or involvement of the school team.

5.1.1 A mutual understanding with the school leader

The role of the school leader is explicitly addressed in five studies. Bakx et al. (2014) found that a significant amount of teachers involved in PhD research felt they succeeded in connecting both contexts. When asked which aspects of their school context were felt as conducive for their research, primarily cultural circumstances, for example, an open school climate, and circumstances related to school policy, such as the presence of a research culture and a facilitating role of the school leader, were mentioned. In a follow-up study, Bakx et al. (2016) gained more insight into what personal and contextual factors had an influence on boundary crossing. They found that certain contextual factors limited the teachers’ ability to contribute to school development. Among these contextual factors is the lack of support from the school leader. As a recommendation, they stress the importance of setting up an open and inquisitive school that may stimulate a research-minded school team. From this perspective, Kowalczuk-Waledziak et al. (2017) also recommend encouraging an educational research culture at schools by closely involving the school leaders. In line with this, Oolbekkink-Marchand et al. (2018) point to the necessity of discussing the research in advance with the school management, particularly in light of professional development and school development, while also drawing attention to other contextual factors such as work pressure and the involvement of colleagues. The cases in the study of Oolbekkink-Marchand et al. (2022) stress the need for appreciation of and support from the school leader when impact is desired on school development.

5.1.2 An inspiring interest or involvement of the school team

Five selected studies indicate that the interest of colleagues seems a prerequisite when teachers are involved with doctoral research in a school context. To explore which differences between a professional teaching context and an academic research context can be interpreted as challenging, Bakx et al. (2014) found that most teachers mentioned contrasting cultures on the level of social interactions. Whereas schools rely on an entire team to reach their goals, academic research in universities is a solitary endeavor. These findings that seem to stress the importance of colleagues in the school context are affirmed by the study of Oolbekkink-Marchand et al. (2018) and Oolbekkink-Marchand et al. (2022). However, in these studies, there seems to be a lack of research-mindedness among colleagues, which in its turn, may influence the overarching research culture at the school level. This lack of a research attitude in a school team is experienced as a restriction in light of potential impact on professional development (Bakx et al., 2016) or school development (Ion and Iucu, 2016). When teachers are not given enough resources, such as sufficient time, collaborative support, or access to data, their motivation to conduct research will decline. Regarding school development, Ion and Iucu (2016) recommend setting up horizontal networks among colleagues to disseminate findings from teacher research, as they found that teachers seemed to place significant importance on the perspective of peers for spreading knowledge. Looked at from a more practical standpoint, being part of a supportive school team can facilitate boundary crossing, for example, when there is an issue with conflicting work schedules due to being active in two contexts (Bakx et al., 2016).

5.2 Engaging with the academic community

This factor was apparent in eight studies. In general, all the selected studies describe the importance of support from the academic community. Two subthemes were identified: a constructive relationship with the supervisor(s); and a willingness to learn from peers.

5.2.1 A constructive relationship with the supervisor(s)

The relation with the supervisor(s) is specifically mentioned in four studies. As EdD students mostly have no prior affinity with academia, they have to be guided during their socialization. For example, Bakx et al. (2016) found that teachers require supervisory support during their changing roles from experts in schools to novices in a university context. From this perspective, the findings of Russo (2020) revealed that supervisors who possessed practical wisdom in addition to their academic experience, for instance, because they had worked in a school themselves, were respected more, which served as a motivational factor to enroll. The participants in this study indicated in their reflections that they benefited from this experience and believed that the insights gained from the relationship with their supervisor would improve their professional practice. According to Lindsay et al. (2018), beginning EdD students face specific challenges they are not used to, such as perceiving criticism as personal or dealing with a greater amount of freedom in academia. It seems paramount to conceive the research as a learning process in which the supervisor takes on the role of mentor, both on a personal and professional level. In line with these findings, the case study of Adams (2019, p. 10) described the supervisory relationship as “a continuing dialog that provided academic, practical and emotional guidance.” Interestingly, the study also provided an account of a dynamic relation, claiming that the role of the supervisor needs to be adjusted as the EdD students advance and develop in their socialization during the research process.

5.2.2 A willingness to learn from peers

Six studies reported learning from persons other than the supervisor in the academic community. These peers can be found internally (e.g., inside the university context) or externally (e.g., active in the wider research community). Considering the former category, several selected studies stress the importance of fellow PhD or EdD students that serve as critical friends. For example, these peers seem to be stimulating when specific research competences need to be developed, such as taking a reflective stance (Buss, 2020), engaging with constructive feedback (Adams, 2019), or challenging initial preconceptions (Lindsay et al., 2018). In this respect, findings indicate that forming learning networks (Ion and Iucu, 2016) or establishing research groups (Oolbekkink-Marchand et al., 2018), for instance, to discuss or disseminate findings, seems valuable to students. Nevertheless, taking steps deeper into the research community and attempting to participate can be perceived as challenging. Although this is ascribed mainly to a lack of confidence (Buss, 2020; Kumar and Dawson, 2013), students tend to grow as researchers and become more confident during the first year (Buss, 2020). Therefore, several studies recommend engaging with others and their potential feedback outside the own university context from early on. The findings of Lindsay et al. (2018), for example, revealed that seeking feedback of different audiences by attending conferences, posting on social media, or submitting papers to journals, was perceived as stimulating. Although the participants in this study acknowledged that discussing or presenting findings can be stressful, especially when subject experts are involved, they emphasized the importance of starting this process as soon as possible. In line with this, and to facilitate the feedback of the academic community, Lindsay et al. (2018) also recommend cutting the research into smaller parts that can be submitted as separate articles.

5.3 Aligning the research design with the practitioners’ needs

This factor was apparent in four studies. In these studies, the characteristics of the research design are discussed, pointing to the fact that it seems crucial for doctoral research that it is perceived as relevant from the practitioners’ perspective. For example, in the study of Russo (2020), one of the interviewed teachers felt that classroom practice was inspirational when reflecting on relevant research questions. This response indicates there is a need to not only rely on input from academia (e.g., supervisor and peers) when designing research. In line with this, the EdD students that participated in the study of Lindsay et al. (2018) indicated that it was best to pursue attunement between the research topic and their professional classroom practice. Besides the importance of the input for the research design, relevancy has to be considered for the output as well. For example, in the two case studies of Bakx et al. (2016), the research topics were aligned with the school needs. This was experienced in both cases as beneficial for the reception of the developed educational materials. In this respect, the materials also proved to function as boundary objects, as they were picked up by colleagues. Further emphasizing the need to include the practitioners’ perspective, Oolbekkink-Marchand et al. (2018) showed that all teachers involved in their study experienced space for professional development. However, concerning school development, the impact appeared to be limited. The teachers, therefore, pointed out that a research design that focuses on pedagogy seems more compatible with school development than content-specific research.

6 Discussion and conclusion

This paper aimed to investigate factors that support teachers as educational professionals doing doctoral studies. Although the findings are exploratory, they appear to shed light on evidence that served as successful (components of) practices. Three main factors were generated: (1) a stimulating school culture; (2) engaging with the academic community; (3) and aligning the research design with the practitioners’ needs.

First, and in line with findings of more general research in recent years that point to the need for supportive conditions to allow teacher research (Darling-Hammond, 2017; Labone and Long, 2016; White, 2021), the importance of a stimulating school culture also seems the case in the context of teachers conducting doctoral research. However, the findings of this review show that teachers involved were often hindered by the lack of a research culture at school (Bakx et al., 2014; Bakx et al., 2016; Oolbekkink-Marchand et al., 2018; Oolbekkink-Marchand et al., 2022). In this respect, the role of school leaders counts as a supportive factor, considering their influence on contextual factors at the organizational level. Moreover, horizontal connections with fellow teachers (inside or outside the school) need to be pursued as well (Ion and Iucu, 2016). Sharing insights or ideas and disseminating products can benefit some crucial contextual factors, such as the inspiring interest of colleagues and the overarching research-mindedness of the school.

Second, the findings in this review indicate that sufficient support in the research community is deemed crucial. Although teachers conducting doctoral research often possess adequate experience as practitioners, they struggle with institutionalized practices or traditions in academia (Lindsay et al., 2018). This appears to affirm the description given by Cochran-Smith and Lytle (2009) in their seminal work on a contrasting university culture that is commonly not focused on incorporating practical knowledge. However, it seems possible to overcome this challenge when the socialization in academia is conceived as a considerable learning process on the personal and professional level and is guided by the supervisor as a mentor. In this respect, supervisory support seems to be more stimulating when it is embedded in practical wisdom (Russo, 2020). This possibly reflects the need for supervisors with experience from the practitioners’ side (e.g., in schools) during the initial socialization in academia. This also seems to be compatible with the findings of Adams (2019) that indicate how the role of a supervisor has to be conceived as dynamic during the process, as the needs of the teachers involved have developed since enrollment. Moreover, considering the found lack of confidence during the initial steps in academia in this review (Buss, 2020; Kumar and Dawson, 2013), an engagement with peers in the research community, for example, via conferences or submitting papers and thoughtful guidance based on the professional development needs of the teachers count as supportive factors as well (Lindsay et al., 2018).

Third, an essential condition for success seems to be the applicability of the research to the teachers’ workplace. From this perspective, the findings of this review show that research focussed on pedagogical concerns seems easier to incorporate and reach impact than content-specific matter, not only on professional development but also, to a lesser extent, on school development (Oolbekkink-Marchand et al., 2018). These differences in impact appear to correspond with research conducted by regular full-time teachers during a professional development program (Leuverink and Aarts, 2018). Ideally, the design of the research should be discussed with the school leader and the supervisor so that practical hindrances are overcome (Westbroek et al., 2022) and alignment between academic and school goals is pursued. When there is a disconnect between both contexts, learning during boundary crossing is hindered, as Wang et al. (2022) have shown. Research output, such as lessons, programs, or tools, can function as boundary objects. These developed products seem to facilitate crossing boundaries (Bakx et al., 2016).

Almost all teachers in the studies reported challenges in participating in the two contexts. However, and in line with what Akkerman and Bakker (2011) argued, not all differences have to be regarded as hindering. To overcome the felt differences, several authors of the studies (Bakx et al., 2014; Bakx et al., 2016; Oolbekkink-Marchand et al., 2022) relied on the conceptual framework of boundary crossing. These studies mainly came about in the Dutch research and education context. The value of this paper lies in revealing those actions that proved to be successful during boundary crossing and, as some of these “good practices” can be considered tacit or even self-evident, making them explicit. Nevertheless, in the findings, boundary crossing activities appear to be mostly initiated from research to practice. According to Bakx et al. (2014), it is assumable that this one-sided direction points to an asymmetrical relationship coming from a discrepancy in status between both contexts. However, Russo (2020) found evidence that the classroom experiences of teachers proved to be inspirational for doctoral research. Although based on the response of only one teacher, these findings possibly testify to a two-way relationship between research and practice.

An integrative literature review can encourage the development of new ways of approaching a topic. In this respect, the insights presented in this paper have to be interpreted as a starting point for evidence-informed practice grounded in current literature and as an incentive for future reflections. Despite the diverse background of educational professionals doing doctoral studies, such as teachers, the challenges and opportunities they encounter are largely universal. The factors identified in this literature review are also applicable to other forms of teacher development and to contexts where individuals need to balance multiple professional roles or identities. These findings can provide valuable support to teachers and educational professionals navigating similar situations worldwide.

Nevertheless, more research seems needed, in various and diverse settings (e.g., teachers active in different educational levels, subjects, and national contexts), to gain more insight into the complexity of this emerging field. For example, the personality traits of the teachers involved have to be considered as possible supportive factors as well. Although beyond the scope of this review, it can be stated that personal factors, such as motivational aspects, intentions for professional and school development, level of involvement to the research, or other personality-related qualities, also influence the ability to cross boundaries between school and academia. According to Oolbekkink-Marchand et al. (2022), it is the complex interplay of contextual and personal factors that gives shape to professional agency of teachers involved.

To conclude, this research has two limitations. First, the exploratory nature of the research question and the limited sample of selected empirical studies (n = 13) for the review are possible restrictions. As the study was confined to findings of teachers active in primary and secondary education during the last decade (2012–2022), earlier and more generic literature (e.g., on higher education) was excluded. In this regard, the deliberate focus on teacher research in the search terms was due to the critical importance of discussing or applying research outcomes directly to (their) real-world school contexts. However, this approach may have inadvertently excluded studies labeled under broader categories. Second, although issues of validity were considered throughout the review process (e.g., selection of peer-reviewed studies, the inclusion of a validated tool for critical appraisal, and transparent and rigorous methodology), the data analysis was performed solely by the author. The reasons for this are to be found in the specificity of the topic and the limited research tradition on active teachers doing doctoral studies in Flanders.

Author contributions

JVD: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author declares that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adams, G. (2019). A narrative study of the experience of feedback on a professional doctorate: ‘a kind of flowing conversation’. Stud. Contin. Educ. 41, 191–206. doi: 10.1080/0158037X.2018.1526782

Akkerman, S. F., and Bakker, A. (2011). Boundary crossing and boundary objects. Rev. Educ. Res. 81, 132–169. doi: 10.3102/0034654311404435

Anagnostopoulos, D., Smith, E. R., and Basmadjian, K. G. (2007). Bridging the university-school divide: horizontal expertise and the ‘two-worlds pitfall’. J. Teach. Educ. 58, 138–152. doi: 10.1177/0022487106297841

Arhar, J., Niesz, T., Brossmann, J., Koebley, S., O’Brien, K., Loe, D., et al. (2013). Creating a ‘third space’ in the context of a university-school partnership: supporting teacher action research and the research preparation of doctoral students. Educ. Action Res. 21, 218–236. doi: 10.1080/09650792.2013.789719

Armsby, P., Costley, C., and Cranfield, S. (2018). The design of doctorate curricula for practising professionals. Stud. High. Educ. 43, 2226–2237. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2017.1318365

Aydin, U., Tunc-Pekkan, Z., Taylan, R. D., Birgili, B., and Ozcan, M. (2018). Impacts of a university-school partnership on middle school students’ fractional knowledge: a quasiexperimental study. J. Educ. Res. 111, 151–162. doi: 10.1080/00220671.2016.1220358

Bakker, A., and Akkerman, S. F. (2013). A boundary-crossing approach to support students’ integration of statistical and work-related knowledge. Educ. Stud. Math. 86, 223–237. doi: 10.1007/s10649-013-9517-z

Bakx, A., Bakker, A., and Beijaard, D. (2014). Promotieonderzoek door docenten als brug tussen onderzoek en onderwijspraktijk en ter verbetering van de kwaliteit van het betaonderwijs in het voortgezet onderwijs. Pedagogische Studiën 91, 150–168.

Bakx, A., Bakker, A., Koopman, M., and Beijaard, D. (2016). Boundary crossing by science teacher researchers in a PhD program. Teach. Teach. Educ. 60, 76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.08.003

Beauchamp, C., and Thomas, L. (2011). New teachers’ identity shifts at the boundary of teacher education and initial practice. Int. J. Educ. Res. 50, 6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2011.04.003

Bourner, T., Bowden, R., and Laing, S. (2001). Professional doctorates in England. Stud. High. Educ. 26, 65–83. doi: 10.1080/03075070124819

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 18, 328–352. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

Burgess, H., Sieminski, S., and Arthur, L. (2006). Achieving your doctorate in education. London: Sage in Association with The Open University.

Burton, E. (2020). Factors leading educators to pursue a doctorate degree to meet professional development needs. Int. J. Dr. Stud. 15, 075–087. doi: 10.28945/4476

Buss, R. R. (2020). Exploring the development of students’ identities as educational leaders and educational researchers in a professional practice doctoral program. Stud. High. Educ. 47, 1069–1083. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2020.1836484

CASP (2018). CASP (qualitative) checklist. Available at: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/.

Cochran-Smith, M., and Lytle, S. (2009). Inquiry as stance: Practitioner research for the next generation. New York, NY, United States: Teachers College Press.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher education around the world: what can we learn from international practice? Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 40, 291–309. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2017.1315399

Elsbach, K. D., and van Knippenberg, D. (2020). Creating high-impact literature reviews: an argument for ‘integrative reviews’. J. Manag. Stud. 57, 1277–1289. doi: 10.1111/joms.12581

Engestrom, Y., Engestrom, R., and Kärkkäinen, M. (1995). Polycontextuality and boundary crossing in expert cognition: learning and problem solving in complex work activities. Learn. Instr. 5, 319–336. doi: 10.1016/0959-4752(95)00021-6

Farley-Ripple, E., May, H., Karpyn, A., Tilley, K., and McDonough, K. (2018). Rethinking connections between research and practice in education: a conceptual framework. Educ. Res. 47, 235–245. doi: 10.3102/0013189X18761042

Foster, H., Chesnut, S., Thomas, J., and Robinson, C. (2023). Differentiating the EdD and the PhD in higher education: a survey of characteristics and trends. Impact. Educ. 8, 18–26. doi: 10.5195/ie.2023.288

Ion, G., and Iucu, R. (2016). The impact of postgraduate studies on the teachers’ practice. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 39, 602–615. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2016.1253674

Jablonski, A. M. (2001). Doctoral studies as professional development of educators in the United States. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 24, 215–221. doi: 10.1080/02619760120095606

Jones, M. (2018). Contemporary trends in professional doctorates. Stud. High. Educ. 43, 814–825. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2018.1438095

Juhl, J., and Buch, A. (2019). Transforming academia: the role of education. Educ. Philos. Theory 51, 803–814. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2018.1508996

Kowalczuk-Waledziak, M., Lopes, A., and Menezes, I. (2017). Teachers pursuing a doctoral degree: motivations and perceived impact. Educ. Res. 59, 335–352. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2017.1345287

Kumar, S., and Dawson, K. (2013). Exploring the impact of a professional practice education doctorate in educational environments. Stud. Contin. Educ. 35, 165–178. doi: 10.1080/0158037X.2012.736380

Labaree, D. (2003). The peculiar problems of preparing educational researchers. Educ. Res. 32, 13–22. doi: 10.3102/0013189X032004013

Labone, E., and Long, J. (2016). Features of effective professional learning: a case study of the implementation of a system-based professional learning model. Prof. Dev. Educ. 42, 54–77. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2014.948689

Leuverink, K. R., and Aarts, A. M. L. (2018). A quality assessment of teacher research. Educ. Action Res. 27, 758–777. doi: 10.1080/09650792.2018.1535445

Levin, B. (2013). To know is not enough: research knowledge and its use. Rev. Educ. 1, 2–31. doi: 10.1002/rev3.3001

Levine, A. (2005). Educating school leaders. Princeton, NJ: The Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation.

Lewis, T. (2013). Validating teacher performativity through lifelong school-university collaboration. Educ. Philos. Theory 45, 1028–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-5812.2012.00859.x

Lindsay, H., Kerawalla, L., and Floyd, A. (2018). Supporting researching professionals: EdD students’ perceptions of their development needs. Stud. High. Educ. 43, 2321–2335. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2017.1326025

Long, H. A., French, D. P., and Brooks, J. M. (2020). Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Res. Methods Med. Health Sci. 1, 31–42. doi: 10.1177/2632084320947559

Malin, J., and Brown, C. (2020). The role of knowledge brokers in education: Connecting the dots between research and practice. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Oolbekkink-Marchand, H., Leeferink, H., and Meier, P. C. (2018). Teachers’ professional agency in the context of a PhD scholarship. Pedagogische Studiën 95, 169–194.

Oolbekkink-Marchand, H., van der Want, A., Schaap, H., Louws, M., and Meijer, P. (2022). Achieving professional agency for school development in the context of having a PhD scholarship: an intricate interplay. Teach. Teach. Educ. 113:103684. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103684

Pratt, N., Tedder, M., Boyask, R., and Kelly, P. (2015). Pedagogic relations and professional change: a sociocultural analysis of students' learning in a professional doctorate. Stud. High. Educ. 40, 43–59. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2013.818640

Russo, J. A. (2020). The experiences and identity structures of teacher-researcher hybrid professionals in a primary school mathematics context. EURASIA J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 16:1861. doi: 10.29333/ejmste/8250

Rycroft-Smith, L. (2022). Knowledge brokering to bridge the research-practice gap in education: where are we now? Rev. Educ. 10:e3341. doi: 10.1002/rev3.3341

Savva, M., and Nygaard, L. P. (2021). Becoming a scholar: Cross-cultural reflections on identity and agency in an education doctorate. London, United Kingdom: UCL Press.

Scott, D., Brown, A., Lunt, I., and Thorne, L. (2004). Professional doctorates: Integrating professional and academic knowledge. Maidenhead, Berkshire, United Kingdom: Open University Press.

Shulman, L. S., Golde, C. M., Bueschel, A. C., and Garabedian, K. J. (2006). Reclaiming education’s doctorates: a critique and a proposal. Educ. Res. 35, 25–32. doi: 10.3102/0013189X035003025

Sjölund, S., Lindvall, J., Larsson, M., and Ryve, A. (2022). Mapping roles in research-practice partnerships: a systematic literature review. Educ. Rev. 75, 1490–1518. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2021.2023103

Smedley, L. (2001). Impediments to partnership: a literature review of school-university links. Teach. Teach. 7, 189–209. doi: 10.1080/13540600120054973

Smith, S. (2022). Methodology and the professional doctorate: the muddy waters of knowledge creation, transfer and workplace capital. Prof. Dev. Educ. 48, 353–360. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2020.1711800

Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: an overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 104, 333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

Star, S. L., and Griesemer, J. R. (1989). Institutional ecology, translations and boundary objects: amateurs and professionals in Berkeley's Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39. Soc. Stud. Sci. 19, 387–420. doi: 10.1177/030631289019003001

Suchman, L. (1994). Working relations of technology production and use. Comput. Supported Coop. Work 2, 21–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00749282

Torraco, R. J. (2016a). Writing integrative literature reviews: using the past and present to explore the future. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 15, 404–428. doi: 10.1177/1534484316671606

Torraco, R. J. (2016b). Writing integrative reviews of the literature: methods and purposes. Int. J. Adult Vocat. Educ. Technol. 7, 62–70. doi: 10.4018/IJAVET.2016070106

Vulliamy, G., and Webb, R. (1992). The influence of teacher research: process or product? Educ. Rev. 44, 41–58. doi: 10.1080/0013191920440104

Wadham, B., and Parkin, N. (2017). Strange new world: being a professional and the professional doctorate in the twenty-first century. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 54, 615–624. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2017.1371627

Wang, Z., Yuan, R., and Liao, W. (2022). Learning to teach through recursive boundary crossing in the teaching practicum. Teach. Teach. 28, 1000–1020. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2022.2137139

Westbroek, H., Janssen, F., Mathijsen, I., and Doyle, W. (2022). Teachers as researchers and the issue of practicality. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 45, 60–76. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2020.1803268

White, S. (2021). Generating enabling conditions to strengthen a research-rich teaching profession: lessons from an Australian study. Teach. Educ. 32, 47–62. doi: 10.1080/10476210.2020.1840545

White, E., Timmermans, M., and Dickerson, C. (2022). Learning from professional challenges identified by school and institute-based teacher educators within the context of school–university partnership. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 45, 282–298. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2020.1803272

Whittemore, R., and Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 52, 546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

Wildy, H., Peden, S., and Chan, K. (2015). The rise of professional doctorates: case studies of the doctorate in education in China, Iceland and Australia. Stud. High. Educ. 40, 761–774. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2013.842968

Zambo, D., Buss, R. R., and Zambo, R. (2015). Uncovering the identities of students and graduates in a CPED-influenced EdD program. Stud. High. Educ. 40, 233–252. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2013.823932

Keywords: professional development, educational doctorate, boundary crossing, teacher research, knowledge broker, evidence-informed practice, doctoral program

Citation: Van Doorsselaere J (2024) Factors that support teachers as educational professionals doing doctoral studies: an integrative literature review. Front. Educ. 9:1466631. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1466631

Edited by:

Cheng Yong Tan, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaReviewed by:

Joel Malin, Miami University, United StatesAnita Caduff, University of California, San Diego, United States

Copyright © 2024 Van Doorsselaere. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joris Van Doorsselaere, am9yaXMudmFuZG9vcnNzZWxhZXJlQHVnZW50LmJl

Joris Van Doorsselaere

Joris Van Doorsselaere