95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 24 October 2024

Sec. Language, Culture and Diversity

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1465765

This study examined the influence of mobile-assisted critical writing instructions on EFL learners' writing skill in language institutes. Ninety EFL learners who were studying English at three branches of a language institute in Iran took part in this research. Two equal groups as control and experimental were formed. As the pretest, a writing task was assigned to the groups which required them to write an argumentative report. The reports were the participants' personal analyses of the contents they had viewed on TV about an important political issue. After the pretest, the control group received instructions for critical writing in class without using Instagram. The treatment lasted for 12 weeks. During the treatment, the control group were asked to watch some TV channels devoted to news. The experimental group received instructions for critical writing in class and via Instagram. The treatment lasted for 12 weeks. The experimental group, who were all Instagram users, were asked to view some Instagram accounts belonging to famous news agencies. Additionally, an Instagram account was created by the teacher and they were asked to follow it for receiving instructions there. When the treatments ended, the posttest was administered. The control group were required to watch the TV channels and the experimental group were required to view the Instagram accounts to write an argumentative report about an important political issue. The reports were the participants' personal analyses of the contents they had viewed. Despite having nearly the same mean scores on the pretest, the two groups' mean scores on the posttest were different and the experimental group scored higher than the control group. Finally, 15 members of the experimental group were interviewed. The focus of the interview was on the participants' suggestions and criticisms of the study. Overall, the experimental group had positive perceptions of the treatment. This study may have implications for teacher trainers, supervisors, teachers, and textbook writers.

Teaching and learning writing skill needs special attention due to its multifaceted nature. In spite of its obvious simplicity, learning writing skill requires concentrated practicable commitment (Zainuddin et al., 2019). Writing is a cognitive process elaborately connected with thinking skills. Being equipped with critical thinking skills enables students to guide a continuum of ideas in writing. Writing is the product of associating processes of critical thinking and writing itself navigated by certain purposes accompanied by the writer's intention (Kamaşak et al., 2021). Yule (2022) argued that language is a means for expressive communication, enunciating attitudes and feelings, and knowledge by argumentation. Argumentative writing is the focal point of language as a tool of argumentation which ascertains whether a statement is valid or not. Argumentative writing comprises deductive and inductive approaches which utilize varied strategies to persuade the audiences to accept the attitude presented in the text (Bean and Melzer, 2021). There is a noticeable connection between critical thinking and argumentation. Organization of claims pertains to argumentation in critical thinking which is the basis for making logical conclusions (Graham et al., 2020). Elder and Paul (2020) asserted that analysis, evaluation, and presenting convincing arguments constitute critical thinking which is a prerequisite for argumentative writing. Since students should persuasively present their ideas and also encounter opposing attitudes. Critical thinking skills could be developed by focused discussions specifically those facilitated by teachers. In the discussions, students can articulate their attitudes, inquire assumptions, and demand elucidation on complicated issues.

Critical writing concentrates on the author's learning experiences to identify their importance and meanings primarily for the author. Critical writing is not neutral in knowledge reproduction. Rather, it is a means that could be utilized to foster varied desirous qualities of learning and knowledge production. According to Zhu et al. (2020), argumentative writing is a social and verbal action which offers a justification to support or oppose an idea by utilizing convincing techniques to direct the audiences' minds toward rejecting or accepting a certain proposal. Some previous studies have shown that becoming involved in critical writing associates the students with academic language use. Consequently, the learning process becomes more active and students' academic identity develops as well (Gee, 2002; Gibson et al., 2016; Granville and Dison, 2005). Several studies concentrated on how critical writing might assist metacognitive development of students (Lew and Schmidt, 2011; Menz and Xin, 2016). Carstens (2012) showed how students' critical writing helped them to become independent learners. Therefore, to achieve academic success, it is vital that students understand learning processes and their own learning strategies. This conception of their meta-learning may also assist them to control and evaluate their learning (Colthorpe et al., 2018). It could be concluded that critical writing assignments could facilitate students' metacognitive development and academic skills (Badenhorst et al., 2020; Dean O'Loughlin and Miller Griffith, 2020; Ono and Ichii, 2019; Redwine et al., 2017; Sweet et al., 2019; Szenes and Tilakaratna, 2020).

To deal with the complexity of problems caused by the fast development of technology, learning critical thinking is increasingly required (Ulger, 2018). Thus, educational systems are expected to teach critical thinking to students (Ali and Awan, 2021; Alotaibi, 2013; Ulger, 2018). Based on the results of the previous studies, there is a positive correlation between critical thinking dispositions and critical thinking skills (Ali and Awan, 2021; Kirmizi et al., 2015). Therefore, critical thinking disposition is of equal significance as critical thinking skill (Facione, 2015). Davies (2013) argued that even though it is widely accepted that teaching critical thinking to students is an essential goal of education, critical thinking skills have not been taught to the desired extent. To change this situation, a major shift in educational paradigms, public investment in teacher education, and policies on school curricula is required (Alandejani, 2021; Al-Zou'bi, 2021; Patonah et al., 2021). It is necessary that education policy makers consider disciplines at how to develop students' critical thinking rather than concentrating on individual subjects continuously (Behar-Horenstein and Niu, 2011). According to Nesi and Gardner (2006), teaching critical thinking and argumentative skills is mainly pursued in academic courses. Nonetheless, in spite of the significance of argumentative writing in academic contexts, many studies in both L1/L2 writing contexts have revealed the difficulties that students encounter to learn argumentative writing skills (Abdollahzadeh et al., 2017; Altinmakas and Bayyurt, 2019; Divsar and Amirsoleimani, 2021; Qin and Karabacak, 2010; Saprina et al., 2020; Sundari and Febriyanti, 2021).

With regard to the developing technology in 21th century, life encourages us to be a sophisticated person in the field of academia. This requires integrating technology into the process of teaching and learning. Mobile-Assisted Language Learning (MALL) is the most proven technology which is currently used to make education easy, efficient, and creative. Unlike classroom education, in MALL learners are not obliged to attend classes or sit in front of a computer to learn the educational materials. They only need to have a mobile device to learn wherever they want without any restrictions in terms of time and place (Miangah and Nezarat, 2012). Today, most people are users of social media, thus, social media could be utilized for language learning (Al-Jarrah et al., 2019). Recently, many scholars have paid noticeable attention to MALL. They have worked on the possibilities and barriers of MALL such as the effect of mobile learning on academia, technologies of MALL, and educational environments. It has been proven that smartphones can be utilized for learning English due to the accessibility of many applications like WhatsApp, Viber, Line, Telegram, and Instagram which could be utilized in this field (Çakmak, 2019; Rajendran and Yunus, 2021). Social media are not only used as a medium of instruction, but they also encourage and enhance learning by providing teachers and learners with new and exciting ways for teaching and learning (Mansoor, 2016). By the use of social media, teachers constantly have access to their students. Students can also engage in collaborative dialogs with their teachers and peers, exchange ideas, and find answers to their questions (Lunden, 2014; Mansoor and Abd-Rahim, 2017). According to recent studies in the field of MALL, Instagram is an effective tool for teaching and learning. It provides learners with opportunities to practice language, maximizes input, and enhances accuracy (Erarsalan, 2019; Fathi, 2018; Wahyudin and Mulya Sari, 2018).

Recently, there have been developments in the field of critical thinking which have resulted in a rise in interest to explore EFL learners' critical writing. It is becoming more and more important to focus on EFL learners' critical thinking abilities (Warsah et al., 2021). During recent years, teacher-centered perspective has changed to a student-centered one. Nowadays, learners are responsible for their learning. They are supposed to use language learning strategies effectively and be aware of their own individual needs (Teng, 2020). The findings of several studies have shown that utilizing Instagram helped ESL/EFL learners to improve their writing skill (Erarsalan, 2019; Handayani, 2016; Manaroinsong, 2018; Pujiati et al., 2019; Wulandari, 2019). There is a need for empirical evidence to prove the effectiveness of mobile-assisted critical writing instructions on EFL learners' writing skill in language institutes. In addition, it is important to investigate EFL learners' perceptions of employing a mobile-assisted critical writing approach in language institutes. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, the effect of EFL learners' gender on their performance on writing tests after receiving mobile-assisted critical writing instructions has never been investigated. Therefore, with the aim of filling the existing gap, the following questions navigated the study:

1. Does any significant difference exist between the writing proficiency of EFL learners who receive mobile-assisted critical writing instructions and EFL learners who are instructed through a traditional approach?

2. What are EFL learners' perspectives on receiving mobile-assisted critical writing instruction?

3. Do male and female EFL learners perform differently on writing tests after receiving mobile-assisted critical writing instruction?

Vygotsky (1978) argued that human learning is connected with social and cultural environment. He considered people as conscious individuals continuously interacting with people around them. The theory of scaffolding was developed within the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) which was based on Vygotsky's sociocultural theory. The fundamental idea of this theory is that a more knowledgeable individual assists knowledge acquisition of a less knowledgeable individual. The metaphor of scaffolding refers to the contemporary assistance given to learners which disappears when learners do not need it (Boblett, 2012; Schwieter, 2010). The explicit instruction within an academic context becomes possible by scaffolding. Scaffolding is a flexible, adaptable, and changeable manner of instruction (Riazi and Rezaii, 2011). The type of assistance given to learners depends on the features of a particular pedagogical context and scaffolding is not utilized the same way in different contexts (Van de Pol et al., 2010). Vygotsky (1978) stated that scaffolding writing empowers the less proficient individuals to change misunderstandings, fill in the lacunas in comprehension, make connections between new information and previously acquired information, and develop new problem-solving skills. Lidz (1991) declared that scaffolding learning was teachers' adjustment of the instructions complexity to facilitate learners' task expertise and motivating them to move forward when they feel ready. In the process of scaffolding, a teacher recognizes what is easy or demanding for a learner and then guides the learner through a continuous and longitudinal plan of action (Van Lier, 1996). Bruner (1985) asserted that scaffolding by teacher does not mean to make the assignment easier; rather, it means to make the maximum of the assignment possible with assistance. Vygotsky (1987) believed that learners' background knowledge should not be central to teachers; rather, teachers' concentration should be centered on learners' progress in tomorrow.

According to Sternberg and Halpern (2020), critical thinking is a reflective and methodical process for making decisions which has five key aspects: employing sound reasons, awareness of seeking and engaging valid reasons with reflective thinking, thinking guided toward a particular goal, making decisions based on assessing behaviors or statements, and dispositions and cognitive abilities to use competence. However, still there is no consensus considering the best method for teaching critical thinking instructions. Critical thinking is mainly taught through a combined course-learning curriculum. Integrating critical thinking into writing instructions is a process connected with the ability to think creatively (Cui and Teo, 2023; Onoda, 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). Bezanilla et al. (2019) argued that critical thinking could be improved through writing since writing facilitates analysis and interpretation of gathered data. This process is rooted in metacognitive strategies. According to Lavoie et al. (2020) critical thinking is a fundamental component of writing which enables students to guide a spectrum of ideas. Writing is the product of associating processes of writing and critical thinking navigated by certain purposes aligned with the author's intention. Kasim et al. (2022) substantiated this concept by declaring that writing represents organized ideas on a subject disentangling the author's critical thinking. McTighe and Schollenberger (1985) argued that critical thinking is necessary for argumentative writing due to three reasons: (a) increasing demand for knowledge and technology, (b) students' inadequate thinking and metacognitive skills, and (c) the prevalence of the teacher-centered approach in pedagogical contexts. Among various types of writing, argumentative writing is considered as the most challenging one (Grabe and Kaplan, 1996; Siregar et al., 2021). In ESL/EFL courses, argumentative writing has long been on the periphery. Nowadays, it is widely accepted that ESL/EFL learners' argumentative writing should be assessed as a way of evaluating their writing proficiency in English. Argumentative writing is an integral part of language proficiency development, because it empowers ESL/EFL learners to represent their ideas and defend them in academic and professional contexts (Yule, 2022). According to Yamin and Purwati (2020) critical thinking skill was vital in writing instructions since it enabled the learners to build a sense of criticism toward any subjects. Ferrett (1997) asserted that a good critical thinker is a good writer because the outcome of critical thinking is a good piece of writing. The process of critical thinking begins with conception, analysis, and evaluation of ideas before drawing conclusion in written form.

All of the features of persuasive writing exist in critical writing from two perspectives: (a) an author represents an evaluation and provides an alternative interpretation of the text, and (b) critical writing contains critique, debate, disagreement, and evaluation. Based on critical writing principles, authors are required to propagate academic voices that contain a healthy specticism, confidence, critical conclusion, opinions, and an adequate and fair evaluation of a given subject (Ataç, 2015). Nevertheless, cynicism, cockiness, arrogance, dismissiveness, opinionatedness, randomness, prejudice, and unsupported assertions are not tolerated by critical writing (Wellington et al., 2005). Being critical does not mean to criticize in a negative manner. Critical analysis of a text means to question the information and ideas that it presents in order to evaluate its overall worth. Critical writing does not simply mean to transform a writer's knowledge in a way that includes general or specific point of views; rather, it refers to going beyond generalizations toward transferring the writer's critical thinking. Critical writing demands the authors to analyze, interpret, and evaluate information to presents their ideas and evidence and draw mindful conclusions in their writing (Carroll and Wilson, 2014). Writers face many difficulties in constructing the form and content of a piece of writing. In argumentative writing, a piece of writing should be in line with academic standards and its content should be supported by logical arguments and factual examples (Beniche et al., 2021).

Burston (2014) defined MALL as a method which advocates the use of accessible and portable tools for language learning. Burston (2013) argued that MALL concentrates on utilizing digital dictionaries, cellphones, and music players. Because of their widespread ownership and use, smartphones have become the main choice among MALL application developers (Burston, 2014). Recent evidence has shown that using smartphone applications can improve autonomous learning (Howlett and Waemusa, 2019). It has been claimed that in comparison with other teachers, language teachers have shown more enthusiasm toward employing MALL (Youngkyun et al., 2017). MALL has been widely studied by many researchers. Duman et al. (2015) reviewed the studies conducted from 2000 up to 2012 and found that this area of research constantly grew with the growth of smartphones as the most often used media and vocabulary as the most researched topic. As a result of globalization, English has widely spread all around the world for sharing and exchanging information, news, and knowledge. In this regard, social media tools are one of the most considerable advancements, because individuals can interact with each other. Social media tools can be integrated with academia, thus, it can be concluded that using social media with language teaching and learning empowers students to make progression in learning. As a result, students feel more interested and enthusiast to socialize and communicate with others and enjoy their classes (Al-Ali, 2014).

Even though plenty of studies have explored the educational functions of Facebook and Twitter, this point should be considered that young generations are consistently migrating to Instagram from other popular Social Networking Systems (SNSs) (Lomicka and Lord, 2016). Thus, it is important to investigate the influence of using Instagram on ESL/EFL learners' English learning. In 2010, Instagram was launched as a photo sharing platform and as a result of several updates which have been made so far, new features such as video and story sharing have been added to it. These new updates over the time contributed to the increasing popularity of Instagram (Ellison, 2017). Handayani (2016) argued that by utilizing Instagram learners can share their ideas and information on different subjects and participate in group activities by viewing others' comments on photos or videos. Instagram can be utilized for conducting activities like digital storytelling and practicing grammar through photos and videos. Instagram can also be used for teaching vocabulary and the four language skills (Handayani, 2016). Soviyah and Etikaningsih (2018) used Instagram to teach writing skill and found that using Instagram had a positive influence on the learners' writing skill. In another study, Purnama (2018) reported that using Instagram enhanced the students' motivation for learning and their participation in classroom activities. Likewise, Mansoor and Abd-Rahim (2017) reported that using Instagram encouraged the learners to do group work and have interaction and collaboration with their classmates. Al-Ali (2014) investigated the integration of Instagram in EFL classroom. The study was concentrated on speaking and writing skills. The findings showed that Instagram was effective in providing the learners with individualized learning experiences. Furthermore, using Instagram formed a strong sense of community among the learners. Accordingly, there is a need for conduction of new studies to determine the capacities that Instagram has to be used for language education (Lomicka and Lord, 2016). By utilizing Instagram, students experience learning in an authentic environment which is motivating for them. Since what they express and declare is based on their personal life experiences (Listiani, 2016). Moreover, users have the opportunity to read and write through photo description, comments, and direct messages as well as enhancing their vocabulary and grammatical knowledge (Alnujaidi, 2016). According to Al-Ali (2014), familiarizing learners with Instagram is beneficial to them. As it can decrease the stress they experience by utilizing unfamiliar tools for educational activities. Likewise, Wiktor (2012) argued that Instagram can positively influence learners' special intelligence and linguistic intelligence. Erarsalan (2019) conducted a study to explore university students' opinions about Instagram as an educational platform with respect to language learning purposes. Based on the findings of the study, Instagram was the most frequently utilized social media platform among the participants and they had positive attitudes toward employing it for pedagogical purposes and language learning. Furthermore, analyzing the learners' achievement scores revealed that Instagram positively influenced the learners' language learning. In another study, Gonlul (2019) aimed to explore how English language learners used Instagram for language learning purposes and know their opinions and experiences of utilizing it as a Mobile-Assisted Language Learning (MALL) tool. Based on the results of the study, most of the participants reported that they were actively using Instagram for English language learning purposes and followed certain Instagram accounts devoted to English language learning. The author reported that there was a positive correlation between high language learning motivation and the increased use of technology (as in Cluster 1), and between the use of technology and the increased language learning motivation (as in Cluster 2). The second purpose of the study was to investigate the learners' opinions about using Instagram and the experiences they had in terms of utilizing it for informal language learning. The learners' overall opinions about utilizing Instagram were positive and they virtually regarded Instagram as a motivating and interesting mobile learning tool. They also considered Instagram as an easy and convenient way for improving their overall communication skills.

Awada et al. (2019) investigated the impact of student team achievement division through WebQuest on EFL learners' argumentative writing skills and their educators' attitudes toward it. The study was conducted based on a mixed-methods pretest-posttest control-experimental group design. Six intact rhetoric classes were randomly assigned to two conditions as control and experimental. The experimental group received argumentative writing instructions integrating Student Team Achievement Division Inquiry-Based Technological Model (STADIBTM), while their counterparts in the control group were instructed utilizing the same argumentative instructions without STADIBTM. The authors claimed that the treatment delivered to the experimental group was more effective than the treatment delivered to the control group. The teachers' had positive perceptions of utilizing STADIBTM for teaching argumentative writing. However, the authors did not investigate the experimental group's perceptions of the treatment they had received. Conducting interviews and gathering qualitative data could assist the researchers to know the participants' needs and desires. Consequently, the continuation of the instructions for upcoming semesters would be more successful. Additionally, the scholars working in the field of teaching writing skill would benefit from the participants' assertions and plan good schedules for teaching writing.

Ghanbari and Salari (2022) conducted a study to investigate Iranian EFL undergraduate students' perceptions of argumentative essay and the difficulties they faced in writing argumentative essays identified by their teachers. They also analyzed the structure of argumentative writing by Iranian EFL undergraduate students. The authors claimed that the way the students perceived the argumentative essay showed that they had scant knowledge about the concept of argumentative writing. The problem that was most frequently mentioned by the participating educators concerned lack of structure in the learners' argumentative essays. In fact, the educators stated that the learners could not classify their perspectives into a reasonable structure. The essays were not well-organized to present the writers' ideas coherently. Additionally, the learners could not state their claims in a sensible argumentative structure. The teachers declared that the next most frequent problem in the essays was lack of evidence. The learners had used their own personal or popular attitudes instead of using sources to support their claims. The students also had failed to select the right information to be included in their essays and had used lots of irrelevant information which were misleading to their line of argumentation and did not help the argument. The next problem most frequently mentioned by the instructors was the students' inability to critically assess the information. The students were not able to provide relevant evidence, analyze the information critically, and represent inclusive and coherent arguments. The educators also stated that the students' English proficiency level was low which prevented them from writing argumentative essays in English. They declared that English programs in Iranian EFL context concentrated on enhancing students' proficiency in basic language skills. The next difficulty that the participants had encountered pertained to their lack of experience in terms of L1 and L2 pre-university writing. They were not familiar with argumentative writing which caused them to write explanatory essays instead of argumentative essays. The teachers believed that the learners' first writing practices in English had occurred at university and English language teaching in Iran had followed a grammar-translation method focusing on reading comprehension. The lack of experience and the traditional method of teaching English were two effective factors which resulted in the learners' poor performances in writing argumentative essays. The last problem mentioned by the educators was ignoring the priority of argumentative writing both by teachers and the national curriculum. Explicit instruction had not been considered for argumentative writing and it had been regarded as a genre like other essay types. Moreover, some teachers asserted that many Iranian EFL teachers had scant knowledge about argumentation. However, the authors have not provided any explanations about the design of the study and the procedure utilized for its conduction. The authors have not provided any information about the participants' background academic knowledge in terms of English proficiency for EFL learners and professional competence and expertise for the teachers. There is no information available about the writing instructions delivered to the students or the educational materials which were taught during the course.

Ninety EFL learners who were studying English at three branches of a language institute located in Iran with a limited age range (21–23) including 49 females and 41 males took part in this research. They were selected through convenience sampling and shared the same L1 which was Persian. Based on their scores on DIALANG, two equal groups (in terms of number and English proficiency) as control and experimental were formed.

The learners' proficiency in English was checked by administering DIALANG. DIALANG assesses reading, listening, writing, grammar, and vocabulary. DIALANG tests its users' proficiency level in 14 European languages. It is only utilized as a diagnosis test and its usage for purposes other than diagnosis is rejected by its inventors. DIALANG provides its users with feedback and reviews their answers to the test items. Users' proficiency level is determined based on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). Based on CEFR, levels of proficiency are categorized as A1 (Breakthrough), A2 (Wastage), B1 (Threshold), B2 (Vantage), C1 (Effective Operational Proficiency), and C2 (Mastery). In order to check the participants' homogeneity in terms of English proficiency and assign them to the control experimental groups, they were asked to consult https://dialangweb.lancaster.ac.uk and take the test. They were required to send the results to the teacher via e-mail. Then the learners were assigned to two equal groups as experimental and control based on their scores on DIALANG.

The teacher assigned a writing task to the control and experimental groups (Supplementary Appendix A). The task required the learners to write an argumentative report (using Microsoft Word Document) containing 2,000–2,500 words. The reports were the participants' personal analyses of the contents they had viewed on TV about an important political issue. The two groups were asked to watch some TV channels devoted to news. The channels introduced to them were Euronews, BBC, VOA, CNN, Reuters, Foxnews, and France 24-En. The participants sent the tests' results to their teacher via e-mail. For coding the pretest scores, the teacher rated the responses by using the IELTS marking scheme for writing.

The control group received instructions for critical writing in class without using Instagram. They were studying their coursebooks during the semester which were Evolve 6 and Oxford Word Skills (Upper-Intermediate-Advanced Vocabulary). Moreover, Goatly and Hiradhar (2016), Critical Reading and Writing in the Digital Age: An Introductory Coursebook (2nd edition), was taught in addition to the coursebooks. The treatment lasted for 12 weeks each week for two sessions and each session for 2 h. The teacher prepared summaries of each unit of the book and presented them during 30 min in each session. The 30-min-instruction was delivered at the beginning of each session and the rest of time (90 min) was devoted to teaching the coursebooks. The control group were asked to watch some TV channels devoted to news. The channels introduced to them were Euronews, BBC, VOA, CNN, Reuters, Foxnews, and France 24-En. The control group were asked to watch the channels daily on TV to view videos about political subjects. An important political issue that the participants had viewed some contents about prior to the upcoming session would become the subject of classroom discussion. The teacher and all the students would participate in the discussion to identify the strategies used for making and presenting the contents in the channels to have the most influential impact on the audiences' minds. Moreover, the participants were required to deliver an argumentative report before the first weekly session every week. The reports were the participants' personal analyses of the contents they had viewed about the predetermined political issue. The participants were required to write the reports (using Microsoft Word Document) and the reports had to contain 1000 to 1500 words. The reports were delivered to the teacher via email before the first weekly session. The researchers would divide the reports among themselves and comment on them. The reports would be sent back to the participants after the second weekly session. By receiving comments on their reports, the participants would have the opportunity to know their weaknesses and improve their next report.

The experimental group received instructions for critical writing in class and via Instagram. They were studying their coursebooks during the semester which were Evolve 6 and Oxford Word Skills (Upper-Intermediate-Advanced Vocabulary). Moreover, Goatly and Hiradhar (2016), Critical Reading and Writing in the Digital Age: An Introductory Coursebook (2nd edition), was taught in addition to the coursebooks. The treatment lasted for 12 weeks each week for two sessions and each session for 2 h. The teacher prepared summaries of each unit of the book and presented them during 30 min in each session. The 30-min instruction was delivered at the beginning of each session and the rest of time (90 min) was devoted to teaching the coursebooks. The experimental group, who were all Instagram users, were asked to view @euronews, @bbc, @voa, @cnn, @reuters, @foxnews, and @france24_en on Instagram daily with the aim of watching videos about political subjects presented in the accounts and analyzing the analyses presented there. These Instagram accounts are very active and upload posts, stories, and reels every day. They belong to the most famous press agencies in the world. The contents of the accounts are devoted to political news and issues. These accounts have many followers who comment on the posts and also have interaction in the comments section. Critical instructions mostly focus on political and social issues, thus, these accounts were suitable for training the experimental group. An important political issue that the participants had viewed some contents about prior to the upcoming session would become the subject of classroom discussion. The teacher and all the participants would participate in the discussion to identify the strategies used for making and presenting the contents in the Instagram accounts to have the most influential impact on the audiences' minds. Moreover, the participants were required to deliver an argumentative report before the first weekly session every week. The reports were the participants' personal analyses of the contents they had viewed about the predetermined political issue. The participants were required to write reports (using Microsoft Word Document) and the reports had to contain 1,000–1,500 words. The reports were delivered to the teacher via email before the first weekly session. The researchers would divide the reports among themselves and comment on them. The reports would be send back to the participants after the second weekly session. By receiving comments on the reports, the participants would have the opportunity to know their weaknesses and improve their next report. Additionally, an Instagram account was created by the teacher and the posts, reels, and stories adopted from some Instagram accounts available in Instagram Explore were re-shared there. The experimental group were required to follow the account and participate in the process and interact with their peers and the researchers. The content was mostly adopted from the accounts active in social and political news and issues, but they were not as famous as the ones mentioned earlier. Hence, it was not easy for the participants to find the accounts and view what they presented. The teacher eased the process of finding new contents by searching and obtaining the materials and presenting them in the account of the class. The teacher would upload questions in stories and the learners were required to write their answers and reply the stories. The teacher would read all the messages received and answer them. The responses were also uploaded as stories by hiding the users' names until all the participants could see their classmates' responses and the teacher's explanations. The teacher also made some videos using Inshot application. In the videos, the teacher provided some explanations on the videos which were presented in @euronews, @bbc, @voa, @cnn, @reuters, @foxnews, and @france24_en and the account of the class. It was a way of online learning where the students could see their teacher explaining critical writing instructions in a context other than classroom setting. The teacher also held meetings once a week in Instagram Live and the learners could interact with their teacher and peers by talking in the Live via their cameras or commenting on the Live while others were speaking. The teacher adopted a turn taking strategy and each session was devoted to letting four students attend the live by their cameras on and interacting with their teacher. The comments under each Instagram post uploaded in the classroom account were also an opportunity for writing skill. Everybody was supposed to write his/her comments regarding the uploaded post and then the interactions among the learners and the teacher would begin.

The teacher assigned a writing task to the control and experimental groups (Supplementary Appendix B). The task required the learners to write an argumentative report (using Microsoft Word Document) containing 2,000–2,500 words. The reports were the participants' personal analyses of the contents they had viewed on TV for the control group, and on Instagram for the experimental group about an important political issue. The control group were asked to watch some TV channels devoted to news. The channels introduced to them were Euronews, BBC, VOA, CNN, Reuters, Foxnews, and France 24-En. The experimental group were required to view @euronews, @bbc, @voa, @cnn, @reuters, @foxnews, and @france24_en on Instagram to check the posts and stories concerning the predetermined political issue. They were supposed to study the political analyses presented in the Instagram accounts and write a piece of argumentative writing about the analyses they had studied on the issue. The participants sent the tests' results to their teacher via e-mail. For coding the posttest scores, the teacher rated the responses by using the IELTS marking scheme for writing.

As the final phase of this study, 15 members of the experimental group were interviewed (Supplementary Appendix C). The 15 learners were chosen based on their marks on the posttest. Five of them were the top five high scorers, the other five ones were middle-scorers, and the last five ones had scored the lowest in the group. To provide the participants with the opportunity to state their attitudes and express their emotions precisely, the researchers conducted the interviews in the participants' native language which was Persian. So, their English proficiency would not be an obstacle preventing them from declaring their attitudes precisely. Each interview lasted 30 min which was recorded and transcribed verbatim. The teacher translated the interviews into English and the other researchers checked the transcripts to make sure that they were translated appropriately. The focus of the interview was on the participants' suggestions and criticisms of the study.

The design of this study was Nonrandomized Control Group, Pretest-Posttest design (Ary et al., 2019). Ninety EFL learners who were studying English at three branches of a language institute located in Iran with a limited age range (21–23) including 49 females and 41 males took part in this research. They were selected through convenience sampling and shared the same L1 which was Persian. Based on their scores on DIALANG, two equal groups were formed as control and experimental. Then as the pretest, the teacher assigned a writing task to the control and experimental groups. The task required the learners to write an argumentative report. The report was the participants' personal analyses of the contents they had viewed on TV about an important political issue. The two groups were asked to watch some TV channels devoted to news. The channels introduced to them were Euronews, BBC, VOA, CNN, Reuters, Foxnews, and France 24-En. The participants sent the tests' results to their teacher via email. For coding the pretest scores, the teacher rated the responses by using the IELTS marking scheme for writing. The control group received instructions for critical writing in class without using Instagram. They were studying their coursebooks during the semester which were Evolve 6 and Oxford Word Skills (Upper-Intermediate-Advanced Vocabulary). Moreover, Goatly and Hiradhar (2016), Critical Reading and Writing in the Digital Age: An Introductory Coursebook (2nd edition), was taught in addition to the coursebooks. The treatment lasted for 12 weeks each week for two sessions and each session for 2 h. The control group were asked to watch some TV channels devoted to news. The channels introduced to them were Euronews, BBC, VOA, CNN, Reuters, Foxnews, and France 24-En. The control group were asked to watch the channels daily on TV to view videos about political subjects. An important political issue that the participants had viewed some contents about prior to the upcoming session would become the subject of classroom discussion. The teacher and all the students would participate in the discussion to identify the strategies used for making and presenting the contents in the channels to have the most influential impact on the audiences' minds. Moreover, the participants were required to deliver an argumentative report before the first weekly session every week. The reports were the participants' personal analyses of the contents they had viewed about the predetermined political issue. The reports were delivered to the teacher via email before the first weekly session. The researchers would divide the reports among themselves and comment on them. The reports would be sent back to the participants after the second weekly session. By receiving comments on their reports, the participants would have the opportunity to know their weaknesses and improve their next report. The experimental group received instructions for critical writing in class and via Instagram. They were studying their coursebooks during the semester which were Evolve 6 and Oxford Word Skills (Upper-Intermediate-Advanced Vocabulary). Moreover, Goatly and Hiradhar (2016), Critical Reading and Writing in the Digital Age: An Introductory Coursebook (2nd edition), was taught in addition to the coursebooks. The treatment lasted for 12 weeks each week for two sessions and each session for 2 h. The experimental group, who were all Instagram users, were asked to view @euronews, @bbc, @voa, @cnn, @reuters, @foxnews, and @france24_en on Instagram daily with the aim of watching videos about political subjects presented in the accounts and analyzing the analyses presented there. An important political issue that the participants had viewed some contents about prior to the upcoming session would become the subject of classroom discussion. The teacher and all the participants would participate in the discussion to identify the strategies used for making and presenting the contents in the Instagram accounts to have the most influential impact on the audiences' minds. Moreover, the participants were required to deliver an argumentative report before the first weekly session every week. The reports were the participants' personal analyses of the contents they had viewed about the predetermined political issue. The reports were delivered to the teacher via email before the first weekly session. The researchers would divide the reports among themselves and comment on them. The reports would be send back to the participants after the second weekly session. By receiving comments on the reports, the participants would have the opportunity to know their weaknesses and improve their next report. Additionally, an Instagram account was created by the teacher and the posts, reels, and stories adopted from some Instagram accounts available in Instagram Explore were re-shared there. The experimental group were required to follow the account and participate in the process and interact with their peers and the researchers. When the treatments ended, the teacher assigned a writing task to the control and experimental groups as the posttest. The task required the participants to write an argumentative report. The reports were the participants' personal analyses of the contents they had viewed on TV for the control group, and on Instagram for the experimental group about an important political issue. The control group were asked to watch some TV channels devoted to news. The channels introduced to them were Euronews, BBC, VOA, CNN, Reuters, Foxnews, and France 24-En. The experimental group were required to view @euronews, @bbc, @voa, @cnn, @reuters, @foxnews, and @france24_en on Instagram to check the posts and stories concerning the predetermined political issue. They were supposed to study the political analyses presented in the Instagram accounts and write a piece of argumentative writing about the analyses they had studied on the issue. The participants sent the tests' results to their teacher via e-mail. For coding the posttest scores, the teacher rated the responses by using the IELTS marking scheme for writing. Finally, 15 members of the experimental group were interviewed (Supplementary Appendix C). The focus of the interview was on the participants' suggestions and criticisms of the study. The stages of the procedure can be viewed in Figure 1.

First, the descriptive statistics (including the means and standard deviations) of the tests were calculated for the two groups. Afterward, to answer the research question (1), the Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) was used. In this study, group membership was the independent variable with two levels (i.e. experimental and control) and the participants' scores on the posttest were considered as the dependent variable. Additionally, the learners' marks on the pretest were considered as the covariate to partial out their background knowledge of the educational materials. For answering the research question (2), 15 members of the experimental group were interviewed and their assertions were analyzed. Each interview lasted 30 min which was recorded and transcribed verbatim. The focus of the interview was on the participants' suggestions and criticisms of the study. For answering the research question (3), the experimental group's marks on the posttest were analyzed to find any statistically significant difference between the performances of males and females on the posttest. To this end, males and females were regarded as two separate groups and the Independent Samples t-test was run.

The first research question was “Does any significant difference exist between the writing proficiency of EFL learners who receive mobile-assisted critical writing instructions and EFL learners who are instructed through a traditional approach?”. Before starting the treatments, the pretest was administered to the two groups. Data collected from the participants' scores on the pretest were analyzed. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the pretest.

Table 1 shows the mean scores and standard deviations of the experimental group (M = 15.98, SD = 2.55) and the control group (M = 16.91, SD = 2.20) on the pretest. As it can be viewed from the data presented in Table 1, the performance of the control group was slightly better than their counterparts in the experimental group. To examine whether there was any statistically significant difference between the two groups, the Independent Samples t-test was run. Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the Independent Samples t-test for the pretest.

As viewed in Table 2, the results of the Independent Samples t-test were not significant [t(48) = −1.388, p = 0.149] since the p-value was >0.05. Thus, the participants of the two groups had similar performances on the pretest and were considered at a same level of proficiency.

After the treatments of the study ended, the posttest was administered to evaluate the influence of the instructions on the groups' writing skill. Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics of the posttest.

The descriptive statistics presented in Table 3 show that the experimental group (M = 22.86, SD = 2.40) scored higher than the control group (M = 19.79, SD = 2.10) on the posttest. To ensure that the difference between the mean scores across the groups was statistically significant, the Independent Samples t-test was run. Table 4 shows the descriptive statistics of the Independent Samples t-test for the posttest.

Based on the descriptive statistics presented in Table 4, the value of the Independent Samples t-test was statistically significant [t(48) = 5.69, p = 0.000] since the p-value was lower than 0.05. Thus, receiving mobile-assisted critical writing instructions had a significant positive effect on the performance of the experimental group.

The research question (2) was “What are EFL learners' perspectives on receiving mobile-assisted critical writing instruction?”. To gather qualitative data, 15 participants of the experimental group were interviewed (Supplementary Appendix C). They were selected based on their marks on the posttest. Five of them had scored the lowest, the other five ones were middle-scorers, and the five high scorers of the group constituted the sample for conducting interviews. Five broad themes were identified by a thematic analysis of the participants' assertions in the interviews: (1) using Instagram eased learning, (2) learning by Instagram was interesting, (3) using Instagram was beneficial for enhancing critical awareness, (4) reading and writing comments and reading captions improved writing skill, and (5) the Instagram accounts were good sources for learning formal English. Pseudonyms have been utilized for mentioning the participants' assertions here.

(1) Utilizing Instagram eased learning

Ten of the interviewees declared that utilizing Instagram eased learning writing skill for them. They believed that the Instagram accounts they viewed and the account of the class were good sources of educational materials. Being constantly involved in the learning process was an important factor for memorizing and practicing vocabulary and grammatical structures for them.

Simin: The Instagram accounts that I followed were good sources for learning English and specifically writing skill. I liked reading the captions and comments. In the account of our class, I could interact with others by writing. I learned new vocabulary and grammatical structures. As I was online most of the time during a day, I had a very good opportunity for practicing writing skill constantly.

(2) Learning by Instagram was interesting

Nine of the participants stated that learning by Instagram was enjoyable and interesting. They declared that the innovation of mobile-assisted learning prevented the process from becoming monotonous and boring.

Melika: Using Instagram was very interesting. I really enjoyed having interactions with my teacher, peers, and other Instagram users. I like to have fun while learning.

(3) Using Instagram was beneficial for enhancing critical awareness

All of the participants asserted that viewing the Instagram accounts and receiving critical thinking instructions from their teacher contributed to improvement in their critical thinking ability and enhanced their critical awareness.

Parsa: Prior to participating in this study, I knew a little about the concept of critical thinking. Viewing the Instagram accounts and receiving critical writing instructions enhanced my critical awareness and equipped me with critical thinking skills. My teacher was very hardworking and I appreciate his efforts specifically in running the Instagram account of our class.

(4) Reading and writing comments and reading captions improved writing skill

The Instagram accounts and the account of the class contained posts which all had captions. Reading captions was a very good practice for learning writing. In addition, the participants could read comments and write comments on all the posts. Writing comments was also an opportunity for having interactions with Instagram users. All of the participants declared that this aspect of instructions was very effective in improving their writing skill.

Vahid: Reading the captions of the Instagram posts was very beneficial for improving my writing skill. The captions contained new vocabulary and various grammatical structures. Reading and writing comments also helped me a lot. The interactions that I had with my classmates and teacher in the account of our class were very effective for learning in this course.

(5) Instagram accounts were good sources for learning formal English

Eleven of the participants stated that the Instagram accounts were important sources for learning formal English. Political analyses and the news contained very formal English which were insightful for the EFL learners. Distinguishing the differences between formal and informal English helped them learn to have appropriate interactions in both formal and informal contexts.

Pegah: Press agencies constitute a main part of policy. The language used in policy is very formal and different from the language used in informal social contexts. I knew about the differences, but by viewing the Instagram accounts I learned a lot more. Knowing formal English is of great significance for academic success and the accounts I viewed were very good sources of formal English.

Regarding the participants' assertions, it could be concluded that they had positive perceptions of the treatment they had received.

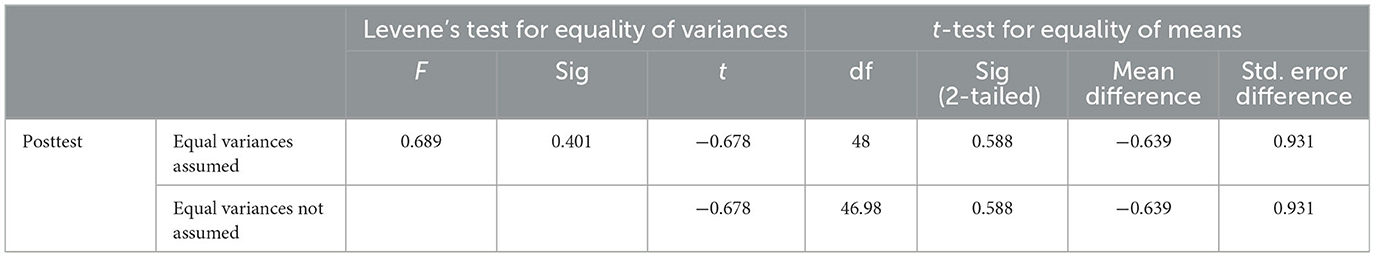

The third question of this study was “Do male and female EFL learners perform differently on writing tests after receiving mobile-assisted critical writing instruction?”. To investigate whether any substantial difference existed between the female EFL learners and the male EFL learners in terms of their performances on the posttest after receiving critical writing instructions, the Independent Samples t-test was run. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 5.

As it is evidently viewed in Table 5, the mean scores for the male and female learners on the posttest were 22.93 and 22.79 respectively. To investigate whether the difference was statistically substantial, the Independent Samples t-test was run. Table 6 shows the descriptive statistics of the Independent Samples t-test for the females and males' marks on the posttest.

Table 6. The result of the independent samples t-test for males and females' scores on the posttest.

As viewed in Table 6, the value of the Independent Samples t-test was not statistically significant [t(48) = −0.67, p = 0.588] since the p-value was >0.05. Thus, there was not a significant difference between the performance of the female EFL learners and the male EFL learners on the posttest of the study.

This research aimed to examine the influence of mobile-assisted critical writing instructions on EFL learners' writing skill in language institutes. The first question that this study tried to answer was “Does any significant difference exist between the writing proficiency of EFL learners who receive mobile-assisted critical writing instructions and EFL learners who are instructed through a traditional approach?”. The participants' scant knowledge of critical thinking resulted in their incompetency to perform well on the pretest. They were not able to reflect on the analyses they had studies and had presented their personal viewpoints like writing diaries instead of critical analysis of the discourse. The students failed to write coherently and were not able to logically back their claims by evidence. They had used their personal knowledge of the political issues and presented them in their writing, while they were expected to analyze the information and the analyses they had viewed concerning the political issue at hand. They had considered the test to be just an informal piece of writing and had scant knowledge of the concept of critical writing. The analyses they had presented lacked the critical perspective, perhaps being familiar with critical analysis of texts from school age and in their L1 could help them to perform better when writing critically in English as a foreign language. This could be the evidence showing the significance of integrating critical thinking instructions into school curricula. Using Instagram provided the learners with the opportunity to receive authentic materials, learn how to use English formally, and have interactions with their teacher and peers. The participants close mean scores on the pretest showed that they were nearly at the same level of writing proficiency. But, their different mean scores on the posttest revealed the fact that receiving mobile-assisted critical writing instructions placed the experimental group in a superior position compared with that of the control group. Regarding the performances of the control group on the pretest and posttest, it could be inferred that their performance improved to some extent on the posttest. Perhaps during the interval between the pretest and the posttest, they had worked on their writing skill and studied independently in the field of critical discourse analysis of political texts as well as receiving instructions based on a traditional approach. Furthermore, the experience of taking the pretest should not be ignored. The experience provided the control group with the opportunity to use their personal experience of taking the first test and perform better on the second one. Unfortunately, critical thinking instruction has not received its due priority in curricula of language institutes in Iran. Critical thinking instruction has been ignored and consequently it has not been the focus of explicit instruction. Time constraints might have been the major obstacle preventing teachers from teaching critical thinking in language institutes; since it is a burdensome task for teachers to devote a lot of time to teaching critical thinking as well as teaching the coursebooks. Learning critical thinking is a longitudinal process and requires EFL learners to practice a lot and have high levels of motivation and interest. To teach critical thinking instructions, teachers need to receive the pertinent instruction in teacher training courses in advance. Teachers' not having adequate conception of critical thinking surely prevents them from teaching it to their students. Overall, the experimental group performed much better than the control group on the posttest. Similar to our findings, Erarsalan (2019) reported that analyzing the participants' achievement scores revealed that utilizing Instagram positively influenced their language learning. Adekantari et al. (2020) reported that Instagram-assisted instruction had a positive influence on the students' critical thinking skills. They concluded that Instagram could be utilized as a supplementary tool for learning. Arlinda et al. (2022) reported that utilizing Instagram could improve the learners' critical and creative thinking skills. Khulel (2022) reported that utilizing Instagram helped the students to improve their writing skill. Our findings were similar to the results of the study conducted by Ghanbari and Salari (2022) who investigated the difficulties the Iranian EFL undergraduate students faced in writing argumentative essays. Nevertheless, our study is different from theirs since we delivered critical writing instructions to both groups to improve their writing skill. Both groups got better marks on the posttest, but the experimental group's progression was more significant in comparison with the control group. Contrary to our finding, Awada et al. (2019) reported that the utilization of technology for delivering instructions to the participants was just effective for improving the performance of the low-achievers. They stated that the high-achievers and the middle-achievers did not benefit substantially from using technology. In our study, the participants' English proficiency was precisely checked in advance and they were all at the same level. Nonetheless, still there were high-scorers, middle-scorers, and low-scorers with insignificant differences among their marks. The important point was that utilizing Instagram for learning critical writing significantly improved the marks of all the members of the experimental group on the posttest. In this study we limited our focus to the Instagram accounts which were devoted to news agencies. Since the political and social analysis presented there were useful for teaching critical thinking principles. However, care should be taken that selecting Instagram accounts depends on the learners' English proficiency level. For instance, it may not be possible to use the Instagram accounts belonging to news agencies for training ESL/EFL learners at low English proficiency levels. To explain critical thinking principles, even the Instagram accounts with contents in the learners L1 could be utilized. The learners would become familiar with the principles and after that more advanced instructions could be delivered in English. Making use of various sources of educational materials by using different Instagram accounts also makes the process of learning more interesting to learners.

The second research question was “What are EFL learners' perspectives on receiving mobile-assisted critical writing instruction?”. Fifteen members of the experimental group were interviewed as the final phase of the study. Five broad themes were identified by a thematic analysis of the participants' assertions in the interviews: (1) using Instagram eased learning, (2) learning by Instagram was interesting, (3) using Instagram was beneficial for enhancing critical awareness, (4) reading and writing comments and reading captions improved writing skill, and (5) the Instagram accounts were good sources for learning formal English. Overall, the experimental group had positive perceptions of the treatment. Similarly, Rahimi and Sharififar (2015) reported that receiving critical thinking instructions enhanced their participants' motivation for learning English. Taghinezhad et al. (2018) also found that there was a significant improvement in the experimental group's dispositions toward utilizing critical thinking strategies. Erarsalan (2019) reported that the participants had positive attitudes toward employing Instagram for pedagogical purposes and language learning. Gonlul (2019) reported that the participants' overall opinions about utilizing Instagram were positive and they virtually regarded Instagram as a motivating and interesting mobile tool. They also considered Instagram as an easy and convenient way of improving overall communication skills. Adekantari et al. (2020) reported that the students gave a positive response to the utilization of Instagram especially for writing assignments. The students considered Instagram as a good learning media for improving their writing skill. Ghanbari and Salari (2022) investigated the students' perceptions of argumentative writing by utilizing a questionnaire. Nevertheless, they did not investigate the students' perceptions of the writing instructions they had received during their academic studies. Thy declared that the students had scant knowledge about the concept of argumentative writing. This point is similar to our findings as our participants were not competent and experienced in terms of critical writing. These findings showed the significance of teaching critical thinking instructions in EFL pedagogical contexts in Iran.

The third research question was “Do male and female EFL learners perform differently on writing tests after receiving mobile-assisted critical writing instruction?”. After receiving critical writing instructions, male and female members of the experimental group had close mean scores on the posttest and the difference was not statistically significant. Therefore, the students' gender did not have any effects on their writing proficiency after receiving mobile-assisted critical writing instructions. However, care should be taken that the number of the participants in the experimental group was small and the number of males and females were unequal. Any generalizations from our conclusions should be considered carefully and declared with caution. Similar to our finding, Hashemi et al. (2014) reported that gender did not influence the EFL learners' argumentative writing achievements. Likewise, Malmir and Shoorcheh (2012) reported that explicit teaching of critical thinking had the same effect on female and male EFL learners' critical thinking ability. Kang (2015) found no significant difference between female and male learners in terms of their critical thinking ability after practicing critical thinking skills. Nayernia et al. (2020) examined the influence of gender on EFL learners' argumentative writing development. The results of the research showed that gender did not play a significant role in the participants' argumentative writing improvement. In contrast to our findings and the findings of the aforementioned studies, Rahimi and Sharififar (2015) reported that receiving critical thinking instructions affected the female EFL learners slightly more than the male EFL learners. We investigated the influence of gender on our participants' performances on the posttest in order to know whether the two genders needed different approaches for receiving critical writing instruction to excel in writing skill. Future studies may investigate this issue with different samples of participants and equal number of males and females. Fuad et al. (2017) reported that the males and females had equal conceptual knowledge, but the male learners performed better at problem-solving compared with the female learners. Yenice (2011) reported that gender had a significant role in the learners' critical thinking dispositions which benefited the females. The merits of the treatment were mentioned by both genders in their interviews, but the important point was the different features that they mentioned. We were willing to identify the features which made the instructions effective for each gender. Identifying these features would help the educators to adjust or change their approaches and makes the mobile-assisted instruction more effective for training males or females. This point is even more important when males and females are not taught together. Since the opportunity for providing the learners with the most effective instruction becomes possible. As the results showed, we could not find any statistically significant differences between males and females performances on the posttest. It could be concluded that the males and females did not need to receive specialized mobile-assisted critical writing instructions.

In Sociocultural theory, Vygotsky (1978) believed that there were two kinds of stimulus for enhancing knowledge acquisition: (a) the mediational effect and (b) Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). The mediational effect referred to individuals' interactions with their environment which could build new knowledge and concepts. While, Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) referred to individuals' ability to develop their metacognitive abilities through having interactions with their peers. The student-centered approach employed in this study is the most preferable way to stimulate ESL/EFL learners to collaborate for learning problem-solving skills. In this approach, teachers are regarded as facilitators who provide their learners with opportunities to develop their critical thinking skills rather than dispensers of knowledge. Besides, learners are considered as problem-solvers who utilize their critical thinking skills in the learning activities. The findings of this study showed that language learning based on constructivism theory still should be investigated. Constructivism theory creates conception based on the knowledge obtained from students' learning experiences and the environment. This makes the learning process more meaningful. This way of learning is manifested in the form of collaboration for obtaining knowledge based on reality and students' real life practices and experiences (Iskander, 2014; Jin, 2017).

Our findings showed a positive correlation between the EFL learners' critical awareness and their competence in argumentative writing and their perceptions of it. Writing can be considered as the most challenging skill for language learners since mastering it requires adequate instructions and competence in other language skills, too. Therefore, language teachers should integrate critical writing instructions in their writing courses to facilitate the process of learning for students and help them to improve their writing skill. In this study just one faculty was investigated. Future studies may examine EFL learners' critical thinking ability in relation to listening, speaking, and reading. This study was conducted in the context of language institutes. Future studies may be conducted in other contexts such as schools and universities. In this study, the EFL learners' perceptions of the mobile-assisted critical writing instructions were investigated. Future studies may investigate teachers' perceptions of mobile-assisted critical writing instructions. The participants of this study had positive attitudes toward receiving critical writing instructions. It is recommended for curriculum designers to integrate critical writing instructions in their curricula to assist learners master writing skill successfully. It is also recommended for educational systems, particularly in Iran, to set up workshops and pre/in-service teacher training courses for teachers to teach critical writing instructions to them. Curriculum designers should put more emphasis on incorporating critical writing instructions in EFL programs at early stages of English learning. Employing this approach may improve EFL learners' writing skill in subsequent stages of English learning. Coursebook writers are also encouraged to make use of critical writing principles in preparation of the materials. Students should also pay more attention to developing their writing skill by utilizing critical writing instructions that they receive. This study was conducted during a short period of time and the time devoted to teaching via Instagram was limited. Future studies may be conducted during a longer period of time; moreover, the number of sessions held via Instagram and the time devoted to each session may be increased. The Instagram accounts utilized in this study were limited to the accounts belonging to news agencies. In future studies, Instagram accounts other than the ones we utilized may be used. There are accounts which are not particularly devoted to news and still may be used for analyzing political and social subjects.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

The studies involving humans were approved by Fakourian Ethics Committe of Education Office. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

MZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HW: Writing – review & editing. NY: Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1465765/full#supplementary-material

Abdollahzadeh, E., Amini Farsani, M., and Beikmohammadi, M. (2017). Argumentative writing behavior of graduate EFL learners. Argumentation 31, 641–661. doi: 10.1007/s10503-016-9415-5

Adekantari, P., and Su'ud Sukardi. (2020). The influence of Instagram-assisted project-based learning model on critical thinking skills. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 10, 315–322. doi: 10.36941/jesr-2020-0129

Al-Ali, S. (2014). Embracing the selfie craze: exploring the possible use of Instagram as a language learning tool. Issues Trends Educ. Technol. 2, 1–16. doi: 10.2458/azu_itet_v2i2_ai-ali

Alandejani, J. A. (2021). Perception of instructors' and their implementation of critical thinking within their lectures. Int. J. Instr. 14, 411–426. doi: 10.29333/iji.2021.14424a

Ali, G., and Awan, R. N. (2021). Thinking based instructional practices and academic achievement of undergraduate science students: exploring the role of critical thinking skills and dispositions. J. Innov. Sci. 7, 56–70. doi: 10.17582/journal.jis/2021/7.1.56.70

Al-Jarrah, T. M., Al-Jarrah, J. M., Talafhah, R. H., and Mansor, N. (2019). The role of social media in development of English language writing skill at school level. Int. J. Acad. Res. Progress. Educ. Dev. 8. doi: 10.6007/IJARPED/v8-i1/5537

Alnujaidi, S. (2016). Social network sites effectiveness from EFL students' viewpoints. Engl. Lang. Teach. 10, 39–49. doi: 10.5539/elt.v10n1p39

Alotaibi, K. N. R. (2013). The effect of blended learning on developing critical thinking skills. Educ. J. 2:176. doi: 10.11648/j.edu.20130204.21

Altinmakas, D., and Bayyurt, Y. (2019). An exploratory study on factors influencing undergraduate students' academic writing practices in Turkey. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 37, 88–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2018.11.006

Al-Zou'bi, R. (2021). The impact of media and information literacy on acquiring the critical thinking skill by the educational faculty's students. Think. Skills Creat. 39:100782. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100782

Arlinda, C. P., Marianti, A., and Rahayuningsih, M. (2022). The implementation of project-based learning model with instagram media towards students' critical thinking and creativity. Unnes Sci. Educ. J. 11, 9–16. doi: 10.15294/usej.v11i1.46495

Ary, D., Jacobs, L. C., Sorenson Irvine, C. K., and Walker, D. A. (2019). Introduction to Research in Education, 10th Edn. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Ataç, A. B. (2015). From descriptive to critical writing: a study on the effectiveness of advanced reading and writing instruction. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 199, 620–626. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.588

Awada, G., Burston, J., and Ghannage, R. (2019). Effect of student team achievement division through WebQuest on EFL students' argumentative writing skills and their instructors' perceptions. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 33, 275–300. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2018.1558254

Badenhorst, C. M., Moloney, C., and Rosales, J. (2020). New literacies for engineering students: critical reflective-writing practice. Can. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn 11. doi: 10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2020.1.10805

Bean, J. C., and Melzer, D. (2021). Engaging Ideas: The Professor's Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

Behar-Horenstein, L. S., and Niu, L. (2011). Teaching critical thinking skills in higher education: a review of the literature. J. Coll. Teach. Learn. 8. doi: 10.19030/tlc.v8i2.3554

Beniche, M., Larouz, M., and Anasse, K. (2021). An analysis of major difficulties Moroccan engineering students encounter in argumentative essay writing: the case of preparatory classes of higher engineering schools. Int. J. Lang. Lit. Stud. 3, 119–130. doi: 10.36892/ijlls.v3i4.752

Bezanilla, M. J., Fernández-Nogueira, D., Poblete, M., and Galindo-Domínguez, H. (2019). Methodologies for teaching-learning critical thinking in higher education: the teacher's view. Think. Skills Creat. 33:100584. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2019.100584

Boblett, N. (2012). “Scaffolding: defining the metaphor,” in Teachers College, Columbia University Working Papers in TESOL and Applied Linguistics, Vol. 12, 1–16.

Bruner, J. (1985). “Vygotsky: a historical and conceptual perspective,” in Culture, Communication, and Cognition: Vygotskian Perspectives, ed. J. V. Wetsch (London: Cambridge University Press), 21–34.

Burston, J. (2013). Mobile-assisted language learning: a selected annotated bibliography of implementation studies 1994-2012. Lang. Learn. Technol. 17, 157–225.

Burston, J. (2014). MALL: The pedagogical challenges. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 27, 344–357. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2014.914539

Çakmak, F. (2019). Mobile learning and mobile assisted language learning in focus. Lang. Technol. 1, 30–48.

Carroll, J., and Wilson, E. (2014). The Critical Writer: Inquiry and the Writing Process. London: Libraries Unlimited.

Carstens, A. (2012). Using literacy narratives to scaffold academic literacy in the bachelor of education: a pedagogical framework. J. Lang. Teach. 46, 9–25. doi: 10.4314/jlt.v46i2.1

Colthorpe, K., Sharifirad, T., Ainscough, L., Anderson, S., and Zimbardi, K. (2018). Prompting undergraduate students' metacognition of learning: implementing “meta-learning” assessment tasks in the biomedical sciences. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 43, 272–285. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2017.1334872

Cui, R., and Teo, P. (2023). Thinking through talk: using dialogue to develop students' critical thinking. Teach. Teach. Educ. 125:104068. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2023.104068

Davies, M. W. (2013). Critical thinking and the disciplines reconsidered. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 32, 529–544. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2012.697878

Dean O'Loughlin, V., and Miller Griffith, L. (2020). Developing student metacognition through reflective writing in an upper-level undergraduate anatomy course. Anat. Sci. Educ. 13, 680–693. doi: 10.1002/ase.1945