- Department of English, School of Social Sciences and Languages, Vellore Institute of Technology, Vellore, India

Sustainability has become an essential factor in the field of education as the world evolves toward digitization. Technology is a valuable educational tool for sustainable development and it is rapidly adopted worldwide, leading to substantial educational innovations and findings. Technology such as Interactive Whiteboards, Learning Management Systems (LMS), and Mobile Assisted Language Learning (MALL), enhance self-directed learning among the learners. According to the goals of UNESCO, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goal-4 (SDG4) focuses on quality education that endorses equity and equal opportunity for all. Mobile Learning is an educational method that can improve a teaching-learning context. However, limited studies have focused on utilizing MALL in the context of self-directed learning. The present study discusses the use of mobile applications for sustainable language learning. It provides a systematic review of the findings of 16 empirical studies published between 2019 and 2023 from Scopus and the Web of Science, based on PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) 2020. The study analyzes the use of mobile apps for self-directed learning and highlights the importance of digital abilities in promoting lifelong learning. The result indicates the benefits of self-directed learning in promoting sustainable learning and discusses the potential of Mobile-Assisted Language Learning (MALL) in providing lifelong learning opportunities.

1 Introduction

The term “sustainable learning” in education refers to an educational philosophy that deals with the curriculum, instructional strategies, and learning techniques. It gives students the knowledge and abilities they need to learn in various contexts, such as constructivism and contextual learning. Sustainable Learning in Education (SLE) aims to equip students with the necessary skills and information to reinvent themselves (Ben-Eliyahu, 2021). Sustainable Learning (SL) assists learners and educators in overcoming challenges and changing circumstances, strengthening their capacity to contribute to a sustainable society. It has been used in various educational and professional situations. It also teaches learners to be curious, to renew, rebuild, reuse, and challenge the difficulties they experience. The four key pillars of sustainable education are “revitalizing and relearning,” “individual and collaborative learning,” “active learning,” and “transferability” (Jeong, 2022). Sustainable language learning refers to more lasting, adequate, adaptable, enthusiastic, and enjoyable learning (Mortazavi et al., 2021). In recent years, the world has undergone a digital transition, so the regular tasks of people’s daily lives have become entwined with technology. The utilization of technology in the field of education has changed significantly which serves as an instructional tool for lifelong learning. MALL enhances individualized, self-directed learning, providing numerous advantages for sustainable learning, including convenience, adaptability, contextualization, and real-time feedback.

Integrating MALL as a pedagogical strategy in education has become increasingly popular, especially for improving English language proficiency. The accessibility of mobile devices offers the ability to support contextualized learning, making the learning experience relevant to learners’ situations (Ameri, 2020). MALL has unique ability to foster enthusiasm in educational activities and connect learners with real-world experiences (Latypova et al., 2018). It expands “possibilities regarding student autonomy by providing a way to study whenever and wherever suits them and access an infinite variety of unique multimedia information.” It can be used in the formal and informal learning context because it offers flexible language acquisition methods that can happen both inside and outside the classroom (Sulaiman, 2019). Mobile learning is increasingly vital for teaching and learning English as a Second Language. Implementing mobile technologies into language learning has supported the concepts of mobility, social connectivity, and individualism (Chinnery, 2006). The advancement of technology has had a significant influence on language learning with the integration of mobile technologies (Chen and Hsu, 2008).

Incorporating digital devices into the language acquisition process, such as mobile phones or tablets, has the potential to be an innovative method of language learning. This ability arises from various aspects, including portability, versatility, and network connectivity (Kim and Kwon, 2012). Educators and researchers focused on integrating digital technology into the classroom due to the widespread incorporation of mobile phones into the daily activities of tertiary-level learners. The pervasive use of smartphones among tertiary-level students has prompted educators to study the potential of this digital technology to foster students’ eagerness to learn and sustain their learning experiences (Cavus and Ibrahim, 2009). Furthermore, MALL engages and encourages students, paving a path toward improved learning. It can also help learners overcome issues in language learning. It encourages individuals to demonstrate mastery in different language acquisition domains, such as listening, speaking, reading, writing expression, and grammar (Almudibry, 2022). It also allows learners to analyze their learning progress and outcomes by providing rapid feedback and self-assessment tools (Al-Shehri, 2011). It makes learning English more fascinating, engaging, and possibly independent for its learners by using real-world examples, interactive information, and social interactions (Loewen et al., 2019). The use of Web 2.0 apps can aid learners’ understanding of the language and literature with the availability of several opportunities for learning, such as those for exploring and investigating, writing, producing, reflecting on, evaluating, performing, and presenting, and, most crucially, collaborating (Sönmez and Çakır, 2020). The systematic review analyzes the use of mobile technology and the effects of sustainable language learning on self-directed language learning among higher education learners. Therefore, to encourage language learning, the function of MALL should be defined, which makes self-directed learning comfortable and accessible.

1.1 Research objective and research questions

The primary objective of this systematic review is to

1. Examine the role of MALL and its efficacy in promoting self-directed learning for sustainable language learning.

2. Promote the effective use of MALL on learners’ motivation, engagement, and autonomy in language acquisition.

RQ1: How does MALL facilitate self-directed Learning for sustainable language learning in a pedagogical context?

RQ2: Does MALL promote motivation, engagement, and autonomy of the language learners?

2 Review of literature

Research in MALL has been influenced by the technological development in language learning. Recent innovations have resulted in significant studies on the essential role of mobile apps in language learning. The flexibility of mobile learning enables learners to learn in various environments. Educators have comprehended the significance of fostering creative thinking skills among college graduates by integrating technology into teaching and learning contexts to enhance learners’ abilities (Latypova et al., 2018). Learners use mobile technology to learn a second language outside the classroom, which allows them to increase their exposure to the English language (Lai et al., 2022b). According to Klopfer et al. (2003) and his colleagues, mobile gadgets have the following qualities: mobility, social engagement, context sensitivity, connection, and individuality (Klopfer et al., 2003). The portability of mobile phones has introduced new techniques that can mold learning styles and pedagogies that might become increasingly personalized and allow learners to acquire knowledge (Stockwell, 2022). Learners can use mobile devices to customize and adjust their learning process based on their individual needs and interests. The FluentU mobile app provides real-life content for learners to cultivate practical communication skills and facilitate confidence in social interactions. Its accessibility features allow learners to engage with other learners and practice their language skills in various settings (Altynbekova and Zhussupova, 2020). Mobile applications such as “Duolingo,” “Orai,” “Cake Application,” and “Speakify AI- Speak English” provide access to language experts and native speakers through virtual classrooms. MALL enhances language experience and nurtures social connectivity among the learners to develop their learning.

Regarding context sensitivity of learning, mobile technology enables learners to connect language skills with real-world and cultural contexts (Chen and Li, 2010). MALL enables language educators to utilize the unique features of mobile applications, for instance, the “Practice English Speaking” app offers practical exercises and real-time feedback, making it an excellent tool for improving speaking skills through interactive practice. In contrast, the “Ace Fluency” app focuses on providing tailored learning experiences combined with real-time interactions. Additionally, the “Speak X” app utilizes advanced AI technology to promote personalized learning and offer instant feedback, appealing to users who favor a tech-driven approach. Each of these applications has unique strengths: “Practice English Speaking” emphasizes hands-on exercises, “Ace Fluency” prioritizes customized sessions, and “Speak X” leverages AI to enhance the learning experience. This application is revolutionizing English language learning by utilizing artificial intelligence (AI) to provide users with a personalized and immersive experience. AI instructors provide tailored learning approaches, immediate feedback, and gamified elements that increase engagement and enhance the efficiency of the learning process (Mittal, 2024). Figueiredo (2023) indicates that mobile applications may provide individualized, genuine, and exciting language learning, particularly for formal education. The activities allow learners to control their learning and access authentic and immersive content in the target language through gamification within applications like “Hello English,” “Duolingo,” “YouTube,” and “Spotify” for mobile-assisted language acquisition. Shortt et al. (2021) conducted an in-depth evaluation of a study from 2012 to 2020. This study extensively evaluated the methodological tactics used in gamified mobile applications. The findings of the study indicated that the use of gamification in “Duolingo” has the ability to enhance language learning. Hsu and Liu (2021) explored the influence of mobile technology on language learning and found that implementing M-learning can enhance learning outcomes and facilitate cross-cultural collaboration in language learning. Educators who encourage using mobile devices for oral communication can significantly improve students’ second language learning. This adaptation encourages self-direction and self-correction in educational settings that benefit the desires and interests of learners.

2.1 Self-directed learning and MALL

Self-Directed Learning (SDL) benefits the second language learners to flourish within and outside the classroom. It has a long history of being considered a design aspect of the learning environment and a learning process. Naturally, SDL settings foster learners’ self-directed talents, which they apply to various learning contexts (Lai, 2015). Researchers and linguists are becoming more interested in investigating the potential benefits of self-directed language learning among the learners and its relationship with their language proficiency and retention capabilities. The significance of self-directed learning in higher education lies in its ability to empower learners to engage in independent learning utilizing diverse resources. In the context of SDL, students acquire the ultimate authority and management over their learning activities and processes (Loyens et al., 2008). When using mobile devices, learners prioritize personalization over authenticity and interaction. In addition, the selection of tools depended on the particular features and purposes of the learning activities. Self-directed learning develops when learners cultivate essential skills and attitudes, such as self-reflection, self-control, and effective communication. Learners were given more freedom and independence in determining their preferred learning speed, theme, place, and time (Lai and Zheng, 2017).

Several studies were conducted on self-directed learning through MALL for sustainable learning. Liu et al. (2023) investigated the interaction between SDL behaviors and the influence of creative performance in the field of design education. According to the study, SDL behaviors such as goal setting, self-evaluation, and self-reflection positively impacted innovative performance. The study offered insightful information on how SDL methods could improve creativity among the learners in the context of education. Hsu and Liu (2021) analyzed the influence of mobile technology on improving oral communication in foreign languages. The findings provide valuable guidance for educational practitioners, learners, and system designers on effectively utilizing mobile technology for language learning. Beatty (2013) proposed a model to examine 28 empirical studies conducted between 2010 and 2019. Mobile technology facilitates student-centered, self-regulated, collaborative, and strategy-driven learning, augmenting oral, cognitive, and emotional competencies. According to the study by Beatty (2013), employing online popular culture in informal learning can promote autonomy among the learners. It also engages learners in activities such as searching, commenting, and sharing information, which contribute to developing a sense of responsibility among young adults toward their learning progress. It is essential to provide opportunities to prepare students to become self-directed (Lim Razali and Samad 2018).

Tram et al. (2024) investigate the factors influencing ‘ChatGPT acceptance in self-directed English language learning’ and explore its potential in enhancing language learning. A multi-methods approach is employed by including a systematic review of 40 empirical articles, a quantitative survey of 344 English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners, and 19 semi-structured interviews. The results of the study proved that the continued use of ChatGPT has developed interactivity, enjoyment, trust, and subjective norms. Educators can use these insights to better integrate ChatGPT into their curricula to support diverse language skills and to engage the learners effectively. They also provide concrete guidance for enhancing the design and implementation of AI chatbots into language learning contexts.

Incorporating mobile applications can make learning fun and engaging at the same time, it helps learners retain new knowledge. Recognizing the self-directed learning process for effectively using mobile technology is crucial, as it encompasses various levels of intentionality and cognitive complexity. Low-cognitive methods have been more frequently reported than high-cognitive ones (Cavus and Ibrahim, 2009). Lai et al. (2022a) conducted a survey review that explored mobile technology usage among university students. The results indicated that attitude, subjective norm, and self-regulation abilities are essential to students’ intention and behavior toward using mobile technology for language learning. The research further revealed that self-regulation abilities have a moderating role in the association between intention and behavior. The current systematic review determines the effect of self-directed learning using mobile apps on sustainable language learning.

3 Methodology

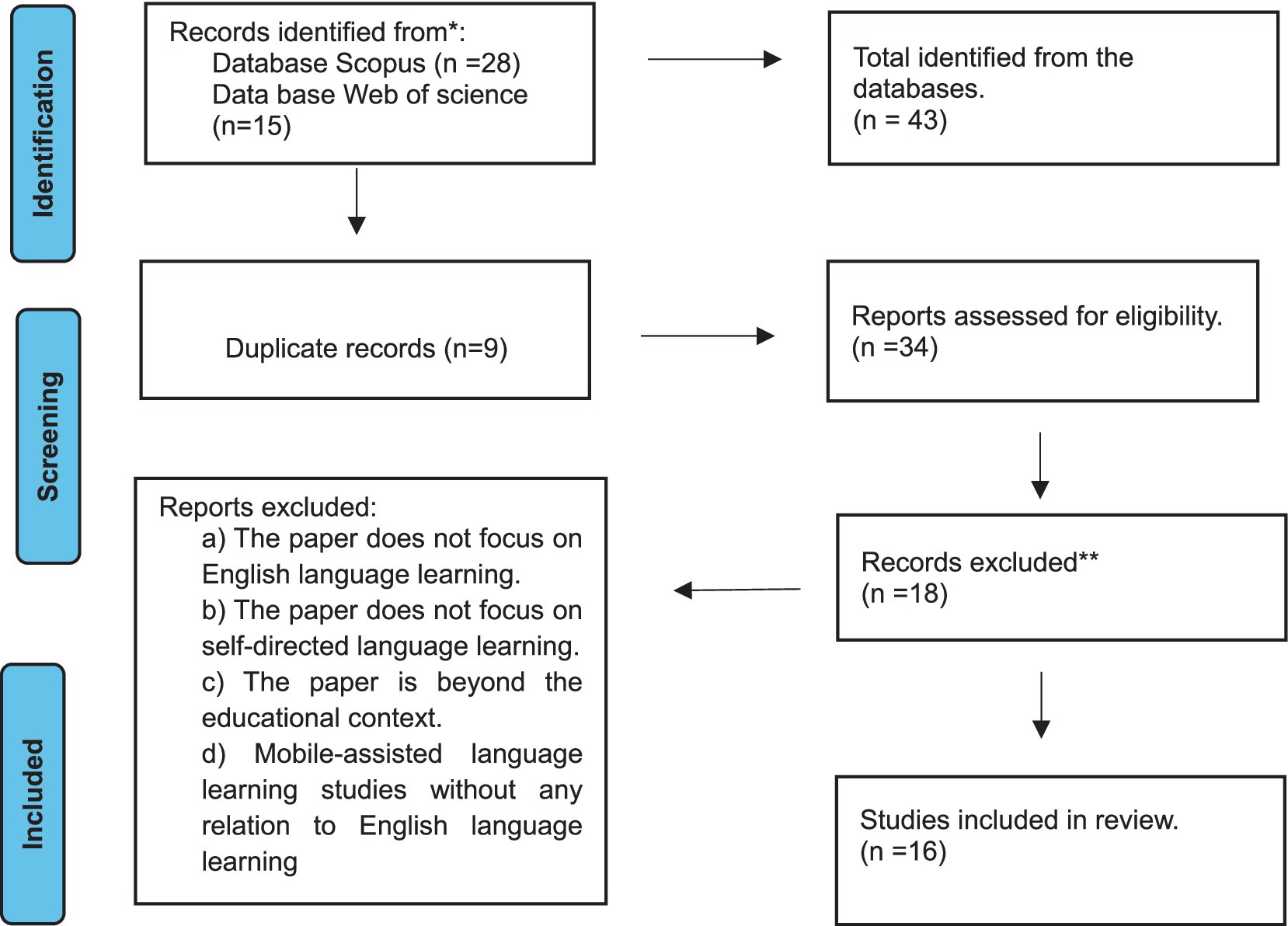

The major focus of this research is to identify the critical concepts of MALL in self-directed learning and their impact on improving language acquisition in second language learners. The current review included 43 selected articles using an adapted version of the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) coding scheme guidelines, as shown in Figure 1 (Page et al., 2021). The articles were obtained from the Scopus and Web of Science databases from 2019 to 2023. Though there are articles on Mobile Assisted Language Learning in other databases like Eric, Science Direct, Taylor and Francis, and Sage, they do not deal with self-directed language learning for developing sustainable language learning. This period provided valuable insights into the emergence of mobile applications, significant technological advancements, and a growing focus on MALL for education, which contributed to establishing a more robust foundation for the future of learning. Articles published in 2019 have been cited more frequently, suggesting that a number of influential research studies were conducted in the MALL field during this year (Dou et al., 2024). The Scopus and Web of Science databases consistently emphasize language learning and technology, including high-impact studies that conduct systematic reviews on MALL.

Figure 1. A systematic review using the PRISMA method, adapted from Page et al. (2021).

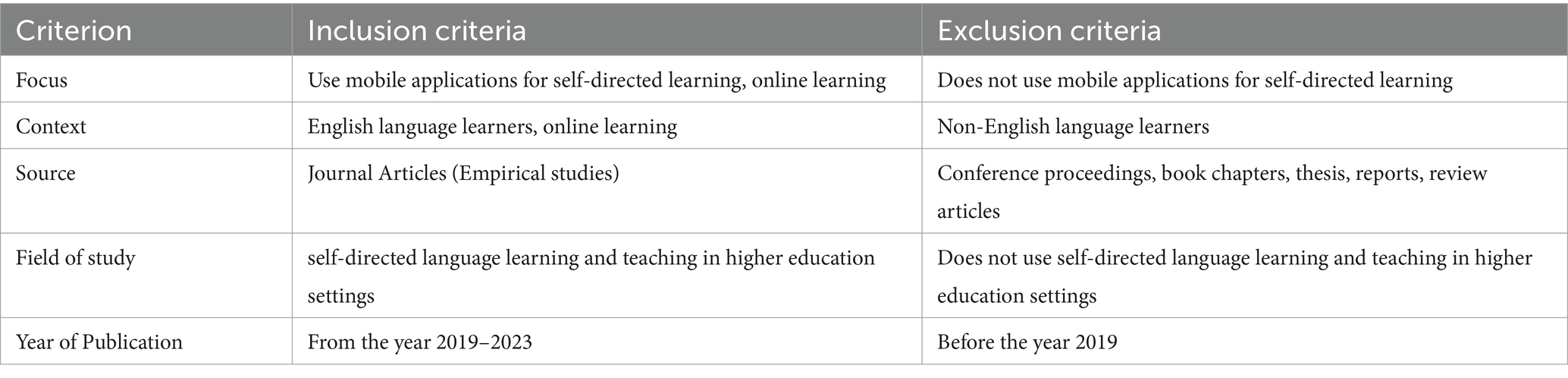

The search executed from the databases mentioned above identified 43 research articles. In the initial screening phase, 9 duplicates were identified, and they were excluded from the study, resulting in 34 articles. In the second screening phase, titles and abstracts were evaluated to eliminate unrelated articles and some articles which do not focus predominantly on English language learning or self-directed language learning are also excluded. As a result, 18 articles were excluded in this phase and the remaining articles were considered. Finally, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria in the screening process provided 16 articles and they are examined for the systematic review focusing on MALL, self-directed learning, and sustainable language learning, as shown in Table 1.

The search criteria using the phrase “MALL,” OR “Mobile-Assisted Language Learning,” “Self-directed language learning,” AND “Mobile learning,” AND “Sustainable language learning,” AND “Self-directed learning using Mobile-assisted language learning” AND “Autonomous Learning, “AND “Language apps” AND “Lifelong Learning” AND English AND language AND teaching are used as the search criteria. The terms are connected by applying the Boolean operator (n = 43; MacFarlane et al., 2022). The reviewed article focused on specific inclusion criteria such as “Online Learning,” “Blended learning,” and “Classroom Use” and also examined the efficacy of MALL in facilitating self-directed learning for language learners. Total identified from the databases.

(n = 43)

4 Results

The results indicate the trends in mobile-assisted language learning for sustainable language learning from 2019 to 2023. Based on the research question, the present review analyzed the use of mobile application which aids self-directed learning.

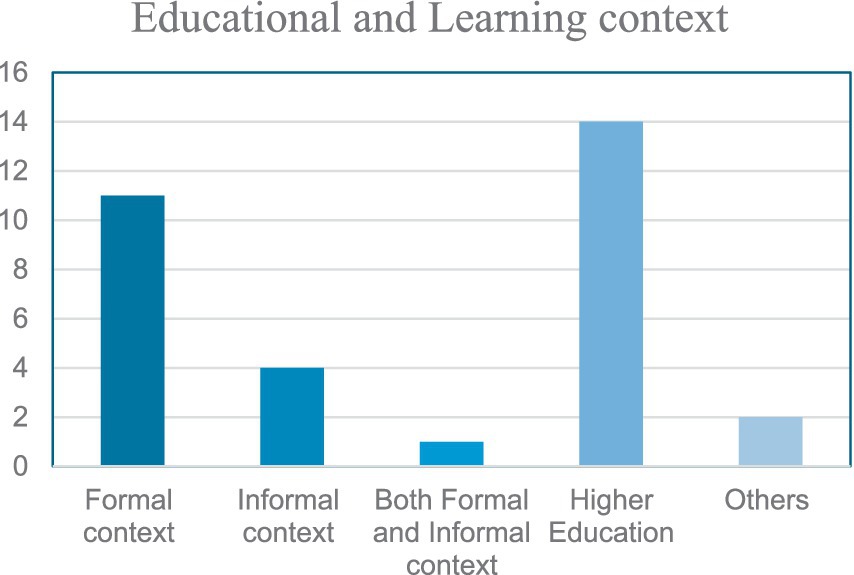

4.1 Educational and learning context

The education context includes the structure and organization of the educational system, particularly designed to attain specified criteria and goals. Institutions, such as universities, colleges, and other post-secondary colleges, play a crucial role in the educational context (Yousif et al., 2022). Learning context refers to how an individual obtains new knowledge or skills. Formal and informal learning play major roles in the learning context (De Figueiredo, 2005). The data findings of the current study suggest that learners use digital technology as an instructional aid in higher education. The result of the study also identified that MALL has effectively engaged university students. The usage of mobile devices has prompted extensive research in higher education, as shown in Figure 2. Limited research has been conducted on the elementary level (Jeon, 2022). Previous research has examined various settings, such as the workplace, as shown by studies conducted by (Alnufaie, 2022; Puebla et al., 2021). The majority of the studies in the realm of learning have been made inside a formal learning setting except four studies which were conducted in the informal contexts, as documented by the authors (Zhang and Pérez-Paredes, 2019; Ibáñez and Vermeulen, 2021; Li et al., 2023; Jeon, 2022).

In addition, the study was conducted in both formal and informal settings, as reported by Lestary (2020) and Loewen et al. (2019). Based on the analysis shown in Figure 2, it is notable that the use of mobile devices for learning purposes is essentially limited to the classroom environment. The research in this area primarily focuses on formal educational contexts, with a lack of studies exploring its efficacy beyond the limits of the classroom. Mobile learning can enhance learners’ abilities to engage in formal and informal contexts, encouraging more self-direction and responsibility in their learning endeavors.

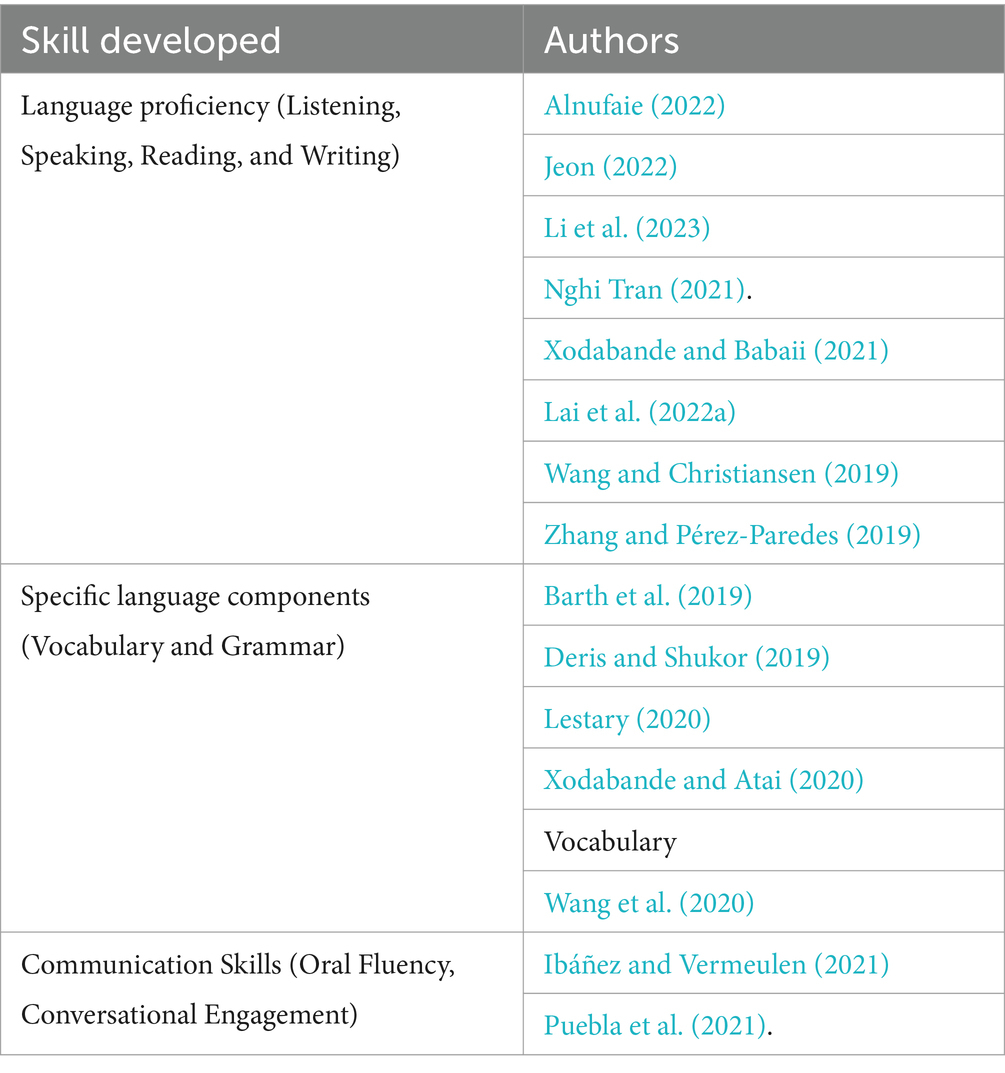

4.2 Skills developed

The skills developed from the reviewed articles explore innovative uses of mobile learning in language acquisition, especially in grammar, vocabulary, oral communication, and language skills like listening, reading, and writing. The analysis integrates six studies (Deris and Shukor, 2019; Xodabande and Atai, 2020; Lestary, 2020; Barth et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020; Xodabande et al., 2021) that highlight improvements and effectiveness in language acquisition. In addition, two recent studies (Puebla et al., 2021; Ibáñez and Vermeulen, 2021) illustrate the enhanced proficiency in learners’ oral communication abilities. Furthermore, eight studies (Zhang and Pérez-Paredes, 2019; Lai et al., 2022a; Alnufaie, 2022; Jeon, 2022; Li et al., 2023; Nghi Tran, 2021; Xodabande and Babaii, 2021; Wang and Christiansen, 2019) stated the development of language ability. It is essential to note that these research articles examined the implications of cultivating language ability using MALL in the context of acquiring self-directed language learning, and the pedagogical outcome of the reviewed articles explores the skill development that enriches the learners’ self-expression, as shown in Table 2. Yan and Singh (2023) state that self-directed language learning enhances communicative ability. Effectively implementing MALL involves use of practical language learning apps that foster self-directed learning and prioritize learners’ behavioral needs.

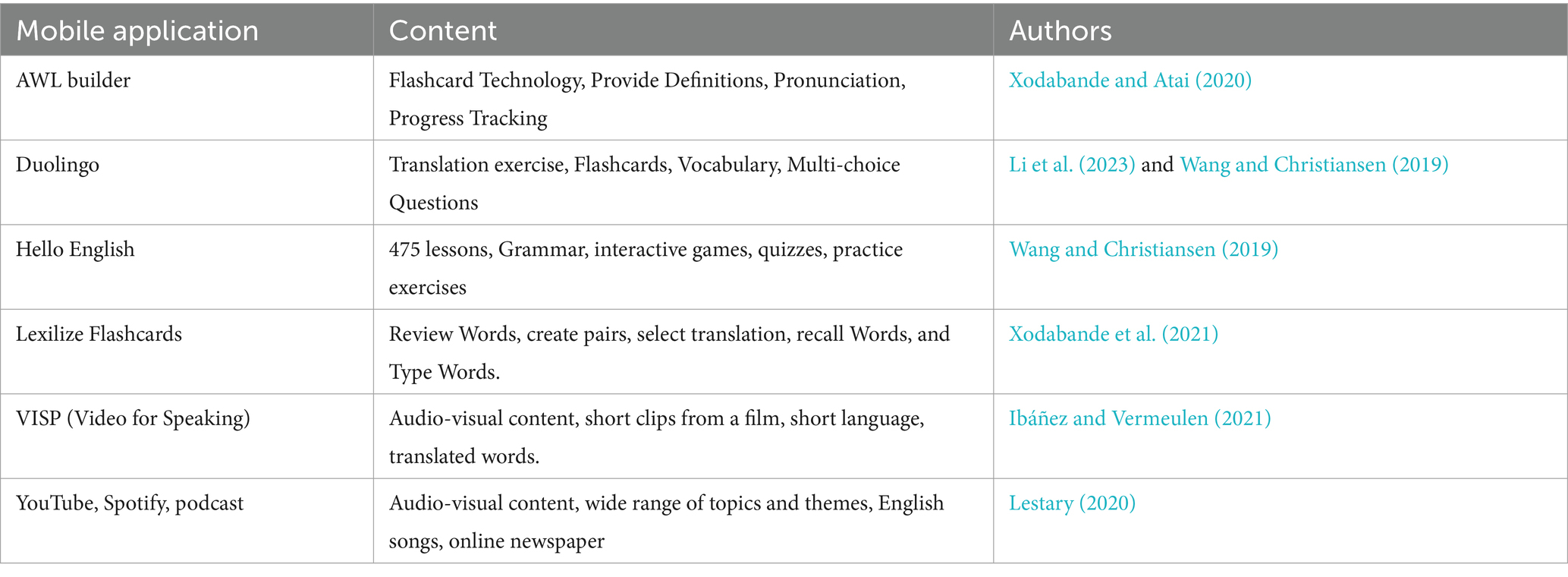

4.3 Mobile technologies

Mobile applications that enhance language learning are discussed in the reviewed articles. Various mobile platforms used for the teacher intervention are displayed in Table 3. Mobile technologies are increasingly acknowledged as crucial instruments for formal and informal education, which support the growth of linguistic competence and self-directed learning (Keengwe and Bhargava, 2013). The study noted that technologies utilized for language learning are beneficial to both the teachers and learners. Furthermore, the studies of Alnufaie (2022), Barth et al. (2019), Deris and Shukor (2019), Jeon (2022), Nghi Tran (2021), Puebla et al. (2021), Lai et al. (2022a), Zhang and Pérez-Paredes (2019), and Wang et al. (2020) did not specify any mobile application but indicates that MALL offers flexibility, convenience, and access to resources for the learners. Xodabande and Babaii (2021) explore the concept of Directed Motivational Currents (DMCs) and their effect on motivation and learning in self-directed learning. DMCs are recognized as powerful motivators that inspire individuals to pursue meaningful objectives consistently. This resource offers guidance on identifying and using DMCs in language learning. However, the effectiveness of mobile-assisted language learning relies on factors such as learners’ motivation, efficiency in using digital technology, and the development of language learning apps. The studies highlight that individuals can select appropriate learning materials, and the portability of mobile devices facilitates independent learning in short periods.

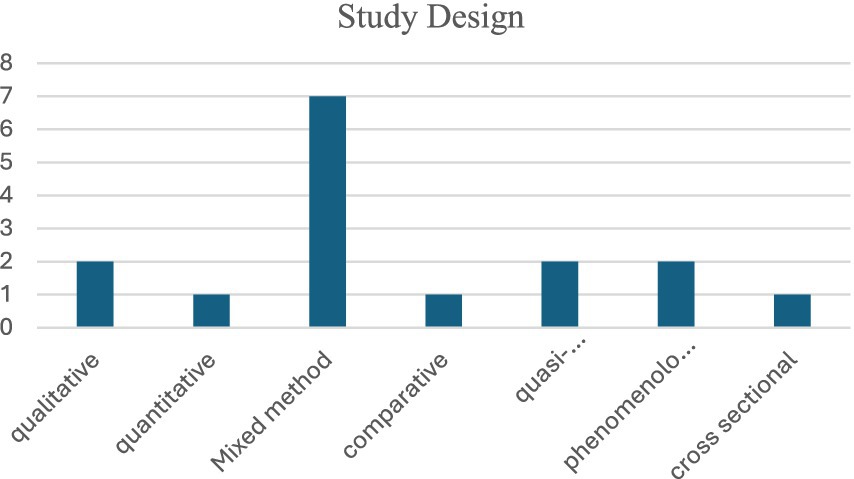

4.4 Study design

The Study design refers to the framework and approach utilized for collecting and analyze data on variables determined in a research problem. The review articles included a variety of study designs, as shown in Figure 3. Mixed methods designs were more prevalent than qualitative (Lestary, 2020; Wang and Christiansen, 2019), quantitative (Alnufaie, 2022), comparative techniques (Ibáñez and Vermeulen, 2021) quasi-experimental (Xodabande and Atai, 2020; Xodabande et al., 2021), Phenomenological (Deris and Shukor, 2019; Xodabande and Babaii, 2021) and cross-sectional survey (Lai et al., 2022a). Although mixed method (Puebla et al., 2021; Zhang and Pérez-Paredes, 2019; Jeon, 2022; Li et al., 2023; Nghi Tran, 2021; Barth et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020) studies aid to evaluate participants learning outcomes, it is essential to recognize that learning, particularly in the context of language acquisition, is influenced by various factors, with performance. The learning process and its outcome may be affected by elements such as learners’ background, level of engagement with the platform, desire for language learning, and familiarity with technology. Furthermore, the study design analyses the mobile language apps which influences learners’ motivation, autonomy, and self-regulated learning.

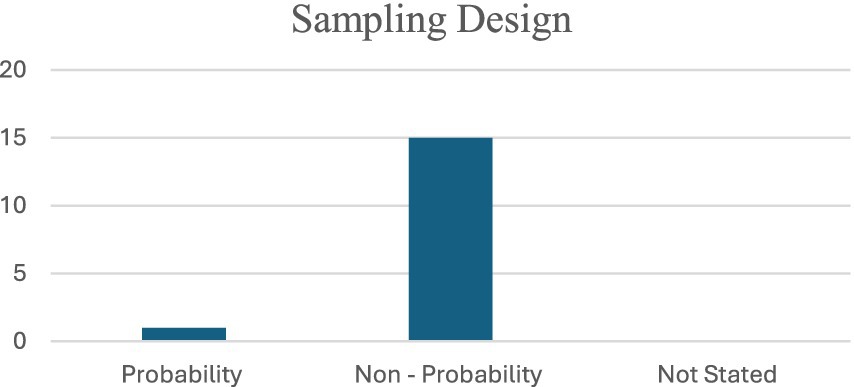

4.5 Sampling design

The sampling design of the data of the articles reviewed is presented in Figure 4. Nearly all the reviewed articles (n = 15) used non-probability sampling of which, majority of them utilized either convenience or purposive sampling. Zhang and Pérez-Paredes (2019) used stratified sampling in their study. Mobile applications facilitate self-directed language learning among learners with positive attitudes toward language acquisition, which impacts the results of effective learning (Lai et al., 2022a; Li et al., 2023). Some studies did not employ stratified or random sampling, so the effectiveness of MALL in language learning cannot be generalized. Further, stratified sampling provides complexity to categorizing data and makes evaluating the results more challenging than other probability sampling methods. Emphasizing the importance of conducting more studies using the statistical probability sampling method is essential.

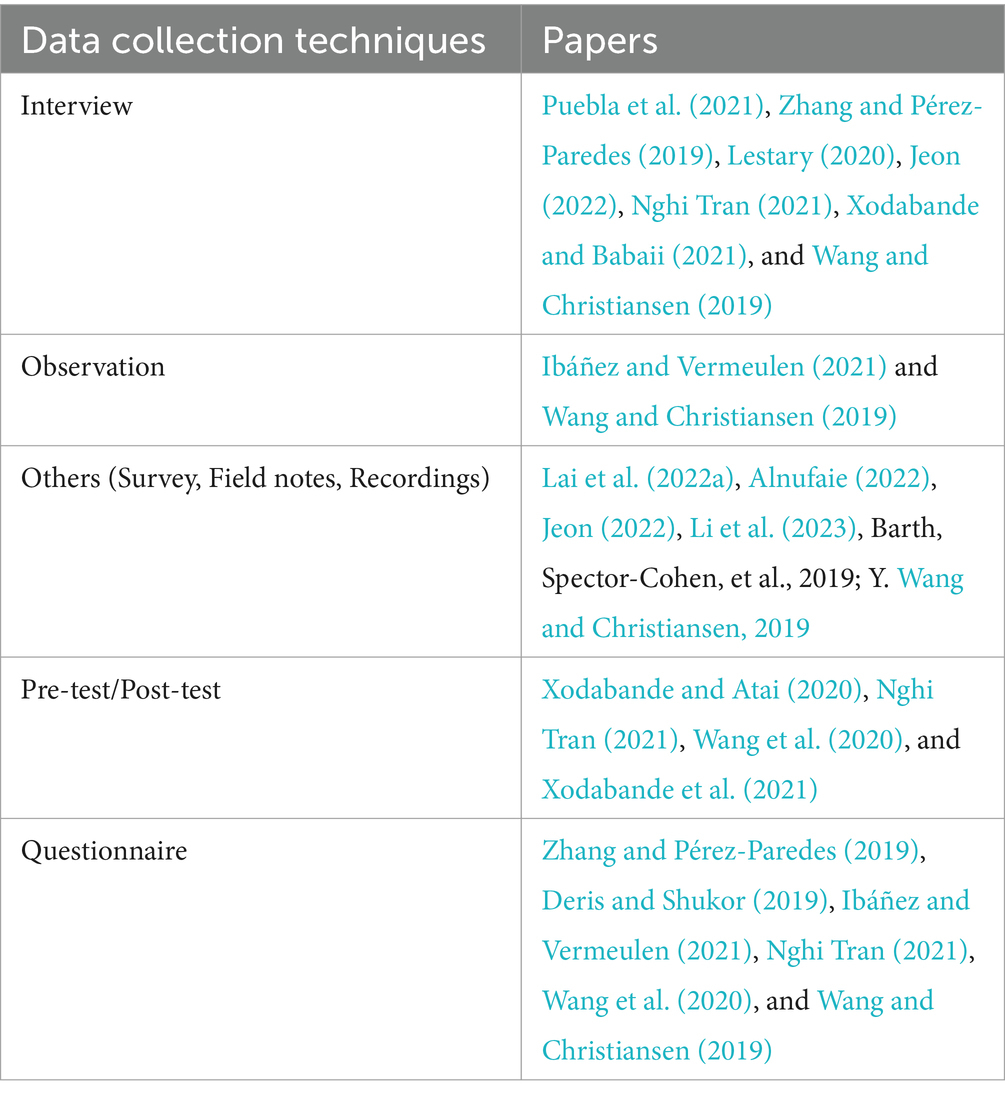

4.6 Data collection techniques

Data collection techniques of the studies analyzed the data by administering questionnaires (n = 1), pre-test and post-tests (n = 2), Interviews (n = 7), observation (n = 1), and others such as surveys, field notes, and recordings (n = 4), and all the data collections used in the study (Wang and Christiansen, 2019; Jeon, 2022; Ibáñez and Vermeulen, 2021; Nghi Tran, 2021; Wang et al., 2020; Xodabande and Babaii, 2021; Zhang and Pérez-Paredes, 2019), are shown in Table 4. The studies used questionnaires (n = 6) to collect quantitative data from the participants, focusing on using MALL as a self-directed learning resource. The questionnaires featured open and close-ended questions and Likert scale items. Moreover, Nghi Tran (2021) administered the questionnaires to collect learners’ backgrounds, practices, motivation, adoption of devices, and technological abilities. Xodabande and Atai (2020) employed pre-tests and post-tests to evaluate the efficacy of mobile apps for vocabulary acquisition in both short-term and long-term goals. The researcher also identifies the strengths and weaknesses of the learners in language learning by conducting pre-tests and post-tests. In addition, Wang et al. (2020) and Xodabande et al. (2021) in their studies stated to get an understanding of the mobile learning technique and measure the learners’ receptive knowledge. They also used semi-structured interviews to gather qualitative data in their works. Puebla et al. (2021) and Jeon (2022) analyzed the detailed understanding of the learner-centered approach. They also used mobile apps for language learning and fosters rapport among learners, facilitating the exchange of ideas, attitudes, and behaviors (Zhang and Pérez-Paredes, 2019; Lestary, 2020). Likewise, Xodabande and Babaii (2021) and Wang and Christiansen (2019) illustrates several aspects of learners’ language learning experience.

5 Discussion

The reviewed articles effectively demonstrated the acquisition of knowledge and skills through self-directed learning by utilizing MALL and evaluating a language approach to enhance the intellectual growth of the learners.

RQ1: How does MALL facilitate self-directed Learning for sustainable language learning in a pedagogical context?

The discussion discloses that the current study investigated the role of Mobile-Assisted Language Learning (MALL) in improving SDL within a pedagogical context. The results suggest that MALL supports sustainable language learning by enabling learners to progress in their language skills at their own pace using mobile technology. Additionally, teachers can promote self-directed learning, which promotes sustainable language learning. Learners’ SDL forms the basis for the development of pedagogical activities to create the most effective educational methods, implementing processes that effectively promote the development of autonomous learning competency and other essential 21st-century abilities such as creativity, communication, and critical thinking in adult learners, focusing on formal educational environments (Morris, 2019). Albedah (2019) examines the utilization of MALL by self-directed learners who were intrinsically motivated to engage in independent study. The availability and practicality of MALL through smartphone usage are vital factors influencing learners’ motivation, self-awareness, and self-confidence in the learning process. The students demonstrated the ability to observe and control their learning processes independently, develop goals to achieve, actively participate in the learning process, and enhance their language proficiency using MALL beyond the classroom (Wichadee, 2011).

The practical path of sustainable learning strengthens academic achievement among higher education learners. Using MALL may be an effective strategy for promoting self-directed learning for sustainable language acquisition due to its potential to augment learners’ motivation, interest, and engagement by satisfying their basic needs (Mortazavi et al., 2021). For example, the Academic Word List Builder (AWLB) application facilitates self-directed learning for sustainable language acquisition by enhancing accessibility and convenience through mobile devices. It empowers learners to engage with academic vocabulary at any time and in any location. In contrast to traditional materials, the application’s interactive environment significantly improves retention and fosters long-term vocabulary development. Furthermore, the application encourages autonomy, enabling students to cultivate self-management skills and achieve greater independence in their learning processes (Xodabande and Atai, 2020). Alnufaie (2022) examines the characteristics of Mobile-Assisted Language Learning and comprehensively analyzes the theoretical framework and literature about MALL applications. The main focus is to elucidate the advantages of employing these language-acquisition applications. Simanjuntak et al. (2022) examined the consumption of application-based learning, demonstrating its effectiveness in aiding the learners to communicate effectively. Using a mobile application enhances learners’ desire and proficiency in language acquisition, enticing them to participate actively in the educational endeavor.

The review suggests valuable insights into the effects of MALL on language learning for learners, with potential implications for academic success. Individuals of various age ranges utilize mobile devices. Based on the learners’ interests and digital literacy, it is evident that MALL is frequently used in higher education. The review also discusses the factors influencing learners’ language skills, motivation, cognitive capacities, and learning techniques. The key findings of the current review are stated below.

1. Both learners and teachers should actively engage with technologies and understand how they can be integrated into the learning and teaching process.

2. Support students in attaining their academic autonomy and preferred learning style while addressing pedagogical factors for educators.

3. Develop active and self-directed action by implementing a collaborative approach that combines logical reasoning skills with innovation and information technology (Botero et al., 2018).

The impact of incorporating mobile learning into educational sustainability has been observed to have a substantial influence on the behavior of the learners using this technology. The earlier-mentioned influence is determined to be entirely mediated by the learners’ desire to engage actively in mobile learning. The learners will develop a positive attitude toward M-learning and consequently demonstrate a tendency to utilize their language proficiency skills once they recognize the effectiveness of mobile devices, their flexibility in learning and effectiveness for educational objectives, technical and organizational support, and the influence of significant individuals. In sustainable learning in the evolving world, learners must be exposed to problem-solving scenarios as part of their formal education. SDL using mobile applications gives users the skills and information to navigate problems and significant life changes, supporting sustainable growth. This systematic review indicates that mobile-assisted language learning has a beneficial influence on learners’ self-efficacy and facilitates their self-directed language learning endeavors. Mobile applications provide learners with the opportunity to enhance language acquisition. The acquisition of language skills will lead to an enhancement in the learners’ overall educational experience.

RQ2: Does MALL promote motivation, engagement, and autonomy of the language learners?

Self-Directed Learning (SDL) fosters adaptability, autonomy, and personalized learning experiences, allowing the learners to lead their educational journey. SDL enables individuals to build lifelong learning skills, pursue personal interests, and set autonomous learning objectives. This approach subsequently fosters more profound and considerable learner involvement with the learning process. According to Puebla et al. (2021), motivation, engagement, and autonomy significantly influence the use of MALL among older adults. These concepts shape attitudes, practices, and perceptions of language learning apps and digital technology, offering valuable insights into the learning process. These characteristics enable the educators and the language curriculum designers to develop mobile English learning tools that are successful, interesting, relevant, and beneficial for the learners. Furthermore, using MALL fosters positive adoption, efficiency, guidance, and self-confidence for sustainable learning (Deris and Shukor, 2019; Zhang and Pérez-Paredes, 2019; Lai et al., 2022a).

Integrating mobile applications into language learning facilitates the learner’s interaction and fosters language acquisition quickly (Xodabande and Atai, 2020; Lestary, 2020; Jeon, 2022; Alnufaie, 2022). Furthermore, it has been observed in several studies (Li et al., 2023; Ibáñez and Vermeulen, 2021; Wang et al., 2020; Barth et al., 2019; Xodabande and Babaii, 2021; Wang and Christiansen, 2019; Xodabande et al., 2021; Nghi Tran, 2021) that learners who had well defined and explicit learning objectives indicated higher levels of motivation and achieved superior performance. Additionally, students had more meaningful and engaged learning experiences when they could locate pertinent materials from a single mobile-assisted learning application. The significance of learner autonomy in overseeing their education, including resource exploration and time management, was also highlighted in the reviewed articles.

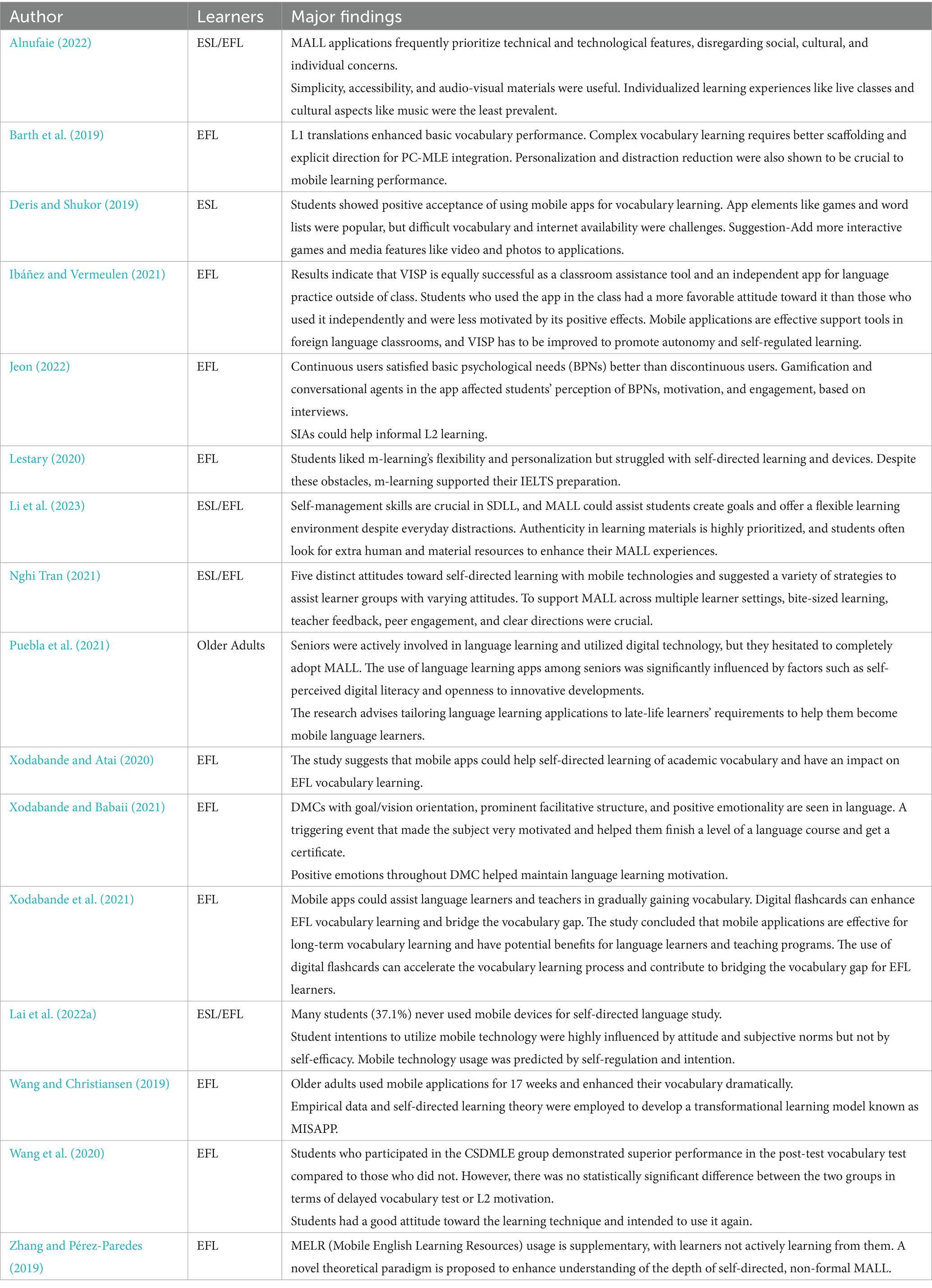

The systematic review highlights the potential of MALL to improve self-directed language learning and competence across various areas, such as listening comprehension, speaking, writing, and vocabulary acquisition. The findings of the reviewed articles exhibited positive outcomes regarding language ability. They emphasize the long-term benefits of using MALL for language acquisition, as shown in Table 5.

MALL is implemented for both ESL and EFL to develop their proficiency in language. The studies proved that the integration of MALL into the curricula to enhance sustainable language learning was successful. Since no research resulted in negative effect, the educators, researchers and learners may consider using the MALL.

5.1 Findings of the study

Mobile-assisted language learning (MALL) significantly enhances self-directed language learning by providing the learners with flexible access to educational resources. Integrating smartphones and tablets into teaching facilitates participation in both self-paced and collaborative activities, resulting in personalized academic experiences. The findings indicate that mobile application is an important instructional tool for improving language proficiency. It also supports the advancement of English language capabilities and increases learners’ motivation for active involvement in the learning process. Additionally, MALL promotes cognitive development, encourages participation in the formal and informal educational environments, enhances learner autonomy, and fosters confidence in learning. Numerous studies have been conducted on Mobile-Assisted Language Learning (MALL), for instance, Xodabande Ismail has published five articles between 2022 and 2023, indicating his substantial contribution to contemporary academic research in this field. Furthermore, researchers such as Chen Yan and Hwang Wu-Yin have consistently made significant contributions to the advancement of MALL.

5.2 Limitations and future research

This study was limited to the data obtained from Scopus and Web of Science from the year 2019–2023 without considering any additional sources such as review articles and themes not related to MALL or SDL. The investigation concentrated on the constraints of self-directed learning, long-term language acquisition, and the incorporation of MALL in developing language proficiency. The current study investigates the impact of MALL on SDL for long-term language acquisition for language proficiency. Many studies have investigated the potential of MALL and self-directed learning to improve language abilities, mainly proficiency in speaking. However, it is crucial to note that these studies have primarily focused on language learning, with little attention paid to improving reading and writing skills through mobile devices.

6 Conclusion

Mobile-assisted language learning can support long-term and self-directed language acquisition. This research provides pedagogical implications and instructional strategies for successfully incorporating mobile applications into language education. MALL has significant potential for promoting lifelong learning. Further research is needed to fully appreciate and successfully address the associated problems and opportunities inherent in MALL. SDL can help learners organize, supervise, and evaluate their learning aspirations and results. As a result, educators have a crucial responsibility to assist and guide learners to acquire SDL skills for sustainable learning. This observation highlights the capacity of contemporary technology and online resources to provide learners with a wide range of learning materials and opportunities, enhancing their problem-solving situations as an essential component of their formal education.

Author contributions

SS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SG: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Albedah, F. (2019). The use of mobile devices for self-directed learning outside the classroom among EFL university students in Saudi Arabia. International Conference on Educational Technologies. Available at: Available at: https://researchdirect.westernsydney.edu.au/islandora/object/uws%3A56687.

Almudibry, K. (2022). A Meta-analysis of the literature on Mobile assisted language learning in response to COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia. World J. Engl. Lang. 12:106. doi: 10.5430/wjel.v12n8p106

Alnufaie, M. R. (2022). Mobile-assisted language learning applications: features and characteristics from users' perspectives. Stud. Self Access Learn. J. 13, 312–331. doi: 10.37237/130302

Altynbekova, G., and Zhussupova, R. (2020). Mobile application Fluentu for public speaking skills development. SHS Web of Conferences 88, 02208. doi: 10.1051/shsconf/20208802008

Al-Shehri, S. (2011). Context in our pockets: Mobile phones and social networking as tools of contextualising language learning.

Ameri, M. (2020). The use of Mobile apps in learning English language. Budapest Int. Res. Critics Linguist. Educ. J. 3, 1363–1370. doi: 10.33258/birle.v3i3.1186

Barth, I., Spector-Cohen, E., Sitman, R., Jiang, G., Fang, L., and Xu, Y. (2019). Beyond small chunks. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. Teach. 9, 79–97. doi: 10.4018/ijcallt.2019040105

Beatty, K. (2013). Teaching and Researching: Computer-assisted language learning. Abingdon: Routledge.

Ben-Eliyahu, A. (2021). Sustainable learning in education. Sustain. For. 13:4250. doi: 10.3390/su13084250

Botero, G. G., Questier, F., and Zhu, C. (2018). Self-directed language learning in a mobile-assisted, out-of-class context: do students walk the talk? Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 32, 71–97. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2018.1485707

Cavus, N., and Ibrahim, D. (2009). M-learning: an experiment in using SMS to support learning new English language words. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 40, 78–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2007.00801.x

Chen, C., and Hsu, S. (2008). Personalized intelligent mobile learning system for supporting effective English learning. Educ. Technol. Soc. 11, 153–180.

Chen, C., and Li, Y. (2010). Personalised context-aware ubiquitous learning system for supporting effective English vocabulary learning. Interact. Learn. Environ. 18, 341–364. doi: 10.1080/10494820802602329

Chinnery, G. M. (2006). Going to the MALL: Mobile assisted language learning. Lang. Learn. Technol. 10, 9–16.

De Figueiredo, A. D. (2005). Centro de Informática e de Sistemas, Departamento de Engenharia Informática, and Universidade de Coimbra. Learning Contexts: a Blueprint for Research. In: Interactive educational multimedia, pp. 127–139. Available at: http://www.ub.es/multimedia/iem.

Deris, F. D., and Shukor, N. S. A. (2019). Vocabulary learning through Mobile apps: a phenomenological inquiry of student acceptance and desired apps features. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 13:129. doi: 10.3991/ijim.v13i07.10845

Dou, K., Halim, H. A., and Saad, M. R. M. (2024). A bibliometric study of Mobile-assisted language learning from 2013 to 2023: research themes and trends. J. Curric. Teach. 13:431. doi: 10.5430/jct.v13n5p431

Figueiredo, S. (2023). The efficiency of tailored Systems for Language Education: an app based on scientific evidence and for student-centered approach. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 583–592. doi: 10.12973/eu-jer.12.2.583

Hsu, K., and Liu, G. (2021). A systematic review of mobile-assisted oral communication development from selected papers published between 2010 and 2019. Interact. Learn. Environ. 31, 3851–3867. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2021.1943690

Ibáñez, A. M., and Vermeulen, A. (2021). A comparative analysis of a Mobile app to Practise Oral skills: in classroom or self-directed use? J. Univ. Comput. Sci. 27, 472–484. doi: 10.3897/jucs.67032

Jeon, J. H. (2022). Exploring a self-directed interactive app for informal EFL learning: a self-determination theory perspective. Educ. Inf. Technol. 27, 5767–5787. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10839-y

Jeong, K. (2022). Facilitating sustainable self-directed learning experiences with the use of Mobile-assisted language learning. Sustain. For. 14:2894. doi: 10.3390/su14052894

Keengwe, J., and Bhargava, M. (2013). Mobile learning and integration of mobile technologies in education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 19, 737–746. doi: 10.1007/s10639-013-9250-3

Kim, H. Y., and Kwon, Y. H. (2012). Exploring smartphone applications for effective Mobile-assisted language learning. Multimed. Assist. Lang. Learn. 15, 31–57. doi: 10.15702/mall.2012.15.1.31

Klopfer, E., Squire, K., and Jenkins, H. A. (2003). Environmental detectives: PDAs as a window into a virtual simulated world. IEEE International Workshop on Wireless and Mobile Technologies in Education.

Lai, C. (2015). Modeling teachers’ influence on learners’ self-directed use of technology for language learning outside the classroom. Comput. Educ. 82, 74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2014.11.005

Lai, Y., Saab, N., and Admiraal, W. (2022a). University students' use of mobile technology in self-directed language learning: using the integrative model of behavior prediction. Comput. Educ. 179:104413. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104413

Lai, Y., Saab, N., and Admiraal, W. (2022b). Learning strategies in self-directed language learning using Mobile Technology in Higher Education: a systematic scoping review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 27, 7749–7780. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-10945-5

Lai, C., and Zheng, D. (2017). Self-directed use of mobile devices for language learning beyond the classroom. ReCALL 30, 299–318. doi: 10.1017/s0958344017000258

Latypova, L., Polyakova, O. V., and Sungatullina, D. D. (2018). “Mobile applications for English learning performance upgrade” in Lecture notes in computer science (Berlin: Springer), 403–411.

Lestary, S. (2020). Perceptions and experiences of Mobile-assisted language learning for IELTS preparation: a case study of Indonesian learners. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 10, 67–73. doi: 10.18178/ijiet.2020.10.1.1341

Li, Z., Bonk, C. J., and Chen, Z. (2023). Supporting learners’ self-management for self-directed language learning: a study within Duolingo. Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 21, 381–402. doi: 10.1108/itse-05-2023-0093

Liu, B., Wang, D., Wu, Y., Gui, W., and Luo, H. (2023). Effects of self-directed learning behaviors on creative performance in design education context. Think. Skills Creat. 49:101347. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2023.101347

Lim Razali, A. B., and Samad, A. A. (2018). Self-directed Learning Readiness (SDLR) Among Foundation Students from High and Low Proficiency Levels to Leaen English Language. Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction.

Loewen, S., Crowther, D., Isbell, D. R., Kim, K. M., Maloney, J., Miller, Z. F., et al. (2019). Mobile-assisted language learning: a Duolingo case study. ReCALL 31, 293–311. doi: 10.1017/s0958344019000065

Loyens, S. M. M., Magda, J., and Rikers, R. M. J. P. (2008). Self-directed learning in problem-based learning and its relationships with self-regulated learning. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 20, 411–427. doi: 10.1007/s10648-008-9082-7

MacFarlane, A., Russell-Rose, T., and Shokraneh, F. (2022). Search strategy formulation for systematic reviews: issues, challenges, and opportunities. Intell. Syst. Appl. 15:200091. doi: 10.1016/j.iswa.2022.200091

Mittal, A. (2024). The role of AI in revolutionizing language learning: how SpeakX is leading the way. South Asia’s Leading Multimedia News Agency. Available at: https://www.aninews.in/news/business/the-role-of-ai-in-revolutionizing-language-learning-how-speakx-is-leading-the-way20240806164735/.

Morris, T. H. (2019). Self-directed learning: a fundamental competence in a rapidly changing world. Int. Rev. Educ. 65, 633–653. doi: 10.1007/s11159-019-09793-2

Mortazavi, M., Nasution, M. K. M., Abdolahzadeh, F., Behroozi, M., and Davarpanah, A. (2021). Sustainable learning environment by Mobile-assisted language learning methods on the improvement of productive and receptive foreign language skills: a comparative study for Asian universities. Sustain. For. 13:6328. doi: 10.3390/su13116328

Nghi Tran, T. L. (2021). Perspectives and attitudes towards self-directed MALL and strategies to facilitate learning for different learner groups. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. Electron. J., 41–59.

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

Puebla, C., Fievet, T., Tsopanidi, M., and Clahsen, H. (2021). Mobile-assisted language learning in older adults: chances and challenges. ReCALL 34, 169–184. doi: 10.1017/s0958344021000276

Shortt, M., Tilak, S., Kuznetcova, I., Martens, B., and Akinkuolie, B. (2021). Gamification in mobile-assisted language learning: a systematic review of Duolingo literature from public release of 2012 to early 2020. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 36, 517–554. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2021.1933540

Simanjuntak, R. F., Prawati, A., and Masyhur, M. (2022). The effect of hello English application on speaking ability. Edukatif 4, 7415–7425. doi: 10.31004/edukatif.v4i6.4100

Sönmez, E. E., and Çakır, H. (2020). Effect of web 2.0 technologies on academic performance: a meta-analysis study. Int. J. Technol. Educ. Sci. 5, 108–127. doi: 10.46328/ijtes.161

Stockwell, G. (2022). Mobile assisted language learning: concepts, contexts and challenges. London: Cambridge University Press.

Sulaiman, M. M. (2019). Education for sustainable development. Int. J. Creative Res. Thoughts 7, 813–815.

Tram, N. H. M., Nguyen, T. T., and Tran, C. D. (2024). ChatGPT as a tool for self-learning English among EFL learners: a multi-methods study. System 127:103528. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2024.103528

Wang, Y., and Christiansen, M. S. (2019). An investigation of Chinese older adults' self-directed English learning experience using mobile apps. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. Teach. 9, 51–71. doi: 10.4018/ijcallt.2019100104

Wang, Z., Hwang, G., Zhang, Y., and Ma, Y. (2020). A contribution-oriented self-directed mobile learning ecology approach to improving EFL students' vocabulary retention and second language motivation. Educ. Technol. Soc. 23, 16–29.

Wichadee, S. (2011). Developing the self-directed learning instructional model to enhance English reading ability and self-directed learning of undergraduate students. J. Coll. Teach. Learn. 8:43. doi: 10.19030/tlc.v8i12.6620

Xodabande, I., and Atai, M. R. (2020). Using mobile applications for self-directed learning of academic vocabulary among university students. Open Learn. 37, 330–347. doi: 10.1080/02680513.2020.1847061

Xodabande, I., and Babaii, E. (2021). Directed motivational currents (DMCs) in self-directed language learning: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. J. Lang. Educ. 7, 201–212. doi: 10.17323/jle.2021.12856

Xodabande, I., Pourhassan, A., and Valizadeh, M. (2021). Self-directed learning of core vocabulary in English by EFL learners: comparing the outcomes from paper and mobile application flashcards. J. Comput. Educ. 9, 93–111. doi: 10.1007/s40692-021-00197-6

Yan, Y., and Singh, M. K. M. (2023). On the educational theory and application of Mobile-assisted language learning and independent learning in college English teaching. Eğitim Yönetimi 29, 137–151. doi: 10.52152/kuey.v29i3.675

Yousif, (2022). Educational context: the factor for a successful change. Journal of Education & Social Policy, 9. doi: 10.30845/jesp.v9n1p6

Keywords: self-directed learning, MALL, mobile apps, sustainable learning, language learning

Citation: Shalini Roy S and Gandhimathi SNS (2025) Self-directed learning for optimizing sustainable language learning via mobile assisted language learning: a systematic review. Front. Educ. 9:1463721. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1463721

Edited by:

Jose Belda-Medina, University of Alicante, SpainReviewed by:

Nashwa Ismail, University of Liverpool, United KingdomMohammad Najib Jaffar, Islamic Science University of Malaysia, Malaysia

Copyright © 2025 Shalini Roy and Gandhimathi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: S. N. S. Gandhimathi, Z2FuZGhpbWF0aGkuc25zQHZpdC5hYy5pbg==

S. Shalini Roy

S. Shalini Roy S. N. S. Gandhimathi

S. N. S. Gandhimathi