- Department of Education and Special Education, Faculty of Education, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

Introduction: Adolescent autistic girls in mainstream schools experience more loneliness and exclusion than their peers. Swedish schools have a long tradition of working towards inclusion but, despite this commitment, these girls are at higher risk of absenteeism and failing to achieve educational objectives. Bearing this in mind, it is important to understand how autistic girls navigate their everyday school life from a first-hand perspective and develop a broader understanding of what shapes their opportunities for and barriers to participation.

Methods: This qualitative study draws on multiple semi-structured interviews with 11 autistic girls, aged 13–15, exploring how they navigate having an autism diagnosis within a Swedish secondary school context.

Results: While on a personal level the diagnosis itself was mostly perceived as positive, the girls expressed ambivalence about making sense of it in the school context. The girls expressed awareness of the perceptions and understanding of autism in their school setting, and their consequences in terms of both support and exclusion and stigmatisation. The sense of being perceived by others as different, accompanied by a desire to belong and an awareness of stigma, seemed to have a strong impact on how they navigated everyday school life. This created field of tension between the social context of school, its values and norms, and the girls’ personal experiences and views about autism.

Discussion: The girls’ accounts illustrate the complex reality of their school lives post diagnosis. Valuable implications for practice include the need to work towards a discourse in schools in which differences are seen as natural, and guidance post diagnosis to build the girls’ awareness and understanding and enable them to develop strategies for successfully navigating school.

1 Introduction

For a long time, autism was perceived predominantly as a male disorder but today the gender bias in autism diagnosis is widely acknowledged. This has resulted in the development of diagnostic criteria and screening tools to better identify autistic females1 and decrease the likelihood of them being missed, misdiagnosed, or diagnosed later in life (Kopp and Gillberg, 1992, 2011; Munroe and Dunleavy, 2023). The consequences of non-diagnosis or unrecognised autism-related difficulties include poor mental health, loneliness, and unnecessary distress (Carpenter et al., 2019; O’Connor et al., 2024). Early identification of autism has been associated with increased wellbeing, timely support and intervention, acceptance by the community, and a positive perception of oneself (Bargiela et al., 2016). The long and complicated path by which females often receive a diagnosis not only delays the provision of appropriate support but has also been identified as a hindrance to developing their own understanding of their own challenges, self-awareness, and sense of belonging (Bargiela et al., 2016; Cridland et al., 2014). For girls, a timely autism diagnosis has been identified as essential to preventing the challenges they experience escalating (Duvekot et al., 2017), and to avoiding mental ill health and loneliness during adolescence which can have long-lasting adverse effects in adulthood (Schiltz et al., 2024).

In recent years the proportion of females, both children and adults, who receive an autism diagnosis has escalated. The reasons for this are not fully understood: it may partly be a by-product of changes in clinical practice (Arvidsson et al., 2018), and partly that more attention is being paid to underdiagnosis among women (Gould, 2017). In any case, the trend is true for Sweden. Kopp and Gillberg (1992) were relatively early to draw attention to the importance of girls in Sweden being diagnosed as a prerequisite for receiving appropriate guidance and support, promoting their wellbeing and a better quality of life. The increase in diagnosis is confirmed by a report drawing on health care data from the Stockholm region where the proportion of autistic girls quadrupled between 2011 and 2020 (Jablonska et al., 2022). While more girls are being diagnosed than a decade ago, debates and research in the Nordic countries (Kopp et al., 2023; Posserud et al., 2021), as elsewhere (Loomes et al., 2017; Young et al., 2018), continue to be largely dominated by diagnostic concerns (Pellicano and Houting, 2022) rather than delving into what happens post diagnosis. McLinden and Sedgewick (2023) noted that a diagnosis does not necessary result in positive change for girls, as is often argued. They interviewed professionals in health care and education who are involved in the diagnosis process in the UK and found that that, despite increased knowledge about autistic girls, this has not necessarily permeated into support and understanding post diagnosis which still seems dependent on the knowledge and attitudes of the particular professionals the girls’ encounter.

In recent years, the lived experiences of autistic students has been increasingly recognised (compare Humphrey and Lewis, 2008; Mogensen and Mason, 2015; Carpenter et al., 2019), forefronting a more personal understanding of autism and its impact on people’s lives (Leveto, 2018). This has partly been driven by the adoption of the General Comment No. 4 (Taneja-Johansson, 2023) which clearly articulates the human right to inclusive education as stipulated in the UNCRPD, and partly to the growing neurodiversity movement (O’Dell et al., 2016; Pellicano and Houting, 2022). In a recent scoping review examining the empirical research that draws on first-person experiences of schooling among students with autism and ADHD between 2000 and 2021, Taneja-Johansson (2023) concluded that the existing research largely represents the voices of adolescent males. The dominance of the male voice in research about the lived experience of autism across the life span has also been noted by DePape and Lindsay (2016).

However, there has been a recent increase in studies focusing on the lived experiences of autistic women and girls (Milner et al., 2019; Mo et al., 2022; Myles et al., 2019; Rainsberry, 2017; Tierney et al., 2016; Tomlinson et al., 2022; Zakai-Mashiach, 2023). These often adopt a phenomenological approach in which girls’ personal experiences are foregrounded with the school context serving mainly as a background. The focus has thus largely been on how they experience school rather than on how the girls themselves navigate having a diagnosis within school, a challenging context in which they spend a significant part of their lives as children and young people.

1.1 Understanding the diagnosis in a social context

Making sense of and navigating autism in social spaces is an even more important question when it comes to adolescence. Adolescence is a period during which young people develop self-understanding and explore their identity as they start to establish a sense of who they are and where they fit into the world. Social influence from peers and the pressure to conform to norms are heightened (Han et al., 2022; Kroger et al., 2010). At this stage in life, being seen as ‘different’ from one’s peers have been found to be a significant concern among autistic adolescents (Humphrey and Lewis, 2008; Myles et al., 2019; Tierney et al., 2016; Tomlinson et al., 2020). During this turbulent stage in life, negotiating having a diagnosis while developing self-understanding and identity can increase their vulnerability. A longitudinal cohort study into the health of young people in Sweden found that groups who are considered vulnerable experience higher levels of loneliness and psychosomatic problems during adolescence than others (Grigorian et al., 2024). For children with a neurodevelopmental diagnosis such as autism, vulnerability and the risk of stigma becomes even more evident, and this is a group that experiences more loneliness and exclusion than their peers without a diagnosis (Kwan et al., 2020).

The significant role of the social context in shaping how they perceive their autism diagnosis is a central theme in previous studies of autistic adolescents. Jones et al. (2015) noted that a key factor shaping their beliefs and thoughts about their diagnosis was the interaction between themselves and the social context that they were part of—that is, how their family, friends, and other individuals viewed and understood autism. Similarly, Mesa and Hamilton’s (2022) study of adolescents, parents, and teachers identified that the extent to which “autism” was integrated into young people’s developing identities was mediated by the responses and interactions they experienced in their social surroundings. A more complex picture is put forward by Mogensen and Mason (2015): in their study, adolescents did not perceive their diagnosis as either positive or negative. Rather, they constructed their self-understanding on the basis of their own knowledge about their diagnosis and how the surrounding environment perceived, or misperceived, autism.

Studies conducted within school contexts show that autistic adolescents tend to perceive their “difference” negatively (Cridland et al., 2014; Humphrey and Lewis, 2008; Tomlinson et al., 2022). Many adolescents, even those who construct their diagnosis positively, are keen to keep it private (Mesa and Hamilton, 2022). The dilemma of disclosure is a well-known theme in the broader research on autism. In a qualitative study about making sense of having an autism diagnosis, autistic adults considered the diagnosis itself to be value neutral but identified that misconceptions of autism in their social context create stigma and labels in a negative sense (Botha et al., 2022). Autistic individuals are deeply aware of how they may be stigmatised by others upon disclosure, as has been shown in a systematic review of experiences of stigma and coping strategies by Han et al. (2022). For the individual, the process of making the disclosure decision is complex, balancing benefits against concerns about others’ understanding of autism (Botha et al., 2022; Edwards et al., 2024; White et al., 2020; Zakai-Mashiach, 2023). While disclosing the diagnosis is associated with repercussions such as negative stereotyping and being treated differently, not disclosing it can also have negative effects such as a lack of understanding and support in the environment.

Autism, which is characterised by difficulties in communication, interaction, repetitive behaviour, and sensory skills (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), manifests differently in boys and girls. Girls tend to show a more internal presentation and place great value on relationships, driven by social motivation towards friendship which in turn leads to a greater tendency to mask their difficulties (Cridland et al., 2014; Munroe and Dunleavy, 2023; Tomlinson et al., 2020). A gender-related study about social behaviours in school found that the autistic girls were more likely than boys to mask their difficulties and strive to be part of a social group (Dean et al., 2017). Girls display an awareness and sensitivity to social expectations, leading them to copy and camouflage in order to fit in, although they have difficulties in both establishing and maintaining friendships (Goodall and Mackenzie, 2019; Ryan et al., 2021; Sedgewick et al., 2018). Findings from several studies note that adolescent girls feel uneasy with their diagnosis and strive to be “like everyone else” in order to gain acceptance, resulting in feelings of anxiety and exclusion (Bargiela et al., 2016; Cridland et al., 2014; Goodall and Mackenzie, 2019; Myles et al., 2019; Rainsberry, 2017; Tierney et al., 2016; Tomlinson et al., 2020).

1.2 Rationale for the present research

The sampling bias in autism research, with knowledge dominated by evidence about male autism, is frequently raised as a problem (Gould, 2017; Taneja-Johansson, 2023). Recent years have seen an increase in qualitative studies which draw on the voices of adolescent autistic girls (O’Connor et al., 2024). This research provides valuable insights but tends to rely on a phenomenological approach, limiting the focus to the lived experiences of autistic girls in school and everyday life. However, in line with O’Connor et al. (2024), we argue that autistic adolescent girls’ school experiences cannot be understood independent of the school context within which they occur. In this article, we adopt a socio-cultural theoretical perspective in which the given context, in this case mainstream school in Sweden, is considered central to a person’s development and to shaping and reshaping the individual’s notions and beliefs about the world and the sense of self, through interaction (Conn, 2014; Nasir and Hand, 2006). The central issues in this study relate to how autism is viewed and who perceives it as problematic or different, and in what ways it affects girls’ own experiences of autism and their strategies for coping with daily school life. The aim is to develop a deeper understanding of how adolescent girls navigate having an autism diagnosis in Swedish secondary school context and their opportunities for participation. Our ambition is to question the often taken for granted conclusions in research on autistic girls, that may reflect the schooling and cultural context of a particular country rather than girls’ experiences more universally.

Previous studies of autistic girls have mainly been conducted with students attending schools in the UK. In this study we extend the geographical realm of research to Swedish schools, where support is provided solely on the basis of need rather than diagnosis, in accordance with the Swedish School Act (SFS, 2010, p. 801). It is particularly interesting to explore how adolescent girls navigate their autism diagnosis within such a setting. From a first-hand perspective, understanding what shapes opportunities for and barriers to participation is relevant because this group is at greater risk than others of absenteeism and not qualifying for upper secondary school (Anderson, 2020; Stark et al., 2021). The following research question will be in focus:

How do adolescent girls experience having an autism diagnosis within a school context and how does it shape the ways they navigate their school life?

The study focuses on the narratives of 11 autistic girls pursuing their education in a mainstream secondary school setting in Sweden and how their experiences within this specific context shape the way they navigate their school life and opportunities for participation. By exploring autistic girls’ narratives as to how they conceptualise autism within a mainstream school context, and the impact this has on how they navigate their everyday school life and relationships, we hope to develop a broader and more nuanced understanding of how autism can be experienced and contextualised from a first-hand perspective. Aligning with a neurodiversity perspective on autism, in which cognitive difference is perceived as part of human diversity and as such value-neutral (Kapp et al., 2013; Stenning and Rosqvist, 2021), we seek to gain deeper insight into autistic girls in their daily school life as understood and perceived by them, which is of interest for both further research and educational practice. In order to understand the girls’ experiences from a socio-cultural perspective in which not just the complexity of having an autism diagnosis is considered important but this complexity is situated in a cultural context (Conn, 2014; Leveto, 2018), it is important to describe the Swedish school context from which these narratives derive.

1.3 The Swedish context

In Sweden, the Education Act of 2010 (SFS, 2010, p. 801) stipulates that all autistic children with no intellectual disability are to be educated in mainstream settings (van Kessel et al., 2019). Children attend school at the age of 7 and the school system is divided into three phases: primary school (years 1–3), middle school (years 4–6) and secondary school (years 7–9). The Swedish school system has a long tradition of inclusive education, guided by the vision of “one school for all,” and meeting the needs of all students within general education has been a clearly stated goal of Swedish Education policy since the 1990s (Göransson et al., 2011). Individual needs drive the provision of accommodations in school and a disability diagnosis is not required to be eligible for support (SFS, 2010, p. 801). The support system has two levels: firstly, accommodations and adjustments for minor support needs which are often provided within the classroom; and secondly more extensive and long-term special support (Skolverket, 2014).

However, there is increasing evidence to suggest that schools in Sweden are not always meeting the educational needs of autistic students (Leifler et al., 2022; Leifler et al., 2021). Recent studies indicate that more than half of the autistic students may not achieve passing grades in core subjects (Anderson, 2020). In a longitudinal register-based study, autistic students were less likely than their peers to qualify for upper secondary school, and autistic girls were at greater risk of not qualifying than autistic boys (Stark et al., 2021). Additionally, absenteeism has been found to be higher among students with autism than among non-autistic students (Nordin et al., 2023), with girls accounting for the highest levels of absenteeism and appearing to be the most vulnerable (Anderson, 2020). In Sweden, secondary school represents the last 3 years of compulsory education (year 7–9) with students attending between the ages of 13–15 (SFS, 2010, p. 801). The transition from middle to secondary school places increased demands on students to demonstrate personal responsibility and independence, and the curriculum strongly emphasises communicative abilities and individual autonomy (Lgr22, 2022).

2 Methods

The current qualitative study aims to examine how adolescent girls experience having an autism diagnosis within a school context and how it shapes the ways to navigate their school life. Drawing on a socio-cultural theoretical perspective where the interactions in a given context are viewed as ongoing and shifting (Conn, 2014; Nasir and Hand, 2006), the study is conducted in Swedish Secondary school and focuses on narratives of 11 adolescent autistic girls.

2.1 Participants

The research data include 22 semi-structured interviews with 11 adolescent autistic girls, age 13–15, attending secondary schools. After obtaining approval from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority,2 contact was established with potential participants through online communities about autism and special education for parents and educators, and through the first author’s professional network. To facilitate in-person meetings with the girls, the study was limited to the area in and around a large city in western Sweden.

Parents who expressed interest in the study were contacted by the first author by text message or telephone call, during which the study was briefly presented and the request to participate was made. Following this initial contact, two information sheets were handed out, one for the adolescent girls and one for their parents. Consent from the adolescent girls was obtained in stages: the study was first presented to the girls by a parent or, in a few cases, teacher, to allow the girls to consider participation in a safe space. Some of the girls had follow-up questions which were answered via a text message. Once a positive response was received, meetings were set up between the first author and each girl, at a location of the latter’s choice and in presence of an accompanying person if they wished. When meeting the participant, oral and written information was provided to clarify the purpose of the study and their involvement. At this point written consent was obtained from the girl and the parents by the researcher.

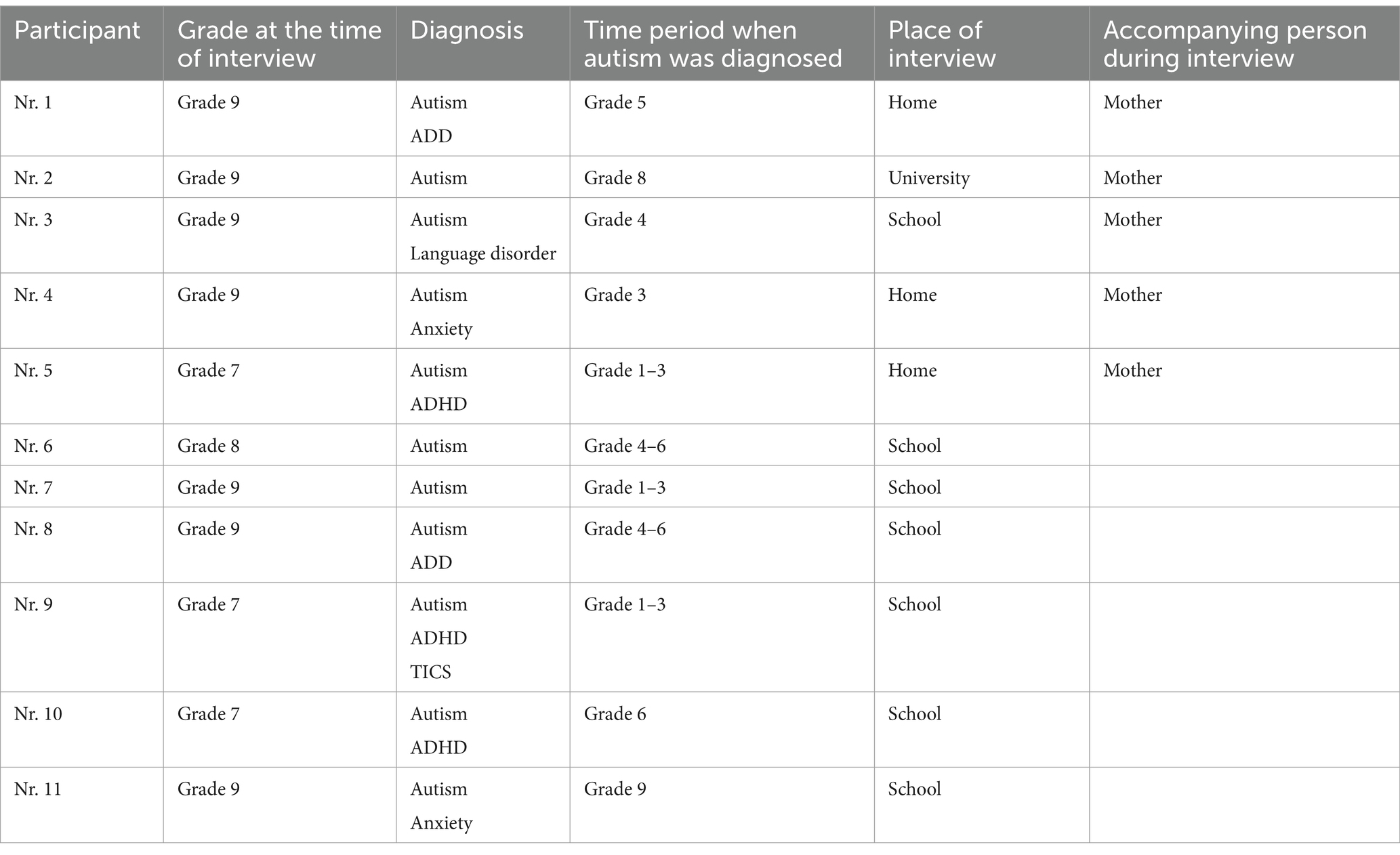

All participants attended mainstream secondary schools, grade 7–9. The size of the schools they attended varied, from about 100 to 500 students. Class size varied from 20 to 30 students. Each participant belonged to a class and, through that, linked to a mentor who had an overview of their situation at school and collaborated with them and their family. During the school day students met different subject teachers and moved between different classrooms, as is typical in a Swedish secondary school setting. Of the 11 girls, nine had been diagnosed with autism during their primary and middle school years and two more recently while in secondary school. Eight participants reported having other diagnoses as well as autism, with ADHD, ADD, and anxiety being most frequently reported. The presence of multiple diagnoses is not surprising and is reflective of autism in general (Kopp, 2010; Kutscher, 2014). Nine of the 11 participants had various types of support, adjustment, and accommodations in place. Four participants had the option of moving between the regular class and a small group setting with increased adult support during the day, and five had individual plans that exempted them from certain compulsory subjects. All participants spoke Swedish as their mother tongue. Their parents could be described as Caucasian and, based on their profession, middle-class. Specific data on socioeconomic status were not recorded. Information regarding the participants’ educational and diagnostic status, and interview situation is presented in Table 1. To maintain confidentiality pseudonyms used in the article for participants are not linked to the information provided in the table.

2.2 Semi-structured interview

Each participant was interviewed by the first author on two occasions a few weeks apart. As the participants were vulnerable in terms of both their age and their diagnosis, which can entail communication difficulties, these meetings were planned with particular sensitivity. A conscious effort was made to give participants significant influence over the interview situation so that they could feel safe and comfortable. They were free to select their preferred place and time and given the option of bringing a companion if this would make them feel more at ease. Five girls attended the interviews with their mothers. The interviews were approximately 30–50 min in length. Each meeting began by informing the participant that they were not obliged to answer and could ask for a break or stop the interview at any point. One participant did not want the first interview to be recorded. Otherwise, the remaining 21 interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim, and participants were assigned a pseudonym. Both interviews were developed and conducted as part of a broader piece of research focusing on autistic girls’ opportunities for participation in secondary school.

The first interview followed an interview guide built upon both previous research and the authors’ understanding of organisation of Swedish secondary schools. The open-ended questions were designed to allow exploration of a typical school day, both pedagogical and social. The main questions were of a visual and practical nature such as “On this line, where the number one is terrible and number 10 is great, can you fill in what number you think of when I say math?.” Several questions then followed that aimed to deepen and contextualise the girl’s rating, addressing the classroom environment, collaboration, relationships with peers and staff, treatment, support, and learning strategies. Most of the participants had been through some form of school failure, and our approach was to lead the questions in a stepwise and sensitive manner to capture different dimensions of their experiences of everyday life in school (Punch, 2002; Rasmussen and Pagsberg, 2019). The second interview was developed using the information and analysis from the first interview and was designed in the form of a mind map of questions and statements that the researcher and participant explored together. One of the themes discussed was “making sense of the diagnosis,” including if and how it had affected the girl’s life and what she felt it was essential for those around her to consider.

2.3 Data analysis

Each participant’s narrative from the first and second interviews was analysed according to the principles of Reflexive Thematic Analysis as outlined by Braun and Clarke (2021, 2023). The interviews were conducted and analysed by the first author, who has a background as a teacher and special needs educator. The first author listened to the interviews multiple times to familiarise with the girls’ narratives, and through this process the author’s experience within the school context was supportive to shape an idea and understanding of the girls’ daily school life. In order to forefront participant-based meaning a predominantly inductive approach to coding was adopted. The codes were then clustered and organised into themes. For example, phrases and words dealing with loneliness, bullying, and absenteeism became codes which then formed a cluster dealing with exclusion. When the codes were further analysed by re-reading the interviews it became clear that, in context, the exclusion cluster related to how the girls perceived others’ perceptions and understanding of autism, i.e., the label in a school context. The process can be described as circular as various themes were explored further and sometimes became intertwined to form a new theme During this process it was also essential to take a theoretical approach through research literature, and most important to actively reflect on the first author’s situatedness within the study with the second author as well as discuss the ongoing analysis and emerging themes with her. In the last steps of the analysis, the emphasis was on understanding how the girls gave meaning to the way they were navigating in their everyday school lives, i.e., how they made different choices based on their perceptions and understanding of their surrounding environment. This led to the identification of three interlinked themes, which highlights the tensions in daily school life as described by participants.

3 Findings

The first theme relates to the different meanings the diagnosis had for the participants on a personal level, and how this sensemaking has implications for the way they navigate in school. The second theme relates to how they make sense of and experience being labelled within the secondary school context. Building on theme one and two, the final theme focuses specifically on how autistic girls navigate disclosure within the school context. Quotes from participants along with their pseudonym have been included in order to illustrate and validate the themes. The findings are summarised and visualised in Figure 1.

3.1 Navigating the diagnosis on a personal level

In many of the participant’s accounts the diagnosis of autism was perceived as a route to greater self-understanding. The diagnosis seemed to have helped participants re-script troubling previous experiences at school and understand them. Accounts of their own failure were gradually replaced by recognition and understanding of the actual difficulties and challenges they had faced in the school context. For most of the participants this was described as a positive experience, giving them more insight into their own individual preferences and functioning.

I might see myself in a slightly different way after the diagnosis […] I guess it’s a positive change, since the diagnosis has enabled me to work more on stuff I have difficulty with. (Tove)

It is a relief to have a diagnosis, to understand why things can be difficult for me. […] I would say the social part of it is challenging, I need a lot of time for myself. (Thea)

Over time, participants noted that new insights into some of their own difficulties with the concept of autism were important in navigating their current situation. These not only gave them a sense of better understanding of themselves but also aided them in both coping and in developing strategies to deal with some of these challenges. Thea described her experience of this development:

At first, I didn’t understand when people made jokes all the time, sarcasm and stuff like that. But I learned, so now I do understand […] and my friends also explained.

Although being able to better recognise how their diagnosis affected them enabled participants to take positive action, the diagnosis also risked being seen as ‘evidence’ that there is something permanently wrong with them. Tove, a girl who had recently received her diagnosis having struggled with friends and relationships for many years, elaborated on this feeling: “Now I understand little why I’m so different, why no one wants to be with me. Now I’ve got an explanation for it anyway.”

While participants’ accounts show that their autism diagnosis was important to their self-understanding, it is striking that little attention seems to have been paid to supporting them to do this post-diagnosis. Six of the girls who had been diagnosed in middle school (year 4–6) retrospectively described how they expected, and still wish that they had been provided with, assistance in understanding the connection between autism and the difficulties and challenges they were experiencing, many of which they did not see their peers struggling with.

Before I was diagnosed, I wondered “What’s wrong with me?”’ I would build up expectations, everything will be better soon. But once I received the diagnosis, nothing happened or changed, maybe the diagnosis didn’t have any meaning? (Beata)

This need for a deeper self-understanding was not fulfilled the time after receiving the diagnosis. According to their narratives, none of the participants felt that they had received sustainable support from the health care system to make sense of how the diagnosis would affect them and no such support was provided from their school. When asked about how she felt when she received the diagnosis, and whether getting it somehow changed how she perceived herself, Beata was emotional and struggled to find the right words, becoming silent for a while. She had tried unsuccessfully to get support to explore the possible impact on a personal level and explained:

I wanted help, and I was supposed to have a meeting with the school counsellor, but it never happened. Well, I tried anyway… Because I realised that I’ve never really reflected on it. And I haven’t talked about it with anyone close to me either.

With little external support to make sense of the diagnosis on offer, over time many of the girls seemed to have taken on responsibility themselves to search for knowledge and develop the understanding they desired, as illustrated in Tove’s statement:

I have only been at BUP [Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services] a few times. I have found a lot of information on the Internet, I’ve read quite a lot about autism because I think it’s exciting now that I have it. When you read about it, you can find out things that help you in your everyday life.

It is important to note, that not all of the participants expressed that the autism diagnosis was valuable for self-understanding or the need for support. On the contrary, some distanced themselves from the diagnosis, demonstrating what would seem to be indifference.

There is another diagnosis, I think it is called TICS or something like that, I hate it! […] Autism, I don’t know, it doesn’t bother me, I don’t care about that diagnosis. (Tyra)

Receiving an autism diagnosis hasn’t helped me in school because I already have ADD […] ADD is not a good diagnosis, it sucks! So, when I got autism, it was nothing new really. Sure, you can write it down on paper, in my world I couldn’t care less. (Klara)

As evidenced by these accounts, Tyra and Klara have other diagnoses in addition to autism. This was the case for seven of the participants in this study and having multiple diagnoses is not uncommon (Kopp, 2010; Kutscher, 2014; Stark et al., 2021). Both Tyra and Klara illustrate the complexity of understanding how different diagnoses may be intertwined. It seems that at some point an additional diagnosis stops making sense and becomes more of a burden, as expressed by Frida on receiving yet another diagnosis:

I didn’t want it! It was so annoying to get it, I can tell you that! You know, when they told me I had autism.

As noted earlier, having received little support to make sense of the autism diagnosis on a personal level or how it might relate to other diagnoses, for some of the girls autism ended up becoming just another label.

3.2 Navigating the autism label in a school context

An autism diagnosis was not just important to the participants on a personal level but was also ascribed meaning within the social context of school, both by staff and other students.

Participants’ narratives evidence how the diagnostic label legitimised their needs and increased their access to support and adjustments. For several participants, the label made them feel seen and heard by school staff and seemed to provide confirmation that their needs were legitimate. In this context, the participants expressed a sense of relief about no longer being forced to be exposed to situations in school that elicited anxiety and subsequent non-attendance. Moa, who had a history of anxiety and absenteeism, reflects on the impact of the autism label:

The diagnosis has changed school, I don’t have to do all those things I had to do before I got the diagnosis, like presenting in front of the class […] It makes it easier to go to school, because it used to be troublesome.

Within the school context, the autism label both explained the difficulties faced by the girls and was perceived as a key for accessing the right support. A few participants explained that post-diagnosis they were met with better understanding by the teachers and provided with adjustments and strategies to help them cope with daily school life. Others, like Frida, described that support had already been in place but was modified post-diagnosis to better match her needs.

However, some participants appreciated the diagnosis but did not necessarily see its value in school and expressed clear resistance to the label as it limited perceptions of them. Three of the participants expressed resistance to the view that the diagnosis itself should in some way facilitate life in school, questioning the assumed connection between adjustments in the learning environment and autism.

When I need adjustments or support, I don’t blame it on my diagnosis really. It’s just how I function. (Bianca)

Others, like Tove, elucidated how a structured learning environment would benefit all students, a claim often raised in research on inclusive education (Nilholm and Alm, 2010; Olsson and Nilholm, 2023).

I suppose that for many students it’s difficult when teacher doesn’t explain properly. It can be difficult for many who do not have autism!

One particular concern driving resistance to the label related to the stereotypes associated with it, that is, how peers in the school setting view autism and common misconceptions. When Thea discussed the meaning of autism, she was quick to say that she gets the support she needs, but expressed sadness that others think only in terms of stereotypes.

It is sad that most people don’t really know what it means and only think of the stereotype. Like you’re supposed to be super smart at everything, like in the movies!

The fear of being stigmatised was evident in eight of the participants’ accounts. They described how having the diagnostic label can diminish them, giving accounts of being put in a box and seen as odd, based on misconceptions associated with autism. There was also an awareness that the label might have negative consequences for social interaction and relationships. Bianca, who has not shared her diagnosis with any of her peers at her new school, elaborates on this feeling:

When in school I’m really aware of my diagnosis all the time. If I hang out with some people, what will happen if I say this or this? Will they notice anything strange?

It therefore seemed challenging for many of the girls to embrace the diagnosis. Olivia elaborated on this complex issue:

It’s not really something I should be ashamed of, but I find it a bit hard to be labelled as different.

This sense of being perceived by others as different, accompanied by a desire to belong, created a field of tension in the girls’ accounts and seemed to have a strong impact on how they socially navigated their everyday school lives. Having previously experienced isolation and victimisation, and in some cases continuing to experience loneliness, their narratives reflected not so much how I am, but rather how I should be in order to have a functioning social life. This finding aligns with previous research on autistic girls which highlights difficulties with friendships and norms, and their use of various strategies to fit in (Dean et al., 2017; Myles et al., 2019; Tierney et al., 2016; Tubío-Fungueiriño et al., 2021).

3.3 Navigating disclosure

Being aware of the stereotypes associated with the label of autism, participants reflected in nuanced ways on when and why to disclose their diagnosis. None of the participants were completely open about their diagnosis, and they expressed a general hesitance:

I don’t want to tell people about my autism, I know it’s normal, but everyone doesn’t need to know. (Olivia)

You know, I really don’t speak out loud to everyone that I have a diagnosis! (Moa).

For nine of the participants, misconceptions about the diagnosis kept them from disclosing to more than just the people closest to them. They worried that stereotypical understandings of the label would change others’ perceptions of them, not reflecting who they actually are. Thus, rather than provoking understanding, they feared that disclosure might have the opposite effect and result in stigma.

This norm that surrounds autism, not many people know what it actually means. […] So, if I say that I have autism, everyone else goes like “Oh!” as if you are mentally disturbed. The awareness of autism in others is important, so that you dare to be yourself. (Beata)

Beata emphasises the importance of daring to be yourself and feeling safe with how the diagnosis will be received, which entails others having an awareness which extends beyond stereotypes.

Participants explained how they were navigating the dilemma of disclosure in secondary school in different ways. For a majority, disclosure was apparently limited to a few trusted friends. For some, this was clearly shaped by past experiences in which disclosing their autism had resulted in stigma and bullying:

I used to inform, but there were people who teased me then. […] I usually wait until I know the person better before I tell and explain. It’s quite difficult to explain what it means, because hardly anyone is familiar with it. (Thea)

In contrast, four of the participants saw little purpose in disclosing their diagnosis at school. The sole underlying reason for this was the negative consequences of stigmatisation, such as becoming the ‘strange child’. Klara, who had changed schools between primary and secondary level in the hope of a new start, still felt that she had no friends and described her experience:

You get stared at in a way! I don’t know why, but no one in your class wants to become friend with the peculiar child who needs a lot of extra support.

It is noteworthy that participants’ decisions regarding disclosure were not always based on social premises, but also took into consideration the possible consequences for their school work. Such a pragmatic approach to disclosure was adopted by Tove, who based her decision on whether or not sharing her diagnosis had an impact on her achievements at school:

If I collaborate with someone in my class, I can tell them about my autism. Quite a few people know about it. I don’t personally change in any way, just that they know that I have autism.

Navigating disclosure thus seemed to be largely driven by a wish to be understood and, at the same time, a fear of stigmatisation, i.e., being perceived not just as different, but “different-er” (Mesa and Hamilton, 2022, p. 225).

4 Discussion

This qualitative study explored how adolescent autistic girls navigate their diagnosis within a mainstream school context in Sweden, a setting where the concept of inclusion underpins the vision and organisation of schooling. Through the girls’ narratives, we identified a critical need for guidance post diagnosis to build their self-understanding and enable them to develop strategies for navigating school and their social relationships more effectively. In the absence of this support, the girls seemed to navigate their everyday lives by creating a personal understanding of autism within the context of their families and their social surroundings. Most strikingly, the girls expressed awareness of, and vigilance about, the perceptions and understanding of autism in their school setting, which has consequences in terms of support, but also in terms of exclusion and stigmatisation. This created a field of tension between the social context of school, its values and norms, and the girls’ personal experiences and views about autism.

On a personal level, the findings show that a diagnosis is both a supportive factor for greater self-understanding and can serve as a recognition of the challenges that the girls have experienced in their lives, which is in turn perceived as a relief and a basis for coping strategies. This knowledge and insight helped them to navigate their current situation, supporting the importance of a timely diagnosis (Duvekot et al., 2017; Kanfiszer et al., 2017; Loomes et al., 2017). We noted that participants’ paths to knowledge and insight, i.e., a deeper understanding of what autism entails for them in their life situation, were described as unclear, and they expressed a clear desire for guidance. Despite participants’ quest for a nuanced and personal understanding of their diagnosis, their experiences point to the absence of collective guidance for how this process should be handled by society at large. This has been described in earlier research (Falkmer et al., 2012; Milner et al., 2019) as implicitly making the girl and her family responsible for processing and making sense of the diagnosis.

The process of building a self-understanding post diagnosis is complex (Jones et al., 2015; Mogensen and Mason, 2015) and, with queues of over a year to get a neurodevelopmental assessment in Sweden, debates have focused on getting a diagnosis rather than what happens post diagnosis. It can be argued that, by leaving it to themselves to develop a deeper self-understanding in relation to the diagnosis, the social surroundings which the girls must navigate become immensely influential: the relevant sociocultural discourse and its values and norms will shape how they develop their sense of self (Mesa and Hamilton, 2022; Mo et al., 2022). Moreover, at a time when an increasing numbers of girls are receiving an autism diagnosis (Carpenter et al., 2019; Kopp, 2010), a large body of research is driven by a psycho-medical perspective which focuses on improving diagnostic tools and interventions based on autism symptomatology (Pellicano and Houting, 2022), failing to contextualise individual experiences. As a result, less attention is paid to the issues that the girls in this study raise, such as their wish for post diagnosis guidance to understand autism for themselves, taking into account their individual abilities and the contexts in which they find themselves.

While on a personal level having a diagnosis was mostly seen positively, the girls expressed ambivalence about making sense of the diagnosis in the school context. This ambivalence centred on a dichotomy between educational and social participation. As a result of being diagnosed, there was a feeling of being seen and heard in the educational context and receiving increased and positively modified support. At the same time, the findings indicate that the girls are highly aware that being labelled autistic can be perceived as a disadvantage by others. In this study, participants were concerned about being excluded and stigmatised within the school context. Previous research on autism suggests that this concern is justified, as it has found that loneliness increases from adolescence through early adulthood (Schiltz et al., 2024) which itself has negative consequences (Kwan et al., 2020).

Previous research has used concepts such as masking, camouflaging, and mirroring to explain how autistic girls strive to fit into the norm. Strategies which in itself has a very negative long-term impact on their wellbeing and mental health (Goodall and Mackenzie, 2019; Mesa and Hamilton, 2022; Sedgewick et al., 2018; Tomlinson et al., 2020; Tubío-Fungueiriño et al., 2021). However, the current study extends and nuances previous research since it contextualises girls’ experiences and highlights how the realm within the walls of school, with its particular norms and values, shapes how the girls navigate their everyday lives. It recognises the girls’ awareness of how the values and norms within the school context affect them and that they deal constantly with stigma, navigating between those aspects of school that are beneficial and supportive for them and the fear of stigmatisation (Goffman, 1963). Participants described having to justify themselves and the feeling of being seen as “odd,” demonstrating the fear of how other people might respond to and interact with them (Fondelli and Rober, 2017). This tension risks triggering self-stigma (Goffman, 1963), in which the girls internalise negative experiences and the views of others. A systematic review by Han et al. (2022) showed that autistic people often feel stigmatised due to negative treatment by and the attitudes of others, which affects their self-perception. This has also been illustrated in a Swedish study which showed how, over time, a girl with ADHD was constructed as disabled in a school context and ultimately identified herself as such in a negative way (Hjörne and Evaldsson, 2015). Overall, this feeling of stigmatization has a significant impact on their quality of life; it links back to the girls’ wellbeing and escalation of risk to co-occurring conditions, e.g., school absence, anxiety, self-harm and depression (Kwan et al., 2020; Schiltz et al., 2024; Stark et al., 2021).

Adolescence is a crucial and in many ways revolutionary stage in life (Kroger et al., 2010). Significant developments take place, and individuals can face crossroads at which life can take a turn for the better or the worse. For adolescent girls with autism, one of these crossroads is coping with disclosure, weighing up the benefits and consequences in the context in which they find themselves. The girls in this study describe the importance of feeling safe and daring to be themselves. Most of them have disclosed to only a few people, aligning with previous research (Milner et al., 2019; Rainsberry, 2017), and are caught between a desire for acceptance and the fear of stigma and exclusion. This illustrates that labels have the power to taint an individual’s identity (Goffman, 1963), and the importance of nurturing and supporting a positive identity, showing that further research into the impacts of a diagnosis and the challenges faced by autistic girls is needed.

Swedish schools are supposed to work inclusively and have a clear ambition to do so but there are shortcomings in practice (Bölte et al., 2021; Leifler et al., 2022; Lüddeckens et al., 2022). Alarmingly, research demonstrates that adolescent females in Swedish secondary schools experience more stress and poorer mental health than adolescent males (Giota and Gustafsson, 2017). Even more concerning is that autistic girls in secondary school are at risk of more absenteeism and failing grades, which create significant risks for their future and wellbeing (Anderson, 2020; Stark et al., 2021). In the current study, the girls asked for greater acknowledgment and acceptance of diversity, based on an understanding which accommodates differences without imposing negative values or stereotypical perceptions (Moore et al., 2022). This points to the need for better communication to build mutual understanding about differences (Kanfiszer et al., 2017; Ranson and Byrne, 2014). Focusing research, knowledge, and discussion purely on what autism is in a biomedical sense risk reinforcing the notion that autism is something fundamentally different, allowing an exclusionary discourse to prevail at the expense of working towards participation and inclusion (Fondelli and Rober, 2017). Our findings emphasise the need for greater focus on awareness of neurodiversity within school contexts, not just in terms of teaching strategies and the limitations associated with autism, but actually working on developing acceptance of neurodiversity among peers, making the school environment a space in which all students feel accepted and valued for being who they are (Conn, 2014; Pellicano and Houting, 2022). Swedish schools, with their ongoing commitment to and processes for inclusion, have been paying attention to various strategies and adjustments to make the school environment more accessible for students with autism, yet the girls in this study stress the need for further work and attention on developing a deeper understanding and acceptance of diversity.

5 Conclusion

An important agenda behind this study is to listen to the voices of autistic girls within an educational context. By listening to and interpreting the girls’ narratives within a social context, the study contributes a deeper and broader understanding of the girls’ situation, and how they navigate everyday school life and relationships in a field of tension between perceptions, expectations, and hidden norms. Their experiences and perspectives provide useful insights not only about autism but also about the need to understand that diversity is not in itself a deficiency, but that others’ misconceptions of diversity have an impact on the girls’ agency and wellbeing at school: as Beata emphasised, “to dare to be yourself…” Our approach to interviewing the young girls was to provide a safe space for them to articulate what they felt it was important for others to know and what they wanted the research to communicate. Listening to the girls and giving them the freedom to discuss their experiences within a school context, on their own terms, resulted in a more profound and nuanced understanding of their experience which enriches our knowledge of this group (O’Dell et al., 2016; Taneja-Johansson, 2023). A limitation of this research is that the girls in this study could be described as coming from a relatively homogeneous social group, living with Swedish-speaking parents in middle-class areas, meaning that the voices and experiences of those with other ethnicities and socio-economic backgrounds are absent (Taneja-Johansson, 2023). A more diverse sample could contribute to more nuanced and varied outcomes. Further, neither of the authors are autistic and we acknowledge our subjectivity and inability to fully understand the girls’ accounts while observing through a neurotypical lens (Stenning and Rosqvist, 2021). Nevertheless, the findings provide important insights into adolescent autistic girls’ navigation of everyday school life in secondary school, highlighting questions as to whether our understanding of support in the school context is sufficient and adequately matches the needs and realities of the girls. It would be interesting to investigate these questions further.

In their school life, the girls navigate between making sense of the diagnosis in the personal sphere and the social expectations of the context. Their accounts illustrate the complex reality of their lives post diagnosis, reflecting the often limited sensitivity to diversity in schools and the personal consequences this has in terms of fear of stigmatisation, during a stage of life that requires thoughtfulness and conscious awareness from the surroundings given that significant developments are taking place in a short period of time (Botha et al., 2022; O’Connor et al., 2024; Schiltz et al., 2024). Arguably, these findings are not new but rather confirm and support a longstanding and growing body of research on autistic girls. That is, knowledge and research exist but are still not sufficiently made visible in school policies and practices, with negative consequences for girls’ wellbeing and schooling. Important implications for school professionals include the need to develop a wider understanding of these girls’ situation, influencing approach to understanding and responds to the girls’needs. Drawing on this study, there is a need for further research addressing the social experiences of autistic girls in relation to age and educational contexts, in order to create a more comprehensive and in-depth understanding. Further, their narratives make visible a complexity that is interesting. The feeling of being different is described by the girls both in relation to their attempts to fit into the norms as a girl and the attempt to understand autism beyond the stereotypical description based on males. We glimpse a tension between issues related to gender and issues related to having a diagnosis. A two-fold dilemma becomes visible in the girls’ situation: being an autistic girl may be stigmatising both in relation to neurotypical girls and to autistic boys (Kopp and Gillberg, 2011; McLinden and Sedgewick, 2023; Sedgewick et al., 2018). This creates a lack of understanding that should be explored further in both future research and everyday practice, as deeper understanding may contribute to better and more sensitive support.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

HJ: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SJ: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research is part of a doctoral dissertation funded by University of Gothenburg, Faculty of Education, Department of Education and Special Education.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the girls who participated in this study and their families for support, they made this research possible.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^In this article we use identity-first language, reflecting norms within the wider literature (Vivanti, 2020). It is, however, important to note that the study participants were not explicitly asked about their preferences in terms of identity-first or person-first terminology. In the context of this study, we felt that this question may have had an impact on the perspectives we were asking them to share.

2. ^Dnr 2022-01274-01.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th Edn. Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Anderson, L. (2020). Schooling for pupils with autism spectrum disorder: parents’ perspectives. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 50, 4356–4366. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04496-2

Arvidsson, O., Gillberg, C., Lichtenstein, P., and Lundström, S. (2018). Secular changes in the symptom level of clinically diagnosed autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 59, 744–751. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12864

Bargiela, S., Steward, R., and Mandy, W. (2016). The experiences of late-diagnosed women with autism spectrum conditions: an investigation of the female autism phenotype. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 46, 3281–3294. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2872-8

Bölte, S., Leifler, E., Berggren, S., and Borg, A. (2021). Inclusive practice for students with neurodevelopmental disorders in Sweden. Scand. J. Child Adoles. Psychiatr. Psychol. 9, 9–15. doi: 10.21307/sjcapp-2021-002

Botha, M., Dibb, B., and Frost, D. M. (2022). “autism is me”: an investigation of how autistic individuals make sense of autism and stigma. Disab. Soc. 37, 427–453. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2020.1822782

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2023). Toward good practice in thematic analysis: avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. Int. J. Transgender Health 24, 1–6. doi: 10.1080/26895269.2022.2129597

Carpenter, B., Happé, F., and Egerton, J. (2019). Girls and autism: Educational, family and personal perspectives. New York, NY: Routledge.

Conn, C. (2014). Autism and the social world of childhood: A sociocultural perspective on theory and practice. Oxford: Routledge.

Cridland, E. K., Jones, S. C., Caputi, P., and Magee, C. A. (2014). Being a girl in a boys’ world: investigating the experiences of girls with autism spectrum disorders during adolescence. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 44, 1261–1274. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1985-6

Dean, M., Harwood, R., and Kasari, C. (2017). The art of camouflage: gender differences in the social behaviors of girls and boys with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 21, 678–689. doi: 10.1177/1362361316671845

DePape, A.-M., and Lindsay, S. (2016). Lived experiences from the perspective of individuals with autism spectrum disorder: a qualitative meta-synthesis. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disab. 31, 60–71. doi: 10.1177/1088357615587504

Duvekot, J., van der Ende, J., Verhulst, F. C., Slappendel, G., van Daalen, E., Maras, A., et al. (2017). Factors influencing the probability of a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in girls versus boys. Autism 21, 646–658. doi: 10.1177/1362361316672178

Edwards, C., Love, A. M. A., Jones, S. C., Cai, R. Y., Nguyen, B. T. H., and Gibbs, V. (2024). ‘Most people have no idea what autism is’: unpacking autism disclosure using social media analysis. Autism 28, 1107–1119. doi: 10.1177/13623613231192133

Falkmer, M., Granlund, M., Nilholm, C., and Falkmer, T. (2012). From my perspective - perceived participation in mainstream schools in students with autism spectrum conditions. Dev. Neurorehabil. 15, 191–201. doi: 10.3109/17518423.2012.671382

Fondelli, T., and Rober, P. (2017). ‘He also has the right to be who he is … ’. An exploration of how young people socially represent autism. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 21, 701–713. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2016.1252431

Giota, J., and Gustafsson, J.-E. (2017). Perceived demands of schooling, stress and mental health: changes from grade 6 to grade 9 as a function of gender and cognitive ability. Stress. Health 33, 253–266. doi: 10.1002/smi.2693

Goodall, C., and Mackenzie, A. (2019). What about my voice? Autistic young girls’ experiences of mainstream school. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 34, 499–513. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2018.1553138

Göransson, K., Nilholm, C., and Karlsson, K. (2011). Inclusive education in Sweden? A critical analysis. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 15, 541–555. doi: 10.1080/13603110903165141

Gould, J. (2017). Towards understanding the under-recognition of girls and women on the autism spectrum. Autism 21, 703–705. doi: 10.1177/1362361317706174

Grigorian, K., Östberg, V., Raninen, J., and Brolin Låftman, S. (2024). Loneliness, belonging and psychosomatic complaints across late adolescence and young adulthood: a Swedish cohort study. BMC Public Health 24:642. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-18059-y

Han, E., Scior, K., Avramides, K., and Crane, L. (2022). A systematic review on autistic people’s experiences of stigma and coping strategies. Autism Res. 15, 12–26. doi: 10.1002/aur.2652

Hjörne, E., and Evaldsson, A.-C. (2015). Reconstituting the ADHD girl: accomplishing exclusion and solidifying a biomedical identity in an ADHD class. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 19, 626–644. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2014.961685

Humphrey, N., and Lewis, S. (2008). ‘make me normal’: the views and experiences of pupils on the autistic spectrum in mainstream secondary schools. Autism 12, 23–46. doi: 10.1177/1362361307085267

Jablonska, B., Ohlis, A., and Dal, H. (2022). Autismspektrumtillstånd och adhd bland barn och ungdomar i Stockholms län: förekomst i befolkningen samt vårdkonsumtion. En uppföljningsrapport. [Autism spectrum disorder and ADHD among children and youth in Stockholm county: incidence in the population and care consumption. A follow-up report]. Stockholm: Center for Epidemiology and Medicine, region Stockholm.

Jones, J. L., Gallus, K. L., Viering, K. L., and Oseland, L. M. (2015). ‘Are you by chance on the spectrum?’ Adolescents with autism spectrum disorder making sense of their diagnoses. Disab. Soc. 30, 1490–1504. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2015.1108902

Kanfiszer, L., Davies, F., and Collins, S. (2017). ‘I was just so different’: the experiences of women diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder in adulthood in relation to gender and social relationships. Autism 21, 661–669. doi: 10.1177/1362361316687987

Kapp, S. K., Gillespie-Lynch, K., Sherman, L. E., and Hutman, T. (2013). Deficit, difference, or both? Autism and neurodiversity. Dev. Psychol. 49, 59–71. doi: 10.1037/a0028353

Kopp, S. (2010). Girls with social and/or attention impairments. Diss. Göteborg: University of Gothenburg.

Kopp, S., Asztély, K. S., Landberg, S., Waern, M., Bergman, S., and Gillberg, C. (2023). Girls with social and/or attention deficit re-examined in young adulthood: prospective study of diagnostic stability, daily life functioning and social situation. J. Attention Disorder 27, 830–846. doi: 10.1177/10870547231158751

Kopp, S., and Gillberg, C. (1992). Girls with social deficits and learning problems: autism, atypical asperger syndrome or a variant of these conditions. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1, 89–99. doi: 10.1007/BF02091791

Kopp, S., and Gillberg, C. (2011). The autism spectrum screening questionnaire (ASSQ)-revised extended version (ASSQ-REV): an instrument for better capturing the autism phenotype in girls? A preliminary study involving 191 clinical cases and community controls. Res. Dev. Disabil. 32, 2875–2888. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.05.017

Kroger, J., Martinussen, M., and Marcia, J. E. (2010). Identity status change during adolescence and young adulthood: a meta-analysis. J. Adolesc. 33, 683–698. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.11.002

Kutscher, M. L. (2014). Kids in the syndrome mix of ADHD, LD, autism Spectrum, Tourette’s, anxiety and more! London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Kwan, C., Gitimoghaddam, M., and Collet, J.-P. (2020). Effects of social isolation and loneliness in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities: a scoping review. Brain Sci. 10, 1–36. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10110786

Leifler, E., Borg, A., and Bölte, S. (2022). A multi-perspective study of perceived inclusive education for students with neurodevelopmental disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 54, 1611–1617. doi: 10.1007/s10803-022-05643-7

Leifler, E., Carpelan, G., Zakrevska, A., Bölte, S., and Jonsson, U. (2021). Does the learning environment ‘make the grade’? A systematic review of accommodations for children on the autism spectrum in mainstream school. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 28, 582–597. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2020.1832145

Leveto, J. A. (2018). Toward a sociology of autism and neurodiversity. Social. Comp. 12:e12636. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12636

Lgr22 (2022). Läroplan för Grundskolan, Förskoleklassen och Fritidshemmet [curriculum for compulsory school, preschool class and school-age Educare]. Femte upplagan. Stockholm: Skolverket.

Loomes, R., Hull, L., and Mandy, W. P. L. (2017). What is the male-to-female ratio in autism spectrum disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. 56, 466–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.013

Lüddeckens, J., Anderson, L., and Östlund, D. (2022). Principals’ perspectives of inclusive education involving students with autism spectrum conditions – a Swedish case study. J. Educ. Adm. 60, 207–221. doi: 10.1108/JEA-02-2021-0022

McLinden, H., and Sedgewick, F. (2023). ‘The girls are out there’: professional perspectives on potential changes in the diagnostic process for, and recognition of, autistic females in the UK. Br. J. Special Educ. 50, 63–82. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12442

Mesa, S., and Hamilton, L. G. (2022). “We are different, that’s a fact, but they treat us like we’re different-er”: understandings of autism and adolescent identity development. Adv. Autism 8, 217–231. doi: 10.1108/AIA-12-2020-0071

Milner, V., McIntosh, H., Colvert, E., and Happé, F. (2019). A qualitative exploration of the female experience of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). J. Autism Dev. Disord. 49, 2389–2402. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-03906-4

Mo, S., Viljoen, N., and Sharma, S. (2022). The impact of socio-cultural values on autistic women: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Autism 26, 951–962. doi: 10.1177/13623613211037896

Mogensen, L., and Mason, J. (2015). The meaning of a label for teenagers negotiating identity: experiences with autism spectrum disorder. Sociol. Health Illn. 37, 255–269. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12208

Moore, I., Morgan, G., Welham, A., and Russell, G. (2022). The intersection of autism and gender in the negotiation of identity: a systematic review and metasynthesis. Fem. Psychol. 32, 421–442. doi: 10.1177/09593535221074806

Munroe, A., and Dunleavy, M. (2023). Recognising autism in girls within the education context: reflecting on the internal presentation and the diagnostic criteria. Ir. Educ. Stud. 42, 561–581. doi: 10.1080/03323315.2023.2260371

Myles, O., Boyle, C., and Richards, A. (2019). The social experiences and sense of belonging in adolescent females with autism in mainstream school. Educ. Child Psychol. 36, 8–21. doi: 10.53841/bpsecp.2019.36.4.8

Nasir, N. I. S., and Hand, V. M. (2006). Exploring sociocultural perspectives on race, culture, and learning. Rev. Educ. Res. 76, 449–475. doi: 10.3102/00346543076004449

Nilholm, C., and Alm, B. (2010). An inclusive classroom? A case study of inclusiveness, teacher strategies, and children’s experiences. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 25, 239–252. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2010.492933

Nordin, V., Palmgren, M., Lindbladh, A., Bölte, S., and Jonsson, U. (2023). School absenteeism in autistic children and adolescents: a scoping review. Autism 28, 1622–1637. doi: 10.1177/13623613231217409

O’Connor, R. A. G., Doherty, M., Ryan-Enright, T., and Gaynor, K. (2024). Perspectives of autistic adolescent girls and women on the determinants of their mental health and social and emotional well-being: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of lived experience. Autism 28, 816–830. doi: 10.1177/13623613231215026

O’Dell, L., Bertilsdotter Rosqvist, H., Ortega, F., Brownlow, C., and Orsini, M. (2016). Critical autism studies: exploring epistemic dialogues and intersections, challenging dominant understandings of autism. Disab. Soc. 31, 166–179. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2016.1164026

Olsson, I., and Nilholm, C. (2023). Inclusion of pupils with autism – a research overview. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 38, 126–140. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2022.2037823

Pellicano, E., and Houting, J. (2022). Annual research review: shifting from ‘normal science’ to neurodiversity in autism science. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 63, 381–396. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13534

Posserud, M. B., Skretting Solberg, B., Engeland, A., Haavik, J., and Klungsøyr, K. (2021). Male to female ratios in autism spectrum disorders by age, intellectual disability and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 144, 635–646. doi: 10.1111/acps.13368

Punch, S. (2002). Research with children: the same or different from research with adults? Childhood 9, 321–341. doi: 10.1177/0907568202009003005

Rainsberry, T. (2017). An exploration of the positive and negative experiences of teenage girls with autism attending mainstream secondary school. Good Autism Prac. 18, 16–31.

Ranson, N. J., and Byrne, M. K. (2014). Promoting peer acceptance of females with higher-functioning autism in a mainstream education setting: a replication and extension of the effects of an autism anti-stigma program. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 44, 2778–2796. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2139-1

Rasmussen, P. S., and Pagsberg, A. K. (2019). Customizing methodological approaches in qualitative research on vulnerable children with autism spectrum disorders. Societies 9:75. doi: 10.3390/soc9040075

Ryan, C., Coughlan, M., Maher, J., Vicario, P., and Garvey, A. (2021). Perceptions of friendship among girls with autism spectrum disorders. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 36, 393–407. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2020.1755930

Schiltz, H., Gohari, D., Park, J., and Lord, C. (2024). A longitudinal study of loneliness in autism and other neurodevelopmental disabilities: coping with loneliness from childhood through adulthood. Autism 28, 1471–1486. doi: 10.1177/13623613231217337

Sedgewick, F., Hill, V., and Pellicano, E. (2018). ‘It’s different for girls’: gender differences in the friendships and conflict of autistic and neurotypical adolescents. Autism 23, 1119–1132. doi: 10.1177/1362361318794930

Skolverket (2014). Arbete med extra anpassningar, Särskilt Stöd och Åtgärdsprogram [work with additional adjustments, special support and action program]. Stockholm: Skolverket.

Stark, I., Liao, P., Magnusson, C., Lundberg, M., Rai, D., Lager, A., et al. (2021). Qualification for upper secondary education in individuals with autism without intellectual disability: total population study, Stockholm, Sweden. Autism 25, 1036–1046. doi: 10.1177/1362361320975929

Stenning, A., and Rosqvist, H. B. (2021). Neurodiversity studies: mapping out possibilities of a new critical paradigm. Disab. Soc. 36, 1532–1537. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2021.1919503

Taneja-Johansson, S. (2023). Whose voices are being heard? A scoping review of research on school experiences among persons with autism and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Emot. Behav. Diffic. 28, 32–51. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2023.2202441

Tierney, S., Burns, J., and Kilbey, E. (2016). Looking behind the mask: social coping strategies of girls on the autistic spectrum. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 23, 73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2015.11.013

Tomlinson, C., Bond, C., and Hebron, J. (2020). The school experiences of autistic girls and adolescents: a systematic review. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 35, 203–219. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2019.1643154

Tomlinson, C., Bond, C., and Hebron, J. (2022). The mainstream school experiences of adolescent autistic girls. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 37, 323–339. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2021.1878657

Tubío-Fungueiriño, M., Cruz, S., Sampaio, A., Carracedo, A., and Fernández-Prieto, M. (2021). Social camouflaging in females with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 51, 2190–2199. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04695-x

van Kessel, R., Walsh, S., Ruigrok, A. N. V., Holt, R., Yliherva, A., Kärnä, E., et al. (2019). Autism and the right to education in the EU: policy mapping and scoping review of Nordic countries Denmark, Finland, and Sweden. Mol. Autism. 10:44. doi: 10.1186/s13229-019-0290-4

Vivanti, G. (2020). Ask the editor: what is the most appropriate way to talk about individuals with a diagnosis of autism? J. Autism Dev. Disord. 50, 691–693. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04280-x

White, R., Barreto, M., Harrington, J., Kapp, S. K., Hayes, J., and Russell, G. (2020). Is disclosing an autism spectrum disorder in school associated with reduced stigmatization? Autism 24, 744–754. doi: 10.1177/1362361319887625

Young, H., Oreve, M. J., and Speranza, M. (2018). Clinical characteristics and problems diagnosing autism spectrum disorder in girls. Arch. Pediatr. 25, 399–403. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2018.06.008

Keywords: autism, girl, adolescence, school, first-hand perspective, mental health, wellbeing, Sweden

Citation: Josefsson H and Taneja Johansson S (2024) Adolescent autistic girls navigating their diagnosis in Swedish secondary school. Front. Educ. 9:1461054. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1461054

Edited by:

Wendi Beamish, Griffith University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Kate Simpson, Griffith University, AustraliaBeth Saggers, Queensland University of Technology, Australia

Copyright © 2024 Josefsson and Taneja Johansson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Helena Josefsson, aGVsZW5hLmpvc2Vmc3Nvbi4yQGd1LnNl

Helena Josefsson

Helena Josefsson Shruti Taneja Johansson

Shruti Taneja Johansson