- 1School of Public Health, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States

- 2Department of Preventive Medicine, Division of Public Health Practice, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, United States

In recent years, the idea that cohorts can prepare public health students for successful careers and professional development has been increasingly studied by researchers and educators. Previous literature suggests that cohorts can improve learning outcomes by providing students with mentorship and higher-order thinking assignments that model the real world and 21st century competencies—e.g. collaborative assignments, writing-intensive courses, and enrichment activities. The objective of this study is to explore the impacts of cohort-based learning on graduate student educational outcomes. The cohort structure can create a sense of collaboration and support, which in turn may maximize student success, engagement, and content retention. For the purposes of this study, MPH alumni (n = 13) who participated in a cohort model in a graduate global public health class provided insightful reflections through a qualitative survey. Responses via the survey indicated that cohort-based learning allowed students to feel more connected to the program and each other, fostering a collaborative and welcoming environment in the classroom. This was useful in developing critical thinking skills, greater learning experiences, and the ability to work in a variety of communities as reported by the participants, reflecting today's rapidly evolving society. Overall, alumni reported a positive experience with their cohort model, emphasizing more diversity in learning and thinking, personal enrichment, and professional development, which is consistent with the literature. This paper expands the knowledge on the utility and implications of cohort learning, a high-impact practice, in academic public health.

1 Introduction: background and rationale for the educational activity innovation

Educating the next generation of public health leaders requires a curriculum that models the real world (Opacich, 2019). Cohort models can strengthen learning and amplify effective instructional strategies by fostering a sense of community, allowing students to engage more deeply with course content and support one another. In graduate education, cohort-based learning has gained traction in recent years as a potential learning strategy relevant to critical thinking, academic performance, job preparedness, and personal growth (Ashford, 2013; Bista and Cox, 2014; Fifolt and Breaux, 2018; Rausch and Crawford, 2012; Winn et al., 2019). Additionally, cohorts promote collaboration, effective group work, and a variety of problem-solving skills critical in the field of public health (Opacich, 2019).

2 Underlying pedagogical principles

Literature on cohort models in higher education examines how cohort-based learning can be intellectually and academically stimulating for students while preparing them for careers beyond graduation. As detailed in the cohort literature above, cohort models also enhance other educational strategies by fostering professional development activities, collaborative work, networking, and critical thinking skills. Cohorts are unique in that they allow students to engage in ongoing academic, professional, and social journeys together. Sharing educational experiences with classmates can enhance a sense of purpose and sustain meaningful relationships. Three key pedagogical principles guide cohort-based learning and serve as a basis for further exploration.

2.1 Principle 1: promoting a shared learning community

Building a shared learning community allows students to support and teach one another via collaboration on class assignments, projects, and discussions (Bista and Cox, 2014; Ashford, 2013; Mauldin et al., 2022). Students in a cohort bring with them a diverse array of experiences, values, knowledge, skills, and perspectives, empowering students to learn from one another (Beachboard et al., 2011; Winn et al., 2019). In this way, students utilize each other as learning resources and keep the cohort motivated (Bista and Cox, 2014; Ashford, 2013; Mauldin et al., 2022).

Thus, promoting learning as a process of shared education in the classroom can allow students opportunities for critical thinking and problem solving that will be applicable to future careers in public health (Winn et al., 2019; Opacich, 2019). Since public health by nature is collaborative and requires community interaction, building these skills early in a classroom environment can set students up for later success (Opacich, 2019). Cohort models also build connections between students and faculty members, rendering them support, connections, and assistance both during their education and beyond (Fifolt and Breaux, 2018; Bista and Cox, 2014; Ashford, 2013; Shochet et al., 2019).

2.2 Principle 2: academic and intellectual enrichment

Recognizing the potential effectiveness of cohort models may aid in developing curriculum for graduate public health students in a way that elevates their academic success (Beachboard et al., 2011; Opacich, 2019). Studies on cohort-based graduate programs associate cohort models with greater educational outcomes and higher student retention rates (Ashford, 2013; Bista and Cox, 2014; Fifolt and Breaux, 2018; Rausch and Crawford, 2012; Winn et al., 2019).

2.3 Principle 3: emphasis on professional development and practicality

Cohort structures provide greater student support for professional development and networking (Ashford, 2013; Bista and Cox, 2014; Fifolt and Breaux, 2018; Rausch and Crawford, 2012; Winn et al., 2019; Shochet et al., 2019). The emphasis on practical assignments that model real-world public health activities (i.e. collaborative work, career and professional development events, mock interviews, etc) also supports the transition from a student to a working professional (Fifolt and Breaux, 2018). This has increasing significance in today's constantly changing world.

2.4 Overall purpose

This study consists of a qualitative methodology nested within a pragmatic approach, which posits that reality is constantly renegotiated and interpreted, especially in higher education and adult learning. A pragmatic approach focuses on solutions to address challenges, and this perspective applies to the research at hand which aims to both describe and improve cohort-based learning (Brown and Dueñas, 2019; Newton et al., 2020). In critical adult education, the pragmatic approach to teaching and learning emphasizes practical lessons and assignments that will be useful to students (Brown and Dueñas, 2019; Newton et al., 2020). Describing the way in which students learn through cohort models advances the literature on high-impact practices, maximizes student success, and helps to shape future curriculum design.

3 Learning objectives; pedagogical format and methodology

The goal for these programs is to develop research and critical thinking skills in students while preparing them in leadership and problem-solving for various roles; research indicates that many cohorts succeed in accomplishing these goals (Ashford, 2013; Bista and Cox, 2014; Fifolt and Breaux, 2018; Rausch and Crawford, 2012; Winn et al., 2019). This study set forward to understand the experiences of learners in cohorts and also advance the literature on how cohort-learning models can rapidly respond to the educational needs of today's university students.

The analysis of student experiences regarding the cohort model via MPH survey results utilized a pragmatic approach to reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2021). Reflexive thematic analysis places an emphasis on gathering evidence-based information to identify effective teaching strategies and to ensure that the learning experiences and perceptions of every student are recorded (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2021; Brown and Dueñas, 2019; Newton et al., 2020). This method is the optimal fit for analyzing this data as the goal is to identify and report themes within the qualitative survey responses (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2021). Since the responses are open-ended, reflexive thematic analysis supports an overall, comprehensive thematic description of the data collected (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2021).

Reflexive thematic analysis supports researchers to relate themes and patterns drawn from qualitative data to an analysis of a greater research question (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Byrne, 2022). This approach connects this study's analysis of student perceptions regarding their cohort model to the broader discussion of cohort-based learning as a useful learning strategy in graduate education (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Byrne, 2022).

All students in the Global Health concentration of an MPH program were required to participate in a cohort model; students began and graduated in the same one-year timespan. This concentration included a mandatory, three-quarter core seminar spanning the Fall, Winter, and Spring terms, along with elective classes. The cohort model was experienced in the global health major courses (n = 4) which represents 25% of the total degree; the cohort experience was practiced in other courses outside of the required ones. The survey consisted of 15 questions as outlined below and was sent to the 2022 MPH graduates in the Global Health concentration post-graduation.

3.1 Data collection

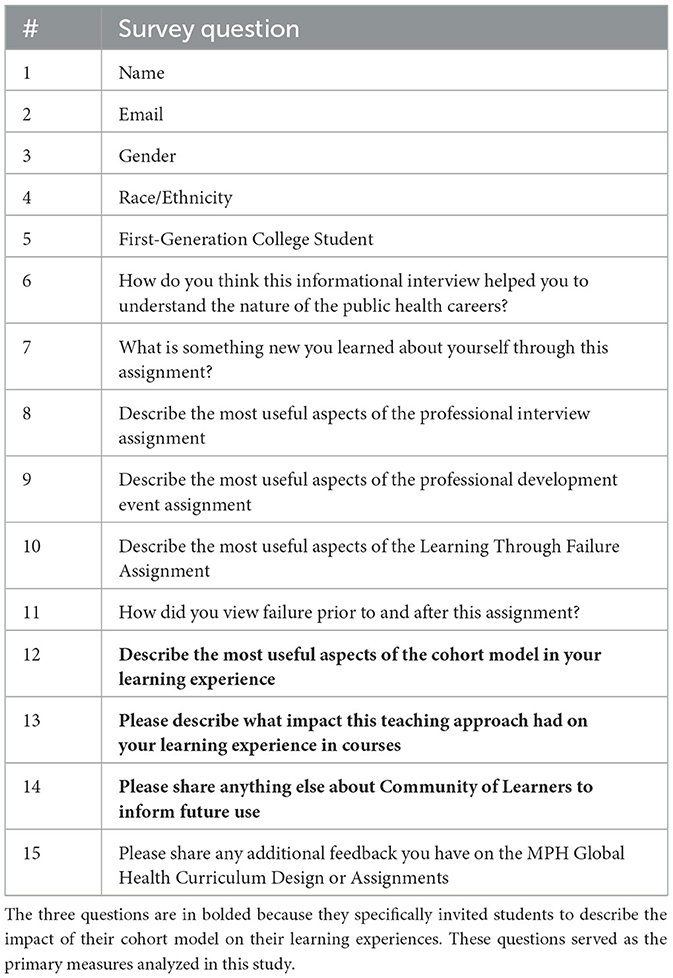

The first five questions of the survey included demographic information, such as gender, race and ethnicity, and first-generation college student status. Six questions addressed course assessments and key learnings from each assessment. Three questions invited students to describe the impact of their cohort model on their learning experiences and are the primary measures analyzed in this study. All questions were open-ended in order to describe students' experiences during the program. All 15 questions are provided in Table 1.

In the survey, participants were asked to reflect on their experiences only after they had graduated from the MPH program in order to reduce respondent bias. Asking students to complete a class survey while they are still actively enrolled in that class may sway students to respond a certain way to appeal to instructors. Compensation in the form of a $10 gift card was also provided to all participants. The review was IRB exempt as it poses no more than minimal risk to participants involved.

3.2 Data analysis

All data were reviewed by a four-person research team made up of three public health undergraduate and graduate students and one faculty member. Data analysis was guided by Braun and Clarke's six-phase process for reflexive thematic analysis: (1) data familiarization; (2) generating initial codes; (3) searching for themes; (4) reviewing themes; (5) defining and naming themes; and (6) producing the report (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

Each team member independently reviewed the survey responses and developed an initial codebook to categorize the data. Initial thematic codes were applied by identifying meaningful patterns in the responses, which were then grouped into preliminary themes. After generating themes, the team then met to collaboratively engage in thoughtful review, revision, and refinement of codes over several meetings. Team discussions ensured that themes accurately reflected the patterns in the data and aligned with the codebook. Themes were then assigned a final name and an analytical narrative was written up.

4 Results

Out of 15 responses, two records were eliminated from the data as they did not complete any additional questions beyond the demographics. Analysis and interpretation were guided by pragmatism, thus centering a commitment to making sure every MPH student's voice is heard. Therefore, every response to the cohort-based learning questions in the survey is recorded below in order to describe MPH students' thoughts and experiences.

Three survey questions are analyzed in this study: (1) describe the most useful aspects of the cohort model in your learning experience; (2) please describe what impact this teaching approach (i.e. Community of Learners) had on your learning experience in courses; and (3) please share anything else about Community of Learners to inform future use.

Recurring themes throughout student responses to these three questions found that students believed cohort-based learning was beneficial to their learning by promoting a sense of collegiality and camaraderie and aiding in professional development and networking opportunities. As a result, students found content easier to learn and class discussions more profound and intimate.

4.1 Theme 1: bonding and exposure to new perspectives led to easier learning

The cohort model led to a supportive and welcoming classroom environment, as one student described, causing greater collaboration and the sharing of interesting perspectives. Exposure to different types of thinking and learning was another useful aspect, as one student found that “placing students with similar interests/goals in the same cohort allowed us to bring our individual experiences to a common area where we were trying to develop, which exposed us to different types of thinking, speaking, and creating.”

Another student expressed that it allowed them to work with peers that were both similar to them and diverse. Building close relationships with peers allowed students to help one another learn and have in-depth discussions, as the two students outlined. Another participant communicated meaningful connections and increased enjoyment of courses as a result of cohort-based learning. However, one student expressed the desire for more intersections across cohorts.

One student found it easy to bond with classmates and the consistent, reliable community of a cohort was beneficial, but did not want all of their classes with their concentration. The next respondent enjoyed sharing a common experience and bonding with fellow classmates, as:

It was really great to have a small group walking through the same experiences with you throughout the whole program. I personally really loved my cohort, they were very supportive and encouraging, brought interesting perspectives, and great collaborators. I feel like I learned a lot from their opinions and experiences and what they brought to our class discussions.

4.2 Theme 2: increased professional development and career exploration

One student reported that the closeness of their cohort aided with professional development and networking, as the opportunities to “become closer with [the] cohort helps with future professional development and networking opportunities—also feel a circle of cohesion when working on group projects and makes content easier to learn as cohort can teach one another.”

One student positively noted that the cohort model led to an environment that resembled a public health workplace rather than a classroom, preparing them for future careers. Two students agreed, adding that this type of environment allowed them to learn more about professional experiences and careers from both peers and professors. One student cited increased job opportunities, as students could help each other with connections:

I got to build deep, trusting friendships with the people in my cohort. 2+ years later we are still good friends that connect every few months. This has also been helpful for job opportunities as we were able to help each other with connections. For example, one of my good friends within my cohort interviewed with someone that I knew from undergrad. I was able to help my friend from the cohort prepare for the interview knowing what that person from undergrad would probably be looking for.

4.3 Theme 3: promoting the concept that learning is a shared process had a positive impact on learning

Two students explained that the opportunities for open discussion in courses allowed for greater learning and a comfortable atmosphere. These are reflected in quotes such as:

I think the community of learners approach is a great way to ensure that all learners are not only included in the process, but also have a voice in the process and feel comfortable doing so. I know that I felt very comfortable with my peers, and I feel that I learned a great deal from the insights and knowledge they had to offer to this learning experience.

The Community of Learners approach allowed students to feel that everyone had a voice in the classroom and could learn from each other, as sharing ideas in the classroom was encouraged by instructors. This teaching approach kept students engaged and asking questions, and this level of support led to greater learning, collaboration, and career exploration, as reported by two students and reflected in the quote “I felt safe in this teaching approach and felt like I was supported in my education journey. I felt that it was also a very collaborative environment and I was able to really explore my passion in global public health.”

4.4 Theme 4: emphasis on critical thinking skills

One student found cohort-based learning as a useful tool for developing critical thinking skills in that “it allows one to always think critically and accept that various individual life experiences shape learning and we can all benefit from those experiences when we are open to it.” The next student expressed that lived experiences shape learning, and the sharing of these experiences is beneficial for critical thinking. One participant believed that the cohort model taught well-rounded values that lasted long past graduation.

Another praised the debate-style learning in the classroom as influential in developing critical thinking skills in the public health workforce:

I appreciated the more debate-style learning in a small number of courses. I think sometimes in public health only one approach or solution to a problem is taught in class, but being able to debate and discuss different solutions [and] different sides to a problem, was truly informative and helped foster critical thinking.

4.5 Theme 5: model should be emphasized more across the degree program

Two students did not see this approach emphasized in all of their classes and believed it should be more widespread, as the model was primarily utilized in the global health concentration courses. Another student echoed this sentiment, advising for more space for students to collaborate and complete short, in-class assignments. These students highlight the value of curricular-oriented approaches to cohort learning.

4.6 Additional data and information

Across the cohort, students were also tasked with three assignments designed for them to practice what they will be doing in the real world and enrich their learning further. In the “Professional Development Educational Event and Analysis,” students attended a professional development-oriented event with learning objectives identified beforehand and completed a critical analysis report afterwards. Students also conducted an “Informational Interview” with a professional in the field of their choice with a critical analysis written subsequently. In the “Learning Through Failure” assignment, students prepared an example of a “professional failure” related to their MPH experiences and their reflections on the process.

For these assignments, students were required to develop a list of learning objectives and questions prior to attending a professional development event and before conducting their own 1:1 professional interviews. This requirement supported students to practice preparation, independent thinking and analytic skills with faculty review and feedback. Preparation and incorporating critical feedback are skills necessary throughout the entire course of students' professional careers in public health.

Students found all three assignments valuable to their learning. Responses via the survey affirmed that the “Professional Development” and “Informational Interview” assignments gave students opportunities to develop professionally, network, practice critical thinking skills and analysis, and explore public health careers. In addition, reflecting on professional failures was seen as another opportunity for self-reflection and critical thinking, as it normalized failure as an opportunity to grow and learn.

5 Discussion on the practical implications, objectives and lessons learned

The results of the survey indicated strong student support for learning in a cohort model, including an approach that was anchored in a critical, student-centered philosophy. The student-centered approach to teaching led to a wide diversity of backgrounds, perspectives, and future career plans shared in the classroom, leading to participants feeling a deeper sense of career development and learning for all. The faculty's “Community of Learners” approach aimed to ensure that everyone could voice their views and that students felt meaningful and appreciated in the community, as some students noted, which enabled them to take ownership of their own learning and gain skills that last long past graduation. The philosophy was shared on the first day of class and was revisited each week to nurture it throughout the quarter and the series of three courses. The opportunities for open discussion in a cohesive, cohort learning environment encouraged students to dialogue and debate different solutions and sides to a particular problem, which reflects many real-world approaches to public health issues.

Cohort models which exist in in-person, hybrid, and online environments can also magnify high-impact educational practices designed to enhance and compound public health content (e.g. emphasis on collaboration, community, and enrichment activities). As demonstrated in the student survey responses and the literature, this can lead to the development of skills, patterns, and habits that can be applied in the public health arena. In working with doctoral students, Webber et al. (2022) challenged and extended previous understandings of the cohort model of learning, demonstrating that the benefits of the cohort model of learning can occur across programs and can be independent of the stage of progression in the programs in a virtual context. Future attention to cohorts in virtual and hybrid environments are needed to advance understandings for optimal, learner-centered experiences.

5.1 Recommendations

Attention to cohort learning and collaborative, authentic assessments are key recommendations of this study, inviting consideration for recognizability and applicability in other schools, programs and units offering public health courses and curriculum (Konradsen et al., 2013). Cohort-based learning is a high-impact practice which can amplify collaborative assignments and projects, writing intensive courses, professional development opportunities, and developing skills in critical thinking and problem solving. Cohort-based learning provides a framework to apply a greater focus on practical, higher-order thinking course assessments, encouraging students to rely on their fellow cohort learners. When adopted across public health curricula, the values of learning as a process of shared education are promoted, while illustrating a form of authentic assessment which models the realities of professional collaboration in 21st century society. Collaborative authentic assessments and projects which require students to work together and share learnings in dialogue to develop skills in teamwork, communication, and exposing students to a diversity of perspectives and ideas. Integrating these types of collaborative, authentic assessments through curriculum can help ensure that public health students are adequately prepared to tackle public health challenges and build a strong workforce. Finally, cohort learning does not exist in isolation. Attention to high-quality education requires both a critical review of pedagogical theories and practice and a commitment to explore new ways of approaching teaching and learning in all educational activities and decisions (Harper and Neubauer, 2021).

6 Acknowledgment of any conceptual, methodological, environmental, or material constraints

While results might not be as generalizable because of the small sample size, the results support previous literature that highlights the value of cohort learning and high impact practices. The cohort model of the global health concentration was selected because it focused explicitly on a year-long seminar course that supported student centeredness, engagement and support. Despite these limitations of the study, the findings expand the literature on cohort-learning in academic public health, advance knowledge of the experiences of graduate public health students in cohort learning and contribute to the existing literature of high-impact practices in academic public health. Together, these findings invite renewed attention to teaching methods and holistic frameworks that support student development and ensure high quality education.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the (patients/ participants OR patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin) was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

SA: Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft. YG: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. AK: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. LN: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding was provided by the Summer Internship Grant Program (SIGP), the University Research Assistant Program (URAP), and the Summer Research Opportunity Program (SROP) at Northwestern University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ashford, W. (2013). “Designing a progressive model of cohort-based programming,” in Adult Education Research Conference (St. Louis, MO).

Beachboard, M. R., Beachboard, J. C., Li, W., and Adkison, S. R. (2011). Cohorts and relatedness: self-determination theory as an explanation of how learning communities affect educational outcomes. Res. High. Educ. 52, 853–874. doi: 10.1007/s11162-011-9221-8

Bista, K., and Cox, W. D. (2014). Cohort-based doctoral programs: what we have learned over the last 18 years. Int. J. Dr. Stud. 9. doi: 10.28945/1941

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 18, 328–352. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

Brown, M. E. L., and Dueñas, A. N. (2019). A medical science educator's guide to selecting a research paradigm: building a basis for better research. Med. Sci. Educ. 30, 545–553. doi: 10.1007/s40670-019-00898-9

Byrne, D. (2022). A worked example of Braun and Clarke's approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Quant. 56, 1391–1412. doi: 10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y

Fifolt, M., and Breaux, A. P. (2018). Exploring student experiences with the cohort model in an executive EdD program in the Southeastern United States. J. Contin. High. Educ. 66, 158–169. doi: 10.1080/07377363.2018.1525518

Harper, G. W., and Neubauer, L. C. (2021). Teaching during a pandemic: a model for trauma-informed education and administration. Pedagogy Health Promot. 7, 14–24. doi: 10.1177/2373379920965596

Konradsen, H., Kirkevold, M., and Olson, K. (2013). Recognizability: a strategy for assessing external validity and for facilitating knowledge transfer in qualitative research. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 36, E66–E76. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e318290209d

Mauldin, R. L., Barros-Lane, L., Tarbet, Z., Fujimoto, K., and Narendorf, S. C. (2022). Cohort-based education and other factors related to student peer relationships: a mixed methods social network analysis. Educ. Sci. 12:205. doi: 10.3390/educsci12030205

Newton, P. M., da Silva, A., and Berry, S. (2020). The case for pragmatic evidence-based higher education: a useful way forward? Front. Educ. 5:583157. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.583157

Opacich, K. J. (2019). A cohort model and high impact practices in undergraduate public health education. Front. Public Health 7:132. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00132

Rausch, D. W., and Crawford, E. (2012). “Building the future with cohorts: communities of inquiry,” in Creating Tomorrow's Future Today, Vol. 23 (Indianapolis, IN).

Shochet, R., Fleming, A., Wagner, J., Colbert-Getz, J., Bhutiani, M., Moynahan, K., et al. (2019). Defining learning communities in undergraduate medical education: a national study. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 6. doi: 10.1177/2382120519827911

Webber, J., Hatch, S., Petrin, J., Anderson, R., Nega, A., Raudebaugh, C., et al. (2022). The impact of a virtual doctoral student networking group during COVID-19. J. Furth. High. Educ. 46, 667–679. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2021.1987401

Winn, P., Gentry, J., and Nguyen, A. (2019). Graduate student perceptions of cohort delivery and problem-based learning in online principal certification courses. Sch. Leadersh. Rev. 15. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/slr/vol15/iss1/26

Keywords: cohort-based learning, high-impact practices (HIP), higher education, public health education, professional development, practical learning

Citation: Akhtar S, Gao Y, Keshwani A and Neubauer LC (2024) Cohort-based learning to transform learning in graduate public health: key qualitative findings from a pilot study. Front. Educ. 9:1457550. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1457550

Received: 30 June 2024; Accepted: 20 November 2024;

Published: 05 December 2024.

Edited by:

Katie Darby Hein, University of Georgia, United StatesReviewed by:

Karin Joann Opacich, University of Illinois Chicago, United StatesCordelia Zinskie, Georgia Southern University, United States

Eila Burns, JAMK University of Applied Sciences, Finland

Copyright © 2024 Akhtar, Gao, Keshwani and Neubauer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sumreen Akhtar, c3Vha2h0YXJAdW1pY2guZWR1

Sumreen Akhtar

Sumreen Akhtar Yi Gao2

Yi Gao2 Leah C. Neubauer

Leah C. Neubauer