- Department de Pedagogia, Facultat de Ciències de l'Educació, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona, Spain

This Curriculum, Instruction, and Pedagogy (CIP) article outlines the pedagogical design of a course that uses Community Service Learning (CSL) to foster undergraduate students' multimodal literacy development. The article draws on a social semiotics approach to learning and communication and aligns with progressive pedagogical designs that prioritize learners' active participation. The course syllabus, methodological procedures, and assessment strategies are described. CSL serves as a means for higher education teachers to embrace civic and social responsibilities, promoting values such as solidarity and generosity through their teaching. This article examines the challenges and benefits associated with CSL and offers insights to inspire higher education teachers to adopt pedagogical designs based on creativity, solidarity, and generosity.

1 Introduction

The current global scenario requires citizens who critically exercise democracy (Landry and von Lieres, 2022), effectively communicate across differences (Shcherbyna et al., 2024), and build knowledge to promote the political, social, cultural, and educational development of their regions (Cevallos Borja et al., 2015). The education system must evolve from one that serves the industrial society to one that prepares learners to function in the knowledge society (UNESCO, 2013). Developed countries participating in the global knowledge economy have become dependent on the creation and exchange of intangible forms of production such as information, entertainment, services, and knowledge (Ruiz-González et al., 2015). Educational systems capable of producing individuals skilled in symbolic creation are strategic. A rapidly developing globalized technological society requires the new generation to be proactive, expressive, agile, self-disciplined, and creative (Singer, 2012).

However, educational reform should not be used to uphold neoliberal capitalist systems submissively. This is because not all the transformative potential in education is captured by neoliberalism, the flexible accumulation model of modern capitalism, or market demand (de Oliveira and Gallardo-Echenique, 2015). According to Kress (2011), determining how education can empower learners to live productive lives on individual and social levels is more essential than merely engaging learners to satisfy the requirements of the economic agenda. It should be noted that Kress' (2011) phrase “living productive lives” is related not to “the creation or consumption of products” but to achieving the sustainable development goals (SDGs) of “Health and Wellbeing” as part of the 2030 Agenda (Echegoyen-Sanz et al., 2024). This implies prioritizing human needs for personal fulfillment and emotional wellbeing as non-negotiable values that form the basis of educational purposes. A compelling argument exists against the “commercialization” of creative, transformative, and innovative thinking, highlighting the need for the judicious use of creativity in education to achieve the SDGs in the 2030 Agenda (Craft, 2005; Craft et al., 2008).

Knowledge societies, Community Service Learning (CSL), multimodal literacy, and social semiotics are key terms relevant to the conceptual framework of this Instruction, and Pedagogy (CIP) article. Knowledge societies prioritize and value the ability to locate, generate, process, transform, distribute, and use information to create and apply knowledge for human advancement. They need a social vision incorporating solidarity, plurality, inclusion, and participation (UNESCO, 2005). CSL is an educational experience in which students take part in a planned service project that addresses needs in the community and then reflect on the experience to learn more about the course material, develop a deeper understanding of the discipline, and strengthen their sense of civic duty and personal values (Bringle and Hatcher, 2009). Multimodal literacy is a term that comes from a pedagogical approach (Kress, 2003, 2006; Jewitt and Kress, 2003; Jewitt, 2006, 2008) that questions traditional frameworks in the face of the challenges presented by the digital age. It draws on social semiotics, a theoretical framework that examines how meaning is created and communicated through social practices, focusing on the interplay between language, visual elements, and context (Kress and Van Leeuwen, 2001). Walsh (2010, p. 213) defines multimodal literacy as “… meaning-making that occurs through the reading, viewing, understanding, responding to, producing and interacting with multimedia and digital texts.” A basic assumption of the multimodal literacy approach is that “both learning and sign-making are dynamic processes which change the resources through with the processes take place—whether as concepts in psychology or as signs in semiotics—and change those who are involved in the processes” (Kress, 2003, p. 40). How knowledge is represented, and the mode and media chosen is a crucial aspect of knowledge construction, making representation integral to meaning and learning more generally (Jewitt, 2008).

Educators embracing an awakened attitude are committed to fostering a peaceful present and future. They prioritize sustainable and equitable models of human development and recognize that learning transcends academic pursuits and encompasses spiritual and emotional growth by transforming learners' reality and interactions with others. This approach contrasts with education for reproduction, which assumes the stability of cultural and social forms (Kress, 2011). Many teaching practices rely on reproducing social and cultural forms, doing things the way they have always done, and expecting students to learn. Sullivan (2011) asserted that educators often conform to expectations by settling for monotony and perpetuating a prescriptive mentality that views learning as uniform and predictable.

Achieving social transformation requires pedagogical designs that depart from content reproduction-focused pedagogies. This CIP article presents the pedagogical design of a course that uses CSL to engage undergraduate students in multimodal literacy development. It provides information to inspire higher education teachers to embrace pedagogical designs based on creativity, solidarity, and generosity. Higher education often serves neo-liberal economic models, educating students to meet market requirements. This CIP article is a scholarly invitation to higher education teachers to adopt pedagogical designs that educate students to question and ultimately transform the capitalist market system.

2 Pedagogical framework and principles

Theories of communication initially understood communication as a closed circuit between the sender and receiver, establishing a symmetrical relationship between the one encoding the message and the one deciphering it (Charaudeau, 2006). However, from a social semiotics approach, communication depends on interpretation and not on the initial creator of the message or its elaboration (Kress, 2019). Learners engage in semiotic work when actively interpreting their educational resources. Thus, according to Kress (2019), learning is a semiotic process involving transformative commitment based on global interest.

Progressive pedagogical designs prioritize students' active participation by considering it essential for effective learning (de Oliveira et al., 2015). Students can autonomously search for, select, and analyze information when guided and supported. Furthermore, they transition from passive consumers to active knowledge producers by sharing insights derived from interpretation processes through various modalities, such as verbal language, sound, and images (de Oliveira et al., 2009). To achieve this, higher education teachers must develop pedagogical designs that challenge students and provide them with contemporary analog and digital tools (de Oliveira and Gallardo-Echenique, 2015).

It is essential to foster students' multimodal development and enable their participation in knowledge societies, thereby mitigating the risk of marginalization. Archer (2014) considers a multimodal approach to have the potential to make classrooms more democratic and inclusive, thereby enabling marginalized students' histories, identities, languages, and discourses to be visible. Only by intentionally retreating from the excesses of a highly regulated, performance-based audit culture can emphasize creativity in higher education be promoted daily. In this regard, she argued that ideologically engaged multimodal creative learning is crucial in forming wise futures that ensure just and sustainable models of human growth.

When considering the role of creativity in education, it is relevant to consider that there are different rhetorics of creativity (Banaji, 2011), which fall into two paradigms: a paradigm of competition or a paradigm of collaboration (de Oliveira and Gallardo-Echenique, 2015). In a paradigm of competition, creativity is pivotal in economic production and enterprise. The socio-economic circumstances behind the educational interest in creativity receive special relevance (Shaheen, 2010). In this tradition, investment in creativity directly addresses the neoliberal need to restructure capital to generate new products and exploit intellectual property possibilities. In a collaboration paradigm, researchers and educators deliberately approach education matters from a social and cultural perspective, satisfying the demands that place human needs for personal fulfillment and emotional wellbeing as non-negotiable values based on educational purposes.

The literature urges higher education teachers to promote creative semiotic work that opens alternatives to reinforcing capitalist neo-liberal structures. Tseris and Jamieson (2024) drew on creative pedagogies to support critical thinking, openness to learning, and engagement with multiple forms of knowledge in a mental health social work curriculum. They reported that students could embody analysis of power and knowledge with heightened confidence and enthusiasm for exploring multiple paradigms in mental health and engaging with more just and expansive possibilities in their future practice. Similarly, Mendelowitz and Govender (2024) explored the nuances of critical, imaginative, and affective entanglements by examining students' decisions to redesign advertisements and theorize their process. They found that students engaged within various combinations of creative-affective, critical-affective, and critical-creative moves across different assignments that required analysis and imagination, evoked emotions, and made a significant contribution toward doing literacies in transformative ways. de los Ríos (2022) explored a curricular unit that allowed young people to use new media technologies to tell important stories about themselves and their social worlds during heightened anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States. They demonstrated how Latinx young people contest racist narratives, reclaim their identity, and author new spaces for solidarity. In the learning experience, the students utilized podcasts to promote creativity and self-expression and connect personal experiences to broader pressing discourses about immigration, language, racialization processes, and resistance.

When planning and conducting pedagogical interventions, higher education teachers decide from various alternatives: they determine the content, presentation methods, activities, and learners' roles. Each decision reflects their identity and worldview. Additionally, these decisions provide students with cues for interpreting the information, although they do not dictate their responses. Students, too, actively select what they want to learn from the options provided, even if they choose not to participate. Their choices vary depending on their interests, maturity, and prior knowledge. Therefore, teaching and learning are design processes that inform learners' choices and adapt to their interests.

3 Social engagement

Multimodal composition pedagogy poses a paradigm shift in higher education (Olivier, 2021). This new pedagogy is warranted—grounded in the value of generosity rather than competitiveness (de Oliveira et al., 2015, 2016). From a methodological point of view, this new instruction paradigm promotes a student-centered model of teaching and learning, explores the potential of interactivity and the disjunction of time and space, and enriches the learning experience with different modes (de Oliveira et al., 2009). Social relations are established among teachers and students and knowledge is restructured based on solidarity. Co-creation practices become an opportunity space to re-image higher education, question the status quo, and envisage a different kind of society (Wallin, 2023).

Students perceive community and solidarity pedagogies as innovative and value approaches that foster community-centered learning, interdisciplinary methods, and experiential education for tackling broader societal and economic challenges (Ciolan and Manasia, 2024). Freire (2008) states that educators must commit to the world by fostering humanization, responsibility toward others, and engagement in history. Solidarity and generosity underpin a pedagogy dedicated to social transformation and liberation from systems of domination. In this regard, Kioupkiolis (2023), Muñoz et al. (2022), Frankenberger et al. (2018), and Boucher (2016) illustrate how solidarity and generosity have been successfully integrated into educational practices, reinforcing a paradigm of transformative learning practices. Padrós-Cuxart et al. (2024) explored how educational transformative practices based on friendships, support, and solidarity can prove successful in settings beyond traditional educational environments, helping individuals to establish positive relationships that help them face challenges.

Freire (2008, p. 79) stated, “No one educates anyone, no one educates oneself: men educate each other mediated by the world.” Similarly, Kress (2019) emphasized engagement as integral to the definition of learning, describing learning as a transformative commitment driven by individuals' focus and principles, which leads to the evolution of their semiotic/conceptual resources.

Freire (2002) argued that educators are pivotal agents of change. However, he emphasized that they must approach their actions with love. This facet of change is often rejected by proponents of change solely for the pursuit of wealth. According to Freire, love is the key to authentic change, manifested through a commitment to freedom achieved through dialogue and the transformation of all individuals subject to various forms of domination. He defined “love” as an essential education component, stating that “there is no education without love. Love involves fighting against selfishness. He who is not capable of loving unfinished beings cannot educate. There is no imposed education, just as there is no imposed love. He who does not love does not understand others; He doesn't respect them” (Freire, 2002, p. 8).

4 Learning environment and objectives

The activities outlined within the course framework presented in this CIP article affect the development of three transversal skills (CT) of the Rovira i Virgili University skills map:

CT1. Efficiently managing information and knowledge through the efficient use of ICT.

CT2. Critically, creatively, and innovatively solving problems within the field of study.

CT3. Demonstrating responsibility, initiative, and the ability to work independently and as a team.

This study aims to describe Multimodal Literacy, a component of the “Communicative Skills” course taught in the 1st year of education degrees at the Faculty of Educational Sciences and Psychology of the Universitat Rovira i Virgili. It carries six European credits and serves as the first module of the 12-credit course. The degrees offered include Early Childhood Education, Primary Education, Double Degree in Early Childhood and Primary Education, Social Education, and Pedagogy. This module is structured with two theoretical and four practical credits, spread over 15 sessions within a 4-month timeframe. These sessions encompass various activities, including an introductory session, syllabus development sessions, group project presentations, and a final reflection and closure session. The course syllabus comprises five topics:

i) Digital identity and intellectual property.

ii) Multimodal literacy.

iii) New learning methods in the digital age.

iv) Assertive communication.

v) Safe Internet practices and cyberbullying.

5 Theoretical sessions

The flipped-class methodology was used for theoretical sessions. On the virtual campus, students were assigned readings to complete at home. Face-to-face classes were dedicated to debating and exchanging ideas. The students took multiple-choice exams as a task associated with the theoretical sessions. These exams are designed to assess the reading and understanding of the mandatory texts and are conducted at the end of each of the five items on the syllabus.

6 Practical sessions

In practical classes, students performed group and individual activities that challenged them to translate their theoretical reflections into tangible outputs. Individually, students created an e-portfolio. In groups, they developed a project based on CSL. Students receive weekly work scripts through the virtual classroom forum, enhancing their autonomy as they navigate learning spaces like the University Learning and Research Resource Center. Many tasks require a quiet environment for completion, which the center provides.

7 E-portfolios

E-portfolios are digital collections of student work that showcase learning achievements, skills, and reflections, often used for assessment purposes. They promote semiotic work that favors transformative pedagogical approaches, allowing students to become content producers and not mere information consumers. They provide an appropriate platform for integrative learning that allows students to visualize the relationships between various concepts learned throughout the course and beyond (Thomas, 1998; Syzdykova et al., 2021). E-portfolios also provide opportunities for students to reflect on their learning experiences and assess how these experiences are linked to everyday practice (Alzouebi, 2020).

In their e-portfolios, the participating students must create four entries through guided reflections: (1) who I am, (2) who I would like to be, (3) my professional future, and (4) what I learned from the CSL experience. The E-portfolio is evaluated through co-evaluation, which is defined as students measuring the learning achievement of their classmates. This is part of the formative assessment in the teaching-learning process, as it regulates and improves students' learning. Three classmates evaluate each student and the e-portfolios of three classmates, with 85% of their grades corresponding to the average of the evaluations received by their peers and 15% corresponding to their grades as evaluators.

8 Community service learning project

CSL provides a dynamic source of innovative instruction by imbuing university students with responsibilities from a fresh perspective (Smith et al., 2013). As students' skills are used to benefit society, these duties take on a social role in addition to serving their own educational goals. Tijsma et al.'s (2020) analysis of the literature highlighted three essential steps in the implementation of CSL: (1) aligning course objectives and formats, (2) establishing a relationship with the community partner, and (3) defining a reflection and evaluation strategy.

The Universitat Rovira i Virgili maintains a catalog of CSL projects and entities. A “Social Project Market” is promoted by the university Social Commitment Office. Both activities allow the establishment of collaborations between university teaching staff and non-profit organizations to promote CSL projects within the framework of university courses.

In the framework of the Multimodal Literacy CSL project, students work in groups of four or five to create, in the order of collaborating with non-profit organizations, four communicative pieces:

• Infographic: The digital tools used are free online tools, such as Canva and Genially.

• Podcast: The digital tool used is Podcastle or another app that offers free access.

• Video: The software used is Shotcut, HitFilm, Clipchamp, or others with free access.

• Comic: The tool used is Pixton.

To perform these tasks, groups of students receive continuous and personalized guidance from the teacher of the Multimodal Literacy module and personalized tutoring from collaborating non-profit organizations. In the 2022–2023 academic year, the project involved six entities and 107 students, while in the 2023–2024 academic year, it involved 19 entities and 182 students. Service-learning projects must be validated at the university by the Academic and Teaching Policy Commission.

The non-profit organizations participating in the CSL project during the 2023–2024 academic year are listed in Table 1, along with a short description of their action areas.

Table 1. Non-profit organizations participating in the multimodal literacy module CSL project during the 2023–2024 academic year.

The learning outcomes pursued in the Multimodal Literacy module are as follows:

• Conceptualize the process of literacy in a more complex way.

• Develop digital competence.

• Apply critical, logical, and creative thinking to demonstrate innovation capacity.

• Work independently with responsibility and initiative.

• Work in a cooperative team and share responsibilities.

• Advanced use of information and communication technology.

• Manage information and knowledge.

• Express oneself correctly and write in the official language of the university.

Assessment is done through hetero-evaluation (evaluation by the instructor) and co-evaluation strategies (peer evaluation). Students' learning outputs are evaluated using two hetero-evaluation and one co-evaluation strategy. The hetero-evaluation tasks are:

• Five multiple-choice examinations account for 30% of the course grade. At the end of each topic of the course syllabus, students take a multiple-choice exam to check their reading and understanding of the theoretical reference readings.

• The CSL Project accounts for 40% of the course grades. Groups of four or five students use any free online platform for web development; they create a webpage displaying the communication pieces created for the non-profit organization with which they have collaborated on their project.

Finally, the e-portfolios account for 30% of the course grade and are assessed using the co-valuation strategy described in Section 7. The Moodle “workshop” tool is used to assign random e-portfolios for evaluation and automatic calculation of qualifications. A rubric is used to guide the peer evaluation, which allows for generating a quantitative grade to which students can add qualitative comments to offer more information to their evaluated peers. The rubric is shared with the students at the beginning of the course to make them aware of the evaluation criteria and strategies.

9 Results to date

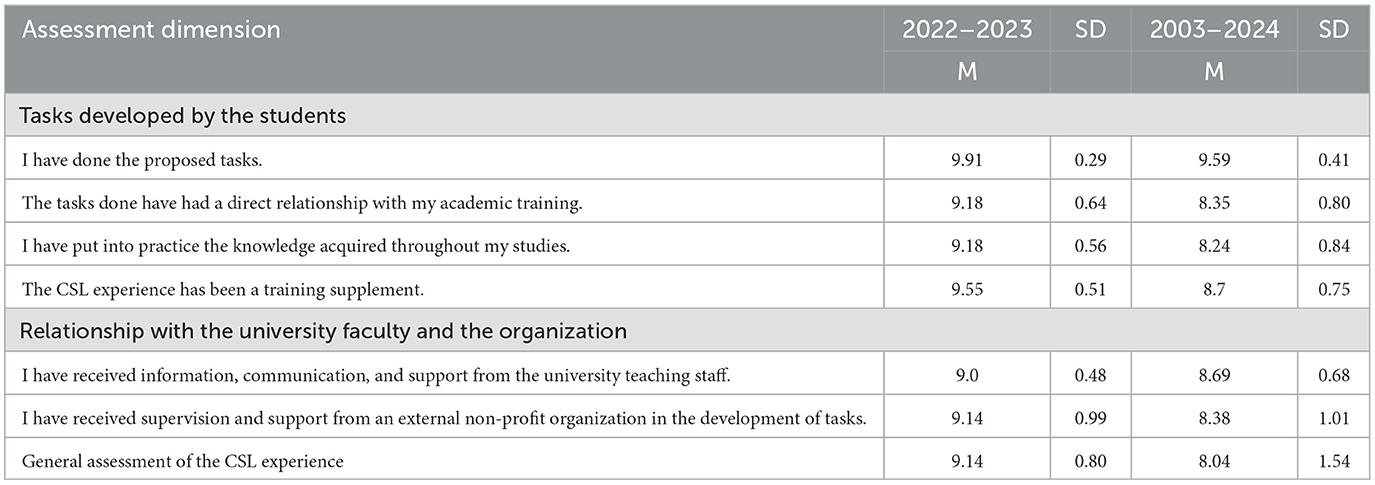

The Social Commitment Office of the Universitat Rovira i Virgili uses a survey to assess the validated CSL experiences. In the 2022–2023 academic year, ~107 students participated in the Multimodal Literacy Project, yielding 84 responses. During the 2023–2024 academic year, ~182 students participated in the project, resulting in 145 responses. The groups comprised first-year students aged 18–21 years. In 2022–2023, the average overall satisfaction with the Multimodal Literacy course was 9.14, with a deviation of 0.8 (Cronbach's Alpha: 0.61; Table 2). However, despite efforts to expand the number of entities for personalized attention, the average overall satisfaction dropped to 8.04 with a deviation of 1.54 in the 2023–2024 academic year. Communication challenges and differences in work rhythms with some non-profit organizations posed difficulties for some students. Consequently, their experiences varied, with more negative evaluations in some cases. The increase in participating non-profit organizations also heightened the potential for unpredictable situations, which created tension in adhering to the academic calendar.

The satisfaction survey ends with a non-mandatory open-ended question where the participants can make clarifications, observations, or suggestions. Most responses in this field positively assessed the 2022–2023 and 2023–2024 academic year teaching experiences, highlighting different aspects of its implementation. The students highlighted a wide range of topics, including how much they enjoyed the course methodology, how much it enriched their personal and professional lives, and how much they felt their communication and digital abilities had improved. Consistent with the findings of Bringle and Hatcher (2000) and Ribeiro et al. (2023), CSL exhibited the potential to promote students' holistic development beyond academic content and integrate the development of specific and generic skills while students provide a service to the community. Drawing on a socio-cognitive perspective of critical discourse analysis, five semantic macrostructures can be elicited from the student responses: (i) Satisfaction and Enjoyment; (ii) Personal and Professional Growth; (iii) Challenges and Difficulties; (iv) Critical Awareness and Social Responsibility; and (v) Methodological Effectiveness. Semantic macro structures refer to the overall, global meanings of discourse: “They are mostly intentional and consciously controlled by the speaker; they embody the subjectively most important information of a discourse, express the ‘overall' content of mental models of events (…)” (Van Dijk, 2009, p. 68). Below are examples of observations that highlight students' subjective experiences. The original quotations were either in Catalan or Spanish; a translation is provided.

9.1 Satisfaction and enjoyment

Many students expressed high satisfaction with the course methodology and the overall experience, indicating that the course was enjoyable and engaging. The students highlighted the dynamic nature of the learning process and the enjoyment derived from collaboration with non-profit organizations.

“This experience has been able to enhance my ability with digital and editing platforms in a very positive way. I have learned to make comics, to create a web page and its sections... It has been an enriching experience in general even though the entity has not been able to keep up with everything we were doing, I really enjoyed carrying out this work.” (Academic year 2023–2024)

“I value the experience very positively, since knowledge has been acquired in a very dynamic way. The learning has been very enriching and being able to collaborate with an entity that can use your work is a source of pride.” (Academic year 2022–2023)

“It's an activity that is very good because it leaves the traditional and is dynamic. We learn to work in a team, new technological resources, and new knowledge.” (Academic year 2023–2024)

“I think that the CSL experience has been a very pleasant and profitable opportunity to train and learn about a very unknown and invisible problem. It has been a very original way of learning, using the students' creativity and motivating them day after day and task after task. I would have liked this experience to have been longer and to have had more time to get to know the problem and the organization in depth. However, I think it has served me well for my professional future.” (Academic year 2023–2024)

9.2 Personal and professional growth

Students noted significant personal enrichment and skills development beyond academic content, such as digital competencies and teamwork. The following quotes are evidence of students' reflections on how the course impacted their views on life and their professional aspirations.

“It has been a very good experience with which I have learned many aspects of life and how to see life.” (Academic year 2022–2023)

“It was a very enriching task. We had contact with another entity all on our own, with the support of teaching professionals from the URV (Universitat Rovira i Virgili) and the educational complex, we carried out work to promote the cultural heritage of the city from Tarragona.” (Academic year 2023–2024)

“An experience to awaken consciences.” (Academic year 2023–2024)

9.3 Challenges and difficulties

Some students reported challenges related to communication and coordination with non-profit organizations, which affected their experiences. This semantic macro structure highlights the complexities of managing CSL projects and the impact of these challenges on student satisfaction. An aspect that hindered students' experience was the need for improved communication with non-profit organizations. These organizations typically display enthusiasm for a project when it is presented to them a few months before its start date. However, when it is time for students to seek answers from these organizations, challenges may arise. Most associations lack professionalization, which indicates that volunteers tend to work during their free time. Meeting students' support needs could prove challenging as the project progresses. This is evidenced by the quotes below:

“I really liked the experience, we had problems when receiving information from the entity but even so, I have learned a lot from the activity and I think it is a very complete and creative way to learn the concepts.” (Academic year 2023–2024)

“Very enriching experience, although communication with the organization has been difficult at times.” (Academic year 2022–2023)

“The participation and support from the external entity have been somewhat missed, but I understand that these are complicated dates, and they have not been able to participate as we expected.” (Academic year 2022–2023)

“The little support from the entity has made the task difficult.” (Academic year 2023–2024)

Owing to the additional complexity of the ongoing entity evaluations, students occasionally felt that the time allotted to the activities was insufficient.

“More time to carry out this work since it entails obtaining feedback from the entity that in many cases was not available.” (Academic year 2022–2023)

9.4 Critical awareness and social responsibility

Several responses indicated that the course fostered a critical understanding of social issues, particularly through engagement with specific communities, such as the Saharawi people. This semantic structure highlights the role of the course in promoting civic engagement and social awareness among students.

“I am very grateful to the subject of Communication Skills for allowing us to get closer, discover and work with ‘Una Finestra la Món' (A Window on the World). We have been able to learn about the unjust situation that the Saharawi people have been living in for years and we have been able to help the association through the creation of various materials. In summary, it has been a very enriching experience that has allowed us to have a more critical view of the world.” (Academic year 2022–2023)

“It was a different experience, since we had to work with an entity. The entity we chose was very interesting, since I learned a lot and was able to listen to the experience of a volunteer, which called my attention a lot.” (Academic year 2022–2023)

9.5 Methodological effectiveness

The students' responses suggest that the teaching methods employed effectively facilitated learning. The following quotes indicate that the pedagogical strategies contributed to students' positive experiences and learning outcomes.

“It has been a very positive experience and has contributed significantly to my academic training, as it has brought us a little closer to what our work could be in the future.” (Academic year 2022–2023)

“The APS experience seemed very interesting and important to me, since, thanks to this project, I was able to learn more about the foundation with which we collaborated, very related to my future work, and we were able to see how they work and with what values they do it. In addition, we learned in a dynamic and fun way by performing the various communicative pieces.” (Academic year 2023–2024)

10 Discussion and lessons learned

As described in this study, the teaching experience is complex, requiring considerable labor and preparation hours. These complexities increase with the additional planning, management, coordination, and adaptability needed for CSL, simultaneously involving large groups and numerous non-profit organizations. Institutional support is essential for successfully implementing, assessing, and certifying CSL. This support must be combined with a strong commitment to advancing innovative and significant teaching methods in higher education, a passion for teaching, and a dedication to students. This does not refer to romantic love, but rather, as Freire (2008) conceptualized, love is a commitment to freedom through dialogue to transform the reality of those under some form of domination. In this context, CSL enables students to commit to humanizing individuals and taking responsibility for humanity and history. In this project, the students were invited to humanize themselves by examining the world views of the participating non-profit organizations:

• The social cohesion activities promoted by Atzavara-arrels;

• The comprehensive psychosocial care for children and adolescents with cancer and their families offered by Afanoc;

• The dissemination activities of the cause of the Saharawi people, the history and present of oppression carried out by Una Finestra al Món;

• The support, active and individualized listening to people who are unwell implemented by Ocell de Foc and la Bastida;

• The awareness projects around the human need to defend the environment promoted by Ecocolmena and to integrate ourselves in it in a healthy way promoted by Ennatura't;

• The work for the social and labor integration of people with disabilities and the socio-labor insertion of people in a situation of social vulnerability laid by Fundació Onada, El Far, and Fundació Topromi;

• The projects for the promotion of an integrated and inclusive society with special attention to people and sectors with greater risk of exclusion by offered Esplai Blanquerna;

• The activities of attention to persons at risk of suicide, their relatives, and the support to bereavement by suicide extended by Papageno, APSAS, and ACPS;

• The pedagogical projects of Center de Noves Oportunitats and the Complex Education;

• The clean and safe urban mobility proposal promoted by Cooperativa l'Escamot;

• The guidance and support activities for families with high abilities offered by Athena;

• Cooperativa Fet Tàrreco implemented the feminist business model.

As can be seen, the values of the participating non-profit organizations reflect in practice the solidarity and generosity that inform the theoretical framework of the pedagogical design presented here. These are the values of pedagogical approaches committed to social transformation and liberation from domination situations. The non-profit organizations keep continuous and individualized contact with the groups. They instruct the students about the importance of their projects while presenting them with different forms and strategies of social resistance and improvement. Additionally, its critical perspective toward the communicative pieces created by the students offers an assessment by real end users of the students' semiotic work, resulting in a much richer learning experience. In some cases, non-profit organizations require students to make frequent changes in their communication pieces to transmit their projects and values more accurately. In these cases, the students revised their work until they reached a satisfactory result for both parties. This demanded resilience from the students and became an opportunity to accept constructive criticism proactively and with greater humility.

Apart from my traditional role as a university professor, which I perform in theoretical and e-portfolio activities, I have become a mediator in the CSL more closely related activities. On the one hand, I must correctly communicate to the non-profit organizations the expectations they may have of 1st-year students enrolled in the Faculty of Education. On the other hand, I convey to students that these are users who come from the real world, not the protected environment of our classroom. Understanding and meeting their needs requires communication skills that far transcend those related to technology management, even though these are necessary.

Notably, this teaching experience demonstrated that it is expedient for each non-profit organization to work with one or, at most, two groups of students. Furthermore, considering unforeseen events, it must be ensured that the participating non-profit organizations can respond to the demands of the students whenever possible. An assignment sheet was created for the 2023–2024 academic year to guide students and reduce their demands from these organizations effectively. This sheet required each non-profit organization to explain: (1) what message it wants each of the communication pieces to transmit, (2) the target audience of the pieces, (3) contacts (emails or telephone numbers) of informants or interviewees, if any, and (4) reference documents needed for the task. While this assignment form adds an extra task for non-profits before the project commences, it effectively reduces student demands during the project.

However, it is crucial to balance between prior planning and allowing students to be creative. Excessive guidance can stifle creativity. In this video, for example, a group of students worked with AFANOC, an association supporting families of children with cancer, and staged a dispute between cancer through self-composed music and dance. The semiotic work in this piece transcends digital skills, garnering empathy from the non-profit organization and posing a deep sensitivity in communicating its message. The cap seen at the end of the video is used as a fundraiser by the entity to offer accommodation, among other things, to families who come from centers far from the hospitals specializing in pediatric cancer. These hospitals are located in large cities and are very expensive to rent. In the particular case of this video, the non-profit organization made a very open request to the students: “Present AFANOC. Create awareness around pediatric cancer. Create involvement with AFANOC.” The group of students united individual capacities not usually evoked in a traditional approach. The students examined their capabilities, feelings, and knowledge to determine how to fulfill the non-profit organization's request. In the video, the students transmitted their newly developed vision of the relationship between the effects of cancer, a family facing pediatric cancer, and the non-profit organization that offers support to the family.

While the case above details a success, some students may not know how to investigate their abilities and sometimes do not see the reward in doing so. In these cases, a more elaborate task orientation and individualized tutoring by the teacher can help develop the work. However, it is necessary to acknowledge that there are no formulas to achieve the balance between planning and openness that favors creativity. Very creative works are not the norm but rather the exception. However, I argue that it is important to create the conditions so that they can happen because of the learning experience they entail. In the present experience, telling students explicitly and repeatedly that they are expected to be innovative and creative informs them that this is an important aspect of their work, but it does not ensure that all groups will make the effort, and many will fail to do it successfully. Students are told that the non-profit organization's demands are proposals and that the non-profits will listen to them if they have creative counter-proposals. While students need guidelines to follow the tasks and calendar, the CSL experience, as described in this study, requires flexible spaces and times to ensure that the organization does not hinder creativity.

In practice, this flexibility translates into presenting both students and non-profit organizations with a work calendar permissive with each of the four partial work deliveries but very strict with the deadline of the final format delivery that consisted of a webpage presenting all the communicative pieces created by each group of students. This poses challenges for teaching management. During the 2023–2024 academic year, ~182 students participated in the project. Thirty-eight groups were working with 19 non-profit organizations. This involved delivering 152 communication pieces, each reviewed once, twice, and sometimes many times by the non-profit organization until the final result was satisfied. Being strict with a delivery date for each communicative piece was incompatible with the coordination and creation challenges students faced in the proposed tasks. To overcome these difficulties, from the beginning of the course, the students had at their disposal the ideal calendar for the partial deliveries of the communicative pieces and the irrevocable deadline for the presentation of the groups. The day of the exhibition was the deadline for the final delivery of all communication pieces in their final format. In groups of up to 20 students, the procedures described here only mean flexibility and extra patience from the higher education teacher. When we talk about groups with up to 100 students, as is the case of the degrees of Social Education and Pedagogy described in this CIP, the challenges are exponential, always in direct proportion to the satisfaction experienced with their results on personal and academic levels.

The broader implications of CSL on students' personal, academic, and professional development are well-documented in disciplines as diverse as medicine (Nauhria et al., 2021), nurse education (Marcilla-Toribio et al., 2022), Computer and Information Science (Yamamoto et al., 2023), music education (Chiva-Bartoll et al., 2019), and teacher education (Khan and VanWynsberghe, 2020). In line with previous studies, the project described here shows that students noted significant personal enrichment and the development of skills beyond academic content, reported experiencing broader life views and impact on their professional aspirations, expressed high levels of satisfaction with the methodology, and developed a critical understanding of social issues. Fluid communication among all parts and calendar flexibility were the main challenges identified in the project. I hope this CIP will encourage the academic community to engage in pedagogical designs that re-image higher education, question the status quo, and envisage a society that puts creativity, solidarity, and generosity at the heart of the learning process.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

JMO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research has received financial support from the Catalan Agency for Management of University and Research Grants (AGAUR) for projects with social impact—IMPACTE (2023 IMPAC 00005).

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the following non-profit organizations for their participation in this CSL project in the academic year 2022–2023: Atzavara-arrels, Afanoc, Una Finestra al Món, Esplai Blanquerna, Athena, and Servei De Promoció De La Salut Tarragona. The author would like to thank the following non-profit organizations for their participation in this CSL project in the academic year 2023–2024: Atzavara-Arrels, Afanoc, Una Finestra al Món, Ocell de Foc, Ennatura't, Esplai Blanquerna, Fundació Topromi, Onada Foundation, Center De Noves Oportunitats, Papageno, APSAS, ACPS, Ecocolmena, Complex Educatiu, L'Escamot Cooperative, La Bastida, Athena, Cooperative El Far, and Cooperativa Fet Tàrreco. The author would also like to thank the following non-profit organizations for participating in this CSL project in the academic year 2024–2025: Afanoc, Ennatura't, Esplai Blanquerna, Center De Noves Oportunitats, Papageno, Ecocolmena, Complex Educatiu, L'Escamot Cooperative, Athena, Fundació Onada, La Niña Amarilla, Pla D'entorn Educatiu El Vendrell, Ecologistes De Catalunya, Associació Asperger-Tea Del Camp De Tarragona, Nacer En Casa, Club Social La Muralla, Associació Promoció I Desenvolupament Social, Associació Families Abusos Sexuals Infantils Tarragona, Associació De Familiars De Persones Amb Alzheimer De Tarragona, and Federació De La Xarxa De Cooperació Del Sud De Catalunya. Their generosity and solidarity make this CSL possible and this world a better place to live, learn, and love.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alzouebi, K. (2020). Electronic portfolio development and narrative reflections in higher education: part and parcel of the culture? Educ. Inf. Technol. 25, 997–1011. doi: 10.1007/s10639-019-09992-2

Archer, A. (2014). Multimodal pedagogies and access to higher education. SAJHE 28, 1123–1131. doi: 10.20853/28-3-368

Banaji, S. (2011). “Mapping the rhetorics of creativity,” in The Routledge International Handbook of Creative Learning, eds. J. Sefton-Green, P. Thomson, K. Jones, and L. Bresler (London/New York: Routledge), 36–44.

Boucher, M. L. (2016). More than an ally: a successful white teacher who builds solidarity with his African American students. Urb. Educ. 51, 82–107. doi: 10.1177/0042085914542982

Bringle, R. G., and Hatcher, J. A. (2000). Institutionalization of service learning in higher education. J. High Educ. 71, 273–290. doi: 10.1080/00221546.2000.11780823

Bringle, R. G., and Hatcher, J. A. (2009). Innovative practices in service-learning and curricular engagement. New direct. High. Educ. 147, 37–46. doi: 10.1002/he.356

Cevallos Borja, F. J., Corrales Fonseca, E., López Zapata, F., Hoyos López, A., Mejìa Valencia, M., Hoyos Jaramillo, B., et al. (2015). Alfabetización: una ruta de aprendizaje multimodal para toda la vida: consideraciones sobre las prácticas de lectura y escritura para el ejercicio ciudadano en un contexto global e intercomunicado. Centro Regional Para El Fomento Del Libro. EN América Latina y el Caribe, CERLALC-Unesco. Available at: https://cerlalc.org/wp-content/uploads/publicaciones/olb/PUBLICACIONES_OLB%20Alfabetizacion-una-ruta-de-aprendizaje-multimodal-para-toda-la-vida_v1_010114.pdf (accessed August 29, 2024].

Charaudeau, P. (2006). El contrato de comunicación en una perspectiva lingüística: normas psicosociales y normas discursivas. Opción 22, 38–54. Available at: https://www.redalyc.org/comocitar.oa?id=31004904

Chiva-Bartoll, Ò., Salvador-García, C., Ferrando-Felix, S., and Cabedo-Mas, A. (2019). Aprendizaje-servicio en educación musical: revisión de la literatura y recomendaciones para la práctica. Rev. Electrón. Complut. Investig. Educ. Music 16, 57–74. doi: 10.5209/reciem.62409

Ciolan, L., and Manasia, L. (2024). Picturing innovation in higher education: a photovoice study of innovative pedagogies. Act. Learn. High Educ. 2024:14697874241245350. doi: 10.1177/14697874241245350

Craft, A., Gardner, H., and Claxton, G. (2008). Creativity, Wisdom and Trusteeship: Exploring the Role of Education. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

de los Ríos, C. V. (2022). Translingual youth podcasts as acoustic allies: writing and negotiating identities at the intersection of literacies, language and racialization. J. Lang. Identity Educ. 21, 378–392. doi: 10.1080/15348458.2020.1795865

de Oliveira, J. M., Baptista, P. R. T., and Arão, L. (2016). Ensinar e aprender nas novas condições da era digital: desafios para contextos de leitura e escrita transformados. Rev. Ciènc Educ. 1, 29–39. doi: 10.17345/ute.2016.1.975

de Oliveira, J. M., Cervera, M. G., and Martí, M. C. (2009). “Learning as representation and representation as learning: a theoretical framework for teacher knowledge in the digital age,” in Proceedings of World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications (Chesapeake, VA: AACE), 2646–2653.

de Oliveira, J. M., and Gallardo-Echenique, E. E. (2015). Early childhood student teachers' observation and experimentation of creative practices as a design processes. J. New Approach. Educ. Res. 4, 77–83. doi: 10.7821/naer.2015.4.122

de Oliveira, J. M., Henriksen, D., Castañeda Quintero, L., Marimon, M., Barberà, E., Monereo Font, C., et al. (2015). The educational landscape of the digital age: communication practices pushing (us) forward. Rev. Univ. Soc. Conoc. 12, 14–29. doi: 10.7238/rusc.v12i2.2440

Echegoyen-Sanz, Y., Morote, Á., and Martín-Ezpeleta, A. (2024). Transdisciplinary education for sustainability. Creativity and awareness in teacher training. Front. Educ. 8:1327641. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1327641

Frankenberger, F., Anastacio, M., and Tortato, U. (2018). “Education for solidarity: a case study at PUCPR,” in Handbook of Lifelong Learning for Sustainable Development, eds. W. L. Filho, M. Mifsud, and P. Pace (New York, NY: Springer), 183–195.

Freire, P. (2002). Educación y cambio. 5a edición. Buenos Aires. Available at: http://ibdigital.uib.es/greenstone/collect/cd2/index/assoc/az0009.dir/az0009.pdf (accessed March 25, 2020).

Jewitt, C. (2006). Technology, Literacy and Learning: A Multimodal Approach. New York, NY: Routledge.

Jewitt, C. (2008). Multimodality and literacy in school classrooms. Rev. Res. Educ. 32, 241–267. doi: 10.3102/0091732X07310586

Khan, S. A., and VanWynsberghe, R. (2020). A synthesis of the research on community service learning in preservice science teacher education. Front. Educ. 5:45. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00045

Kioupkiolis, A. (2023). Common education in schools. Gauging potentials for democratic transformation: a case study from Greece. Front. Educ. 8:1209816. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1209816

Kress, G. (2006). “Meaning, learning and representation in a social semiotic approach to multimodal communication,” in Advances in Language and Education, eds. A. McCabe, M. O'Donnell, and R. Whittaker (London: Continuum), 15–39.

Kress, G. (2011). “English for an era of instability: aesthetics, ethics, creativity and design,” in The Routledge International Handbook of Creative Learning, eds. J. Sefton-Green, P. Thomson, K. Jones, and L. Bresler (London: Routledge), 211–216.

Kress, G. (2019). Pedagogy as design: a social semiotic approach to learning as communication. Rev. Ciènc Educ. 2019, 23–27. doi: 10.17345/ute.2018.2488

Kress, G., and Van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication. London: Routledge.

Landry, J., and von Lieres, B. (2022). Strengthening democracy through knowledge mobilization: participedia - a citizen-led global platform for transformative and democratic learning. J. Transform. Educ. 20, 206–225. doi: 10.1177/15413446221103191

Marcilla-Toribio, I., Moratalla-Cebrián, M. L., Bartolomé-Guitierrez, R., Cebada-Sánchez, S., Galán-Moya, E. M., and Martínez-Andrés, M. (2022). Impact of service-learning educational interventions on nursing students: an integrative review. Nurse Educ. Today 116:105417. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105417

Mendelowitz, B., and Govender, N. (2024). Critical literacies, imagination and the affective turn: postgraduate students' redesigns of race and gender in South African higher education. Linguist. Educ. 80:101285. doi: 10.1016/j.linged.2024.101285

Muñoz, C. P., Fajardo, M., and Rodríguez, R. Y. G. (2022). Solidarity territories for capacity development and collective action from the local. J. Rural. Community Dev. 17, 2–127. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12494/46890

Nauhria, S., Nauhria, S., Derksen, I., Basu, A., and Xantus, G. (2021). The impact of community service experience on the undergraduate students' learning curve and subsequent changes of the curriculum—a quality improvement project at a Caribbean Medical University. Front. Educ. 6:709411. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.709411

Olivier, L. (2021). Multimodal composition pedagogy in higher education: a paradigm shift. Per Liguam. 37:996. doi: 10.5785/37-2-996

Padrós-Cuxart, M., Crespo-López, A., Lopez de Aguileta, G., and Jarque-Mur, C. (2024). Impact on mental health and well-being of the dialogic literary gathering among women in a primary healthcare centre. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Wellbeing. 19:2370901. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2024.2370901

Ribeiro, L. M., Miranda, F., Themudo, C., Gonçalves, H., Bringle, R. G., Rosário, P., et al. (2023). Educating for the sustainable development goals through service-learning: university students' perspectives about the competences developed. Front. Educ. 8:1144134. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1144134

Ruiz-González, M. D. L. Á., Font Graupera, E., and Lazcano Herrera, C. (2015). El impacto de los intangibles en la economía del conocimiento. Econ. Desarr. 155, 119–132. Available at: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=425543135009

Shcherbyna, M., Leontieva, V., Siliutina, I., Sumiatin, S., and Shket, A. (2024). Cultura inclusiva en la comunicación educativa real y virtual. Rev. Educ. Derecho. 29, 1–19.

Singer, E. (2012). Images of the child and the unruly practice. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 20, 157–161. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2012.681441

Smith, K. L., Meah, Y., Reininger, B., Farr, M., Zeidman, J., and Thomas, D. C. (2013). Integrating service learning into the curriculum: lessons from the field. Med. Teach. 35, e1139–e1148. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.735383

Sullivan, G. (2011). The culture of community and a failure of creativity. Teach. Coll. Rec. 113, 1175–1195. doi: 10.1177/016146811111300609

Syzdykova, Z., Koblandin, K., Mikhaylova, N., and Akinina, O. (2021). Assessment of e-portfolio in higher education. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 16, 120–134. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v16i02.18819

Thomas, D. S. M. (1998). The use of portfolio learning in medical education. Med. Teach. 20, 192–199. doi: 10.1080/01421599880904

Tijsma, G., Hilverda, F., Scheffelaar, A., Alders, S., Schoonmade, L., Blignaut, N., et al. (2020). Becoming productive 21st century citizens: a systematic review uncovering design principles for integrating community service learning into higher education courses. Educ. Res. 62, 390–413. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2020.1836987

Tseris, E., and Jamieson, S. (2024). Mental health and biomedical neoliberalism: can creativity make space for social justice? Soc. Work Educ. 90, 1–8. doi: 10.1080/02615479.2024.2328790

UNESCO (2005). Towards Knowledge Societies. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000141843 (accessed August 28, 2024).

UNESCO (2013). Enfoques Estratégicos Sobre las TICs en Educación en América Latina y el Caribe. Chile: UNESCO, OREALC.

Van Dijk, T. (2009). “Critical discourse studies: a socialcognitive approach,” in Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, eds. R. Wodak and M. Meyer (Los Angeles/London: Sage), 62–86.

Wallin, P. (2023). Humanisation of higher education re-imagining the university together with students. Learn. Teach. Int. J. High. Educ. Soc. Sci. 16, 55–74. doi: 10.3167/latiss.2023.160204

Walsh, M. (2010). Multimodal literacy: what does it mean for classroom practice? Aust. J. Lang. Liter. 33, 211–239. doi: 10.1007/BF03651836

Keywords: digital literacy, multimodal literacy, community service learning, higher education, communication skills, social engagement

Citation: de Oliveira JM (2024) Enhancing multimodal literacy through community service learning in higher education. Front. Educ. 9:1448805. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1448805

Received: 13 June 2024; Accepted: 12 November 2024;

Published: 29 November 2024.

Edited by:

Silvia F. Rivas, Universidad de Salamanca, SpainReviewed by:

Samal Nauhria, St. Matthew's University, Cayman IslandsRusdi Noor Rosa, University of North Sumatra, Indonesia

Copyright © 2024 de Oliveira. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Janaina Minelli de Oliveira, amFuYWluYS5vbGl2ZWlyYSYjeDAwMDQwO3Vydi5jYXQ=

Janaina Minelli de Oliveira

Janaina Minelli de Oliveira