- 1Ministry of Education, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 2Information Systems Department, College of Computers and Information Technology, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Teacher quality is one of the most significant factors influencing the overall effectiveness of an education system. In this process, educators emphasize that teachers play the most crucial role in the educational process. Highlighting the importance of teachers draws attention to the value of their education, training, and readiness. This article discusses the history of initial teacher preparation (ITP) and its development within the context of Saudi Arabia. Drawing on the relevant literature, this review paper explores the fundamental elements that (ITP) education should include to achieve Vision 2030 goals for preparing future teachers. The paper also provides a proposed organizational framework for initial teacher preparation (ITP) in Saudi Arabia. The point in focusing on this topic lies in its academic contribution to the background context of initial teacher preparation (ITP), where little research has been published over the past years.

1 Introduction and background

Education in Saudi Arabia aims to equip learners with the tools for learning while creating and enhancing situations that facilitate their acquisition of knowledge, information, experience, and practical skills essential for leading their lives (Alharbi, 2024; Alqahtani and Albidewi, 2022). This process typically begins with school education, which is often the learners’ first significant encounter with the world beyond their immediate environment. The educational process is inherently complex, dynamic, and grounded in scientific and technical principles. It encompasses various elements, including the teacher, study materials, related activities, and teaching methods. Given that teachers are the cornerstone of this process, they must be adequately prepared to refine their teaching abilities and adopt practices that meet the diverse needs of learners (Alqahtani and Albidewi, 2022; AlHarbi, 2021). Simply having the inclination and willingness to teach is not enough. Therefore, training during the preparation phase and throughout their professional practice is essential in empowering teachers to teach effectively.

Teacher preparation is crucial to educational development policies and strategies in many countries worldwide, specifically in Saudi (Alharbi, 2024). Although global educational policies may vary, they consistently emphasize the importance of enhancing teacher preparation and qualification processes (Albaqami, 2024). Improving these programs is seen as a critical factor in increasing the overall effectiveness of the educational system in the country (Allmnakrah and Evers, 2020).

A report (UNESCO, 2024) indicated that qualified teachers are central to any high-quality educational system, and the level of its teachers measures the quality of any educational system. Allmnakrah and Evers (2020) mentioned that it has become necessary for teacher preparation to be through modern, advanced programs due to global changes, contemporary challenges, and new technologies that impose a rapid change in educational needs and skills for the workforce. Indeed, preparing the modern teacher includes a wide range of attention from educators and psychologists. This stems from the teacher’s essential and vital role in achieving educational institutions’ goals, where their preparation, qualification, and professional development have become fundamentals in improving education and learning (AlHarbi, 2021).

One of the most essential recommendations by education experts to advance Arab education and progress in the global ranking of the most successful and educated countries is the necessity to review the system of preparing and training teachers (Badawi, 2023; Waterbury, 2019; Altakhaineh and Zibin, 2021). The aim is to provide an educational framework capable of leading the educational process and enabling students to acquire knowledge and skills (Ministry of Education, 2019; Sywelem and Witte, 2013). Recently, Saudi Arabia has implemented several key initiatives to enhance professional education and training programs for teachers. This includes establishing professional standards for educators through the National Authority for Education Evaluation, aligning with the Kingdom’s Vision 2030.

1.1 Vision 2030 and the transformation

Vision 2030 is a strategic framework introduced by the Saudi Arabian government in April 2016. It aims to transform the country across various sectors by reducing its reliance on oil revenue and diversifying the economy. This ambitious plan envisions substantial economic, social, and cultural reforms by 2030 (Vision 2030: Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2023). The framework’s core objective is to shift the nation’s economy and society away from oil dependency, fostering a more diverse economic landscape and cultivating a culture open to global engagement (Alharbi, 2024). It is built upon three fundamental pillars: creating a vibrant society, building a thriving economy, and fostering an ambitious nation, all aimed at reshaping Saudi Arabia’s future (Vision 2030: Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2023).

In the field of education and teaching development, Vision 2030 places a strong emphasis on improving educational quality and developing a skilled, innovative workforce (Vision 2030: Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2023). The plan acknowledges the critical role of a well-educated population in driving the country’s economic growth and success. Critical elements of Vision 2030’s education strategy include enhancing education quality, curriculum reform, promoting research and innovation, integrating e-learning and technology, upgrading educational facilities, and encouraging lifelong learning and teacher development (Allmnakrah and Evers, 2020). Recognizing the vital role of teachers in the educational system, Vision 2030 focuses on improving teacher training and development, ensuring educators are equipped with up-to-date pedagogical methods and subject expertise.

A literature review indicates a limited number of sources in Saudi Arabia that provide comprehensive information on the historical background of initial teaching preparation (ITP) education and the overall development of teaching as a profession across the country. Furthermore, there is a noticeable gap in knowledge regarding the entire history and progression of (ITP) education. Therefore, this paper aims to offer an overview of the history of (ITP) education within Saudi Arabia, including details on teaching regulations and essential elements of (ITP). The paper briefly summarizes teacher preparation education in Saudi Arabia. The second part of the paper explores the essential element that the future (ITP) education should include and highlights the recommended (ITP) framework.

2 An overview of initial teacher preparation

Saudi Arabia’s education system was established in 1925. It happened when the Directorate of Knowledge was formed, and from then, they started overseeing four primary schools (Ministry of Education, 2020a). The Ministry of Knowledge was born in 1951 to keep checks and balances in general education (Ministry of Education, 2020a; Hakeem, 2012). Since 2005, the Ministry of Education (MOE) has been overseeing all parts of the educational process, including pre-school and university education (Ministry of Education, 2020b). The evolution of the general education system in Saudi Arabia has undergone several stages, leading to its current structure, which includes primary/elementary education lasting 6 years, intermediate education spanning 3 years, and secondary/high school also for 3 years (Ministry of Education, 2020b).

A comprehensive analysis of building the education system in Saudi Arabia focuses on the challenges. Regarding teacher qualification and teaching as a profession, significant changes influence today’s situation for teachers in Saudi Arabia. The earliest challenge that the Directorate of Knowledge stumbled upon was the creation of a staff of Saudi-qualified teachers who would establish and work in new schools (Maash, 2021). Therefore, the Directorate recruited educators from Arab countries in their neighborhood briefly until domestic teacher training programs began (AlHarbi, 2021). The need for educational institutes and qualified teachers put pressure on these training programs, and then approximately half a million Saudi teachers graduated (Ministry of Education, 2019).

Over the eighth century, Saudi Arabia saw several reforms and teacher training changes. Before that, teachers were nowhere to be seen, making immediate governmental action necessary. To address the demand, in 1926, the Directorate of Knowledge established institutes dedicated to teacher training in all parts of the Kingdom (Alghamdi and Li, 2012). Moreover, they offered educational and specialized programs for 2 years only for students right after intermediate school. These 3-year institutes later became intermediate colleges and teachers’ colleges, giving bachelor’s degrees in education after 4 years of study (Hakeem, 2012). These institutes broadened their subject offerings, attracted more and more high school graduates, and increased throughout the Kingdom.

By 2005, Saudi Arabia’s educational landscape had over 29 public universities (Ministry of Education, 2024). In the years that followed, teachers’ colleges have merged with existing universities in every region, simultaneously focusing less on educational training and more on broader education scopes (Ryan, 2023). Thus, in the present framework, anyone with a graduate degree (e.g., English, Arabic, Mathematics) can join teaching, provided they have also completed an additional educational training program (Alghamdi and Li, 2012; Alzaydi, 2010; Maash, 2021). Every university has a teacher preparation program under two distinct systems to make it more convenient. Hence, an integrated system with specialization modules and educational preparation for 5 years and a consecutive system with an educational diploma 1 year after the 4 years of specialization (Maash, 2021).

Undergraduate students can simultaneously study their specialization subjects and education-related modules in the integrated system. On the other hand, the consecutive system lets graduates complete their subject-specific coursework before applying for an educational preparation diploma program at the College of Education (Alghamdi and Li, 2012; Alzaydi, 2010; Maash, 2021). The consecutive system in Saudi Arabia shows that student-teachers begin their training and practice experience only after major studies for 4 years and getting a bachelor’s degree (Alzaydi, 2010). The teaching curriculum is based on three core areas: subject knowledge, pedagogical skills, and cultural understanding (Al-hazmi, 2003; OECD, 2020). All programs for training teachers in Saudi Arabia do not differentiate among primary, intermediate, or secondary education levels (OECD, 2020), thereby enabling graduates of these programs to teach across all stages of general education. Proposed changes for better training teachers are coming (OECD, 2020). Some include entry requirements for student-teachers, duration of educational training, and the application of integrated and consecutive systems based on the student’s subject and educational level. Additionally, in 2017, the Ministry of Education put a hold on the Initial teacher preparation (ITP) programs that apply the integrated system, followed by the consecutive system, which includes the one-year diploma in 2018 (Ministry of Education, 2021). Several reasons for the current termination of ITP are mentioned in the Ministry of Education report (2021): (1) improving the stereotypical image of the teaching profession by enhancing the performance efficiency of colleges of education. (2) Establishing a general framework for developing the pre-service teacher preparation. (3) Linking the outputs of colleges of education with the needs of the education sector. (4) Enhancing the value of the teaching profession that would raise academic performance efficiency and achieve efficiency in its human outputs and professional practice. To achieve those goals, (Figure 1) shows why today’s Saudi Arabia needs ITP. Teachers’ education must undergo a reform that provides innovative teaching training programs to show their significant role in building Saudi society.

3 Initial teacher preparation component

3.1 Foundational knowledge in teacher education

Initial teachers’ preparation must be infused with subject-specific knowledge focusing on the non-negotiable content learned and taught. Educators must deeply comprehend the subjects they intend to teach, including all critical facts, concepts, and methodologies relevant to their discipline (Noddings, 2018). Also, teachers need to be familiar with the conceptual frameworks that integrate and relate these ideas. Therefore, teacher candidates must appreciate the distinct epistemologies and methods of inquiry characteristic of different academic domains (Alghamdi, 2020). For example, understanding the difference, for instance, between mathematical proofs and historical narratives is crucial to prevent the misrepresentation of these subjects to students. Amunga et al. (2020) noticed that a prevailing challenge is observed when teacher trainees assigned to teach in primary schools are allocated subjects in which they previously demonstrated weak performance. Despite their reluctance, they often proceed to teach due to staffing shortages, leading to a need for more content knowledge.

Additionally, educators of the 21st century should be skilled enough to know how to foster every student’s unique essence and potential in their care (Chu et al., 2017). It is necessary for educators to have competencies in organizing and overseeing classroom activities and communicating effectively. Implement technology and continually use reflective practice to enhance their teaching methods. Accordingly, educational institutions must develop curricula that enable future teachers to gain profound insights into learning processes, societal and cultural dynamics, and pedagogical strategies (Amunga et al., 2020; Chu et al., 2017). These programs should equip them to apply this knowledge in modern classrooms’ diverse and multifaceted environments (Eissa, 2020). Additionally, for aspiring teachers to thrive, educational faculties must innovate the environments in which novice educators learn to teach, ensuring a transformation in the settings where they evolve into professional teachers.

3.2 Pedagogical development and skills enhancement

3.2.1 Pedagogical content knowledge (PCK)

For novice and experienced educators, enhancing their Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK) is crucial. PCK is about how specific topics or challenges are structured, conveyed, and tailored to students’ interests and abilities (Ekiz-Kiran et al., 2021). This knowledge is essential for educators to effectively translate subjects for their learners (Alotaibi and Yousse, 2023). Additionally, Ekiz-Kiran et al. (2021) showed that PCK is the educator’s ability to convert their knowledge into teaching strategies that are not only effective on a pedagogical level but also sufficiently flexible to provide to learners’ differences, depending on their abilities and backgrounds. Such adaptability is essential for maintaining a high-quality standard and impact instruction (Alotaibi and Yousse, 2023). Teachers, therefore, must focus on more than just the content they teach but also on the pedagogical approaches they employ. They should endeavor to understand their students’ preconceptions and beliefs about the subject matter and engage students actively in learning, facilitating their acquisition of new ideas through discussion and interaction.

Understanding individual learners’ beliefs, interests, and what motivates them is also vital (Alotaibi and Yousse, 2023; AlHarbi, 2021). The underlying theory of social constructivism, as proposed by Vygotsky, posits that learners construct their knowledge through social interactions, a concept that contrasts with traditional views of knowledge acquisition (Veraksa, 2022; AlHarbi, 2021). Current teacher education programs often produce educators who believe they possess all the necessary knowledge, overlooking the value of learning from their students (Eissa, 2020). This approach contradicts the student-centered methods advocated by Dewey’s philosophy, which promotes active engagement with the world as a means of learning and an active engagement with the world (Korte et al., 2022).

3.2.2 Learner-centered and interactive teaching methods

In Saudi Arabia, teacher preparation institutions focus on learner-oriented and interactive teaching methods. Nevertheless, the action of these pedagogic ways is heavily influenced by the nature and purposes of assessments being scored at the end of the programs (Eissa, 2020). These assessments, primarily designed as summative evaluation tools, often measure lower levels of achievement and tend to focus on rote learning and basic cognitive skills. Given the substantial impact of examination systems on teaching methodologies, teacher education programs must emphasize equipping trainee teachers with the skills to design and implement educational assessments that foster higher-order thinking and learning outcomes (Alghamdi, 2020).

The transformation of teacher education programs from conventional paradigms to models emphasizing comprehensive, carefully supervised practical experience closely integrated with academic coursework is vital (Alghamdi, 2020). This approach enables teacher candidates to learn from practicing experts in schools, providing a broad spectrum of student demographics. Essential elements of this learning model include widespread practical exposure, extensive supervision, demonstration of best practices by experts, and engagement with students from diverse backgrounds, all vital for equipping future teachers with the necessary skills for effective teaching (Akhyar, 2023; Babaeer, 2021). Achieving these aspects demands a significant departure from traditional practices to incorporate newly emerging approaches’ teaching strategies, pedagogies, and methodologies.

3.3 Integration of modern strategies and technologies

3.3.1 Contemporary pedagogical strategies and reflective practice

Moreover, integrating contemporary pedagogical strategies, such as detailed examination of teaching and learning processes, case studies, performance-based assessments, and action research, is crucial. These methods bridge theoretical knowledge with practical application, promoting a practical understanding of teaching concepts (Akuma and Callaghan, 2019). Such schools provide persistent exposure to actual teaching environments before candidates are assigned to diverse educational settings.

Research emphasizes the importance of preparing teachers to employ diverse instructional strategies, including cooperative learning, classroom management, and technology, enhancing their ability to educate students from varied backgrounds effectively (Almutairi et al., 2020; Alshareef et al., 2022; Chakyarkandiyil and Prakasha, 2023; Naparan and Alinsug, 2021). Moreover, in practical settings, prospective educators learn through direct observation, authentic assessment of students, and gaining insights into child learning processes, thereby refining their teaching practices. Practical schools also allow novice teachers to collaborate with experienced educators as advisors and researchers (Alatawi, 2021; Clandinin and Husu, 2022; Martinez, 2022). Additionally, teacher candidates engage in scholarly activities that involve conducting their investigations through reflective practices and action research (Rutten, 2021; El-Sayed and Zoghary, 2021; Martinez, 2022). However, the duration for a university practicum is typically one semester; teachers need more time to establish meaningful interactions with students and cover significant educational content (King Saud University (KSU)- College of Education, 2009; University Umm AlQura (UQU)– College of Education, 2009).

Collaborative learning is construed to be an asset that needs to be shared by all educators to facilitate effective teaching practices for the benefit of their students. Firstly, this collaborative approach facilitates understanding students’ learning process and is critical in tailoring relevant curricula and teaching strategies (Abdala and Hamdan, 2021). Furthermore, educators must work together to master and organize students’ interactions to facilitate learning. Secondly, collaborative learning with peers at an earlier stage of training enables prospective teachers to appreciate the importance of relating with their parents productively toward creating a friendly environment for understanding their children’s learning process at home and school (Alghamdi, 2020; El-Sayed and Zoghary, 2021; Al-Abdullatif and Aladsani, 2022). Despite the expectation that teachers should work together to enhance student understanding, there is a tendency for teachers to work independently and focus on achieving specific academic targets.

Reflective practice is another critical skill for teachers’ candidates and teachers in service, enabling them to analyze and evaluate their teaching methods and their impact on student learning (Slade et al., 2019; El-Sayed and Zoghary, 2021). Constant reflection on student ideas and comprehension allows teachers to change their teaching plans accordingly (Oo et al., 2023; Almalki, 2020; Zulfqar et al., 2022). Additionally, with student assessment focused mainly on meeting lesson objectives, traditional teacher training did not emphasize a reflection approach (Ismail and Kassem, 2022). By sufficiently incorporating reflection, current practice among teachers must rely on frequent assessments to evaluate student understanding (Kattan, 2022) and approach to teaching (Aras, 2021). Action research is a collaborative method aiming to enhance pedagogical strategies and student outcomes, and it seeks solutions to real-world issues in schools.

3.3.2 Teaching learners with special needs and inclusive education

Today, teacher education should include methods for teaching students with special needs in general education classrooms. Almalky and Alwahbi (2023) note that teacher training programs at colleges and universities should provide future teachers with the skills they need to create an inclusive classroom. Al-Rashaida and Massouti (2024) explained that potential teachers lack the proper level of training for working with students with exceptional needs. This task is especially relevant in the context of the Saudi education system as the program of training potential teachers does not contain enough resources necessarily for training teachers to work with learners of this category, so it is necessary to seek additional specialized training for the relevant specialists to work with this population (Alquraini and Rao, 2020). In addition, experts believe that teacher educators with dual training in both general and specific areas of teaching are more willing and able to work with diverse students in regular classrooms (Abu-Alghayth et al., 2024; Alquraini and Rao, 2020). This position is confirmed by Alghamdi (2020), who believes that teachers must systematically understand the features of teaching diverse students. At the same time, a previous study conducted by (Alqahtani et al., 2021) shows that revising the content of teacher education programs to include the competencies necessary for teaching students with special needs is necessary.

3.3.3 Technology in teaching

Another essential component of modern teacher preparation is integrating technology into classroom teaching. Almutairi et al. (2020) highlight the significance of using technology in facilitating students’ engagement with curriculum content, instructors, and peers, both individually and collectively, in the classroom. Furthermore, teacher candidates must be familiar with Information Communication Technology (ICT) tools and proficient in their use, which include operating systems, computer hardware, and standard software applications like email and word processors (Alkinani, 2021). Al-Shehri (2020) emphasized that teachers should recognize how technology can transform teaching and enhance access to information and knowledge in the classroom, such as how using computers can revolutionize science learning. However, the challenge remains that teachers must gain training in integrating technology into their teaching practices in many contexts.

Alkinani (2021) advocated for teacher education programs to prioritize the development of technically literate teaching professionals, supporting new educational social arrangements that leverage technology. Wiseman et al. (2018) and Alghamdi and Holland (2020) argue for the specific use of technology in schools, suggesting that teacher preparation should first recognize and then deepen these emerging literacies, ensuring that teachers are fluent in both general productivity tools and the specialized technologies used in their respective disciplines.

Therefore, teacher education programs should prepare educators as classroom researchers and collaborators (Slade et al., 2019; El-Sayed and Zoghary, 2021). Given the vast and expanding body of knowledge required for teaching and recognizing students’ diverse learning styles, teachers must be equipped to learn from each other and continuously adapt their teaching methods (Kilag et al., 2024). Teachers play a crucial role in achieving educational objectives globally. Because of their fundamental position in the educational system, teachers must receive adequate and practical training to properly fulfill their duties and responsibilities. It is essential to acknowledge that professionalism needs to be included in the entire curriculum of initial teacher preparation programs, especially the experiential learning portion.

4 Proposed framework for initial teacher preparation in Saudi Arabia

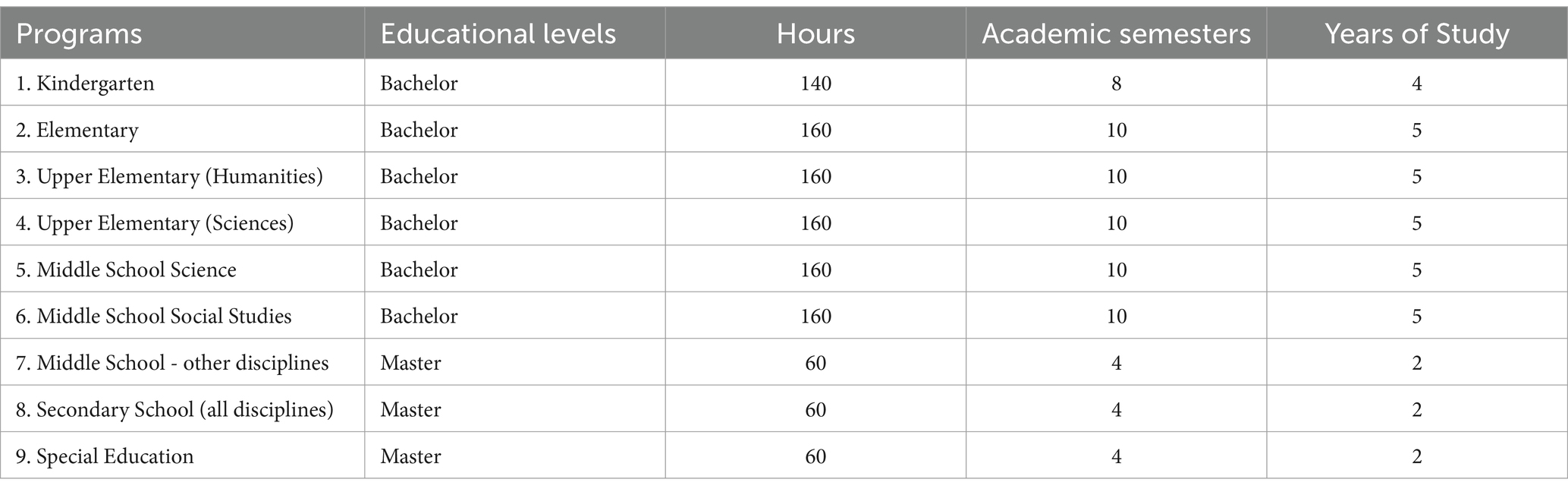

As the primary institutions responsible for developing teacher preparation programs globally, educational colleges have assigned five Saudi universities to undertake this task in collaboration with other universities. Following thorough scientific studies, global comparisons, discussion forums, and feedback from related sectors, an agreement was reached to develop nine programs covering all the future needs of the Ministry for educational positions across all schooling stages in general education from kindergarten to secondary level as follows:

1. Kindergarten Teacher Preparation Program, a four-year comprehensive bachelor’s degree.

2. The Elementary Teacher Preparation Program is a five-year comprehensive bachelor’s degree.

3. Upper Elementary Teacher Preparation Program for Humanities (Islamic Education, Arabic Language, Social Studies), a five-year comprehensive bachelor’s degree.

4. Upper Elementary Teacher Preparation Program for Sciences (Mathematics, Science, Technology), a 5-year comprehensive bachelor’s degree.

5. Middle School Science Teacher Preparation Program, a 5-year comprehensive bachelor’s degree.

6. Middle School Social Studies Teacher Preparation Program, a 5-year comprehensive bachelor’s degree.

7. Middle School Teacher Preparation Program in all subjects except Science and Social Studies, a two-year professional master’s degree with eight tracks: Arabic, English, Mathematics, Islamic Studies, Home Economics and Life Skills, Physical and Health Education, Art Education, Computer, and Information Technology.

8. Secondary School Teacher Preparation Program in all disciplines, a two-year professional master’s degree with 11 tracks: Arabic, English, Mathematics, Islamic Studies, Home Economics and Life Skills, Physical and Health Education, Art Education, Computer and Information Technology, Administrative Sciences, Social Studies.

9. Special Education Teacher Preparation Program for all stages, a two-year professional master’s degree with five tracks: Inclusive Education, High-Prevalence Disabilities, Low-Prevalence Disabilities, Sensory Disabilities, and Gifted Education.

The proposed framework (Table 1) offers a universal template for teacher training programs to adapt to their specific circumstances. By fostering such a model, teacher educators seek to normalize the outcomes for teacher education across program types and to develop a context in which aspiring teachers can use it in developing their individual pedagogical beliefs and inventive approaches to applications. The framework suggests the following strategies:

• To facilitate opportunities within a program for candidates to grapple with and solve innovative solutions to authentic classroom dilemmas.

• The design allows future teachers to articulate and clarify their values, identify appropriate teaching methods that realize these values, and master the fundamental methods of successfully installing these methods in real classrooms.

• The model provides a vision of what effective teacher engagement looks like and of the positive outcomes that educational communities can achieve.

• The pedagogical methods to support assessments and responsibilities can help motivate teacher candidates to reflect on and exhibit their emerging instruction and the various dimensions of their identities.

Adopting this organizational framework, the Initial teacher preparation aims to produce well-prepared teachers with knowledge, skills, and creativity adequate for meeting the changing requirements of the occupation.

5 Conclusion

The critical task is deciding where educators should be prepared and how they obtain the necessary subject knowledge and pedagogical skills consistent within a structure that promotes ongoing professional development in Saudi education. This raises equally valid concerns about the adequacy and exclusivity of traditional education in schools as the default settings for such preparation. Can educational colleges be sufficiently reformed to handle challenges such as diversity, globalization, technological advancement, changing and varied cultural norms, labor market needs and, often, linguistic barriers? Or is the answer to look beyond traditional teacher training altogether? Moreover, might the whole approach to teacher education need such a substantial and complete rebuild to grapple adequately with an ever more complex array of societal demands today and tomorrow? It is recommended that teacher education programs be carefully designed to encompass the socio-cultural, economic, and political dimensions of life (Aljohani, 2023). This holistic approach enables teachers to fulfill their roles as instructional leaders within their communities effectively. The most effective way to achieve this is by grounding teacher education programs in relevant research findings that focus on enhancing these programs (Al-Mwzaiji and Muhammad, 2023). Therefore, an effective education program will equip teachers to handle the different challenges. Today, teachers need to be proficient in using technology to enhance their classroom teaching. They should also be equipped to apply different methodologies, such as action research, to address classroom challenges. This involves reflecting on their teaching practices and adjusting to benefit their students’ learning experience (Fallatah, 2021). Currently, the Ministry of Education gives considerable value in reforming initial teacher preparation (ITP) programs to achieve Vision 2030 educational goals, and the path ahead demands recognizing the learners’ needs and a full spectrum of strategies to help entering teachers craft their own.

6 Limitations

There are a number of limitations to this paper review. Firstly, the review search was limited to English-language publications, which may have led to the omission of significant non-English works such as in Arabic language. Additionally, the paper explores elements that should be included in future ITP programs and proposes a recommended framework. Given this focus, the study may not comprehensively address all facets of ITP education or capture the full complexity of historical and contemporary issues in teacher preparation. In addition, the recommended framework mentioned bachelor’s and master’s degrees only due to the requirement of PhD program that might not be necessary for (ITP) programs as a preparation for teachers to teach in schools.

Author contributions

IA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdala, A., and Hamdan, A. H. E. (2021). Scaffolding strategy and customized instruction efficiency in teaching English as a foreign language in the context of Saudi Arabia. J. Liter. Lang. Linguist. 77.

Abu-Alghayth, K. M., Lane, D., and Semon, S. (2024). Comparative exploration of inclusive practices taught in special education preparation programs in Saudi universities. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 71, 774–798. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2023.2197284

Akhyar, Y. (2023). Teachers' pre-service programs curriculum to prepare professional teachers at education faculties. Indonesian J. Islamic Educ. Manag. 6, 72–84. doi: 10.24014/ijiem.v6i2.25044

Akuma, F. V., and Callaghan, R. (2019). Teaching practices linked to the implementation of inquiry-based practical work in certain science classrooms. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 56, 64–90. doi: 10.1002/tea.21469

Al-Abdullatif, A. M., and Aladsani, H. K. (2022). Parental involvement in distance K-12 learning and the effect of technostress: sustaining post-pandemic distance education in Saudi Arabia. Sustain. For. 14:11305. doi: 10.3390/su141811305

Alatawi, M. A. K. (2021). Perceptions of Saudi recently graduated unplaced special education teachers of students with intellectual disability toward their preparation. Doctoral dissertation, The University of New Mexico, United States.

Albaqami, S. E. (2024). The impact of technology-based and non-technology-based vocabulary learning activities on the pushed output vocabulary learning of Saudi EFL learners. Front. Educ. 9:1392383. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1392383

Alghamdi, S. H. (2020). The role of cooperating teachers in student teachers’ professional learning in Saudi Arabia: Reality, challenges and prospects. Dissertation, University of Glasgow, Scotlans, UK.

Alghamdi, J., and Holland, C. (2020). A comparative analysis of policies, strategies and programmes for information and communication technology integration in education in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the republic of Ireland. Educ. Inf. Technol. 25, 4721–4745. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10169-5

Alghamdi, H., and Li, L. (2012). Teaching Arabic and the preparation of its teachers before service in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Cross Discip. Subj. Educ. 3, 661–664. doi: 10.20533/ijcdse.2042.6364.2012.0093

AlHarbi, A. A. M. (2021). EFL teacher preparation programs in Saudi Arabia: an evaluation comparing status with TESOL standards. Pegem J. Educ. Instruct. 11, 237–248. doi: 10.47750/pegegog.11.04.23

Alharbi, M. S. (2024). Teachers development programs in family and everyday life skills in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Educ. Innov. Res. 3, 145–154. doi: 10.31949/ijeir.v3i2.8633

Al-hazmi, S. (2003). EFL teacher preparation programs in Saudi Arabia: trends and challenges. TESOL Q. 37, 341–344. doi: 10.2307/3588509

Aljohani, H. A. (2023). Understanding early childhood teacher education practicum programs in Saudi Arabia. Dissertation, The University of Newcastle, Australia

Alkinani, E. A. (2021). Factors affecting the use of information communication technology in teaching and learning in Saudi Arabia universities. Psychol. Educ. J. 58, 1012–1022. doi: 10.17762/pae.v58i1.849

Allmnakrah, A., and Evers, C. (2020). The need for a fundamental shift in the Saudi education system: implementing the Saudi Arabian economic vision 2030. Res. Educ. 106, 22–40. doi: 10.1177/0034523719851534

Almalki, S. M. (2020). Exploring the use of online reflective journals as a way of enhancing reflection whilst learning in the field: The experience of teachers in Saudi Arabia. Dissertation, Newcastle University, United Kingdom.

Almalky, H. A., and Alwahbi, A. A. (2023). Teachers’ perceptions of their experience with inclusive education practices in Saudi Arabia. Res. Dev. Disabil. 140:104584. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2023.104584

Almutairi, S. M., Gutub, A. A. A., and Al-Juaid, N. A. (2020). Motivating teachers to use information technology in educational process within Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Technol. Enhanced Learn. 12, 200–217. doi: 10.1504/IJTEL.2020.106286

Al-Mwzaiji, K. N. A., and Muhammad, A. A. S. (2023). EFL learning and vision 2030 in Saudi Arabia: a critical perspective. World J. English Lang. 13:435. doi: 10.5430/wjel.v13n2p435

Alotaibi, F. A. M., and Yousse, N. H. A. (2023). Knowledge of mathematics content and its relation to the mathematical pedagogical content knowledge for secondary school teachers. Pak. J. Life Soc. Sci. 21, 255–271. doi: 10.57239/PJLSS-2023-21.1.0020

Alqahtani, M. H., and Albidewi, I. A. (2022). Teachers’ English language training programmes in Saudi Arabia for achieving sustainability in education. Sustain. For. 14:15323. doi: 10.3390/su142215323

Alqahtani, R. F., Alshuayl, M., and Ryndak, D. L. (2021). Special education in Saudi Arabia: a descriptive analysis of 32 years of research. J. Int. Special Needs Educ. 24, 76–85. doi: 10.9782/JISNE-D-19-00039

Alquraini, T. A., and Rao, S. M. (2020). Assessing teachers’ knowledge, readiness, and needs to implement universal Design for Learning in classrooms in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 24, 103–114. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2018.1452298

Al-Rashaida, M., and Massouti, A. (2024). Assessing the efficacy of online teacher training programs in preparing pre-service teachers to support students with special educational needs in mainstream classrooms in the UAE: a case study. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 24, 188–200. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12624

Alshareef, K. K., Imbeau, M. B., and Albiladi, W. S. (2022). Exploring the use of technology to differentiate instruction among teachers of gifted and talented students in Saudi Arabia. Gift. Talented Int. 37, 64–82. doi: 10.1080/15332276.2022.2041507

Al-Shehri, S. (2020). Transforming English language education in Saudi Arabia: why does technology matter? Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 15, 108–123. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v15i06.12655

Altakhaineh, A. R. M., and Zibin, A. (2021). A new perspective on university ranking methods worldwide and in the Arab region: facts and suggestions. Qual. High. Educ. 27, 282–305. doi: 10.1080/13538322.2021.1937819

Alzaydi, D. A. (2010). Activity theory as a lens to explore participant perspectives of the administrative and academic activity systems in a university–school partnership in initial teacher education in Saudi Arabia. Dissertation. University of Exeter, United Kingdom.

Amunga, J., Were, D., and Ashioya, I. (2020). The teacher-parent Nexus in the competency based curriculum success equation in Kenya. Int. J. Educ. Admin. Policy Stud. 12, 60–76. doi: 10.5897/IJEAPS2020.0646

Aras, S. (2021). Action research as an inquiry-based teaching practice model for teacher education programs. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 34, 153–168. doi: 10.1007/s11213-020-09526-9

Babaeer, S. (2021). A transcendental phenomenological study of supervision in teacher preparation in Saudi Arabia. Dissertation, University of South Florida, United States.

Badawi, H. (2023). Learning from Japan: advancing education in the Arab and Islamic world through creative approaches. Nazhruna 6, 290–305. doi: 10.31538/nzh.v6i2.3516

Chakyarkandiyil, N., and Prakasha, G. S. (2023). Cooperative learning strategies: implementation challenges. Teach. Educ. 81:340. doi: 10.33225/pec/23.81.340

Chu, S. K. W., Reynolds, R. B., Tavares, N. J., Notari, M., and Lee, C. W. Y. (2017). 21st century skills development through inquiry-based learning from theory to practice. Singapore: Springer International Publishing.

Clandinin, D. J., and Husu, J. (2022). “Personal practical knowledge in teacher education” in Encyclopedia of teacher education. ed. M. A. Peters (Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore), 1252–1257.

Eissa, R. (2020). Teaching practices of university professors in Saudi Arabia: The impact on students’ learning. Dissertation, University of St. Thomas.

Ekiz-Kiran, B., Boz, Y., and Oztay, E. S. (2021). Development of pre-service teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge through a PCK-based school experience course. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 22, 415–430. doi: 10.1039/d0rp00225a

El-Sayed, S. A., and Zoghary, S. Z. (2021). Investigation of reflective practice for pre-service teachers in Saudi Arabia. Psychol. Educ. 58, 1553–6939.

Fallatah, R. (2021). Curriculum development in Saudi Arabia: Saudi primary EFL teachers’ Perspectives of the challenges of implementing CLT into the English curriculum in state schools. Dissertation, Exeter University, United Kingdom.

Ismail, S. M., and Kassem, M. A. M. (2022). Revisiting creative teaching approach in Saudi EFL classes: theoretical and pedagogical perspective. WORLD 12:142. doi: 10.5430/wjel.v12n1p142

Kattan, S. A. (2022). Teacher evaluation in Saudi Arabia relative to national and international teacher evaluation standards and best practices. United States: Western Michigan University.

Kilag, O. K. T., Malbas, M. H., Miñoza, J. R., Ledesma, M. M. R., Vestal, A. B. E., and Sasan, J. M. V. (2024). The views of the faculty on the effectiveness of teacher education programs in developing lifelong learning competence. Eur. J. Higher Educ. Acad. Advanc. 1, 92–102. doi: 10.61796/ejheaa.v1i2.106

King Saud University (KSU)- College of Education (2009). The theoretical framework for educational college. Saudi Arabia: KSU.

Korte, R., Mina, M., Frezza, S., and Nordquest, D. A. (2022). “John Dewey’s philosophical perspectives and engineering education” in Philosophy and engineering education. eds. A. N. David, M Mani, and F. Stephen (Springer International Publishing AG), 17–33.

Maash, W. (2021). An overview of teacher education and the teaching profession in Saudi Arabia: private vs. public sector. Int. J. Cross Discip. Subj. Educ. 12, 4335–4338. doi: 10.20533/ijcdse.2042.6364.2021.0531

Martinez, C. (2022). Developing 21st century teaching skills: a case study of teaching and learning through project-based curriculum. Cogent Education 9:2024936. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2021.2024936

Ministry of Education . (2019). General education data. Available at: https://departments.moe.gov.sa/PlanningDevelopment/RelatedDepartments/Educationstatisticscenter/OpenData/OpenData1440/bar1440_1439.html (Accessed January 27, 2024).

Ministry of Education . (2020a). Establishment of the Ministry of Education. Available at: https://www.moe.gov.sa (Accessed April 27, 2020)

Ministry of Education . (2020b). Objectives 2020. Available at: https://www.moe.gov.sa/ar/PublicEducation/ResidentsAndVisitors/Pages/TooAndAimsOfEd ucation.aspx (Accessed January 27, 2024)

Ministry of Education . (2021). The historical record of reports, speeches, and decisions related to the teacher preparation program. Saudi Arabia: MOE.

Ministry of Education . (2024). Public universities. Available at: https://moe.gov.sa/en/education/highereducation/Pages/UniversitiesList.aspx (Accessed January 27, 2024).

Naparan, G. B., and Alinsug, V. G. (2021). Classroom strategies of multigrade teachers. Soc. Sci. Human. Open 3:100109. doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100109

OECD (2020). Education in Saudi Arabia, Reviews of National Policies for Education. Paris, Boulder: OECD Publishing.

Oo, T. Z., Habók, A., and Józsa, K. (2023). Qualifying method-centered teaching approaches through the reflective teaching model for Reading comprehension. Educ. Sci. 13:473. doi: 10.3390/educsci13050473

Rutten, L. (2021). Toward a theory of action for practitioner inquiry as professional development in preservice teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 97:103194. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2020.103194

Ryan, M. (2023). Higher education in Saudi Arabia: challenges, opportunities, and future directions. Res. High. Educ. J. 43, 1–15.

Slade, M. L., Burnham, T. J., Catalana, S. M., and Waters, T. (2019). The impact of reflective practice on teacher Candidates' learning. Int. J. Scholarship Teach. Learn. 13:15. doi: 10.20429/ijsotl.2019.130215

Sywelem, M. M. G., and Witte, J. E. (2013). Continuing professional development: perceptions of elementary school teachers in Saudi Arabia. J. Modern Educ. Rev. 3, 881–898.

UNESCO (2024). Global report on teachers: addressing teacher shortages and transforming the profession. Paris: UNESCO.

University Umm AlQura (UQU)– College of Education (2009). Guideline for teachers practicum. Saudi Arabia: UQU.

Veraksa, N. (2022). “Vygotsky’s theory: culture as a prerequisite for education” in Piaget and Vygotsky in XXI century: Discourse in early childhood education. eds. I. Pramling Samuelsson and N. Veraksa (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 7–26.

Vision 2030: Kingdom of Saudi Arabia . (2023). Vision 2030. Available at: http://vision2030.gov.sa (Accessed January 10, 2024).

Waterbury, J. (2019). “Reform of higher education in the Arab world” in Major challenges facing higher education in the Arab world: Quality assurance and relevance. eds. A. Badran, E. Baydoun, and J. R. Hillman (United Kingdom: Springer International Publishing), 133–166.

Wiseman, A. W., Al-bakr, F., Davidson, P. M., and Bruce, E. (2018). Using technology to break gender barriers: genderdifferences in teachers’ information and communication technology use in Saudi Arabian classrooms. Compare 48, 224–243. doi: 10.1080/03057925.2017.1301200

Keywords: education in Saudi Arabia, initial teacher preparation, teacher preparation, teaching framework, teaching strategy

Citation: Alharbi MS and Albidewi IA (2024) Initial teacher preparation program in Saudi Arabia: history and framework for transformation toward a new era. Front. Educ. 9:1442528. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1442528

Edited by:

Gina Chianese, University of Trieste, ItalyReviewed by:

Niroj Dahal, Kathmandu University, NepalMuhammad Kristiawan, University of Bengkulu, Indonesia

Copyright © 2024 Alharbi and Albidewi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mashael S. Alharbi, bWFzaGFlbC5hbGhhcmJpQGFsdW1uaS51YmMuY2E=

Mashael S. Alharbi

Mashael S. Alharbi Ibrahim A. Albidewi2

Ibrahim A. Albidewi2