- WestEd, San Francisco, CA, United States

In recent years, improvement researchers have sought to foreground equity in continuous improvement (CI) in efforts to better advance the position of Black, Brown, and other marginalized students in educational settings using CI. While we view these efforts as noble and necessary, we argue in this paper that CI has largely centered equity and pushed justice to the periphery. In particular, we argue that the field of CI in education has focused squarely on equity—what we define as reducing racial and other gaps in dominant outcomes. In so doing, CI has deprioritized justice, which we define as improving outcomes that center on the comfort, agency, and dignity of all students, but minoritized students (i.e., Black, Brown, LGBTQ+, disabled, multilingual youth, and working-class) in particular. In so doing, CI efforts risk upholding dominant schooling outcomes and accompanying practices that sort students into unequal categories, limiting the capability of minoritized students to reach their full potential, erasing and demeaning students' cultural wealth, knowledge, and identities, and restricting their access to rich learning opportunities. We argue for a continuous improvement for justice that: (a) confronts dominant outcomes rather than uncritically prioritizing them; and (b) aims to use its tools to create systems that prioritize outcomes that grant comfort, agency, and dignity to minoritized students and communities.

Introduction

In their introductory chapter to the Foundational Handbook on Improvement Research in Education, Russell and Penuel (2022) highlight how the field of CI has largely backgrounded issues of equity. In doing so, they preface conceptual work within the handbook aimed at centering equity in continuous improvement, such as Eddy-Spicer and Gomez (2022) framework for centering strong equity in continuous improvement and Jabbar and Childs's (2022) chapter on critical perspectives in improvement research. Other work in, prior to, and since the generation of the handbook has sought to engage equity in the context of CI in efforts to advance the field's equity stance. For instance, Valdez et al. (2020) engaged continuous improvement leaders in education to surface the range of conceptions and enactments of equity in CI efforts in education. Borrowing from the National Equity Project's definition of equity,1 Valdez et al. unveil that educational leaders view the potential for CI to advance equity, recognize that doing so requires intentionality, and engage in a range of practices to do so. In the handbook, Eddy-Spicer and Gomez (2022) articulated a framework for examining the ethic of equity within improvement efforts. They draw on Cochran-Smith's (2016) conceptualization of strong equity, which refers to the acknowledgment of complex social systems that produce inequalities, in contrast with thin equity, which concerns “equitable individual outcomes that align with educational goals that are universally applied and presumed to be universally shared” (Eddy-Spicer and Gomez, 2022, p. 90). They argue that an improvement effort's future orientation, orientation to process, and epistemic accomplishment form an ethic of equity. As another example, Bush-Mecenas (2022) examined how equity was institutionalized within CI efforts and CI-focused educational intermediaries that provide technical assistance to schools and districts. She describes how organizations combined performance logics and racial equity logics, using performance metrics, routines, and professional norms to do so.

This work on centering equity in CI demonstrates the field's commitment to addressing disparities in educational outcomes for Black, Brown, LGBTQ+, working-class, and disabled students. At the same time, however, existing work on CI and equity has largely avoided taking critical perspectives to equity-focused CI efforts that would allow for closer examinations of race, class, gender, disability, power dynamics, and system of oppression (Jabbar and Childs, 2022). Additionally, improvement research has blurred the conceptual and practical waters around equity and social and racial justice, either positioning equity as the process that results in justice (e.g., Peurach et al., 2022; Bush-Mecenas, 2022) or conflating the two altogether (e.g., Valdez et al., 2020). Although well-intentioned, the blurring of boundaries between equity and justice have prioritized a continuous improvement approach that foregrounds a narrow conception of equity in its theory and practice. To date, equity-focused improvement has coalesced around reducing racial disparities in outcomes already prioritized by existing systems of schooling, as evidenced in Bush-Mecenas's (2022) study and in Valdez et al.'s (2020) insights from the field. This orientation to equity (and, by extension, justice) in improvement limits the capacity of the field to consider more expansive notions of equity (and justice) and, in turn, constrains the ability of improvement researchers and practitioners to generate axiological innovations in the same way researchers in other pragmatist traditions, namely design-based research, have done (Bang and Vossoughi, 2016; Bang et al., 2015; Gutiérrez and Vossoughi, 2010).

The aim of this paper is to conceptualize and draw boundaries between equity and justice within the context of continuous improvement research and practice and, more importantly, articulate a justice-focused improvement and its components. In particular, we argue that a continuous improvement for equity in education foregrounds reducing disparities in dominant outcomes for minoritized learners; while a continuous improvement for justice foregrounds improving the comfort, dignity, and agency of minoritized learners in schools. We also articulate what it might mean to enact an improvement for justice, highlighting what improvement practitioners can do to center justice. To do this, we first discuss outcomes in improvement; the role they play in shaping improvement efforts, the dominant outcomes that disproportionately shape the direction of improvement work, the purpose of schooling that undergird those dominant outcomes, and a set of outcomes rooted in justice. We then turn to articulate a set of practices that constitute a working model of justice-focused improvement, highlighting how these practices come to better center the justice-focused outcomes we offer. We then illustrate the potential of these practices for both scholarly and practical use by examining the public case of the School District of Menomonee Falls, a Carnegie Foundation Spotlight Honoree, granted to exemplars of improvement efforts in districts and at scale. We then offer some directions for future research and practice, highlighting both the scholarly and capacity-building needs for the field of improvement to better center justice.

Although we distinguish between CI for equity and CI for justice, and although we argue for more justice-focused improvement work, we recognize that both are critical to improving schools for minoritized students. We call to mind the wide range of scholarly and practical work that both draws similar distinctions but brings both equity and justice together, highlighting the need to “do both” (e.g., Gutiérrez, 2011; Neri et al., 2023). However, CI work has specifically focused on equity and elevates the need for more justice-focused work in order to “do both.”

Interrogating outcomes in improvement

A central tenet of CI in education concerns naming and holding central the outcomes that they aim to improve. “What are we trying to accomplish?” is the central question that organizes CI approaches; though obvious on its face, efforts to improve education and social systems more broadly often background the purpose and outcomes of their work (Bryk et al., 2015; Hinnant-Crawford, 2020; Langley et al., 2009). Alongside this stated commitment to centering outcomes, CI efforts practice the work of centering on outcomes via a suite of tools: aim statements, for example, are intended to articulate measurable, specific targets that drive improvement work; driver diagrams are visual representations meant to represent a theory of improvement that connects specific activities and actions to outcomes through a series of conjectures and hypotheses (Bennett and Provost, 2015; Hinnant-Crawford, 2020). Outcomes are central components of CI efforts that organize and dictate efforts.

Despite the stated and practiced importance of outcomes in CI, the field of CI offers little insight into what outcomes improvement work ought to prioritize in theory and even less interrogation of the outcomes that come to shape improvement work in practice. To date, improvement efforts have largely focused on improving what we refer to as dominant outcomes (Bush-Mecenas, 2022; Yurkofsky et al., 2020), or outcomes that are currently prioritized by existing systems of schooling to uphold schooling's existing purpose in sorting children for labor markets and apprenticing children into White, Western, European culture (Domina et al., 2017; Stovall, 2018). Although CI scholars and practitioners have sought to examine how race, gender, and other forms of identity matter for improvement work, research on and practice in CI has offered little by way of troubling the prioritization of these outcomes, thereby positioning these outcomes as critically important over other, justice-focused outcomes. In this section of our paper, we articulate what constitutes dominant outcomes and highlight how these outcomes come to uphold a system of schooling that is ultimately harmful to minoritized students. Then, we offer a set of justice-focused outcomes that we argue should be the subject of more improvement work going forward. To end this section, we highlight the tension between dominant and justice-focused outcomes, harkening to prior research on equity and justice in education that has surfaced similar tensions.

Dominant educational outcomes

We define dominant outcomes as outcomes that reify the purpose of and organize existing systems of schools and schooling. These outcomes include measures of student achievement in the form of standardized test scores and attendance in schools, both of which are metrics that states are required to report on and have significant implications for what comes to shape the priorities of local and state education agencies (Darling-Hammond, 2007; Jordan and Miller, 2017; Russo, 2016). Despite the tremendous amount of resources spent on improving these outcomes to uphold the existing system of schooling, scholars have long critiqued how these outcomes reify the purpose of schoolsas ultimately the production of bodies for labor markets (e.g., Freire, 1970; Ladson-Billings and Tate, 1995; Warren et al., 2020).

For instance, Domina et al. (2017) highlight how schools serve as sorting machines, sorting children and, in turn, producing what they call categorical inequality. Schools, they argue, create internal categories that include grades and tracks and adopt “imposed categories such as accountability labels” (p. 314), using dominant outcomes to generate these categories. Similarly, Domina et al. make visible that accountability policies themselves create categories organized by student proficiency, which “lead to the construction of socially meaningful categories both within and among schools” (p. 317). These categories, the authors argue, play a central role in the production of inequality. For example, the generation of categories of students such as English language learners or gifted students, they argue, result in unequal access to cognitively demanding tasks and rich learning environments, which includes teachers that prefer to teach so-called high-track classes. At the end of students' educational journeys, the differentiation in status ascribed to students via schools then has implications for their place in the workforce, highlighting how schools act as agents of capitalism, producing categories of bodies readymade for labor markets. Dominant outcomes and their accompanying metrics play a crucial role in mediating the generation of these categories and, in turn, the generation of inequality more broadly.

Similarly, Stovall (2018) argues that the primary purpose of schools and schooling are to uphold settler colonialism, white supremacy, and racism, imposing what Stovall calls the “assumed beliefs and cultural values of White, Western European, protestant, heterosexual, able-bodies, cis-gendered males” on children (p. 52). Schools punish those that do not fit within these narrow boundaries, often in the form of suspension, expulsions, reducing access to learning and interactions with other students, and more (Stovall, 2020). In this frame, dominant metrics, such as high-stakes test scores, enable the production and upholding of a schooling purpose that is centrally concerned with apprenticing children into what Nieto (1992) calls the dominant culture, standardized around White, Western Europeans.

These dominant outcomes and accompanying metrics themselves reify the purpose of schools as producing narrow ways of being, knowing, and doing rooted in the dominant culture and marginalizing ways of being, knowing, and doing that fit outside the confines of the dominant culture. Cunningham (2019), for instance, highlights how standardized tests are tools of epistemological erasure that background “the learning gained through interactive classroom and real-world experiences” (p. 116). These metrics ignore and marginalize existing ways of knowing that Black and Brown students come to classrooms with, often knowledge that has been cultivated from their own families and communities. The tests, Cunningham argues, reify and are tools of capitalist ideologies that foreground rationality, individualism, and progress.espite this, and despite long-standing calls for alternative measures, these tests, and their positioning as dominant metrics that every school and educator must be held accountable to, persist.

There is no shortage of research that names and interrogates the existing purpose of schooling oriented toward cultural assimilation and production for labor markets, and a plethora of research highlights how dominant outcomes and accompanying metrics uphold that purpose. While we recognize the need to better enable minoritized students to survive and succeed this system as a harm reduction tactic—what Neri et al. (2023) articulate as expedient justice and what Gutiérrez (2011) calls the dominant axis of equity—we also highlight that CI work ought to increase its focus on imagining just worlds and futures and engaging in work to enact those futures. We turn to describe alternative outcomes for schools that align with visions of justice in schools and society more broadly.

Justice-focused educational outcomes

For several decades, education scholars and practitioners have sought to imagine an alternative purpose of schooling that prioritizes the comfort, the dignity, and the agency of all students, and in particular, minoritized students, for whom comfort, dignity, and agency are historically restricted in schools. By comfort, we refer to both joy and the absence of pain, violence, and erasure; by dignity, we refer to dictionary definitions that center worthiness of honor and respect; and by agency, we refer to the capacity to do otherwise. We offer slightly more detailed conceptualizations of each before putting them in tension with dominant outcomes in education.

Comfort

We conceptualize comfort as the presence of joy and the absence of pain and violence. In the context of education and schooling, we draw on King (2017) view of violence as enacted through curricula, where Black and Brown students are dispossessed of their cultures and ancestry. King refers to this process as epistemological nihilation, subjugating Black and Brown students as “others” relative to dominant norms of whiteness and positioning and enabling students to feel unwelcome and less-than in learning environments. For King, the process of epistemological nihilation “justifies a group's physical annihilation” (p. 213).

In addition to absence of pain and violence in the form of erasure and the processes of othering, we view comfort as the prioritization of joy, in line with Adams's (2022) and Miles and Roby's (2022) work on centering Black joy to design for and enact liberatory science education spaces. For these authors, Black joy is a form of resilience and resistance to the oppressive features, practices, processes, and routines of schooling. Additionally, Adams views Black joy as liberatory in that the production of Black joy enlivens conversations about what education, learning, and schooling could be, namely focused on the development of positive Black students' identities, both culturally and within subject matter areas such as science. Our view of comfort—as defined by the absence of violence and pain, and the presence of joy, in particular for those who are less likely to experience joy in schools—sits at the center of our view of justice-focused outcomes in schools and schoolings.

Dignity

We draw on work from Espinoza and Vossoughi (2014) that conceptualizes learning as dignity-conferring to highlight how a central outcome of education ought to focus on the granting of respect, the development of self-respect, and the accomplishment of human flourishing, particularly minoritized students. For Espinoza and Vossoughi, dignity is both conferred and produced through learning, and the rights to learning and dignity are tightly intertwined. To illustrate this, Espinoza and Vossoughi draw on African slave narratives who sought to generate dignity for themselves through learning, despite all efforts to prevent them from doing so.

We also draw on the work of King (2017) who articulates a racial/cultural dignity grounded in group belonging and identification with one's own culture. King draws on African epistemology to highlight that the purpose of knowledge is to enable human flourishing, that knowledge is for “humanity's sake” (p. 218), where the consumption and production of knowledge are for the benefit of people. King, in contrasting to the dominant processes of epistemological nihilation in schools, views engagement with these epistemologies a form of “epistemological emancipation” (p. 218), highlighting how these stances on knowledge are peripheralized in schools and schooling, thereby foregrounding a dominant epistemology rooted in whiteness and enacted through curricular violence and erasure. We thus conceptualize dignity as the granting of respect, enabling of self-respect, and the foregrounding of human flourishing.

Agency

We draw on practice theoretical views of agency, namely from Giddens (1984) who views agency as the capacity to do otherwise, and Emirbayer and Mische (1998), who conceptualize agency as a temporally embedded process of social engagement, where capacities for action are temporally situated within past, present, and future at once. We explicitly contrast this relational view of agency to individualistic notions of agency (e.g., Bandura, 2006), which are rooted in self-efficacy and beliefs about one's abilities to act. We view such conceptualizations of student agency as shifting the onus of action on students, rather than properly situating their capacity to act within the complex learning environments within which they are situated, including the histories of participation in classrooms into which schools apprentice students, what are expectations for participation in the present, and visions for how they should learn to participate in the future. By conceptualizing agency in this way, we argue that schools and educational environments broadly ought to shift relations to enable students to actively shape their learning environments.

Following this view of agency, we bring in a practice-focused conception of power, where some actors are more agentic than others, with wider possibilities for action they might take moment-to-moment (Watson, 2016). In viewing power as produced rather than as a currency that is distributed, Watson conceptualizes power as practiced through structured and structuring action. In this practice view of power, the production of power is characterized as the ability to act in ways that disproportionately constrains and enables others' actions. Dominant, individualistic notions of agency and, in turn, power, leave unexamined how adults are positioned relative to students such that their actions disproportionately constrain and enable students' actions, thereby limiting their agency. For instance, teachers who have narrow, white, western European conceptions of what is considered “acceptable behavior” may enact this on students by disciplining those who do not fit within what is considered “acceptable,” a practice that is commonly levied against Black and Brown students in classrooms, resulting in their exclusion (Battey and Leyva, 2016). In this instance, teachers have greater capacities to act; they can send students out of class into hallways, send them to the office, begin processes of suspension and expulsion, or start other processes of exclusion; meanwhile, students have little capacity to respond that does not result in exclusion from the learning environment.

Merchant et al. (2020) take up this view of agency and power to understand how higher education institutions engage in what they call disabling practices that, in turn, dramatically constrain disabled staff and students' actions. Seemingly mundane practices, such as how administrators allocated and timetabled rooms to staff produced exclusion in ways that disable staff and students and constrained their capacity to act in ways that enabled them to participate in day-to-day higher education practice.

Within this frame of agency, we argue that a central justice-focused outcome in improvement concerns ensuring students—and minoritized students in particular—are agentic in that they have the capacity to shape the school, classroom, and other learning environments within which they participate. Students ought to have the capacity to determine what is and is not relevant, what is and is not useful, what they can and cannot do with their bodies, whether and how they would like to participate in the work of schooling at any particular moment, what constitutes joy, and so on. Such an orientation to agency also enlivens a concern with enabling students to critique and interrogate school and classroom practices and processes, to identify that which is just and unjust in schools, to shape the environment to better meet their needs and interests. We argue that such an orientation to, conceptualization of, and enactment of agency constitutes an outcome to which all justice-focused educators ought to aspire.

Tensioning dominant and justice-focused outcomes

We resurface that an improvement for equity centers its work on the reduction of disparities in dominant outcomes for minoritized students, while an improvement for justice centers on the work of granting agency, comfort, and dignity to students, and to minoritized students in particular. We offered detailed conceptualizations of these categories of outcomes to highlight the distinction between them.

We put dominant and justice-focused outcomes in tension with one another to argue that the so-called “north stars” of improvement work ought to be interrogated. We note that this distinction and tension between dominant outcomes and justice-focused outcomes reflect a common tension among justice-focused educators and researchers. Neri et al. (2023), for instance, refer to a similar tension between fair-world justice and expedient justice. Fair-world justice refers to the work of centering Black and Brown students' cultural assets in curricula and pedagogy, such that learning environments are organized to enable those students to receive and be granted comfort, agency, and dignity in classrooms. On the other hand, expedient justice refers to the work of enabling Black and Brown students to access codes of power, or the features of schooling that “select for cultural attributes of students from dominant structural positions” (p. 1513). The tension between these two is one that author and colleagues must be the subject of negotiation for all social-educational justice projects. Similarly, Gutiérrez (2009) conceptualized equity in mathematics learning and teaching using two axes: a dominant axis that prioritizes granting access to mathematics and enabling mathematics achievement—defined by dominant metrics—among minoritized students; and a critical axis that prioritizes the development and leveraging of students' cultural identities and an attention to power where students are being positioned to become critical citizens who interrogate the world around them. Thus, our distinction between dominant outcomes and justice-focused outcomes is not a new one, but instead extends existing tensions between the two in educational justice circles into the world of improvement. We argue that those responsible for leading improvement work ought to deliberately and explicitly engage these tensions when forging new work.

We offer a caveat in our attempt to tension justice-focused and dominant outcomes. While engaging the tension between the two is critical to centering justice in improvement, we also recognize that the two are often inseparable or, for the sake of advancing justice, should not always be separated. For instance, Browning's (2024) study on using improvement science to reduce racial disparities in discipline in her school highlights how discipline rates are dominant metrics to which schools and districts are held accountable to reducing. In that study, however, she also makes clear the importance of generating a school and classroom culture that affirms the identities of Black and Brown students as a way to reduce the rates of disciplinary practices levied against those students. Browning's work makes clear that the dominant outcome of reducing disciplinary rates can be at once both an equity challenge focused on reducing a disparity in a dominant outcome, as well as a challenge focused on imagining new visions for schooling that prioritize the comfort, agency, and dignity of Black and Brown students.

Our goal for this section was to highlight the centrality of outcomes in the work of improvement, to trouble the dominant answers to the improvement question, “What are we trying to accomplish?”, and to imagine a new set of justice-focused outcomes to which improvement work ought to attend. Having addressed each of these three goals, we turn to the heart of this paper: a set of practices for enacting an improvement for justice.

Practices for a continuous improvement for justice

We focus on proposing a set of practices for a justice-focused improvement for three reasons. First, the field of improvement research is a practical and pragmatic one that is concerned with improving practice in the first position, and generating new knowledge in the second (and typically only in service of improving practice). Thus, a set of practices engenders conversations about the possibility for what improvement practitioners and researchers can do to advance justice, and is in line with ongoing conversations about improvement. Second, we offer a set of practices as a way to analyze the performativity of improvement. Drawing on practice theoretical perspectives (Feldman and Worline, 2016), we reject conceptualizations of continuous improvement that treat it as a disembodied methodology that exists outside of or prior to action, but is instead constituted through action and made up of a set of routines that are enacted, performed, and embodied moment-to-moment. In this frame, “what it means to do improvement” is reinforced, upheld, disrupted, upended, or otherwise modified or sustained through actions every single moment. Articulating a set of practices for a continuous improvement for justice provides a set of tools for understanding how improvement comes to be enacted and the extent to which those enactments center justice. Third, and relatedly, a focus on practices illustrates that making CI a justice-focused approach requires effort. We argue against notions that CI is inherently more oriented toward either equity or justice, that doing improvement is more equitable and just than not. Continuous improvement, as is the case for a wide range of other approaches, is as capable of enabling the production of harm against minoritized students as it is ameliorating it. While much has been written about its potential for addressing equity and justice (e.g., Anderson et al., 2023), fulfilling that potential requires action to do so, and that improvement work has, generally, fallen short of that potential. Finally, we offer a set of practices to emphasize the provisionality of our conception of justice in the context of improvement. Research on improvement practices are far and few between as-is (Sandoval, 2023; Sandoval et al., 2024); we offer a set of practices to recognize that their enactments will come to modify what it means to do improvement for justice and, in turn, the practices that we articulate here.

To articulate these practices, we draw on work from critical design-based researchers and other critical scholars engaged in collaborative or partnership-focused research. We draw on this work because critical design scholars have sought to reshape what it means to engage in design work, seeking to highlight that design is not an apolitical, value-neutral process, and using this to reorient design toward equity and justice for Black, Brown, and other minoritized students. We view continuous improvement in education as being at a similar point in its trajectory as design-based research was over 20 years ago. We draw on other critical scholarship to bring improvement into conversation with critical perspectives and to substantiate and illustrate our view of improvement for justice.

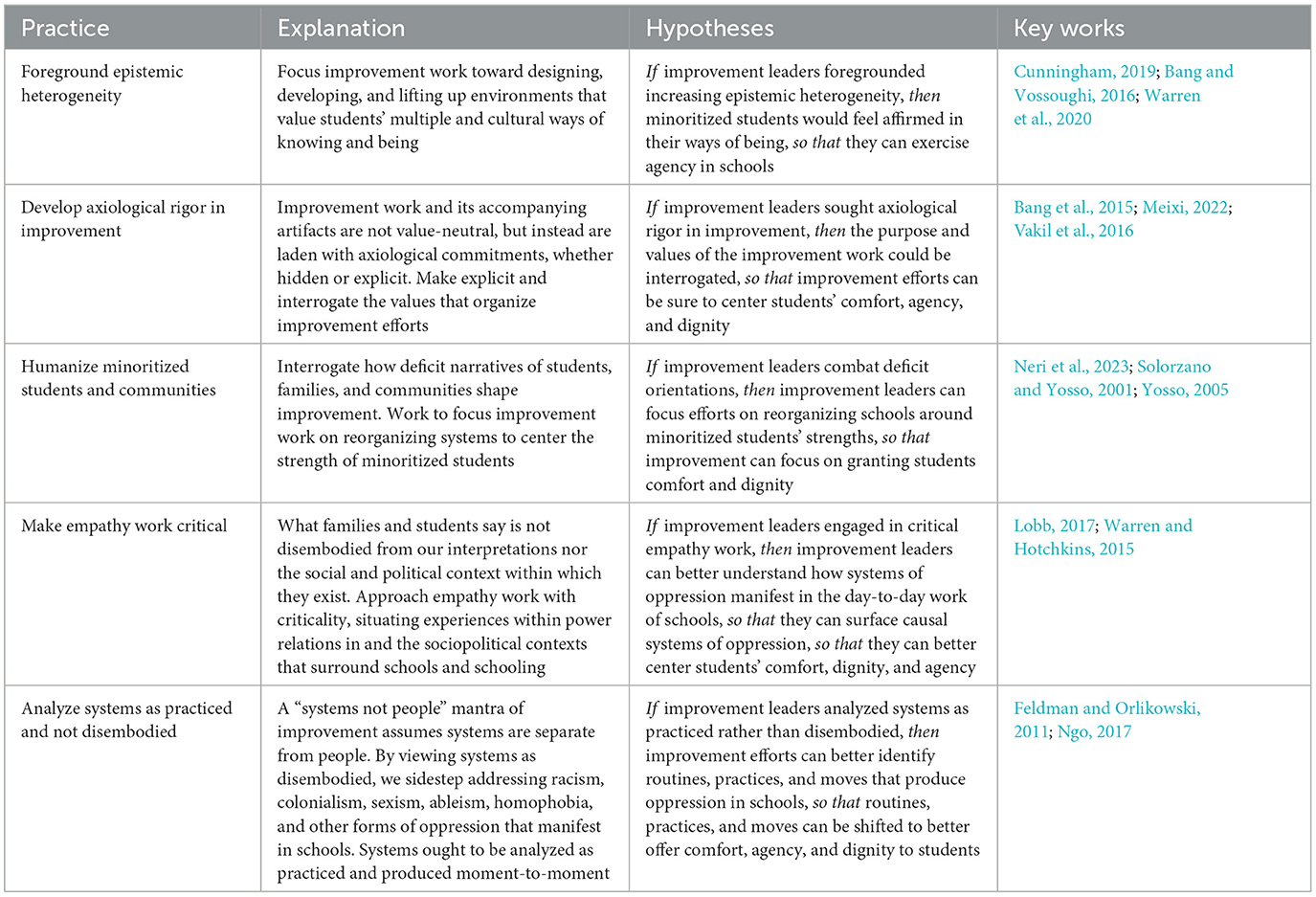

Table 1 articulates the five practices for an improvement for justice, along with a set of hypotheses for how they might orient improvement toward students' comfort, agency, and dignity, as well as key works that each practice draws on. The five practices are:

• Foreground epistemic heterogeneity.

• Develop axiological rigor.

• Humanize minoritized students and communities.

• Make empathy work critical.

• Analyze systems as practiced and disembodied.

We turn to offer a description of each practice.

Foreground epistemic heterogeneity in improvement efforts

Central to our conception of an improvement for justice is a focus on reorganizing systems of schooling to enable and honor minoritized students' varied ways of knowing and being, or what Bang and Vossoughi (2016) and Warren et al. (2020) refer to as epistemic heterogeneity.2 In conceptualizing epistemic heterogeneity, Warren et al. highlight the inextricability of both knowing and being, as well as the importance of a liberatory education that is grounded in “multiple values, purposes, and arcs of human learning” (p. 278). The work of epistemic heterogeneity, then, is centrally concerned with reorganizing environments where children learn around a range of ways of knowing that do not center assimilation into what Warren et al. call Western supremacy. We view this proposed practice of foregrounding epistemic heterogeneity as combating epistemic violence and erasure that currently organizes schools (Cunningham, 2019; King, 2017), while granting students agency to (re)shape classrooms and schools. In their introduction to a special issue in Cognition and Instruction, Bang and Vossoughi argue that work on educational equity has gained legitimacy by focusing on what they call “political and economic imperatives,” resulting in equity work that is focused on “apprenticing young people into the codes of power and forms of ‘cultural capital' that are required to enter” the workforce or marketplace. This dominant form of equity work, Bang and Vossoughi argue, deprioritizes or avoids critiques of those workforces or marketplaces and, in turn, takes a “no view or a deficit view of epistemic heterogeneity” (p. 175). Bang and Vossoughi's analysis and critiques of equity work in education align with our view of the dominant equity work in the world of educational improvement specifically; we reiterate, as Bang and Vossoughi do, that there are affordances to teaching students to engage in codes of power, but that such work dominates what equity work has come to mean in the world of improvement.

Bang and Vossoughi argue for more expansive notions of equity that foreground students' multiple ways of knowing and being. Crucially, Bang and Vossoughi argue that meaningfully engaging heterogeneity in learning environments increases opportunities to learn and grants what they call a “transformative agency” to youth that upends “historically powered inequities in education” (p. 184). We draw on this conceptual work to generate a core part of our theory of action: if schools foreground epistemic heterogeneity, then students will be more agentic.

In invoking and elevating epistemic heterogeneity as a priority in CI work, we seek to offer an alternative to the dominant forms of equity-focused improvement work we have described thus far in this paper. We propose that improvement practitioners and researchers work to lead improvement efforts that reorganize classrooms and schools to take up, build on, and make central students' varied ways of knowing.

Develop axiological rigor in improvement work

Axiology is the theory and practice of values, or that which is good and right. We argue that (a) improvement work is never value-neutral, and (b) improvement work that aims to be justice-focused ought to grapple with the theories of values (i.e., axiologies) that constitute improvement work. In conceptualizing axiological rigor, we draw on work from Bang et al. (2015) that conceptualizes axiological innovations in the world of design research and the learning sciences. Bang et al. define axiological innovations as the “theories, practices, and structures of values, ethics, and aesthetics [...] that shape current and possible meaning, meaning-making, positioning, and relations” (p. 1–2). In their work on a community-based design research project focused on improving science learning for urban Indigenous youth, Bang et al. highlight how the research team enacted an axiology rooted in privileging Indigenous ways of knowing—and apprenticing Indigenous youth into those ways of knowing. In their work, two axiological innovations emerged: (1) cultivating relationships in ways that were ethical; and, (2) being answerable to the Indigenous community as university-based researchers. These innovations arose from engagement with emergent tensions stemming from being positioned as academics while working with a community that had historically been and continues to be subject to the violence of colonialism. Through their work and engagement with these tensions, Bang et al. viewed solidarity with the community and “withness thinking” as core parts of their responsibilities as researchers, positioning themselves as “centrally involved in unfolding activity” as opposed to “being outside” (p. 6). This frame for viewing axiologies as being generated, performed, and enacted—moment-to-moment in the work of improving learning environments for youth—served as inspiration for our call to attend to axiological rigor in improvement work that aspires to justice.

We recognize that the translation from community-based design research to the practice of CI is not a clean one. For instance, those leading improvement efforts are far more likely to be those working in schools or school districts than they are to be academics (e.g., Aguilar et al., 2017; Bonney et al., 2024; Carlile and Peterson, 2022; Shepard, 2022). Thus, an axiology and axiological innovation emerging from “being outside” and answerability to students may look considerably different depending on an improvement leader's position relative to the contexts within which they lead improvement work. However, we contend that it is equally important for leaders to grapple with the axiologies that come to be embedded in the aims and theories of action that drive improvement. Leaders can build axiological rigor by interrogating the outcomes toward which improvement efforts are oriented—and determining the extent to which the aims of improving those outcomes are oriented toward equity and, separately, justice.

Humanize minoritized students and communities for whom improvement work serves

Improvement efforts that aspire to center justice ought to interrogate deficit narratives of students, families, and communities and how those narratives shape the focus and practice of improvement work. Deficit frames are rampant and have a long history in shaping work aimed at addressing racial disparities in education (Ladson-Billings, 2007; Valencia, 1997). Improvement scholars have begun to engage and combat deficit orientations in conceptualizing equity-oriented improvement, highlighting that deficit orientations can seep into the artifacts that improvement work produces (Anderson et al., 2023).

As a counter to deficit orientations in the work of schools and schooling, decades of research have surfaced approaches to humanizing minoritized students by drawing on the wealth of knowledge and strengths that minoritized youth have accumulated through their cultures and families (Rios-Aguilar and Neri, 2023). Researchers have generated new and appropriated existing methodological tools in education, such as counternarratives, which surface stories of youth who thrive and succeed despite systems of schooling that are designed to marginalize them, often highlighting the cultural strengths that they bring and enact in their everyday lives (Solorzano and Yosso, 2001).

A continuous improvement for justice ought to not just combat deficit orientations, but also organize improvement work around redesigning systems to center the strengths of minoritized students. Without this orientation, the aim of improvement work comes to focus on closing gaps while appropriating the language of justice. For instance, the first Sandoval and Van Es's (2021) study illustrates how a group of critical teacher educators came to generate an aim statement for an improvement network around preparing teachers to center the strengths of multilingual students. In doing so, they rejected an aim statement that replaced “English language learners” with “multilingual learners” that read, “Improve how teacher candidates support multilingual learners.” Teacher educators remarked that the aim statement still positioned multilingual students as deficit, and cemented as the goal the need to apprentice multilingual students into the English language. This teacher education improvement network, and how teacher educators came to focus on justice, illustrates what it looks like for improvement efforts to organize around lifting up minoritized students' strengths.

We note that there are existing efforts to enact culturally relevant learning and teaching in schools across the United States as a way to begin to center the cultural wealth and knowledge that students bring to school. At the same time, however, these efforts often face barriers and challenges at various levels throughout school systems. Neri et al. (2019) find that a variety of structures and processes come to constrain educators' capacities to enact culturally relevant learning and teaching, and that these challenges come to be expressed as “resistance.” In their work, they reframe this resistance to highlight structural barriers. We contend that CI is well-positioned to address these issues given its focus on systems, but humanizing minoritized students must first be a central practice in improvement work; we interpret that it currently is not.

Such an orientation to students' strengths, rather than seeking to fix them to reduce some disparity in a dominant outcome, places a priority on elevating the comfort and dignity of students, and minoritized students in particular. Rather than peripheralizing their backgrounds and ways of knowing and being, elevating and centering on students' strengths enables students to view schools as comforting places where they can feel dignified in their own ways of knowing and being.

Make critical the empathy work that drives improvement

Empathy work is central to the ostensive features of CI, where empathy is a tool for understanding the current state and the systems that produce problems (Hinnant-Crawford, 2020; Perry et al., 2020). We argue that empathy work in improvement has the potential to uphold and reproduce systems that harm minoritized students, and that a justice-focused improvement ought to make empathy work critical, so that empathy work can make visible the systems of oppression that subjugate, extract from, and other minoritized students in schools. We do not view empathy as a practice that inherently leads to greater justice in improvement work, highlighting past research on how educators develop false empathy and a lack of perspective-taking (Warren and Hotchkins, 2015). Instead, empathy work for advancing justice ought to actively take a critical stance. We draw on Lobb's (2017) conception of what she calls critical empathy to ground our argument. In contrast to what she calls doxic empathy—or mainstream, dominant conceptions and practices of equity that foreground suffering as fait accompli—critical empathy is concerned with understanding the suffering of individuals as unjust and within a frame of moral harm. For Lobb, critical empathy motivates a need to uncover injustices, name moral harm, and work to redress them, as opposed to treating the harm as a consequence. We specifically draw on Lobb's analytic move to uncover differences in interpretation of events. To illustrate the difference between doxic and critical empathy, Lobb uses a hypothetical example of a mother losing her child to disease and two neighbors' empathy practices toward the mother. In it, one neighbor empathizes with the mother with resignation to the challenges that produced the disease, and Lobb offers an interrogation of this response:

“Yes, this is what often happens to us. Life is hard, but this kind of terrible misfortune is the way things always are and will always be.” To this extent, this neighbor's empathy can be said to be completely empathically ‘accurate' in the sense that she knows intimately that and what the grief-stricken mother suffers, and yet also ‘inaccurate' in the sense that it is caught within an interpretive horizon of doxic resignation that distorts perception of what lies at the causal origin of the child's death—and consequently reframes it as a matter of fate, not of injustice.

Lobb then turns to the second neighbor in this hypothetical example and their response to the mother losing her child:

Let us imagine that ‘Neighbor B' has been meeting of late with several other women from the village [...] In the company of these women in her group, she has begun to notice in a new way what of course all of them have always ‘known': the shocking statistics that many more girls than boys die of malnutrition and disease in infancy [...] Against the background of her new collective experiences of group meetings, she looks again at what it means for women and girls to suffer in this way. If, at this moment, empathy and critique come together in a powerful amalgam, a new interpretive horizon may open.

In this hypothetical example and accompanying analyses, Lobb illustrates what it means for two people to interpret and respond to the same event in radically different ways. In particular, Lobb shows how the use of criticality in empathy enables the possibility for change that redresses injustices and moral harm. We elevate this analytic move to argue that empathy work—and in particular what students, families, and communities say as a result of said empathy work—is not value-neutral and is subject to a wide range of interpretations. Insights from students, families, and communities can be interpreted to uphold existing systems just as they can be interpreted to surface injustices and harm. For instance, we imagine some parents, particularly working-class parents, might view that the purpose of schooling for their children is to eventually get a stable job that pays them livable wages. Some improvement practitioners and researchers might interpret this to mean that schools ought to provide clearer pathways to lucrative and in-demand careers while eliminating “waste” in the form of humanities and ethnic studies courses. More critical improvement practitioners and researchers, on the other hand, might generate a different set of responses by interpreting parents' comments as responding to the precarity that capitalism imposes upon them every single day, wishing for comfort, dignity, and agency for their own children beyond their time in schools.

Empathy work within the context of improvement has potential to center justice when engaged in ways that situate the experiences of minoritized students within the sociopolitical context that surrounds schools. Central to our conception of a justice-focused improvement is a concern with taking critical perspectives to the work of understanding students', parents', and communities' experiences, and central to better centering students' comfort, dignity, and agency.

Analyze systems as practiced rather than disembodied

Understanding systems that produce problems is a core tenet of continuous improvement (Bryk et al., 2015; Hinnant-Crawford, 2020). In articulating this core principle, improvement researchers and practitioners highlight that an examination of systems is counter to tendencies in education to blame people, such as educators, families, or even students. In our conception of justice-focused improvement practices, we do not seek to upend this principle; blaming educators, families, and students is counter to the practices we have outlined up to this point. Instead, we aim to refine it to view systems as practiced and embodied rather than disembodied from individual, moment-to-moment action. We return to social practice theory to undergird our argument. In practice theory, structures and individual actions are only separable analytically; in real-world contexts, structure and actions are mutually constitutive. Action (re)produces, modifies, upholds, or upends structure, while structure constrains and enables action, a relationship that constitutes practice (Feldman and Orlikowski, 2011). Thus, we argue that those aspiring to engage in justice-focused improvement ought to center analysis of systems on practices, specifically to unearth the practices that (re)produce injustices in schools. In order to understand how minoritized students come to be peripheralized, harmed, or othered, improvement work ought to focus not on people, but what people are doing that constitute what is traditionally viewed as “the system.”

To make the connection between practice and the work of improving toward justice, we draw on Helen Ngo's (2017) The Habits of Racism, a book that conceptualizes racism as embodied and habituated. In her book, Ngo makes visible the ways that racism comes to be expressed in bodies and through socially constituted habits. For Ngo, racism can be found in bodily gestures, from fidgeting to shifting to moving and sweating, illustrating how bodies come to be racialized. In viewing racism as embodied and habituated in this way, Ngo argues that such bodily gestures, and the schemas and emotions that come with them, come to shape moment-to-moment action, using an example of a white woman who clutches her purse when in an elevator with a Black man. We use Ngo's work on habits, bodily expressions, and racism to elevate the often-unseen ways that injustices and inequities come to be practiced moment-to-moment, interaction-to-interaction. We can envision that this work has implications for how justice-focused improvement practitioners and researchers seek to examine systems of racism, homophobia, or other forms of bigotry in schools. For instance, we imagine that such a frame can be useful for examining how white teachers respond to Black students and Black student behavior in ways that result in disciplinary practices such that teachers express a narrower range of acceptable behavior for their Black students. A view of systems as disembodied from individual action might instead lead improvement practitioners and researchers to focus on, for example, school policies.

A focus on systems-as-practiced can lead improvement practitioners and researchers to do work that is closer to the everyday, moment-to-moment work that produces injustices in schools. Improvement work ought to examine how unjust systems come to be embodied and practiced—and vision what it means to practice systems that instead grant students comfort, agency, and dignity.

We offer five practices of a justice-focused improvement to motivate practical innovations in improvement to better center justice and to critically interrogate and analyze existing improvement work. We reiterate that we view these five practices of a justice-focused improvement as provisional, living, and worthy of contestation; in the discussion section of this paper, we offer ways that improvement practitioners can refine, build on, break, or otherwise improve these practices. We now turn to put these practices to use and highlight how they might be used analytically.

The case of menomonee falls

We illustrate the analytic and practical use for the five practices of a justice-focused improvement using the case of the School District of Menomonee Falls, a suburban school district just outside of Milwaukee. In 2017, the Carnegie Foundation honored SDMF leaders by elevating SDMF as one of its Spotlight on Quality in Continuous Improvement honorees, which sought to recognize leaders who “have demonstrated quality in the enactment of improvement principles and are making real progress on persistent educational problems” (Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, 2017). In the Carnegie Foundation's explanation for selecting SDMF, they cite that the district used continuous improvement to “develop the human capabilities, organizational and structural changes, and system capacities to accelerate systems, school, and student learning.” A prominent feature of SDMF's improvement work concerned its engagement of every interest-holder in the district in improvement efforts; not only were district and school leaders engaged in improvement cycles, but so were service workers, teachers, and students in classrooms. Key outcomes from SDMF's improvement work included increasing student achievement, reducing middle school suspension rates by 63%, and reducing workplace injury claims by half a million dollars.

SDMF's selection as an exemplar of continuous improvement by the Carnegie Foundation—from which the most visible push for the uptake of improvement science in education originated (Bryk et al., 2011)—makes it a compelling case from which to learn. In addition, the large number of public resources available on SDMF's improvement work—in the form of articles and webinars—enables the potential for rich insights to be generated from the case. We chose SDMF as a case to illustrate our practices given its prominence in the field of educational improvement and the sheer number of details shared by its leaders. In this paper, we reviewed a transcript of a Q&A session following a webinar held by the Carnegie Foundation in 2014 (Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, 2014); an article by the Carnegie Foundation and written by Kathryn Baron published on February 3, 2017; a webpage on the Carnegie Foundation webpage explaining why SDMF was selected as a Spotlight Honoree in continuous improvement (Baron, 2017); and a webinar organized by EdWeek on June 4, 2018. These four sets of public artifacts provided us with enough insight to glean where SDMF focused its improvement efforts, what they chose not to focus on, and their relations to the justice-focused improvement practices we have articulated.

We also note some limitations to using SDMF as an illustrative example. First, SDMF serves a majority-white student population, where 85% of students are white and no other racial or ethnic group exceeds 5% (U.S. Department of Education, 2021); this may limit insight into SDMF's improvement work given. Second, and perhaps relatedly, none of the stories we examined of SDMF's work mention their work with minoritized students beyond reducing disparities in suspension rates by race and reducing suspension rates overall; no detail is asked from or given by SDMF leaders about this work, or work with minoritized students more broadly. The lack of stories or exclusion of minoritized students from these stories may well be insight into what SDMF centered and how they attended to issues of race, gender, or other forms of identity in their work; where appropriate, we surface the lack of narratives about minoritized students.

While we offer an examination of SDMF from a critical perspective—which leads to interrogations into how SDMF's improvement work unfolded and, in turn, difficult conversations about what schools and school districts prioritize—we also note that leading change and working in school districts is challenging and constantly evolving. Although we bring a combined two decades of experience in improvement, we have no first-hand experience as leaders of large school districts; thus, we offer critiques and interrogations but do so with humility, recognizing the barriers, tensions, and pressures that district leaders are faced with every single day. Additionally, we offer these critiques not to dismiss the work SDMF leaders engaged in, but to illustrate our aspirations for how improvement work can come to more centrally focus on justice. To the extent that we can, we attempt to situate interrogations into the work SDMF leaders engaged in within the context of broader systems that create the conditions for inequitable and unjust practices in schools. We also recognize that we use and interpret publicly available resources and did not conduct empirical research and data collection on SDMF's improvement efforts; thus, their voice is missing from this paper. Finally, we note that many aspects of SDMF leaders' improvement work aligns with our aspirations for justice, and lift those up as bright spots for the field to engage.

We turn to an illustration of the five practices we have outlined for a justice-focused improvement using the SDMF case. We organize this section of the paper by each practice.

Foreground epistemic heterogeneity

A core problem facing SDMF leaders prior to their uptake of improvement in 2011 was its low achievement rates; in 2011, SDMF was federally designated as being “in need of improvement” as measured by standardized test scores (Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, 2017). By the time it had been recognized as a Carnegie Foundation Spotlight Honoree, it had become recognized as a top school district in the state of Wisconsin and recognized nationally for its increase in student achievement, as measured by standardized tests. These test scores—along with other standardized assessments used by SDFM, such as college readiness assessments—drove a considerable amount of improvement work.

Core to SDMF's improvement efforts on student achievement were the use of common, formative assessments that served as leading indicators for standardized test scores. Corey Golla, then the Director of Curriculum and Learning at SDMF prior to taking over as superintendent, explained:

We've put a lot of time recently into trying to make our assessments that we're doing at the classroom level, the formative assessments, so those quizzes and common assessments are more predictive [of] the large, lagging outcomes. And so the goal is that ultimately, we would like to eliminate as much of the standardized testing as we can because we know we can rely on those classroom assessments to drive our improvement.

Leading indicators are a core tool in continuous improvement that enable educators leading improvement to identify whether they are on track to meet their aims, which are often measured by lagging indicators; focusing on lagging indicators, improvement scholars and practitioners argue, does not enable educators to improve until it is too late (Bryk et al., 2015; Takahashi et al., 2022). Thus, SDMF's implementation of common formative assessments as leading indicators is a central move in continuous improvement work. We interpreted SDMF's use of common formative assessments as leading indicators that were meant to give them insight into whether teachers, schools, and the district broadly were on track to meeting targets for proficiency as measured by standardized test score (or what they call the “large, lagging outcomes”). In particular, we interpreted the phrase “we would like to eliminate as much of the standardized testing as we can” to mean that SDMF had aspired not to lean on standardized test scores as their primary indicators because test results are lagging; instead, we understood this phrase to mean SDMF viewed their common, formative assessments as predictive of how students would perform on standardized tests, thus focusing improvement efforts on those formative assessments.

We have argued in this paper that a focus on standardized test scores as the primary objects of improvement deprioritizes students' ways of knowing, harkening back to Cunningham's (2019) work highlighting how standardized tests act as tools of epistemological erasure. Although SDMF sought to deprioritize standardized tests within the day-to-day of their improvement efforts, their primary leading metrics—common, formative assessments—appeared to be prioritized by their ability to predict “large, lagging outcomes,” in this case, standardized test scores. We did not see evidence in webinar transcripts or other publicly available materials we examined that highlight an alternative or parallel attention to what we and other scholars have been calling epistemic heterogeneity to honor the varied ways of knowing and being with which students come to schools. Relatedly, we did not see evidence of conversations around minoritized students as it pertained to learning and achievement; although this may have been a focus of SDMF, this was not a central part of the public story of their work. In imagining a justice-focused version of SDMF's improvement efforts, we envision that SDMF could have focused its efforts and its measurement system around, for example, whether and how learning environments surface and build on students' knowledge bases; whether and how learning environments help students bring together their cultural identities and their emerging identification with subject matter; or their use of growing subject matter knowledge for the betterment of their communities.

Develop axiological rigor in improvement

We argue, however, that a justice-focused improvement effort can still hold increasing standardized testing as a core outcome, especially given the history of the ways that federal and state policies impose standardized test scores as a central outcome to which schools and districts must attend, an imposition over which educators may have little to no control (Cunningham, 2019). Leaders that aim to center improvement work on justice, and are constrained by external pressures to improve on dominant outcomes, ought to seek to measure and improve on outcomes that foreground epistemic heterogeneity in ways that are parallel to a focus on dominant outcomes.

We conjecture that a central prerequisite to focusing on justice-focused outcomes in parallel is an interrogation into why standardized test scores are being prioritized, and by whom, and whether improving dominant outcomes like test scores is valuable to educators, students, families, and communities, irrespective of the mandates to care about them placed upon schools. This work of interrogating dominant outcomes, and making parallel more justice-focused outcomes if need be, is what we call the work of developing axiological rigor in improvement. In the case of SDMF, we did not see evidence in public materials that leaders interrogated the prioritizing of standardized test scores; however, we did see evidence that leaders engaged with other outcomes that were not standardized test scores. We turn to an exchange in the 2018 webinar with EdWeek:

Interviewer: How do you find the data to measure things like character and critical thinking and not just things like test scores and other things that are fairly easy to get data for?

Dr. c (former Superintendent of SDMF): [...] We are taking a look at the work across the system of the students, you know, in their engagement. If you read the literature on life skills, it's, are they attending, are they participating, are they actively engaging in the process of learning? So we're taking a look at, for our kids who are really struggling, which ones are engaged in which areas and then designing the types of experiences the kids are most interested in to make sure that we're hooking them in. [...] What we've found is, arming the kids with the problem-solving process is more important than figuring out how to collect all of the measures and actually be able to report it in isolated areas.

We interpreted this comment from Dr. Pat Greco as an indication that SDMF also prioritized other, non-dominant outcomes in their improvement efforts, in this case, students' participation, engagement, interest, and ability to engage in problem solving, outcomes and processes that are more compatible with and closer to equity and justice orientations to learning than standardized tests (e.g., Bartell et al., 2017). While we do not have insight into whether their enactments of improvement that focused on these outcomes were rooted in foregrounding epistemic heterogeneity, we recognize that these outcomes are a step toward justice, even if they might not be precisely aligned with the kinds of justice-focused outcomes we have articulated to this point.

Given our limited window into SDMF's work, we do not know whether SDMF internally grappled with how much they valued proficiency as measured by standardized tests, nor do we know whether SDMF engaged in parallel work focused on epistemic heterogeneity. However, SDMF had clearly thought about other outcomes that they do care about alongside standardized test scores and traditional measures of achievement.

Humanize minoritized students and communities

Our work examining public materials of SDMF's improvement work did not surface evidence into whether SDMF sought to combat deficit orientations of minoritized students or communities; additionally, SDMF's work on improving on common formative assessments and, in turn, improve test scores surface that at least much of SDMF's work did not revolve around elevating minoritized students' strengths. We note here that a lack of narratives about minoritized students, families, or communities in SDMF's work might offer some insight into what SDMF viewed as central to their story of improvement. We might interpret the lack of public narratives in public materials as evidence that SDMF leaders may not have centered issues minoritized students face, adults' deficit orientations to minoritized students or communities, or work that elevates the strengths of minoritized students. At the same time, we recognize that SDMF may have focused on and made explicit issues of race, gender, or other forms of identity internally and did not find productive or otherwise have the capacity to share those conversations or those efforts publicly. Additionally, we recognize that, in many of the public materials, it was not SDMF leaders who were determining the questions that drove the sharing of those stories, but instead, these questions were asked by journalists, organizations such as the Carnegie Foundation, and audience members.

This lack of evidence to determine how SDMF did (or did not) humanize minoritized students—in the form of combating deficit orientations or lifting up minoritized students' strengths—raises questions about what data are needed to gain insight into practices like this one. We address this in our discussion and ideas for future research.

Make empathy work critical

Central to SDMF's stories of their improvement work is student, family, and community feedback. In particular, SDMF expended significant energy, time, and resources to create routines to both solicit and respond to student, family, and community feedback in ways that were timely and regular. Dr. Pat Greco explains on the EdWeek webinar in 2018:

When we look at our improvement cycle, we look at improvement in 45-day cycles at our school in division levels. Students give our classroom teachers feedback about every 10 to 15 days, ideally, where they're reflecting on what's working for them and what help they could get in order to have their learning outcomes achieved in a better way. We focused heavily on feedback from our stakeholders, our students, our staff members, our community members, our parents, and we have cycles of feedback, again, that our partnership with Studer helps us with. We measure our culture of our feedback as well as the actions that we're going to be taking based on that feedback. [We do focus groups] a couple of times a year with our eighth graders. We run them four times a year at the high school level, and then our target is also to start at the fifth-grade level as well going forward.

SDMF leaders built robust, regular, and routine opportunities for students, families, and community members to give feedback to and on teachers and adults and generated cycles to learn from and respond to them. Rather than a system in which adults rely on students and families to provide feedback on their own volition, SDMF sought to instead reposition them such that soliciting their feedback was part of the normal operations of classrooms and schools. Given that these routines were implemented across schools, we can assume that minoritized students' feedback were also taken up as part of these routines. We interpreted SDMF's routinization of feedback as a form of structured, routine empathy work that sought to regularly and frequently incorporate student voice, and that the deliberate and routine action taken to address student and community feedback as a crucial step toward justice.

However, we also surface evidence of how SDMF managed contradictions between student and community feedback, on the one hand, and their perceived purpose of schooling on the other. When asked about how SDMF found financial resources to fund all staff to be trained in continuous improvement, Corey Golla remarked:

We were really starting to look at the return of investment on curricular material, trying to understand some of the roles, but we also made a lot of tough decisions on programming and aligned our programs at the secondary level, especially with the hot career fields and took a very hard look at some other programs that, you know, maybe were passion points in our community or among our students but weren't necessarily leading towards viable careers for students, and eliminated some strands and that resulted in some savings. That is the commitment in this work, is if you're going to expect this from people, you have to have the resources there to support them and the coaches, and that requires some tough decisions early on.

SDMF eliminated programs that were “passion points” among community members and students in order to prioritize what they called “hot career fields,” a move we interpreted as prioritizing the needs and desires of local, regional, and national labor markets over students' and community members' needs and desires. We resurface work from Domina et al. (2017), Stovall (2018), and Cunningham (2019) that highlights how systems of schooling and schools themselves are currently organized to apprentice students into capitalism, treating them primarily as bodies to be produced readymade for labor markets. We interpreted the elevating of preparing students for “viable careers” over programs that students and community members found valuable as upholding that purpose. Of course, we note significant gaps in our understanding of this story that might upend our interpretation. For instance, we do not know which programs were identified as not leading to so-called “viable” careers, nor do we know which communities were advocating for those programs and for what purpose. We also have no insight into the specific processes that SDMF leaders engaged in to identify which programs were to be ended to cut costs. Given the evidence we do have, however, we interpret that SDMF's empathy work shared in public spaces did not take a critical stance that enabled them to see and upend systems of oppression that subjugate minoritized students in schools.

Analyze systems as practiced and not disembodied

Central to SDMF's improvement work was shifting educator practice to surface and respond to student feedback, as well as to engage in improvement work. When asked how SDMF leaders garnered buy-in and participation from employees of the district—from service staff to teachers to district leaders—Dr. Pat Greco remarked:

The research indicates that you actually have to change behavior before you change beliefs. The biggest difference here is that we are building the infrastructure around development, growth, and skill building. Our teachers actually know how to change behavior. Then they reflect on the process and their learning during coaching. The process is showing the change in adult behavior. Our teachers implementing most deeply are demonstrating improved student performance results.

SDMF leaders sought to focus on shifting what adults did and developed routines that teachers, school staff, and district staff engaged in to change what they did in their daily work. We interpreted this orientation to behavior and practice as moving closer to the practice of focusing on systems as practiced in order to address injustice when compared to a focus on systems and routines divorced from individual action. Importantly, SDMF leaders were careful not to blame individuals for their shortcomings. Dr. Greco remarked:

When you think about it though, one of the core principles around quality from Deming is to drive out fear. You focus on improvement, support, learning, and target growth. You identify the expectations for performance. You expect action and commitment, but you drive it with heavy support. People should know that we will be there to work with them. If people are deciding not to engage, that is really a non-compliance issue. You do not drive culture around that fear.

The focus on driving out fear, as Dr. Greco called it, highlights how SDMF leaders sought shifts in individual action and practice without blaming individuals and while providing them with adequate supports to make those shifts. We interpret this as moving closer to the justice-focused practice of analyzing systems as practiced and embodied by individuals rather than disembodied. We note that this example, and SDMF's public stories broadly, are missing narratives about how they sought to shift practices that generated racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, ableism, and attacks against other forms of identity, a core feature of this justice-focused practice. At the same time, we view the move to focus on individual action as moving closer to justice because it enables a culture that prioritizes shifts in individual adult behavior and actions, rather than shifts in resources or “structures” divorced from actions. Such a shift can be paired with a critical lens—one that is constantly attentive to minoritized students' experiences and the sociopolitical context that shapes those experiences—in order to move us closer to understanding how bigotry comes to be enacted in schools. Driving out a culture of fear, for instance, can enable practitioners to be honest about how their own day-to-day actions come to position Black and Brown students as peripheral while privileging dominant ways of knowing and being. Thus, while public narratives about SDMF do not attend to issues of identity such as race, we view leaders' work in shifting adult behavior and practice as a necessary, albeit insufficient, move in improving toward justice.

We have illustrated the potential use and possibilities of our five practices for a justice-focused improvement using the case of the School District of Menomonee Falls and leaders' work in making improvement a central approach to their day-to-day operations. We reiterate that our use of publicly-available documents and artifacts comes with shortcomings that limit our insight into whether and how SDMF sought to center justice in their work. For instance, while SDMF leaders drastically reduced suspension rates and disparities in suspension rates by race, the publicly-available stories do not offer detailed insight into how they did so, surfacing questions about the work they did to address those disparities. Having interrogated the case of SDMF using our five practices, we return to connections we make in the literature on improvement and justice and offer potential directions for future improvement research and practice that can build on our vision for a justice-focused improvement.

Discussion and directions for future research and practice

We set out to articulate a justice-focused improvement by highlighting the outcomes and practices that we conjecture constitute improvement work that moves the field closer to educational justice. In so doing, we have interrogated dominant ways of doing improvement work, including the outcomes of improvement, drawing inspiration from critical scholars in other fields as well as critical scholars engaged in design-based and participatory research. We sought to illustrate these five practices by using them to understand the public case of the School District of Menomonee Falls, which has been held up as an exemplar for the uptake of continuous improvement in education.

We reiterate that the five practices we articulate are meant to be provisional, subject to explication, refinement, modification, contestation, and fracturing. We do not intend them to constitute a framework and guide that should govern all improvement practice, but instead, practices that are generated from our own work, grounded in literature on justice in work on improving education broadly, and subject to testing and revision. Given that, we have identified several potential directions for future research, as well as directions for practice—in particular, capacity-building for the field.

First, we suggest a need for richer, detailed cases of improvement work, whether that improvement work is justice-focused or equity-focused or both. Our examination of the SDMF case revealed the additional insight we could glean if more data were available on how the district sought to improve. We argue that making the practice of improvement work visible in this way enables insights into how improvement efforts are or can be more oriented toward justice, in line with previous work that highlighted the value of attending to power in the practice of improvement (Sandoval et al., 2024). Attempts to document and share the daily work of improvement in schools is beginning to emerge, such as Bonney et al.'s (2024) edited volume consisting of cases of practitioners documenting their improvement work in schools and districts. We contend that more and more detailed cases are necessary in order to more precisely articulate the work of centering justice in improvement, as well as to build the field's capacity to center justice in improvement efforts.

We contend that orienting improvement toward justice requires shifts in the practice of improvement, as we have articulated here. Closely examining and lifting up the work of justice-focused improvement efforts can help to explicate, modify, add to, or radically change the practices we have articulated here. Much like design-based researchers have generated practical and axiological innovations in efforts to center justice (e.g., Bang et al., 2015), improvement researchers and practitioners ought to consider practical and axiological innovations in improvement efforts. Additionally, examining the work of equity-focused improvement efforts can help to identify possible shifts in practice the field can make to better center justice alongside equity, or can help surface new tensions that emerge when grappling with equity and justice issues together and at once.

Second, we imagine these practices might be useful for the development of improvement practitioners' capacity to center justice in improvement efforts. Our focus on practices was driven, in part, by a need for the field to articulate the kinds of capacities we ought to be building for improvement, responding to Peurach et al.'s (2022) volume in which they articulate capacity-building as a priority for the field. Focusing on practices can both generate scholarly insight that pushes our conceptions of what justice looks like in improvement, as well as articulate the specific capabilities that ought to be developed for those learning improvement and seeking justice. For instance, those responsible for developing systems improvement leaders (e.g., those teaching in Ed.D. programs) may consider designing activities that develop students' capacities to prioritize and organize improvement toward justice-focused outcomes, such as building on Black students' strengths in classrooms.

Our paper sought to articulate a conceptual and analytic distinction between improvement for equity and improvement for justice so we can begin to generate what a justice-focused improvement can look like in theory and practice. We aimed to push for a turn to justice in improvement efforts, in line with and inspired by the same turn that more mature, more established approaches—such as design-based research—have made in years and decades prior. Our hope is to foster a conversation and generate possibilities for critical scholars and practitioners to reshape what it means to do improvement work. We hold at the center of our arguments the question, “improvement for what?” to critically interrogate what the field is currently improving toward and what we aspire the field to improve toward. We aspire to articulate and enact an improvement rooted in our visions for schools that prioritize the comfort, dignity, and agency of all students, and Black, Brown, LGBTQ+, disabled, and other minoritized students in particular.

Data availability statement