- Department of English Language and Literature, College of Arts and Applied Sciences, Dhofar University, Salalah, Oman

The tertiary education environment requires students learning English to acquire and develop oral and speaking competencies since they are expected to use communication skills in diverse contexts that serve various purposes. This study investigates the efficacy of clustered digital materials, including TED Talks, digital posters, short films, and newspaper cartoons, in enhancing the English-speaking proficiency of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners in an Omani higher learning institution. Employing a mixed-methods approach, the study analyzes data from 37 undergraduate EFL students in digital material-aided situational English classes using statistical tests and qualitative descriptions. Data were collected from participants’ questionnaire responses, semi-structured interviews, and teacher notes. The study reveals that participants preferred incorporating digital materials that required high metacognitive skills and enhanced critical thinking as confirmed by a paired-sample t-test (p < 0.05). Results also demonstrate that participants rated posters as the most desirable digital material, improving speaking and motivating interaction. The findings of the study have important implications for teachers to adopt unconventional pedagogic strategies for coaching, scaffolding, and supporting students while implementing digital materials in conversation classes. This result implies that clustering digital materials in planning pedagogic situational English activities provides language learners with diverse opportunities to collaboratively practice speaking and improve oral and communication competencies.

1 Introduction

In university education, learning a second or foreign language well and mastering its use successfully and effectively in different communicative situations and acts is the ultimate goal of language teaching (Cook, 2003) and an objective every learner wishes to achieve. Advancement in language learners’ linguistic knowledge and skills is referred to, according to Richards and Schmidt (2002), as “language proficiency” which suggests “the degree of skill with which a person can use a language, such as how well a person can read, write, speak, or understand language” (p. 292). Successful language learning discernible in a high level of comprehension and fluency is determined by the degree of command a learner attains in the four language skills and the ability to use the language and understand other users as well. However, a fundamental component in developing language proficiency is mastering speaking and oral communication skills as a main language sphere that influences learning and develops other language domains (Syrja, 2011). Previous research on language learning suggested that “speaking usually involves two or more people who use language for interactional or transactional purposes” (Hebert, 2002, p. 188). Accordingly, successful language use driven by linguistic intelligence involves the ability to manipulate the productive speaking domain to influence the situation, convey nuances of meanings, and achieve a variety of goals (Haynes and Zacarian, 2010).

The recent proliferation of English and its triumphant dominance in the international arena, coupled with great technological advances and computer-mediated information and communication, have exerted considerable influences on the global linguistic landscape and EFL education (Crystal, 2002; Salih and Holi, 2018). The global fame the English language is enjoying has made it one of the most desirable languages to learn, and, as such, its learners seek to master it for a variety of reasons (Cook, 2003). For this journey of learning to be a pleasant experience, ESL/EFL students need not only to develop linguistic knowledge but also master English speaking and oral communication skills and practice effectively within the classroom environments and beyond. Throughout the process of learning the English language, improving learners’ oral proficiency is more inhibiting than the attainment of educational outcomes which aim to improve other skills in foreign language education (Asratie et al., 2023; Goh and Burns, 2012; John and Yunus, 2021). Furthermore, it is widely recognized that learners’ speaking fluency and effective oral communication are critical since they are regarded as key components in students’ academic and professional growth.

Thus, globalized English has brought new realities to language classrooms (Salih, 2017; Tseng and Yeh, 2019; Salih and Holi, 2018) and challenged learners who aspire to acquire and develop excellent oral communication and speaking abilities to perform well during job interviews, job training, and other interactional contexts (Bailey and Nunan, 2004) and become interculturally responsive to other global users of English (Alharbi, 2024; Omar and Salih, 2023; Wu et al., 2024; Salih and Omar, 2021, 2023). Mastering speaking competencies and effective oral communication skills is central to learning and use of English because it is necessary for ESL/EFL learners’ oral presentation and social interaction (Thornbury, 2005; Brown and Yule, 1983), knowledge of speech functions (Richards, 2008) development of different speaking engagement strategies (Goh and Burns, 2012) as well as awareness of and response to different communicative speaking environments (Harmer, 2007).

Teaching situational English transcends the use of surface mechanical dialogues and imitative conversational instances to deeper contextualized levels which challenge students’ speaking performances and place them in genuine learning experiences. Effective teaching that aims to develop EFL learners’ speaking performances and communication skills should invite and facilitate the implementation of unconventional pedagogic styles that teach students how to communicate effectively. Given the accelerated progress in “smooth computer-mediated communication as a common phenomenon among speakers of Englishes” (Salih, 2021a, p. 22), and as English language learners spend much of their time accessing various Internet-based materials and sources, teachers can utilize the affordances of digital materials to enhance their students’ oral communicative skills.

In parallel with technological advancement, EFL education has witnessed a gradual improvement in innovative teaching methods that aim to enhance learners’ speaking competencies by harnessing in available applications, CALL tools, as well as multimedia digital resources (Bonsignori, 2018). The majority of EFL language teachers recognize the importance of speaking skills for their students and understand the need to adapt their teaching strategies to address the glaring gaps in their students’ speaking abilities for several reasons related to EFL learners’ poor speaking performance, lack of motivation to speak in the classroom, passive role towards enhancing their autonomous learning, as well as inability to communicate effectively in different situations. However, very few instructors know how to channel their teaching efforts towards a genuine improvement in students’ communicative skills (Goh and Burns, 2012). Thus, enhancing EFL students’ conversational skills becomes better supported with an orchestrated implementation of clustered digital materials that afford an interactive learning atmosphere and more effective teacher support.

The present study aims to examine the impact of using a diversified blended pedagogic approach to improve the speaking performance of EFL students. The treatment was based on the application of clustered digital materials including TedTalk content, digital posters, short films, and newspaper cartoons in the EFL classroom to improve the English oral communicative performance and conversational abilities of students in different situations and contexts. This study is significant because, apart from a few studies by leading applied linguists (Goh and Burns, 2012; Nunan, 1991, 1999, 2003; Richards, 2008), most recent studies on developing EFL learners’ communicative speaking skills call for a facilitating role by EFL instructors in implementing the pedagogic models without providing a succinct delineation of the used pedagogic interventions (Asratie et al., 2023; Tseng and Yeh, 2019). Additionally, few studies investigated the improvement of speaking skills among Arab EFL undergraduate learners (Al-Ghamdi and Al-Bargi, 2017; Al-Jamal and Al-Jamal, 2013). The study was guided by the following questions:

1. What challenges and improved areas were perceived by the students before and after the treatment respectively?

2. How effective is the use of digital materials in enhancing EFL learners’ conversation skills?

3. Which is the most perceived significant digital material implemented in the speaking classroom?

4. What is the role of pedagogies in the effective application of digital materials to improve EFL learners’ speaking competencies?

2 Literature review

2.1 Speaking proficiency priorities and challenges

Although EFL education should pay equal attention to learners’ four skills (Omar, 2021; Salih, 2021b; Ud Din, 2023), speaking skills have gained an increasing importance among EFL language teachers and learners given the status of English as “an international medium of communication” (Tseng and Yeh, 2019, p. 145) that entails constant improvement in language users’ speaking proficiencies to contribute to their academic and professional development (Salih and Omar, 2022a). The globalization of English and its pervasiveness in cross-disciplinary academic and professional domains have created an urgency for EFL learners to expand their oral communication proficiency (Nunan, 2003). Foreign language teaching in the twentieth century valued “the supremacy of the spoken language over the written language” (Cook, 2002, p. 327) and indirect teaching methods inspired by notions such as task-based teaching, audiovisualism, communicative language teaching, audiolingualism, and other pedagogic approaches.

Until recently, EFL teaching has continued to focus on developing learners’ writing skills while neglecting their speaking proficiency (Goh and Burns, 2012; Nunan, 1991; Nunan, 2003). According to Nunan (2003), EFL learners achieve a deeper understanding of the target language and culture and “foster a positive attitude toward communication in it by developing their basic ability for practical communication such as listening or speaking skills” (p. 600). The growth in prioritizing speaking as an indispensable proficiency in EFL teaching and learning coincided with technological advancements that have provided unconventional treatments to address language learners’ underperformance in speaking competencies.

Developing learners’ speaking skills in a way that empowers them to interact and communicate effectively with target language users is one of the intractable challenges facing EFL instructors (Namaziandost et al., 2020) because a linguistically competent language learner does not necessarily have the same level of competency in speaking performance and oral communication (Bergil, 2016). One of the hindrances facing EFL instructors in improving students’ speaking skills is the lack of experience and evidence regarding the most appropriate pedagogical approaches for improving their students’ oral communication skills. Hence the significance of exploring students’ perceptions about different resources that can reinforce EFL learners’ speaking practice and performance (Tseng and Yeh, 2019).

Any improvement in EFL learners’ speaking competencies requires a departure from conventional teacher-focused pedagogical methods to learner-centered approaches (Ellis, 2003; Ellis et al., 2019; Benson and Voller, 1997; Benson, 2000; Benson, 2001; Benson, 2004; Nunan, 1991, 1999) that provide learners with myriad opportunities to use spoken language in a meaningful and communicative manner. The literature on improving EFL learners’ speaking skills addressed the value of pedagogic approaches that promote learners’ autonomy and engagement with speaking tasks whether inside or beyond the classroom. The contemporary pervasiveness and incessant advancement of technological tools and affordances have facilitated the urgent transformation to self-learning and student-centered teaching strategies which converted the implemented teaching models to flipped classroom settings that implement indirect teaching approaches away from old-fashioned, direct instruction.

Flipped classroom approaches improve language learners’ skills (Leis and Mehring, 2017; Li and Li, 2022; Loucky and Ware, 2017), particularly speaking competencies, due to the abundance and availability of technological resources, the practice-driven nature of speaking enhancement activities, and the irrelevance of conventional teaching methods to activities that aim at promoting learners’ speaking skills. According to flipped classroom methods, students explore the learning materials off class time, while classrooms develop into engaging workshops that involve students in active collaborative learning. Nonetheless, this approach may not be applicable to all educational environments (Al-Ghamdi and Al-Bargi, 2017) as it requires highly motivated learners and well-trained instructors who are patient enough to design the instructional materials and activities for use both within and outside the classroom.

2.2 Indirect speaking-enhancement approaches

Studies which researched the improvement of speaking skills among EFL learners investigated the role of avant-garde educational strategies that can be classified into three approaches. The first approach adopts indirect pedagogic methods that contribute to the improvement of language learners’ oral and communicative competencies such as telecollaboration (Beauvois, 1997), cooperative learning (John and Yunus, 2021; Salih, 2013; Nunan, 1991), technologically mediated collaborative learning (Li and Li, 2022; Salih and Omar, 2020; Salih and Omar, 2021), role play (Yen et al., 2015), storytelling, peering, grouping, games and others (Alzboun et al., 2017). The second approach benefits from harnessing educational speaking technological tools and applications (Asratie et al., 2023; Godwin-Jones, 2009; Golonka et al., 2014), and the third approach utilizes multimedia Information Communication Technologies (ICTs) such as social media (Donny and Adnan, 2022) and content creation/distribution/sharing platforms (John and Yunus, 2021).

The most prominent indirect pedagogic strategies used by EFL instructors to improve learners’ oral proficiency are role play and cooperative learning. Role play is a student-centered effective teaching strategy that enhances EFL learners’ oral competency (Alzboun et al., 2017; Yen et al., 2013) since it encourages learners to imagine different scenarios and use diverse speech acts in performing communicative speaking tasks. This strategy improves the students’ levels of motivation and interactivity and allows them to play an imaginary role in a variety of pragmatic and linguistic contexts away from the limitations imposed by criteria such as linguistic and lexical accuracy. Nonetheless, imaginary scenarios lack the effectiveness of authentic contexts which activate higher order competencies and skills. Additionally, role play is most appropriate for mediocre language learners.

Cooperative learning approaches are pedagogic methods which invest in the joint work of a few students working as a team to complete different tasks and, therefore, improve their language skills. Numerous studies confirmed the effectiveness of cooperative learning in enhancing learners’ speaking skills (John and Yunus, 2021; Goh and Burns, 2012). Nunan (1991) observed that “learners … exploit a great range of language functions when working in small groups as opposed to teacher-fronted tasks” (p. 51). According to Namaziandost et al. (2020), cooperative learning “stresses active cooperation between students of diverse abilities and background… and indicates more promising student outcomes in academic performance, social behavior and effectual progress” (p. 3). This creates opportunities for peer-to-peer interaction and feedback (Salih, 2013) which enable students to “negotiate meaning, gain multiple perspectives, refine their original understanding, and improve their skills” (Tseng and Yeh, 2019, p. 146). Goh and Burns (2012) believe that “Teachers should, therefore, encourage learners to support one another’s speaking development, not just as communication partners in a speaking task, but also as learning partners who share their learning plans and goals” (p. 6).

Indirect teaching strategies design poorly structured activities that may enhance learners’ confidence, autonomy, and speaking proficiency while lacking the potential of educational technologies. Buckingham and Alpaslan (2017) pointed out the limitations of developing the learners’ speaking competence in the classroom as language learners show reluctance and lack of motivation to engage in oral communication activities, which indicates the need to create asynchronous speaking practice opportunities in flexible environments characterized by low levels of anxiety. The authors propose designing out-of-the-classroom speaking tasks to address the needs of children EFL learners whereas “synchronous computer-mediated speaking tasks are likely better suited to learners of higher proficiency levels due to the higher cognitive load involved in real-time communication” (p. 26). This suggests that exploratory or empirical studies which address the development of foreign language learners’ communication skills should consider not only the age of learners but also the level of their proficiency as it plays a decisive role in determining the treatment to be employed by instructors.

With the continuous technological advancement that enhances foreign language learning, particularly in the EFL context, it has become necessary for teachers to adapt their pedagogic approaches including “their teaching strategies or…activities to most effectively utilize available resources” (Golonka et al., 2014, p. 70). Technological applications and digital materials have left a ubiquitous impact on foreign language learning everywhere thus emphasizing the efficacy of modern technologies for better L2 learners’ engagement with the educational process.

2.3 CALL speaking improvement tools

Towards the end of the twentieth century, the use of educational technologies to enhance EFL learners’ speaking skills emerged with the rise of Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL). The advancement in educational speaking technologies appeared in the form of Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) tools, Natural Language Processing (NLP), Speech Analysis Software (SAS) and Simulated Speaking Applications (SSA) like Spoken Dialog Systems (SDS) that help learners to perform oral interactive tasks and receive feedback from animated agents on their performance (Godwin-Jones, 2009; Golonka et al., 2014; Sydorenko et al., 2019). Godwin-Jones (2009) remarked that computerized speech training is more effective than classroom speech because it provides learners with the opportunity of customized practice in terms of time and speed parameters. Furthermore, learners practice in a stress-free learning environment adaptable to their needs and progress; and the data generated by learners provide valuable resources for the purpose of research on further improvements in software functions and approaches to speech training.

Advancements in speech improvement technological tools materialized in terms of structured practice opportunities, customized feedback on learners’ input, and other features. Yet, it was necessary to achieve further progress for a more idealized training that improves learners’ “communicative ability with natural speech” (Godwin-Jones, 2009, p. 4). Earlier speech training tools for CALL purposes utilized fixed templates and speech patterns matching, which was conducive to limitations due to lack of accuracy, inability to recognize non-native speakers’ content, ineffectiveness in processing natural speech as well as complexity and lack of affordability for language learning programs. However, recent developments in CALL systems made them more intelligent and capable of storing a large volume of speech patterns which provide speech analysis and effective feedback and training. Recently, speech improvement technological tools witnessed further innovations by integrating them with multimedia videos to extend their applications to real-life situations and discourse use in varied contexts.

2.4 Multimedia digital resources

Although CALL technologies provide language learners with diverse opportunities to promote their speaking skills, one limitation of ASR, NLP, and SSE tools is that they do not apply to all social interaction situations which test the pragmatic competence of language users (Sydorenko et al., 2019). Furthermore, technological applications and tools lack the authenticity and multimodal intervention of ICTs. Social media platforms, virtual gaming, electronic content distribution platforms, and other digital resources provide materials that have left a ubiquitous impact on foreign language learning since they play a vital role in motivating foreign language learners and building their autonomous learning endeavors. An example of content-sharing ICTs is TED-Talks which provide rich audiovisual resources with diverse authentic content to improve EFL learners’ oral competencies including verbal and non-verbal oral communication and presentation skills (Sailun and Idayani, 2018; Salem, 2019).

Bonsignori (2018) believes that enhancing learners’ use of situational English requires exposing them to multimodal materials, visual for instance, since effective language production, verbal or nonverbal, exceeds instructing students about direct communicative norms and necessitates a more profound treatment of discourse-related challenges such as cultural and pragmatic considerations. Visual materials have an educational value as an indirect EFL teaching method. One example of visual materials used in EFL teaching is posters, both conventional and digital, whether they are produced by students or used to expose them to extracurricular teaching materials. Very few studies researched the educational importance of posters emphasizing their usefulness in facilitating the effective and prompt expression of ideas, stimulating learners, creating a vibrant class environment, scaffolding learners’ critical thinking and improving their reading, writing and speaking skills (Ahmad, 2019; Salih, 2021b).

According to Kress and van Leeuwen (2001), multimodality coincided with breakthroughs in technological tools and accelerated access to digital resources and content which facilitated the manipulation of diverse communication and self-expression modes. Therefore, harnessing visual and aural materials in language teaching, such as films and videos, has gained growing importance since they are characterized by authenticity and affordability in improving learners’ skills including vocabulary building and adopting pragmatic strategies in producing meaningful verbal and non-verbal content. “This allows them to see how paralinguistic elements are used in different contexts and cultures, thus also broadening their intercultural communicative competence” (Bonsignori, 2018, p. 2).

Literature on enhancing EFL learners’ speaking and oral communication skills using digital materials underlined the value of free-access audiovisual materials as valuable resources. John and Yunus (2021) reviewed recent academic research discussing the impact of social media on improving speaking skills. The reviewed studies researched the potential of “videos through YouTube, BBC, VOA and TED Talks to get the students to practice speaking skills after watching videos where they could contextualize the language that they had acquired” (p. 12). These studies listed several reasons behind the obstacles facing learners in enhancing their oral expression skills including poor language skills, demotivation, anxiety, low self-esteem, the inability to develop one’s ideas, limited exposure to target language materials as well as ineffective pedagogic approaches. While scaffolding students’ engagement throughout the learning process (Goh and Burns, 2012), teachers can surmount such challenges by utilizing various strategies that create an interactive setting such as the use of cooperative learning methods and social media platforms. The integration of social media with the EFL classroom can “improve teachers’ creativity and enhance their teaching procedures” (John and Yunus, 2021, p. 13).

The useful functions and applications of multimedia resources have continued to confirm the need to integrate digital content with EFL education for an active engagement of learners with resourceful digital materials and guaranteed achievement of course learning outcomes. This practice highlights the notion of digital media literacy which comprises the learners’ and instructors’ skills to utilize, analyze and reflect on the usefulness and impact of digital resources in communicative encounters and social interaction situations (Cannon, 2018; Frechette and Williams, 2016; Hidayat et al., 2022). Reflection in action is an indispensable practice by learners and instructors while experimenting novel educational resources or methods (Salih and Omar, 2022b). The utilization of digital resources in EFL classrooms contributes to positive transformation towards autonomous learning models which redefine the role of an EFL instructor as “content facilitator, advisor, co-learner, assessor, or resource provider… maximizing student’s opportunity to be independent learners” (p. 10). Thus, instructors are invited to re-evaluate their role in exploring novel, more engaging teaching methods and media.

2.5 Literature gaps

The literature on improving EFL learners’ speaking competencies lacks a clear description of instructors’ role in facilitating the learning process. It is important not to overlook the significance of instructors’ feedback in any educational process. A notable shortcoming of empirical studies that experimented the effectiveness of indirect teaching strategies such as harnessing technology, cooperative learning scenarios as well as other methods to enhance language learners’ speaking skills is that they did not provide a clear description of instructors’ pedagogies in implementing the selected educational model.

These studies de-emphasized teachers’ pedagogic interventions because they are no longer the source of knowledge and this confines their role to that of a facilitator (Asratie et al., 2023). In Namaziandost et al. (2020), the teacher’s role was limited to organizing students in groups, providing them with the task (reading task or asking a challenging question), as well as preparing the post-test. There was no mention of the instructor’s intervention in the form of feedback or incidents of student-teacher interaction. This goes contrary to approaches of earlier research on the topic. Goh and Burns (2012) drew a distinction between students’ ability to speak and their competence to communicate effectively with language users observing that “while learners do a lot of talking in class activities, there is often insufficient teaching of speaking as a language communication skill” (p. 2).

Speaking has two functions: to provide information in the form of oral presentation and to interact with others socially in the form of conversation (Brown and Yule, 1983), and these two purposes require distinct sets of skills. ‘Talk as transaction’ requires speaking clearly in situations where the priority is message accuracy rather than the interactive relationship between interlocutors. Examples of this talk include asking and answering questions (ordering food, enquiring about directions, answering questions by instructors, etc.). On the other hand, ‘talk as interaction’ serves a social purpose to build or maintain a relationship. Richards (2008) extended speech functions to the new dimension of talking as performance. This speech function is closer to written discourse in that it has a predictable structure.

According to Richards (2008), teaching speaking needs to be guided by numerous pedagogical considerations regarding speech functions, the type of activities, phases of implementation, language support, resources, expected performance level and timely feedback. Goh and Burns (2012) proposed a pedagogical model to engage language learners in fruitful speaking practice addressing their cognitive and metacognitive needs and taking into consideration the three factors in a successful educational process: instructors, students, and teaching materials. The materials used in teaching speaking should show variation in “form and purpose” (p. 5) and provide a variety of contextualized scenarios, model spoken content to improve students’ linguistic knowledge, and content that nurtures learners’ metacognitive skills. The authors’ proposed model functions in a cycle of pedagogical steps implemented via various activities. These steps include focusing on learners’ attention, providing a plan for guidance, implementing a speaking exercise, focusing on linguistic and discourse components, repeating tasks, guiding learners’ reflective practice, as well as scaffolding and feedback.

Improving English speaking skills among EFL learners studying at Arab universities is one of the challenges reported by EFL learners (Salih, 2017), and it can be attributed to several limitations such as class size, the application of conventional teaching methods and the nature of assessments and teaching environments. Teacher-centered classes that prevail in Arabic-speaking countries (Fareh, 2010) encourage learning the language as a system or rules and patterns rather than a means of communication and expressing ideas, which is why it is not uncommon for an EFL learner to reach an advanced level in terms of vocabulary and grammar use without being able to construct meaning while interacting with others (Salih, 2017).

Al-Ghamdi and Al-Bargi (2017) concluded that the application of technologically enhanced unconventional instructional method did not leave a noticeable impact on the speaking skills of EFL learners in Saudi Arabia. Similarly, Al-Jamal and Al-Jamal (2013) deduced that the employment of outdated EFL curricula and conventional teaching methods did not respond to the communicative speaking improvement needs of EFL students in certain Jordanian universities. Encountered impediments included lack of learners’ motivation to implement self-learning models beyond the classroom setting, the large number of students inside EFL classrooms, ineffective teaching methods as well as exaggerated and dogmatic focus on fixed educational content while neglecting authentic communicative situations.

Alzboun et al. (2017) discussed the effect of role-play on the speaking performance of Jordanian EFL tenth-grade students. Bergil (2016) observed that there is a relationship between EFL students’ poor speaking skills, on the one hand, and course content, and classroom activities, as well as instructors’ reconstruction of course materials, on the other hand. The study emphasized the need to revise classroom pedagogies that aim to develop EFL learners’ speaking skills in different contexts and situations. Also, the study confirmed the necessity to understand learners’ expectations by language instructors and vice versa while introducing blended speaking-oriented activities inside and outside the classroom.

These findings imply that improvement of EFL Arab learners’ speaking performance requires the implementation of a mediated pedagogic approach which neither retains the conventional teaching approaches nor adopts drastic changes in the implemented instructional methods while implementing learner-centered, technologically enhanced pedagogies. The present study is significant based on the realization that adopting unconventional pedagogical strategies based on the application of digital materials and innovative teaching styles to enhance EFL learners’ speaking performance is imperative. Moreover, the internationalization of English coupled with the speedy growth of computer-mediated information necessitates exposing language learners to digital information systems and raising their awareness about the significance of language learning and effective oral communication and speaking skills within the classroom and beyond.

3 Methodology

3.1 Study design

The present study incorporates mixed methods in which both quantitative and qualitative approaches were used to collect data from EFL Omani undergraduate learners about their experience with the affordances of clustered digital materials in enhancing oral communication and speaking skills. The methodological approach involves the use of a statistical validation test and qualitative description of data. The aim behind using the statistical test method is to investigate the impact of the intervention on students’ speaking skills and validate its statistical significance. On the other hand, descriptive qualitative method aims to assess whether the impact is positive and identify the most effective type of digital materials used. The study employs mixed approaches in the sense that mixing qualitative and quantitative methods is a means of understanding research problems by combining the strengths of both approaches (Creswell and Creswell, 2018; Creswell, 2015; Teddlie and Tashakkori, 2009). The recent growing trend to combine qualitative and quantitative approaches in academic research has given mixed methods popularity among researchers. According to Given (2008), the term “Mixed methods is defined as research in which the inquirer or investigator collects and analyzes data, integrates the findings, and draws inferences using both qualitative and quantitative approaches or methods in a single study or a program of study” (p. 526).

3.2 Participants

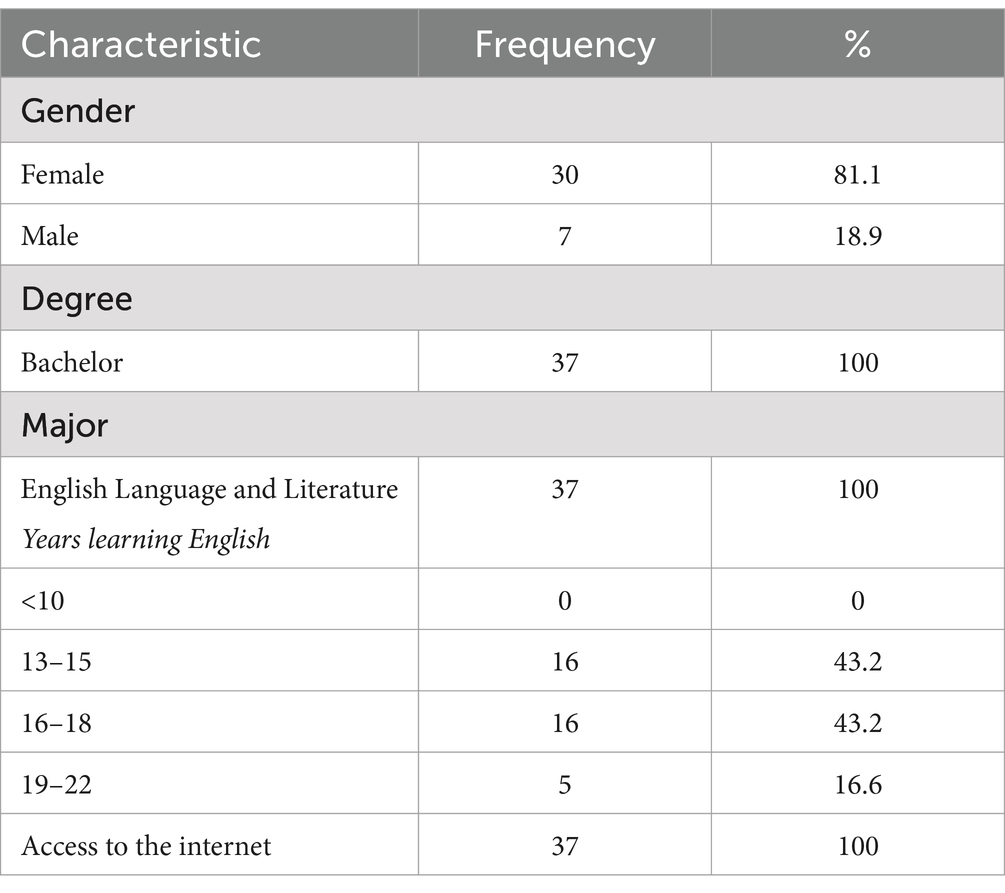

The target respondents in this study comprised a group of 37 (30 females, 7 males) EFL undergraduate learners majoring in English language and literature at an Omani higher learning institution. The gender imbalance in the randomly selected group is a typical reality of higher education nowadays reflected in female students’ dominance in certain programs and disciplines including English language and literature. Thus, gender is a variable beyond the scope of this study. The subjects were between 19 and 22 age ranges. The respondents’ demographic information is shown in Table 1 below. As for academic program enrollment, all the respondents were Bachelor of Arts in English Language and Literature students. In terms of years of learning English experience, 16 (43.2%) had experience of 13–15 years, and the other 16 (43.2%) had experience of 16–18 years, while only 5 (16.6%) had 19–22 years of experience. All the respondents were native speakers of Arabic and had access to the Internet. The subjects were students of the researchers and were chosen randomly to facilitate communication and data collection.

3.3 Data collection instruments

As stated earlier, the present study aimed to examine aspects of EFL learners’ experience with clustered digital materials in enhancing speaking and oral communication skills in the context of situational English. To serve its end in sourcing data, the study utilized open-ended surveys which were designed and distributed among the participants, semi-structured interviews, instructor notes, and demographic information about the respondents (Table 1). Following the authority (Mertens, 2023; Jarrett, 2021; Creswell and Creswell, 2018; Silverman, 2013), a sample survey allows researchers to generalize about a large population by studying only a small portion of the population. The surveys were designed to elicit the participants’ perceived affordance of clustered digital materials implementation in English conversation classes and the impact of that on improving oral and communication skills. The survey comprised two parts. Part I consisted of the participants’ demographic information (sex, age, years spent learning English). Part II consisted of three sections: The first section addressed the difficult areas and issues the respondents encountered in speaking; the second section investigated the most effective teaching strategies in enhancing oral communication and speaking skills as perceived by the respondents, while the third section explored the respondents’ preferences of the clustered digital materials use in the speaking classroom. To strengthen the qualitative and quantitative sources of data, a semi-structured interview was conducted with the respondents as well.

In addition, the dataset collection instruments (surveys and interviews) were piloted and reviewed by five expert researchers before being used to ensure reliability. Based on the feedback provided, a final version of the questionnaire was prepared with a clear set of instructions and focus. The feedback provided was also incorporated into the production of the final version of the interview questions. According to the authority (Hahs-Vaughn and Lomax, 2020; Bryman, 2016), a well-designed questionnaire can help researchers mitigate bias and ensure the reliability and validity of the results. Furthermore, the random selection of respondents, and employment of t-test coupled with accurate data collection instruments are expected to strengthen the results’ consistency. Additionally, the University’s Research Department (URD) granted the researchers approval to collect data without the need to obtain written consent from the participants.

3.4 Data collection and analysis procedures

Data were collected using a questionnaire, a semi-structured interview with students, and instructor notes. For the semi-structured interview, the participants were asked to identify: (1) The areas and skills that need further improvement; (2) The new conversation areas, skills and strategies they learned. Previous research (e.g., Rea and Parker, 2014) has demonstrated the reliability of surveys and interviews when dealing with learners’ impressions (e.g., Mertens, 2023).

The data collection took place over 16 weeks during the Fall semester of the academic year 2022–2023. The participants were contacted for consent before playing the role of data sources. The researchers then asked respondents to complete the surveys and return them. A semi-structured interview was also conducted with the participants. A clear explanation of the research topics and purpose was given to participants taking part in data collection, and they were informed their responses would remain confidential. The participants’ responses in the survey and interview were collected and analyzed using descriptive methods. The respondents’ answers to each open-ended question in the survey and the interview were grouped and analyzed to collect their insights on issues addressed in each question concerning the use of clustered digital materials in situational English classrooms. Specifically, the responses to the survey and interview were analyzed to determine the impact of digital materials in enhancing EFL learners’ oral communication skills.

3.4.1 Statistical test method

The study used a combined methodology that integrated the methods of data collection and analysis with a basic statistical test method. While the results were interpreted by analyzing students’ perceptual evaluation of clustered digital resources and their impact on learners’ speaking skills, the statistical test method was used to determine whether there was a significant difference between the data collected before the treatment and the data collected after the treatment. The first part of the methodology applied the paired-sample t-test which allowed researchers to measure the statistical difference in the speaking skills of the same sample of students before and after exposing them to clustered digital materials.

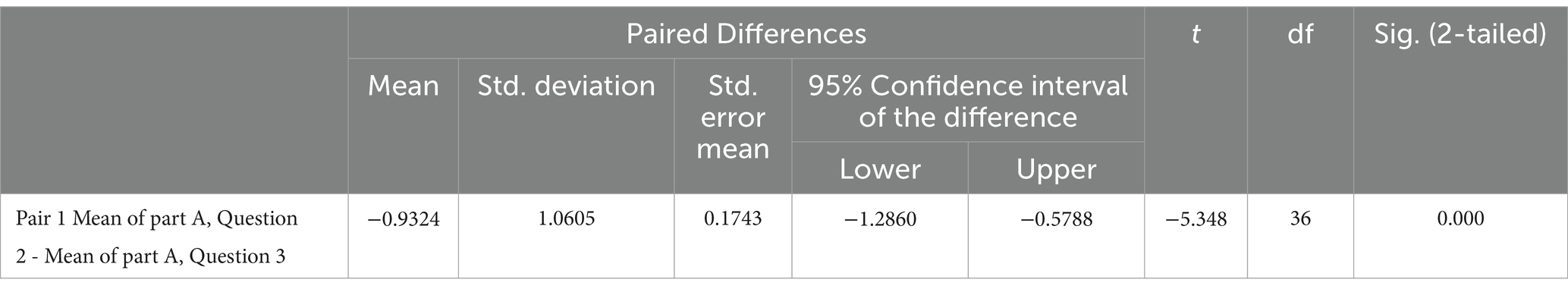

According to Ross and Willson (2017), “A paired-samples t-test compares the mean of two matched groups of people or cases, or compares the mean of a single group, examined at two different points in time.” (p. 17). If the p-value is less than 0.05, this means there is a statistically significant difference in the students’ performance. This study employed the paired-sample t-test method by comparing the mean scores of the same group at two different points: before the treatment (exposing the students to clustered digital materials) and after the treatment for one academic term. The first part of the analysis provided a statistical reading of the results focusing on the difference in the mean scores and the two-tailed p-value to assess whether the correlation between the variables was statistically significant.

4 Results and discussion

This section presents the analysis and discussion of the results of the questions addressed by the study. The results are analyzed and discussed under four main themes, namely the perceived difficulties learners had in speaking before experiencing learning situational English via clustered digital materials, the skills and areas developed by the respondents after being exposed to clustered digital materials in the speaking classroom, respondents’ preferences for digital materials implemented in the situational English classroom, and the respondents’ perceived effectiveness of pedagogical facilitation associated with clustered digital materials.

4.1 Statistical test results

A paired-samples t-test was calculated to compare the means of the pre-treatment score and post-treatment score for the same sets of items for the same sample and check the learners’ progress at the end of the course. The paired-samples correlations in Table 2 above indicate a significant correlation between the variables of students’ speaking skills before and after the treatment. Table 2 reveals that the difference between the two means (the pre-test mean score and the post-test mean score) has a negative value of (−0.9324). This value validates the emergence of progress in students’ performance after applying the intervention (clustered digital materials). Also, the paired differences in Table 2 show a t-value of (−5.348), df = 36, and p-value of (0.000). Since p-value is <0.05, the results confirm that there is a statistically significant difference between the means for the learners. This finding validates previous studies on the positive effects of implementing digital materials as pedagogic tools to improve students’ speaking competencies (John and Yunus, 2021; Kress and van Leeuwen, 2001; Bonsignori, 2018; Goh and Burns, 2012).

4.2 Perceived challenges in oral communication and speaking skills

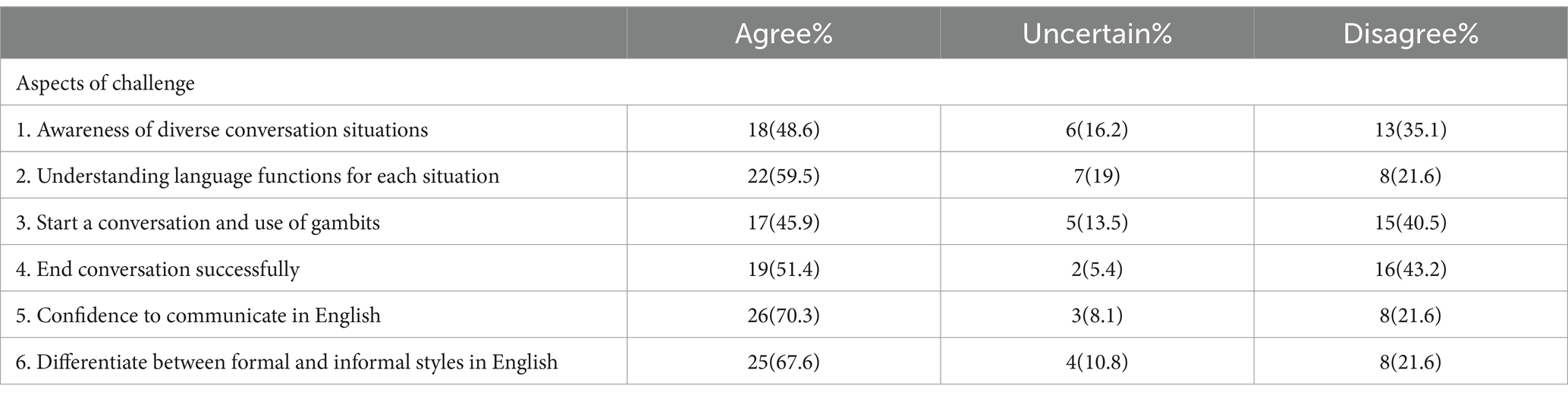

The respondents were asked to indicate the level of difficulty they had in certain aspects related to oral communication and conversation skills in English before studying the Course “Situational English.” The respondents’ perceived challenging areas in speaking are presented in Table 3. The analysis revealed that less than half of the respondents 48.6% agreed and 35.1% disagreed with a lack of awareness of diverse conversational contexts. One of the respondents stated, “I still need to learn how to talk about different topics” (S1). Another subject reported “I think I should improve my ability to speak to different people” (S2). There were also 16.2% of the respondents who were not sure about the significance of speakers’ knowledge of the situation in which they find themselves communicating with others. This suggests that exposing students to various conversational situations is better enhanced by raising their awareness of the significance of the conversation and communication context. That is, EFL learners of situational English are better trained to analyze and understand the situation in which they communicate. Such exposure is deemed important in building the students’ oral communication and conversation skills.

Results also showed that 59.5% of the respondents agreed and 21.6% disagreed that they had difficulty in understanding the specific language functions for each communicative and conversational situation. Comments such as “I have difficulty in understanding the different functions of language” (S3), and “I think the expressions, especially the ones related to social skills are difficult for me” (S4), were made by the respondents to explain perceived challenges in speaking in English. On the other hand, only 19% of the respondents were not sure of their level of language difficulty specific to a particular situation. This finding is significant because it confirms the previous result concerning the students’ lack of awareness of the role the diverse conversation contexts play in effective communication. It was also observed that the respondents showing agreement and disagreement (45.9 and 40.5%) outnumbered those who were not sure of perceiving conversation gambits as a challenging area (13.5%). This result indicates the significance of drawing learners of English attention to the necessity of adhering to the linguistic and stylistic demands of each conversational act.

As Table 3 above reveals, half of the respondents, 51.4%, perceived ending of conversation as a challenge, while 43.2% disagreed and 5.4% were unsure of their stand on the issue. One of the respondents mentioned “I still need to develop the skills of ending conversations” (S5). The analysis also revealed that the majority of the respondents 70.3% agreed to have less confidence in communicating in situational English, 21.6% expressed disagreement and 8.1% were not sure of their stand on the statement. Statements such as “I need to learn to speak in front of everyone without tension” (S6), “I feel that I really need to improve my English language because I do not feel happy about my level” (S7), and “I need to share my thoughts more and stop being scared to let them out” (S8), were made by the students to address lack of confidence in communicating in English for different functions and purposes. This result implies that the limited practice of English due to an absence of wider interactional contexts beyond the classroom is better addressed in the EFL university language education. With cultural influences and limited communicative contexts, EFL learners are constrained to develop effective oral communication and speaking skills which lead to demotivation and lack of confidence. This observation confirms the findings of Omar and Salih (2023), Salih and Omar (2023), Omar (2021), and Salih and Omar (2022c) that Omani students’ communicative style is influenced by their culture in both virtual and on-site classes. On the other hand, results indicated that 67.6% of the respondents confirmed facing difficulties in distinguishing between formal and informal styles in conversations in English. One of the participants reported that “speaking in formal and informal language is one of my major problems in learning English” (S9). There were 21.6% of the respondents who disagreed and 10.8% who were not sure.

It is worth mentioning that the respondents ranked lack of confidence as the most challenging aspect of learning oral communication, followed by knowing the differences between formal and informal styles in English, understanding the suitable language to be used for each conversation situation, how to end a conversation, awareness of diverse conversation situations, and how to start a conversation. This result is significant because it implies that understanding learners’ difficulties in speaking may inform teachers’ pedagogic decisions and choices. Moreover, it is interesting to note that although the respondents showed mixed views in terms of agreement, disagreement, and uncertainty, their responses were higher when it came to difficulties in speaking and conversational English. This is important to note because it implies that teaching speaking and oral communication in English can be taught more creatively.

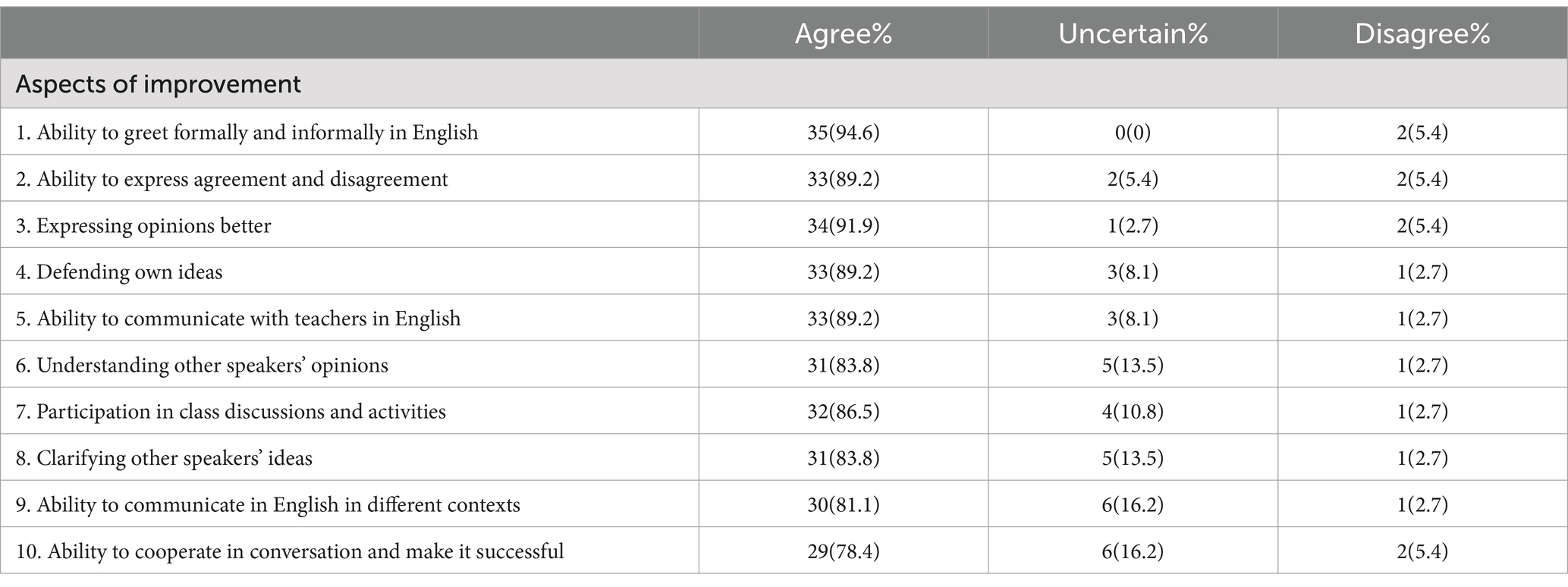

The respondents were also asked about their views on the use of clustered digital materials in English conversation classes. Table 4 above demonstrates the respondents’ perceived learning aspects that have been improved through clustered digital materials.

4.3 Perceived aspects of improvement and skills attainment

As Table 4 above shows, the majority of respondents 94.6% confirmed positively that learning oral communication through clustered digital materials has enhanced their ability to use formal and informal greetings in English. One of the participants reported “Now I can start and end conversations with friends and other people and speak with teachers during office hours” (S10), and another mentioned “I learned the difference between formal and informal conversations, such as where to use, how to use, etc.…” (S11). Only 5.4% of the respondents disagreed. This result indicates an improvement in the respondents’ understanding of the significance of differentiating between formal and informal conversations in English. This aspect was perceived as challenging by 67.6% of the respondents (Table 3). On the other hand, 89.2% of the respondents agreed that they improved their ability to express agreement and disagreement in speaking. There were 5.4% of the uncertain respondents and those who disagreed. The analysis also revealed that 91.9% of the respondents found themselves better at expressing opinions after studying situational English topics through clustered digital materials. One of the respondents stated “I learned how to clarify my ideas and it helped me too much in English Club discussions” (S12). In the same vein, the respondents showing agreement in confirming improvement at defending their ideas and ability to communicate with teachers in English (89.2% for each) far outnumbered those who expressed uncertainty and disagreement (8.1 and 2.7% for each respectively). In the same context, both Tables 3, 4 demonstrate that the number of respondents who expressed disagreement in confirming the difficulties they had in speaking or the improved competencies and skills after studying conversational English in clustered digital material-aided classrooms is smaller than those who agreed in both cases.

Results also indicated that there were 83.8% of the respondents who expressed improvement in understanding other speakers’ opinions and clarifying other speakers’ ideas. Those who expressed uncertainty and disagreement were 13.5% and 2.7% each, respectively. In addition, there were 86.5% of the respondents who reported improved abilities for participating in class discussions and activities. The uncertain respondents and those who disagreed were 10.8 and 2.7%, respectively.

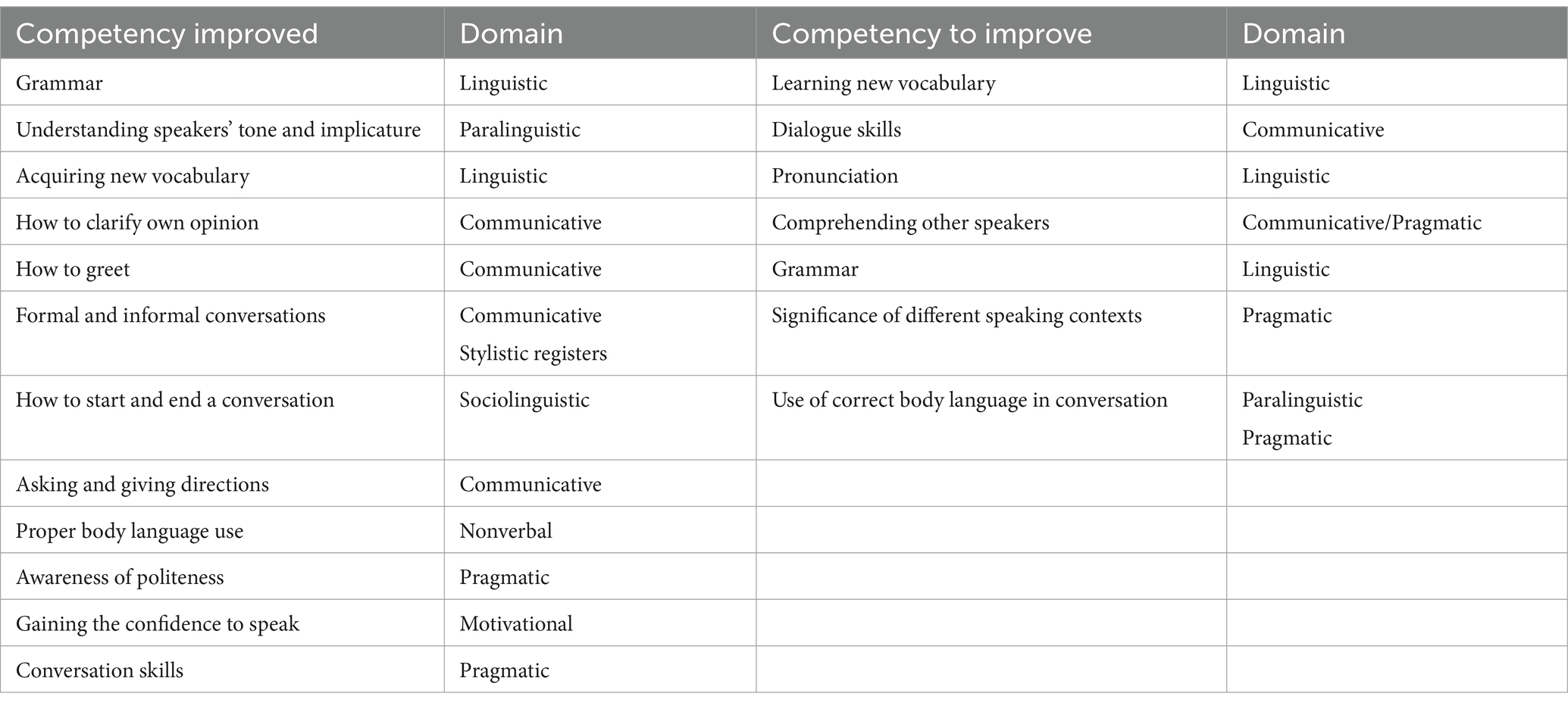

The respondents were also asked to specify any new conversation areas, skills, or strategies they learned, as well as any areas or skills that require further improvement. Table 5 below summarizes the respondents’ perceived advancements in certain conversation skills and areas as well as aspects and competencies that need further improvement.

As Table 5 reveals, the respondents expressed improvement in various conversational skills related to different domains as well as the realization of gaps in their linguistic knowledge and other oral communication and speaking skills. For instance, the respondents found integrating clustered digital materials in English conversation classrooms beneficial for improving their grammar accuracy and understanding the significance of paralinguistic cues in oral communication and conversation such as speakers’ tone and implicature. One of the participants reported “I improved understanding other speakers’ tone of voice and learning new words” (S13). The respondents also reported improvement in their nonverbal communicative skills, use of stylistic registers, and pragmatic awareness as well as gaining more confidence in oral communication and speaking in English. On the other hand, the respondents also reflected on the speaking skills and oral communication aspects that need further improvement and attention. Learning new lexical items is a need that the respondents felt was urgent.

This result contradicts with Al-Ghamdi and Al-Bargi (2017) that the application of technologically enhanced instructional method did not leave a positive impact on the speaking skills of EFL learners. The result is significant because it implies that exposing students to authentic materials and engaging them in conversation analysis raises their awareness of the actual gaps in their knowledge. Another linguistic aspect reported by the respondents as an area that needs further improvement relates to pronunciation. In addition, the respondents identified understanding the influence of different speaking contexts on interlocutors’ meanings and intended messages as an aspect that they still need more support for. Furthermore, the use of appropriate body language is still a conversation aspect that the respondents felt significant. It is worth mentioning that the overwhelmingly positive responses by the respondents reveal the relevance and effectiveness of using clustered digital materials as pedagogic tools to enhance EFL learners’ oral communication and speaking skills.

4.4 Effectiveness of clustered digital material in enhancing oral communication and speaking skills

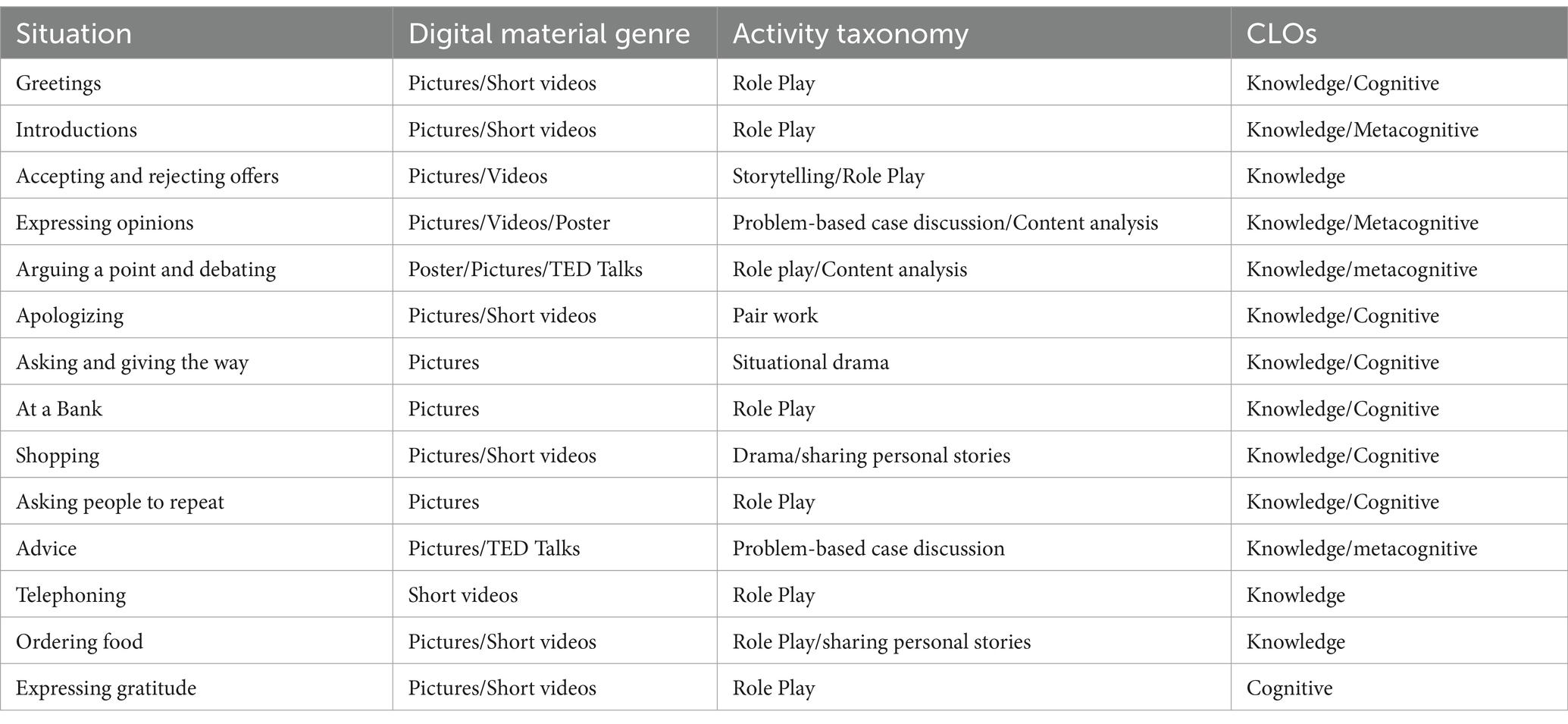

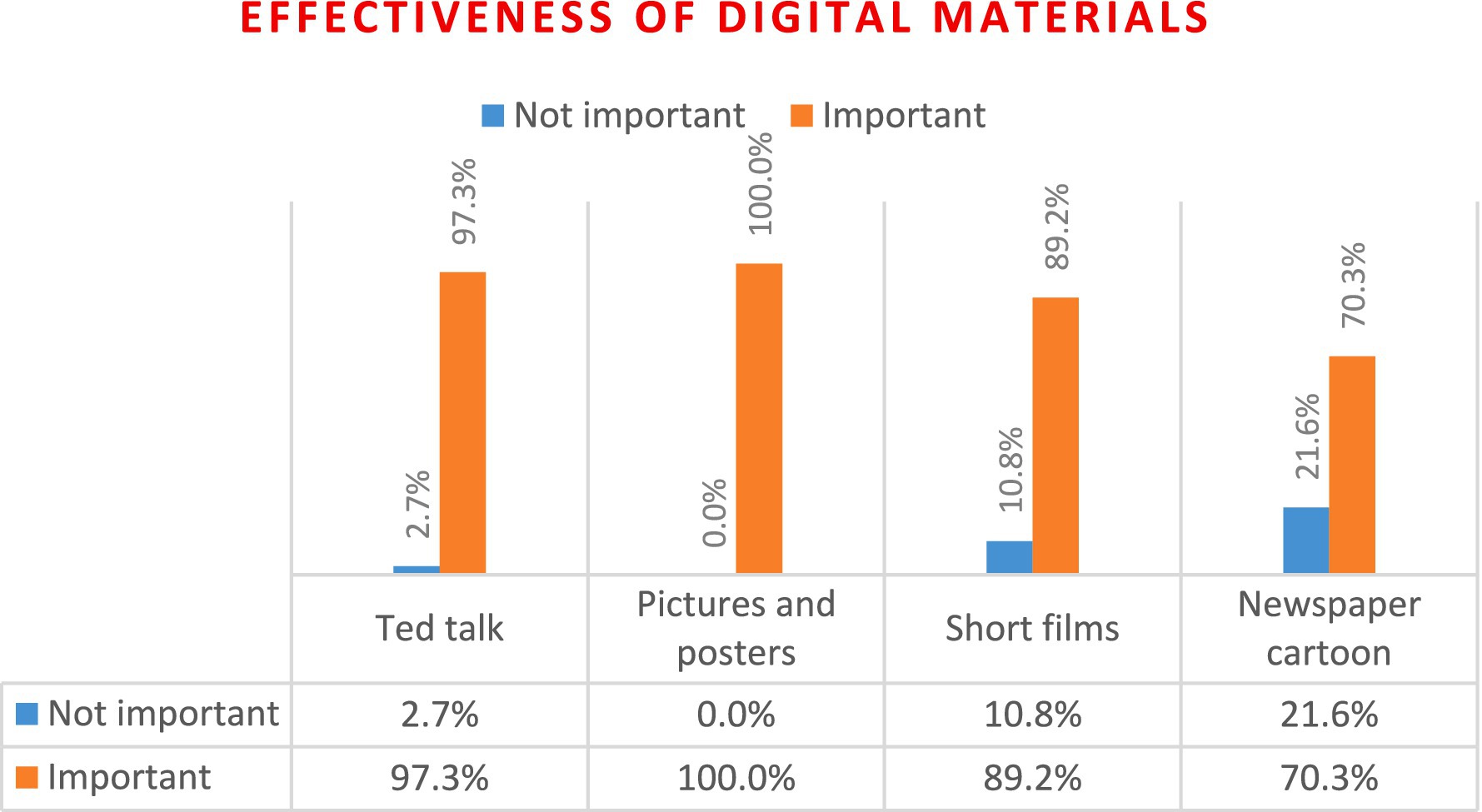

To further examine the effectiveness of the implementation of clustered digital materials to enhance oral communication and speaking skills, the respondents were asked to list the digital materials used based on their relevance and significance. Table 6 provides an overview of the implementation of digital materials to enhance respondents’ oral communication and speaking skills in the context of situational English topics. The clustered digital materials used were TED Talks, pictures and posters, short videos, and newspaper editorial cartoons (Figure 1).

As Figure 1 above shows, the respondents (100%) ranked pictures and posters as the most effective materials in enhancing oral communication and speaking skills, followed by TED Talks speech contents (97.3%), short videos (89.2%), and finally newspaper editorial cartoons (70.3%). This result indicates that the respondents were in complete agreement about the value of images and posters in enhancing communication and were more interested in interactive visual materials that have more engaging power to invite cognitive and critical thinking. This suggests that the use of pictures and posters enabled the respondents to express their views, generate ideas, negotiate other speakers’ opinions, and think critically as they engaged in evaluating the messages these materials carried. In the same vein, TED Talks and short videos were found effective by the respondents in serving the same objectives of posters and pictures in enhancing oral communication. As far as the listing of short videos is concerned, the marginally lower proportion in comparison to TED Talks may indicate that respondents have more complex preferences. This finding suggests a significant inclination toward verbal communication in multimedia content. The high percentages indicate that respondents viewed digital materials with visual content as helpful tools for generating discussions and ideas sharing and honing their speaking and oral communication abilities.

The respondents, through sample speech analysis, discussing speakers’ ideas, clarifying others’ opinions, and debating their views, were able to interact with each other and explore oral communication and speaking strategies. It is interesting to note that newspaper editorial cartoons were less preferred as the respondents rated them last among other clustered digital materials used in the speaking classrooms. Although the respondents who found editorial cartoons significant were still a majority (70.3%) with 21.6% who viewed them as less significant, this decreased percentage indicates that students may be less likely to use editorial cartoons to improve their speaking and oral communication abilities. This suggests that learners of English conversation might find these resources less interesting or useful than they would have otherwise. This result suggests that the respondents had less exposure to newspaper editorial cartoons which implies that the implicit nature of editorial cartoons did not provide the respondents with the opportunity to initiate conversation or discussions.

It is worth mentioning that the thematic clustering of digital materials and their contents facilitated providing effective pedagogical support to motivate the students to speak and unconventionally engage them. In addition, exposing EFL learners to TED Talks and short videos not only enhances their speaking and debating skills but also their listening skills. According to the statistics, there appears to be a distinct hierarchy of respondents’ preferences for various clustered digital materials. Posters and pictures were unanimously considered to be the most significant, closely followed by TED Talks and short videos. Even while most respondents still thought editorial cartoons in newspapers were significant, they were ranked lower than the other materials. This implies that respondents’ views can be used to inform teachers’ selection of instructional resources and materials that suit the interests of their students and are thought to be beneficial in enhancing oral communication abilities. This result conforms with Bergil (2016) on the importance of understanding learners’ expectations by language instructors while applying blended speaking activities within or outside the classroom.

As Table 6 above demonstrates, the implementation of digital materials added flexibility to the class practices by accommodating a variety of interactive activities. Pedagogically speaking, the flexible nature of the classroom and the associated language learning activities added another dimension related to the intended learning outcomes with a focus on both knowledge and metacognitive skills. This dimension with its focus on crucial skills aligned with a comprehensive language learning approach that encompasses not only grammar and vocabulary but also higher-order thinking abilities and self-awareness. It can be argued that clustered digital materials offer learners the flexibility to progress at their own pace, facilitating individualized practice and allowing students to revisit content, practice speaking, and receive feedback as needed. This adaptability contributes to a personalized learning experience. Hence, this pedagogical value of clustered digital materials can be utilized to provide effective pedagogical support to speaking classes to ensure that students across competencies are actively engaged in the learning process and class activities. This finding confirms the results of earlier research on the need to create a flexible learning environment that minimizes anxiety and motivates learners to engage in speaking classroom activities (Buckingham and Alpaslan, 2017; Golonka et al., 2014).

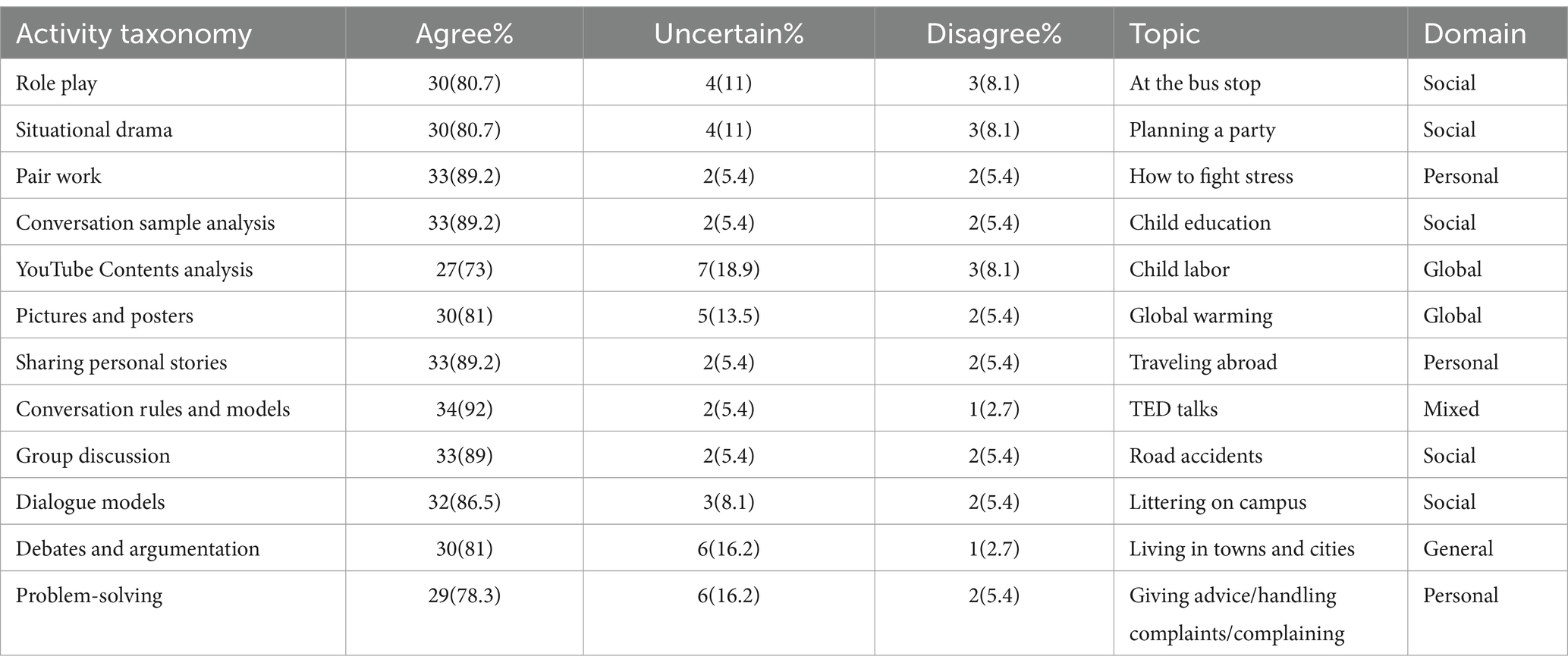

4.5 Effective pedagogical facilitation and clustered digital materials

Table 7 below demonstrates that the respondents’ views reveal high agreement percentages concerning the activities associated with the use of digital materials in the speaking classrooms. A mix of interactive, practical, analytical, and authentic activities effectively improves speaking skills, based on the high agreement percentages across these activities. This indicates a strong agreement among the respondents about the effectiveness of these activities in enhancing their oral and speaking skills. This implies that exposing situational English learners to diverse interactive activities will enable them to improve their oral communication skills and other competencies. For instance, creating and enacting scenario-based role play and situational drama gives students a hands-on, interactive way to practice language skills. In addition, engaging respondents in pair work encouraged them to collaborate and foster communication skills. Another advantage is that these activities enabled respondents to apply language skills to situations they might encounter in their everyday lives. The respondents also valued analyzing various digital material contents which exposed them to a variety of language structures and communication styles. This suggests that engaging students in pedagogically planned activities involving digital posters, pictures, videos, and YouTube content offers visual and audio stimuli which can effectively sustain language learning.

On the other hand, the respondents agreed that by sharing personal stories and engaging in group discussions, they were exposed to authentic communication settings for self-expression and dynamic interaction. Interestingly, engaging the respondents in discussing conversation rules and models received the highest percentage of agreement. This suggests that conversation rules and models offer systematic guidance, potentially providing a framework for the respondents to build their oral communication and conversational skills. This combination of rules and spontaneity enables a more comprehensive approach to language learning, particularly conversational skills. The respondents appreciated their involvement in activities related to dialogue models, debates, and argumentation as well as problem-solving cases. These activities also received high percentages of agreement. The implication is that since participants must evaluate information critically, build sound arguments, and persuade others of their viewpoints, these activities foster the development of analytical abilities. This is beneficial for general cognitive growth as well as language skills. This result supports previous research on the significance of adopting effective pedagogies which encourage deep and student-centered learning and enhance learners’ speaking competencies (Ellis, 2003; Ellis et al., 2019; Benson and Voller, 1997; Benson, 2004; Nunan, 1999, among others).

5 Conclusion, recommendations, and limitations

The results of this study indicate that the use of clustered digital materials in EFL instruction can help in enhancing learners’ oral communication and conversation skills. The implementation of digital materials, particularly when introduced in an organized manner within the situational English context, captured the participants’ attention and enhanced their engagement in the learning process. The study confirms conclusions drawn in earlier studies on the necessity to implement diverse activities in a cycle of pedagogically-planned steps that enhance students’ performance with timely scaffolding and feedback (Goh and Burns, 2012; Richards, 2008). Interactive and visually appealing materials have the potential to inspire and motivate students to actively participate in speaking activities. Additionally, implementing clustered digital materials in the speaking classrooms provided learners with the opportunity to engage with authentic and real-world language use, exposing them to various accents, tones, and communication styles. This exposure is likely to improve their capacity to comprehend and use spoken English in diverse contexts. Thus, to help learners improve their oral communication and conversational skills, situational English, and conversation in English instructors are highly encouraged to embrace digital materials which often integrate different forms of media, such as audio, video, images, and interactive exercises. This multimodal approach accommodates various learning styles and offers learners of situational English an array of rich and useful audiovisual input to improve their oral and speaking skills effectively.

In terms of enhancing collaborative learning abilities of students, clustered digital materials promoted collaborative learning experiences, enabling learners to participate in class discussions, analyzing materials contents, or work in pairs practicing giving or receiving feedback. These activities provided valuable opportunities for practicing spoken English in a social context, thereby enhancing communication skills. In addition, through these activities, participants are expected to develop analytical skills as they critically evaluate information, construct logical arguments, and present their ideas persuasively. Another positive effect of introducing digital materials in situational English classrooms is that the incorporation of interactive elements within clustered digital materials added an element of enjoyment to the learning process. Interactive simulations motivated learners to engage in spoken English within a relaxed and stress-free environment, fostering a positive attitude toward language learning.

As far as enhancing the oral communication and speaking competencies of learners through access to authentic resources is concerned, the Internet offers an extensive array of authentic multimodal resources, such as posters, YouTube videos, podcasts, interviews, and TED Talks. Clustered digital materials guide learners in accessing and utilizing these resources to enhance their listening and speaking skills in real-world situations (Buckingham and Alpaslan, 2017; Cannon, 2018; Frechette and Williams, 2016; Golonka et al., 2014; Hidayat et al., 2022). Another pedagogical advantage lies in the fact that digital tools often feature pronunciation practice, allowing English language learners to reflect on their pronunciation. This focused practice may contribute to improving learners’ spoken English reducing pronunciation challenges, and increasing their self-confidence. Another pedagogical value suggested by the study relates to the flexible and adaptable nature of clustered digital materials. The adaptability of digital materials allows for easy updates to reflect current language trends and changes. This ensures that learners are exposed to contemporary language use, a crucial factor in improving oral communication skills in a dynamic language environment.

Employing clustered digital materials in EFL instruction offers numerous advantages that positively influence learners’ oral communication and speaking skills. These advantages encompass increased engagement, exposure to authentic language use, opportunities for multimodal learning, self-paced learning, immediate feedback, collaborative experiences, gamification, access to authentic resources, enhanced pronunciation practice, and flexible content adaptation.

The present study has certain limitations. The study only examined the oral communication and speaking skills of the participants, other skills were beyond its scope. Although the participants in this investigation were the representatives of the target population, their small size (N = 37) suggests that the study’s results should be generalized with caution. Furthermore, this study focused only on EFL students. The effects of clustered digital materials in speaking classrooms can further be investigated within interdisciplinary contexts. In addition, this study focused on one private university in Oman. Future studies may include both private and public universities.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the [patients/ participants OR patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin] was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

AS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahmad, S. Z. (2019). Digital posters to engage EFL students and develop their reading comprehension. J. Educ. Learn. 8, 169–184. doi: 10.5539/jel.v8n4p169

Al-Ghamdi, M., and Al-Bargi, A. (2017). Exploring the application of flipped classrooms on EFL Saudi students’ speaking skill. Int. J. Linguist. 9, 28–46. doi: 10.5296/ijl.v9i4.11729

Alharbi, N. S. (2024). Exploring the perspectives of cross-cultural instructors on integrating 21st century skills into EFL university courses. Front. Educ. 9, 1–12. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1302608

Al-Jamal, D. A., and Al-Jamal, G. A. (2013). An investigation of the difficulties faced by EFL undergraduates in speaking skills. Engl. Lang. Teach. 7, 19–27. doi: 10.5539/elt.v7n1p19

Alzboun, B. K., Smadi, O. M., and Baniabdelrahman, A. (2017). The effect of role play strategy on Jordanian EFL tenth grade students' speaking skill. Arab World English J. 8, 121–136. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol8no4.8

Asratie, M. G., Wale, B. D., and Aylet, Y. T. (2023). Effects of using educational technology tools to enhance EFL students' speaking performance. Educ. Inf. Technol. 19, 1–21. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-11562-y

Bailey, K., and Nunan, D. (2004). Practical English language teaching: Speaking. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Beauvois, M. (1997). “Computer-mediated communication (CMC): technology for improving speaking and writing” in Technology enhanced language learning. eds. M. Bush and R. Terry (Lincolnwood, IL: National Textbook Company), 165–183.

Benson, P. (2000). “Autonomy as a learners’ and teacher’s right” in Learner autonomy, teacher autonomy: New directions. eds. B. Sinclair, I. Mcgrath, and T. Lamb (London: Addison Wesley Longman), 111–117.

Benson, P. (2004). “Autonomy and information technology in the educational discourse of the information age” in Information technology and innovation in language education. ed. C. Davison (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press), 173–192.

Benson, P., and Voller, P. (1997). Autonomy and independence in language learning (1997). Routledge.

Bergil, A. S. (2016). The influence of willingness to communicate on overall speaking skills among EFL learners. Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 232, 177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.10.043

Bonsignori, V. (2018). Using films and TV series for ESP teaching: a multimodal perspective. System 77, 58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2018.01.005

Brown, G., and Yule, G. (1983). Teaching the spoken language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buckingham, L., and Alpaslan, R. S. (2017). Promoting speaking proficiency and willingness to communicate in Turkish young learners of English through asynchronous computer-mediated practice. System 65, 25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2016.12.016

Cannon, M. (2018). Digital media in education: Teaching, learning and literacy practices with young learners. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cook, V. (2002). “Language teaching methodology and the L2 user perspective” in Portraits of the L2 user. ed. V. J. Cook (Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters), 325–344.

Creswell, J. W. (2015). A concise introduction to mixed methods research. London: SAGE Publications.

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 5th Edn. London: SAGE Publications.

Donny, C. D., and Adnan, N. H. (2022). TESL undergraduates’ perceptions: utilizing social media to elevate speaking skills. Arab World English J. 13, 539–561. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol13no4.35

Ellis, R., Skehan, P., Li, S., Shintani, N., and Lambert, C. (2019). Task-based language teaching: theory and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fareh, S. (2010). Challenges of teaching English in the Arab world: why can’t EFL programs deliver as expected? Procedia 2, 3600–3604. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.559

Frechette, J., and Williams, R. (2016). Media education for digital generation. 1st Edn. New York: Routledge.

Given, L. M. (2008). The sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. London: SAGE Publications.

Godwin-Jones, R. (2009). Emerging technologies speech tools and technologies. Lang. Learn. Technol. 13, 4–11.

Goh, C. C. M., and Burns, A. (2012). Teaching speaking: Towards a holistic approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Golonka, E. M., Bowles, A. R., Frank, V. M., Richardson, D. L., and Freynik, S. (2014). Technologies for foreign language learning: a review of technology types and their effectiveness. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 27, 70–105. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2012.700315

Hahs-Vaughn, D. L., and Lomax, R. G. (2020). An introduction to statistical concepts. 4th Edn. New York: Routledg, Taylor & Francis.

Haynes, J., and Zacarian, D. (2010). Teaching English language learners across content areas. Alexandria: ASCD.

Hebert, J. (2002). “Prac TESOL: It’s not what you say, but how you say it!” in Methodology in language teaching: An anthology of current practice. eds. J. C. Richards and W. A. Renandya (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 188–201.

Hidayat, D. N., Lee, J. Y., Mason, J., and Khaerudin, T. (2022). Digital technology supporting English learning among Indonesian university students. RPTEL 17, 23–15. doi: 10.1186/s41039-022-00198-8

Jarrett, C. (2021). Surveys that work: A practical guide for designing better surveys. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

John, E., and Yunus, M. M. (2021). A systematic review of social media integration to teach speaking. Sustain. For. 13:9047. doi: 10.3390/su13169047

Kress, G., and van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal discourse: The modes and media of contemporary communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leis, A., and Mehring, J. (2017). Innovations in flipping the language classroom: Theories and practices. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

Li, Z., and Li, J. (2022). Using the flipped classroom to promote learner engagement for the sustainable development of language skills: a mixed-methods study. Sustain. For. 14:5983. doi: 10.3390/su14105983

Loucky, J. P., and Ware, J. L. (2017). Flipped instruction methods and digital technologies in the language learning classroom. USA: IGI Global.

Namaziandost, E., Homayouni, M., and Rahmani, P. (2020). The impact of cooperative learning approach on the development of EFL learners’ speaking fluency. Cogent Arts Human. 7, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/23311983.2020.1780811

Nunan, D. (1991). Language teaching methodology: A textbook for teachers. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Nunan, D. (2003). The impact of English as a global language on educational policies and practices in the Asia-Pacific region. TESOL Q. 37, 589–613. doi: 10.2307/3588214

Omar, L. I. (2021). The use and abuse of machine translation in vocabulary acquisition among L2 Arabic-speaking learners. Arab World English J. Transl. Liter. Stud. 5, 82–98. doi: 10.24093/awejtls/vol5no1.6

Omar, L. I., and Salih, A. A. (2023). Enhancing translation students’ intercultural competence: affordances of online transnational collaboration. World J. English Lang. 13, 626–637. doi: 10.5430/wjel.v13n8p626

Rea, L. M., and Parker, R. A. (2014). Designing and conducting survey research: A comprehensive guide. 4th Edn. USA: Jossey-Bass.

Richards, J. C. (2008). Teaching listening and speaking: From theory to practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Richards, J., and Schmidt, R. (2002). Longman dictionary of language teaching & applied linguistics. 3rd Edn. London: Pearson Education Group.

Ross, A., and Willson, V. L. (2017). Basic and advanced statistical tests: Writing results sections and creating tables and figures. The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Sailun, B., and Idayani, A. (2018). The effect of TED talks video towards students’ speaking ability at English study program of FKIP UIR. Perspektif Pendidikan Keguruan 9, 65–74. doi: 10.25299/perspektif.2018.vol9(1).1423

Salem, A. A. M. S. (2019). A sage on a stage, to express and impress: TED talks for improving oral presentation skills, vocabulary retention and its impact on reducing speaking anxiety in ESP settings. Engl. Lang. Teach. 12:146. doi: 10.5539/elt.v12n6p146

Salih, A. A. (2013). Peer response to L2 student writing: patterns and expectations. Engl. Lang. Teach. 6, 42–50. doi: 10.5539/elt.v6n3p42

Salih, A. A. (2017). English(es) and outer circle learner: opportunities and challenges. Am. Res. J. English Liter. 3, 1–10.

Salih, A. A. (2021a). The future of English and its varieties: an applied linguistic perspective. Engl. Lang. Teach. 14, 16–24. doi: 10.5539/elt.v14n4p16

Salih, A. A. (2021b). Investigating rhetorical aspects of writing argumentative essays and persuasive posters: students’ perspective. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 11, 1571–1580. doi: 10.17507/tpls.1112.09

Salih, A. A., and Holi, I. H. (2018). English language and the changing linguistic landscape: new trends in ELT classrooms. Arab World English J. 9, 97–107. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol9no1.7

Salih, A. A., and Omar, L. I. (2020). Season of migration to remote language learning platforms: voices from EFL university learners. Int. J. Higher Educ. 10, 62–73. doi: 10.5430/ijhe.v10n2p62

Salih, A. A., and Omar, L. I. (2021). Globalized English and users’ intercultural awareness: implications for internationalization of higher education. Citizenship. Soc. Econ. Educ. 20, 181–196. doi: 10.1177/20471734211037660

Salih, A. A., and Omar, L. I. (2022a). Action research-based online teaching in Oman: teachers‟ voices and perspectives. World J. English Lang. 12, 9–19. doi: 10.5430/wjel.v12n8p9

Salih, A. A., and Omar, L. I. (2022b). Reflective teaching in EFL online classrooms: teachers’ perspective. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 13, 261–270. doi: 10.17507/jltr.1302.05