- 1School of Education, University of Nicosia, Nicosia, Cyprus

- 2School of Law, University of Nicosia, Nicosia, Cyprus

Introduction

Nowadays, the fast-paced technological development, modernism and the subsequent development, globalization trends, the abolition or loosening of borders, and the refugee and immigration crises have encouraged an unprecedented number of people to migrate across the world. In this context, as states are exposed to the aforementioned external influences, they no longer reflect coherent legal spaces comprised of culturally-homogeneous populations attached to specific geographic areas (Portera, 2023). Notably, the significant change of the cultural composition of the population globally has made essential the attainment of a harmonious and peaceful coexistence both at the state- and people-levels. It has also necessitated the cultivation of an inclusive culture and a culture of acceptance of diversity so that worldwide peace, social justice, and social cohesion are achieved (Hajisoteriou and Angelides, 2016).

Arguably, such goals may and should be pursued through education that aims at the development of global citizens. Global citizenship refers to the development of globally-minded individuals and communities, who take the initiative for social, political, environmental, and economic actions on a worldwide scale (Larsen, 2014). Critical global citizenship encompasses awareness and analysis of diversity, the self, the global, and of one's own responsibility, analysis of the historical roots of “othering” discourses, and awareness of the responsibility to respond to injustices and inequalities, but also engagement and action toward empowering the less privileged (Papastephanou, 2023). Drawing from UNESCO's global citizenship framework, Pillay and Karsgaard (2023) assert that global education should involve four essential dimensions. These dimensions are interconnected, addressing local, national, and global systems and structures; substantive assumptions and power dynamics; appreciation for diversity and the significance of respect across various dimensions like gender, socio-economic status, religion, culture, ideology, geography, and more; and ethically responsible and conscientious engagement.

What we argue in this opinion article is that the teaching of history may become the vehicle to developing globally-competent citizens, as it may be used as an argument, example, and symbol of change (Mutluer, 2013; Hajisoteriou and Angelides, 2016). At the same time, we seek to highlight that by transforming the teaching of history, school history may be used to exert influence on conversations and interpretations, dominant narratives, and world interpretations that explain, identify, and influence the world (Nordgren, 2016). Given the importance of school history in building global citizenship (Nordgren, 2017), this opinion article aims to urge history teachers, on the one hand, to make an impact in cultivating global citizenship by endorsing an intercultural approach. On the other hand, it aims to urge history curriculum developers and teachers' educators around the world, to put the necessary structures, resources, and policies, and practices in place for the history teachers to be able to make that impact.

Transforming school history for global citizenship

School history has traditionally served the portrayal of the state as conterminous to the nation by building a homogenous national identity through “national cleansing” efforts (Klerides and Zembylas, 2017). As Poulsen (2013, p. 404) cautions, even nowadays, in the era of globalization, “instead of allowing growing internalization to be reflected in the content of history, decision-makers tend to place their nation's historical narrative at the center of their curricula; some even expect the subject to focus on preservation and to pass on an (unchanged) national heritage.” The promotion of dominant national ideologies in school history draws upon a rigid recounting of past events, which is grounded only on the “desirable” past elements, and presents school history as the “undeniable truth” (Lauritzen and Nodeland, 2017). On the other hand, Mutluer (2013) suggests that, in our globalized and culturally-diverse world, the goal of cultivating a rigid national identity through school history should be replaced by the goals of developing students' global citizenship so as to safeguard democracy and political liberties. In this context, Pöllmann (2021) contends that there is a need for an intercultural transformation of school history, advocating for a gradual progression “from the mental state of ‘ethnocentrism'—followed by the intermediate stages of ‘denial,' ‘defense,' ‘minimization,' ‘acceptance,' ‘adaptation,' and ‘integration'—to eventually reach the mental state of ‘ethnorelativism”' (p. 1).

School history should thus balance the feeling of belonging to the state with the feeling of being a global citizen by building students' intercultural competence (Hajisoteriou and Angelides, 2016). In order to reinforce students' global citizenship there is an imperative need to teach history through an intercultural perspective that differs substantially from the traditionally served narrowly-defined national goals (Johansson, 2019). To this end, the teaching of history should enhance students' stances against oppression, racism, and social discrimination by incorporating the following five aspects: (a) experience one's own position in historical culture; (b) experience history as cultural encounters; (c) experience history from diverse cultural perspectives; (d) investigate sources from the past to build explanations; and (e) Construct meaningful historical explanations (Nordgren and Johansson, 2015). Nevertheless, Nordgren (2017) clarifies that achieving this transformation should not involve idealizing peaceful coexistence or concealing historical tensions among cultural groups, natives and foreigners, or tradition and change.

Following this route, school history should promote an understanding of the continuous interaction between the past and the present (Carr, 2015), and the between the local and the global (Johansson, 2019). For Carr, school history should not reinforce students' perceptions of historical facts as “objective” and requesting them to memorize them as to understand the historical narrative. Carr goes on to assert that the belief that a hard core of historical facts exists objectively and independently of the historian's interpretation is merely a fallacy. Therefore, the teaching of history should cultivate students' interpretative stances toward historical facts on the basis of critical examination and argumentation (Monte-Sano, 2016). Drawing upon Carr (2015), we suggest that history education curricula and teaching should not focus on the teaching of the objective historical truth (which is mostly pre-decided by the state, and instilled as an “uncontested” narrative in its official curricula and textbooks), but on building students' historical literacy that allows them to construct meaningful historical knowledge and interpretations of the past and its relation to the present and the future, and the global scene.

Building global citizenship through historical literacy

By acknowledging that the chosen type and methodologies of school history exert influence on the kind of citizen that a state desires to shape, the following dilemma arises: should we use teaching methodologies of school history that inculcate national pride in developing citizens by “feeding” them with narratives of the history of the “purified nation” that are “essentially positive, uncritical and unproblematic” (Haydn, 2017, p. 277)? Or, should we endorse a type and teaching methodologies of school history aim at developing citizens, who are critical to the relation between national and global history, and thus interculturally competent, observant, able to process information, and question the trustworthiness of historical information and narratives or even historians themselves? On a theoretical level, the answer is relatively simple, yet what happens when theory lags far behind practice?

According to Fordham (2012), the best way to enhance the teaching of history in promoting global citizenship is by reshaping all of its aspects, from school curricula and textbooks to teaching strategies and practices. Such reshaping would allow teachers to move away from traditional teaching methodologies and practices pertaining to the rather monolithic and nationalistic narration of history (Hajisoteriou and Angelides, 2016). The deciding factor are the teachers themselves, who have the responsibility of distancing students from the ignorance of the past and make them vulnerable and subject to manipulation in the present. For this reason, history education should surpass any “methodological nationalism” in their teaching—nonetheless without denying the historical necessity of states—in order to develop and teach a range of alternative post-historical themes so as to provide the opportunity for intercultural learning, knowledge, and competence (Nordgren, 2017). What we argue in this article is that history education may do so by cultivating students' historical literacy and consciousness.

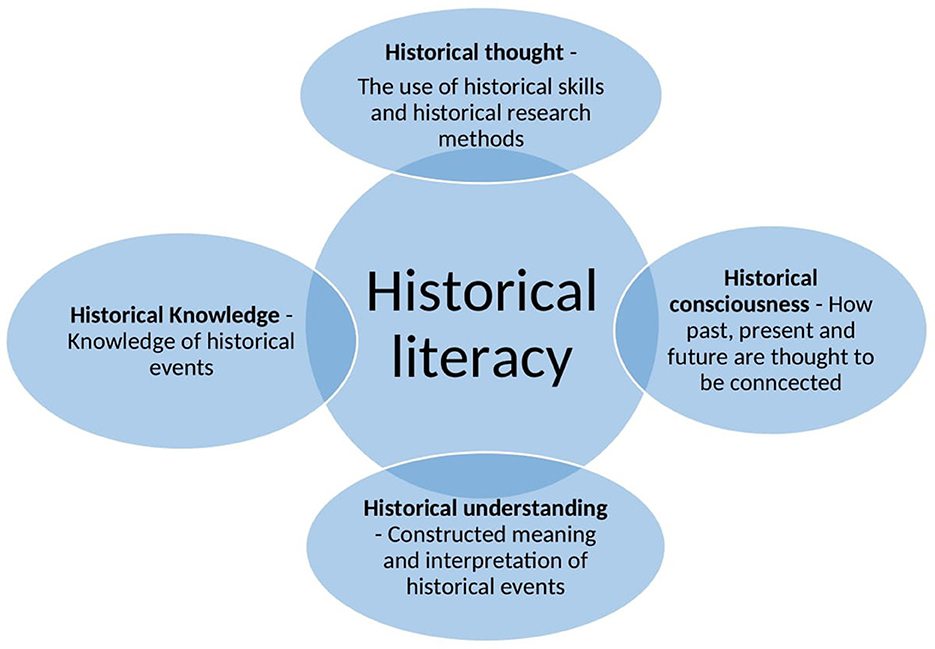

Although there is not a shared definition of historical literacy, in this article, we endorse Downey and Long (2015, p. 7) definition of historical literacy being the “coherent, conceptual, and meaningful knowledge about the past that is grounded in the critical use of evidence.” Historical literacy is concerned with studying history in relation to its social utility and plays an essential role in the development of an individual as a global citizen. By being historically literate, each individual becomes capable of searching, selecting, studying critically, justifying, associating, evaluating, synthesizing, and communicating information and ideals related to history. In this sense, we argue that historical literacy requires transformation in the form of a dialectical (and usually discomforting) process of confrontation between socio-historically formatted cultural capitals (Pöllmann, 2021). Therefore, historical literacy includes both aspects of historical knowledge and historical consciousness, while it may be developed through historical thought and historical understanding. Figure 1 diagrammatically represents the dimensions of historical literacy.

In defining historical consciousness, we argue that it entails the understanding of the temporality of historical experience or how the past, present and future are perceived to be connected. In more detail, historical consciousness includes all the impressions, judgments, ideas and reflections that we obtain through studying history, as long as they stay in our memory with clarity and in our thought as conclusions, as experience, as examples and, as long as they affect us in our understanding and facing of the present, since they affect our evaluations and our decisions (Hajisoteriou and Angelides, 2016). Moreover, historical thought points to the craft of the historian, who uses critical thinking skills to process information from the past. Such skills involve strategies that historians use to construct meanings of past events by comparing and contrasting sources of information (Trombino and Bol, 2012).

Conclusions

In conclusion, the teaching of history should have an intercultural perspective in order to cultivate students' global citizenship. This endeavor should draw upon historical literacy, thought, understanding, and consciousness that are the basis for the development of historical empathy (Hajisoteriou and Angelides, 2016), which is a prerequisite for global citizenship. Bartelds et al. (2020) define contextualization, awareness of one's own positionality, personal connection, and historical imagination as the main components of historical empathy. They argue that historical empathy may be cultivated through teaching practices such as inviting eyewitness with different perspectives, contrasting modern and historical artifacts from diverse cultures, and facilitating historical enquiry from an intercultural perspective. They also indicate that connecting historical empathy to everyday-life, empathy excels students' citizenship competences and leads to the development of thoughtful and empathetic citizens, who are prepared to live in intercultural environments.

In conclusion, history education for global citizenship should foster historical literacy via a critical approach meaning that historical narratives and explanations should be subject to continuous reconsideration from an intercultural perspective (Hajisoteriou and Angelides, 2016). To do so, history education should be based on “decentring” and “perspective recognition,” which “both address the relationship between the learner and the historical other” (Johansson, 2021, p. 73). According to Johansson (2021) perspective recognition involves acknowledging the temporal distinctions between the present and the past. It encompasses the capacity to appreciate the diverse perspectives of history and to comprehend individuals from different social, cultural, and emotional backgrounds within their respective historical contexts. Decentring stems from critical self-reflection and empathy as it seeks “to relativise one's own values, beliefs and behaviors, […] to see how they might look from the perspective of an outsider who has a different set of values, beliefs and behaviors” (Byram et al., 2001, p. 5). Such approach reinforces an intercultural opening to other cultures in order to prepare the global citizen (Johansson, 2019). This turn presupposes in-depth knowledge and trasnformative learning, as students engage in two ways of thinking: the intuitive, referring to formulation of historical questions, and the analytical, referring to historical sources for verification, modification, supplementation, and disproval.

Author contributions

CH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ES: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The University of Nicosia funds publishing fees in open-access journals.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bartelds, H., Savenije, G. M., and van Boxtel, C. (2020). Students' and teachers' beliefs about historical empathy in secondary history education. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 48, 529–551. doi: 10.1080/00933104.2020.1808131

Byram, M., Nichols, A., and Stevens, D. (2001). Developing Intercultural Competence in Practice. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. doi: 10.21832/9781853595356

Carr, E. H. (2015). What is History? Thoughts about the Theory of History and the Historian's Role (Transl. by M. A. Pappas). Athens: Patakis. [In Greek].

Downey, M. T., and Long, K. A. (2015). Teaching for Historical Literacy. Building Knowledge in the History Classroom. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315717111

Fordham, M. (2012). Disciplinary history and the situation of history teachers. Educ. Sci. 2, 242–253. doi: 10.3390/educsci2040242

Hajisoteriou, C., and Angelides, P. (2016). The Globalisation of Intercultural Education. The Politics of Macro-Micro Integration. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-52299-3

Haydn, T. (2017). Teaching history in schools and the problem of ‘the nation'. Educ. Sci. 2, 276–289. doi: 10.3390/educsci2040276

Johansson, M. (2021). Moving in liminal space: a case study of intercultural historical learning in Swedish secondary school. Hist. Educ. Res. J. 18, 65–88. doi: 10.14324/HERJ.18.1.05

Johansson, P. (2019). Historical enquiry in primary school: teaching interpretation of archaeological artefacts from an intercultural perspective. Hist. Educ. Res. J. 16:248. doi: 10.18546/HERJ.16.2.07

Klerides, E., and Zembylas, M. (2017). Identity as immunology: history teaching in two ethnonational borders of Europe. Compare 47, 416–433. doi: 10.1080/03057925.2017.1292847

Larsen, M. A. (2014). Critical global citizenship and international service learning. J. Global Citizensh. Equity Educ. 4, 1–43.

Lauritzen, S. M., and Nodeland, T. S. (2017). What happened and why? Considering the role of truth and memory in peace education curricula. J. Curriculum Stud. 49, 473–455. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2016.1278041

Monte-Sano, C. (2016). Argumentation in history classrooms: a key path to understanding the discipline and preparing citizens. Theory Pract. 55, 311–319. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2016.1208068

Mutluer, C. (2013). The place of history lessons in global citizenship education: the views of the teacher. Turk. Stud. 8, 189–200. doi: 10.7827/TurkishStudies.3849

Nordgren, K. (2016). How to do things with history: use of history as a link between historical consciousness and historical culture. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 44, 479–504. doi: 10.1080/00933104.2016.1211046

Nordgren, K. (2017). Powerful knowledge, intercultural learning and history education. J. Curric. Stud. 49, 663–682. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2017.1320430

Nordgren, K., and Johansson, M. (2015). Intercultural historical learning: a conceptual framework. J. Curric. Stud. 47:1. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2014.956795

Papastephanou, M. (2023). Global citizenship education, its partial curiosity and its world politics: visions, ambiguities and perspectives on justice. Citizensh. Teach. Learn. 18, 228–243. doi: 10.1386/ctl_00122_1

Pillay, T., and Karsgaard, C. (2023). Global citizenship education as a project for decoloniality. Educ. Citizensh. Soc. Justice 18, 214–229. doi: 10.1177/17461979221080606

Pöllmann, A. (2021). Bourdieu and the quest for intercultural transformations. Sage Open 11, 1–8. doi: 10.1177/21582440211061391

Portera, A. (2023). Global versus intercultural citizenship education. Prospects 53, 233–248. doi: 10.1007/s11125-021-09577-3

Poulsen, J. (2013). What about global history? Dilemmas in the selection of content in the school subject history. Educ. Sci. 3, 403–420. doi: 10.3390/educsci3040403

Keywords: history education, intercultural, history teaching, global citizenship, quality education

Citation: Hajisoteriou C, Solomou EA and Antoniou ME (2024) Teaching history for global citizenship through an intercultural perspective. Front. Educ. 9:1435402. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1435402

Received: 20 May 2024; Accepted: 01 November 2024;

Published: 20 November 2024.

Edited by:

Jihea Maddamsetti, Old Dominion University, United StatesReviewed by:

Eva Klemencic Mirazchiyski, Educational Research Institute, SloveniaAntonio Luis Pérez Ortiz, Centro de Profesores y Recursos Región de Murcia., Spain

Copyright © 2024 Hajisoteriou, Solomou and Antoniou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Christina Hajisoteriou, aGFkamlzb3RlcmlvdS5jQHVuaWMuYWMuY3k=

Christina Hajisoteriou

Christina Hajisoteriou Emilios. A. Solomou

Emilios. A. Solomou Mary E. Antoniou

Mary E. Antoniou