- 1Partners for Networked Improvement, Learning Research and Development Center, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

- 2Department of Educational Foundations, Organizations, and Policy, School of Education, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

- 3Broadening Equity in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) Center, Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

Over the past two decades, networked improvement communities (NICs) have become popular for their collaborative, evidence-based approaches to enduring educational challenges. However, traditional improvement science has had inconsistent focus and efficacy in working on issues of racial equity. This study examines the integration of equity into improvement science through the case of the STEM PUSH Network, an NSF-funded alliance aimed at increasing racial and ethnic equity in STEM postsecondary enrollment and persistence. The STEM PUSH Network consists of 40 precollege STEM programs that strive to increase participation of Black, Latine, and Indigenous students in STEM undergraduate pathways. This paper tells the developmental story of how the network has embedded equity into its improvement practices, focusing on professional development in anti-racism and culturally sustaining pedagogy, the adoption of “living” norms, and the restructuring of inquiry cycles to prioritize marginalized voices. Initial results indicate that these efforts have significantly improved the network's equity practice and culture. The network's experiences reveal challenges such as variations in member capabilities while also demonstrating the potential for NICs to effectively incorporate equity into their practice. The STEM PUSH Network's journey offers valuable insights for other improvement networks seeking to prioritize equity, showcasing the necessity and impact of deliberate adjustments in improvement science tools and routines.

1 Introduction

The use of improvement science and networked improvement communities to tackle recalcitrant education system problems has grown exponentially over the last two decades (Bryk et al., 2015; Bush-Mecenas, 2022; Langley et al., 2009). Researchers, practitioners, and designers find these approaches appealing because of their collaborative nature, the ways they draw upon disciplined and evidence-based approaches to solve persistent problems of practice, and their focus on centering practice rather than academic theory. As Russell and Penuel (2022) remarked, “The past decade has seen growing enthusiasm for (and significant federal and philanthropic investment in) new approaches to improvement research that coordinate disciplined methods of iterative design and inquiry” (p. 1). The availability of tools and resources for improvement work has also grown dramatically. There are now handbooks for applying improvement science in education spaces with exercises, templates, and routines, websites with tools for collaborative improvement activities, and tested change packages and models for disseminating knowledge (see for example, Crow et al., 2019; Hinnant-Crawford, 2020; Langley et al., 2009; Valdez et al., 2020).

Improvement science and the associated resources are proliferating, but this discipline did not, at its origin, center equity and did not deliberately articulate increased racial equity as either a key pillar or an associated part of the process. Instead, the mainstream improvement science field emerged from quality improvement and efforts to increase efficiency within business and manufacturing sectors (Bush-Mecenas, 2022) and there was an implicit assumption that an equity goal for the improvement work was sufficient. However, the field of improvement science appears to have recognized the fallacy of this assumption and is focusing increased effort in this area as evidenced by the increase in publications that center equity (see for example Biag, 2019; Hinnant-Crawford, 2020; Jabbar and Childs, 2022; Valdez et al., 2020), increased focus of equity in improvement science professional communities and convenings (see for example, Carnegie Summit on Improvement in Education convening agenda), and philanthropic and federal funding for NICs and improvement science that explicitly call for centering equity (see for example the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Networks for School Improvement initiative and the National Science Foundation INCLUDES Alliance funding mechanism). Connected to this, racial equity is becoming a more deliberately articulated aspect of both improvement research and practice (see for example Dowd and Liera, 2018; Meyer, 2022). While the field of improvement science is undergoing this shift, there is still an ongoing need to interrogate and redesign improvement science tools and routines to meaningfully embody an equity orientation. In addition, improvement science is proliferating across organizations beyond schools into out of school time (OST) learning spaces. OST learning spaces continue to grow in their importance for racially and ethnically minoritized children and youth (see for example Afterschool Alliance, 2014; Akiva et al., 2023), thus research and practice in these domains would benefit from studies that approach the methods, contexts, and learners through explicitly equity-focused approaches. Studies like the current one that examine equity within improvement science in contexts beyond formal K-12 schooling spaces are needed.

This paper describes the work of one networked improvement community (NIC) that uses improvement science to focus on a foundational problem of practice in education–racial and ethnic equity within STEM. The STEM Pathways for Underrepresented Students to Higher Education (PUSH) Network was organized around the shared aim to “increase rates of STEM postsecondary enrollment and persistence for Black, Latina/o/e, and Indigenous precollege STEM program students” (https://stempushnetwork.org/about/). The network engages members from both the out-of-school learning spaces and higher education. The network leadership team (the hub) strategically and iteratively designed racial equity tools and routines into the work, which evolved over time through cycles of reflection and adaptations. We asked the following question to guide our study: “How can improvement science be an effective way to build racial equity into precollege STEM programs?” To address this question, we examined the ways the STEM PUSH Network approached improvement science and assessed our culture, processes, tools, and routines in the service of making change and disrupting racial oppression in STEM. In this paper, we tell the resulting developmental story of how network leaders intentionally centered racial equity in our work, how we learned from our experiences, and how we innovated new and adapted tools, routines, and processes to better serve our racial equity goal as the network evolved.

We start by offering insight into the literatures that inform this work—namely the origins and use of improvement science and networked improvement communities in education, the growing focus on racial equity in improvement science, the importance of racial equity in schools and other organizations, and out of school STEM as a space for addressing racial equity. Following this focused overview of literature, we describe the context and content of our specific network—the STEM PUSH Network, a network focused on supporting racially and ethnically minoritized students into STEM college and career pathways comprising precollege STEM program leaders, higher education professionals, and improvement science and STEM experts. We then explain our methodology by describing the key tools and routines that we started with, and the reflective infrastructure we used to learn from the work. Our findings focus on the developmental story of the changes we made to network processes, tools, and culture to better enact our equity goals which demystifies the “why” and the “how” of operationalizing equity scaffolds within improvement work. We further consider the broader applications of the adaptive practices innovated in this case and the conditions that influenced the equity work. We conclude with implications and next steps for others engaged in building networked improvement communities and using improvement science who are looking to better center equity as a core part of their work.

2 Background

2.1 Improvement science and networked improvement in education

Improvement science has gained prominence in education as a systematic approach to addressing complex educational challenges and improving student outcomes. Rooted in the principles of continuous improvement and evidence-based practice, improvement science offers a rigorous methodology for identifying, implementing, and evaluating strategies that lead to meaningful educational advancements (Langley et al., 2009). The origins of improvement science are often credited to Total Quality Improvement within the business sector, but more recent thought-leaders make the case that the approach was evident within the activist work in the Civil Rights Movement and even further back to scientific study in West Africa (Hinnant-Crawford, 2020). The dominant origin story in which improvement science emerged from business and manufacturing has been the primary narrative driving framework and tool development in education applications of improvement science over the last 20 years in the United States, and this article flows from this line of evolution.

Russell and Penuel (2022) highlight a distinguishing feature of improvement work: “By focusing on practical opportunities, needs, and problems arising in practice-based contexts, the object of inquiry becomes core educational processes such as classroom instruction, after school programming, and counseling and mentoring, which are primary contexts for students' personal, social, and academic development (2022).” According to Bryk et al. (2015), improvement science emphasizes the importance of collaborative inquiry and disciplined problem-solving, engaging educators in ongoing cycles of improvement aimed at achieving specific goals. This iterative process involves the identification of the root causes of persistent problems of practice, systematic collection and analysis of data, the development and testing of interventions, and the sharing of knowledge across educational settings. By applying improvement science methods, educators can effectively diagnose root causes, test innovative solutions in iterative cycles, and make informed decisions based on empirical evidence, accelerating the improvement of educational outcomes in diverse educational contexts.

One key feature of improvement science in education is its emphasis on the use of improvement cycles to drive change. Improvement cycles involve a structured and iterative process that includes the identification of a specific problem, the formulation of a theory of action, the testing and refinement of interventions, and the measurement of outcomes (Bryk et al., 2015; Coburn and Penuel, 2016). This cyclical approach allows educators to continually learn from their efforts and adapt strategies accordingly, promoting a culture of continuous improvement within educational organizations. Improvement science approaches can be magnified and accelerated through collaboration and shared learning among educators through networked improvement communities and communities of practice (Bryk et al., 2015; Coburn and Penuel, 2016). By engaging in collective inquiry and knowledge sharing, educators can leverage the collective expertise and experiences of a broader community to accelerate improvement efforts and foster sustainable change in educational practices.

A networked improvement community (NIC) is a specialized form of a network that is:

1. Focused on a well-specified common aim.

2. Guided by a deep understanding of the problem, the system that produces it, and a shared working theory to improve it.

3. Disciplined by the methods of improvement research to develop, test, and refine interventions.

4. Organized to accelerate the diffusion of these interventions out into the field and support their effective integration into varied educational contexts (Bryk et al., 2015, p. 144).

Taken together, these four characteristics differentiate NICs from more commonly known sharing networks by highlighting that the NIC model is an organized with a clear, shared goal and intentional, coordinated efforts to learn and change to achieve that goal. NICs are guided by continuous improvement methodologies such as Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles in which high leverage changes are designed, implemented, monitored for efficacy, then evaluated and refined. This evidence-based approach is intended to keep network members' improvement efforts focused on the purpose behind a change and ensure that observed outcomes drive next steps. Engaging in improvement cycles such as this within a network has the potential to accelerate collective learning; network leaders can aggregate and analyze data across testing conducted by many participants to understand more quickly what works, for whom, and under what circumstances (Bryk et al., 2015).

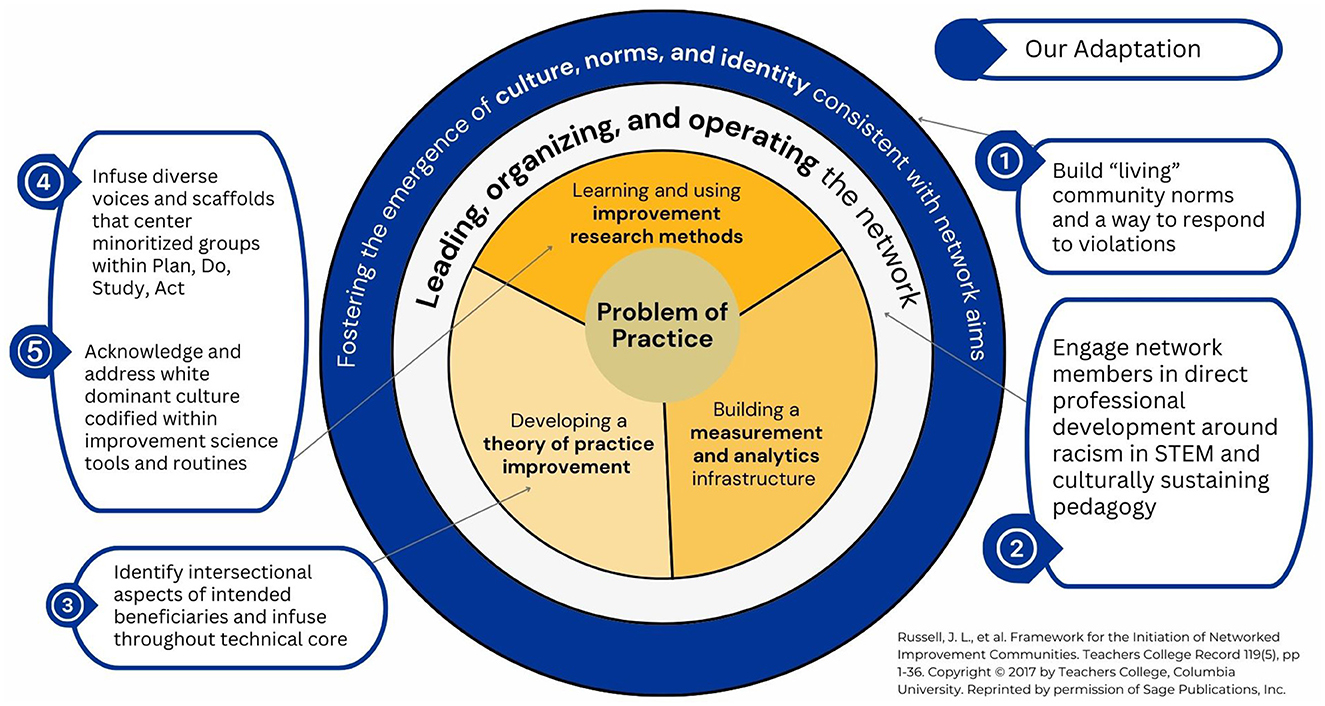

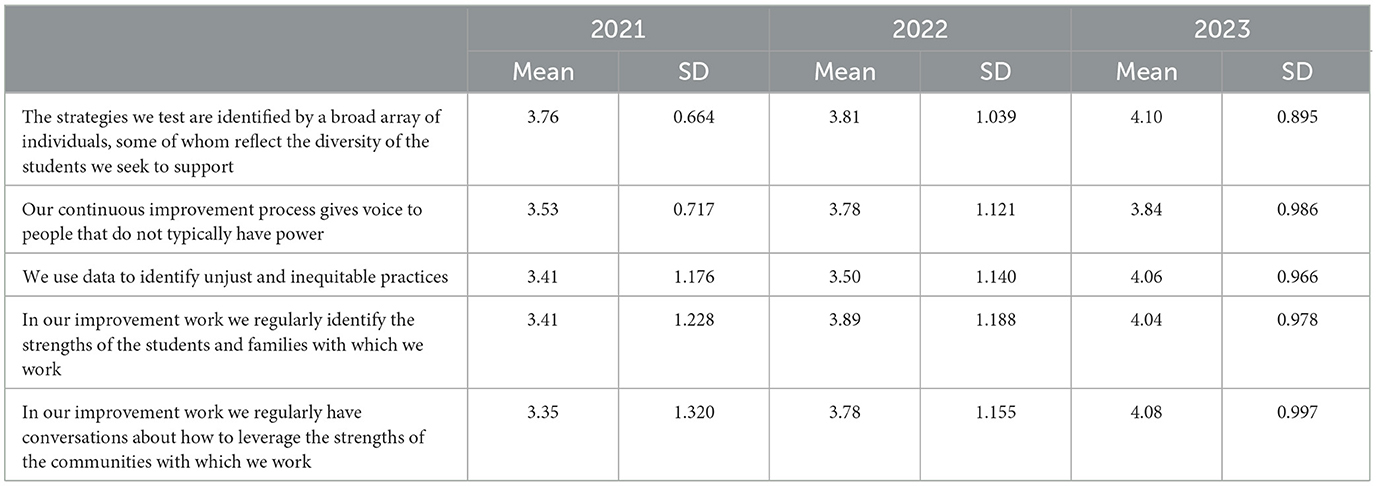

Russell et al. (2017) articulated a theoretical framework for the core domains and relationships among domains for the initiation and development of networked improvement communities. This framework (Figure 1) posited a technical core centered around a problem of practice that included development of a theory of improvement, iterative cycles of testing, and measurement for improvement. They hypothesized that this technical core was shaped by both the leadership and management practices of the network and the network culture and norms. The publication of this framework provided a conceptual structure for NIC designers and leaders to organize their design and implementation efforts of newly forming improvement networks. More recently, researchers have also developed and tested a survey tool to measure the health of a network on critical dimensions aligned with this framework and which can provide powerful data for leading conducting research on NICs (Bryk et al., under review1; Russell et al., under review2).

Figure 1. NIC initiation and development framework (Russell et al., 2017).

2.2 Racial equity in improvement science

Recently, integrating equity into improvement science work in educational contexts has been a topic of growing importance and scrutiny. While improvement science offers a robust framework for addressing educational challenges, there has been an increasing recognition that it must be accompanied by a deliberate focus on equity to ensure that all students have equitable access to high-quality education (Russell and Penuel, 2022). Coburn and Penuel (2016) note that improvement efforts that neglect equity can perpetuate disparities and reproduce inequitable outcomes, particularly for historically marginalized student populations. Consequently, there has been a call for improvement science to explicitly incorporate equity as a core principle, guiding the design and implementation of improvement initiatives (Jabbar and Childs, 2022).

In practice, the integration of equity in improvement science work in education has not been straightforward or seamless. Scholars have highlighted challenges in translating equity aspirations into actionable strategies and measurable outcomes within improvement initiatives (Bush-Mecenas, 2022; Hinnant-Crawford, 2020; Jabbar and Childs, 2022; Valdez et al., 2020). Indeed, in her recent article, Bush-Mecenas (2022) suggests that the very roots of continuous improvement in the Total Quality Control industry make it an unlikely model for centering equity rather than productivity or profitability. Attention to equity requires a deep understanding of the structural and systemic factors that contribute to disparities in educational opportunities and outcomes. Dismantling inequitable structures necessitates a critical examination of policies, practices, and power dynamics within educational systems. Jabbar and Childs (2022) instruct, “Improvement research should involve an analytical process that goes beyond understanding what or how change occurs and reveals how improvement affects (and is affected by) race, gender, structural inequality, power, systems, and democratic control in classrooms, schools, and districts” (p. 242). Therefore, the incorporation of equity in improvement science work requires intentional efforts by participants to foster a culture of equity-consciousness, to promote inclusive decision-making processes, and to engage with diverse stakeholders who have historically been marginalized or excluded from educational improvement conversations.

More recently, additional tools and frameworks for supporting continuous improvement work that center equity in formal schooling spaces have emerged from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation's Networks for School Improvement (NSI) initiative (Gates Foundation, n.d.). The NSI initiative includes a set of intermediary organizations leading over 30 improvement networks aimed at reducing disparities in a range of educational outcomes. Each network within the initiative focuses their improvement strategies on one of four areas: 8th grade on track to graduation, 9th grade on track to graduation, early warning systems, or well-matched post-secondary. Through these networks, participating schools and their intermediary partners work collaboratively to develop and test interventions, share knowledge and best practices, and continuously learn from each other's experiences. The initiative supports networks with “an unwavering commitment to equity, dedication to continuous improvement, and use of indicators proven to predict students' learning, progress, and success” (Gates Foundation, n.d.). This large-scale effort to leverage continuous improvement for equity is building protocols that use data to identify disparities and monitor progress; collaborative approaches that support a deeper understanding of the root causes of disparities and the co-design of solutions that are contextually relevant and responsive to the needs of marginalized student populations; and sharing effective practices that reduce disparities (Catalyst, n.d.; Duff et al., under review3).

2.3 Racial equity in schools and other organizational contexts

Organizations reflect the societies in which they develop (Meyer et al., 2017). Within the context of the United States (U.S.), racism and white supremacy animated the founding of the institutions that comprise the social fabric of the society, including education (Feagin, 2013; Feagin and Ducey, 2018). Okun noted that “white supremacy culture is the air we breathe” and further that “…white supremacy and racism are projects of …deep disconnection and alienation in the service of profit and power for a few people.” (Pipe and Stephens, 2023, p. 33). Such disconnections are then built into the conditioning, structures, and culture that comprise U.S. organizations, making them hard to see, name, and address (Okun, 2021; Pipe and Stephens, 2023).

Studies of racial equity in organizations, specifically educational organizations such as schools, focus on understanding organizational processes and contextual conditions that foster (or alternatively prevent) inequities, as well as the associated norms and resources (Brayboy et al., 2007; Galloway and Ishimaru, 2015, 2020). This research further takes up the importance of people—leaders, educators, policy makers— to enact the practices that mitigate inequality and forward equity to transform educational organizations, but make clear shifts from centering individuals, instead focusing on access, structures, and policies (Brayboy et al., 2007; Galloway and Ishimaru, 2015, 2020; Grubb and Tredway, 2010). Practices including recognizing and critiquing inequitable actions and associated assumptions and frames; establishing equity-focused, asset framed priorities, goals and belief systems; and enacting equity-focused organizational routines are key to equity-centered organizational change (Bragg and McCambly, 2018; Shields, 2010). Further, to foster organizational change, professional learning within these organizations should develop and facilitate safe and trusting communities, reflect upon personal biases and beliefs, and engage in authentic inquiry connected to equity within the localized context—including centering and elevating the voices and experiences of those served by the organization (Jacobs et al., 2024).

The ways white supremacy shows up in organizational contexts –and the ways it is perpetuated even by well-intentioned, equity focused leaders and educators— is not always explicitly delineated. However, Okun (2021) addressed this in naming the features of white supremacy in organizational contexts that are frequently overlooked. Okun (2021) argued that recognizing and challenging white supremacist culture is essential for fostering inclusive and equitable organizations, highlighting several key features of white supremacist culture including perfectionism, sense of urgency, defensiveness, quantity over quality, worship of the written word, individualism, paternalism, either/or thinking, power hoarding, fear of open conflict, and a belief in a hierarchical structure. These characteristics can manifest in both explicit and subtle ways, shaping organizational norms, practices, and decision-making processes. For instance, the emphasis on perfectionism may lead to unrealistic expectations and create an environment where mistakes are not tolerated. Similarly, the fear of open conflict can stifle productive dialogue and prevent the exploration of diverse perspectives (Okun, 2021).

Okun's work serves as a call to action for organizations to engage in transformative work that dismantles white supremacist culture and fosters environments that value diversity, inclusion, and social justice, and liberatory design thinking takes up such a call (Anaissie et al., 2021) Ideation, frameworks, and tools from liberatory design thinking—an equity-centered design framework expanding the traditional design thinking processes—may further contribute to improvement-focused work within organizations (Anaissie et al., 2021). This work, which focuses on equitable systems changes that promote justice and liberation connects closely with both the recognition of inequities and the holistic reimagining necessary to change organizational structures and cultures, and forward equitable learning opportunities within organizations. Relatedly, Meyer (2022) drew on Okun's work applying it to continuous improvement and the ways white supremacy might appear in organizational change attempts via continuous improvement.

2.4 OST STEM as a space focused on racial/ethnic equity

By creating socially and academically supportive learning spaces for students inadequately served by schools, out-of-school time (OST) programs and informal learning spaces offer opportunities to address educational inequities for racially and ethnically minoritized students (Gardner et al., 2009; Pittman, 2017; Wallace Foundation, 2022). STEM offers a context to consider equity and justice in terms of learning and employment (Barton, 2002). STEM OST programs may provide access to curricula, experiences, and resources not available in under-resourced schools that serve racially and ethnically minoritized students. Additionally, they may further leverage their flexibility to engage myriad topics of youth interest; many do so in ways that support positive identity development, including racial identity development (Philp, 2022). While OST programs have grown in both number and recognition, their role in the learning and experiences of youth is often overlooked and undervalued in research and improvement efforts (Afterschool Alliance, 2014).

Research in STEM OST points to the ways that many programs' specific commitments to serving racially minoritized youth—along with their capacity to be flexible and responsive to youth, family, and community needs and interests—make them prime spaces to support racial equity (Akiva et al., 2023; Valla and Williams, 2012). For instance, OST programs can focus explicitly on STEM solutions for addressing community challenges, such as access to clean water or growing food (Allen et al., 2020), and in this way, they can explicitly respond to immediate student and family needs. At the same time, OST programs are constrained by small budgets and funder influence, high staff turnover, and limited capacity. In addition, despite their potential, some research points to the ways OST programming and spaces (e.g., museums, science centers) replicate and reinforce the marginalization of racially minoritized people in STEM experiences (DeWitt and Archer, 2017; Godec et al., 2022). Characteristics of the STEM OST program such as staff identities and training, structure, and curricula matter to their capacity to create equitable and affirming experiences for racially and ethnically minoritized students.

Despite growth in research on OST, it remains a space that is underexplored in improvement science, both in terms of improvement science application and in developing more aligned approaches to the unique OST context (David P. Weikart Center for Youth Program Quality, n.d.; National Institute on Out-of-School Time, 2012). The application of improvement science and networked improvement communities in education are most prevalent in formal school settings such as in PK-12 public, private, or charter schools; districts; or higher education spaces. These formal spaces tend to have greater organizational consistency, research attention, and infrastructure to support improvement science initiatives than out-of-school time (OST) learning spaces (Stol et al. under review4). However, there is a history of continuous improvement efforts in informal schooling settings (e.g., OST programs, community-based learning initiatives, museums) that initially grew out of program evaluation efforts. Research points to the need for and the possibilities of applying data to support change in OST—a key feature of improvement science (Noam et al., 2017). In this paper, we seek to understand the potential of engaging in networked improvement to build equity in STEM. We do so through an examination of the case of one STEM-focused OST networked improvement community: The STEM PUSH Network.

3 Context

The STEM Pathways for Underrepresented Students to Higher Education (PUSH) Network is an Alliance funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) Eddie Bernice Johnson Inclusion across the Nation of Learners of Underrepresented Discoverers in Engineering and Science (INCLUDES) program. INCLUDES Alliances are NSF-funded collective impact initiatives focused on enhancing preparation, increasing participation, and ensuring the inclusion of people from historically underrepresented groups in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics careers (NSF INCLUDES, 2018, 2020). As an NSF Alliance, the goal of STEM PUSH is to strengthen the role of pre-college STEM programs in higher education admissions to create greater equity for Black, Latina/o/e and Indigenous students. Pre-college STEM programs (PCSPs) are out-of-school time programs hosted by institutions of higher education, community organizations, or other entities; they support high school students to learn and engage in STEM activities with an eye toward college and career. Established in 2019, the STEM PUSH Network ultimately brought together 40 PCSPs from across the country and introduced the use of improvement methodology in a networked approach to help these programs better serve Black, Latina/o/e and Indigenous students and to collectively break down systemic barriers to minoritized students' admission to and persistence in STEM undergraduate study.

STEM PUSH was born of both the recognition of inequities in college admissions outcomes for Black, Latina/o/e, and Indigenous students who excelled in rigorous precollege STEM programs offered across STEM disciplines and the desire to change the underlying systems creating that problem. At the heart of the STEM PUSH Network is the desire to make racially and ethnically minoritized students' experiences and accomplishments in precollege STEM spaces carry academic weight in admissions decisions as one way to broaden participation in STEM fields.

The network has three key components: (1) a networked improvement community aimed at strengthening PCSPs' capacities to serve underrepresented students and generate knowledge to the broader community and their regional ecosystems; (2) the creation of a next generation accreditation model with the Middle States Association to communicate PCSP competency to admissions offices; and (3) strategic outreach and partnership development with college and university admissions offices. In this paper, we focus on the first key component—the networked improvement community—and the hub's innovation and adaptation efforts to deeply embed equity in the work.

3.1 Networked improvement community composition

STEM PUSH leaders chose the network model for organizing its collective impact effort because it offered a structure both for supporting PCSPs in making evidence-based improvements in their capacities to serve Black, Latina/o/e, and Indigenous students in STEM and leveraging the learning from those improvement efforts to generate broader field knowledge.

The network was established in the fall of 2019 with the NSF award. The core hub team is a cross-disciplinary team with professional identities including improvement researcher, education evaluator, STEM outreach provider, data scientist, community and family engagement scholar, molecular biologist, STEM ecosystem leader, communications specialist, and research coordinator. The network recruited and selected its first cohort of 12 PCSPs in early 2020 and formally launched with a 2-day virtual kick-off event in May 2020 (initially intended to be in-person but adapted due to the COVID-19 pandemic). Subsequently, two additional cohorts of programs were recruited and onboarded in Spring 2021 (n = 18) and Fall 2022 (n = 15). PCSPs were recruited through the STEM Learning Ecosystem Community of Practice and through hub members' professional networks. To be eligible for network membership, PCSP applicants had to meet the following criteria: (1) Engage urban high school students in rigorous STEM-centric curricula; (2) Provide at least 120 student contact hours per year; (3) Have explicit goals to serve Black, Latine, and/or Indigenous students; (4) Engage students in doing STEM via hands on experiences, laboratory work, and/or mentored research; (5) Have operated for 3 or more years; and, (6) Expose students to STEM college pathways and careers. Once a program was selected for membership, they identified one staff member to serve as a STEM PUSH liaison attending all network meetings and participating in all network activities. Some programs choose to engage additional staff members as they see fit. Programs receive a stipend of $6,000 per year for participation and all costs for one staff member to attend twice per year in-person network convenings.

The PCSPs are primarily clustered in eight urban areas: Pittsburgh, Chicago, New York, the San Franciso Bay area, South Florida, Cleveland, Los Angeles, and Phoenix/Tucson. There are several programs from other areas in the midwestern and northwestern U.S. The PCSPs have significant variation on several dimensions. They focus on different STEM content areas with about 33% focused on general STEM, 25% on engineering, and 10% each on computer science, environmental science, and health/medicine. The PCSPs also have different institutional homes with 55% affiliated with universities, 12% with museums, and 33% with non-profit community-based organizations.

3.2 Initial network structures and routines

In this subsection, we detail the network structures and participation routines we first installed as we designed and implemented the STEM PUSH Network along with the approach and routines for hub reflective learning used to drive adaptation.

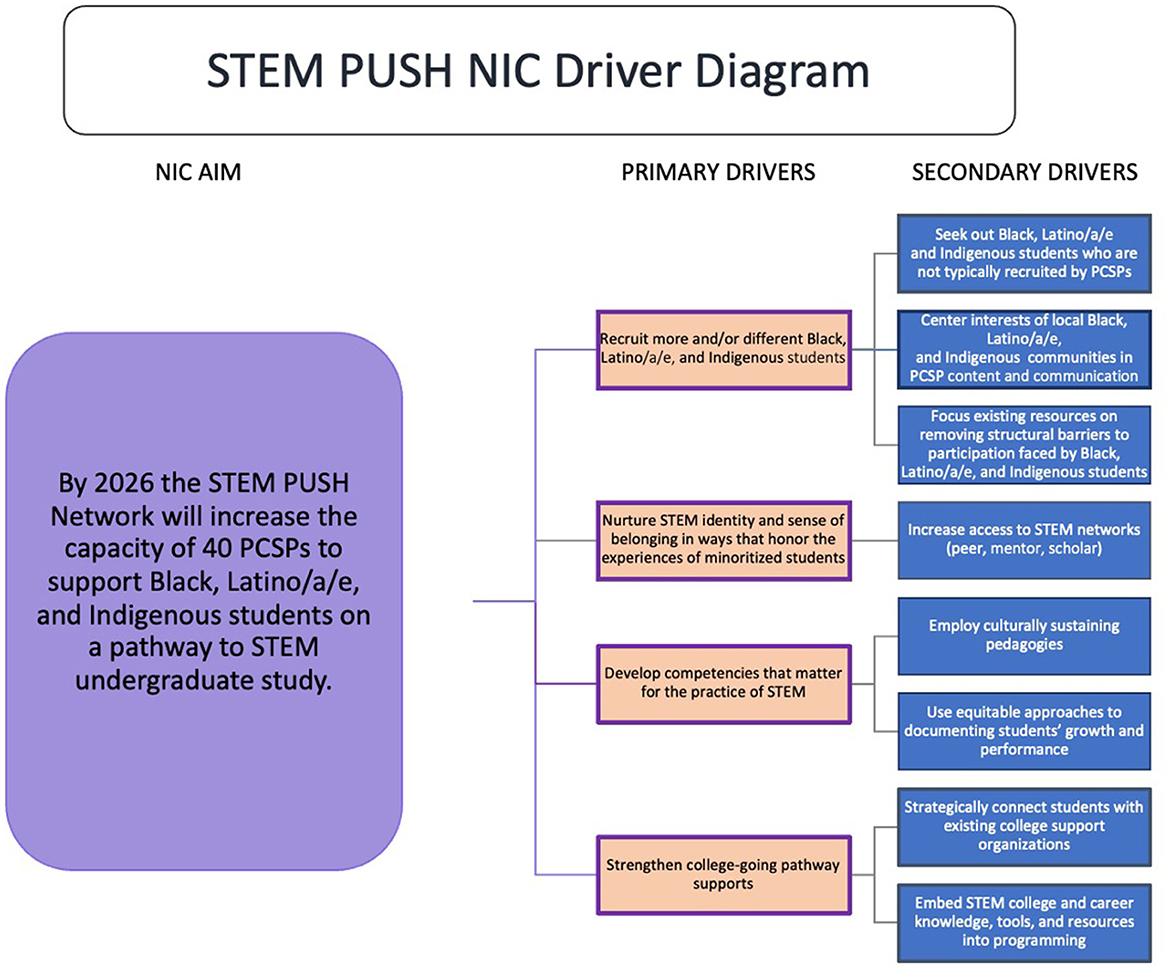

Following the Russell and colleagues' NIC Initiation and Development Framework, the network is organized around a theory of improvement as represented in the STEM PUSH driver diagram shown in Figure 2. We (the network leaders, also referred to as the “hub”) developed this theory of improvement after engaging in a collaborative and iterative root cause analysis with a diverse set of stakeholders to understand the system producing the problem (see Bryk et al., 2015). Using the insights from the root cause analysis and landscape scans of effective practices and research insights, we identified a set of primary drivers for increasing PCSP capacity to effectively serve racially/ethnically underrepresented students on a pathway to STEM undergraduate admissions. We used these primary drivers to identify secondary drivers that, if addressed, would further improve outcomes on the identified primary drivers. We organize all the improvement work of STEM PUSH Network members around this driver diagram.

The Network pursues the theory of improvement through iterative, collaborative improvement cycles in which PCSPs locate into a driver and promising change idea. PCSPs follow an iterative, scaffolded protocol to help them determine the most productive way for their program to engage in improvement work, a “sweet spot” that is both reflected in the driver diagram to advance the STEM PUSH goal and is aligned with their own program's areas of need, capacity, and potential for impact. Once settled on these “sweet spots,” programs engage in two improvement cycles each calendar year in small, collaborative improvement groups with colleagues working on similar changes. PCSP leaders use a Plan, Do, Study, and Act (PDSA) template that the STEM PUSH hub customizes for each change idea to scaffold the design, implementation, and reflective stages of the improvement cycle. Improvement groups engage in virtual monthly, hub-facilitated meetings to support each phase of the improvement cycle- Plan, Do, Study, and Act. Group members share how they will try the change within their own programming context, what they want to learn, how they will measure if the change is an improvement, the tools they will use to measure improvement, the results of their test, and—based on these results—whether the change will be adapted, adopted, or abandoned.

Upon cycle completion, each PCSP produces a change summary document that details the design, results, and learning from their cycle and the STEM PUSH hub team consolidates the findings across all tests of each change idea to synthesize what was learned about the routine, its impact, and key tools and resources that support its effectiveness. These consolidated learnings are compiled, along with individual program change summaries, and shared network-wide in a Change Idea Summary Booklet. When changes are tested over multiple cycles and identified as high-leverage, the hub builds “improvement packages.” An improvement package includes details about the tested routine(s), tips for adaptive use grounded in network evidence, and tools to support implementing the tested change and monitoring its impact, including practical measures. These improvement packages codify the network's learning and extend it to others within and beyond the STEM PUSH Network (examples are available on the STEM PUSH Network website).

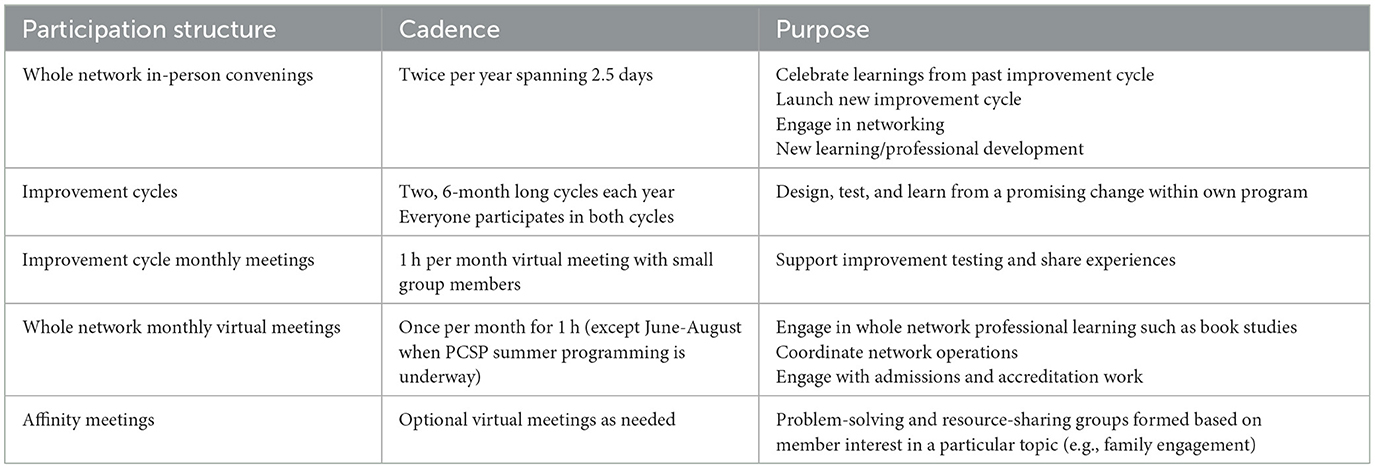

Table 1 provides a high-level summary of the network's key participation structures and annual cadence. These include the improvement cycles just described as well as whole network in-person and virtual meetings and affinity groups.

To enact the improvement cycles, the hub drew on its extensive improvement experience and field knowledge to build tools, resources, and routines that became the core of improvement work in the network. Central among these were the PDSA template that organized program's work in improvement cycles, development of high leverage change ideas for testing, an improvement group facilitator guide to support consistency across groups, and a knowledge consolidation routine and tool (Bryk et al., 2015).

3.2.1 PDSA template

The hub team adopted a standard Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) template intended to both support planning for the improvement cycle and serve as documentation for knowledge management (Bryk et al., 2015). This tool provided short prompts to support building a plan for the change and measuring whether the change is an improvement, noting key aspects of implementation of the plan, documenting results, and describing actions taken based on the results. Hub members had learned from past NIC work that certain design features were critical to support coherent planning (e.g., ensuring that testers articulate guiding questions and link these to both their hypotheses and practical measures). Like most standard PDSA templates, this tool did not include any specific centering of racially/ethnically minoritized students outside of the implicit linkages to the network aim and that which is embodied in the change idea itself. The initial PDSA template was a seven-page fill-in-the-blank document that each participating network member used with program colleagues to plan, execute, and report their improvement cycles. This template included a full page in which the change was outlined, including the change theory, the tested routine, and considerations for planning. Remaining pages included tables with areas for the improvers to add in their content for their plan to implement the change, the questions they would ask, their predictions for each, the data they would collect cued to each question, and data from repeated trials. The template also included summary questions about actions and reflections based on the cycle.

3.2.2 Change ideas

Change ideas were substantively focused on racial equity and tethered to the racial equity outcome goal of the network (e.g., using new materials and new spaces to recruit more or different minoritized students, using a discussion routine to build staff capacity for understanding racism in STEM fields, building a routine to support guest speakers to provide more relevant and equity-oriented presentations). Initially, change ideas were identified from hub member expertise, scholarly literature reviews, and insights gleaned from early root cause analysis work with a range of stakeholders (Stol and Iriti, 2021). Selected change ideas needed to be promising, potentially high-leverage actions to advance one or more of the network's secondary drivers.

3.2.3 Improvement group facilitator guide

Improvement cycles were implemented collaboratively with three to five PCSP leaders working together with a hub facilitator to test similar changes in their programs. At the outset, hub leadership developed a short facilitator guide to help the network operate coherently and ensure that facilitators had resources to guide their work with PCSPs during each improvement cycle meeting. The guide included recommended prompts before each meeting, agenda topics with corresponding facilitator moves for each meeting, and next steps for facilitators to share with PCSPs. Initially, the guide did not include any specific racial equity content as it was assumed that the equity work was embodied in the aim and goal of the individual change ideas.

3.2.4 Consolidation tool and routine

At the conclusion of each cycle, PCSP leaders extracted key highlights from their full PDSA template to produce a change summary (crafted in a hub-designed template) that was then included in a Change Idea Summary Booklet and shared with all members of the network. The change idea summaries were also used to structure synchronous presentations and discussions during end of cycle “Celebration of Learning” moments in full-network meetings.

3.3 Initial approach to explicit equity integration

Although the overarching STEM PUSH Network goal explicitly targets greater equity, and the theory of improvement embodies it, we knew during the network design phase that ensuring equity was centered throughout the work would be a challenge. Networks and improvement science have an inconsistent record in functioning as vehicles for creating systemic, equitable change (Diamond and Gomez, 2023; Russell and Penuel, 2022). Knowing this, the STEM PUSH hub sought to intentionally design for equity and develop hub leadership capacity to embed and weave equity practices into every improvement experience. We sought to systematically embed more cognitive and social tools and routines to ensure an equitable culture in which to do the improvement work. Drawing from research on racial equity in schools and other organizational contexts, we further recognized that to build a network that sought to dismantle racial inequities in STEM would require both recognition of current racist structures (Feagin and Ducey, 2018) as well as leadership, structures, policies, and practices that were equity focused (Brayboy et al., 2007; Galloway and Ishimaru, 2015, 2020; Grubb and Tredway, 2010). Thus, fostering an equity centered network would require that we understand the ways white supremacy manifests (Okun, 2021) and build a community that would allow members to develop trust, reflect on their biases and beliefs, engage in authentic inquiry—all the while building beyond individuals toward the broader system (Anaissie et al., 2021; Jacobs et al., 2024; Brayboy et al., 2007). We hypothesized that an equity-minded culture would ensure that the improvement tools were used in ways that advanced our equity goals.

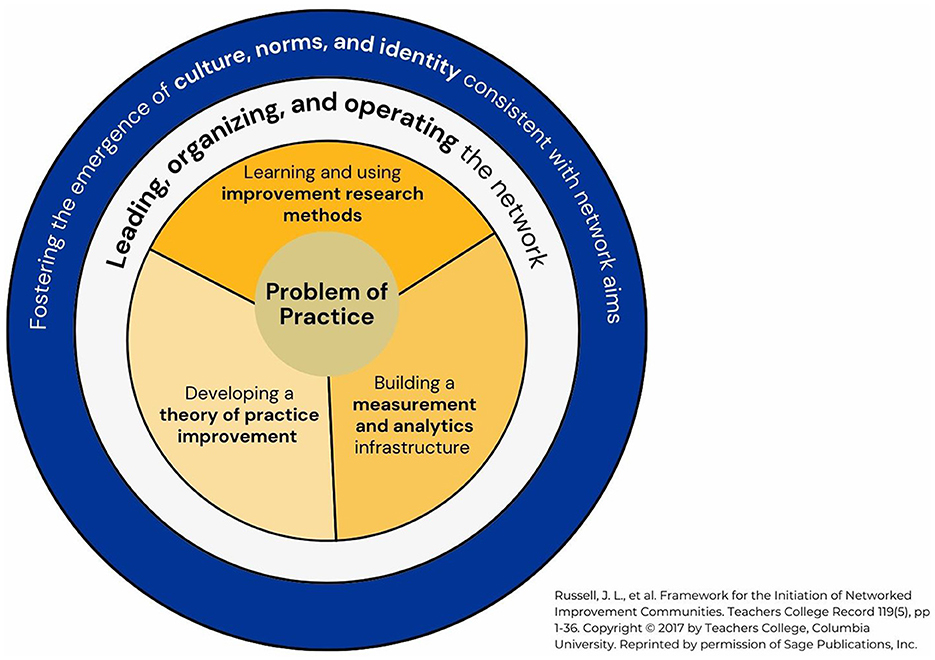

Turning back to our organizing NIC Initiation and Development Framework (Russell et al., 2017), we mapped our hypotheses about how we would need to elaborate tools and routines to explicitly infuse equity into the work (see Figure 3). We anticipated the need for more explicit tools and routines to ensure that how network members worked together was also equitable and inclusive as we pursued our equity goal. Further, we anticipated the need for leadership routines that focused not only on monitoring attainment of our equity goals and how we worked together, but more specifically, how our leadership practices shaped an equity culture and processes in the enactment of the work. And although not explicit in the NIC Initiation and Development Framework, we expected that to truly embed an equity culture, the hub and network members would need to engage in ongoing, direct professional learning about race and racism as well as our own positionality and role in upholding racist structures (Anaissie et al., 2021; Jacobs et al., 2024). This line of direct professional development outside of improvement science protocols was an early and ongoing focus of our hub and network efforts.

Figure 3. Hypothesized equity elaborations needed for STEM PUSH's initial design and implementation.

When we were building these tools (2019–2020), there had not been published work around infusing equity within NIC infrastructure in the way we thought needed to occur. Based on literature around equitable practices within organizations writ large, we hypothesized that we would need to spend time in our network defining equity and discussing race, develop and implement explicit equity training with hub and network members, and establish equity-focused community norms to guide and evaluate practice and processes for defining, discussing, and learning about race and racism (Anaissie et al., 2021; Bragg and McCambly, 2018; Jacobs et al., 2024; Shields, 2010), and hub reflective practices focused on dimensions of equitable culture and process (described in the Section 4). We describe these innovations to our tools and routines below.

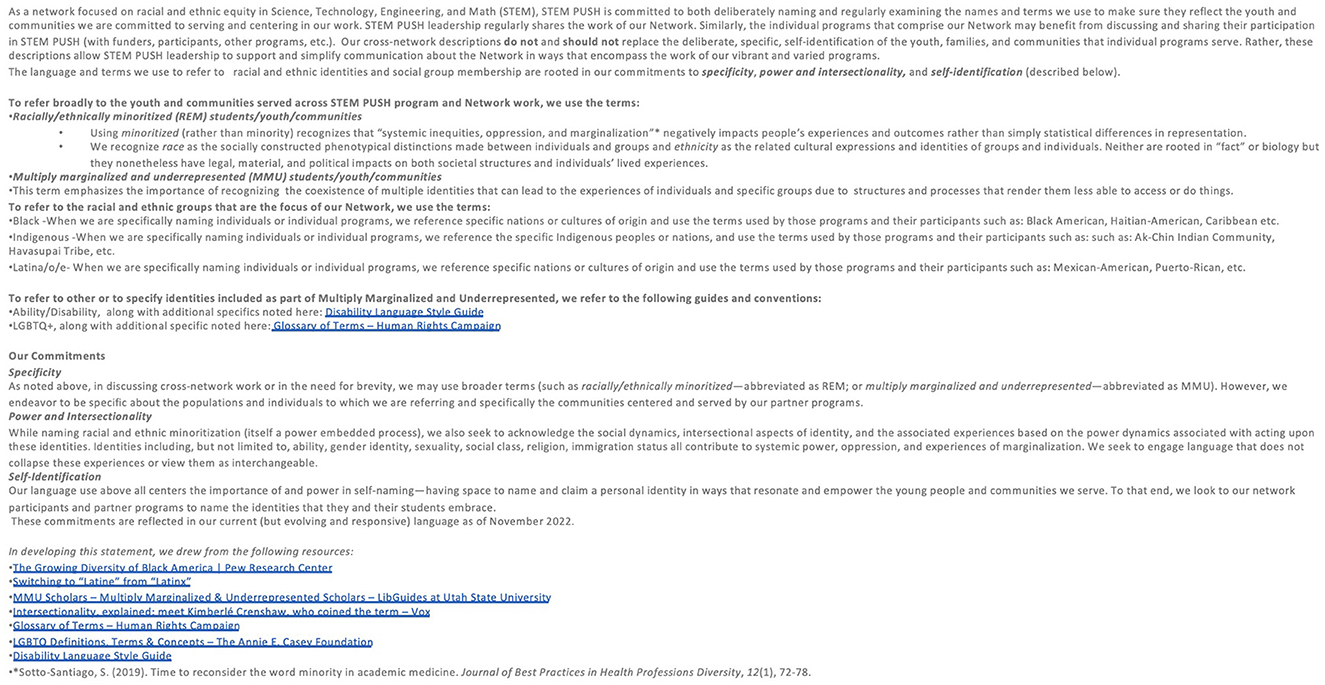

3.3.1 Defining equity and discussing race

Institutions of higher education, funders, and other project stakeholders use their own specific language to describe underrepresentation. As a new network, we prioritized using humanizing language that would best articulate our shared goals, and would not center white, Eurocentric framings of race. To this end, we developed a common language for our network. For instance, rather than draw specifically from the terms used by the National Science Foundation (the key funder of the network), we discussed the importance of considering power, structures, and processes—and not just the numeric representation of specific racial/ethnic groups. For instance, from the onset of our work we use the term minoritized, rather than minority. In addition to specific language, we further made clear in both internal and external communication the centering of race/ethnicity-specific underrepresentation—rather than noting underrepresentation in ways that could be unclear or center gender or other categories of exclusion or minoritization. Thus, in our work we used the language of “racially/ethnically minoritized students in STEM” rather than the more common NSF language of Underrepresented Racial Minority (URM).

3.3.2 Equity training

As a network with a hub team that is predominantly white, female and university based designing for PCSP leaders comprising people from across many different racial/ethnic identities, disciplinary backgrounds, and varied professional roles, we had different experiences with and understandings of approaches to work focused on racial equity (Galloway and Ishimaru, 2015, 2020; Grubb and Tredway, 2010). To support the development of the network, we engaged in training and collective study to understand the impact of race and racism in STEM, to clarify the ways we as leaders might center and approach this work, and discuss the ideas, terms, and theories we would apply in working with PCSPs. We engaged common readings, training sessions, and ongoing discussion at leadership meetings about the role of race and equity in the project, but more broadly in all our work and practice. The goal was to not only become familiar with theories of racial equity, but to develop understandings and practice that would allow any member of the leadership team to suggest, design, and engage in race-centered work, rather than this responsibility falling to individual team members, and specifically team members with racially/ethnically minoritized identities. We furthered this work through direct, equity-focused training with the PCSPs in the network. Similar in design to the leadership training, we focused on common concepts and terms, understanding the impact of race and racism in STEM, identity and positionality, and supported discussion around common readings and viewings.

3.3.3 Developing norms

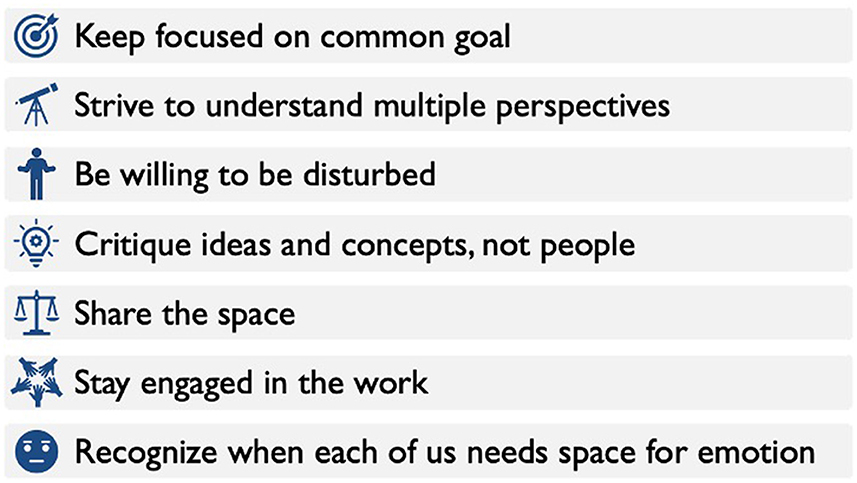

A critical part of our design for engaging in racial equity work with a network of committed but diverse partners focused on the development of community norms. We constructed norms that addressed how the network would engage with each other during our collective time together. We built the norms (Figure 4) from a variety of sources, including our own prior experiences teaching and engaging in other groups. These norms drew from our understanding of equity-focused organizational change (Bragg and McCambly, 2018; Shields, 2010) and would ground all our joint work as well as help establish equitable social processes for how we enacted the improvement work.

With these tools and routines to enact continuous improvement established, we engaged the PCSP leaders in basic onboarding to the network (e.g., “Improvement Science 101,” “What is STEM PUSH?”). From the onset of their participation in the network, PCSP leaders were introduced to the STEM PUSH equity goals, the theory of improvement, and the network norms. As each new cohort was onboarded, we invited new members to reflect on the norms and discuss and change them. In addition, we trained PCSP network members on culturally sustaining pedagogy and practice—deliberately connecting their structures, curricula, and practices to the racial identities and experiences of their students.

PCSP leaders then engaged in facilitated improvement groups where they selected a change idea their program would test from a menu of change ideas based on their needs and their individual areas of power and influence. The improvement groups brought PCSPs together around common change ideas that each member was testing. PCSPs used the PDSA template to plan, enact, and reflect on their use of the change idea and received support from PCSP peers in their group and from their hub facilitator. Meetings were organized to support PCSP leaders at each stage of the PDSA cycle and facilitators used similar meeting agenda and support approaches. At the conclusion of each cycle, PCSP leaders completed a written summary of their test (what we call a change summary), and this was incorporated into the Change Idea Summary Booklet to support sharing across the network and outside of STEM PUSH.

In what follows we articulate how we planned for the improvement work in the network, how we implemented it, how we studied the work, how we consolidated what we learned, and finally, how we acted by further adapting and elaborating the tools and routines to ensure that equity was not simply a goal but an integral part of all aspects of the improvement work.

4 Methods

In this section, we detail the data sources and analytic approaches we used to learn from our NIC work, and specifically to understand how well our work was centering and advancing racial equity in the network. First we describe the data sources we drew upon and then detail the analyses and analytics routines we employed to reflect on the relationship between the tools and routines of STEM PUSH and indicators of equitable practice.

4.1 Data sources

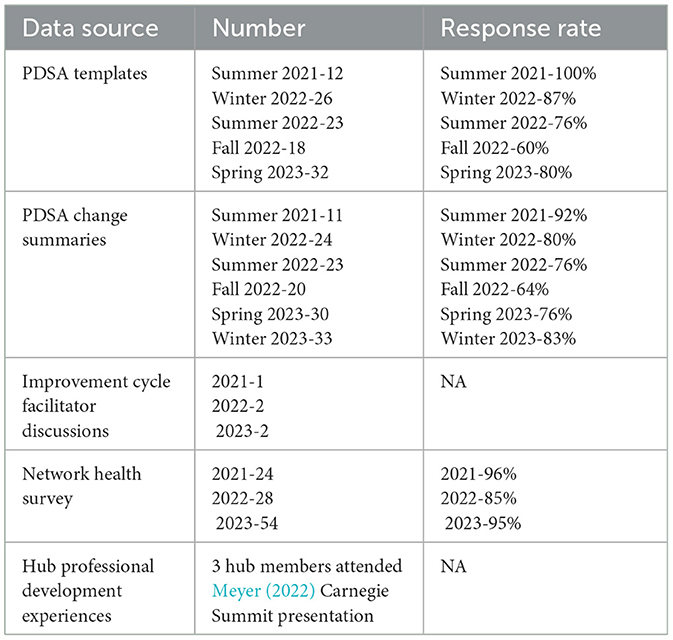

The hub team drew on five key data sources to monitor and reflect on our tools and routines. We describe each in the paragraphs below and provide details in Table 2.

4.1.1 PDSA templates

Each PCSP completed a PDSA templates for each improvement cycle. These templates included scaffolds for the following dimensions: (1) Change theory; (2) Connection to drivers; (3) Change idea description; (3) Plan to implement the change; (4) Questions they want to answer through the testing; (5) Predictions for each question; (6) Practical measures; (7) Data for each question; and (8) Action steps (adapt, adopt, and abandon). Primarily intended to support the design and implementation of the improvement testing, the templates were generally “in process” artifacts.

4.1.2 PDSA change summaries

At the end of each cycle PCSPs summarized their cycle of testing in a short narrative that the hub compiled with other programs' summaries and organized by change idea topic into a Change Summary Booklet. These booklets were available digitally to all network members and were intended to help spread learning across the network. The template for change summaries included scaffolds for the following dimensions: (1) Tested change; (2) Relevant program context information; (3) Adaptations to the change idea during implementation; (4) What was learned; (5) Action steps program will take; (6) Resources and tips.

4.1.3 PDSA facilitator discussion notes

At the end of each cycle, improvement group facilitators engaged in a reflective debrief about PCSP leader attendance, engagement, cycle learnings, and the extent to which cycles made progress toward our aim. Hub members took detailed notes during these discussions, and we used them to understand facilitators' perceptions of the integration of equity in the design and execution of testing cycles.

4.1.4 Network health survey

The hub administers the network health survey annually in two parts (part in the fall and part in the spring) to all network participants. Much of the survey is cued to the network initiation and development framework (Russell et al., under review2; Bryk et al., under review1) and asks about the range of dimensions known to be critical for high functioning networked improvement communities such as “hub trust” and “confidence in improvement science tools and skills.” Relevant to this study, this network health survey assesses the constructs “continuous improvement for equity” through a set of seven closed-ended statements in which respondents indicate their level of agreement on a 5-point scale from “do not agree” to “strongly agree” and “culture of equity” through a set of five closed-ended statements using the same response scale (Bryk et al., under review1; Russell et al., 2017, 2021; Russell et al., under review2). In addition, these surveys ask members to assess the network's adherence to equitable community norms.

4.1.5 Professional readings and conferences

As noted above, hub members included educational evaluators and researchers with particular expertise in studying improvement networks. These team members routinely attend the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching Education Improvement Summit where there are robust opportunities to learn about improvement science and networked improvement communities and to reflect on one's own improvement work with colleagues from around the world. In addition, the hub team routinely identified and read emergent literature on improvement science and NICs to stretch our thinking and support reflective practice. Particularly relevant to this study is a session that STEM PUSH hub members attended at the 2022 Carnegie Summit which was later published in The Unboxed, Meyer (2022) drew on Okun's (2021) characteristics of white supremacy in organizations to critically analyze continuous improvement practices and then offered moves to resist and reimagine. For example, Meyer translated Okun's “paternalism” characteristic as underutilization of a co-creation process in improvement work, limiting or constraining stakeholder engagement, and making plans without voices of those who will be implementing. Meyer also suggested that Okun's “superiority of the written word” as a characteristic of white supremacy might show up in improvement work as stringent Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle documentation requirements, overemphasizing written products or equating these with what has been learned, and undervaluing reflection and dialogue as legitimate forms of learning.

4.2 Analyses and analytic routines

The STEM PUSH hub iteratively analyzed and reflected on both how the structures, tools, and routines put into place were working to build a healthy network and how we were making progress on our aim. The hub met weekly for formative insights that shaped in-cycle responses and at the end of each cycle to reflect on structures, tools, and routines to determine whether we needed to make modifications to designs or implementation.

4.2.1 PDSA cycle artifact analysis and reflection

We analyzed PDSA templates and change summaries qualitatively to understand how equity and the network's equity aim was being advanced in the improvement cycles. At the end of each cycle, improvement group facilitators reviewed the templates and the change summaries to identify whether and in what ways supporting equitable STEM learning for Black, Latine, and Indigenous students was addressed. Facilitators reported their observations and insights during end-of-cycle debriefs.

In reflective discussions after the first two improvement cycles, improvement group facilitators noticed that improvement group meeting discussions about improvement plans, implementation, and cycle learning did not explicitly mention racially minoritized students and the results of improvement cycles, as evidenced in written PDSA documentation, did not specifically attend to how minoritized students were affected by the change. These documents and discussions instead referred to all students. PCSPs have significant variation in the racial diversity of their student participants, with some almost entirely serving minoritized students and others having more heterogeneous composition. In early cycles, improvers focused on how the change affected students broadly, rather than specifically focusing on minoritized students.

4.2.2 Network health survey

Using descriptive statistics, we analyzed the close-ended network health surveys; and the hub team collaborative identifies the implications of these data for network structures and routines.

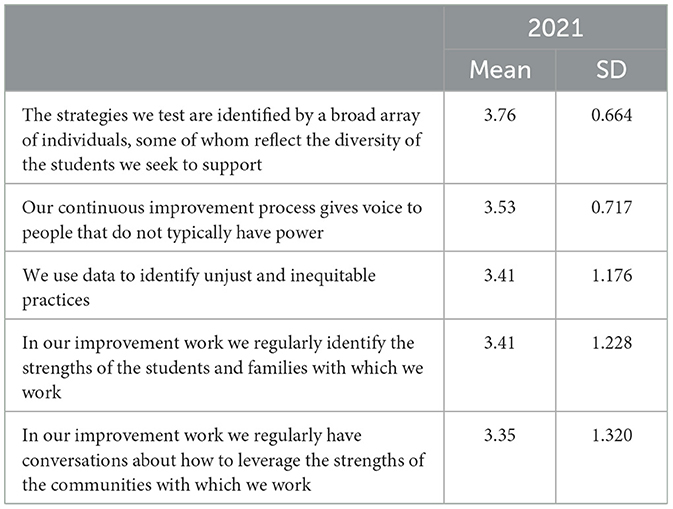

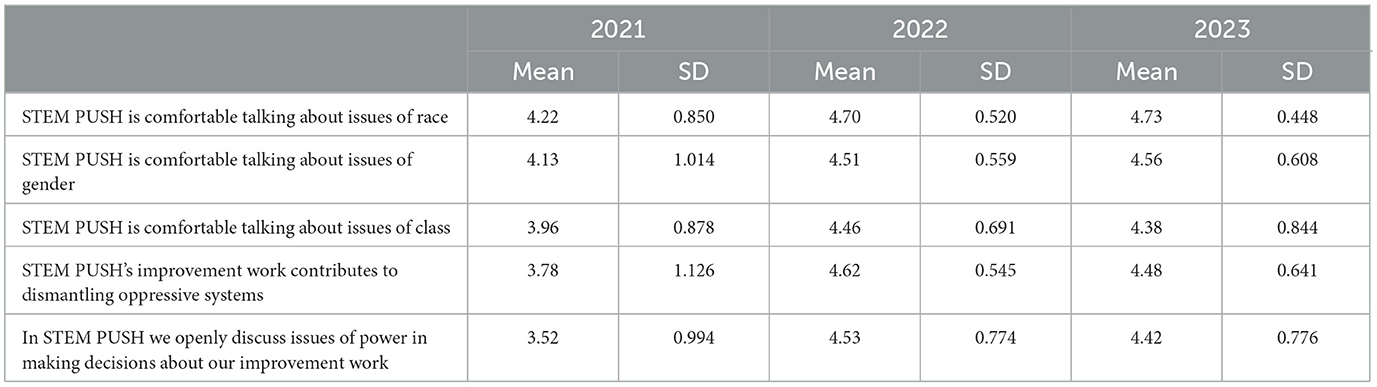

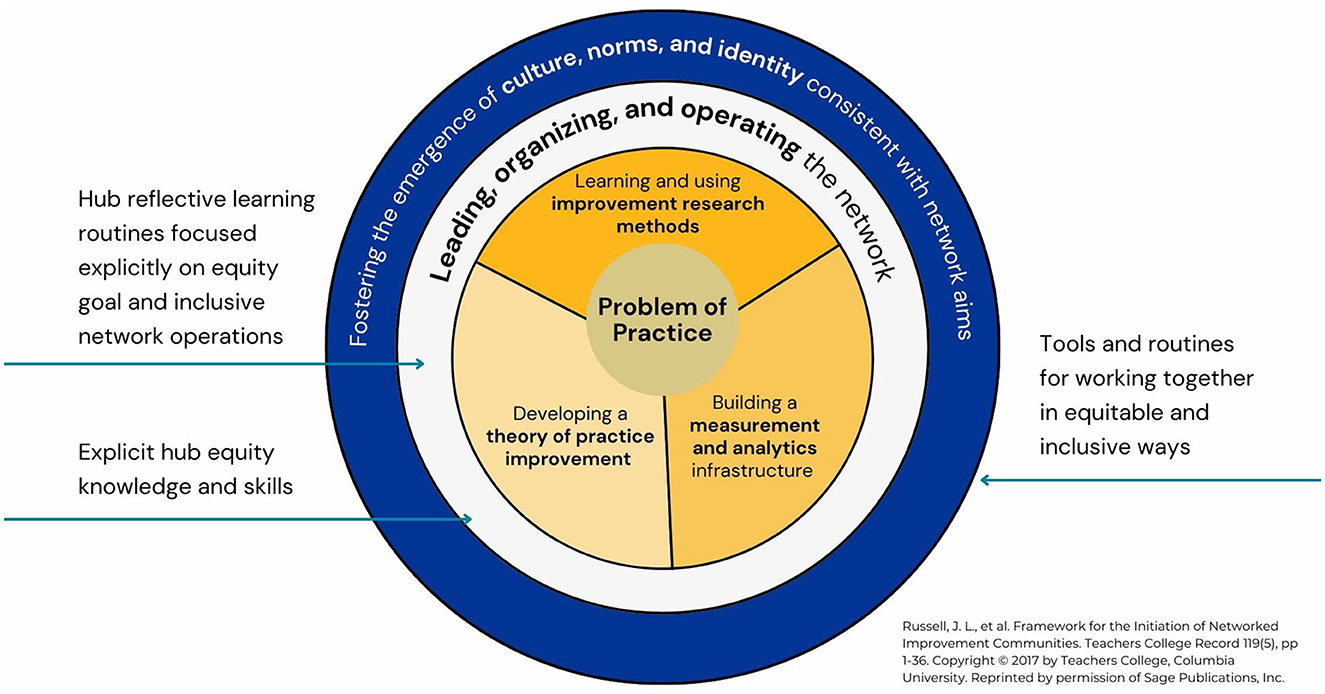

In Fall 2021, network members responded to the continuous improvement for equity items (Table 3). At this time, network members had been collaborating for 5 months and had engaged in one improvement cycle. These data indicated to us that there was significant variability in the foci of conversations happening in improvement groups around the assets of the students, families, and communities that programs serve and the extent to which data are used to identify unjust practices.

Open-ended survey items were analyzed using thematic analysis (Braun and Clark, 2006) and revealed that several participants observed that while the network is focused on minoritization based on race and ethnicity, these students often have additional identities that are also minoritized and that intersectionality is important for understanding how systems must change to better support students. One comment noted, “I think this [the work of the Network] is super incredible for racially/ethnically minoritized students. I do believe that improving our programs will encourage more Black, brown, and Indigenous students to go into STEM college or careers. A place for growth for the STEM PUSH Network is discussing intersectionality and how racially/ethnically minoritized students each have their own experiences based on their gender, socio-economic class, abilities, etc.”

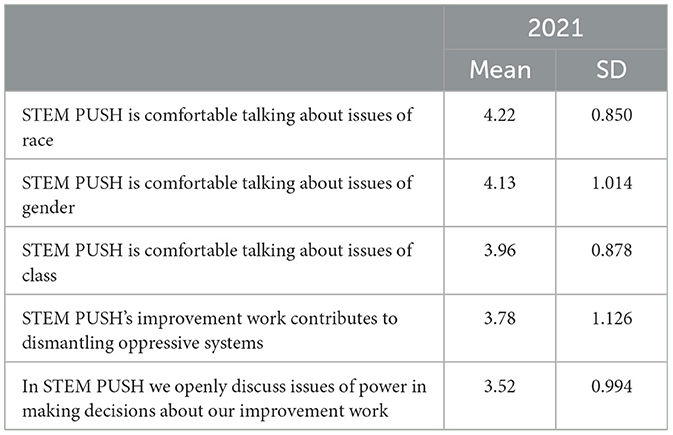

Close-ended data (see Table 4) supported this perception; network members reported a stronger STEM PUSH culture around talking about issues of race and racism than gender and class. Further, we observed tepid agreement with items about STEM PUSH contributing to dismantling oppressive systems and discussing issues of power in the work. The hub marked these as critical foci for our own improvement as leaders of the network.

Several members of the hub team engaged with the Meyer (2022) session at the Carnegie Summit and then shared the session artifacts with the full hub. The PDSA artifact analyses and reflections, the network health data, and the Carnegie Summit experience led to the recognition that we needed to more carefully interrogate the foci, tools, routines, and norms of our work. These evidence-based reflective activities helped the hub recognize where existing practice did not adequately support the network's equity goal. As a result, we shifted from a focus on outcomes to a focus on process and, specifically, how equity could be further scaffolded into tools and routines in the improvement science and social process layers of the framework.

5 Findings

After engaging as a network for a year, we recognized that while racial equity was part of our work, it was not truly centered throughout; it was the topic and content of the work but had not fully permeated the structure and processes of the continuous improvement itself. We came to this realization based on a combination of data analysis, hub professional development and reflection, and the iteration built into change cycles as described in the Methods section. Specifically, analysis of PDSA templates and change summaries, several PDSA facilitator reflective debrief discussions, data collected from network participants on an annual network health survey, and professional development and reading led us to the recognition that as a network we needed to expand and adapt our practices and routines to better forward our overarching racial equity goal.

Part of our hub practice is to iteratively reflect on data to improve our network design and function. As we reflected on our PDSA cycles, member experiences communicated in the network health survey in Fall 2021, and overlaid this professional learning session upon our reflections, we realized several important things about our work: (1) We had not yet built equity into improvement cycles and data use; (2) The scaffolds for data analysis and sense-making were not consistently driving attention and discussion to issues of equity; we were not yet elevating the voice and assets of those we intend to serve; and, (3) We had not adequately infused the intersectional nature of identities and minoritization into the network.

To begin to infuse equity more fully within the improvement science processes, we identified the weaknesses in our tools and routines and developed mitigating actions for each. In the segments that follow, we highlight five ways we adapted our design or implementation to better infuse racial equity into our network's improvement processes (see Figure 5).

5.1 Adaptation #1: build “living” community norms and a way to respond to norm violations

While traditional improvement science frameworks in education offer principles to guide the work, they lack explicit community norms within which those principles will be enacted (see Bryk et al., 2015 for improvement principles). From the outset, we recognized that as a hub, we would need to build a safe space to fail quickly; we would need to nurture a culture in which power dynamics were examined, diversity of thought was honored, and trust would be intentionally established. The network initiation and development framework centers trust (network members' trust of each other and the hub) as a critical component to establish early in the work. Trust then becomes a critical foundation for the improvement work (Russell et al., under review2; Russell et al., 2017).

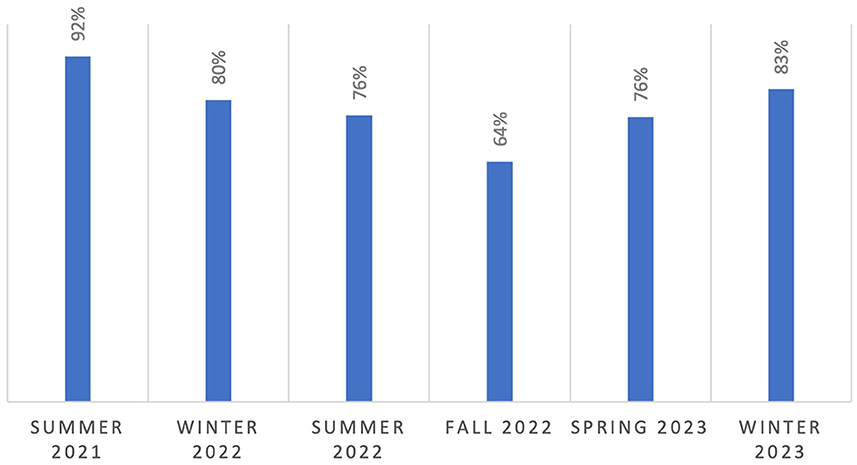

Our initial norms were the product of collective contribution by the hub—developed from our practice, our professional knowledge, and our experience in other communities (e.g., classes and other collective learning spaces) around creating equitable spaces. The STEM PUSH norms reflected our best understanding of what incoming PCSP leaders might need to establish relationships, engage in collective work, and share space, as well as understandings from research on developing and fostering racial equity in organizations (Galloway and Ishimaru, 2015; Jacobs et al., 2024; Shields, 2010). We wanted to make sure the norms were truly “living” norms that reflected our community needs and the people involved. As the network grew, we reintroduced the norms with the onboarding of subsequent PCSP leader cohorts, providing space to comment on and introduce new norms. The inclusion of a second cohort in 2021 led to an additional norm about “respecting each other's time” and recognizing when we need space “for a pause or to process.” In addition, a specific group discussion in which norms were violated led us to recognize that we did not have a response protocol for such a violation. This prompted our addition of a new norm, “Apologize and work to repair damage if you violate a norm.” We continue to open space for reflection on and revision to our STEM PUSH norms, ground our work in them at the beginning of all network meetings, and assess perspectives on our adherence to norms periodically on network surveys. Early in the network's development, we measured norm adherence after each network engagement on a three-point scale from “regularly followed,” “occasionally followed,” and “rarely followed.” This allowed us to make quick adjustments to our prompting and plan additional facilitator moves. After a year of network operations, we moved to an annual cadence for ongoing monitoring of these data with very high rates of reported norm adherence (ranging between 83 and 100% for “regularly followed”).

We found that the initial goals of these norms—creating shared understanding and commitment, developing trust, establishing a safe space, and facilitating equitable engagement dynamics—remain important to centering our network's overarching racial equity goal. Through the PCSPs experience and engagement, we learned that addition to and adaptation of these norms was necessary to demonstrate that they were community norms and not just the hub's norms. Learning to address norm violation was essential to maintaining the trust needed to engage in racial equity work and improvement work (Jacobs et al., 2024; Okun, 2021; Russell et al., 2017).

5.2 Adaptation #2: engage network members in professional learning around racism in STEM and culturally sustaining pedagogy

We started our work as a hub team with shared readings and professional development focused on understanding race and racism, seeing ourselves as racialized beings, and considering the connections between our backgrounds, experiences, and racism and oppression in STEM. Our onboarding work with PCSPs was similar, including readings, video training, and program application activities focused on racism in STEM and understanding the importance of culturally sustaining pedagogy and practices for achieving program and network goals. Much of this work was designed to build a shared understanding among PCSP leaders and establish a baseline for common terminology to support the broader work. Our initial intent was to position this content as professional development occurring during onboarding and at twice annual convenings.

STEM PUSH PCSP leaders come from a variety of identities, lived experiences, and professional backgrounds, have had a wide range of training, and bring to the work a varied knowledge base. Therefore, their understanding and application of these ideas varied greatly. We saw this variation in their discussions and participation throughout network activities; in addition, we saw that this variation was not exclusive to PCSP leaders, but also in the hub as expressed in their facilitation of conversations around this content. PCSP leaders also reflected in surveys and direct conversation that they were interested in learning more; they wanted to have more discussions, engage with more content focused explicitly on race and racism in STEM, learn more about culturally sustaining practices, and examine other equity-focused frameworks. They noted both a need for better understanding as well as a desire to leverage the opportunity to have these discussions with similarly committed peers. Indeed, many PCSP leaders did not have other spaces where race and racism in STEM were explicitly discussed. In response to both the identified needs and PCSP feedback, we developed additional network-wide professional learning opportunities focused on expanding program leaders' understanding of minoritized students' experiences in STEM using common readings (book study) and discussion, sharing existing tools (such as the NSF-funded STEM Teaching Tools; Bell and Bang, 2015), and supporting programs to share network resources with their own staff and students. PCSPs leaders have used these resources in their own programs, such as engaging STEM Teaching Tools for staff professional development or sharing the books and strategies around book study with their colleagues to engage in discussions about racism in STEM.

This regular professional learning is now an ongoing part of both hub and participant experience as we continuously engage with deeper understanding of systems that produce the STEM experiences of minoritized students. This explicit training takes time and bandwidth, both of which are limited for hub and network members. Balancing the need for explicit training with the time and effort needed to execute meaningful improvement cycles within bounded PCSP leader bandwidth has been an ongoing and careful consideration. The data do suggest, however, that this training has contributed to network members' increased sense of confidence in engaging with issues of equity and justice and examining their own practices from an equity perspective, both of which increased by 1/3 of a scale point (on a 5-point agreement scale) between the first and second administrations of the network health survey.

We found that challenging assumptions and continuing to learn about the impacts of racism in both STEM and improvement science must be ongoing—for both hub and network members—as a key part of racial equity work (Meyer et al., 2017). While we can enact equity-focused routines—there is no end point, and the change and development must be ongoing and deliberately articulated for all organizational members (Galloway and Ishimaru, 2015, 2020; Bragg and McCambly, 2018).

5.3 Adaptation #3: clearly define the intersectional dimensions of the youth we intend to benefit

Three data sources suggested that for equity to be central throughout the network we needed to name the intended beneficiaries of our work more explicitly than we had initially done and do so with an intersectional lens.

1. The hub team engages in regular reflective debriefings on partner interactions. Within these conversations, several hub members reported that network members had raised questions about whom the network means by “Black and Brown students” and by “racially/ethnically minoritized students,” (the language we were using to describe the young people on which our work is focused). Network members were unsure of which students “counted” as “Brown” and wondered about the specific racial and ethnic identities that the network intended to serve.

2. As the work of the network progressed and grew both in size and the racial and ethnic identities of youth and communities represented, we recognized the importance of communicating to audiences both within and beyond our network; our initial language to communicate our focus was not serving our network because it did not fully represent all participants. For example, the network expanded by adding a new cohort which included programs explicitly focused on Indigenous student populations, a demographic that had not been explicitly named or represented previously in the network.

3. Finally, as shared in an earlier section, open-ended comments on our annual network health survey highlighted the absence of an intersectional lens to our conception of minoritization in STEM. Combined, these data made it apparent that we needed a clear, specific, and intersectional shared understanding and corresponding language around who we intend to benefit from our collective work.

The hub responded to this lack of clarity in several ways. First, as a team, we revisited our intended beneficiaries, the language we use to communicate about the student populations our work is intended to benefit, and how intersectional identities influence minoritization within STEM. We moved away from “Black and Brown” to “Black, Latina/o/e, and/or Indigenous” as descriptors. We did this for several reasons. First, we wanted to be specific about the racial/ethnic groups that we intended to support due to the evidence of under-representation of these groups in STEM fields. Second, the use of “Latine” was an intentional effort to include minoritization based on gender as an important intersectional identity.

Relatedly, we constructed an equity statement to name our intended beneficiaries that was reviewed, discussed and revised with the entire network. After feedback, we moved forward with language centered around specificity, power and intersectionality, and self-identification. The most significant changes were reflected in our shift from “racially/ethnically minoritized” to “multiply marginalized and underrepresented” and from “Black and Brown” to “Black, Latina/o/e, and Indigenous” to refer to the intended beneficiaries of the work. Figure 6 shows an image of the complete equity statement.

We updated all our materials with the new shared understanding and language, including our website and newsletters, as well as all internal documents that organize and drive the work daily. Finally, we implemented training with hub and PCSP leaders around intersectional identities in STEM. This training included an introduction to and use of the identity wheel (University of Michigan Equitable Teaching, n.d.); all network members had the opportunity to reflect on their personal identities and consider how those identities intersects with the students they serve in their programs.

We found that clarifying language and increasing activity around the intersectionality of oppression strengthened both hub and network members' commitment to and ongoing activity around these ideas and the ways they manifest in their program. Individual PCSPs have indicated that since these changes they have employed this language in their own documents as relevant, particularly as connected to funders and other outside stakeholders. Further, a few programs have used identity wheels and associated activities around identity to work with their staff and support their understandings of intersectionality and its importance in working with multiply marginalized and underrepresented youth. After incorporating the new equity statement, training, and infusing of this more nuance conceptualization into our improvement work, we observed significant increases in the intersectional aspects of our network health equity culture survey items. For example, levels of agreement on survey items assessing participant perspectives of STEM PUSH Network's comfort with discussing issues of race, gender and class all increased year-over-year (see Table 5).

5.4 Adaptation #4: adapt improvement group tools to focus explicitly on Black, Latine, and/or Indigenous student, family, and/or community experience of change

Engaging in change ideas is a core part of the work in the network. Initially, the STEM PUSH change ideas were drawn from research and content from our earlier root cause analysis. The ideas were designed by the hub because we believed they would be high leverage for programs and reduce the cognitive load of PCSP leaders trying to learn about STEM PUSH, learn improvement science, and design and execute a cycle at the same time. However, network health survey data, hub reflective debriefing routines, and our analysis of PDSA cycle documentation signaled that early improvement cycles, while testing changes grounded in equity, were not implemented in ways that would truly center and drive impact on equity. We noted that the voices of minoritized youth and their families were absent from the work. Our improvement cycle discussions and data typically did not apply an intentional lens that could bring into relief how students of minoritized racial/ethnic identities experienced the change we were testing, and further how the changes might support them, their families, and their communities. We recognized that the localized context and the voices of minoritized youth and their families and communities needed to be part of every aspect of the PDSA cycle from the design to data analysis (Jacobs et al., 2024), and that further these voices needed to be systematically included in our tools and practices (Brayboy et al., 2007).

To address this gap, we deliberately engaged programs in the identification and development of change ideas. We established design teams composed of hub members and program leaders to develop the second round of change ideas. These teams focused on areas identified by programs as critical opportunities for program improvement that were likely to move us toward our shared aim. The co-design model allowed programs to draw from their own program needs and the experiences of the youth and communities they serve. At this time, we introduced empathy interviews as a tool to better solicit and incorporate the voices of minoritized youth. Program leaders then used empathy interviews to bring the perspective of program participants minoritized students and program alumni into the design work. It is important to note that the STEM PUSH Network works directly with the adults who staff these programs but not with the youth themselves. The network was organized and obtained Institutional Review Board approval that does not include direct work with youth by the hub. Thus, work with youth occurs through the adult network members.

As we considered the importance of youth involvement beyond the design of the process, we added new questions to the PDSA template to support programs to be explicit about the involvement of minoritized youth:

• How might you engage youth in this improvement effort, beyond gathering data from them?

• Is it possible to create space for youth agency in the design, implementation, and/or analysis of this change idea? (For example, engaging students to understand their current college-application process and barriers and/or co-designing improvements in this process).

The goal was to engage the voices of racially minoritized youth to move the work toward greater racial equity. In the first round of recruitment work, no programs integrated student voice into their recruitment improvement processes. Once we added the new questions, 75% of the next round of improvers integrated youth into their recruitment work. One program leader co-designed a recruitment process with her student leadership team. She then engaged them in a storytelling unit, giving them time to carefully craft their own STEM stories. They then recruited peers in their schools, using their stories as a hook to interest others in joining their program.

We further adapted the PDSA template to ensure that our program leaders explicitly attended to the youth, adding in two questions to the planning portion of the template that prompt leaders to consider an equity rationale for testing the change:

• “Why do you think this change will be high leverage for the racially/ethnically minoritized students in YOUR program?

• Think about the goals you stated for this improvement cycle. What do you know about the current status of this goal for your racially/ethnically minoritized students? (e.g., baseline data, anecdotal knowledge, we've never assessed this before…)”.

We also added an explicit prompt in the PDSA template in the data collection design segment:

• “How will you know if this change is an improvement for your racially/ethnically minoritized students?”

These questions deliberately address and aim to focus the PDSA cycle on the racially minoritized youth in the PCSP. After we added these questions, PCSP leaders were able to articulate their intended equity goal more clearly and more tightly align that goal, the data they collected, and their results. In the next cycle after these structural changes, for example, all eight of the improvers testing a change idea to better engage program alum named, tracked, and reported Black, Latine, and Indigenous alum contacts explicitly.