- 1Rayen School of Engineering, Youngstown State University, Youngstown, OH, United States

- 2Department of Information Sciences and Technology, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, United States

Background: The term “nontraditional students” (NTS) is widely used in higher education research, but its definition varies across studies.

Objectives: This systematic literature review aims to examine how researchers define NTS in U.S.-based studies and identify potential definitional issues.

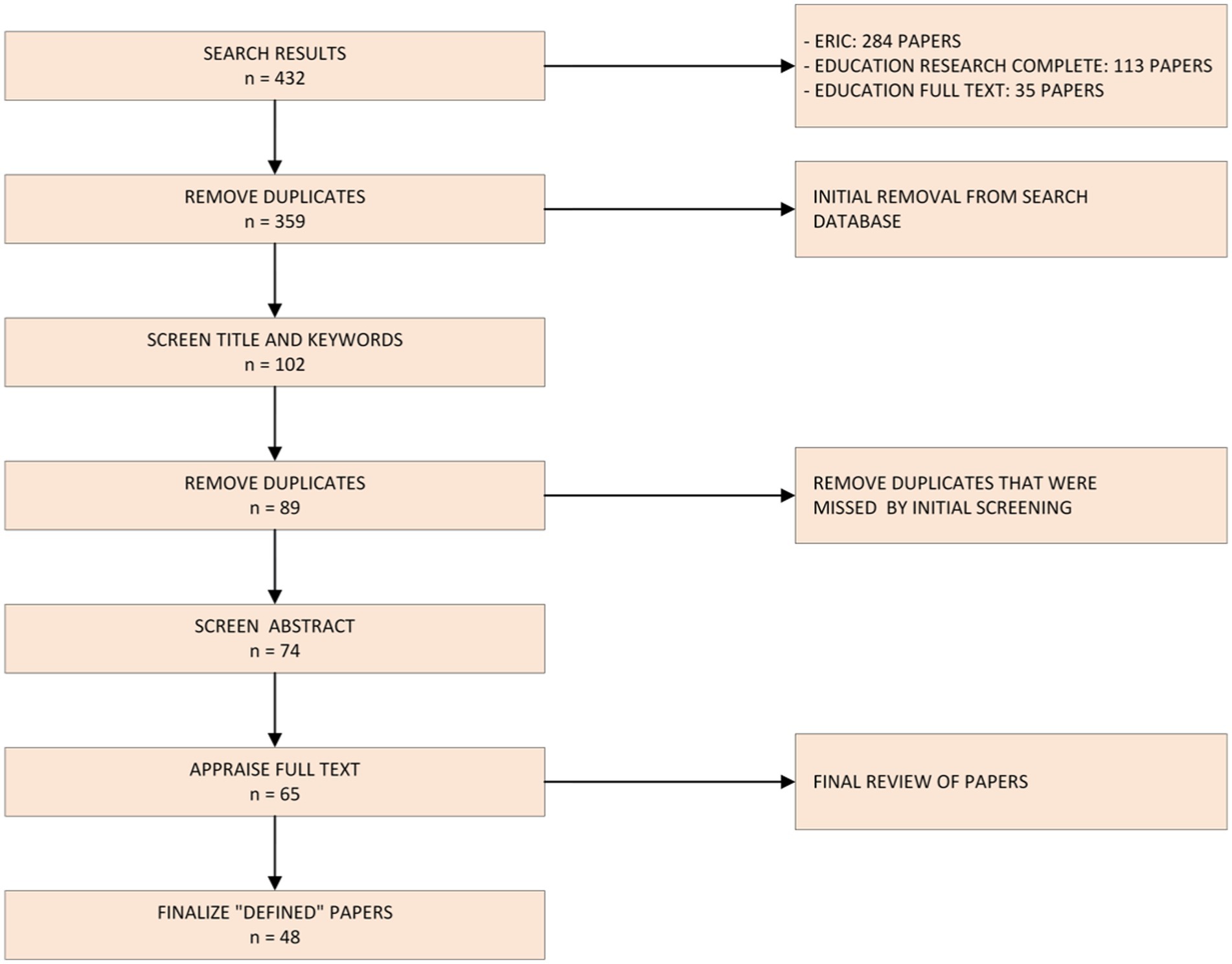

Methods: We conducted a systematic review following PRISMA guidelines, searching EBSCO databases (Education Research Complete, Education Full Text, and ERIC) for peer-reviewed articles published between 2018 and 2022. We analyzed 65 papers that met our inclusion criteria to assess the definitions used for NTS. In this systematic literature review we focus on the definitional issues related to how researchers use the term nontraditional students in US-based studies. We review 65 papers from search results containing 432 papers to understand how researchers define nontraditional students. Of the 65 papers reviewed fully, 33 papers included a specific definition of nontraditional students, 15 included an unspecified definition of nontraditional students, and 17 papers did not include a clear definition at all. Our work suggests that researchers use a clearer definition, such as from the NCES, to define nontraditional students and focus their attention on the seven categories given by NCES.

1 Introduction

Colleges and universities across the world, but especially in the U.S., are made up of an ever-increasingly diverse student population. There is great importance put on obtaining a higher education degree in society; however, with a decreasing amount of governmental funds available for higher education, students and their families must take on the burden of financing a degree. Consequently, they are looking for opportunities to receive the greatest value for their money.

Understanding the definition of nontraditional students (NTS) is crucial for several reasons. First, it directly impacts the design and implementation of educational programs and support services. A clear definition helps institutions tailor their teaching methods, course schedules, and support systems to meet the specific needs of NTS. Second, it affects policy decisions at institutional and governmental levels, influencing funding allocations and program development. Finally, a consistent definition allows for more accurate research comparisons and trend analyses, leading to evidence-based improvements in higher education accessibility and effectiveness for diverse student populations.

The challenge of defining nontraditional students extends beyond academia, impacting broader societal issues. In the United States, unclear definitions hinder policymakers’ ability to craft targeted legislation for higher education funding and support services. For instance, the Lumina Foundation (2021) reports that inconsistent categorization of nontraditional students affects state-level funding allocations and federal financial aid policies. Globally, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 2019) highlights how varying definitions across countries complicate international comparisons and knowledge sharing about effective support strategies. Moreover, employers increasingly rely on higher education institutions to upskill their workforce, but ambiguity around nontraditional student definitions creates challenges in designing appropriate continuing education programs (Hora et al., 2021). Addressing this definitional issue is thus crucial not only for educational institutions but also for economic development, workforce preparation, and international cooperation in higher education.

To support their studies, many students are taking on the costs associated with higher education by being employed full-time during an academic year and living at home to save on costs associated with residential living. Additionally, students are delaying enrollment for multiple reasons, one of which is to save for higher education expenses. Costs though are not the only factors that are changing the enrollment landscape. Students continue to deal with multiple life circumstances as they pursue their degrees—many have families and other responsibilities. Therefore, it is imperative that higher educational systems understand the backgrounds of their students and how to serve their needs best.

One way of characterizing and defining students whose experiences are different than a standard 4-year in person on-campus education is the term nontraditional students (NTS). Although coined, at least within the U.S. context, post-World War II, research on NTS continues to attract significant attention within the literature on higher education. This is not surprising given the population of students who fall under the NTS category total over 70% of students nationally (U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2015) and the many policies and support systems that are being developed to target the success of NTS. The increase in technology-driven education post-COVID has only fueled the interest in NTS as the use of online and digital learning is being seen as a mechanism to attract more NTS students and to support their teaching and learning. There is a need to understand new developments within any field to identify significant shifts or changes.

One of the first robust definitions of nontraditional students focused on three major themes of enrollment criteria, financial and family status, and high school graduation status (Horn, 1996). The seven categories within these three themes specifically associated with nontraditional students included: (1) Delayed enrollment by a year or more after high school, (2) attended part-time, (3) having dependents, (4) being a single parent, (5) working full time while enrolled, (6) being financially independent from parents, and (7) did not receive a standard high school diploma. These seven characteristics were defined primarily to bring focus to choices and behaviors of students that may increase their risk of attrition, that is, leaving or dropping out of college before completing their degree. Due to the sole focus on attrition, these categories do not include other aspects of students’ experiences that might make them nontraditional. Within the categories a scale of minimal to high was added, where one can be considered minimally nontraditional with one characteristic, moderately nontraditional with two or three characteristics, or highly nontraditional if they have four or more characteristics.

The definition advanced by Horn (1996) was one of the first ones to define nontraditional students comprehensively. Yet, it has been over two decades, and it is unclear if the definition has gained traction and is used consistently and universally or if other ways to define NTS have taken a hold. Research on NTS has been quite robust over the past few decades but reviews of NTS studies have pointed out specific concerns with prior work especially in terms of definitional issues within the field. The first review of NTS work was published in 2002 (Kim, 2002), and a decade later another paper followed up the issues raised (Chung et al., 2014). As we discuss in detail later, the Kim and Chung et al. papers, limit their focus on students within a specific context or concern; in the case of Kim, community college students in the U.S., and in Chung et al. mental health issues. Yet, they both highlight the lack of cohesiveness in definitions, their inability to advance research or practice agenda, and the need for a better understanding of definitional issues. For instance, currently, in addition to three major themes (Horn, 1996) NTS have been defined by up to 13 different subcategories (Chung et al., 2014). The concerns raised by Kim and Chung remain relevant, as evidenced by subsequent studies. For instance, Markle (2015) found persistent definitional inconsistencies in NTS research, while Zerquera et al. (2018) noted the ongoing challenges in aligning institutional practices with the diverse needs of NTS. Moreover, recent data from the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, (2015) indicate a continued high enrollment of students meeting various NTS criteria, underscoring the importance of addressing these definitional issues.

How we define a student population has important ramifications for how we then design policies and support structures for them. Consequently, if we do not define it consistently, we cannot study them or create policies and interventions to support them. The definition allows us to have a more nuanced understanding of the population and for the researcher to better define the population they are working with. Common ground is important for research that builds systematically. Therefore, definitions have to provide clarity not only in terms of who is included and why they are included, but what differentiates groups sufficiently. If there is overlap, what creates that and how is diversity important for future research and practice?

In this paper we present a systematic review of articles on NTS published during a five-year window (2018–2022) to assess what definitions, if any, are being used within the recent nontraditional student literature. We picked this window as it is the most recent complete 5 years of publications (we collected data in mid-2023). Prior work has also been covered in related reviews and this sample size gave us a significant data corpus to analyze.

We discuss our inclusion and exclusion criteria for the papers in the methods sections, but one limitation of our work is that we restrict the work to U.S. based studies given the larger number of papers from this context and because one of the most referenced definitions was from NCES and has been the marker for the field within the U.S.

2 Extant literature on nontraditional student definitions

Kim (2002) conducted one of the first reviews of the use of the term “nontraditional” within literature. Although her review was focused primarily on community colleges within the U.S., many of the concerns she raised through her reviews, and her argument for undertaking the review still hold true. She argued that given the diversity of student population within community colleges, it was important to understand the challenges students faced in a more systematic and defined manner. She contended that the way nontraditional was defined ended up being so broad that most students ended up being in that category. The problem with this, according to her, was that “the term nontraditional is too broad to be helpful in identifying specific needs (p. 74).” Nontraditional has been defined largely in terms of age, student background characteristics, and students’ at-risk behavior. The focus on at-risk is consistent with one of the goals of studying NTS which is to develop resources or programs, whether academic or non-curricular, to support them that are different than those for “traditional” students. Kim (2002) argues that “while some of these programs can be beneficial for a wide range of nontraditional students, others do not meet the specific needs of nontraditional students facing particular personal or logistical challenges (p. 78).”

Chung et al. (2014) further emphasized the concern in higher education research about the lack of consistency in the how “non-traditional students” has been defined and through their review confirm that the term includes a broad range of definitional categories even within their review of mental health related research within higher education. They found that students have been classified as nontraditional based on 13 categories that include demographic and educational background, such as age, and admissions pathways and that within each category there are even additional subcategories. In terms of research, they found that in addition to the problem of limited usefulness due to the ambiguity of the term, around 9% of articles within their data corpus did not even provide a working definition for “non-traditional students.” Furthermore, the sources of definitions were often unreferenced or partially referenced and it was unclear how the authors arrived at their method for categorizing NTS. Overall, the definitions were unclear to allow for replication of empirical work. They suggest that future research should address these problems and work toward greater clarity and consistency for the terms. They recognize the difficulty of the task in terms of reaching a consensus definition but suggest that one of the elements to start with is the purpose for defining and categorizing NTS. As an example, they say a definition of NTS that refers to characteristics which predispose university students to noncompletion might be one way of doing this.

Finally, in a recent paper that focuses on definition of NTS, Nguyen and Kramer (2023) take an empirical approach and utilize a nationally representative, publicly available, dataset to examine shifts in student population using data related to demographics, financial aid receipt, and academic experiences. They propose a new term for defining NTS—“neotraditional,” and argue this shift toward new terminology is important given the many different roles students play in their lives and their varying life circumstances. They define neotraditional students as “students who previously have been identified as “nontraditional” students; these students do not fit the historic image of the typical college student, but who now comprise the majority of postsecondary enrollment (p. 1).” They argue that this new definitional work will guide practitioners and policymakers in supporting students with multiple life roles.

Overall, work from almost two decades or more consistently shows definitional issues in the field that have consequences for student support. The issues that have been identified include a very broad characterization of NTS, use of categories and criterions that are not meaningful, and the gap between the categories and how they can be used to make policies or design support systems. Given the increase in number of students who would fall under NTS in recent years, what does the current literature tell us? Is there any clarity? Are there more useful categories being used? Basically, “How are nontraditional students defined in extant literature?” This question guided the systematic literature review we conducted.

In the rest of the paper, we first discuss our methodology for data collection and analysis and then present the findings. A list of the final papers in our sample is presented separately in Appendix.

3 Methodology

3.1 Search

We used our university’s EBSCO as our search engine. Specifically, the databases used were Education Research Complete, Education Full Text (H.W. Wilson), and ERIC. The search strings included different ways of spelling nontraditional student (non-traditional, nontraditional student, and non-traditional student). Quotation marks and the wildcard symbol (*) were used to keep the search specific. Additional limiters included full text, scholarly journals, academic journals, or journal articles written in English and published between 2018 and 2022.

The search resulted with 432 papers: 284 papers from ERIC, 113 from Education Research Complete, and 35 from Education Full Text (H.W. Wilson). The initial duplicate removal from the search left us with 359 papers; however, duplicates were still found and had to be removed in another iteration. We saved a copy of the search result, which is what we used for the first round of inclusion/exclusion.

3.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow diagram detailing our systematic review process. Of the initial 432 records identified through database searching, 73 duplicates were removed. The remaining 359 records were screened based on titles and abstracts, resulting in the exclusion of 257 records that did not meet our inclusion criteria. We assessed 102 full-text articles for eligibility, further excluding 37 articles that did not focus on NTS definitions or were not U.S.-based studies. This process resulted in 65 studies included in our qualitative synthesis.

We conducted two rounds of inclusion and exclusion. First, we read the article titles, journal names, and subjects/keywords to decide whether to include or exclude the papers based on our scope of interest which we defined as the following terms within NTS:

(1) Student support, (2) Engagement, (3) Retention, (4) Student success, (5) US-based, (6) Undergraduate students, and (7) Not-online focused programs.

After this round of analysis, we were left with 102 papers, but the sample still contained duplicates. After we removed the duplicates, we had 89 papers. All papers were downloaded, and their abstracts were analyzed for the presence of our reference to NTS in a definitional form, which formed the second round of inclusion/exclusion. We were finally left with 65 papers in total for review.

3.3 Data analysis

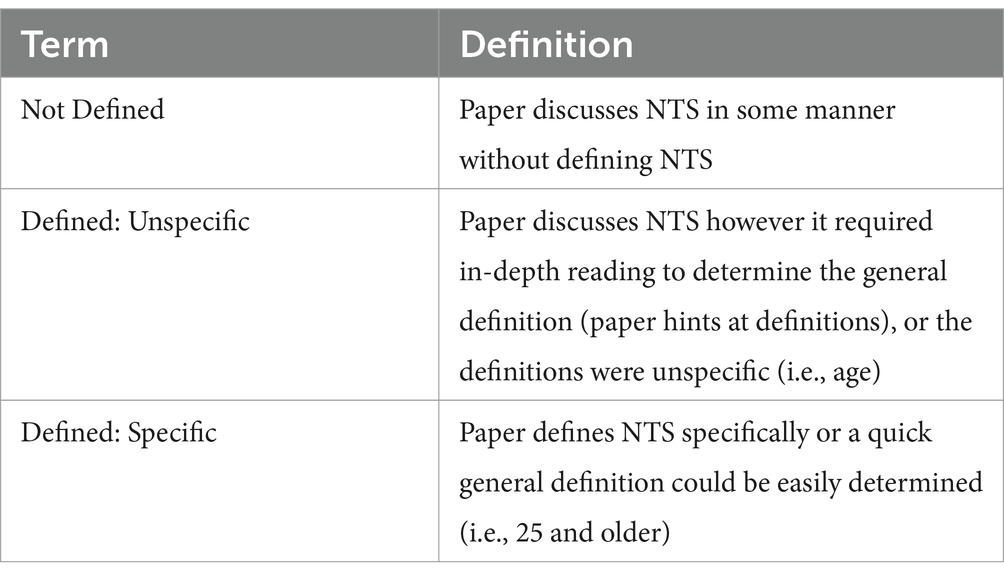

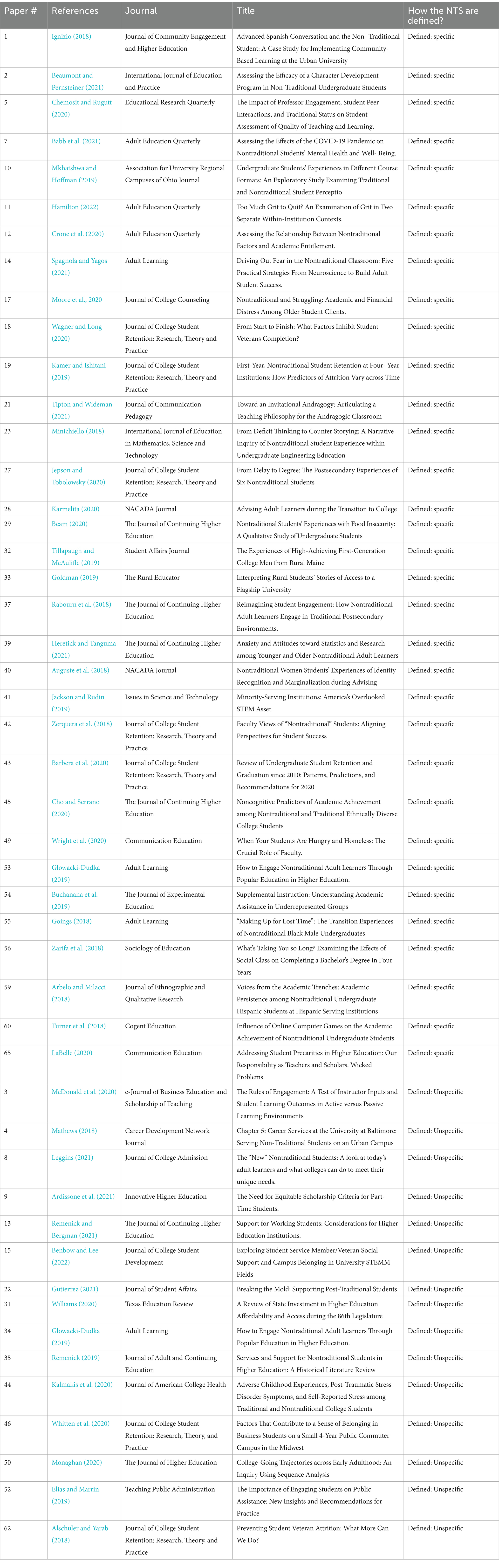

For the final set of 65 papers we collected information on the paper’s (1) Author(s), (2) Publication Year, (3) Journal, (4) Title, (5) Keywords/Subjects, (6) Main Idea, (7) NTS categorization, (8) NTS definition, (9) Research Question(s), (10) Methodology, (11) discussion of STEM, and (12) Findings. We categorized how the papers defined NTS as “Not defined,” “Defined: Unspecific,” and “Defined: Specific” (refer to table #). Some of the papers do not explicitly define NTS, but instead hint or imply certain criteria. For these cases, we classified them as “Defined: Unspecific” because we were able to gather some general definition through more reading and making our own judgment.

4 Findings

We found that 48 papers defined nontraditional students in some way. Of the 48 papers, 33 of them were classified as “Defined: Specific,” while 15 of them were classified as “Defined: Unspecific.” Additionally, 17 papers did not define nontraditional students thus were classified as “Not Defined.”

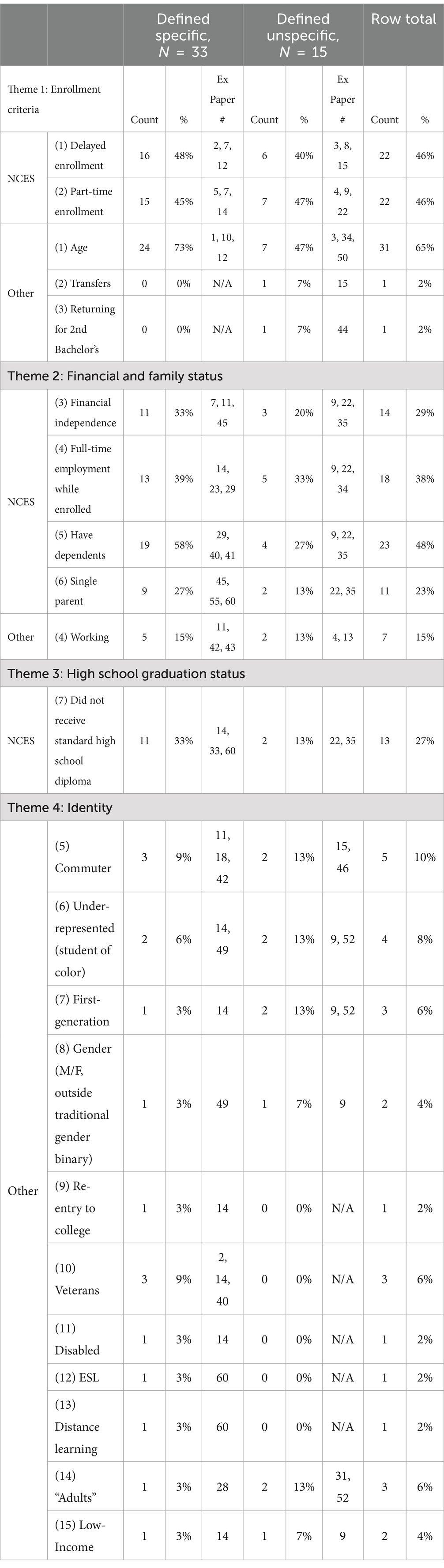

Most papers that define NTS referred to the NCES criteria in some manner. We identified four major themes in the NTS identification: (1) enrollment criteria, (2) financial and family status, (3) high school graduation status, and (4) identity.

Most papers that define NTS referred to the NCES criteria in some manner. We identified four major themes in the NTS identification: (1) enrollment criteria, (2) financial and family status, (3) high school graduation status, and (4) identity.

Theme 1: Enrollment Criteria: delayed enrollment, part-time enrollment, age, transfers, and returning for 2nd Bachelor’s. Only the first two criteria are part of the NCES criteria.

Theme 2: Financial and Family Status: financial independence, full-time employment while enrolled, have dependents, single parent, and working. The first four are part of the NCES criteria. We added “working” as a criterion because there were a significant number of papers that mention working students without specifying full-time or otherwise.

Theme 3: High School Graduation Status looks at students who did not receive standard high school diploma. This is also one of the NCES criterion.

Theme 4: Identity. This is the only theme that is not included in the NCES criteria. In this theme, we included commuter, under-represented (student of color), first-generation, gender (M/F, outside traditional gender binary), re-entry to college, veterans, disabled, ESL, distance learning, “adults,” low-income statuses.

From the NCES criteria, the top five requirements were having dependents (48% of the “defined” papers), part-time enrollment (46%), delayed enrollment (46%), full-time employment while enrolled (38%), and financial independence (29%).

Of the non-NCES criteria, age (65%), working (15%), and commuter (10%) were the top three requirements. The breakdown of the other criteria are as follows: under-represented (8%), “adults” (6%), first-generation (6%), veterans (6%), gender (4%), low-income (4%), disabled (2%), distance learning (2%), ESL (2%), re-entry to college (2%), returning for 2nd Bachelor’s (2%), transfer (2%).

Of the non-NCES criteria, age (65%), working (15%), and commuter (10%) were the top three requirements. The breakdown of the other criteria are as follows: under-represented (8%), “adults” (6%), first-generation (6%), veterans (6%), gender (4%), low-income (4%), disabled (2%), distance learning (2%), ESL (2%), re-entry to college (2%), returning for 2nd Bachelor’s (2%), transfer (2%).

The most popular criteria used to define NTS was age, with 24 papers describing specific age (i.e., above 25) and 7 papers just broadly mentioning age. Even though age is not one of the NCES criteria, it is still highly used in the literature to describe NTS.

The most popular criteria used to define NTS was age, with 24 papers describing specific age (i.e., above 25) and 7 papers just broadly mentioning age. Even though age is not one of the NCES criteria, it is still highly used in the literature to describe NTS.

The second most referred to criteria is the 7 NCES NTS criteria. However, not all the papers that use the NCES criteria will use or mention all 7 criteria. Some papers may mix their definitions with other non-NCES identity criteria (i.e., commuter, under-represented, first-generation, etc.)

Overall, the literature defines NTS in many different ways, but primarily has an age and some NCES criteria components.

Overall, the literature defines NTS in many different ways, but primarily has an age and some NCES criteria components.

5 Discussion

Overall, there are many opportunities found to develop a more comprehensive way moving forward to discuss and conduct research on nontraditional students. First, “Age” was used most frequently to define a nontraditional student, even though it is too broad a category. Second, there are still a wide range of definitions used to define nontraditional students even with calls to be more specific. And third, the seven NCES categories give a succinct definition to use if you want to talk about nontraditional students broadly, however there are ways to focus in on the categories more purposefully depending on the rationale.

5.1 Age as a defining term for NTS

Overall, we found that Age is still one of the criteria that is used the most to define NTS. Although the relationship between Age and being a student is strong, it is increasingly too broad a category to be useful for making decisions about NTS support. 65% of the papers use Age as a defining characteristic of a nontraditional student either defined specific or unspecific. Examples of Defined: Specific for Age, Goldman (2019) define Age as “25 years or older” and Rabourn et al. (2018) use Age as “students over the age of 24 or over the age of 21 at first entry.” Whereas Defined: Unspecific examples include (Paper 31) defines Age as “adult students.”

In a study of faculty about NTS, Jinkens (2009) found that composite opinion of 30 faculty indicated that age may not properly identify whether students are traditional or nontraditional. Furthermore, faculty said that a life changing event is more of a determinant of how students approach their education. Additionally, Tilley (2014) conducted a study of students over 25 versus under 25 on multiple factors of stress and academic self-concept and determined that the age criterion is not enough to define a nontraditional student as there were no differences between groups.

Thus, using Age in any manner takes away the details underlying what their specific circumstances have to do with their nontraditional status. Age should be thought of as an indicator of other life happenstances and further delineation of those into more specific categories. It is not a useful criterion on the surface to use age solely, or in conjunction with other criteria, to define a nontraditional student.

5.2 Wide breadth of definitions used to define NTS

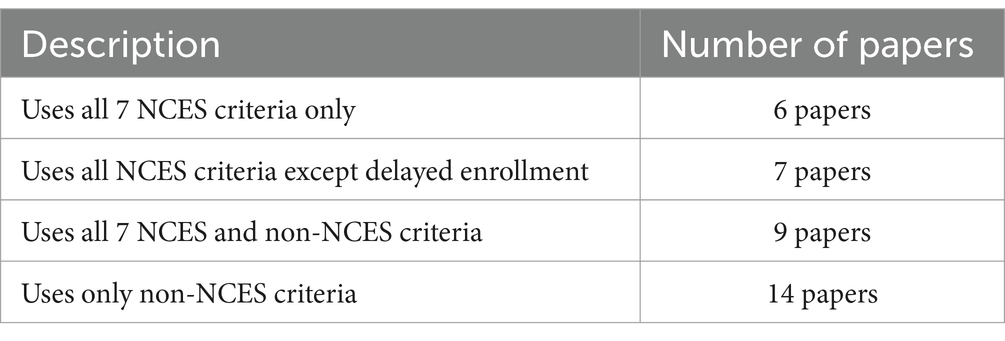

From our systematic review, we note the stark inconsistency with the way the literature defines nontraditional students. Out of the 48 “defined” papers, there were 6 papers that clearly defined NTS using all 7 NCES criteria. There were 7 papers that used all NCES criteria together with non-NCES criteria. There were 14 papers that used only non-NCES criteria. The rest of the papers use some mix of the two, NCES and non-NCES.

The lack of a consistent use of a definition for nontraditional students underscores a few areas of concern. First, the continuing inconsistency in how NTS is defined. This problem around lack of a common and consistent definition for NTS has been discussed at least since 2002 when Kim (2002) brought attention to it and the concern was raised again almost a decade later in 2014 (Chung et al., 2014). In this review, we found the same troubling pattern. Second, and even more problematic, is the concern with the lack of any definition of NTS within research studies. Although there is an acceptable and useful definition, at least to some degree, available in literature (NCES), researchers do not use it.

This highlights either a lack of rigor in studies that are conducted and/or the ineffectiveness of the current definitions for research studies that scholars want to conduct. It is unclear from our review which of these might be a factor but so long as these inconsistencies continue, the overall research terrain in this field will remain weak largely due to lack of any replication or the ability to build on prior work. Consequently, it is imperative that either a standard definition be developed and used, or well-defined elements within the educational experiences of NTS become focal point of research, so that the population is not defined by broad categories.

5.3 Future directions—some alternate and more ecological valid conceptions of NTS

Given the lack of consistency in the use of NTS definitions and increasing critique around the usefulness of the term, we argue that there is a need to think differently about how we define NTS. We propose that there needs to be a better alignment between student needs and policies and support systems and for this we need definitions that take a more purpose-driven approach as outlined by Nguyen and Kramer (2023). Although the term proposed by them, neotraditional, might or might not be needed in the field, the suggestion to align definition of NTS to the purpose it serves for students is useful. We additionally suggest that like the use of the term “value-based healthcare,” higher education itself needs to think more about the value it aims to provide and how student experiences are linked to that. Similar arguments have been made by scholars studying online delivery from a “value-based delivery of education” perspective (Gilfoil and Focht, 2015). The nuances of how a student is NTS shape the value they can derive from their education, and it is important to capture that. In a value-based definition context, the usefulness can come from aligning family or work with flexible delivery of content, for instance. There are other conceptions in the literature such as “strengths-based” (Pang et al., 2018) and “alignment-based” (Zerquera et al., 2018) that are also possible ways to define NTS. Aligning what students want—a degree for job promotion, to their support is essential. Overall, we are arguing for a more ecologically valid (Cole et al., 1997) definition of NTS that serves the students. An ecologically valid definition in this context will consider the contexts in which students study and learn, the resources they use and need, and the responsibilities they must fulfill in the different roles they play in their lives.

The evolving landscape of higher education necessitates a reevaluation of how we define and support nontraditional students (NTS). Recent studies have highlighted the multifaceted nature of student experiences, encompassing factors such as work-life balance, financial constraints, and diverse educational pathways (Chung et al., 2017; Markle, 2015). We propose that any new definition of NTS should incorporate these nuanced dimensions. Concrete policy recommendations to address the needs of NTS in the current era include:

1. Implementing a comprehensive national assessment of student needs, going beyond demographics to include life circumstances, educational goals, and support requirements (Zerquera et al., 2018).

2. Expanding federal and state financial aid programs to cover indirect educational costs, such as childcare and transportation, which disproportionately affect NTS (Goldrick-Rab et al., 2020).

3. Mandating flexibility in academic policies, including more lenient leave of absence and re-entry procedures, to accommodate the complex lives of NTS (van Rhijn et al., 2016).

4. Developing a national database that tracks NTS experiences and outcomes, using a standardized definition to inform evidence-based policymaking (Cruse et al., 2019).

5. Incentivizing institutions to provide comprehensive support services, including mental health resources, career counseling, and academic advising tailored to NTS needs (Cotton et al., 2017).

These policy changes would not only better serve the needs of NTS but also modernize the higher education system to reflect the diverse realities of contemporary student populations.

The findings of this systematic literature review have several practical implications. For educational institutions, a clearer definition of NTS can guide the development of targeted support services, flexible learning options, and inclusive policies. Policymakers can use this information to refine financial aid programs and educational legislation to better serve the diverse NTS population. Researchers can benefit from a more standardized definition, enabling more reliable comparisons across studies and facilitating meta-analyses. Finally, students themselves may find it easier to identify and access appropriate resources and programs when institutions use consistent NTS definitions.

6 Conclusion

Our systematic literature review of 65 U.S.-based studies published between 2018 and 2022 revealed significant inconsistencies in the definition and use of the term “nontraditional students” (NTS). The analysis uncovered that only half of the reviewed papers (33 out of 65) included a specific definition of NTS, while nearly a quarter used unspecified definitions, and the remaining quarter provided no clear definition at all. This lack of definitional clarity undermines the ability to compare studies, build on prior work, and develop effective policies for NTS support.

Notably, age emerged as the most prevalent factor in defining NTS, appearing in 65% of the papers that defined the term, despite not being part of the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) criteria. This finding highlights a disconnect between research practices and established guidelines. Furthermore, our review found varied use of the NCES criteria, with only a small fraction of papers (6 out of 65) employing all seven NCES criteria. Many researchers opted for a combination of NCES and non-NCES criteria, further contributing to the definitional inconsistency in the field.

The review also identified the emergence of new categories used to define NTS, such as commuter status, under-represented status, and first-generation status. This evolution in conceptualizing NTS reflects the changing landscape of higher education but also adds to the complexity of achieving a standardized definition.

A critical finding from our review is the scarcity of purpose-driven definitions. Few studies aligned their definition of NTS with the specific objectives of their research or the needs of the student population being studied. This lack of alignment between definition and research purpose potentially limits the practical applicability of findings and the development of targeted support strategies.

These results echo concerns raised in previous reviews by Kim (2002) and Chung et al. (2014), indicating that the issue of definitional inconsistency in NTS research persists. This ongoing challenge hinders the field’s ability to advance cohesively and impacts the effectiveness of policies and support systems designed for NTS.

Based on these findings, we recommend that future research in this field adopt a more consistent use of the NCES criteria as a baseline definition for NTS in U.S.-based studies. Researchers should be encouraged to explicitly state and justify their definition of NTS in relation to their study’s objectives. Additionally, there is a need to develop more nuanced, purpose-driven definitions that consider the evolving nature of higher education and student needs.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. Our review focused exclusively on U.S.-based research, which limits the generalizability of our findings to other national contexts. Additionally, the five-year timeframe (2018–2022) we selected, while providing recent data, may not capture longer-term trends in the field. Our search strategy, although comprehensive, may have inadvertently excluded relevant studies that did not use our specific search terms. Furthermore, our analysis was primarily qualitative, and a quantitative meta-analysis could provide additional insights into the patterns of NTS definitions across studies.

Looking ahead, the field would benefit from establishing a national framework for tracking and supporting NTS. Such a framework should allow for both standardization and flexibility in defining this diverse population. Future research should focus on developing and validating a more comprehensive, flexible framework for defining NTS that can accommodate the diverse realities of contemporary student populations while still allowing for meaningful comparisons across studies. By addressing these definitional issues, researchers and policymakers can more effectively support the growing and diverse population of nontraditional students in higher education.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AJ: Formal analysis, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AC: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This material was based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under grant number 2044347 within the IUSE program. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alschuler, M., and Yarab, J. (2018). Preventing student veteran attrition: What more can we do? J. Coll. Stud. Retent.: Res. Theory Pract. 20, 47–66.

Arbelo, F., and Milacci, F. (2018). Voices from the academic trenches: Academic persistence among nontraditional undergraduate Hispanic students at Hispanic serving institutions. J. Ethnogr. Qual. Res. 12, 219–232.

Ardissone, A. N., Galindo, S., Wysocki, A. F., Triplett, E. W., and Drew, J. C. (2021). The need for equitable scholarship criteria for part-time students. Innov. High. Educ. 46, 1–19.

Auguste, E., Packard, B. W.-L., and Keep, A. (2018). Nontraditional women students' experiences of identity recognition and marginalization during advising. NACADA J. 38, 45–60. doi: 10.12930/NACADA-17-046

Babb, S. J., Rufino, K. A., and Johnson, R. M. (2021). Assessing the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on nontraditional students' mental health and well-being. Adult Educ. Q. 71, 279–297. doi: 10.1177/07417136211027508

Barbera, S. A., Berkshire, S. D., Boronat, C. B., and Kennedy, M. H. (2020). Review of undergraduate student retention and graduation since 2010: patterns, predictions, and recommendations for 2020. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. 22, 227–250. doi: 10.1177/1521025117738233

Beam, M. (2020). Nontraditional students' experiences with food insecurity: a qualitative study of undergraduate students. J. Contin. High. Educ. 68, 141–163. doi: 10.1080/07377363.2020.1792254

Beaumont, S. L., and Pernsteiner, C. (2021). Assessing the efficacy of a character development program in non-traditional undergraduate students. Int. J. Educ. Pract. 9, 588–601. doi: 10.18488/journal.61.2021.93.588.601

Benbow, R. J., and Lee, Y. (2022). Exploring student service member/veteran social support and campus belonging in university STEMM fields. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 63, 84–100.

Buchanana, E. M., Valentineb, K. D., and Frizell, M. L. (2019). Supplemental instruction: understanding academic assistance in underrepresented groups. J. Exp. Educ. 87, 288–298. doi: 10.1080/00220973.2017.1421517

Chemosit, C. C., and Rugutt, J. K. (2020). The impact of professor engagement, student peer interactions, and traditional status on student assessment of quality of teaching and learning. Educ. Res. Q. 43, 3–24.

Cho, K. W., and Serrano, D. M. (2020). Noncognitive predictors of academic achievement among nontraditional and traditional ethnically diverse college students. J. Contin. High. Educ. 68, 190–206. doi: 10.1080/07377363.2020.1776557

Chung, E., Turnbull, D., and Chur-Hansen, A. (2014). Who are non-traditional students? A systematic review of published definitions in research on mental health of tertiary students. Educ. Res. Rev. 9, 1224–1238. doi: 10.5897/ERR2014.1944

Cole, M., Hood, L., and McDermott, R. P. (1997). Concepts of ecological validity: Their differing implications for comparative cognitive research. In Mind, culture, and activity: Seminal papers from the Laboratory of Comparative Human Cognition. eds. M. Cole, Y. Engeström, and O. A. Vasquez (Cambridge University Press), 49–56.

Cotton, D. R., Nash, T., and Kneale, P. (2017). Supporting the retention of non-traditional students in higher education using a resilience framework. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 16, 62–79. doi: 10.1177/1474904116652629

Crone, T. S., Babb, S., and Torres, F. (2020). Assessing the relationship between nontraditional factors and academic entitlement. Adult Educ. Q. 70, 277–294. doi: 10.1177/0741713620905270

Cruse, L. R., Holtzman, T., Gault, B., Croom, D., and Polk, P. (2019). Parents in college by the numbers. Washington, DC: Institute for Women's Policy Research.

Elias, N. M., and Marrin, M. (2019). The importance of engaging students on public assistance: New insights and recommendations for practice. Teach. Public Adm. 37, 200–216.

Gilfoil, D. M., and Focht, J. W. (2015). Value-based delivery of education: MOOCs as messengers. Am. J. Bus. Educ. 8, 223–238. doi: 10.19030/ajbe.v8i3.9284

Glowacki-Dudka, M. (2019). How to engage nontraditional adult learners through popular education in higher education. Adult Learn. 30, 84–86. doi: 10.1177/1045159519833998

Goings, R. B. (2018). "Making up for lost time": the transition experiences of nontraditional black male undergraduates. Adult Learn. 28, 121–124. doi: 10.1177/1045159515595045

Goldman, A. (2019). Interpreting rural students' stories of access to a flagship university. Rural Educ. 40, 16–28. doi: 10.35608/ruraled.v40i1.530

Goldrick-Rab, S., Coca, V., Kienzl, G., Welton, C. R., Dahl, S., and Magnelia, S. (2020). #RealCollege during the pandemic: new evidence on basic needs insecurity and student well-being : Rebuilding the Launchpad: Serving Students During Covid Resource Library.

Gutierrez, C. D. (2021). Breaking the mold: Supporting post-traditional students. J. Stud. Aff. 30, 25–35.

Hamilton, W. (2022). Too much grit to quit? An examination of grit in two separate within-institution contexts. Adult Educ. Q. 72, 179–196. doi: 10.1177/07417136211034512

Heretick, D. M. L., and Tanguma, J. (2021). Anxiety and attitudes toward statistics and research among younger and older nontraditional adult learners. J. Contin. High. Educ. 69, 87–99. doi: 10.1080/07377363.2020.1784690

Hora, M. T., Smolarek, B. B., Martin, K. N., and Scrivener, L. (2021). Exploring the alignment of occupational skills and competencies with the needs of employers: a focus on "new-traditional" undergraduate students. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 73, 377–399.

Horn, L. (1996). Nontraditional undergraduates, trends in enrollment from 1986 to 1992 and persistence and attainment among 1989–90 beginning postsecondary students (NCES 97–578) : U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

Ignizio, G. S. (2018). Advanced Spanish conversation and the non-traditional student: a case study for implementing community-based learning at the urban university. J. Commun. Engag. High. Educ. 10, 3–14.

Jackson, L. M., and Rudin, T. (2019). Minority-serving institutions: America's overlooked STEM asset. Issues Sci. Technol. 35, 58–62.

Jepson, J. A., and Tobolowsky, B. F. (2020). From delay to degree: the postsecondary experiences of six nontraditional students. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. 22, 27–48. doi: 10.1177/1521025117724347

Kalmakis, K. A., Chiodo, L. M., Kent, N., and Meyer, J. S. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences, post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, and self-reported stress among traditional and nontraditional college students. J. Am. Coll. Health. 68, 411–418.

Kamer, J. A., and Ishitani, T. T. (2019). First-year, nontraditional student retention at four-year institutions: how predictors of attrition vary across time. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. 21, 401–414. doi: 10.1177/1521025119858732

Karmelita, C. (2020). Advising adult learners during the transition to college. NACADA J. 40, 64–79. doi: 10.12930/NACADA-18-30

Kim, K. A. (2002). ERIC review: exploring the meaning of “nontraditional" at the community college. Community Coll. Rev. 30, 74–89. doi: 10.1177/009155210203000104

LaBelle, S. (2020). Addressing student precarities in higher education: our responsibility as teachers and scholars. Commun. Educ. 69, 267–276. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2020.1724311

Leggins, S. (2021). The ‘new’ nontraditional students: A look at today’s adult learners and what colleges can do to meet their unique needs. J. Coll. Admiss. 250, 34–39.

Markle, G. (2015). Factors influencing persistence among nontraditional university students. Adult Educ. Q. 65, 267–285. doi: 10.1177/0741713615583085

Mathews, L. (2018). Career services at the University at Baltimore: Serving non-traditional students on an urban campus. Career Dev. Network J. 34, 45–52.

McDonald, D., Holmes, Y., and Prater, T. (2020). The rules of engagement: A test of instructor inputs and student learning outcomes in active versus passive learning environments. e-Journal of Business Education & Scholarship of Teaching, 14, 111–126.

Minichiello, A. (2018). From deficit thinking to counter storying: a narrative inquiry of nontraditional student experience within undergraduate engineering education. Int. J. Educ. Math. Sci. Technol. 6, 266–284. doi: 10.18404/ijemst.428188

Mkhatshwa, T. P., and Hoffman, T. K. (2019). Undergraduate students' experiences in different course formats: an exploratory study examining traditional and nontraditional student perceptions. Assoc. Univ. Reg. Camp. Ohio J. 25, 89–116.

Monaghan, D. B. (2020). College-going trajectories across early adulthood: An inquiry using sequence analysis. J. High. Educ. 91, 402–432.

Moore, E. A., Winterrowd, E., Petrouske, A., Priniski, S. J., and Achter, J. (2020). Nontraditional and struggling: academic and financial distress among older student clients. J. Coll. Couns. 23, 221–233. doi: 10.1002/jocc.12167

Nguyen, T. D., and Kramer, J. W. (2023). Constructing a clear definition of neotraditional students and illuminating their financial aid, academic, and non-academic experiences and outcomes in the 21st century. J. Stud. Financ. Aid 52:2. doi: 10.55504/0884-9153.1766

Pang, B., Garrett, R., Wrench, A., and Perrett, J. (2018). Forging strengths-based education with non-traditional students in higher education. Curric. Stud. Health Phys. Educ. 9, 174–188. doi: 10.1080/25742981.2018.1444930

Rabourn, K. E., BrckaLorenz, A., and Shoup, R. (2018). Reimagining student engagement: how nontraditional adult learners engage in traditional postsecondary environments. J. Contin. High. Educ. 66, 22–33. doi: 10.1080/07377363.2018.1415635

Remenick, L. (2019). Services and support for nontraditional students in higher education: A historical literature review. J. Adult Contin. Educ. 25, 113–130.

Remenick, L., and Bergman, M. (2021). Support for working students: Considerations for higher education institutions. J. Contin. High. Educ. 69, 49–61.

Spagnola, R., and Yagos, T. (2021). Driving out fear in the nontraditional classroom: five practical strategies from neuroscience to build adult student success. Adult Learn. 32, 89–95. doi: 10.1177/1045159520966054

Tillapaugh, D., and McAuliffe, K. (2019). The experiences of high-achieving first-generation college men from rural Maine. Stud. Affairs J. 37, 83–96. doi: 10.1353/csj.2019.0006

Tilley, B. P. (2014). What makes a student non-traditional? A comparison of students over and under age 25 in online, accelerated psychology courses. Psychol. Learn. Teach. 13, 95–106. doi: 10.2304/plat.2014.13.2.95

Tipton, W., and Wideman, S. (2021). Toward an invitational andragogy: articulating a teaching philosophy for the andragogic classroom. J. Commun. Pedag. 5, 156–163. doi: 10.31446/JCP.2021.2.16

Turner, P. E., Johnston, E., Kebritchi, M., Evans, S., and Heflich, D. A. (2018). Influence of online computer games on the academic achievement of nontraditional undergraduate students. Cogent Educ. 5:1437671. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2018.1437671

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2015). Demographic and enrollment characteristics of nontraditional undergraduates: 2011–12. Available at: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2015/2015025.pdf (accessed October 1, 2023).

van Rhijn, T. M., Lero, D. S., Bridge, K., and Fritz, V. A. (2016). Unmet needs: challenges to success from the perspectives of mature university students. Can. J. Stud. Adult Educ. 28, 29–47. doi: 10.56105/cjsae.v28i1.4704

Wagner, B. A., and Long, R. N. (2020). From start to finish: what factors inhibit student veterans completion? J. Coll. Stud. Retent. 22, 118–139. doi: 10.1177/1521025120935118

Whitten, D., James, A., and Roberts, C. (2020). Factors that contribute to a sense of belonging in business students on a small 4-year public commuter campus in the Midwest. J. Coll. Stud. Retent.: Res. Theory Pract. 22, 118–139.

Williams, A. (2020). A review of state investment in higher education affordability and access during the 86th Legislature. Tex. Educ. Rev. 8, 128–141.

Wright, S., Haskett, M. E., and Anderson, J. (2020). When your students are hungry and homeless: the crucial role of faculty. Commun. Educ. 69, 260–267. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2020.1724310

Zarifa, D., Kim, J., Seward, B., and Walters, D. (2018). What's taking you so long? Examining the effects of social class on completing a bachelor's degree in four years. Sociol. Educ. 91, 290–322. doi: 10.1177/0038040718802258

Zerquera, D. D., Ziskin, M., and Torres, V. (2018). Faculty views of “nontraditional” students: aligning perspectives for student success. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. 20, 29–46. doi: 10.1177/1521025116645109

Appendix

Keywords: nontraditional students, systematic literature review, US-based, definitional issues, research

Citation: Brozina C, Johri A and Chew A (2024) A systematic review of research on nontraditional students reveals inconsistent definitions and a need for clarity: focus on U.S. based studies. Front. Educ. 9:1434494. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1434494

Edited by:

Karan Singh Rana, Aston University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Hengki Wijaya, Sekolah Tinggi Filsafat Theologia Jaffray, IndonesiaMohammad Iqbal, University of Brawijaya, Indonesia

Copyright © 2024 Brozina, Johri and Chew. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cory Brozina, c2Nicm96aW5hQHlzdS5lZHU=

Cory Brozina

Cory Brozina Aditya Johri

Aditya Johri Alanis Chew1

Alanis Chew1