Abstract

In this conceptual piece, we explore the emerging definition of equity-centered improvement in education. We describe how the Center for Educational Improvement and Innovation, a partnership center at the University of Maryland College Park, both conceptualizes and operationalizes equity across three initiatives: (1) a district-embedded networked improvement community focused on math achievement and social/emotional learning; (2) a school improvement leadership academy which offers evidence-based professional learning to principals and assistant principals serving in high need schools in Maryland and New Jersey; and (3) a racial and social justice collaborative utilizing a research-practice partnership to address issues of equity within Maryland school districts. We present this article as a type of “reflective practice” as we consider how equity-focused continuous improvement plays out across these three initiatives. In focusing on how each initiative embeds and develops equity-focused improvement practices, we investigate the connection between our shared understanding of equity and its implementation.

Introduction

After a series of brutal injustices, such as the murder of Tamir Rice, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd and other Black men and women, the word “equity” moved from the sidelines onto center stage. Business, nonprofit, and government leaders raced to determine how their organizations would center equity in their work and the importance of equity as a guiding ethos. K-12 and higher education leaders also elevated the role of equity in curriculum, pedagogy, leadership development, and research (Sawchuk, 2021). At the University of Maryland, College Park, the Center for Educational Innovation & Implementation (CEii), the strategic decision to center all its initiatives around equity occurred long before equity centered work became more common and, in many contexts, more controversial. However, we began a practice of reflecting more carefully on the implementation of equity across our initiatives after the “health and racial pandemics” put a spotlight on injustices in schools nationally (Ladson-Billings, 2021).

In this article, we reflect on how our organization has attempted to root equity in the organization’s core beliefs and actions. We highlight three different CEii initiatives in what follows, specifically examining the tension between conceptualizing equity in theory and implementing equity in practice. We posit that there is an organizational difference between claiming equity and making equity a central component of practice. Taken together, these three initiatives offer insights for translating aspirations of equity into actualized practices.

Background

The Center of Educational Innovation and Improvement (CEii) is a partnership, technical assistance, and research center within the University of Maryland, College Park’s College of Education. Founded in 2017, CEii’s mission is to promote and advance equity, continuous improvement, and effective leadership. CEii accomplishes this mission by developing collaborative research-practice partnerships among university faculty, school district leaders, state departments of education, and national education organizations. Through scholarship, teaching, and practical implementation with school district partners, CEii leverages the philosophies and tools of improvement science as the core strategic approach to developing leadership and advancing educational equity. CEii’s primary work fosters collaborative partnerships to promote advancements in professional education, develop innovative solutions for current thorny problems of practice in education, and support collaborative research in public schools.

Description of authors

For this article, eight CEii team members served as authors to reflect on the ways the authorship team defines and implements equity based practices, policies, and pedagogies in our partnership work. The authors include the Director and Associate Director of CEii, the directors of the three projects described and two post-doctoral fellows. One of the authors works in a shared role with both the CEii and Prince George’s County Public schools. While the article is written primarily by university members, the projects presented were designed, implemented, and evaluated in close collaboration with school district partners. The three initiatives described in this article each were written by a subset of the authors and in collaboration with the broader CEii team and practitioners from partner school districts. Although the term “we” throughout the manuscript refers to different subsets of our team leading each initiative, it also refers to our shared vision and collective responsibility as the CEii for those initiatives.

Our evolving interpretation of and engagement with equity

At CEii, equity is embedded in our improvement journey and program development. As CEii has grown and expanded, we have embraced many of the emerging definitions of equity in the education and improvement communities. We have not found it particularly useful to quibble over the exact definition of equity or over which definition is “right” or “wrong.” We embrace a more common definition of equity as “giving every student what they need,” and we also recognize that true equity is only achieved when no student’s success can be predicted based on their race, class, gender, or other characteristics (National Equity Project, n.d.). We believe that equity work involves an active, conscious, and committed fight against the injustices that directly result from intentional, historic, and ongoing systemic discrimination and oppression (Gillborn, 2005; Eddy-Spicer and Gomez, 2022). Many structures, policies, and practices intentionally designed for inequity are still operating in educational systems (Ladson-Billings, 2006). Dismantling and restructuring these systems is necessary to create just educational systems. Yet, while transformational systemic change is the ultimate goal, we also embrace the “everyday” work that makes educational systems and practices more equitable, even within flawed systems. For us, it is the broad scale system change and the daily work to increase equitable practices that forms the crucial intersection of equity and improvement.

As the CEii team continues to work toward defining the union of equity and improvement, we draw on the scholarship of Hinnant-Crawford et al. (2023) and Farrell et al. (2023). Hinnant-Crawford and colleagues caution us that, “equity is the current buzzword in education” (Hinnant-Crawford et al., 2023, p. 105). They urge practitioners and researchers to employ “discernement” (p. 106) when using continuous improvement methodologies in pursuit of educational equity, arguing that, at times, improvement work has focused on outcomes other than “justice” and instead perpetuated systems of inequality. They reject efficiency as the metric for continuous improvement work. Taking Hinnant-Crawford et al.’s words of warning seriously, The CEii team reflects upon ensuring that we do not simply claim equity is central to the mission but enacts it in practice (Anderson et al., 2024). As such, CEii’s aim is to invoke continuous improvement efforts centered on and measured against efforts to “serve the goal of justice” (Hinnant-Crawford et al., 2023, p. 106).

CEii operationalizes our definition of equity in service of justice by adopting Farrell et al.’s (2023) idea of “equity-in-mission” specifically via the lens of “power, justice, and anti-racism.” Farrell et al. (2023) defines the “power, justice and anti-racism” lens as adopting “…critical perspective on contemporary systems, seeking not just to improve but also to transform and abolish unjust policies and practices” (Farrell et al., 2023, p. 210). CEii embraces both the aim of just outcomes via transforming unjust systems and structures and the aim of improving outcomes via working within existing systems and structures. We couple our understanding of “equity as serving the goal of justice” with our understanding of “equity-in-mission.” We also consider ourselves to be, in the words of Hinnant-Crawford et al. (2023), “radical pragmatists,” which we consider to be working to improve systems to become more equitable every day even as we may wish to “transform and abolish” many of them. CEii sees the intersection of equity and improvement as essential to our work and to the work of public education.

Improvement is only relevant and impactful when it is centered in equity, be it the transformative work of systems change or the pragmatic work of small scale improvement. We see our focus on working squarely in service of just outcomes but recognize that the work requires us to operate within and through unjust systems. We also meet our partners where they are in their equity journey to support their development towards adopting the mantle of employing equity in service in just outcomes. CEii strives to serve as a committed and trusted partner in community with those closest to the wickedest problems and believes those closest to the problem must be architects of the solutions; we embrace the stance that improvers must be constantly reviewing and investigating “who is involved in the improvement” (Hinnant-Crawford et al., 2023, p. 114).

This article offers three vignettes of three CEii initiatives that, while very different in scope and focus, tell a common story about our commitment to equity and improvement in service to just outcomes. They also illustrate the ways in which we continue to wrestle with the challenge of defining and operationalizing equity in practice.

Methods

Engaging in reflective practice

We present this article as “a product of reflective practice rather than of formal research” (Metz, 2001, p. 12). By focusing on how each of the CEii initiatives embeds and develops equity-centered improvement practices, we take on the role of reflective practitioners to investigate the connection between the definition, measurement of equity, and implementation. At the same time, we heed the caution of Ishimaru and Galloway (2021) that “even explicit and systems-focused” discussions alone are not enough, and that reflection must be coupled with action (Ishimaru and Galloway, 2021). To this end, we write as a collective of scholarly practitioners, both doing the work and reflecting upon it.

Much of CEii’s work lies at the intersection of higher education and public school districts, which requires boundary-spanning work. As such, we came together as a team of boundary spanners—each working on different CEii initiatives that cross university and local school districts—to craft our “reflective practice” (Metz, 2001). Specifically, we worked on this product in three phases: The first was a whole team exercise ceremoniously led by CEii’s director. In a full team in-person meeting, we discussed the different ways we defined equity in our improvement work. We identified the difficulty of the task of agreeing on one definition of equity and the differences in our personal definitions of equity. There was also heated discussion on the necessity of a definition of equity and the degree to which such a definition would benefit our improvement work. From the whole group exercise, the team decided to break into project specific teams to further describe how the CEii definition of equity takes on a slightly different shape in each project. The second phase was a project specific exercise in which members drafted the ways equity was operationalized in the facilitation and development of materials. The third and final phase was taking our discussion notes and project paragraphs to form this article. Through the process of writing, questioning, and revising this article we arrived at a flexible definition of equity. It was through this difficult and nonlinear process defining equity, a term we invoke often, that we grew. Put differently, the act of struggling—and, at times, disagreeing—on the degree to which our practices enact our beliefs enabled us to further refine our collective understanding.

Findings

We offer three vignettes that exemplify how the CEii operationalizes equity-centered improvement work. Specifically, we illustrate how three different CEii initiatives operationalize the core tenets of our shared definition: equity as serving the goal of justice (rather than efficiency) and equity-in-mission.

Networked improvement communities

With funding from a federal ESSER grant, the University of Maryland, College Park (UMD) and Prince George’s County Public Schools (PGCPS) leveraged an ongoing university-district partnership to target learning recovery strategies related to the Covid-19 school closures. In fall of 2021, CEii and PGCPS collaboratively launched the School Improvement Network Community (SINC), responding to district wide concerns regarding mathematics achievement about the low achievement levels in mathematics. This networked improvement community (NIC) was composed of 15 teams of school-based practitioners focused on mathematics instruction. The NIC was aimed at improving outcomes for students across the district in response to the gaps in academic performance during the pandemic, which illustrates one aspect of equity-in-action theorized by Farrell et al. (2023). A Networked Improvement Community is designed as a structured forum for individual classroom, school, and/or district-level innovation to be shared and accelerated across a broader network. Such networks are composed of a varied set of stakeholders, working in tandem to solve shared challenges or equity gaps referred to as “problems of practice” (Bryk et al., 2011).

To bring the network’s problem of practice into focus, a collaborative group of district leaders and university faculty engaged in a series of data reviews, which included district benchmark data, state student assessment data, a sampling of school improvement plans, and the district strategic plan. Participants identified trends in the data with the intention of identifying where the district’s commitment to academic equity and excellence for all students was not being met.

A big part of this early stage of network initiation revolved around relationship and trust building across the partner institutions and between the varied departments in the networks. We learned in this initial stage of the network that we needed to start slowly to establish our mutual “why” and to explore how and why equity was the driving value for each of the members of the network (Valdez et al., 2020).

As the network examined and defined its core Problem of Practice, SINC was also recruiting diverse stakeholders to participate. Part of the potential of networked improvement communities is disrupting power dynamics by transforming the definition of expertise to include the lived experiences of school-embedded educators, the systems perspective of district leaders, and the research skills of university faculty. As equity-driven facilitators of the networks, we consciously and purposefully evolved the composition of the networks to intentionally include those “closest to the problem,” (Bryk et al., 2015) since their perspective and knowledge is integral to crafting promising improvements to wicked Problems of Practice. We also worked to shift the dynamic from hierarchical and deferential of authority to invite more voices to participate in the work of examining and defining Problems of Practice (Valdez et al., 2020).

In addition to actively working to shift traditional power dynamics with a specific focus on the inclusion of teachers’ voice as a force of influence, the SINC project also exemplifies equity as justice work through anchoring our problem investigation to systems-level, or root cause analysis (Hinnant-Crawford et al., 2023). These deliberations created the conditions for members of each network to better identify the entrenched practices, policies, and procedures that have privileged some students more than others and to respond with a renewed sense of possibility and commitment to adapt/transform their practices to better serve all students (Valdez et al., 2020), and by extension, to move toward greater justice for all students. This free-flowing analysis and generation of ideas helped the members of the SINC at various levels identify a broad and full range of factors which were contributing to the identified problem areas of inconsistent support for students’ mathematical reasoning. As such, we purposefully included the role of teachers and instruction, the district’s curriculum, the broader system factors, and the challenges experienced and posed by students themselves in this systemic landscape map. This “ground-up” analysis is illustrated in Figure 1. This Fishbone Diagram, or graphic tool to explore and display causes of a problem of practice, represented our collective efforts to acknowledge and deliberate upon the complex interplay of inputs that affect each of the persistent challenge of low mathematics achievement, and captures the authentic inputs of the university, district, and school stakeholders who contributed to this mapping.

Figure 1

School improvement fishbone diagram.

Working together to better “see” the district as a system required us to interact as a collective learning organization. To develop the organizational infrastructure for our collaborative improvement efforts, ne strategic approach we utilized was to highlight the importance of cultivating essential “Improvement Dispositions,” which included “adopting a learning stance,” “seeking the perspective of others,” and “engaging in disciplined inquiry” (Biag and Sherer, 2021). Over the last 3 years of leading the SINC, we have come to believe that the path to greater equity is through continuous improvement and that the path toward improvement is through collaborative learning. For us, this is equity in mission. Yet, we also must acknowledge that making this shift to become a learning group rather than an organization bound by certain expectations is quite challenging, given all the accountability pressures that dominate school systems today (Valdez et al., 2020).

To illustrate how ameliorating issues of equity requires innovation and the disposition to try, we have observed with our 15 SINC schools a tricky balancing act between adopting a learning stance and possessing an orientation toward action. Adopting a learning stance includes learning from others and accepting mistakes and failures as part of the process, whereas possessing an orientation toward action includes knowing things aren’t perfect but going with small changes anyway and accepting ambiguity (Biag and Sherer, 2021). With the district’s goal of improving math outcomes, focusing strictly on test improvement strategies could seem reasonable. However, schools in the NICs were not interested in such practices and were willing and interested in exploring multiple change ideas that shifted classroom responsibilities over the next 2 years. For example, six of the 15 SINC schools empowered students to engage with the elements of a rubric for scoring student responses on district reasoning problems, or teachers calibrated their scoring techniques to increase accuracy and precision. Additionally, seven schools ran PDSA cycles on discourse between and among students, and four ran PDSA cycles focused on building and practicing use of students’ mathematical vocabulary. With each of these examples, network members were working consciously to introduce change ideas that reflected an asset-based orientation rather than deficit-orientation of students’ and teachers’ capacity. And in re-orienting away from “skill and drill” test prep toward shoring up students’ understanding of their mathematical thinking and processing, the educators in the network aligned to an additional and essential component of equity-in-action (Farrell et al., 2023).

School improvement leadership academy: designing curriculum

The School Improvement Leadership Academy (SILA) is CEii’s state-wide and regional effort that invites principals and assistant principals from Local Education Agencies (LEA) across Maryland and New Jersey to participate. Each LEA has a different context, and each school does. In most cases, the social, political, and educational context drives the LEA’s and individual schools’ approach toward improvement efforts. In school districts, context may drive the disrupting and addressing of inequities. In other districts, the path forward is more contentious due to the LEA’s larger community’s demographic, geographical, and political landscape. At the center of this improvement effort will be a Fellow’s (SILA principal and assistant principal participants) ability to examine and unpack their understanding of the intersection of equity, instruction, and improvements related to their leadership practices.

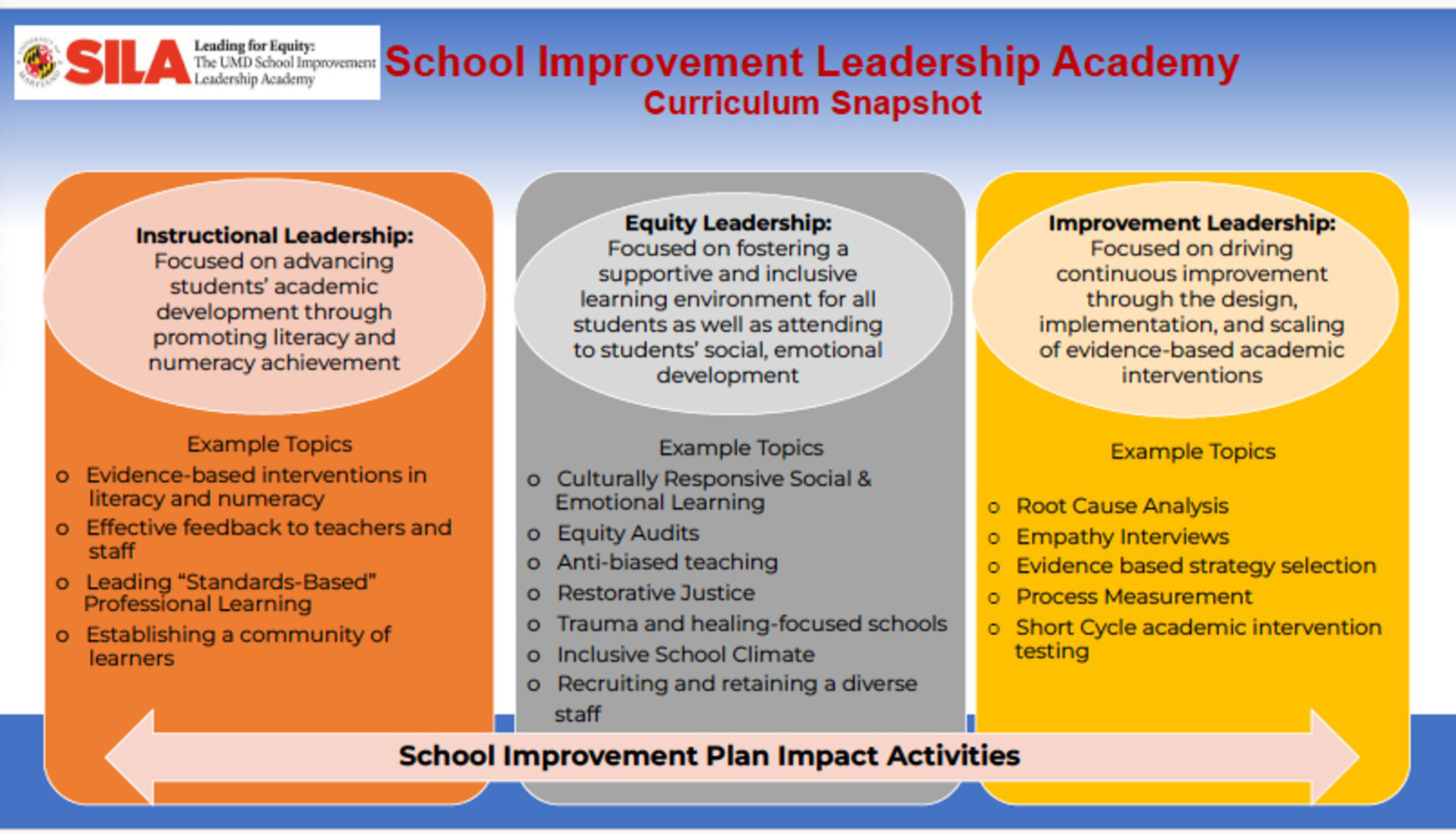

One academy goal is to enhance a SILA Fellow’s capabilities and disposition as a mission-driven, justice-seeking, continuous improver. A SILA Fellow who can “see the system” and work to disrupt the inequities in their current sphere of influence is at the heart of CEii’s work (Valdez et al., 2020). Effective leadership requires a coherent understanding of complex issues, concepts, and ideas. Three essential concepts are particularly relevant: (1) knowledge and lens on equity, (2) an intentional focus on instruction, and (3) a thoughtful approach and strategy for improvement. While powerful individually, these concepts are not isolated in a leader’s practice. Our responsive curriculum (Figure 2) is designed to help leaders recognize how these concepts are interwoven (or braided) to inform the planning and process for school improvement, student success and envisioning more equitable educational systems.

Figure 2

SILA curriculum snapshot.

The issue that we grappled with and felt most deeply about as a collective of researchers and educators working on the development of the SILA was how we position the academy as a vehicle for leaders to self-examine their understanding of their own mindsets and current practices. Shifting the mindsets and lenses of the SILA leaders around the ideas of justice, power, anti-racism, culture, identity, belonging, and traditionally marginalized students and educators in their work as continuous improvers is paramount, even as we also recognize that this shift is the first step in then transforming entrenched systems and structures of schooling (Dantley and Tillman, 2006; Farrell et al., 2023; Ishimaru and Galloway, 2021). In this aspect of our work, the self-examination and reflection of the SILA Fellows challenges how they perceive and respond to the inequities in the communities they serve.

In our first year of the academy, SILA Fellows met monthly for virtual learning sessions. We wanted SILA Fellows to interrogate every aspect of their disposition as leaders, from their own bias and cultural competence to the systems and structures they have in their respective schools that may exacerbate inequities. For example, in Year 1 of the academy, SILA Fellows must articulate their cultural identity while considering the identities of the students, staff, and communities they serve. SILA Fellows also conduct an equity audit that provides insights into strengths and equally important inequities that exist and persist. These examples reflect the ongoing commitment of the academy to shift mindset and practice.

As we embarked on developing the elements of the second-year experience for SILA Fellows, we thought of the intentionality Fellows would need in applying the concepts and theories presented in year one as well as the ongoing support that they would need to advance our three curriculum constructs moving forward. So, we designed two specific areas of focus, one for the principal and one for the assistant principal for their second year experience. Principals will focus on a problem of practice inside their school improvement plan (in literacy or mathematics) that they will address by leveraging improvement science tools (i.e., causal system analysis) and approaches. Assistant principals will identify a specific project to concentrate on for the school year within their school community. In addition, each principal and assistant principal will receive a coach that leverages the “Coaching for Equity: Conversations that change practice” (Aguilar, 2020) philosophy to support the SILA Fellows efforts throughout the year. One indicator in Aguilar’s coaching framework seeks to identify and shift limiting beliefs (Aguilar, 2020). When a coach is successful at recognizing when their SILA Fellow is harboring a biased belief and then persistently and effectively unpacks those beliefs throughout the coaching experience over the course of the year to shift mindsets, we see that as carrying the mission in equity forward (Aguilar, 2020; Farrell et al., 2023).

Principals and assistant principals often feel bound to their current circumstances or organizational norms (policies, practices, hierarchy, etc.) that inhibit their ability to seek authentic opportunities for justice. Thus, administrators default to compliance-driven leadership tactics (Valdez et al., 2020). The SILA curriculum strives for a shift in practice towards social justice, focusing on their current sphere of influence and pushing for leaders to disrupt inequities in their respective contexts. Yet early in the project, we found a variance in the readiness of the principals and assistant principals to make these shifts in practice. Some SILA Fellows voiced concerns about their ability and willingness to lead and do this intellectual and emotional work. Some even sought to find the “right person” instead of seeing themselves as the leader in this important, complex problem of practice. We learned that for the SILA Fellow to see themselves as possible disruptors and seekers of justice first, they needed to constructively struggle with their identities as leaders and shift their view of themselves from leader to transformational leaders (Bass, 1990). This feedback from the program participants ensured that we focused on examining their own cultural and social identity as a person and how that translates to leadership practice and influences their emerging identity as a continuous improver.

Racial and social justice collaborative

The Racial and Social Justice Collaborative (RSJC) began in 2023 with the aim of utilizing research-practice partnerships (RPP) to address challenges of racial and social justice within three school districts surrounding the University of Maryland, College Park. The RSJC strives to operationalize our conceptualization of equity in two ways. First our partnership strives for research that solves practical problems that our most marginalized communities face; our end goal is equity “for justice” for vulnerable populations. Second, this partnership strives for a research process that aims to disrupt the traditional power dynamic between researchers (“experts”) and practitioners (passive recipients of the “experts” knowledge; Farrell et al., 2023; Penuel and Gallagher, 2017). This is equity “as mission.”

Grounded in this two-pronged approach to equity, the RSJC positions researchers within the university to partner with local educational practitioners around the pressing challenges they face. To this end, the RSJC has three objectives: (1) designing and implementing an RPP focused on racial and social justice; (2) building trusting relationships between UMD faculty and students and local practitioners interested in developing partnerships around shared educational problems; and (3) building the capacity of UMD faculty and students, as well as local school district practitioners, to learn how to engage in impactful RPPs that are focused on equity-centered problems (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Racial and social justice collaborative framework.

Our early RSJC work has involved relationship building with the Equity Directors in local school districts. Bringing these directors together with university faculty has enabled us to create forums to explore our understanding of equity, as well as to surface common challenges around racial and social justice across the district contexts. This has also involved the creation of a Partnership Advisory, an external council spanning multiple colleges and offices within our university; and teachers, principals, and central office leaders from our four partner districts. The establishment of such an Advisory is critical to maintaining the RSJC vision around equity as justice; the Advisory holds us accountable for work that is ultimately in service of our most marginalized school communities. Our next phase of the work is the launch of the actual research-practice partnership, which will pool the expertise of our district-based practitioners and our university-based researchers.

Enacting this equity-based initiative has been a complex process. Putting researchers and practitioners into partnerships to solve shared problems (Farrell et al., 2023) necessitates building trust through relationships. Unlike research that is for the creation of “knowledge for knowledge’s sake,” mutually beneficial collaborations that foster highly relevant, usable knowledge (Coburn and Penuel, 2016; Penuel and Gallagher, 2017) are iterative, messy, and at times, ambiguous.

It is this ambiguous, fluid state of the work that would make it easy to abandon our equity-focused approach in exchange for a more traditional research approach. A more traditional research study would enable us to clearly outline our steps, to pre-plan our timeline, and to strategically develop research questions that we have data to answer. However, an RPP demands that we co-develop those research questions, build our outline together over time, and embrace the flexibility needed to revise our timeline to meet the needs of all the stakeholders (not just the needs of the researchers). Our commitment to equity as mission—to disrupt this traditional power dynamic between researchers and practitioners—pushes us to remain in the ambiguous state of partnerships. Our commitment to equity as justice reminds us that our end goal must be outcomes that improve the lives of marginalized communities.

We have found that this work is harder than expected, daunting, and sometimes exhausting. One persistent challenge has been norming our CEii understanding of equity to do the work of the RSJC; we have made progress, but there is more to do. Another, perhaps greater challenge, is to norm our understanding of equity with our practitioner partners. We know that “while RPP partners can ‘expand the zone’ to open new conversations, to accomplish their aims, the ideas of equity must resonate with others and successfully mobilize people to action within local settings” (Farrell et al., 2023, p. 201).

Conclusion

CEii’s arc of justice-oriented, equity work is in progress, but we have not reached a perfect end stage. As we continue to work in partnership with practitioners, we have adopted the mantle of radical pragmatists, which means that we accept that we are working in imperfect systems and that we as a collective team are still on a journey to define and operationalize equity in service of justice and mission. In this article we have engaged in the practice of reflection on three initiatives which we currently lead with school district partners.

Equity is a slippery term that can be easily co-opted by educational actors who are not working towards aims of educational justice (Hinnant-Crawford et al., 2023). At CEii, we have attempted to make it more concrete by defining and measuring the use of equity in each of our programs. Despite the shared definition, equity looks a bit different in the actualization of each program. In SILA, Fellows engage with equity via self-reflection, identity development, and building their experiences as continuous improvers to develop a personal practice of equity-based leadership. In RSJC, practitioners and researchers have come together to adopt an equity based lens when designing just solutions for complicated educational problems through research-practice partnerships.

We offer insight into the often invisible work of defying, embedding, and measuring equity through our reflection on these three initiatives. Like most improvement journeys, the process is not complete; instead, we continue to monitor our work to identify areas for improvement. We hope that by sharing the outcome of our reflection, additional boundary spanning education related practitioners and researchers will spend time examining how or if attempts at equity are: (1) justice oriented, (2) mission focused, and (3) successfully implemented. Time is a precious resource—one that is often in short supply in educational spaces. We recognize that engaging in reflective practice demands time and focus, but it is necessary to ensure that equity is in service of justice based work and not simply an organizational buzzword.

During this reflection, we struggled to arrive at a shared definition of equity, especially to square our goals of justice oriented work and the process of operationalizing equity. Despite using the term equity, at times we fall into the trap of having a difficult time pointing to explicit examples of the connection between the shared definition of equity and our actions leading improvement projects. As we began writing, we expected there would be a finished product to showcase our work. In actuality, the process of writing highlighted some important questions for our collective team. To what degree, if at all, does our shared definition impact our practices? Are we using the term equity in specific and discreet ways that will lead us to invite others to join our work with a clear understanding of both our definition of equity and the ways in which we operationalize it? These are not comfortable questions, and there are no easy answers. As individuals, and as a collective, we must identify, name, and share about the ways in which our stated goals of equity are not being actualized in our work. Despite the discomfort and at times disappointment, we invite other boundary spanners to engage in the process of reflective practice (Metz, 2001) as the field benefits when we each take time to investigate how (or if) we are defining and operationalizing equity in our improvement work.

Furthermore, this investigation also opens questions for further contemplation for CEii and hopefully other teams who design and lead improvement work. We conclude with a set of questions that our reflective practice suggests the field may need to wrestle with as we further conceptualize equity-focused improvement. How do we embrace the inherent tension between leading equity work and being on an equity journey at the same time? To what degree is a shared definition of equity needed as organizations take on different types of improvement projects? At what point do radical pragmatists slip into the practice of equity work with the goal of efficiency instead of justice? Are measures and indicators helpful in setting a sort of guardrail? How do our individual acts of reflective practice contribute to a definition of equity for the improvement field? We invite the field to respond.

Statements

Author contributions

SE: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CN: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PC: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DA: Writing – original draft. JS: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. DB: Writing – original draft. WV: Writing – original draft. LL: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The NIC work was funded in part through an Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) grant from Prince George’s County Public Schools. There is no grant number associated with the allocation for the NIC work with UMD. SILA is funded by a grant through the US Dept. of Education’s Office of Elementary and Secondary Education (OESE) Supporting Effective Educator Development Grant Program (SEED). The grant number is S423A220062. The RSJC work is supported by the University of Maryland Grand Challenges Grants program (https://research.umd.edu/gc).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

AguilarE. (2020). Coaching for equity: Conversations that change practice. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

2

AndersonE.CunninghamK. M.Eddy-SpicerD. H. (2024). Leading continuous improvement in schools: Enacting leadership standards to advance educational quality and equity. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis. 75–110.

3

BassB. M. (1990). From transactional to transformational leadership: learning to share the vision. Organ. Dyn.18, 19–31. doi: 10.1016/0090-2616(90)90061-S

4

BiagM.ShererD. (2021). Getting better at getting better: improvement dispositions in education. Teach. Coll. Rec.123, 1–42. doi: 10.1177/016146812112300402

5

BrykA. S.GomezL. M.GrunowA. (2011). Getting ideas into action: building networked improvement communities in education. Stanford, CA: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

6

BrykA. S.GomezL. M.GrunowA.LeMahieuP. G. (2015). Learning to improve: How America’s schools can get better at getting better. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

7

CoburnC. E.PenuelW. R. (2016). Research–practice partnerships in education: outcomes, dynamics, and open questions. Educ. Res.45, 48–54. doi: 10.3102/0013189X16631750

8

DantleyM. E.TillmanL. C. (2006). “Social justice and moral transformative leadership” in Leadership for social justice: Making revolutions in education. eds. MarshallC.OliviaM., 16–30.

9

Eddy-SpicerD. H.GomezL. M. (2022). “Accomplishing meaningful equity.” In The foundational handbook on improvement research in education. eds. PeurachD. J.RussellJ. L.Cohen-VogelL.PenuelW. R. (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers). 89–110. Available at: https://rowman.com/ISBN/9781538152348/The-Foundational-Handbook-on-Improvement-Research-in-Education

10

FarrellC. C.SingletonC.StamatisK.RiedyR.Arce-TrigattiP.PenuelW. R. (2023). Conceptions and practices of equity in research-practice partnerships. Educ. Policy37, 200–224. doi: 10.1177/08959048221131566

11

GillbornD. (2005). Education policy as an act of white supremacy: whiteness, critical race theory and education reform. J. Educ. Policy20, 485–505. doi: 10.1080/02680930500132346

12

Hinnant-CrawfordB.LettE. L.CromartieS. (2023). “ImproveCrit: Using critical race theory to guide continuous improvement” In Continuous improvement: a leadership process for school improvement. eds. AndersonE.HayesS. D., (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, Inc.), 105.

13

IshimaruA. M.GallowayM. K. (2021). Hearts and minds first: institutional logics in pursuit of educational equity. Educ. Adm. Q.57, 470–502. doi: 10.1177/0013161X20947459

14

Ladson-BillingsG. (2006). From the achievement gap to the education debt: understanding achievement in U.S. schools. Educ. Res.35, 3–12. doi: 10.3102/0013189X035007003

15

Ladson-BillingsG. (2021). I’m here for the hard re-set: post pandemic pedagogy to preserve our culture. Equity Excell. Educ.54, 68–78. doi: 10.1080/10665684.2020.1863883

16

MetzM. H. (2001). Intellectual border crossing in graduate education: a report from the field. Educ. Res.30, 1–7. doi: 10.3102/0013189X030005012

17

National Equity Project. (n.d.). Educational equity definition. National Equity Project Frameworks. Available at: https://www.nationalequityproject.org/education-equity-definition (Accessed November 13, 2024).

18

PenuelW. R.GallagherD. J. (2017). Creating research practice partnerships in education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

19

SawchukS. (2021). 4 ways George Floyd’s murder has changed how we talk about race and education. Education Week. Available at: https://www.edweek.org/leadership/4-ways-george-floyds-murder-has-changed-how-we-talk-about-race-and-education/2021/04 (Accessed May 7, 2024).

20

ValdezA.TakahashiS.KrausenK.BowmanA.GurrolaE. (2020). Getting better at getting more equitable: Opportunities and barriers for using continuous improvement to advance educational equity. San Francisco, CA: WestEd.

Summary

Keywords

improvement, reflective practice, equity, K-12, research practice partnerships

Citation

Eubanks S, Neumerski CM, Callahan PC, Anthony D, Snell J, Blondonville D, Viviani W and Liccione L (2024) Fostering Improvement: a reflection on equity-centered improvement across three initiatives. Front. Educ. 9:1434362. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1434362

Received

17 May 2024

Accepted

26 November 2024

Published

20 December 2024

Volume

9 - 2024

Edited by

Erin Anderson, University of Denver, United States

Reviewed by

Shizhou Yang, Payap University, Thailand

Ashley Seidel Potvin, University of Colorado Boulder, United States

Kristina Astrid Hesbol, University of Denver, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Eubanks, Neumerski, Callahan, Anthony, Snell, Blondonville, Viviani and Liccione.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Segun Eubanks, seubank2@umd.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.