- 1Research Institute of Child Development and Education, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 2IPABO University of Applied Sciences, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Social justice-oriented teacher education has emerged as a critical area of inquiry within the field of education. Drawing on 60 empirical papers, this scoping review examines what shared principles can be distinguished in how teacher educators shape their social justice-oriented teacher education practices. Social justice-oriented teacher education practices are characterized by their focus on identifying structural inequities and disrupting unjust hierarchies, for example, in which knowledge and perspectives are undervalued or marginalized. Social justice-oriented teacher education actively engages with the context and communities in which teaching takes place. In their curriculum and pedagogical approach, teacher educators pay attention to unequal power relations and centralizing marginalized perspectives. The papers included in this review further emphasize the importance of critical reflection and enacting shared principles in ways that fit the local context and power dynamics.

1 Introduction

Over the past decades, many teacher educators and scholars have introduced teacher education practices to fight enduring inequities in education and the roles schools and teachers may unconsciously and unwillingly play in perpetuating structures of inequity that affect students from marginalized groups, including students of color and Black, Indigenous, LGBTQIA+, disabled, and economically disadvantaged students. Teacher education approaches to equity that focus on dismantling systems of oppression, power, and privilege in education and society are mostly known as social justice-oriented teacher education (Picower, 2012). In this review, we explore and analyze shared principles in social justice-oriented teacher education (hereafter referred to as SJTE) practices in the international literature.

Picower (2012, p. 562) defines social justice education as “an amalgamation of multiple fields that centers on issues of equity, access, power, and oppression.” According to Cochran-Smith (2010, p. 448), SJTE is not defined by its methods or activities and does not refer to every form of teacher education that deals with diversity or equity, but it is a “coherent and intellectual approach to the preparation of teachers that acknowledges the social and political contexts in which teaching, learning, schooling, and ideas about justice have been located historically and the tensions among competing goals.” While SJTE involves the preparation of teachers to navigate diversity and ensure equal treatment, its distinctive feature lies in the inseparable connection it establishes between equity and justice, shifting from a perspective of “helping those who just happen to be less fortunate” to engaging in “a vertical fight against a system of oppression” (Picower, 2021, p. 97).

Following among others Cochran-Smith (2010), Picower (2012), and Roegman et al. (2021), we define SJTE as various teacher education practices that share the goals of (1) preparing student teachers to teach from an equity perspective and thereby acknowledging the talents and needs of students from marginalized groups, (2) increasing critical awareness of systemic causes of inequity both within and outside student teachers' classrooms, and (3) supporting student teachers in fighting these inequities. We have chosen to include teacher education practices with various theoretical grounding (such as critical multicultural education, antiracist teacher education, critical pedagogy, critical race theory, or culturally relevant teaching) as long as they align with these goals and acknowledge systemic inequities.

Numerous education scholars emphasize that the concepts of justice and equity are frequently embraced in education policy, programs, and research (Cochran-Smith and Keefe, 2022; Liao et al., 2022; North, 2008). However, it is important to note that widely differing interpretations of these concepts exist, including neoliberal reforms in teacher education that have co-opted the “language of equity” but adopted goals and practices contradictory to the movements and theories from which this language originates (Cochran-Smith et al., 2016c). To elucidate our interpretation, we highlight the differentiation between “thin equity” and “strong equity,” described by Cochran-Smith et al. (2016a) and Cochran-Smith and Keefe (2022). They assert that numerous recent policy changes in education reflect a “thin equity” perspective, wherein schools and teachers are considered primarily responsible for abolishing educational inequity. From this perspective, it is not recognized that schools and teachers function within unjust structures perpetuating enduring societal inequalities and limit teachers' potential to be agents of change. From a “strong equity” standpoint, educational inequality is regarded in connection to broader societal inequities and social policies that contribute to upholding racialized and systemic disparities in education, health, housing, and employment. This entails that schools must not only provide equitable education but also recognize and actively seek opportunities to combat these inequities within and beyond the realm of teaching (Cochran-Smith, 2020; Cochran-Smith and Keefe, 2022). This review centers on papers in which the authors adopt a perspective corresponding with “strong equity.”

This review explores common teacher education practices that seek to contribute to reducing structural injustices, drawing on international literature. Research on SJTE is characterized by small-scale qualitative studies with a heavy emphasis on practitioner research, leading earlier reviewers to argue for more research beyond a single context's small scale (Mills and Ballantyne, 2016). In a recent review study, Liao et al. (2022) assessed the effectiveness of teacher education aimed at equity. In their analysis of practices, they focused on distinguishing the different levels at which interventions take place: the programmatic level, the curriculum level, the pedagogical approach, and the teaching and learning activities. In this review, we describe how teacher educators shape their SJTE practices. The review adds to the earlier work of Liao et al. (2022) in that it offers further concretization through a detailed analysis of the practices at the various levels they distinguish. We not only focus on curriculum but also pay attention to how principles of SJTE are shaped in interactions with both the classroom and the context in which teaching and learning occur.

This review will focus on discerning patterns in various SJTE practices, highlighting shared attributes of practices in different contexts. Our analysis does not center on evaluating the effectiveness of specific practices but provides insight into the various approaches by which teacher educators integrate shared principles into their practices. Furthermore, our objective is to provide guidance to teacher educators committed to fostering justice by presenting foundational principles for developing social justice-oriented practices in their own educational contexts. We aim to inspire both action and critical reflection by providing insight into these principles, considerations, and activities more practically than earlier reviews. Our research question is: What shared principles can be distinguished in the ways teacher educators shape their social justice-oriented teacher education practices?

2 Method

2.1 Identification and selection of relevant studies

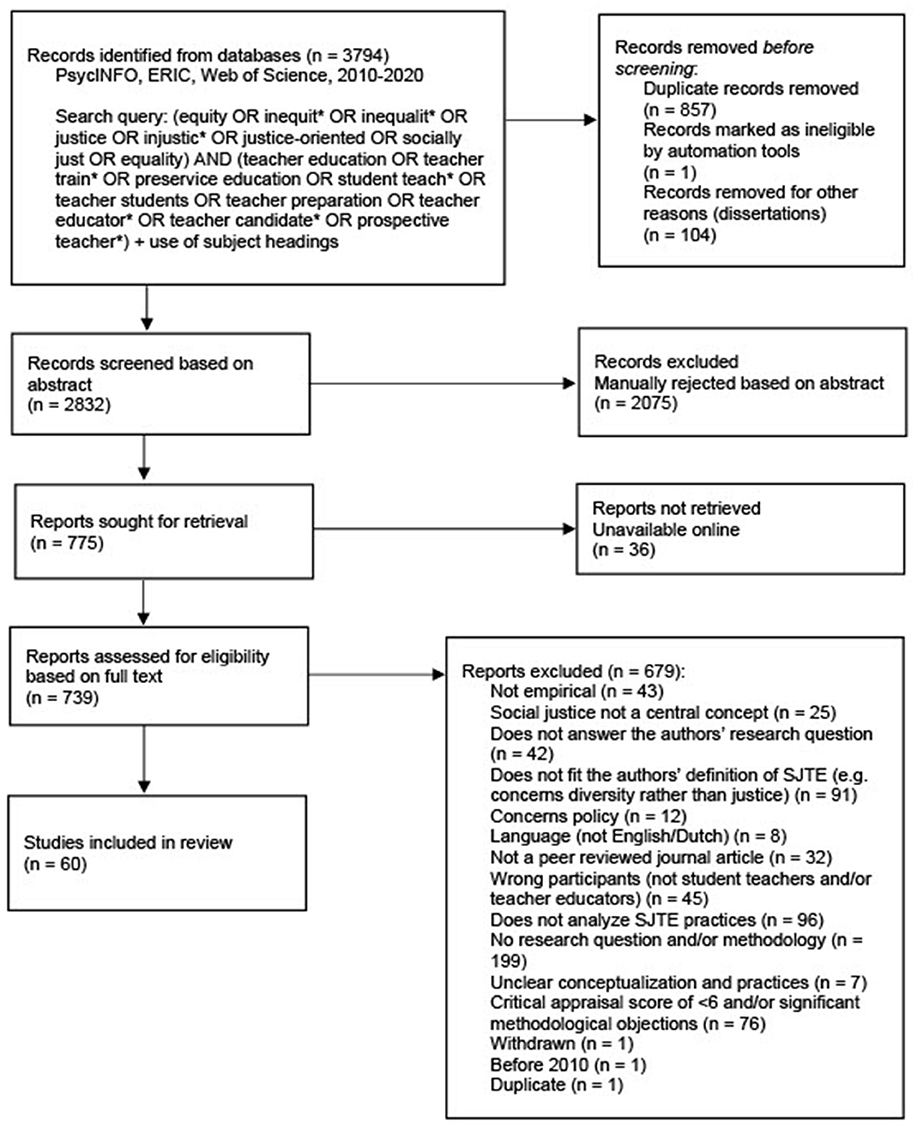

This review was conducted using a scoping review methodology, following PRISMA guidelines for scoping reviews (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005; Tricco et al., 2018). A scoping review was considered a good fit for the broad nature of the research question and the inclusion of a variety of designs, objectives, and methods while maintaining a systematic and rigorous procedure for selecting and screening the articles. Database searches were conducted in ERIC, PsycINFO, and Web of Science, using a search string developed and tested in collaboration with a subject librarian specialized in educational sciences. The authors searched for articles containing justice (or equity or equality) and teacher education in the abstract, keywords, or title, focusing on peer-reviewed articles written over 10 years, starting from 2010. As Arksey and O'Malley (2005) argue, setting a limited time frame for a scoping review is often necessary for practical reasons. Since scholarly work from before 2010 has already been acknowledged in earlier reviews such as those by Kaur (2012), Mills and Ballantyne (2016), and Cochran-Smith et al. (2016b), a decade-long time period leading up to the time of the search was selected. This timeframe was considered a good balance between capturing important developments and perspectives that have emerged within the field and adhering to practical limitations that required a manageable scope. The search query is described in Figure 1 (Page et al., 2021).

Figure 1. PRISMA statement (Page et al., 2021).

The database search resulted in 3,794 records. After deduplication, 2,832 results were left to screen. The abstracts of these 2,832 articles were screened by the first author using Rayyan. All authors decided on the eligibility criteria in a general way before the screening process started. Since the terms “justice” and “equity” are subject to many different interpretations in the literature on teacher education (Cochran-Smith et al., 2016b; Kaur, 2012), a screening criterion based on the definition of SJTE was employed by the researchers, excluding studies attending to diversity, cultural differences, or educational needs without discussing structural inequalities. Studies that acknowledged both the pedagogical and the political aspects of SJTE were included, analyzing practices (e.g., a course, activity, or program) aimed at challenging structural inequities (Cochran-Smith, 2004). For example, a paper might have been included initially because of its title and abstract, which framed the activities described as a social justice intervention, but later excluded upon full-text review when it became clear that the approach focused primarily on developing multicultural competence without addressing structural injustices or unequal power relations.

Approximately 5% of the abstracts were screened by at least two authors to ensure interrater reliability. If two authors disagreed or had doubts about a paper's inclusion, all four authors discussed it. Seven hundred and seventy five articles were included based on the screening of abstracts. During screening the full-text papers for eligibility and quality, further specifications of the screening criteria were made as familiarity with the literature grew. For example, the authors decided to include only empirical papers with student teachers or teacher educators as participants. Approximately 7% of the full papers were read and discussed by two or more authors to assess eligibility.

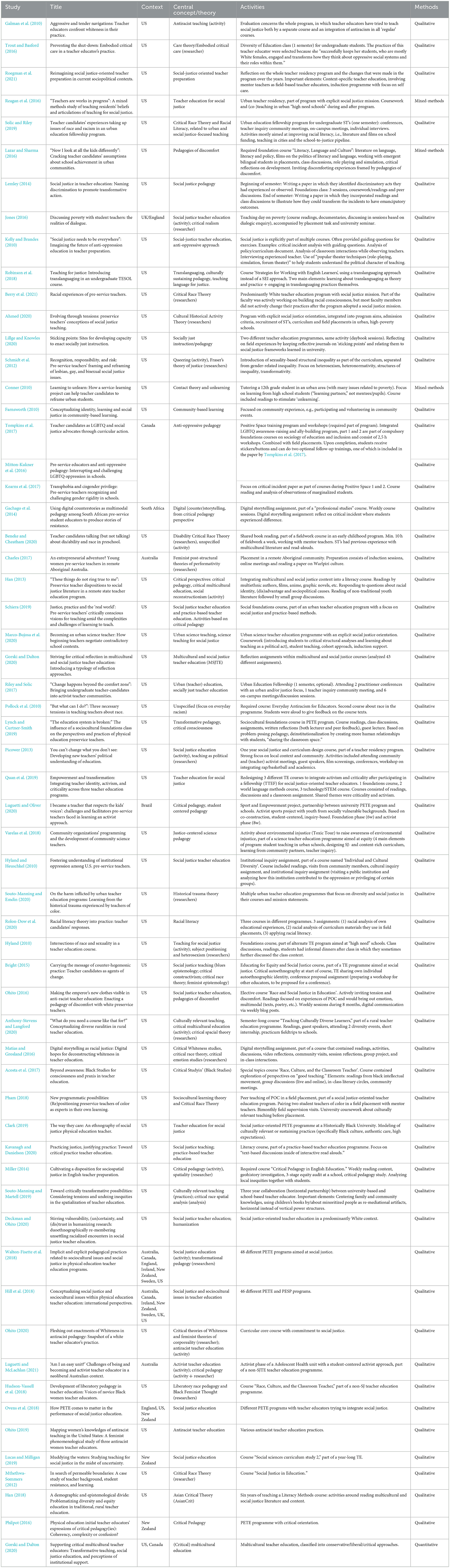

The first author then assessed the methodological quality of the papers using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research to assess the methodological quality of the empirical articles (Lockwood et al., 2015). Papers with a critical appraisal score of at least 6 (out of 10) were included in the final review unless there were significant methodological objections; papers with a score of 5 or 5,5 were further discussed with the other authors. Seventy six articles were excluded based on their score, and 199 were excluded for not containing a transparent methodology that allowed for critical appraisal. A comprehensive overview of all included articles is presented in Table 1.

2.2 Data charting and analysis

The analysis of the literature started with the process of data charting, sorting, and organizing key themes and other relevant elements of the papers summarized in Excel to create a broad overview of the literature (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005), such as the central concepts, forms of inequality, research questions and methodology, positionality of the teacher educator and researcher, and a description of the activities.

To identify key themes, all included papers were roughly coded to identify the central themes present in practices, reflections or conclusions presented by the authors. Examples of codes include “counterstories,” “peer teaching,” “activism outside classroom” and “individual vs. structural.” To ensure the reliability of the coding process, a sample of 25% of the articles was randomly selected by the second author, who then also employed open coding and compared her codes with those of the first author. This showed a high level of conceptual agreement between the authors: both authors consistently identified the same underlying central themes present in each article. There were some minor differences in interpretation or terminology. The authors resolved these differences through discussion, leading to a consensus on the central themes of each article.

Subsequently, all similar open codes were grouped into overarching themes that form the structure of the results section, which will describe how these elements are present in various teacher education practices. The grouping of the codes was discussed with the second author multiple times during the development of the coding scheme and checked and approved by all four authors before writing the results.

The results were written by the first author and then subjected to critical assessment by all co-authors on multiple occasions, thereby facilitating further refinements of the analysis. During the editing phase, the author(s) utilized ChatGPT 4-o and DeepL Write for identifying potential linguistic errors and recommendations for enhancing readability.

3 Results

The final selection of included articles contains 60 papers, with 56 qualitative research papers, 3 mixed-methods studies, and 1 quantitative study. Approximately two-thirds of the empirical studies were performed by teacher education practitioners who served as both teacher and researcher, using designs such as action research, collaborative auto-ethnography, or self-study to examine their own practices. More than two-thirds of the papers were based in the United States. Other locations included Canada (6), Australia (4), New Zealand (5), Brazil (1), the UK or England (4), South Africa (1), Ireland (2), and Sweden (2). While multiple articles explicitly discussed the influence of the identity and positionality of the teacher educators or the researchers, not all papers included a positionality statement.

Teacher educators for social justice focus on systemic oppression when addressing injustices, attending to structural inequalities related to factors such as race, gender, sexuality, class, language and (dis)ability. The reviewed papers predominantly addressed racism (e.g., Beneke and Cheatham, 2020; Berry et al., 2021; Ohito, 2016, 2020; Pollock et al., 2010; Solic and Riley, 2019; Souto-Manning and Emdin, 2020). Gender and sexuality were discussed 9 times (e.g., Bright, 2015; Hyland, 2010; Kearns et al., 2017; Mitton-Kukner et al., 2016; Ohito, 2019; Tompkins et al., 2017). Socioeconomic inequalities, language and (dis)ability were addressed less frequently, but still in more than 5 papers (e.g., Beneke and Cheatham, 2020; Hyland and Heuschkel, 2010; Lynch and Curtner-Smith, 2019). Although much of the reviewed literature analyzes individual activities such as university courses, placements, or community-based excursions, 12 papers mentioned that the evaluated activities were embedded in university-based or alternative programs with an explicit social justice mission. Some recurring elements of SJTE approaches can be identified within both single-course studies and programs. In our results, we discuss 5 shared principles in SJTE practices that we have identified in how teacher educators shape their practices. We explore these principles by focusing on the articles in which they are most explicitly addressed, as these authors provide detailed elaborations of them. This does not mean, however, that these principles are absent from other included papers that are not discussed in this specific paragraph. Researchers often make deliberate choices about which aspects of their practices to examine in depth, and which to address more broadly. In some cases, only a single activity or aspect is discussed in detail, while the authors emphasize that it is part of a larger, more comprehensive practice that falls outside the scope of the paper.

3.1 Challenging students to identify structural aspects of inequity

The first shared principle we discern in SJTE practices in the literature concerns how teacher educators challenge students to move from an individual understanding of inequity to one that incorporates structures. We illustrate this by describing different ways in which teacher educators address this goal: critical incident analysis, analyzing the institutional side of injustice, considering power in literacy and language, and integrating practices.

3.1.1 Critical incident analysis

In SJTE, a common activity is critical incident analysis, an assignment in which students are asked to analyze a specific case to identify how marginalization and privilege manifest in this particular context (Gachago et al., 2014; Kearns et al., 2017; Kelly and Brandes, 2010; Lemley, 2014). This includes examinations of the privileges of dominant groups, disrupting the idea that inequality only concerns those negatively affected by it. Lemley (2014) describes a paper assignment in which student teachers analyzed a situation from their own schooling experience in which they either witnessed or experienced discrimination. At the end of the course, in which they discussed their analyses with peers, they reflected on this case again and presented possible actions to fight this discrimination. This was meant to promote both their awareness and agency in fighting injustices.

Other authors offered more guidance in their critical incident paper assignments to prevent student teachers from selecting cases or asking questions that did not consider systemic inequalities. Kelly and Brandes (2010) provided student teachers with guiding questions and specific cases of critical incidents they could analyze. Kearns et al. (2017, p. 8) required student teachers to focus on observations of students “placed on the margins of the classroom or the school.” This was aimed at learning to recognize gender- and sexuality-based oppression, specifically “gender policing” by parents, educators, or peers. Students were asked to identify cases in which transgender or gender non-conforming students were either implicitly or explicitly forced to adhere to the gender binary, for example, through bullying, curriculum materials, locker rooms, or ascribing a particular color or activity to a gender (Kearns et al., 2017).

3.1.2 Analyzing the institutional side of injustice

Since multiple social justice-oriented teacher educators find students struggling to distinguish systemic disadvantage from individual mistreatment (Lemley, 2014; Schmidt et al., 2012), some teacher educators pinpoint their assignments at analyzing institutionalization of injustices. According to Pollock et al. (2010, p. 214), SJTE is “less about uncovering students' ‘personal' racism than considering how racist ideas in the world at large get ‘programmed' into individuals and activated in people's behavior.” Multiple authors paid explicit attention to structural factors that create systemic inequality, not limiting their explorations to what happens in the classroom. Schmidt et al. (2012) expanded beyond discussing homophobia to incorporate literature on underlying inequality structures such as heteronormativity. Hyland and Heuschkel (2010) introduced structural inequality through an institutional inquiry assignment, alongside other course activities. This assignment asked students to assess public institutions' roles in marginalizing or privileging certain groups, for example through barriers for non-English speakers (e.g., by monolingual policies), disabled people (e.g., by physical barriers), or low-income workers (e.g., by limited opening hours that were difficult to combine with working multiple jobs). The student teachers also analyzed (mis)representation, biases, and power imbalances, for example in artworks or occupational segregation. Mthethwa-Sommers (2012) integrated readings and discussions on how norms are embedded in structures, policies, and practices within schools and society.

3.1.3 Considering power in literacy and language

Another way to raise awareness of unequal power structures is by uncovering the role of language (education) in marginalizing or benefiting students based on their linguistic funds of knowledge (Lazar and Sharma, 2016; Marco-Bujosa et al., 2020; Quan et al., 2019; Robinson et al., 2018). Robinson et al. (2018) addressed the relationship between language, power, oppression, and privilege in a required course on working with English Language Learners. They discussed the injustices created by English-only approached that force students to assimilate, instead of appreciating and supporting their multilingualism. The authors also introduced students to the alternative of translanguaging practices by implementing them in their own teacher education classrooms. They emphasized the theoretical background of translanguaging and paid explicit attention to the relationship between language, power, and identity.

Another example is developing critical literacy, an approach to literacy development that explicitly considers power in language and knowledge construction (Beneke and Cheatham, 2020; Janks, 2013). Beneke and Cheatham (2020) stress that using multicultural books with children does not necessarily mean that racism is addressed in the classroom. They developed a shared book reading activity from a Disability Critical Race Theory perspective and analyzed how students' talk about race and (dis)ability reproduced, opposed, or ignored normative discourses of race and (dis)ability.

3.1.4 Integrating practices

While the previously mentioned papers evaluated one activity or course, identifying inequity can also be integrated into a longer program. The clearest example is provided by Kelly and Brandes (2010), who evaluated a yearlong SJTE program with multiple activities such as critical incident analysis, critical analyses of texts and curriculum, and explicit attention to the structural barriers people from marginalized groups encounter. They state that single activities (such as critical incident analysis) may help students analyze oppression and imagine transformative action. However, they are insufficient to take on a transformative inquiry stance when confronted with the complexity and constraints of being a novice teacher. Developing an ongoing transformative inquiry stance therefore requires actively supporting students to translate insights from the program into their everyday practices through a community of inquiry and action, with explicit critical reflection throughout the program rather than limited to an isolated course (Kelly and Brandes, 2010).

3.2 Acknowledging marginalized perspectives

A second principle in SJTE that emerged from the literature is its commitment to centralizing marginalized perspectives through purposefully involving forms of knowledge that are commonly overlooked, suppressed, undervalued, or stigmatized, We discuss three strategies: introducing counternarratives through storytelling, reconstructing the curriculum, and involving and appreciating students' knowledge.

3.2.1 Introducing counternarratives through storytelling

Counternarratives, derived from critical race theory, can serve multiple functions in education, such as disrupting stigmatizing and flawed conceptions of people of color, amplifying the voices of students of color, and help students deconstruct whiteness (Berry et al., 2021). Matias and Grosland (2016), two professors of color, analyze a digital storytelling project in which white students were asked to reflect on how whiteness had influenced their own experiences and positions and how they may (consciously or unconsciously) be involved in upholding unequal structures. With this project, they countered a dominant practice in predominantly white teacher education institutes where student teachers of color must share their experiences with disadvantage or microaggressions. The approach of Matias and Grosland (2016) shifted the burden of fighting racism away from people of color by focusing on whiteness. Gachago et al. (2014) combined critical incident analysis with digital storytelling by making students reflect on incidents in which they experienced difference by making videos about their stories. Some of these stories presented powerful counternarratives.

3.2.2 Reconstructing curriculum

Counternarratives can also be integrated into curriculum design. Rolon-Dow et al. (2020) designed an assignment in which student teachers reflected on personal racial experiences and studied how race was addressed in the curriculum. They learned to ask questions such as “Who is represented? Whose voices are being heard? Who is silenced?” (Rolon-Dow et al., 2020, p. 672). In a series of workshops, Mitton-Kukner et al. (2016) and Tompkins et al. (2017) focused on ways to disrupt silencing or stereotyping of LGBTQ+ people by raising awareness of ways in which curriculum can endorse transphobia or impositions of the gender binary. They also encouraged student teachers to learn to seize opportunities to make space for LGBTQ+ representation and challenge heterosexist norms in the curriculum by explicitly or implicitly questioning these norms or providing counterstories that challenge common stereotypes. Picower (2013) let students analyze the curriculum design process and modeled constructing a social justice-oriented curriculum by actively including social justice-based practices, such as community-based activities such as inviting guest speakers, attending local activist meetings, or integrating film, rap, and sports. Schmidt et al. (2012) examined their own curriculum, resulting in adjustments such as more readings and time devoted to sexuality-based inequalities, attending a local Sexuality Alliance and including literature that focuses on the structures of inequality responsible for acts of homophobia, like heterosexism and heteronormativity.

3.2.3 Involving and appreciating students' knowledge

SJTE aims to challenge “deficit perspectives” in which students from Black, Brown, multilingual, and/or disabled students are often seen as lacking and in need of compensatory measures. For example, both Beneke and Cheatham (2020) and Charles (2017) highlight how non-white children are often unfairly labeled “at risk” or neglected when their development or upbringing does not match white, Eurocentric standards. Various activities are used to counter deficit views: some based on Moll et al. (1992) “funds of knowledge” while others refer to different concepts. Conner (2010) describes a service learning tutoring project aimed at disrupting conventional teacher/pupil power dynamics and deficit perceptions of students living in urban communities by positioning student teachers and 12th graders as mutual learning partners and combining the project with critical readings about unlearning stereotypes. She encouraged students to learn from the knowledge present in urban communities and reconsider their initial perspectives of urban students as less intelligent or motivated. However, Gorski and Dalton (2020) stress the need for moving beyond the interpersonal level. They state that critical reflection assignments should shift the focus from merely examining and changing one's views and beliefs to dismantling the institutionalization and reproduction of such biases by actively examining possibilities and responsibilities for change both within and outside of the institutional context of the school.

3.3 Stimulating awareness of context, community, and (local) activism

A third principle of SJTE we discern in the literature focuses on making students aware of context, community, and activism. This includes integrating the sociopolitical context of (teacher) education and engaging with (local) communities and activism.

3.3.1 Integrating the sociopolitical context of (teacher) education

An important aspect that distinguishes SJTE from other approaches to equity in education is its emphasis on the sociopolitical context of education (Beneke and Cheatham, 2020; Han, 2013, 2018; Miller, 2014; Picower, 2013; Reagan et al., 2016; Roegman et al., 2021; Schiera, 2019; Varelas et al., 2018). According to Roegman et al. (2021), teacher educators (generally inspired by Hammerness and Matsko, 2013 concept of “context-specific teacher education”) often work with vague conceptions of “urban contexts” and address diversity, but lack attention to “bureaucratic structures, the political economy, and community networks” (Roegman et al., 2021, p. 152). To make their program more justice-oriented, they drastically increased placement length to increase familiarity with the culture of NYC public schools. They also added community-based assignments, such as a “community walk” in the neighborhood, in which student teachers were asked to “identify social and political elements of the neighborhood, analyze how they interact, and how they support or constrain learning opportunities” (Roegman et al., 2021, p. 156). Varelas et al. (2018) also evaluate a tour through their city, in which students were introduced to manifestations of environmental racism and disinvestment that predominantly hit Black and Brown communities. One of their goals was to prepare student teachers to form a vision of how science interacts with injustice and, therefore, see how science education can address the structural conditions affecting the local context of their schools. This disrupts the idea that (science) education is apolitical, which is considered an essential aspect of SJTE (Beneke and Cheatham, 2020; Marco-Bujosa et al., 2020; Picower, 2013; Quan et al., 2019; Reagan et al., 2016; Varelas et al., 2018; Wiggan et al., 2023).

SJTE often focuses on urban areas, which are generally more racially diverse than smaller towns. Solic and Riley (2019) note that the term “urban” is often used in education to avoid mentioning race and class. Multiple authors point out that SJTE is not only relevant for urban contexts as they specifically situate their research and teaching practices within a rural context (Anthony-Stevens and Langford, 2020; Han, 2013, 2018; Miller, 2014). Anthony-Stevens and Langford (2020) assert that local histories and diversity of students in rural areas are not always represented in education and the discourse on SJTE, and they make a plea for more complex and situated understandings of inequality in rural areas. An example of context-specific SJTE in a rural area is provided by Miller (2014). A “geohistory investigation” was used to build on local family histories to activate students' existing knowledge of meaningful historic events, stimulating students' consciousness of the structural inequities underlying these events. Starting with oral local history about a natural disaster that happened in their town, students learned to connect this to the process of gentrification that followed this disaster and was a deciding factor for the segregation still present in the local education system. This example combines an investigation of the sociopolitical context of education with the acknowledgment of marginalized perspectives. The class learned to relate current problems around segregation in education to the oral histories students already had knowledge of, demonstrating that students and their communities already have an understanding of inequality, whether rational or embodied, that can be triggered through justice-based education (Miller, 2014).

3.3.2 Engaging with local communities and activism

A way of connecting with the local context in SJTE is by engaging with local communities. Placements or service learning projects in Black, Brown, and/or economically deprived communities are often part of US-based urban teacher education programs (Ahmed, 2020; Conner, 2010; Lazar and Sharma, 2016; Pham, 2018; Reagan et al., 2016; Schiera, 2019). In the Australian context, Charles (2017) reports on placement in remote Aboriginal Australia, often the first time student teachers learn about Aboriginal education and communities. Community-based learning is also a central concept in the practices of Farnsworth (2010) and Picower (2013), who stimulate students to participate in local community meetings and integrate local issues and experts in their seminars and courses. While Farnsworth (2010) emphasizes volunteering in community events, Picower (2013) focuses on attending political community activism by letting student teachers attend a political economy lecture organized by local community actors. In this workshop, the student teachers were introduced to issues of power, the functioning of capitalism in education, and the resistance formed by teachers, parents and community advocates of color. Varelas et al. (2018) also introduced student teachers to community activism, making students see both the oppression and resistance of Black and Brown communities.

Providing teacher education that is rooted in activism is explicitly considered an important element of SJTE by multiple authors (Acosta et al., 2017; Ahmed, 2020; Kelly and Brandes, 2010; Picower, 2013; Quan et al., 2019; Riley and Solic, 2017; Roegman et al., 2021; Solic and Riley, 2019; Varelas et al., 2018). For example, Roegman et al. (2021) developed a lecture series called “Teacher as Activist.” In this series, they invited other scholars and local community actors to make student teachers examine stereotypes and strengths of the specific communities they would be teaching in and to develop ways to fight structural problems affecting these communities without lapsing into stereotypes and deficit views. Kelly and Brandes (2010) related their social justice teaching to the work of community actors by encouraging student teachers to engage with (local) activist groups. Ahmed (2020) emphasizes that developing activist goals and practices should be connected to students' lived experiences. Especially for BIPOC student teachers, engaging with resistance in marginalized communities can make teacher education more meaningful (Acosta et al., 2017). Riley and Solic (2017) and Solic and Riley (2019) highlight the challenge of stimulating teacher activism beyond providing more culturally relevant instruction. Connecting to existing activist communities can address this challenge. In their program, student teachers attended teacher inquiry meetings and practitioner conferences for urban and justice-oriented teachers, where they could learn from the perspectives of experienced teachers of color integrating social justice into their work. The program also included discussion sessions with the student teachers in which they could learn from each other and social movements like Black Lives Matter (Riley and Solic, 2017; Solic and Riley, 2019).

3.4 Striving for socially just instruction and teaching practices

While the examples from the previous section actively seek the connection between education and society outside of the classroom, other papers in our review focus more on how to provide socially just instruction through power redistribution, practicing and modeling socially just teaching practices, and making room for learning from peers.

3.4.1 Power redistribution

Numerous authors discuss how they align their teaching with theories of socially just education, accounting for power dynamics in the classroom and rejecting the “banking model of education” as described by Freire ([1970] 2005) that positions teachers as all-knowing and students as empty vessels to be filled with knowledge (Clark, 2019; Luguetti and Oliver, 2020; Lynch and Curtner-Smith, 2019; Marco-Bujosa et al., 2020; Ovens et al., 2018; Picower, 2013). For instance, Marco-Bujosa et al. (2020) criticize scripted curricula, authoritarian teacher attitudes and the centralization of general content knowledge over depth and meaningful learning. Picower (2013) emphasizes challenging inequitable power structures in classrooms as a means of initiating social change. The act of creating room for students to take power into their own hands, and making important decisions based on students' needs and lives, is visible in multiple studies referring to critical pedagogy (Luguetti and McLachlan, 2021; Luguetti and Oliver, 2020; Lynch and Curtner-Smith, 2019; Picower, 2013). According to Luguetti and Oliver, critical education is incompatible with a banking model approach. They designed a student-centered, inquiry-based, and co-constructive project in their Physical Education Teacher Education (PETE) program, in which student teachers collaborated with youth from socially vulnerable backgrounds in developing an activist sport project where they co-created activities that tackled the struggles of the young people. A critical view on power relations in the classroom is also discussed in Marco-Bujosa et al.'s (2020) analysis of student teachers' reflections on a social justice-focused urban science teacher education program. One of the main points students took from the program is learning to take on a role that is more facilitating than authoritarian. Lynch and Curtner-Smith (2019) and Hudson-Vassell et al. (2018) applied the principle of power distribution to their own practices. In the course described by Lynch and Curtner-Smith (2019), students participated in deciding on deadlines, assignments, and other aspects of the course. Additionally, students' preferred working methods were accommodated by incorporating journaling, art-based approaches, and other techniques alongside readings and discussions. The authors concluded that this pedagogical strategy positively impacted students' willingness to engage with the work of developing a critical consciousness of structural inequalities. Hudson-Vassell et al. (2018) actively positioned themselves as both teacher and learner, striving for co-construction of knowledge and a liberatory pedagogy.

3.4.2 Practicing and modeling socially just teaching practices

The practices of Lynch and Curtner-Smith (2019) can be seen as an example of how teacher educators model socially just practices for their student teachers, supporting them in developing socially just practices as well (Bright, 2015; Lillge and Knowles, 2020; Lynch and Curtner-Smith, 2019). Lucas and Milligan (2019) describe how student teachers valued the modeling of concrete practices, such as the introduction of methods like a Socratic seminar or community of inquiry to deal with heated discussions around justice-related topics. Clark (2019) analyzes how social justice was modeled at a historically Black University. Teacher educators modeled culturally relevant and sustaining practices to do justice to student teachers' backgrounds and help them imagine how they can bring social justice into practice. For example, they ensured that Black culture was valued in the program, and teacher educators paid explicit attention to Black culture and code-switching. Another specific aspect of this teacher education program was their “tough love” approach, in which they aimed to combine high expectations with authentically caring for students as a form of culturally relevant practice.

3.4.3 Making room for learning from peers

Creating room for student teachers to both be learners and teachers to their classmates is seen as another way of redistributing power, thereby disrupting the banking model of education. Bright (2015) describes a course in a SJTE program in which student teachers used their critical reflections on practices, “blind spots” and discomfort to educate other teachers. Students worked together to critically reflect on a problem they may have encountered and prepare a conference-like workshop to teach their newfound knowledge to other educators. For example, student teachers would learn and teach about the difference between being an ally and an advocate for students, the US school-to-prison pipeline, intersections between racism and ableism in special education, or cultural appropriation through Halloween costumes. With this conference assignment, students would both develop their own consciousness and collaborate with peers to create change.

Having students take the role of expert is also discussed by Pham (2018), who decided to pair student teachers of color during their field placement to analyze how this impacted their learning process. During this placement, the student teachers took on both the role of the teacher and of the learner. In informal conversations based on a trusting relationship and shared lived experiences as women of color, the student teachers reflected critically on the limitations of their positionality and the differences between their views and those of their mentor teachers. Learning from peers, especially peers from marginalized backgrounds, was also described by Solic and Riley (2019), Kelly and Brandes (2010), Gachago et al. (2014), Marco-Bujosa et al. (2020), and Hyland (2010).

3.5 Disrupting hierarchies in knowledge construction

The final principle we identified in the SJTE literature concerns its critique of the perception of academic knowledge and Western epistemologies as superior to practitioner knowledge and lived experiences. In this section, we describe three forms of teacher education practice that disrupts views on knowledge construction that can reproduce white supremacy and inequity: valuing lived experiences as knowledge, disrupting the theory/practice binary, and creating more equal collaboration between scholars, students, and practitioners.

3.5.1 Valuing lived experiences as knowledge

Earlier, we explored counternarratives' capacity to acknowledge and centralize marginalized perspectives. Furthermore, multiple scholars underscore the significance of counternarratives and lived experiences, for example, through family histories, emotions, and art-based approaches, to disrupt the dominance of Eurocentric values of what counts as knowledge (Deckman and Ohito, 2020; Matias and Grosland, 2016; Ohito, 2016; Souto-Manning and Martell, 2019). An example is provided by Acosta et al. (2017) in their Critical Study in approach, which employs multi-modal, interdisciplinary, and multisensory experiences to examine injustices in “the African American educational experience” (Acosta et al., 2017, p. 243). Activities included readings about schools and racism from Black scholars, group discussions, literature circles, and activities outside the classroom where student teachers could connect with Black communities, like interviews with retired African American teachers. For Acosta et al. (2017), forming new theory and consciousness through lived experience is a central aspect of their approach. Through analyzing daily situations where Black individuals face injustices from an Indigenous perspective, student teachers cultivate empathy and a deeper understanding of the underlying structures.

Other examples are found in the work of Ohito (2016, 2019), who emphasizes the power of the body in disrupting race- and gender-based misrecognition of knowledge production. For example, her use of “pedagogies of discomfort” in SJTE stimulates participants to transcend cognitive analyses of race and racism and understand oppression through the body. By collectively researching bodily experiences of discomfort, tensions, and emotions that came up when the n-word was used, student teachers deepened their understanding of racism. For example, they learned through experience how their embodied responses, such as feeling awkward, angry, or guilty, unintentionally hindered naming and acting on racism. According to Ohito (2016), learning through emotions and bodily experiences holds an emancipatory potential to deepen connection in antiracist teaching and disrupt white supremacist norms in (teacher) education. This aligns with the conclusions of Galman et al. (2010), who show how trying to prevent feelings of discomfort from arising and staying in the classroom can hinder antiracist teaching. Sticking to white feminine norms of niceness and glossing over racism can facilitate non-participation of white students and prevent engagement with race-based inequities. Furthermore, Ohito (2019) sheds light on the practices and knowledges of other teacher educators, such as a Black teacher educator called Victoria. Victoria invites both student teachers and teacher educators to analyze how their bodies are connected to structural injustices and shares how her understanding and practices of antiracist teacher education are connected to her body's experiences of racialized traumas within her family history (Ohito, 2019).

3.5.2 Disrupting the theory/practice binary

Another way to disrupt hierarchies is by centralizing and re-valuing knowledge gained through practice. Souto-Manning and Martell (2019) critique the misconception that knowledge is gained in universities and merely applied in schools. They argue that this viewpoint perpetuates Eurocentric epistemologies, reinforces notions of white superiority, and contributes to the misrecognition of marginalized communities and the roles of mentor teachers as school-based teacher educators (Souto-Manning and Martell, 2019). We discuss examples of teacher educators who centralize learning from practice, possibly disrupting the misrecognition of the school as a site for knowledge production. Lillge and Knowles (2020) also critique the idea of theory as something to be learned in university and practice as a place for application. Their approach entails student teachers learning about social justice frameworks by practicing socially just instruction during field experiences and reflective journaling. Based on an analysis of two SJTE programs, they plead for more explicit reflections on “sticking points” in practical situations, such as conflict with mentor teachers about interpretations of social justice frameworks. They argue that such moments of conflict, tension, or dissonance can spark true and ongoing learning. Kavanagh and Danielson (2020) and Schiera (2019) strengthen the role of practice as they integrate social justice teacher education with principles of practice-based teacher education. Kavanagh and Danielson (2020) let students plan, rehearse, and record their lessons about youth literature to analyze their pedagogical strategies and develop new knowledge together. Schiera (2019) works on providing and analyzing “core practices” in which social justice principles are applied, such as methods to address bias in school books, to help student teachers struggling with translating their insights into practice. By addressing the dilemmas and questions that arise from practice in a way that asks student teachers to analyze how practices either reproduce or challenge inequities, they are stimulated to develop an understanding of what social justice-oriented teaching entails without leading to the “de-skilling of teachers” as is often feared in practice-based SJTE. Pollock et al. (2010) offer a further concretization of the practical guidance that learning core practices can provide: “general principles for antiracism that can be carried around in one's head; more specific tactics for antiracism that can be tried in any given situation; and super-specific ‘solutions' for specific situations that arise in real-life practice” (Pollock et al., 2010, p. 215). To tackle all these levels, they fostered discussion on actual scenarios in which student teachers analyzed possible antiracist actions together instead of providing them with clear-cut answers, rules, or steps that don't acknowledge the complexity of antiracism in practice. The discussions encouraged student teachers to use their critical consciousness to elicit strategies and principles from these situations that may provide guidance in future teaching and evaluate the helpfulness and harmfulness of these strategies. However, Schiera (2019, p. 942) does warn for developing tools for social justice-oriented practice without critical consciousness, as “one cannot recognize moments of inequity that spur the need to take action.” Another risk is mentioned by Quan et al. (2019), who assert that fields like math and science are often incorrectly considered apolitical and ahistorical, and a practice-based approach can accidentally enforce whiteness and hinder explorations of social justice issues. They describe how a teacher educator changed their practices to address power and politics in STEM more explicitly and disrupt this apolitical and ahistorical view, for example, by critically analyzing algorithms and statistics on security in neighborhoods.

3.5.3 Creating more equal collaborations between scholars, students, and practitioners

Hierarchies around knowledge construction can also affect how collaborations between university-based and school-based teacher educators are organized (Roegman et al., 2021; Souto-Manning and Martell, 2019). In their long-term collaboration as a university-based and a school-based teacher educator, Souto-Manning and Martell (2019) respond to the misrecognition of the knowledge of school-based educators and communities through a co-teaching project in a NYC public school. Together, they worked on shaping meaningful placements in schools that mainly served students of color, emphasizing the strengths of these communities rather than presenting them as inferior. With their efforts, they aimed to “disrupt the physical locations and boundaries delineating teacher education, the pedagogical chasms that characterize it, and the relational roles of those involved in it (e.g., university-based teacher educators, school-based teacher educators)” (Souto-Manning and Martell, 2019, p. 2–3), providing a counternarrative that centers individuals and communities whose knowledge is often not recognized enough. Roegman et al. (2021) also challenge inequalities in the relationship between universities and schools. They emphasize the importance of collaboration and co-creation with mentor teachers in SJTE to ensure practices not only reach the goals of teacher educators but also support practitioners and schools. Their own practices confronted them with their own implicit biases and deficit ideas toward school-based teacher educators, realizing co-creation was essential to prevent student teachers from being unprepared for dealing with colleagues with different views on justice and challenging accountability-focused school contexts (Roegman et al., 2021).

Finally, the practices of Riley and Solic (2017) and Solic and Riley (2019), who centralized practicing teachers' expertise by engaging with social justice-oriented practitioner communities and setting up collective mentorship, can also be considered a form of fighting misrecognition of school-based educators and fostering meaningful and equitable relationships with practitioners in schools.

4 Discussion

4.1 Conclusions

This scoping review set out to map the field of social justice-oriented approaches to teacher education, showing how shared principles can be identified in various practices. In addition to the overview Liao et al. (2022) provided of strategies in SJTE, such as the use of curricular opportunities, storytelling activities, or pedagogical practices, we have further explored and concretized what these opportunities, activities, and practices entail. The literature shows that many teacher educators continuously seek opportunities to move from individual to structural analyses of injustice and to interrogate practices, institutions, and positionalities of their students and themselves. They also explicitly bring marginalized perspectives to the forefront, take power relations into account, and build on the knowledge and experiences of their students. They actively interact with the local sociopolitical context, looking for connection with school-based educators and community activists whose battles often take place outside of the classroom walls. In their pedagogical approach, they practice and model socially just teaching practices, disrupting power relations in the classroom. Moreover, they challenge Eurocentric epistemologies by valuing lived experience, bodies, and practitioner knowledge in constructing knowledge. Although not every principle is required to define teacher education as social justice-focused, many included papers show combinations of these principles to form coherent practices.

4.2 Implications for research and practice

In how teacher educators shape these principles in their practices, we see attempts by teacher educators to pursue “strong” rather than “thin” equity (Cochran-Smith, 2020; Cochran-Smith et al., 2016a; Cochran-Smith and Keefe, 2022). For example, by identifying structures that cause societal inequities, teacher educators strive to provide student teachers with an understanding of the mechanisms that reproduce inequality, both in the education system and through other institutions, social norms, and social policies. By actively seeking the connection with the sociopolitical context of education, teacher educators acknowledge how education practices alone will not be sufficient for radical social change. Justice also requires supporting underserved communities in their fight against, e.g., environmental injustice, gentrification, and the persistent stereotyping of and disinvestment in neighborhoods and communities.

Furthermore, we have provided deeper insights into what Liao et al. (2022) describe as pedagogical approaches. We examined how teacher educators and student teachers consistently interrogate their pedagogical methods and those of others to assess whether they model socially just practices or unintentionally reinforce social injustices. This review, which shows teacher educators employing diverse practices and theoretical frameworks but sharing goals, considerations, and principles, reinforces the notion presented by Cochran-Smith (2010) and other scholars that SJTE cannot be confined to a particular set of activities. Instead, it should be understood as an integration of justice-oriented principles across goals, pedagogical approaches, activities, research, and other facets of teacher education. Although this review examines how teacher educators bring SJTE into practice, it refrains from providing specific tools or best practices. Instead, the analyzed practices show the importance of critical consciousness, adjusting to unique contexts and power dynamics, and critical reflection. More than by activities, SJTE practices are characterized by their focus on identifying inequalities, disrupting hierarchies, and valuing the knowledge of students and communities. It tries to address both injustices on a classroom or local level and those stemming from broader societal systems such as colonialism, heterosexism, or capitalism. As teacher educators aspire to set an example for their students, they simultaneously engage in an ongoing learning journey regarding their own practices, beliefs, and the inequalities inherent to their contexts. However, the degree of critical reflection on the practices described varies from author to author. Within the field of SJTE, it is well documented that good intentions do not necessarily lead to positive change; efforts to challenge inequity inherently run the risk of inadvertently reproducing the very inequities they seek to address. Consequently, some of the papers included in this review position their approaches as alternatives to conventional practices within SJTE or critique the limitations of these practices. For example, while authors such as Farnsworth (2010) and Lazar and Sharma (2016) primarily highlight the positive impact of field trips to marginalized communities on student teachers' perceptions, Charles (2017) critically examines how such field experiences risk perpetuating colonial discourses and may even harm the communities involved. The critiques articulated in some papers raise critical questions about the practices described in others. This underscores the need for teacher educators to maintain a critical consciousness in order to assess whether and how particular principles can be implemented in ways that challenge, rather than reproduce, the injustices present in their particular contexts.

This review contains many examples of teacher educators adopting an intersectional approach. Some papers explicitly address intersections between a limited amount of identity markers, such as race and gender. In other papers, teacher educators address many inequitable systems but do not always analyze them all in-depth throughout the paper. This raises the question of what can be expected from teacher educators and scholars trying to work in an intersectional and inclusive way, integrating insights from multiple perspectives such as critical pedagogy, critical race theory, and disability studies. Based on a review of identity and intersectionality in SJTE, Pugach et al. (2019) warn for a “laundry list” approach, where scholars strive for inclusivity by explicitly mentioning all identity markers that could possibly be relevant. As an intersectional approach not only requires acknowledging that racism, sexism, and other structures interact but also examining how they interact, their recommendation is for scholars to acknowledge the complexity of intersecting inequalities and make a justified decision on what to examine rather than referring to a list that includes as many identities as possible without actively engaging with their intersections. Another perspective on the issue of simultaneously addressing many oppressive systems in education is provided by McLaren (2000, cited by Philpot, 2016), who critiques intersectional approaches to critical pedagogy that lack engagement with critical pedagogy's Marxist roots, hence leaving room for liberal rather than critical approaches. Our findings that only a small part of the papers that addressed class-based inequalities placed this in the context of critiques of capitalism as an underlying system (Philpot, 2016; Picower, 2013; Wiggan et al., 2023) support this warning.

Our decision to group different practices under the umbrella term of SJTE without actively examining various theoretical backgrounds, such as critical pedagogy or critical race theory (and their possible intersections), also carries these risks. In taking a more holistic approach to different identity markers, the critical issue remains whether injustice due to intersecting inequalities will receive enough attention or stay unnoticed. The findings of this review underscore the importance of tailoring SJTE to the local context and specific injustices prevalent in the communities where student teachers operate. It highlights the need for teacher educators to actively consider and assess what (intersectional) approach suits their unique contexts.

4.3 Limitations and suggestions for further research

Due to the choices made in our search strategy, eligibility criteria, and quality check, some relevant papers examining SJTE practices have fallen outside our scope, such as gray literature or research in languages other than English. A specific limitation of this study is the dominance of American-oriented research, which may contribute to the continued underrepresentation of research and practices from the Global South. Our search strategy and eligibility criteria could have influenced this outcome. For example, it could have led to the unintentional exclusion of papers by scholars who adopted a similar approach to SJTE as the authors but used different terminology, did not make this explicit enough to be recognized during the assessment of eligibility, or did not explain their approach with enough detail to allow for critical appraisal. With the selection made in this review, we do not claim to be exhaustive or suggest that other researchers on SJTE would have come to the same selection of articles. Furthermore, the under-representation of research from the Global South is a well-documented issue within the scientific community, partly attributable to the dominance of the English language and the limited publication of articles from these regions (Demeter, 2020).

Our research question prioritized a more in-depth examination of practices, as this is often neglected in the existing literature on SJTE. However, our research question did not focus on many other relevant issues addressed in the included papers, such as the impact of engaging with social justice issues on students from both privileged and marginalized backgrounds or the experiences and positionality of teacher educators. Furthermore, we have not critically assessed tensions or dilemmas inherent to the discussed principles in SJTE practices, as they may also unintentionally reinforce the inequities they are trying to challenge, for example by reinforcing stereotypes. We therefore believe that exploring how these dynamics within SJTE affect both student teachers and teacher educators, taking into account their positionalities, would be a fruitful subject for further research.

Finally, this review cannot address recent developments as it was conducted before the recent intensification of attacks on e.g., Critical Race Theory and transgender rights in the US, UK, and Europe. It can be expected that misinformation campaigns and pressure to adhere to laws that ban books with Black and LGBTQ+ characters or force teachers to “out” trans students to their (possibly unaccepting) parents will significantly affect teacher educators' practices. Given these circumstances, further research is needed into how teacher educators can uphold their SJTE practices under even more oppressive legislation. However, we hope this review will inspire and support teacher educators trying to find ways to continue striving for justice.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

NH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ML: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. LG: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MV: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by “Johan W. van Hulst Stichting” and “Stichting tot Steun bij Opleiding en Begeleiding van Leerkrachten in het Christelijk Basisonderwijs in Amsterdam e.o..”

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Janneke Staaks (subject librarian and information specialist at the University of Amsterdam) for her help in developing our search strategy. AI tools ChatGPT 4-o and DeepLWrite were solely used for identifying potential linguistic errors and recommendations for enhancing readability. No generative AI tools were used to create or develop any of the original content in this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acosta, M. M., Hudson-Vassel, C., Johnson, B., Cherfrere, G., Harris, M. G., Wallace, J., et al. (2017). Beyond awareness: black studies for consciousness and praxis in teacher education. Equity Excell. Educ. 50, 241–253. doi: 10.1080/10665684.2017.1301833

Ahmed, K. S. (2020). Evolving through tensions: preservice teachers' conceptions of social justice teaching. Teach. Educ. 31, 245–259. doi: 10.1080/10476210.2018.1533545

Anthony-Stevens, V., and Langford, S. (2020). “What do you need a course like that for?” Conceptualizing diverse ruralities in rural teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 71, 332–344. doi: 10.1177/0022487119861582

Arksey, H., and O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 8, 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

Beneke, M. R., and Cheatham, G. A. (2020). Teacher candidates talking (but not talking) about dis/ability and race in preschool. J. Liter. Res. 52, 245–268. doi: 10.1177/1086296X20939561

Berry, T., Burnett, R., Beschorner, B., Eastman, K., Krull, M., and Kruizenga, T. (2021). Racial experiences of pre-service teachers. Teach. Educ. 32, 388–402. doi: 10.1080/10476210.2020.1777096

Bright, A. (2015). Carrying the message of counter-hegemonic practice: teacher candidates as agents of change. Educ. Stud.-Aesa 51, 460–481. doi: 10.1080/00131946.2015.1098645

Charles, C. (2017). An entrepreneurial adventure? Young women pre-service teachers in remote aboriginal Australia. Teach. Teach. Educ. 61:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.10.013

Clark, L. (2019). The way they care: an ethnography of social justice physical education teacher education. Teach. Educ. 54, 145–170. doi: 10.1080/08878730.2018.1549301

Cochran-Smith, M. (2004). Walking the Road. Race, Diversity and Social Justice in Teacher Education. New York: Teachers College Press.

Cochran-Smith, M. (2010). “Toward a theory of teacher education for social justice,” in The International Handbook of Educational Change, eds. M. Fullan, A. Hargreaves, D. Hopkins, and A. Lieberman (Cham: Springer Publishing). doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-2660-6_27

Cochran-Smith, M. (2020). Teacher education for justice and equity: 40 years of advocacy. Action Teach. Educ. 42, 49–59. doi: 10.1080/01626620.2019.1702120

Cochran-Smith, M., Ell, F., Grudnoff, L., Haigh, M., Hill, M., and Ludlow, L. (2016c). Initial teacher education: what does it take to put equity at the center? Teach. Teach. Educ. 57, 67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.03.006

Cochran-Smith, M., and Keefe, E. S. (2022). Strong equity: repositioning teacher education for social change. Teach. Coll. Rec. 124, 9–41. doi: 10.1177/01614681221087304

Cochran-Smith, M., Stern, R., Sánchez, J. G., Miller, A., Keefe, E. S., Fernández, M. B., et al. (2016a). Holding Teacher Preparation Accountable: A Review of Claims and Evidence. Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center.

Cochran-Smith, M., Villegas, A. M., Abrams, L., Chavez Moreno, L., Mills, T., and Stern, R. (2016b). Research on teacher preparation: charting the landscape of a sprawling field. Handb. Res. Teach. 5, 439–547. doi: 10.3102/978-0-935302-48-6_7

Conner, J. O. (2010). Learning to unlearn: how a service-learning project can help teacher candidates to reframe urban students. Teach. Teach. Educ. 26, 1170–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.02.001

Deckman, S. L., and Ohito, E. O. (2020). Stirring vulnerability, (un)certainty, and (dis)trust in humanizing research: duoethnographically re-membering unsettling racialized encounters in social justice teacher education. Int. J. Qualit. Stud. Educ. 33, 1058–1076. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2019.1706199

Demeter, M. (2020). Academic Knowledge Production and the Global South: Questioning Inequality and Under-representation. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-52701-3

Farnsworth, V. (2010). Conceptualizing identity, learning and social justice in community-based learning. Teach. Teach. Educ. 26, 1481–1489. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.06.006

Gachago, D., Cronje, F., Ivala, E., Condy, J., and Chigona, A. (2014). Using digital counterstories as multimodal pedagogy among South African pre-service student educators to produce stories of resistance. J. E-Learn. 12, 29–42.

Galman, S., Pica-Smith, C., and Rosenberger, C. (2010). Aggressive and tender navigations: teacher educators confront whiteness in their practice. J. Teach. Educ. 61, 225–236. doi: 10.1177/0022487109359776

Gorski, P. C., and Dalton, K. (2020). Striving for critical reflection in multicultural and social justice teacher education: introducing a typology of reflection approaches. J. Teach. Educ. 71, 357–368. doi: 10.1177/0022487119883545

Hammerness, K., and Matsko, K. K. (2013). When context has content: a case study of new teacher induction in the university of chicago's urban teacher education program. Urban Educ. 48, 557–584. doi: 10.1177/0042085912456848

Han, K. T. (2013). ‘These things do not ring true to me': preservice teacher dispositions to social justice literature in a remote state teacher education program. Urban Rev. 45, 143–166. doi: 10.1007/s11256-012-0212-7

Han, K. T. (2018). A demographic and epistemological divide: problematizing diversity and equity education in traditional, rural teacher education. Int. J. Qualit. Stud. Educ. 31, 595–611. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2018.1455997

Hill, J., Philpot, R., Walton-Fisette, J. L., Sutherland, S., Flemons, M., Ovens, A., et al. (2018). Conceptualising social justice and sociocultural issues within physical education teacher education: international perspectives. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedag. 23, 469–483. doi: 10.1080/17408989.2018.1470613

Hudson-Vassell, C., Acosta, M. M., King, N. S., Upshaw, A., and Cherfrere, G. (2018). Development of liberatory pedagogy in teacher education: voices of novice BLACK women teacher educators. Teach. Teach. Educ. 72, 133–143. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2018.03.004

Hyland, N. E. (2010). Intersections of race and sexuality in a teacher education course. Teach. Educ. 21, 385–401. doi: 10.1080/10476210.2010.495769

Hyland, N. E., and Heuschkel, K. (2010). Fostering understanding of institutional oppression among US pre-service teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 26, 821–829. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.10.019

Janks, H. (2013). Critical literacy in teaching and research1. Educ. Inquiry 4, 225–242. doi: 10.3402/edui.v4i2.22071

Jones, H. (2016). Discussing poverty with student teachers: the realities of dialogue. J. Educ. Teach. 42, 468–482. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2016.1215553

Kaur, B. (2012). Equity and social justice in teaching and teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 28, 485–492. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2012.01.012

Kavanagh, S. S., and Danielson, K. A. (2020). Practicing justice, justifying practice: toward critical practice teacher education. Am. Educ. Res. J. 57, 69–105. doi: 10.3102/0002831219848691

Kearns, L. L., Mitton-Kükner, J., and Tompkins, J. (2017). Transphobia and cisgender privilege: pre-service teachers recognizing and challenging gender rigidity in schools. Canad. J. Educ. 40, 1–27.

Kelly, D. M., and Brandes, G. M. (2010). ‘Social justice needs to be everywhere': imagining the future of anti-oppression education in teacher preparation. J. Educ. Res. 56, 388–402. doi: 10.11575/ajer.v56i4.55425

Lazar, A., and Sharma, S. (2016). ‘Now i look at all the kids differently': cracking teacher candidates' assumptions about school achievement in urban communities. Action Teach. Educ. 38, 120–136. doi: 10.1080/01626620.2016.1155099

Lemley, C. K. (2014). Social justice in teacher education: naming discrimination to promote transformative action. Crit. Quest. Educ. 5, 26–51.

Liao, W., Wang, C., Zhou, J., Cui, Z., Sun, X., Bo, Y., et al. (2022). Effects of equity-oriented teacher education on preservice teachers: a systematic review. Teach. Teach. Educ. 119:103844. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103844

Lillge, D., and Knowles, A. (2020). Sticking points: sites for developing capacity to enact socially just instruction. Teach. Teach. Educ. 94:103098. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2020.103098

Lockwood, C., Munn, Z., and Porritt, K. (2015). Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 13, 179–187. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000062

Lucas, A. G., and Milligan, A. (2019). Muddying the waters: studying teaching for social justice in the midst of uncertainty. Study. Teach. Educ. 15, 317–333. doi: 10.1080/17425964.2019.1669552

Luguetti, C., and McLachlan, F. (2021). ‘Am I an easy unit?' Challenges of being and becoming an activist teacher educator in a neoliberal Australian context. Sport, Educ. Soc. 26, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2019.1689113

Luguetti, C., and Oliver, K. L. (2020). ‘I became a teacher that respects the kids' voices': challenges and facilitators pre-service teachers faced in learning an activist approach. Sport Educ. Soc. 25, 423–435. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2019.1601620

Lynch, S., and Curtner-Smith, M. D. (2019). ‘The education system is broken:' the influence of a sociocultural foundations class on the perspectives and practices of physical education preservice teachers. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 38, 377–387. doi: 10.1123/jtpe.2018-0258

Marco-Bujosa, L. M., McNeill, K. L., and Friedman, A. A. (2020). Becoming an urban science teacher: how beginning teachers negotiate contradictory school contexts. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 57, 3–32. doi: 10.1002/tea.21583

Matias, C. E., and Grosland, T. J. (2016). Digital storytelling as racial justice: digital hopes for deconstructing whiteness in teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 67, 152–164. doi: 10.1177/0022487115624493

McLaren, P. (2000). Che Guevara, Paulo Freire, and the Pedagogy of Revolution. Boulder, CO: Rowan and Littlefield.

Miller, S. J. (2014). Cultivating a disposition for sociospatial justice in english teacher preparation. Teach. Educ. Pract. 27, 44–74.

Mills, C., and Ballantyne, J. (2016). Social justice and teacher education: a systematic review of empirical work in the field. J. Teach. Educ. 67, 263–276. doi: 10.1177/0022487116660152

Mitton-Kukner, J., Kearns, L., and Tompkins, J. (2016). Pre-service educators and anti-oppressive pedagogy: interrupting and challenging LGBTQ oppression in schools. Asia-Pacific J. Teach. Educ. 44, 20–34. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2015.1020047

Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., and Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory Pract. 31, 132–141. doi: 10.1080/00405849209543534

Mthethwa-Sommers, S. (2012). In search of permeable boundaries: a case study of teacher background, student resistance, and learning. J. Excel. Coll. Teach. 23, 77–97.

North, C. E. (2008). What is all this talk about ‘social justice'? Mapping the terrain of education's latest catchphrase. Teach. College Rec. 110, 1182–1206. doi: 10.1177/016146810811000607

Ohito, E. O. (2016). Making the emperor's new clothes visible in anti-racist teacher education: enacting a pedagogy of discomfort with white preservice teachers. Equity Excell. Educ. 49, 454–467. doi: 10.1080/10665684.2016.1226104

Ohito, E. O. (2019). Mapping women's knowledges of antiracist teaching in the United States: a feminist phenomenological study of three antiracist women teacher educators. Teach. Teach. Educ. 86:102892. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.102892

Ohito, E. O. (2020). Fleshing out enactments of whiteness in antiracist pedagogy: snapshot of a white teacher educator's practice. Pedag. Cult. Soc. 28, 17–36. doi: 10.1080/14681366.2019.1585934

Ovens, A., Flory, S. B., Sutherland, S., Philpot, R., Walton-Fisette, J. L., Hill, J., et al. (2018). How PETE comes to matter in the performance of social justice education. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedag. 23, 484–496. doi: 10.1080/17408989.2018.1470614

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

Pham, J. H. (2018). New programmatic possibilities: (re)positioning preservice teachers of color as experts in their own learning. Teach. Educ. Quart. 45, 51–71. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26762168

Philpot, R. (2016). Physical education initial teacher educators' expressions of critical pedagogy(ies): coherency, complexity or confusion? Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 22, 260–275. doi: 10.1177/1356336X15603382

Picower, B. (2012). Practice What You Teach. Social Justice Education in the Classroom and the Streets. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203118252

Picower, B. (2013). You can't change what you don't see: developing new teachers' political understanding of education. J. Transfor. Educ. 11, 170–189. doi: 10.1177/1541344613502395

Picower, B. (2021). Reading, Writing and Racism. Disrupting Whiteness in Teacher Education and in the Classroom. Boston: Beacon Press.

Pollock, M., Deckman, S., Mira, M., and Shalaby, C. (2010). ‘But what can i do?': three necessary tensions in teaching teachers about race. J. Teach. Educ. 61, 211–224. doi: 10.1177/0022487109354089

Pugach, M. C., Matewos, A. M., and Gomez-Najarro, J. (2019). A review of identity in research on social justice in teacher education: what role for intersectionality? J. Teach. Educ. 70, 206–218. doi: 10.1177/0022487118760567

Quan, T., Bracho, C. A., Wilkerson, M., and Clark, M. (2019). Empowerment and transformation: integrating teacher identity, activism, and criticality across three teacher education programs. Rev. Educ. Pedag. Cult. Stud. 41, 218–251. doi: 10.1080/10714413.2019.1684162

Reagan, E. M., Chen, C., and Vernikoff, L. (2016). ‘Teachers are works in progress': a mixed methods study of teaching residents' beliefs and articulations of teaching for social justice. Teach. Teach. Educ. 59, 213–227. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.05.011

Riley, K., and Solic, K. (2017). ‘Change happens beyond the comfort zone': bringing undergraduate teacher-candidates into activist teacher communities. J. Teach. Educ. 68, 179–192. doi: 10.1177/0022487116687738

Robinson, E., Tian, Z., Martinez, T., and Qarqeen, A. (2018). Teaching for justice: introducing translanguaging in an undergraduate TESOL course. J. Lang. Educ. 4, 77–87. doi: 10.17323/2411-7390-2018-4-3-77-87

Roegman, R., Reagan, E., Goodwin, A. L., Lee, C. C., and Vernikoff, L. (2021). Reimagining social justice-oriented teacher preparation in current sociopolitical contexts. Int. J. Qualit. Stud. Educ. 34, 145–167. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2020.1735557