- Graduate School of Education, Fordham University, New York, NY, United States

Introduction: This comparative case study explores how educational leaders in three networked improvement communities (NICs) situated in the same school district use a continuous improvement (CI) approach, improvement science, to address equity-focused problems of practice. The district that is the focus of this study represents a critical case for understanding educational leaders' use of CI approaches as a lever for equity-focused school reform because the system and state in which it was situated had made ongoing investments in both advancing equity in schools and using various CI approaches.

Methods: Data collection and analysis focused on interviews with four district leaders and eight school leaders, observations of ~24 h of NIC meetings and planning meetings, and document collection. I draw on sensemaking theory to understand the factors that supported and/or constrained educational leaders' use of CI to advance equity, including more dominant and transformative equity work.

Results: All educational leaders in the study described and were observed attending to equity as they engaged in CI. The district's sustained investments in equity-focused reform, the use of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles, data use, and NIC facilitation each acted as important factors that shaped this process.

Discussion: Advancing equity is long term work that involves addressing deeply rooted beliefs, changing policies and practices, and redesigning systems. Study findings suggest that districts may be more successful in leveraging CI to advance equity when they combine this action-oriented approach with a sustained focus on disrupting oppressive mindsets, values, and beliefs that can hinder transformational change.

Introduction

This comparative case study examines how central office administrators in a community school district in the New York City Public Schools (NYCPS) established three networked improvement communities (NICs) of school leaders and supported them in using improvement science (IS; Bryk et al., 2015) to advance equity during the COVID-19 pandemic. “Educational equity means that each child receives what they need to develop to their full academic and social potential” (National Equity Project, n.d.). Thus, equity-focused continuous improvement requires a focus on the systems, structures, policies, practices, and beliefs that contribute to inequity (Ishimaru and Galloway, 2021). Some scholars argue that continuous improvement methods, such as IS, are well-suited to advancing equity because they encourage a focus on not only improvement for individual students and groups but also improvement that transforms systems to be more equitable and just (Eddy-Spicer and Gomez, 2022). Yet, successful examples of equity- focused continuous improvement in action are limited, and existing evidence suggests that continuous improvement approaches may allow for but do not guarantee a focus on equity (Bush-Mecenas, 2022; Viano and Stosich, 2024).

Continuous improvement (CI) is a term that describes a range of approaches with a shared focus on centering local problems, encouraging experimentation, engaging in cycles of inquiry, and working toward improvement across schools and systems (Yurkofsky et al., 2020). Unlike many comprehensive school reform models that encourage specific programmatic or instructional approaches, CI approaches offer a guiding framework to address any problem of practice in schools. There has been growing attention, policy, and funding focused on CI with the goal of both addressing particular problems in the field (e.g., chronic absenteeism, racial disproportionality in school discipline) and developing educator and organizational capacity to improve educational opportunities and outcomes for students (Peurach, 2016; Russell et al., 2020). Improvement science, an approach to CI, has gained popularity as a systematic approach to accelerating learning and improvement by working collaboratively in NICs to identify and address problems of practice through cycles of inquiry focused on developing, testing, and refining change ideas in the field (LeMahieu et al., 2017). Thus, adopting IS structures, such as NICs, and practices, such as cycles of inquiry, and using them to advance equity requires shifts in the work of educational leaders and the organizations in which they work.

As Mintrop and Zumpe (2019) explain, “Continuous quality improvement, according to the principles of IS or design development, calls for tight means-ends connections in which solutions are designed to address contextually diagnosed problems, and effectiveness is verified through practice-embedded metrics” (p. 297). In other words, CI requires leaders to define, address, and measure progress in ways that are unique to their context rather than simply apply existing interventions. CI methods place responsibility for problem solving and decision making on district and school leaders and, thus, demand new capabilities and skills (Grunow et al., 2018). Further, recent research suggests that practitioners may need to adapt CI approaches to maintain a focus on equity (Bush-Mecenas, 2022), adding to the complexity of adopting these approaches. Given the essential role of principals and other school leaders in coordinating improvement efforts (Stosich, 2017), particularly equity-focused improvement (Galloway and Ishimaru, 2017; Irby, 2021), this study explores how district- and school-level leaders use IS as an approach for addressing equity-focused problems of practice and the conditions that support or hinder their efforts.

The district that is the focus of this study and the larger system and state in which it was situated had made ongoing investments in both advancing equity in schools and using various CI approaches. Prior to the onset of the pandemic, central office administrators were reorganizing how they worked with principals by creating NICs focused on using IS to address existing performance challenges while developing leadership and organizational capacity for equity-focused improvement. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic and the “racial reckoning” that swept the country represented major shocks to the educational system that quickly shifted how students learned—with most students engaged in online learning—and changed educational priorities as educators tried to connect with their students from a distance (Code Switch, 2021; Voulgarides and DeMatthews, 2023). Although the pandemic shifted the challenges the district faced, they were able to leverage the principal networks to address new challenges facing schools. In place of attending a traditional principals' meeting, central office administrators invited all principals to select one of three networks to join and met regularly. The district established three NICs to address each of the following equity-focused challenges: reducing chronic absenteeism (CA), strengthening culturally responsive-sustaining education (CRSE), and strengthening social-emotional learning (SEL). The challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic and the inequitable impact on low-income and Black, Latinx, and Indigenous communities have only heightened the urgency of engaging students in educational experiences to affirm their cultural identities, encourage their academic development, and support their social and emotional wellbeing (Muhammad, 2020; New York State Education Department, 2018).

I conducted a comparative case study of three NICs situated in the same community school district in NYCPS to understand the factors that supported and/or constrained how educational leaders applied IS structures, practices, and tools to address equity-focused problems of practice. I draw on sensemaking theory to understand how this process is shaped by their individual knowledge and beliefs, the context in which they work, and the reform messages they encounter (Stosich, 2016; Weick, 1995; Yurkofsky, 2022). Learning how educational leaders make sense of and enact ideas and processes from IS to address equity-focused problems of practice can help to provide insight into the gap between how scholars theorize about the potential for CI to be used as a strategy for advancing equity and how it is used in the field (Bonney et al., 2024; Bush-Mecenas, 2022; Mintrop and Zumpe, 2019).

Literature review

In the following sections, I review research on the intersection between CI approaches and leading equity-focused improvement and the affordances and challenges of using CI methods to advance equity. Then I describe how sensemaking theory serves as a tool to investigate how leaders' individual knowledge and beliefs, social interactions, and connections with reform messages inform their understanding and enactment of continuous improvement methods to address equity-focused problems of practice.

Equity-focused continuous improvement

Continuous improvement approaches are considered well-suited for addressing persistent, complex, and wicked (Rittel and Webber, 1973), or ill-defined, problems, such as those stemming from persistent and pervasive educational inequity (Hinnant-Crawford and Anderson, 2022). Further, scholars argue that continuous improvement methods are useful for addressing problems of inequity because they bring attention to addressing not only a particular problem but also dismantling the unjust system that contributes to the problem (Anderson et al., 2023; Eddy-Spicer and Gomez, 2022; Hinnant-Crawford, 2020). Yet, some scholars have expressed concern, arguing that the focus on incremental change common among CI approaches is a “mismatch” with the transformational change required to advance equity (Safir and Dugan, 2021). Hinnant-Crawford and Anderson (2022) argue that most improvement work has one of three main purposes: efficiency, efficacy, or justice; CI can be used to serve multiple purposes but does not guarantee a focus on equity or justice. While still nascent, research in the field suggests that these methods can be used to advance equity, but they may need to be adapted or include targeted support to maintain a focus on equity (Bush-Mecenas, 2022; Sandoval and Van Es, 2021; Valdez et al., 2020). Using CI methods to advance equity demands attention to both the focus for improvement (i.e., the problem of practice) and how the improvement process is carried out. This raises questions about the specific conditions that enable equity-focused CI to thrive. To address these questions, I first describe how Gutiérrez's (2012) framework for equity is used to define the range of improvement work that would be considered to be equity-focused in this study. Then I review research on the conditions that may support or hinder equity-focused CI.

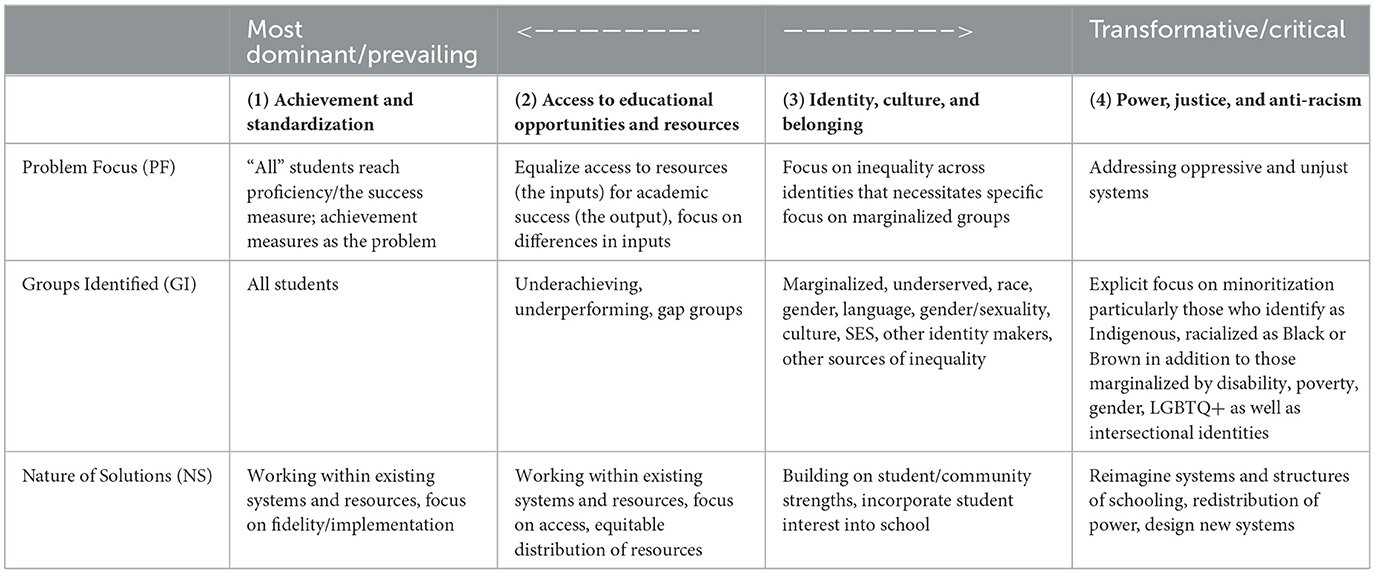

Equity-focused improvement aims to correct disparities in educational opportunities and outcomes among groups of students (Pollack and Zirkel, 2013). Yet, simply defining equity-focused improvement in terms of reducing opportunity gaps fails to address whether and how students' identities are affirmed by the curriculum and their schooling experiences more broadly and whether action is taken to transform schools in ways that better meet the needs and aims of the students, families, and communities they serve. In this study, I draw on Gutiérrez's (2012) framework for equity to understand the varied ways in which educational leaders conceptualize equity as they identify problems and design solutions as part of CI. Gutiérrez argues that equity consists of four dimensions: achievement (e.g., grades, test scores, graduation), access (e.g., opportunity to learn, enrollment in advanced coursework, and high-quality teachers), identity [e.g., how students see themselves, representation of students' identities in the curriculum (race, ability, religion, etc.)], and power (e.g., social transformation, opportunities to critique society, and voice in classrooms and schools). In the framework, the dimensions of achievement and access are described as the “dominant axis” because they reflect what the dominant group values and privileges; whereas identity and power represent the “critical axis” because they center students and focus on education as a humanizing practice that should reflect the priorities that each participant brings to it. Gutiérrez argues that all four dimensions are essential for advancing educational equity. However, research suggests that educational leaders are likely to define equity as achievement and access and, accordingly, focus primarily on addressing these aspects of equity (Roegman et al., 2022; Viano and Stosich, 2024). Reviewing research, the use of data, attending to relational elements of change, and support from coaches have emerged as essential factors that can support (or constrain) equity-focused CI.

Scholars argue that equity-focused leaders use data to support their work (e.g., Fergus, 2016; Pollack and Zirkel, 2013), including how they identify problems of practice and measure their progress in addressing them. Data use is central to CI, including the use of “practical measurement” that allows for rapid testing and evaluation of change ideas during inquiry cycles (Lewis, 2015); this focus on practical measurement, rather than an exclusive focus on well-validated measurement tools, could encourage practitioners to collect a wider range of data than is typical in schools. In practice, however, educators describe the focus on using multiple measures to adjust their work during cycles of inquiry to be impractical and burdensome (Bonney et al., 2024; Tichnor-Wagner et al., 2017). Despite these challenges, Bush-Mecenas (2022) found that collecting and using non-traditional data, such as collecting reports from teachers and students about the reason for disciplinary referrals rather than simply relying on data on the number of referrals, allows for more nuanced understanding of equity-focused problems as well as evaluating progress in addressing them. Irby's (2021) research on racial equity improvement suggests that data that reflects the perspectives of racially marginalized students and communities is essential for understanding problems and monitoring progress with attention to the influence of race and racism; he describes this as “Black and brown influential presence” to emphasize that their perspectives shape the improvement focus and process. This brings a racial equity focus to being “user-centered” in IS. While promising, this presents a challenge for leaders since data on more relational elements of school is both more challenging to collect and less likely to be part of existing data infrastructure in schools (Yurkofsky et al., 2020).

Scholars argue that CI approaches “underemphasize” the relational aspects of change, including how mindsets, identities, and beliefs influence practitioners' understanding of problems and the importance of trust among those involved in improvement work (Yurkofsky et al., 2020). Improvement in education involves changing the way educators work with students and each other; it is human-centered and social work that is shaped by our mindsets and beliefs, including implicit and explicit biases. Valdez et al. (2020) found that educators described CI methods alone as insufficient for addressing deeply rooted inequities because these methods did not address the mindsets of those engaged in improvement. Establishing norms prioritizing equity, including through developing and communicating a clear definition of equity, may act as an essential condition to supporting equity-focused CI (Bush-Mecenas, 2022); this is important since educators may define equity in ways that impedes their work, such as definitions of equity grounded in colorblindness. There is a large and growing body of research on equity-focused improvement that suggests that we must engage in difficult conversations about our beliefs about and experiences with race, class, language, gender, and other areas of difference to advance equity and disrupt oppressive beliefs and systems (Irby, 2021; Ishimaru and Galloway, 2021; Singleton, 2014). As part of this process, educational leaders can develop critical self-awareness, an awareness of their own values, beliefs, and dispositions when it comes to serving marginalized students and communities (Khalifa et al., 2016). Ishimaru and Galloway (2021) argue that the expectations for educational leaders to address inequities in students' educational opportunities and outcomes are beyond their existing capacity; thus, there has been growing demand for professional learning on how to engage in critical conversations about equity and shift mindsets and beliefs about historically marginalized students, families, and communities. Yet, these supports are not part of most CI approaches, and even with these supports, educators can struggle to move from discussion to action (Ishimaru and Galloway, 2021).

Research on CI suggests that coaching is a form of professional learning that is well-matched to CI when it is responsive to the needs of learners, such as those in an improvement network, and their goals (Anderson and Davis, 2024; Woulfin et al., 2023). Interviews with experienced “improvers” suggest that opportunities to practice CI approaches with support from a coach and a network of trusted colleagues can support educators' ability to engage in CI (Biag and Sherer, 2021). Expert coaching may be particularly important when using CI methods to advance equity. Aguilar (2013) argues that coaching can be leveraged to advance equity through a focus on directive coaching focused on changes in practice, reflective coaching focused on changes in ways of thinking and beliefs, and transformative coaching focused on systems change. In this way, coaching has the potential to address the practical, relational, and transformational elements of equity-focused improvement.

Making sense of equity-focused continuous improvement

Adopting CI approaches, such as IS, and using them to advance equity typically requires educational leaders to adopt new practices, tools, and mindsets. This study draws on sensemaking theory, grounded in cognitive and social psychology (e.g., Greeno, 1998; Weick, 1995), to understand and explain how people make meaning of their experiences with equity-focused CI. Researchers in education argue that sensemaking theory provides a useful lens for understanding how educators come to understand and enact reforms because it brings attention to how this process is influenced by their individual knowledge and beliefs, social interactions, and connections to reform messages (Coburn, 2004; Hodge and Stosich, 2022; Stosich, 2016; Yurkofsky, 2022). Since sensemaking is often triggered by ambiguous stimuli that raise questions about how to respond (Weick and Sutcliffe, 2015), it is well-suited to analyzing educational leaders' understanding of how to use CI methods to advance equity, two related yet potentially conflicting goals.

Sensemaking theory takes into account both the individual factors that influence human behavior as well as the contextual factors that influence the dynamic interplay between interpretation and action (Weick et al., 2005). Educators make sense of CI reforms through the lens of their existing knowledge and beliefs, “supplementing” rather than “supplanting” existing knowledge and practice (Cohen and Weiss, 1993, p. 227). Adopting CI approaches represents a challenge for educational leaders because it requires “developing new understandings of familiar ideas” (Spillane, 2004, p. 157), such as using data for school improvement rather than accountability. Tichnor-Wagner et al. (2017) found that educators viewed PDSA cycles, a method used in IS and related CI approaches, as similar to other reflective practices they had used, which supported their openness to adopting the new approach; however, the “we do this already” mindset also made deeper change more challenging. Similarly, Mintrop and Zumpe (2019) found that educational leaders adopted CI methods in ways that conformed to existing beliefs despite the provision of ongoing support for professional learning in their graduate program. When educational leaders have a more trusting relationship with district leaders, they may respond more productively to district-led CI reforms (Yurkofsky, 2022); they may be more likely to seek out support, share challenges openly, and use CI in ways that advanced internal school priorities than educational leaders with less trusting relationships with district leaders, who are more likely to respond superficially to district-led CI initiatives. These findings highlight the dynamic nature of sensemaking among individuals and groups that shape how CI methods are understood and enacted.

Continuous improvement methods require collaborative engagement in cycles of inquiry (LeMahieu et al., 2017); thus, they require shifting not only the work of individuals, such as educational leaders, who adopt these methods but also those with whom they work. Coburn and Stein (2006) describe reform “implementation as a process of learning that involves gradual transformation of practice via the ongoing negotiation of meaning” (p. 26). As educational leaders make sense of CI methods, this process is shaped by organizational structures and culture, including structures for collaboration, norms for data use, and district definitions of equity (Roegman et al., 2022). Research on teacher learning and instructional change suggests that intensive and ongoing collaboration with colleagues can serve as an essential opportunity for learning how to translate abstract reform ideas into specific changes in practice (Stosich, 2016). This suggests that NICs may serve as a promising structure for collaborative learning about and enactment of CI methods. However, opportunities for collective sensemaking do not guarantee that educators will take up ideas as intended. Research on how educational leaders use data for equity-focused improvement suggests that leaders are likely to draw on existing data sources (e.g., test scores, graduation rates, and attendance) that define student success and school improvement narrowly in terms of achievement and access (Roegman et al., 2022). A narrow focus on more dominant conceptualizations of equity is reinforced by state and federal accountability policy (Gutiérrez, 2012). This is concerning since a focus on access and achievement without attention to how the larger system contributes to educational opportunities and outcomes can lead to deficit thinking that blames underserved students (Datnow and Park, 2018). While scholars argue that CI methods can be used to recognize and redesign unjust systems that contribute to problems of inequity (Anderson et al., 2023; Eddy-Spicer and Gomez, 2022), doing so requires educational leaders to work in ways that depart substantially from the improvement work that is typical in schools and districts.

Methods

I conducted an exploratory comparative case study of three NICs nested in the same community school district to understand how educational leaders understand and enact a CI method, IS, to enhance equity. I draw on sensemaking theory to answer the following question: What factors support or constrain educational leaders' use of improvement science to advance equity?

As an “improvement researcher,” identifying the focus for the study was a collaborative process of negotiation with my district partners (Russell and Penuel, 2022). I established a research-practice partnership (RPP) with central office administrators in this district with the goal of advancing knowledge and identifying specific district structures, practices, and conditions that could strengthen equity-focused leadership for CI and, ultimately, improve students' learning opportunities and outcomes. RPPs are sustained collaborations between practitioners and researchers that aim to address specific problems of practice and advance solutions to support improvements in the focus schools and districts as well as the broader educational system (Coburn and Penuel, 2016). This collaboration built on an established university-district collaboration focused on a shared problem of practice: school and district leaders varied widely in their capacity to foster continuous school improvement that serves all children well. Given the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, it was essential to limit the burden posed by the study and maximize the benefits to the district, schools, and students.

Central office administrators in this study aimed to address the following problem of practice: How can district leaders use IS in principal networks to address equity-focused problems of practice? The NICs focused on addressing three district improvement foci: (1) decreasing chronic absenteeism and strengthening engagement, (2) creating more inclusive and culturally responsive-sustaining curriculum and assessments, and (3) developing more welcoming and affirming school environments that support students' social-emotional learning. In a related study, we examined how the use of IS influenced how educators understood equity; while not the focus of the study, we found evidence that factors beyond IS played an important role in influencing how they understood and enacted equity-focused improvement, including such factors as individuals' knowledge, prior professional learning, and district context (Viano and Stosich, 2024). Thus, this study explores the broader factors that shape how they use IS to advance equity.

Study context

The community school district in which this study takes place represents a critical case (Patton, 2015) for examining equity-focused CI because current and previous central office administrators had a strong commitment to equity and had made sustained investments in developing structures, such as equity teams, and capabilities for equity-focused leadership. Specifically, the district had established district- and school-level equity teams, developed leaders' “equity lens” through training focused on leading conversations about race and implicit bias (e.g., Courageous Conversations, Beyond Diversity), invested in developing school and district leaders' ability to set equity-based goals for improvement, conducted equity audits, and developed culturally responsive-sustaining curriculum and assessments. Additionally, New York state was a supportive policy context for equity-focused improvement and had an instructional framework in place for culturally responsive-sustaining education (CRSE).

The district was acutely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic; the community had one of the highest death rates from the COVID-19 pandemic (by zipcode) in NYC. Further, the study took place during Spring 2021- Summer 2022, a time of great instability and difficulty as students transitioned from fully online or hybrid learning models (2020–2021) to fully in-person learning models (2021–2022), educators learned to work with colleagues in-person and online, new variants of COVID-19 caused spikes in infections, and schools faced high numbers of absences of both students and staff. The district had been identified as a “target district” under the Every Student Succeeds Act (2015) due to sustained low performance and high levels of chronic absenteeism. These challenges shifted and some became more severe during the pandemic. For example, when the district transitioned to online learning, racial disproportionality in suspensions was no longer a concern; however, chronic absenteeism increased sharply, and the root causes related to absenteeism changed.

Sample

The community school district that is the focus of the study is a relatively large urban district within the larger NYCPS system and serves ~35,000 students in 45 schools. Approximately 83% of students identified as economically disadvantaged, 22% as students with disabilities, 45% of students identify as Hispanic, 35% Black, 9% White, and 9% Asian. At the time of this study, central office administrators chose to use IS to create what one described as “action-oriented” principal networks to address critical equity issues. In place of attending a traditional principals' meeting, central office administrators invited all principals to select one of the three networks (i.e., CA, CRSE, and SEL) to join and met regularly. In 2020–2021 NICs met virtually weekly or bi-weekly. When all students returned to in-person learning in 2021–2022, NICs met monthly either virtually or in-person.

All 45 principals were expected to participate in one of the three NICs. While the primary focus of NICs was on principals, some assistant principals and a small number of other school leaders (e.g., teacher leaders, school counselors) also attended the meetings. Thus, I refer to the NIC participants as district and school leaders. All participants in the three NICs were invited to participate in the study as potential research subjects, including individuals who participated in, planned, or facilitated NIC meetings. The district had a history of seeking principal input and involvement when designing district professional learning, and both district and school leaders contributed to the design and facilitation of each of the NICs. Each of the NICs was facilitated by one or more principals or assistant principals (APs) and two or more central office administrators.

Data collection and analysis

Data was collected from Spring 2021 to Summer 2022. Data collection focused on semi-structured interviews with participants and observations of NIC meetings, planning meetings with district and school leaders facilitating these NICs, and document collection. I conducted 1-h, semi-structured interviews with educational leaders in the NICs focused on how they understood and enacted IS to advance equity; how their knowledge, beliefs, and social context influenced this sensemaking process; and the factors that supported or constrained their work. Observation data focused on meetings with all three NICs as well as more extensive observations of the CRSE NIC. Typically all NICs met at the same time, so I selected one NIC for more in-depth observation. Observation data focused on the stated or written purpose of the meeting, the focus of the meeting, the use of IS practices or tools, any evidence of impact on the focus areas reported, and factors that seemed to support or constrain the work of the NICs. Additionally, I collected and reviewed any documents or improvement artifacts (e.g., fishbone, driver diagram, and planning documents) shared during NIC meetings and planning meetings to understand how the NICs were defining their focus problems, and using IS practices and tools. In total, I conducted 12 interviews with leaders across all three NICs, including four district leaders (one CA, one CRSE, two SEL) and eight school leaders (two CA, three CRSE, three SEL). I conducted ~16.75 h of NIC meeting observations and 7.33 h of facilitator planning sessions. Meetings ranged from 30 min to 2.5 h, but most NIC meetings were 1½ h and most planning meetings were 1 h.

I used NVivo qualitative data analysis software to engage in an iterative analysis process that included applying deductive and inductive codes and identifying emergent themes (Yin, 2017). I applied deductive codes related to how individual knowledge and beliefs, social context, and reform messages influenced the sensemaking process (Stosich, 2016; Yurkofsky, 2022), the use of IS practices and tools (Bryk et al., 2015), and how participants conceptualized equity (Gutiérrez, 2012). I coded all data using a framework for equity-focused CI in NICs advanced in a related study (Viano and Stosich, 2024), which was adapted from Gutiérrez's (2012) equity framework and Farrell et al.'s (2023) application of this framework to the work of RPPs, a collaborative approach to improvement related to key features of NICs (see Table 1). This framework was used to identify whether and how participants defined equity as it related to three important elements of the CI approach: problem focus, groups identified as the focus for improvement work, and the nature of solutions. I first coded all interviews; then I coded observations notes and reviewed documents using the same analytical framework, with a focus on supporting or contradicting my interpretations of the interview data. This approach allowed for a systematic process of categorizing the data through reduction, organization, and connection. Member checks were conducted throughout data collection via informal conversations and email communication with participants.

Findings

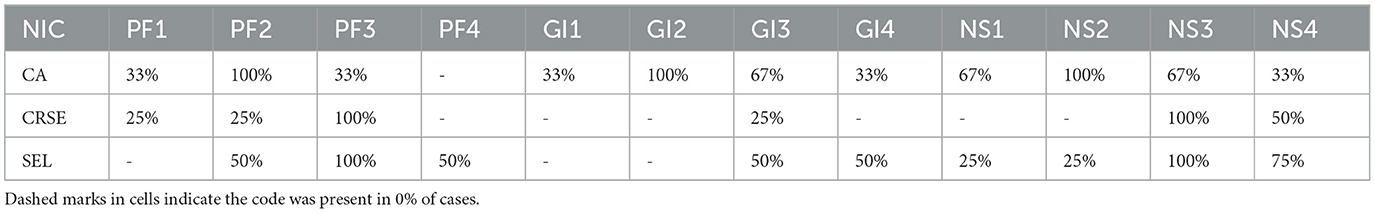

Findings from the study provide strong evidence that educational leaders attended to equity as they used improvement science as an approach to continuous improvement. Participant interviews, observations of NIC meetings and planning meetings, and documents developed and shared during NIC meetings reflected attention to addressing important equity issues related to each of the focus areas of the NICs. These included but were not limited to discussions during NIC meetings of disproportionately high rates of chronic absenteeism among students with special needs (CA NIC), strategies for increasing students' sense of social belonging at school among English learners (SEL NIC), and the need for greater attention to Black joy in the curriculum (CRSE NIC). As illustrated in Table 2, educational leaders in all three NICs defined their work in ways that reflected all four dimensions of equity (Gutiérrez, 2012): achievement, access, identity, and power. As they described their problem focus (PF), the groups identified (GI) as the focus of their improvement work, and the nature of their solutions (NS), they described their use of improvement science to advance equity in ways that adhered to more dominant/prevailing (e.g., achievement, access) and critical/transformative (e.g., identity, power) conceptualizations.

This study aims to identify the specific factors that support and/or constrain efforts to leverage improvement science as an approach for advancing equity, including those that encourage (of discourage) a focus on more dominant or critical dimensions of equity. As educational leaders made sense of IS as an approach for advancing equity-focused improvement, their experiences were shaped by their personal commitments to advancing equity, their district context, the broader policy environment, and their use of IS practices and tools. I identified four key factors that shaped this process: a sustained district equity focus, the use of PDSA cycles, data use, and NIC facilitation. In the following sections, I describe each of these factors and how they supported and/or constrained educational leaders' attention to equity as they engaged in the improvement science process.

Sustained district equity focus creates supportive conditions for equity-focused continuous improvement

The district that is the focus of this study had made deep investments in equity-focused improvement for about 6 years under the current and prior superintendent. This included establishing equity-focused structures (i.e., district- and school-level equity teams), hiring and promotion of strong equity leaders, and investments in equity-focused professional learning. As one principal remarked, “I think our district was probably one of the first districts to really push hard on the equity initiatives.” Further, district administrators leveraged broader state and national policy to advance their equity work. As one district leader explained, the “racial awakening in 2020 with George Floyd” and the pandemic led them to “reset” their equity priorities as a district. In collaboration with principals, district leaders identified three equity-focused problems of practice that served as the focus of each of the NICs: reducing chronic absenteeism (CA), strengthening culturally responsive-sustaining education (CRSE), and strengthening social emotional learning (SEL) through establishing more affirming and inclusive school environments. The district's attention to issues of equity as well as the strong commitment to equity among many educational leaders in the NICs created supportive conditions for using IS as a process for advancing equity.

The district had invested in developing equity “infrastructure” that was leveraged to support the NICs as they used improvement science to advance their equity goals, including district- and school-level equity teams and equity “incubator” schools. School leaders described having an equity team in place in their school; further, most school and district leaders interviewed had served on the district's equity team, which was composed of diverse stakeholders including school and district administrators, teachers, other school staff, family members, and students. The superintendent described the goal of establishing the NICs as involving all principals in the district's equity work. In this way, the superintendent leveraged existing norms for centering equity in their improvement work and structures, such as equity teams, to support school leaders in translating learning in the NICs into changes in practice at their schools. As a district leader in the CRSE NIC explained, principals and other leaders participating in the NICs were expected to take what they had learned in the NIC and go through “the same process with their team,” typically their school equity team. Additionally, the district had established “equity incubator” schools that served as models and received ongoing support to deepen their work from expert consultants. These schools were often called on during NIC meetings to present examples, such as CRSE curriculum units, to support the work of other schools.

The district seemed to attract, elevate, and develop equity-focused leaders; thus, many school and district leaders brought high levels of commitment, experience, and capabilities in leading for equity to their use of IS in the NICs. Many leaders described deep personal commitments to leading for equity and seeking out opportunities to develop their knowledge and skills as equity leaders beyond those offered by the community school district. Members of the NICs described how the current and prior superintendent elevated teachers and school leaders to higher levels of leadership who were recognized for their success in leading equity-focused improvement. For example, a woman who served as an assistant principal at an equity incubator school in the 1st year of the NIC was hired as the principal of a school that lacked a strong equity focus in year 2. She described her passion for leading for equity as stemming from her upbringing in a “very proud” Black family and described developing her capabilities as an equity leader through participating in district-led professional learning and seeking out additional equity-focused learning opportunities in NYCPS. Similarly, another school leader in the district who played a leadership role in her equity team as a teacher described being encouraged by the superintendent to pursue school building leadership. All school and district leaders interviewed described engaging in previous district professional learning related to equity. During interviews and observations, it was evident that leaders drew on prior professional learning as they engaged in difficult conversations about race, racism, and identity; set equity-focused aims for their improvement work; and developed culturally responsive-sustaining curriculum and assessments. For example, leaders described identifying areas of racial and linguistic disproportionality as they set their aims for improvement, a focus of prior professional learning on setting equity goals. They began almost every NIC meeting observed with the CCAR Protocol and often began with opportunities for leaders to connect around how their own culture and identity shaped how they responded to a recent event, such as the racially motivated mass shooting in Buffalo, New York. The Courageous Conversations About Race (CCAR) Protocol (Singleton, 2014) emphasizes supportive conditions for conversations about race, racism, and privilege and a focus on understanding one another's perspectives and beliefs. Much of the district's prior professional learning had focused on supporting school leaders, teachers, and others in engaging in difficult conversations to disrupt mindsets and beliefs about race, language, gender, and other areas of difference that can hinder efforts to advance equity.

District leaders argued that their earlier equity work had prepared them to move from discussions on issues of equity to a focus on changing practice. One district leader explained that they had done “the mindset work,” so now the focus was on

really impacting instruction…Then, thinking about the groups [NICs], instead of just reading articles or reading books together, how do we ground it in work that's going to be aligned to the classroom? For me, how does the equity work now impact classrooms after all this time?

Similarly, another district leader reflected, “I'm one who thinks that we get a little bit lost in the weeds when we just rely on [addressing] staff mindsets, because that's almost forever unfinished work.” This reflected the belief among leaders in the study that attention to mindsets and beliefs was important yet insufficient for advancing equity. In NIC meetings, they seemed to combine existing district practices that addressed mindsets and beliefs (i.e., CCAR Protocol) with IS processes that encouraged action (i.e., PDSA cycle, driver diagram).

PDSA cycles hold leaders accountable for taking action

Interviews and observations suggest that the use IS supported leaders in taking action to advance equity. District and school leaders in all three NICs described the use of the Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) cycles as helpful for sustaining attention to understanding and addressing critical equity issues. In interviews, they described this process as helpful for taking large and complex challenges and identifying smaller actions they could take to address these challenges, even during the very difficult and shifting environment created by the pandemic. One district leader in the SEL NIC described the PDSA cycle as “helpful especially with SEL being such an abstract, broad thing.” A school leader in the CA NIC explained that the PDSA cycle focused leaders on taking small actions in a short period of time and building on or adjusting their actions based on evidence of impact:

We had to use a protocol, a Plan-Do-Act-Study. You had to come back with your deliverable. …It was like, okay, in 1 week. It was also really small. The idea was, “What are small things you can do? We know we're in the pandemic.” So it felt super doable. And then what was your impact? It felt like I can just do this little thing and move the needle a lot. Or if I don't move it, switch what I'm doing… It was really helpful and productive to think about small moves that leaders make that incrementally move the needle. But over time, those small pushes add up to a lot.

This leader and others described the use of the PDSA cycle as distinct from their other PD experiences which had little attention to or accountability for implementing what was learned. This school leader described “a marked increase in attendance” after introducing two changes; they redesigned their existing advisory program to leverage strong student relationships with a paraprofessional “who students love” and launched a Saturday school that included one-on-one support from a “mentor” teacher with whom students had a strong relationship. These solutions reflect a focus on equity in terms of increasing students' sense of belonging, through attention to staff-student relationships, and shifting power by redesigning school structures, including the days when instructional support is offered, in response to students' expressed needs.

Leaders explained that PDSA cycles held them “accountable” for taking action to address their improvement focus. A district leader in the CRSE NIC explained that there was an expectation for school leaders to be leading IS work back at their schools, sharing their work by filling out a PDSA template, and receiving feedback from NIC facilitators. A school leader in the CRSE NIC described the focus on the PDSA cycle and checking in with members of the NIC at each step of the cycle as creating a sense of accountability for taking action to strengthen CRSE:

Knowing that the PDSA cycle had to be 6 weeks and knowing that when we went back to the group, we had to be accountable for—“Were we able to do everything in 6 weeks?” Having that conversation with other colleagues made me accountable.

This school leader described developing “Cultivating Genius Cohorts,” groups of teachers who worked to develop culturally responsive-sustaining morning meetings using Muhammad's (2020) HILL Model, a focus on advancing equity in terms of how students' culture and identity is reflected and affirmed in their educational experiences. This leader, who identified as a Black woman, explained that the previous principal, according to teachers, “didn't feel comfortable doing the work because she was a White woman,” so they had done a book study on Gholdy Muhammad but had not taken steps to enact CRSE practices. The focus on action in the PDSA cycle combined with the school leader's personal passion and professional competency seemed to support her in bringing a stronger equity focus to the school's improvement work. Notably, leaders described this focus on action as distinct from earlier equity work in the district, which was more focused on addressing mindsets and beliefs, including working in racial affinity groups, CRSE book studies, and training on the CCAR Protocol (Singleton, 2014). One school leader described how her principal had been resistant to earlier district-led equity work, particularly around discussions of race, but the use of the PDSA cycle supported her in working with her principal to take action to advance equity even though her heart and mind were “not there” yet:

Making them [all principals] join the team [NICs] and being part of the teams as part of their day at the principal's meeting, I think was a great move for the superintendent. …My principal, she was not there. She just, her heart, her mind was not there, but she was able to do the work because it had to be done, knowing that there was an accountability, knowing it was an artifact to bring, knowing that there was a PDSA cycle that we had to present that made them kind of do the work. And you can work through your internal issues along the way, but the kids can't wait for people's hearts and minds to change.

According to this leader, the focus on action was important for making equity-focused improvement in schools, and productive mindsets could be developed as part of this work rather than as a prerequisite for action.

Findings suggest that leaders in all three NICs took action in their schools to address the focus areas. One district leader reflected on the actions taken in the three NICs and the evidence of improvement, including the development of CRSE-aligned curriculum, the use of CRSE instructional practices, higher levels of understanding of Muhammad's (2020) HILL Model, and improved attendance:

I know we designed eight exemplar units with our cultivating genius designers. We used some of those during summer school. Some schools have utilized them. I've seen evidence that a lot of teachers are having a good understanding of the HILL Model and of CRSE. I see that when I'm visiting schools. …I'm seeing that [improvement] in attendance. …We were one of the lowest performing districts in attendance. We are the highest as a result of the systems and structures that we put together, as well as the focus on the equity work.

All school leaders interviewed described taking action to address the NIC focus area in which they participated, and these actions reflected a wide range of approaches to advancing equity in terms of students' access to school, students' achievement, affirming their culture, identity, and belonging, and attending to issues of power by redesigning school systems and structures based on the needs of students. While leaders described the focus on action encouraged by the PDSA cycle to encourage and create a sense of accountability for taking action to address the focus problems, the district's previous and ongoing attention to supporting leaders' equity mindsets and beliefs seemed to support attention to equity-focused action more specifically.

The use of data created opportunities and challenges for advancing transformative equity work

The use of data was central to the work of these NICs, including as part of identifying a problem of practice and understanding its root causes, designing a solution to address the problem, and measuring progress and adjusting the approach through iterative cycles of inquiry. In the early phases of using IS, the processes for using data to understand the problem and setting the aim seemed to encourage a focus on equity as an issue of improving access and achievement, a focus on more dominant dimensions of equity. However, the focus on the “user,” particularly students, encouraged members of the CA NIC and SEL NIC to collect data directly from students about how they experienced the problem and the solutions they valued, which encouraged educational leaders to attend to more critical dimensions of equity. The SEL NIC members described the greatest attention to the critical dimensions of equity and described student voice as encouraging this focus; however, collecting new data on students' perceptions of the school environment delayed action in addressing the problem. After 1 year, the NIC focused on reducing chronic absenteeism identified a reduction in chronic absenteeism and an improvement in overall attendance, on average, in participating schools and did so using existing attendance measures that were regularly collected. By contrast, the NICs focused on CRSE and SEL had taken action to address these areas but were left questioning how to measure their progress. I briefly describe the use of data in each NIC, and the opportunities and challenges for leveraging data to support more transformative equity work as part of IS.

The CA NIC was established in response to high rates of chronic absenteeism and low rates of overall attendance, an issue of inequitable access to education and a focus for federally required reporting. Analyzing attendance data, the NIC members determined the following “aim” or goal for improvement for each participating school: “recover six students whose attendance was at 90% in the 19–20 year but has since dropped below.” As one leader explained, “We wanted to focus on…, and we did this both years, kids who once had good attendance but for whatever reason right now do not.” This aim seemed to reflect a focus on incremental change and quick wins. At each participating school, they identified six focus students, conducted empathy interviews, and used what they learned from students about the problem to design and implement change ideas. One school leader explained that the focus on student voice as part of conducting empathy interviews enhanced the extent to which a focus on equity was part of the improvement process. Understanding the problem from the perspective of the “user,” students, and designing solutions based on student input seemed to encourage more transformative solutions. Specifically, two school leaders described designing solutions that attended to issues of culture and belonging and one described reimagining how school was offered by shifting power to students. For example, a school leader described launching “Fun Fridays,” clubs focused on students' interests that met during the school day with the lowest attendance. This leader described the improvements in attendance data he witnessed because of this change.

Members of the SEL NIC often described a connection between the high rates of chronic absenteeism and the need to create spaces for online and in person learning where students wanted to be, spaces where they were supported and affirmed. The NIC established the following aim: “develo[p] spaces that welcome 100% of our most vulnerable students in order to guarantee them the safety to learn in the comfort of their own skin.” A district leader explained how they arrived at their focus on “vulnerable” students, an explicit focus on minoritization:

When we looked at the qualitative and quantitative data points that each school administered, we found that our most vulnerable students looked different in each community, whether that was our multilingual learners, our LGBTQI students. We needed to make sure that…our most vulnerable students had the environment where they had safety to learn in their own skin.

While this leader spoke vaguely about using various “data points” to identify this aim for improvement, the lack of data on students' sense of belonging and the extent to which schools were inclusive and affirming led the SEL NIC to spend much of their 1st year developing student surveys to better understand the “user” perspective. One school leader explained that the experience “reinforced [his] belief in improvement science as a real lever to have change…especially in areas that are hard to measure” but that this process requires “patience.”

Yet, another school leader in the NIC questioned the focus on developing their own student surveys: “For me, that's the frustration. We're spending all this time creating stuff that researchers have already designed.” According to this leader, the focus on designing surveys was a way to move the work “intentionally really slow” and avoid racial discomfort. This leader was the only NIC member interviewed to described working to improve support for a particular “vulnerable” population; student survey data led him to identify and work to address the following problem: the “EL [English learner] student population was the most disconnected, particularly during remote learning.” For the SEL NIC, their focus on collaboratively designing student surveys delayed action to address the problem, yet school and district leaders in the NIC described advancing transformative solutions. Specifically, they described redesigning the school based on the needs and interests of students and community members, including: installing laundry in their building, creating a community pantry, launching clubs based on student interests, and creating opportunities for student leadership positions that reflected students' views of leadership rather than more traditional structures that reflected what one school leader described as the default culture of “Whiteness.”

School and district leaders in the CRSE NIC described identifying the problem of the lack of culturally responsive curriculum and instruction based on observations of classroom practice but initially lacked a systematic approach to collecting data on the problem or measuring their progress. A district leader described how they identified the problem:

In a nutshell, it was really this idea that most of our schools did not have a culturally responsive curriculum, at least in literacy, let alone in the other content areas. …We do lots of class visits. Even during remote instruction, I was visiting classrooms every day. …It was evident across most, not all,… schools that the types of texts we were putting in front of children and even the pedagogical practices were not culturally responsive.

Based on their understanding of the problem, the CRSE NIC set the following aim for their work: “By June of 2021, 100% of [District] schools will increase their staff's proficiency in CRSE practices by building cultural competence, familiarity, and awareness in order to provide students with access to curriculum that is engaging, rigorous, and culturally responsive.” To do this, the focus was on providing professional development on Muhammad's (2020) HILL Model. Progress monitoring in the CRSE NIC focused on the impact on adults (e.g., number of units planned using the HILL Model, number of educators who participated in CRSE professional learning) rather than the impact on students. All leaders in the CRSE NIC interviewed described the problem focus and solution design in ways that reflected a focus on culture and identity. However, only one school leader named a particular student group, English learners, who were the focus for strengthening the extent to which curriculum and instruction was culturally responsive-sustaining. Without data focused on the “user,” students, educators seemed to focus on CRSE practices approaches broadly rather than in response to the needs or interests of particular groups of students.

NIC facilitators encouraged attention to both equity and improvement science

The focus on advancing equity through the use of IS was supported by teams of facilitators for each NIC who brought expertise in IS, equity leadership, or both areas. However, attention to the fuller IS process diminished in the 2nd year of the NICs when the NIC facilitators changed; these facilitators had lower levels of expertise in IS and limited time to support NIC members.

In the 1st year of the NICs, each of the three NICs was facilitated by one or two principals who were identified as strong equity leaders and two district leaders, including at least one district-level administrator with expertise and training in supporting the use of IS. Additionally, other district leaders with expertise in equity leadership sometimes attended or provided training to support the work of the NICs. A school leader described her experience in the CRSE NIC as being “around all these people that I admire” and “fangirling” over the “dynamic” equity leaders involved during the 1st year of the NIC; in the 2nd year she was asked to become a facilitator of the NIC. A district leader described the principals who facilitated the NICs in the 1st year as “rockstar” principals with “political clout” and “experience” in leading equity-focused improvement. In fact, two of the three school leaders involved in facilitating the NICs in the 1st year were elevated to roles as executive central office administers in neighboring community school districts at the end of the year.

The district and school leaders who facilitated the NICs were observed and described in interviews as encouraging attention to a critical equity focus. For example, one school leader described a “key moment” in defining the problem of practice in the SEL NIC as supported by the district facilitator who

brought out a quote, I think it's Dena Simmons, around being comfortable in your own skin. …It focused us on the student experience and what were the aspects of what adults had to do in order to have every student be comfortable in their own skin. And I think that moment led to the theory of action, led to the aim statement for the improvement science work that happened.

According to this school leader, the SEL NIC initially had found it difficult to develop a shared definition of the problem, but this quote helped to reflect the common challenge they faced in their different schools. Further, the quote encouraged attention to the unique experiences of marginalized students and a focus on redesigning the school environment to be more inclusive and affirming, a focus on identity, culture, and belonging. During NIC meetings, facilitators were observed modeling the use of the CCAR compass to engage in interracial dialogue about the events shaping their own and their students' lives, encouraging greater attention to issues of equity, and elevating examples from schools that reflected more critical equity work.

To support improvement systemwide, NYCPS had established a team of district-level administrators who were trained to support the use of IS and led professional learning in various community school districts. The role of these district-level administrators was to plan professional learning and provide support for continuous improvement in community school districts. In the 1st year of the NICs, each network was facilitated by one of these district administrators, and they were often referred to as IS “experts” by those involved in the NICs. A district leader in the SEL NIC explained that in their 1st year “we were beginning the improvement science work. We needed to partner with the [NYCPS district-level administrators] because they were seen as the experts with the improvement science.” During NIC meetings observed, these district administrators would lead the use of IS tools and processes, such as defining the problem of practice or developing a fishbone diagram. A school leader in the SEL NIC described these facilitators as “masterful” with IS: “[T]hey were brilliant in their understanding of the concepts and to lead people through it, and their level of patience with it.” Additionally, many of these district leaders were also recognized as strong equity leaders, and they reinforced attention to equity throughout the IS process. For instance, a district leader who facilitated the CA NIC described her role as “to go to the meetings and ensure that every single theory of action that we produced in all of our problems of practice had some kind of equity component,” which included supporting leaders in stopping “blaming kids” and instead recognizing “where do we see ourselves show up as part of the problem, as part of our equity work.” She explained that she had a “strong equity focus,” which she had developed through her work in education and through her PhD focused on Black women's leadership strategies.

Attention to the full IS process and tools diminished in the 2nd year of the NICs when NYCPS disbanded the group of district administrators tasked with supporting the use of IS in community school districts. In the 2nd year of the NICs, teams of three to four school leaders with the support of two district leaders took over each of the three NICs. There had been a great deal of movement in terms of district administrators' roles and the leadership of participating schools. While all school and district leaders facilitating the NICs had experience with IS from the earlier NIC work as well as previous efforts in the district, none described themselves as having deep expertise in using IS. By contrast, they described years of leading equity work in their schools and deep personal commitments to leading for equity. Nevertheless, these leaders were much less experienced than the school leaders who facilitated the NICs in the 1st year. In fact, several were in their 1st year as principal and some were assistant principals.

The school and district administrators facilitating the NICs in year 2 had many competing responsibilities that made planning and leading the NIC meetings challenging. Further, school leaders took a greater role in planning and leading NIC meetings in year 2, but they did not provide support or accountability to members of the NICs outside of the network meetings, which had been the role of district-level administrators in year one. As one school leader facilitating the CRSE NIC explained, the district leaders who had facilitated the NICs in the 1st year had both “a wealth of knowledge and resources” related to IS as well as “time, and their presence [was] missed.” A school leader facilitating the CA NIC described “pushback” from other leaders in carrying out the IS process during the 2nd year of the NIC: “When it came to do the PDSA, a lot of people just were like, ‘I'm not doing that.”' Consequently they “had the plan…but not do, study, act.” In essence, school leaders in the NICs discussed their plans for taking action to address each of the problems of practice, but there was less accountability and support for following through with these plans and adjusting their approach based on evidence of their impact on the problem. This is concerning since it suggests that the NICs were less focused on testing and refining their improvement work through disciplined inquiry in the 2nd year. Despite the community school district's multiple investments in supporting leaders' use of IS as a strategy for continuous improvement, the school and district leaders facilitating the NICs struggled to maintain focus on IS processes without support and accountability from highly trained district leaders dedicated to this work.

Discussion

In this study, I describe the factors that supported and/or constrained educational leaders in three NICs in the same community school district in using IS as an approach to advancing equity-focused improvement, contributing to a small but growing body of research exploring how educators in the field use CI approaches to advance equity (e.g., Bush-Mecenas, 2022; Valdez et al., 2020). As educational leaders in this study made sense of IS as a process to advance equity, they did so through the lens of their existing knowledge and beliefs and in response to reform tools and messages (Cohen and Weiss, 1993; Weick, 1995). I found that the district's sustained investments in advancing equity fostered beliefs, mindsets, and leadership capacity among school and district leaders that supported them in working toward equity-focused goals in each NIC. My findings suggest that the focus on the PDSA cycle as part of IS supported educational leaders in moving from discussions of equity to taking action to advance transformative solutions. According to school and district leaders, the PDSA cycle held them accountable for making change in their schools even amid the challenging and shifting environment created by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, their use of data, another essential element of CI, varied in whether it supported or constrained attention to equity, particularly more transformative equity work. Facilitators played an essential role in supporting educational leaders in the NICs in centering equity in their improvement work, and leaders seemed less likely to take action in their schools when support and accountability from facilitators diminished in the 2nd year of the NICs. While the district had fostered strong norms, beliefs, and practices for advancing equity, the IS process represented a new way of working and seemed to require high levels of support for leaders to sustain attention to and carry out the improvement process in their schools.

Scholars argue that educators must engage in difficult conversations about their beliefs about and experiences with race, class, language, gender, and other areas of difference to advance equity and disrupt oppressive beliefs and systems (Irby, 2021; Singleton, 2014); nonetheless, a focus on shifting mindsets and beliefs “first” before taking action can inhibit organizational change since the work of changing “hearts and minds” is never done (Ishimaru and Galloway, 2021). In this study, the district's early and ongoing investments supported educational leaders in attending to the relational elements (e.g., values, beliefs, identity, connectivity) of change that fall “below the green line” (Wheatley and Dalmau, 1983), an essential dimension of improvement work that receives insufficient attention in most CI approaches (Yurkofsky et al., 2020). While previous research suggests that educators may need to adapt CI approaches to maintain a focus on equity (Bush-Mecenas, 2022; Valdez et al., 2020), findings from this study indicate that additional, complementary supports focused developing educators' critical self-awareness (Khalifa et al., 2016) and challenging deeply held beliefs about people, practices, and systems are likely necessary for advancing equity as part of CI approaches, particularly more transformative equity work.

Data use is a central part of CI approaches as well equity-focused leadership (Fergus, 2016; Hinnant-Crawford, 2020; Roegman et al., 2022). The focus on using data as part of IS encouraged attention to equity in terms of both the focus of their improvement work as well as the process. While the use of data as part of IS encouraged attention to more dominant aspects of equity initially (e.g., access), a focus on the “user,” students, encouraged increased attention to more transformational dimensions of equity in two of the three NICs. In essence, data from students acted as new stimuli (Weick and Sutcliffe, 2015) that challenged leaders' assumptions about the nature of the problem and potential solutions. Specifically, school leaders in the SEL and CA NIC surveyed students and conducted empathy interviews to better understand both how they experienced the focus problem and the solutions they valued. Hinnant-Crawford (2020) argues that attention to who is involved and who is impacted is essential for using improvement science to advance equity. Involving students in both defining the focus problem and the nature of solutions encouraged a more equitable process by elevating student voice and led to transformative solutions that involved reimagining systems and structures of schooling in ways that were responsive to the needs and interests of students. Yet, leaders may find collecting and using data to be burdensome (Bonney et al., 2024; Tichnor-Wagner et al., 2017), particularly non-traditional data that attends to the more relational elements of change (Yurkofsky et al., 2020). Nevertheless, this process is essential for both understanding and addressing equity-focused problems (Bush-Mecenas, 2022; Irby, 2021), which raises questions about the level of support necessary for educational leaders to draw on non-traditional data that can elevate the voices of those at the center of improvement work.

This study makes a unique contribution to improvement research because it examines a district-led CI initiative that relies on support and resources from the community school district and NYCPS system rather than relying on external support providers as is typical in much CI research (Anderson and Davis, 2024; Valdez et al., 2020; Yurkofsky, 2022). Studying more “home grown” CI work is essential for moving from a focus on discrete “initiatives” to integrating CI approaches into the daily work of educators and educational systems. The NICs in this study were each supported by a team of facilitators composed of school and district leaders recognized as equity leaders as well as one district leader identified as the IS “expert” based on their training and responsibilities. This combination supported the use of IS processes and tools, such as the PDSA cycle, and encouraged attention to equity throughout the process. However, the shifts in the roles of the NIC facilitators in this study created challenges for maintaining attention to IS, a common challenge for CI plagued by district turbulence (Yurkofsky et al., 2020). When NYCPS shifted the role of district leaders serving in the role of IS “experts” in the 2nd year of the NICs, attention to the fuller IS process diminished. Further, most of the facilitators were full time administrators (e.g., deputy superintendents, instructional specialists, and principals) with competing responsibilities that made planning and leading the NICs challenging. Scholars argue that coaching for equity-focused continuous improvement is responsive to the needs of learners and their goals and requires coaches to develop the relationships and trust needed to facilitate change (Aguilar, 2020; Anderson and Davis, 2024; Woulfin et al., 2023), which requires high levels of coaching capacity as well as time dedicated to providing this more intensive support. While the NICs in this community school district struggled to maintain attention to the IS process, the strong equity leaders who facilitated the NICs centered equity throughout their work.

I draw on Gutiérrez's (2012) framework and recent scholarship applying this work to NICs (Viano and Stosich, 2024) to define the range of improvement work that would be considered equity-focused, from more dominant approaches that seek to address access and achievement within the system as it currently exists to more transformative approaches that center students' culture and identities and focus on redesigning education systems to be more just and anti-racist. This framework can serve as a tool for research and practice that seeks to understand and support more critical approaches to centering equity in CI. District leaders in this study worked with principals to identify the problems of practice that each NIC would focus on; while district and school leaders' made sense of the problem focus for each NIC in ways that varied and addressed multiple dimensions of equity, the three NICs focused primarily on increasing access to education by reducing chronic absenteeism (CA NIC), affirming students' culture and identity through developing culturally responsive-sustaining curriculum and assessments (CRSE NIC), and increasing students' sense of belonging through inclusive and affirming school environments (SEL NIC). In this way, district leaders encouraged attention to more dominant and critical dimensions of equity from the inception of the NICs. Districts can play an essential role in determining whether and how equity is centered in continuous improvement through what they choose to focus on and how they approach improvement (Roegman, 2020).

This study contributes to a growing body of scholarship that critically examines the potential for IS and related CI approaches to be used to address the wicked problems posed by educational inequity (Anderson et al., 2023; Bush-Mecenas, 2022; Hinnant-Crawford, 2020; Viano and Stosich, 2024). Given that advancing equity is long term work that involves addressing deeply rooted beliefs, changing policies and practices, and redesigning systems (Ishimaru and Galloway, 2021), some scholars have argued that CI approaches that focus on testing and refining small changes through cycles of disciplined inquiry lack sufficient attention to the relational elements of change (Yurkofsky et al., 2020) and are a poor match for the system transformation ultimately required to advance equity (Safir and Dugan, 2021). Research in the field suggests that CI approaches, such as IS, can be used to advance equity-focused improvement but are relatively equity-neutral by design (Bush-Mecenas, 2022; Viano and Stosich, 2024). This study examines a critical case for how CI approaches can be used to advance equity-focused improvement in schools and districts with deep commitments and investments to equity and justice. Further research is needed to understand how CI approaches can be redesigned (Anderson and Davis, 2024) or combined with complementary support to maintain and deepen attention to equity work that transforms schools and districts to allow all students to thrive, including in schools and districts without prior investments in equity-focused reform.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because, according to the IRB application approved, the data cannot be shared with others beyond the researcher. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to: ZXN0b3NpY2hAZm9yZGhhbS5lZHU=.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Fordham University Institutional Review Board, New York City Public Schools Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

ES: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Support for this study was generously provided by a Proof of Concept Grant from the Fordham Graduate School of Education.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aguilar, E. (2013). The Art of Coaching: Effective Strategies for School Transformation. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Aguilar, E. (2020). Coaching for Equity: Conversations That Change Practice. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Anderson, E., Cunningham, K. M., and Eddy-Spicer, D. H. (2023). “Equity-oriented continuous improvement,” in Leading Continuous Improvement in Schools (London: Routledge), 75–110.

Anderson, E., and Davis, S. (2024). Coaching for equity-oriented continuous improvement: facilitating change. J. Educ. Change 25, 341–368. doi: 10.1007/s10833-023-09494-6

Biag, M., and Sherer, D. (2021). Getting better at getting better: improvement dispositions in education. Teach. Coll. Rec. 123, 1–42. doi: 10.1177/016146812112300402

Bonney, E. N., Yurkofsky, M. M., and Capello, S. A. (2024). EdD students' sensemaking of improvement science as a tool for change in education. J. Res. Leaders. Educ. 2024:1032. doi: 10.1177/19427751231221032

Bryk, A. S., Gomez, L. M., Grunow, A., and LeMahieu, P. G. (2015). Learning to Improve: How America's Schools Can Get Better at Getting Better. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Bush-Mecenas, S. (2022). “The business of teaching and learning”: institutionalizing equity in educational organizations through continuous improvement. Am. Educ. Res. J. 59, 461–499. doi: 10.3102/00028312221074404

Coburn, C. E. (2004). Beyond decoupling: rethinking the relationship between the institutional environment and the classroom. Sociol. Educ. 77, 211–244. doi: 10.1177/003804070407700302

Coburn, C. E., and Penuel, W. R. (2016). Research-practice partnerships in education: outcomes, dynamics, and open questions. Educ. Research. 45, 48–54. doi: 10.3102/0013189X16631750

Coburn, C. E., and Stein, M. K. (2006). “Communities of practice theory and the role of teacher professional community in policy implementation,” in New Directions in Educational Policy Implementation: Confronting Complexity, ed. M. I. Honig (New York, NY: State University of New York Press), 25–46.

Code Switch (2021). The Racial Reckoning That Wasn't. National Public Radio. Available at: https://www.npr.org/transcripts/1004467239 (accessed August 1, 2024).

Cohen, D. K., and Weiss, J. (1993). “The interplay of social science and prior knowledge in public policy,” in Studies in the Thought of Charles E. Lindblom, ed. H. Redner (Boulder, CO: Westview), 210–234.

Datnow, A., and Park, V. (2018). Opening or closing doors for students? Equity and data use in schools. J. Educ. Change 19, 131–152. doi: 10.1007/s10833-018-9323-6