- Department of English, College of Sciences and Arts, King Abdulaziz University, Rabigh, Saudi Arabia

Biographic translation is crucial in today’s globalized world to preserve histories or shed light on the lives of people who influenced their nations or the world. The literature on biographic translation and the factors hindering such translation in an English as a foreign language (EFL) setting, especially in the Saudi context, is relatively limited. In the present study, the author analyzed the errors made by Saudi EFL learners when they translated a biography from Arabic into English. The data were drawn from a short text translated by female final-year university students as part of their course evaluations. The author conducted a qualitative analysis and classified errors according to Pospescu’s taxonomy. The results showed that the students committed all the three error types: linguistic, comprehensive, and translation. Within these three types, the students made diverse errors, ranging from misusing tenses to misspelling words. Consequently, their overall translations were unsatisfactory. This finding is helpful for both learners and educators, as the identified translation errors can be used as teaching aids in translation classes. The findings put emphasis on the importance of practice and prompt feedback as essential aids educators can use to support their students during their translation learning.

Introduction

Technological advances and economic developments have made the world a largely interconnected place. One result of this globalization is an increased demand for translation services in countries where none of the languages used globally in business, technology, and/or science are spoken proficiently by most of the population. Translation bridges communication difficulties between countries that do not share a common language, facilitates exchanges of ideas between them, and facilitates their participation in globally significant developments. As Newmark (2003) stated, there is “no global communication without translation” (p. 55). Consequently, successful communication in such contexts depends on translators and interpreters (Cúc, 2018).

Translation is the process of transferring texts from one language to another (House, 2015; Newmark, 1988). To do this efficiently, translators require competence in both the source and target languages. Although languages in the same family (e.g., Romance languages) share certain common features, English and Arabic are inherently different in terms of their linguistic systems (Alasmari et al., 2016; Bashir, 2022; Raheem et al., 2023). Word order, adjective placement, the use of singular and plural forms, and gender agreement are only some examples of these differences. In addition to this structural dissimilarity, cultural aspects that influence the meaning of the source text need to be considered during the translation process, which may necessitate content adjustments (Elhadary, 2023). Professional translators must be conscious of the changes required to produce successful translations, both in terms of structure and content, which is why learning to make appropriate modifications is usually an important element of university translation courses.

Translation programmes in Saudi Arabian universities cover both theory and practice. Thus, students learn about translation theory on the one hand and apply their knowledge to in-course translation projects on the other, translating different types of texts (e.g., legal, scientific, technical, and religious documents) from English into Arabic and vice versa. Despite this exposure, many students still produce English texts that are nowhere near fluent. Their courses do not adequately prepare them to work in the translation industry. Research on the types of errors translation students make may help solve this problem, since the identified common issues could serve as starting points for improving university translation programmes. Error analysis, according to Waddington (2001), is a useful method for evaluating students’ translations, and it was the method used in this study. Error analysis is useful because it helps identify learners’ needs and weaknesses during the learning process, and insight gained from such needs and weaknesses can be shared with teachers and instructors to help them develop appropriate solutions.

In the present study, the author specifically investigated errors made by female Saudi English as a foreign language (EFL) learners enrolled in the translation programme at Hafr Albatin University in Saudi Arabia. The author aimed to identify the students’ most common mistakes in translating an Arabic text into English and what caused those mistakes. Accordingly, the research questions that guided the analysis and discussion were as follows:

1. What types of errors are common in the Arabic–English translations produced by female EFL students enrolled in the translation programme at Hafr Albatin University?

2. What possible underlying factors influence these errors?

The results of this study are generally applicable to other contexts in which similar courses are taught.

Literature review

The term error may broadly be defined as inaccuracy in a given context. According to Lennon (1991, p. 182), linguistics refers to “a linguistic form or combination of forms which, in the same context and under similar conditions of production, would, in all likelihood, not be produced by the speakers” native speaker counterparts’. Cunningworth (1987, p. 87) defined linguistic errors as deviations in language norms. In terms of translation, the accuracy of a message transferred from one language to another may be seen as a measure of translation quality. Translation errors are obstacles to efficient communication, and they may, for instance, manifest as incorrect knowledge transfers, formal linguistic mistakes, impenetrable cultural references in the target text, or shifts in style that affect the quality of the resulting text.

Because source and target languages and researchers’ approaches to a topic may differ to a greater or lesser extent, translation error classifications are not universally applicable (Cúc, 2018), because they are based on different theoretical frameworks. Nord (1997), for example, divided translation errors into four categories: pragmatic errors, cultural errors, linguistic errors, and text-specific errors. Pragmatic errors can be caused by inadequate solutions to pragmatic problems, such as failing to correctly interpret the source text’s message. Cultural errors are mainly caused by a lack of awareness of the source language culture. Linguistic errors are errors linked to the language’s rules and systems, while text-specific errors are related to errors in text types. Popescu’s (2013) classification grouped errors into three main categories, with several subcategories each: linguistic errors (including morphological, syntactic, and collocational errors), comprehension errors (including misunderstanding of lexis or syntax), and translation errors (including errors related to distorted meaning, additions, omissions, and inaccurate renditions of lexical items). Putri (2019) conducted a review of research on translation errors and discovered that semantic, lexical, morphological, and grammatical errors predominated in the translated texts. Regardless of the classification used, it is obvious that any errors disturb the flow of texts.

Several factors must be considered when analyzing translation errors. For example, there is no doubt that working with two very dissimilar languages causes particular difficulties that do not arise when the source and target language belong to the same language family. The research findings regarding translation in EFL contexts support this theory. For example, Farrokh (2011) analyzed the errors made by Iranian learners of English in translating 20 Persian sentences into English. The analysis revealed that wrong word choice and incorrect use of tenses were the most frequent errors. Similarly, Hakeem (2016) examined university students’ translations of texts from Kurdish into English. The students made various errors, ranging from lexical errors to grammatical errors. Sari (2019) analyzed errors made by Indonesian university students when they translated texts from Indonesian into English and concluded that, in general, learners committed two types of errors: lexical and grammatical. Lexical errors were mainly exemplified by wrong word choices, while grammatical errors included tense and preposition misuses and incomplete sentences. Maia et al. (2022) investigated the problems encountered by Tetum speakers when they translated from Tetum into English and discovered that, besides lexical and grammatical errors, participants also omitted unknown structures instead of translating them. Focusing only on tenses, Tsai (2023) compared the tense information in undergraduates’ Chinese–English translated texts and found that although the Chinese source texts were written in the present tense, the students tended to switch from the present tense to the future or past tense in their translations.

Translation errors have received some attention from Arabic researchers due to their link with learners’ competence in English and the fluency of translated texts. Badawi (2008) researched Saudi EFL students’ translation strategies and found that they opted for literal translations more often than for appropriate equivalents when translating texts. Esmail (2017), investigating translation errors made by Iraqi university students, discovered that students made errors at all language levels. Aligning with Badawi’s findings regarding translation strategies, these errors appeared to be related to applying the linguistic rules of Arabic to English during the translation process, resulting in literal translations. Similarly, Ababneh (2019) compared the translations of a list of phrases and expressions produced by students studying at two different Saudi universities and found that insufficient knowledge of the English language, unfamiliarity with some English terms, and literal translations led to students’ translation errors.

These studies indicate that despite obvious fundamental differences between English and Arabic, literal translation is common among Arabic-speaking EFL learners when translating from Arabic into English. However, it is worth mentioning that previous researchers considering Arab learners, particularly Saudi learners, applied translation error analysis to diverse data sets, such as quizzes and phrases, and used different analytical procedures; hence, their studies may not be entirely comparable. Moreover, they did not consider certain text types. Therefore, in the present research, the author focused on a text type that has received little attention—biography—to investigate what types of errors emerged in the translations of this particular type of text.

Methodology

Research design

Due to the nature of the translation and the purpose of this study, the author chose qualitative text analysis to investigate and analyze participants’ translation errors. Such qualitative analysis rests on a description of the participants, data instrument, and data analysis and includes error identification and classification, identification of error sources, and possible remediation.

Participants

Male and female students in Saudi Arabia are segregated in educational institutions. This segregation makes it uneasy for a female researcher to interact with male students and vice versa. The participants were 33 female English major undergraduates aged 22–24 years who were in their final year in the Department of Foreign Languages at Hafr Al-Batin University in Saudi Arabia. Translation constituted 90% of their studies, with courses ranging from translation theory to practical specializations in technical and scientific, legal, religious, and creative translation. This diversity suggests that the participants were familiar with translation theories and strategies and that they had been exposed to various texts and practices. At the time of the study, the participants had completed all the theoretical and applied translation courses and were expected to graduate in the summer with bachelor’s degrees in translation. The researcher informed the students that part of their work would be used for research purpose and explained the purpose of the study to the students and confirmed that their identities would be anonymous, and that the data would only be used for research purposes.

Data instrument

As part of one of their courses in 2022, the students were asked to translate a short (5-line, 90-word) biographical text about the life of the scientist Isaac Newton from Arabic into English. As the study is a preliminary one, this short text was considered sufficient for exploring the students’ translation and the possible errors they may commit. The original English text had previously been used as part of the students’ coursework. It was intended for a lay audience and was therefore written in simple English. The original English text had previously been used as part of the students’ coursework; hence, the participants were already familiar with the content and could be expected to find the exercise easy.

Data collection

The translation task was a part of an assessment for a course named “Technical and Scientific Translation.” The text was one section of several sections of graded tests that students were required to take for their overall evaluation in the course. The author, who was the course instructor, distributed the texts to the students and collected them and completed the evaluation on the same day. The students were given 120 min to complete the test, and their translations provided the data for the present study.

Data analysis

To answer the research questions, the author analyzed the student’s translation errors following Popescu’s (2013) taxonomy, classifying the errors as linguistic errors, comprehension errors, and translation errors, each with subtypes. Linguistic errors included morphological, syntactic, and collocational errors; comprehension errors consisted of lexis or syntax misunderstandings; and translation errors involved errors related to distorted meanings, additions, omissions, and inaccurate renditions of lexical items. The author examined the participants’ texts to identify their errors and classified them according to the three main types and subtypes. The examination process was conducted by reading the translated texts and underlying all the errors, then listing the errors under the classification in the taxonomy. Each text was read three times at least by the author to make sure all errors were identified and classified. Then, an EFL teacher who had taught translation courses and assessed students’ translations for more than 10 years checked the classifications to ensure that they were appropriate for the collected data and the taxonomy used.

Results

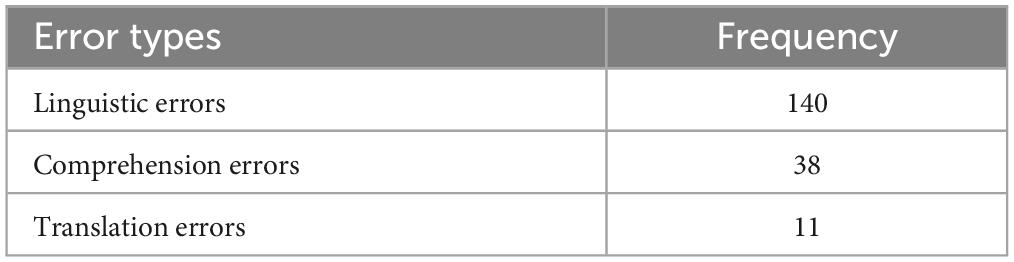

Considering the simplicity and shortness of the text, the students made a relatively high number of translation errors, with linguistic errors being by far the most common (see Table 1). In many of the participants’ sentences, more than one type of error was detected; for example, a single sentence could contain two errors related to two different classifications, perhaps due to the nature of the errors and how and where they occurred in the participants’ translations. Consequently, to concisely and comprehensively discuss the errors, the author explains the errors, their causes, and their effects according to the main classifications in the following paragraphs. Table 1 provides a summary of the error types and frequencies.

All types of linguistic errors (morphological, syntactic, and collocational) were identified in the texts. It is worth mentioning that when translating from Arabic into English, and vice versa, it is necessary to change the word order in most sentences. For example, in the translation “Growing esahic1 most of life alone,” the participant followed the Arabic sentence structure (verb followed by subject), transferring the words directly from Arabic into English, which resulted in a syntactic error (an ungrammatical sentence). Another syntactic error concerned adjective placement. In Arabic, adjectives follow nouns, and vice versa in English. In the translated sentence “society royal,” the student maintained the structure of the Arabic source text, failing to change the word order to English syntax. Similarly, various essential syntactic structures were missing from some translations. For example, a form of the verb “to be” is missing in the sentence “Ishaq was born most of the time of his life alone.” In English, the verb “to be”—in addition to being used as a main verb—is used as an auxiliary verb to form progressive tenses and the passive voice. In Arabic, there is no equivalent for this kind of structure, which may explain the students’ mistakes. The author categorized these errors as interlingual errors, which were common in the students’ translations because of the structural difference between the two languages.

Collocational errors also recurred in the participants’ texts. For example, the misuse of prepositions is evident in the sentence “Isac has joined to a college,” where the student used the preposition “to” incorrectly. Other examples showed the misuse of verbs in the translated texts (e.g., “He was prefer to work and living”), indicating that the students were not familiar with the correct usage.

Furthermore, morphological errors (e.g., a lack of subject/verb agreement) were evident in the data, such as in the sentence “When he lives most of his lives.” Other mistakes related to the addition of the past marker “was” before the main verb instead of changing the verb form to the past tense (e.g., “He was want and like to work” and “Isac was grew up alone”).

Alahmadi (2014) identified verb tense errors as a common translation problem among Saudi EFL students. When writing, learners have more time to deliberate on their choice of verb form and may more easily correct their own mistakes. The incorrect use of tenses suggests that learners lack a basic knowledge of them. Errors of this kind included the use of the present tense instead of the past tense. The fact that the text concerned Isaac Newton, who died almost 300 years ago, should have made it very clear that the past tense was appropriate. However, examples such as “Isac has grown up” and “Isac has joined a college” showed that the participants did not know how to use the present perfect tense correctly or how and when to use the simple past tense. Similarly, in some sentences, the simple present tense was used instead of the simple past tense (e.g., “In 1661, Ishaq starts attending college in Cambridge”). Although the text provided the date 1661—clearly indicating that the past tense should be used—the participant failed to apply the correct tense.

In terms of comprehension errors, misunderstandings of lexis predominated. For instance, the source text “ ” (original: “He was elected to represent the University of Cambridge”) was translated as “He chose to be the face of Cambridge” and “Select him to act at Cambridge University.” In the first example, the meaning is completely changed by giving Newton agency, and the phrase “the face of Cambridge” does not fit with the context. In the second example, the whole sentence is unclear because of the absence of an agent (it is not clear who selected Newton), and the word “act” is inappropriate to the context. Likewise, participants inappropriately used adverbs in some of the translations. In the sentence “Eshaq grew up all the time lonely,” the adverb “all” was used to translate the Arabic word “

” (original: “He was elected to represent the University of Cambridge”) was translated as “He chose to be the face of Cambridge” and “Select him to act at Cambridge University.” In the first example, the meaning is completely changed by giving Newton agency, and the phrase “the face of Cambridge” does not fit with the context. In the second example, the whole sentence is unclear because of the absence of an agent (it is not clear who selected Newton), and the word “act” is inappropriate to the context. Likewise, participants inappropriately used adverbs in some of the translations. In the sentence “Eshaq grew up all the time lonely,” the adverb “all” was used to translate the Arabic word “ ” instead of the direct equivalent “most,” meaning that the resulting sentence contained inaccurate information. Participants also made incorrect lexical choices, which, besides revealing a misunderstanding of lexis, showed a misunderstanding of sentence structure. For example, in the sentences “He was want and like to work” and “He was like work and live lonely,” the verbs “want” and “like” were placed in adjectival positions.

” instead of the direct equivalent “most,” meaning that the resulting sentence contained inaccurate information. Participants also made incorrect lexical choices, which, besides revealing a misunderstanding of lexis, showed a misunderstanding of sentence structure. For example, in the sentences “He was want and like to work” and “He was like work and live lonely,” the verbs “want” and “like” were placed in adjectival positions.

In the current study, the participants also confused verbs and nouns, which Popescu (2013) classified as translation errors. For example, they confused the verb “to start” with the noun “star,” perhaps due to the similar pronunciation. Moreover, they experienced some confusion regarding the verbs “to grow up” and “to be born”; some participants wrote “Isaac was born” instead of “Isaac grew up,” inadvertently changing the meaning of the sentence in the source text (a distorted meaning error). Notably, many of the students who used the verb “to be born” combined it with the adjective “alone.” It appears that these participants did not understand how to use adjectives correctly in conjunction with verbs. Similarly, they made both comprehension and translation errors, such as “He came a math Teacher” (i.e., using the verb “to come” instead of “to become”), and instead of the correct translation of “ ” (“royal society”), using words such as “city,” “company,” “charity,” “family,” “scholarship,” and “community.”

” (“royal society”), using words such as “city,” “company,” “charity,” “family,” “scholarship,” and “community.”

Another common translation mistake the participants made was erroneous omission of words or phrases. Sometimes, when an equivalent to a source word adds little to the meaning of the translated text, the translation can convey the meaning without it, and the word may be omitted. This technique is closely linked to implication, which Vinay and Darbelnet (1995) defined as “making what is explicit in the source language implicit in the target language, relying on the context or the situation for conveying the meaning” (p. 344). However, when a learner skips a word or phrase in their translation, it is usually not because they are using such advanced translation techniques, but because they simply do not know how to translate the words. In this study, omission errors occurred quite frequently. For instance, one student translated the source sentence ‘ ’ (“Isaac grew up most of the time alone”) as “Isac was alone,” omitting the verb phrase “grew up.” Similarly, another gave the sentence “He selects to be a member in parlaman” as a translation of “

’ (“Isaac grew up most of the time alone”) as “Isac was alone,” omitting the verb phrase “grew up.” Similarly, another gave the sentence “He selects to be a member in parlaman” as a translation of “ ” (“He was elected to represent the University of Cambridge”).

” (“He was elected to represent the University of Cambridge”).

Omissions also occurred at the level of single words when, for example, participants omitted prepositions and articles. In the sentences “When he live most his live,” “born Isac most the time alone,” and “He spent most time in Cambridge,” the students omitted the preposition “of.” Since prepositions were not used in the Arabic text the participants translated, they failed to make the necessary additions in their translations, resulting in ungrammatical sentences. Similarly, the students omitted some articles, such as in “He becomes a member of royal society.” In Arabic, articles, instead of being separate words, are particles attached to nouns. It is therefore unsurprising that in directly translating from Arabic into English, the students often neglected to add “the.”

Spelling errors “can be a result of omission, or substitution or insertion, or the misplacement of a letter when writing a particular word” (Altamimi and Rashid, 2019). Misspelling disturbs the coherence of a text (Albalawi, 2016), and thus negatively affects the overall quality of writing. In the present study, spelling errors were extremely common. For example, participants misspelled words such as “teacher” (*2 Techer), “scientist” (*scantests), “society” (*socite), “royal” (*Royall), “rest” (*rist), “college” (*colleg), “professor” (*prophsors), “where” (*wher), “he” (*hi), and “most” (*must). A lack of practice and an absence of serious assessment could have led to the participants misspelling even simple, everyday words. It is also possible that because some of the misspelled words contained diphthongs, participants failed to recognize them as vowels, or that mispronunciation underpinned the mistakes. Spelling errors can obviously change the intended meaning of a word. Thus, misspelling the pronoun “he” as “hi” changed both the meaning and (taken out of context) the function of the source word. The same can be said about spelling the determiner “most” as the modal verb “must.”

As mentioned in a footnote, the name “Isaac” was translated in diverse ways, including “Eshac,” “Eshaq,” “Iozoq,” “Ishaq,” and “Eshac.” In many of their translations of the scientist’s name, the participants introduced the sound /∫/, despite the Arabic pronunciation being similar to the English pronunciation. It may be that the participants added the /h/ sound as an equivalent of the /τh/ sound, which does not exist in English but constitutes part of the scientist’s name in Arabic and is often pronounced as /b/. Another example is the aspirated bilabial plosive phoneme /p/, which does not exist in Arabic. Many of the Saudi EFL learners’ spelling errors may have resulted from differences between the sound systems of the two languages. In the study data, “Parliament” was misspelled as “barliment” or “Barlaman,” echoing the Arabic word “ ,” which contains no /t/ sound. Comparably, a confusion between the alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/ led to the students replacing “d” with “t” (e.g., spelling “nominated” as “Nomaneded”), indicating a misrepresentation of the /I/ sound. In another example, students misspelled the labiodental fricative /f/ sound in the word “prefer” as “v,” spelling it as “prever” or “brever.”

,” which contains no /t/ sound. Comparably, a confusion between the alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/ led to the students replacing “d” with “t” (e.g., spelling “nominated” as “Nomaneded”), indicating a misrepresentation of the /I/ sound. In another example, students misspelled the labiodental fricative /f/ sound in the word “prefer” as “v,” spelling it as “prever” or “brever.”

Additionally, many participants misspelled the names of the country (England) and the university (Cambridge). This finding aligns with Ababneh (2019), whose participants likewise had problems with the English spelling of country names. In the current study, the participants represented the /I/ sound at the beginning of “England” with either an “i” or an “a.” In writing the proper noun Cambridge, the students made various peculiar spelling mistakes: “Cumberdge,” “Cambird,” “Camprudge,” and “Cambreidge,” apparently failing to notice any difference between the vowel sounds. Moreover, many failed to use the correct English representation of the name’s final sound ( ). The students who participated in Ababneh’s (2019) research and those who participated in the present study attended the same university, suggesting that the teaching of phonetics and phonology at Hafr Albatin University is inadequate; thus, students would benefit from additional writing practice, especially when translating texts into English.

). The students who participated in Ababneh’s (2019) research and those who participated in the present study attended the same university, suggesting that the teaching of phonetics and phonology at Hafr Albatin University is inadequate; thus, students would benefit from additional writing practice, especially when translating texts into English.

Spelling errors are common in English writing in Saudi Arabia, as evidenced by various studies (e.g., Alhaisoni et al., 2015; Aloglah, 2018; Hameed, 2016; Othman, 2018) but also in Arabic contexts generally (e.g., Al-Zuoud and Kabilan, 2013; Benyo, 2014). According to Alenazi et al. (2021), interlingual and intralingual factors are a major cause of Saudi English learners’ spelling errors in translation. As seen in this section, participants made diverse errors, indicating that their English language skills were lacking.

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to investigate the errors that EFL Saudi students make when translating texts from Arabic into English to answer the research question: What types of errors are common in the Arabic–English translations produced by female EFL students enrolled in the translation programme at Hafr Albatin University? The result showed that, overall, the students made an extensively high number of errors to the extent that the consistency of the texts was lost and, thus, most of their translated texts were illegible.

In terms of error classifications, students committed all the three types of errors in Popescu’s taxonomy. Linguistic errors were the highest, followed by comprehension and translation errors. The finding is in line with previous findings in EFL contexts (e.g., Ababneh, 2019; Cúc, 2018; Popescu, 2013). The types of errors identified in this study were, according to Waddington’s (2001) error evaluation study, major translation errors because they affected the conveyance of meaning in the target language.3 The errors indicated that the students had failed to adhere to the correct sentence structure in English. In other words, they literally translated the sentence according to their first language—Arabic, which represents a violation to the English syntax convention. This violation clearly reveals that the students lacked basic knowledge of the target language, and thus their English is in need for improvement. Moreover, the tendency of the participants to ignore translating a word and omitting it is a serious indicator that participants, beside lacking adequate knowledge of vocabulary and their equivalence, were also unfamiliar with the translation protocol about omission and addition. These errors could also indicate that literal translation was adopted. The reliance on literal translation could be a sign that the students were unaware of the appropriate translation approaches and the conditions and circumstances of applying each approach.

The finding shows that the students failed to create a well-coherent translation that expresses the original text. As the original English text presented to them in the past before the translation task, it was thought that the participants would be able to understand the structures and observe the relevant vocabulary when they are presented with the translation task. However, the amount of the errors the participants made indicated that participants did not benefit from that advantage and failed to realize and comprehend the appropriate translation of a biographic text.

Another objective of the current research was to identify the possible factors that causes translation errors in order to answer the following research question: What possible underlying factors influence these errors?

As seen in the previous section, participants’ diverse errors reflected their lack of English language skills. Al-Siyami (1994) pointed out that translation errors made by Arabic speakers may result from various factors, including inadequate teaching procedures and learning strategies, which may lead to low levels of foreign language proficiency. The factors that may have contributed to the students’ translation errors could be the interference of the first language, lack of competence in the target language —English—, lack of awareness of the different structures in their first language and the target language, lack of knowledge of the appropriate translation techniques and approaches, lack of practices and exposure to translation tasks, and lack of adequate feedback. As the participants were in their final year, it was expected that these factors were controlled for in the previous years.

In addition to the mentioned factors, anxiety was reported in past research (e.g., Duklim, 2022, Putri, 2019) as a cause of errors in translation. In the current research, the original English text was presented to the students in a previous practice. It was hoped that this previous exposure would contribute into creating a less stressful atmosphere, especially since translation into English is considered as an overwhelming and effortful practice by many EFL students. It was expected that the participants would be able to understand the structures and observe the relevant vocabulary when they are presented with the translation task in this research. However, the amount of the errors the participants made indicated that participants did not benefit from that advantage and failed to realize and comprehend the appropriate translation of a biographic text.

In brief, the finding of the present study shows that the students failed to create a well-coherent translation that expresses the original text. The finding puts emphasis on the importance of extensive practice of translating to and from English in order for translators to comprehend the difference between their first language and English and, consequently, to realize the appropriate methods and techniques to interpret and translate the text.

Conclusion and implications

In the present study, the author investigated the types of errors commonly made in female EFL students’ Arabic–English translations at Hafr Albatin University. The study contributes to EFL research by shedding light on the main English language errors made by Saudi students at the university level. Overall, the participants’ translations were unsatisfactory. Their target language texts lacked coherence, and in many cases, errors were so frequent that the translations were difficult to understand.

According to Pospescu’s (2012) framework, participants made different types of errors, ranging from misusing tenses to misspelling words. Most of these errors seemed to be due to the influence of the participants’ first language. However, since they were advanced students in the final stage of their translation studies, the participants should have been familiar with the differences between the two language systems and with the adjustments that were necessary in the translation process based on these dissimilarities. Unfortunately, this did not seem to be the case. In making elementary-level mistakes, the students appeared not to have benefitted greatly from their past studies. They showed a severe lack of translation knowledge and an overall low level of English language proficiency. This study’s findings, although disappointing in revealing an unacceptable state of affairs, are vitally important for learners and educators. Participants’ unsatisfactory performance probably resulted from insufficient translation exercises in the classroom. According to Presada and Badea (2014), it is common for teachers to devote considerable time to the theoretical aspects of translation at the expense of practice.

Identifying and analyzing translation errors could be used as a teaching aid. By diagnosing problems, investigating their sources, and applying remedial strategies, students can improve their translation skills. Appropriate curriculum design and teaching material selection could help teachers prepare lessons specifically tailored to address learners’ errors. For example, since linguistic errors predominated in the participants’ texts in this study, educators could provide learners with translation exercises that clearly highlight the structural differences between English and Arabic. August and Shanahan (2006) suggested that focusing on similarities and differences between English and EFL learners’ native languages and using, where necessary, their native languages to describe these similarities and differences is an effective way of improving students’ language skills. Simply put, this strategy would raise learners’ awareness of the patterns of English. Farooq and Wahid (2019) made a similar point, arguing that contrastive analysis is a valuable tool in many EFL settings because it helps explain why learners acquire some features of language more readily than others. Regarding comprehension and translation errors in general, and word choice in particular (i.e., finding appropriate translations for words and expressions in the source text), was another area of difficulty for the participants in the present study; hence, instructors could provide learners in translation classes with synonym and near-synonym lists and discuss with their students the best options for conveying the intended meanings. This would be particularly useful in situations where no direct equivalents of words exist.

As translation students, the participants were expected to be confident in using all English tenses and, thus, be familiar with the various forms of regular and irregular verbs, which prepositions to use when, and how to spell at least the most common English words correctly. The participants should have acquired this knowledge during their first year at university. The fact that the participants made basic mistakes shows that their previous assignments were not accurately graded, meaning that they entered their final year without acquiring advanced-level translation skills. If their abilities had been evaluated correctly, they would have either stopped making these kinds of errors before their final year or would not have progressed to that stage at all. Therefore, to ensure that students acquire the necessary translation skills, educators in translation programmes should grade assignments accurately, without disregarding simple mistakes, and request corrections from learners. Moreover, students would benefit from being made aware of the assessment criteria upon which their work is evaluated so that they know what to expect and which areas need improvement. Any failure or negligence in evaluation may have negative consequences for students, since they may not realize the importance of applying themselves and may be unable to achieve language proficiency or improve their translation skills.

Students must be given opportunities to practice their skills regularly and frequently to ensure effective learning. In the context of translation studies, this means that the more learners are exposed to situations in which they actively practice translation, the fewer errors they will make, and the more the quality of their target language texts will improve.

Limitations and further research

Although the results of the present study shed light on EFL learners’ errors in a specific field of translation—biographic translation—it has certain limitations. First, the data used in this study were limited to translations of a specific short text. Other texts with different lengths may generate other types of errors. Second, the study sample was small and limited to female students at a particular university. Recruiting other samples (e.g., male students or students from different universities in different geographical areas) may generate different results. Third, the author categorized the errors according to a specific taxonomy [ Pospescu’s (2012) taxonomy]. Other taxonomies or instruments may yield different classifications from those identified in this research. Finally, the lack of previous research studies on biographic translation in this particular context, Arabic-language, may constitute a limitation of the current research. Future researchers should focus on this type of translation to expand the relevant body of knowledge.

The growing international recognition of Saudi Arabia today highlights the importance of understanding its history. Translation of the biographies of Saudi kings, their lives, and the struggles they experienced from the foundation of the country onward would contribute to preserving the country’s history for the younger generations and spreading its heritage to other cultures. Therefore, future researchers should investigate the translation of different biographies to account for any factors that hinder the readability of history and heritage. Analysis of the various errors translators make when they translate different biographical texts would help to provide a better picture of biographical translation in the Saudi EFL context.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the patients/participants or patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

MA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author declares that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1428690/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

- ^ The name “Isaac” was mistranslated in various different ways (e.g., as “Esahic,” “Ishaq,” and “Isac”).

- ^ Incorrect structures are referred to by asterisks.

- ^ Participants also failed to use correct punctuation and capitalization. However, due to the focus of this study, the author did not consider such mechanical errors.

References

Ababneh, I. (2019). Errors in Arabic–english translation among Saudi students: Comparative study between two groups of students. Arab World Engl. J. Transl. Literary Stud. 3, 118–129. doi: 10.24093/awejtls/vol3no4.10

Alahmadi, N. (2014). Error analysis: A case study of Saudi learners’ english grammatical speaking errors. Arab World Engl. J. 5, 84–98.

Alasmari, J., Watson, J., and Atwell, E. S. (2016). “A comparative analysis between Arabic and English of the verbal system using Google Translate,” in Proceedings of IMAN 2016 4th International Conference on Islamic Applications in Computer Science and Technologies, 20–22 Dec 2016, (Khartoum).

Albalawi, F. S. (2016). Analytical study of the most common spelling errors among Saudi female learners of English: Causes and remedies. Asian J. Educ. Res. 4, 48–62.

Alenazi, Y., Chen, S., Picard, M., and Hunt, J. W. (2021). Corpus-focused analysis of spelling errors in Saudi learners’ English translations. Int. TESOL J. 16, 4–24.

Alhaisoni, E. M., Al-Zuoud, K. M., and Gaudel, D. R. (2015). Analysis of spelling errors of Saudi beginner learners of English enrolled in an intensive English language program. Engl. Lang. Teach. 8, 185–192. doi: 10.5539/elt.v8n3p185

Aloglah, T. M. (2018). Spelling errors among Arab English speakers. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 9, 746–753. doi: 10.17507/jltr.0904.10

Al-Siyami, A. (1994). Error Analysis in Translation: An Applied Study on the Students of Fourth Year Level in Girls’ College of Makkah (a Linguistic Approach). Unpublished master’s thesis. KSA: Girls’ College of Makkah.

Altamimi, D., and Rashid, R. A. (2019). Spelling problems and causes among Saudi English language undergraduates. Arab World Engl. J. 10, 178–191. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol10no3.12

Al-Zuoud, K., and Kabilan, M. (2013). Investigating Jordanian EFL students’ spelling errors at the tertiary level. Int. J. Ling. 5, 164–176. doi: 10.5296/ijl.v5i3.3932

August, D., and Shanahan, T. (2006). Developing Literacy in Second-Language learners: Report of the National Literacy Panel on Language-Minority Children and Youth. Milton Park: Routledge.

Badawi, M. (2008). Investigating EFL Prospective Teachers’ Ability to Translate Culture-Bound Expressions. [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Saudi Arabia: University of Tabuk.

Bashir, T. (2022). Comparative analysis of Arabic and English verbs: An overview. Sprin J. Arabic Engl. Stud. 1, 170–176. doi: 10.55559/sjaes.v1i03.16

Benyo, A. F. (2014). English spelling problems among students at the University of Dongola. Sudan. Int. Res. J. Educ. Res. 5, 476–484.

Cúc, P. (2018). An analysis of translation errors: A case study of Vietnamese EFL students. Int. J. Engl. Ling. 8, 22–29. doi: 10.5539/ijel.v8n1p22

Cunningworth, A. (1987). Evaluation and Selecting EFL Materials. Portsmouth: Heinemann Education Books.

Duklim, B. (2022). Translation errors made by thai university students: A study on types and causes. rEFLections 24, 344–360.

Elhadary, T. (2023). Linguistic and cultural differences between English and Arabic languages and their impact on the translation process. J. Propulsion Technol. 44, 1655–1662. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226610

Esmail, W. M. (2017). Applying error analysis in teaching translation. J. Al-Ma’moon Coll. 29, 175–189.

Farrokh, P. (2011). Analysing EFL learners’ linguistic errors: Evidence from Iranian translation trainees. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 1, 676–680.

Hakeem, S. (2016). A linguistic analysis of errors in undergraduate students’ translated texts. Suppl. Issue 20:2016.

Hameed, P. (2016). A study of the spelling errors committed by students of English in Saudi Arabia: Exploration and remedial measures. Adv. Lang. Literary Stud. 7, 203–207. doi: 10.7575/aiac.alls.v.7n.1p.203

Lennon, P. (1991). Error: Some problems of definition, identification, and distinction. Appl. Ling. 12, 180–195. doi: 10.1093/applin/12.2.180

Maia, F., Sarmento, J., Soares, M., and Silva, M. (2022). An error analysis of translation sentence from Tetum to English in simple present tense. J. Educ. Cie^ncia e Humaniora 3, 125–135.

Newmark, P. (2003). “No global communication without translation,” in Translation Today: Trends and Perspectives, eds G. Anderman and M. Rogers (Bristol: Multilingual Matters), 55–67.

Nord, C. (1997). Translating as a Purposeful Activity: Functionalist Approaches Explained. Milton Park: Routledge.

Othman, A. K. A. (2018). An investigation of the most common spelling errors in English writing committed by English-major male students at the University of Tabuk. J. Educ. Pract. 9, 17–22.

Popescu, T. (2013). A corpus-based approach to translation error analysis: A case-study of Romanian EFL learners. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 83, 242–247. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.048

Presada, D., and Badea, M. (2014). The effectiveness of error analysis in translation classes: A pilot study. Porta Linguarum 22, 49–59. doi: 10.30827/Digibug.53695

Putri, T. A. (2019). An analysis of types and causes of translation errors. Etnolingual 3, 93–103. doi: 10.20473/etno.v3i2.15028

Raheem, D. S., Benny, N. S., and Murthy, D. V. R. (2023). A comparative study of linguistic ideology in English and Arabic language. Int. J. Literature Lang. Ling. 3, 17–27. doi: 10.52589/IJLLL-7FVNB8WN

Sari, D. (2019). An error analysis on student’s translation text. Eralingua Jurnal Pendidikan Bahasa Asing dan Sastra 3, 65–74.

Tsai, P. (2023). An error analysis on tense and aspect shifts in students’ Chinese–english translation. Sage Open 13, 1–13. doi: 10.1177/21582440231158263

Vinay, J.-P., and Darbelnet, J. (1995). Comparative Stylistics of French and English: A Methodology for Translation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

Keywords: syntactic errors, morphological errors, semantic errors, misuse of prepositions, omission

Citation: Alluhaybi M (2024) Lost in translation: error analysis of texts translated from Arabic into English by Saudi translators. Front. Educ. 9:1428690. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1428690

Received: 12 May 2024; Accepted: 30 October 2024;

Published: 13 November 2024.

Edited by:

Javad Gholami, Urmia University, IranReviewed by:

Mohammad Najib Jaffar, Islamic Science University of Malaysia, MalaysiaHimdad Abdulqahhar Muhammad, Salahaddin University, Iraq

Hamza Alshenqeeti, Taibah University, Saudi Arabia

Copyright © 2024 Alluhaybi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maram Alluhaybi, bW1hbGxlaGFiaUBrYXUuZWR1LnNh

Maram Alluhaybi

Maram Alluhaybi