- 1School of Education, University of California, Riverside, Riverside, CA, United States

- 2Department of Pediatrics, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, United States

Background: The UCLA PEERS program has been studied using predominantly White and affluent populations. As autistic teens and their parents are represented across cultures, it is vitally important that interventions are tailored to their needs–whether that be linguistically or with respect to their cultural practices. Thus, the current qualitative study explored whether culturally and linguistically diverse families (primarily Latine) participating in the PEERS program had recommendations for adaptations to improve their experience and make the program more culturally sensitive.

Method: The study utilized a sample of 13 autistic teens and their parents who completed the original 16-week PEERS program with content delivered bilingually.

Results: All parents and teens recommended the program to other families. Although the intervention was largely accepted in its current format, suggestions were put forth regarding how to adapt the program to be more accommodating of Latine cultural views on parenting.

Conclusion: The PEERS program is an evidenced based intervention with well documented positive results. This paper contributes to a growing body of literature highlighting both the importance of including underrepresented demographic groups in research and factoring in cultural adaptations to increase validity of interventions previously normed on White affluent populations.

Introduction

The UCLA PEERS program is a 16-week, intensive social skills intervention for autistic teens without co-occurring cognitive difficulties/intellectual disability that is either parent-assisted (Laugeson et al., 2012) or delivered by educators in the school setting (Laugeson et al., 2014). The program is made up of didactic lessons with role play demonstrations, where adolescents and parents receive concurrent lessons in separate rooms. There is an emphasis on completion of weekly homework assignments to reinforce concepts learned during didactic sessions (Laugeson and Frankel, 2010). Parent groups discuss completion of the homework assignments and troubleshoot any problems that occurred while their youth were completing the assignment(s). Social skills sessions focus on the following topics: conversational skills (starting and maintaining two-way conversations), using electronic communication, choosing appropriate friends, appropriate use of humor, entering/exiting a group conversation, get-togethers, good sportsmanship, handling rejection (teasing and embarrassing feedback, physical bullying, cyber bullying, and gossip), handling arguments and disagreements, and changing reputations (Laugeson and Frankel, 2010; Laugeson et al., 2014). The PEERS program has been heavily researched and is well represented in the social skills intervention literature (Laugeson et al., 2012, 2014, 2015). The program has been replicated at other sites, (e.g., Schohl et al., 2014, Van Hecke et al., 2015) and randomized controlled trials of the program have consistently reported significant improvements in overall social skills, frequency of social engagement, and reduced autism-related deficits in social responsiveness (Laugeson et al., 2014; Schohl et al., 2014), including the present study’s sample reported here (Veytsman et al., 2022). Although the PEERS program has been highly effective in improving social competence in autistic teens, most studies report low numbers of Latine participants (Zheng et al., 2021). Additionally, despite being translated into several languages, the materials have not been culturally validated, which is a limitation of the program (DuBay et al., 2018). In a meta-analysis of the PEERS program, it was reported that of the studies conducted in the United States (n = 7), all had predominately White, English-speaking participants (Zheng et al., 2021), highlighting the need for more diverse samples.

Individuals of Latine descent comprise 40% of California’s population (US Census Bureau, 2022) and are the fastest growing demographic across the United States, yet significantly underrepresented in autism intervention research (DuBay et al., 2018). The primary goal of the present pilot study was to understand more about the views of the PEERS program in a California-based community that is largely Latine, socioeconomically diverse, and with linguistically diverse parents (e.g., English-speaking, bilingual, and monolingual Spanish-speaking). A secondary goal was to identify whether Latine-specific adaptations were necessary to enhance the cultural relevance of the PEERS program.

Materials and methods

Participants

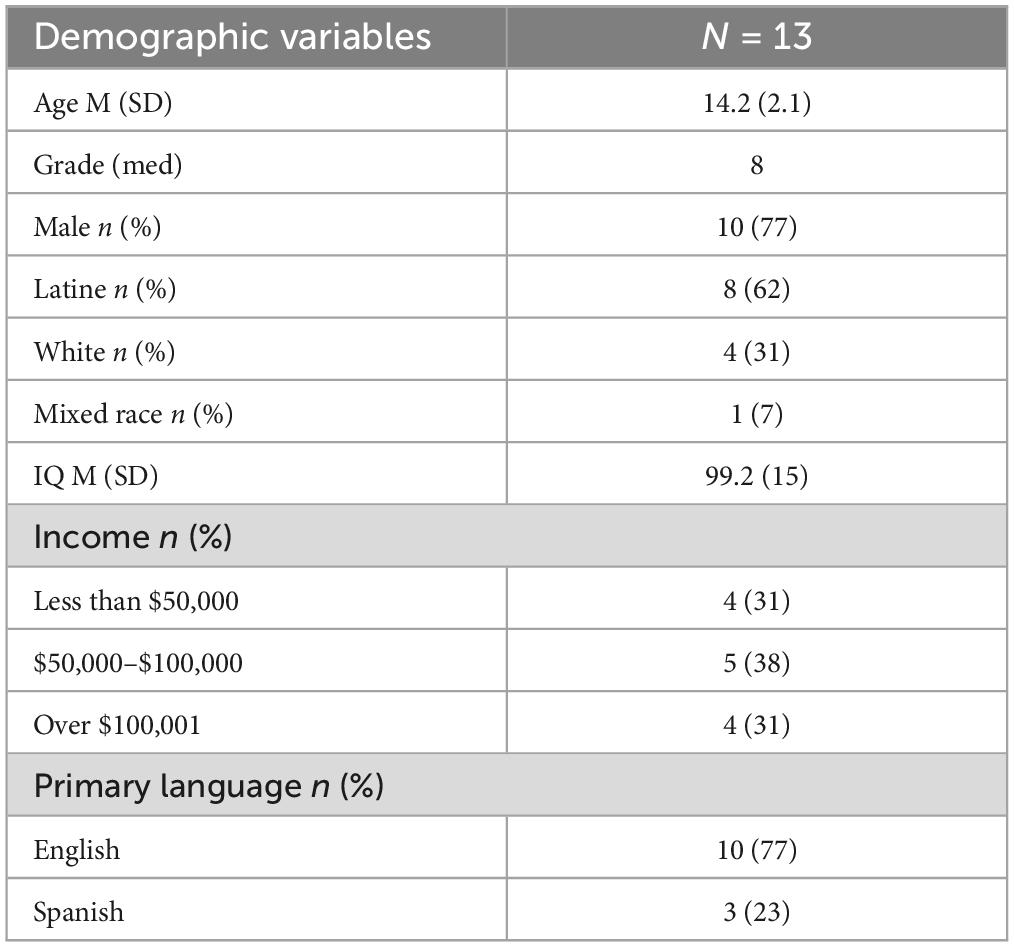

Study participants were 13 English-speaking autistic teens (11 to 17 years, M = 14.17, SD = 2.1; 10 males, 3 female; 8 Latine, 4 White, and 1 biracial Black and Latine) and their linguistically diverse (e.g., English-speaking, bilingual, or monolingual Spanish-speaking) parents (6 mothers, 2 fathers, and 5 mother-father pairs) who completed the 16-week PEERS social skills intervention, post-intervention interview, and 16-week follow up session (number of attended sessions: M = 15 sessions, SD = 1). Because the mother-father pairs sometimes alternated attendance, the term “family” is used to refer to the adult participants for consistency. The current study included two consecutive groups of the 16-week PEERS curriculum. Ten teens were recruited for Group 1 and another 10 were recruited for Group 2; however, the groups experienced attrition with 3 teens dropping from Group 1 and 4 dropping from Group 2. Group 1 contained 2 Spanish-speaking families (1 drop), 4 bilingual families (0 dropped), and 4 English-speaking families (2 dropped). Group 2 contained 3 Spanish-speaking families (1 dropped), and 7 English-speaking families (3 dropped). There were no bilingual families in Group 2. Because the purpose of the study was to ascertain the views of participants who completed the intervention, sample characteristics are only included for participants who completed the full program and follow up session (see Table 1). For detailed information regarding participant characterization, including autism diagnosis confirmation procedures, please review (Veytsman et al., 2022).

Measures

Interview

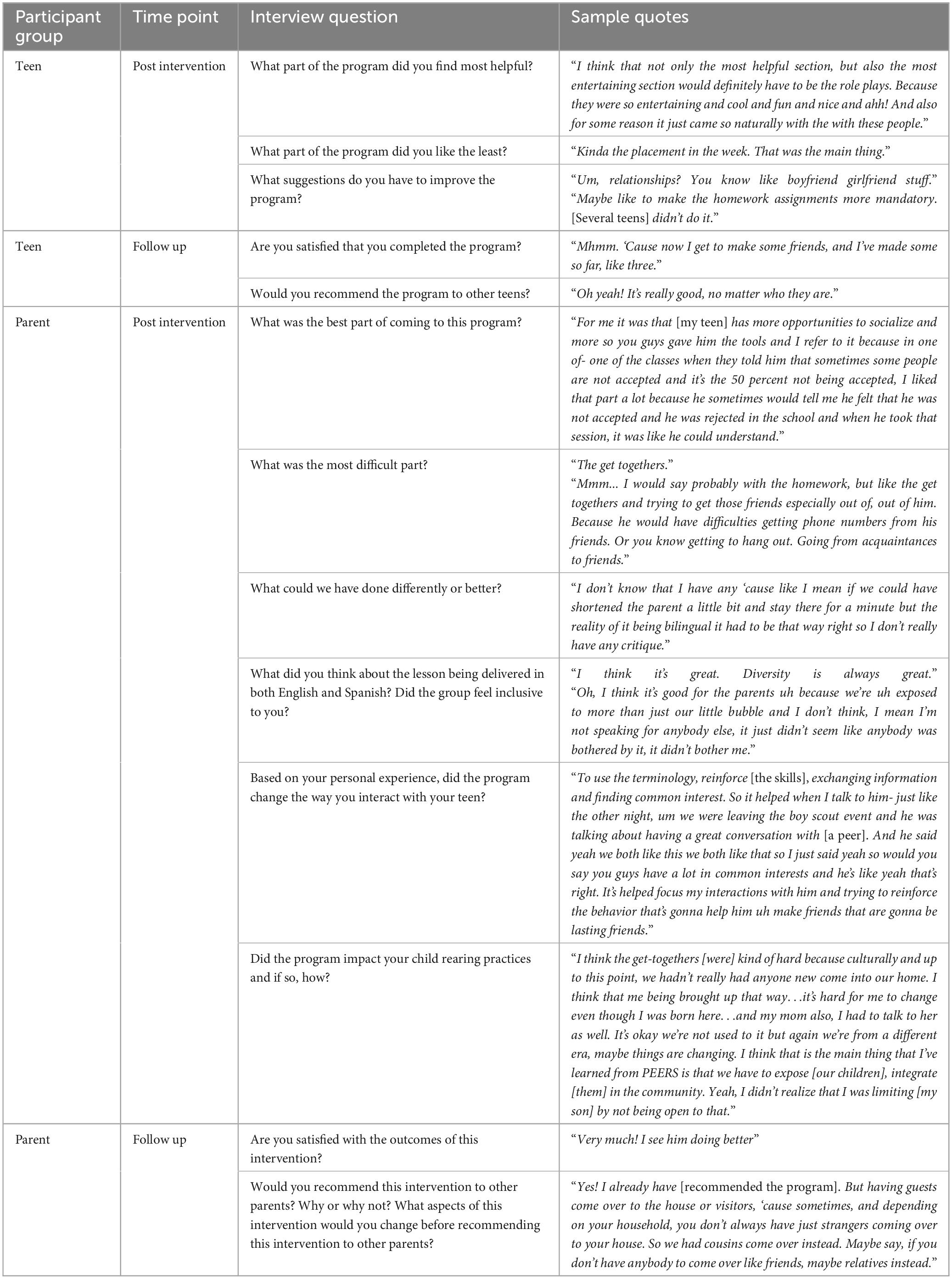

Two semi-structured interviews were conducted for each teen and family participant. The first interview was conducted immediately post-intervention during week 16, and the other was held 16 weeks later during a follow up visit. All interviews were conducted in-person, except for the second groups’ follow up visit, which was conducted via phone due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Caregivers and teens were interviewed separately. The first interview was largely focused on program opinions and suggestions for improvement based on cultural views (e.g., “Based on your personal experience, did the program change the way you interact with your teen?”), while the focus of the second interview was on program effectiveness, overall satisfaction, and recommendations for changes (e.g., “What aspects of this intervention would you change before recommending this intervention to other parents?”). Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish based on participant preference. Interview protocols were adapted from the Gresham and Lopez (1996) framework for post-intervention interviews and reviewed for construct validity by the research team. See Table 2 for interview protocol and sample quotes.

Procedures

Study approval was granted by the university’s Institutional Review Board. Participants were recruited through focus groups, community events, and the distribution of flyers in local school districts, community centers, and on social media platforms.

The current study used the PEERS school-based social skills curriculum (Laugeson et al., 2014). Groups were led by PEERS-certified trainers. Parents and teens met in concurrent but separate groups for 90 min once a week for 16 weeks and received targeted training on key social skills. The teen group was delivered exclusively in English while the parent group was delivered in English and Spanish simultaneously, with additional language support (one-to-one translator) if needed. Due to financial constraints and difficulty in recruiting eligible participants for the groups, it was not feasible to run two monolingual groups (one in English and one in Spanish). Therefore, participants of both primary languages were combined into one group and content was delivered bilingually, with additional supports (e.g., personal translators) provided as needed.

Data analysis

Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed by bilingual research assistants; the transcripts were verified by the bilingual investigator (first author) for accuracy. Transcriptions were analyzed using thematic and content analyses, using Aronson’s (1995) framework for ethnographic interview processing. Prior to analyzing the transcripts, a list of themes and codes were developed by the research team, based on the PEERS literature. The coding team met weekly to review codes and hold intercoder agreement discussions. Due to the small sample size (N = 13), intercoder reliability was calculated for all transcripts and was consistently above 80%, which is the recommended agreement (Campbell et al., 2013).

Findings

Due to the exploratory nature of program implementation (e.g., parent group content delivered bilingually) and the novelty of participant demographics (e.g., primarily Latine, inclusion of monolingual Spanish-speakers), the present study sought to gather information to improve future iterations of the program for culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) populations. Additional sample quotes and interview questions are presented in Table 2.

Teen adaptations

Over half of the autistic teen participants (n = 7) had no recommendations for program changes or adaptations during their follow up interview. The remaining teens provided recommendations that were either program-specific (i.e., content and homework) or not program-specific (i.e., logistics). For example, one suggested that the curriculum include a lesson on relationships and dating (note: a relationships and dating lesson is in the PEERS for Young Adults curriculum but is not in the PEERS for Teens curriculum). Regarding logistical recommendations, one teen suggested, “Maybe put some music on while we wait for the teacher to come in.”

Parent adaptations

At follow up, all parent participants (N = 18; 6 mothers, 2 fathers, and 5 mother-father pairs) responded that they would recommend the program to others. However, only three families would recommend the curriculum as is and ten families had suggestions for overall changes. Although many suggestions were minor (e.g., time of day) one important theme arose concerning program expectations regarding social interactions. Some parents requested allowing social interactions with group members of the intervention and with family members (e.g., cousins), rather than encouraging social interactions with teens outside of the family. Several parents felt that the assignment for teens to make a phone-call and arrange a get-together with a peer outside of the group were too uncomfortable, and particularly difficult for teens without established friendships outside of the group. These parents reported that their teen felt pressured to invite other teens they didn’t know well to their home to complete the assignment, a practice that goes against traditional Latine cultural norms of reserving the home for family or individuals with a developed relationship (Nievar et al., 2008). For example, one bilingual Latine parent dyad said, “Well, he wanted to invite a kid we don’t know, we just know the name, and he wanted to invite him to the house, that would’ve been kind of awkward.” Another parent suggested creating another homework assignment in between the phone calls such as having a get-together with other teens in the program.

When queried about the impact of the program on cultural practices during their post-interview, some families, particularly first- and second-generation, indicated that the program diverged from culturally-specific traditional child-rearing expectations. One bilingual Latine parent described her multigenerational experience:

“I think the get-togethers [were] kind of hard because culturally and up to this point, we hadn’t really had anyone new come into our home. I think that me being brought up that way…it’s hard for me to change even though I was born here…and my mom also, I had to talk to her as well. It’s okay we’re not used to it but again we’re from a different era, maybe things are changing. I think that is the main thing that I’ve learned from PEERS is that we have to expose [our children], integrate [them] in the community. Yeah, I didn’t realize that I was limiting [my son] by not being open to that.”

This parent concluded by explaining that despite the challenges of changing her approach to parenting during the program, by the end of the program she was able to adapt and extend this new social approach across all her children.

Regarding language and mode of delivery, the three monolingual Spanish-speaking families who completed the program were satisfied with the bilingual administration at their post-interview. Two of the Spanish-speaking families would have preferred to participate in a monolingual Spanish-only group, but the remaining family enjoyed being included in the program with translation supports and expressed hope that future iterations of the intervention continue to include more Spanish-speaking participants so that they could be more active participants in research.

One English-speaking family expressed that the content was hard to follow at times, although the rest of the English-speaking families (n = 9) were satisfied with the bilingual administration. Two of the White families suggested that there should be more time spent on providing Spanish translation for the benefit of the Spanish-speaking parents. Even with slight differences in opinion about language delivery, all families who completed the study said that the group felt inclusive, and several enjoyed the experience of interacting with families of different ethnic and language backgrounds. This point is summed best by one participant who shared the following, “I think the thing that binds us together is much stronger than the language differences,” and another parent who shared, “I think it’s great…diversity is always great.” A third parent echoed this sentiment, saying, “I think it’s good for the parents because we’re exposed to more than just our little bubble,” suggesting that having CLD groups can be an added benefit to traditional forms of program delivery.

Discussion

The primary aim of this pilot study was to understand more about the views of the PEERS program in a community that is largely Latine, socioeconomically diverse, and with Spanish-speaking parents. A secondary goal was to identify if Latine-specific adaptations were necessary to enhance the cultural relevance of the PEERS program. Results from interviews revealed that parents and teens were satisfied with the intervention and highlighted the value in the program content, overall experience, and teen group dynamics in the program.

The study also sought to understand if participants had any recommendations for cultural adaptations to improve their experience in the program. Research on cultural adaptations for Latine families is emerging but suggest that simple adaptations can be highly effective (Agazzi et al., 2010). For example, in reference to a different parent training program, Agazzi et al. (2010) found that simplifying language and avoiding technical psychological terms or complex concepts (e.g., positive vs. negative reinforcement) increased acceptance by Spanish-speaking caregivers. In the present study, parents who identified as first- or second-generation Latine reported a greater impact on traditional cultural parenting practices. Specifically, the parents were concerned about the implications of inviting non-familial teens into the home for get-togethers (a term used in PEERS to represent the gathering of teens for socializing), which is a homework assignment of the program. Although traditional delivery of the PEERS program (e.g., Laugeson et al., 2009) does not recommend get-togethers with other group members (to reduce the possible negative impact on group dynamics, such as the formation of “cliques”), several parents mentioned the suggestion of adapting the homework criteria to allow for pre-arranged get-togethers with group members or get-togethers with family members. It is possible that this finding may be related to the Latine concept of “familismo,” a cultural value that refers to a perceived obligation to provide support to extended family, reliance on relatives for help and support, and emphasis on interdependency (Marin and Marin, 1991). Thus, making an allowance for Latine families to host get-togethers with family members may increase homework completion, program cultural relevance, and overall satisfaction. In addition, it may be important to spend more time during group sessions emphasizing public gatherings as acceptable, rather than focusing on proper host techniques for Latine families to decrease stress around inviting non-familial peers into the home, so that diverse participants are not forced to extend outside of their values and comfort zone to see progress. By implementing small meaningful changes in the curriculum, such as allowing get-togethers with family members or other group members, the needs of CLD families can be balanced and still promote social growth in teen participants.

While there is limited research on the effectiveness of bilingual interventions (DuBay et al., 2018), parents in the present study endorsed satisfaction with this non-traditional program delivery, which suggests that fully bilingual groups can likely be effective. Thus, even in predominately White areas, researchers should strive to include Latine families even if they do not speak English. By waiting to recruit exclusively Spanish-speaking groups, monolingual Latine families miss out on participating in interventions and researchers miss out on increasing the diversity of their samples.

Limitations and future directions

There are a few notable limitations. First, this pilot study had a small sample size, so the findings should be interpreted with caution. This warrants future replications with a larger sample size that continues to incorporate CLD participants. The study also faced fairly high rates of attrition in both groups, with a total of 7 participants dropping across both groups by the end of the program. Although we did not conduct interviews with these participants, we did ask why they dropped the program. The most common responses included teen mental health concerns or hospitalization, group appropriateness, and logistics of attendance (e.g., parents with multiple children and no reliable transportation). Additionally, the families who dropped were from a range of backgrounds (i.e., both White and Latine and different language backgrounds), indicating that there was likely a complex interplay of factors (e.g., race, ethnicity, SES, personal circumstances) that led to families dropping out of the study. Future studies may wish to understand the predictive role of factors that influence participant attrition by conducting interviews with the autistic participants who drop out. Other sites may also consider implementing preventative measures such as providing childcare, hosting the groups in a community building (as opposed to a university campus), or offering virtual or telehealth group options for families with transportation challenges. Finally, future providers may consider exploring motivational interviewing or similar strategies to decrease dropout and increase intervention attitudinal investment, as this has demonstrated feasibility for Latine participants (Añez et al., 2008). Despite these limitations, this paper contributes to a growing body of literature highlighting both the importance of including underrepresented demographic groups in research and factoring in cultural adaptations to increase validity of interventions previously normed on White affluent populations.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because with such a small sample size and sensitive qualitative data generated, we do not wish to make the data publicly available to protect the participants. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to bWFydGFubm1AaXUuZWR1.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of California Riverside Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

AM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EV: Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EB: Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JF: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by a grant from the Bezos Foundation.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the teens and parents who participated in this study for their time and dedication to this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agazzi, H., Salinas, A., Williams, J., Chiriboga, D., Ortiz, C., and Armstrong, K. (2010). Adaptation of a behavioral parent-training curriculum for Hispanic caregivers: HOT DOCS Español. Infant Mental Health J. 31, 182–200. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20251

Añez, L. M., Silva, M. A., Paris, M., and Bedregal, L. E. (2008). Engaging Latinos through the integration of cultural values and motivational interviewing principles. Professional Psychol. Res. Pract. 39, 153–159. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.39.2.153

Aronson, J. (1995). A pragmatic view of thematic analysis. Qual. Rep. 2, 1–3. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/1995.2069

Campbell, J. L., Quincy, C., Osserman, J., and Pedersen, O. K. (2013). Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociol. Methods Res. 42, 294–320. doi: 10.1177/0049124113500475

DuBay, M., Watson, L. R., and Zhang, W. (2018). In search of culturally appropriate autism interventions: perspectives of Latino caregivers. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 1623–1639. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3394-8

Gresham, F. M., and Lopez, M. F. (1996). Social validation: a unifying concept for school-based consultation research and practice. School Psychol. Q. 11, 204–227. doi: 10.1037/h0088930

Laugeson, E. A., Ellingsen, R., Sanderson, J., Tucci, L., and Bates, S. (2014). The ABC’s ofteaching social skills to teens with autism spectrum disorder in the classroom: the UCLA PEERS program. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 44, 2244–2255. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2108-8

Laugeson, E. A., and Frankel, F. (2010). Social Skills for Teenagers with Developmental and Autism Spectrum Disorders: the PEERS Treatment Manual. New York: Routledge.

Laugeson, E. A., Frankel, F., Gantman, A., Dillon, A. R., and Mogil, C. (2012). Evidence-based social skills training for teens with autism spectrum disorders: the UCLA PEERS program. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 42, 1025–1036. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1339-1

Laugeson, E. A., Frankel, F., Mogil, C., and Dillon, A. R. (2009). Parent-assisted socialskills training to improve friendships in teens with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 39, 596–606. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0664-5

Laugeson, E. A., Gantman, A., Kapp, S. K., Orenski, K., and Ellingsen, R. (2015). A randomized controlled trial to improve social skills in young adults with autism spectrum disorder: the UCLA PEERS program. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 45, 3978–3989. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2504-8

Marin, G., and Marin, B. V. (1991). Research with Hispanic Populations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Nievar, M. A., Jacobson, A., and Dier, S. (2008). Home visiting for At-risk preschoolers: a successful model for latino families. Paper Presented at the 70th Annual Meeting of the National Council on Family Relations. Little Rock, AR

Schohl, K. A., Van-Hecke, A. V., Carson, A. M., Dolan, B., Karst, J., and Stevens, S. (2014). A replication and extension of the PEERS intervention: examining effects on social skills and social anxiety in teen with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 44, 532–545. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1900-1

US Census Bureau (2022). QuickFacts: California [internet]. Available online at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/CA (accessed March 27, 2023).

Van Hecke, A. V., Stevens, S., Carson, A. M., Karst, J. S., Dolan, B., Schohl, K., et al. (2015). Measuring the plasticity of social approach: a randomized controlled trial of the effects of the PEERS intervention on EEG asymmetry in teens with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 45, 316–335. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1883-y

Veytsman, E., Baker, E., Martin, A. M., Choy, T., Blacher, J., and Stavropoulos, K. (2022). Perceived and observed treatment gains following PEERS: a preliminary study with Latine teens with ASD. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 53, 1175–1188. doi: 10.1007/s10803-022-05463-9

Keywords: culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD), autism spectrum, Latine/Hispanic, cultural adaptation, social skills (training), PEERS program

Citation: Martin AM, Blacher J, Veytsman E, Baker E, Fodstad J and Meltzoff K (2024) Brief report: cultural adaptations for the PEERS program for Latine families. Front. Educ. 9:1425378. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1425378

Received: 29 April 2024; Accepted: 06 September 2024;

Published: 20 September 2024.

Edited by:

Kelsey Dickson, San Diego State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Bonnie Kraemer, San Diego State University, United StatesTeymour Rahmati, Gilan University of Medical Sciences, Iran

Kristin Lems, National Louis University, United States

Jamelle Salomon, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, United States

Copyright © 2024 Martin, Blacher, Veytsman, Baker, Fodstad and Meltzoff. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ann Marie Martin, bWFydGFubm1AaXUuZWR1; orcid.org/0000-0002-1705-2275

Ann Marie Martin

Ann Marie Martin Jan Blacher1

Jan Blacher1 Elizabeth Baker

Elizabeth Baker