- 1Department of Primary Education, University of the Aegean, Rhodes, Greece

- 2Department of Primary Education, University of Western Macedonia, Florina, Greece

Sexually inclusive primary education, namely a school environment that uses inclusive practices toward sexual minorities contributes to students’ psychological and learning adaptation. Therefore, it is essential primary school stakeholders’ perspective on sexually inclusive education to be explored, since this could facilitate the effective implementation of related prevention/awareness programs targeted at students. Nevertheless, teachers’ and parents’ related perspective, as main school stakeholders, as well as the predictive value of their homophobic prejudice and moral disengagement remain an under-investigated research field. The present study examined comparatively teachers’ and parents’ perspective on sexually inclusive primary education. Furthermore, the predictive role of homophobic prejudice and moral disengagement was investigated for each subgroup. Overall, 249 primary school teachers (78% women) of the fifth and sixth grades from randomly selected Greek public schools and 268 parents (81% mothers) of children who attended the above grades of the participating schools completed an online self-reported questionnaire on the variables involved. In general, participants expressed a relatively conservative perspective on sexually inclusive primary education, with teachers’ perspective being less inclusive than that of the parents. Teachers’ related perspective was predicted negatively mainly by homophobic prejudice and secondarily by moral disengagement. Parents’ corresponding perspective was predicted negatively only by moral disengagement. Despite the differentiated perspective between the two subgroups, the findings imply that both teachers and parents need to attend prevention/awareness actions regarding students’ sexual diversity and their school inclusion. Within these actions, differentiated experiential activities could be implemented for teachers and parents to combat homophobic prejudice and/or moral disengagement.

1 Introduction

The diversity of the student population concerns not only their multicultural background but also their sexual orientation (Klocke, 2024). In general, a school environment that uses practices inclusive toward students’ diversities (e.g., sexual orientation), contributes significantly to students’ mental health and subsequently to their academic outcomes (Ioverno, 2023; Woolweaver et al., 2023). Therefore, it is essential for teachers to adopt sexually inclusive teaching strategies in the school environment, that is, behaviors of respect and sensitization toward students belonging to sexual minorities. These sexually inclusive behaviors contribute to students’ healthy interpersonal relationships and well-being, especially for students who belong to sexually minority groups, such as gays, lesbians or bisexuals (Mayo, 2022). The same applies to parents whose sexually inclusive behavior (receptivity and respect for sexual diversity) cultivates in their children a more tolerant attitude toward issues of diversity in general (Katz-Wise et al., 2022). Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 1991), one parameter that predicts individuals’ intention to engage in a behavior and, subsequently the manifestation of this behavior (e.g., sexually inclusive practices) is individuals’ perceptions/attitudes regarding this behavior/issue. In other words, individuals’ actions regarding an issue (sexually inclusive practices) are significantly directed by their related perceptions/attitudes (e.g., perceptions on sexually inclusive education). Consequently, investigating in-service teachers’ and parents’ perspective regarding sexually inclusive education, as primary stakeholders of the school community, may reveal the extent of their readiness toward the adoption of relevant practices at school and subsequently highlight the necessity of launching prevention/awareness actions for them regarding students’ sexual diversity. Moreover, given that primary education is an optimal time to introduce prevention and awareness initiatives (Sprague and Walker, 2021), it is crucial to explore the attitudes of primary school teachers and parents of primary school students toward sexually inclusive education.

The international literature reveals that while numerous studies have explored teachers’ and parents’ views on sex education broadly and its incorporation into the school curriculum (e.g., Berne et al., 2000; Ramiro and Matos, 2008; Runhare et al., 2016; Shin et al., 2019; Zhuravleva and Helmer, 2024), there is a scarcity of research explicitly addressing their perceptions on sexual diversity within primary education (sexually inclusive primary education). Regarding teachers, research on secondary education indicates that secondary school teachers often lack awareness about sexual diversity (Kwok, 2019). They may overlook or sidestep discussions related to students’ homosexuality, and when such issues do arise, they tend to endorse the concept of ‘compulsory heterosexuality’ (Francis, 2012). Generally, based on secondary school teachers’ self-reports, a less friendly environment for students with diverse sexual orientations seems to be reflected (Aguirre et al., 2021). Similarly, the limited research carried out in primary education has demonstrated that teachers often exhibit an indifferent and evasive attitude toward students’ sexual diversity, expressing uncertainty about handling such matters in the school environment (Souza et al., 2016; Van Leent, 2017). Consequently, according to existing studies, both secondary and primary school teachers appear to have a less favorable view toward sexually inclusive education.

The perspective of parents on this issue has been somewhat explored. However, most existing research primarily concentrates on parents of secondary school students. These studies suggest that parents of adolescents generally favor the inclusion of sexual diversity topics in their children’s education (McCormack and Gleeson, 2010; Ullman et al., 2022). In contrast, a more recent study has shown that parents seem to believe that the inclusion of sexual diversity issues into the school curriculum could be “confusing” for adolescents, who are not very mature and could be easily influenced negatively by these issues (Ferfolja et al., 2023). To the best of our knowledge, the study by Van Leent and Moran (2023) is the only recent research focusing solely on parents of primary school children. The parents participating in this study expressed that topics related to gender and sexual diversity should be integrated into the primary school curriculum (Van Leent and Moran, 2023). As a result, unlike the somewhat unclear stance observed among parents of secondary school children, the findings from parents of primary school children appear to indicate a more positive and inclusive viewpoint on this matter.

Nevertheless, the above findings imply that the perspective on sexually inclusive education is significantly under-examined for primary school teachers. Furthermore, a somewhat inconsistent research picture arises regarding parents’ related perceptions, while the fact that most findings come from parents of children in secondary schools does not allow us to draw safe conclusions for the corresponding perspective of parents of primary school children. Also, according to the authors’ knowledge, no study examines comparatively teachers’ and parents’ perspective on sexually inclusive primary education. A related study could highlight a necessity for intensifying possibly differentiated awareness actions for these two stakeholders of the primary school community.

When analyzing the views of school community stakeholders on sexually inclusive primary education, it is crucial to identify sex-related factors that could pose risks to or protect this perspective. Someone would expect that homophobic prejudice, namely the prejudicial attitudes toward individuals with diverse sexualities, such as gays and lesbians (Herek, 2000), could be considered as an aggravating sex-related factor which is associated with a less inclusive perspective on sexually inclusive education. However, no related research findings are identified in international literature. The only available studies which concern preservice (e.g., Foy and Hodge, 2016; Heras-Sevilla and Ortega-Sánchez, 2020) and in-service teachers (e.g., D’Urso et al., 2023) but not parents, investigate their homophobic attitudes only in relation to their demographic and personality traits, revealing relatively conservative beliefs, but not in relation to their perspective on sexually inclusive education. Although it would be expected that teachers’ and parents’ homophobic prejudice predisposes them negatively toward sexually inclusive primary education, it needs to be tested empirically.

Furthermore, for decades, there has been a debate about the morality of individuals with diverse sexual orientations (e.g., Brooke, 1993; Jones and Kwee, 2005). Therefore, it is not surprising that moral disengagement, namely ‘the deactivation of moral control and to the justification of one’s transgressions to preserve self-esteem and avoid punishment’ (Camodeca et al., 2019, p. 505), has been reported as a contributor to sexually non-inclusive behaviors among adolescents, such as homophobic bullying (Camodeca et al., 2019). Someone would expect that moral disengagement, as a morality-related factor, could operate as an aggravating factor for individuals’ inclusive perspective on sexual minorities. Nevertheless, there are no evidence-based findings about this issue, and especially about the contributing role of teachers’ and parents’ moral disengagement in their perspective on sexually inclusive education.

A related study focused on the role of teachers’ and parents’ homophobic prejudice and moral disengagement in their perspective under examination could imply the following: The necessity of school prevention programs for awareness about sexual inclusivity to be enriched, not only with issues related to students’ sexual diversity in general but also with differentiated and specific activities aimed at enhancing less homophobic attitudes and/or more moral consciousness. In this way, teachers’ and parents’ more tolerant perspective on this issue could be achieved.

This study aims to compare the perspective of teachers and parents on sexually inclusive primary education. It also seeks to determine the influence of homophobic prejudice and moral disengagement on their viewpoints. Specifically, the study investigated:

(1) Differences in perspective on sexually inclusive primary education between teachers and parents.

(2) Τhe predictive role of homophobic prejudice in the perspective on sexually inclusive primary education, separately for teachers and parents.

(3) Τhe predictive role of moral disengagement in the perspective on sexually inclusive primary education, separately for teachers and parents.

According to the available related findings, we were able to hypothesize the following:

(1) Teachers’ perspective on sexually inclusive primary education is less positive than parents’ corresponding perspective (Hypothesis 1; Souza et al., 2016; Van Leent, 2017; van Leent and Moran, 2023).

(2) Teachers’ homophobic prejudice predicts negatively their perspective on sexually inclusive primary education (Hypothesis 2; D’Urso et al., 2023). No corresponding hypothesis was stated for parents due to the lack of related findings.

(3) Regarding the role of teachers’ and parents’ moral disengagement in their perspective on sexually inclusive primary education no hypotheses were set due to the lack of related findings.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sample

Following the G*Power analysis (detailed in subsection 2.4), the study’s participant pool consisted of 249 primary school teachers [78% female (N = 194), Mage = 43.3, SD = 1.02] who taught fifth and sixth grades1. These participants were from public schools (with a 29% response rate) situated in economically varied districts of Athens and Thessaloniki, the two largest cities in Greece. Teachers from these grades were selected because the initial introduction to topics concerning the two sexes (a parameter partially relevant to the studied issue) occurs within the curriculum of fifth and sixth grades (Pedagogical Institute, n.d.). Also, the study included 268 parents [81% mothers, (Ν = 217), Mage = 40.8, SD = 0.93] whose children attended the fifth and sixth grades of the participating schools. The over-representation of females in both teachers and parents, which is usually common in educational professions and in responding to school research calls in Greece, did not allow, from a statistical point of view, to test gender-based differences safely in the variables involved. Finally, the pilot phase of the study was conducted in 23 teachers [61% females, (Ν = 14), Mage = 41.9, SD = 0.91] and in 29 parents [64% mothers, (Ν = 19), Mage = 39.5, SD = 1.14], who were not included in the main sample.

2.2 Questionnaire

Both teachers and parents answered online a self-reported questionnaire, which included initial demographic questions (e.g., gender, age) and the following three main scales:

2.2.1 Perspective on sexually inclusive education

Participants’ perspective on sexually inclusive primary education was examined through the Attitudes Toward the Inclusion of Trans and Gender Diverse Students Measure (Goff, 2014). The measure includes 19 statements (10 are reverse scored) regarding school-inclusive strategies for students with diverse sexual orientation (e.g., “It is the responsibility of school staff to stop others from making negative comments based on gender identity or expression,” “Positive representations of trans and gender diverse people should be included in the curriculum whenever possible,” “School staff should receive training on how to intervene against gender-based student harassment”). The statements, which form a unidimensional structure, are answered on a five-point Likert-type scale (from 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree). Higher scores on the scale denote higher perceived sexually inclusive primary education (Goff, 2014). Testing the measure’s psychometric properties, a principal component analysis was applied with the main component method and Varimax-type rotation for both teachers (KMO = 0.902, Bartlett Chi-square = 2487.982, p < 0.001) and parents (KMO = 0.874, Bartlett Chi-square = 1847.004, p < 0.001) to ensure the same factorial structure in each case. In both cases, one factor emerged with eigenvalue >1.0 and significant interpretive value: teachers (Factor 1, explaining 65.88% of the total variance - loadings from 0.474 to 0.791), parents (Factor 1, explaining 69.12% of the total variance - loadings from 0.458 to 0.783). In both cases, the internal consistency indexes were good (α = 0.855 and α = 0.872 for teachers and parents, respectively).

2.2.2 Homophobic prejudice

Participants’ homophobic prejudice was investigated through the revised Attitudes Toward Lesbians and Gay Men Scale (ATLG-R; Herek, 2000). The scale includes 13 statements (6 are reverse scored) regarding prejudicial attitudes toward individuals with sexual diversity (e.g., “Male homosexuality is merely a different kind of lifestyle that should not be condemned,” “Female homosexuality is a perversion”). The statements, which form a unidimensional structure, are answered on a five-point Likert-type scale (from 1 = Absolutely disagree to 5 = Absolutely agree). Higher scores on the scale denote higher homophobic prejudice (Herek, 2000). Testing the measure’s psychometric properties, a principal component analysis was applied with the main component method and Varimax-type rotation for both teachers (KMO = 0.841, Bartlett Chi-square = 1765.011, p < 0.001) and parents (KMO = 0.822, Bartlett Chi-square = 1183.182, p < 0.001) to ensure the same factorial structure in each case. In both cases, one factor emerged with eigenvalue >1.0 and significant interpretive value: teachers (Factor 1, explaining 69.02% of the total variance - loadings from 0.405 to 0.662), parents (Factor 1, explaining 65.43% of the total variance - loadings from 0.497 to 0.756). In both cases, the internal consistency indexes were good (α = 0.868 and α = 0.841 for teachers and parents, respectively).

2.2.3 Moral disengagement

Participants’ moral disengagement was tested through the Moral Disengagement Scale (Caprara et al., 1995). The scale includes 14 statements regarding an individual’s tendency to justify unethical behaviors/attitudes due to the lack of moral control (e.g., “People who get teased do not really get too sad about it”). The statements, although they reflect different mechanisms, form a unidimensional structure, as in previous studies (e.g., Gini, 2006), and are answered on a five-point Likert-type scale (from 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree). Higher scores on the scale denote higher moral disengagement (Caprara et al., 1995). Testing the measure’s psychometric properties, a principal component analysis was applied with the main component method and Varimax-type rotation for both teachers (KMO = 0.911, Bartlett Chi-square = 3482.187, p < 0.001) and parents (KMO = 0.894, Bartlett Chi-square = 2798.014, p < 0.001) to ensure the same factorial structure in each case. In both cases, one factor emerged with eigenvalue >1.0 and significant interpretive value: teachers (Factor 1, explaining 61.45% of the total variance) and parents (Factor 1, explaining 60.08% of the total variance). In both cases, the internal consistency indexes were good (α = 0.848 and α = 0.839 for teachers and parents, respectively).

2.3 Procedure

Upon approval of the study by the Greek Institute of Educational Policy (Φ11/19442/Δ3, 02/09/2023), the principals of the randomly selected schools were emailed, asking for them to forward the research approval and the link to the questionnaire to the teachers of the fifth and sixth grades as well as to parents whose children attended these grades. The questionnaire was constructed via an online platform (SurveyMonkey) ensuring the concealment of participants’ computer IP addresses. Through the link, participants had access to an informed consent form and the scales related to the variables examined. Participants’ answers were automatically entered into the platform. The completion of the questionnaire was estimated at about 10–15 min. This procedure was followed in the pilot (September 2023) and main study (October 2023–February 2024), meeting the research ethical rules.

2.4 Statistical analyses

Without any missing cases, different statistical analyses were used. For each analysis an a priori power analysis of sample size was performed, using G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., 2007), with power (1-β) of 85%, medium effect (f = 0.05), and an alpha error of probability α = 0.05. Differences in perspective on sexually inclusive primary education between teachers and parents was examined via independent samples T-test (Noncentrality parameter δ = 2.47, Critical t = 2.11, df = 89, Actual power: 0.84, required sample per group: Ν = 202). The dyadic relationships among the variables were investigated through the Pearson (Pearson r) correlations (Noncentrality parameter δ = 2.38, Critical t = 2.82, df = 85, Actual power: 0.84, required sample: Ν = 208). Τhe predictive role of participants’ homophobic prejudice and moral disengagement in their perspective on sexually inclusive primary education (dependent variable) was explored via Multiple Linear Regression using the enter method (Noncentrality parameter δ = 3.09, Critical t = 2.41, df = 83, Actual power: 0.85, required sample: Ν = 205).

3 Results

3.1 Differences between teachers’ and parents’ perspective on sexually inclusive primary education

The findings indicated a significant difference concerning the perspective on sexually inclusive education between teachers and parents, t (38) = 4.33, p = 0.001. Teachers demonstrated a less inclusive stance (M = 2.01, SD = 1.28) compared to parents (M = 2.33, SD = 1.09). However, it is important to point out that, within the five-point scale used for responses, the overall attitudes of both teachers and parents toward this matter are below the midpoint average. Indicatively, the relevant school strategies that were supported in slightly higher percentages by parents were the following: It is the responsibility of school staff to stop others from making negative comments based on gender identity or expression (71%), School districts should allow trans and gender diverse students to participate in sports on the basis of their gender identity, not assigned sex (65%), Positive representations of trans and gender diverse people should be included in the curriculum whenever possible (59%). The corresponding school strategies were supported in lower percentages by teachers (53, 50, and 44%).

3.2 Correlations between the variables

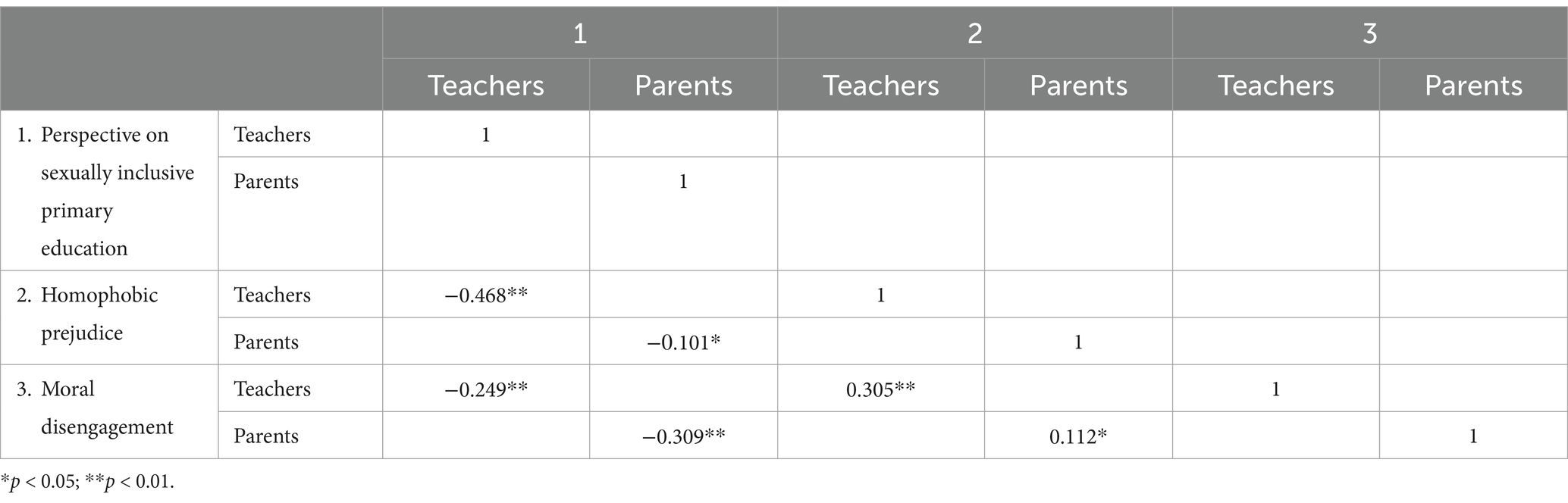

The correlation analyses were run separately for both teachers and parents to ensure the same pattern of correlations among the variables in each case. Based on Table 1, in each case, the perspective on sexually inclusive primary education was correlated negatively with homophobic prejudice and moral disengagement, while homophobic prejudice and moral disengagement were correlated positively with each other. It should be mentioned that in the case of teachers most of the correlations were stronger than in the case of parents.

3.3 The predictive role of homophobic prejudice and moral disengagement in the perspective on sexually inclusive primary education

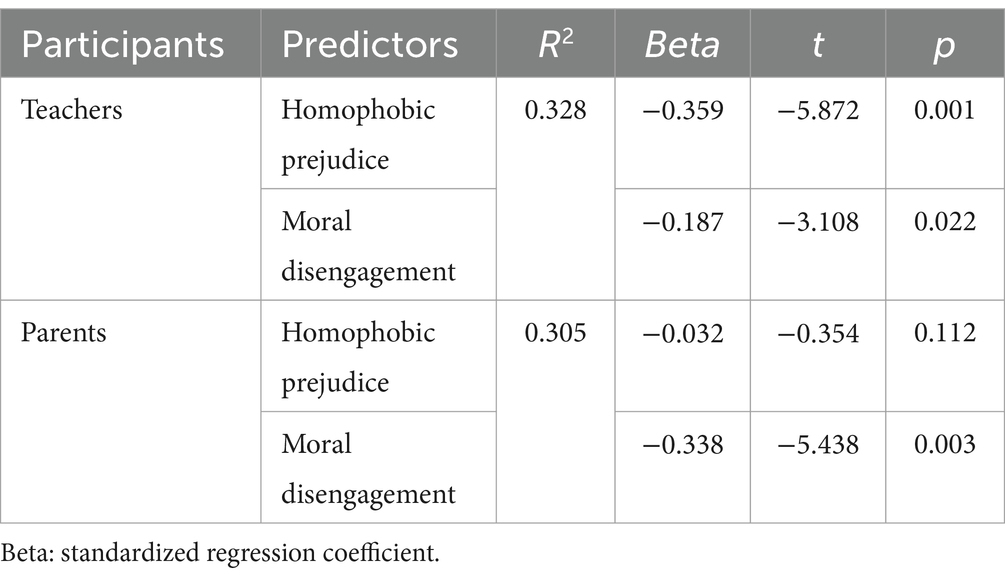

According to Table 2, it was found for teachers that primarily their homophobic prejudice and secondarily their moral disengagement predicted negatively their perspective on sexually inclusive education. Regarding parents, it seemed that only moral disengagement proved a negative predictor of their corresponding perspective.

Table 2. The predictive role of homophobic prejudice and moral disengagement in the perspective on sexually inclusive primary education.

4 Discussion

The study undertook a comparative examination of teachers’ and parents’ views on sexually inclusive primary education, assessing within each group the impact of homophobic prejudice and moral disengagement on their receptiveness to this perspective.

The research yielded four primary findings. Firstly, even with the distinctions between the two groups, their overall perspective remained below the midpoint (2.5) on the evaluative scale, indicating a widespread hesitancy among Greek parents and teachers toward embracing sexually inclusive primary education. This hesitance is likely influenced, at least partially, by the broader context of Greek society, which predominantly reflects conservative views on matters of sexual diversity (Iliadou, 2020; Karadimos, 2022). This finding could be considered awakening for the whole school community since the main school stakholders, such as teachers and parents, who support practices inclusive toward students’ sexual diversities positively affect students’ well-being and their learning (Ioverno, 2023; Woolweaver et al., 2023).

Secondly, aligning with Hypothesis 1, the findings showed that primary school teachers display a less favorable attitude toward sexually inclusive primary education than parents. Teachers were notably less inclined to engage in proactive behaviors supportive of sexually inclusive educational strategies. This encompasses a lesser sense of duty to counter negative comments regarding students’ gender identity or expression, a reduced willingness to allow students to participate in sports activities congruent with their gender identity, and weaker support for curricula that positively represent diverse sexual orientations. The reluctance of participating teachers toward sexually inclusive primary education reflects earlier findings, which identified similar attitudes among both primary school (Souza et al., 2016; Van Leent, 2017) and secondary school teachers (Aguirre et al., 2021; Francis, 2012; Kwok, 2019). These studies noted a tendency among teachers to shy away from discussions on homosexuality, displaying a preference for heterosexual norms. Despite primary school teachers receiving training on student diversity during their undergraduate programs (e.g., Department of Primary Education, University of the Aegean, 2023–2024), there appears to be a gap between their theoretical knowledge on sexual diversity and their willingness or ability to implement sexually inclusive strategies in the classroom. This hesitation might stem from a clash with their existing beliefs or a lack of confidence in executing such strategies effectively.

The study highlights that teachers’ reluctance to adopt sexually inclusive primary education is predominantly influenced by their homophobic tendencies, aligning with Hypothesis 2. Such biased attitudes significantly limit the adoption of supportive measures for students of diverse sexual orientations (D’Urso et al., 2023). In Mediterranean contexts like Greece, where educational systems may exhibit conservative views toward sexual diversity (Ioverno et al., 2016; Karadimos, 2022), such prejudices are particularly pronounced, further hampering the move toward sexually inclusive school environments.

Notably, homophobic prejudice emerged as the primary barrier to teachers’ acceptance of sexually inclusive education, overshadowing the role of moral disengagement. This suggests that, while moral disengagement has been identified as a factor in homophobic bullying among students (Camodeca et al., 2019), its impact on teachers’ inclinations toward inclusive practices is secondary. This is reinforced by research indicating that ethnic prejudice can indirectly foster non-inclusive behaviors through moral disengagement (Ιannello et al., 2021), hinting at a more intricate interplay between these factors. Therefore, it appears that moral disengagement, though significant, plays a more mediated role in influencing teachers’ attitudes toward sexually inclusive education, primarily exacerbating the effects of homophobic prejudice. Future research is needed to more definitively map out these dynamics and confirm the observed patterns within the context of teacher attitudes toward sexually inclusive education.

Thirdly, parents demonstrated a relatively more open stance toward sexually inclusive primary education. This more open stance aligns with previous research indicating that both primary (Van Leent and Moran, 2023) and secondary school children’s parents (McCormack and Gleeson, 2010; Ullman et al., 2022) generally favor integrating gender and sexual diversity into their children’s academic curriculum. This inclination among participating parents may be partially attributed to a natural parental desire to safeguard their children’s physical and psychological well-being, whether at home or elsewhere (Brooks, 2023; Grille, 2014). The predominance of mothers within the study’s participant pool might have further emphasized a more tolerant and supportive view toward sexually inclusive educational practices among the parents involved. Undoubtedly, future related studies with a more equally gender-distributed sample of parents could either verify or challenge these parental attitudes.

Fourthly, an intriguing finding emerged regarding how parents’ (notably mothers’) perspective on sexually inclusive education is shaped by their level of moral disengagement and homophobic prejudice. Similar to teachers, parents’ diminished moral judgment regarding unethical behaviors, namely moral disengagement, fosters a more conservative viewpoint toward sexually inclusive education strategies. Yet, a notable difference between the two groups emerges: parents’ views on homophobic prejudice do not play a significant role in shaping their stance on sexually inclusive education. This variation reflects the initial, weak correlation yielded between parents’ moral disengagement and their attitudes toward sexually inclusive primary education, possibly suggesting a complex interplay of these factors.

This finding challenges traditional assumptions and invites a deeper exploration into the complex interplay of societal norms, personal beliefs, and educational values. Firstly, this observation may reflect a broader societal shift toward more accepting attitudes concerning sexual orientation and identity. As communities become more inclusive, parents recognize the importance of mirroring these values within educational settings, underscoring the belief that all children deserve an environment of understanding and acceptance. Moreover, there appears to be a nuanced distinction made by parents between their personal prejudices and their beliefs about educational content. This separation suggests a mature approach toward education—one that prioritizes creating a non-discriminatory and supportive learning environment over personal biases. It’s a testament to the idea that, within the school gates, the focus should heavily lie on fostering respect and tolerance among students (Frumkin et al., 2006; Kadyro and Mullabaeva, 2023). Mothers, especially, might play a critical role in this dynamic. The inherent desire to shield children from harm could override personal prejudices, leading to a stronger endorsement of inclusive education practices (Brooks, 2023; Grille, 2014). This protective instinct aligns with the recognition that an inclusive curriculum could play a vital role in preventing bullying and creating a safer school environment for all students (Forlin and Chambers, 2003; Sayfulloevna, 2023). However, it’s also worth considering that parents might not be fully aware of their implicit biases. This lack of awareness or acknowledgement of subtle prejudices could contribute to the underestimation of their impact on attitudes toward sexually inclusive education. It’s a reminder of the complex nature of prejudice and the need for ongoing self-reflection and education. Lastly, the influence of social desirability cannot be overlooked (Van de Mortel, 2008). In research contexts, parents might consciously or unconsciously align their responses with what is socially acceptable, potentially underreporting their true prejudices. This highlights the need for careful consideration of how we interpret data from surveys and studies on sensitive topics. Based on the above, it could be partially explained why parents’ homophobic prejudice did not emerge as a potential negative contributor to their perspective on sexually inclusive primary education.

Due to specific limitations (small sample size, unequal gender-based distribution of the sample, possibly socially acceptable responses, restriction to quantitative data) future research directions could be outlined. Indicatively, studies conducted on a larger sample of teachers and parents in primary education, combining both quantitative and qualitative data (e.g., semi-structured interviews) and applying mediation analyses could enhance the present findings highlighting possibly more complex patterns of relationships between predictors (homophobic prejudice, moral disengagement) and participants’ perspective on sexually inclusive primary education. However, the study informs about the somehow differentiated perspective between teachers and parents, highlighting corresponding contributors. These findings imply the necessity of intensifying awareness actions for the main stakeholders of the primary school community (teachers, parents) regarding students’ sexual diversity and their inclusion in the school environment. These actions could be seen as an integral part of a broader curriculum-based comprehensive sexuality education, which aims at promoting in the school community attitudes and values respectful of individuals’ sexual rights (Mark et al., 2021) as well as knowledge about sexual health education (Ng et al., 2024). Within these actions, differentiated experiential activities for teachers and parents could be implemented aimed at combating homophobic prejudices and/or strengthening moral consciousness. These initiatives could be organized by school psychologists and school counselors or by official Educational and Counseling Centers, such as KE.D.A.S.Y. in Greece. In these centers the interdisciplinary scientific personnel may collaborate with the schools in order to train and sensitize teachers, administrators and parents toward current psycho-educational issues such as sexually inclusive education.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because, due to the sensitive nature of the research topic, the participating teachers and parents were assured raw data and material would remain confidential and would not be shared. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Thanos Touloupis, dC50b3Vsb3VwaXNAYWVnZWFuLmdy.

Ethics statement

The study involving humans was approved by the Greek Institute of Educational Policy. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individuals for the publication of any potentially identifiable data included in this article.

Author contributions

TT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^In Greece primary education lasts 6 years including six grades (Ministry of Education, n.d.).

References

Aguirre, A., Moliner, L., and Francisco, A. (2021). “Can anybody help me?” high school teachers’ experiences on LGBTphobia perception, teaching intervention and training on affective and sexual diversity. J. Homosex. 68, 2430–2450. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2020.1804265

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50, 179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Berne, L. A., Patton, W., Milton, J., Hunt, L. Y., Wright, S., Peppard, J., et al. (2000). A qualitative assessment of Australian parents' perceptions of sexuality education and communication. J. Sex Educ. Ther. 25, 161–168. doi: 10.1080/01614576.2000.11074344

Brooke, S. L. (1993). The morality of homosexuality. J. Homosex. 25, 77–100. doi: 10.1300/J082v25n04_06

Brooks, R. B. (2023). “The power of parenting” in Handbook of resilience in children. eds. S. Goldstein and R. B. Brooks (Springer International Publishing), 377–395. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-14728-9_21

Camodeca, M., Baiocco, R., and Posa, O. (2019). Homophobic bullying and victimization among adolescents: the role of prejudice, moral disengagement, and sexual orientation. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 16, 503–521. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2018.1466699

Caprara, G. V., Pastorelli, C., and Bandura, A. (1995). La misura del disimpegno morale in età evolutiva. Eta Εvolutiva 51, 18–29.

D’Urso, G., Maynard, A., Petruccelli, I., Di Domenico, A., and Fasolo, M. (2023). Developing inclusivity from within: advancing our understanding of how teachers’ personality characters impact ethnic prejudice and homophobic attitudes. Sexual. Res. Soci. Policy 20, 1124–1132. doi: 10.1007/s13178-022-00788-7

Department of Primary Education, University of the Aegean (2023–2024). Study guide of undergraduate studies [in Greek]. Available at: https://www.pre.aegean.gr/%ce%bf%ce%b4%ce%b7%ce%b3%cf%8c%cf%82-%cf%83%cf%80%ce%bf%cf%85%ce%b4%cf%8e%ce%bd/# (Accessed May 11, 2024).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., and Buchner, A. (2007). G*power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 175–191. doi: 10.3758/BF03193146

Ferfolja, T., Manlik, K., and Ullman, J. (2023). Parents’ perspectives on gender and sexuality diversity inclusion in the K-12 curriculum: appropriate or not? Sex Educ. 24, 632–647. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2023.2263846

Forlin, C., and Chambers, D. (2003). Bullying and the inclusive school environment. Austr. J. Teach. Educ. 28, 11–23. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2003v28n2.2

Foy, J. K., and Hodge, S. (2016). Preparing educators for a diverse world: understanding sexual prejudice among pre-service teachers. Prairie J. Educ. Res. 1:4. doi: 10.4148/2373-0994.1005

Francis, D. A. (2012). Teacher positioning on the teaching of sexual diversity in south African schools. Cult. Health Sex. 14, 597–611. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.674558

Frumkin, H., Geller, R. J., Rubin, I. L., and Nodvin, J. (2006). Safe and healthy school environments : Oxford University Press.

Gini, G. (2006). Social cognition and moral cognition in bullying: What's wrong? Aggress. Behav. 32, 528–539. doi: 10.1002/ab.20153

Goff, S. (2014). Music teachers’ attitudes toward transgender students and their needs. Unpublished Doctoral thesis: Oregon State University.

Grille, R. (2014). Parenting for a peaceful world. New South Wales, Australia: New Society Publishers.

Heras-Sevilla, D., and Ortega-Sánchez, D. (2020). Evaluation of sexist and prejudiced attitudes toward homosexuality in Spanish future teachers: analysis of related variables. Front. Psychol. 11:572553. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.572553

Herek, G. M. (2000). Sexual prejudice and gender: do heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men differ? J. Soc. Issues 56, 251–266. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00164

Ιannello, N. M., Camodeca, M., Gelati, C., and Papotti, N. (2021). Prejudice and ethnic bullying among children: the role of moral disengagement and student-teacher relationship. Front. Psychol. 12:713081. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.713081

Iliadou, M. (2020). The coming out of gay men in Greece: Stages, factors influencing it, consequences [in Greek]. Unpublished Master thesis. Hellenic Mediterranean University.

Ioverno, S. (2023). Inclusive national educational policies as protective factors for LGBTI youth adjustment: an european cross-national study. J. Adolesc. Health 72, 845–851. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2023.01.013

Ioverno, S. A. L. V. A. T. O. R. E., Nardelli, N., Baiocco, R., Orfano, I. S. A. B. E. L. L. A., Lingiardi, V., Baiocco, R., et al. (2016). Homophobia, schooling, and the Italian context. Sexual Orient. Gender Identity School, 354–373. doi: 10.1093/med:psych/9780199387656.003.0020

Jones, S. L., and Kwee, A. W. (2005). Scientific research, homosexuality, and the Church's moral debate: an update. J. Psychol. Christian. 24, 304–316.

Kadyro, K. B., and Mullabaeva, N. M. (2023). Safe school environment as a factor of children's personal development. J. Psychol. Soci. 87, 25–30. doi: 10.26577/JPsS.2023.v87.i4.03

Karadimos, D. (2022). Homophobia in Greek educational system [in Greek]. Unpublished Master thesis. Democritus University of Thrace.

Katz-Wise, S. L., Gordon, A. R., Sharp, K. J., Johnson, N. P., and Hart, L. M. (2022). Developing parenting guidelines to support transgender and gender diverse children’s well-being. Pediatrics 150:e2021055347. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-055347

Klocke, U. (2024). Sexualization of children or human rights? Attitudes toward addressing sexual-orientation diversity in school. J. Homosex. 71, 600–631. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2022.2122368

Kwok, D. K. (2019). Training educators to support sexual minority students: views of Chinese teachers. Sex Educ. 19, 346–360. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2018.1530649

Mark, K., Corona-Vargas, E., and Cruz, M. (2021). Integrating sexual pleasure for quality & inclusive comprehensive sexuality education. Int. J. Sex. Health 33, 555–564. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2021.1921894

McCormack, O., and Gleeson, J. (2010). Attitudes of parents of young men towards the inclusion of sexual orientation and homophobia on the Irish post-primary curriculum. Gend. Educ. 22, 385–400. doi: 10.1080/09540250903474608

Ministry of Education (n.d.). Primary school [in Greek]. Available at: https://www.minedu.gov.gr/dimotiko-2/to-thema-dimotiko (Accessed May 11, 2024).

Ng, H. N., Boey, K. W., Kwan, C. W., and To, H. K. A. (2024). Secondary school students’ views on sexuality and sexual health education. Int. J. Sex. Health 36, 391–405. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2024.2341627

Pedagogical Institute (n.d.). School books in digital format [in Greek]. Available at: http://www.pi-schools.gr/books/dimotiko/

Ramiro, L., and Matos, M. G. D. (2008). Perceptions of Portuguese teachers about sex education. Revista de Saude Publica 42, 684–692. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102008005000036

Runhare, T., Mudau, T. J., and Mutshaeni, H. N. (2016). South African teachers’ perceptions on integration of sex education into the school curriculum. Gender Behav. 14, 7638–7656.

Sayfulloevna, S. S. (2023). Safe learning environment and personal development of students. Int. J. Formal Educ. 2, 7–12.

Shin, H., Lee, J. M., and Min, J. Y. (2019). Sexual knowledge, sexual attitudes, and perceptions and actualities of sex education among elementary school parents. Child Health Nurs. Res. 25, 312–323. doi: 10.4094/chnr.2019.25.3.312

Souza, E. D. J., Espinosa, L. M. C., Da Silva, J. P., and Santos, C. (2016). Inclusion of sexual diversity in schools: Teachers' conception. Multidiscip. J. Educ. Res. 6, 152–175. doi: 10.17583/remie.2016.2004

Sprague, J. R., and Walker, H. M. (2021). Safe and healthy schools: Practical prevention strategies : Guilford Publications.

Ullman, J., Ferfolja, T., and Hobby, L. (2022). Parents’ perspectives on the inclusion of gender and sexuality diversity in K-12 schooling: results from an Australian national study. Sex Educ. 22, 424–446. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2021.1949975

Van de Mortel, T. F. (2008). Faking it: social desirability response bias in self-report research. Austr. J. Adv. Nur. 25, 40–48.

Van Leent, L. (2017). Supporting school teachers: primary teachers’ conceptions of their responses to diverse sexualities. Sex Educ. 17, 440–453. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2017.1303369

Van Leent, L., and Moran, C. (2023). “Healthy and Normal”: parents’ perspectives on gender and sexual diversity in elementary relationships and sexuality education. Int. J. Diver. Educ. 23, 51–65. doi: 10.18848/2327-0020/CGP/v23i02/51-65

Woolweaver, A. B., Drescher, A., Medina, C., and Espelage, D. L. (2023). Leveraging comprehensive sexuality education as a tool for knowledge, equity, and inclusion. J. Sch. Health 93, 340–348. doi: 10.1111/josh.13276

Keywords: primary school teachers, parents, perspective, sexually inclusive education, homophobic prejudice, moral disengagement

Citation: Touloupis T and Pnevmatikos D (2024) A preliminary examination of teachers’ and parents’ perspective on sexually inclusive primary education: The role of homophobic prejudice and moral disengagement. Front. Educ. 9:1421759. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1421759

Edited by:

Jessie Ford, Columbia University, United StatesReviewed by:

Kai Nagase, Yamaguchi Prefectural University, JapanAsimenia Papoulidi, University of West Attica, Greece

Copyright © 2024 Touloupis and Pnevmatikos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Thanos Touloupis, dC50b3Vsb3VwaXNAYWVnZWFuLmdy

†Present address: Thanos Touloupis, Department of Education, University of Nicosia, Nicosia, Cyprus

Thanos Touloupis

Thanos Touloupis Dimitrios Pnevmatikos

Dimitrios Pnevmatikos