- Department of Educational Foundations and Continuing Education, The University of Dodoma, Dodoma, Tanzania

Introduction: Tanzania, like other developing countries, has adopted numerous educational reforms geared towards addressing challenges rooted in either the colonial or post-colonial educational systems. However, the influence of these reforms on teacher professionalism is seldom studied. This study, therefore, gained insights into how the secondary education expansion policy related challenges affected teachers as teaching professionals.

Methods: The qualitative case study design was adopted in order to capture the holistic overview of the phenomena under exploration. Individual interviews, focus group discussion, and document analysis were utilized for gathering data. The main participants were teachers and school principals who were purposively selected from the Iringa region, Tanzania. The region promptly managed to build at least one secondary school in each ward (i.e., at least two villages) as per the government’s expansion enactment directives.

Results: It was revealed that the inadequate enactment of the expansion policy adversely affected teachers’ self-beliefs about their own teaching aptitudes, their apathy towards teaching, as well as their social status. These issues undermined successful implementation of the policy itself.

Discussion: The study adds to a growing body of literature around how teachers “construct” what secondary expansion means for them as both effective and ethical professionals.

1 Introduction

The successful accomplishment of educational goals depends entirely on how teachers construct their sense of identity within and beyond their workplaces (Li, 2023). Thinking about and being aware of the concept of teacher identity provides a better understanding of teaching both as a profession and a practice (Demirdag, 2015). Teacher identity and its formation have gained great attention in recent years (Bacova and Turner, 2023; McConville, 2023). Identity is necessarily multifaceted, fluid, and subjective because different people view it in different ways depending on their context (Do and Hoang, 2023; Fadjukoff et al., 2016; Mora et al., 2016). Despite this, however, teacher identity broadly embraces how teachers see themselves as professionals in the community (i.e., self-image), their beliefs on how others perceive them, and how they are viewed by society at large (Ma, 2022; Xing, 2022). Literature (Nagdi et al., 2018; Zeng et al., 2022) highlights that teacher identity is not something that occurs naturally, but it emerges and develops as an individual teacher interacts with his/her professional environment. In other words, the working conditions in which teachers perform their roles shape and reshape their identities.

Teachers develop negative perceptions about their teaching profession as a result of the challenging working environment they encounter and vice versa. These perceptions determine their sense of resilience, commitment, efficacy, and engagement in their profession (Li, 2023; Wells, 2015). Wells (2015) in his research on the factors that might influence preschool teacher turnover and retention, found that approximately 40% of novice teachers were likely to leave their career of choice because of limited professional support and inadequate positive workplace mutual relations. In a study by Zinsser et al. (2016), teachers who viewed the workplace conditions of their school in negative terms became depressed and subsequently lost their enthusiasm to support their children to grow both socially, emotionally, and intellectually. However, studies on the link between workplace climate and teacher identity development in the Tanzanian setting were scarcely available.

There is ample scholarship suggesting that teacher education programs impact teacher identity development (Ma, 2022; Spicksley et al., 2021; Yin et al., 2016). Teachers and school leaders who share their experiences and knowledge with colleagues, and pre-service teachers who are adequately prepared feel more competent to teach than those who do not (Hong, 2010; Lamash and Fogel, 2021; Zhao, 2022). Exploring factors that contribute to professional identity formation among school leaders in Turkey, Luehmann (2008) found that schools’ perceptions about themselves as leaders changed when they frequently interacted with out-of-school coworkers and reflected on their practice. Therefore, understanding networking opportunities and their implications for teacher identity construction in Tanzania was an inevitable attempt. Cheng (2021) argues that teacher education program that enhances professional identity should reflect on teachers’ pedagogical beliefs, their emotional experiences, as well as their teaching environment and culture. The lack of these critical points compromises teacher identity development.

Finland is one example of countries that has promoted teacher identity to accomplish the world’s best education system (Khoza, 2023). Although the country has developed rules of professional identity that guide the implementation of teaching and learning policies, teachers are less enthusiastic in following them. Factors that compromise teachers to abide by the rules and how this influences them to construct their identities are not adequately identified. Cheng (2021) in his research found that teachers’ emotions are important factors that shape their identities and subsequently affect their work performance. When teachers reflect on themselves in regard to the nature of their work and such factors as their satisfaction and teaching motivation, they develop negative or positive emotions (McConville, 2023; Scherr and Johnson, 2017; Zhao, 2022).

Educational change or reform can be an identity-disrupting (Gao and Cui, 2022; Harrison and Alberti, 2022). The reform related challenges prompt teachers to interpret and re-interpret their own values and their past work or teaching experiences. Emotional tensions give rise as these teachers struggle cope with new changes and in turn fail to adequately implement the reforms. Bolívar et al. (2014), for example, argue that teachers become resistant to changes as a strategy to safeguard their identities if they are not adequately involved in the school curricula reform process because they view themselves as seriously isolated. Between 2004 and 2015, the government of Tanzania enacted and implemented the secondary education expansion policy (Ministry of Education and Vocational Training, 2008, 2010). As a result of this, new schools were built. Evidence, however, indicates that despite the government initiatives to expand the secondary education sector, poor student performance remained problematic in the country (Ministry of Education and Vocational Training, 2010; Twaweza, 2013).

A growing body of research has suggested that teacher identity plays a powerful influence on student achievement and cognitive development (Izadinia, 2013; Keile, 2018; Pishghadam et al., 2022). On the basis of the poor student performance, one of the assumptions behind this research was that the secondary education enactment plan has had a negative implication for teacher identity. Contextual factors that compromise teachers’ ability to perform their roles are numerous (Marschall, 2022; Sumra, 2015; UNESCO, 2021). However, little research has addressed how the secondary education expansion associated challenges has impacted on teacher identity development. I was particularly interested in the identities of teachers because these identities determine how teachers teach, how they grow as professionals, and how they feel about changes introduced in the education system (Clarke et al., 2022; Gao and Cui, 2022; Liu and Trent, 2023). The main research question was: “To what extent has the increase of secondary schools impacted teachers as teaching professionals?” The answers will contribute important knowledge not only about the professional life of secondary school teachers but also, more importantly, what factors are contributing towards a decrease (or not) of professional identities amongst secondary school teachers. Arguably, if these factors are made aware, and begin to redress, it is possible not only to produce a far more confident body of teachers but also provide a means for improving student academic performance.

2 The secondary education enactment and social positioning of teachers

Secondary education in Tanzania is regarded as a pathway to vocational training, tertiary level, and the world of work. For this reason, the government has been enacting and implementing diverse education development plans. The growth of primary education in the country, for example, has created a large demand for secondary education. Owing to this, the government of Tanzania developed the secondary education development policy. The policy was implemented in two phases (i.e., 2004–2009 and 2010–2015). The government believed that without this expansion policy, the transition from primary to secondary schooling would dramatically drop. The policy ensured that each ward (two, three, or four villages) had at least one secondary school within their locality in order to absorb primary school graduates. Alongside improving the quality of education delivery, the policy was intended to achieve equity and increase access to secondary education (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2004; Ochieng and Yeonsung, 2021). The introduction of fee-free education in recent years was geared towards maximizing the enrolment rates in the schools established under the new policy.

The implementation of the secondary education development plan in the country is compromised by several challenges. The main challenge is poor life-long learning skills and livelihood among secondary education graduates (Kinyota et al., 2019; United Republic of Tanzania, 2018). Although teachers are an integral part of the education system, their right to favourable working environment is often overlooked (UNESCO, 2021). There is a disparity in working conditions between urban and rural localities. Poor classrooms, shortage of houses, and medical issues are more problematic among rural teachers than urban counterparts (Nyamubi, 2017; Stromquist, 2018). For this reason, a number of rural teachers migrate to urban schools. The implication here is that the expansion plan has expended limited attention on retaining all (or rural teachers). Despite the government and community initiatives to build many new schools and enroll a high number of students, salaries and other fringe benefits are still challenging (Ndijuye and Tandika, 2019; Sahito and Vaisanen, 2019). These factors compromise the social standing of teaching profession and subsequently discourage young people to become teachers. Shortage of teaching resources and teacher professional development opportunities continue to exist across secondary schools in the country.

Notwithstanding the secondary education sector being supported by the government and community in terms of resources, the sector remains extremely under-funded (African Development Bank, 2007). Most of the budget in the education sector depends heavily on funds from development donors which are sometimes unreliable (Ochieng and Yeonsung, 2021). Foreign aid in relation to financial resources has tremendously declined in favour of other traditional projects (African Development Bank, 2007). Donor practices influenced the budget of the secondary education sector through various means, including encouraging international financial institutions to provide strict and tight fiscal discipline. This strategy constrained the education fiscal space in terms of teachers’ wage bill. Therefore, the diverse working conditions in which the teachers in the country implemented the education development plan would, I surmised, have far-reaching effects on how they view themselves as educational professionals.

3 Methods

A qualitative study approach was deemed appropriate for understanding the phenomena at hand. This approach provides an opportunity to comprehend and build a holistic overview of what the participants said before data analysis and interpretation take place (Cresswell, 2009; Soklaridis, 2009). In addition, a qualitative study permits greater interaction between the researcher and participants, thus offering participants the opportunity to shape the information that emerges in the course of data gathering (Cohen et al., 2011; Wiersman, 1986). It is through this approach that the participants’ social world and their lived experiences are gathered. Mutch (2013) points out that one of the strengths of qualitative-related studies are that they do not allow predetermined hypotheses. To gain detailed narratives, I grasped and shared subjective views with those who implemented the expansion policy in their natural settings. In other words, meanings or sense-making of data is drawn from the participants’ perspectives (Bryman, 2012; MacMillan and Schumacher, 2010).

Diverse methods were used to gather rich descriptive accounts of the participants’ experiences and perceptions in terms of their feelings and beliefs about the study phenomena (Corbetta, 2003). However, a particular focus of this qualitative study is placed more on understanding rather than the description or explanation of what is happening in relation to the policy implementation.

3.1 Participants and contexts

This study consisted of teachers and school principals who were purposively drawn from two (i.e., one high and one low performing) newly established secondary schools in the Iringa region, Tanzania. A total of 14 participants (i.e., two school principals and 12 teachers) engaged in my study. While teachers help students to develop academically, school principals perform all school managerial functions, including setting school strategies and establishing teachers’ performance expectations (UNESCO, 2009). Therefore, these individuals were considered as a primary rich-information source because they implemented the policy and had experienced its effects. The secondary development policy placed more attention on the construction of new schools rather than expanding the existing or old schools. For this reason, the old schools were excluded in my study.

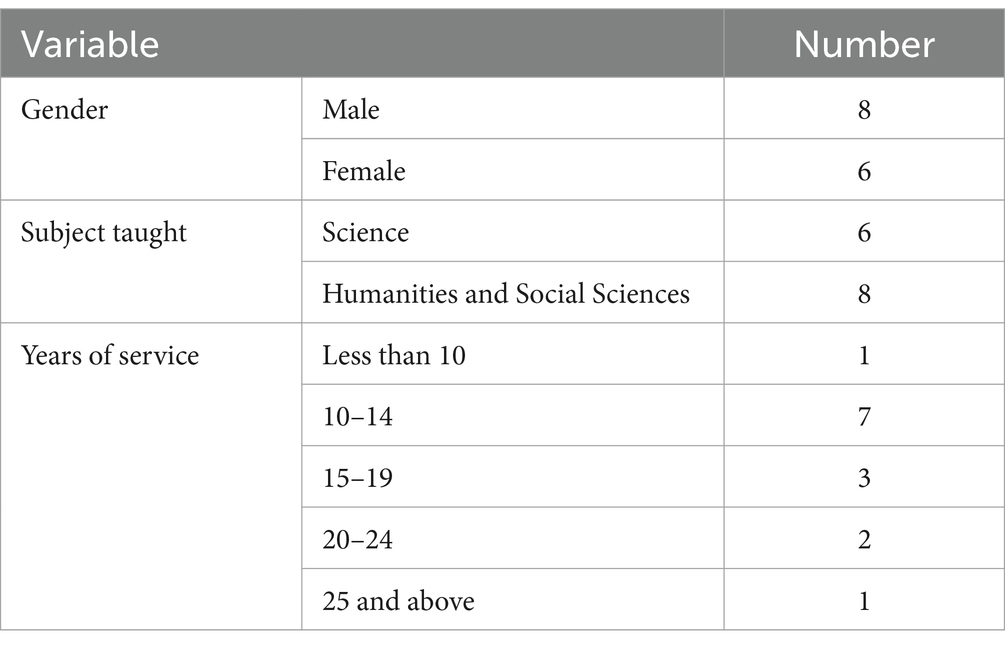

Studies have shown that various demographic characteristics determine how teachers construct their sense of themselves as teachers (Fadjukoff et al., 2016; Sarouphim and Issa, 2020). Similarly, teachers who took part in my study were purposively selected. Purposive sampling technique was adopted to obtain rich-information participants (Mutch, 2013; Bryman, 2012). Gender, subject areas of specialization, and years of service were used as the selection criteria (see Table 1). The assumption here was that the male and female teachers may have different experiences and perspectives about the study phenomenon. However, although school principals were selected based on their positions, they were all males and had more than 5 years of service. More specifically, school principals from the Republic School (Principal #1) and Rift Valley School (Principal #2) had 11 and 7 years of experience as school leaders and supervisors. The two school principals specialised in humanities and social science subject during their pre-service teacher education. The deliberate attempt had been undertaken to ensure that at least an equal number of participants across gender and subject areas of specialization were sampled for them to share their experiences with regard to the issue under investigation. The more experienced teachers were highly prioritized in my study than their novice colleagues. Tschannen-Moran et al. (1998) argue that novice teachers may be less aware of the problem under exploration than the more experienced colleagues. A range of teaching experiences helped me to obtain adequate first-hand information about the diverse challenges that the expansion plan generated in the course of its implementation. In my study, all names of schools are pseudonyms. Schools were synonymized as Republic (high performing), and Rift Valley (low performing).

3.2 Data collection

Typically, qualitative related studies focus on gathering a massive amount of data to further their better understanding of the phenomena under investigation (Best and Khan, 2006; Bordens and Abbott, 2008). A variety of instruments and methods are required to achieve this particular intention. Data related to beliefs and feelings around how the challenges emerged in the context of the secondary education policy enactment and implementation shaped teachers were gathered through one-to-one or individual interviews (IT).

I interviewed two school principals (i.e., one in each school) individually in order to get detailed information about themselves, their teachers, and their schools, particularly with regard to the policy implications. Literature (Cohen et al., 2011; Croker, 2009; Flick, 1998) points out that some participants are less comfortable with one-to-one interviews but feel happy and confident to share perspectives with others whom they are already familiar with. Focus group interviews with teachers were undertaken to enable participants’ similarities and differences in experiences (Soklaridis, 2009). According to Ary et al. (2010), group interviews are more socially oriented as compared to individual interviews. When a participant listens to others, he or she can able to form his or her own beliefs. Thus, focus group interviews are helpful because they bring several different viewpoints into contact (Ivankova and Creswell, 2009).

Consensus about the exactly number of participants required to make a coherent group that can provide rich data or information is not yet reached between and among researchers (Basit, 2010; Bryman, 2012; Cohen et al., 2011). In my study, however, a single group consisted of six teachers. Of the six, three were science teachers and the other three were humanities and social science teachers. Again, out of six, three were male teachers and the other three were female teachers. Thus, there were two focus group conversations (i.e., one from each school). Consent forms were distributed to the teachers for them to decide whether they would participate in my study or not. As with individual interviews, only teachers who returned a signed consent form had the opportunity to engage in focus groups. However, school principals were not part and parcel of participants in the focus groups. The category of humanities and social science teachers involved those who taught either Geography, English, Kiswahili, History or Civics subjects. Those categorised as science teachers were those who influenced teaching and learning in subjects such as Biology, Physics, Chemistry, and Mathematics.

All interview items or questions were typically open-ended and were designed to reveal what was important to understand about the study phenomena (Wellington, 2008). Probing strategies were, however, employed depending on the responses from the participants. I provided the participants with opportunities to freely express and or respond to the questions in their own words either at length or briefly. Leading questions were avoided and reconstruction of ideas. Some of the interview questions that participants were asked include: What are the current challenges facing you as teachers? How these affect your teaching profession? How would you describe the teaching and learning environment in your school? How do these affect you? These questions sought to gain insights into the participants’ feelings in relation to the implementation of the expansion policy. However, before embarking on actual study, interview questions were piloted to identify awkward items and determine interviewing duration (Basit, 2010).

I was aware that some interviewees might be unwilling to share information or might even provide false information (Silverman, 2000). To address this, a short introductory meeting was conducted so as to develop trust, reduce social distance, and build mutual understanding (Cohen et al., 2011; MacMillan and Schumacher, 2010). The duration of individual and focus group interviews ranged from 1 h to 2 h, respectively. All interviews were digitally recorded subject to the participants’ consent. This not only helped me to remain focused, but it also provided a verbatim record of the responses. The interview transcripts were then shared with the participants in order to determine the accuracy of gathered data. This process provided an opportunity for the participants to add and clarify any ambiguities (Wellington, 2008).

Evidence suggests that secondary sources or documents enhance the quality of interview gathered data as they provide good descriptive information (Bryman, 2012; Hancock and Algozzine, 2006; De Vos et al., 2005). My study analysed the government document, especially the secondary education development plan. This practice helped me to gain insights into how the expansion policy promises and its implementation strategies influenced teachers to develop their own identities. The evaluation about the authenticity of the document before the analysis process is undertaken is important for ensuring that the gathered information is valid (Basit, 2010). I was aware that the education sector in Tanzania has a number of policies targeting different individuals. For this reason, only the secondary education development policy was analysed. A particular focus was placed on understanding the policy promises and practices in terms of promoting teachers’ professional lives for them to teach effectively and efficiently. These factors influenced the ways in which interview questions were developed.

3.3 Data analysis

The gathered data were organized so that they became easily retrievable. My data were thematically analyzed by using six steps developed by Braun and Clarke (2006). Prior to actual analysis, the interview data were transcribed. To achieve this, I repeatedly listened to audiotapes. More specifically, I listened what the participant say including their inner voice while taking into account their nonverbal cues (Seidman, 2006). Words were transcribed directly to avoid any potential bias that might occur with summarizing. I did not attempt to change phrases or words to make them grammatically correct as it could compromise the meaning of what participants said (Ary et al., 2010). In this process, I also stripped identifiable information so as to ensure confidentiality. Once transcription has been made, I continued to read and re-read the data for reflection and familiarization purposes. As I familiarized myself with the data, I wrote notes or memos (reflective log) to capture my thoughts as they occurred. The memos were written in the margins of the transcripts implying key ideas (De Vos et al., 2005). I then reviewed all the notes in the margin and made a complete list of the different type of emerged information.

After data familiarization, I generated initial codes. Phrases, words, sentences, and behaviour patterns that seemed to occur regularly were identified or sorted out. New understanding emerged as I continued to code the data, thus necessitating changes in the original transcripts. The developed codes were labeled (i.e., related phenomena were assigned same names) in order to recognize similarities and differences in the data. A deliberate attempt was undertaken to make a list of all code words. Similar codes were grouped and I then looked for redundant codes. This initial coding resulted in the development of tentative categories or initial themes. Highlighters were used to indicate which colours of codes were linked with which categories.

The emerged themes were then reviewed to see if they related to dataset and code extracts. To do this, I went back to the original transcripts or dataset to identify further areas not coded so that they are fixed into the developed categories or themes (Ary et al., 2010; Basit, 2010). Too much overlapping between and among themes was avoided. Thereafter, the themes were given specific label or names to differentiate one another. Analytical narratives and data extracts or quotations to inform the findings were then weaved together before plausible explanation and sense making were undertaken (De Vos et al., 2005).

4 Findings

As previously noted, once transcription was undertaken, I searched for relationships and patterns between and among codes until a holistic picture emerged. I then critically examined the data (i.e., reading interview transcripts line by line) and categorized them. As I continued to familiarize with the data, I generated and developed themes. Three major themes emerged as a result of this analysis: perceived loss of teaching aptitude, apathy towards teaching, and undermined status of teaching. Attending in-service training, inability to teach outside their expertise, inadequate time to prepare their teaching lessons, feeling intellectually successful, and using learners as resources to develop professionally were attributes of the first theme. The second theme (apathy towards teaching) was made up of phrases such as engaging in alcoholism, lacking of self-motivation, and developing habits of absenteeism. The identified terms for the third theme, “Undermined social status of teaching” include perceived loss of respect, the sense of isolated, as well as feeling professionally unhappy and overlooked. These issues will be illustrated below.

4.1 Perceived loss of teaching aptitude

There was a varied perspectives and experiences between and among participants about the extent to which the secondary education expansion plan associated challenges affected them as teaching professionals. In their interviews, teachers were anxious that they were inadequately prepared to implement various changes initiated in the school curriculum. While some teachers declared that they had opportunities to participate in one or two in-service training programmes, others were concerned that they lacked such opportunities. Three teachers who had the opportunity to these programmes shared their insights that the programmes helped them “feel successful” in their teaching practices. One participant commented: “I was able to attend in-service training seminars only once. In this seminar we learned how to develop teaching resources. In that seminar, we used an empty plastic water bottle as a funnel or beaker. Now, if you go to our school laboratory you will see that the apparatuses, we have there are of the plastic materials which I improvised myself” (Biology Teacher, Republic School, FG #1). However, teachers who lacked in-service training opportunities “felt incompetent” in their teaching subjects.

Two out of 12 teachers were bothered that the government increased the number of secondary schools without having a corresponding target to increase teacher numbers. The experience from two teachers at Rift Valley School mentioned that initially their school had only three teaching staff personnel with 600 students. The few teachers available in these schools taught only subjects of their specialization while leaving quite a number of others untaught. These teachers associated poor student performance trends with teacher shortage. One of the teachers stated, “Since the school had only three teachers, those teachers were being overworked and they were usually very tired. This is because the same teacher would be required to teach, deal with students’ discipline, and work as a head of department” (Physics Teacher, Rift Valley School, FG #2). Nine out of 12 teachers were anxious that because of high workload, they lacked adequate time to prepare their lessons. One participant concluded, “Teachers of this category lost their confidence in teaching and subsequently labelled by their students as intellectually ineffective” (Principal #2, IT4).

While some teachers believed that the shortage of teachers adversely impacted on their mastery of teaching, others place their concern on teaching and learning materials. One of the teachers maintained that their roles are to guide the learners by giving them direction of what to learn. With this logic, then the teachers expressed that the lack of a library and books in the new established schools prevented them from using learners as sources of knowledge. For this reason, teachers continued to assume a traditional role of the pedagogy by being sources of knowledge because students had nowhere to go to look for new ideas to be shared during classroom teaching and learning. The resource shortcomings prompted teachers to use more effort in trying to explain theoretically to the students how such materials look like and how they are used. Six out of 12 teachers were worried that once these students fail to demonstrate how to use those materials, particularly after completion of their studies, it is the teacher who taught them who will be blamed and categorized as incompetent in his or her job.

4.2 Apathy towards teaching

The government promised in the expansion policy that it would construct adequate houses for teachers in all new schools. Findings, however, revealed that in the construction of new schools very little attention was placed on the teachers’ settlements. The scarcity of houses prompted teachers to rent houses or rooms off school premises. Teachers claimed that renting houses off school premises was a challenge to them because sometimes students from far away villages rented rooms in the same house in which these teachers lived. The school principals made it clear that since teachers lived very far away from their schools, it was impossible for them to carry a load of students’ exercise books home to mark. One of the participants raised this concern: “Given this impossibility, even if the teacher is enthusiastic to perform their roles beyond the school context, he or she may resort to engage in alcoholism, therefore adding further to a mockery of the teaching profession” (Principal #2, IT4).

The school principals were asked to provide their own perceptions about the government’s initiative to recruit many school graduates to enter the teaching profession. Although some principals acknowledged that this initiative helped to reduce teacher shortage, they were concerned that these teachers were not self-motivated to teach until they were pushed to do so. One participant complained: “According to teaching profession regulations, unless the teacher is on leave, he/she has to regularly attend to school. But since teachers disregard this, that is why today, as we are here talking, you see me alone” (Principal #1, IT1).

It was also observed that teachers felt overlooked, especially in terms of promotion. The participants pointed out that the delay in implementing promotion and salary advancement during the policy enactment induced the habits of absenteeism to some teachers. Teachers used promotion related issues and lack of salary increase as pretexts for leaving school early to engage in other activities aimed at generating income to make ends meet. While some teachers in urban schools were reported as working in small businesses, their fellow teachers in rural schools engaged in agriculture. Definitely, teachers’ engagement in these tasks would have raised questions within their own communities: were they teachers, agriculturalists, or business people? This would result in social ridicule of the teaching profession.

4.3 Undermined social status of teaching

The school principals and teachers were of the perspective that their value as teaching profession was lost because of the government’s limited attention on creating friendly environment for them to perform their roles effectively and efficiently. It was evident from the teachers that in the construction of new schools much of the focus of the government, and of the community in particular, was placed more on meeting the needs of students than of teachers. Four out of 12 teachers commented that the first priority in schools’ physical construction was how many classrooms were to be built and not where teachers would work.

Two teachers were, however, anxious about the condition of these spaces because they lacked lined ceilings. Most notably this resulted in noise interference from nearby classrooms, especially when classes were in progress. This concern was reported as one of the disrupting teaching preparation factors, because teachers lost concentration. One participant concurred with this view, commenting: “As you see, the school principal’s office is not yet completed in its construction. There is no ceiling between classrooms and my office, it is not possible to have decent conversation above the noise. Sometimes I feel bad and do not see where is my respect as the school principal is” (Principal #2, IT4).

In the course of the expansion policy implementation, the government employed a number of teachers to teach the newly built schools. In order to ensure that teachers perform their roles appropriately, the government promised that it would meet their professional needs such as in-service training and promotion. This government’s promise, particularly in relation to promotion and salary advancement was not adequately implemented. Promotion issues and salary increase did not only lead teachers to engage in unethical matters, but they also resulted in them feel isolated. One of the social and humanities teachers was anxious that these ethical scandals of teachers have been “painting a bad picture of the teaching profession as a whole in the wider community” (History Teacher, Rift Valley School, FG #2).

The expansion plan stipulates that on average the promotion for teachers should be undertaken in every 3 years. It was, however, reported that while promotion for some teachers was being put into effect within 3 years, some teachers had not been promoted for more than 5 years. Teachers frequently made reference to their perspective that civil servants in other sectors were promoted and paid timely. As a result, a number of participants claimed that the time lag or interval between promotion and salary increases prompted teachers to develop a view that they were “overlooked” or “segregated”. It was evident from the participants that promotion and salary improvement concerns contributed to the profession of teaching losing its importance, and reputation both within and beyond the profession. Three out of 16 teachers claimed that whereas people from medicine and engineering are proud to be identified in such professions, other people are not happy to be associated with teaching profession because of inadequate respect it receives.

5 Discussion

The working conditions in which the expansion plan was implemented generated a range of negative sentiments in terms of how teachers evaluate themselves as professionals. These feelings suggest that some teachers were not really professionals in the sense that they do not actually understand what it means to be a teacher. If they were professionals, these teachers would not develop negative attitudes towards teaching and use promotion and salary advancement related issues as pretext for them to engage in unethical scandals. Ayechew Ayenalem et al. (2023) in their study found that the lack of proper supervision and training on ethics contributed to Ethiopian teachers to behave unprofessionally and thereby impact on the perceptions of teaching in the society. The question about whether or not teachers in Tanzania are adequately prepared to behave as moral professionals remains unanswered. Wang et al. (2021) claim that since teachers’ unethical behaviours affect students’ psychological well-being and learning, prevention should start in pre-service teacher education.

Scholarly literature (Arthur et al., 2017; Suar, 2014) argues that teachers who lack knowledge and skills about certain professional conduct are likely to engage in unethical matters as compared to colleagues who possess such competences. These teachers may further cause the teaching profession lose its status to the wider society. Findings revealed that teachers interviewed anticipated that the government and community would respect them as teachers. There was also a suggestion that at least some teachers desired or wanted respect, sense of privilege, and entitlement without having to earn it. On the basis of this, one can conclude that a number of teachers who took part in this study were often extrinsically motivated. Evidence indicates that teachers who extrinsically motivated always feel disenchanted with their occupation and consequently may decide to leave the profession (Paredes-Aguirre et al., 2022; Tomšik, 2016; Zheng et al., 2021). Apropos to this, the inadequate nature of the secondary education expansion policy resulted in teachers feeling less capable in performing their teaching tasks. In other words, these teachers felt constrained in relation to their aptitude to exercise judgment.

Teachers expected the expansion policy to meet all their professional needs for them to teach effectively and efficiently. The government was, however, overwhelmed with a number of responsibilities to address within and beyond the policy. These teachers compared the situation before and after the enactment and implementation of the expansion plan. Prior to the policy enactment, for example, the government was somewhat able provide teachers with house facilities within their schools and promote them and pay salary advancement timely. This seldom happened when the expansion policy was underway. In most cases, the expansion of secondary education sector was supported by foreign grants with a particular focus on enhancing student learning. These teachers did recognize that transition in countries with poor economic development takes place slowly due to limited financial resources. As a result of this, teachers rarely demonstrated the sense of tolerance in their workplaces. Findings, therefore, suggest that teachers were not equipped enough to become enthusiastic and creative in supporting the government’s endeavours. Policy-makers in Tanzania paid little attention, particularly in understanding that any educational reform influences teachers’ identities which subsequently influence numerous aspects of their professional lives (Jiang et al., 2021; Liu and Trent, 2023).

The comparison between teaching and other professions such as medicine and engineering that some teachers made raise doubt about their enthusiasm to remain in their occupation. Ishumi (2013) argues that the teaching occupation has not often and everywhere enjoyed similar level of social standing as compared to other professions. These individuals absolutely compare teaching with other professions in terms of salaries or financial gains. A perceived lack of fringe benefits and low salaries are some of the factors which contribute to the teaching to be regarded as the less respected profession. This negative perception makes the profession unattractive to many secondary school graduates. Changing people’s attitude in terms of valuing certain professions by reflecting on financial gain would help to enhance the teaching professionalism.

6 Conclusion

Since teachers are the key implementers of educational reforms, adequate preparation and involvement in policy development are warranted. Teachers who are not involved in adopting, enacting, and implementing reforms would not regard the reforms as theirs. In other words, the lack of involvement reduces the sense of policy ownership. The teachers’ and school principals’ perspectives and experiences suggest that they were not involved from the grassroots, especially during the adoption and enactment of the policy. Deliberate attempt should be made to promote the sense of resilience and perseverance between and among teachers, particularly in dealing with various policy related challenges. These habits need to be developed from their pre-service teacher education. A range of in-service teacher education inside and outside school would also facilitate teachers to act professionally. Findings indicate that school principals rarely supervised their teachers. These principals would not appropriately supervise their colleagues if they themselves were inadequately prepared. Strategies geared towards rewarding teaching excellence are mandatory not only for teachers, but also student success attainment.

7 Limitations and direction for future research

This study was limited to school principals and teachers due to my own understanding that the sense of identity is constructed from one’s perspective and thus they cannot be expressed or elucidated by others. The adopted qualitative inquiry and a few participants in involved in the study did not guarantee for the generalizability of the findings. Teacher identity is a construct which can be measured. Therefore, alongside interviews, other researchers may use surveys or questionnaires to measure the degree of teacher identity during the policy enactment and implementation trajectory and thereafter generalize the findings. Since the implication of the expansion policy is reflected in student learning achievement, it would also be significant to explore students’ perspectives and experiences on how this policy affected them as learners. This would provide the government with an opportunity to devise strategies that would enhance the quality of learning. Although the expansion policy was implemented by a joint effort between the government and the community, the latter were not engaged in my research. Understanding the challenges that compromised the local communities to work collaboratively with schools to effectively support the policy implementation is an inevitable endeavour. Data gathered from these local communities would help the government to develop various courses of actions to enlist or influence more parental and community participation in improving the professional lives of teachers. There is also a need to gain more insights into how teachers’ sense of entitlement, respect, and recognition shape and reshape their ability to make a difference in their classroom teaching practices when the policy was underway.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/browse?rpp=85&sort_by=1&type=title&offset=11390&etal=15&order=ASC.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Waikato Ethical Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

GL: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

African Development Bank (2007). Program in support of secondary education development plan. Dar es Salaam: Human Development Department.

Arthur, J., Davison, J., and Lewis, M. (2017). Professional values and practice: Achieving the standards for QTS. New York, NY: Routledge.

Ary, D., Jacobs, L. C., Sorensen, C., and Razavieh, A. (2010). Introduction to education research. 8th Edn. Wadsworth: Cengage Learning.

Ayechew Ayenalem, K., Gone, M. A., Yohannes, M. E., and Lakew, K. A. (2023). Causes of teachers’ professional misconduct in Ethiopian secondary schools: implications for policy and practice. Cogent Educ. 10, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2023.2188754

Bacova, D., and Turner, A. (2023). Teacher vulnerability in teacher identity in times of unexpected social change. Res. Post-Compuls. Educ. 28, 1–24. doi: 10.1080/13596748.13592023.12221115

Basit, T. N. (2010). Conducting research in educational contexts. New York, NY: Continuum Publishing Group.

Best, J. W., and Khan, J. V. (2006). Research in education. 10th Edn. New York, NY: Pearson Education, Inc.

Bolívar, A., Domingo, J., and Pérez-García, P. (2014). Crisis and reconstruction of teachers’ professional identity: the case of secondary school teachers in Spain. Open Sports Sci. J. 7, 106–112. doi: 10.2174/1875399X01407010106

Bordens, K. S., and Abbott, B. B. (2008). Research design and methods: A process approach. 8th Edn. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Cheng, L. (2021). The implications of EFL/ESL teachers’ emotions in their professional identity development. Front. Psychol. 12, 1–7. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.755592

Clarke, M., Atwal, J., Raftery, D., Liddy, M., Ferris, R., and Sloan, S. (2022). Female teacher identity and educational reform: perspectives from India. Teach. Dev. 27, 415–430. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2023.2219645

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2011). Research methods in education. 7th Edn. London: Routledge.

Cresswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. 3rd Edn. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

Croker, R. A. (2009). “An introduction to qualitative research” in Qualitative research in applied linguistics: A practical introduction. eds. J. Heigham and R. A. Croker (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan).

De Vos, A. S., Strydom, A. H., Fouche, C. B., and Delport, C. S. L. (2005). Research at grassroots for social sciences and human service professions. Pretoria: Van Schaik.

Demirdag, S. (2015). Assessing teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction: middle school teachers. J. Educ. Instruct. Stud. World 5, 35–43.

Do, Q., and Hoang, H. T. (2023). The construction of language teacher identity among graduates from non-English language teaching majors in Vietnam. Engl. Teach. Learn. 48, 1–18. doi: 10.1007/s42321-42023-00142-z

Fadjukoff, P., Pulkkinen, L., and Kokko, K. (2016). Identity formation in adulthood: a longitudinal study from age 27 to 50. Identity 16, 8–23. doi: 10.1080/15283488.2015.1121820

Gao, Y., and Cui, Y. (2022). Agency as power: An ecological exploration of an emerging language teacher leaders’ emotional changes in an educational reform. Front. Psychol. 13, 1–15. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.958260

Hancock, D. R., and Algozzine, B. (2006). Doing case study research: A practical guide for beginning researchers. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Harrison, M., and Alberti, H. (2022). How does the introduction of a new year three GP curriculum affect future commitment to teach? An evaluation using a realist approach. Educ. Prim. Care 33, 92–101. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2021.1974952

Hong, J. Y. (2010). Pre-service and beginning teachers’ professional identity and its relation to dropping out of the profession. Teach. Teach. Educ. 26, 1530–1543. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.06.003

Ishumi, A. G. M. (2013). The teaching profession and teacher education: trends and challenges in the twenty-first century. Afr. Educ. Rev. 10, S89–S116. doi: 10.1080/18146627.2013.855435

Ivankova, N. V., and Creswell, J. W. (2009). “Mixed methods” in Qualitative research in applied linguistics: A practical introduction. eds. J. Heigham and R. A. Crocker (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan).

Izadinia, M. (2013). A review of research on student teachers’ professional identity. Br. Educ. Res. J. 39, 694–713. doi: 10.1080/01411926.2012.679614

Jiang, H., Wang, K., Wang, X., Lei, X., and Huang, Z. (2021). Understanding a STEM teacher’s emotions and professional identities: a three-year longitudinal case study. Int. J. STEM Educ. 8, 1–22. doi: 10.1186/s40594-40021-00309-40599

Keile, L. S. (2018). Teachers’ roles and identities in student-centered classrooms. Int. J. STEM Educ. 5, 1–20. doi: 10.1186/s40594-40018-40131-40596

Khoza, S. B. (2023). Can teachers’ identities come to the rescue in the fourth industrial revolution? Technol. Knowl. Learn. 28, 843–864. doi: 10.1007/s10758-021-09560-z

Kinyota, M., Kavenuke, P. S., and Mwakabenga, R. J. (2019). Promoting teacher professional learning in Tanzanian schools: lessons from Chinese school-based professional learning communities. J. Educ. Humanit. Sci. 8, 47–63.

Lamash, L., and Fogel, Y. (2021). Role perception and professional identity of occupational therapists working in education systems. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 88, 163–172. doi: 10.1177/00084174211005898

Li, X. (2023). A theoretical review on the interplay among EFL teachers’ professional identity, agency, and positioning. Heliyon 9, e15510–e15519. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15510

Liu, X., and Trent, J. (2023). Being a teacher in China: a systematic review of teacher identity in education reform. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 22, 267–293. doi: 10.26803/ijlter.22.4.15

Luehmann, A. L. (2008). Using blogging in support of teacher professional identity development: a case study. J. Learn. Sci. 17, 287–337. doi: 10.1080/10508400802192706

Ma, D. (2022). The role of motivation and commitment in teachers’ professional identity. Front. Psychol. 13, 1–5. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.910747

MacMillan, J. H., and Schumacher, S. (2010). Research in education: evidence-based inquiry. New York, NY: Pearson.

Marschall, G. (2022). The role of teacher identity in teacher self-efficacy development: the case of Katie. J. Math. Teach. Educ. 25, 725–747. doi: 10.1007/s10857-021-09515-2

McConville, K. (2023). Professional identity formation in becoming a GP trainer: barriers and enablers. Educ. Prim. Care 34, 16–25. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2022.2161072

Ministry of Education and Culture (2004). Education sector development programme: Secondary education development plan. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Author.

Ministry of Education and Vocational Training (2008). Education sector development programme (ESDP): Education sector performance report 2007/2008. Dar es Salaam: Author.

Ministry of Education and Vocational Training (2010). Education sector development programme: SEDP II (July 2010–June 2015). Dar es Salaam: Author.

Mora, A., Trejo, P., and Roux, R. (2016). The complexities of being and becoming language teachers: issues of identity and investment. Lang. Intercult. Commun. 16, 182–198. doi: 10.1080/14708477.2015.1136318

Mutch, C. (2013). Doing educational research: A practitioner guide to getting started. 2nd Edn. Wellington: NZCER Press.

Nagdi, M. E., Leammukda, F., and Roehrig, G. (2018). Developing identities of STEM teachers at emerging STEM schools. Int. J. STEM Educ. 5, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s40594-40018-40136-40591

Ndijuye, L. G., and Tandika, P. B. (2019). Timely promotion as a motivation factor for job performance among pre-primary school teachers: observations from Tanzania. J. Early Child. Stud. 3, 440–456. doi: 10.24130/eccd-jecs.1967201932129

Nyamubi, G. J. (2017). Determinants of secondary school teachers’ job satisfaction in Tanzania. Educ. Res. Int. 2017, 1–7. doi: 10.1155/2017/7282614

Ochieng, H. K., and Yeonsung, C. (2021). Political economy of education: assessing institutional and structural constraints to quality and access to education opportunities in Tanzania. SAGE Open 11, 1–15. doi: 10.1177/21582440211047204

Paredes-Aguirre, M. I., Medina, H. R. B., Aguirre, R. E. C., Vargas, E. R. M., and Yambay, M. B. A. (2022). Job motivation, burnout and turnover intention during the COVID-19 pandemic: are there differences between female and male workers? Healthcare 10, 1–18. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10091662

Pishghadam, R., Golzar, J., and Miri, M. A. (2022). A new conceptual framework for teacher identity development. Front. Psychol. 13, 1–10. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.876395

Sahito, Z., and Vaisanen, P. (2019). A literature review on teachers’ job satisfaction in developing countries: recommendations and solutions for the enhancement of the job. Rev. Educ. 8, 3–34. doi: 10.1002/rev3.3159

Sarouphim, K. M., and Issa, N. (2020). Investigating identity statuses among Lebanese youth: relation with gender and academic achievement. Youth Soc. 52, 119–138. doi: 10.1177/0044118X17732355

Scherr, M., and Johnson, T. G. (2017). The construction of preschool teacher identity in the public school context. Early Child Dev. Care 189, 405–415. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2017.1324435

Seidman, I. (2006). Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences. 3th Edn. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Silverman, D. (2000). Qualitative research: Theory, method and practice. London, UK: Sage publications.

Soklaridis, S. (2009). The process of conducting qualitative grounded theory research for doctoral thesis: experiences and reflections. Qual. Rep. 14, 719–734. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2009.1375

Spicksley, K., Kington, A., and Watkins, M. (2021). “We will appreciate each other more after this”: teachers’ construction of collective and personal identities during lockdown. Front. Psychol. 12, 1–23. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.703404

Stromquist, N. P. (2018). The global status of teachers and the teaching profession. Brussels: Education International Research.

Sumra, S. (2015). Living and working condition of teachers in Tanzania: A research report. Dar es Salaam: HakiElimu.

Tomšik, R. (2016). Choosing teaching as a career: importance of the type of motivation in career choices. TEM J. 5, 396–400. doi: 10.18421/TEM53-21

Tschannen-Moran, M., Hoy, A. W., and Hoy, W. K. (1998). Teacher efficacy: Its meaning and measure. Rev. Educ. Res. 68, 202–248. doi: 10.3102/00346543068002202

Twaweza (2013). Form four examination results: Citizens report on learning crisis in Tanzania. Dar es Salaam: Hivos Publishers.

UNESCO (2021). Teachers’ working conditions in state and non-state school. Washington: Global Education Monitoring Report.

United Republic of Tanzania (2018). Education sector development plan (2016/17–2020/21). Dar es Salaam: Ministry of Education, Science and Technology.

Wang, J., Wang, X.-Q., Li, J.-Y., Zhao, C.-R., Liu, M.-F., and Ye, B.-J. (2021). Development and validation of an unethical professional behavior tendencies scale for student teachers. Front. Psychol. 12, 1–3. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.770681

Wellington, J. (2008). Educational research: Contemporary issues and practical approaches. London: Paston Prepress.

Wells, M. B. (2015). Predicting preschool teacher retention and turnover in newly hired head start teachers across the first half of the school year. Early Child. Res. Q. 30, 152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.10.003

Xing, Z. (2022). English as a foreign language teachers’ work engagement, burnout, and their professional identity. Front. Psychol. 13, 1–8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.916079

Yin, H., Huang, S., and Wang, W. (2016). Work environment characteristics and teacher well-being: the mediation of emotion regulation strategies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 13, 1–16. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13090907

Zeng, L., Chen, Q., Fan, S., Yi, Q., An, W., Liu, H., et al. (2022). Factors influencing the professional identity of nursing interns: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 21, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12912-12022-00983-12912

Zhao, Q. (2022). On the role of teachers’ professional identity and well-being in their professional development. Front. Psychol. 13, 1–4. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.913708

Zheng, J., Gou, X., Li, H., and Xie, H. (2021). Differences in mechanisms linking motivation and turnover intention for public and private employees: evidence from China. SAGE Open 11, 1–13. doi: 10.1177/21582440211047567

Keywords: teacher identity, secondary education, expansion policy, teaching profession, professionals

Citation: Lawrent G (2024) Education sector development and teacher identity construction: a reflective experience. Front. Educ. 9:1407416. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1407416

Edited by:

H. Indu, Avinashilingam Institute for Home Science and Higher Education for Women, IndiaReviewed by:

Vicki S. Napper, Weber State University, United StatesEila Burns, JAMK University of Applied Sciences, Finland

Copyright © 2024 Lawrent. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Godlove Lawrent, Z29kbG92ZWxhdXJlbnRAZ21haWwuY29t

Godlove Lawrent

Godlove Lawrent