- 1School of Graduate Studies, Lingnan University, Hong Kong, China

- 2Cross-Border Education Quality Assurance Research Center, South China Normal University, Guangzhou, China

- 3Development Studies Discipline, Social Science School, Khulna University, Khulna, Bangladesh

In the current epoch of economic globalization, the globalization of higher education has spurred an increasing interest in comprehending global competence. A systematic literature review was conducted, analyzing a wide range of studies from 2013 to 2023 using the Web of Science and Scopus databases. The review aimed to present an updated overview of research on global competence, covering various aspects such as its definition, assessment dimensions, research objectives, methodologies, results, and limitations. Most publications define global competence using knowledge, attitudes, and skills as crucial dimensions, drawing from international organizational documents and research findings. However, the review also emphasizes the need for future research to adopt a longitudinal approach and develop global competence verification tools to measure global competence among university students and faculty. By providing a comprehensive analysis of current research, this review highlights the importance of understanding global competence in higher education and its potential impact on students and faculty in an increasingly interconnected world.

1 Introduction

The interconnected, multicultural world has experienced significant changes due to the opportunities and challenges brought about by globalization (Shliakhovchuk, 2019). Similarly, the Fourth Industrial Revolution has brought about significant transformations in different sectors, like artificial intelligence, robotics, and data analytics, altering our everyday lives and work environments (Fuchs, 2018; Fukuyama, 2018). There has been a significant shift in preparing future generations with the necessary expertise and skills to meet the changing industry demands, aligning educational programs with what is required to prepare students for the dynamic environment (Schroeder, 2016). Hence, adopting global competence-based higher education is crucial for succeeding in the current fast-paced global professional environment (Robertson, 2021a; Robertson, 2021b). This approach equips students to grasp global events, work well with people from various cultures, and promote peaceful, inclusive, and sustainable communities. Mastering intercultural communication, cross-border collaboration, and leveraging technology effectively are essential skills in today’s globalized world (Oliver, 2022). This underscores the significance of higher education focusing on global competence, as it directly prepares students for the challenges and opportunities of the international professional environment.

Higher education institutions are vital in preparing students with the essential global skills needed to thrive in the fast-changing global landscape (Saito, 2019). Many universities have acknowledged the growing emphasis on improving students’ global competence (Deardorff and Arasaratnam-Smith, 2017). Universities around the globe have adopted different approaches to enhance students’ global skills, including providing international courses, promoting cross-border mobility, and employing professors with international experiences (Li et al., 2021; Guo-Brennan, 2022). There has been a shift in higher education toward emphasizing values over knowledge and skills, transitioning from ‘aptitude to attitude’. However, some argue that the shift lacks a suitable epistemic framework and instructional system (Zha and Wu, 2021). Global competence has garnered significant attention in research, not only within academic domains but also notably in the aftermath of the OECD’s Global Competence Assessment conducted in 2018. Delving into conceptual understanding and definition, some studies focus on the nature of global competence and its components (Sälzer and Roczen, 2018). The focus of research centers on the advancement and assessment of global competence and the analysis of methods to enhance students’ global competence in higher education settings (Majewska, 2023). Despite the different perspectives and in-depth analyses provided by these studies, there is still a need for a comprehensive understanding of global competence in higher education. The full synthesis of its domains and dimensions remains incomplete. With this gap in mind, the study aims to comprehensively synthesize global competence, evaluate the standards for assessing global competence in university faculty and students, identify the latest developments in global competence assessment in higher education, summarize the progress in global competence research over the last decade, and highlight the limitations of this research. This study offers an overview of the status and development of global competence among students and teachers in higher education. To achieve this goal, the review will investigate the following research questions:

1. What is the definition of global competence within the context of higher education?

2. What are the typical dimensions employed to evaluate the global competence of university teachers and students?

3. What are the major research purposes, methodologies, and outcomes of research on global competence in higher education over the last decade?

4. What are the limitations of the research on global competence within higher education?

The subsequent sections of this paper are organized as follows: Firstly, the methodology employed for this review and the selection criteria utilized to identify pertinent studies are delineated. Subsequently, the findings are presented, and the research questions are addressed based on the selected literature. Furthermore, the potential limitations of the study are highlighted. Finally, the conclusions are presented along with suggestions for future research on the development of global competence in higher education.

2 Materials and methods

This review is based on the guidelines for systematic literature reviews provided by Kitchenham and Charters (2007). The research questions were explicitly stated as the primary objectives at the beginning of the review. The databases used for the search, as well as the search strings and criteria used to assess and select relevant studies, were described. Then, the publications included in this review were introduced. Finally, this study followed Gough et al.’s (2017) three main phases of systematic review: selecting, identifying, and synthesizing.

2.1 Search strategy

The present literature review opted for using two electronic databases: Web of Science (WOS) and SCOPUS. These databases were selected as the primary sources of international, multidisciplinary academic literature (Chadegani et al., 2013).

A search was conducted for the selected terms within the papers’ titles, keywords, and abstracts. The search strings per chosen electronic database were as follows:

WOS: TS = ((“global competence*” OR “global abilit*” OR “global skill*”) AND (“higher education” OR “universit*"OR “college*”)).

Scopus: TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“global competence*” OR “global abilit*” OR “global skill*”) AND (“higher education” OR “universit*"OR “college*”)).

2.2 Study selection

A comprehensive and meticulous study selection process encompassed multiple stages and activities. The search design was specifically tailored to encompass the most recent trends and research findings on global competence, ensuring alignment with the rapid evolution of global technology. Initially, 271 articles were retrieved through the search process, reflecting the thoroughness of the selection process.

2.2.1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

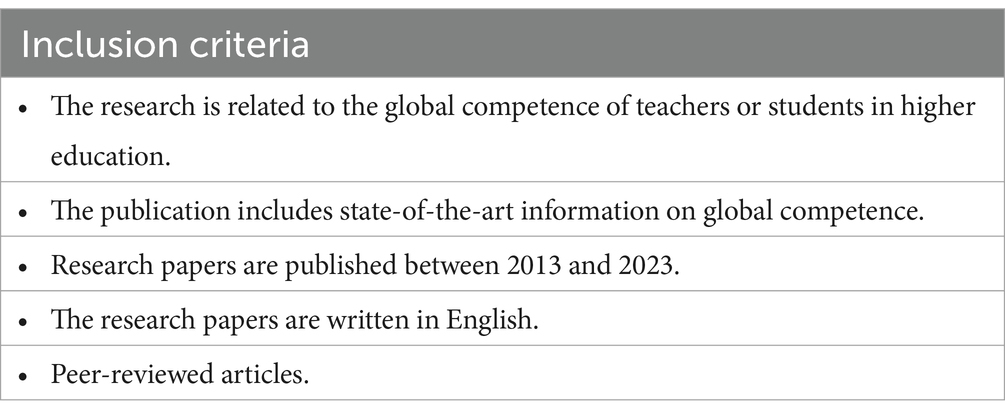

To ensure that the studies selected were appropriate for addressing our research questions, established inclusion (Table 1), and exclusion criteria (Table 2) were utilized. Each study was evaluated based on these criteria. To validate these criteria, a group of experts consisting of three university professionals and one education expert was consulted.

2.2.2 Quality criteria

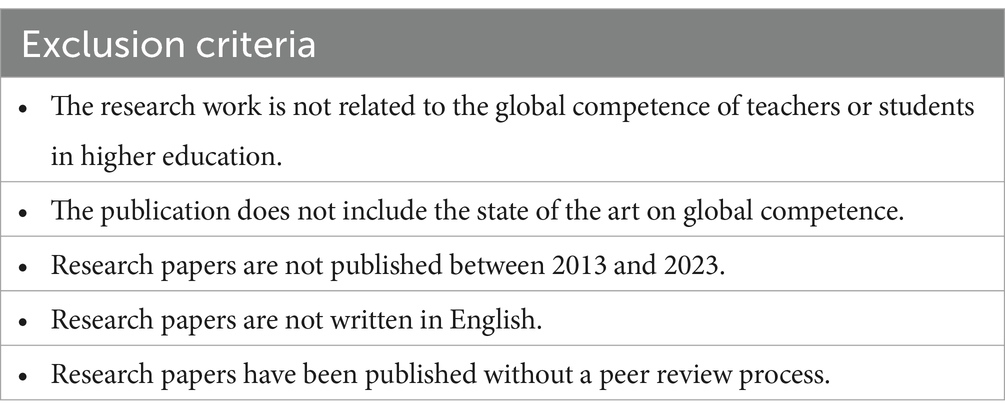

The chosen papers’ evaluation relied on various evaluation criteria, considering the diverse methodologies used in this review. The critical appraisal skill program (CASP, 2018) checklists were used to assess the rigor, credibility, and relevance of the qualitative investigations. The CASP consists of ten questions ranging from 1 to 9, with response options of “Yes,” “No,” or “Cannot tell” (Table 3). For item 10, the authors discussed and jointly determined the appropriate response.

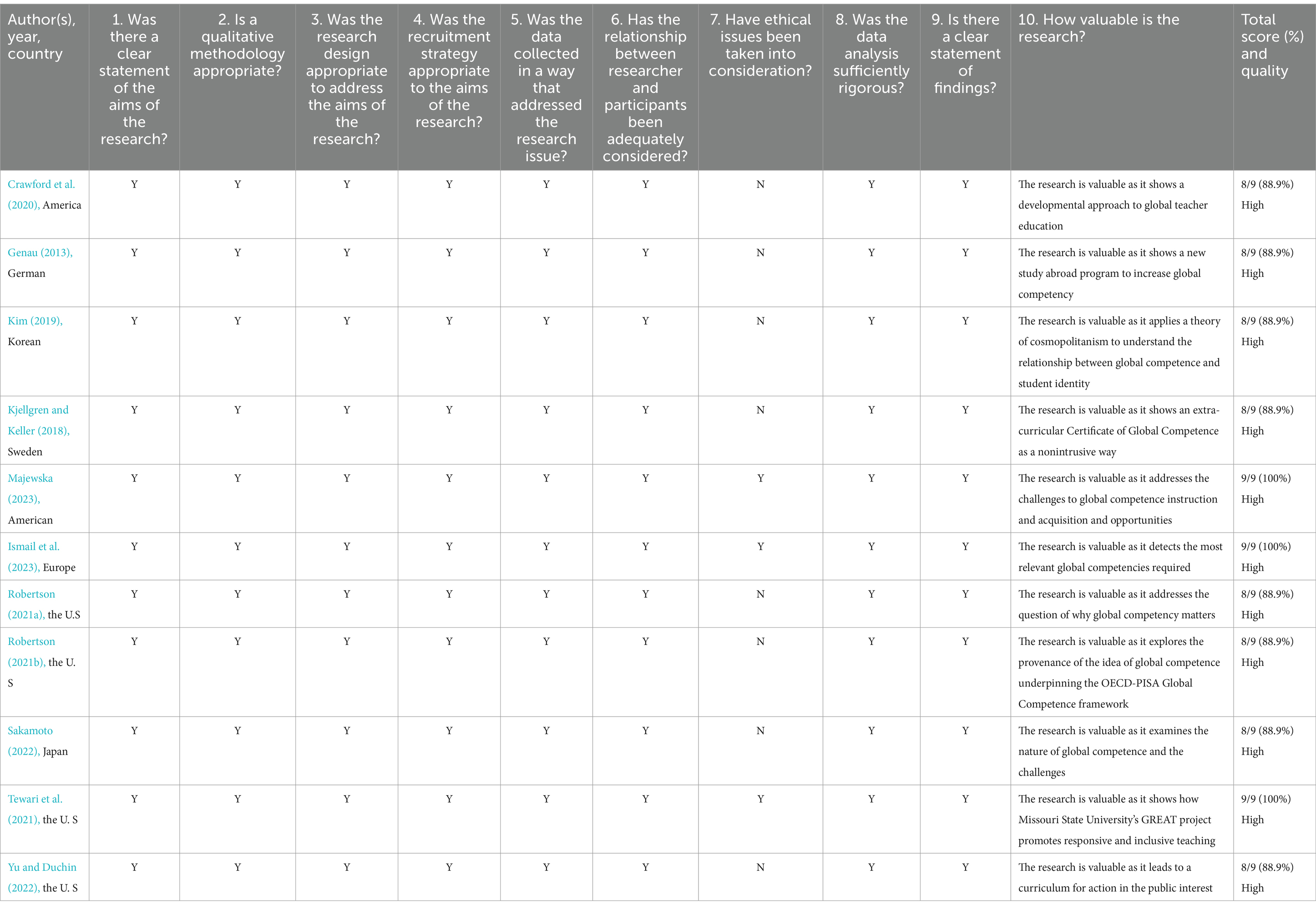

The Critical Appraisal Checklist (CEBM, 2014) was utilized to evaluate the cross-sectional quantitative study. This checklist comprises 12 queries, offering response options of “Yes,” “No,” or “Cannot tell.” The checklist encompasses questions that assess various aspects, such as the study’s design, subject selection, sample representativeness, measurement reliability, and conducted statistical analysis (Table 4).

Consistent procedures were followed for all evaluations to assess the overall score and quality of the articles included in this systematic review. Tables 3–4 present the processes and calculations. Initially, the cumulative score for each column was calculated and subsequently divided by the overall score. Then, these scores were converted into percentages to categorize the articles’ quality. The articles were then classified into three categories based on the percentage distribution and range. Finally, studies with percentages ranging from 80 to 100% ranked as high quality, from 60 to 79% as good quality, and with percentages below 60% as low quality.

2.2.3 Data extraction

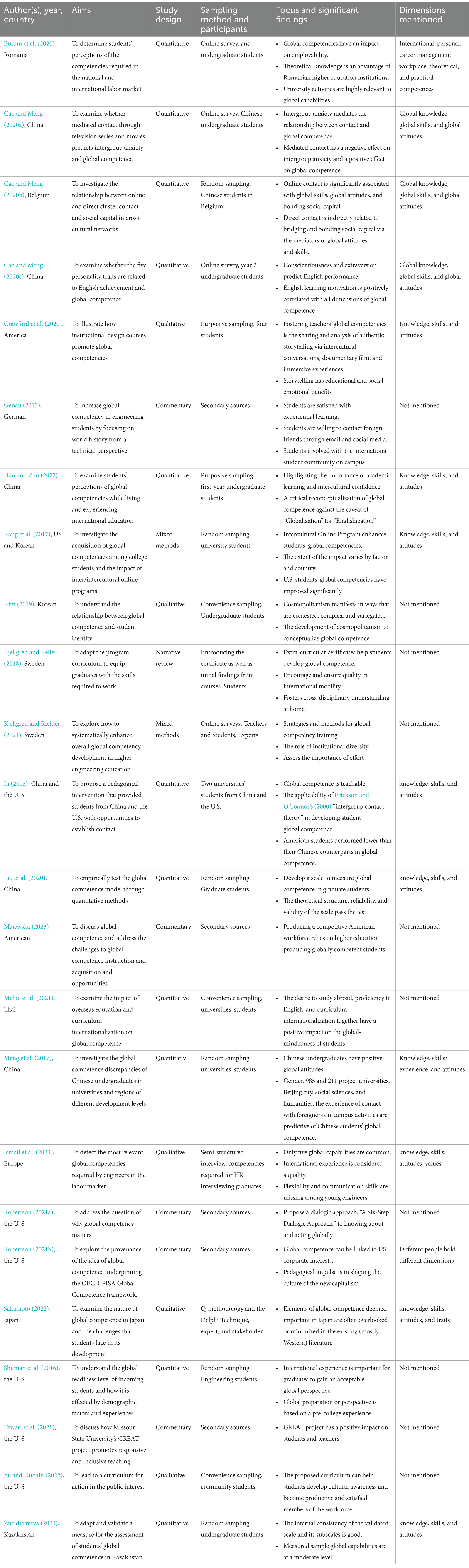

The study employed the guidelines proposed by Ma et al. (2017) to extract and organize the investigations’ key characteristics and significant results. Several important attributes, such as the author(s), publication year, country of research, investigation objectives, study design, sampling method, individuals involved, focus and relevance of findings, and quality level were included. During the initial phase, the studies were classified and condensed the studies according to their qualitative or quantitative methodology. Table 5 provides a comprehensive summary and categorization of the features and significant conclusions drawn from these investigations.

The review process began with examining 271 papers obtained from the search (60 from WoS and 211 from Scopus) against the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. During the initial screening, 43 duplicate articles were identified, and 185 articles were excluded due to their failure to meet the inclusion criteria. Subsequently, the remaining 43 articles underwent a thorough evaluation based on quality criteria to ensure that they aligned with the inclusion and exclusion criteria, thereby guaranteeing the selected works’ quality for addressing the research questions. By applying a set of quality questions as criteria, 19 articles were eliminated, resulting in a final selection of 24 articles for analysis and addressing the research questions.

Figure 1 visually represents the data extraction procedure using the PRISMA flow (Moher et al., 2009).

3 Findings and discussion

This section presents the results of the systematic literature review (SLR) structured according to the research questions posed, providing answers through the analysis of the selected articles.

3.1 Definitions of global competence within the context of higher education

A total of 24 selected articles in this review were examined to provide clarification on the definition of global competence. Among these articles, 10 cited both previous research and international organization documents to define global competence. Three articles relied solely on documents from international organizations, while nine publications based their definitions solely on research. Two publications did not mention a specific source for their definition.

In the selected literature, it was common for researchers to refer to the definition of global competence as proposed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) or other organizations. The OECD defined global competence as “the ability to look at local, global, and intercultural issues, to understand and value other people’s points of view and worldviews, to interact with people from different cultures in an open, appropriate, and effective way, and to work for collective well-being and sustainable development” (OECD, 2018). Nine of the chosen publications used this definition.

Additionally, three publications referenced the definition of global competence provided in the book “Educating for Global Competence: Preparing Our Youth to Engage the World” by Mansilla and Jackson (2011). This book emphasized the importance of integrating global competence into education and defines it as “the capacity and disposition to understand and act on issues of global significance” (Mansilla and Jackson, 2011).

Scholarly research also contributed to the definition of global competence. Among the selected literature, 19 publications referred to previous research, with many citing the work of Hunter and Reimers. Hunter et al. (2006) used Delphi techniques to define global competence as “having an open mind while actively seeking to understand cultural norms and expectations of others, leveraging this gained knowledge to interact, communicate, and work effectively outside one’s environment.” Reimers (2009) defined global competence as having three interdependent dimensions: a positive disposition toward cultural difference and a framework of global values; language proficiency beyond one’s dominant language; and deep knowledge and understanding of global topics and the process of globalization, along with critical and creative thinking skills to address global challenges.

Furthermore, five publications in the review discussed the similarities or overlaps in meaning between global competence and other terms such as “intercultural competence,” “global perspective,” “global awareness,” and “global citizenship.” This indicates that a unified definition of global competence is still under development.

Some scholars argued that the OECD-PISA definition possesses the most authority and should serve as the unified definition of global competence in academia, based on a combination of organizational reports and research. They highlighted the contributions of previous scholars to shaping the OECD-PISA global competence framework. However, there are also scholars who believed that these definitions may be biased toward a Western perspective and may not adequately consider globalization, particularly in Eastern contexts. Additionally, even within the OECD, different organizers or stakeholders approached global competence from a US-centric perspective, which may limit its adaptability to other cultural contexts (Robertson, 2021a; Sakamoto, 2022).

3.2 Dimensions commonly used to assess the global competence of university teachers and students

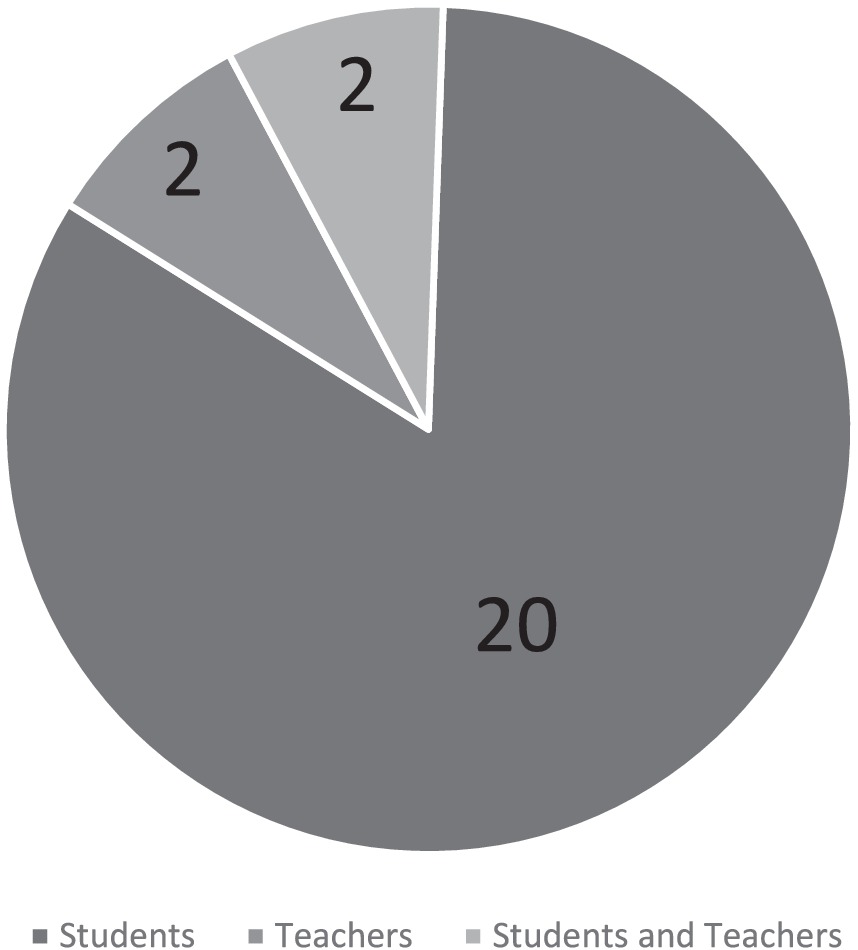

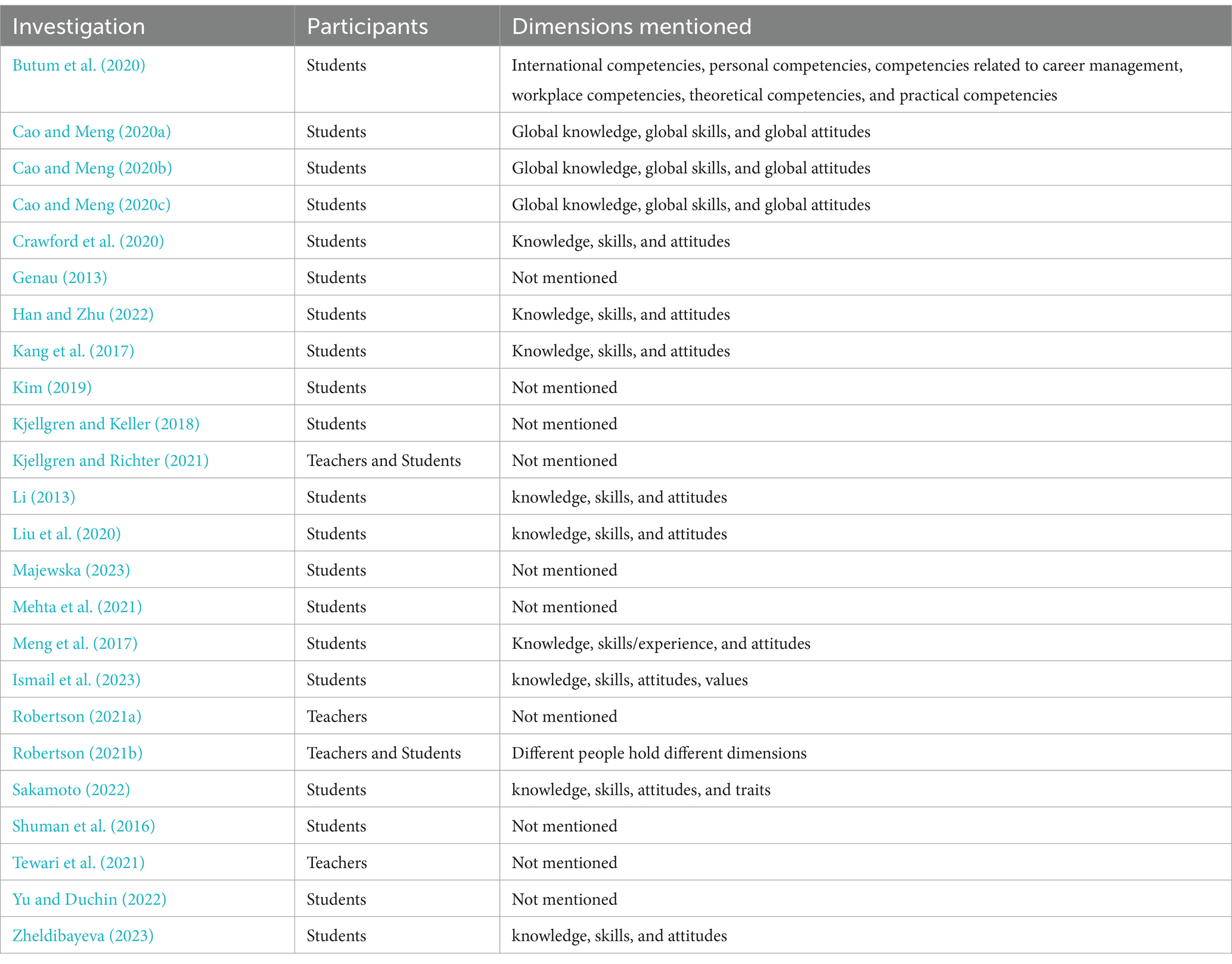

Among the 24 selected publications, a variety of instruments with different dimensions were used. Figure 2 represents the types of samples used before presenting the results concerning the dimensions commonly used to assess the global competence of university teachers and students. The corresponding articles can be found in the Appendix.

Of the 24 selected publications, 20 focused on student participants, 2 focused on teacher participants, and 2 studied both teachers and students.

The selected publications employ various aspects and perspectives to assess the global competence of both students and teachers, as presented in Table A in the appendix. Most publications used surveys as their research method. The analysis and comparison of the dimensions outlined in these surveys revealed that 10 out of the 24 selected publications embraced Hunter’s global competence dimensions, comprising knowledge, skills, and attitudes (Hunter et al., 2006). Sakamoto expanded on Hunter’s three dimensions by adding traits, resulting in the following four dimensions: knowledge, skills, attitudes, and traits (Sakamoto, 2022). Similarly, Ortiz-Marcos et al. (2020) referenced the four dimensions of the OECD framework, which include knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values.

Some scholars developed their own evaluation dimensions based on their research orientation and established tools using different theoretical frameworks. For instance, Butum et al. (2020) categorized global competence into six categories: international competences, personal competences, competences related to career management, workplace competences, theoretical competences, and practical competences. This observation aligns with Robertson’s findings that different scholars employ different dimensions to evaluate global competence (Robertson, 2021b).

3.3 Research purposes, methodologies, and outcomes explored in the last decade on global competence in higher education

To present a comprehensive overview of the advancements made in research on global competence over the past decade, an analysis of the research objectives, methodologies, and outcomes to gather relevant information was conducted.

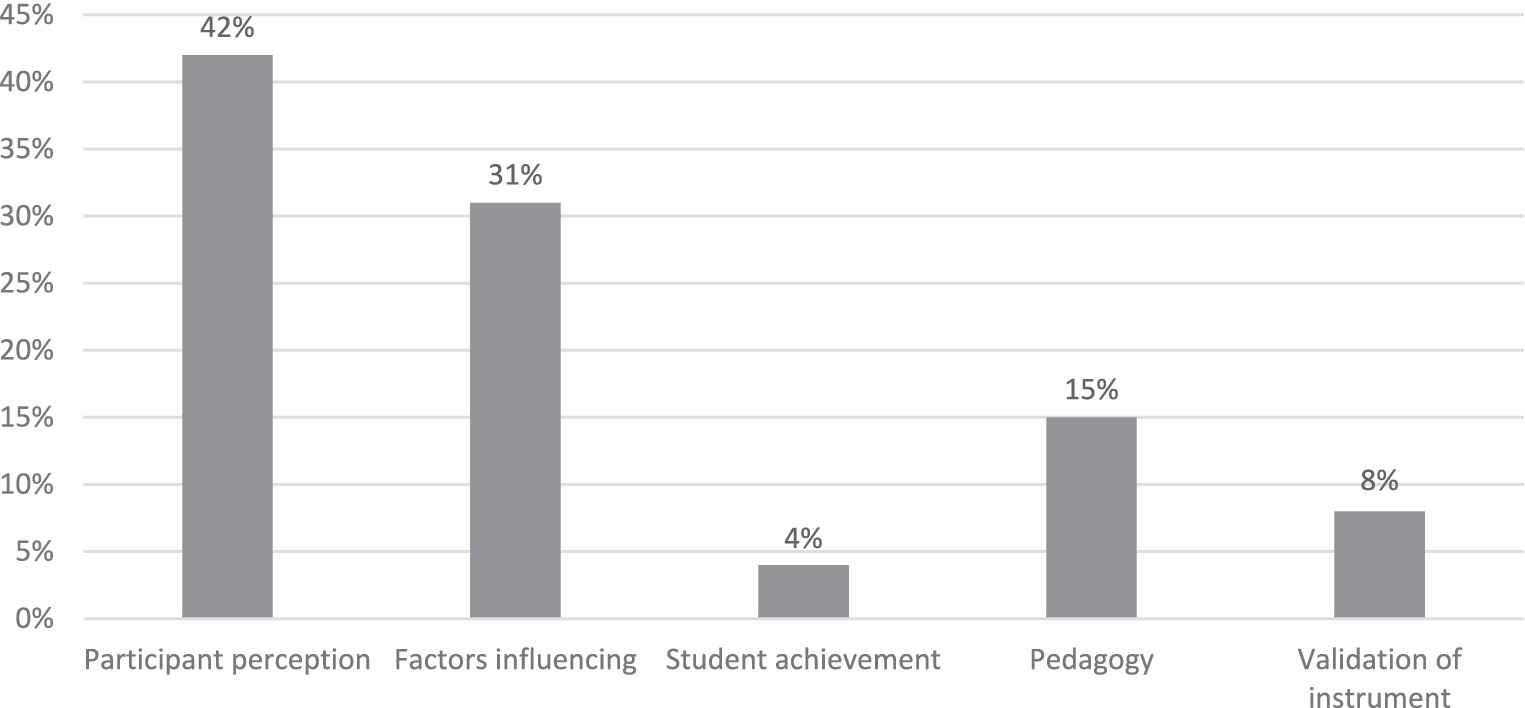

3.3.1 Research purposes

The categorization of the selected publications was based on their research purposes. The first category aimed to assess participants’ perceptions and levels of global competence in higher education. These articles aimed to evaluate participants’ understanding and level of global competence within the context of higher education. The second category involved investigating the factors that influence global competence. These publications investigated the factors affecting global competence and how they differ across individuals. The third category centered on evaluating the impact of global competence on student achievement. Articles in this category assessed the effect of global competence on students’ academic performance. The fourth category involved analyzing the pedagogical approaches used to develop global competence. These articles presented different teaching methods and strategies employed to cultivate global competence. Lastly, the fifth category examined the reliability and validity of global competence-related instruments. Articles in this category focused on measuring the reliability and validity of the questionnaires used to evaluate global competence. Figure 3 presents the results of these categorizations.

In this category, 42% (n = 11) of the selected publications most frequently represented the research purpose of investigating the participants’ perceptions and their level of global competence. The evaluation of students’ perceptions was done from multiple perspectives. For example, Butum and Ortiz-Marcos explored perceptions of global competence and international labor market needs (Butum et al., 2020; Ortiz-Marcos et al., 2020). Han and Zhu (2022) examined students’ perceptions of global competence as they lived and experienced international education. Sakamoto and Shuman assessed college students’ perceptions of their level of global competence and what college students need to be globally competitive (Shuman et al., 2016; Sakamoto, 2022). Genau and Tewari discussed perspectives on global education programs and practices (Genau, 2013; Tewari et al., 2021).

While 31% (n = 8) of the selected publications also investigated factors that could influence global competence, marking the second-highest level of research. For example, Cao and Meng examined whether mediated exposure through TV dramas and movies predicts intergroup anxiety and global competence (Cao and Meng, 2020a). They also investigated whether demographic variables (i.e., age, gender, length of stay in Belgium, professional and academic level) are associated with global competence (Cao and Meng, 2020b). Additionally, they examined whether five personality traits are associated with English language achievement and global competence (Cao and Meng, 2020c). Moreover, Kang et al. (2017) examined the effect of a cross-cultural online program on their global competence. Mehta et al. (2021) examined the impact of overseas education and curriculum internationalization on global awareness. Meng et al. (2017) discussed the impact of domestic internationalization efforts and student motivation on global competence. Shuman et al. (2016) explored the impact of demographic factors and pre-university experiences on freshman global competence.

One publication (Cao and Meng, 2020c) evaluated the effectiveness of global competence on students’ achievement. They explored the predictive role of the Big Five personality traits (conscientiousness, neuroticism, extraversion, openness, and agreeableness) in English achievement and global competence. The findings indicated that extraversion and motivation to learn can synergistically contribute to better results in learning English and acquiring global knowledge.

Four of the selected publications examined pedagogical approaches to global competence. Crawford et al. (2020) described how an instructional design course at one university promotes global competence, providing four student case studies as illustrative examples of how such a course can support students in developing global competence. Li (2013) proposed a teaching intervention that creates opportunities for students from China and the United States to establish virtual connections and collaborate on international business-related research papers. Kjellgren and Keller (2018) adapted program curricula to equip graduates with the skills required for effective and ethical work in socially and culturally diverse environments. Yu and Duchin (2022) developed a student project based on existing courses to enhance students’ understanding of the local social context through community and global engagement, fostering comprehension of the Sustainable Development Goals and the development of technical skills. These courses are essential for nurturing cultural awareness, enabling students to thrive in a multicultural world and become productive and fulfilled members of the workforce.

Finally, two selected articles validated instruments related to global competence. Liu et al. (2020) employed quantitative methods to test global competence models empirically. Zheldibayeva (2023) aimed to adapt the global competence scale to local conditions and examine the validity and reliability of the Kazakh version of the scale as a tool for measuring the global competence of Kazakh students.

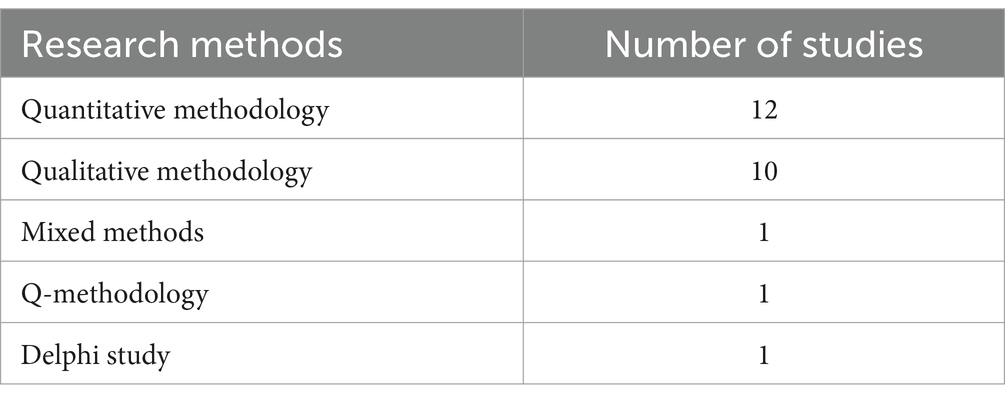

3.3.2 Research methods

The analysis of the research methods used in the selected publications was undertaken. The findings are presented in Table 6.

Among the selected publications, most scholars investigated global competence-related content using quantitative and qualitative methods. Specifically, 12 publications utilized quantitative methods, with data collection conducted through questionnaires. Ten articles employed qualitative methods, specifically in-depth semi-structured student interviews, for survey research (Kim, 2019; Crawford et al., 2020; Ortiz-Marcos et al., 2020). One of the articles employed a mixed-method approach, incorporating both quantitative and qualitative techniques. Kjellgren and Richter (2021) utilized interviews and questionnaires to investigate ways to enhance the systematic development of global competence in higher engineering education. To explore perceptions of what Japanese university students need to be globally competitive, Sakamoto (2022) employed Q-methods and Delphi techniques to identify and understand prevailing expert and stakeholder opinions.

3.3.3 Research outcomes

The study also involved analyzing the research outcomes of the articles that investigated students’ and teachers’ perceptions and assessed their level of global competence (see Table 7).

Five articles mentioned the challenges and areas for improvement in developing global competence. For example, Meng et al. (2017) found that Chinese college students had a positive global attitude but lacked sufficient global knowledge. Robertson (2021b) contended that the narrow presentation of global competence stems from its conceptual basis, which aligns with American corporate interests, as well as its pedagogical focus on shaping the culture of the new capitalism. Another study (Sakamoto, 2022) found that Japanese students struggle to develop global competence due to factors such as limited autonomy, limited self-expression, and insufficient critical thinking to overcome ethnocentrism.

Furthermore, six studies focused on analyzing the factors that influence global competence. These six studies listed factors such as personal characteristics, experience studying abroad, English proficiency, exposure to cross-cultural online communication, internationalized curriculum, school ranking, and contact with individuals from foreign cultures were listed in these six studies. For example, Cao and Meng (2020a) found that exposure to foreign TV series and films has a positive impact on global capabilities. Researchers found that extraversion and openness positively predict all three dimensions of global competence (global attitudes, skills, and knowledge), while agreeableness positively predicts global attitudes (Cao and Meng, 2020c). Another study suggested that intercultural online programs generally increase the global competence of participating students, but the extent of the impact varies across dimensions and countries (Kang et al., 2017). According to Mehta et al. (2021), the desire to study abroad, English proficiency, and curriculum internationalization have a positive impact on global competence. Meng et al. (2017) found that gender, enrollment in 985 and 211 universities in Beijing, social sciences and humanities, experience of contact with foreigners in campus activities, enrollment in internationalization-related courses, and student motivation were predictors of Chinese students’ global competence. Shuman et al. (2016) concluded that building on pre-college experience and encouraging students to have multiple international experiences while in college is key to gaining a relatively high level of global readiness or perspective.

Li (2013) asserted that effective teaching of global competencies is possible in the realm of pedagogical approaches. One recommended intervention program for enhancing global competencies is to incorporate cross-cultural education in the classroom. Yu and Duchin (2022) employed a combination of top-down and bottom-up teaching methods to expand students’ cultural awareness and sensitivity. Their instructional approach entailed dividing the course into four distinct areas: “Food Aid, Assistance to the Elderly, Assistance to Children and Youth, and Activities to Enrich Community Life.”

Regarding the validation of global competencies, Liu et al. (2020) developed a comprehensive three-dimensional scale known as the Global Competence Scale for graduate students (GCSG) to validate global competence-related competencies. This scale has gained recognition as a reliable tool for measuring postgraduate global competencies. This scale underwent a rigorous evaluation to assess its reliability and validity. Furthermore, Zheldibayeva (2023) conducted a study that tested a validated global competence scale exhibiting strong internal consistency and satisfactory data fit.

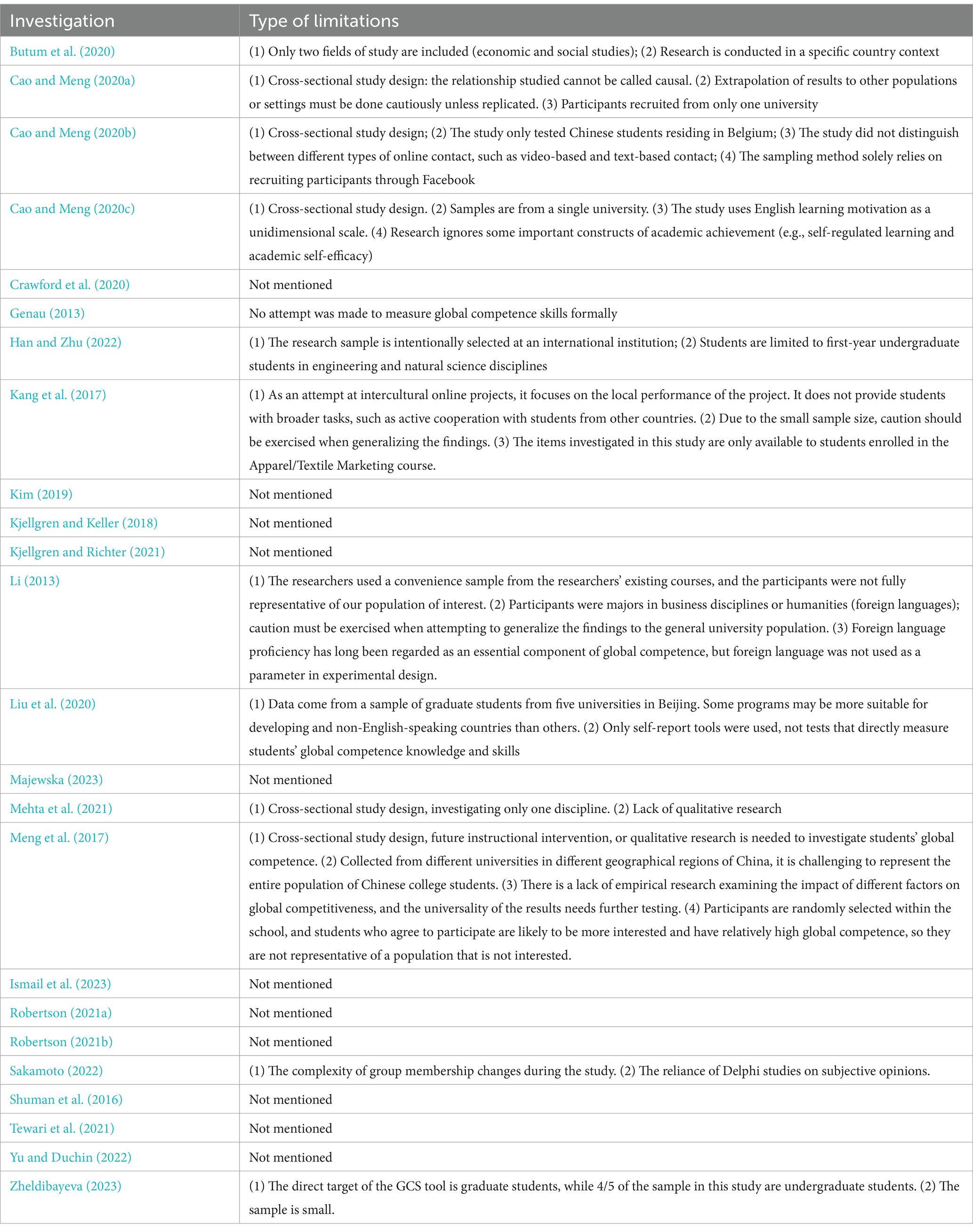

3.4 Limitations of reviewed studies on global competence within higher education

Table 5 presents the types of limitations identified in the investigations. The analysis showed that the sample size was the most common limitation among the 24 selected research studies, appearing in 10 studies (n = 10). Additionally, the cross-sectional study design emerged as a frequently encountered research limitation, appearing in 5 articles. Notably, 12 articles exhibited multiple research limitations, whereas 11 selected articles did not specify any research limitations.

It can be seen from Table 6 that: (1) the limitation of most studies is small samples, such as samples from a specific school or a single university. In the future, it is recommended to collect data from different sources and further validate the global competence scale with a larger sample size to improve its universality and usability. (2) Many studies also pointed out the cross-sectional study design. Due to the cross-sectional study design, the research results need to be interpreted with caution as a causal relationship. In the future, conducting longitudinal research on global competence, investigating global competence through teaching intervention, or conducting qualitative research, such as follow-up testing, to reveal the causal relationship between these variables is recommended.

4 Strengths and limitations

This systematic review has numerous noteworthy strengths. The review mostly followed the strict and thorough methods specified by Cochrane criteria. The systematic review had a well-defined scope, which included predetermined criteria for the study population, outcomes, and research design. The review utilized a comprehensive and systematic literature search to achieve comprehensiveness, implementing a pre-established search strategy. In addition, a complementary manual search was performed by examining the reference lists of the obtained papers and review articles that only discussed global competence in higher education. The search strategy reporting complied with the specifications mentioned in the PRISMA declaration. The data extraction procedure was carried out autonomously by the first and third authors, with any discrepancies handled by consensus or consultation with the second author in cases where consensus could not be achieved.

Despite adhering to the robust systematic review guidelines and protocols, the present systematic literature review does exhibit a few limitations. This literature review systematically presents the current state of research through validated studies. It encompasses an overview of studies included in two databases, Web of Science and Scopus, from the past 10 years (2013–2023). It should be noted that this review only examined publications from these two selected databases, and thus, not all publications on the subject were accounted for. Furthermore, the years were limited to 2013–2023 to emphasize recent findings. Notably, the search was constrained to articles published solely in English to ensure the inclusivity of international literature and compensate for the researchers’ limited proficiency in multiple languages.

5 Conclusion

This systematic review provides a comprehensive overview of global competence in higher education. It examines how global competence is defined and used in higher education settings and presents an analysis of current research on global competence, including the research purpose, methodologies, instruments, outcomes, and limitations.

The review highlights that the definition of global competence in the reviewed publications is generally broad, drawing on international organization documents and related research. International organizations commonly use the definitions proposed by the OECD and the EdSteps Global Capability Working Group, while scholars frequently cite Hunter and Reimers’ definition. However, it is essential to note that some publications compare global competence with other related terms, such as intercultural competence.

The review of the global competence assessment indicates a preference for studying students rather than teachers. Most studies utilize Hunter’s definition of global competence: knowledge, skills, and attitudes.

The selected publications’ research objectives focus primarily on investigating global competence among teachers and students and the factors influencing its development. A significant portion of the research aims to survey and assess participants’ perceptions, level of global competence, and related factors. However, the number of studies exploring the impact of global competence on student achievement is limited.

Regarding research methodology, most selected publications rely exclusively on quantitative or qualitative methods, with mixed methods being less common. The past decade’s outcomes indicate that university teachers and students require comprehensive improvement in global competence. While individuals may exhibit satisfactory global attitudes, they may still lack global knowledge when faced with complex problems. Factors influencing student global competence include personal characteristics, study abroad experiences, English proficiency, cross-cultural online communication, internationalized courses, school rankings, and contact with people from foreign cultures.

To enhance global competence in higher education, it is crucial to consider the positive correlation between global competence and student achievement. Appropriate teaching methods, such as curriculum intervention plans, can contribute to developing higher-level global competence. The review also emphasizes the importance of developing validation tools that facilitate the timely measurement of global competence across different dimensions for university teachers and students.

The limitations identified in the reviewed publications primarily relate to the data collection methods and sample sizes. Future research should address these limitations by conducting longitudinal studies and considering larger sample sizes for experimental participants.

6 Identified gaps and future research

This systematic review highlights several areas for further research and provides valuable insights into global competence in higher education. First, it is important to recognize that the definition of global competence is still evolving and is predominantly influenced by Western perspectives. Therefore, there is a need for more research that focuses on defining and measuring global competence in different cultural contexts.

Secondly, although the selected articles primarily assessed students’ levels of global competence, it is crucial to recognize that global competence development does not depend solely on students. Teachers have an essential role to play in fostering students’ global competence.

Thirdly, while most articles examined perceptions and levels of global competence and the factors that influence its acquisition, it is equally important to explore how it can be effectively integrated into teaching and learning practices.

Finally, it is worth noting that many articles in the review relied solely on quantitative or qualitative research methods. While these approaches have their merits, using mixed research methods may yield more comprehensive results.

This systematic review presents valuable insights into global competence in higher education. However, further research is needed to define and measure global competence in different cultural contexts, recognize the role of teachers in fostering students’ global competence, explore effective integration of global competence into teaching practices, and consider the use of mixed research methods for a more comprehensive understanding of the topic.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

GJ: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZH: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HMH: Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Butum, L. C., Nicolescu, L., Stan, S. O., and Găitănaru, A. (2020). Providing sustainable knowledge for the young graduates of economic and social sciences. Case study: comparative analysis of required global competences in two Romanian universities. Sustain. For. 12:5364. doi: 10.3390/su12135364

Cao, C., and Meng, Q. (2020a). Chinese university students’ mediated contact and global competence: moderation of direct contact and mediation of intergroup anxiety. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 77, 58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2020.03.002

Cao, C., and Meng, Q. (2020b). Effects of online and direct contact on Chinese international students’ social capital in intercultural networks: testing moderation of direct contact and mediation of global competence. High. Educ. 80, 625–643. doi: 10.1007/s10734-020-00501-w

Cao, C., and Meng, Q. (2020c). Exploring personality traits as predictors of English achievement and global competence among Chinese university students: English learning motivation as the moderator. Learn. Individ. Differ. 77:101814. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2019.101814

CASP. (2018). CASP qualitative checklist. Available at: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

CEBM. (2014). Critical appraisal questions for a cross-sectional study. Available at: https://www.cebma.org/

Chadegani, A. A., Salehi, H., Yunus, M. M., Farhadi, H., Fooladi, M., Farhadi, M., et al. (2013). A comparison between two Main academic literature collections: web of science and Scopus databases. Asian Soc. Sci. 9:18. doi: 10.5539/ass.v9n5p18

Crawford, E. O., Higgins, H. J., and Hilburn, J. (2020). Using a global competence model in an instructional design course before social studies methods: a developmental approach to global teacher education. J. Soc. Stud. Res. 44, 367–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jssr.2020.04.002

Deardorff, D. K., and Arasaratnam-Smith, L. A. (2017). Intercultural competence in higher education. International approaches, assessment and application. 26.

Erickson, J. A., and O’Connor, S. E. (2014). Service-learning: Does it promote or reduce prejudice?. In Integrating service learning and multicultural education in colleges and universities. pp. 59–70. Routledge.

Fuchs, C. (2018). Industry 4.0: the digital German ideology. J. Glob. Sustain. Info. Soc. 16, 280–289. doi: 10.31269/triplec.v16i1.1010

Genau, A. (2013). Developing knowledge of world history in engineering students as a component of global competency. 2013 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition Proceedings, 23.

Gough, D., Oliver, S., and Thomas, J. (2017). An introduction to systematic reviews. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Guo-Brennan, L. (2022). “Global competence education for all in 21st–century higher education” in Preparing Globally Competent Professionals and Leaders for Innovation and Sustainability, IGI Global. vol. 125–144. doi: 10.4018/978-1-6684-4528-0

Han, S., and Zhu, Y. (2022). (Re) conceptualizing’global competence’ from the students’ perspective. Asia Pacific J. Educ. 1–13, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/02188791.2022.2148091

Hunter, B., White, G. P., and Godbey, G. C. (2006). What does it mean to be globally competent? J. Stud. Int. Educ. 10, 267–285. doi: 10.1177/1028315306286930

Ismail, W. N., Alsalamah, H. A., Hassan, M. M., and Mohamed, E. (2023). AUTO-HAR: an adaptive human activity recognition framework using an automated CNN architecture design. Heliyon 9:e13636. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13636

Kang, J. H., Kim, S. Y., Jang, S., and Koh, A.-R. (2017). Can college students’ global competence be enhanced in the classroom? The impact of cross-and inter-cultural online projects. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 1–11, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2017.1294987

Kim, J. J. (2019). Conceptualising global competence: situating cosmopolitan student identities within internationalising south Korean universities. Glob. Soc. Educ. 17, 622–637. doi: 10.1080/14767724.2019.1653755

Kitchenham, B., and Charters, S. (2007). Guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering. Available at: https://userpages.uni-koblenz.de/laemmel/esecourse/slides/slr.pdf.

Kjellgren, B., and Keller, E. (2018). Introducing global competence in Swedish engineering education. Front. Educ. Conf. 2018, 1–5. doi: 10.1109/FIE.2018.8659122

Kjellgren, B., and Richter, T. (2021). Education for a sustainable future: strategies for holistic global competence development at engineering institutions. Sustain. For. 13:11184. doi: 10.3390/su132011184

Li, H., Khattak, S. I., and Jiang, Q. (2021). A qualitative assessment of the determinants of faculty engagement in internationalization: a Chinese perspective. SAGE Open 11:215824402110469. doi: 10.1177/21582440211046935

Li, Y. (2013). Cultivating student global competence: a pilot experimental study: cultivating student global competence. Decis. Sci. J. Innov. Educ. 11, 125–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4609.2012.00371.x

Liu, Y., Yin, Y., and Wu, R. (2020). Measuring graduate students’ global competence: instrument development and an empirical study with a Chinese sample. Stud. Educ. Eval. 67:100915. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2020.100915

Ma, P. H., Chan, Z. C., and Loke, A. Y. (2017). The socio-ecological model approach to understanding barriers and facilitators to the accessing of health services by sex workers: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 21, 2412–2438. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1818-2

Majewska, I. A. (2023). Teaching global competence: challenges and opportunities. Coll. Teach. 71, 112–124. doi: 10.1080/87567555.2022.2027858

Mansilla, V. B., and Jackson, A. W. (2011). Educating for global competence: preparing our youth to engage the world. ASCD. 21. doi: 10.13140/2.1.3845.1529

Mehta, A. M., Khalid, R., Serfraz, A., and Raza, M. (2021). The effect of studying abroad and curriculum Iinternationalization on global mindedness of university students: the mediating role of the English language. TESOL Int. J. 16, 106–131.

Meng, Q., Zhu, C., and Cao, C. (2017). An exploratory study of Chinese university undergraduates’ global competence: effects of internationalisation at home and motivation: Chinese university undergraduates’ global competence. High. Educ. Q. 71, 159–181. doi: 10.1111/hequ.12119

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., and Altman, D. G.PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 339, 264–269. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535

OECD. (2018). Preparing our youth for an inclusive and sustainable world: The OECD PISA global competence framework. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/education/Global-competency-for-an-inclusive-world.pdf

Oliver, W. H. (2022). “Global initiatives within the 4IR, and the role of higher education” in Global initiatives and higher education in the fourth industrial Revolution. ed. E. Oliver, Vol. 27 (Johannesburg: UJ Press).

Ortiz-Marcos, I., Breuker, V., Rodríguez-Rivero, R., Kjellgren, B., Dorel, F., Toffolon, M., et al. (2020). A framework of global competence for engineers: the need for a sustainable world. Sustain. For. 12:9568. doi: 10.3390/su12229568

Reimers, F. (2009). Educating for global competency. edited by Cohen, J., and Malin, M., International perspectives on the goals of universal basic and secondary education, 22, 183–202. New York: Routlege Press.

Robertson, S. L. (2021a). Global competences and 21st century higher education – and why they matter. Int. J. Chin. Educ. 10:221258682110103. doi: 10.1177/22125868211010345

Robertson, S. L. (2021b). Provincializing the OECD-PISA global competences project. Glob. Soc. Educ. 19, 167–182. doi: 10.1080/14767724.2021.1887725

Saito, H. (2019). Editorial introduction: re-envisioning education in a globalizing world. Youth Global. 1, 197–209. doi: 10.1163/25895745-00102001

Sakamoto, F. (2022). Global competence in Japan: what do students really need? Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 91, 216–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2022.10.006

Sälzer, C., and Roczen, N. (2018). Assessing global competence in PISA 2018: challenges and approaches to capturing a complex construct. Int. J. Develop. Educ. Global Learn. 10, 5–20. doi: 10.18546/IJDEGL.10.1.02

Shliakhovchuk, E. (2019). After cultural literacy: new models of intercultural competency for life and work in a VUCA world. Educ. Rev. 73, 229–250. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2019.1566211

Shuman, L., Clark, R., Streiner, S., and Besterfield-Sacre, M. (2016). Achieving global competence: are our freshmen already there? 2016 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition Proceedings, 26505

Tewari, S., Zhang, P., and Zhuang, Y. (2021). Achieving domestic internationalization and global competence through on-campus activities and globally responsive education. 2021 ASEE Virtual Annual Conference Content Access Proceedings, 36640

Yu, Y., and Duchin, F. (2022). Building a curriculum to Foster global competence and promote the public interest: social entrepreneurship and digital skills for American community college students. Commun. College J. Res. Prac. 48, 164–174. doi: 10.1080/10668926.2022.2064374

Zha, Q., and Wu, H. (2021). Conceptualization and development of global competence in higher education: The case of China. Academic Praxis. 1, 18–36.

Zheldibayeva, R. (2023). The adaptation and validation of the global competence scale among educational psychology students. Int. J. Educ. Prac. 11, 35–46. doi: 10.18488/61.v11i1.3253

Appendix

TABLE A Participants and dimensions of global competence were mentioned in the selected investigations.

Keywords: global competence, higher education, internationalization, PRISMA protocol, systematic literature review

Citation: Jiaxin G, Huijuan Z and Md Hasan H (2024) Global competence in higher education: a ten-year systematic literature review. Front. Educ. 9:1404782. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1404782

Edited by:

Carlos Saiz, University of Salamanca, SpainReviewed by:

Irving Samadhi Aguilar, Autonomous University of the State of Morelos, MexicoYamina El Kirat El Allame, Mohammed V University in Rabat, Morocco

Copyright © 2024 Jiaxin, Huijuan and Md Hasan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Howlader Md Hasan, bWRoYXNhbmhvd2xhZGVyQGxuLmhr

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Guo Jiaxin1,2†

Guo Jiaxin1,2† Howlader Md Hasan

Howlader Md Hasan