- Department of Education, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

Introduction: For decades, oral presentations have become a common method of assessment in language learning classrooms. Nonetheless, anxiety is a persistent negative feeling pervasive in EFL learners. Although applied linguistic research suggests that there is a relationship between motivation and anxiety, the nature and direction of this relationship remain inconsistent.

Methods: To tackle this concern, this mixed-methods longitudinal study aimed to investigate the growth trajectories of Chinese EFL learners’ L2 motivation and anxiety in oral presentations. The participants were 171 second-year undergraduate medical students who attended an English for Academic Purposes (EAP) course. They delivered four oral presentations and reported their L2 motivation and anxiety levels in questionnaire surveys.

Results: (1) As the number of EFL learners giving oral presentations increased, the L2 motivation levels increased, and the anxiety levels decreased. (2) Those who were initially more anxious about giving oral presentations had higher decrease rates during the four oral presentations. (3) There was co-development but inverse relationships between ideal L2 self and anxiety and between ought-to L2 self and anxiety, although a complete parallel process model was not established.

Discussion: These findings suggest that students’ perceptions of L2 motivation interact with anxiety levels over time but in a sophisticated fashion. Finally, pedagogical implications for EFL oral presentation instruction are provided.

1 Introduction

As a teacher of undergraduate EAP courses, whenever I announce a presentation assignment, regardless of how much it contributes to their final grade, there is always a chorus of complaints and visible terror on students’ faces. Some students clench their fists, widen their eyes, and gasp sharply. Indeed, delivering oral presentations in a public setting has posed great challenges to them in terms of their foreign language proficiency, psychological status, and academic levels. Thus, I often ponder why students are so fearful of giving oral presentations and how we can alleviate their anxiety levels to help them perform better in an oral presentation task.

Research has shown that anxiety and motivation, as recurring traits among learners, have demonstrated their consistent roles in shaping language learning performance (Ahmetović et al., 2020; Alamer and Almulhim, 2021; Wu, 2022; Goldfrad et al., 2023; Papi et al., 2023; Papi and Khajavy, 2023). As learners navigate the intricate landscape of linguistic proficiency, the dynamics of motivation drive their pursuit of excellence, while the subtle undercurrents of anxiety wield the power to both propel and hinder their performance. Delving into the intricate nexus of these psychological forces may illuminate the multifaceted nature of EFL oral presentations and offer educators a profound vantage point from which to enhance pedagogical strategies and foster optimal language learning experiences.

This study addresses a research gap in the existing research on the dynamic interplay between L2 motivation and anxiety among EFL learners during oral presentations. Prior research predominantly relies on cross-sectional data, which fails to capture the evolving trajectories of these psychological states over time. By employing LGCM, this research aims to unravel the complex, time-bound interactions between L2 motivation and anxiety, offering insights into how these factors concurrently develop and influence language performance in an academic setting. By doing so, it aims to shed light on the nuanced and evolving interplay between these crucial psychological aspects, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of their profound implications for EFL learners’ oral presentation performance.

2 Literature review

2.1 EFL oral presentations

Oral presentations, extensively utilized by language instructors, hold significant roles in EFL classrooms and has elicited notable research attention (Mak, 2019). Oral presentations, also referred to as public speaking, oratory, or oration, constitute a hands-on, interactive form of communication involving speakers, audiences, and a specific venue. Typically, a speaker prepares an oral presentation with an outline, visual aids, notes, or a script, delivering it to a designated audience. With the dual aims of conveying information and catalyzing further communication, oral presentations are commonly delivered in environments where interaction is expected. The aims of conducting L2 oral presentation events include teaching, assessment of language, and information sharing (Jing, 2009; Soureshjani and Ghanbari, 2012; Mabini, 2023). The aptitude for conducting an oral presentation proficiently and coherently in English stands as a coveted objective for numerous EFL learners. Achieving this goal necessitates a comprehensive understanding of the presentation context and audience and proficiency in communication skills tailored to the oral presentation milieu (Soureshjani and Ghanbari, 2012). EFL oral presentations can be delivered in a variety of forms in a language classroom, including but not limited to monolog, videotaped presentation, PowerPoint facilitated delivery, TED Talks, Toastmasters, blended learning, and Pecha Kucha. The latter of these is the focus of the study due to an ability to control for aspects of the presentation length and complexity in a structured format.

Empirical studies have explored the effectiveness of Pecha Kucha presentations in EFL classrooms. For instance, Zharkynbekova et al. (2017) examined how Pecha Kucha presentations improved public speaking in EFL learners. Conducted with 60 university students split into experimental and control groups, the results showed enhanced performance and positive attitudes toward Pecha Kucha among those using it compared to traditional methods. Likewise, de Armijos (2019) conducted an action research at a public university in Guayaquil, Ecuador and explored how the Pecha Kucha presentation style could enhance EFL skills among 45 undergraduate students of A2 and B1 CEFR levels. The study involved observations, interviews, and other data collection methods to assess the impact of Pecha Kucha on students’ oral performance. Results indicated that while Pecha Kucha improved integration of reading, writing, listening, and speaking skills, it also caused anxiety and highlighted challenges in vocabulary and fluency. While the Pecha Kucha presentations were found to enhance various EFL skills, it also notably increased anxiety among students. Coskun (2017) involving 176 EFL students in Hong Kong explored the relationship between public speaking anxiety, self-perceived pronunciation competence, and actual speaking proficiency. Findings revealed that aspects of pronunciation negatively correlated with anxiety, varying by proficiency level, with differing pronunciation goals identified across proficiency groups. The next section will focus on the specific impacts of anxiety in EFL learning environments.

2.2 Anxiety

Anxiety, a sophisticated psychological phenomenon (MacIntyre and Gardner, 1989), has obtained substantial attention and discourse. It is characterized as a state of uneasy anticipation (Rachman, 2002), often accompanied by restlessness, apprehension, perspiration, muscle tension, tremors, fear, and pessimistic thoughts (Barlow, 2002). Within this spectrum, L2 speaking anxiety shares akin symptoms like physical rigidity, sudden confusion despite preparation (Ortega, 2011), diminished cognitive capacity, unforeseen physiological shifts, and undesirable conduct (Hammad and Ghali, 2015). Oral presentation anxiety, akin to public speaking anxiety, encompasses sentiments of shame, embarrassment, and negative self-assessment of public speech (Blöte et al., 2009). For this study, Blöte et al.’s (2009) definition is adopted due to its pertinence to the proposed oral presentation context.

Previous research has demonstrated that EFL learners are experiencing very high levels of anxiety in speaking, especially in oral presentations, and anxiety is associated with the performance of speaking in a second language, with the majority of scholars asserting a negative correlation between anxiety and performance (Amirian and Tavakoli, 2016; Arifin et al., 2023; Barber, 2023). For instance, Ritonga et al. (2020) conducted a mixed-methods study investigating the impact of anxiety on students’ speaking performance, utilizing observation, interviews, and a questionnaire survey. The research involved 220 fifth-semester EFL learners from an Indonesian university. They gaged anxiety levels using the Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS) created by Horwitz et al. (1986), which includes 33 Likert scale items. The researchers observed classes to assess actual performance during teaching and learning sessions. The study reveals that anxiety negatively impacts EFL learners’ speaking performance, with 59% students feeling unprepared and fearful of ridicule, and only 6% felt prepared for English class. This underscores the importance of further research to validate these findings across various educational settings. However, this conclusion must be regarded cautiously. A major limitation of the study is the analysis of questionnaire data, which focused on the descriptive (the average of each questionnaire item) rather than reliability and validity assessments. Additionally, the way L2 speaking performance was operationalized poses issues, as the researcher reported individual errors but not their quantification or type. A proficient L2 learner might make multiple errors while maintaining high fluency and coherence in topic development.

In addition to the FLCAS that measures EFL learners’ language classroom anxiety, McCroskey (1977) developed the 34-item Personal Report of Public Speaking Anxiety (PRPSA), a five-point Likert scale questionnaire to measure language learners’ oral presentation anxiety. Although the PRPSA has been widely referenced, it did not meet the criteria for a valid questionnaire based on confirmatory factor analysis during its initial usage. Several critical issues were identified within this questionnaire. Despite ostensibly having a unidimensional structure, the questionnaire encompassed items that addressed distinct dimensions of anxiety. Compounding these concerns was the scoring methodology, wherein both positively and negatively framed items were aggregated to derive final outcomes.

Anxiety is a psychological construct that can be measured in different ways. Susanto (2022), in a qualitative study, explores Indonesian second-year non-English major EFL learners’ perceptions of the effectiveness of integrating Pecha Kucha in language classrooms, revealing its features, such as re-recording presentations and slide time allocation, as pivotal in reducing anxiety. Likewise, Gurbuz and Cabaroglu (2021) delved into the perspectives of 29 Turkish EFL learners regarding L2 oral presentations, exploring connections between language ability, speech anxiety, and motivation. Results showed that oral presentations positively impacted language skills, reducing speaking anxiety (N = 29, t = 1.87, p = 0.07) and increasing motivation (N = 29, t = −0.99, p = 0.44), as evidenced by pre-and post-survey results and qualitative data analysis. Jiang and Papi (2022) investigated the relationship between chronic regulatory focus, L2 self-guides, L2 anxiety and motivated behavior among 161 EFL learners. Results showed that ought-to L2 self/own positively predicted L2 anxiety (β = 0.17, p < 0.05) while ideal L2 self/own negatively predicted L2 anxiety (β = −0.26, p < 0.05). It seems that anxiety and motivation developed in opposite directions, but the authors did not further draw correlations between the two variables. Thus, this study will advance this topic.

2.3 L2 motivation

Motivation stands as a foundational variable within developmental and educational psychology, as highlighted by scholars, such as Dweck (2013) and Gardner (1985, 2010), and is recognized as pivotal for achieving successful outcomes in second language learning (Dörnyei, 1998; Dörnyei and Ushioda, 2013). Dörnyei and Ushioda (2011) proposed the L2MSS, which provided a comprehensive perspective on L2 motivation, defining it as the direction and intensity of a language learner’s learning behaviors. It encompasses decisions related to learning, levels of perseverance, and invested efforts. Within this framework, L2 motivation serves as the driving force behind learners’ determination, duration of persistence, and dedication to their set goals.

Dörnyei’s (2005) conceptualization of L2 motivation represents a transformative step. It draws upon established self-psychology theories such as Higgins et al. (1985) and Higgins (1987) and relevant empirical studies such as Dörnyei et al. (2006) to reformulate the motivational thinking. L2MSS comprises three primary components: ideal L2 self, ought-to L2 self, and L2 learning experience. The ideal L2 self pertains to the aspirational transformation from one’s present self to a desired self. The ought-to L2 self involves the belief that certain expectations should be met, or potential negative outcomes avoided. L2 learning experience encapsulates the immediate learning environment, including interactions with peers, instructors, curriculum difficulty, and learning achievements (Ushioda and Dörnyei, 2009). In the realm of oral presentations, ideal L2 self pertains to a learner’s vision of themselves confidently delivering speeches, articulating thoughts clearly, engaging the audience, and mastering the linguistic and communicative aspects of the presentation. Ought-to L2 self embodies the sense of duty, moral responsibility, or fear of negative perceptions that compel one to excel in oral presentations. The L2 oral presentation learning experience encompasses the journey of learning, preparation, and presentation, fostering the development of both ideal and ought-to L2 selves.

The integration of Dörnyei’s L2MSS and its components into the context of oral presentations lays a solid foundation for understanding the motivational dynamics within this specific domain. García-Pinar (2019) explored whether engineering undergraduates’ L2 motivational selves to learn English and engage in oral presentations could be enhanced through a multimodal pedagogy utilizing TED Talks. Employing a mixed-methods, one-group pretest-posttest design, the research investigated the impact of the pedagogical intervention over a semester. Results indicated a decrease in L2 anxiety (N = 150, t = 13.686, p < 0.001) and an increase in ideal L2 self (N = 150, t = −13.001, p < 0.001) after the intervention, highlighting the potential benefits of holding oral presentations events in language classrooms. This study also mentioned that L2 anxiety and ideal L2 self were negatively correlated (r = −0.471, p < 0.001). Further to this cross-sectional study, the present longitudinal study will provide additional perspectives to these findings.

Wu (2022) explored the impact of various factors on EFL learners’ oral presentation performance, including L2 motivation and anxiety levels. The study involved 316 second-year Chinese university students participating in a listening and speaking course. Results indicate that there was a negative correlation between ideal L2 self and anxiety (r = −0.255, p < 0.001) and a negative correlation between ought-to L2 self and anxiety (r = −0.402, p < 0.001). Qualitative insights from participants’ self-reflections supported the quantitative findings. However, research has raised concerns about the psychometric validity of measures used in the L2MSS. Teimouri (2017) have spurred calls for a revision of the model to address theoretical and methodological shortcomings, which led to more accurate interpretations of how motivation influences language learning. Further, Al-Hoorie et al. (2023) stated that discriminant validity issues arise when measures intended to assess different constructs are too highly correlated, suggesting they might not be distinctly capturing the intended separate constructs as effectively as presumed.

While previous scholarly works have explored the relationship between L2 motivation and anxiety, a notable research gap exists concerning investigations into EFL oral presentations over time (Bećirović, 2020). This study endeavors to address this void by undertaking an investigation in the realm of EFL oral presentation engagements. Despite the acknowledgment of anxiety and L2 motivation as influential factors in language learning, there remains a distinct gap in the existing literature concerning their specific impact on EFL oral presentations. Therefore, a comprehensive investigation into the intricate relationships between L2 motivation and anxiety is warranted. This study aims to bridge this gap by examining how these factors interact and shape learners’ performance in EFL oral presentations over time, providing valuable insights for pedagogical refinement and more effective language learning strategies.

3 Methods

This study adopts a mixed methods approach, combining quantitative questionnaire surveys and qualitative analyses to investigate the relationship between L2 motivation and anxiety in EFL learners’ oral presentations. This methodology was chosen to capture the dynamics of learners’ experiences, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of how motivation and anxiety levels change over time and why these changes occur.

3.1 Research questions

This study was driven by the following research questions:

1. How did the levels of L2 motivation and anxiety among Chinese EFL learners change over the four successive oral presentations?

2. How did variations in initial levels of ideal L2 self and ought-to L2 self relate to and/or predict the growth rates of these variables throughout multiple oral presentations?

3. What can be teachers’ roles in enhancing EFL learners’ L2 motivation and mitigating anxiety levels in oral presentations?.

3.2 Participants and procedure

The present research investigated the growth trajectories of Chinese EFL learners’ L2 motivation and anxiety levels during multiple oral presentations. The study involved a longitudinal examination of 171 second-year undergraduate medical students (101 males and 70 females) enrolled in an EAP course at a university in Eastern China. The mean age of the participants at the time of the first questionnaire was 19.47 years, with an age range from 17 to 21 years old. The students spoke Chinese as the first language. Over the course of the 2021 Fall Semester and 2022 Spring Semester, the participants delivered four Pecha Kucha oral presentations and completed questionnaire surveys on their anxiety levels and L2 motivation after each delivery. A Pecha Kucha presentation, known for its concise format of 20 slides timed at 20 s each, totals 6 min and 40 s (Levin and Peterson, 2013; Fahmi and Widia, 2021; Susanto, 2022; Wu, 2022). This study also employed the Pecha Kucha style for oral presentations. However, considering the challenges for non-English major students, an adjusted version is adopted, featuring six slides that transition every 20 s, resulting in a duration of 2 min for each participant.

In the 2021 Fall Semester, the students took four training sessions and an assessment session. In the first session, the students chose a topic from a list. Then, the teacher announced the procedure, the requirements, and the assessment method. In the second and third sessions, the students learned to write a script for the presentation, namely a persuasive essay, including its features of organization, content, and style. The students were encouraged to submit a draft to the researcher. For unsatisfactory submissions, such as blurred thesis statements, too many grammatical errors, and unanticipated length (too long or too short), the students were asked to revise. Those two sessions scaffolded their writing ability and guaranteed that their script adhered to the chosen topic. In the fourth session, necessary computer techniques were introduced. The participants were encouraged to rehearse by themselves or with peers. The researcher walked around the classroom to answer their questions. The fifth session was the assessment session. In the first semester, the student participants delivered their prepared speech in front of the whole class twice. In the subsequent semester, the researcher provided a review session with the participants by repeating the requirements, rating methods, and a review of last Pecha Kucha events, followed by two more oral presentation deliveries. Two raters assessed the four deliveries.

3.3 Measures

The questionnaire items measuring the participants’ anxiety levels were acquired from the 34-item Personal Report of Public Speaking Apprehension (PRPSA) developed by McCroskey (1970) and an adapted version of the L2MSS questionnaire developed and validated by Wu (2022) that is focused on students’ ideal L2 self and ought-to L2 self perceptions specifically in oral presentations. The researcher had intended to adapt the L2 learning experience construct from the L2MSS framework, but the piloting participants and an expertise panel considered that the L2 learning experience construct from the L2MSS framework lacks content validity for research in oral presentation. Therefore, the researcher decided to turn this part into qualitative research. Please refer to the Appendix for the questionnaire items of this study.

Following the construction of the item pool, the researcher proceeded to develop the rating scales. In this study, the 7-point Likert scale was chosen, diverging from the 6-point scale used by Taguchi et al. (2009), as well as the 5-point scale employed by McCroskey (1970). Research has indicated that the more points a Likert scale has, the higher accuracy a questionnaire will have regarding its factor loadings, squared multiple correlations, and reliability coefficients (Yusoff and Mohd Janor, 2014). Balancing practicality with visual effectiveness in an online survey setting, this study opted for the consistent use of the 7-point Likert scale across all its measures.

The questionnaire also contains five open-ended questions regarding L2 oral presentation learning experience, which served as the qualitative component of this mixed-methods study. This approach complements the quantitative data, offering a comprehensive view of the participants by integrating diverse methodologies to enrich the research design and deepen the understanding of the findings. The set of five questions is as follows:

1. What difficulties have you met in the Pecha Kucha preparation and delivery phases?

2. How did you overcome those difficulties you have just mentioned?

3. What aspect do you like most in the Pecha Kucha presentation?

4. What aspect do you dislike most in the Pecha Kucha presentation?

5. Are you satisfied with your performance? If so, why? If not, how do you think you can improve?

Then, two recognized experts in educational psychology and psychometrics or L2 speaking, were invited to evaluate the content validity of the questionnaire. Their feedback included theoretical underpinnings, item phrasing, readability, translation accuracy, and construct coherence. Subsequently, slight revisions were applied to two items for improved clarity. After this, the researcher engaged ten Chinese undergraduate students to assess item lucidity, relevance, and the questionnaire’s overall conciseness. Considering their input, minor adjustments were incorporated. The refined questionnaire underwent piloting with 30 undergraduate students in two separate administrations, spaced a week apart. Notably, the test–retest reliability coefficient yielded a value of 0.88, attesting to a high correlation between the outcomes of the two administrations (Brown, 2001).

3.4 Data analysis

Initially, IBM SPSS 29.0 was adopted to conduct exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients were computed to examine the association between L2 motivation and anxiety and to assess the stability of the three variables. Then, utilizing SPSS Amos 29, a comprehensive exploration was conducted regarding the mean growth trajectory of the participants’ L2 motivation and anxiety levels. This investigation involved the examination of three independent univariate latent growth curve models, each aimed at discerning the initial level and developmental trends inherent in L2 motivation and anxiety while also considering potential individual disparities. These models encompassed two latent factors: an intercept factor, capturing the average initial level, and a slope factor, delineating the developmental progression and alterations over time. Notably, correlations were analyzed between the initial level (intercept) and the growth (slope) factors. For the repeated measurements, the loading on the intercept factor was held constant at a value of 1 across the four time points. Given the specific focus on the enduring influence of L2 motivation on anxiety levels, fixed loadings of 0, 1, 2, and 3 were assigned to the slope according to the time intervals of assessments for L2 motivation and anxiety from T1 to T4. Furthermore, the mean and variance of the intercept and slope factors described the variability of the initial level and rates of changes separately.

Subsequently, a multivariate latent growth curve model was constructed, employing the aforementioned frameworks to investigate the intricate connections between evolving changes in the participants’ L2 motivation and anxiety levels. In this composite model, the independent latent factors (intercept and slope) representing the participants’ L2 motivation were arranged to predict the dependent latent factors (intercept and slope) representing the participants’ anxiety levels. Correlations coefficients between the intercept and slope of the independent latent factors were calculated. Throughout the analysis, the model fit was assessed utilizing the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), non-normed fit index (TLI), and incremental fit index (IFI), adhering to the methodology outlined by Hu and Bentler (1999). Model estimation was undertaken using the maximum likelihood estimation. As the questionnaire was loaded online, and all questions were set mandatory to answer before submission, there was no missing data.

The qualitative data analysis was conducted following the six-stage thematic analysis framework outlined by Braun and Clarke (2021), including familiarizing with the qualitative data, generating primary codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining themes, and writing-up. According to those instructions, the responses were iteratively coded according to the two key themes, namely the L2 motivation and L2 anxiety frameworks. This process ensured that the themes accurately encapsulated the learners’ experiences in relation to the theoretical constructs. NVivo 1.7 was adopted to conduct iterative, open, axial, and selective strategies (Boeije, 2009).

3.5 Ethical consideration

This study was guided by the British Educational Research Association (BERA) (2018). All the student and teacher participants voluntarily took part in the study and remain sensitive and open to withdraw their consent for any reason and at any time. The participants have the right to withdraw their data at any time without giving a reason.

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive data and correlation

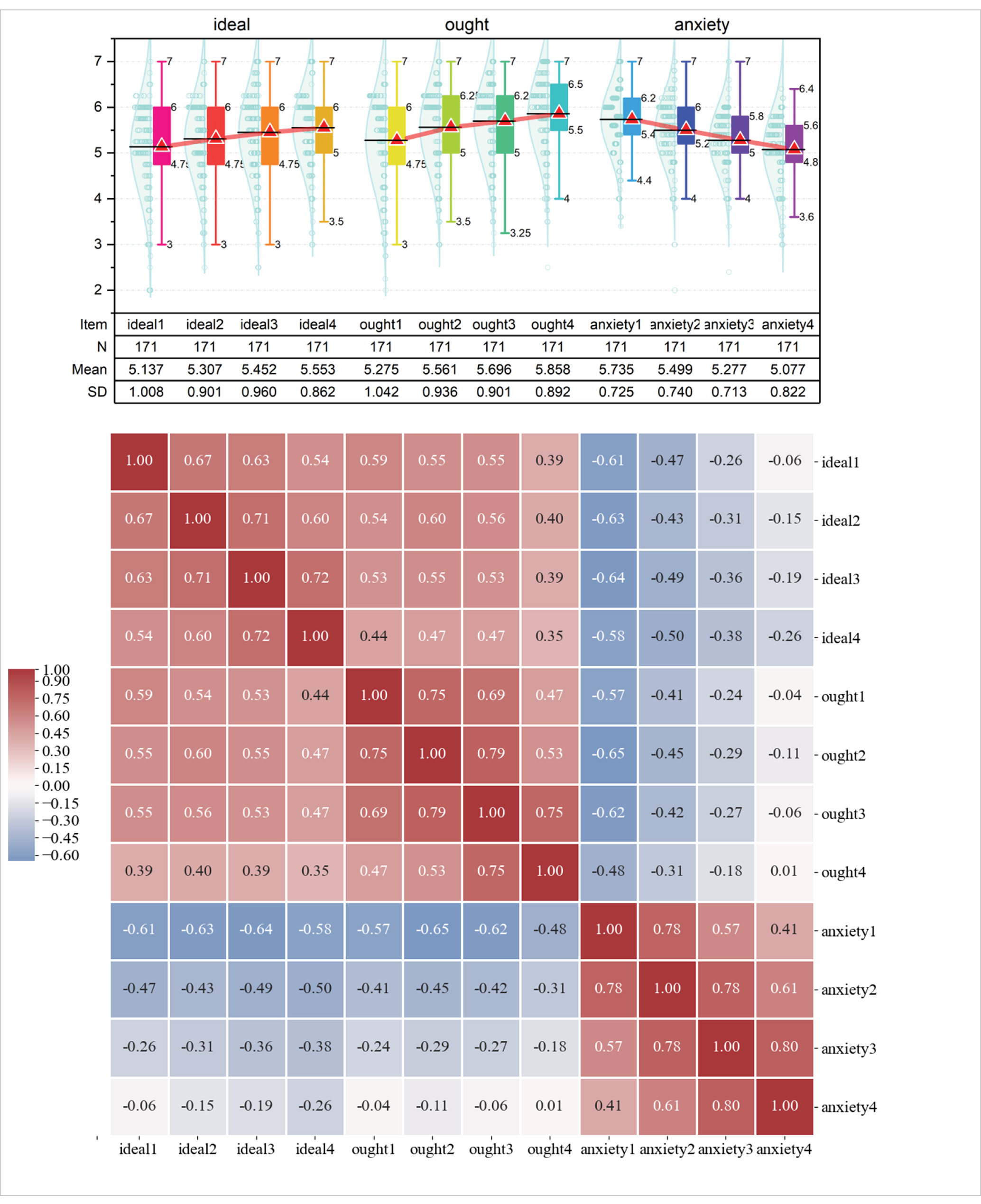

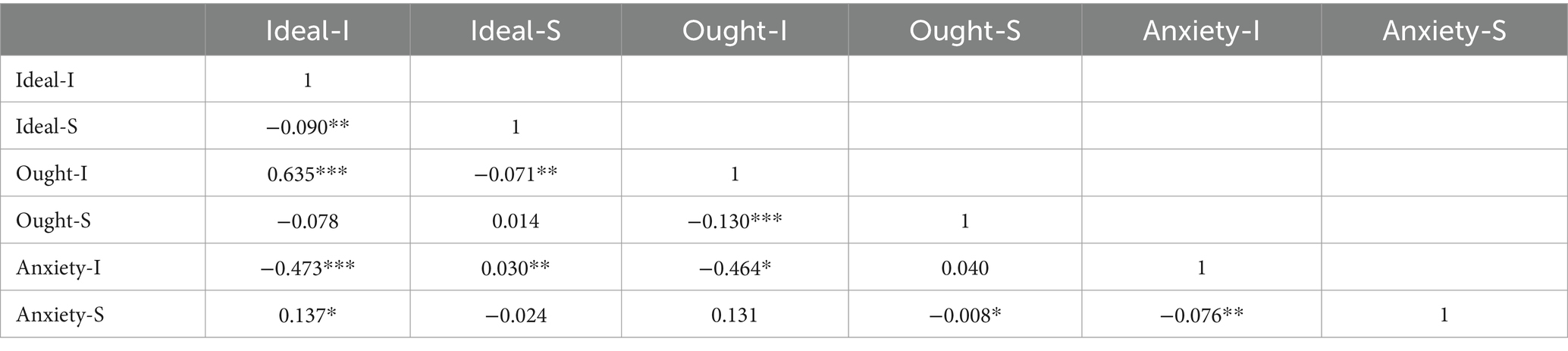

Table 1 presents the mean, standard deviation (SD), and correlation coefficients of the primary variables. The precise prediction of growth curves depends on the condition that there are stronger relations between repeated indicators at consecutive measurement points than the correlations observed on non-consecutive occasions (Lorenz et al., 2004). It can be seen from Table 1 that the correlation matrix specified that correlation coefficients between two consecutive occasions (t and t + 1) for each factor were higher than correlations between non-consecutive occasions. These results suggest a high level of stability within the three variables. Furthermore, there existed a positive correlation between ideal L2 self and ought-to L2 self. On the contrary, there existed negative correlations between ideal L2 self and anxiety and between ought-to L2 self and anxiety. Table 1 also shows the developmental trajectory of L2 motivation and anxiety levels, which provides a visual and detailed representation of the growth trajectories of the three variables.

4.2 EFA

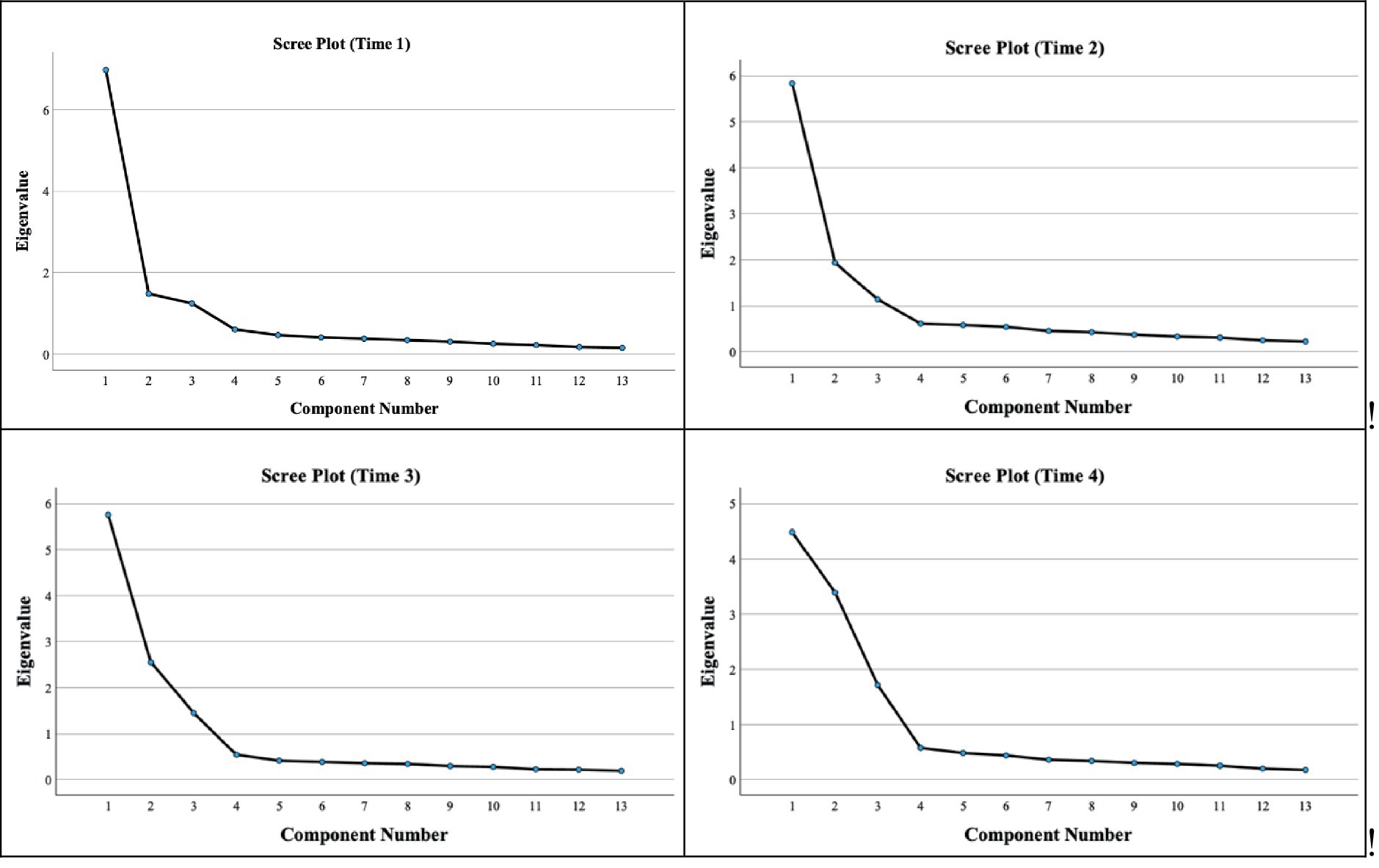

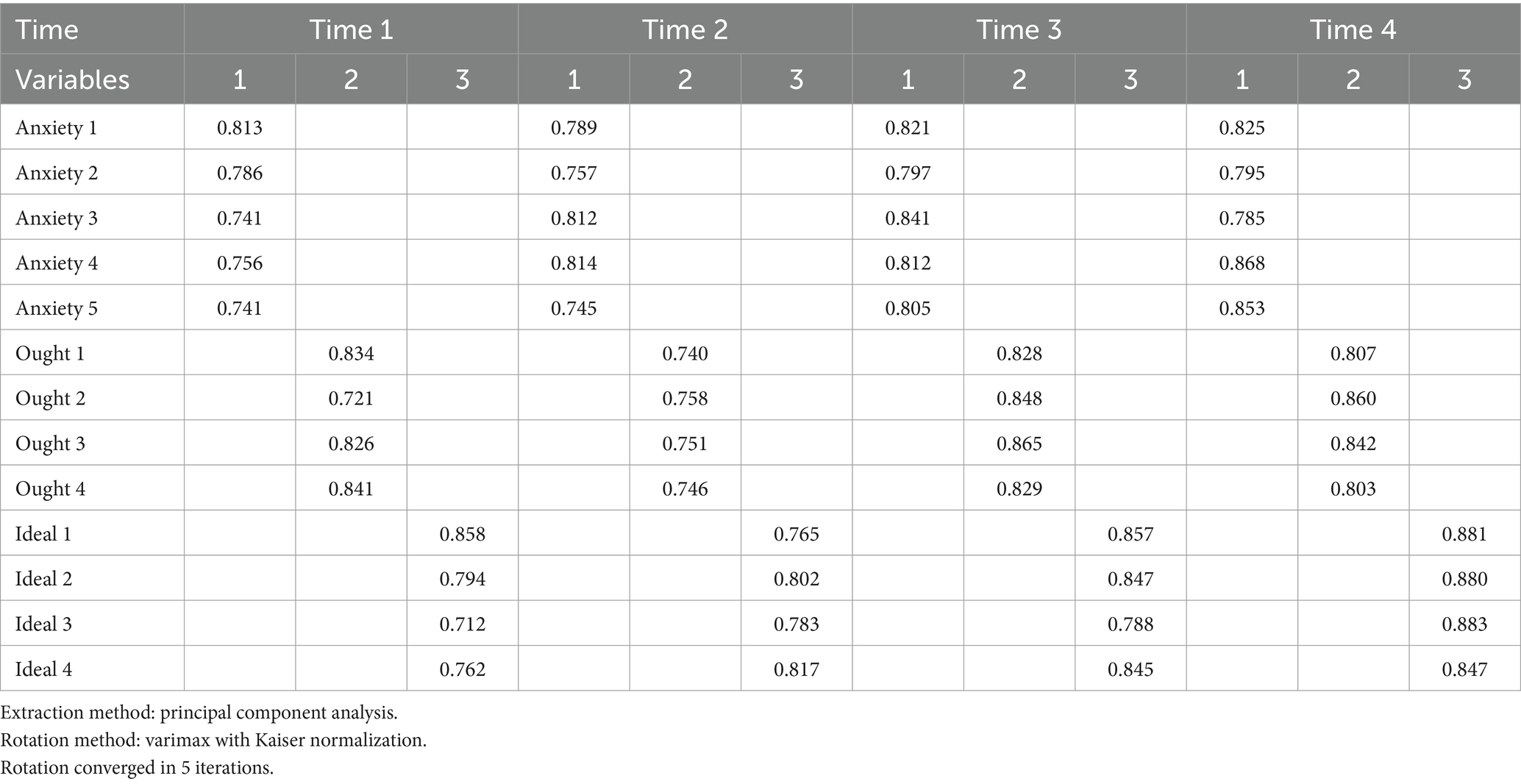

The construct validity of the three variables was investigated by EFA. The rotation method was the Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. Principal component analysis extracted three factors with eigenvalues larger than 1 in the four time points. The Scree test result indicated that the three-factor solution was a suitable grouping method for the items in the four time points (see Figure 1).

Then, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) was performed to examine how the factors explain each other between the variables. The KMO value of the proposed model at the four time points were 0.906, 0.886, 0.887, and 0.844. If the KMO value is larger than 0.80, it can be considered ideal (Everitt and Skrondal, 2010). The Bartlett’s test of Sphericity was adopted to test the null hypothesis that the correlation matrix is an identity matrix. An identity correlation matrix suggests the variables in a model are not unrelated and not ideal for factor analysis. The Bartlett’s test of Sphericity of the proposed model in the four time points were also significant (Time 1: χ2(78) = 1547.918, p < 0.001; Time 2: χ2(78) = 1139.374, p < 0.001; Time 3: χ2(78) = 1429.699, p < 0.001; Time 4: χ2(78) = 1338.618, p < 0.001). The significant test results demonstrate that the correlation matrix is not an identity matrix. Therefore, the null hypothesis was rejected (Dörnyei and Taguchi, 2009), and the three variables were distinct variables. Overall, these test results showed that the proposed model was acceptable. The factor loadings from the final EFA results are illustrated in Table 2.

4.3 Growth of L2 motivation and anxiety

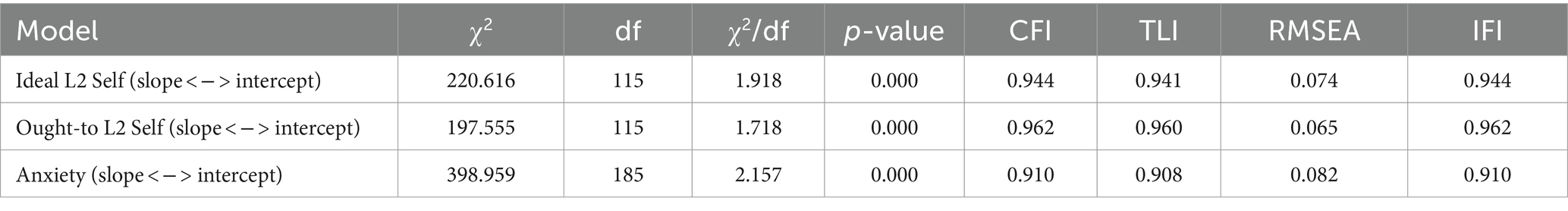

The SEM analysis of the three distinct models in confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) obtained satisfactory model fits listed in Table 3. Several key fit indices are utilized to ensure the adequacy and reliability of the model. The chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (χ2/df) should ideally be 3 or less (Kline, 2005). The Comparative Fit Index (CFI), as per Bentler (1995), should be at least 0.90, with higher values indicating a closer fit to the ideal model. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) should ideally be 0.10 or lower (Browne and Cudeck, 1993). The Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI), also known as the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), is also used to evaluate the fit of a model. Usually, a TLI value above 0.90 is considered to indicate good model fit Bentler (1995). Lastly, the Incremental Fit Index (IFI) is another fit index assessing the adequacy of a model fit to the observed data. A common threshold for a good model fit is 0.90 or above (Browne and Cudeck, 1993).

The direction and extent of growth of L2 motivation and anxiety that the participants experienced during the four oral presentations is listed in Table 4. The means and slopes of the three variables were statistically significant. The strong correlations at the 0.001 level indicate robust connections between these variables. The results indicated that ideal L2 self and ought-to L2 self increased over time, and anxiety levels decreased over time.

4.4 Heterogeneity of L2 motivation and anxiety

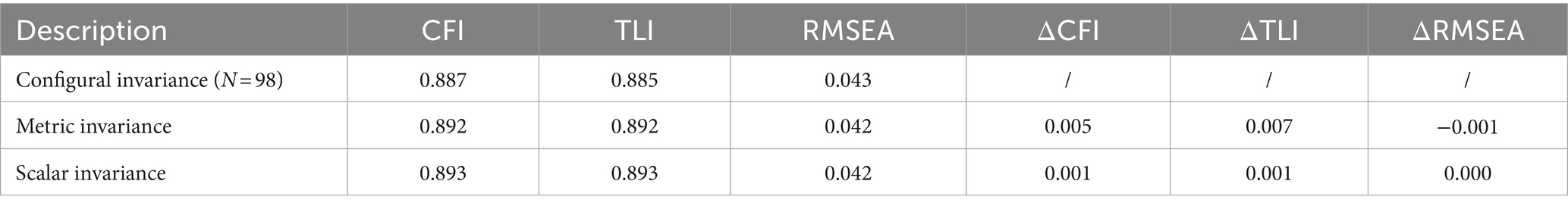

Heterogeneity describes the diversity of data (Guyatt et al., 2011). The significant variances in the intercepts of the variables in Table 4 shows the heterogeneity of data in the initial session. Furthermore, an examination in the slope variances shows the heterogeneity of data in the four oral presentation events. Statistically significant variances in three variables highlight the existence of variations between individuals in the developmental trajectories of L2 motivation and anxiety levels. Put differently, certain participants demonstrated a higher rate of change in L2 motivation and anxiety, while others exhibited comparatively lower rates of change throughout the four oral presentations. The measurement invariance results in Table 5 indicated that metric invariance and scalar invariance was successfully established (ΔCFI, ΔTLI, and ΔRMSEA <0.01) (Cheung and Rensvold, 2002; Brown, 2015; Klassen et al., 2023), which suggests that the constructs maintained consistent intercepts and factor loadings over different time periods. However, even though the longitudinal analysis in Table 3 showed satisfactory model fit indices, the measurement invariance analysis in Table 5 exhibited poorer fit, as indicated by CFI and TLI values. The reason lies in that the impact of sample size is significant; smaller sample sizes within each group can affect the stability of the fit indices, generally leading to lower values. In other words, parameter estimation in group analysis might not be as robust as that in the overall sample, particularly when dealing with smaller group sizes (Meade et al., 2008).

4.5 Association of the change between L2 motivation and anxiety

The covariance matrix in Table 6 illustrates the interplay between the latent factors representing the participants’ ideal L2 self, ought-to L2 self, and levels of anxiety. Notably, the covariance between the ideal L2 self intercept factor (Ideal-I) and the ought-to L2 self intercept factor (Ought-I) was statistically significant (σ = 0.635, p < 0.01). This suggests a positive relationship between participants’ ideals and perceived obligations related to their L2 oral presentation selves. Furthermore, a negative covariance is observed between the ideal L2 self intercept factor (Ideal-I) and the anxiety intercept factor (Anxiety-I) (σ = −0.473, p < 0.01), indicating that individuals with higher ideals about their L2 oral presentation abilities tend to experience lower levels of anxiety.

Turning attention to the slope factors, notable relationships emerged between the participants’ evolving L2 motivation and anxiety levels. The covariance between the ideal L2 self slope factor (Ideal-S) and the anxiety slope factor (Anxiety-S) is statistically significant (σ = −0.024, p < 0.05). This suggests that individuals who experienced a more positive shift in their ideal L2 self over time tended to exhibit a reduction in anxiety related to oral presentation.

Additionally, the covariance between the ought-to L2 self slope factor (Ought-S) and the anxiety slope factor (Anxiety-S) was slightly negative, although not statistically significant (r = −0.008, p > 0.05). This indicates a tendency for individuals experiencing a change in their perceived obligations to their L2 selves to also experience a slight decrease in anxiety, though the relationship is not strong enough to reach significance.

4.6 The predictive power of L2 motivation on anxiety levels

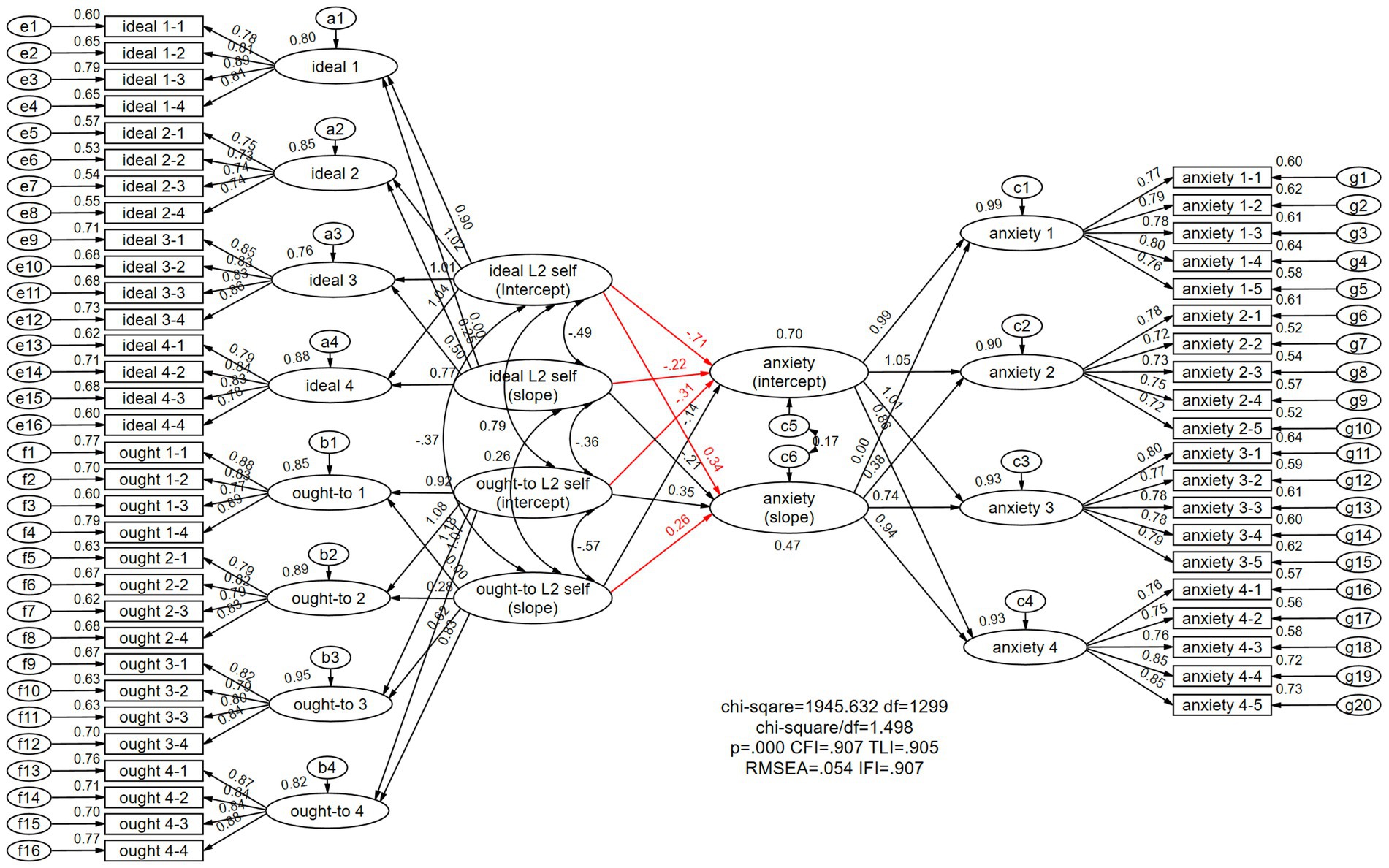

Figure 2 is the parallel process model describing the association between L2 motivation and anxiety levels. This model obtained satisfactory model fits. Red lines indicate the causal relationships are statistically significant. Results showed that:

1. The ideal L2 self intercept factor significantly predicted the anxiety intercept factor (β = −0.712, p < 0.001). This finding suggests that individuals with a higher initial ideal L2 self tended to experience lower levels of anxiety related to oral presentation delivery journey. As the ideal L2 self intercept factor decreases, indicating a less positive self-concept, the anxiety intercept factor tended to increase.

2. The ideal L2 self intercept factor significantly predicted the anxiety slope factor (β = 0.342, p = 0.048). This result implies that participants with a more positive initial ideal L2 self tended to exhibit a slightly steeper increase in anxiety over time. It suggests that as individuals’ ideal self-concept became more favorable, they might have become more sensitive to potential threats or discrepancies in their oral presentation delivery progress.

3. The ideal L2 self slope factor significantly predicted the anxiety intercept factor (β = −0.223, p = 0.008). This significant relationship indicates that individuals who experienced a more positive shift in their ideal L2 self over time tended to have lower initial levels of anxiety. As their ideal self-concept improved, they were likely to start their language learning journey with a lower level of anxiety.

4. There was no causal relationship between the ideal L2 self slope factor and the anxiety slope factor (β = −0.211, p = 0.113). This suggests that changes in the trajectory of participants’ ideal L2 self over time were not significantly associated with changes in their anxiety levels over time. In other words, shifts in their ideal self-concept did not predict changes in anxiety trends.

5. The ought-to L2 self intercept factor significantly predicted the anxiety intercept factor (β = −0.309, p = 0.012). This outcome indicates that participants who initially perceived a higher sense of obligation (ought-to L2 self) tended to experience lower initial levels of anxiety in the context of foreign language learning.

6. There was no causal relationship between the ought-to L2 self intercept and the anxiety slope factor (β = 0.349, p = 0.053), implying that higher initial levels of ought-to L2 self perceptions were associated with a slightly steeper increase in anxiety levels over time. However, the p-value of 0.053 is slightly above the conventional threshold of 0.05, which means that the observed relationship is not statistically significant at a standard level of significance. This suggests that the relationship between the ought-to L2 self intercept and anxiety slope may not be strong enough to draw confident conclusions, and there is a possibility that the result could be due to chance.

7. The ought-to L2 self slope factor significantly predicted the anxiety intercept factor (β = −0.145, p = 0.078), which means that there was a relationship between the rate of change in participants’ ought-to L2 self perceptions over time and their initial levels of anxiety. However, the p-value of 0.078 is slightly above the conventional threshold of 0.05, which means that the observed relationship may not be statistically significant at a standard level of significance. This suggests that while there is an indication of a relationship, the result could still potentially be due to chance, and further investigation might be needed to confirm the significance of this relationship.

8. The ought-to L2 self slope factor significantly predicted the anxiety slope factor (β = 0.259, p = 0.029). There is a statistically significant relationship between the changes in the participants’ ought-to L2 self perceptions over time and changes in their anxiety levels over time in oral presentations. In other words, as participants’ sense of obligation (ought-to L2 self) increased more rapidly or steeply over the four oral presentation delivery, their anxiety levels exhibited a corresponding change.

Figure 2. Standardized estimates of the parallel process model describing the association of L2 motivation and anxiety.

4.7 Qualitative results

The qualitative analysis of this study delves into the learning experience of the Chinese EFL learners. Through thematic analysis of the five open-ended questions, two primary themes emerged, namely L2 motivation and anxiety levels, offering insights into the complexities of language learning from a psychological perspective. This section unpacks these two themes to better understand the factors influencing learners’ experiences in EFL oral presentations.

4.7.1 Evolution of L2 motivation in EFL oral presentations

This theme captures two codes, namely ideal L2 self and ought-to L2 self. The former refers to learners’ aspirational image of themselves as successful English speakers in delivering oral presentations. The latter relates to the attributes that learners believe they should possess to meet external expectations and avoid negative outcomes. The participants’ responses reveal a shift toward a more positive self-perception. Sample 9 below is an example of ideal L2 self, while Sample 142 is an example of ought-to L2 self (see Section 4.7.3).

In my first Pecha Kucha presentation, I was quite nervous about my performance. However, I received positive constructive feedback from the lecturer. I realized that I could communicate my ideas effectively, even not perfectly. By the second presentation, my confidence began to grow; I started to envision myself as a more competent speaker. I could engage my audience. My mind changed a little bit in the third and fourth presentations. Not only did I feel more comfortable speaking in front of others, but I also began to enjoy the process.

Sample 9 underscores the importance of ideal L2 self, demonstrating how positive reinforcement and successful experiences contribute to a stronger motivation for language learning. The narratives point to a gradual identification with being capable language users, suggesting that enhancing self-perception is crucial for sustaining language learning efforts.

4.7.2 Dynamics of anxiety and coping strategies

The second theme addresses how the participants experienced and managed anxiety associated with oral presentations. It delineates the high anxiety levels posed by initial challenges, such as the timing requirements of Pecha Kucha presentations, and the subsequent adaptation through various coping mechanisms, including thorough careful preparation and the pursuit of professional feedback. Sample 112 described their change of anxiety levels as:

Before my first Pecha Kucha presentation, the format and timing of Pecha Kucha made me very nervous and anxious. My performance was not good the first time, but I realized I had issues with my pronunciation. I asked my teacher to help me with pronunciation corrections, which was very beneficial. At the same time, I learned to control the duration of each PowerPoint slide. These practices greatly improved my performance and significantly reduced my anxiety. (Sample 112)

Notably, Sample 112 believed that English pronunciation was the main reason for their oral presentation anxiety. However, they lowered the anxiety levels by seeking help from the lecturer and coped with Pecha Kucha’s timing requirements through repeated rehearsals. This theme illustrates the fluid nature of anxiety, highlighting a general trend of decreasing anxiety as learners accumulate more presentation experience.

4.7.3 The interaction between L2 motivation and anxiety in oral presentations

The interplay between the evolution of self-perception and the dynamics of anxiety underscores a reciprocal relationship where changes in one domain may predict the other. For example, Sample 142 linked their sense of duty to perform well in presentations that was triggered by the teacher-researcher and peers to an initial surge in anxiety, which then diminished as they gained experience. This narrative pattern resonates with the quantitative findings:

My teacher repeatedly emphasized on the importance of English oral presentation abilities in our future career development as a doctor (even though I cannot feel it right now), which makes me stressed and feel obliged to put more energy in it. My roommate is very good at giving Pecha Kucha presentations, so I sought advice from him. Our joint practice alleviated my anxiety about giving presentations, and I felt that my performance in the last event was better than the first three. (Sample 142)

Some interesting phenomena can be observed from those responses. First, the feeling of anxiety is a dynamic process; a student’s level of anxiety might spike due to a single comment from a teacher, or it could decrease with the encouragement and assistance from classmates. Second, a common way for students to reduce their anxiety about giving presentations was repeated practice, which is diversified in forms, such as seeking advice from teachers, learning from skilled peers, and watching tutorial videos online. Third, as learners’ self-perceptions evolve toward a more positive self-view, bolstered by successful experiences and recognition of their language capabilities, there may be a corresponding decline in anxiety levels.

5 Discussion

The findings of this study align with and extend the theoretical frameworks of Dörnyei’s (2005) L2MSS and the measures of anxiety in educational psychometrics. L2 motivation and anxiety have been recognized as crucial factors in language learning, particularly within the context of second language acquisition (Dörnyei, 1998; Dörnyei and Ushioda, 2013). As oral presentations constitute a fundamental aspect of language learning, especially in EFL contexts, delving into the dynamics of L2 motivation and anxiety during oral presentation events offers insights for instructional refinement. L2 motivation serves as a key determinant of learners’ dedication, involvement, and tenacity in language acquisition (Dornyei and Csizér, 2002; Csizér and Kormos, 2009; Taguchi et al., 2009; Ushioda and Dörnyei, 2009; Papi, 2010), while research into oral presentation anxiety may unveil potential stressors and obstacles that learners encounter (Woodrow, 2006; Blöte et al., 2009; Hammad and Ghali, 2015; Shi et al., 2015; Coskun, 2017; Leeming, 2017; Wu, 2022).

5.1 The development trajectory and characteristics of L2 motivation and anxiety

In line with Dörnyei’s framework, the observed increase in ideal L2 self and ought-to L2 self over time suggests learners’ evolving self-concepts and motivations. The increase over time could be due to the learners’ improving confidence in their language abilities and growing awareness of the importance of effective presentations for their academic and professional goals. As the participants engaged in successive oral presentations, their self-perceptions and motivations might align more with their desired future selves and obligations. The questionnaire items related to ideal L2 self and ought-to L2 self resonated with the Chinese cultural emphasis on academic achievement and social expectations (Wu, 2019, 2022; Wu et al., 2022). Sample 112’s response also resonates with García-Pinar’s (2019) findings, where multimodal pedagogies positively impacted learners’ ideal L2 self and decreased their L2 anxiety. This study extends these results by demonstrating how these shifts influence EFL learners’ oral presentation experiences over time.

Furthermore, the findings of this research indicated a noteworthy trend: as EFL learners gained experience in delivering oral presentations, their anxiety levels exhibited a decline. This study aligns with previous research on Chinese EFL learners, which suggests that anxiety can be a significant barrier to effective language learning (Cheng and Dörnyei, 2007). Chinese learners often experience high levels of language anxiety due to the pressure of performing well academically and the fear of being humiliated in front of peers. However, Sample 142’s response implies that repeated exposure to oral presentation scenarios may help reduce EFL learners’ sensitivity to anxiety and increase their L2 motivation during such activities. In the qualitative results, many participants reported that they were not as anxious as they had been before. The decreasing anxiety levels suggest that the participants became more comfortable and experienced with oral presentations as they progressed through the four instances. Familiarity with the presentation format, coupled with improved language skills and confidence, could contribute to the gradual reduction in anxiety over time. The observed decline in anxiety levels throughout the four oral presentations is consistent with previous research (Ritonga et al., 2020; Gurbuz and Cabaroglu, 2021; Susanto, 2022) and underscores the reducible nature of anxiety during EFL learners’ language learning journey.

In summary, these results collectively indicate a complex interplay between learners’ L2 motivation and anxiety levels during oral presentations. The upward shifts in self-concepts and the downward trend in anxiety imply positive development and adaptation over the course of the presentations. These findings suggest that learners’ perceptions and emotions are dynamic and subject to change based on their experiences and self-perceptions.

5.2 Can L2 motivation predict anxiety? If so, how?

The answer is possibly a “yes” just like many teachers would answer this question intuitively. However, since the fluctuation of psychological status is a dynamic process, the predictive power of L2 motivation over anxiety operates in a very delicate manner.

First, Ideal L2 self intercept predicts anxiety intercept and anxiety slope. Individuals with a higher initial ideal L2 self may possess a stronger belief in their language proficiency, leading to increased self-assuredness in facing oral presentations. This confidence can act as a buffer against anxiety, allowing them to approach presentations with a more positive mindset.

Second, Ought-to L2 self intercept predicts anxiety intercept. A higher sense of obligation to excel in oral presentations can create a heightened focus on preparation and performance. Individuals with a stronger initial sense of duty might perceive presentations as crucial to their learning goals, thereby experiencing lower initial anxiety levels.

Third, Ought-to L2 self slope predicts anxiety slope. As individuals’ sense of obligation intensifies over time, they might exhibit heightened preparedness and proactive engagement in oral presentations. This increased commitment could lead to a decrease in initial anxiety levels and a more controlled and gradual increase in anxiety levels as learners become more accustomed to the demands of presentations.

Those findings highlight the intricate relationships between L2 selves and anxiety in the context of EFL oral presentations. The upward trajectory of self-concepts and the downward trend in anxiety suggest that these factors are not static; instead, they dynamically evolve based on learners’ experiences and self-perceptions. This resonates with previous conclusions that L2 motivation is negatively correlated with anxiety levels (Mak, 2019; Gurbuz and Cabaroglu, 2021; Susanto, 2022). Additionally, this study contributes further empirical evidence, such as the predictive powers of L2 motivation on anxiety levels in the parallel process model, to refine the conclusions drawn from previous research. In fact, the decreasing anxiety levels observed among Chinese learners may suggest that familiarity with the Pecha Kucha presentation format, coupled with improved confidence, contributed to the gradual reduction in anxiety over time. This is in line with cultural factors that may shape the Chinese learners’ attitude toward oral presentations (Ye, 2014; Zhang and Ardasheva, 2019). For instance, the questionnaire items related to anxiety captured the participants’ fear of forgetting prepared content and concerns about making mistakes. In the context of Chinese culture, where losing face and maintaining harmony are significant, such fears could be more pronounced, thus influencing their anxiety responses during oral presentations. However, this study provides convincing evidence that with the increase of L2 motivation during multiple oral presentation delivery, EFL leaners’ anxiety levels can be reduced. However, this study provides opposite findings regarding the causal relationship between ideal L2 self and anxiety in Jiang and Papi (2022), which may result from the cultural context, educational settings, and nature of tasks. This discrepancy highlights the complexity of language learner psychology across different cultural landscapes. It suggests that while motivational strategies are generally effective, the specifics of their implementation must be culturally sensitive to optimize learning outcomes. Additionally, the divergent results highlight the need for educators to tailor their approaches, particularly in diverse classroom settings where cultural backgrounds vary.

In summary, the results suggest that learners’ perceived ideal selves and obligations all have nuanced relationships with anxiety levels during oral presentations. These findings underscore the intricate interplay between cognitive and affective factors in shaping language learners’ experiences and provide valuable insights for designing interventions that target specific aspects of learners’ psychological experiences.

5.3 Teachers’ Roles in Enhancing EFL Learners’ L2 Motivation and Mitigating Anxiety Levels in Oral Presentations

The research findings revealed a reverse relationship between L2 motivation among EFL learners and their levels of anxiety. The observed decrease in anxiety as students engaged in more oral presentations indicates that repeated exposure to such activities may diminish EFL learners’ sensitivity to anxiety during oral presentations. This crucial insight has significant pedagogical implications for instructors tasked with enhancing EFL learners’ oral presentation skills.

First, language teachers can adopt an incremental approach to guiding learners’ oral presentations. By gradually increasing the number and complexity of oral presentations, learners can build their confidence and become more skillful in expressing themselves in a foreign language. If possible, language teachers can also provide regular opportunities for EFL learners to practice oral presentations, which helps them become more familiar with the process, reducing the fear of the unexpected, and improving their capability to manage anxiety in future presentations. However, in the qualitative results, many Chinese students, due to the intensive nature of oral presentations, perceived the pressure of having two sessions per semester as overwhelming. Many of them considered these rigorous speech requirements in EAP courses to be more focused on assessment rather than genuinely on beneficial learning experiences. However, driven by their commitment to their attendance in a prestigious university in China, they still strived to fulfill the assessment criteria. Those comments warn teachers that while having students give repeated oral presentations can reduce their anxiety and better self-concepts, too many oral presentation tasks have the potential to increase their academic load and instead negatively affect their learning motivation. When assigning oral presentation tasks, teachers may want to take students’ academic burdens into consideration. After all, EAP and ESP courses are just one of the non-major courses for these non-English major medical students, so teachers could consider lowering the difficulty of the oral presentation tasks or providing more scaffolding (Gibbons, 2002) during the task process. The scaffolding in this study included various supports mentioned in Section 3.2, such as explicitly teaching students how to write scripts for Pecha Kucha presentations, providing feedback on scripts, and teaching computer skills.

Second, teachers should create a supportive classroom atmosphere. Oral presentation in public is commonly regarded as the primary fear that language learners are likely to encounter (Smith and Sodano, 2011). Teachers should encourage a supportive and non-threatening classroom atmosphere (Zhang et al., 2020), where mistakes and failures are viewed as opportunities for learning and improving. Teachers should encourage learners to give mutual encouragement during presentations to create a safe space for them to practice.

Third, teachers should offer formative feedback and support throughout the learning process. Constructive and formative feedback can help learners identify their areas of weaknesses, address concerns, and build on their strengths, reducing their anxiety levels in oral presentations. In the qualitative results, the participants addressed that the quality of guidance during the speech preparation and after the oral presentation delivery is more crucial than the sheer quantity of oral presentation sessions. They placed a higher emphasis on instructor feedback, especially pertaining to pronunciation accuracy and rhythm of their speech. This finding is align with Wu (2022), who mentioned that the accuracy and fluency are among students’ top pursuits.

Fourth, language teachers should consider model effectiveness in oral presentations and provide learners with examples of successful oral presentations. Observing skilled speakers would inspire learners and provide them with a blueprint for their oral presentations. In the qualitative results, many participants reported that they were inspired by and followed their peers who got high grades in their oral presentations. They also reported that they benefited a lot from the TED talk video clips and other well-performed Pecha Kucha samples given by the teacher-researcher. The use of TED talk clips and Pecha Kucha samples in teaching aligns with social learning theory, which posits that people learn by observing others. This method allows students to see effective presentation techniques in action, enhancing their learning and motivation by modeling successful behaviors (Bandura, 1977).

Fifth, language teachers should encourage learners to engage in self-reflection after each presentation. This practice allows students to identify their progress, set realistic goals, and develop a growth mindset toward improving their oral presentation skills. Studies such as those by Dweck (2013) highlight the importance of growth mindsets in educational settings, demonstrating how they can enhance learners’ motivation and learning outcomes by encouraging resilience and a commitment to learning. Furthermore, goal-setting theories suggest that clear, achievable goals can significantly boost students’ engagement and performance Locke and Latham (2002).

The researcher hopes that those pedagogical suggestions would help language teachers create a dynamic and supportive learning environment that empowers EFL learners to develop their oral presentation skills with reduced anxiety and increased effectiveness. However, the quantity, complexity, and difficulty of oral presentation tasks should cater to students’ academic needs and burdens.

6 Limitations and suggestions for future research

While the study contributes valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. The focus on a specific group of Chinese EFL learners in a particular context restricts the generalizability of the findings. Further research could encompass a diverse range of learners across different contexts to validate the observed relationships. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data may introduce biases, warranting future investigations using mixed-methods approaches for a comprehensive understanding of learners’ experiences. Moreover, due to the longitudinal nature of this study, there were many confounding variables that could have caused unavoidable noises. For instance, students learned English for a year, and their English proficiency might have been improved in the process, which alleviated their feelings of anxiety. Additionally, the instructor might have inadvertently used positive encouraging words or negative urging or pushing phrases, leading to changes in the participants’ emotional perceptions. Furthermore, this study lacks a comparison with a control group. Given the extended duration and the real-world teaching environment, setting up a control group is relatively impractical.

While this research makes strides in exploring the growth patterns of anxiety among Chinese EFL learners during oral presentations, it also opens avenues for future research. Scholars can build upon these findings to investigate the impact that teachers may have on learner anxiety and motivation, investigating the role of the teacher could provide valuable insights in EFL oral presentations. This could include examining teaching styles, feedback mechanisms, and the interpersonal dynamics between teachers and students as potential areas of study.

Investigate additional factors that influence anxiety levels, explore potential individual differences in anxiety responses, and evaluate the long-term effects of anxiety reduction on language proficiency and overall communication competence. Such endeavors can enrich the understanding of language learning and inform evidence-based pedagogical practices in the realm of EFL oral presentation instruction.

To advance the topic, future research could investigate additional factors predicting anxiety levels during oral presentations, such as individual differences in genders, language proficiency, personality traits, or cultural backgrounds. Moreover, investigating the potential long-term effects of anxiety reduction on language development and overall communication competence would provide valuable insights. Ultimately, understanding the dynamics of anxiety in EFL oral presentation settings will equip language teachers with evidence-based teaching decisions to better support learners and foster their language learning journey.

7 Conclusion

This study explores the relationship between L2 motivation and anxiety in Chinese EFL learners’ oral presentations. The findings show that as learners became more motivated, their anxiety levels tended to decrease. This suggests that increased practice and confidence in speaking can positively affect students’ anxiety. The growth in learners’ ideal L2 self and ought-to L2 self over time indicates that their self-confidence and understanding of the importance of oral presentations in their academic and professional futures improved. This study supports the idea that L2 motivation and anxiety are closely linked, and that this relationship is influenced by learners’ experiences and cultural context. By focusing on strategies that boost motivation and reduce anxiety, educators can make oral presentations a more effective and less stressful part of language learning. This work aligns with previous research but adds new insights into how educational practices can evolve to better support EFL learners.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Central University Research Ethics Committee, University of Oxford. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

HW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The publication fees for this article were funded by the Kellogg College Research Support Grants, University of Oxford.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahmetović, E., Bećirović, S., and Dubravac, V. (2020). Motivation, anxiety and students’ performance. Euro. J. Contemp. Educ. 9, 271–289. doi: 10.13187/ejced.2020.2.271

Alamer, A., and Almulhim, F. (2021). The interrelation between language anxiety and self-determined motivation; a mixed methods approach. Front. Educ. 6:655. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.618655

Al-Hoorie, A. H., Hiver, P., and In’nami, Y. (2023). The validation crisis in the L2 motivational self system tradition. Stud. Second. Lang. Acquis. 1-23, 1–23. doi: 10.1017/S0272263123000487

Amirian, S. M. R., and Tavakoli, E. (2016). Academic oral presentation self-efficacy: a cross-sectional interdisciplinary comparative study. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 35, 1095–1110. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2016.1160874

Arifin, S., Nurkamto, J., Rochsantiningsih, D., and Gunarhadi,. (2023). Degree of English-speaking anxiety experienced by EFL pre-service teachers in Madiun East Java. AIP Conf. Proc. 2805, 1–6. doi: 10.1063/5.0149282

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 84, 191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Barber, J. D. (2023). The relationship between language mindsets and foreign language anxiety for university second language learners. Int. J. Soc. Educ. Sci. 5, 653–675. doi: 10.46328/ijonses.591

Barlow, D. (2002). Anxiety and disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. London, UK: The Guilford Press.

Bentler, P. M. (1995). EQS structural equations program manual. Encino, California, USA: Multivariate software Encino, CA.

Blöte, A. W., Kint, M. J. W., Miers, A. C., and Westenberg, P. M. (2009). The relation between public speaking anxiety and social anxiety: a review. J. Anxiety Disord. 23, 305–313. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.11.007

British Educational Research Association (BERA). (2018). Ethical guidelines for educational research. British Educational Research Association (BERA). Available at: https://www.bera.ac.uk/researchers-resources/publications/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, USA: Guilford Press.

Browne, M. W., and Cudeck, R. (1993). “Alternative ways of assessing model fit” in Testing structural equation models. eds. K. A. Bollen and J. S. Long (California, USA: Sage).

Cheng, H.-F., and Dörnyei, Z. (2007). The use of motivational strategies in language instruction: the case of EFL teaching in Taiwan. Int. J. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 1, 153–174. doi: 10.2167/illt048.0

Cheung, G. W., and Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 9, 233–255. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

Coskun, A. (2017). The effect of Pecha Kucha presentations on students’ English public speaking anxiety [article]. Profile-Issues in Teachers Professional Development 19, 11–22. doi: 10.15446/profile.v19n_sup1.68495

Csizér, K., and Kormos, J. (2009). Learning experiences, selves and motivated learning behaviour: a comparative analysis of structural models for Hungarian secondary and university learners of English. Motiv. Lang. Ident. 98:119. doi: 10.21832/9781847691293-006

de Armijos, K. Y. (2019) Pecha Kucha: bolstering EFL skills of undergraduate students-an action research study. Proceedings [13th international technology, education and development conference (inted2019)]. 13th international technology, education and development conference (INTED), Valencia, Spain.

Dörnyei, Z. (1998). Motivation in second and foreign language learning. Lang. Teach. 31, 117–135. doi: 10.1017/S026144480001315X

Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner: individual differences in second language acquisition. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Dornyei, Z., and Csizér, K. (2002). Some dynamics of language attitudes and motivation: results of a longitudinal nationwide survey. Appl. Linguis. 23, 421–462. doi: 10.1093/applin/23.4.421

Dörnyei, Z., Csizér, K., and Németh, N. (2006). Motivation, language attitudes and globalisation: a Hungarian perspective. Multilin. Matt. doi: 10.21832/9781853598876

Dörnyei, Z., and Taguchi, T. (2009). Questionnaires in second language research: Construction, administration, and processing. New York, USA: Routledge.

Dörnyei, Z., and Ushioda, E. (2011). Teaching and researching motivation. 2nd Edn, New York, USA: Pearson Education.

Dörnyei, Z., and Ushioda, E. (2013). Teaching and researching: motivation. New York, USA: Routledge.

Dweck, C. S. (2013). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. New York, USA: Psychology press.

Everitt, B. S., and Skrondal, A. (2010). The Cambridge dictionary of statistics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Fahmi, R. F., and Widia, I. (2021). Pecha Kucha technique in developing students’ speaking skills of a foreign language. Thirteenth conference on applied linguistics (CONAPLIN 2020)

García-Pinar, A. (2019). The influence of ted talks on ESP undergraduate students’ L2 motivational self system in the speaking skill: a mixed-method study. ESP Today 7, 231–253. doi: 10.18485/esptoday.2019.7.2.6

Gardner, R. C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning: The role of attitudes and motivation. Cambridge, UK: Edward Arnold Publishers.

Gardner, R. C. (2010). Motivation and second language acquisition: The socio-educational model. New York, USA: Peter Lang.

Gibbons, P. (2002). Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning: Teaching second language learners in the mainstream classroom. Portsmouth, New Hampshire, USA: HEINEMANN.

Goldfrad, K., Sandler, S., Borenstein, J., and Ben-Artzi, E. (2023). The motivation conundrum: what motivates university students in an EAP program? J. Lang. Teach. 3, 19–28. doi: 10.54475/jlt.2023.018

Gurbuz, C., and Cabaroglu, N. (2021). EFL students' perceptions of oral presentations: implications for motivation, language ability and speech anxiety. J. Lang. Linguis. Stud. 17, 600–614. doi: 10.52462/jlls.41

Guyatt, G. H., Oxman, A. D., Kunz, R., Woodcock, J., Brozek, J., Helfand, M., et al. (2011). GRADE guidelines: 7. Rating the quality of evidence—inconsistency. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 64, 1294–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.03.017

Hammad, E. A., and Ghali, E. M. A. (2015). Speaking anxiety level of Gaza EFL pre-service teachers: reasons and sources. World J. Eng. Lang. 5:52. doi: 10.5430/wjel.v5n3p52

Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self-discrepancy: a theory relating self and affect. Psychol. Rev. 94, 319–340. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.319

Higgins, E. T., Klein, R., and Strauman, T. (1985). Self-concept discrepancy theory: a psychological model for distinguishing among different aspects of depression and anxiety. Soc. Cogn. 3, 51–76. doi: 10.1521/soco.1985.3.1.51

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., and Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. Mod. Lang. J. 70, 125–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1986.tb05256.x

Hu, L., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Jiang, C., and Papi, M. (2022). The motivation-anxiety interface in language learning: a regulatory focus perspective. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 32, 25–40. doi: 10.1111/ijal.12375

Jing, L. (2009). Application of oral presentation in ESL classroom of China University of Wisconsin-Platteville. Platteville.

Klassen, R. M., Wang, H., and Rushby, J. V. (2023). Can an online scenario-based learning intervention influence preservice teachers’ self-efficacy, career intentions, and perceived fit with the profession? Comput. Educ. 207:104935. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2023.104935

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd Edn. New York, USA: The Guilford Press.

Leeming, P. (2017). A longitudinal investigation into English speaking self-efficacy in a Japanese language classroom. J. Sec. For. Lang. Educ. 2, 1–18. doi: 10.1186/s40862-017-0035-x

Levin, M. A., and Peterson, L. T. (2013). Use of Pecha Kucha in marketing students’ presentations. Mark. Educ. Rev. 23, 59–64. doi: 10.2753/MER1052-8008230110

Locke, E. A., and Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: a 35-year odyssey. Am. Psychol. 57, 705–717. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.57.9.705

Lorenz, F. O., Wickrama, K., and Conger, R. D. (2004). “Modeling continuity and change in family relationships with panel data” in Continuity and change in family relations: Theory, methods, and empirical findings. eds. R. D. Conger, F. O. Lorenz, and K. A. S. Wickrama (New York, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum).

Mabini, D. A. (2023). Improving persuasive speaking skills using a student-developed template in an online learning environment. J. Lang. Teach. 3, 12–22. doi: 10.54475/jlt.2023.011

MacIntyre, P. D., and Gardner, R. C. (1989). Anxiety and second-language learning: toward a theoretical clarification. Lang. Learn. 39, 251–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1989.tb00423.x

Mak, H. S. (2019). Analysing the needs of EFL/ESL learners in developing academic presentation competence. RELC J. 52, 379–396. doi: 10.1177/0033688219879514

McCroskey, J. C. (1970). Measures of communication-bound anxiety. Speech Monogr. 37, 269–277. doi: 10.1080/03637757009375677

McCroskey, J. C. (1977). Oral communication apprehension: a summary of recent theory and research. Hum. Commun. Res. 4, 78–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.1977.tb00599.x

Meade, A. W., Johnson, E. C., and Braddy, P. W. (2008). Power and sensitivity of alternative fit indices in tests of measurement invariance. J. Appl. Psychol. 93, 568–592. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.568

Ortega, L. (2011). “Second language acquisition” in The Routledge handbook of applied linguistics (New York, USA: Routledge).

Papi, M. (2010). The L2 motivational self system, L2 anxiety, and motivated behavior: a structural equation modeling approach. System 38, 467–479. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2010.06.011

Papi, M., Eom, M., Zhang, Y., Zhou, Y., and Whiteside, Z. (2023). Motivational dispositions predict qualitative differences in oral task performance. Stud. Second. Lang. Acquis. 45, 1261–1286. doi: 10.1017/S0272263123000220

Papi, M., and Khajavy, H. (2023). Second language anxiety: construct, effects, and sources. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 43, 127–139. doi: 10.1017/S0267190523000028

Ritonga, S. N. A., Nasmilah, N., and Rahman, F. (2020). The effect of motivation and anxiety on students’ speaking performance: a study at Dayanu Ikhsanuddin university. ELS J. Interdiscip. Stud. Human. 3, 198–213. doi: 10.34050/els-jish.v3i2.10263

Shi, X., Brinthaupt, T. M., and McCree, M. (2015). The relationship of self-talk frequency to communication apprehension and public speaking anxiety. Personal. Individ. Differ. 75, 125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.023

Smith, C. M., and Sodano, T. M. (2011). Integrating lecture capture as a teaching strategy to improve student presentation skills through self-assessment. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 12, 151–162. doi: 10.1177/1469787411415082

Soureshjani, K. H., and Ghanbari, H. (2012). Factors leading to an effective oral presentation in EFL classrooms. TFLTA J. 3, 37–50,

Susanto, F. (2022). Students’ perceptions on the use of Pecha Kucha to minimize students’ public speaking anxiety Universitas Kristen Satya Wacana. Indonesia

Taguchi, T., Magid, M., and Papi, M. (2009). The L2 motivational self system among Japanese, Chinese and Iranian learners of English: a comparative study. Motiv. Lang. Ident. 36, 66–97. doi: 10.21832/9781847691293-005

Teimouri, Y. (2017). L2 selves, emotions, and motivated behaviors. Stud. Second. Lang. Acquis. 39, 681–709. doi: 10.1017/S0272263116000243

Ushioda, E., and Dörnyei, Z. (2009). “Motivation, language identities and the L2 self: a theoretical overview” in Motivation, language identity and the L2 self. eds. Z. Dörnyei and E. Ushioda (Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters).

Woodrow, L. (2006). Anxiety and speaking English as a second language. RELC J. 37, 308–328. doi: 10.1177/0033688206071315

Wu, H. (2019). A corpus-based analysis of TESOL EFL students’ use of logical connectors in spoken English. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 9:625. doi: 10.17507/tpls.0906.04

Wu, H. (2022). Exploring the factors affecting the performance of EFL learners’ oral presentation: a structural equation modeling study. Available at SSRN 4259156.

Wu, Y. T., Foong, L. Y. Y., and Alias, N. (2022). Motivation and grit affects undergraduate students’ English language performance. Euro. J. Educ. Res. 11, 781–794. doi: 10.12973/eu-jer.11.2.781

Ye, L. (2014). A comparative genre study of spoken English produced by Chinese EFL learners and native English speakers. TESL Canada J. 31:51. doi: 10.18806/tesl.v31i2.1176

Yusoff, R., and Mohd Janor, R. (2014). Generation of an interval metric scale to measure attitude. SAGE Open 4, 215824401351676–215824401351616. doi: 10.1177/2158244013516768

Zhang, X., and Ardasheva, Y. (2019). Sources of college EFL learners' self-efficacy in the English public speaking domain. Engl. Specif. Purp. 53, 47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.esp.2018.09.004

Zhang, X., Ardasheva, Y., and Austin, B. W. (2020). Self-efficacy and english public speaking performance: a mixed method approach. Engl. Specif. Purp. 59, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.esp.2020.02.001

Zharkynbekova, S., Zhussupova, R., and Suleimenova, S. (2017), Exploring Pecha Kucha in EFL learners’ public speaking performances. [Proceedings of the Head'17 - 3rd International Conference on Higher Education Advances]. 3rd International Conference on Higher Education Advances (HEAd), Univ Politecnica Valencia, Fac Business Adm & Management, Valencia, SPAIN.

Appendix

Questionnaire Items

Read the following statements and choose a number from 1 to 7 to indicate how much anxiety you felt in the oral presentation.

1: strongly disagree; 2: disagree; 3: somewhat disagree; 4: either agree or disagree; 5: somewhat agree; 6: agree; 7: strongly agree

Ideal L2 Self:

1. I can imagine myself delivering an oral presentation fluently.

2. The things I want to do in the future require me to deliver an oral presentation in English.

3. I imagine myself as someone who is able to deliver an oral presentation in English.

4. I can imagine myself delivering an English presentation as if I were a native speaker of English.

Ought-to L2 Self

1. Delivering oral presentations in English is important to me in order to gain the approval of my teachers.

2. Delivering oral presentations in English is important to me because the people I respect expect me to be good at it.