94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Educ. , 24 June 2024

Sec. Language, Culture and Diversity

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1383977

K. Pavithra†

K. Pavithra† S. N. S. Gandhimathi*†

S. N. S. Gandhimathi*†The use of movie as an audio-visual multimodal tool has been extensively researched, and the studies prove that they play a vital role in enhancing communicative competence. Incorporating authentic materials like movies, television series, podcasts, social media, etc., into language learning serves as a valuable resource for the learners, for it exposes them to both official and vernacular language. The current study aims to systematically analyze the preceding studies that conjoined English movies into the curriculum to teach English. It also examines and evaluates the empirical research that various researchers conducted from 2000 to 2023. The articles were primarily sourced from prominent academic databases such as ProQuest, ScienceDirect, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied in screening the 921 sources, of which 23 empirical studies were eligible for the review as a result of a three-stage data extraction process as shown in the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses” (PRISMA) chart. The extraction of data from the review encompasses an overview of the empirical studies, methodologies, participants, and interventions. The extracts were systematically analyzed using the software’s End Note and Covidence. The analysis of the existing literature and experimental data substantiates that teaching and learning English as a second or foreign language using movies as teaching aids exhibit promising prospects for enhancing English language proficiency. The findings of the study reveal different genres of movies that aid the facilitator in producing effective instruction materials with clearly defined objectives and guided activities. It is also observed that the learners have a positive experience with long-term learning benefits.

The contemporary landscape of education is characterized by a dynamic and continuously evolving system wherein novel pedagogical models are developed regularly. The integration of resources in English language classrooms adheres to certain criteria, like educative, practical, informative, and investigative. These criteria are essential, as they serve to enlighten and offer valuable insights to the language learners (Nikoopour and Farsani, 2011). It has been proven by various studies that there is an increasing demand for innovative educational resources in almost all the disciplines. According to Kanwal (2023), India possesses a highly significant network of higher learning institutions on a global scale. The contemporary educational landscape has witnessed a notable shift in the realm of teaching materials. Teaching materials are no longer limited to printed ones, the modern curricula have embraced a paradigm that promote technical, multimodal, and practical learning approaches, catering to the unique needs and preferences of the new generation of learners.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought significant challenges in the education sector, particularly in terms of addressing disparities in the access of technology based on economic status, outdated curricula, limited funding and resources, inadequate technical knowledge of the teachers, inequal teacher-student ratio, and time limitations for online sessions on digital platforms. These issues have had a detrimental impact on the quality of education. Consequently, there has been a recurrent dependability on technology to sustain the pedagogical process. Donaghy and Xerri (2017) says, “In today’s digital world, there are no classrooms without course book images, photographs, paintings, cartoons, picture books, comics, flashcards, wall charts, YouTube videos, films, student-created artwork, media, and so on, that foster communicative competence and creative aspects in the learners.” In the context of an increasingly digitalized pedagogic process, educators are more dependent on the diverse range of resources to inspire and engage learners. Several studies have been conducted to investigate the impact of utilizing audio-visual aids in educational settings. The findings of these researches have consistently indicated that visual stimuli play a significant role in facilitating incidental learning and strengthening the existing knowledge of the learners (Alharthi, 2020).

The visual language of movies has played a pivotal role in shaping and reflecting cultural norms and values for almost a century. The art of motion pictures has gradually evolved to become a powerful force that influences various modes of information (Swain, 2013). The observed phenomenon possesses the capacity to establish an emotional bond with the observer, thereby facilitating their ability to identify with and comprehend situations that they encounter in their real life. Irrespective of their learning abilities and family background, watching movies sparks discussions, fosters communication, and creates awareness. Furthermore, movies serve as a gateway to knowledge about diverse substantial problems such as gender diversity, climate change, literacy, poverty, governance, democracy, violence, and many more issues that link classrooms to society. As stated by Alharthi (2020), previous studies have indicated that the inclusion of classroom activities that are directly aligned with the content of a movie can enhance the effectiveness of movies within educational environments. According to Tabatabaei and Gahroei (2011) research findings, movies are reliable language sources. They have the ability to expose viewers and learners to a wide range of linguistic elements, such as authentic contexts, diverse native speakers’ voices, colloquial language, rapid speech patterns, variations in stress, accents, and regional dialects.

Tickoo (2003) remarks that “language is a social organism,” emphasizing its significance in the process of socialization. This perspective highlights the crucial role that language plays in the development and integration of individuals in the society. For instance, children cannot learn a language on their own; they learn from their parents, siblings, friends, and relatives by hearing, looking at, and observing them. After achieving proficiency in the skill, it is discovered that using verbal language becomes the most significant method for establishing meaningful connections with others. Studies in the past have consistently demonstrated that the acquisition of a new language necessitates a well-rounded approach encompassing effective language instruction and practical application in real-world settings. Movies serve as a reliable medium through which viewers can engage with characters who authentically portray and embody various aspects of human existence.

Supplementary teaching materials help the learners achieve a comprehensive and immersive language learning experience, thus contributing to the development of language proficiency. The instructional tools facilitate the learners’ independent utilization of educational content, requiring minimal assistance or intervention from instructors. A movie is a form of supplementary material that persuades English as a Foreign Language (EFL) or English as a Second Language (ESL) learners. It is believed that movies embody the concept that “a film with a story wants to be told rather than a lesson that needs to be taught” (Ward and Lepeintre, 1996; Tabatabaei and Gahroei, 2011). As stated by Fisch (2000), the comprehension of an educational film is influenced by both the lucidity of the educational material and the narrative framework in which the educational messages are embedded. Chapple and Curtis (2000) reveal that the learners, irrespective of their age, possess a strong inclination towards watching movies. This evidence indicates that it is feasible to design programmes and classroom activities that are highly student- -centered. Wood-Borque (2022) claims that the use of movies as a teaching aid facilitates learning beyond the classroom. This approach not only promotes the acquisition of knowledge but also makes education more holistic and encourages the learners to cultivate new skills and interests.

The objectives of the present study are to:

1) Systematically identify and critically review interventional studies conducted within the time frame of 23 years (2000–2023).

2) Examine the diverse approaches, methodologies employed, and the language skills focused.

3) Conduct a comprehensive analysis of the various genres and categories of films used for the language learners.

4) Determine the ideal duration for the screening process.

5) Investigate the activities employed in the preceding studies.

The current study strives to answer the questions given below:

RQ.1: What methodologies and activities were employed in the previous studies to enhance the linguistic proficiency of the English language learners?

RQ.2: Which genre/category is preferred by the researchers and language instructors for the intervention?

RQ.3: Which is the most suitable intervention: clippings, segments, or full movie? And what is the ideal time duration for screening them.

The study was conducted as a systematic review, aiming to scrutinize interventional studies comprising diverse research designs. The analysis was carried out using the PRISMA 2020 checklist provided by Page et al. (2020). In December 2023, an extensive search was made with databases to identify empirical studies about the use of movies as a tool for teaching and learning the English language. The investigation specifically focused on the years spanning from 2000 to 2023, with an emphasis on the various language aspects and skills that were targeted in these studies. The present study employs the software tools “Endnote” and “Covidence” for data extraction. The data extraction encompasses quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method studies that exclusively employ movies as an intervention to enhance English language skills among learners from diverse nations. The review undertakes an in-depth study of multiple elements like, overview of the empirical studies, methodologies, participants, and interventions, by employing rigorous inclusion and exclusion criteria. Additionally, the data extraction protocol was modified to capture potential impressions, challenges, and limitations associated with using movies as a pedagogical aid in the context of English language instruction.

The systematic process includes examining data derived from five distinct databases. The primary objective is to identify and inspect existing studies pertaining to the utilization of films as a pedagogical tool in the domain of English language instruction and learning. The bibliographic academic databases reviewed in the study include ProQuest, ScienceDirect, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. Upon conducting a thorough search using the ‘search string,’ (as mentioned in Table 1) a total of 921 references were identified. The references were subsequently exported to the Endnote software for further analysis and organization.

The data from the bibliographic databases for the study were obtained through the access provided by Vellore Institute of Technology (VIT), Vellore, India. Initially, the search terms employed were “English Language Teaching using Movies,” “Using Film for Language Teaching,” “Movies for English Language Teaching,” and “Movies as Teaching Supplements.” Since these search queries did not produce pertinent outcomes, advanced search functionality was employed using the search string as mentioned in Table 1. The references procured from the databases comprised a wide range of scholarly sources, such as journal articles, conference proceedings, book chapters, and review articles.

The Endnote software was used to facilitate the identification and segregation of duplicate references obtained from the bibliographic databases. Though 921 references were subjected to the deduplication process only 892 references were retrieved and exported to conduct the screening process (as presented in Table 2). The Covidence software, a widely used tool in systematic reviews, was employed to conduct the screening process for the references. Notably, this software effectively identified and flagged two instances of duplicate references, subsequently excluding them for further consideration. The process of title and abstract screening was conducted in accordance with predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Specifically, research reports that contained empirical studies and were published between the years 2000 and 2023 were manually selected for further consideration. The research articles and studies that did not incorporate the utilization of motion pictures as a means of investigation were deemed ineligible for inclusion in this study. Some studies used movies for the experiment, but it is worth noting that these studies were written in other languages. Few studies focused on using movies to develop languages like Korean, Chinese, and Spanish. The Inclusion and Exclusion criteria for the screening process are clearly stated in Table 3. During the preliminary screening phase, a total of 231 studies were identified as irrelevant and subsequently excluded from further analysis. Following this, a subset of 92 studies proceeded to undergo a comprehensive full-text review. A total of 72 studies were excluded from the analysis by the predefined exclusion criteria outlined in the PRISMA table (Figure 1). The data extraction template has been modified by the researcher to suit the requirements of the study. These modifications were necessary as the template provided in Covidence was originally designed for clinical research and health studies, which may not align perfectly with the specific objectives of the current research.

The data extraction template has been modified to include various data items. These items include the title of the research, the author’s name, the year of publication, the country of origin, the aim of the study, the area of focus, the skills addressed in the research, the research design employed, the research questions posed, the theoretical framework utilized, the methodology employed, the data analysis techniques employed, the nationality of the participants, description of the population, their age, education level, language proficiency, sample size, number of participants in the control group, number of participants in the experimental group, the genre of movies used in the study, the movies screening time, number of sessions/time duration of the study, and the activities used in the study.

An overview of the aim, area-focused, and skill-focused, as well as inferences from the included studies, is presented in Table 4. The empirical studies that were reviewed were published between 01 January 2000 and 01 December 2023.

As depicted in Figure 2, the studies that were reviewed had been published after 2000. The selected time frame for analysis pertains to a period characterized by the gradual digitization of education. Regardless of the continuous emergence of various technologies, it is noteworthy that films, functioning as audiovisual multimodal aids, hold a distinct position within the pedagogical domain. In the year 2022, a greater number of publications (22%) are observed compared to the other years. For example, in 2023, 3 (13%) studies were published, between 2016 and 2021, a total of 5 (22%) studies were published, followed by 6 (26%) studies between 2013 and 2015, and finally, 4 (17%) studies between 2000 and 2012. Among these publications, it was found that 10 (43%) studies originated from Middle East regions such as Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Iran, and Iraq; 7(30%) studies were conducted in European regions like Spain, Sweden, North Macedonia, Serbia, Bulgaria, Ukraine, and Georgia; and 3 (13%) studies were carried out in East Asian regions like China, Japan, and 3 (13%) studies were conducted in South East Asian regions like Indonesia and Malaysia.

The studies surveyed focused on teaching and learning the English language and excluded other languages like Korean, Spanish, and Chinese. As illustrated in Figure 3, the review analyzed the various research domains namely EFL, ELT, ESL, and ESP. It was observed that a total of 17 studies, accounting for 74% of the sample, focused on the teaching and learning of English as a Foreign Language (EFL). Additionally, 3 studies, representing 13% of the sample, were dedicated to the topic of English Language Teaching (ELT). Further, a study, comprising 4% of the sample, was found to address the field of English as a Second Language (ESL). Lastly, two studies, constituting 9% of the sample, delved into the area of English for Specific Purposes (ESP).

The research articles examined cover the major English language skills such as vocabulary (general and specific), writing (narrative), speaking skills (oral skills, length of utterance, lexical development, mean length of utterance, public speaking), interpersonal communication, grammar (sentence patterns), idioms, learning performance, culture, critical thinking, short- and long-term retention, motivation, and the learners’ interest.

The empirical research conducted during the selected years is analyzed in the review, wherein different methodologies were employed to explore the efficacy of movies as pedagogical instruments. Specifically, the impact of films on the language proficiency of students across diverse age groups, educational backgrounds, and linguistic proficiency is the focus of the investigation. The data gathered offer useful insights into the various ways that movies can affect the process of language acquisition. Twenty-three studies were carefully examined, and they placed a strong emphasis on improving English proficiency. Though the studies yield positive outputs, it was observed that ignoring their methodologies would make the review incomplete. The methodologies in each research article convey the importance of inculcating multimodal aids in the language classrooms.

A corpus of audiovisual materials suitable for EFL classrooms was compiled by Wood-Borque (2022). Two questionnaires were administered by the researcher to two distinct groups of learners. The first questionnaire was administered among secondary level learners. The analysis of the data reveals the ‘most preferred’ movies (as mentioned in Table 6) by the learners’ to be screened in the classroom. The second questionnaire was administered to the tertiary level learners. It analyzed the learners’ attitudes and perceptions pertaining to the incorporation of movies in language education. The study did not involve an intervention; however, the findings from the questionnaires articulate the learners’ movie preferences and their perceptions regarding the use of movies in an EFL classroom, aiming to enhance interaction and motivation. Furthermore, it is emphasized that instructors and researchers should cross check all the movie preferences of the learners before considering them for screening. The effectiveness of integrating movies in an EFL classroom is investigated by Goctu (2017) through the screening of movies and the administration of a questionnaire. The inferences from the study reveal a positive attitude among the learners towards the use of movies as a tool for improving their EFL competence.

Though methodology for teaching and learning is observed to have various strategies, understanding the learners’ attitudes and perceptions towards utilizing the movies as a multimodal aid is also very important. Chapple and Curtis (2000) seek the use of film for content-based instruction and try to perceive learners’ notions of the implementation. The researcher conducted a course titled “Thinking through the Culture of a Film: a communicative approach,” whose curriculum had activities based on screening films. As per the curriculum, the movies were chosen by the learners and finalized by the instructor. Films were screened, followed by activities and a questionnaire to self-assess their progress. The findings of the data collected disclose that there was a significant improvement in the learners’ language skills, critical thinking, academics, motivation, and confidence.

Muthmainnah et al. (2022) scrutinized the consequences of the “Social Media-Movies Based Learning Project” (SMMBLP) on the learners’ English language skills and their motivation. The SMMBLP project was implemented for a whole semester to help the learners improve their language comprehension. The project was developed using Information and Communication Technology (ICT) tools. The study uses the system approach of conducting a pre-test, a researchers’ intervention, and a post-test. It can be inferred from the findings that the implementation of the SMMBLP in language classrooms facilitates English language learning comprehension and is considered a promising alternative pedagogic model. In their study, Jusufi and Jusufi (2023) examined the efficacy of movies and pictures as instructional materials in a foundational English course. The research design comprised several stages, beginning with a pre-test to evaluate the learners’ existing language proficiency. Following the pre-test, an intervention was implemented, succeeded by the administration of a questionnaire and a group interview. The analyzed data reveals the significance of effective English language communication skills and the advantages associated with the utilization of visual materials like movies and pictures in the language classroom.

The “Action research method” by Hu et al. (2022) expounds the educational functions of the English language in children’s movies, through a survey to analyze and summarize the functions of film through teaching activities (as mentioned in the 3.5 overview of activities), followed by interviews. The findings state that using movies for pedagogical purposes seizes the learners’ attention, which is advantageous to the instructors in imparting language knowledge. Sert and Amri (2021) used the theoretical and methodological framework of “conversation analysis” to seek the learning prospects offered by a film in an EFL task-based language classroom. The study collected data by screening excerpts of a popular biographical film, followed by task-based activities, which were video-recorded to observe the “Collaborative Attention Work” (CAW). The study documents the connection between audio-visual elements shown to aid the learners’ language development and their usage to improve classroom interactions and language comprehension.

Ismaili (2013) examined whether viewing movies shape the learners’ linguistic comprehension. The author used two books which have their movie versions also. The control group had to read the textual material, whereas the experimental group got to watch the movie and read the books as well, followed by activities that stimulated the learners’ reading, writing, oral, and critical thinking. The results of the study show significant differences in the performance of both the groups. The experimental group has shown fruitful results after the treatment.

Tickoo (2003) asserts that young learners begin their journey through language acquisition by listening to spoken words or sounds uttered by the people around them, thereby emphasizing listening as one of the fundamental skills of human beings. Safranj (2015) explored the development of listening comprehension by screening films for a group of learners with and without subtitles. Questionnaires and oral interviews were conducted to understand the learners’ perspectives on learning listening skills using films. Their suggestions regarding the quality of the approach were also recorded. The descriptively and statistically supportive data help to infer that using movies with subtitles must be one of the most constructive means to yield the learners’ English language listening competency.

It is explicit from the previous studies that the inclusion of subtitles in movies is a constructive method, but it was disproved in the study by Başaran and Köse (2013), when they examined the transformations on the learners after screening the movies with English captions, Turkish captions, and no captions. The selected movies were screened to three groups (1-English captions, 2-Turkish captions, 3-no captions) of people, followed by a Multiple-Choice Question (MCQ) test focusing on their listening skills. The study included learners who were not of the same language proficiency level. The groups with English and Turkish captions comprised participants with lower intermediate language competence, while the group who watched the movie without captions consisted of participants from an intermediate level. The collected data was subjected to statistical analysis using a one-way ANOVA, which ensures that the same level of efficiency is shown by the learners from both the groups. The conclusion is led by the fact that an equivalent language proficiency level is required from the learners for significant improvement when using captions in movies for effective pedagogy.

Dikilitas and Duvenci (2009) pilot the influence of multimodal learning theory in improving oral skills in an English Language Teaching (ELT) classroom, applying the pre-and post-test design. In the experimental study, the control group reads only the text and listens to the dialogues from the movie, whereas the experimental group watches the excerpts of the movies and discusses them in the form of oral repetition and creative speech. The transcribed and descriptively analyzed data uncovers that using excerpts of movies as multimodal aids enhance the learners’ length of speech, utterance, and lexical proficiency (oral skills). Another study carried out recently by Kinasih and Olivia (2022) examines how the use of film enhances the learners’ public speaking skills through screening court-themed movies, through pre-and post-tests, questionnaires, and semi-structured interviews. The statistically and descriptively analyzed data promulgates that there is a significant improvement in the learners’ public speaking ability.

It is very important for every instructor to be a proficient speaker. Lee (2019) studied the perceptions of teachers on using movies as authentic video materials in classrooms. The study was conducted among pre-service teachers to strengthen their interpersonal competence and critical thinking. The intervention used excerpts from 41 movies whose themes and contents were analyzed and coded to show the ideas from the text, followed by activities like group discussions, dramatic dialogue practice, self-report, short discussions, and debates. The study disclosed that movies in the language classroom improved the learners’ attention span, language comprehension, educational values, inspiration, and motivation.

Alsubaie and Madini (2018) express that literacy requires the ability to effectively articulate one’s thoughts and emotions through writing. However, learners encounter difficulties in this regard because they frequently lack the vocabulary and writing skills necessary to produce coherent written compositions. So, efforts are taken to enhance the writing skills in various pedagogical approaches and instructional materials. Aziz and Fathiyyaturrizqi (2017) examined the advantages of using movies to enhance junior high school students’ narrative writing abilities. The phenomenon was investigated using the “Classroom Action Research (CAR)” methodology by the researchers. The researcher conducted the preliminary study using a mix of classroom observation and interviewing as data collection methods. This study aimed to gather information regarding the difficulties in writing experienced by the learners. The screening of films was carried out for two sessions, during which students engaged in mind mapping, journaling, and narrative writing activities through provided worksheets. The findings of the study indicate that the use of movies as an additional resource has a positive impact on improving the learners’ English language proficiency and narrative writing skills.

A mixed methods study was undertaken by Abdulrahman and Kara (2023) to analyze the distinction between Extensive Reading (ER) and Intensive Reading (IR) among the tertiary-level learners to find out their impact on vocabulary acquisition and speaking proficiency, particularly to get through the “Internet-based Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL iBT)” examination. The Data were collected from both the control and experimental groups. The control group engaged in IR with novels, while an experimental group was directed to read novels and view movie adaptations of those novels as a part of an ER program. The data collection process involved a pre-intervention test, followed by the implementation of IR and ER programs, concluding with a post-test assessing “TOEFL iBT” speaking and vocabulary skills. The findings indicate notable improvement in vocabulary and speaking abilities among the learners in the experimental group.

A research study (Alharthi, 2020) has used a “corpus-based sampling approach” to describe how watching English movies with subtitles as a part of incidental learning and using instructional materials as intentional learning can affect the “productive and receptive vocabulary skills” of the learners. A corpus analysis of the high-frequency words using “Vocabprofile BNC-20” software for both the script of the film used in the study and the text materials was run, followed by a screening of the movies, and conducting assessments to test the learners’ “receptive and productive vocabulary skills” after the screening. The descriptive and statistical evidence demonstrates that it is a reliable strategy for practising and honing the “productive and receptive vocabulary skills” of the learners.

Instructors believe that learning vocabulary is vital for any learner, but remembering and recalling them are also equally important. Brown (2010) conducted a study to ascertain the degree to which the learners can recognize and recall cultural vocabulary in popular English-Speaking Foreign Films (ESFF) and exercise activities in classrooms to nurture the learners’ vocabulary skills by administering questionnaires, pre-screening, while screening, repeated screening, and post-screening in the span of 4 weeks. The data collected and analyzed infer that using movies, especially “ESFF,” in ELT classrooms following pertinent methodology and activities help the learners improve their vocabulary and other language comprehension aspects for the long term.

Haghverdi (2015) examines the assimilation of songs and movies to study the learners’ vocabulary, grammar, and rhythmic patterns by conducting a pre-test, screening clippings of movies, followed by activities related to improving vocabulary and writing skills, and administering a questionnaire. The statistically apparent data of the experimental study discovers that the inclusion of songs along with movies can be an innovative way to promote learning in a language classroom. In a similar study by Khadawardi (2022) movies were screened with subtitles in the online English language classrooms to facilitate the development of vocabulary and short- and long-term retention among the learners. The quasi-experimental study, where a single group of learners underwent a pre-test, followed by conventional teaching using text materials as well as movie clips as teaching aids and post-test. Interviews were conducted to know the learners’ opinions on the advantages and disadvantages of enforcing subtitled movie clips in English language classrooms. The statistically discernible data suggest that the approach has aided the learners to develop their vocabulary, pronunciation skills and understand the authenticity of the English language. The transcriptions of the interviews infer that the learners showed a positive response towards using film as a multimodal language teaching aid.

Kucukyilmaz et al. (2015) examines the applicability of military-themed films to teach specific vocabulary (military terminology) in an English for Specific Purposes (ESP) classroom. The experimental study collected data by conducting a pre-test, followed by one group of learners undergoing conventional textual learning, and the other group using movies. Both groups gave a post-test, and the results provide convincing evidence that films are valuable and advantageous resources in ESP instruction. In a similar study, Korieshkova and Didenko (2023) used movies to teach maritime English, emphasizing the discipline-specific speaking, and vocabulary skills, and safety awareness within the context of a mariner’s professional life. The study utilized a two-group design, incorporating a pre-test followed by an intervention. The control group was exposed to conventional teaching methods, while the experimental group received the same traditional instruction along with supplementary lessons, including feature films and educational films. The research involved the implementation of a movie-based learning approach as an intervention to assess the impact on the English language proficiency of the experimental groups. The results of the test indicated a significant improvement in the discipline-specific communication skills of the experimental group compared to the control group.

A few studies reviewed have accommodated film in EFL classrooms to facilitate the learning of idioms. Tabatabaei and Gahroei (2011) pilot the efficacy of using movie clips that include idioms among the learners. The researchers conducted two MCQ tests as pre- and post-tests to observe the before and after-effects of the treatment. The findings suggest that using movie clips has a considerable impact on learning idioms. In addition, both the instructors and learners exhibit favorable views towards the use of movie clips to teach and idioms. Khoshniyat and Dowlatabadi (2014) employs Disney movies to teach conceptual metaphors, a methodology that was theoretically proposed by Rodriguez and Moreno (2009). The revelations state that utilizing films in teaching idioms is a successful method to improve learners’ interest and imagination, and to enable their retention.

The data extracted have the subsection of a summarized information of the subjects who participated in the various research interventions. The details like sample size of the study, participants’ education, their language level and, age are presented in Table 5. Altogether, 13 (56.52%) studies were conducted among learners pursuing higher education (undergraduate, post-graduate, and higher studies); 9 (39.13%) studies were conducted among school-level learners (senior secondary school, secondary school, high school, middle school, and primary school); 1 (4.35%) study focused on teacher training students. The learners were observed to have different language proficiencies: 5 (22%) studies on intermediate level learners (lower-intermediate, intermediate, and upper-intermediate); 4 (17%) studies on basic level learners; 1 (4%) study on proficient level learners; 2 (9%) studies on mixed learners (basic, intermediate, and advanced); and 11 (48%) studies did not mention their learners’ language proficiency levels.

The review answers the research question (RQ2) through the data extracted in a subsection of interventions, including data regarding the type and genre of movies chosen by the instructors for screening, the ideal time duration to screen a movie, and the number of sessions in weeks, days, or hours for the experiment (Table 6).

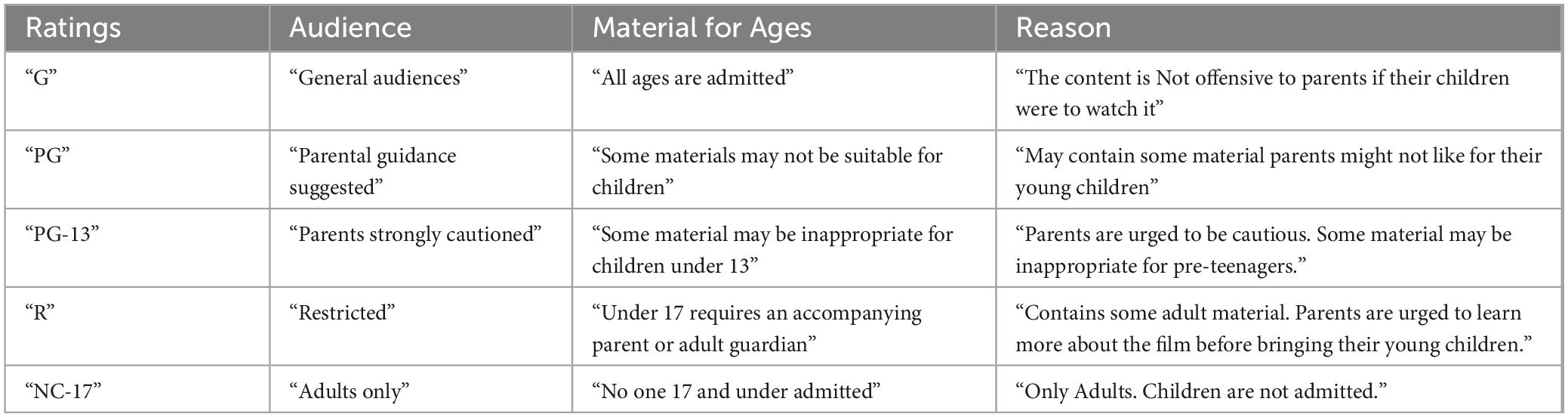

In response to RQ 3, the type or genre and the ideal time limit for screening a movie preferred by the researchers and language instructors were identified. Most studies do not mention any type of genre but state that they choose the film for the class or intervention based on the learners’ profiles. The learners’ profile includes the age of the learner, language proficiency, learning style, learning preferences, etc. (Avallone, 2022). The movie chosen for the screening should be age-appropriate, which means it must not include obscene words or scenes and must have a “G” (General Audience) /”PG” (Parental Guidance Suggested) rating. The Webpage for film ratings run by “The Motion Picture Association” (Motion Picture Association of America, 2020), since 1968, has a revised edition (July 2020) of the “classification and rating rules” (Table 7), provided by the “Classification and Rating Administration” (“CARA”).

Table 7. Movie ratings for different ages; Source: Motion Picture Association of America, 2020.

The instructor should possess a comprehensive understanding of the “copyright and fair use policy” to effectively navigate the legal and ethical considerations pertaining to the use of copyright materials. In accordance with the terms and conditions of certain streaming services, there exists a provision wherein streaming content is exclusively offered for benefit of the individuals. In such cases, the instructor has the option to sign up for educational-streaming services like “FluentU,” “Babbel” etc, which offer a selection of carefully curated materials specially tailored to the needs of the learners. According to Herrero (2019), the movie chosen for screening must have educational content and themes; the duration of the film depends on the time available in the academic space or the duration of the intervention. The film can be screened as a whole movie, divided into segments for each session to work on some activity, using clippings of short time intervals or curated content from multiple films. The data (Figure 4) from the review infers that, 7 (30.43%) studies used clippings, 9 (39.13%) studies included full movies for the intervention, and 3 (13.04%) studies used movies in segments, whereas 4 (17.39%) studies have not mentioned the details of the time duration of the movies screened for the interventions.

The instructor must also pay close attention to factors like language, religion, culture, and geography of the learners. “The usefulness of the film comes not only from the films but also from the surrounding environment and the activities associated with the classroom input” (Alharthi, 2020). But the previous studies have not provided sufficient data to determine the ideal duration for screening movies in an intervention and conducting an intervention, as they vary, ranging from one session lasting 3 h to a whole semester.

The “Berkeley University of California” (GSI Teaching & Resource Center, 2023) states that when the learners participate in learning tasks, they retain more information, figure out how to apply and extend their new knowledge. These tasks cater to the needs of the learners who have different learning styles. It is also observed that different types of activities have been included in the studies to improve different aspects of communicative competence or general English language skills. Activities like, small group and whole group discussions, brief quizzes, brainstorming, teacher-led instructions, worksheets, and students-led presentations were conducted by Chapple and Curtis (2000). Ismaili (2013) included activities like reading, brainstorming, quizzes, summary writing, and oral exercises, while Goctu (2017) utilized group discussions and activities to analyze language and literary aspects among the learners. Sert and Amri (2021) and Hu et al. (2022) initiated group discussions and narrations, situational dialogue, role-play, and mutual evaluation, and contributed to the repertoire in enhancing the learners’ English language competence.

Refining the learners’ listening skills included the English MCQ test and the listening comprehension test (Başaran and Köse, 2013). Aziz and Fathiyyaturrizqi (2017) engaged the learners in post-screening of films to work on mind mapping sheets, student writing sheets, and journal sheets to help them get better at writing. Dikilitas and Duvenci (2009) included activities like oral repetition and creative speaking in their study, and Lee (2019) screened movies with some follow-up activities like group discussions, dramatic dialogue practice, self-reporting, short discussions, and debates to improve the learner’s oral English language skills. Abdulrahman and Kara (2023) implement group discussions, quizzes, pair and group activities in their ER program, while, Korieshkova and Didenko use vocabulary activities, MCQ quizzes, roleplay, and descriptive writing to enhance the learners’ vocabulary and speaking skills.

Alharthi (2020) used movies with subtitles to improve the learners’ vocabulary by applying the MCQ receptive task to recognize the meanings of vocabulary and fill the blanks as a task to retrieve the correct meaning of vocabulary. Brown (2010) involved the learners with activities like discussion on vocabulary, script correction, sequencing scenes, and short and long answer tests, whereas other authors like Haghverdi (2015) asked the learners to jot down the new or unknown words, idioms, and phrases and write a summary of the movie and Khadawardi (2022) included multiple activities related to writing tasks, speaking, and grammar to learn the target vocabulary from the movie screened.

According to Wood-Borque’s (2022) findings, learners show interest to learn through activities which involve the participants to respond and work with various authentic resources. Using the scripts of the movies screened as a tool for designing activities is suggested in the study, with the idea to code them into segments related to the topic being discussed. For instance, active vocabulary, modal verbs, collocations etc., can be highlighted in the script and to design innovative activities. However, some studies have suggested certain strategies to design activities by using movies, movie clippings, captions, and movie scripts but in their research articles, they have not mentioned the type of activities they have used for the research intervention (Tabatabaei and Gahroei, 2011; Khoshniyat and Dowlatabadi, 2014; Safranj, 2015; Kucukyilmaz et al., 2015; Wood-Borque, 2022; Kinasih and Olivia, 2022; Muthmainnah et al., 2022; Jusufi and Jusufi, 2023).

The current study reviewed and analyzed empirical researches which integrated movies into the classroom activities. It also reviewed the articles from the years 2000–2023 to identify the methodologies and activities that were exercised in the previous studies to enrich the linguistic proficiency of the English language learners (RQ1), the genres or types of movies (RQ2), and the ideal duration of the film preferred by the researchers and instructors for the intervention (RQ3). The empirical studies have exclusively used movies as a teaching supplement for the learners to improve their skills such as listening, speaking, reading, writing, vocabulary, communicative competence, motivation, interest, attention, and critical thinking in English language classrooms. Sand (1956) and Aziz and Fathiyyaturrizqi (2017) claim that film makes language classes more amusing and motivating for both the instructors and the learners.

The review identifies the pre-and post-test conducted as the most utilized methodology in the research reports. It is one such method that helps the researcher keep track of the learners’ progress before and after the treatment. “Classroom Action Research” (CAR) is a methodology that has shown positive results in the learners’ English language improvement. According to Aziz and Fathiyyaturrizqi (2017), “CAR is a methodology that involves a cyclic process with four basic steps of planning, acting, observing, and reflecting.” Questionnaires, structured interviews, unstructured interviews, feedback, self-reflective reports, and observations were used to infer deeper qualitative information about the learners’ language needs. The study implies that incorporating movies as teaching aids in the form of short clippings followed by visual-auditory interactive activities prove successful. The instructor must be aware of various factors like time constraints, lack of appropriate places, shortage of equipment, copyrights and fair use policies, rating of the movie, previewing the movie more than once, collecting the script of the movie, and preparing a lesson plan for the sessions while choosing the material for the classes. Before choosing the material, they should keep in mind the language proficiency of the learners by either conducting a needs analysis or an English proficiency test. According to Alharthi (2020) sufficient visual exposure, feedback, and strategies for managing multiple inputs (visual and audio) simultaneously should be provided to learners by the instructors.

The studies help to understand that needs analysis plays a major role in understanding the learners’ needs, and every instructor must try to meet them with relevant teaching materials and aids. The needs analysis also helps the instructor choose the materials that will help the learners improve their language skills. Most educational institutions emphasize the use of technological devices in the classroom (Wood-Borque, 2022). There are various other sources apart from printed material, but using the movies makes it more student-centered.

According to Cubillos (2000) and Aziz and Fathiyyaturrizqi (2017), movies can help the learners in a) learning new vocabulary, b) enhancing their knowledge of grammatical structure with more advanced error correction and feedback activities, c) improving academic reading and writing, d) enabling instructors to monitor learners’ language performance, e) fostering motivation, and f) developing instructional materials through the use of grading and presentation software tools. Studies by Başaran and Köse (2013), Safranj (2015), Alharthi (2020) and Khadawardi (2022) claim that watching movies with subtitles can facilitate the acquisition of vocabulary and grammar. The learners also gain the ability to process speech faster, resulting in an increase in retention. Subtitles provide an authentic and dynamic language context from which the learners can comprehend the main ideas of the movie. In addition to engaging context, subtitles also help them to visualize content and perceive the correct pronunciation (Safranj, 2015). Moreover, exploiting the use of videos along with captions or subtitles is found to facilitate the ability of language learners to access a larger working memory capacity (Khadawardi, 2022). According to the reviews, learners should have clearly defined objectives, guided activities, and a suitable methodology when using movies or other sources for long-term learning benefits.

The evidence identified in the review has some limitations. The findings of some studies were not generalizable. A main feature of a good research methodology is that it should be replicable, whereas some studies do not elaborate much about their methodology properly. The absence of a needs analysis or assessment of the language proficiency levels of the participants before the intervention results in difficulties that learners will encounter with the material presented during the treatment (Aziz and Fathiyyaturrizqi, 2017). Educational theories that might contextualize the findings are not discussed in depth and critical discussion was not made on methodological differences of the included studies. The inference from a study is more supportive when the sample size is chosen pertinently. Hence the studies analyzed have some limitations, but their output is valuable to the field of English language teaching.

The systematic review and analysis of facilitating English language learning and teaching using movies are reviewed by two reviewers (the authors). The study has chosen five bibliographic databases and has reviewed only empirical, experimental, and quasi-experimental research. It is observed that there are no studies from the databases mentioned, focused on developing reading skills using movies as an auxiliary tool. Hence, further studies can be made on improving reading skills by adopting the multimodal approach.

Based on a comprehensive review of the current body of literature and empirical evidence, it can be inferred that the use of movies as a pedagogical tool for teaching the English language to ESL/EFL learners holds promise for enhancing their language proficiency. The utilization of movies within educational settings offers a promising avenue for instructors to deliver effective instruction while simultaneously guiding the learners towards a constructive and positive learning experience. Instructors must possess a high degree of proficiency in time management and demonstrate a comprehensive level of preparation. The present study highlighted several research gaps within the existing literature effectively. It is important to note that the studies included in this analysis predominantly center around empirical research.

Currently, there seems to be a lack of research on the theoretical foundations and conceptual frameworks for incorporating movies in ESL, EFL, ESP classrooms. More research is needed to understand how movies can effectively improve listening, speaking, reading, writing, vocabulary, pronunciation, grammar, and related skills. Additionally, there is an opportunity to explore the effectiveness of various technical and multimodal tools, such as artificial intelligence, augmented reality, virtual reality, gamification, mobile-assisted language learning tools, computer-assisted language learning tools, and social media-based language learning. Studying these tools can help analyze the academic possibilities in these areas, identify areas for improvement, and suggest effective strategies to enhance the teaching and learning of English language.

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

KP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. SG: Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review and editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

ANOVA, Analysis of Variance; CAR, Classroom Action Research; CARA, Classification and Rating Administration; CAW, Collaborative Attention Work; EFL, English as Foreign Language; ELT, English Language Teaching; ESFF, English Speaking Foreign Films; ESL, English as Second Language; ESP, English for Specific Purposes; G, General Audience; MCQ, Multiple Choice Question; MPA, The Motion Picture Association; NC-17, Adults only; PG, Parental Guidance; PG -13, Parents Strongly Cautioned; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses; R, Restricted; RQ 1 & 2 & 3, Research Question 1 & 2 & 3; SMMBLP, Social Media-Movie Based Learning Project; VIT, Vellore Institute of Technology.

Abdulrahman, S. A., and Kara, S. (2023). The effects of movie-enriched extensive reading on TOEFL IBT vocabulary expansion an TOEFL IBT SPEAKING SECTION SCORE. J. Qual. Res. Educ. 23, 176–197. doi: 10.14689/enad.33.913

Alharthi, T. (2020). Can adults learn vocabulary through watching subtitled movies? An experimental corpus-based approach. Int. J. English Lang. Lit. Stud. 9, 219–230. doi: 10.18488/journal.23.2020.93.219.230

Alsubaie, A., and Madini, A. A. (2018). The effect of using blogs to enhance the writing skill of English language learners at a Saudi University. Glob. J. Educ. Stud. 4:13. doi: 10.5296/gjes.v4i1.12224

Avallone, A. (2022). What are learner profiles? An educator’s guide for students. NGLC. Available online at: https://www.nextgenlearning.org/articles/getting-to-know-you-learner-profiles-for-personalization

Aziz, F., and Fathiyyaturrizqi, F. (2017). Using movie to improve students’ narrative writing skill. Adv. Soc. Sci. Educ. Hum. Res. 82, 207–210. doi: 10.2991/conaplin-16.2017.45

Başaran, H. and Köse. (2013). The effects of captioning on EFL learners’ listening comprehension. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 70, 702–708. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.01.112

Brown, S. (2010). Popular films in the EFL classroom: Study of methodology. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 3, 45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.011

Chapple, L., and Curtis, A. (2000). Content-based instruction in Hong Kong: Student responses to film. System 28, 419–433. doi: 10.1016/S0346-251X(00)00021-X

Cubillos, J. (2000). in Integrating technology into the foreign language curriculum, eds J. Bragger and D. Rice Branches (Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle Publishers).

Dikilitas, K., and Duvenci, A. (2009). Using popular movies in teaching oral skill. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 1, 168–172. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2009.01.031

Fisch, S. (2000). A capacity model of children’s comprehension of educational content on television. Media Psychol. 2, 63–92.

Goctu, R. (2017). Using movies in Efl classrooms. Eur. J. Lang. Lit. Stud. 8, 121–124. doi: 10.26417/ejls.v8i1.p121-124

GSI Teaching & Resource Center (2023). Classroom activities. Available online at: https://gsi.berkeley.edu/gsi-guide-contents/discussion-intro/activities/#:~:text=Research%20shows%20that%20when%20students,who%20 have%20diverse%20learning%20styles (accessed on June 6, 2023).

Haghverdi, H. (2015). The effect of song and movie on high school students language achievement in Dehdasht. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 192, 313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.06.045

Herrero, C. (2019). Using film in language teaching. A teachers’ toolkit for educators wanting to teach languages using film in the classroom, with a particular focus on Arabic, Mandarin, Italian and Urdu. Available online at: https://www.academia.edu/41423340/Using_Film_in_Language_Teaching_A_teachers_toolkit_for_educators_wanting_to_teach_languages_using_film_in_the_classroom_with_a_particular_focus_on_Arabic_Mandarin_Italian_and_Urdu.in (accessed June 6, 2023).

Hu, N., Li, S., Li, L., and Xu, H. (2022). The educational function of english children’s movies from the perspective of multiculturalism under deep learning and artificial intelligence. Front. Psychol. 12:759094. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.759094

Ismaili, M. (2013). The effectiveness of using movies in the EFL classroom – a study conducted at south east European university. Acad. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2:121. doi: 10.5901/ajis.2012.v2n4p121

Jusufi, J., and Jusufi, S. (2023). A case study on teaching english as a foreign language through movies to students of higher education. J. Hum. Res. Rehabil. 13, 287–291. doi: 10.21554/hrr.09231

Kanwal, S. (2023). Topic: Education in India: Statista. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/topics/6146/education-in-india/?kw=&crmtag=adwords&gclid=CjwKCAjwgqejBhBAEiwAuWHioGY-W8Ft_lw8KE0wDWRouLa7IY85ZgUa3C0tcf6mt_k8M32VaZwvbRoCmrYQAvD_BwE. (accessed May 22, 2023).

Khadawardi, H. (2022). Teaching L2 vocabulary through animated movie clips with english subtitles. Int. J. Appl. Ling. English Lit. 11, 18–27. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.11n.2p.18

Khoshniyat, A., and Dowlatabadi, H. (2014). Using conceptual metaphors manifested in disney movies to teach english idiomatic expressions to young Iranian EFL learners. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 98, 999–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.510

Kinasih, P., and Olivia, O. (2022). an analysis of using movies to enhance students’ public speaking skills in online class. J. Lang. Lang. Teach. 10:315. doi: 10.33394/jollt.v10i3.5435

Korieshkova, S., and Didenko, M. (2023). Using realistic movies as an attractive strategy for teaching maritime english. Pedagog. Pedag. 95, 108–121. doi: 10.53656/ped2023-5s.10

Kucukyilmaz, Y., Lokmacioglu, S., and Balidede, F. (2015). Military movies by hollywood: Assisting ELT in ESP Domain. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 199, 81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.490

Lee, S. (2019). Integrating entertainment and critical pedagogy for multicultural pre-service teachers: Film watching during the lecture hours of higher education. Intercult. Educ. 30, 107–125. doi: 10.1080/14675986.2018.1534430

Motion Picture Association of America (2020). Film ratings– motion picture association. Washington, DC: Motion Picture Association.

Muthmainnah, Obaid, A. J., Mahdawi, R. S., and Khalaf, H. A. (2022). Adoption social media-movie based learning project (SMMBL) to engage students’ online environment. Educ. Admin. Theory Pract. J. 28, 22–36. doi: 10.17762/kuey.v28i01.321

Nikoopour, J., and Farsani, M. A. (2011). English language teaching material development. J. Lang. Transl. 2, 1–12.

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2020). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021:89.

Rodriguez, I. L., and Moreno, E. M. G. (2009). Teaching idiomatic expressions to learners of EFL through a corpus based on disney movies. Interlinguistica 18, 240–253.

Safranj, J. (2015). Advancing listening comprehension through movies. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 191:513. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.513

Sert, O., and Amri, M. (2021). Learning potentials afforded by a film in task-based language classroom interactions. Modern Lang. J. 105, 126–141. doi: 10.1111/modl.12684

Tabatabaei, O., and Gahroei, F. (2011). The contribution of movie clips to idiom learning improvement of Iranian EFL learners. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 1, 990–1000. doi: 10.4304/tpls.1.8.990-1000

Tickoo, M. L. (2003). Teaching and learning english: A sourcebook for teachers and teacher-trainers. Hyderabad: Orient Black Swan.

Ward, J., and Lepeintre. (1996). The creative connection in movies and TV: What Degrassi high teach teachers. J. Lang. Learn. Teach. 58, 1995–1996.

Keywords: Endnote, Covidence, audio-visual multimodal aids, communicative competence, systematic review, Teaching Supplements

Citation: Pavithra K and Gandhimathi SNS (2024) A systematic review of empirical studies incorporating English movies as pedagogic aids in English language classroom. Front. Educ. 9:1383977. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1383977

Received: 13 February 2024; Accepted: 16 May 2024;

Published: 24 June 2024.

Edited by:

Gonzalo Daniel Sad, CONICET French-Argentine International Center for Information and Systems Sciences (CIFASIS), ArgentinaReviewed by:

Andry Sophocleous, University of Nicosia, CyprusCopyright © 2024 Pavithra and Gandhimathi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: S. N. S. Gandhimathi, Z2FuZGhpbWF0aGkuc25zQHZpdC5hYy5pbg==

†ORCID: K. Pavithra, orcid.org/0009-0000-7534-6434; S. N. S. Gandhimathi, orcid.org/0000-0003-0178-0902

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.