- 1General Practice Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 2Consent Labs, Ultimo, NSW, Australia

Introduction: Consent Labs is an Australian, youth-led, not-for-profit organization delivering comprehensive consent education. Workshops are co-designed by young people and delivered by near-to-peer facilitators in secondary and tertiary institutions. The aims of this paper are (1) to describe the development, design and delivery of Consent Labs and (2) to conduct a retrospective analysis of evaluation data collected by Consent Labs.

Methods: E-survey data were collected by workshop facilitators between March 2021 and April 2023. This paper presents a retrospective analysis of these de-identified data. Survey items included age, identity, pre- and post- sexual consent knowledge, attitudes towards the content and delivery and questions inviting free-text responses. Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics: frequencies, self-reported change in knowledge using paired t-tests, and differences between groups using chi-square tests. Free-text responses were analyzed using content analysis.

Results: We describe the conceptualization of Consent Labs, present information about topics covered and report on process evaluation data analysis. Six thousand and twenty-six students returned complete evaluation surveys; 76.3% were school students and 23.7% were university students. The majority (67.3%) identified as female, 24.2% as male, 1.7% as non-binary, 1.2% as other gender identity. Self-reported change in knowledge before and after workshops was significant (pre-workshop knowledge mean score 3.77; post-workshop knowledge mean score 4.58; p < 0.0001). Change in knowledge remained significant when analyzed by institution, school type gender and sexual identity. ‘Consent Foundations’ was the most frequently selected (41.0%) topic as being most valuable. Respondents selected ‘Recognizing Coercion’ and ‘Gaslighting and Other Consent Challenges’ most frequently for future workshops (both 48.3%). Analysis of free text responses provided additional feedback.

Discussion: Consent Labs has been gaining recognition nationally since it was first implemented; this is the first analysis of process evaluation data. Limitations of the study include the low response rate, self-reported change in knowledge and the cross-sectional nature of the evaluation. Preliminary findings are encouraging and provide a sound platform for quality improvement and further evaluation. A recent government grant to partner with education academics will ensure that the Consent Labs program and continuing growth will be informed by more rigorous evaluation and evidence.

1 Introduction

1.1 Comprehensive sexuality education

Comprehensive sexuality education (CSE)1 is defined by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as a curriculum-based process of teaching and learning about the cognitive, emotional, physical and social aspects of sexuality. It aims to equip children and young people with knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that will empower them to: realize their health, well-being and dignity; develop respectful social and sexual relationships; consider how their choices affect their own well-being and that of others; and, understand and ensure the protection of their rights throughout their lives (UNESCO, 2018, p. 16). Globally, it was the International Conference on Population Development (ICPD) in 1994 which ignited a call to action for the world’s adolescents and their sexual and reproductive health and rights, which included their right to CSE (Vanwesenbeeck, 2020). To mark the 25th anniversary of the ICPD, a global review of achievements, progress and opportunities for further strengthening of adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights highlighted that it is possible to ‘navigate [the] sensitivities to CSE’ and called for further support, capacity building and training for those delivering CSE (Plesons et al., 2019).

In addition to CSE being a fundamental right of all adolescents, there is overwhelming international evidence that curriculum-based CSE delivered in schools leads to positive health and wellbeing outcomes for young people. Earlier studies which evaluated CSE programs focused on health outcomes of unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) as well as their behavioral determinants, such as abstinence/ delaying intercourse, contraception and condom use and number of sexual partners (Kantor et al., 2021). A recent international systematic review expands the scope and definitions of the outcomes that CSE seeks to change (ibid). Additional outcomes reported in this review include more positive attitudes to healthy relationships, reductions in dating and intimate partner violence and greater recognition of gender equity and rights (Goldfarb and Lieberman, 2021).

UNESCO is the key global body which provides evidence, technical guidance and monitoring for CSE. In a 2019 Policy Paper, UNESCO presented a series of strategies for ‘breaking the deadlock in CSE delivery’ (UNESCO, 2019). Among these were recommendations to ensure that CSE curricula are relevant and evidence-based, to develop monitoring and evaluation mechanisms and to work with other sectors (especially health) and community organizations and groups, including parent groups (ibid). UNESCO (2022) published a technical brief on the evidence gaps and research needs in CSE, which included school-level studies on the best delivery methods. Among the delivery methods needing further research was the use of peer-to-peer approaches.

In Australia, momentum for curriculum-based sexuality education grew alongside global movements in the 1970s. This has been attributed to the sexual revolution of the 1960s and the advent of the first effective hormone contraceptive (‘the Pill’) and coincided with a global increase in teenage pregnancy in western countries (Mitchell et al., 2011). Further impetus arrived during the 1990s in response to the global HIV pandemic, whereby investment in research by the Commonwealth (national) government led to the establishment of national policy on guidelines for school-based education about HIV/AIDS, blood borne viruses and sexually transmitted infections (Weaver et al., 2005).

In the past two decades, global societal shifts in understanding and responding to the issue of sexual consent, sexual violence and harassment have led to a renewed focus on the role of CSE in violence prevention. The UNESCO technical guidance on CSE includes violence prevention, safety and consent as one of its eight key concepts in CSE (UNESCO, 2018). There are examples of violence prevention educational programs which have been piloted or implemented in UK, Europe and United States schools, with a general view that rigorous evaluation is lacking (Fox et al., 2014). In Australia, the Commonwealth government established an independent organization, Our Watch, in 2013, as part of a national plan to end violence against women and children. This included piloting and evaluating violence prevention education in schools, for example, in Victoria (Ollis, 2014); in Western Australia, the state government funds professional development programs on respectful relationships for teachers (Curtin University, 2023). Our Watch has published evidence-based resources for education providers (Our Watch, 2021), including a ‘Respectful Relationships Education’ toolkit (Our Watch, 2022).

Accompanying this growing awareness of gender-based violence and harassment and the need for sexual violence prevention, attention has turned in recent years to the tertiary education sector. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States published guidance for prevention of sexual violence on campus for college and university campuses in 2016 (Dills et al., 2016). A recent systematic review of published research on consent education, specifically, in education settings identified that most (15/18) took place in university or college settings, and most took place in the United States, which was attributed in part to the legislative requirement for US colleges to have sexual assault prevention programs (Burton et al., 2021). Evaluations of these consent education programs mostly measured change in knowledge, attitudes and confidence, rather than behavior (ibid).

1.2 The Australian context

In Australia, school education and delivery of curricula are the responsibility of state and territory governments. There is, however, a national curriculum covering all learning areas and subjects, developed to ensure a degree of equity and consistency across the country. Further, the national curriculum serves as a guide for states and territories to develop their own curriculum framework or syllabus (Mitchell et al., 2011). While sexuality education has always been part of a mandatory Health syllabus (‘Health and Physical Education’ being a key learning area in national and state/territory curricula), the coverage of relevant topics, delivery, teacher training and professional development and policy support vary considerably (Hendriks et al., 2023).

Five-yearly surveys have taken place, since 1992, among a national sample Australian secondary students to gain a snapshot of STI and HIV knowledge, current sexual practices including condom and contraception use, unwanted sex and experiences of school-based sexuality education. More recent iterations of the survey include questions about digital sexual practices such as sexting. The most recent (2021) survey included 6,841 respondents and found that 93.0% reported receiving some relationships and sexuality education at school and 95.6% reporting that they thought this was an important part of the school curriculum. Just over half the sample reported that respectful relationships and consent were well covered in their school sexuality education classes, while overall, less than 25% felt that their education was very or extremely relevant. In the same survey, just under 40% of respondents who had experienced any sex reported that they had ever had unwanted sex. This was significantly higher for young women than young men, and highest among trans and non-binary young people and also substantially higher than in previous surveys, where the prevalence varied from around 25 to 29% (Power et al., 2022). In the tertiary education sector in Australia, Universities Australia, the peak body for Australian universities, released a Good Practice Guide for preventing sexual harm in the university sector (Universities Australia, 2023). This followed a national survey among university students, conducted by the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) in 2015–2016 which reported that 51% of all university students were sexually harassed on at least one occasion and 6.9% of students were sexually assaulted, with a ‘significant proportion’ of these occurring on university campuses (AHRC, 2017). A more recent national survey among a national survey of 43,819 university students in Australia, 16.1% had experienced sexual harassment and 4.5% had experienced sexual assault, since starting university (Heywood et al., 2022). These statistics are echoed in studies in the United Kingdom and United States (Hill and Crofts, 2021).

To our knowledge, there have been no published papers or studies on consent education programs which have been entirely youth-led. The systematic reviews by Burton et al. (2021) and Goldfarb and Lieberman (2021) describe over 50 programs, none of which appear to be entirely youth-led and most of which are adult-led.

The aims of this paper are therefore (1) to describe the development, design and delivery of Consent Labs, a 100% youth-led consent and sexuality education program in Australia and (2) to evaluate the program based on student feedback of over 6,000 students who completed e-surveys between 2021 and 2023. This evaluation will provide a baseline for further improvements of the workshops and for designing a rigorous evaluation in the future.

2 The Consent Labs education program

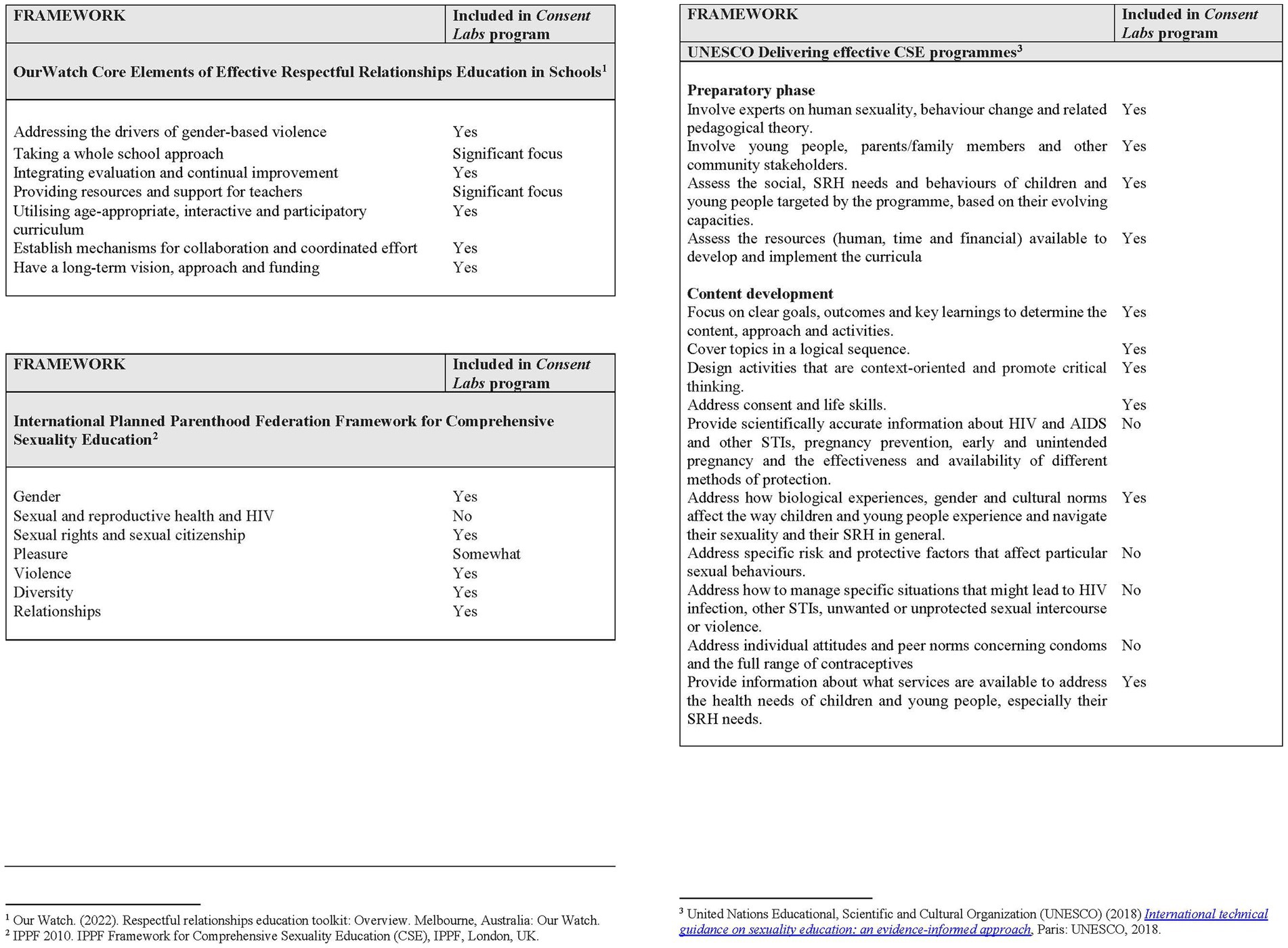

It is within the Australian landscape described above, that two young women (AW and JY) in Sydney, Australia initiated the development of an education program called Consent Labs in 2016. Their experiences of early undergraduate life brought to light an inadequacy in the school-based consent education they had received. AW and JY who were aged 19 years at the time, initially undertook extensive review of CSE frameworks, best practice principles and evidence. They familiarized themselves with the national curriculum and New South Wales (NSW) school syllabus relevant to CSE and consent education and identified and met with content, pedagogy and policy experts. Figure 1 outlines the Consent Labs program design mapped to one Australian and two international best practice frameworks.

AW and JY consulted closely with industry experts from a range of disciplines such as Health, Law and Education and initially developed four content areas, including Consent Foundations, Consent with Alcohol and Other Drugs, Recognizing Sexual Harassment and Assault and Responding to Sexual Harassment and Assault. The program is designed to be a sequential curriculum from Year 7 to 12, aligned with the formal school education curriculum, and extends into tertiary institutions. The first workshops were held in 2019 in tertiary institutions, and then subsequently delivered into secondary schools from 2021. They also deliver workshops for parents and careers, developed in 2021, and for educators, developed across 2021–2022. These additional programs were developed due to demand from schools to further engage with the topic, and to address best practice principles recommending a whole-of-school approach.

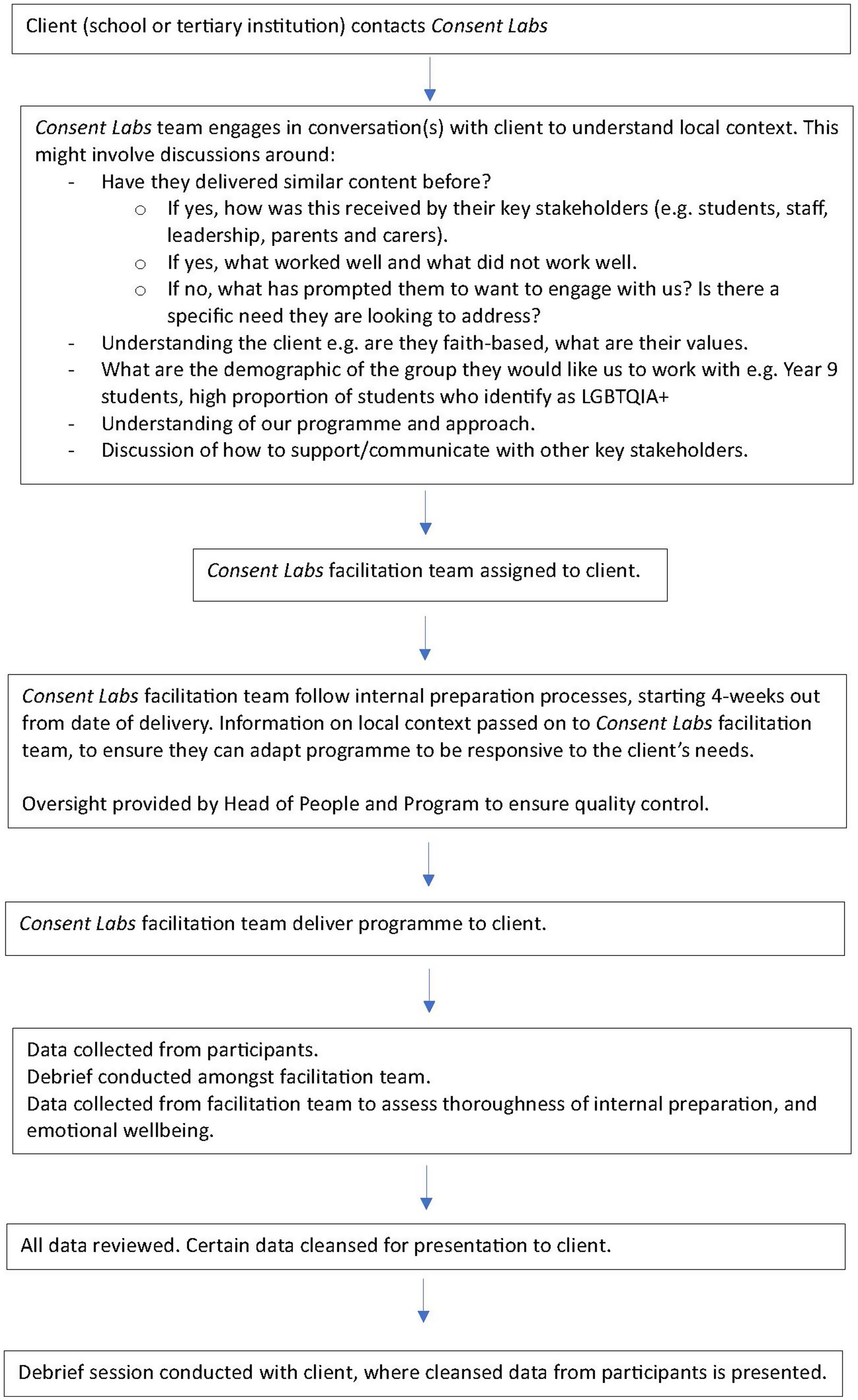

Consent Labs programs are delivered by trained volunteers who are all young people (under 30 years) and use a range of engaging educational methods such as scenario-based learning. Consent Labs educators initially consult with the school or tertiary institution to gain insight into existing consent and sexuality education teaching and to tailor their workshops to the student and institution needs. Figure 2 illustrates the process followed when Consent Labs receives requests from schools or tertiary institutions through to post-workshop feedback and debriefing. Schools and universities are charged a fee for the program. Consent Labs is promoted via a range of strategies, predominantly through word-of-mouth and through proactively building relationships with individual institutions.

Figure 2. Process followed by Consent Labs from initial contact with education provides through post-workshop feedback.

As of early 2024, Consent Labs has become an increasingly sought-after educational resource. It remains a youth-led, not-for-profit organization and registered charity that delivers comprehensive consent education programs to young people in high schools and tertiary institutions. The Consent Labs team has grown to 35 staff and the program has educated over 60,000 people across Australia. In July 2023, Consent Labs won a $1.1 million grant from the NSW Department of Communities and Justice to develop educational resources to address harmful gender and sexuality norms in schools at scale, in partnership with education academics at the University of Sydney (2023).

2.1 Consent Labs curriculum and framework

The UNESCO International technical guidance on sexuality education provides a framework for international best practice programs. This recommends that comprehensive sexuality education should be covered in an age-appropriate manner over several years using a spiral-curriculum approach to maximize learning (UNESCO, 2018). Accordingly, the Consent Labs program is deliberately designed and delivered as a spiral curriculum, spanning from Year 7 to Year 12 and beyond. It is also aligned with NSW Education Standards Authority (NESA) Primary and Secondary syllabus for Personal Development, Health and Physical Education (NESA, 2023) and is quality assured by the NSW Department of Education. Further, learners should “play an active role in organizing, piloting, implementing and improving the content of sexuality education” (UNESCO, 2018). Consent Labs actively seeks input and focus grouping from their audience to ensure they deliver education that is relevant and engaging to young people.

2.2 Consent Labs core program – content and delivery

The delivery of the content by near-to-peer facilitators is designed to be as engaging and student-led as possible. Two facilitators work with a group of students and deliver the program utilizing a range of strategies such as scenario-based learning, group work and discussion, and question and answer sessions. Facilitation skills are emphasized as much as curriculum content. That is, ensuring that facilitators know how to create rapport and buy-in from students within the first 5 min of being in the room (this is critical for true learning to be able to take place), understand how to manage the delivery of content within the time affords to ensure maximum competency, understand how to read the subtext within a room and respond accordingly, and most importantly how to deliver the program in a safe manner.

All students received ‘core’ modules, these are: Consent Foundations + Recognizing Sexual Harassment and Assault + Responding to Sexual Harassment and Assault. The topics covered are briefly described below. The remaining modules are optional and based on conversations with the school or tertiary institution regarding what is most important for their student cohorts.

Consent Foundations:

• What does everyday consent look like? How can we use skills that we have already been taught and apply them when exploring respectful relationships?

• Boundary setting in everyday scenarios, and in our relationships.

• Practising consent language.

Recognizing Sexual Harassment and Assault

• How can young people call out sexual harassment and contribute to societal change?

• How can young people develop the confidence to be able to identify when sexual harassment or assault has occurred?

• How can young people be an active bystander?

Responding to Sexual Harassment and Assault

• What can young people do should they find themselves or a friend in a situation where sexual harassment or assault has occurred? We cover responding to immediate danger and support available for both physical and mental health.

• What are the options for reporting sexual harassment and assault?

• How can young people be a supportive friend to someone who has experienced sexual harassment or assault?

3 Evaluation of Consent Labs - methods

3.1 Design

Retrospective quantitative and qualitative analyses of process evaluation e-survey data which were collected following student participation in Consent Labs workshops between March 2021 and April 2023.

3.2 Participants

Australian secondary and tertiary students.

3.3 Data Collection

E-surveys were developed using Google Forms. To optimize response rates, the e-survey items were kept brief and simple to answer. Survey items included age in years, identity (gender, sexual) using a drop down menu of fixed-choice responses which allowed for more than one selection, knowledge about sexual consent before and after the Consent Labs workshop measured using a 5-point Likert scale, content perceived as most valuable (using a drop down menu of fixed-choice responses which allowed for more than one selection), whether respondents learned relevant, practical skills (Yes/No) and whether the workshop was engaging (5-point Likert scale). Questions about cultural identity (including Aboriginal and / or Torres Strait Islander identity) were only included in some latter surveys, so these data were not analyzed. Questions inviting free-text responses included ways to improve the workshop and suggestions for future topics. Box 1 shows the wording of the e-survey items.

BOX 1. E-Survey items.

What is your age?

Response options for school students: 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18

Response options for university students: (a) Under 18, 18 – 20, 21-24, 25 – 30, 30+ OR (b) First year, second year, third year, fourth year, fifth year, other

How do you identify? (Tick all that apply)

Response options: Female, Male, Non-binary, Other gender, Straight/heterosexual, LGBTIQAP+, Prefer not to specify

Before this presentation, how much knowledge did you have about issues of consent?

Response options: 1 – 5 Likert scale (None – a lot)

After this presentation, how much knowledge do you have about issues of sexual consent?

Response options: 1 – 5 Likert scale (None – a lot)

Which modules did you find most valuable? (Tick all that apply)

Response options: Consent Foundations (Basics of Consent), Consent in the World of Technology, Healthy Relationships, Sex Education, Consent with Alcohol & Othe r Drugs, Recognising Sexual Harassment and Assault, Responding to Sexual harassment and Assault, Positive Masculinity

Do you feel like you learnt something practical you can incorporate into your day-to-day life (e.g. with friends, at home, at school, at parties)?

Response options: Yes, No

Please expand on what takeaways you found to be most valuable.

Response options: free text

Was the presentation engaging?

Response options: 1 to 5 Likert Scale (No - Yes)

Would you like to see us back for future workshops exploring more about sex and consent?

Response options: Yes, No

Which topics would you like to learn more about?

Response options: free text

Any ideas on how we can improve?

Response options: free text

Do you have any other comments?

Response options: free text

3.4 Data analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed in SPSS Version 28. Descriptive statistics included frequencies, individual students’ self-reported change in knowledge before and after the workshops using paired t-tests, and differences between groups (by demographic characteristics) using chi-square tests. We considered p-values of <0.05 to indicate statistical significance.

Free-text responses were analyzed using content analysis. An inductive approach was taken to coding the data, meaning that text was read without using any pre-determined categories or conceptual frameworks. Free-text responses were generally very brief and therefore the data did not lend itself to deep or iterative analysis (Leung and Chung, 2019). Nevertheless, codes were able to be organized into broader categories, reinforcing or providing additional understanding of the quantitative data.

Ethics approval was granted by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee [Project number 2023/604]. The Committee granted a waiver of consent for this study due to the anonymous nature of the data. A special condition of this approval was that no verbatim quotes from free text survey answers be used in dissemination of the findings, to mitigate any risk that individuals might be identifiable.

4 Evaluation findings

Between March 2021 and April 2023, 35,000 students from thirty-nine schools across New South Wales (NSW), Australian Capital Territory (ACT), Victoria, Queensland, Northern Territory and South Australia and fourteen universities/ university residential colleges across NSW, ACT, Victoria and Tasmania, participated in the Consent Labs program. Participating schools included single-sex and co-educational settings and were from Government, Independent and Catholic school sectors. Six thousand and twenty-six students (response rate ~17.3%) returned complete evaluation surveys. Of these, 1,761 surveys were completed between March and December 2021, 3,058 in 2022 and 1,234 from January to April 2023.

4.1 Institution and school type

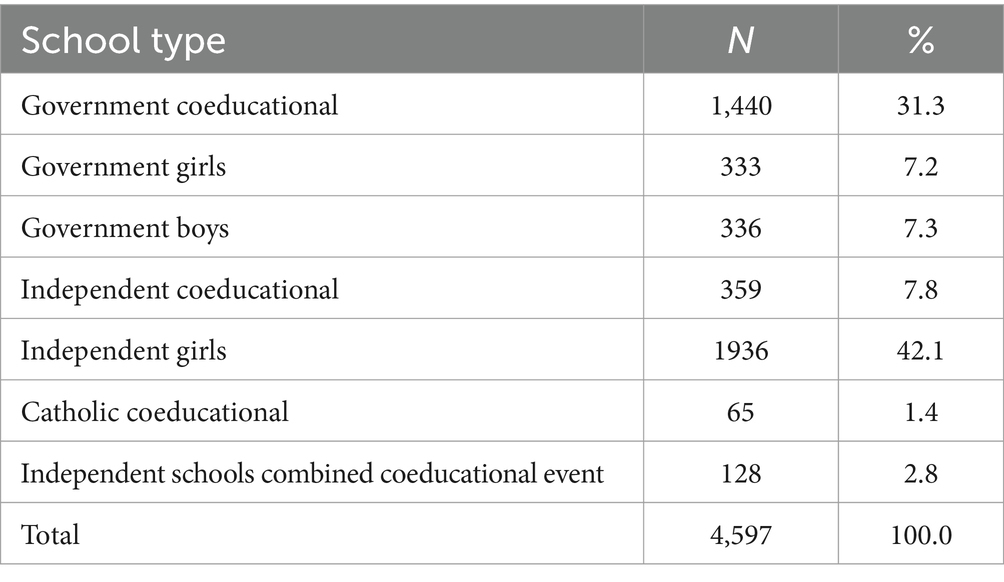

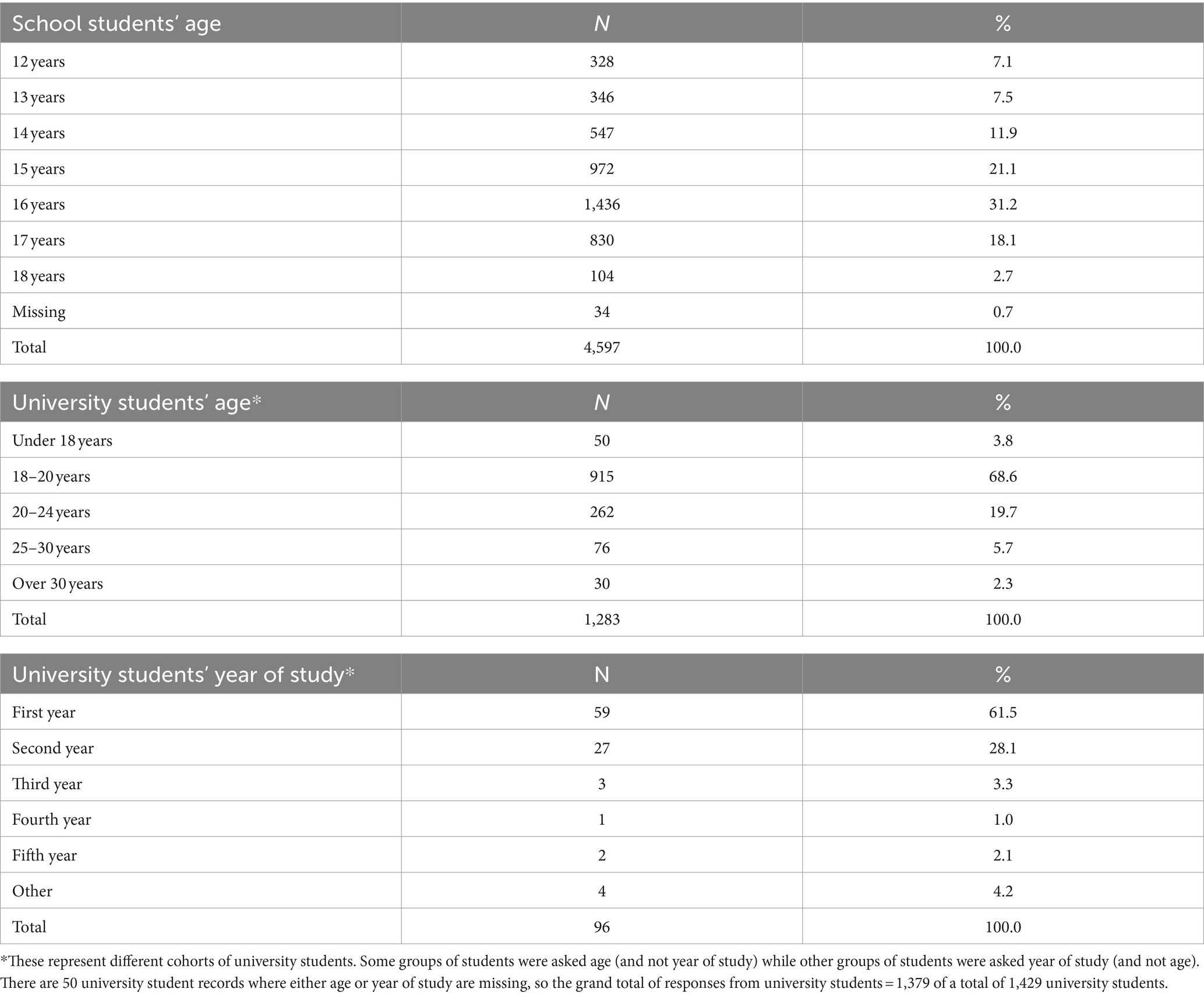

Of the 6,026 survey respondents, 4,597 (76.3%) were school students and 1,429 (23.7%) were university students. Most (80.7%) were from NSW.

The highest proportion of respondents by School Type were students from Independent Girls’ schools, See Table 1.

4.2 Age

Among school students, median age was 16.0 years (IQR = 2 years). Among university students, age was asked either according to an age group, or, in some surveys, students were asked to nominate the year of study rather than age. Among the former age category type, there were 1,333 respondents and 50 (3.8%) were aged under 18 years, 915 (68.6%) were aged 18–20 years, 262 (19.7%) were aged 20–24 years, 76 (5.7%) were aged 25–30 years and 30 (2.3%) were over 30 years. Among the latter age category type (n = 96), 59 (61.5%) were in first year, 27 (28.1%) were in second year, three (3.3%) were in third year, one (1.0%) was in fourth year, two (2.1%) were in fifth year and four (4.2%) nominated ‘other’. See Table 2.

4.3 Gender identity

The majority of respondents (67.3%) identified as female, 24.2% as male, 1.7% as non-binary, 1.2% as other gender identity. A further 1.3% selected ‘prefer not to say’; 1.7% were excluded as they selected all options and were considered ‘rogue’ responses, while 2.5% did not select any gender identity response.

Within every school type there was a small proportion of respondents (ranging from 1.4–7.1%) who were not cis-gender, in that they identified as either non-binary, gender diverse, or they attended a girls school and identified as male or attended a boys school and identified as female. Among university student respondents, 2.0% identified as non-binary or other gender/gender diverse.

4.4 Sexual identity

With regard to sexual identity, 59.7% did not select a response, 20.9% selected straight/ heterosexual, 14.6% selected LGBTIQA+, 3.1% selected prefer not to say and 1.8% were excluded as their responses were deemed ‘rogue’ (i.e., they selected all options). The proportions of school and university students who selected ‘LGBTIQA+’ were similar (15.1% cf. 13.9%). As with gender identity, respondents who identified as LGBTIQA+ were represented across all school types, the proportion ranging from 6.8 to 23.7%.

4.5 Self-reported change in knowledge

Change in knowledge before and after the Consent Labs workshops was significant (pre-workshop knowledge mean score 3.77; post-workshop knowledge mean score 4.58; paired samples test change in mean 0.814; one-sided p < 0.0001). Change in knowledge remained significant when analyzed by institution (school, university), school type, gender (female, male, non-binary, other gender identity) and sexual identity (straight/heterosexual; LGBTIQA+).

4.6 Workshop engagement and practicality

In response to the question ‘Was the presentation engaging?,’ 2,333 students (38.7%) checked ‘extremely’ and 2,273 (37.7%) checked ‘a lot’. 1,055 (17.5%) checked ‘moderately’, 246 (4.1%) ‘a little’ and 119 (2.0%) ‘not at all’.

The overwhelming majority (5,522/6026; 91.6%) indicated that they learnt something practical that they could incorporate into their day-to-day life. University students were more likely than School students to report that they learned something practical (97.2% cf. 89.9%; p < 0.001).

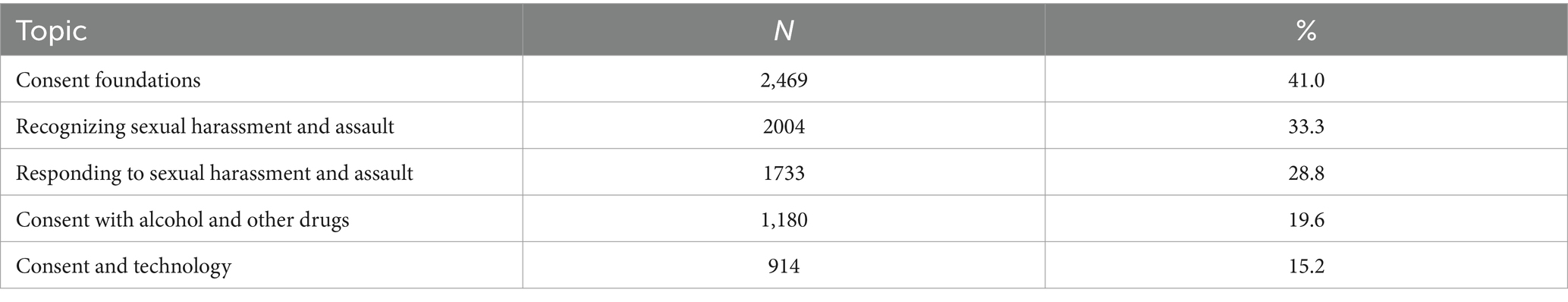

4.7 Most valuable workshop topics

Of the topics selected as most valuable following workshops, Consent Foundations was the most frequently selected, see Table 3. Most respondents selected one or two topics as being most valuable (46.8% selected one, 25.9% selected two). Topic selection by gender was analyzed by excluding the 5.5% of responses ‘prefer not to say’, rogue responses and where no gender identity response was selected. Respondents identifying as male were more likely to select Consent Foundations as the most valuable topic compared to females (males 44.5%, females 39.7%; p = 0.001) but not compared to non-binary or other gender diverse students.

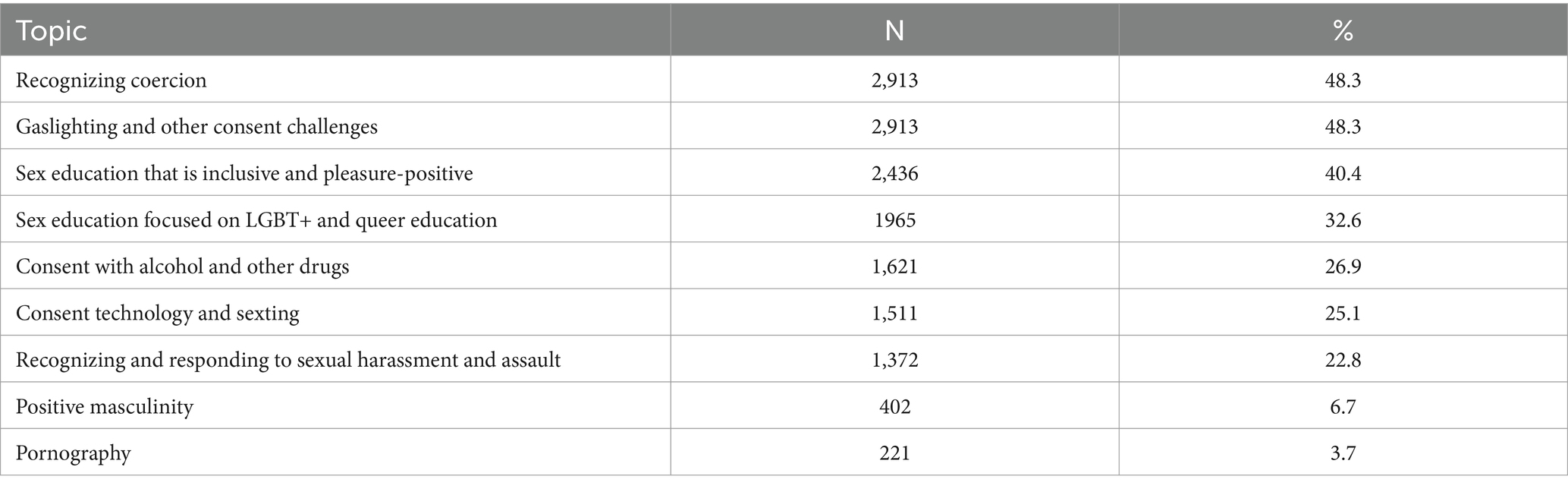

Respondents were given a list of up to nine other topics and asked to select which they would like to know more about in future workshops. Almost one-quarter (23.1%) selected two topics and 22.1% selected one topic. Table 4 displays the frequency of topics selected.

4.8 Free text responses

There were 360 free text responses when asked which aspects of the workshops they found most valuable or offered ‘key takeaways’. A breadth of topics was described, the following are responses which have been grouped together based on content.

• A deeper understanding of consent and its continuum, including legal definitions, what enthusiastic consent is, social media and consent and the role of power in consent dynamics.

• The importance of understanding and gaining clarity around personal boundaries, how to enact / communicate them and how they change

• Alcohol and its impact on capacity to consent and/ or set personal boundaries

• Understanding sexual harassment, recognizing sexual assault and knowing what to do including as a bystander

• Healthy and unhealthy relationships including gaslighting and love bombing

• Tips for dealing with an immediate threat or situation

Two thousand, two hundred and forty-eight respondents provided free text responses to the question ‘Any ideas on how we can improve?’ One-third (n = 756, 33.6%) responded that nothing needed to be improved, responses ranged from ‘no’ ‘nothing’ to indicating that the entire workshop was excellent or perfect. Among respondents with suggestions, most were about delivery methods, such as use of more videos, interactive activities, role plays, group discussion, music, games and icebreakers; some respondents suggested the workshops needed to be longer while others felt they should be shorter, others had suggestions for the spacing of interactive activities. Where there were suggestions for different or additional content, these included focusing more on issues for boys/men and being more inclusive or having more LGBTIQA+ content. There were also suggestions for more tips, practical strategies for dealing with sexual assault or discussing specific scenarios. Several respondents requested more time for answering questions, with some critical of there being an anonymous ‘question box’ but presenters not answering them (perhaps due to time constraints). Several respondents (from girls’ schools) recommended that workshops be delivered in boys’ schools. Some respondents commented that this content needed to be taught earlier, i.e., to younger students. A few commented that some of the content was not relevant because the respondent was not yet interested or involved in sexual relationships.

One thousand four hundred respondents provided Comments and Suggestions at the end of the survey. Around 820 respondents provided brief answers, such as ‘no further comments’, with many adding descriptors such as that the workshop was great, good, amazing, brilliant, engaging or simply wrote ‘thank you’. Remaining comments were also overwhelmingly positive, including high praise for the presenters and their energy/enthusiasm and the ability of presenters to tackle sensitive topics, being inclusive and for creating a safe and non-judgmental learning environment.

5 Discussion

Consent Labs is a curriculum-based, evidence-informed, youth-led and near-to-peer education program that has been gaining recognition since it was first implemented in 2019. The program was conceived of, developed, designed, delivered and thus far, evaluated, by young people and adheres closely to national and international best practice frameworks. The approach taken in designing the program, by the founders of Consent Labs, has been to consult with and tailor workshops to their clients’ needs. Consent Labs delivers a spiral curriculum in alignment with best practice by tailoring workshops to the age, stage and existing teaching occurring within schools. In schools, the program does not operate as a ‘one-off’ external provider ‘instead of’ but rather, as a complement and enhancement to the existing curriculum. External providers of curriculum, particularly in relation to sensitive topics or those requiring specific expertise, is both valuable for students as well as in supporting confidence and skills of teachers (Fox et al., 2014). Consent Labs has also commenced workshops for teachers following consultation with educators, supporting the evidence of need for professional development for teachers (Ollis, 2014). At universities, Consent Labs tailors workshops according to specific needs of the institution. In some cases (either in schools or universities) Consent Labs returns on two or more occasions to build upon previous education, again in accordance with specific needs. In light of new policy for mandatory consent education across Australia (Henebery, 2022), Consent Labs is a valuable resource.

There are some topics within CSE which are currently not explicitly covered by the Consent Labs program, these being contraception, pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections. Consent Labs made this decision intentionally because these topics are more commonly taught by teachers (Mitchell et al., 2011). In addition, they believed that consent and respectful relationships were more critical issues that were not being adequately taught in schools. They have piloted a ‘sexual health’ module within one university in Sydney and will look to expand their curriculum over the next 2 years. Consent Labs will also introduce pleasure as an explicit topic in the second half of 2024. Their workshops are designed to be inclusive in content and delivery (for example, use of gender-neutral language across all workshops) and they are currently developing specific workshops on gender and sexuality for delivery in late 2024.

The evaluation component of this paper analyzed process evaluation data from over 6,000 students from a range of participating schools and universities in several Australian states and territories. To our knowledge, this is the first published Australian study evaluating a youth-led consent education program. This retrospective analysis of process evaluation data describes the reach of the Consent Labs program to date, including most jurisdictions in Australia and most School Types. There has also been a steady increase each year in the number of workshops being delivered, reflected in the number of completed surveys.

Encouraging findings include the significant increase in self-reported pre- and post- workshop knowledge about consent, the very high proportion of respondents who learned something practical about consent that they could apply in their lives and the engaging nature of the workshops. Additional feedback provided in free text responses also highlighted content, delivery methods and the presenters themselves as engaging and enjoyable.

Published evaluations of sexuality education curricula or programs in Australia are scarce. In 2015 in Queensland, Australia, a peer-to-peer education model, R4Respect, aimed at preventing domestic violence, was initiated by a non-government community services agency, Youth and Family Service (YFS). The service historically has provided case management, accommodation services, community development and links to education and employment for young people (YFS, 2024). R4Respect trains youth ambassadors to deliver education sessions in local high schools. Evaluations of the program, conducted in partnership with a university in Queensland, have found overwhelming support for the peer-to-peer model and improved knowledge and understanding of harmful attitudes and behaviours. The evaluation also included perspectives of educators, who also expressed reservations that the program is not embedded in curriculum (Struthers et al., 2019). A community-consortium-led sexual health education program known as PASH (Positive Adolescent Sexual Health) has been running in Northern New South Wales since 2014 and delivers workshops and interactive activities to secondary school students aged 15 years and over. A qualitative study among PASH stakeholders (teachers, parents, staff, presenters, organizers and peer educators) found that program strengths include a safe and open learning environment, empowerment of young people and involvement of the support system and broader community (Crocker et al., 2019). A multiple, embedded case study evaluation is currently underway in Western Australia (Burns et al., 2019) and will collect, among other data, student perspectives on Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE) via surveys and focus groups. Given the paucity of published, rigorous evaluation in the Australian education context, it is important that programs such as Consent Labs seek funding and partnerships to conduct research and maintain relevance, quality and evidence of impact. The recent grant funding received by Consent Labs to partner with researchers to conduct more rigorous evaluation University of Sydney (2023) is thus an excellent development.

The majority of survey respondents did not answer the question about sexual identity. We propose two possible explanations (1) this could reflect that many young people are on a journey towards understanding their sexuality, alternatively they might not feel a need to define it (2) this question was optional to avoid students feeling forced to be labelled or ‘pigeon-holed’ and so the survey could be submitted without a response to this question. Further, recent research among adolescents suggests that there is an increasing acceptance and use among adolescents of non-traditional as well as intersecting identity labels and it is possible that the response options offered did not resonate with some respondents (Hammack et al., 2022).

It is interesting to note that the workshop ‘Consent Foundations’ was most frequently selected as the most valuable. We postulate that, while respectful communication has been historically taught in schools, there has been little to no teaching of “sexual consent.” The Consent Foundations workshop deliberately focuses on this, and so it is often seen as most valuable, as young people have never been taught it before, and it has gained recognition as an important topic in society recently. The majority of university students in the evaluation study were young, within the first or second year of their tertiary studies. We are therefore not surprised that these topics were rated highly by both school and tertiary institution students. We point out that there are no substantial differences in the overall content or ‘topic headlines’ in workshops between secondary and tertiary students. Goals always include engagement with activities and scenario-based learning. Facilitators will take cues from the audience to use examples and tailor content to make it the most age appropriate and relevant.

Of potential/ future workshop topics suggested, respondents selected Recognizing Coercion (48%), Gaslighting and Other Consent Challenges (48%) and Sex Education that is inclusive and pleasure positive (40%). We believe that the issues of coercion and gaslighting focus on the nuances around respectful communication and consent. In traditional teaching of ‘sex education’ and even respectful relationships, young people clearly feel there is not enough emphasis on being taught how to recognize these complex power dynamics. With regard to the third most frequently selected future topic of interest, inclusive and pleasure positive sexuality education has been one of the frequently repeated topics suggested by Australian secondary students. In the 7th National Survey of Secondary Students and Sexual Health, conducted throughout 2021, over 60% of respondents felt that respectful relationships and consent were well covered in RSE but commented on the need for more information about sex, pleasure and sexuality and gender diversity (Power et al., 2022).

Finally, the workshops from which our evaluation data are derived all took place after February 2021. This was a significant month in Australia, with three young women coming to national and international prominence: Grace Tame, named Australian of the Year on 25 January 2021 for her advocacy for survivors of sexual assault; Brittany Higgins, a young Liberal party staff member who alleged she was sexually assaulted at Australia’s Parliament House (Maiden, 2021) and Chanel Contos, who successfully petitioned for mandatory consent education in schools following several thousand testimonies from young women alleging they were sexually assaulted as teenagers by male peers (Chrysanthos, 2021). Thus, it might be anticipated that secondary students in Australia became more aware of, or were provided with, more formal consent education over the past two to 3 years. Consent Labs, while focused on consent, offers a range of workshops including healthy relationships and sex education that is ‘sex-positive’ and LGBTQIA+-inclusive. It seems likely that this positioning of consent education within a more holistic approach to relationships and sexuality education contributed to the high proportion of Consent Labs participants who found the content relevant, inclusive and practical.

Limitations of this study include the low response rate and underrepresentation of male and gender-diverse students among respondents, as well as the cross-sectional nature of the evaluation and reliance on self-reported change in knowledge. In addition, not all topics were offered across all workshops, so the most frequently selected topics only provide an indication of areas the students found most valuable. The survey items were developed by the Consent Labs team for immediate feedback and were not intended to have specific statistical or metric properties. Our analysis therefore can only be descriptive. Despite these limitations, these data are encouraging and provide a sound platform for further evaluation which should employ a longitudinal design, measure change in knowledge, attitudes and behavior and incorporate quantitative and qualitative program evaluation methods.

Additional future considerations for Consent Labs, and CSE more broadly, include considerations of cultural contexts. The UNESCO guidance makes clear that CSE programs are most effective when they are tailored to the cultural context in which they are delivered. This is particularly important in the case of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people who are typically sexually active from a younger age (Wand et al., 2018) and face a range of barriers accessing sexual health services (Wand et al., 2018; Bell et al., 2020). A qualitative study seeking perspectives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people about sex education found that participants preferred school sex education programs delivered by external specialists and wanted positive approaches to sex education, including how to gain consent before sex (Graham et al., 2023). In the Australian context, there is a need for further focus and investment into comprehensive sexuality programs that tailor to specific at-risk groups such as Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander, LGBTQIA+ and Culturally and Linguistically Diverse young people.

Consent Labs is a youth-led organization which centers the youth voice and works with content and education experts to design and deliver its programs for students, teachers and parents/careers. The organization seeks feedback from participants after each workshop as a mechanism for quality improvement and to ensure relevance to its varied audiences. The evidence presented in this paper while limited, is promising with regard to its acceptability and educational value. By expanding into more formal evaluation of its work, Consent Labs will also contribute to evidence for impact of consent and relationships education in the Australian education context.

Data availability statement

The datasets analyzed for this study are not publicly available for ethical reasons; the corresponding authors may be contacted if further information is required.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Human Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because Data were collected for process evaluation immediately following workshops and were not part of a research study, they did not identify respondents by name. The data curated for the purposes of this study were anonymous.

Author contributions

MK: Writing – original draft, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. AW: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Data curation, Conceptualization. JC: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Data curation, Conceptualization. JY: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the students who completed evaluation surveys. We also wish to acknowledge all students who have participated in Consent Labs workshops and teachers, parents and careers who have supported Consent Labs workshops. We thank Professor Andrew Hayen, Biostatistician, for his advice regarding statistical analyses and reporting of statistical information. We thank Ms Amanda Dinh for her assistance with data coding.

Conflict of interest

AW, JC, and JY are all Executive Directors of Consent Labs. AW and JY are co-founders of Consent Labs and AW is current CEO. MK is a member of the expert working group.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^‘Comprehensive sex education’ (CSE) is defined as a ‘curriculum-based process of teaching and learning about the cognitive, emotional, physical and social aspects of sexuality’ and is evidence-based, age and developmentally appropriate, incremental, curriculum-based and comprehensive (i.e., includes all aspects of sexuality, not just biology). (UNESCO, 2018). We are aware that there are several different terms used to describe CSE, for example ‘Relationships and Sexuality Education’, ‘Sexual Health and Relationships Education’ ‘Holistic Sexuality Education’ or simply ‘Sex Education’.

References

AHRC (2017). Change the course: National report on sexual assault and sexual harassment at Australian universities. Sydney: Australian Human Rights Commission.

Bell, S., Aggleton, P., Ward, J., Murray, W., Silver, B., Lockyer, A., et al. (2020). Young aboriginal people’s engagement with STI testing in the Northern Territory, Australia. BMC Public Health 20:459. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08565-0

Burns, S. K., Hendriks, J., Mayberry, L., Duncan, S., Lobo, R., and Pelliccione, L. (2019). Evaluation of the implementation of a relationship and sexuality education project in Western Australian schools: protocol of a multiple, embedded case study. BMJ Open 9:e026657. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026657

Burton, O., Rawstorne, P., Watchirs-Smith, L., Nathan, S., and Carter, A. (2021). Teaching sexual consent to young people in education settings: a narrative systematic review. Sex Educ. 23, 18–34. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2021.2018676

Chrysanthos, N. (2021). Hundreds of Sydney students claim they were sexually assaulted, Sydney Morning Herald. Nine.

Crocker, B. C. S., Pit, S. W., Hansen, V., John-Leader, F., and Wright, M. L. (2019). A positive approach to adolescent sexual health promotion: a qualitative evaluation of key stakeholder perceptions of the Australian positive adolescent sexual health (PASH) conference. BMC Public Health 19:681. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6993-9

Curtin University. (2023). The RSE project. Avaliable at: https://rseproject.org.au/ (Accessed February 15, 2024).

Dills, J., Fowler, D., and Payne, G. (2016). Sexual violence on campus: Strategies for prevention. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

Fox, C. L., Hale, R., and Gadd, D. (2014). Domestic abuse prevention education: listening to the views of young people. Sex Educ. 14, 28–41. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2013.816949

Goldfarb, E. S., and Lieberman, L. D. (2021). Three decades of research: the case for comprehensive sex education. J. Adolesc. Health 68, 13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.036

Graham, S., Martin, K., Gardner, K., Beadman, M., Doyle, M. F., Bolt, R., et al. (2023). Aboriginal young people’s perspectives and experiences of accessing sexual health services and sex education in Australia: a qualitative study. Glob. Public Health 18:1. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2023.2196561

Hammack, P. L., Hughes, S. D., Atwood, J. M., Cohen, E. M., and Clark, R. C. (2022). Gender and sexual identity in adolescence: a mixed-methods study of labeling in diverse community settings. J. Adolesc. Res. 37, 167–220. doi: 10.1177/07435584211000315

Hendriks, J., Marson, K., Walsh, J., Lawton, T., Saltis, H., and Burns, S. (2023). Support for school-based relationships and sexual health education: a national survey of Australian parents. Sex Educ. 24, 208–224. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2023.2169825

Henebery, B. (2022). All schools to teach consent education from 2023. Sydney: The Educator Australia.

Heywood, W., Myers, P., Powell, A., Meikle, G., and Nguyen, D. (2022). National Student Safety Survey: Report on the prevalence of sexual harassment and sexual assault among university students in 2021. Melbourne: The Social Research Centre.

Hill, K. M., and Crofts, M. (2021). Creating conversations about consent through an on-campus, curriculum embedded week of action. J. Furth. High. Educ. 45, 137–147. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2020.1751092

Kantor, L. M., Lindberg, L. D., Tashkandi, Y., Hirsch, J. S., and Santelli, J. S. (2021). Sex education: broadening the definition of relevant outcomes. J. Adolesc. Health 68, 7–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.09.031

Leung, D. Y., and Chung, B. P. M. (2019). “Content analysis: using critical realism to extend its utility” in Handbook of research methods in health social sciences. ed. P. L (Singapore: Springer), 827–841.

Maiden, S. (2021). Young staffer Brittany Higgins says she was raped at parliament house. Available at: https://www.news.com.au/national/politics/parliament-house-rocked-by-brittany-higgins-alleged-rape/news-story/fb02a5e95767ac306c51894fe2d63635 (Accessed 14 October 2023).

Mitchell, A., Smith, A., Carman, M., Schlichthorst, M., Walsh, J., and Pitts, M. (2011). ‘Sexuality education in Australia in 2011’. Monograph series no. 81, Melbourne: La Trobe The Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society’.

Ollis, D. (2014). The role of teachers in delivering education about respectful relationships: exploring teacher and student perspectives. Health Educ. Res. 29, 702–713. doi: 10.1093/her/cyu032

Our Watch (2021). Respectful relationships education in schools, evidence paper. Melbourne, Australia: Our Watch.

Our Watch (2022). Respectful relationships education toolkit: Overview. Melbourne, Australia: Our Watch.

Plesons, M., Cole, C. B., Hainsworth, G., Avila, R., Biaukula, K. V. E., Husain, S., et al. (2019). Forward, together: a collaborative path to comprehensive adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights in our time. J. Adolesc. Health 65, S51–S62. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.09.009

Power, J., Kauer, S., Fisher, C., Bellamy, R., and Bourne, A. (2022). The 7th National Survey of Australian secondary students and sexual health 2021’ (ARCSHS monograph series no. 133). Melbourne: the Australian research Centre in sex, health and society : La Trobe University.

Struthers, K., Parmenter, N., and Tilbury, C. (2019). Young people as agents of change in preventing violence against women. Available at: https://d2rn9gno7zhxqg.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/23032738/Struthers-et-al-2019-Research-Report-R4Respect.pdf (Accessed February 20, 2024).

UNESCO (2018). International technical guidance on sexuality education: an evidence-informed approach. Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO (2019). Facing the facts: The case for comprehensive sexuality education: Global education monitoring report, UNESCO, Paris. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000368231/PDF/368231eng.pdf.multi (Accessed February 8, 2024).

UNESCO (2022). Evidence gaps and research needs in comprehensive sexuality education: Technical brief. Paris: UNESCO.

Universities Australia (2023). Primary Prevention of Sexual harm in the University Sector Good Practice Guide. Available at: https://universitiesaustralia.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/PRIMARY-PREVENTION-OF-SEXUAL-HARM-IN-THE-UNIVERSITY-SECTOR.pdf (Accessed February 9, 2024).

University of Sydney (2023). Sexual consent education program wins $1.1 million research boost. Available at: https://www.sydney.edu.au/news-opinion/news/2023/07/31/sexual-consent-education-program-wins-1-million-research-boost.html (Accessed February 23, 2024).

Vanwesenbeeck, I. (2020). Comprehensive sexuality education. Oxford research encyclopedia of. Glob. Public Health. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.013.205

Wand, H., Bryant, J., Worth, H., Pitts, M., Kaldor, J. M., Delayney-Thiele, D., et al. (2018). Low education levels are associated with early age of sexual debut, drug use and risky sexual behaviors among young indigenous Australians. Sex. Health 15, 68–75. doi: 10.1071/SH17039

Weaver, H., Smith, G., and Kippax, S. (2005). School-based sex education policies and indicators of sexual health among young people: a comparison of the Netherlands, France, Australia and the United States. Sex Educ. 5, 171–188. doi: 10.1080/14681810500038889

YFS (2024). YFS. Available at: www.yfs.org.au (Accessed February, 2024).

Keywords: adolescents, youth, youth-led, consent education, sexuality education

Citation: Kang M, Wan A, Cooper J and Yu J (2024) Evaluating Consent Labs: prioritizing sexual wellbeing through a youth-led, curriculum-based education initiative. Front. Educ. 9:1362260. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1362260

Edited by:

Allison Carter, University of New South Wales, AustraliaReviewed by:

Kevin Davison, University of Galway, IrelandCatherine Maunsell, Dublin City University, Ireland

Copyright © 2024 Kang, Wan, Cooper and Yu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Melissa Kang, bWVsaXNzYS5rYW5nQHN5ZG5leS5lZHUuYXU=; Angelique Wan, YW5nZWxpcXVlQGNvbnNlbnRsYWJzLm9yZy5hdQ==

Melissa Kang

Melissa Kang Angelique Wan

Angelique Wan Julia Cooper2

Julia Cooper2