94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 17 April 2024

Sec. Teacher Education

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1360315

In this study, we examined the effects of teaching internships and related opportunities to learn, such as conducting lessons or reflecting on teaching practice, on the three facets of teacher noticing, perception, interpretation, and decision-making. Cross-lagged effects of these facets were examined to include reciprocal influences of the facets on each other and to facilitate insights into the development of teacher noticing and how its three facets can predict this development. In detail, this study addressed the research questions of whether and to what extent teacher noticing changes over the course of a teaching internship and how teaching internship process variables influence changes in teacher noticing skills. Based on a sample of 175 preservice teachers from six German universities, we studied professional noticing using a video-based pre- and posttest approach. The results indicated a significant improvement in all three facets of teacher noticing over the course of the internship with small effect sizes, and interpretation was a key facet in this development, having an autoregressive impact as well as influencing the development of perception and decision-making. Only some opportunities to learn within the teacher internship showed a significant impact on teacher noticing skills. For instance, connecting theory and practice and reflecting on practice seemed to foster teacher noticing skills, while the sole process of teaching had no effects on interpretation or decision-making, and even had a negative effect on perception. Overall, the study demonstrated the potential of teaching internships for the development of preservice teachers’ noticing skills and highlighted areas for improvement.

An important goal of the university-based phase of teacher education is to provide learning opportunities for preservice teachers (PSTs) so that they can acquire the knowledge and skills necessary for their professional school practice and, in particular, its core, sound teaching skill (Potari and Chapman, 2020). However, research suggests that PSTs often struggle to recognize their university learning as relevant to their future professional practice as teachers, and they thus demand more school practice and practice-oriented courses to alleviate the tension between theory and practice (Hascher, 2014; Ulrich et al., 2020). However, it may occur as risk that PSTs merely adopt established school practices without reflecting on them (Özgün-Koca and İlhan Şen, 2006; Chitpin et al., 2008; Ulrich et al., 2020). This risk can be mitigated by integrating practical activities into university studies via teaching internships1 and a strong focus on theory–practice linkage, that is, the establishment of links between theory and practice and the contextualization of theory in practice (König and Blömeke, 2012; Scholten and Orschulik, 2022).

Phases of school practice based on this premise are characterized by university educators providing institutionalized support for PSTs or specialized state-run teacher education institutions offering theory, knowledge, and guidance to accompany practical experiences of teaching, although the extent of this support varies (Lawson et al., 2015; Ulrich et al., 2020; Terhart, 2021). Classroom teaching as a core activity of this school practice involves, among others, perceiving classroom activities, attending to meaningful events, dealing with complex and challenging situations, and further processing and incorporating them into teaching practice (van Es and Sherin, 2002; Sherin et al., 2011). These skills are often conceptualized as teacher noticing, also referred to as professional vision2 (König et al., 2022b) and constitute a central, situation-specific facet of teachers’ competence that is more proximal to students’ learning processes and teachers’ performance in classroom situations than knowledge (Blömeke et al., 2022). To learn effective teaching and progress in their expertise development as teachers, PSTs must develop teacher noticing skills (Berliner, 1988; Fernandez and Choy, 2019; Bastian et al., 2022). However, the structure and characteristics of teachers’ noticing remain debatable among researchers, as different theoretical perspectives and research traditions have shaped the academic discourse on conceptualizations and the development of teacher noticing (Fernandez and Choy, 2019; Amador et al., 2021; Dindyal et al., 2021; König et al., 2022b). A cognitive–psychological perspective, which provided the theoretical foundation for this study, has been identified as the most influential perspective in the current discourse and is often used in standardized research on teacher noticing (König et al., 2022b; Weyers et al., 2023b). This perspective views teachers’ noticing as a set of cognitive processes that occur within individual teachers during classroom instruction (van Es and Sherin, 2002; Jacobs et al., 2010; Seidel and Stürmer, 2014).

In contrast, a sociocultural perspective emphasizes the social construction of professional vision (Goodwin, 1994), a discipline-specific approach introduced by Mason (2002) focuses on fostering individual teacher’s noticing, and an expertise-oriented perspective rooted in the expertise paradigm (Berliner, 1988; Stigler and Miller, 2018) investigates differences between novices’ and experts’ perceptions and interpretations, and the development of teachers’ noticing toward expertise. Emerging approaches place greater emphasis on the sociopolitical contexts and reciprocity of teacher noticing. For example, Louie et al. (2021) examined framing as an essential part of noticing in their FAIR framework, Scheiner (2021) highlighted the active, exploratory role of teachers in noticing and the reciprocal nature of perceivers and their environment with the embodied ecological approach, and Dominguez (2019) discussed noticing as a reciprocal process between teachers and students.

Despite these different perspectives on the construct, PST’s noticing skills are generally expected to develop through school practice as part of teaching internships in initial teacher education and to indicate change over the course of teaching internships, since these skills are deemed to mediate between PSTs’ dispositions and performance, and thus also to link theory to practice (Blömeke et al., 2015a; Mertens and Gräsel, 2018).

However, despite the fact that teaching internships are the most expensive and organizationally challenging components of initial teacher education, empirical evidence on the effects of teaching internships in general and particularly on teacher noticing is somewhat limited and often based on datasets drawn from single universities. Furthermore, most relevant studies have only examined PSTs’ self-assessments of their competencies (König and Rothland, 2018). Thus, to date, findings on the impact of teaching internships on PSTs’ development have rarely employed standardized, longitudinal measures of competencies going beyond the own institution (Lawson et al., 2015; Ulrich et al., 2020). Moreover, the development of teacher noticing skills and, in particular, the effects of process variables, such as opportunities to learn during internships, on teacher noticing have scarcely been investigated (Ulrich et al., 2020). In general, data from longitudinal pretest–posttest studies on the development of teachers’ noticing skills are limited (König et al., 2022b; Weyers et al., 2023b), although they are needed to explore connections among the development of the facets of teachers’ noticing (perception, interpretation, and decision-making) and how they support each other over time, particularly over the course of teaching internships (Superfine et al., 2017; Thomas et al., 2021).

In this study, we aimed to address these research gaps concerning teaching internship by analyzing German secondary PSTs’ pre- and posttest results based on an established and standardized video-based measurement instrument for teacher noticing from a general pedagogical and mathematics pedagogical perspective, administered before and after their teaching internships, and relating them to the characteristics of the individual internship experiences of the PSTs. Specifically, we examined the reciprocal effects of the facets of teacher noticing (research question 1), changes in PSTs’ noticing skills (research question 2), and the influences of opportunities to learn on these changes (research question 3) over the course of the teaching internship at six German universities. In doing so, we provide new empirical insight into school experiences in initial teacher education that are an essential part of teacher education worldwide (Cohen et al., 2013; Lawson et al., 2015; Cabaroğlu and Öz, 2023), and empirical evidence on the extent to which teaching internships can promote teacher noticing skills as a core component of teacher competence.

In this section, we present the current state of the art research on teacher noticing and describe our own conceptualization. We then summarize relevant research on the effects of teaching internships in general and on teacher noticing in particular. Finally, we describe our research questions.

Major research themes in teacher noticing include, in particular, mathematics and mathematics pedagogical topics such as students’ mathematical thinking (Jacobs et al., 2010) or ways of dealing with representations (Dreher and Kuntze, 2015), and general pedagogical topics, such as classroom management (Gold and Holodynski, 2017; Weber et al., 2018). Recent studies exploring teachers’ noticing have considered dealing with heterogeneity (Keppens et al., 2021) and sociopolitical dimensions, such as ethnicity or socioeconomic background (Shah and Coles, 2020; Louie et al., 2021), as well as strength-oriented noticing (Scheiner, 2023).

Based on a cognitive–psychological approach, teacher noticing is widely understood as paying attention to or perceiving classroom events, interpreting these events, and—in some conceptualizations—employing decision-making processes to act/react based on the interpretations (Sherin et al., 2011; Dindyal et al., 2021; König et al., 2022b). For example, Jacobs et al. (2010) focused in their seminal work on children’s mathematical understanding, distinguishing three facets of teachers’ noticing: attending to children’s mathematical strategies, interpreting their understanding, and deciding how to respond. Although the facets of teachers’ noticing support each other and may give the impression that noticing in the classroom is a linear or even chronological process (van Es, 2011), from a theoretical perspective, they are understood as deeply “interrelated and cyclical” (Sherin et al., 2011, p. 5), operating through complex interactions (Kaiser et al., 2015; Santagata and Yeh, 2016; Thomas et al., 2021). This circular modeling of in-the-moment teachers’ noticing is often expressed as perception ↔ interpretation ↔ decision-making (Santagata and Yeh, 2016; Thomas et al., 2021).

However, little empirical attention has been paid to these relationships and their nature, despite knowledge of them being crucial for comprehending teachers’ noticing and its effects in the classroom (Thomas et al., 2021). Some studies have claimed that perception and interpretation, and interpretation and decision-making, are more closely related than perception and decision-making, providing some insight into the internal structure of the construct teacher noticing (Thomas et al., 2021; Bastian et al., 2022), but less is known about the development of the facets’ relationships over time and how they influence and change each other. This deficiency may be explained by the lack of quantitative pretest–posttest studies on teacher noticing (König et al., 2022b).

One exception is a study by Jong et al. (2021), who examined changes in PSTs’ noticing skills over the course of one semester. They reported a significant effect of perception at Time 1 (T1) on perception at Time 2 (T2, ) and similar results for interpretation (), but no such association between decision-making at T1 and T2. In addition, only one cross-lagged path was significant (the one from interpretation at T1 to perception at T2 [), indicating an effect of interpretation on perceptual skills. These results were consistent with a study by Superfine et al. (2017), which demonstrated that it may be better to foster interpretation skills before perceptual skills. In our study, we further analyzed the cross-lagged, reciprocal effects of the three facets of teacher noticing to provide a clearer picture of their relationships.

Competence can be conceptualized as a set of cognitive skills and abilities needed to successfully cope with the demands of professional situations, including the motivational, volitional, and social willingness to apply them (Weinert, 2001). Following this conceptualization, competence research at first particularly focused on cognitive dispositions of teacher such as their professional knowledge (Kunter et al., 2013). To consider the situation-specificity of competence, conceptualizations have been further developed in recent years based on complementary components, such as teacher noticing (Kaiser et al., 2017; Metsäpelto et al., 2021). For example, Blömeke et al. (2015a) conceptualized competence as a continuum between dispositions (e.g., knowledge) and actual classroom performance, and they included perceiving, interpreting, and decision-making as mediating skills to emphasize the situation-specific aspects of competence. These skills, which we describe as teacher noticing, contextualize knowledge and affects and link them to teachers’ actual performance. Thus, they also connect theory learned in initial teacher education to practice in the classroom.

The TEDS-M research program includes situation-specific skills in the measurement of teachers’ professional competencies by incorporating teacher noticing as an integral part in the competence framework since the TEDS-Follow-Up (TEDS-FU) study (Kaiser et al., 2017). Based on the model by Blömeke et al. (2015a), we conceptualize teacher noticing as consisting of three facets: (1) perception of specific classroom events, (2) interpretation of the perceived events, and (3) decision-making, that is, the preparation of responses to student actions or alternative instructional strategies (Kaiser et al., 2015). This can be classified as an analytical and cognitive–psychological conceptualization of teacher noticing (König et al., 2022b). A cognitive-psychological approach was chosen to model and measure the cognitive processes involved in teacher noticing and to compare the skills of groups of teachers as well as the development of individual teachers over time (König et al., 2022b). The approach allows for a standardized and feasible operationalization of the noticing facets and is thus commonly applied in the psychometric measurement of teacher noticing (Weyers et al., 2023b).

Based on studies from the expertise research (Berliner, 1988; Stigler and Miller, 2018), the first facet of teacher noticing in our conceptualization involves perceptual processes with no or only minimal interpretation (Bastian et al., 2022), encompassing the observation of clearly discernable incidents that happen in classroom. The second facet, interpretation, involves the analysis of observed events based on an individual’s knowledge, experiences, and beliefs, excluding the consideration of instructional responses to these events. This, in turn, is part of the third facet of teacher noticing that includes the development of possible continuations of the lesson, responses to student behavior, and alternative approaches to observed teacher actions (Yang et al., 2021). At the content level, our conceptualization, used in this study, does not focus only on one topic, such as children’s mathematical understanding, but encompasses a broad field of classroom situations and features that are relevant to high-quality mathematics education from general and mathematics pedagogical perspectives, such as perceiving effective classroom management, analyzing the use of different representations, interpreting students’ mathematical thinking, or making decisions about teaching and learning processes (Kaiser et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2021).

Over the past 20 years, a growing body of research has considered teaching internships and their impact on all stakeholders, particularly PSTs (see reviews by Lawson et al., 2015; Ulrich et al., 2020). Early studies revealed the crucial role of teaching internships in the self-perceived personal and professional development of PSTs (e.g., Caires and Almeida, 2005), and more recent literature has demonstrated the positive impact of teaching internships on the beliefs, self-efficacy, and motivation of PSTs (Ng et al., 2010; Seifert and Schaper, 2018; García-Lázaro et al., 2022). Mentors foster the development of their mentees and play a crucial role in how PSTs use and perceive their teaching internships (Hudson and Millwater, 2008; König et al., 2018b; Festner et al., 2020; García-Lázaro et al., 2022). In addition, research has suggested that professional competencies, which, in this context, are often distinguished as teaching, educating, assessing, and innovating, are expanded during teaching internships (Gröschner et al., 2013; Seifert et al., 2018).

However, these studies have usually been based solely on PSTs’ self-assessments of their own competencies and have not applied objective tests to measure PSTs’ professional competencies (Ulrich et al., 2020). Consequently, evidence of competence gains is limited, although there are some exceptions. Recent studies within the Learning to Practice project have used knowledge tests to assess PSTs’ general pedagogical knowledge, have combined and linked these with self-assessment measures, and demonstrated improvements in complex decision-related knowledge among student teachers from three different universities. Reflection and theory–practice links were shown to facilitate this improvement (König et al., 2018a). Furthermore, the incorporation of reflection activities and the establishment of links between theoretical concepts and school practice have the potential to enhance knowledge development, as shown by Schlag and Glock (2019). They conducted an analysis of classroom management knowledge using standardized tests and highlighted the significance of practice activities in the acquisition of classroom management knowledge. In summary, although teaching internships have been examined in several studies, research gaps remain regarding the investigation of teachers’ competence development using standardized measures (Ulrich et al., 2020).

To date, situation-specific facets of competence, such as teacher noticing, have scarcely been investigated in the teaching internship context (Ulrich et al., 2020). However, in a more general context, comparisons between teachers with different durations of experience have emphasized the critical role of teaching experiences in the development of teachers’ noticing (e.g., Jacobs et al., 2010; Gold and Holodynski, 2017; Yang et al., 2021; Bastian et al., 2022). In these studies, PSTs performed worse than in-service teachers on standardized tests of teachers’ noticing (Bastian et al., 2022). Thus, practical experiences in schools (e.g., teaching internships) should facilitate the development of PSTs’ teacher noticing. This hypothesis was confirmed in a study by Stürmer et al. (2013), who investigated a five-month teaching internship at a German university, focusing on perceptual and interpretive facets of teachers’ general pedagogical noticing conceptualized as professional vision. They demonstrated increases (η2 = 0.09, corresponding to an effect size of d = 0.63; Lenhard and Lenhard, 2016-2022) in both facets using the video-based test Observer (Seidel and Stürmer, 2014).

These findings were replicated by Mertens and Gräsel (2018) for a holistic understanding of professional vision, which included perceptual and interpretive aspects, based on five-month teaching internships via another university. The increase in teachers’ noticing skills had a large effect size (d = 0.79) and was validated using a control group (Mertens et al., 2018; Mertens and Gräsel, 2018). Further evidence suggests that teaching internships benefit PSTs with weak teacher noticing skills, helping them to develop these skills (Stürmer et al., 2013; Orschulik, 2020).

In a similar study exploring the effects of two short-term (seven-week) practical activities at a German university, Weber et al. (2018) reported no significant development in the classroom management and general pedagogical knowledge-related facets of holistic professional vision for PSTs who participated in the practical activities without accompanying institutionalized reflection and feedback. In contrast, a group of PSTs who received peer and expert feedback on their videotaped lessons and gave feedback themselves significantly improved their skills, with a large effect size of d = 1.10 (Weber et al., 2018). Focused accompanying intervention to link theory and practice seems to support the development of teachers’ noticing skills (Stürmer et al., 2013; Scholten and Orschulik, 2022).

However, until now the development of decision-making skills during teaching internships has not been investigated, and subject-specific insights in the noticing of mathematics teachers are lacking. Moreover, the influence of process variables (i.e., PSTs’ individual teaching experiences and opportunities to learn within the internship) on the development of teacher noticing has not been examined before but are needed to assess benefits of teaching internships as an important part of initial teacher education and to provide first explanations for the development. Overall, previous results have been based solely on data collected at single universities, thus limiting their generalizability. Our study addressed this broad research gap.

Based on current state-of-the-art research and the accompanying research desiderata, we aimed to investigate the reciprocal influences of the facets of teachers’ noticing over the course of teaching internships and the influences of teaching internships and their process variables on the development of PSTs’ teacher noticing. Therefore, we considered the following research questions:

1. To what extent do the facets of teachers’ noticing at the beginning of teaching internships condition change over the course of the internships, considering autoregressive and cross-lagged effects?

2. To what extent do teaching internships affect changes in teachers’ noticing skills?

3. To what extent do certain teaching internship process variables (i.e., learning time, teaching practice activities, and mentor support) influence teachers’ noticing skills?

In this section, we briefly introduce teacher education in Germany and describe the characteristics of teaching internships to place the study in its context, to facilitate the understanding of our research design, methodology, and findings, and to enable researchers to connect our findings to the practical experiences in teacher education in their countries, as teaching internships have been identified as a crucial part of teacher education worldwide (Cohen et al., 2013; Lawson et al., 2015; Cabaroğlu and Öz, 2023).

In general, teacher education in Germany consists of three main phases, the first two constitute initial teacher education: (1) higher education at universities and pedagogical universities, (2) practical teacher training (known as preparatory service or induction) through specific state-based teacher seminars, and (3) elective professional development courses, which accompany professional practice as an in-service teacher following the first two phases of teacher education (Drahmann, 2020; Eckhardt, 2021).

In Germany, the exact design and organization of teacher education depends on the federal state (Bundesland) in which it is conducted, although shared norms and principles exist (Cortina and Thames, 2013). Several different types of schooling have been implemented for German secondary education (the focus of this paper): teaching at academic-track schools (Gymnasium), teaching at non-academic track schools, teaching at intermediate forms which combine academic and non-academic track education, teaching at vocational schools and special needs teaching (Cortina and Thames, 2013; Drahmann, 2020). For each type, PSTs must study two school subjects, with the exception of special needs education. University study is divided into four areas: subject matter, subject-related pedagogy, general pedagogy, and practical activities in school (Drahmann, 2020).

Due to the identified gap between theory and practice in teaching and teacher education (König and Rothland, 2018), connecting these practical activities with academic opportunities to learn has become increasingly important recently. Hence, school practical studies have been reorganized and reshaped in the wake of the Bologna reforms, that is, the transformation from a traditional state examination system to a bachelor-master-system comparable within Europe (Schubarth et al., 2012; Drahmann, 2020; Terhart, 2021). They are usually spread over several semesters of university teacher education depending on the federal state and aim to achieve several goals: professional orientation, competence improvement by linking theory and practice, and the development of teaching abilities (König, 2019).

In all federal states, PSTs undertake some extensive, long-term (i.e., lasting several months) practical activities in schools in the master’s phase of their university teacher education to link theory with practice, which is often referred to as a teaching internship or (long-term) teaching practicum (Gröschner et al., 2015; Ulrich et al., 2020) and is, again, the focus of this paper. During their teaching internships, PSTs attend a school of their teaching type and participate in almost all aspects of daily school life. In particular, they are required to observe a certain number of lessons taught by in-service teachers and to teach lessons themselves under supervision. Mentors (i.e., in-service teachers at the school) support the PSTs in practical matters during their internships, while teacher educators from the university, and in some federal states, from the state-run teacher training seminars of the second phase of teacher education, facilitate the theory–practice linkage.

To address the aforementioned lack of studies based on multiple universities, the sample consisted of 175 secondary mathematics education PSTs from six universities (Hamburg, Cologne, Münster, Paderborn, Vechta, and Würzburg) in four German federal states who participated in an online survey before and after their (long-term) teaching internships between spring 2019 and fall 2021. At T1, 313 PSTs participated in the survey. The panel sample decreased with a panel attrition of 44% due to lack of participation at T2. Since the process variable data were collected at T2, these individuals were missing not only the T2 ability scores but also important predictor variables and were therefore excluded from the final panel sample. Data imputation was not possible because the missing predictor variables would have led to a circular process. Teaching internships were conducted at the master’s level for all universities except Würzburg. Since initial teacher education in Bavaria is organized as a state examination with no division between bachelor’s and master’s programs, PSTs from Würzburg participated in the survey during their 5th or 6th semesters of study. The demographic sample statistics are presented in Table 1.

Deploying a pretest–posttest design, we administered a survey to the participants via an online platform before their teaching internships (at T1) and after they completed their internships (at T2) in the frame of the TEDS-Validate-Transfer research project. Each questionnaire took approximately 90 min to complete. At T1, we obtained demographic data and measured teachers’ noticing using a video-based instrument. At T2, the latter measure was repeated and supplemented with an assessment of process variables related to teaching internships: learning time, teaching practice activities, and mentor support. PSTs received a small financial reward for their participation. Data were collected and processed according to the requirements of the General Data Protection Regulation.

We employed an established instrument developed in the TEDS-FU study to measure teachers’ noticing (Kaiser et al., 2015). It comprised three scripted (i.e., staged) video-vignettes, which ranged in length from 2.25 to 3.5 min and were presented in random order. The vignettes represented 9th to 10th grade lessons and covered a range of mathematical topics (e.g., surface and volume calculations, functions, and modeling) and teaching phases, such as introducing a mathematical task, working on it, and conducting a class discussion of the results (Kaiser et al., 2015). Prior to watching each video-vignette, the PSTs were provided with background information about the depicted class, pedagogical remarks, and the mathematical content to be addressed. They then viewed the corresponding video-vignette once and were asked to respond to 77 open-response and Likert-type rating-scale items that assessed their teacher noticing skills in perception (n = 24), interpretation (n = 41) or decision-making (n = 11) with either a mathematics pedagogical or general pedagogical focus.

The use of Likert scales, which is a widely used approach to measuring teacher noticing (Keppens et al., 2021; Weyers et al., 2023b) and have already been used to evaluate teaching internships (Mertens and Gräsel, 2018), enabled a timesaving but accurate assessment of teachers’ perceptions, interpretations, and decisions regarding distinct incidents. They were complemented by open-response items that allowed for the testing of more complex situations. The use of scripted video-vignettes and permitting only one-time access allowed for manageable and cognitively activating measurements that were strongly related to the classroom environment and realistic instructional situations (Piwowar et al., 2018; Santagata et al., 2021).

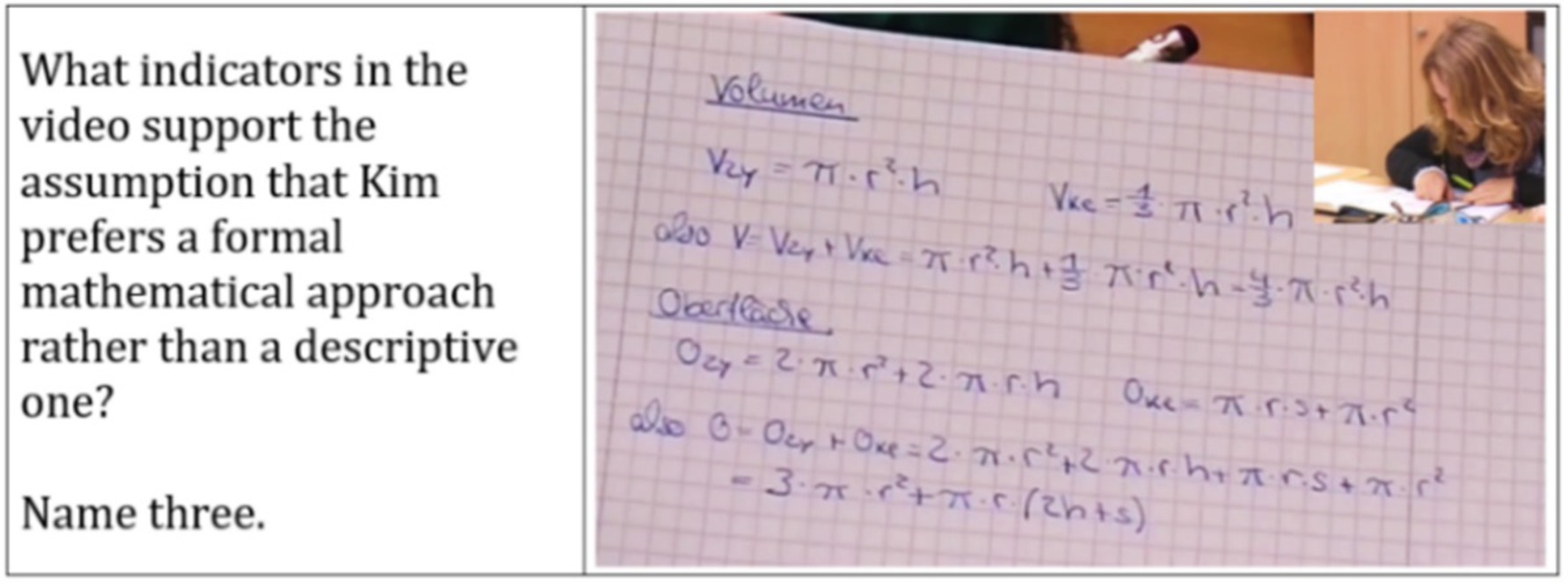

The rating-scale items comprised a statement and a four-point Likert response scale for assessing it. The example item in Figure 1 was used to assess the perception of a specific classroom event. The interpretation item in Figure 2, related to the mathematics pedagogical perspective, asked the participants to analyze a student’s solutions to volume and surface calculations and to name indicators that support the hypothesis of the student’s preference for formal mathematical approaches. The decision-making item in Figure 3 regarding general pedagogy and inclusive education asked about dealing with class heterogeneity and possible changes in the course of instruction to better address this heterogeneity.

Figure 2. Open-response item for the interpretation facet from a mathematics pedagogical perspective.

All items were scored dichotomously as correct (1) or incorrect (0), with the exception of five open-response partial-credit items coded 0 to 2 or 0 to 3. To evaluate the quality of the instrument and determine the correct and incorrect answers for the rating scale items, expert reviews were conducted during the development of the instrument (see Hoth et al., 2016, for details). Based on theoretical considerations and expert judgments, we created a detailed coding manual for scoring the open-response items. It consisted of comprehensive descriptions and multiple anchor examples to clarify the correct responses. The instrument’s reliability was assessed using Cohen’s kappa (Cohen, 1960) and double-coding for 20% of the responses to investigate intercoder agreement for each item. The resulting values (κmean = 0.80, κmin = 0.47, κmax = 1.00) indicated good overall intercoder reliability. We excluded five items with poor intercoder reliability due to a low frequency of correct responses. These items were discussed in detail by the raters and then coded by consensus.

The validity of the measurement instrument was examined through extensive workshops with experts in mathematics pedagogy and general pedagogy, focusing on the authenticity of the portrayed classroom situations and the adequacy of the test items, as well as curricular analyses of the content (Kaiser et al., 2015). In addition, we ensured the independence of the measurement from the video-vignettes and, thus, the measurement of the underlying construct (Blömeke et al., 2015b). A study by Weyers et al. (2023a) confirmed the suitability of the instrument for use with PSTs.

In our analyses, cases with 50% or more valid responses for each time of measurement were included in the dataset. We scaled the data collected using the teacher noticing measure with ConQuest 5.28 software (Adams et al., 1997-2023) with both measurement times combined using a three-dimensional Rasch model3. To estimate the item parameters, missing responses were considered not administered to include only valid answers. Missing responses were treated as incorrect for estimating a person’s abilities. Weighted likelihood estimates (WLEs) were applied to create ability scores for perception, interpretation, and decision-making.

The item–total correlations ranged from 0.12 to 0.54, with an acceptable mean of 0.30. The weighted mean square (a component of the fit statistic that ideally yields a value of 1.0) varied in an acceptable range between 0.87 and 1.14, with an average of 1.00. The scales reached at least acceptable separation reliability, as shown in Table 2. WLE reliability for decision-making was somewhat questionable, possibly due to the small total number of decision-making items associated with a complex construct and the variety of decision-making contexts represented in the instrument, which is a common problem when measuring decision-oriented constructs (Weyers et al., 2024). The attenuation-corrected latent correlations between the three facets were comparable to previous studies, with correlations of r = 0.79 between perception and interpretation, r = 0.88 between interpretation and decision-making, and r = 0.50 between perception and decision-making (Bastian et al., 2022).

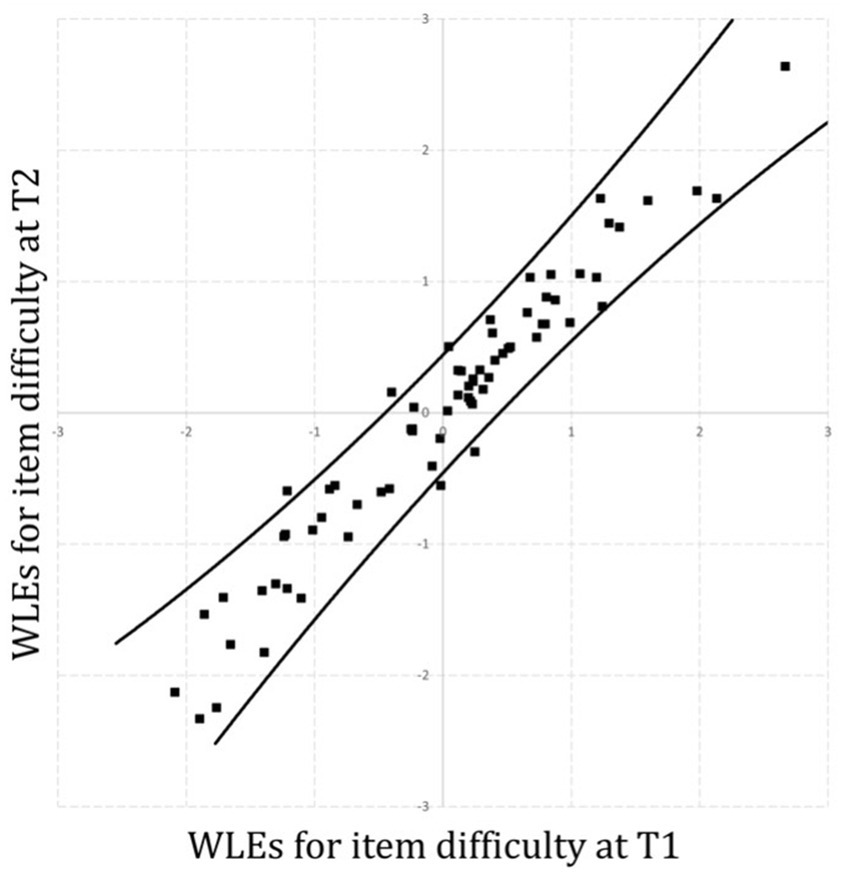

To account for measurement invariance, we computed additional separate Rasch models for each measurement time. WLEs were then deployed to compare item difficulties at T1 and T2 (Bond et al., 2021). A correlation of r = 0.97 between T1 and T2 indicated a comparable measurement (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Item difficulty invariance for T1 versus T2. Each box represents one item. WLE – weighted likelihood estimate. Lines indicate the 95% confidence interval.

To gain insight into PSTs’ individual experiences and the implementation of teaching internships, we adapted scales from the Learning to Practice study and the COACTIV-R study to assess (1) learning time (i.e., time spent on certain activities), (2) teaching practice activities, and (3) mentor support (Kunter et al., 2013; König et al., 2014). With these scales, we aimed to measure the number and quality of activities performed, as well as the perceived quality of mentor support, which previous studies have found to have an important influence on PST development, as described in the literature review. For the analyses, we transformed the learning time subscales into an interval scale measure. Teaching practices subscales were created using sum scores, mentor support subscales by mean scores. The subscales, sample items, and descriptive statistics are presented in Table 3. Internal consistency was at least acceptable.

To address the first research question concerning reciprocal effects of the three facets of teacher noticing, we computed autocorrelations and an autoregressive manifest model with a cross-lagged panel design using the WLEs with Mplus 6.8 software (Muthén and Muthén, 1998-2021). Although the teacher education programs and, in particular, the teaching internships at all six universities in our sample shared key components, they were not, of course, completely similar. To account for differences and impacts of teacher educators, teaching type and modules and thus the stratified nature of the sample, we specified a stratification variable combining university and teaching types using the “type = complex” option.

We approached the second research question which addressed changes in PST’s noticing skills using paired sample t-tests. We calculated the Cohen’s d effect sizes for a within-subjects design (Lakens, 2013) to estimate the impact of teaching internships on teacher noticing and compare our results with previous findings.

Again, we used multiple regression analyses to investigate the third research question, considering the stratified sample. We conducted several analyses (for each set of subscales separately) to examine the effects of process variables on the ability scores for each teacher noticing facet at T2. Regression analyses were controlled for high school diploma grade, semester, and dichotomized teaching type (academic-track and vocational school vs. non-academic-track and special needs education), as well as the ability scores for the teacher noticing facets at T1.

We now present the results in three subsections, each of which addresses one of our research questions, before discussing the results in the next section.

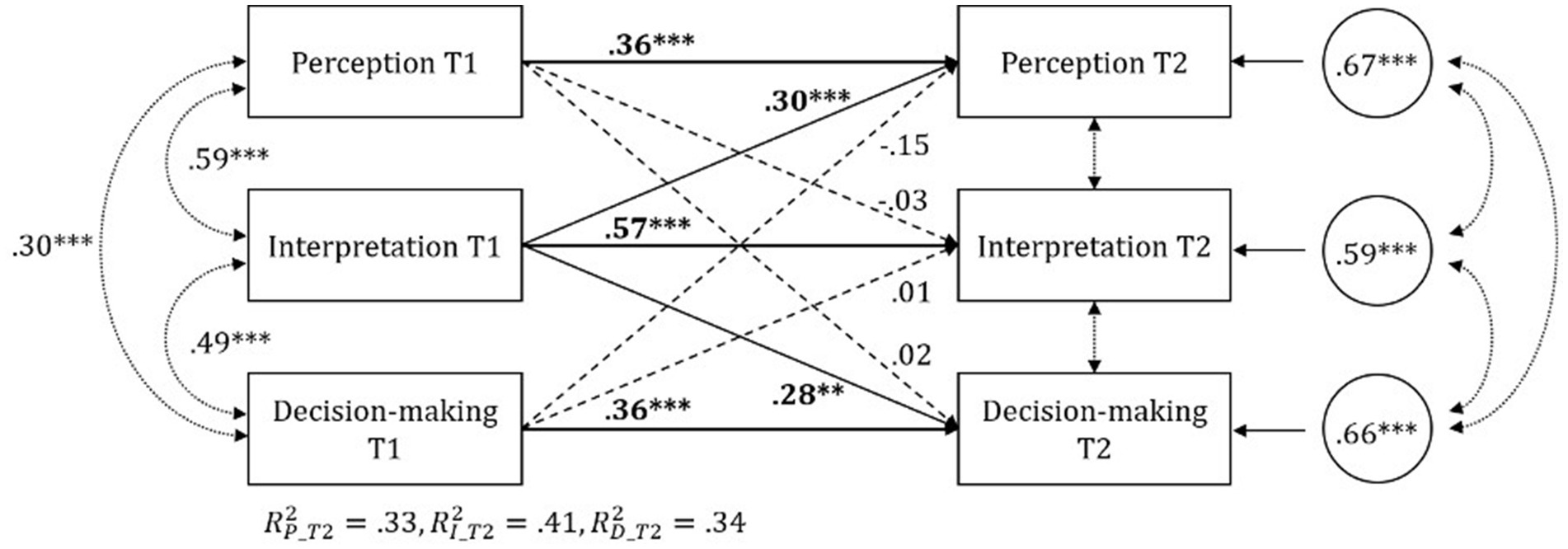

To answer our first research question, we conducted cross-lagged panel analyses. The stability of the teacher noticing facets was investigated using autocorrelations. Positive medium to strong autocorrelations for perception (r = 0.50, p < 0.001), interpretation (r = 0.62, p < 0.001) and decision-making (r = 0.52, p < 0.001) indicated stable parts of these constructs, but also emphasized intrapersonal variation and, thus, change during the teaching internships4. We applied a cross-lagged panel model to assess the predictive quality of the three facets at T1 for the facets at T2 (see Figure 5). The means and standard deviations for all ability scores are presented in Table 4, and the correlations between all facets of teachers’ noticing are presented in Table 5. The correlations suggested possible cross-lagged effects between the three facets. Measures of reliability have already been discussed (see Table 2).

Figure 5. Cross-lagged panel model for the facets of teachers’ noticing. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. ≙ coefficient of determination for perception at T2/interpretation at T2/decision-making at T2, respectively. In the analysis, we controlled for high school diploma grade, semester, and dichotomized teaching type. The path coefficients display the standardized results. Significant regression coefficients are shown in bold for ease of reading. Values in ovals on the right indicate unexplained variance.

The auto-lagged path coefficients showed significant moderate predictive power for perception (β = 0.36, p < 0.001) and decision-making (β = 0.36, p < 0.001), and a strong effect for interpretation (β = 0.57, p < 0.001). The cross-lagged path coefficients demonstrated that only interpretation had an effect on the other facets, since both paths from interpretation at T1 to perception at T2 (β = 0.30, p = 0.001) and decision-making at T2 (β = 0.28, p = 0.002) were significant, but not the reverse cross-lagged paths. This indicated a prominent role for interpretation in the development of all three facets. No cross-lagged effect was observed between perception and decision-making. For all three facets, the model explained a significant amount of the variance.

To answer the second research question, we compared the measurements of individual teachers’ noticing skills before and after the teaching internships using t-tests to explore the effects of the practical activities (see Table 4). Significant increases were found for all three facets of teachers’ noticing over the course of the teaching internships. The effect sizes, expressed as Cohen’s d, revealed small effects for all three facets, with a higher effect size for interpretation.

The third research question was answered using multiple regression analyses to investigate the effects of the teaching internship process variables on the development of PSTs’ teacher noticing. For each scale (i.e., learning time, teaching practice activities, and mentor support) and for each noticing facet a model was calculated using all subscales of the scale as predictors. The results of these analyses are illustrated in Tables 6–8. They showed the significant influences of process variables for only a few subscales. A significant proportion of the variance was explained.

For learning time, there was only a positive effect of lesson follow-up on decision-making (β = 0.19, p = 0.006), while lesson preparation negatively influenced decision-making (β = −0.21, p = 0.039). For the teaching practice activities, linking theories to specific situations significantly predicted perception and interpretation, with positive regression coefficients of β = 0.19, p = 0.014 and β = 0.25, p < 0.001, respectively. In contrast, teaching (i.e., performing situations) showed a negative effect on perception (β = −0.26, p = 0.001) but no effects on interpretation and decision-making.

Emotional support provided by PSTs’ mentors had a significant positive effect on decision-making (β = 0.27, p = 0.002). In contrast, instrumental support, such as providing teaching materials, negatively affected interpretation (β = −0.14, p = 0.048) and decision-making skills (β = −0.15, p = 0.046).

In this study, we aimed to examine the reciprocal effects of the facets of teachers’ noticing during teaching internships, together with the effects of the internships and their implementation on the development of PSTs’ teacher noticing. We now discuss the results for each research question and the limitations of this study.

We examined teachers’ noticing and its three facets (perception, interpretation, and decision-making) in the course of teaching internships. The results revealed that the three facets improved significantly during the internships, and abilities at T1 significantly predicted ability scores at T2, particularly for interpretation. This is consistent with a study by Jong et al. (2021), who reported similar effects for the noticing facets of perception and interpretation. However, their regression coefficients were smaller than those in our study, and no significant prediction was found for decision-making. Since Jong et al. (2021) investigated the development of teachers’ noticing during a university course that did not include practical activities in schools, this suggests that practical field experiences play an important role for facilitating PSTs’ development of teacher noticing skills.

Furthermore, the cross-lagged analysis highlighted interpretation skills as vital for the development of teachers’ noticing, since interpretation had cross-lagged effects on perception and decision-making, but no reverse paths were significant. This confirms previous findings regarding the influence of interpretation on perception (Superfine et al., 2017; Jong et al., 2021) and provides further insight into the development of decision-making skills. The results of the cross-lagged analysis may also indicate a causal effect of interpretation on the development of perceptual and decision-making skills.

Additionally, the critical role of interpretation in our data underscores the conceptualization of teachers’ noticing as a knowledge-based construct (Sherin, 2007), challenging prior conceptualizations implying a more linear learning path of perception followed by interpretation and then decision-making (van Es, 2011). Our findings suggest that the ability to interpret classroom events and student thinking seem to be key to developing all three facets of teachers’ noticing and, thus, to perceiving relevant details and making productive decisions in the classroom. Initial learning to interpret might facilitate perception and decision-making in the classroom (Superfine et al., 2017). Our findings also suggest that interpretation skills can facilitate the application of professional knowledge in situation-specific school contexts. Hence, it is crucial to provide PSTs with sufficient opportunities to learn interpreting before, during, and after their teaching internships.

We investigated the impact of the teaching internships on perception, interpretation, and decision-making by comparing the PSTs’ pre- and posttest ability scores. The results showed significant increases for all three facets. The changes observed corroborated similar findings by Stürmer et al. (2013) and Mertens and Gräsel (2018), again supporting the important role of teaching internships in fostering the development of PSTs’ teachers’ noticing during their university education and complementing these studies with a subject-specific perspective on teacher noticing. Moreover, previous studies have not reported this improvement in decision-making skills; thus, our results make a recent contribution to the literature. However, the effect sizes in our study were somewhat smaller than expected based on previous studies (Mertens and Gräsel, 2018; Weber et al., 2018) and indicated only small but significant effects. This might be explained by the weaker connection between university education and teaching internships in some parts of North Rhine-Westphalia, where a significant part of the participants studied, offering fewer opportunities to relate theory to practice (Doll et al., 2018). Previous studies have suggested that the degree of theory–practice linkage may have an impact on the effect size of changes in teachers’ noticing over the course of teaching internships (Weber et al., 2018).

We explored the influences of the teaching internship process variables and, thus, the organization and implementation of internships for the individual PSTs using regression analyses, which showed effects for only some of the variables, particularly positive influences of making connection between theory and practice and emotional mentor support. This raises questions about the necessity for and current form of some features of teaching internships, such as lesson planning, which, surprisingly, showed no effects or negative effects on the three facets of teachers’ noticing.

The amount of time spent on lesson preparation had a negative effect on decision-making, which may be explained by the PSTs’ lack of lesson planning skills; that is, the PSTs were unable to make sufficient use of this time due to their lack of knowledge about lesson planning (König et al., 2022a). On the other hand, this result may indicate that PSTs who prepared longer or more extensively for lessons were more restricted in their expectations about the decisions to be made in class, had fewer opportunities to practice a variety of decisions, and thus fewer opportunities to develop their decision-making skills. Furthermore, teaching (e.g., teaching one’s own lessons and assisting a teacher in co-teaching) had no positive effect on teachers’ noticing. This is particularly interesting since PSTs often request more of these activities in their university education (Hascher, 2014; Ulrich et al., 2020) and engage extensively in these activities during their teaching internships (see Table 3; König et al., 2018b). Time spent on teaching even had a negative impact on perception. Hence, participation in classroom teaching alone does not seem to be sufficient for developing teachers’ noticing competence, complementing prior results that demonstrated the risks of adopting established school practices from in-service teacher without reflecting on them (Özgün-Koca and İlhan Şen, 2006; Chitpin et al., 2008). PSTs who focus their teaching internships predominately on performing situations may have less time for processing and reflection and may therefore adopt established school practices without questioning them. Extended practical learning opportunities thus do not automatically lead to increases in teacher competence, as empirical findings from TEDS-M have indicated for teacher education in Germany and the United States (König and Blömeke, 2012).

However, making connections between theory and experience in the internships and reflecting on practice appear to facilitate the development of teachers’ noticing, as linking theories to situations significantly predicted perception and interpretation, and time spent on lesson follow-up predicted decision-making. These findings agree with those of and Stürmer et al. (2013) and Weber et al. (2018, 2020), who described growth in teachers’ noticing skills, particularly in the context of accompanying reflection-oriented and analysis-oriented activities, and also with similar results for the development of professional knowledge (Schlag and Glock, 2019). Furthermore, the results also accord with the analyses of König and Blömeke (2012), who reported higher levels of general pedagogical knowledge for PSTs who focused on reflection rather than on teaching alone. Establishing connections between theory and the field experiences of PSTs (e.g., through reflection) seems to be a decisive factor in the development of teachers’ noticing during teaching internships.

Mentor support has proved to be highly important for PSTs during their teaching internships (Hudson and Millwater, 2008; García-Lázaro et al., 2022). In this study, only emotional support facilitated PSTs’ development, and only in terms of decision-making. The opportunity to talk with experienced teachers, express their concerns and uncertainties, and receive encouragement seems to help PSTs make in-the-moment decisions in classroom situations. In contrast, instrumental support (i.e., the provision of teaching methods and materials, such as worksheets) had a negative relationship with interpretation and decision-making. Again, a possible explanation may be that PSTs who receive more instrumental support adopt teaching styles and methods in an unreflective manner and have fewer opportunities to connect educational theories independently with their applications in practice. On the other hand, PSTs with higher interpretive and decision-making skills may require less instrumental support.

The limitations of this study should be considered. First, the results presented herein were derived from convenience sampling. Consequently, generalizations should only be made with caution. Group effects of the six-university sample were controlled for in the analyses using stratification variables. However, this approach may not have accounted for all effects of the different locations and may potentially have overlooked additional group-specific effects. In addition, for organizational reasons, it was not possible to establish control groups to evaluate the influence of the teaching internships against a group that did not undertake internships and to control for memory effects. However, this only influenced the overall effect of the internships on the three facets of teachers’ noticing for the second research question.

Moreover, the design of the study included only two measurement time points, which provided a rather rough representation of the development of teachers’ noticing over the course of the teaching internships. Research with more measurements at shorter time intervals is needed to gain more insight into the development of teachers’ noticing and, in particular, into the optimal length of an internship, since saturation effects may occur during this activity.

Process variables (i.e., learning time, teaching practice activities, and mentor support) were measured only through self-report instruments, which may have created bias in the dataset. Third-party assessments by mentors or researchers, for example, should be used to complement our findings. Furthermore, our test instrument assessed only a subset of teachers’ professional competencies; thus, the development of other competence facets may have been overlooked, and more comprehensive survey designs are needed to consider knowledge, beliefs, and situation-specific and/or performance-related facets together and to obtain a deeper understanding of the effects of teaching internships on PSTs.

Finally, some parts of the data collection took place during the COVID-19 pandemic. This influenced the organization of the teaching internships in ways that differed among schools. Our items for the internship process variables specifically included participation in online and distance learning and teaching, which provided some control for the changed conditions. Nevertheless, the pandemic may have had some unknown effects on our study.

Teaching internships have become an increasingly important, but also challenging and expensive, part of initial teacher education for the development of PSTs’ professional competence, which calls for empirical studies in this area and particularly quantitative analyses towards potential effects on PST learning outcomes (Lawson et al., 2015; König and Rothland, 2018; Ulrich et al., 2020; Terhart, 2021). This study addressed research gaps toward the development of teachers’ noticing over the course of teaching internships, in particular providing insight for the first time into the development of subject-specific teacher noticing skills and particularly decision-making skills, the effects of process variables of teaching internships, and the reciprocal effects of facets of teacher noticing. As the results are based on an established teacher noticing instrument and a framework that combines general pedagogical as well as mathematics pedagogical perspectives, and the core characteristics of German teaching internships are comparable to other international formats, they promise to be meaningful in contexts other than in this study. The results can inform the structure and organization of teaching internships and field experiences in initial teacher education internationally, as well as providing insights into the development of teacher noticing on a theoretical level in general.

The development of interpreting as a key skill for enhancing teachers’ noticing and applying knowledge learned at the university to the classroom was shown to be of great importance in this study. Therefore, we propose to focus more strongly on this facet to prepare PSTs for and accompany changes in teachers’ noticing during teaching internships. The initial fostering of interpretation may reduce later cognitive load and make it easier for PSTs to learn perception and decision-making in a meaningful way. Since few variables explained interpretation skills in our analyses, further research is needed to explore how interpretation skills can be fostered and what variables might explain the development of these skills. Weyers et al.’s (2023a) results suggest effects on interpretation skills of average high-school diploma grade and, thus, academic capability, as well as opportunities to learn from university education.

Regarding the structure of teaching internships, our findings suggest a need to strengthen theory–practice linkage activities in the practice of teaching internships. Overall, our study suggests that teaching internships and teaching practice activities have the potential to foster teachers’ noticing as a central facet of future professional practice and promote the connection between practice, teacher noticing, and academic knowledge.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because we do not have the consent by participants to release their data. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Z2FicmllbGUua2Fpc2VyQHVuaS1oYW1idXJnLmRl.

The studies involving humans were approved by Faculty of Education, University of Hamburg. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

AB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JK: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. JW: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. H-SS: Investigation, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. GK: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Methodology.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was conducted in the context of the project TEDS-Validate-Transfer funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant number: 16PK19006A/B).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^In this study, we use the term teaching internship to describe long-term practical activities integrated in teacher education at universities.

2. ^In the current discourse, the terms teacher noticing and professional vision are employed as comparable and overlapping, situation-specific constructs (Weyers et al., 2023b). In the current study, we use the more common term (teacher noticing; König et al., 2022b) to describe this construct and our own conceptualization of it. However, since the characteristics of the facets delineated in the research on noticing and professional vision vary, we employ the authors’ terminology when referring to specific studies.

3. ^The total number of missing responses was rather small (7.6%), so the person ability parameters could be estimated from the available data. Missing amounts per case ranged from 1–38% with a median of 3.9%.

4. ^Values above 0.10/0.30/0.50 indicate small/medium/strong effects, respectively (Cohen, 1988).

Adams, R. J., Wu, M., Macaskill, G., Haldane, S., Sun, X. X., Cloney, D., et al. (1997-2023). ConQuest (Version 5.28) [Computer software] Australian Council for Educational Research Available at: https://www.acer.org/gb/conquest

Amador, J. M., Bragelman, J., and Superfine, A. C. (2021). Prospective teachers’ noticing: a literature review of methodological approaches to support and analyze noticing. Teach. Teach. Educ. 99, 103256–103216. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2020.103256

Bastian, A., Kaiser, G., Meyer, D., Schwarz, B., and König, J. (2022). Teachers’ noticing and its growth toward expertise: an expert–novice comparison with pre-service and in-service secondary mathematics teachers. Educ. Stud. Math. 110, 205–232. doi: 10.1007/s10649-021-10128-y

Berliner, D. C. (1988). The development of expertise in pedagogy. American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education, Washington, D.C.

Blömeke, S., Gustafsson, J. E., and Shavelson, R. J. (2015a). Beyond dichotomies: competence viewed as a continuum. J. Psychol. 223, 3–13. doi: 10.1027/2151-2604/a000194

Blömeke, S., Jentsch, A., Ross, N., Kaiser, G., and König, J. (2022). Opening up the black box: teacher competence, instructional quality, and students’ learning progress. Learn. Instr. 79, 101600–101611. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2022.101600

Blömeke, S., König, J., Suhl, U., Hoth, J., and Döhrmann, M. (2015b). Wie situationsbezogen ist die Kompetenz von Lehrkräften? Zur Generalisierbarkeit der Ergebnisse von videobasierten Performanztests. Zeitschrift Pädagogik 61, 310–327.

Bond, T. G., Yan, Z., and Heene, M. (2021). Applying the Rasch model: fundamental measurement in the human sciences. New York, London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Cabaroğlu, N., and Öz, G. (2023). Practicum in ELT: a systematic review of 2010–2020 research on ELT practicum. European Journal of Teacher Education, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2023.2242577

Caires, S., and Almeida, L. S. (2005). Teaching practice in initial teacher education: its impact on student teachers’ professional skills and development. J. Educ. Teach. 31, 111–120. doi: 10.1080/02607470500127236

Chitpin, S., Simon, M., and Galipeau, J. (2008). Pre-service teachers’ use of the objective knowledge framework for reflection during practicum. Teach. Teach. Educ. 24, 2049–2058. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2008.04.001

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 20, 37–46. doi: 10.1177/001316446002000104

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cohen, E., Hoz, R., and Kaplan, H. (2013). The practicum in preservice teacher education: a review of empirical studies. Teach. Educ. 24, 345–380. doi: 10.1080/10476210.2012.711815

Cortina, K. S., and Thames, M. H. (2013). “Teacher education in Germany” in Cognitive activation in the mathematics classroom and professional competence of teachers. eds. M. Kunter, J. Baumert, W. Blum, U. Klusmann, S. Krauss, and M. Neubrand (New York: Springer), 49–62.

Dindyal, J., Schack, E. O., Choy, B. H., and Sherin, M. G. (2021). Exploring the terrains of mathematics teachers’ noticing. ZDM Math. Educ. 53, 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s11858-021-01249-y

Doll, J., Jentsch, A., Meyer, D., Kaiser, G., Kaspar, K., and König, J. (2018). Zur Nutzung schulpraktischer Lerngelegenheiten an zwei deutschen Hochschulen: lernprozessbezogene Tätigkeiten angehender Lehrpersonen in Masterpraktika. Lehrerbildung Auf Dem Prüfstand 11, 24–45.

Dominguez, H. (2019). Theorizing reciprocal noticing with non-dominant students in mathematics. Educ. Stud. Math. 102, 75–89. doi: 10.1007/s10649-019-09896-5

Drahmann, M. (2020). “Teacher education in Germany: a holistic view of structure, curriculum, development and challenges” in Teacher education in the global era: perspectives and practices. ed. K. Pushpanadham (Singapore: Springer Singapore), 13–31.

Dreher, A., and Kuntze, S. (2015). Teachers’ professional knowledge and noticing: the case of multiple representations in the mathematics classroom. Educ. Stud. Math. 88, 89–114. doi: 10.1007/s10649-014-9577-8

Eckhardt, T. (2021). The education system in the Federal Republic of Germany 2018/2019: A description of the responsibilities, structures and developments in education policy for the exchange of information in Europe. Available at: https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/Dateien/pdf/Eurydice/Bildungswesen-engl-pdfs/dossier_en_ebook.pdf

Fernandez, C., and Choy, B. H. (2019). “Theoretical lenses to develop mathematics teacher noticing” in International handbook of mathematics teacher education: Volume 2: Tools and processes in mathematics teacher education. eds. S. Llinares and O. Chapman (Leiden: Brill), 337–360.

Festner, D., Gröschner, A., Goller, M., and Hascher, T. (2020). “Lernen zu Unterrichten – Veränderungen in den Einstellungsmustern von Lehramtsstudierenden während des Praxissemesters im Zusammenhang mit mentorieller Lernbegleitung und Kompetenzeinschätzung” in Praxissemester im Lehramtsstudium in Deutschland: Wirkungen auf Studierende. eds. I. Ulrich and A. Gröschner (Springer Wiesbaden: Fachmedien), 209–241.

García-Lázaro, I., Colás-Bravo, M. P., and Conde-Jiménez, J. (2022). The impact of perceived self-efficacy and satisfaction on preservice teachers’ well-being during the practicum experience. Sustain. For. 14:10185. doi: 10.3390/su141610185

Gold, B., and Holodynski, M. (2017). Using digital video to measure the professional vision of elementary classroom management: test validation and methodological challenges. Comput. Educ. 107, 13–30. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2016.12.012

Goodwin, C. (1994). Professional vision. Am. Anthropol. 96, 606–633. doi: 10.1525/aa.1994.96.3.02a00100

Gröschner, A., Müller, K., Bauer, J., Seidel, T., Prenzel, M., Kauper, T., et al. (2015). Praxisphasen in der Lehrerausbildung – Eine Strukturanalyse am Beispiel des gymnasialen Lehramtsstudiums in Deutschland. Z. Erzieh. 18, 639–665. doi: 10.1007/s11618-015-0636-4

Gröschner, A., Schmitt, C., and Seidel, T. (2013). Veränderung subjektiver Kompetenzeinschätzungen von Lehramtsstudierenden im Praxissemester. Zeitschrift Pädagog. Psychol. 27, 77–86. doi: 10.1024/1010-0652/a000090

Hascher, T. (2014). “Forschung zur Wirksamkeit der Lehrerbildung” in Handbuch der Forschung zum Lehrerberuf. eds. E. Terhart, H. Bennewitz, and M. Rothland (Münster, New York: Waxmann), 418–440.

Hoth, J., Schwarz, B., Kaiser, G., Busse, A., König, J., and Blömeke, S. (2016). Uncovering predictors of disagreement: ensuring the quality of expert ratings. ZDM 48, 83–95. doi: 10.1007/s11858-016-0758-z

Hudson, P., and Millwater, J. (2008). Mentors’ views about developing effective English teaching practices. Australian. J. Teach. Educ. 33. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2008v33n5.1

Jacobs, V. R., Lamb, L. L. C., and Philipp, R. A. (2010). Professional noticing of children’s mathematical thinking. J. Res. Math. Educ. 41, 169–202. doi: 10.5951/jresematheduc.41.2.0169

Jong, C., Schack, E. O., Fisher, M. H., Thomas, J., and Dueber, D. (2021). What role does professional noticing play? Examining connections with affect and mathematical knowledge for teaching among preservice teachers. ZDM Math. Educ. 53, 151–164. doi: 10.1007/s11858-020-01210-5

Kaiser, G., Blömeke, S., König, J., Busse, A., Döhrmann, M., and Hoth, J. (2017). Professional competencies of (prospective) mathematics teachers—cognitive versus situated approaches. Educ. Stud. Math. 94, 161–182. doi: 10.1007/s10649-016-9713-8

Kaiser, G., Busse, A., Hoth, J., König, J., and Blömeke, S. (2015). About the complexities of video-based assessments: theoretical and methodological approaches to overcoming shortcomings of research on teachers’ competence. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 13, 369–387. doi: 10.1007/s10763-015-9616-7

Keppens, K., Consuegra, E., de Maeyer, S., and Vanderlinde, R. (2021). Teacher beliefs, self-efficacy and professional vision: disentangling their relationship in the context of inclusive teaching. J. Curric. Stud. 53, 314–332. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2021.1881167

König, J. (2019). “Empirische Befunde zu Effekten von Praxisphasen in der Lehrerausbildung” in IFS-Bildungsdialoge: Band 3. Lehrerbildung - Potentiale und Herausforderungen in den drei Phasen. eds. N. McElvany, F. Schwabe, W. Bos, and H. G. Holtappels (Münster, New York: Waxmann), 29–52.

König, J., and Blömeke, S. (2012). Future teachers’ general pedagogical knowledge from a comparative perspective: does school experience matter? ZDM 44, 341–354. doi: 10.1007/s11858-012-0394-1

König, J., Cammann, F., Bremerich-Vos, A., and Buchholtz, C. (2022a). Unterrichtsplanungskompetenz von (angehenden) Deutschlehrkräften der Sekundarstufe: Testkonstruktion und Validierung. Z. Erzieh. 25, 869–894. doi: 10.1007/s11618-022-01113-z

König, J., Darge, K., Klemenz, S., and Seifert, A. (2018a). “Pädagogisches Wissen von Lehramtsstudierenden im Praxissemester: Ziel schulpraktischen Lernens?” in Learning to practice, learning to reflect? Ergebnisse aus der Längsschnittstudie LtP zur Nutzung und Wirkung des Praxissemesters in der Lehrerbildung. eds. J. König, M. Rothland, and N. Schaper. (Wiesbaden, Heidelberg: Springer VS), 287–323.

König, J., Darge, K., Kramer, C., Ligtvoet, R., Lünnemann, M., Podlecki, A.-M., et al. (2018b). “Das Praxissemester als Lerngelegenheit: Modellierung lernprozessbezogener Tätigkeiten und ihrer Bedingungsfaktoren im Spannungsfeld zwischen Universität und Schulpraxis” in Learning to practice, learning to reflect? Ergebnisse aus der Längsschnittstudie LtP zur Nutzung und Wirkung des Praxissemesters in der Lehrerbildung. eds. J. König, M. Rothland, and N. Schaper (Wiesbaden, Heidelberg: Springer VS), 87–114.

König, J., and Rothland, M. (2018). “Das Praxissemester in der Lehrerbildung: Stand der Forschung und zentrale Ergebnisse des Projekts Learning to Practice” in Learning to practice, learning to reflect? Ergebnisse aus der Längsschnittstudie LtP zur Nutzung und Wirkung des Praxissemesters in der Lehrerbildung. eds. J. König, M. Rothland, and N. Schaper (Münster, New York: Springer VS), 1–62.

König, J., Santagata, R., Scheiner, T., Adleff, A.-K., Yang, X., and Kaiser, G. (2022b). Teachers’ noticing: a systematic literature review of conceptualizations, research designs, and findings on learning to notice. Educ. Res. Rev. 36:100453. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100453

König, J., Tachtsoglou, S., Darge, K., and Lünnemann, M. (2014). Zur Nutzung von Praxis: Modellierung und Validierung lernprozessbezogener Tätigkeiten von angehenden Lehrkräften im Rahmen ihrer schulpraktischen Ausbildung. Z. Bild. 4, 3–22. doi: 10.1007/s35834-013-0084-2

Kunter, M., Baumert, J., Blum, W., Klusmann, U., Krauss, S., and Neubrand, M. (Eds.). (2013). Cognitive activation in the mathematics classroom and professional competence of teachers. Springer: New York

Lakens, D. (2013). Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 4:863. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863

Lawson, T., Çakmak, M., Gündüz, M., and Busher, H. (2015). Research on teaching practicum – a systematic review. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 38, 392–407. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2014.994060

Lenhard, W., and Lenhard, A. (2016-2022). Berechnung von Effektstärken. Psychometrica. Available at: https://www.psychometrica.de/effektstaerke.html

Louie, N., Adiredja, A. P., and Jessup, N. (2021). Teachers’ noticing from a sociopolitical perspective: the FAIR framework for anti-deficit noticing. ZDM Math. Educ. 53, 95–107. doi: 10.1007/s11858-021-01229-2

Mason, J. (2002). Researching your own practice: The discipline of noticing. Routledge, London, New York, http://oro.open.ac.uk/790/

Mertens, S., and Gräsel, C. (2018). Entwicklungsbereiche bildungswissenschaftlicher Kompetenzen von Lehramtsstudierenden im Praxissemester. Z. Erzieh. 21, 1109–1133. doi: 10.1007/s11618-018-0825-z

Mertens, S., Schlag, S., and Gräsel, C. (2018). Die Bedeutung der Berufswahlmotivation, Selbstregulation und Kompetenzselbsteinschätzungen für das bildungswissenschaftliche Professionswissen und die Unterrichtswahrnehmung angehender Lehrkräfte zu Beginn und am Ende des Praxissemesters. Lehrerbildung Auf Dem Prüfstand 11, 66–84.

Metsäpelto, R.-L., Poikkeus, A.-M., Heikkilä, M., Husu, J., Laine, A., Lappalainen, K., et al. (2021). A multidimensional adapted process model of teaching. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 34, 143–172. doi: 10.1007/s11092-021-09373-9

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (1998-2021). Mplus (version 8.6) [computer software] Muthén & Muthén. Available at: https://www.statmodel.com

Ng, W., Nicholas, H., and Williams, A. (2010). School experience influences on pre-service teachers’ evolving beliefs about effective teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 26, 278–289. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.03.010

Orschulik, A. B. (2020). Entwicklung der professionellen Unterrichtswahrnehmung: Eine Studie zur Entwicklung Studierender in universitären Praxisphasen. Dissertation thesis. Springer Spektrum

Özgün-Koca, S. A., and İlhan Şen, A. (2006). The beliefs and perceptions of pre-service teachers enrolled in a subject-area dominant teacher education program about “effective education”. Teach. Teach. Educ. 22, 946–960. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2006.04.036

Piwowar, V., Barth, V. L., Ophardt, D., and Thiel, F. (2018). Evidence-based scripted videos on handling student misbehavior: the development and evaluation of video cases for teacher education. Prof. Dev. Educ. 44, 369–384. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2017.1316299

Potari, D., and Chapman, O. (2020). “International handbook of mathematics teacher education” in Knowledge, beliefs, and identity in mathematics teaching and teaching development, vol. 1 (Leiden: Brill).

Santagata, R., König, J., Scheiner, T., Nguyen, H., Adleff, A.-K., Yang, X., et al. (2021). Mathematics teacher learning to notice: a systematic review of studies of video-supported teacher education. ZDM 53, 119–134. doi: 10.1007/s11858-020-01216-z

Santagata, R., and Yeh, C. (2016). The role of perception, interpretation, and decision making in the development of beginning teachers’ competence. ZDM 48, 153–165. doi: 10.1007/s11858-015-0737-9

Scheiner, T. (2021). Towards a more comprehensive model of teacher noticing. ZDM – Math. Educ. 53, 85–94. doi: 10.1007/s11858-020-01202-5

Scheiner, T. (2023). Shifting the ways prospective teachers frame and notice student mathematical thinking: from deficits to strengths. Educ. Stud. Math. 114, 35–61. doi: 10.1007/s10649-023-10235-y

Schlag, S., and Glock, S. (2019). Entwicklung von Wissen und selbsteingeschätztem Wissen zur Klassenführung während des Praxissemesters im Lehramtsstudium. Unterrichtswissenschaft 47, 221–241. doi: 10.1007/s42010-019-00037-8

Scholten, N., and Orschulik, A. (2022). Praxisdokumente zur Verknüpfung von Theorie und Praxis auf Basis der Professionellen Unterrichtswahrnehmung. Herausforderungen Lehrer Innenbildung Zeitschrift Konzeption Gestaltung Diskussion 5, 179–195. doi: 10.11576/HLZ-5233

Schubarth, W., Speck, K., Seidel, A., Gottmann, C., Kamm, C., and Krohn, M. (2012). “Das Praxissemester im Lehramt–ein Erfolgsmodell? Zur Wirksamkeit des Praxissemesters im Land Brandenburg” in Studium nach Bologna: Praxisbezüge stärken?! Praktika als Brücke zwischen Hochschule und Arbeitsmarkt. eds. W. Schubarth, K. Speck, A. Seidel, C. Gottmann, C. Kamm, and M. Krohn (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 137–169.

Seidel, T., and Stürmer, K. (2014). Modeling and measuring the structure of professional vision in preservice teachers. Am. Educ. Res. J. 51, 739–771. doi: 10.3102/0002831214531321

Seifert, A., and Schaper, N. (2018). “Die Veränderung von Selbstwirksamkeitserwartungen und der Berufswahlsicherheit im Praxissemester: Empirische Befunde zur Bedeutung von Lerngelegenheiten und berufsspezifischer Motivation der Lehramtsstudierenden” in Learning to practice, learning to reflect? Ergebnisse aus der Längsschnittstudie LtP zur Nutzung und Wirkung des Praxissemesters in der Lehrerbildung. eds. J. König, M. Rothland, and N. Schaper (Wiesbaden, Heidelberg: Springer VS), 195–222.

Seifert, A., Schaper, N., and König, J. (2018). “Bildungswissenschaftliches Wissen und Kompetenzeinschätzungen von Studierenden im Praxissemester: Veränderungen und Zusammenhänge” in Learning to practice, learning to reflect? Ergebnisse aus der Längsschnittstudie LtP zur Nutzung und Wirkung des Praxissemesters in der Lehrerbildung. eds. J. König, M. Rothland, and N. Schaper (Wiesbaden, Heidelberg: Springer VS), 325–347.

Shah, N., and Coles, J. A. (2020). Preparing teachers to notice race in classrooms: contextualizing the competencies of preservice teachers with antiracist inclinations. J. Teach. Educ. 71, 584–599. doi: 10.1177/0022487119900204

Sherin, M. G. (2007). “The development of teachers’ professional vision in video clubs” in Video research in the learning sciences. eds. R. Goldman, R. Pea, B. Barron, and S. Derry (New York, London Erlbaum), 383–395.

Sherin, M. G., Jacobs, V. R., and Philipp, R. A. (2011). “Situating the study of teachers’ noticing” in Studies in mathematical thinking and learning. Mathematics teachers’ noticing. eds. M. G. Sherin, V. R. Jacobs, and R. A. Philipp (New York, London: Routledge), 3–13.

Stigler, J. W., and Miller, K. F. (2018). “Expertise and expert performance in teaching” in The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance. eds. K. A. Ericsson, R. R. Hoffman, A. Kozbelt, and M. A. Williams (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 431–452.

Stürmer, K., Seidel, T., and Schäfer, S. (2013). Changes in professional vision in the context of practice. Gr. Organ. 44, 339–355. doi: 10.1007/s11612-013-0216-0

Superfine, A. C., Fisher, A., Bragelman, J., and Amador, J. M. (2017). “Shifting perspectives on preservice teachers’ noticing of children’s mathematical thinking” in Research in mathematics education teachers’ noticing: bridging and broadening perspectives, contexts, and frameworks. eds. E. O. Schack, M. H. Fisher, and J. A. Wilhelm (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 409–426.

Terhart, E. (2021). “Teacher education in Germany: historical development, status, reforms and challenges” in Asia-Europe education dialogue. Quality in teacher education and professional development: Chinese and German perspectives. eds. J. C.-K. Lee and T. Ehmke (London, New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis), 44–56.

Thomas, J., Dueber, D., Fisher, M. H., Jong, C., and Schack, E. O. (2021). Professional noticing coherence: exploring relationships between component processes. Math. Think. Learn. 25, 361–379. doi: 10.1080/10986065.2021.1977086

Ulrich, I., Klingebiel, F., Bartels, A., Staab, R., Scherer, S., and Gröschner, A. (2020). “Wie wirkt das Praxissemester im Lehramtsstudium auf Studierende? Ein systematischer Review” in Praxissemester im Lehramtsstudium in Deutschland: Wirkungen auf Studierende. eds. I. Ulrich and A. Gröschner (Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien), 1–66.

van Es, E. A. (2011). “A framework for learning to notice student thinking” in Studies in mathematical thinking and learning. Mathematics teachers’ noticing. eds. M. G. Sherin, V. R. Jacobs, and R. A. Philipp (New York, London: Routledge), 134–151.

van Es, E. A., and Sherin, M. G. (2002). Learning to notice: scaffolding new teachers’ interpretations of classroom interactions. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 10, 571–596.

Weber, K. E., Gold, B., Prilop, C. N., and Kleinknecht, M. (2018). Promoting pre-service teachers’ professional vision of classroom management during practical school training: effects of a structured online- and video-based self-reflection and feedback intervention. Teach. Teach. Educ. 76, 39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2018.08.008

Weber, K. E., Prilop, C. N., Viehoff, S., Gold, B., and Kleinknecht, M. (2020). Fördert eine videobasierte Intervention im Praktikum die professionelle Wahrnehmung von Klassenführung? – Eine quantitativ-inhaltsanalytische Messung von Subprozessen professioneller Wahrnehmung. Z. Erzieh. 23, 343–365. doi: 10.1007/s11618-020-00939-9