94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 11 November 2024

Sec. Higher Education

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1358429

This article is part of the Research Topic Inclusive Education in Intercultural Contexts View all 8 articles

Claudiu Coman1

Claudiu Coman1 Alexandru Neagoe2

Alexandru Neagoe2 Florina Magdalena Onaga2

Florina Magdalena Onaga2 Maria Cristina Bularca1

Maria Cristina Bularca1 Dumitru Otovescu3

Dumitru Otovescu3 Maria Cristina Otovescu4

Maria Cristina Otovescu4 Nicolae Talpă5*

Nicolae Talpă5* Bogdan Popa5

Bogdan Popa5Introduction: While being a complex concept, religion can shape the way people in general, and students in particular, behave and make decisions in different types of contexts. In this regard, our paper aimed to assess the way religiosity influences the school climate and the social behavior of students from confessional and non-confessional Romanian high schools in order to raise awareness regarding the importance of religion in students’ education.

Methods: We used a quantitative method and we applied a questionnaire to 353 students from confessional and non-confessional high schools in Timișoara, Romania.

Results and discussion: The results of our study show positive correlations between religiosity and school climate, revealing that students from confessional schools have stronger feelings of belonging and better relationships with their teachers.

In today’s society characterized by continuous change, education, and religion play an essential role in the development of people at the individual and social level (Autiero and Vinci, 2016; Lehrer, 1999). Broadly, education is considered the element that stands at the basis of society, the element that brings economic wealth, social prosperity and political stability (Idris et al., 2012). Besides being an educational environment, schools are also seen as social organizations (Osterman, 2000). While schools are institutions where students receive education, they are also social institutions whose members develop activities together in order to achieve specific goals (Turkkahraman, 2015). The relationships and connections established by people within schools, or with the community, are based on the social behavior of individuals (Bozkuş, 2014; Waters et al., 2009). Furthermore, the quality of the relationships formed within school grounds, and the social and emotional atmosphere that students encounter at school can influence the educational process and the social behavior of students (Kutsyuruba et al., 2015). All these elements are components of the school climate, which is considered a multifaceted concept (Chirkina and Khavenson, 2018; Grazia and Molinari, 2020), that can be used to predict the way students feel or behave at school (Maxwell et al., 2017).

An element that can significantly influence the life or behavior of people in general and students in particular is religion (Lehrer, 1999; McCullough and Willoughby, 2009). Previous studies revealed that people with high levels of religious morals and values are more involved in prosocial behavior (Cnaan et al., 2012; Shariff, 2015). Religion is present in all types of societies in various forms that differ depending on the culture of each society (Walsh, 2017). From a general perspective, all religions include a set of symbols and the act of veneration which is connected to a series of specific rituals (Giddens and Sutton, 1995). In this context, people usually act in relation to their religious beliefs, or in relation to the level of their religiosity (Mahaarcha and Kittisuksathit, 2013).

In the context of academic achievements and motivation, a study that focused on undergraduate students from five universities in Pakistan, showed that religion had a strong impact on the educational performance of Muslim students, compared to non-Muslims (Khalid et al., 2020). Considering this type of results, we could infer that in the educational context, religion has a role in shaping students’ behavior, by determining them to engage in behaviors that improve their academic performance. Another study, in which researchers conducted a literature review on the role of religion on academic achievements, showed that teenagers who have stronger religious beliefs, also obtain higher grades and tend to complete more years of higher education (Horwitz, 2021). However, the researchers emphasized that it was unclear whether religion only affected academic results related to the personality of the teenagers, such as grades, or if it influenced their performance in the context of standardized tests (Horwitz, 2021). Moreover, a study conducted on Muslim students from Jakarta, Indonesia, highlighted the fact that character education in the context of religious schools’ culture can contribute to the development of students’ religious character (Marini et al., 2018). Thus, the study revealed that elements such as respecting the teachings of a religion or practicing religious tolerance toward other people can determine the religious character of students (Marini et al., 2018).

Given the role of religion in economic contexts, a previous study also stated that the religions of different types of societies can influence the institutions that exist within those societies, and societies that lack adaptation skills because of their organizational structures can fall behind other societies which have the ability to adapt to change (Karaçuka, 2018). However, another study that focused on the Islamic religion and its role in economic and educational contexts, emphasized that the success certain Islamic commercial networks had over time, can be seen as “evidence that Islam supports trade and growth” (Kuran, 2018). Moreover, in the context of sub-Saharan Africa, Muslim elites have the necessary power to treat school choice as a way to express their religious identity. However, in communities in which Muslims are a minority, the study highlighted that Muslim parents made educational decisions without considering the way those choices were going to affect and influence the self-image of the Muslim community (Kuran, 2018). Considering the negative effects of religion, previous studies found that religion can have negative effects on income or gender equality (Basedau et al., 2018). Thus, religious people tend to pay more attention to their spiritual needs than to their material, basic needs, or religious rules or beliefs can often discriminate women (Basedau et al., 2018). However, another study, conducted on students from Nigerian schools, revealed that religion did not have a significant effect on the attitudes, beliefs, and values of girls regarding negative, antisocial behavior (Abimbade et al., 2019).

From an educational point of view, religion is a discipline that is taught in schools and the Romanian educational system offers schools the possibility to develop the teaching-learning process while focusing on religious aspects. Thus, in confessional schools, students’ education takes place from a religious perspective (Alberts, 2019). In Romania, the philosophy of confessional educational institutions is based on the vision of the Christian worldview. Our approach wants to emphasize the development of students’ personality from an academic and spiritual point of view.

Considering the aspects previously mentioned, the purpose of our paper is to assess how religiosity influences the school climate and the social behavior of students from both confessional and non-confessional Romanian high schools, aiming to raise awareness regarding the importance of religion in students’ education. We conducted a comparative analysis of the school climate and social behavior of students from both types of schools. The research objectives are to compare the school climate and social behavior of students between confessional and non-confessional schools, evaluate the level of religiosity among students in these institutions and its influence on school climate and students’ social behavior, and investigate the correlations between religiosity, school climate, and students’ social behaviors to determine what factors influence the perceived religiosity of the students.

The school climate is the element that differentiates one school from another, it has the power to influence the behavior of students and teachers (Rudasill et al., 2018; Syahril and Hadiyanto, 2018). While being a multidimensional concept (Grazia and Molinari, 2020), which defines school climate in four ways: academic, community, safety, and institutional environment (Wang and Degol, 2016), school climate can be understood in terms of the feelings and attitudes that students and teachers have due to the school environment in which they carry out their activities (Loukas, 2007; Thapa et al., 2013). Over time, many scales and surveys were developed in order to measure school climate (Kohl et al., 2013; Grazia and Molinari, 2020). One of these surveys is the What is Happening in This School Questionnaire—which comprises five dimensions: teacher support, peer connectedness, school connectedness, affirming diversity, rule clarity, reporting irregularities, and seeking help (Aldridge and Ala’I, 2013).

School climate reflects peoples’ experiences in the school environment, and it refers to a wide range of elements such as norms, values, interpersonal relationships, or learning and teaching practices (Cohen et al., 2009; Thapa et al., 2013). It has a major role in the life of students both from an educational and social perspective (Rudasill et al., 2018). Previous studies that focused on the connection between school climate and students’ socio-emotional health revealed that students who perceive their schools as supportive and well-structured environments in which teachers are treated with respect by other students have better socio-emotional outcomes (Wang and Degol, 2016; Larson et al., 2020; Wong et al., 2021).

The individual’s social behavior can be considered the result of its interpretation of the event or social situation, the situation to which the individual attributes values and meanings (Lubsky et al., 2016). Also, it can be discussed in terms of prosocial and antisocial behaviors. Prosocial behavior can be understood as the type of actions a person carries out which benefit other people (Pfattheicher et al., 2022). In order to develop such actions, individuals must pay attention to the needs, desires, or goals of other people (Staub, 1978). Antisocial behaviors involve actions and attitudes that are regarded as dysfunctional and which can have negative consequences at the individual and societal level (Byrd et al., 2014). Such actions include acts of bullying, domestic violence, or discrimination (Hashmani and Jonason, 2021).

Referring to students’ social behavior in relationship with the school climate, previous studies have shown that a negative school climate can determine students to have negative behavior, and even engage in actions that involve the victimization of other students (Giovazolias et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2013). The influence of school climate on the social behavior of students was also studied in the context of the phenomenon of bullying and delinquent behaviors. Researchers discovered significant correlations between school climate and bullying or victimization behaviors, arguing that the occurrence of such a phenomenon could be diminished by improving the school climate (Wang et al., 2013; Aldridge et al., 2018).

Religion is considered a unitary system that comprises practices and beliefs that are related to sacred things and that `unite into one single moral community called a Church (Durkheim, 1995). Religiosity is a multidimensional concept that implies religious affiliation, religious actions—going to church, praying, and religious beliefs and faith in divinity (Bjarnason, 2007). Religious beliefs, together with other elements such as culture or science influence the way individuals carry out their daily lives (Johnson et al., 2011). Considering the American context, in today’s society, religion and religiosity tend to be described more through the actions carried out by people at a certain time and place, such as going to church on Sundays (Williams, 2015). In this regard, the idea that religion shapes the behavior of people became a subject of interest for many researchers.

A previous study that focused on the matter of religiosity and peoples’ tendency to help others revealed that religious people were involved more in volunteering activities and were more willing to donate to religious organizations (Jackson et al., 1995). Another study emphasizes the role of religiosity in peoples’ decision to volunteer, showing that individuals who go to church regularly tend to volunteer more than people who do not usually go to church (Ruiter and De Graaf, 2006).

Religiosity has also been studied in relation to subjective well-being. Even though happiness and life satisfaction can be affected by the individual’s health or the individual’s relationships with other people (Goian, 2014), religiosity can influence positively the social motivation. Researchers show that religiosity was associated with behaviors that encouraged social affiliation (Van Cappellen et al., 2017). The ability of students to socially affiliate and to socialize is also influenced by their relationship with their parents (Grusec, 2011). If parents get more involved in the child’s activities, the child will develop better communication abilities (Goian, 2019).

Data were collected from 353 high-school students through a questionnaire. The questionnaire was applied in classrooms during courses between January and February 2020, which corresponds to the second semester of the 2019–2020 school year. The questionnaire was self-administrated and the average time needed to complete it was 30 min. The research population included students from high schools in Timișoara, Romania. Timișoara is part of the Banat region of Romania, a well-developed region from the perspective of educational institutions, and the perspective of institutions involved in social work or public organizations (Goian, 2013). For sampling, we used data based on the ranking of the high schools according to the results obtained at the baccalaureate exam in the June–July 2019 session. At the top of the high schools, we were primarily interested in the confessional high schools in order to be able to select non-confessional high schools as well.

To choose the appropriate sample, the following criteria were applied: (a) The four confessional high schools in Timișoara, with the mention that at the time of the research, one of these high schools was not confessional but included high school classes specializing in theology; (b) Four non-confessional high schools were selected, which had to be theoretical, not vocational (e.g., sports, artistic, pedagogical, and bilingual), state high schools, and located in the municipality of Timișoara. These schools were chosen according to the ranking of the confessional high schools, ensuring similarity in the baccalaureate exam results; (c) Due to the purpose of the research, the sample included students from the 10th to 11th grades, excluding those absent on the day the questionnaire was applied. The consideration underlying this selection takes into account, on the one hand, the fact that the students in the selected classes are in the middle of adolescence (16–17 years old), and on the other hand, the fact that they spent at least 1 year (9th grade) in the confessional school, so they can differentiate and perceive the specific school culture. Taking into account the aspects mentioned above, we included in the study four confessional schools and four non-confessional schools.

The participants consisted of 353 high school students, including 166 from confessional schools and 187 from non-confessional schools. Most students are aged between 15 and 18 years old, with an average age of 16.5 years old. Among the participants, 21 are 15 years old, 149 are 16 years old, 165 are 17 years old, and 18 are 18 years old. The data indicate that there are 161 boys (male—45.60%) and 192 girls (female—54.40%) (Table 1).

The questionnaire, which can be found in Appendix A, comprises four sections named A, B, C, and D, each section measuring a certain concept. The three concepts measured are: school climate, social behavior, and religiosity.

Section A includes items specific to the school climate, which was measured through an instrument elaborated by Aldridge and Ala’I (2013), called WHITS—What’s Happening In This School Questionnaire. The instrument was translated and adapted to the Romanian cultural context and it comprises six dimensions through which school climate is measured.

Section B includes items specific to social behavior: prosocial and antisocial behavior. The items were adapted from a scale used in previous studies (Padilla-Walker et al., 2018) that measures the general prosocial behavior of students toward individuals they do not know. Antisocial behavior is measured through two dimensions: aggressivity and delinquency.

Section C includes items specific to religiosity. Religiosity was measured by taking into account five dimensions. The first dimension—religious faith is measured through two items (C1 and C2 in the questionnaire), that were previously used in the World Values Survey in 2012 for the Romanian population (Inglehart et al., 2014). The other four dimensions: private religious practices, organizational religiousness, overall self-ranking, and religious preference/affiliation were taken and adapted from the instrument Brief Multi-dimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality—BMMRS (Fetzer Institute, 2003).

Section D includes items referring to the respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics: high school, grade, age, and gender.

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 20. To measure the reliability of the scales, a Cronbach test was performed for each of the dimensions of the measured concepts. The results of all the Cronbach tests showed values above 0.7, proving the reliability of the scales. Additionally, to validate and adapt the scales to the Romanian cultural context, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted for each of the analyzed concepts. According to the exploratory factorial analysis, school climate is measured through six factors: relationship with teachers, relationship with peers, affirming diversity, clarity of rules, reporting irregularities, and seeking help. Social behaviors are measured through three factors: prosocial behavior, antisocial behavior—aggression, and antisocial behavior—delinquency. In the case of religiosity, only one factor was extracted, which was named religiosity.

In this study, results with p < 0.05 are considered statistically significant, but those with p < 0.01 (highly significant statistical differences) or p < 0.005 (very significant statistical differences) are deemed to provide stronger evidence against the null hypothesis. Results with p < 0.001 (very highly significant statistical differences) demonstrate the highest level of statistical certainty, suggesting the effects are highly unlikely to be due to chance.

The research results revealed differences in school climate between the two types of schools, particularly regarding the relationship with teachers. In the case of students from confessional schools, the results showed more positive experiences concerning the support they receive from teachers. Compared to students from non-confessional schools, a higher percentage of students from confessional schools consider that teachers have a positive attitude toward the problems of the students and make an effort to understand them—t (353) = 4.442, p < 0.001—very highly significant statistical differences (Table 2).

Regarding the relationship with school in the context of students’ feeling of being part of that school, the results presented in Table 2, t (353) = 2.407, p < 0.05, reveal significant statistical differences between students of confessional and non-confessional schools in terms of feeling part of their school. Specifically, students from confessional schools declared to a higher extent than students from non-confessional schools, that they have a stronger feeling of being part of their school.

Concerning the fourth dimension of school climate—affirmation of diversity—the results from Table 2, t (353) = 3.523, p < 0.001, revealing very highly significant statistical differences, show a higher level of positive answers in the case of students from confessional schools, concerning their integration and appreciation of their culture in the school environment. In this regard, students from confessional schools, compared to students from non-confessional schools, consider to a higher extent that the school climate is integrative.

While referring to the dimension of rule clarity, the research revealed a greater tendency toward knowledge and appreciation of the rules among students from confessional schools (134 students out of 166). Table 3 shows that, for most of the time, students are aware of their school’s rules.

Regarding the prosocial behavior of students, our findings indicate that students from confessional schools have a higher level of prosocial behavior manifested through actions involving offering help. Table 4 presents the attitude of students toward offering help to people they do not know. The results in Table 4 [t (353) = 2.144, p < 0.05—significant statistical differences] revealed that students from confessional schools, compared to students from non-confessional schools, registered a higher tendency to help people they do not know, even if doing so is not always easy for them.

In order to understand better the differences between students’ social behavior depending on the type of school they attend, we performed a t-test. The results revealed that there are significant differences in the way students behave depending on the two types of schools (Table 4). Specifically, very highly significant statistical differences can be seen in the context of factor 2—antisocial behavior—delinquency: t (351) = −4.76, p < 0.001, and significant statistical differences in the context of factor 3—prosocial behavior: t (351) = 2.17, p = 0.03 (p < 0.05). Our findings revealed that in the case of confessional schools delinquent behavior registers lower levels, and with an error of 5%, the result shows that in confessional schools, students tend to engage more in prosocial behaviors.

To establish the level of association between students’ faith in God, or other divinity depending on the type of school they study in, a Chi-Square test was performed. Since the value of the test was χ2 = 36.457, df (3) with p = 0,000 (p < 0.001), it can be affirmed that the respondents from the two types of schools present very highly significant differences in terms of their faith in God, and these differences are not a result of the random sampling variation (Table 5).

As expected, the results point toward high levels of religious private and public behavior for students from confessional high schools. The existence of the differences between students’ level of religiosity is also highlighted by the results of the t-test. Thus, since t (351) = −15.57, p < 0.001—very highly significant statistical differences, with an error of 1%, we can affirm that compared to students from non-confessional schools, those who study in confessional schools have higher levels of religiosity.

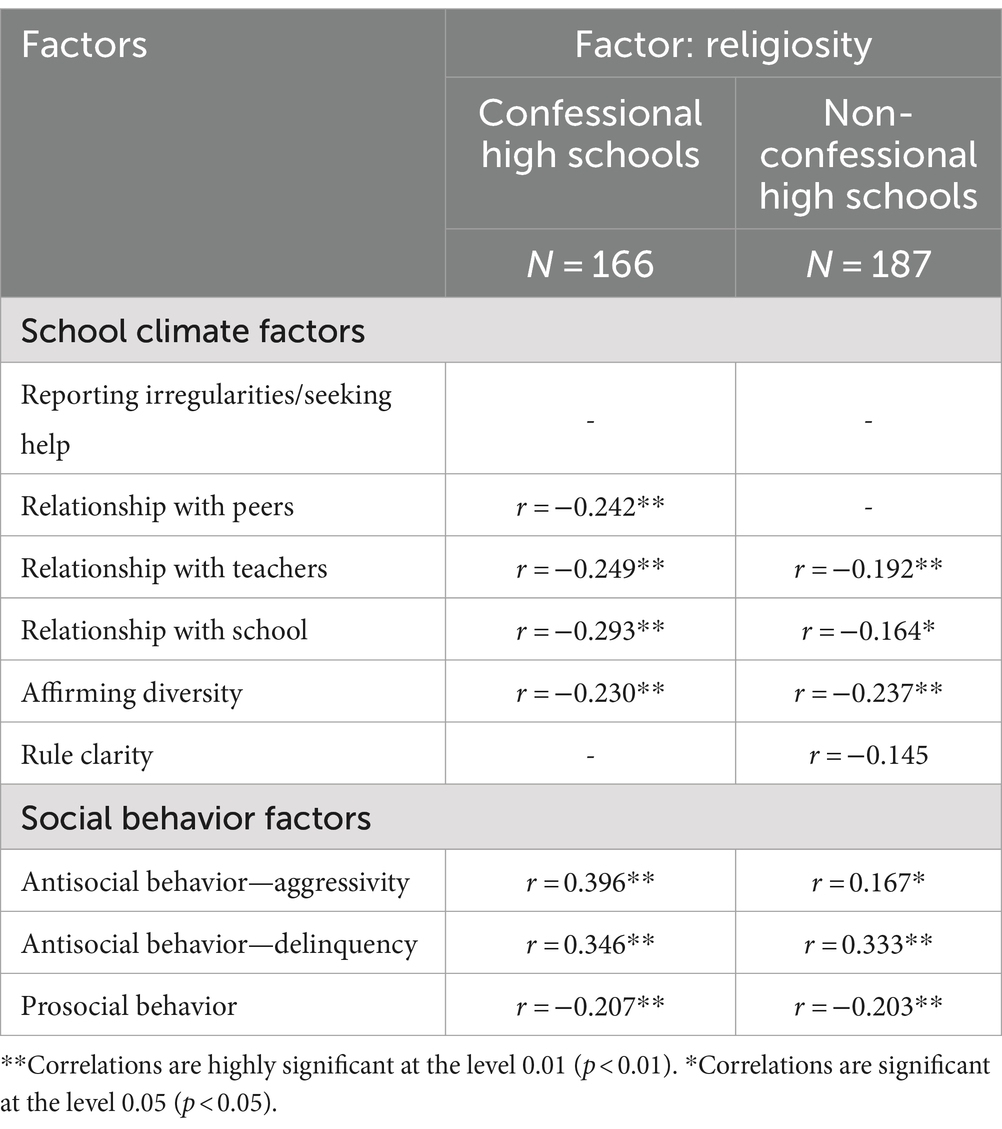

The analysis of the correlations of the three factors confirms the influence that religiosity has on school climate in both types of schools (Table 6). Even though the correlation can be considered weak (r < 0.30), higher values, at the significance level of 1% were registered in the case of confessional schools due to the high level of students’ religiosity. The strongest correlation can be seen in the case of students’ relationship with their school [r (164) = −0.29, p < 0.01—highly significant statistical differences], a result which strengthens the idea that students in confessional schools feel they are part of the community and they are respected, because of the intersection of the religious values of each student with the values of the school’s organizational culture. In the non-confessional school environment, a higher level of religiosity determines a higher level of students’ actions regarding affirming their diversity: r (185) = −0.23, p < 0.01—highly significant statistical differences (Table 6).

Table 6. Correlations between the factors: religiosity and school climate/students’ social behavior.

Our findings reveal correlations between religiosity and the social behavior of students. An increase in the level of religiosity is associated with a decrease in the tendency to engage in antisocial behavior and with an increase in the tendency to adopt prosocial behavior (Table 6). In confessional schools the correlation has a medium level of intensity between religiosity and students’ behavior manifested through aggressivity [r (164) = 0.39] and delinquency [r (164) = 0.34], at a level of highly significance p < 0.01. The results show that as students’ religiosity increases, their level of antisocial behavior decreases.

We used binary logistic regression modeling to find out what factors influence the perceived religiosity of the students. To answer this question, we defined the following variables: (i) Dependent variable: religiosity (with values 0—Little and not at all religious and 1—Very or moderately religious) obtained from item 10 in the questionnaire and (ii) Independent variables: school integration (or “school integration index” is a summative index obtained from variables i1–i48) and sociability (or “sociability index” is a summative index obtained from variables B1–B10 after the recodification of the variables in which B6–B10 were recoded). These two indexes have the descriptive values that are presented in Table 7.

Other categorical variables used in this model were: high school (with values 1—Confessional and 2—Non-confessional), gender (1—Male, 2—Female), and age (1–15 years old, 2–16 years old, 3–17 years old, 4–18 years old).

For logistic regression, the basic assumptions are: “independence of errors, linearity in the logit for continuous variables, absence of multicollinearity, and lack of strongly influential outliers” (Stoltzfus, 2011). All the assumptions were fulfilled. The multicollinearity among these two predictors from Table 7 was avoided (Spearman rho = 0.361, p < 0.001—very highly significant statistical differences). In addition, in all cases VIF < 10 guarantees the absence of multicollinearity. With the procedure Casewise List of extreme values we verified that there are no extreme values in the model. Finally, it is important to note that the observations were independent of each other.

In our binary logistic model with many independent variables, the formula can be: lny = bo+b1*school integration+b2*sociability+b3*high school+b4*gender+b5*age.

As is known, binary logistic regression operates with data in two blocks: (i) In Block 0 none of the predictors are in the model. From the classification table, we observed that the percentage of prediction rate is 64.3%; (ii) In Block 1, we observed the Omnibus Tests for Model Coefficients table. This indicates that the model is better than Block 0 (Chi-Square = 66.458, df = 7, p < 0.001—very highly significant statistical differences).

In the table Model Summary in SPSS Output, we tested the goodness of fit of the model. Using Cox & Snell R Square and Nagelkerke R Square, we decide that 23.6% of the variation in religiosity is explained by all variables included.

With Hosmer and Lemeshow test, we can conclude that the data proposed by the model are close to the real data [Chi-Square = 11.295, df = 8 and p = 0.186 (>0.05)].

Finally, how the table looks with all the variables included in the formula is presented in Table 8.

Binary logistic regression indicates that school integration, sociability, and high school are significant predictors for religiosity [Chi-Square = 66.458, df = 7 and p = 0.000 (<0.05)]. The other predictors gender and age are not significant. All the predictors “explain” 23.6% of the variability of religiosity. School integration was very highly significant at a confidence level of 95% (Wald = 12.92, p < 0.001); Sociability was very highly significant at a 95% confidence level (Wald = 11.13, p < 0.001) and high school was significant at a 95% confidence level. The odds ratio for school integration was 1.017 (95% CI 1.008–1.027); for sociability, the odds ratio was 1.067 (95% CI 1.027–1.108) and the odds ratio for high school was 2.765 (95% CI 1.676–4.563). The model correctly predicted 44.4% of cases where religiosity is low and 84.1% of cases where religiosity is high or moderate. Overall, the correctness of the prediction was 70%.

According to the results of our research, there are differences and similarities between the school climate of confessional and non-confessional schools, between the way students behave in such schools, and between students’ levels of religiosity. While previous studies (D’Agostino, 2017) revealed more similarities between the two types of schools, our results show more differences. We found out that students from confessional schools have better relationships with their teachers, they trust them enough to tell them if they were victims of bullying or other aggressions, and they feel that teachers try to understand their problems.

In the context of religiosity and the social behavior of students, our study is in line with a previous study conducted on Indonesian students from 11th grade, which showed that religiosity influenced students’ prosocial behavior, the authors stated that religious people tend to engage more in prosocial activities compared to non-religious people (Kurniawan et al., 2023). Furthermore, our research is in line with a previous study conducted on Filipino students which showed that exposure to religious contexts or concepts can increase the level of prosocial behavior of students (Batara et al., 2016). Our research is also in line with a study that revealed an indirect relationship between religiosity and the prosocial behavior of young adults, the relationship being mediated by their level of empathy. Thus, the researchers concluded that religious young adults tended to show more empathy toward the situations of other people (Han and Carlo, 2021). In the case of religiosity’s influence on social behavior, the main finding of our study shows that as the students’ level of religiosity increases, their antisocial behavior decreases. As other studies highlight the importance of a positive school climate for diminishing acts of bullying or other aggressions (Aldridge et al., 2018), our study also supports the idea that in positive climates like the ones from confessional schools, phenomena such as bullying are encountered less often than in other schools.

Even though our paper revealed interesting results regarding the way religion can have an influence on students’ behavior and on the school climate, the results should be considered in the Romanian context. In a broader, international context, the matter of religion and education has been approached by many researchers. Thus, a previous study that focused on analyzing religion in the educational context in Brazil, revealed that in basic schools, religious education is part of the curriculum and that most schools promote a catholic religious discourse (Senefonte, 2018). Another study, which focused on analyzing religion and education in Greek schools, showed religion had positive effects on students’ behavior and supports the idea that religion can have a positive influence on the development of adolescents (Liagkis, 2016).

While our study focused on emphasizing the way religion can influence the school climate and the social behavior of students, the way students behave is not exclusively influenced by the type of school they attend. In this regard, a discussion about the aspects of schooling experience that can influence the behavior of students is necessary.

The matter of parents’ school choice has been approached by many researchers who aimed to identify the elements that determine parents to choose a specific school. A previous study conducted in Alberta revealed that when making the decisions, parents who enrolled their children in private religious schools took into account their religious beliefs, they were prone to consult with family members but they did not consult with their children. Parents who enrolled their children in non-religious private schools, are most likely to consult with the teachers before making the decision, to visit the school and to consult with other parents (Bosetti, 2004).

Considering the results of our research, the paper also has some theoretical and practical implications. These implications mainly reside in the integrative approach of the educational system, of students’ behavior and religiosity in order to determine the valences of socialization in confessional schools. However, the implications also reside in the investigation of the subject while using a research instrument that was adapted to the socio-cultural Romanian context.

However, our study also has limitations. One limitation is represented by the fact that the influence of religiosity on school climate and social behavior was assessed only through a quantitative method with the help of a questionnaire. Future research could focus on analyzing the subject from a qualitative point of view too. Another limitation is represented by the fact that in our paper we only obtained information from students, and future research should also focus on gathering information from teachers.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by West University of Timisoara Ethics and Deontology Commission, Nr. 62454/0-1/14.11.2019. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because verbal consent was obtained from all study participants.

CC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft. AN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft. FO: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. MB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. DO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MO: Writing – review & editing. NT: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. BP: Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1358429/full#supplementary-material

Abimbade, O., Adedoja, G., Fakayode, B., and Bello, L. (2019). Impact of mobile-based mentoring, socio-economic background and religion on girls’ attitude and belief towards antisocial behaviour (ASB). Br. J. Educ. Technol. 50, 638–654. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12719

Alberts, W. (2019). Religious education as small'i'indoctrination: how European countries struggle with a secular approach to religion in schools. Center Educ. Policy Stud. J. 9, 53–72. doi: 10.26529/cepsj.688

Aldridge, J., and Ala’I, K. (2013). Assessing students’ views of school climate: developing and validating the What’s happening in this school? (WHITS) questionnaire. Improv. Sch. 16, 47–66. doi: 10.1177/1365480212473680

Aldridge, J. M., McChesney, K., and Afari, E. (2018). Relationships between school climate, bullying and delinquent behaviours. Learn. Environ. Res. 21, 153–172. doi: 10.1007/s10984-017-9249-6

Autiero, G., and Vinci, C. P. P. (2016). Religion, human capital and growth. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 43, 39–50. doi: 10.1108/IJSE-06-2014-0108

Basedau, M., Gobien, S., and Prediger, S. (2018). The multidimensional effects of religion on socioeconomic development: a review of the empirical literature. J. Econ. Surv. 32, 1106–1133. doi: 10.1111/joes.12250

Batara, J. B. L., Franco, P. S., Quiachon, M. A. M., and Sembrero, D. R. M. (2016). Effects of religious priming concepts on prosocial behavior towards ingroup and outgroup. Eur. J. Psychol. 12, 635–644. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v12i4.1170

Bjarnason, D. (2007). Concept analysis of religiosity. Home Health Care Manag. Pract. 19, 350–355. doi: 10.1177/1084822307300883

Bosetti, L. (2004). Determinants of school choice: understanding how parents choose elementary schools in Alberta. J. Educ. Policy 19, 387–405. doi: 10.1080/0268093042000227465

Bozkuş, K. (2014). School as a social system. Sakarya Univ. J. Educ. 4, 49–61. doi: 10.19126/suje.10732

Byrd, A. L., Loeber, R., and Pardini, D. A. (2014). Antisocial behavior, psychopathic features and abnormalities in reward and punishment processing in youth. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 17, 125–156. doi: 10.1007/s10567-013-0159-6

Chirkina, T. A., and Khavenson, T. E. (2018). School climate: a history of the concept and approaches to defining and measuring it on PISA questionnaires. Russ. Educ. Soc. 60, 133–160. doi: 10.1080/10609393.2018.1451189

Cnaan, R. A., Pessi, A. B., Zrinščak, S., Handy, F., Brudney, L. J., Grönlund, H., et al. (2012). Student values, religiosity, and pro-social behaviour: a cross-national perspective. Diaconia 3, 2–25. doi: 10.13109/diac.2012.3.1.2

Cohen, J., McCabe, E. M., Michelli, N. M., and Pickeral, T. (2009). School climate: research, policy, practice, and teacher education. Teach. Coll. Rec. 111, 180–213. doi: 10.1177/016146810911100108

D’Agostino, T. J. (2017). Precarious values in publicly funded religious schools: the effects of government-aid on the institutional character of Ugandan Catholic schools. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 57, 30–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2017.09.005

Fetzer Institute (2003). Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use in health research: A report of the Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging working group. John E. Fetzer Institute, Kalamazoo, MI.

Giovazolias, T., Kourkoutas, E., Mitsopoulou, E., and Georgiadi, M. (2010). The relationship between perceived school climate and the prevalence of bullying behavior in Greek schools: implications for preventive inclusive strategies. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 5, 2208–2215. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.437

Goian, C. (2013). The success of the social work apparatus in the Banat region. Analele Ştiinţifice ale Universităţii» Alexandru Ioan Cuza «din Iaşi. Sociol. Asist. Soc. 6, 31–39.

Goian, C. (2014). Transnational wellbeing analysis of the needs of professionals and learners engaged in adult education. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 142, 380–388. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.07.695

Goian, C. (2019). Parents counseling for improving the capacity of socialization of their preschool children. Educ. Plus 25, 122–131.

Grazia, V., and Molinari, L. (2020). School climate multidimensionality and measurement: a systematic literature review. Res. Pap. Educ. 36, 561–587. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2019.1697735

Grusec, J. E. (2011). Socialization processes in the family: social and emotional development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 62, 243–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131650

Han, Y., and Carlo, G. (2021). The links between religiousness and prosocial behaviors in early adulthood: the mediating roles of media exposure preferences and empathic tendencies. J. Moral Educ. 50, 419–435. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2020.1756759

Hashmani, T., and Jonason, P. K. (2021). “Antisocial behavior” in Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science. eds. T. K. Shackelford and V. A. Weekes-Shackelford (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 326–331.

Horwitz, I. M. (2021). Religion and academic achievement: a research review spanning secondary school and higher education. Rev. Relig. Res. 63, 107–154. doi: 10.1007/s13644-020-00433-y

Idris, F., Hassan, Z., Ya’acob, A., Gill, S. K., and Awal, N. A. M. (2012). The role of education in shaping youth's national identity. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 59, 443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.299

Inglehart, R., Haerpfer, C., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano, J., et al. (2014). World values survey: Round six-country-pooled datafile version. JD Systems Institute.

Jackson, E. F., Bachmeier, M. D., Wood, J. R., and Craft, E. A. (1995). Volunteering and charitable giving: do religious and associational ties promote helping behavior? Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 24, 59–78. doi: 10.1177/089976409502400108

Johnson, K. A., Hill, E. D., and Cohen, A. B. (2011). Integrating the study of culture and religion: toward a psychology of worldview. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 5, 137–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00339.x

Karaçuka, M. (2018). Religion and economic development in history: institutions and the role of religious networks. J. Econ. Issues 52, 57–79. doi: 10.1080/00213624.2018.1430941

Khalid, F., Mirza, S. S., Bin-Feng, C., and Saeed, N. (2020). Learning engagements and the role of religion. SAGE Open 10:2158244019901256. doi: 10.1177/2158244019901256

Kohl, D., Recchia, S., and Steffgen, G. (2013). Measuring school climate: an overview of measurement scales. Educ. Res. 55, 411–426. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2013.844944

Kuran, T. (2018). Islam and economic performance: historical and contemporary links. J. Econ. Lit. 56, 1292–1359. doi: 10.1257/jel.20171243

Kurniawan, K., Japar, M., and Purwanto, E. (2023). The effect of religious orientation on Students' prosocial behavior. J. Bimbingan Konsel. 12, 7–12.

Kutsyuruba, B., Klinger, D. A., and Hussain, A. (2015). Relationships among school climate, school safety, and student achievement and well-being: a review of the literature. Rev. Educ. 3, 103–135. doi: 10.1002/rev3.3043

Larson, K. E., Nguyen, A. J., Solis, M. G. O., Humphreys, A., Bradshaw, C. P., and Johnson, S. L. (2020). A systematic literature review of school climate in low and middle income countries. Int. J. Educ. Res. 102:101606. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101606

Lehrer, E. L. (1999). Religion as a determinant of educational attainment: an economic perspective. Soc. Sci. Res. 28, 358–379. doi: 10.1006/ssre.1998.0642

Liagkis, M. K. (2016). Teaching religious education in schools and adolescents’ social and emotional development. An action research on the role of religious education and School Community in Adolescents’ lives. Cult. Relig. Stud. 4, 121–133. doi: 10.17265/2328-2177/2016.02.004

Lubsky, A. V., Kolesnykova, E. Y., and Lubsky, R. A. (2016). Normative type of personality and mental matrix of social behavior in Russian society. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 9, 1–8. doi: 10.17485/ijst/2016/v9i36/102023

Mahaarcha, S., and Kittisuksathit, S. (2013). Relationship between religiosity and prosocial behavior of youth in Thailand. Human. Arts Soc. Sci. Stud. 13, 69–92.

Marini, A., Safitri, D. D., and Muda, I. (2018). Managing school based on character building in the context of religious school culture (case in Indonesia). J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 9, 274–294.

Maxwell, S., Reynolds, K. J., Lee, E., Subasic, E., and Bromhead, D. (2017). The impact of school climate and school identification on academic achievement: multilevel modeling with student and teacher data. Front. Psychol. 8:2069. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02069

McCullough, M. E., and Willoughby, B. L. (2009). Religion, self-regulation, and self-control: associations, explanations, and implications. Psychol. Bull. 135, 69–93. doi: 10.1037/a0014213

Osterman, K. F. (2000). Students' need for belonging in the school community. Rev. Educ. Res. 70, 323–367. doi: 10.3102/00346543070003323

Padilla-Walker, L. M., Memmott-Elison, M. K., and Coyne, S. M. (2018). Associations between prosocial and problem behavior from early to late adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 47, 961–975. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0736-y

Pfattheicher, S., Nielsen, Y. A., and Thielmann, I. (2022). Prosocial behavior and altruism: a review of concepts and definitions. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 44, 124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.08.021

Rudasill, K. M., Snyder, K. E., Levinson, H., and Adelson, L. J. (2018). Systems view of school climate: a theoretical framework for research. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 30, 35–60. doi: 10.1007/s10648-017-9401-y

Ruiter, S., and De Graaf, N. D. (2006). National context, religiosity, and volunteering: results from 53 countries. Am. Sociol. Rev. 71, 191–210. doi: 10.1177/000312240607100202

Senefonte, F. H. R. (2018). The relationship between religion and education in Brazil. Rev. Linhas 19, 434–454. doi: 10.5965/1984723819402018434

Shariff, A. F. (2015). Does religion increase moral behavior? Curr. Opin. Psychol. 6, 108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.07.009

Stoltzfus, J. C. (2011). Logistic regression: a brief primer. Acad. Emerg. Med. 18, 1099–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01185.x

Syahril, S., and Hadiyanto, H. (2018). Improving school climate for better quality educational management. J. Educ. Learn. Stud. 1, 16–22. doi: 10.32698/0182

Thapa, A., Cohen, J., Guffey, S., and Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. (2013). A review of school climate research. Rev. Educ. Res. 83, 357–385. doi: 10.3102/0034654313483907

Turkkahraman, M. (2015). Education, teaching and school as a social organization. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 186, 381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.044

Van Cappellen, P., Fredrickson, B. L., Saroglou, V., and Corneille, O. (2017). Religiosity and the motivation for social affiliation. Personal. Individ. Differ. 113, 24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.02.065

Wang, C., Berry, B., and Swearer, S. M. (2013). The critical role of school climate in effective bullying prevention. Theory Pract. 52, 296–302. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2013.829735

Wang, M. T., and Degol, J. L. (2016). School climate: a review of the construct, measurement, and impact on student outcomes. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 28, 315–352. doi: 10.1007/s10648-015-9319-1

Waters, S. K., Cross, D. S., and Runions, K. (2009). Social and ecological structures supporting adolescent connectedness to school: a theoretical model. J. Sch. Health 79, 516–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00443.x

Williams, W. P. (2015). America’s Religions: From Their Origins to the Twenty-First Century. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Keywords: confessional schools, education, religion, school climate, social behavior

Citation: Coman C, Neagoe A, Onaga FM, Bularca MC, Otovescu D, Otovescu MC, Talpă N and Popa B (2024) How religion shapes the behavior of students: a comparative analysis between Romanian confessional and non-confessional schools. Front. Educ. 9:1358429. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1358429

Received: 01 May 2024; Accepted: 28 October 2024;

Published: 11 November 2024.

Edited by:

Maria Tomé-Fernández, University of Granada, SpainReviewed by:

Jorge Expósito-López, University of Granada, SpainCopyright © 2024 Coman, Neagoe, Onaga, Bularca, Otovescu, Otovescu, Talpă and Popa. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nicolae Talpă, bmljb2xhZS50YWxwYUB1bml0YnYucm8=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.