95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Educ. , 22 March 2024

Sec. Special Educational Needs

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1358354

This article is part of the Research Topic Advancing inclusive education for students with special educational needs: Rethinking policy and practice View all 10 articles

Background: Education should be inclusive, nurturing each individual’s potential, talents, and creativity. However, criticisms have emerged regarding support for autistic learners, particularly in addressing disproportionately high absence levels within this group. The demand for accessible, person-centered, neuro-affirming approaches is evident. This paper provides a program description of a structured absence support framework, developed and implemented during and following the Covid-19 pandemic. We detail creation, content, and implementation.

Methods: We collaborated with stakeholders, reviewed literature and drew on existing theoretical frameworks to understand absence in autistic learners, and produced draft guidance detailing practical approaches and strategies for supporting their return to school. The final resource was disseminated nationally and made freely available online with a supporting program of work around inclusive practices.

Results: The resource is rooted in neuro-affirming perspectives, rejecting reward-based systems and deficit models of autism. It includes key messages, case studies and a planning framework. It aims to cultivate inclusive practices with an autism-informed lens. The principles promoted include recognizing the child’s 24-hour presentation, parental partnership, prioritizing environmental modifications, and providing predictable, desirable and meaningful experiences at school. Feedback to date has been positive in terms of feasibility, face validity, and utility.

Conclusion: This novel, freely available resource provides a concise, practical framework for addressing absence in autistic learners by cultivating a more inclusive, equitable, and supportive educational system in which autistic individuals can thrive.

While the global prevalence of autism in school-age children is estimated at around 1–2% (Elsabbagh et al., 2012), some recent studies indicate higher prevalence, with the United States Center for Disease Control estimating that in 2020, one in 36 children aged 8 years (approximately 4% of boys and 1% of girls) was autistic (Maenner et al., 2020). In Scotland in 2022, the prevalence of needs related to autism was 2.6% in primary schools, and 16.22% of all pupils were neurodivergent (Maciver et al., 2023). The wider literature indicates that neurodivergent children spend less time at school than their peers (Munkhaugen et al., 2017; McClemont et al., 2021; John et al., 2022) with a high prevalence of school attendance issues particularly evident among autistic learners (Munkhaugen et al., 2017; Maynard et al., 2018; Adams et al., 2019; Totsika et al., 2020; John et al., 2022). Absence has further been put in the spotlight by the international literature on experiences of staying home and then returning to school following the Covid-19 pandemic (Spain et al., 2021; Kreysa et al., 2022; Meral, 2022). The consequences of this experience on the emotional wellbeing and attendance of neurodivergent children are still being felt today, necessitating action and coordinated responses by governments, schools and teachers (Genova et al., 2021).

Absences for autistic learners are influenced by interconnected factors, including bullying, social support, and mental health (Adams et al., 2019; Sobba, 2019; McClemont et al., 2021; Adams, 2022). Sensory sensitivities, as well as the individual’s levels of self-esteem, can introduce further complexity (Maynard et al., 2018). Conventional approaches to absence, for example those based on rewards, have often fallen short in achieving desired outcomes (Londono Tobon et al., 2018; Maynard et al., 2018). The lack of practical resources around support for autistic children, as well as professionals’ understanding of autism itself are key barriers (Melin et al., 2022). Professionals and stakeholders are calling for evidence-informed strategies (Preece and Howley, 2018; Melin et al., 2022). Autistic people stress the significance of solutions that resonate with their experiences, advocating for non-judgmental and neuro-affirming approaches (Dallman et al., 2022; Rutherford and Johnston, 2023).

Informed by the lived experiences of neurodivergent individuals, the neurodiversity paradigm has prompted a profound reassessment of historical research and support structures, challenging prevailing consensus and motivating the development of neuro-affirming practices in schools and other settings (Arnold, 2017; Fletcher-Watson and Happé, 2019; Dallman et al., 2022). Central to this ongoing transformation is a departure from traditional disorder-centric perspectives (Rutherford and Johnston, 2023). This viewpoint recognizes that adverse outcomes arise from person-environment interactions, rather than being inherent to individuals (Dallman et al., 2022). Neuro-affirming practice aims to foster acceptance and self-comprehension, as well as amplifying the voices, experiences, and needs of neurodivergent individuals (Roche et al., 2021; Wood et al., 2022). While the transition to neuro-affirming practices is gaining momentum, there is little comprehensive and accessible guidance on supporting autistic individuals who experience dysregulation or anxiety in school, and there remains a need to reassess the ways in which pedagogy and school environments are conceptualized and understood through a neuro-affirming lens (Cherewick and Matergia, 2023).

The complexity and high frequency of school absence among autistic children motivates the need for solutions. Comprehensive resources addressing school absence in autistic young people are crucial to tackle this complex issue. This paper outlines efforts to address anxiety related absences in autistic learners through the development of the “Anxiety Related Absence (ARA) resource.” Developed by the National Autism Implementation Team (NAIT) in Scotland, the resource provides a practical and accessible guide for staff working in and with schools, complemented by a dissemination and training program. This paper discusses the resource’s development, content, key messages, and implementation to date.

The National Autism Implementation Team (NAIT) leads an initiative that aims to bridge the evidence and policy-to-practice gap and facilitate lifespan whole systems change in neurodevelopmental practices (Scottish Government, 2011, 2018; Rutherford et al., 2021; Maciver et al., 2022, 2023; Curnow et al., 2023a,b; Rutherford et al., 2023; Rutherford and Johnston, 2023). The team is composed of neurodivergent and neurotypical individuals from a range of professional backgrounds including Education, Speech and Language Therapy, Occupational Therapy, Psychiatry and research. The full NAIT program aims to drive improvement and innovation in professional practice to create a neurodevelopmentally informed workforce through various mechanisms focussing on health and education provision for autistic and other neurodivergent individuals.

In the context of addressing absence, traditional terms like “truancy,” “school refusal,” or “school avoidance” are stigmatizing and child or family blaming. After discussion with stakeholders, a more suitable term emerged: “Anxiety Related Absence” or “ARA.” Our guidance recommends using this language to describe absences among autistic learners.

Scotland’s educational ethos prioritizes inclusivity, with a presumption of inclusive mainstream schooling for most learners (Scottish Government, 2019). This means that many classroom educators support learners, with “Support for Learning” teachers providing additional guidance as required. However, schools have considerable leeway in determining their own pathways and procedures for issues including additional support needs and absence. Although policy outlines the need for multidisciplinary and multiagency teams, the health and education systems in Scotland operate autonomously, differing in funding, staff, and practices, and concerns persist regarding the onus on educators to provide support for children with additional support needs (Ballantyne et al., 2022). Criticisms have been directed at the assessment process and allocation of resources and have identified a need for change in practitioner mindsets to better use resources allocated (Scottish Government, 2020). Concerns exist that the increased incidence of absence in Scottish schools is evolving into a crisis (Connolly et al., 2023) with an attendance rate of 90.2% in 2022/23 marking a deterioration of 2.8% since 2018/19 and 1.8% since 2020/21, the most significant single-year drop in attendance since the Scottish Government started collecting this data in 2010 (Scottish Government, 2023). Additional discussions with school leaders and educators in Scotland uncover a related trend: a notable surge in consistently low attendance among autistic learners (Connolly et al., 2023), with Scottish Government data indicating an attendance rate of 91.6% for autistic pupils in 2022 compared with 94.1% in the wider population (Scottish Government, 2022). Feedback and data from a national parent survey (Children in Scotland, Scottish Autism and the National Autistic Society, 2018) affirm that a majority requiring absence support have autism diagnoses or related needs. The Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated this, as home learning provides a less demanding, more regulated environment. Prolonged absences diminish tolerance for school challenges, eroding established support strategies.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the NAIT team engaged with stakeholders locally and nationally who were familiar with ARA experiences. The aim of this engagement was to identify the nature of the issues surrounding ARA experience for autistic children and young people and identify potential solutions. This involved:

1. Rapid review of scientific literature, policy, theoretical frameworks and approaches to support.

2. Professionals’ feedback—synthesis of existing knowledge through leveraging our clinical and educational networks to understand current practice and solicit perspectives from parents and children and young individuals. The NAIT team also drew on their own experience of working with families from years in practice as education and health professionals.

3. Stakeholder feedback: Virtual meetings conducted with parent volunteers to facilitate the collection of feedback from their children.

The full NAIT program of work represents a complex intervention with several interacting parts including work over health, education and community settings (Maciver et al., 2022). Developments in inclusive practice in education are a major focus, with several linked and interconnecting strands. This multifaceted approach aimed to embed inclusivity principles into the daily educational experiences of children and young people with the goal not only of addressing specific needs related to ARA but also to foster a more inclusive educational landscape overall. Two NAIT initiatives are particularly pertinent, as they form a core aspect of the context in which the ARA resourced was implemented, as briefly described here.

First, the ARA resource draws and builds on the CIRCLE resource, an evidence-informed resource for education and health professionals to support universal inclusive practice within schools (Maciver et al., 2020, 2021). CIRCLE aims to equip professionals with the guidance to assess and create inclusive environments and provides an introduction to a range of supports and strategies to support inclusion (Maciver et al., 2020, 2021). The central concept underpinning these efforts is the notion of “universal” supports, which embodies an inclusive classroom approach designed to meet the needs of all learners. This focus on good inclusive practice emphasizes the importance of proactively making adjustments before or alongside “specialist” interventions. The CIRCLE resource provides a framework promoting an “environment first” approach, as well as the idea that inclusion is a responsibility shared by all staff. The ideas that underpin effective supports and inclusion of autistic children specifically are highly consistent with the principles of inclusive schooling generally (Roberts and Webster, 2022) hence the application of the CIRCLE framework is supportive of practices around ARA. By incorporating CIRCLE ideas, educators can establish a foundation of universal inclusive practice (Maciver et al., 2020, 2021). NAIT supported national implementation of CIRCLE, providing a “train the trainer” package of videos and online materials to integrate the CIRCLE framework in schools. Additionally, online professional learning modules, created collaboratively with a government agency, were accessible to all teachers in Scotland, focusing on CIRCLE usage.

Second, the ARA resource approach is supported by and incorporates ideas from the SCERTS Framework, an evidence-informed assessment and planning approach for children and young people (Yi et al., 2022). The SCERTS Framework operates as a solution to address factors impacting ARA by concentrating on three aspects as described by Prizant et al. (2006). First, “Social Communication” entails comprehending the “How and Why” of individual communication. Next, “Emotional Regulation” involves identifying strategies for “self-regulation” to achieve calmness and happiness, and “mutual regulation” to assist others or to be assisted by others. Finally, “Transactional Supports” encompass “interpersonal support”—adaptations made by those around the individual, and “learning supports”—including visual aids, curriculum adjustments, and adaptations to physical learning resources for enhanced accessibility and success. The ARA resource equips practitioners to address key aspects of autistic experience by organizing ideas around SCERTS concepts, including an understanding of social communication, emotional regulation, and transactional supports (Prizant et al., 2006). NAIT supports the national implementation of SCERTS, including conducting training programs, in collaboration with SCERTS authors. This includes three-day training sessions, an online repository of SCERTS implementation guidance, and regional networks to provide guidance to professionals. SCERTS is a more specialist and complex framework so has lesser reach than universal application, but within some areas of Scotland it is becoming a more common model.

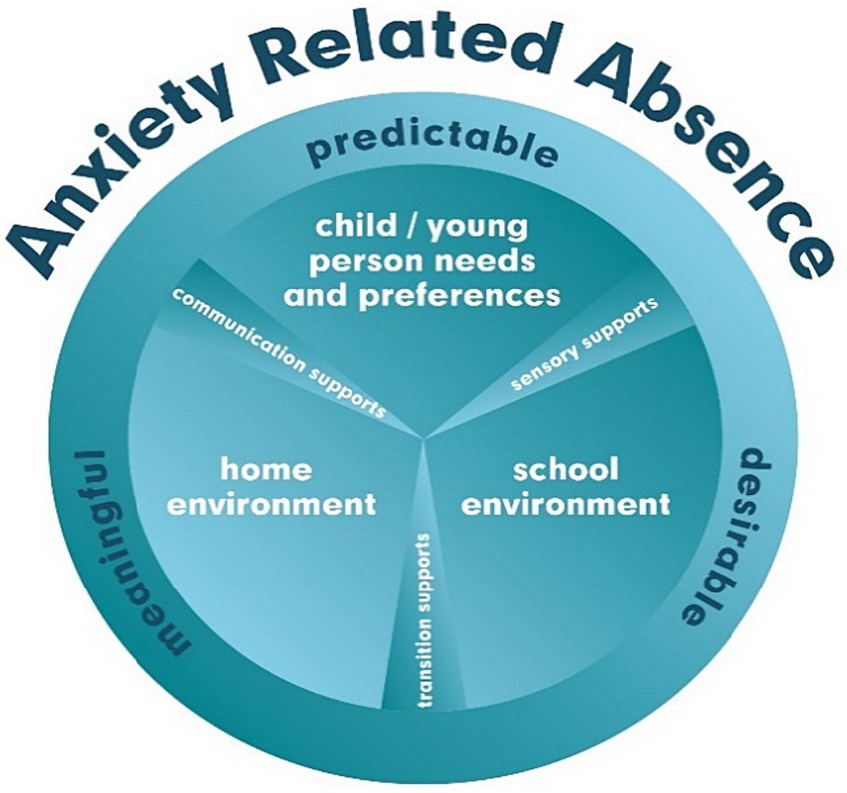

The 34-page ARA resource provides a short, practical and freely available guide for managing absences among autistic learners (see Supplementary material). The resource offers a structured approach, starting with the implementation of universal inclusive practice and highlighting key messages for supporting autistic children and young people. Case studies provide examples of the concepts discussed. Reflective practice is encouraged, and the resource extends its guidance to support within home and school environments, and for emerging and existing ARA situations. The resource includes references and recommended reading materials. The key ideas and key messages which are presented in the resource are discussed below. The planning framework is also presented. See Figure 1 for a diagram representing key ideas.

Figure 1. ARA resource. An overview of the key concepts underpinning the resource, focusing on communication, sensory and transactional supports and the provision of predictable, desirable and meaningful environments across home and school to meet the child or young person’s needs and preferences.

Table 1 provides an overview of the key concepts underpinning the resource. Central themes include the “24-hour child,” an approach that extends beyond school; effective communication and collaboration with families; and a focus on low cost and practical support strategies. The resource promotes an “environment-first” perspective, emphasizing modifications in social and physical environments of school and home with a focus on predictability, desirability, and meaningfulness aligned with the child’s interests and needs. The “environment first” principle further posits the primacy of adaptations to the learning environment over skills or “behaviors.” An autism-informed lens provides understanding of social complexities and coping mechanisms like masking. Importantly, the resource promotes positive educational experiences by eschewing external reward systems, seeking to enhance intrinsic motivation and self-driven engagement. Support strategies cover communication, sensory, and transition aspects.

Table 2 shows “key messages” for practitioners. The key messages are designed to promote realistic, appropriate and effective strategies to facilitate the establishment of an environment tailored to the specific needs of autistic children or young people, and to be high level and straightforward. Most involve shifts in teacher or other adult mindset, with minimal additional costs, meaning they are largely cost-neutral, an additional benefit for schools and practitioners. An anticipatory approach is advocated, predicated upon a comprehensive understanding of individual experiences, strengths, needs, and preferences. These key messages promote the importance of proactive planning and adjustments. They emphasize the value of engaging with parents to understand family dynamics and home life. Creating a predictable environment and curriculum are recommended, incorporating movement breaks into daily routines, the use of visual supports and provision of safe spaces. Practitioners are encouraged to shift their focus from labeling the child or young person as displaying “challenging behavior” to adopting a more compassionate perspective. Specifically, they are urged to reframe “challenging behavior” as a manifestation of distress which indicates a requirement for the adults around the child or young person to make adjustments and adaptations. This approach promotes a non-judgmental stance, fostering a proactive understanding of issues like autistic masking. Lastly, assigning two consistent key adults for each learner ensures clear communication and support during school activities and transitions.

Resolving anxiety related absence can take time (Maynard et al., 2018; Melin et al., 2022) and it is important that planning is individualized, consistent, organized and anticipatory. The ARA planning framework ensures a holistic and collaborative effort to enhance the school attendance experience for autistic children and young people, acknowledging the unique challenges they may face. A systematic process comprising several steps is recommended, with collaborative planning involving a team approach between practitioners, parents, and health professionals. Practitioners initiate the process through an assessment process and addressing the questions about the barriers to attendance present for a specific learner. The questions address developmental expectations, routine, predictability, independence support, environmental factors, desirability of activities, consistency of experiences in school, what success might look like for that learner, effective adaptations in place, involvement of various individuals, sensory preferences, parent views, and home-school communication. These inquiries aim to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the child and family’s experiences and promote a tailored, supportive approach. The planning cycle promotes reflective discussions, and setting realistic targets that prioritize adaptations to natural environments. Consistent communication, a staged intervention involving collaboration, and a cautious approach to traditional “therapeutic” methods (such as counseling or cognitive behavioral approaches) are also recommended.

The implementation methods are detailed below.

1. Initial guidance was sent out via email to professional networks in 2020 as part of a suite of resources targeted to return to school following the COVID 19 pandemic (see Supplementary material).

2. The resource was widely disseminated nationwide, made freely available online on the NAIT website, and supported by national virtual presentations and webinars. Invitations to the webinars were shared through professional distribution lists. The first of these presentations was delivered in 2020 through the Scottish Government Online Scottish Strategy for Autism Conference for which the Scottish Government requested pre-recorded themed submissions. A “Return to school” webinar was held in 2020 which focused on wider supports for learners to return to school, including support for those who may be experiencing anxiety (Rutherford and Johnston, 2020). A further national webinar was held in 2022, which offered insights into autism including its nature and assessment, as well as supports for absence (Rutherford and Johnston, 2022). Importantly, this webinar also provided information for leaders planning a strategic approach to attendance. The webinar recording was uploaded to a YouTube platform for teachers in Scotland and also the NAIT website, with an email to all delegates sharing a link to the resource and to a recording of the webinar.

3. Following the webinar in 2022, cascading through professional networks was facilitated by providing information and training resources to webinar delegates, with an invitation to share this with relevant and interested colleagues.

4. Links to the relevant information and guidance was also shared with national organizations, and uploaded to websites including those which teachers access and those which parents and carers might access.

Feedback was gathered during the webinar held in 2022, using an online tool. Delegates were also asked to complete a post-webinar evaluation which was shared via a QR code during the webinar and sent out again to all delegates. As well as this opportunity to evaluate the resource, feedback was also sought through professional networks and expert practitioners in 2022. A summary of feedback was collated by the NAIT team, with next steps identified. Engagement with professional leads in local areas is underway to provide a long-term evaluation including an ongoing survey of professionals who have accessed the resource. Feedback could be used to develop an updated version which will be disseminated in future.

The resource has garnered considerable interest and positive feedback, with 537 practitioners from 30 local authorities (geographic areas) attending the 2022 webinar, and 211 practitioners providing feedback after the event. The substantial turnout for the webinar affirms the resource’s face validity and its ability to engage staff. In reviewing feedback, attendees praised its balanced approach, advice, and informative content, noting that the recommendations were feasible and practical. An impactful aspect of the resource was noted as its ability to raise awareness and enhance understanding of autism. Feedback prompted the identification of “next steps.” Practitioners firstly expressed commitment to actively listen to autistic children and young people’s experiences. There was a recognized need to shift from surface-level to comprehensive autism-informed assessment. Practitioners discussed the importance of consistently promoting autism-informed thinking among staff, expressed a strong desire to discontinue ineffective practices, eliminate stigmatizing language like “school refusers,” and adopt “environment first” methods. Intentions were outlined to phase out reward-based approaches. Feedback stressed the fundamental importance of reflecting on current approaches and engaging in collaborative discussions with stakeholders. The necessity of listening to parents was emphasized, with a call to cease dismissing their perspectives, observations, and concerns, and avoid assumptions about uniformly shared goals among children, families, and schools. Practitioners highlighted the need to strengthen connections between home and school, recognizing the vital role of a supportive home-school partnership in providing comprehensive and effective support.

The NAIT ARA resource offers a concise, practical, and freely available framework for addressing absence in autistic children and young people. Given the persistent attendance challenges among autistic learners, practical resources are essential to empower staff working in and with schools. Developed through stakeholder consultation and implemented nationally during the COVID-19 pandemic, the resource signifies a shift toward supporting neurodivergent learners and fostering neuro-affirming mindsets. A key contribution is its capacity to cultivate inclusive thinking among school staff, aiming for more predictable, desirable and meaningful educational experiences. The resource prioritizes anticipatory support and autism-informed strategies over “behavioral” approaches, encouraging a focused understanding of anxiety causes. Proactively addressing attendance barriers for neurodivergent learners is crucial for creating an environment where they not only cope but thrive.

School communities and stakeholders are grappling with a lack of comprehensive neuro-affirming guidance, evidence-informed practices, and frameworks (Sobba, 2019; Anderson, 2020). In previous research, reasonable adjustments and the cultivation of peer connections have been shown to play a substantial role in creating an environment in which autistic learners can engage and thrive (Melin et al., 2022). Early detection and anticipatory support are also pivotal in averting chronic absences (Bonell et al., 2019; John et al., 2022). Some prevention and early intervention programs have focussed on school climate for reducing adolescent mental health problems (Bonell et al., 2019; John et al., 2022). Interventions might also focus on psychological support, for example anxiety (Delli et al., 2018) and school-based mental health (Greig et al., 2019; Punukollu et al., 2020). However generic strategies to improve attendance miss the key aspect of autistic learners needing to endure an environment they may find intolerable (Tomlinson et al., 2020). This also poses a substantial risk of encouraging masking and making the child feel that their authentic self or identity is not valid (Beardon, 2019). The ARA resource diverges from traditional methods by eschewing reward-based approaches by acknowledging that non-attendance among autistic learners often arises from factors beyond their control (Tomlinson et al., 2020; Totsika et al., 2020). Importantly, it does not advocate addressing anxiety related absence through alternative educational pathways like forest schools or homeschooling.

A notable innovation of the ARA program is its “environment-first” perspective, drawing on key concepts from the neurodiversity paradigm (Fletcher-Watson and Happé, 2019; Pellicano and den Houting, 2022), the social model of disability (Shakespeare, 2006) and the frameworks of CIRCLE (Maciver et al., 2021) and SCERTS (Yi et al., 2022). Protective environmental factors assume a key role in cultivating a supportive ecosystem for autistic learners (Hatton, 2018; Adams, 2022), extending beyond the school setting to encompass the child’s 24-hour life. The program aims to create a non-judgmental school environment, fostering understanding and support for children, young people and families. This perspective shifts the responsibility for change from the child to those in their environment. Meaningful change here arises from collective efforts. Instead of engaging in counseling or problem-solving with the child or young person, the ARA resource places the onus on adults to observe, reflect, and act. The program places significant emphasis on the notion that “the young person will do something… when the adults do something,” recognizing that action of adults is pivotal for achieving positive outcomes.

A key idea of the resource is that different reasons for absence exist, and that insights into possible mediating pathways, supports, and necessary actions stem from teachers’ models of why the absence is occurring (Klein et al., 2022). The ARA resource therefore places emphasis on understandings of why absence might be happening. Changing mindsets is key. Poor attendance labeled as truancy, for example, has negative connotations with teachers, who report irritation and frustration toward truant learners (Wilson et al., 2008). As a result, teachers are less willing to support (Klein et al., 2022). On the other hand, in the context of autism, when teachers possess a comprehensive understanding of autism and the reasons for absence, they are more inclined to help (Petersson-Bloom et al., 2023). An empathetic understanding of autistic individuals in a neurotypical world, as well as the extreme difficulties of some environments for autistic people, is essential for fostering appropriate actions. Autism-specific knowledge equips educators with the insights needed to create inclusive and accommodating environments. They can make adjustments that cater for sensory sensitivities and unique cognitive styles and foster an environment where support is effective in promoting the academic and personal growth of autistic learners (Petersson-Bloom et al., 2023). The goal is to make school a predictable, appealing, and meaningful choice for autistic learners and their families, ensuring that they select it as their primary option.

Future development, implementation, and dissemination will face barriers and facilitators. Barriers include general issues with attitudes to inclusion (Krischler and Pit-Ten Cate, 2019) as well as the theoretical and practical knowledge that school staff have about autism and related differences (Vincent and Ralston, 2020; Melin et al., 2022). Overcoming deficit-oriented mindsets and historical views of autism is crucial. Regarding facilitators, increasing awareness of autism and an emphasis on inclusivity and neurodiversity both within Scottish education and more widely in society are supportive, as is a desire for improved collaboration among health and education stakeholders. Positive feedback to date serves as a strong foundation for the use of this resource. Future research should focus on outcomes for schools and children and young people. The development of case studies of use in schools would offer in-depth examinations of real-world applications, contributing to the growing body of evidence on best practices for supporting neurodivergent learners.

Cross-cultural applicability of the ARA should be carefully considered given the context in which it was implemented. The NAIT program is grounded in the Scottish context. As a complex intervention building on an interacting network of pre-existing inclusive education strategies and ideas, the ARA approach and resources may require adaptation if applied in different contexts. However, the key underlying principles, mechanisms and potential outcomes proposed are relevant across many different contexts. Given the established association between anxiety and school absence internationally, as well as the pressing need to facilitate neuro-affirming practices in schools, it is likely that that the underpinning ideas and principles have wide applicability. Exploration of the transferability of the resource to different contexts may be valuable for those working to improve attendance for autistic students.

As the resource has been distributed widely online, it is not possible to obtain records to establish how many practitioners have subsequently accessed it. The resource has high levels of face validity; however, longer-term evaluation remains necessary. There is limited evaluation data from children, young people and families, and further evidence is required to assess how well practitioners can implement the recommendations and the resulting outcomes, both in preventing absence and ensuring return to school. This will inform further refinements and adjustments to the resource.

The NAIT ARA resource provides supports for practitioners. Our knowledge and application of the neurodiversity paradigm continues to evolve, and future review of the materials should reflect the most recent evidence about neuro-affirming practice creating a foundation for autistic individuals to engage academically and thrive.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

LJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DM: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AG: Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EC: Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IU: Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by Scottish Government.

Thank you to the partners and families who have supported this work and to the continued support of the Scottish Government.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1358354/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Data Sheet 1 | Anxiety Related Absence: A guide for Practice.

Adams, D. (2022). Child and parental mental health as correlates of school non-attendance and school refusal in children on the autism spectrum. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 52, 3353–3365. doi: 10.1007/s10803-021-05211-5

Adams, D., Young, K., and Keen, D. (2019). Anxiety in children with autism at school: a systematic review. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 6, 274–288. doi: 10.1007/s40489-019-00172-z

Anderson, L. (2020). Schooling for pupils with autism Spectrum disorder: Parents' perspectives. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 50, 4356–4366. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04496-2

Arnold, L. (2017). “A brief history of “neurodiversity” as a concept and perhaps a movement” in Autonomy, the Critical Journal of Interdisciplinary Autism Studies, vol. 1

Ballantyne, C., Wilson, C., Toye, M. K., and Gillespie-Smith, K. (2022). Knowledge and barriers to inclusion of ASC pupils in Scottish mainstream schools: a mixed methods approach. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 1-20, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2022.2036829

Beardon, L. (2019). “Autism, masking, social anxiety and the classroom” in Teacher education and autism: A research-based practical handbook

Bonell, C., Blakemore, S. J., Fletcher, A., and Patton, G. (2019). Role theory of schools and adolescent health. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 3, 742–748. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30183-X

Cherewick, M., and Matergia, M. (2023). Neurodiversity in practice: a conceptual model of autistic strengths and potential mechanisms of change to support positive mental health and wellbeing in autistic children and adolescents. Adv. Neurodev. Disord. doi: 10.1007/s41252-023-00348-z

Children in Scotland, Scottish Autism and the National Autistic Society. (2018). Not included, not engaged, not involved: A report on the experiences of autistic children missing school. Available at: https://www.notengaged.com/.

Connolly, S. E., Constable, H. L., and Mullally, S. L. (2023). School distress and the school attendance crisis: a story dominated by neurodivergence and unmet need. Front. Psych. 14:1237052. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1237052

Curnow, E., Rutherford, M., Maciver, D., Johnston, L., Prior, S., Boilson, M., et al. (2023a). Mental health in autistic adults: a rapid review of prevalence of psychiatric disorders and umbrella review of the effectiveness of interventions within a neurodiversity informed perspective. PLoS One 18:e0288275. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0288275

Curnow, E., Utley, I., Rutherford, M., Johnston, L., and Maciver, D. (2023b). Diagnostic assessment of autism in adults - current considerations in neurodevelopmentally informed professional learning with reference to ADOS-2. Front. Psych. 14:1258204. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1258204

Dallman, A. R., Williams, K. L., and Villa, L. (2022). Neurodiversity-affirming practices are a moral imperative for occupational therapy. Open J. Occupat. Ther. 10, 1–9. doi: 10.15453/2168-6408.1937

Delli, C. K. S., Polychronopoulou, S. A., Kolaitis, G. A., and Antoniou, A. G. (2018). Review of interventions for the management of anxiety symptoms in children with ASD. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 95, 449–463. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.10.023

Elsabbagh, M., Divan, G., Koh, Y. J., Kim, Y. S., Kauchali, S., Marcín, C., et al. (2012). Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Res. 5, 160–179. doi: 10.1002/aur.239

Fletcher-Watson, S., and Happé, F. (2019). Autism: A new introduction to psychological theory and current debate. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Genova, H. M., Arora, A., and Botticello, A. L. (2021). Effects of school closures resulting from COVID-19 in autistic and neurotypical children. Front. Educ. 6:761485. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.761485

Greig, A., MacKay, T., and Ginter, L. (2019). Supporting the mental health of children and young people: a survey of Scottish educational psychology services. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 35, 257–270. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2019.1573720

Hatton, C. (2018). School absences and exclusions experienced by children with learning disabilities and autistic children in 2016/17 in England. Tizard Learn. Disabil. Rev. 23, 207–212. doi: 10.1108/Tldr-07-2018-0021

John, A., Friedmann, Y., DelPozo-Banos, M., Frizzati, A., Ford, T., and Thapar, A. (2022). Association of school absence and exclusion with recorded neurodevelopmental disorders, mental disorders, or self-harm: a nationwide, retrospective, electronic cohort study of children and young people in Wales, UK. Lancet Psychiatry 9, 23–34. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00367-9

Klein, M., Sosu, E. M., and Dare, S. (2022). School absenteeism and academic achievement: does the reason for absence matter? AERA Open 8:233285842110711. doi: 10.1177/23328584211071115

Kreysa, H., Schneider, D., Kowallik, A. E., Dastgheib, S. S., Doğdu, C., Kühn, G., et al. (2022). Psychosocial and behavioral effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents with autism and their families: overview of the literature and initial data from a multinational online survey. Healthcare 10:714. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10040714

Krischler, M., and Pit-Ten Cate, I. M. (2019). Pre- and in-service Teachers' attitudes toward students with learning difficulties and challenging behavior. Front. Psychol. 10:327. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00327

Londono Tobon, A., Reed, M. O., Taylor, J. H., and Bloch, M. H. (2018). A systematic review of pharmacologic treatments for school refusal behavior. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 28, 368–378. doi: 10.1089/cap.2017.0160

Maciver, D., Hunter, C., Adamson, A., Grayson, Z., Forsyth, K., and McLeod, I. (2020). Development and implementation of the CIRCLE framework. Int. J. Disability, Development and Education. 67, 608–629. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2-2019.1628185

Maciver, D., Hunter, C., Johnston, L., and Forsyth, K. (2021). Using stakeholder involvement, expert knowledge and naturalistic implementation to co-design a complex intervention to support Children's inclusion and participation in schools: the CIRCLE framework [article]. Children (Basel) 8:217. doi: 10.3390/children8030217

Maciver, D., Rutherford, M., Johnston, L., Curnow, E., Boilson, M., and Murray, M. (2022). An interdisciplinary nationwide complex intervention for lifespan neurodevelopmental service development: underpinning principles and realist programme theory. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 3:1060596. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2022.1060596

Maciver, D., Rutherford, M., Johnston, L., and Roy, A. S. (2023). Prevalence of neurodevelopmental differences and autism in Scottish primary schools 2018-2022. Autism Res. Off. J. Int. Soc. Autism Res. 16, 2403–2414. doi: 10.1002/aur.3063

Maenner, M. J., Warren, Z., Williams, A. R., Amoakohene, E., Bakian, A. V., Bilder, D. A., et al. (2020). Prevalence and characteristics of autism Spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years — autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 72, 1–14. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7202a1

Maynard, B. R., Heyne, D., Brendel, K. E., Bulanda, J. J., Thompson, A. M., and Pigott, T. D. (2018). Treatment for school refusal among children and adolescents: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 28, 56–67. doi: 10.1177/1049731515598619

McClemont, A. J., Morton, H. E., Gillis, J. M., and Romanczyk, R. G. (2021). Brief report: predictors of school refusal due to bullying in children with autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 51, 1781–1788. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04640-y

Melin, J., Jansson-Frojmark, M., and Olsson, N. C. (2022). Clinical practitioners' experiences of psychological treatment for autistic children and adolescents with school attendance problems: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry 22:220. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-03861-y

Meral, B. F. (2022). Parental views of families of children with autism Spectrum disorder and developmental disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 52, 1712–1724. doi: 10.1007/s10803-021-05070-0

Munkhaugen, E. K., Gjevik, E., Pripp, A. H., Sponheim, E., and Diseth, T. H. (2017). School refusal behaviour: are children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder at a higher risk? Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 41-42, 31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2017.07.001

Pellicano, E., and den Houting, J. (2022). Annual research review: shifting from 'normal science' to neurodiversity in autism science. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 63, 381–396. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13534

Petersson-Bloom, L., Leifler, E., and Holmqvist, M. (2023). The use of professional development to enhance education of students with autism: a systematic review. Educ. Sci. 13:966. doi: 10.3390/educsci13090966

Preece, D., and Howley, M. (2018). An approach to supporting young people with autism spectrum disorder and high anxiety to re-engage with formal education - the impact on young people and their families. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 23, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2018.1433695

Prizant, B. M., Wetherby, A. M., Rubin, E., Laurent, A. C., and Rydell, P. J. (2006). The SCERTS model: A comprehensive educational approach for children with autism spectrum disorders, vol. 1. Baltimore, MD: Paul H Brookes Publishing.

Punukollu, M., Burns, C., and Marques, M. (2020). Effectiveness of a pilot school-based intervention on improving scottish students’ mental health: a mixed methods evaluation. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 25, 505–518. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2019.1674167

Roberts, J., and Webster, A. (2022). Including students with autism in schools: a whole school approach to improve outcomes for students with autism. Int. J. of Inclusive Education. 26, 701–718. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2020.1712622

Roche, L., Adams, D., and Clark, M. (2021). Research priorities of the autism community: a systematic review of key stakeholder perspectives. Autism 25, 336–348. doi: 10.1177/1362361320967790

Rutherford, M., Baxter, J., Johnston, L., Tyagi, V., and Maciver, D. (2023). Piloting a home visual support intervention with families of autistic children and children with related needs aged 0-12 [article]. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20:4401. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20054401

Rutherford, M., and Johnston, L. (2020). NAIT Webinar: Supporting the return to educational settings for autistic children and young people [Webinar]. YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HOtcm1Gr7lg.

Rutherford, M., and Johnston, L. (2022). NAIT Anxiety Related Absence Webinar May 2022 [Webinar recording]. YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AJ60SthiNzA.

Rutherford, M., and Johnston, L. (2023). “Perspective chapter: rethinking autism assessment, diagnosis, and intervention within a neurodevelopmental pathway framework” in Autism Spectrum disorders - recent advances and new perspectives (London, UK: IntechOpen)

Rutherford, M., Maciver, D., Johnston, L., Prior, S., and Forsyth, K. (2021). Development of a pathway for multidisciplinary neurodevelopmental assessment and diagnosis in children and Young people [article]. Children (Basel) 8:1033. doi: 10.3390/children8111033

Scottish Government (2018). Scottish strategy for autism: Outcomes and priorities 2018–2021. Edinburgh, UK: Scottish Government.

Scottish Government. (2019). Presumption to provide education in a mainstream setting: Guidance. Edinburgh: Scottish Government. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/guidance-presumption-provide-education-mainstream-setting/documents/.

Scottish Government. (2020). Support for Learning: All our Children and All their Potential. Edinburgh. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/independent-report/2020/06/review-additional-support-learning-implementation/documents/support-learning-children-potential/support-learning-children-potential/govscot%3Adocument/support-learning-children-potential.pdf.

Scottish Government. (2022). Summary Statistics for Schools in Scotland. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/summary-statistics-for-schools-in-scotland-2022/

Scottish Government. (2023). Summary statistics for schools in Scotland Edinburgh: Government, Scottish Retrieved from Summary statistics for schools in Scotland 2023 - gov.scot. Available at: http://www.gov.scot.

Shakespeare, T. (2006). “The social model of disability” in The Disability Studies Reader, vol. 2, 197–204.

Sobba, K. N. (2019). Correlates and buffers of school avoidance: a review of school avoidance literature and applying social capital as a potential safeguard. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 24, 380–394. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2018.1524772

Spain, D., Mason, D., J Capp, S., Stoppelbein, L., W White, S., and Happé, F. (2021). "This may be a really good opportunity to make the world a more autism friendly place": Professionals' perspectives on the effects of COVID-19 on autistic individuals. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 83:101747. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2021.101747

Tomlinson, C., Bond, C., and Hebron, J. (2020). The school experiences of autistic girls and adolescents: a systematic review. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 35, 203–219. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2019.1643154

Totsika, V., Hastings, R. P., Dutton, Y., Worsley, A., Melvin, G., Gray, K., et al. (2020). Types and correlates of school non-attendance in students with autism spectrum disorders. Autism 24, 1639–1649. doi: 10.1177/1362361320916967

Vincent, J., and Ralston, K. (2020). Trainee teachers’ knowledge of autism: implications for understanding and inclusive practice. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 46, 202–221. doi: 10.1080/03054985.2019.1645651

Wilson, V., Malcolm, H., Edward, S., and Davidson, J. (2008). 'Bunking off': the impact of truancy on pupils and teachers. Br. Educ. Res. J. 34, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/01411920701492191

Wood, R., Crane, L., Happé, F., Morrison, A., and Moyse, R. (2022). Learning from autistic teachers: How to be a neurodiversity-inclusive school. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Keywords: neuro-affirming, autism, education, pedagogy and practice, school inclusion, anxiety related absence, education resources, education research articles

Citation: Johnston L, Maciver D, Rutherford M, Gray A, Curnow E and Utley I (2024) A brief neuro-affirming resource to support school absences for autistic learners: development and program description. Front. Educ. 9:1358354. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1358354

Received: 19 December 2023; Accepted: 06 March 2024;

Published: 22 March 2024.

Edited by:

Wendi Beamish, Griffith University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Beth Saggers, Queensland University of Technology, AustraliaCopyright © 2024 Johnston, Maciver, Rutherford, Gray, Curnow and Utley. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lorna Johnston, bGpvaG5zdG9uMkBxbXUuYWMudWs=; Anna Gray, YWdyYXkyQHFtdS5hYy51aw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.