94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 21 May 2024

Sec. Language, Culture and Diversity

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1347816

This article is part of the Research TopicTeacher Responses to Bias-based BullyingView all 6 articles

Sevgi Bayram Özdemir*

Sevgi Bayram Özdemir* Metin Özdemir

Metin ÖzdemirSchools are crucial socialization contexts where civic norms and values such as appreciating diverse perspectives and embracing differences can be systematically transmitted to the next generations. This process, in turn, can foster the development of more inclusive societies. However, increasing polarized political climate poses a risk for the formation of harmonious interactions between youth of different ethnic origins in schools. Teachers are considered as crucial resources in addressing negative student interactions and helping victims in overcoming the consequences of their negative experiences. Nevertheless, our understanding of how teachers respond to ethnic victimization incidents is limited, along with the factors influencing their responses. To address this gap in knowledge, we examined the relative contributions of teachers’ general efficacy (i.e., managing disruptive behaviors in class) and diversity-related efficacy (i.e., addressing challenges of diversity) on their responses to ethnic victimization incidents. The sample consisted of head teachers of 8th grade students (N = 72; 56% females). The results showed that teachers adopt a diverse range of strategies to address incidents of ethnic victimization, with a primary focus on prioritizing the comfort of the victim as the foremost action. Further, we found that teachers’ efficacy in handling disruptive behaviors in class, as opposed to their efficacy in addressing diversity-related issues, explained their responses to victimization incidents. Specifically, teachers with a high sense of efficacy for classroom management were more likely to contact parents of both victims and perpetrators and to provide comfort to the victim. These findings highlight the necessity of supporting teachers to enhance their efficacy in classroom management, and in turn to address potential challenges in diverse school settings more effectively.

Schools are considered as one of the important socialization contexts, where children and adolescents with diverse backgrounds meet in the first place and where civic norms and values, including tolerance to differences, can be transmitted to the entire population of young people (Torney-Purta, 2002). Students’ experiences in diverse school context may have enduring implications for how they view and interpret differences among people and how they treat and interact with people from different backgrounds. A school environment that systematically promotes harmonious interactions among diverse student groups can offer an optimal educational and developmental setting for acquiring skills essential for functioning in a diverse society (Barrett, 2018). However, the increasing polarized political climate poses a risk for the formation of harmonious interactions between youth of different ethnic origins in schools. For instance, a recent report from Sweden showed that 48% of 5th grade students had either seen or heard something racist in their school at least once or even multiple times (Rädda Barnen, 2021). This finding is concerning and underscores the importance of taking systematic actions in schools to address this emerging social concern.

Teachers are often recognized as vital socialization agents capable of imparting socially acceptable values and behaviors to students (Farmer et al., 2011). They are also presumed to be crucial resources within schools for intervening in negative interactions among students (Yoon and Bauman, 2014; Burger et al., 2015) and assisting victims in overcoming the consequences of their adverse experiences (Huang et al., 2018; Bayram Özdemir et al., 2021b). Despite these presumptions, there is limited empirical knowledge about how teachers respond to negative interactions among students with diverse backgrounds and the factors influencing teachers’ actions. Developing such knowledge is necessary to prepare teachers for the changing needs of schools, and in turn societies at large. Consistently, our aim is to address this knowledge gap by exploring the extent to which context-specific self-efficacy (e.g., teachers’ efficacy for handling disruptive behaviors in class and efficacy for addressing challenges of diversity) contributes to teachers’ approaches to ethnic victimization incidents.

Bullying often occurs within a school environment, and teachers are assumed to be important figures that could intervene with the bullying processes. Teachers vary from one another regarding how they respond to bullying and victimization, and various conceptualizations exist to differentiate between these varied types of responses (Bauman et al., 2008; Marshall et al., 2009; Campaert et al., 2017). As Marshall et al. (2009) highlighted, some responses are explicitly directed either toward the perpetrator or the victim, such as disciplining bullying behavior or providing comfort and support to the victim. In contrast, other responses take a more indirect route by involving parents or initiating discussions with the entire class group or other school staff. Research examining the link between teachers’ responses and bullying reveals mixed or counterintuitive findings. Nonetheless, instances of lack of intervention or trivialization by teachers were generally found to be associated with high levels of bullying behaviors in class (Campaert et al., 2017), and contribute to non-defending behaviors among other students (Hektner and Swenson, 2012). On the other hand, teachers’ active efforts (e.g., adopting disciplinary sanctions, Campaert et al., 2017; establishing actions at class level; Wachs et al., 2019; making bullies feel empathy for the victim; Garandeaut et al., 2016; helping the involved students to find a solution; van Gils et al., 2022) have been found to be associated with low levels of engagement in bullying among adolescents. Even though the current state of empirical knowledge does not provide a clear picture as to which of these active efforts are most effective for reducing bullying, it can be still concluded that teachers’ active efforts might strengthen students’ beliefs about the non-acceptability of the behavior. In contrast, trivialization of bullying incidents might reinforce the development of immoral cognitive justifications among students, and result in greater likelihood of engagement in bullying (Campaert et al., 2017).

Various individual and contextual factors may influence teachers’ responses to bullying. For example, quantitative studies suggest that female teachers (Green et al., 2008) and teachers with high empathic skills tend to perceive peer victimization as a serious issue (Huang et al., 2018), and are more inclined to intervene in bullying incidents (Huang et al., 2018; Fischer S. M. et al., 2021; Kollerová et al., 2021). Moreover, teachers who perceive their school environment as cooperative and supportive are more likely to work with the bullies by helping them understand the consequences of their actions and encouraging more responsible behavior (Kollerová et al., 2021). In contrast, those who perceive their school climate as hostile are more inclined to discipline bullies and less likely to involve other adults in addressing bullying incidents (Yoon et al., 2016). Furthermore, qualitative studies highlight that teachers’ awareness of and sensitivity to bullying (D’Urso et al., 2023; Paljakka, 2023), as well as their specific knowledge on how to handle bullying incidents (D’Urso et al., 2023), may contribute to how effectively they approach this problem to find solutions. Specifically, it has been argued that when teachers lack necessary inclusive education practices, including knowledge and skills for handling bullying, they may fail to recognize the problem, hold false beliefs about bullying (e.g., victims are often excluded, but at times, they isolate themselves), or deny it to shield themselves from feelings of personal/professional incompetence. However, teachers’ awareness of and sensitivity to this issue may empower them to take proactive efforts in addressing it (D’Urso et al., 2023).

Despite a growing research interest in identifying the factors contributing to teachers’ responses to victimization incidents, the current literature lacks a theoretical foundation for these empirical examinations. To address this concern, Fischer and Bilz (2019a) proposed a conceptual model that systematically organizes the factors influencing teachers’ responses to bullying incidents. This model underscores teachers’ intervention competence as a crucial precursor to their responses, alongside the situational and contextual factors (e.g., types of bullying and the school type). According to this model, teachers’ intervention competence is composed of several dimensions, including knowledge (e.g., knowledge about bullying and accuracy judgment), motivation (e.g., willingness to intervene and self-efficacy), beliefs (e.g., beliefs about normality of bullying), and self-regulation. Among these dimensions, teachers’ self-efficacy assumes a central role, and thus is the focus of the current study.

The concept of teacher self-efficacy is rooted in Bandura’s (1977) social cognitive theory and is defined as “teacher’s belief in his or her capability to organize and execute courses of action required to successfully accomplishing a specific teaching task in a particular context” (Tschannen-Moran et al., 1998, p. 233). Self-efficacy is considered as one of the key beliefs influencing teachers’ motivations and professional behaviors (Durksen et al., 2017). The common thought behind this presumption is that self-efficacious teachers are more task-involved and persistent in the face of obstacles, and thus, are better equipped to take necessary actions in challenging situations. Relatedly, teacher self-efficacy was found to be associated with several desirable outcomes, including high student academic motivation and achievement (Caprara et al., 2006) and less teacher stress and burnout (Schwarzer and Hallum, 2008). However, the existing literature provides a complex picture for the pattern of association between teacher self-efficacy and how teachers intervene with bullying incidents (Fischer S. et al., 2021). Some studies revealed a positive association between teacher self-efficacy and their likelihood of intervention (e.g., Yoon, 2004; Duong and Bradshaw, 2013; Gregus et al., 2017; Fischer and Bilz, 2019b) whereas others reported null findings (e.g., Yoon et al., 2016; De Luca et al., 2019). These mixed findings could be attributed to various reasons, including lack of consensus in the measurement of teacher self-efficacy across studies. Previous research has employed a variety of scales to measure teacher self-efficacy, with some focusing on teachers’ confidence in managing a range of responsibilities within a school context (e.g., meeting teaching objectives, handling discipline problems, and taking advantage of innovations and technologies, De Luca et al., 2019), while others address teachers’ conviction about their competencies in handling classroom misbehaviors or bullying (Gregus et al., 2017). The predictive utility of teacher self-efficacy becomes more pronounced when scales focus on specific and well-defined set of behaviors and circumstances. Most of the null findings come from studies lacking specificity in the measurement of teacher self-efficacy. Considering this key knowledge from the literature, we examined teachers’ intentions to intervene with ethnicity-based victimization by focusing on context-specific teacher efficacy, namely teachers’ efficacy for handling classroom misbehaviors and efficacy for addressing challenges of diversity.

On day-to-day basis, teachers have the opportunity to observe interactions among students and can influence students’ understanding of and approach to those from diverse backgrounds. However, not all teachers are well-prepared in dealing with ethnic and cultural diversity (Bayram Özdemir et al., 2021a). While some teachers may view working with a diverse group of students as an asset, others may hold negative perceptions about ethnic minority students and see them as a problem (Gutentag et al., 2018). Consequently, they may find it challenging to work with diverse populations (Geerlings et al., 2018) and experience higher levels of burnout (Gutentag et al., 2018). Recent studies have shown that the multicultural climate within a school may contribute to teachers’ sense of efficacy in working with diverse student profiles (Ulbricht et al., 2022; Schwarzenthal et al., 2023). For example, teachers were found to feel more confident in handling the challenges of a multicultural classroom and responding effectively to students with different abilities and cultural backgrounds when they perceived a strong emphasis on inclusion and cultural pluralism in their school context. Additionally, they demonstrated a greater sense of efficacy in promoting positive intercultural relations when their school environment appreciated cultural diversity and adhered to a multicultural curriculum (Ulbricht et al., 2022).

Despite an increasing interest in understanding the potential role of teacher self-efficacy in working with culturally diverse school settings, most research focuses on the factors contributing to teachers’ feelings of efficacy. By contrast, far less attention has been paid to understanding how teacher efficacy is related to their behaviors in promoting respect among diverse groups of students. To our knowledge, only two studies examined the link between teachers’ self-efficacy and its impact on their actual practices in culturally diverse classrooms. The first study, conducted in four different European countries, revealed that teachers with higher diversity-related self-efficacy beliefs were more inclined to organize class activities to enhance cultural knowledge, and tended to ensure that class materials reflect cultural diversity, and create a warm and inclusive environment (Romijn et al., 2020). The second study, carried out in Portugal, highlighted that not only cultural/linguistic self-efficacy, but also general self-efficacy was positively linked with teachers’ implementation of intercultural practices (Maio et al., 2022). Based on these findings, it is plausible to argue that a sense of efficacy might empower teachers to oversee the academic and social dynamics within a diverse classroom setting. Consequently, this may contribute to their dedication to finding ways to accommodate the needs of students and align with the socio-cultural context of the schools.

Teacher efficacy may serve as a critical internal factor not only in adopting strategies to foster harmonious relations among diverse groups of students, but also in shaping how teachers respond to negative interactions. However, this is an open question that is studied to a much lesser extent. To address this gap in knowledge, we examined the relative contributions of teachers’ general (i.e., managing disruptive behaviors in class) and diversity-related efficacy (i.e., addressing diversity-related challenges) to the intervention strategies that they employ. Two competing lines of conceptual reasoning can be adopted to explain the relative effect of teachers’ general and diversity-related efficacy (Romijn et al., 2020). One argument could be that there is nothing inherently unique about teachers’ competencies in working with various student populations. As long as teachers possess confidence in managing disruptive behaviors in class, they can apply well-developed conflict resolution skills across different contexts, including handling ethnicity-based victimization incidents at school. The alternative argument could be that intervening with ethnicity-based conflicts among students may require specific knowledge and competencies. Teachers may need to have confidence in their ability to effectively work with diversity related issues at school, e.g., promoting tolerance among students and fostering social integration of students with diverse background. These competencies could instill teachers with the belief that they have the capacity to mitigate negative interactions among a diverse group of students, leading them to invest more time and effort in resolving problems effectively.

In the light of the aforementioned gaps in knowledge, we first examined the extent to which teacher efficacy can be conceptualized as a two-dimensional concept: efficacy for managing disruptive behaviors in the classroom and efficacy for addressing diversity-related issues. Subsequently, we explored how teachers’ general and diversity-related efficacy contribute to their intervention strategies when dealing with ethnic victimization incidents at school. Two competing hypotheses were tested. Based on the universal approach, it was expected that teachers who feel confident in managing disruptive behaviors would likely demonstrate a successful track record of employing effective strategies to address various problematic behaviors in school. Consequently, they would be more inclined to employ proactive intervention strategies (such as contacting parents, providing comfort to the victim, and initiating discussions with colleagues) when addressing incidents of ethnic victimization. Alternatively, based on the situation-specific approach, it was expected that teachers’ diversity-related efficacy would explain how teachers intervene with ethnicity-based victimization incidents to a greater extent than their general efficacy for handling disruptive behaviors.

The sample of this study came from the second-wave of a multi-informant longitudinal study focusing on the role of school context in the development of social relationship among youth with diverse background. The project was implemented in 15 upper-secondary schools in Sweden, and the data from head teachers of 8th grade students (N = 72; 56% females) were included in the analysis of the current study. Most of the teachers (90%) were born in Sweden and reported that they had a formal teaching training (85%). Teachers showed variations in their teaching experience (ranged from 3 months to 39 years, M = 12.83 years, SD = 8.76 years).

The head class teachers were provided with written information describing the purpose of the study. They were also informed that participation was voluntary and that their responses would be confidential. Those who agreed to participate were asked to complete the survey. The study procedures were approved by the Regional Research Ethics Committee in Uppsala.

The Ohio State Teacher Efficacy Scale was used to measure teachers’ feelings of efficacy to handle disruptive behaviors in class (Tschannen-Moran and Hoy, 2001). This original scale consists of three subscales, and the efficacy for classroom management subscale was used in the present study. The subscale items were: “How much can you do to control disruptive behavior in the classroom?” “How much can you do to get students to follow the rules in the classroom?” and “How much can you do to calm a student who is disruptive or noisy?” Teachers were asked to think of their experience as a teacher and answer each of the questions on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (nothing) to 5 (a great deal). The Cronbach’s alpha for this subscale was 0.84.

The Teacher Efficacy Scale for Classroom Diversity was used to measure how efficacious teachers feel when they work in a culturally diverse class (Kitsantas, 2012). The original scale consisted of 10 items. In the current study, we only used 3 items that were related to promoting inclusion and tolerating differences. The scale items were: “You are teaching a diverse class with some students for whom Swedish is a second language. When you teach, you encounter several verbal communication problems that confine comprehension of instructional material and effective discussions in the classroom. How certain are you that you can use strategies that enhance and maintain verbal communication in the classroom?” “You are teaching a class with students from various ethnic backgrounds with different traditions, customs, conventions, and values. You notice that some of your students have trouble tolerating one another’s differences. How certain are you that you can provide your students with opportunities that foster awareness and appreciation of cultural differences?” “You are teaching a diverse class with some students for whom Swedish is a second language. You notice that some of these students feel hesitant to interact with the rest of the class. How certain are you that you can adopt strategies that promote integration of these students?” Teachers were asked to respond to each item on 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.82.

A revised version of the Handling Bullying Questionnaire (HBQ; Bauman et al., 2008) was used to assess teachers’ responses to ethnic victimization incidents. Teachers were presented with a hypothetical scenario describing an incident and were asked how they would respond to such incident. The hypothetical scenario was: “Imagine that you get to see a 13-year-old student being repeatedly teased and called unpleasant names because of her or his appearance, cultural or religious background. As a result, s/he is feeling angry, miserable, and isolated.” The revised HBQ scale includes items tapping into the following strategies: ignoring the situation (3 items; Cronbach’s α = 0.24 “Leave it for someone else to sort out because it is outside your responsibility”), using authority-based interventions (3 items, Cronbach’s α = 78, “Make it clear to the bully that her or his behavior will not be tolerated”), enlisting parents of victims and perpetrators (2 items, Spearman-Brown coefficient = 0.93, “Contact the victim’s parents or guardians to express your concern about their child’s well-being”), discussing collaborative action with other teachers (2 items, Spearman-Brown coefficient = 0.87, “Talk with other teachers, and discuss how to help the student so that s/he does not feel isolated”), and comforting and supporting the victim (3 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.91, “Talk with the victim to understand how s/he feels”). Teachers were asked to report how likely they would adopt described strategies on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (I would absolutely not do it) to 5 (I would definitely do it). The inter-item reliability for ignoring the situation subscale was below the acceptable criteria, thus this scale was not included in the main analysis.

Considering the impact of school ethnic composition on the prevalence of ethnic victimization incidents (Bayram Özdemir and Özdemir, 2020) and teachers’ efficacy in working with diverse student groups (Geerlings et al., 2018), we have controlled for this variable at the school level to ensure more robust conclusions. The percentages of adolescents with Swedish background (i.e., having both parents born in Sweden) in each of the 15 schools were calculated, and these values were used to define school ethic composition. Ethnic composition ranged from 6 to 81% across these 15 schools.

We used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to examine whether general and diversity related efficacy are distinct constructs. Next, multilevel modeling (Hox et al., 2018) with two analytic levels (Level 1: individual, Level 2: school) was estimated in Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2017). First, we examined the proportion of variance of the outcome variables at individual and school level. Next, individual level predictors (i.e., gender, years in teaching, efficacy for classroom management and efficacy for addressing challenges of diversity) were included in the model (Model 1). Finally, we included the school level predictor (i.e., school ethnic composition) in the model (Model 2). The Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) estimation method was applied to estimate the models as this estimation method provides more reliable results (compared to maximum likelihood estimation) when sample sizes are small (van de Schoot et al., 2015). We used group mean centering for all the predictors at the individual level and grand mean centering for the predictor variable at school level (Enders and Tofighi, 2007).

The most frequently employed strategy to intervene ethnic victimization incidents was comforting the victim, followed by discussion with other teachers, using authority-based interventions, and contacting with the parents. More than half of the teachers reported they would definitely adopt authority-based interventions (63%), contact parents of victims and perpetrators (64%), discuss collaborative action with other teachers (69%), or comfort the victim (79%). Male and female teachers did not significantly differ in the levels of employed intervention strategies. Teachers who were born outside of Sweden were more likely to take proactive actions compared to those who were born in Sweden, but this group comparison only reached to statistical significance for enlisting parents. Further, teaching experience was positively correlated with efficacy for handling disruptive behaviors in class, but it was not significantly associated with any of the intervention strategies employed by teachers. Finally, the associations among teachers’ intervention strategies were all in the expected directions (see Table 1).

We estimated a series of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) models to examine whether general and diversity-related self-efficacy beliefs are distinct constructs. Specifically, the following CFA models were estimated: (1) a single-factor model where all efficacy items load onto one latent construct and (2) a two-factor oblique model (the two factors are interrelated). The single factor model showed a very poor fit, χ2(9) = 101.97, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.49, RMSEA = 0.38, p < 0.001, SRMR = 0.19. The oblique model fitted the data, χ2(8) = 12.99, p = 0.11, CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.09, p = 0.20, SRMR = 0.07. These two efficacy constructs were significantly correlated, r = 0.24, p < 0.05. These findings suggest that general and diversity-related efficacy are interrelated, but distinct constructs.

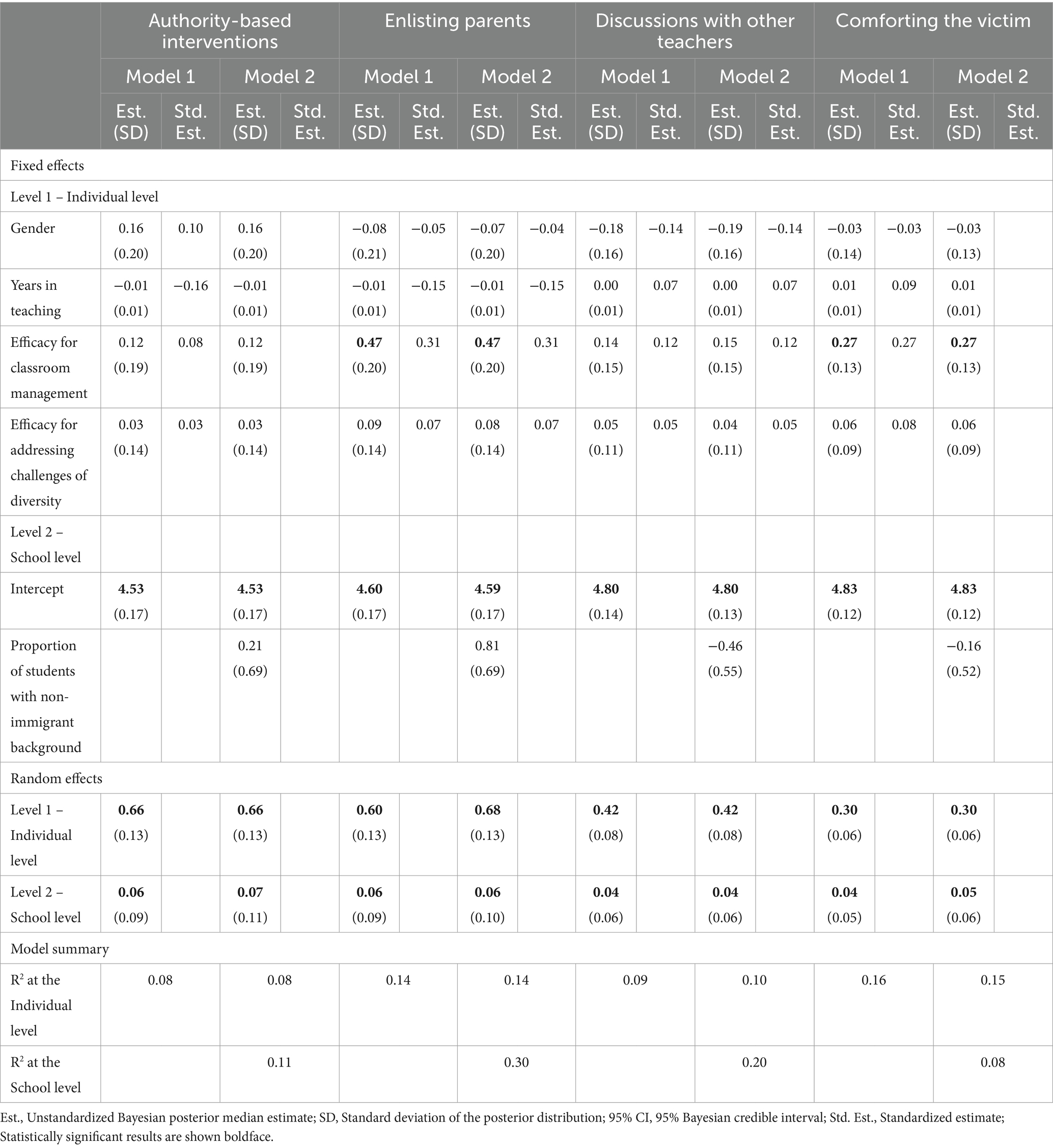

The results of multilevel model showed that variance in teachers’ intervention strategies ranged from 4 to 6% across schools, suggesting the appropriateness of estimating multilevel models to test the research questions. At the individual level, we found that teachers with a high sense of efficacy for class management were more likely to contact parents of victims and perpetrators, and to comfort the victim. However, none of the predictors (i.e., years in teaching, teacher’s gender, efficacy for addressing diversity related issues, and efficacy for classroom management) significantly explained the variation in authority-based interventions and discussions with other teachers. At the school level, we examined whether school ethnic composition played a role in teachers’ intervention strategies. The results revealed null findings, suggesting that school ethnic composition did not significantly contribute to the variation in teachers’ responses to ethnic victimization incidents at school (see Table 2).

Table 2. Individual and school level predictors of teachers’ responses to ethnic victimization incidents.

Increasing political polarization in Europe presents a challenge to fostering positive interactions among youth from diverse backgrounds in schools. Students with immigrant backgrounds face a heightened risk of encountering negative treatment based on their ethnicity, religion, or cultural background (UNESCO, 2019; Rädda Barnen, 2021). Unsurprisingly, these adverse experiences have harmful consequences for the adjustment and integration of immigrant and minority adolescents (Marks et al., 2015; Benner et al., 2018). This growing issue highlights the need for a systematic empirical understanding of how schools, particularly teachers, respond to this social concern and the factors influencing their actions (Bayram Özdemir et al., 2021b). To address this need in knowledge, we aimed to understand how teachers address ethnic victimization incidents at school, and the extent to which their efficacy contributes to their intended actions.

Our results indicate that teachers adopt a diverse range of strategies to address incidents of ethnic victimization, with certain strategies being more commonly employed than others. This finding suggests that teachers may view intervention efforts against victimization incidents as a multidimensional phenomenon, involving the victim, perpetrator, parents, and staffs at school (Burger et al., 2015; Bayram Özdemir et al., 2021b). Additionally, it highlights that teachers may perceive certain intervention efforts as more urgent and necessary. Notably, our findings show that teachers prioritize comforting the victim as the most essential action. This finding diverges from prior research focused on general bullying or victimization, which emphasizes authority-based interventions and working with bullies as teachers’ primary strategies (Burger et al., 2015). This contradictory finding could be attributed to various reasons. One possible explanation could be that teachers may view ethnic victimization as involving complex dynamics. They might need a comprehensive understanding to implement broader interventions that address the multifaceted nature of this issue. Thus, they may prioritize comforting the victim as a crucial step before implementing broader interventions to tackle this problem. Alternatively, this finding may also be tied to the perception among teachers that ethnic victimization incidents are more serious, leading them to consider ethnically victimized students as especially vulnerable and in need of immediate emotional support. These beliefs could prompt teachers to acknowledge the importance of addressing the emotional well-being of the victim as a crucial aspect of effectively managing such situations.

The results also underscore that teachers’ gender does not influence the extent of their intervention strategies, while their immigrant background does. Teachers with immigrant backgrounds reported a higher likelihood of taking proactive actions, particularly in enlisting parents. This finding could potentially be explained by the Social Identity Theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1979), which posits that individuals with shared social identities may possess greater insight into the values and experiences of others within the same group. In the context of this study, teachers with immigrant backgrounds may better empathize with students experiencing minority stress and understand their encounters in society (Magaldi et al., 2018). This heightened awareness may help teachers not trivialize the problem, but rather become more sensitive to students’ needs. Consequently, these teachers may be more inclined to contact parents and raise awareness of students’ situations, thus activating a stronger support system for the students.

A noteworthy finding of the present study is that teachers’ efficacy in handling disruptive behaviors in class, rather than their efficacy in dealing with diversity-related issues (e.g., promoting inclusion and tolerating differences) explains their responses to victimization incidents, particularly in terms of comforting the victims and enlisting parents. This finding aligns with previous research indicating that teachers’ general efficacy (i.e., general sense of capability to deal with challenging situations and disruptive behaviors) was more strongly associated with their implementation of intercultural practices (Maio et al., 2022). However, it contradicts with another study emphasizing the role of diversity-related self-efficacy in fostering teachers’ intercultural practices in the classroom (Romijn et al., 2020). As previously discussed, efficacy in handling disruptive behaviors is a primary competence that can strengthen teachers’ ability to navigate the academic and social dynamics in the classroom and intervene effectively. When teachers possess confidence in their ability to manage challenging situations, this competence may enhance their ability to address the needs of their students across various situations, including incidents of ethnic victimization. In contrast, efficacy for dealing with diversity-related issues seems not to be sufficient by itself to contribute to teachers’ responses to ethnic victimization incidents. Efficacy in dealing with diversity related issues could have an additive effect for effectively intervening in problematic situations in a diverse school context, alongside general efficacy. Future studies with a large sample size could employ person centered approach and classify teachers based on their general and diversity-related efficacy. Such examination would enable us to draw stronger conclusions regarding the potential role of diversity-related efficacy in teachers’ intervention strategies.

Interestingly, our findings also indicate that school ethnic composition does not significantly affect teachers’ intervention strategies. In other words, teachers display similar responses to ethnic victimization incidents across schools with diverse ethnic compositions. This is a promising finding, and underscores the significance of prioritizing the social dynamics and climate within schools rather than focusing solely on the demographic makeup of the student body. This argument aligns with broader research in the realms of general bullying and victimization, which emphasizes the influential role of school social climate on teachers’ likelihood of intervention and their responses to various bullying incidents (Yoon et al., 2016; Kollerová et al., 2021; Waasdorp et al., 2021) and hate postings (Strohmeier and Gradinger, 2021). For instance, Yoon et al. (2016) showed that teachers perceiving their school climate as hostile were twice as likely to discipline bullies and involve other adults compared to those with a different perception. Additionally, Strohmeier and Gradinger (2021) found that teachers were more prone to overlook hate postings in the absence of clear school guidelines. On the contrary, Waasdorp et al. (2021) pointed out that teachers, when trained on their schools’ anti-bullying policy, demonstrated an increased likelihood of intervening with the involved students, engaging in discussions about the incident with other school staff, and referring the students to school counselors. In summary, our findings, coupled with existing empirical evidence, underscore the necessity of cultivating a nuanced understanding of the social characteristics of schools to comprehend how teachers respond to incidents of ethnic victimization.

Despite its important contributions to the literature, several limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. First, we assessed teachers’ responses to ethnic victimization using a hypothetical vignette like other studies in this field (e.g., Kollerová et al., 2021; Strohmeier and Gradinger, 2021). There is a possibility that these responses may not fully capture the range of responses that teachers would exhibit in a real situation. Thus, the findings presented here allow us to draw conclusions about teachers’ intended actions rather than their actual behaviors. Future studies using qualitative research methodology where teachers are asked to recall recent incidents that they have witnessed would provide a more nuanced understanding of their actions, and to some extent mitigate potential social desirability effects. Second, the sample size in the present study was relatively small, which may result in missing some possible effects. To address this issue, we have employed Bayesian estimation, a method known to provide reliable results in small sample sizes (van de Schoot et al., 2015). However, we should acknowledge that the conclusions drawn from this study need to be interpreted considering this limitation. Third, we investigated teachers’ efficacy as a possible precursor to their actions. However, it is essential to note that the relation between teacher efficacy and practice is reciprocal by nature, and efficacy beliefs can work as self-fulfilling prophecies (Tschannen-Moran et al., 1998). Relatedly, future studies using longitudinal data should examine the bidirectional association between teachers’ efficacy and their intervention strategies in response to ethnic victimization incidents, and the possible consequences of these responses on the victims (Bayram Özdemir et al., 2021b), and the future behaviors of the perpetrators. Finally, it is important to acknowledge that teachers’ responses to instances of ethnic victimization may be influenced by factors beyond their self-efficacy beliefs, including their attitudes toward diversity, beliefs about the normality of such incidents, and the accuracy of their judgment. Developing a comprehensive, empirically-based understanding of the factors that promote or hinder teachers’ proactive efforts to intervene in incidents of ethnic victimization would enable us to implement effective strategies in schools.

In conclusion, the present study was one of the pioneering efforts to explore how teachers address ethnic victimization incidents in schools. It underscores that more than half of the teachers express an intention to proactively intervene in these issues by adopting various strategies, including targeted actions and broader interventions through collaboration with other teachers and parents, which is a promising finding. Increasing awareness among teachers about the precursors and consequences of this problem may have the potential to further enhance their proactive actions. The findings of the present study also highlight the importance of providing teachers with necessary support, such as offering professional development workshops (Waasdorp et al., 2021) and fostering communication and collaboration among teachers (Kollerová et al., 2021), to enhance their confidence in classroom management. Importantly, this confidence appears to contribute to the development of strategies aimed at comforting the victim and effectively communicating with the parents of the involved students.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because participants did not consent to making the data publicly available. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Regional Research Ethics Committee in Uppsala. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided verbal informed consent to participate.

SB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – original draft. MÖ: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The work was supported by the Swedish Research Council (2015-01057).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 84, 191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Barrett, M. (2018). How schools can promote the intercultural competence of young people. Eur. Psychol. 23, 93–104. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000308

Bauman, S., Rigby, K., and Hoppa, K. (2008). US teachers’ and school counsellors' strategies for handling school bullying incidents. Educ. Psychol. 28, 837–856. doi: 10.1080/01443410802379085

Bayram Özdemir, S., Lundberg, E., and Özdemir, M. (2021a). “Hur kan lärare främja positiva interetniska relationer i skolan? Förutsättningar, strategier och utmaningar” in Ungas uppväxtvillkor och integration. eds. S. Thalberg, A. Asplund, and D. Silberstein (Kortrijk: Delmi), 137–164.

Bayram Özdemir, S., and Özdemir, M. (2020). The role of perceived inter-ethnic classroom climate in adolescents’ engagement in ethnic victimization: for whom does it work? J. Youth Adolesc. 49, 1328–1340. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01228-8

Bayram Özdemir, S., Özdemir, M., and Elzinga, A. E. (2021b). Psychological adjustment of ethnically victimized adolescents: do teachers’ responses to ethnic victimization incidents matter? Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 18, 848–864. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2021.1877131

Benner, A. D., Wang, Y., Shen, Y., Boyle, A. E., Polk, R., and Cheng, Y. P. (2018). Racial/ethnic discrimination and well-being during adolescence: a meta-analytic review. Am. Psychol. 73, 855–883. doi: 10.1037/amp0000204

Burger, C., Strohmeier, D., Spröber, N., Bauman, S., and Rigby, K. (2015). How teachers respond to school bullying: an examination of self-reported intervention strategy use. Moderator effects, and concurrent use of multiple strategies. Teach. Teach. Educ. 51, 191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.07.004

Campaert, K., Nocentini, A., and Menesini, E. (2017). The efficacy of teachers’ responses to incidents of bullying and victimization: the mediational role of moral disengagement for bullying. Aggress. Behav. 43, 483–492. doi: 10.1002/ab.21706

Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Steca, P., and Malone, P. S. (2006). Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs as determinants of job satisfaction and students' academic achievement: a study at the school level. J. Sch. Psychol. 44, 473–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2006.09.001

D’Urso, G., Fazzari, E., La Marca, L., and Simonelli, C. (2023). Teachers and inclusive practices against bullying: a qualitative study. J. Child Fam. Stud. 32, 2858–2866. doi: 10.1007/s10826-022-02393-z

De Luca, L., Nocentini, A., and Menesini, E. (2019). The teacher’s role in preventing bullying. Front. Psychol. 10:1830. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01830

Duong, J., and Bradshaw, C. P. (2013). Using the extended parallel process model to examine teachers' likelihood of intervening in bullying. J. Sch. Health 83, 422–429. doi: 10.1111/josh.12046

Durksen, T. L., Klassen, R. M., and Daniels, L. M. (2017). Motivation and collaboration: the keys to a developmental framework for teachers’ professional learning. Teach. Teach. Educ. 67, 53–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.05.011

Enders, C. K., and Tofighi, D. (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: a new look at an old issue. Psychol. Methods 12, 121–138. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121

Farmer, T. W., Lines, M. M., and Hamm, J. V. (2011). Revealing the invisible hand: the role of teachers in children's peer experiences. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 32, 247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2011.04.006

Fischer, S. M., and Bilz, L. (2019a). Is self-regulation a relevant aspect of intervention competence for teachers in bullying situations? Nordic Stud. Educ. 39, 121–141. doi: 10.18261/issn.1891-5949-2019-02-04

Fischer, S. M., and Bilz, L. (2019b). Teachers’ self-efficacy in bullying interventions and their probability of intervention. Psychol. Sch. 56, 751–764. doi: 10.1002/pits.22229

Fischer, S., John, N., and Bilz, L. (2021). Teachers’ self-efficacy in preventing and intervening in school bullying: a systematic review. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 3, 196–212. doi: 10.1007/s42380-020-00079-y

Fischer, S. M., Wachs, S., and Bilz, L. (2021). Teachers’ empathy and likelihood of intervention in hypothetical relational and retrospectively reported bullying situations. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 18, 896–911. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2020.1869538

Garandeaut, C. F., Vartio, A., Poskiparta, E., and Salmivalli, C. (2016). School bullies’ intention to change behavior following teacher interventions: effects of empathy arousal, condemning of bullying, and blaming of the perpetrator. Prev. Sci. 17, 1034–1043. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0712-x

Geerlings, J., Thijs, J., and Verkuyten, M. (2018). Teaching in ethnically diverse classrooms: examining individual differences in teacher self-efficacy. J. Sch. Psychol. 67, 134–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2017.12.001

Green, S., Shriberg, D., and Farber, S. (2008). What’s gender got to do with it? Teachers’ perceptions of situation severity and requests for assistance. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 18, 346–373. doi: 10.1080/10474410802463288

Gregus, S. J., Rodriguez, J. H., Pastrana, F. A., Craig, J. T., McQuillin, S. D., and Cavell, T. A. (2017). Teacher self-efficacy and intentions to use antibullying practices as predictors of children's peer victimization. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 46, 304–319. doi: 10.17105/SPR-2017-0060.V46-3

Gutentag, T., Horenczyk, G., and Tatar, M. (2018). Teachers’ approaches toward cultural diversity predict diversity-related burnout and self-efficacy. J. Teach. Educ. 69, 408–419. doi: 10.1177/0022487117714244

Hektner, J. M., and Swenson, C. A. (2012). Links from teacher beliefs to peer victimization and bystander intervention: tests of mediating processes. J. Early Adolesc. 32, 516–536. doi: 10.1177/0272431611402

Hox, J., Moerbeek, M., and van de Schoot, R. (2018). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. 3rd Edn. New York: Routledge.

Huang, F. L., Lewis, C., Cohen, D. R., Prewett, S., and Herman, K. (2018). Bullying involve- ment, teacher–student relationships, and psychosocial outcomes. Sch. Psychol. Q. 33, 223–234. doi: 10.1037/spq0000249

Kollerová, L., Soukup, P., Strohmeier, D., and Caravita, S. C. (2021). Teachers’ active responses to bullying: does the school collegial climate make a difference? Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 18, 912–927. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2020.1865145

Magaldi, D., Conway, T., and Trub, L. (2018). “I am here for a reason”: minority teachers bridging many divides in urban education. Race Ethn. Educ. 21, 306–318. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2016.1248822

Maio, R., Guichard, S., and Cadima, J. (2022). In what conditions are intercultural practices implemented in disadvantaged and diverse settings in Portugal? Associations with professional and organization-related variables. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 25, 509–534. doi: 10.1007/s11218-022-09687-6

Marks, A. K., Ejesi, K., McCullough, M., and Garcia Coll, C. (2015). “Developmental implications of discrimination” in Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Socioemotional processes. eds. M. Lamb, C. G. Coll, and R. Lerner. 7th ed (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley), 324–365.

Marshall, M. L., Varjas, K., Meyers, J., Graybill, E. C., and Skoczylas, R. B. (2009). Teacher responses to bullying: self-reports from the front line. J. Sch. Violence 8, 136–158. doi: 10.1080/15388220802074124

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user's guide. 8th Edn. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Paljakka, A. (2023). Teachers’ awareness and sensitivity to a bullying incident: a qualitative study. Int. J. Bullying Prev., 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s42380-023-00185-7

Romijn, B. R., Slot, P. L., Leseman, P. P., and Pagani, V. (2020). Teachers’ self-efficacy and intercultural classroom practices in diverse classroom contexts: a cross-national comparison. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 79, 58–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2020.08.001

Schwarzenthal, M., Daumiller, M., and Civitillo, S. (2023). Investigating the sources of teacher intercultural self-efficacy: a three-level study using TALIS 2018. Teach. Teach. Educ. 126:104070. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2023.104070

Schwarzer, R., and Hallum, S. (2008). Perceived teacher self-efficacy as a predictor of job stress and burnout: mediation analyses. Appl. Psychol. 57, 152–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00359.x

Strohmeier, D., and Gradinger, P. (2021). Teachers’ knowledge and intervention strategies to handle hate-postings. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 18, 865–879. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2021.1877130

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. (1979). “An integrative theory of intergroup conflict” in The social psychology of intergroup relations. eds. W. G. Austin and S. Worchel (Monterey, CA: Brooks-Cole), 33–47.

Torney-Purta, J. (2002). The school’s role in developing civic engagement: a study of adolescents in twenty-eight countries. Appl. Dev. Sci. 6, 203–212. doi: 10.1207/S1532480XADS0604_7

Tschannen-Moran, M., and Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: capturing an elusive construct. Teach. Teach. Educ. 17, 783–805. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1

Tschannen-Moran, M., Hoy, A. W., and Hoy, W. K. (1998). Teacher efficacy: its meaning and measure. Rev. Educ. Res. 68, 202–248. doi: 10.3102/00346543068002202

Ulbricht, J., Schachner, M. K., Civitillo, S., and Noack, P. (2022). Teachers’ acculturation in culturally diverse schools-how is the perceived diversity climate linked to intercultural self-efficacy? Front. Psychol. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.953068

van de Schoot, R., Broere, J. J., Perryck, K. H., Zondervan-Zwijnenburg, M., and Van Loey, N. E. (2015). Analyzing small data sets using Bayesian estimation: the case of posttraumatic stress symptoms following mechanical ventilation in burn survivors. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 6. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v6.25216

van Gils, F. E., Colpin, H., Verschueren, K., Demol, K., Ten Bokkel, I. M., Menesini, E., et al. (2022). Teachers’ responses to bullying questionnaire: a validation study in two educational contexts. Front. Psychol. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.830850

Waasdorp, T. E., Fu, R., Perepezko, A. L., and Bradshaw, C. P. (2021). The role of bullying-related policies: understanding how school staff respond to bullying situations. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 18, 880–895. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2021.1889503

Wachs, S., Bilz, L., Niproschke, S., and Schubarth, W. (2019). Bullying intervention in schools: a multilevel analysis of teachers’ success in handling bullying from the students’ perspective. J. Early Adolesc. 39, 642–668. doi: 10.1177/0272431618780423

Yoon, J. S. (2004). Predicting teacher interventions in bullying situations. Educ. Treat. Child., 37–45.

Yoon, J., and Bauman, S. (2014). Teachers: a critical but overlooked component of bullying prevention and intervention. Theory Pract. 53, 308–314. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2014.947226

Keywords: ethnic victimization, teachers’ responses to ethnic victimization, teachers’ responses to bias-based bullying, immigrant youth, ethnic bullying

Citation: Bayram Özdemir S and Özdemir M (2024) Unveiling the black box: exploring teachers’ approaches to ethnic victimization incidents at school. Front. Educ. 9:1347816. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1347816

Received: 04 December 2023; Accepted: 04 April 2024;

Published: 21 May 2024.

Edited by:

Hildegunn Fandrem, University of Stavanger, NorwayReviewed by:

Frosso Motti, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, GreeceCopyright © 2024 Bayram Özdemir and Özdemir. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sevgi Bayram Özdemir, c2V2Z2kuYmF5cmFtLW96ZGVtaXJAb3J1LnNl

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.