- Department of Psychology, A’Sharqiyah University, Ibra, Oman

Attitudes are crucial in education, impacting students’ motivation, engagement, and achievement. This study explored Omani high schoolers’ attitudes towards learning English and the differences in their attitudes per their demographics and other variables. The Attitudes Toward English scale was used with 576 students. The findings showed that the students’ attitudes were mildly positive and that significant differences also emerged. Private school and science-track students showed more positive attitudes than government school and humanities students. Supplementary training also improved their attitudes, and parental education levels positively predicted their attitudes. More favorable attitudes strongly correlated with higher English achievement, indicating a need to nurture positive perspectives. The study provided insights into Omani students’ attitudes toward English and showed that fostering positivity might enhance students’ motivation, proficiency, and outcomes. Further research can evaluate interventions for shaping students’ constructive attitudes.

Introduction

Attitudes are relatively enduring beliefs, feelings, and behavioral tendencies toward specific objects, events, or concepts (Davis, 2018). In the context of education, attitudes play an integral role in the affective domain, carrying significance comparable to that of the cognitive and skill domains (Smith, 2020). An individual’s attitudes are fairly stable and can be quantified through surveys or specialized tests (Williams, 2019). The impact of attitudes on learning is substantial; a favorable attitude toward a subject facilitates easier comprehension and engagement, while an unfavorable attitude can impede learning (Jones, 2021). Recognizing the importance of attitudes, educators, and researchers can develop plans grounded in scientific principles and methods to foster positive attitudes through precise, objective interventions (Anderson et al., 2022).

Examining and quantifying students’ attitudes toward academic subjects is critical in education and psychology, particularly for topics with complex content or terminology (Hassan, 2021). Students’ attitudes also elucidate instructors’ inquiries about their student’s academic performance, engagement, and success in meeting course objectives (Lee and Katherine, 2019). For Arab students, English is one of the most crucial subjects because it is foreign to Arab culture, not an inherent part of their legacy or identity (Alkhateeb, 2020). Many Arab students struggle with English due to negative attitudes stemming from a lack of relevance to their cultural background (Jabbar et al., 2017). Measuring Arab students’ attitudes toward studying English can reveal barriers to proficiency and inform teaching methods to improve their motivation and achievement (Kirkpatrick and Al-Batal, 2022).

Language proficiency is fundamental to educational success at all levels (Clement and Murugavel, 2018). Strong linguistic abilities enable students to excel academically by enhancing their comprehension of course content and ability to meet learning objectives. This linguistic advantage extends beyond individual courses to benefit students across various college majors. Moreover, in the professional world, English language skills are often a prerequisite for many career opportunities, potentially expanding employment prospects for proficient speakers. Visser (2008) posits that an individual’s attitudes towards a language significantly impact linguistic achievement. Consequently, developing positive attitudes in language learners can improve outcomes, while negative attitudes may hinder progress. Lee (2022) supports this notion, suggesting that fostering a positive attitude toward language learning enhances students’ motivation, engagement, and overall proficiency. Educators can potentially create pathways to boost academic and professional success by evaluating and addressing students’ attitudes toward language learning. This relationship between attitudes and performance is further reinforced by Alsoudi and AlHarthy (2024), who found a strong positive correlation between students’ attitudes and academic achievements.

Previous studies

Various studies have examined non-native students’ attitudes towards learning English across different contexts, though influenced by several factors. They revealed that attitudes are affected by a range of variables. Sex differences in attitudes have been observed, but findings are inconsistent across studies. While Soleimani and Hanafi (2013) found male students to have more favorable attitudes, Al-Zoubi (2013) reported that female students showed significantly more positive attitudes than males. In both studies, the general attitude was positive. The type of educational track influences attitudes. Liu and Chen (2015), in a study of 155 Taiwanese high school students, found that academic-track students had significantly higher extrinsic, overall motivation, and positive attitudes to learning English than vocational-track students. School types also play a role (Kesgin and Arslan, 2015), in their study of 350 students from 7 different high schools in Turkey, reported that private schools often demonstrated more positive attitudes than public schools. Parental education arises as another significant factor. Kesgin and Arslan (2015) found that students whose parents had higher education levels (bachelor’s or postgraduate degrees) showed more positive attitudes towards English than those with only primary or secondary education. Interestingly, exposure to English outside school affects attitudes positively. Bailly (2011) found that students with more English learning experience outside school tended to have lower anxiety and more positive attitudes towards the language. These studies collectively highlight the complex interplay of variables influencing students’ attitudes toward learning English, including educational track, school type, parental education, sex, and extra exposure to the language.

In Oman, English education has gained prominence since the 1970s, with major curriculum reforms in the late 1990s (Al-Issa and Al-Bulushi, 2012). However, Omani students still face challenges in English proficiency in higher education and the workforce. Unlike some Gulf neighbors, Oman maintains Arabic as the primary language in public schools, potentially influencing students’ attitudes toward English (Al-Issa, 2020). Cultural factors, including the emphasis on Omani identity and limited everyday use of English outside urban areas, further shape these attitudes (Al-Jardani, 2012). While studies in other Arab countries show generally positive attitudes toward English, research specifically on Omani students’ attitudes across different educational levels and regions is limited (Al-Mahrooqi, 2012). This study addresses this gap by examining Omani high school students’ attitudes towards English learning, considering previously unexplored factors such as sex, school type, and parental education levels within the Omani context.

The problem of the study and its questions

Omani students seem to encounter serious difficulties in learning English despite the many procedures carried out by the Ministry of Education in the Sultanate of Oman, including modifying and developing curricula and proposing new evaluation methods and criteria. However, the problem of low academic achievement in English still exists. A study conducted by Al-Maamari (2013) on weak academic achievement in English showed students’ widespread weakness in critical subjects such as Arabic, English, and Mathematics. This weakness is cumulative as students move from a lower stage to a higher one while suffering from reading and writing weaknesses, making overcoming these weaknesses difficult at advanced stages. A study carried out by Abbas and Iqbal (2018) also indicated a close relationship between the degree of students’ attitudes towards English and their level of passing the course. The more positive the attitude, the higher the level the student achieves in the English language course. This, in turn, raises the question of whether the Omani environment faces a similar problem regarding students’ attitudes toward English and whether students’ attitudes affect passing the English course and achieving its objectives.

Investigating the low academic achievement of students in English has become so important that it cannot be ignored or overlooked due to the difficulties that students face after graduating with the general diploma and moving to university or work. Therefore, it is important to examine Omani students’ attitudes to uncover potential barriers or negative perspectives they may hold. With this in mind, the study seeks to answer the following questions:

1. What are the attitudes of post-basic education students in the Sultanate of Oman towards the English language?

2. Are any statistically significant differences in students’ attitudes towards the English language attributable to sex, academic track, parents’ education level, school type, and attending English language training courses?

3. What is the relationship between the students’ academic achievement in English and their attitudes towards learning English?

Method

Population

The study population consisted of 11th-grade students in North Al Sharqiyah Governorate and Muscat Governorate in Oman during the second semester of the 2022–2023 academic year.

Sample

The study sample included 576 students from the population. This comprised 308 male students (155 at public schools studying humanities, 50 at public schools studying science, 30 at private schools studying science, and 25 at private schools studying humanities) and 268 female students (145 at public schools studying science, 50 at public schools studying humanities, 25 at private schools studying science and 20 private schools studying humanities). The students were selected from 10 schools across the two governorates using cluster sampling. The total sample of 576 students consisted of 376 in government and 200 in private schools. Moreover, about the academic track, the sample had 294 science track students and 282 humanities track students. The sample’s mean score in English in the first semester was 75.29, with a standard deviation of 15.23; these scores were used as the academic achievement variable.

Instrument

To achieve the study objectives, the Scale of Students’ Attitudes Toward the English Language developed by ALHarthy and Alsoudi (2023) was used after its psychometric properties were verified. The scale consisted of 11 graded items using Thurstone’s method of equal appearing intervals, distributed across 11 categories ranging from the highest degree of negative attitude (category 1) to the highest degree of positive attitude (category 11), with the neutral point at category 6. Categories 1 to 5 are negative, category 6 is neutral, and categories 7 to 11 are positive. Example items include Category 1 (Most negative): “Studying English is a waste of time”; Category 6 (Neutral): “Learning English is neither enjoyable nor unpleasant”; Category 11 (Most positive): “I feel proud when I speak English fluently.” Students were presented with all 11 items and asked to respond with “yes” or “no” to each. The scoring process involved pre-assigning weights corresponding to each item’s category number (1–11), awarding the corresponding weight for each “yes” response and zero for “no” responses, and calculating the median of the weights for all “yes” responses to determine the student’s overall attitude score. For example, if a student responded “yes” to items in categories 7, 9, and 11, their attitude score would be the median of these values: 9. This approach, using pre-assigned weights based on item categories, allows for a nuanced measurement of attitudes across the spectrum from negative to positive. The median of the graded values of the chosen items was calculated to indicate the student’s attitude toward English.

ALHarthy and Alsoudi (2023) verified the scale’s psychometric properties. The validity results showed that the Point Biserial correlation coefficients between the item score and the total score on the scale ranged between (0.31 and 0.59), all statistically significant at the significance level (0.01). The exploratory factor analysis results indicated a single dimension in the scale, which accounted for about 23% of performance on the scale. All items were loaded on the scale, with factor loadings ranging between (0.36 and 0.71). Reliability was verified in two ways: internal consistency reliability using the Split-Half method, where the scale was divided into two halves, and the Spearman-Brown correlation coefficient, calculated between the halves. The first half included five negative items, while the second half included five positive items. The split-half reliability coefficient was (0.81). To calculate Test–retest reliability, the scale was applied to the participants and reapplied after 1 week; the reliability coefficient reached (0.80). The scale’s psychometric properties indicated good validity and reliability, and its results could be relied upon.

In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha and split-half reliability were verified and reached (0.82 and 0.78), respectively. Point Biserial correlation coefficients were also calculated between the item score and the total score on the scale ranging between (0.37 and 0.61). This indicates that the scale retains its original psychometric properties.

Data analysis

Several analyses were performed to examine the students’ overall attitudes and differences based on demographic factors and the relationship between attitudes and academic achievement. Frequencies, means, standard deviations, t-tests, ANOVA, and regression were utilized to provide insights into the attitudes of the 576 students. Effect sizes were calculated to assess the practical significance of the mean differences. In addition, the assumption of a normal distribution of the study data was verified, and its results indicated that this assumption was achieved (D = 0.048, df = 576, p = 0.20). The assumption of homogeneity of variance was also examined according to Levene’s test. Its results indicated that the variance was equal according to the groups of the father’s educational qualification (F = 1.86, df1 = 3, df2 = 572, p = 0.135) and the mother’s educational qualification (F = 2.44, df1 = 3, df2 = 572, p = 0.063).

Results

The results section presents the key findings from the statistical analyses to address the research questions about high school students’ attitudes toward the English language. Below is a presentation of the study results:

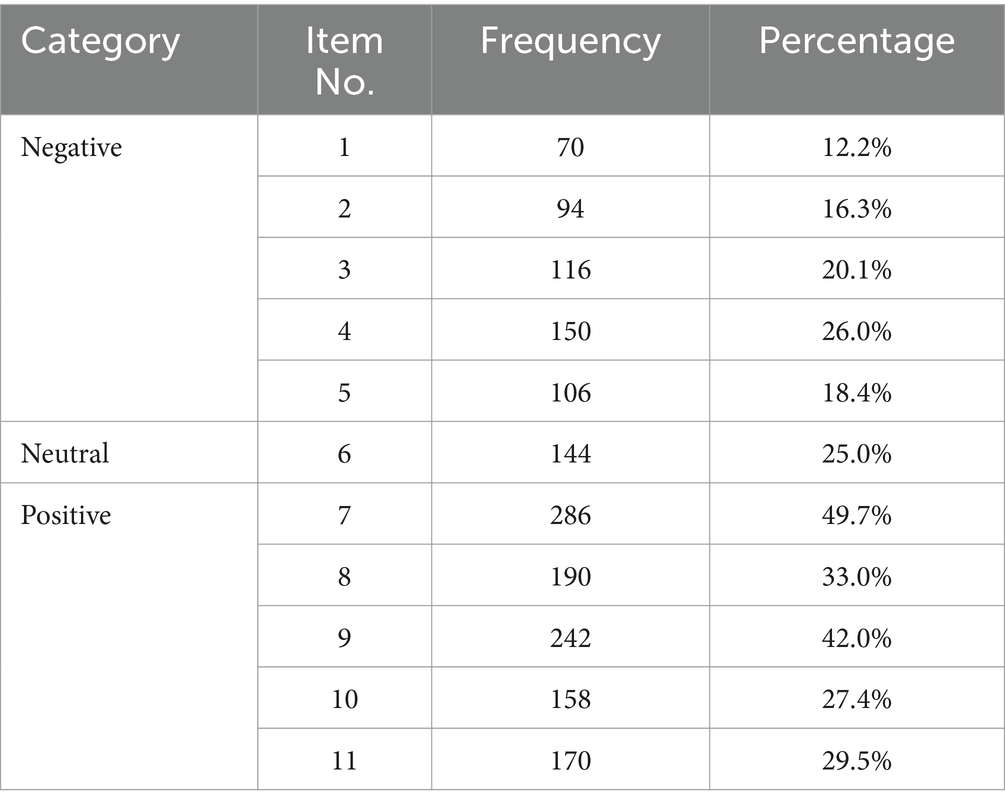

This shows the frequency and percentage of the total valid responses to the 11 items. The highest selected option was 7 (49.7%) and the lowest was 1(12.2%). Table 1 shows the frequencies and percentages for the items chosen from the scale.

The statistical results from the sample of 576 students show that their average attitude rating was 6.73, which is slightly but significantly higher than the neutral value of 6 by one sample t-test (t = 7.09, df = 575, p < 0.001) with a small effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.30). This indicates that the students’ opinions leaned somewhat in the positive direction. However, the standard deviation 2.50 reflects substantial diversity in the students’ perspectives. While the mean difference of 0.73 from the neutral point is statistically significant, the effect size is small, and the confidence interval of 0.53 to 0.94 suggests that the true mean lies within about 0.5 to 0.9 above neutral. These results indicate that the students’ attitudes were mildly positive on average compared to a neutral stance.

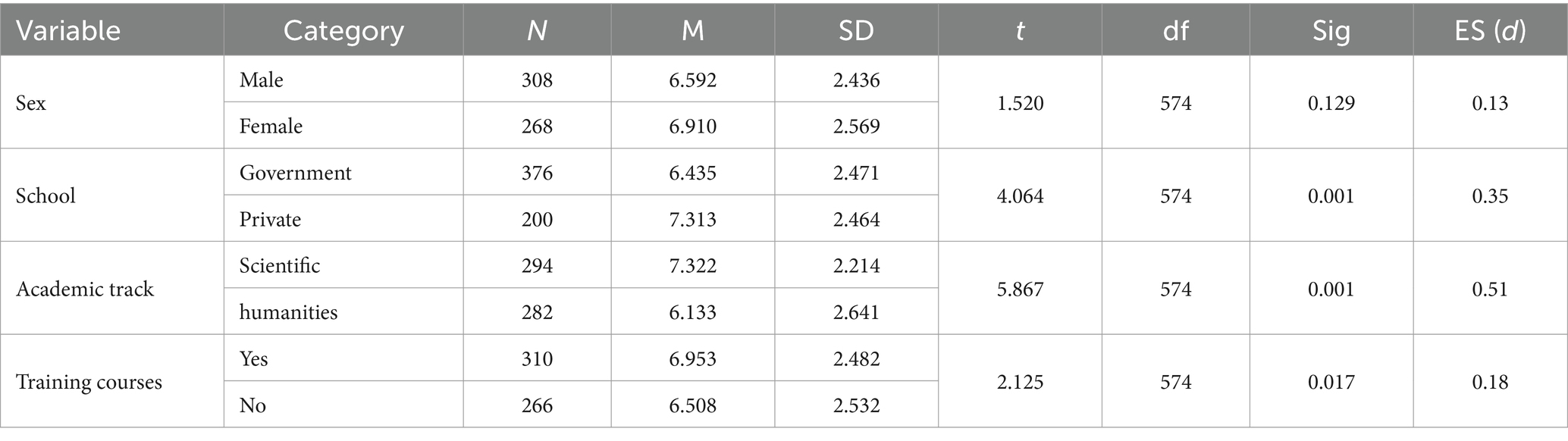

To examine the differences in the students’ attitudes according to the study variables (sex, school type, academic track, and training courses), an independent samples t-test was used, as shown in Table 2. In addition to the t-test results, Cohen’s d was calculated to measure the effect size of these differences. The sample included 308 male students with a mean rating of 6.59 (SD = 2.43) and 268 female students with a mean of 6.90 (SD = 2.56). The t-test result (t = 1.52, df = 574, p = 0.129) was not statistically significant, indicating no significant difference between the male and female students in their average attitude ratings. The mean difference between both sexes was-0.31. These results suggest that sex did not significantly affect the student’s attitudes, as the averages for the male and female students did not differ statistically based on this sample.

A t-test was conducted to compare students’ attitude ratings regarding school type (government vs. private). The sample included 376 government school students with a mean rating of 6.43 (SD = 2.47) and 200 private school students with a mean of 7.31 (SD = 2.46). The t-test result (t = −4.06, df = 574, p < 0.001) was statistically significant, indicating that the private school students had significantly higher average attitude ratings than the government school students. The mean difference was-0.87. The effect size was small, d = 0.35. In summary, school type had a significant but small effect on students’ attitudes, with the private school students recording higher average ratings than the government school students in this sample.

Additionally, a t-test was conducted to compare the students’ attitude ratings as per academic track (science vs. humanities). The sample included 294 science track students with a mean rating of 7.32 (SD = 2.21) and 282 humanities track students with a mean of 6.13 (SD = 2.64). The t-test result (t = 5.86, df = 574, p < 0.001) was statistically significant, indicating that science track students had significantly higher average ratings than humanities track students. The mean difference was 1.18. The effect size d = 0.51 was medium. So, the academic track has a significant medium-sized effect on the student’s attitudes, with the science track students exhibiting higher average ratings than the humanities track students in this sample.

As for the variable of attending training courses, the students who had taken training courses showed a more positive attitude towards English than those who had not. The mean orientation score for the students who had attended training was 7.15, while the mean for those without training was lower at 6.79. An independent samples t-test showed this difference was statistically significant (t = 2.08, df = 574, p = 0.022). The students who had attended training courses reported significantly higher orientation towards English than those who had no training. The effect size for this difference was small, d = 0.18. Overall, training courses seem to be linked to students’ more favorable attitudes towards learning English.

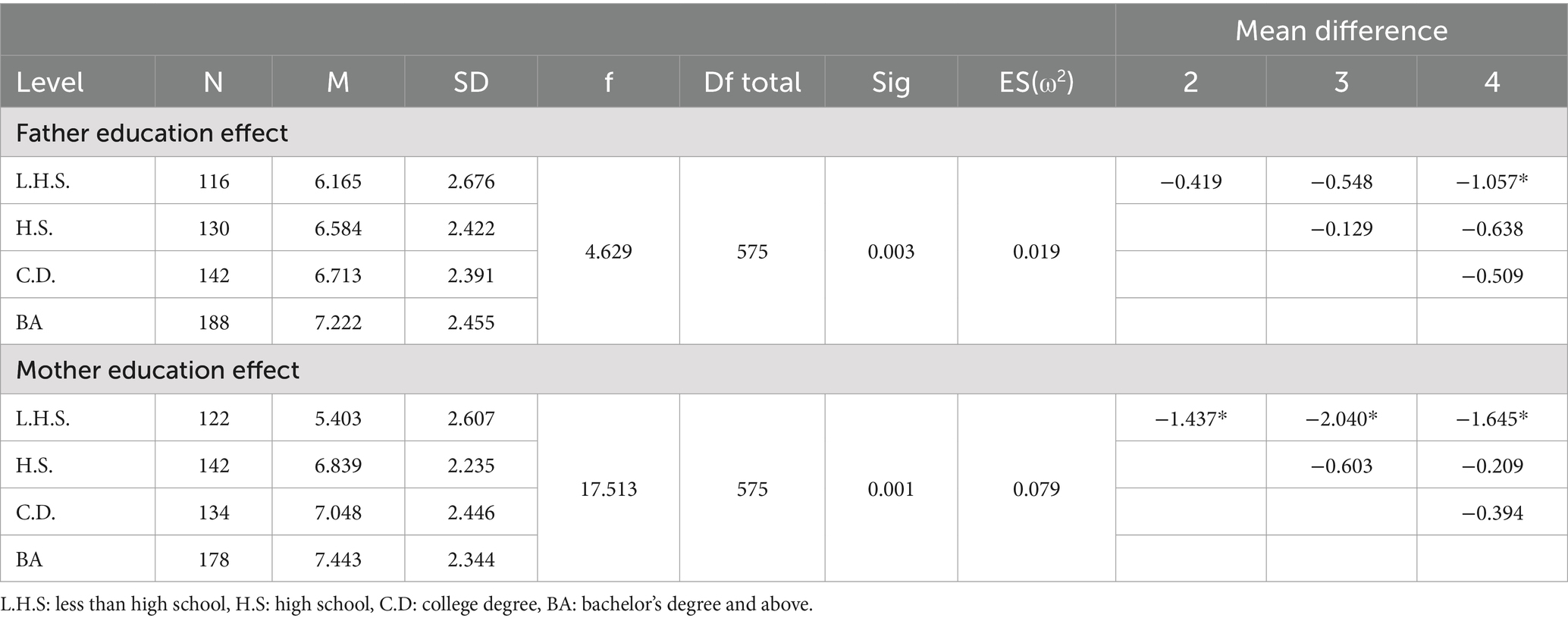

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to examine the differences in parental education levels, as seen in Table 3. To compare the students’ attitude ratings across their fathers’ education levels (less than a high school diploma, high school diploma, college degree, bachelor’s degree, and above), the sample sizes were 116, 130, 142, and 188, respectively. There was a statistically significant difference in the mean ratings across the groups (F = 4.62, p = 0.003). Post-hoc Tukey HSD tests showed that the bachelor’s degree group had a significantly higher mean rating (7.22) than the less-than-high school diploma group (6.16), with a mean difference of 1.05 (p = 0.005). The effect size, measured using Omega-squared (ω2), was small at 0.019. None of the other group differences were statistically significant. So, the father’s education level had a significant but small effect on the student’s attitudes, with those whose fathers had bachelor’s degrees and above exhibiting higher average ratings than those whose fathers did not complete high school based on this sample.

In addition, to compare the students’ attitude ratings across their mothers’ education levels (less than high school diploma, high school diploma, college degree, bachelor’s degree, and above), the sample sizes were 122, 142, 134, and 178, respectively. There was a statistically significant difference in the mean ratings across the groups (F = 17.51, p < 0.001). Post-hoc Tukey HSD tests showed that the less than high school diploma group had a significantly lower mean rating (5.40) than all the other groups, with mean differences of 1.43 (high school diploma), 1.64 (college degree), and 2.04 (bachelor’s degree and above), all p < 0.001. The effect size ω2 = 0.079 was medium. In brief, the mothers’ education level had a significant and medium effect on the students’ attitudes, with those whose mothers did not complete high school showing lower average ratings than all the other groups with higher education levels based on this sample.

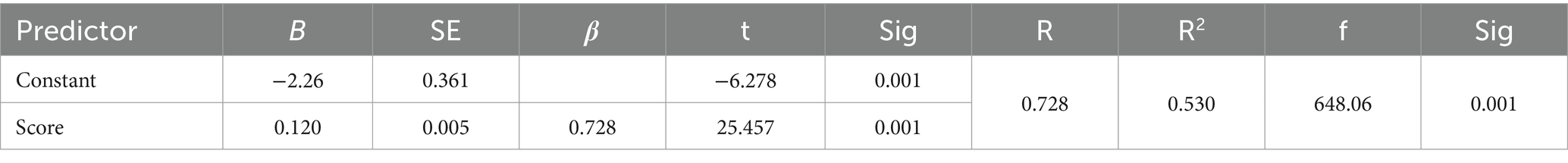

A linear regression analysis was conducted to assess the relationship between the students’ attitude ratings and their academic achievement scores (Students’ grades in English in the first semester), as Table 4 shows. The two variables had a strong positive correlation (r = 0.73, p < 0.001). The regression model showed a significant association between attitude ratings and achievement scores, F (1, 574) = 648.06, p < 0.001, with an R-squared of 0.530, indicating that the students’ attitudes explained 53% of the variance in achievement. The regression coefficient for the attitudes was 0.12 (p < 0.001), indicating that, on average, a one-point difference in the attitude rating corresponded with a 0.12-point difference in the achievement score. The effect size (R2) of 0.53 indicates a large practical significance. In summary, the students’ attitudes had a significant and sizeable predictive relationship with their academic achievement, as more positive attitudes were associated with higher achievement scores based on this sample.

Table 4. Simple linear regression analysis examining the relationship between attitudes and academic achievement.

Discussion and conclusion

Question one: “What are the attitudes of post-basic education students in the Sultanate of Oman towards the English language?”

The frequency analysis of the first question revealed some significant findings about the students’ attitudes towards English. The top selected item was “I feel proud when I speak English fluently,” with 49.7% of the students choosing it. This indicates that many students view English proficiency as an accomplishment worth taking pride in. This finding aligns with Soleimani and Hanafi's (2013) findings that students often have positive perspectives about acquiring English probably because they see value in becoming fluent. While this study was conducted in Iran, where English is primarily used in academic contexts, the Omani context differs as English serves academic and economic purposes due to Oman’s growing tourism and international business sectors. Al-Mahrooqi et al. (2016) also argued that Omani students recognize English mastery as a source of prestige, professional opportunities, and participation in the global community. Therefore, fluency represents a meaningful achievement for the students. In contrast, only 12.2% selected “Studying English is a waste of time” as their top choice. The low frequency of this highly negative attitude may suggest that most students disagree with the idea that studying English is not worth their while.

This finding is consistent with Ahmed A. (2015) and Ahmed Z. (2015) study, which showed that favorable attitudes persist among English majors despite language learning difficulties. The students recognize the benefits of English skills, even when learning the English language poses some challenges. As emphasized by Al-Issa (2020), Omani students view English as crucial for their academic success and career advancement. Overall, the frequency of results provides evidence that the Omani students in this sample predominantly hold positive attitudes toward the value of studying English. They view proficiency as a meaningful goal rather than considering English a waste of time. This agrees with previous research on students’ perspectives on learning the English language. These favorable attitudes likely stem from the students’ recognition of the importance of the English language for educational and professional opportunities in Oman’s multilingual context, as noted by Al-Mashikhi et al. (2021). Previous research has shown a strong connection between someone’s attitude toward learning English and how proficient they become in the language. Specifically, Hussain et al. (2011) found evidence for a substantial association between positive attitudes toward English and higher levels of English proficiency. This aligns with the view expressed by Dörnyei (2003) that language learners’ attitudes play a critical part in determining the outcome of the complex process of acquiring a new language. In other words, both studies suggest that having a favorable attitude toward English is linked to tremendous success in attaining English proficiency.

Question two: “Are there any statistically significant differences in the student’s attitudes towards the English language attributable to sex, academic track, parents’ education level, school type, and attending English language training courses?”

The mean attitude rating for the sample was 6.73 (SD = 2.50), which was significantly higher than the neutral rating of 6 (p < 0.001). However, the effect size was small at 0.30. Therefore, the students’ attitudes were overall mildly positive compared to a neutral stance. This finding aligns with Khan (2016) finding that students had moderately favorable perspectives on learning the English language.

As for the sex variable, there was no significant difference in the mean ratings of the male students (M = 6.59) and the female students (M = 6.90), p = 0.129. This contrasts with Soleimani and Hanafi (2013), who found male students to have more positive attitudes, while Al-Zoubi (2013) reported that female students showed significantly more positive attitudes than males. It is worth noting that these contrasting findings from Iran and Jordan may reflect different cultural contexts regarding gender roles in education. The parity found here could stem from schools providing equal English learning opportunities for both sexes. This finding aligns with Shams (2008) finding that equitable access narrows attitudinal gaps between sexes. Societal views on equitable education for all may also promote comparable attitudes. Mustafa (2017) study suggests that cultural shifts in sex roles and norms have led to more similar perspectives regarding schooling between male and female students.

In terms of school type, the private school students (M = 7.31) had significantly higher ratings than the government school students (M = 6.43), p < 0.001, with a small effect size of 0.35. This aligns with Kesgin and Arslan (2015), who reported that students in private schools often demonstrated more positive attitudes compared to public schools. While their study was conducted in Turkey’s educational system, the Omani context presents unique characteristics, such as private schools often offering enhanced English exposure through native speakers and international curricula. In contrast, government schools deliver most subjects in Arabic, with English as a separate subject. This suggests that the private school students showed more positive attitudes, which may be associated with differences in school environments. The private schools showed significantly higher ratings than the government schools. This highlights potential disparities in instructional quality, resources, and curriculum emphasis on English proficiency. Taha-Thomure (2008) study found that private schools tend to have smaller classes, better facilities, and more qualified teachers, which can positively impact students’ attitudes.

About the academic track, the science track students (M = 7.32) showed significantly higher ratings than the humanities track students (M = 6.13), p < 0.001, with a medium effect size of 0.51. agrees with Liu and Chen (2015), in their study of Taiwanese high school students, found that academic-track (Scientific) students had significantly higher extrinsic, overall motivation, and positive attitudes toward learning English. Although this study was conducted in Taiwan’s educational context, Oman’s distinct academic tracking system, where science track students typically require higher English proficiency for university studies conducted primarily in English, while humanities track students often pursue Arabic-medium programs, creates a different dynamic in students’ attitudes toward English learning. This indicates that curricula and teaching methods may differentially impact students’ attitudes. The science students had substantially higher ratings than the humanities students. Science curricula likely provide increased exposure to English terminology, scientific literature, and global concepts. Humanities may focus more on the Arabic language and local subjects. The curriculum emphasis can shape attitudes about the relevance of English to academic success and career prospects. According to Shaye and Abbas (2016) study, science and technical fields necessitate the learning of English more than humanities and social sciences, leading to more positive perspectives.

As for training courses, the students with training had higher ratings (M = 7.15) than the students who had no training (M = 6.79), p = 0.022, with a small effect size of 0.18. The study conducted by Bailly (2011) found that students with more English learning experience outside school tended to have more positive attitudes towards the language. This highlights the potential benefits of supplementary English training for improving students’ attitudes. Those with supplementary training showed more positive attitudes, demonstrating the benefits of such focused training beyond regular classes. Intensive practice and language exposure could boost students’ motivation for and confidence in using English. Al-Mekhlafi (2004) study noted that specialized English programs allow targeted instruction aligned with students’ needs and goals.

As per parental education levels, the students whose fathers had bachelor’s degrees and above showed higher ratings (M = 7.22) than those whose fathers had less than high school education (M = 6.16), p = 0.005, with a small effect size of 0.019. This suggests that Students’ attitudes were associated with parental education levels. Regarding the mother’s education, the students whose mothers did not complete high school had lower ratings (M = 5.40) than all the other groups, p < 0.001, with a medium effect size of 0.079. This reinforces the potential role of parental education in shaping students’ attitudes. Parental education levels, especially maternal education, emerged as a significant variable. In their study, Kesgin and Arslan (2015) reported that students whose parents had higher education levels (bachelor’s or postgraduate degrees) had more positive attitudes toward English. This implies that educated parents can positively influence students’ attitudes by emphasizing the importance of English to their children’s future, assisting them directly with studying English or providing additional language learning resources. Less educated parents may be less equipped to support English language education effectively. As Al-Saqqaf (2007) study showed, educated mothers tend to take an active role in their children’s language learning, which correlates with more positive perspectives on English adopted by their children.

Question three: “What is the relationship between the students’ academic achievement in English and their attitudes towards learning English?”

The linear regression analysis revealed that the students’ attitudes correlated with achievement. This explains a sizable 53% of the variance in English achievement scores, with a highly significant p-value <0.001. The large effect size of 0.53 indicates that the practical predictive relationship between the students’ attitudes and achievement is substantial. Specifically, the findings showed that more positive attitudes were associated with higher academic achievement in English. The students with favorable perspectives toward studying English tended to attain higher proficiency levels and exam scores. In contrast, those with more negative attitudes generally performed worse. This aligns with previous research by Gardner (1985), which also found that positive attitudes correlated with higher second language achievement. As he suggested, students who view the language as valuable and meaningful are more motivated to engage in learning and use it actively and fully. Their positive outlook is associated with their success in learning the language.

As Dörnyei (1998) discussed, students with affirmative attitudes are more determined to communicate in the language, seek out practice opportunities, and strive for fluency goals. While these motivational theories were developed in Western contexts, their application in Oman’s educational environment must consider the unique cultural factors where English serves as both an academic requirement and a gateway to international opportunities, particularly in Oman’s growing tourism and business sectors. This dual role of English in Omani society may strengthen the attitude-achievement relationship observed in this study.

In contrast, negative attitudes may hamper achievement by reducing students’ motivation, effort, class participation, and willingness to practice skills. Students who see less value in learning a second language or lack confidence in it are less likely to succeed in learning it. As found in a study by Sparks et al. (1989), those with unfavorable perspectives were more likely to avoid using the language, and that impacted their proficiency negatively. These negative attitudes reduce intrinsic motivation according to the self-determination theory. With a less sense of meaning, competence, and autonomy, students become demotivated and passive, and their achievement outcomes are generally negative.

Oxford (2015) emphasized that this bidirectional relationship between students’ attitudes and achievement suggests a virtuous cycle for learners with initial positive attitudes. Their positivity correlates with success, which is associated with more favorable attitudes and perpetuates their active engagement and continued achievement in learning the language. However, the opposite vicious cycle can trap students with initial negativity. Therefore, cultivating positive or favorable attitudes from the start has a crucial impact on halting the downward spiral of students’ diminished motivation for and disengagement in learning the language.

In conclusion, while the Omani students’ attitudes were mildly positive, several demographic factors, including school type, academic track, training courses, and parental education, showed significant differences. Notably, the study revealed that more positive attitudes were strongly correlated with higher academic achievement. This highlights the need for English language learners to foster favorable perspectives.

Recommendations

The study recommends implementing interventions to cultivate more positive attitudes toward English among Omani students. These could include emphasizing the benefits and relevance of English mastery, using inspiring role models, fostering feelings of accomplishment, and providing additional English language training opportunities, which were also associated with more positive attitudes in the study. The researchers also recommend evaluating differences in school curricula, teaching methods, and resources in private and public schools.

Limitations

This study on Omani students’ attitudes towards learning English has some limitations that affect the depth and generalizability of its findings. These include the geographically narrow sample drawn from only two governorates, the reliance on self-reported quantitative data, and the inability to make causal claims from cross-sectional data. In addition, expanding the theoretical framework and analytical models could strengthen the integrity and impact of this line of attitudinal research. Besides that, it is significant to acknowledge that the data in this study inherently has a nested structure, with students grouped within classes and schools. Due to limitations in the available data, we were unable to conduct multilevel analyses that would have allowed us to disentangle within-group and between-group effects.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Department of Educational Studies and International Cooperation, Ministry of Education, Sultanate of Oman. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

SA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft. SH: Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft. AH: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. ZH: Data curation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors gratefully acknowledge the research fundng provided by the Ministry of Higher Education, Research, and Innovation (MoHERI) of the Sultanate of Oman under the Block Funding Program. MoHERI Block Funding Agreement No. MoHERI/BFP/ASU/2022.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbas, F., and Iqbal, Z. (2018). Language attitude of the Pakistani youth towards English, Urdu and Punjabi: A comparative study. Pakistan Pak. j. distance online learn. 4, 199–214.

Ahmed, A. (2015). Attitudes towards English among English and non-English major Sudanese university students. Int. J. Engl. Lang. Linguist. Res. 3, 1–19.

Ahmed, Z. (2015). A study on attitudes of undergraduate students towards English language learning and their academic achievement in Malaysia. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. English Literat. 4, 124–133. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.4n.4p.124

ALHarthy, S., and Alsoudi, S. (2023). Constructing a scale for students’ attitudes toward English language according to Thurston method with equal-appearing intervals. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. Stud. 12, 563–581. doi: 10.31559/EPS2023.12.3.10

Ali, J. K., Shamsan, M. A., Guduru, R., and Yemmela, N. (2019). Attitudes of Saudi EFL learners towards speaking skills. Arab World English J. 10, 253–364.

Al-Issa, A. S. M. (2020). The language planning situation in the Sultanate of Oman. Curr. Issues Lang. Plann. 21, 347–414. doi: 10.1080/14664208.2020.1764729

Al-Issa, A. S., and Al-Bulushi, A. H. (2012). English language teaching reform in Sultanate of Oman: the case of theory and practice disparity. Educ. Res. Policy Prac. 11, 141–176. doi: 10.1007/s10671-011-9110-0

Al-Jardani, K. (2012). English language curriculum evaluation in Oman. Int. J. English Linguist. 2, 40–44. doi: 10.5539/ijel.v2n5p40

Alkhateeb, B. M. (2020). Saudi university students’ attitudes toward learning English as a foreign language and their motivational orientations. Engl. Lang. Teach. 13, 75–85. doi: 10.5539/elt.v13n11p75

Al-Maamari, F. S. (2013). Low academic achievement: Causes and results. Paper presented at the Educational Research Seminar, Muscat, Oman.

Al-Mahrooqi, R. (2012). English communication skills: how are they taught at schools and universities in Oman? Engl. Lang. Teach. 5, 124–130. doi: 10.5539/elt.v5n4p124

Al-Mahrooqi, R., Christopher, D., Steven, S., and Al-Maamari, F. (2016). English education in Oman: theory vs practice. Indon. J. Appl. Linguist. 5, 302–310.

Al-Mashikhi, K., Al-Jabri, M., and Nabil, A. (2021). English in the Sultanate of Oman. World English. 40, 298–311.

Al-Mekhlafi, M. (2004). The use of supplementary materials for teaching English as a foreign language in the Yemen Arab Republic. Tilka Manjhi, India: Bhagalpur University.

Al-Saqqaf, A. H. (2007). The perceived and actual roles of parents in the English language development of kindergarten students in the governmental schools in Aden governorate. Yemen: University of Pune.

Alsoudi, S., and AlHarthy, S. (2024). Applying the Guttman method and Rasch model to construct school Students' attitudes toward the significance of the mathematics scale. J. Southwest Jiaotong Univ. 59, 488–499. doi: 10.35741/issn.0258-2724.59.3.33

Al-Zoubi, S. M. (2013). The effect of Student’s engagement on their attitudes towards learning English as a foreign language. Int. J. Modern Educ. Comput. Sci. 6, 1–9. doi: 10.5815/ijmecs.2014.06.01

Anderson, F., James, J., Gross, B. P., and Kevin, O. (2022). Thinking about feelings: studying emotions with social cognitive and affective neuroscience. Am. Psychol. 77, 151–199. doi: 10.1037/amp0000878

Bailly, S. (2011). “Teenagers learning languages out of school: what, why and how do they learn? How can school help them?” in Beyond the language classroom. eds. P. Benson and H. Reinders (Berlin: Springer), 119–131.

Clement, R., and Murugavel, T. (2018). English for educational and career advancement in India: problems and solutions. Lang. India 18, 463–479.

Coronel, J. M. (2014). Toward a research-based assessment of Students' attitudes toward language learning. Appl. Res. Innov. 3, 237–254. doi: 10.17583/ari.2014.1187

Davis, P. E. (2018). The emotions of structure: How neuroscience informs teaching to the learning process. UK: Routledge.

Dörnyei, Z. (1998). Motivation in second and foreign language learning. Lang. Teach. 31, 117–135. doi: 10.1017/S026144480001315X

Dörnyei, Z. (2003). Attitudes, orientations, and motivations in language learning: advances in theory, research, and applications. Lang. Learn. 53, 3–32. doi: 10.1111/1467-9922.53222

Gardner, R. C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning: The role of attitudes and motivation. London: Edward Arnold.

Hassan, N. M. (2021). Language attitudes and English language proficiency of Yemeni university students. SAGE Open 11, 1–13. doi: 10.1177/21582440211003089

Hussain, I., Ayaz, M., and Shazia, A. (2011). Attitude of students towards English as a medium of instruction in Pakistan. Int. J. Acad. Res. 3, 38–42.

Jabbar, A., Khudhair, A., and Abid, H. (2017). Social background predictors of English language correlates: an interrogation from Saudi EFL learning setting. Cogent. Education 4:726. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2017.1350726

Jones, J. P. (2021). Influence of student attitude on online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Bus. Admin. Online 10.

Kesgin, N., and Arslan, M. (2015). Attitudes of students towards the English language in high schools. Anthropologist 20, 297–305.

Khan, I. A. (2016). Attitudes of Saudi students towards English language learning in KSA. Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Res. 16, 6–14.

Kirkpatrick, A., and Al-Batal, M. (2022). The handbook of Arabic second language acquisition. USA: John Wiley & Sons.

Lee, J. S. (2022). Using L2 motivational self system and perceived value to understand heritage learners’ motivational behaviour. System 103:102615. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2021.102615

Lee, J., and Katherine, J. (2019). The impact of student affect and academic achievement on teacher-student relationships. J. Adv. Acad. 31, 14–35. doi: 10.1177/1932202X19873672

Liu, H.-j., and Chen, C.-w. (2015). A comparative study of foreign language anxiety and motivation of academic-and vocational-track high school students. Engl. Lang. Teach. 8, 193–204. doi: 10.5539/elt.v8n3p193

Maqbool, S., Umar, L., and Kamran, U. (2018). International Arab Students' attitude towards learning English. Glob. Region. Rev. 3, 389–401.

Mustafa, R. F. (2017). The impact of learning english as a foreign language on the identity and agency of Saudi women. Doctoral thesis, University of Exeter, United Kingdom. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, 10766831.

Oxford, R. L. (2015). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Shams, M. M. (2008). Students' attitudes, motivation and anxiety towards English language learning. J. Res. Reflect. Educ. 2, 104–112.

Shaye, S., and Abbas, E. Z. (2016). Relationship between field of study and attitudes towards learning English as a foreign language. Int. J. Hum. Cult. Stud. 3, 1885–1892.

Smith, M. P. (2020). The role of affective and cognitive attitudes in mathematics achievement in England. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 18, 2343–2364. doi: 10.1007/s10763-020-10095-4

Soleimani, H., and Hanafi, R. (2013). Iranian medical Students' attitudes towards English language learning. Int. Res. J. Appl. Basic Sci. 4, 3816–3823.

Sparks, R. L., Patricia, A. G., and Leonore, J. P. (1989). Linguistic coding deficits in foreign language learners. Ann. Dyslexia 39, 179–195.

Taha-Thomure, H. (2008). The status of English language teaching and learning in Libya. South Africa: University of South Africa.

Visser, M. (2008). Learning under conditions of hierarchy and discipline: the case of the German Army (1939–1940). Learn. Inq. 2, 127–137. doi: 10.1007/s11519-008-0031-7

Keywords: attitudes, English language learning, non-native students, foreign language, Sultanate of Oman

Citation: Alsoudi S, Al Harthy S, Al Harthy A and Al Harthy Z (2024) Attitudes of non-native students towards learning English as a foreign language: a case study in secondary schools in the Sultanate of Oman. Front. Educ. 9:1344863. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1344863

Edited by:

Matthias Ziegler, Humboldt University of Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Matthew Easter, University of Missouri, United StatesMo’en Salman S. Alnasraween, Yarmouk University, Jordan

Mohammad Alqudah, Tafila Technical University, Jordan

Copyright © 2024 Alsoudi, Al Harthy, Al Harthy and Al Harthy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sharif Alsoudi, c2hhcmlmLmFsc291ZGlAYXN1LmVkdS5vbQ==

Sharif Alsoudi

Sharif Alsoudi Salim Al Harthy

Salim Al Harthy Azza Al Harthy

Azza Al Harthy