94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 18 September 2024

Sec. Language, Culture and Diversity

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1343969

Assessments of written production in English as a foreign language play an important role in the overall grading of learners’ English at school. Evidently, the other three skills than writing are also considered, but written texts are useful to work with as they provide concrete material easily available to study when it comes to learners’ levels of achieved language proficiency. The teachers’ overall and immediate impression of the text could play a significant role in the final grading of the production. It is therefore worth investigating the variation of linguistic features in texts of similar length produced by learners of the same age. In the present study, young learners’ written production in English is analyzed with several approaches. The learners’ texts were of similar length and language quality but had different characteristics in terms of structure and style. The results show an overall picture of factors influencing teachers’ assessment of young learners’ texts in EFL and are therefore useful information to consider for English teachers to ensure valid and reliable assessments of learners’ written productions of English as a foreign language.

Assessing written production in English as a foreign language (EFL) is a worldwide phenomenon carried out by many teachers at schools. We may expect that for young learners, whose texts are often shorter than for more qualified and mature learners, teachers grade their productions with the help of a global assessment based on the overall impression of the text. Using factorial assessments may be useful in some contexts, but as the prerequisites for variation regarding factors, such as grammatical complexity and lexical range are more limited in short texts, the teachers’ first and immediate overall impressions of the quality of the texts could play a significant role. For that reason, variables, such as a personal tone or an informal style may be crucial for teachers’ ratings of the productions. English is taught at primary schools in most countries, and analyzing texts in order to provide information for sustainable assessment is essential in order to secure reliable means of comparisons of learners’ production. In addition, there are demands for studies of assessments in order to secure valid and accurate grading of the learners’ skill of writing in EFL. Therefore, it is worth investigating young learners’ written production in EFL in a careful and detailed way. From an international perspective, the findings are of particular interest when data comprise production by learners from several different educational and cultural contexts. This is relevant as the English language has become the lingua franca in the world with frequent encounters and communication between non-native speakers of England. It is even claimed that the most common use of the English language is in English as a lingua franca (ELF) communication among non-native speakers of English. This makes this study of written EFL relevant. (See, e.g., Jenkins, 2007, Seidlhofer, 2011).

In the present study, learners of the same age from Estonia, Latvia, and Sweden participated in the production of the texts. The data are thus of interest to primary school teachers in their assessment procedures. Furthermore, results from these findings are of interest for providing sustainable assessment tools in primary teacher education.

The teaching of EFL in primary schools is widely spread in countries across the world. In the early years, the focus was on speaking and listening to gradually include also reading and writing. With the current changes in communication due to modern digital technology, there are new demands on written communication that in some contexts is close in style and structure to the spoken language. This may be experienced in contexts outside school, the so-called extramural English (Sundqvist and Sylven, 2016), and can be found in interaction in chats, social media, and computer games. These interactions occur in international settings when EFL serves as a lingua franca between young people in different regions of the world. In these contexts, the focus is on successful communication and the message in these spoken or written productions is thus simply to be communicated and understood, and less focus is thus on accuracy. This means that immediate communication with less focus on accuracy in EFL is common among young people in today’s society. Therefore, the assessment and quality of young learners’ written production as discussed in the present article is worth reconsidering when teachers evaluate and assess young learners’ written production at schools.

Evidently, these new ways of using EFL in digital contexts influence young learners’ perceptions of their writing in EFL. When children regularly use the English language in both writing and speaking in informal settings and in communication that really engages them in their free time in many different contexts, we may expect that these habits and ways of communicating strongly influence their ways of working with their written texts in their classrooms.

The present study adopts the view of development and variation in language learning of the dynamic systems theory (DST) as described by van Dijk et al. (2011). This dynamic usage-based (DUB) perspective assumes that there is no innate faculty in the language learner for the development of different aspects of proficiency, such as grammar, but that the individual learner discovers the foreign language through frequent exposure and personal experiences of the language studied (Verspoor et al., 2012). It is generally recognized that one of the most significant and recognized factors in working for language development is a large amount of input in L2 (see e.g., Larsen-Freeman, 1976, Krashen, 1985). With the current use of digital tools in international communication and exposure to English among young people, we may expect that the variation in proficiency and uses of EFL may increase.

The term dynamic implies variation and that many different factors are influential in the individual learner’s progress toward language proficiency. The individual learners with their specific background variables in terms of L1, age, motivation, and type of exposure follow different paths on their way to reach their desired level of language proficiency. The different sub-systems in a language, such as morphology, vocabulary, and structure, develop over time and interact in various ways in the learning process of the foreign language. The variation will be both unpredictable and more systematic and depends on whether the acquired language system is at an early stage and thus in a phase of reorganizing or at a later and more advanced phase and then to be described as a more stable system. In addition, the interaction of different complexity traits changes over time. The language learned is in this way in constant flux (Spoelman and Verspoor, 2010).

Written production is useful to analyze when there is an interest in investigating learners’ proficiency in a foreign language as writing samples provide access to the learner’s language use with several dimensions, such as vocabulary, idiomatic expressions, and syntax. Compared to speaking, writing tasks provide learners with the time and opportunity to show what they can do with the language as writing provides time for planning, reflection, and revision. For this reason, writing is generally more linguistically complex than speaking (Johansson and Geisler, 2011, Ortega, 2012, Bukta et al., 2013, Bi and Jiang, 2020).

At the same time, learners’ free written production is characterized by variation as we may expect the individual learner does not behave in the same way on different communicative occasions or in varying contexts. One grammatical structure may be used in one way in one sentence and then used in another way in the following sentence. The reasons behind this may be a lack of mastery or a shift in focus from communication to accuracy in language production (van Dijk et al., 2011). There is thus an expected variation in learner language as the same learner does not behave linguistically in the same way all the time. Leki, Cumming, and Silva describe this phenomenon when they summarize findings from several studies that show “the wide variation between individual young writers and individual pieces of writing by the same child” (2008: 13).

Assessing free production is usually problematic, and working with labels, such as beginner, intermediate, advanced, and native-like gives grounds for highly subjective assessments (Larsen-Freeman, 2006). There is therefore a demand for more reliable means when assessing learner production. A starting point in discussions of investigating proficiency may be factors such as complexity, accuracy, and fluency. These three factors are generally indicators of improved language proficiency. However, when it comes to the first factor, namely complexity, there is in addition a need for other approaches than general measures such as sentence length. These complexity measures are, for instance, sub-clausal complexity and complexity via subordination and coordination (Norris and Ortega, 2009). Other ones to mention are the proportion of nominalizations, the occurrence of pre- and post-modifications of noun phrases, and the complexity of verb phrases (simple or compound structures).

Vocabulary is a useful measure to identify the proficiency level, which has been shown in several studies. The results from several studies indicate, which can be expected, that lexis generally changes as proficiency increases in terms of sophistication, originality, and diversification (Leki et al., 2008 p. 171).

The length of written production is a variable that is an indicator of the learners’ achieved proficiency. The longer the text, the higher the expected rating. However, how long does a text need to be in order to provide substantial data for reliable and sustainable assessment? In a Dutch study, the researchers collected samples of English written production by 12- to 13-year-olds and 14- to 15-year-olds. In this study, texts up to 200 words were assumed long enough for the linguistic analyses (Verspoor et al., 2012).

The present study investigates the qualities of texts in EFL written by young learners. There are both linguistic and didactic dimensions of the present study. The linguistic dimension includes descriptions of lexical, syntactical, and stylistic traits, as well as content and structure in the Estonian, Latvian, and Swedish 12-year-olds’ written productions. The didactic dimension focuses on the possible implications for English teachers in the young learners’ classroom when it comes to assessments of written production, based on the findings in the present study.

The research questions are as follows:

What variation is identified in young learners’ texts of similar lengths and with the same topic?

In what way can the variation or the lack of variation in produced texts be helpful for school teachers in their assessment of written production in EFL?

For the present study, texts from the BYLEC corpus were selected. This corpus consists of production by 12-year-old young learners in six different countries in the Baltic Region. The BYLEC data comprise six writing tasks that involve simple, descriptive, and personalized topics (For further details about the BYLEC corpus, see Sundh, 2016). The selection of the texts used in the present study are from the last task (Task 6) in the BYLEC corpus. Task 6 consists of a description of the possible future lives of the young learner in approximately 20 years. (See Appendix 1 for the instructions of Task 6.)

A total of 18 texts from the BYLEC corpus were selected, and these texts were written by Estonian, Latvian, and Swedish students. All these 18 texts were of similar length: 200 words (+/− 10%) as the length of a text tends to be a factor that tells us about the quality of the language produced; 200 words (+/− 10%) was the length of the 18 texts which was a criterion for the selection since then the texts would be long enough for the linguistic analyses. This assumption is based on the results of a study on Dutch young learners’ production in EFL described above (Verspoor et al., 2012).

At the same time, it was desirable to identify possible variations in the quality of the texts. Examples of qualitative factors, that could be relevant to investigate, are the degree of syntactic complexity, the choice and range of vocabulary, a personal tone, and a more formal or informal tone.

For the investigations of the lexical diversity and the variation of vocabulary in the texts, three tools were used: Vocabprofile, Wordsmith, and SWEGRAM. These three tools are described in the following paragraphs.

Wordsmith Tools is Windows software for finding word patterns. The tools are well established for investigations of concord, keywords, and word lists. In this study, three tools are used in the investigations of the 18 texts for the purpose of the study: type count, average sentence length, and the TTR (type–token ratio).

Compleat Lexical Tutor with the Vocabprofile—VP Classic is used for the survey of the word usage by the 18 learners. The tool is used to identify the proportion of K1, K2, and OL words in the texts. The analysis shows how many words the text contains from the following three frequency levels: (K1) the list of the most frequent 1,000-word families, (K2) the second most frequent 1,000-word families, and (OL) words that do not appear on Academic word list or the other lists.

The tool SWEGRAM from Uppsala University is used to identify traits in the language used in the texts. In this analysis, the results in 10 categories are presented: Word length, Sentence length, Readability Coleman, Readability Flesch Ease, Readability Flesch Kincaid, Readability Auto-index, Readability SMOG, Proportion nouns, Proportion adjectives, and Proportion verbs.

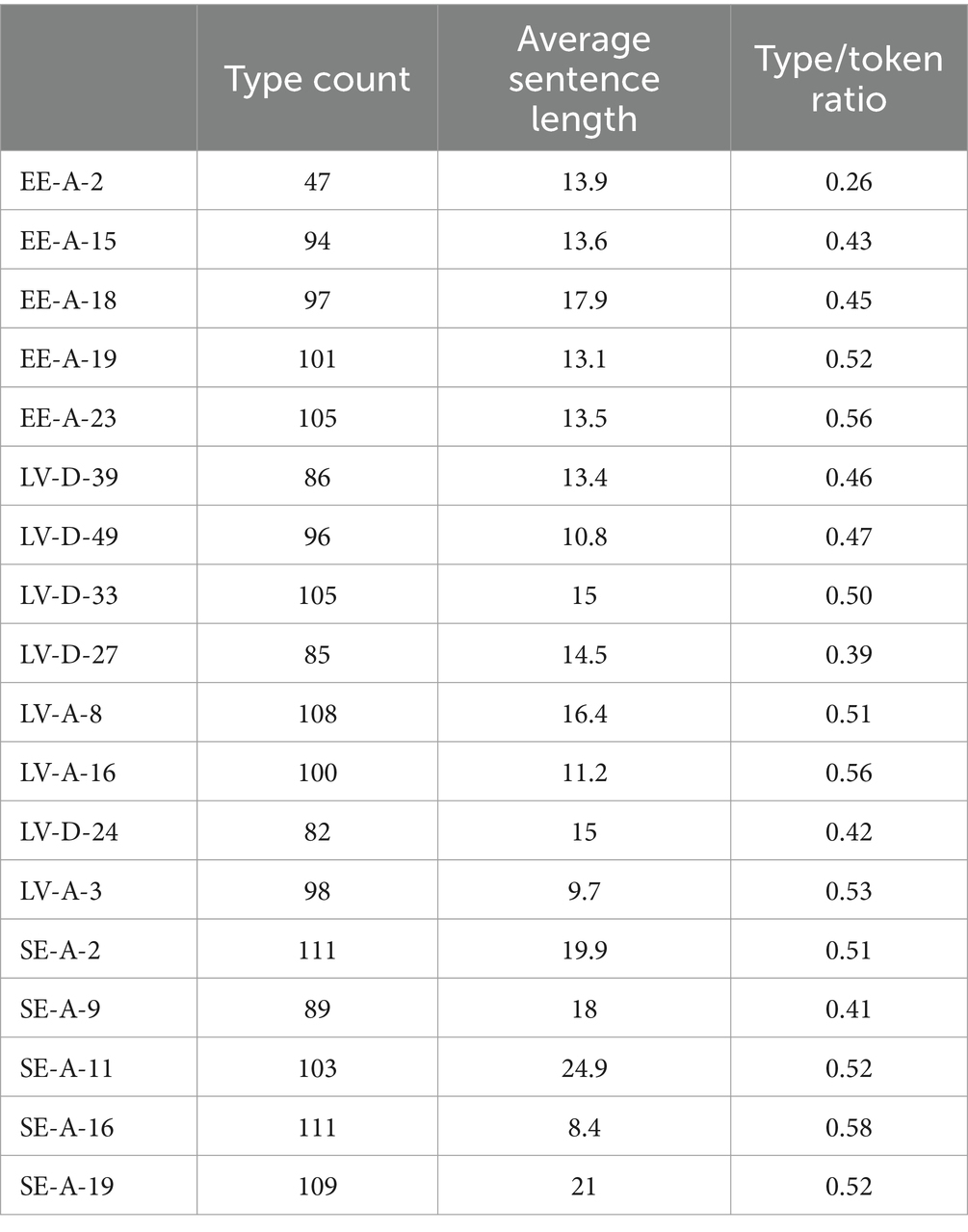

The results in Table 1 show that the number of types in the texts is between 47 and 111 types. One text has 47 types, and the remaining 17 texts have between 82 and 111 types. As for sentence length, the results show an average variation between 8.4 and 21. When looking at the types/token ratio we see the same tendency as for the type count results; learner EE-A-2 has a significantly lower score of 0.26 than the other 17 learners.

Table 1. Result for the 18 young learners’ texts with type count, average sentence length, and type/token ratio.

Learner EE-A-2 has a clearly more limited range of vocabulary in the texts, whereas the others’ texts show no remarkable differences in the range of vocabulary. Regarding sentence length, however, the variation is worth commenting on. Even if the range of vocabulary (type count) and the TTR are somewhat similar, the average sentence length differs significantly (cf. learners SE-A-19, SE-A-16, and SE-A-11).

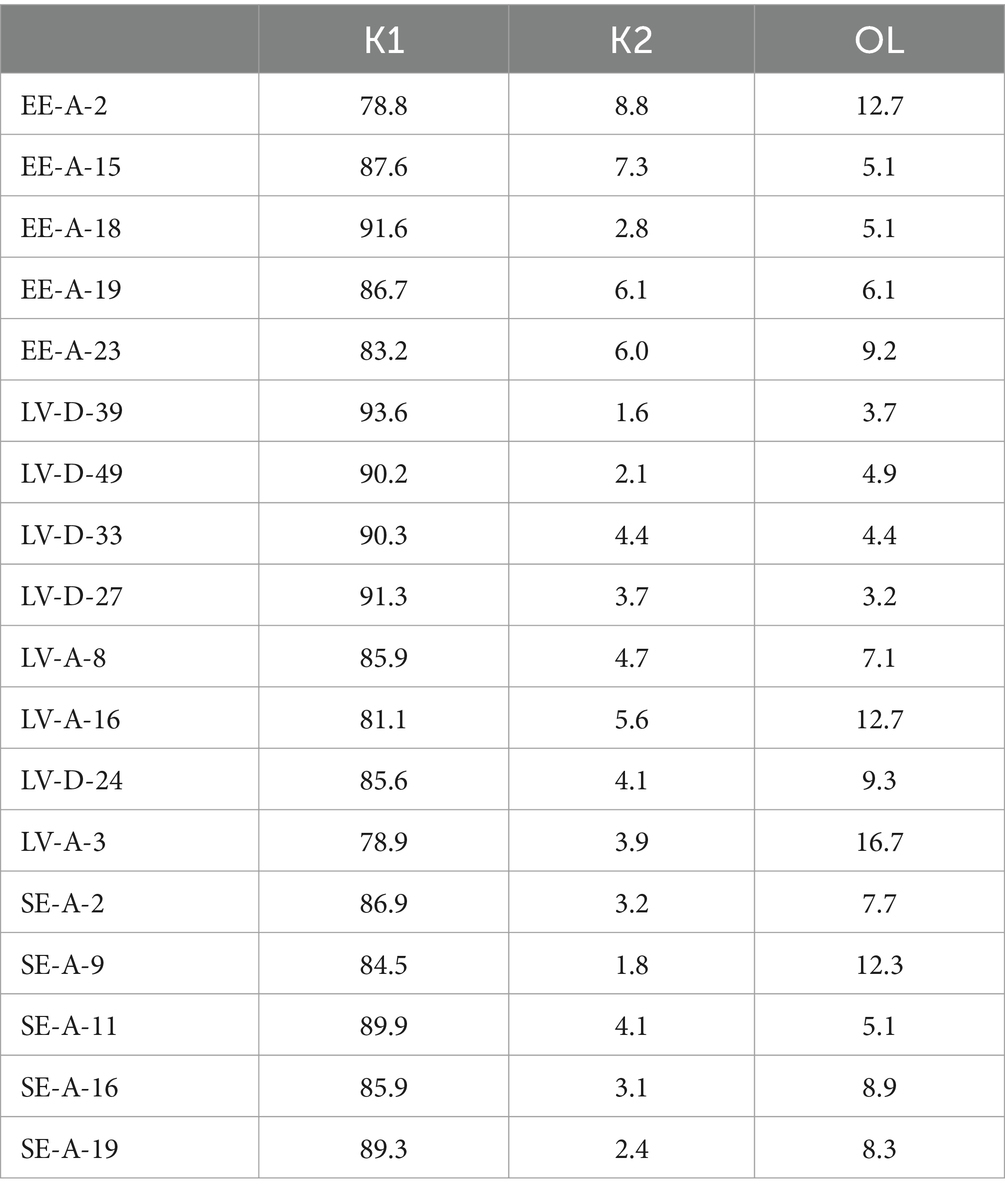

Table 2 below shows the distribution of high-frequency words in the two bands K1 and K2 and then words that can be classified as non-standard in English and thus categorized as Off-list (OL) words. The results indicate that between 78.8 and 93.6% of the words used by the learners belong to very frequent words in the English Language. The learners thus use a very central vocabulary in their texts. When it comes to the band K2, the variation is between 1.6 and 8.8%. We can thus observe that the learners do not vary their use of vocabulary to a great extent but tend to adhere to the most common words in English.

Table 2. Occurrence of high-frequency words (token in %) in the bands K1 and K2 and in words occurring in the Off-list (OL) in the Vocabprofile analysis (classic version) (lextutor.ca).

Regarding the use of non-standard vocabulary, i.e., using words that do not exist in the English language due to erroneous spelling or word coinage from their L1, we can see that there is a range between 3.2 and 16.7%. There is no clear tendency for the K1 and K2 scores for the four learners with their high OL scores.

The results from the analysis in Appendix 2 show that there is little variation in the learners’ uses of the 10 variables investigated. In Appendix 2, the following categories are included: Word length, Sentence length, Readability Coleman, Readability Flesch Ease, Readability Flesch Kincaid, Readability Auto-index, Readability SMOG, Proportion nouns, Proportion adjectives, and Proportion verbs.

Some variation is relevant to highlight. The average sentence length in the texts written by the Swedish learners is generally longer than for the Estonian and Latvian learners. The same tendency can be seen for the average word length. This is in line with the results observed in Table 1. Regarding the measures for readability, we can see that in particular, one Swedish learner’s language use differs from the others: SE-A-16 but also that the same tendency is identified in the three other Swedish learners’ texts. When it comes to the proportion of word classes, we see some interesting results. Three Latvian learners have a high proportion of nouns in their texts (LV-A-8, LV-A-16, and LV-D-24) and are characterized by nominalizations. Three Estonian learners (EE-A-2, EE-A-15, and EE-A-18) have more adjectives in their texts than other learners. Possibly, these three learners have adopted a more descriptive and narrative style in their texts. Finally, two learners, namely, EE-A-2 and LV-D-24, use few verbs in their texts.

In addition to the investigations of the lexical diversity and syntactic variation in the 18 texts with the help of the three tools described above, a qualitative analysis was carried out. The texts were analyzed in terms of identifying linguistic and stylistic variables using a qualitative approach. These descriptions thus aim at providing additional information about the observed features in the texts that could be relevant when schoolteachers are to assess texts in ELF. In Table 3, these short qualitative descriptions are provided for five texts written by Estonian learners (EE), eight texts written by Latvian learners (LV), and five texts written by Swedish learners (SE). It should be emphasized that these descriptions are subjective and partly impressionistic and based on the observations and careful readings by the researcher himself.

Table 3. Qualitative descriptions of the Estonian (EE), Latvian (LV), and Swedish (SE) learners’ texts.

The observed traits and characteristics in the 18 texts are found in Table 3. It is worth emphasizing again that the 18 texts are of similar length and that the writers are all 12–13 years old.

The results show that generally the observed variables across the texts can be summarized in the following way:

• Repetitive structures

• A colloquial style

• Meta talk

• An informal tone

• A personal address/tone/engagement

• Characteristics of spoken language

• A structured text into parts or paragraphs

• Syntactical complexity

Some more “traditional” factors in the assessments of learner language were also observed, and they are then often related to accuracy, such as spelling and grammatical errors. However, it can be claimed that some of the features identified, such as a colloquial and informal style, a personal tone, and engagement, can be related to the use of speaking EFL in extramural contexts and informal contexts and probably in communication with only non-native speakers, namely, as English as a lingua franca (ELF), whereas some of the features identified are more related to formal factors, such as structure and complexity, and can possibly be more related to the written language taught at school.

The linguistic analyses of the texts using Wordsmith show that for most of the texts of similar length, there are similar scores for type/token and type count. Sentence lengths show some differences. It is thus clear that even though the texts are of similar length, some variation can be found in some specific texts but overall there are no great differences across the texts.

There are numerous features that can be explained by instant oral communication experienced by these young learners, probably in interaction with other non-native speakers of English. The use of the English language is so widespread and the dominant language in use in, for instance, video games and digital meetings, that influences their written production in English. The frequent use of English as a lingua franca (ELF) in these contexts thus gives traces in written productions in school contexts.

There is an overall tendency in the material produced by Estonian, Latvian, and Swedish young learners in spite of all the similarities in their uses of the English language. This observed tendency is that the texts by Swedish young learners have a more informal style, often close to the spoken mode than the texts by Estonian young learners. These texts by Estonian learners have fewer instances of grammatical inaccuracy and word coinage. One interpretation is that these differences could be the results of the priorities in the curricula in each country and therefore the ways the teaching and learning of English are organized.

Evidently, there are many factors that may influence how school teachers assess English texts in their work at school. Single occurrences or a combination of certain variables and features could, in turn, lead to complexity for the assessor in the global rating of the production.

The results presented above show that there are demands on the assessor to be aware of the minor nuances and traits that can lead to certain global assessments. This leads to the recommendation of in-service training for English school teachers at the upper primary level when assessing young learners’ texts at schools. This is especially relevant at present with the constant occurrence of English in media and the enormous input of the English language in young learners’ lives.

ELF is also a factor to consider in the evaluation of young learners’ written production. Young learners are exposed to the English language every day and use it in informal and relaxed contexts in their spare time. Evidently, this influences the quality of their output. There is a need in the future for English teachers, even at elementary levels of teaching English, to be well aware of strategies in use in ELF communication. These strategies include ways of dealing with a lack of vocabulary or paraphrasing when discussing more complicated matters. In addition, teachers are to be informed about the impact of conversational skills gained in computer games so that teachers can understand the reasons for the occurrence of a certain style when assessing written productions. This area is definitely a field of research worth considering for linguistic and learner studies in the future. The results from these future studies can be expected to be extremely useful in teacher education and in-service training of English teachers.

We need to acknowledge the significance of strengthening the validity and reliability in the assessments of free written production in English as a foreign language with the new perspectives gained in English language learning. Today, there is an awareness among researchers and many language teachers of the dynamic and individual ways of both learning and using a foreign language. There is no longer a clear-cut border between the written and spoken modes in language production with the digital tools and contexts in use. Therefore, it is worth including factors that are traditionally seen as features of spoken English in the assessments of written productions by young learners of EFL.

Reliability in the assessments of free oral or written production in English is a challenge that has been shown in previous studies (see, e.g., Sundh, 2003). Teachers need to discuss productions of different qualities in order to ensure that they rate the productions in reliable ways. In addition, what is interesting is that young learners aged 12 years in the Baltic Region tend to use similar vocabulary; for instance, adjectives in their written productions (see, e.g., Sundh, 2017), which is another factor that is useful to know for teachers during their assessment of production in English. The fact is that no matter the learners’ L1, they tend to stick to the same core of vocabulary in their productions.

A challenge in the reliable assessment of free production, both written and oral, is to assign a global grade when there is great variation in the quality of factors in one text. The variation could be in a way, such as grammatical accuracy, but a limited range of vocabulary, sophisticated vocabulary but simple syntax, or fluency in delivery but limitations in organizing the structure of a text. It is thus less challenging to assess production globally when the different factors, such as vocabulary, grammatical accuracy, fluency, or structure, are of similar quality. The significance of being aware of one’s own attitude and view in the assessment procedures on the occurrence of these features, such as discourse markers, personal tone, or humor, is of great significance.

The results in the present study are relevant and useful for further research on school teachers’ assessments of young learners’ free written production in EFL. The similarities but also the variation in language and style in the different texts are of interest when the texts are assessed with a global rating. This proposed follow-up study could be carried out in an international context with school teachers from different educational and cultural backgrounds. School teachers are thus recommended to consider all these aspects in their assessments of the free written production of EFL by young learners.

The results of the present study clearly show the need for further research in the field of assessing young learners’ production of EFL. As there are so many factors to consider for school teachers in the assessments of the language produced, it is highly useful to investigate this area as a follow-up to this study. Another interesting aspect to take into account is to see whether school teachers’ different nationalities and backgrounds play a role in the tendencies of their assessments.

To summarize, the results of the present study show the quality of young Estonian, Latvian, and Swedish learners’ written production and the limited differences between nationalities that we can identify despite differences in school systems, teaching methods, and cultural contexts. The results also show the global and international roles that the English language has today as the lingua franca in the world and the fact that the English language is used to a great extent in extramural settings, in some cases thus more outside school than in school. These findings definitely have didactic implications for the English teachers’ work with the planning, teaching, and assessments all over the world.

The next step in further research is to use these 18 texts in real assessments by school teachers to see what texts are rated with a high or low grade. The assessments would be of interest to the teachers to see how they rate productions of similar length but with different linguistic, structural, and stylistic characteristics. This could be done by, for instance, using the tool, namely, Comparative Judgment,1 but, of course, also in other ways.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human data in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in the study was not required from the participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

SS: Writing – original draft.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1343969/full#supplementary-material

Bi, P., and Jiang, J. (2020). Syntactic complexity in assessing young adolescent EFL learners’ writings: syntactic elaboration and diversity. System 91:102248. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2020.102248

Bukta, K., Borowska, A., and Becker, C. (2013). Rating EFL written performance. London, England: Versita Limited.

Jenkins, J. (2007). English as a lingua franca: Attitude and identity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Johansson, C., and Geisler, C. (2011). “Syntactic aspects of the writing of Swedish L2 learners of English” in Corpus-based studies in language use, language learning, and language documentation. eds. J. Newman, H. Baayen, and S. Rice. Brill. 139–155.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (1976). An explanation for the morpheme acquisition order of second language learners. Langu. Learn. 26, 125–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1976.tb00264.x

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2006). The emergence of complexity, fluency, and accuracy in the oral and written production of five Chinese learners of English. Appl. Linguis. 27, 590–619. doi: 10.1093/applin/aml029

Leki, I., Cumming, A. H., and Silva, T. (2008). A synthesis of research on second language writing in English. New York, NY: Routledge.

Norris, J. M., and Ortega, L. (2009). Towards an organic approach to investigating CAF in instructed SLA: the case of complexity. Appl. Linguis. 30, 555–578. doi: 10.1093/applin/amp044

Ortega, L. (2012). “Interlanguage complexity” in Linguistic complexity: Second language acquisition, indigenization, contact. eds. B. Kortmann and B. Szmrecsanyi (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter), 127–155.

Spoelman, M., and Verspoor, M. (2010). Dynamic patterns in development of accuracy and complexity: a longitudinal case study in the Acquisition of Finnish. Appl. Linguis. 31, 532–553. doi: 10.1093/applin/amq001

Sundh, S. (2003). Swedish school leavers' oral proficiency in English: Grading of production and analysis of performance. Diss. Uppsala Univ: Uppsala.

Sundh, S. (2016). A Corpus of young learners’ English in the Baltic region–texts for studies on sustainable development. Dis. Commun. Sustain. Educ. 7, 92–104. doi: 10.1515/dcse-2016-0018

Sundh, S. (2017). "My friend is funny" - Baltic young Learners' use of a number of adjectives in written production of English the new English teacher. New English Teacher. 7, 92–104.

Sundqvist, P., and Sylven, L. K. (2016). Extramural English in teaching and learning: From theory and research to practice. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

van Dijk, M., Verspoor, M., and Lowie, W. (2011). “Variability in DST” in A dynamic approach to second language development: Methods and techniques. eds. M. Verspoor, K. De Bot, and W. Lowie (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. Company), 55–84.

Keywords: young learners, written production in EFL, sustainable assessment, Baltic Sea region, linguistic analyses

Citation: Sundh S (2024) Analyses of non-native Estonian, Latvian, and Swedish young learners’ written production in EFL: similarities and differences. Front. Educ. 9:1343969. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1343969

Received: 24 November 2023; Accepted: 16 July 2024;

Published: 18 September 2024.

Edited by:

Vita Kalnberzina, University of Latvia, LatviaReviewed by:

Vera M. Savic, University of Kragujevac, SerbiaCopyright © 2024 Sundh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Stellan Sundh, c3RlbGxhbi5zdW5kaEBlZHUudXUuc2U=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.