Corrigendum: Understanding L2 generalist teachers' motivation for teaching EFL in China's rural elementary schools

- School of Foreign Languages, China University of Petroleum, Beijing, China

In the context of global mandates for English as a Foreign Language (EFL) education, rural regions face significant hurdles in delivering high-quality language instruction. Generalist teachers in these areas often lack specialized training in EFL, yet are tasked with its instruction. Referred to as L2 generalists, these educators hold a pivotal role in EFL education. However, a notable gap exists in understanding the motivation propelling generalist teachers to undertake EFL instruction, particularly within Chinese rural primary schools, where various challenges persist. Grounded in self-discrepancy theory and possible selves theory, this study examined the way L2 generalist teachers' teaching motivation linked to their various self-concepts as well as their responses to various challenges when delivering EFL teaching in rural elementary schools in China. The study uncovered that the alignment between L2 generalist teachers' ought selves (i.e., the selves that they believe they should be) and ideal selves (i.e., the selves they aspire to become) acted as motivating factors, guiding their active involvement in EFL teaching. However, challenges such as a lack of professionalization and high contextual expectations led to a discrepancy between their actual selves (i.e., the selves they perceive themselves to currently be) and their ought/ideal selves, diminishing their teaching motivation. Furthermore, the presence of ambiguous and conflicting school policies further complicated matters, confusing generalist teachers and eroding their motivation for teaching. Despite experiencing a decline in motivation for EFL teaching, their commitment to their students fostered consistency between their ideal and ought selves, inspiring them to innovate pedagogical strategies within their capabilities. The study's findings hold significance for policymakers and teacher educators, highlighting the necessity of implementing strategies to enhance the professional growth of rural L2 generalist teachers.

1 Introduction

The worldwide introduction of mandatory English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learning in public education has led to promising reforms but also challenges for rural education (Izquierdo et al., 2021). Teachers in impoverished rural areas face numerous obstacles, such as limited resources, poor working conditions, and low student engagement (Gao and Xu, 2014; Liu et al., 2021). These stressors often result in negative perceptions toward their profession (Corbett et al., 2021), leading to a growing attrition rate among specialized teachers, especially those teaching foreign languages (Acheson et al., 2016; Li et al., 2020).

In rural areas, generalist teachers (i.e., educators who have a broad range of knowledge and skills across various subject areas) are often compelled to teach English despite lacking expertise or training in the subject (Coelho and Henze, 2014). These teachers, referred to as L2 generalists, face challenges due to their limited language competence and pedagogical knowledge (Izquierdo et al., 2021). Consequently, they struggle to deliver effective language instruction, leading to motivational inadequacy and ineffective teaching engagement (Wang and Chen, 2022). Despite the importance of their role, research on L2 generalist teachers is limited (Hossain, 2016; Izquierdo et al., 2021). Investigating their motivation is crucial as it impacts student motivation, teacher retention, and long-term professional commitment (Dörnyei and Kubanyiova, 2014; Gao and Xu, 2014).

Teacher motivation “determines what attracts individuals to teaching, how long they remain in their initial teacher education courses and subsequently the teaching profession, and the extent to which they engage with their courses and the profession” (Sinclair, 2008, p. 80). It is closely tied to individuals' actual, ideal, and ought selves, as per the self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987). The ideal self represents the characteristics an individual aspires to possess, the actual self reflects how a person perceives themselves, and the ought self pertains to the traits an individual believes they should have due to obligations. These three selves act as “self-guides” that influence individuals' behavior, with consistency enhancing motivation and conflicts potentially impeding it (Higgins, 1987). Teachers can utilize self-regulatory strategies and agency to address discrepancies, turning conflicts into catalysts for professional development (Gao and Xu, 2014).

Motivation is intricately connected to individuals' future-oriented self-concepts (Dörnyei, 2009). Self-concept, defined as “the summary of the individual's self-knowledge related to how the person views him/herself” (Dörnyei, 2009, p. 11), serves as a crucial analytical framework for behavior assessment and regulation (Markus and Nurius, 1986; Higgins, 1987). The interplay between individuals' beliefs and contextual influences can lead to alignment or contradiction among their different selves (Oyserman, 2001), influencing motivation and self-concept during teaching (Tao et al., 2019). The possible selves theory underscores the significance of desired selves that individuals aspire to become and feared selves they strive to avoid, shaping motivation and behavior (Markus and Nurius, 1986). Individuals may employ self-regulatory measures to bridge the gap between actual and desired selves, especially when desired selves align with feared selves. In the context of teaching, motivation can be compromised when teachers feel that their desired selves are constrained by unfavorable conditions, particularly when external expectations become internalized as part of their ought selves. This internalization can widen the discrepancy between their ideal and ought selves (Kubanyiova, 2009; Kumazawa, 2013). For instance, challenges like a rigid curriculum can conflict with teachers' aspirations, leading to demotivation (Yuan et al., 2016). Lee (2013) elaborates on this, noting how teachers may feel constrained by regulations, conforming to the role of “curriculum followers” despite aspiring to be “change agents.” Additionally, students' attitudes impact teacher motivation (Kubanyiova, 2009), with skepticism toward innovation reducing teachers' engagement (Yuan et al., 2016).

Despite a growing body of research on L2 teacher psychology (e.g., Dörnyei and Ushioda, 2013; Kubanyiova and Feryok, 2015; Mercer and Kostoulas, 2018), there has been a notable lack of focus on teacher motivation in the context of EFL generalist teachers (Lamb and Wyatt, 2019; Tao et al., 2019; Sato et al., 2022). Specifically, there is a gap in understanding the motivation of generalist teachers to teach EFL, particularly in Chinese rural primary schools where numerous challenges are prevalent. Delving into the motivation of L2 generalist teachers can elucidate the factors influencing their effectiveness in language instruction and how they overcome professional challenges. This study aims to address this gap by examining the motivation of L2 generalist teachers and how they navigate challenges in their roles. Drawing on theories like possible selves and self-discrepancy, the study seeks to understand how motivation is generated as well as how L2 generalist teachers respond to challenges encountered in teaching. The findings aim to inform policymakers and stakeholders about the professional development needs of these teachers, ultimately enhancing EFL education policies and teaching environments in rural areas. Two research questions guide the study:

1. What motivates/demotivates generalist teachers to deliver L2 instruction in elementary schools in rural China?

2. What teaching strategies do generalist teachers adopt to deliver L2 instruction?

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Context and participants

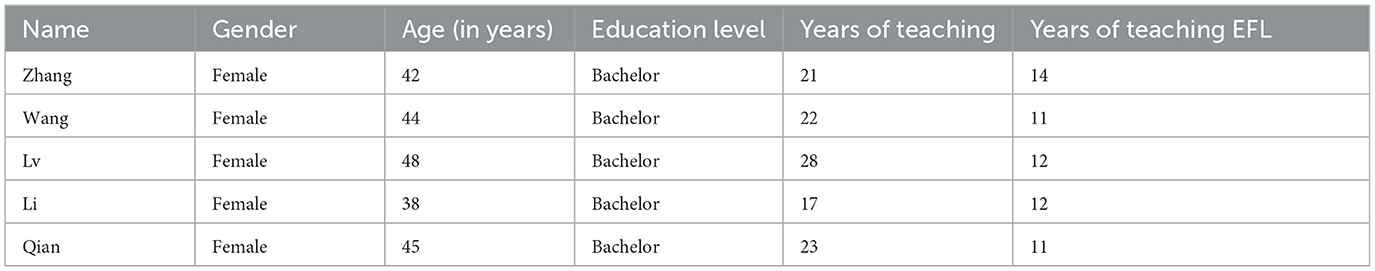

The study was inspired by the first researcher's firsthand teaching experiences in an impoverished area of Southwestern China. Conducted in a local rural elementary school, the research employed a convenience sampling method to recruit five L2 generalist teachers. All participants were natives of the area and taught in a rural elementary school characterized by limited educational resources. In this school, two teachers are responsible for delivering all subjects to a class of over 50 pupils, including classroom management, due to the absence of qualified teachers. The first researcher had prior professional cooperation with the participants for a year, establishing familiarity before data collection. While this connection may have influenced participant responses (Ravitch and Carl, 2016), it also facilitated deeper exploration into their motivation to teach language. All participants were female with over 10 years of teaching experience and reported receiving no pedagogical skills training on EFL instruction during college. See Table 1 for a summary of participant demographics.

2.2 Data collection

Considering our priorly established connections with the participants, a qualitative interview research technique was applied for our investigation, which depends “on developing rapport with participants and discussing, in detail, aspects of the particular phenomenon being studied” (deMarrais, 2004, p. 53). Five 50-min in-depth semi-structured interviews were carried out, during which data was gathered using an interview protocol comprising of six questions (see Appendix A). As recommended by Ravitch and Carl (2016), the semi-structured interview protocol involved asking targeted questions and adapting follow-up questions based on responses across interviews to create a personalized conversational experience for each participant. This approach allows for a nuanced and tailored understanding from the participants' perspective. Interviews were conducted in Chinese to allow the teachers to reflect on and voice their experiences, which were audio recorded for transcription after the participants' consent.

2.3 Data analysis

The data collected from interviews were transcribed verbatim, and qualitative content analysis (Miles and Huberman, 1994), was employed to analyze the data. Both a top-down (theory-driven) and a bottom-up (data-driven) approach were used to develop themes for investigation. The data underwent three rounds of review, spaced ~2 days apart. In the first review, the study identified participants' motivations toward their EFL teaching, noting that motivations initially stemmed from a desire to improve L2 knowledge and teaching skills but decreased during actual classroom teaching due to perceived limitations and contextual factors. In the second review, themes emerged regarding the causes of motivation fluctuations, including: (a) participants' declined motivations because of their perceived limitations in L2 competence and pedagogical skills, as well as factors such as student expectations, school policies, and language assessments; (b) increased motivations due to career aspirations and a sense of responsibility toward their students. Referring to self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987) and possible selves theory (Markus and Nurius, 1986), the third review further examined how motivation relates to different selves perceived by teachers during the teaching process (e.g., “a well-qualified and competent teacher,” “an omnipotent teacher,” “an exhausted and distracted teacher”). Meanwhile, the second researcher independently coded the same transcriptions, and subsequent discussions compared similarities and differences to ensure coding reliability. To validate findings, participants were invited for clarification and confirmation when uncertainties arose in data interpretation (e.g., ambiguous responses, conflicting information, missing or incomplete data).

3 Results

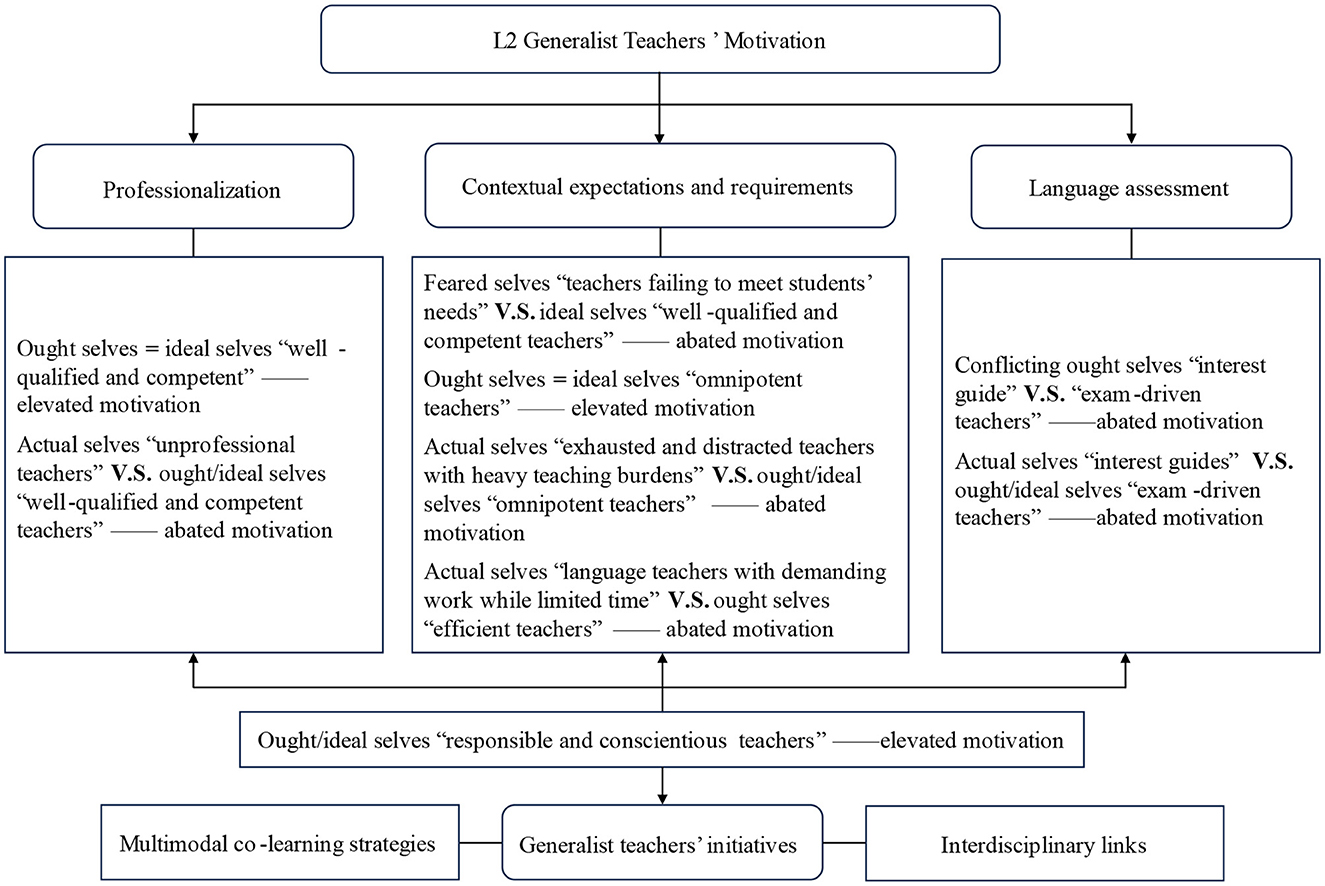

In this section, the study presents insights from participants Wang, Li, Lv, Qian, and Zhang, highlighting their diverse experiences as generalist teachers facing challenges such as limited language knowledge, self-efficacy issues, and balancing interest-oriented teaching with exam-driven demands. The section introduces four themes including “Professionalization,” “Contextual expectations and requirements,” “Language assessment,” and “Generalist teachers' initiatives,” setting the stage for a deeper exploration of these complex dynamics in English language teaching. The overall results are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The overall results. Abated motivation refers to a decline or reduction in L2 generalist teachers' motivation to teach EFL resulting from inconsistencies among their different selves; elevated motivation refers to an increase or enhancement in L2 generalist teachers' motivation to teach EFL due to alignment among their different selves.

3.1 Professionalization

In an examination-oriented environment, generalist teachers are expected to possess strong language knowledge and be competent in L2 instruction to achieve excellent outcomes. They also hold the aspiration of becoming “well-qualified and competent” (Li) in language teaching through their efforts. This convergence between their ought selves and ideal selves serves as a motivation for them to actively engage in training programs initiated by the school. Initially, their interest and passion for English drive their active participation in these training programs, as mentioned by Zhang: “I learned very carefully. I took a lot of notes and indeed learned some valuable knowledge and teaching methods.”

However, despite their efforts, generalist teachers still report lower L2 competence. Consequently, they face significant challenges in delivering “basic language knowledge and skills, including grammar, pronunciation, and listening” (Zhang). When asked about their educational experiences with English in college, most participants reveal that they received no training in L2 pedagogy, leading to limited knowledge about L2 instruction and less specialization in EFL teaching in L2 classrooms. Their low L2 competence makes it difficult for them to “effectively deliver L2 instructions” (Li). Additionally, they express deficiencies in technology use and struggle to search for pedagogical resources. For instance, Wang mentions difficulties in finding suitable and high-quality teaching resources, resulting in difficulties in managing a “well-organized class”.

This discrepancy between their actual selves as “unprofessional teachers” and their desired ought/ideal selves as “well-qualified and competent teachers” endorsed by school leaders creates a conflict. As a result, their teaching motivation is undermined, and they exhibit inadequate self-efficacy in EFL instruction, as mentioned by Wang: “I'm always worried about misleading students. I dare not say that I am qualified for English teaching and my confidence is not very sufficient. We could just try to complete the required teaching tasks.”

In summary, the professionalization of generalist teachers in language teaching faces several challenges, including limited language knowledge, deficiencies in L2 pedagogy training, technology use, and resource management. These challenges contribute to a discrepancy between their actual and ideal selves, leading to decreased motivation and self-efficacy in EFL instruction.

3.2 Contextual expectations and requirements

Within the teaching process, contextual factors significantly influence the motivation and self-concepts of L2 generalist teachers. One emerging sub-theme is the high expectations that students hold for their English teachers. Pupils in rural schools often assume that their teachers possess comprehensive knowledge and expertise, leading to heightened expectations (“Now these students simply assume that teachers know everything,” Lv). This places considerable pressure on generalist teachers, who worry about their language proficiency and fear not being able to meet students' future needs (“When they are in sixth grade, I'm afraid that my language proficiency is not enough to meet their needs at that time... Maybe it's embarrassing,” Lv). The fear of failing to satisfy students' expectations creates a feared teacher self as “teachers failing to meet students' needs,” contrasting with their ideal selves as “well-qualified and competent teachers,” thereby undermining their teaching motivation. As expressed by one participant, “I don't think I can teach them English for a very long time in the future. I'm teaching for now. That's all I can do” (Zhang).

Another sub-theme relates to the expectations imposed by school requirements and teaching situations. In rural schools with a shortage of English teachers, generalist teachers are assigned multiple teaching tasks and are assumed to be “omnipotent teachers” (Wang) to excel in all subjects (“I have to teach Chinese, English, Science and other subjects... I'm a little over my head,” Wang). Such expectations were elaborated into generalist teachers' ought/ideal selves. They initially made positive responses and promised a well-preparation for any subject which needed teaching: “A generalist teacher must be versatile and able to teach anything. I will follow the school's instructions, like a brick, where needed to move” (Li).

This heavy workload, however, can be overwhelming and distracting for teachers, leading to feelings of being overburdened and exhausted (“I have to cope with many affairs every day, and my energy is limited. I get distracted,” Wang; “Sometimes I am too busy to think and plan how to teach English…. Everything is being taught and nothing is being taught well,” Qian). The conflicting demands of various subjects can create a dissonance between teachers' actual selves “exhausted and distracted teachers with heavy teaching burdens” and their ideal selves as “omnipotent teachers”. Such dissonance affected their teaching motivation.

Furthermore, the restricted time allocated for English teaching in rural schools poses an additional challenge for generalist teachers. With only 80 min per week dedicated to English instruction, teachers struggle to deliver comprehensive and high-quality lessons within such a limited timeframe. Despite efforts to ensure efficient class delivery, generalist teachers find it frustrating and doubt the effectiveness of delivering L2 instruction within such constraints. Consequently, they label themselves as “language teachers with demanding work but limited time” (i.e., their actual selves), rather than their desired selves as “efficient teachers” (Li), which diminishes their motivation toward EFL teaching. As expressed by one participant, “I can feel only a little bit of sense of achievement in teaching in the class, which is reduced to almost zero in the next class” (Li).

In sum, the high expectations of students, the heavy workload imposed by school requirements, and the limited time for instruction all contribute to a mismatch between teachers' actual selves (or feared selves) and their ideal selves, leading to diminished motivation and hindering professional development in the field.

3.3 Language assessment

In rural school settings, generalist language teachers encounter challenges in maintaining their teaching motivation due to conflicting expectations and assessment methods. On one hand, they are tasked with being “interest guides,” fostering students' enthusiasm for English and creating a positive learning environment. However, the school's assessment system heavily emphasizes exams, prioritizing grades as the primary measure of language proficiency. This conflicting approach to language assessment creates a dilemma for generalist teachers, impacting their motivation and self-concept as educators. They grapple with the tension between their internalized ideal selves as “interest guides” and the reality of being perceived as “exam-driven teachers.” This conflict affects their teaching motivation and self-concept as educators. Wang, for instance, criticizes the negative impact of exam-oriented education on students' interest in learning English, expressing concerns about the detrimental effects of exams on students' enthusiasm for the subject. As Wang states, “The ‘baton' of the exam is too high... If there is no exam, it should not be difficult for us to deliver English lessons in primary schools in which students are more interested than now. The compulsory evaluation based on the written test may destroy students' interest in learning English.”

While they aspire to create engaging lessons that foster students' interests, they are compelled to follow the school's examination-driven pedagogy and “surrender to reality” (Li). Qian acknowledges the pressure to conform to the school's requirements, stating, “We have no choice but to follow the school's requirements. After all, the teaching quality would be assessed according to the students' grades... Maybe it is a little bit utilitarian. We teach what the test tests.” This conflict between their desired role as “interest guides” and the reality of being “exam-driven teachers” creates a discrepancy between teachers' actual selves and their ideal selves. Generalist teachers grapple with conflicting ought selves, oscillating between their aspirations to be “interest guides” and the demands of being “exam-driven teachers.” The misalignment between their actual selves as “exam-driven teachers” and their ought/ideal selves as “interest guides” undermines their teaching motivation. They fear their inability to organize engaging classes may result in a dull, exam-focused learning environment that fails to cultivate students' interest in language learning.

Overall, the conflicting expectations and assessments imposed on generalist teachers in rural schools create a challenging environment that hinders their teaching motivation. The tension between being an “interest guide” and an “exam-driven teacher” affects their self-concept and contributes to their ambiguous and low motivation levels.

3.4 Generalist teachers' initiatives

One significant initiative embraced by generalist teachers is the adoption of multimodal co-learning strategies in L2 classrooms. By incorporating multimedia tools such as PowerPoint presentations containing words, pictures, sounds, and videos, they actively engage students and cultivate an interactive learning environment. This approach not only “saved much time” (Li) and “reduced lots of pressure” (Wang) for teachers but also “created a relaxing environment” (Zhang) and heightened students' interest, leading to enhanced learning efficiency. For instance, Zhang shared how using PPTs with videos and songs made English lessons more interesting and memorable for students. The inclusion of visuals and multimedia elements helped students retain information better and fostered a relaxed classroom atmosphere where learning became engaging and enjoyable. Zhang also acknowledged the role of being a co-learner alongside the students, emphasizing the collaborative nature of the learning process.

Another significant initiative was the establishment of interdisciplinary links between English and other subjects to facilitate L2 teaching. Generalist teachers, such as Qian, excelled in connecting English with different subjects by exploring grammar, pronunciation, culture, and thinking patterns. By highlighting similarities and differences between English and Chinese, as illustrated by Li's teaching approach, teachers aimed to enhance students' understanding of English and promote memory retention through cross-subject reinforcement. Li, for example, frequently incorporated cultural comparisons between China and the West in her teaching to illustrate linguistic nuances and differences in thinking logic. By drawing parallels between emotional expressions in Western and Chinese cultures, she not only enriched students' cultural awareness but also provided valuable insights into language usage and communication styles.

In conclusion, generalist teachers' initiatives in EFL teaching encompassed the adoption of multimodal co-learning strategies and the establishment of interdisciplinary links between English and other subjects. Through these approaches, teachers aimed to create engaging learning experiences, enhance students' language proficiency, and foster a deeper understanding of English language and culture.

4 Discussion

This study delves into the experiences and motivations of L2 generalist teachers in teaching EFL in rural elementary schools. It reveals that the alignment and misalignment between various self-perceptions significantly impact their teaching motivation and approaches (Markus and Nurius, 1986; Higgins, 1987). Initially, these teachers aspire to become “well-qualified and competent” in EFL instruction, reflecting the expectations instilled by their schools, which serve as their “ought selves”. This alignment between their “ought selves” and their ideal selves as proficient educators serves as a driving force, prompting them to actively pursue training (Higgins, 1987). However, once in the classroom, they face the stark reality of being perceived as “unprofessional teachers” in contrast to their desired identity. This dissonance between their actual and ideal selves undermines their motivation. This may stem from the prevalent issue of underqualification among L2 generalist teachers in rural settings, where limitations in English proficiency and pedagogical skills hinder effective language instruction (Izquierdo et al., 2021).

During the teaching process, the motivation of L2 generalist teachers is often diminished by various contextual factors that impact their self-concepts and constrain their ideal selves (Markus and Nurius, 1986). Students' attitudes and expectations play a significant role in influencing teachers' motivation and self-perception (Kubanyiova, 2009). Despite students demonstrating positive attitudes toward English learning, their high expectations of generalist teachers expose them to considerable pressure due to the teachers' lack of L2 competence. The fear of failing to meet students' expectations creates a feared self-image of “teachers failing to meet students' needs” in contrast to their ideal selves as “well-qualified and competent teachers”, thereby undermining their teaching motivation and hindering innovation in EFL teaching within classrooms (Kubanyiova, 2009). Furthermore, teachers may experience demotivation when their ideal selves conflict with school requirements or the actual teaching environment (Kumazawa, 2013). Due to the shortage of L2 specialists, generalist teachers are often tasked with teaching multiple subjects, including EFL instruction, simultaneously, being expected by school leaders to be “omnipotent teachers”. As noted by Karimi and Norouzi (2019), teachers' commitment to teaching is influenced by the expectations set by school leaders. However, despite these expectations being integrated into L2 generalist teachers' “ought selves”, they often find themselves easily distracted and burnt out during the teaching process due to the heavy workload, shaping their actual selves as “exhausted and distracted teachers burdened with heavy teaching responsibilities”. Consequently, the dissonance between their “ought selves” and actual selves leads to a decline in teaching motivation. Moreover, the reality of generalist teachers' actual selves as “language teachers with demanding work and limited time” contradicts their “ought selves” as “efficient teachers”, further diminishing their motivation toward L2 instruction. Thus, the inconsistencies triggered by adverse contextual factors can weaken teachers' motivation and impede their professional development (Kubanyiova, 2009).

In rural schools, language teachers' aspirations toward idealized teaching practices are often hindered by contextual challenges, leading to fluctuations in their teaching motivation (Gao and Xu, 2014). One significant issue lies in the ambivalence and ambiguity surrounding the language ideology and policy within these schools, particularly concerning L2 assessment. L2 generalist teachers find themselves caught in a dilemma; while they may not personally identify with exam-driven policies, they are compelled to adhere to them due to contextual pressures. Consequently, these teachers are confronted with paradoxical and conflicting school policies, which force them into a struggle between their externally imposed “ought selves” and their internally held “ought/ideal selves”. For instance, they may feel torn between being guided by their interests in effective language instruction and being compelled to prioritize exam-oriented teaching practices (Yuan et al., 2016). This tension significantly demotivates their efforts in EFL teaching, as they grapple with the conflicting demands placed upon them by school policies.

According to Higgins (1987), the alignment between ideal and ought selves is crucial in bolstering teachers' motivation toward L2 instruction. Despite facing numerous challenges during EFL teaching that contribute to low motivation, generalist teachers demonstrate a strong sense of responsibility toward their students and aspire to be “responsible and conscientious teachers” (ought selves), consistent with their ideal selves as “well-qualified and competent teachers”. Consequently, they strive to minimize the disparity between their ought/ideal selves and their actual selves, seeking out teaching approaches to facilitate students' EFL learning. Despite limited information and technology capabilities due to a lack of training (Hossain, 2016), these teachers are still able to utilize basic office applications such as PowerPoints with existing resources, contradicting previous findings suggesting their reluctance to adopt technology-enhanced materials (Izquierdo et al., 2021). Such technology-based aids are believed to enhance learning experiences by providing real-life experiences that stimulate self-activity and imagination (Hossain, 2016), thus exposing L2 learners to meaningful language input and output (Izquierdo et al., 2021). Furthermore, generalist teachers establish interdisciplinary links and particularly emphasize cross-linguistic connections to facilitate L2 learning, as emphasizing common features may enhance performance in both languages (Cummins, 2005). By employing effective techniques to aid students' EFL learning and realizing their ideal selves, these teachers experience a sense of fulfillment and contentment, which in turn enhances their motivation (Dörnyei and Ushioda, 2013).

4.1 Implications for practices

The study's findings have important implications, particularly in rural areas where generalist teachers lack expertise in teaching an L2. Educational administrators should take the lead in providing high-quality training to improve teachers' L2 competence and teaching skills. Encouraging generalist teachers to engage with L2 specialists and participate in professional activities (Johnson, 2009) can help them develop their L2 knowledge and teaching abilities, as well as reflect on challenges, identify coping mechanisms, and build a positive self-concept with strong motivation for L2 teaching (Yuan et al., 2016). In pre-service training, teacher educators should offer specialized courses to enhance L2 competence and pedagogical skills, which can be directly applied in rural schools to better prepare teachers for L2 instruction. It is also essential to invest additional resources and efforts, alongside incentives and competitive salaries, in developing sustainable teachers' networks or communities for ongoing professional development (Gao and Xu, 2014). The study also highlights the disparity experienced by L2 generalist teachers due to conflicting and ambiguous school policies, leading to reduced teaching motivation (Yuan et al., 2016). School administrators should strive to provide clear and consistent mandates, while policymakers and school leaders must actively engage with these teachers to understand and address the contextual constraints and challenges they face. Building mutual understanding and respect through open communication and negotiation is crucial (Burns, 2009), rather than imposing over-idealized demands and becoming disconnected from the realities faced by teachers.

4.2 Limitations

It is indeed crucial to acknowledge the limitations of the study. One notable limitation of this study is the small sample size, comprising only five L2 generalist teachers from rural elementary schools. Future research should aim to include a larger and more diverse sample, spanning various geographical locations and educational contexts. Another limitation lies in the exclusive reliance on interview data. Future research could strengthen validity and reliability by integrating interviews with additional methods like classroom observations or surveys to triangulate data. Finally, the absence of computed inter-rater reliability statistics serves as a limitation. It is recommended that future research prioritize the assessment of inter-rater reliability to ensure the consistency and validity of qualitative data analysis.

5 Conclusion

In summary, this qualitative study delves into the relationship between L2 generalist teachers' teaching motivation, self-concepts, and responses to challenges in rural Chinese elementary schools. While the convergence between teachers' ought selves and ideal selves motivates active engagement in L2 teaching, non-professionalization and high contextual expectations lead to a decline in motivation. Ambiguous school policies further complicate matters. Despite these challenges, teachers' commitment to students drives them to innovate within their abilities. Addressing these findings underscores the importance of supporting rural L2 generalist teachers' professional development to enhance teaching quality and student outcomes in EFL education.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

WS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. HS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Science Foundation of China University of Petroleum, Beijing [grant number ZX20230108].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acheson, K., Taylor, J., and Luna, K. (2016). The burnout spiral: the emotion labor of five rural U.S. foreign language teachers. Mod. Lang. J. 100, 527–537. doi: 10.1111/modl.12333

Burns, A. (2009). “Action research in second language teacher education,” in The Cambridge Guide to Second Language Teacher Education, eds A. Burns, and J. C. Richards (Cambridge: Cambridge University), 289–297.

Coelho, F., and Henze, R. (2014). English for what? Rural Nicaraguan teachers' local responses to national educational policy. Lang. Policy 13, 145–163. doi: 10.1007/s10993-013-9309-4

Corbett, L., Phongsavan, P., Peralta, L. R., and Bauman, A. (2021). Understanding the characteristics of professional development programs for teachers' health and wellbeing: implications for research and practice. Aust. J. Educ. 65, 139–152. doi: 10.1177/00049441211003429

Cummins, J. (2005). “Teaching for cross-language transfer in dual language education: possibilities and pitfalls,” in Paper presented at TESOL Symposium on Dual Language Education: Teaching and Learning Two Languages in the EFL Setting (Istanbul: Bogaziçi University).

deMarrais, K. B. (2004). “Qualitative interview studies: Learning through experience,” in Foundations for Research: Methods of Inquiry in Education and the Social Sciences, eds K. deMarrais, and S. D. Lapan (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum), 51–68.

Dörnyei, Z. (2009). “The L2 motivational self-system,” in Motivation, Language, Identity, and the L2 Self, eds Z. Dörnyei, and E. Ushioda (Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters), 9–42.

Dörnyei, Z., and Kubanyiova, M. (2014). Motivating Learners, Motivating Teachers: Building Vision in the Language Classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gao, X., and Xu, H. (2014). The dilemma of being English language teachers: interpreting teachers' motivation to teach, and professional commitment in China's hinterland regions. Lang. Teach. Res. 18, 152–168. doi: 10.1177/1362168813505938

Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self-discrepancy: a theory relating self and affect. Psychol. Rev. 94, 319–340. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.319

Hossain, M. (2016). English language teaching in rural areas: a scenario and problems and prospects in context of Bangladesh. Adv. Lang. Liter. Stud. 7, 1–12. doi: 10.7575/aiac.alls.v.7n.3p.1

Izquierdo, J., Zuniga, S. P. A., and Garcia, V. (2021). Foreign language education in rural schools: Struggles and initiatives among generalist teachers teaching English in Mexico. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 11, 133–156. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2021.11.1.6

Johnson, K. E. (2009). Second Language Teacher Education: A Sociocultural Perspective. New York, NY: Routledge.

Karimi, M. N., and Norouzi, M. (2019). Developing and validating three measures of possible language teacher selves. Stud. Educ. Eval. 62, 46–60. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2019.04.006

Kubanyiova, M. (2009). “Possible selves in language teacher development,” in Motivation, Language Identity and the L2 Self, eds Z. Dörnyei, and E. Ushioda (Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters), 314–332.

Kubanyiova, M., and Feryok, A. (2015). Language teacher cognition in applied linguistics research: revisiting the territory, redrawing the boundaries, reclaiming the relevance. Mod. Lang. J. 99, 435–449. doi: 10.1111/modl.12239

Kumazawa, M. (2013). Gaps too large: four novice EFL teachers' self-concept and motivation. Teach. Teach. Educ. 33, 45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2013.02.005

Lamb, M., and Wyatt, M. (2019). “Teacher motivation: the missing ingredient in teacher education,” in The Routledge Handbook of Language Teacher Education, eds S. Mann, and S. Walsh (London: Routledge), 522–535.

Lee, I. (2013). Becoming a writing teacher: using “identity” as an analytic lens to understand EFL writing teachers' development. J. Sec. Lang. Writ. 22, 330–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2012.07.001

Li, J., Shi, Z., and Xue, E. (2020). The problems, needs and strategies of rural teacher development at deep poverty areas in China: rural schooling stakeholder perspectives. Int. J. Educ. Res. 99:101496. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2019.101496

Liu, H., Chu, W., Fang, F., and Elyas, T. (2021). Examining the professional quality of experienced EFL teachers for their sustainable career trajectories in rural areas in China. Sustainability 13:10054. doi: 10.3390/su131810054

Markus, H., and Nurius, P. (1986). Possible selves. Am. Psychol. 41, 954–969. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.41.9.954

Mercer, S., and Kostoulas, A. (2018). Language Teacher Psychology. Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters.

Miles, M. B., and Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Oyserman, D. (2001). “Self-concept and identity,” in The Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology, eds A. Tesser, and N. Schwarz (Malden, MA: Blackwell), 499–517.

Ravitch, S. M., and Carl, N. M. (2016). Qualitative Research: Bridging the Conceptual, Theoretical, and Methodological. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Sato, M., Fernández Castillo, F., and Oyanedel, J. C. (2022). Teacher motivation and burnout of english-as-a-foreign-language teachers: do demotivators really demotivate them? Front. Psychol. 13:891452. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.891452

Sinclair, C. (2008). Initial and changing student teacher motivation and commitment to teaching. Asia Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 36, 79–104. doi: 10.1080/13598660801971658

Tao, J., Zhao, K., and Chen, X. (2019). The motivation and professional self of teachers teaching languages other than English in a Chinese university. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 40, 633–646. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2019.1571075

Wang, X., and Chen, Z. (2022). “It hits the spot”: the impact of a professional development program on english teacher wellbeing in underdeveloped regions. Front. Psychol. 13:848322. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.848322

Yuan, R., Sun, P. P., and Teng, L. S. (2016). Understanding language teachers' motivation towards research. TESOL Q. 50, 220–234. doi: 10.1002/tesq.279

Appendix A

Interview protocol

1. Have you learned English or some L2 pedagogies in the college? Are you interested in English or English teaching? Why?

2. What are your perceptions of generalist teachers and the teaching profession?

3. What are your perceptions of specialized English language teachers and L2 generalist teachers?

4. How did you come to have such perceptions?

5. Can you describe your teaching experiences before and after being a L2 generalist teacher? What challenges have you encountered? How did you cope with them?

6. How did you implement your L2 teaching plan? What teaching strategies did you adopt?

Keywords: EFL teaching, teaching motivation, pedagogical strategies, rural L2 generalist teachers, self-concepts

Citation: Sun W and Shi H (2024) Understanding L2 generalist teachers' motivation for teaching EFL in China's rural elementary schools. Front. Educ. 9:1334031. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1334031

Received: 06 November 2023; Accepted: 08 April 2024;

Published: 19 April 2024.

Edited by:

Henri Tilga, University of Tartu, EstoniaReviewed by:

Cheryl J. Craig, Texas A&M University, United StatesAyşenur Alp Christ, University of Zurich, Switzerland

Copyright © 2024 Sun and Shi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wei Sun, c3djdXAxOTk4JiN4MDAwNDA7MTYzLmNvbQ==; Hong Shi, c2hpaG9uZzIwMDVzZCYjeDAwMDQwOzE2My5jb20=

†These authors share first authorship

Wei Sun

Wei Sun Hong Shi

Hong Shi