- 1Department of Community and Education, Kinneret Academic College, Kinneret, Israel

- 2Faculty of Instructional Technologies, Holon Institute of Technology, Holon, Israel

Can we celebrate multiculturalism through teachers’ training in a heterogeneous and diverse setting such as Israeli society? The current study examines teachers’ processes through an online teachers’ professional development program and an interactive activity, where 68 Israeli teachers shared their cultural stories with teachers from other cultures. Findings indicate that the teachers who met with teachers from other cultures, whom they usually do not meet, wanted to learn about each other’s culture, including their religious values, practices, and traditions while looking for commonalities. Furthermore, such intercultural meetings can occur online if the activities are designed to foster meaningful meetings and discussions between different cultures despite the social rifts and the separation within the education system.

1 Introduction

Many nation-states worldwide have condemned multiculturalism as a failure by national leaders and citizens (Fincher et al., 2014; Kymlicka, 2015; Simonsen and Bonikowski, 2020). Simultaneously, categories such as “them and us,” “ingroup and outgroup,” “home and away,” and “east and west’ remain common terms used to create psychological distance among people, nations, and continents (Kinnvall and Lindén, 2010;Suleiman et al., 2018; Leszczensky and Pink, 2019).

However, diversity is an undeniable fact. People within countries are diverse in many aspects, such as race, ethnicity, gender, age, family, and disabilities ( Banks and Banks, 2019; Dhiman et al., 2019; Ghazaie et al., 2021; Aylward and Mitten, 2022). Under such circumstances, managing diversity effectively is crucial in general and in the education system in particular. For example, celebrating diversity is the key to greater productivity, increased creativity, and heightened workplace morale and motivation. Embracing diversity in business implies that companies will achieve greater profitability and efficiency when employees from various disciplines and cultural and ethical backgrounds contribute to their operations (Dhiman et al., 2019). Urban areas can break segregation and turn diversity into a creative force for innovation, growth, wellbeing, and safe places for the residents (Fincher et al., 2014). The European Commission in Ghazaie et al., (2021) states that the challenge for the cities of tomorrow lies in breaking segregation and turning diversity into a creative force for innovation, growth, and wellbeing. Within this, social inclusion in schools is an important goal, supporting social–emotional and academic success for all students (Walsh et al., 2015; Pizmony-Levy and Kosciw, 2016; Hymel and Katz, 2019).

Israel is an example of a diverse and multifaceted society, and its public education system is composed of multiple cultures and, sometimes, deep social-cultural rifts (Sabbagh and Resh, 2014; van de Weerd, 2020). Particularly, Israel’s public education system is divided into a Hebrew-speaking system, which is again divided into several subsystems (secular schools, religious schools, and independent ultra-religious schools), and an Arabic-speaking system (for Muslims, Christians, Druze and other minorities) (Agbaria, 2018; Abu-Saad, 2019). As a result, secular, religious, ultra-orthodox, and Arab teachers rarely meet or work together. Furthermore, students from these groups do not often meet or know each other. Under such circumstances, there is a need to improve intergroup relations and make sure teachers and students will get to know each other’s culture.

Scholars found it is possible to improve intercultural relations and celebrate diversity and societal multiculturalism through intergroup contact and meetings between cultures under appropriate conditions, face-to-face and online (Dovidio et al., 2011; Pettigrew et al., 2011; Vezzali et al., 2014; Shapira et al., 2021). Thus, we based the current research on the assumption that we can foster a multicultural approach and celebrate diversity in the Israeli education system through meetings and discussions among teachers from different cultures as the first phase before meetings among the students. Another assumption is that the meetings themselves are not enough. The teachers should meet, discuss, and learn about other teachers’ core cultural components (Spencer-Oatey, 2012; Hidalgo, 2013 ; Sever, 2016). Moreover, these meetings and discussions can occur online, considering the separation in the Israeli educational system and the promise by scholars that online contact can improve intercultural relations (Shapira et al., 2021).

To foster meaningful meetings and dialog between teachers in Israeli society, we designed a Teachers’ Professional Development (TPD) program called “Educators for Shared Society.”

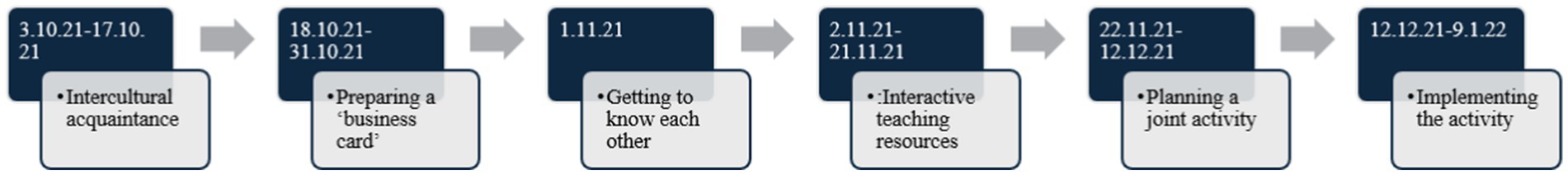

The current study outlines the entire TPD program process (see Figure 1 and the method section) and highlights the initial phase: a session conducted through an interactive presentation.

First, we aimed to identify the changes in teachers’ attitudes toward multiculturalism before and after they participated in the Teacher Professional Development (TPD) program. Additionally, we aimed to investigate the cultural elements that emerged during interactive activities within the TPD program. Finally, we examined the nature and dynamics of interactions among teachers throughout the program, focusing on how these interactions influenced their perceptions and practices related to multicultural education.

2 Literature background

2.1 Peripheral and core cultural components

Culture is a complex and multifaceted concept encompassing the knowledge, beliefs, arts, morals, laws, customs, and other capabilities and habits acquired by individuals as members of society (Baldwin et al., 2006; Spencer-Oatey, 2012). The elements or components of culture manifest at different layers of depth: observable artifacts (e.g., physical layout, dress code), also known as peripheral cultural components (Spencer-Oatey, 2012; Sever, 2016), and hidden elements encompassing values (e.g., ideals and rationalizations for behavior), and basic underlying assumptions (e.g., deeply ingrained beliefs and perceptions, also known as core cultural components) (Spencer-Oatey, 2012; Sever, 2016). Indeed, defining culture is challenging due to its complexity and the wide range of perspectives, including internal mental constructs and external observable behaviors. Various scholars have proposed numerous definitions, leading to inconsistencies and sometimes disagreements. To address this, Jahoda (2012) suggests using the term “culture” flexibly without a rigid definition and providing specific explanations in theoretical or empirical contexts to clarify its meaning. Therefore, in the current study, we explain culture through both core (hidden, internal mental constructs), and peripheral (visible and external observable behaviors) cultural components (Spencer-Oatey, 2012; Sever, 2016). We also look at the attitudes toward core and peripheral cultural components in a diverse society.

According to Banks and Banks (2019) Culture can be understood as a group program for survival and adaptation to the group surroundings, which includes the knowledge, concepts, values, shared beliefs, symbols, and interpretations shared by the group. However, the essence of a group is not its artifacts, tools, or tangible elements but rather how the group members agree to use, perceive, and interpret them (Banks and Banks, 2019). As a result, to understand what culture is, we should distinguish three levels: (a) visible artifacts, (b) values, and (c) basic underlying assumptions.

The visible artifacts include physical layout, dress code, how people address each other, the smell and feel of a place, the emotional intensity of a place, and other phenomena. However, this only refers to how things look, not why a group behaves the way it does (Spencer-Oatey, 2012). So, we observe only the peripheral components of the group, such as folk music, clothing, ethnic food, and hairstyles (Sever, 2016).

To analyze why group members behave the way they do, we should look for the values that govern behavior. Values give people reasons for behaving in a certain way and can often be used to explain certain behaviors (Spencer-Oatey, 2012).

To deeply understand a culture and ascertain more completely the group’s values and overall behavior, it is imperative to delve into the underlying assumptions of the group, which are typically unconscious but determine how group members perceive, think, and feel. Assumptions are ultimate, non-debatable, taken-for-granted values (Spencer-Oatey, 2012). Similarly, Hidalgo (2013) and Sever (2016) identify core cultural values such as language, family, religion, beliefs, and assumptions. Moreover, multicultural societies should wish to learn about and understand core cultural values (Spencer-Oatey, 2012; Sever, 2016).

In other words, the core cultural components include the basic underlying assumptions common to a particular group, such as language, educational concepts, norms, teaching methods, family patterns, leisure patterns, values, and goals. Visible artifacts such as food, holidays, clothing, and appearance are the peripheral components of culture.

Here, research must be extended to solidify the importance of the multicultural approach and expand our understanding of others’ core cultural components. Thus, we should strive to foster education among teachers for a multicultural approach through the encounter with the core components of different cultures.

2.2 Multicultural education

Multicultural education states that all students, regardless of group, should experience education equality and have an equal chance to experience school success. These groups include gender, ethnicity, race, culture, language, social class, religion, sexual orientation, or another exceptionality. A primary goal of multicultural education is to help all students develop the knowledge, attitudes, and skills needed to function within their culture, their society, and the global community (Banks and Banks, 2019).

Multicultural education views schools as a social system comprising highly interrelated parts and variables. These parts include the school staff’s attitudes, perceptions, beliefs, and actions; teaching styles and strategies; the curriculum and course of study; instructional materials; assessment and testing procedures; learning styles of the school; and languages and dialects in the school (Banks and Banks, 2019).

Here, the primary responsibility for multicultural education and changing the dynamic of exclusion and racism in the education system is placed on adults, especially teachers (Bennett, 2017; DeJaeghere and Zhang, 2008; Villegas et al., 2012). In this, teachers with intercultural competence and multicultural experiences have positive beliefs and approaches to cultural diversity (DeJaeghere and Zhang, 2008; Dusi et al., 2017; Jokikokko, 2005). These teachers have the comprehensive ability to understand, think, communicate, and interact in different ways regarding culture and from many perspectives (Shapira and Mola, 2022; Cusher and Mahon, 2009).

However, education systems in many countries continue to be characterized by group disparities. In countries such as the United States, New Zealand, China, and Israel, disparities exist between dominant and nondominant groups (Agbaria, 2018; Parkhouse et al., 2019; Walsh et al., 2015). Simultaneously, many teachers feel underprepared to work in culturally diverse classrooms (Parkhouse et al., 2019). Therefore, the need to develop teachers’ intercultural skills and abilities to act in a heterogeneous classroom underlines the importance of multicultural education for the school staff.

2.2.1 Teachers’ professional development programs in multicultural education

Scholars agree that meaningful learning opportunities must first be offered to teachers before they can provide meaningful learning opportunities for their students (Shapira, 2016; Jennings and Greenberg, 2009; Natividad Beltrán del Río, 2021; Osher et al., 2016).

Scholars have suggested different models of TPD programs. For example, Borko (2004) proposed key elements that should comprise TPD programs: (1) The program in general; (2) The teachers who are the learners in the system; (3) The facilitator who guides teachers as they construct new knowledge and practices; and (4) The context in which the professional development occurs. Darling-Hammond (2017) mentioned that we should provide teachers with an opportunity to engage in the same way of learning they are implementing among their students. Moreover, teachers who teach character and moral virtues often act as role models for their students (Lumpkin, 2008). Therefore, teachers should develop their skills and undergo a stage of personal development, “teachers as learners,” before cultivating different skills in the classroom (Shapira, 2016; Jennings and Greenberg, 2009; Osher et al., 2016). In the current study context, we assume that teachers need to develop their own emotional skills, such as multicultural awareness and intercultural sensitivity (Shapira and Mola, 2022).

Another assumption is that these processes can happen online. Research indicates that indirect contact can elicit positive intercultural attitudes, given the proper conditions, especially in a segregated society with segregated schools (Agbaria, 2018; Parkhouse et al., 2019; Walsh et al., 2015). Two studies (Shapira et al., 2021; Shapira and Amzalag, 2021) have examined an online TPD designed to support meaningful acquaintance and reduce stereotypes and prejudices among teachers from different cultures in Israeli society. The findings indicate that teachers who live and study in a diverse and divided society, such as Israel, can improve intercultural relations using online contact with teachers from other groups they usually do not meet. This contact may lead to a significant acquaintance, which, in turn, prepares teachers as agents of change in the field of multicultural education (Shapira et al., 2021; Shapira and Amzalag, 2021).

Therefore, we sought to provide teachers with a meaningful online learning experience about multiculturalism as a social and emotional skill to help them develop similar processes among their students as role models. To do so, we encouraged teachers from diverse Israeli societies to know and understand each other’s core cultural components and values and discuss them through an interactive presentation.

Three research questions guided our study:

1. What changes occurred in the teachers’ attitudes regarding multiculturalism following their participation in the TPD program?

2. What cultural characteristics emerged in the interactive activity during the TPD program?

3. What characterizes the connection among the teachers during the TPD program?

3 Methodology

This study combines quantitative and qualitative data to provide a rich and comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon investigated (Cohen et al., 2018). We conducted our research as part of an online TPD program from October to January (2021–2022). This program was published at the Center for Educational Technology (CET) in Tel Aviv, Israel.

3.1 Participants

A total of 91 teachers started the TPD program, and 68 completed the program (14 men and 54 women). The average participant age was 40.12 years (S.D = 9.8). Most of the participants teach in Jewish state schools (74%), 15% teach in Arab state schools, 6% teach in Jewish religious public schools, 2% in orthodox schools, and 3% in other kinds of schools. 31 participants teach in elementary schools and the remainder in junior and high schools. 25 participants teach science or mathematics, and 43 teach humanities. Most participants (56%) have a bachelor’s degree, 38% have advanced degrees, and all the others have a teaching certificate.

3.2 TPD program design

The TPD program includes synchronous and asynchronous meetings. During the synchronous meetings, the teachers get to know each other online, learn about teaching resources in multicultural education, and design and implement a program for their students. Figure 1 presents the TPD program timeline.

The description of the meeting types and assignments:

First assignment (asynchronous): Intercultural acquaintance: an explanation outlined what the core and peripheral components of culture are. Each teacher was asked to add a slide and a picture representing their culture, write about the picture, and respond to two teachers from other cultures.

Second assignment (asynchronous): Preparing a “business card” including details about the teacher, school, profession, how they would like to implement meetings with colleagues from another school, etc.

Third assignment (synchronous): Getting to know each other:

1. Heterogenous groups used culture cards (created by TEC, Mofet Institute) presenting illustrations and texts that characterize different cultures, such as weddings, choosing a name for a baby, attitude toward an older person, and getting to know spouses. The teachers chose a card and spoke with each other about their culture.

2. Selection of partners for implementing meetings between the schools.

3. Lecture on different possibilities for a meeting between cultures.

Fourth assignment (asynchronous): Getting to know interactive teaching resources for multicultural education.

Fifth assignment (asynchronous): Planning a joint activity with colleagues from the partner schools to foster a shared society.

Sixth assignment (in class): Implementing the activity the teachers planned in their classroom and report it in the forum: what they did in class, how their students responded, whether they achieved the goal of the activity, and more.

3.3 Data-collection and data-analysis methods

We utilized quantitative data from 68 respondents on both pre- (91 responses) and post-questionnaires (68 responses) and conducted factor analysis, frequency tests, and paired sample t-tests using SPSS. Additionally, we analyzed qualitative data from the slides of 86 participants who appeared in a collaborative presentation. Using Narralizer software,1 we divided the textual content into themes and sub-themes. We also analyzed the pictures that participants uploaded to the collaborative presentation. The purpose of these images was to provide a visual example of the text they wrote, and therefore, the pictures analysis was conducted according to the themes identified in the textual content analysis.

To ensure the reliability of the qualitative data (text and pictures), we analyzed all participants’ slides together. The joint analysis allowed us to discuss each analyzed content unit in real time, discuss with each other when disagreements arose until reaching a consensus, and refine the themes based on these discussions.

3.4 Research tools

3.4.1 Questionnaire

We used a pre-and-post-questionnaire which consisted of two parts: (1) Demographic backgrounds, such as gender, age, seniority in teaching, and main field of teaching and (2) Positive attitudes toward Multiculturalism, such as: “In my opinion, it is not a bad thing to marry someone from a different culture,” “My culture influences my beliefs and attitudes,” and Cultural influence such as: “My culture influences my behavior.”

All the items are the same in the pre-and post-questionnaire. The items are based on Maruyama et al. (2000), Pohan and Aguilar (2001), Rew et al. (2003), and Holladay et al. (2003). All the items except demographic background used a Likert scale (1 = not true at all; 5 = very true). Several items were eliminated because their inclusion resulted in unsatisfactory Cronbach’s alpha (α) values. The pre-questionnaire demonstrated a reliability coefficient of α = 0.64, while the post-questionnaire exhibited a reliability coefficient of α = 0.71.

3.4.2 Slide content analysis

The content analysis approach we used was both deductive (top-down) and inductive (bottom-up) (Bingham, 2023). Our deductive analysis was based on core and peripheral cultural components (Sever, 2016; Spencer-Oatey, 2012). Both researchers analyzed all the slides’ contents together.

3.5 Ethics

The college’s Ethics Committee approved this research (ETHICS/40/2022). The participants gave their informed consent to participate in the study. Moreover, all the data appear in a closed online environment (Moodle platform) with a username and password. We also ensured the participants’ photos could not be identified by hiding their faces.

4 Results

RQ1: What changes occurred in the teachers’ attitudes regarding multiculturalism before and after the TPD program?

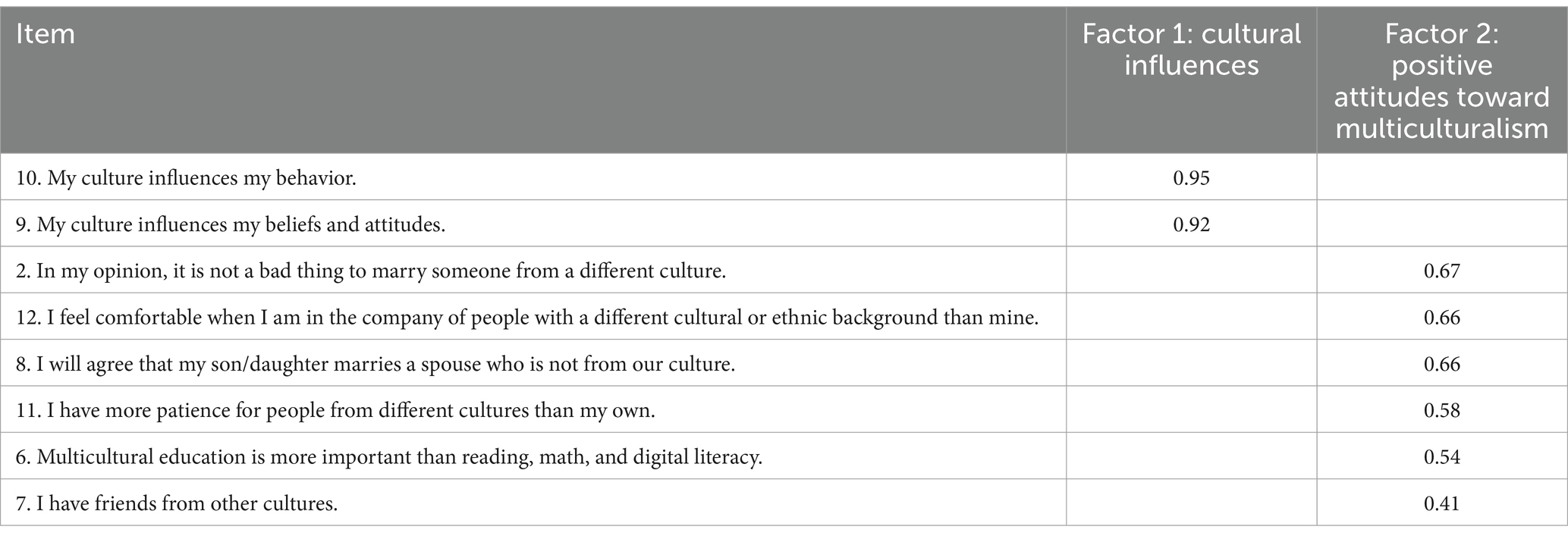

First, we used Factor analysis to indicate research variables, as presented in Table 1:

The factor analysis identified two variables: Cultural influences and positive attitudes toward Multiculturalism. The analysis showed strong loadings on Factor 1 and moderate loadings on Factor 2. To answer this RQ, we used paired sample t-tests.2

Our findings indicate that teachers’ positive attitudes toward multiculturalism were initially high. Indeed, there were no significant differences in these attitudes between the pre-and post-questionnaires (for example, the average pre-positive attitude toward Multiculturalism is 3.958, and the average post-positive attitude toward Multiculturalism is 3.951). Additionally, teachers’ behaviors and beliefs were moderately influenced by their culture (for example, the average pre-cultural influence is 3.596). These behaviors and beliefs did not change following the TPD program (the average post-cultural influence barely changed and stood at 3.552). In both variables, no significant differences were found (p > 0.05).

RQ2: What cultural characteristics appeared in the interactive activity during the TPD program?

To address this research question, we employed content analysis. First, we looked at core and peripheral components (Sever, 2016; Spencer-Oatey, 2012).

Our content analysis reveals only core components.

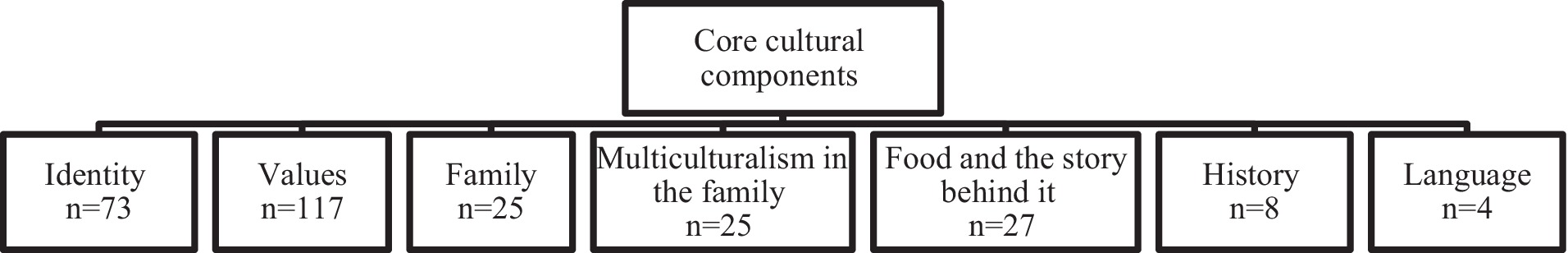

Several core themes emerged from the data analysis of the text and pictures: identity, values, multiculturalism in the family, food and the story behind it, history, and language (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Core components themes. The numbers represent the number of quotes that emerged for each sub-theme, and therefore, there may be instances where the same participant is counted more than once.

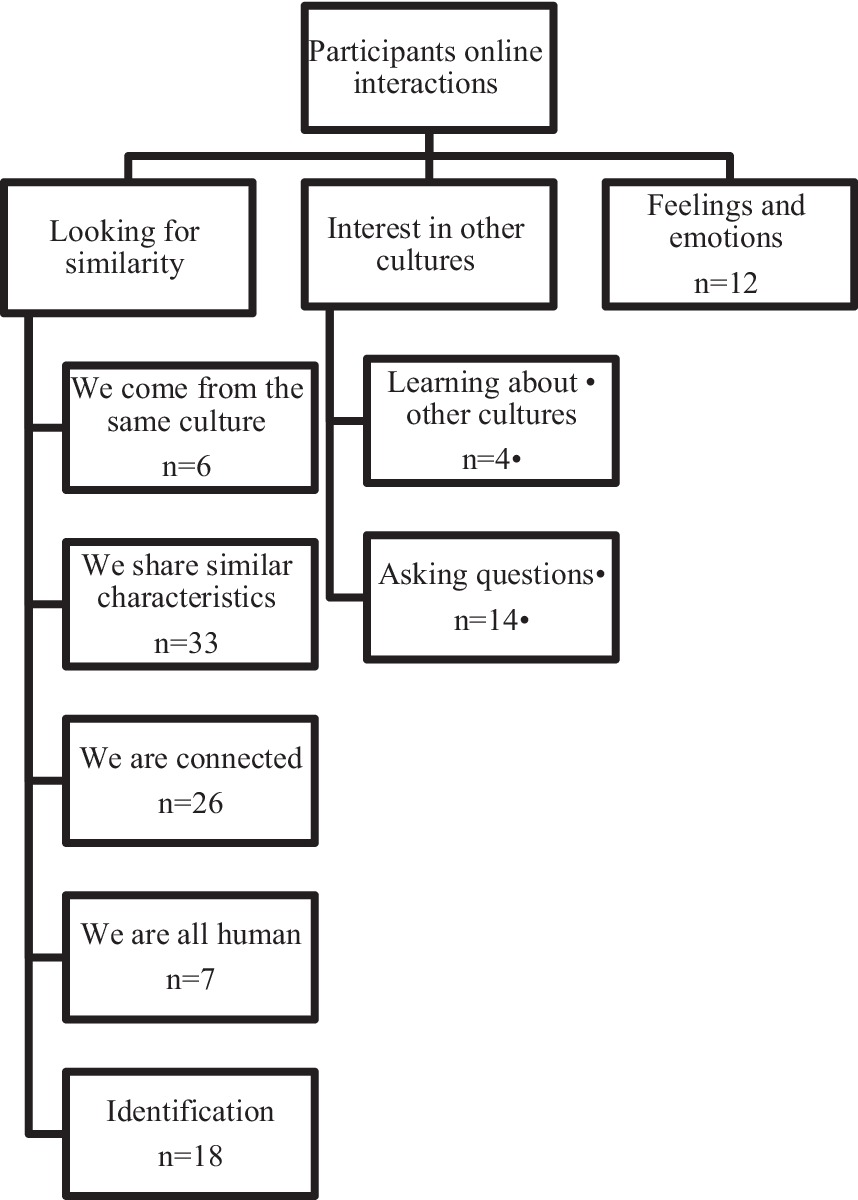

The virtual dialog created among the TPD participants as part of writing responses to the core cultural components of other teachers, on which we performed content analysis (see section 3.3), raised three themes (looking for similarity, interest in other cultures, and feelings and emotions) and seven sub-themes (such as: we come from the same culture, we share similar characteristics, learning about other cultures) as presented in Figure 3:

Figure 3. Online interaction themes and sub-themes. The numbers represent the number of quotes that emerged for each sub-theme, and therefore, there may be instances where the same participant is counted more than once.

4.1 Identity

Below, we present the Arab teachers’ quotes first and then the Jewish teachers’ quotes.

I am an Arab Muslim who behaves according to the Arab culture and the Islamic religion. (S, M, A)3

My name is Dr. N from Kfar Kasem (an Arab village)… I believe that I am a citizen of the world … I respect all citizens worldwide as I expect them to treat me. I try to preserve my culture, which is Islamic Arab culture. (N, M, A)

Interestingly, all participants identified themselves as Muslim Arabs, while only one added that he is a Muslim Arab and a citizen of the world.

Compared with the Arab participants, some Jewish participants defined themselves as Israeli or both Jews and Israelis, as can be seen in the following quotes:

I define myself as Israeli for everything… I am a vegetarian, feminist, and humanist. (S, F, J)

I feel the most connected to being Jewish and Israeli. (J, M, J)

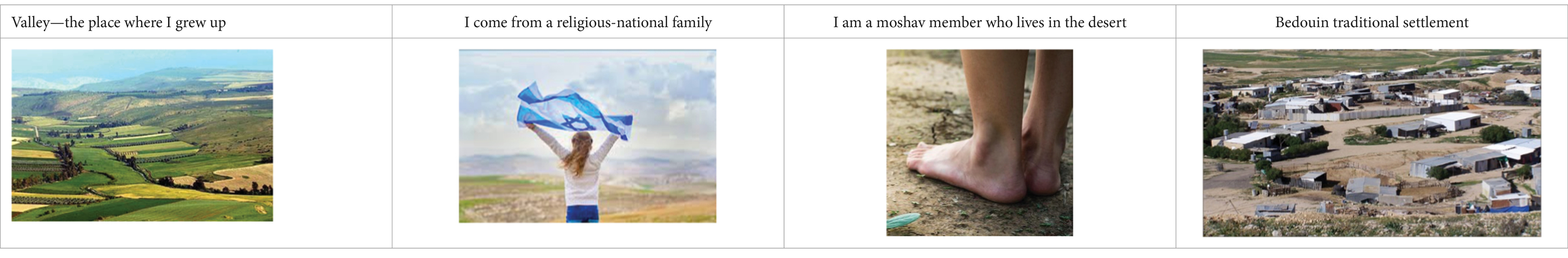

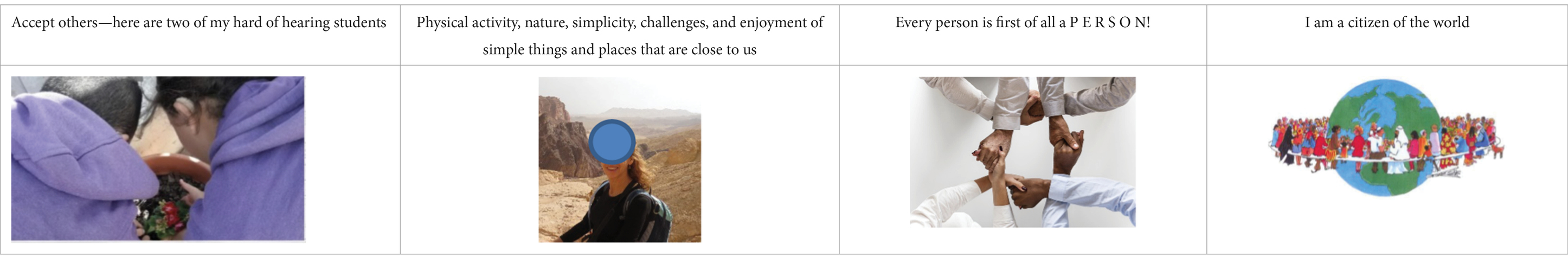

The pictures the participants shared in the collaborative presentation give us visual insight into the content. Table 2 shows pictures presenting the participants’ identities.

4.2 Values

Many participants referred to a variety of values as part of their culture, as shown in the following quotes:

Since I was a child, I have been taught the value of accepting the other as he is and respecting both the individual and others. (M, F, A)

I believe in coexistence and diversity in society and that each person is, first of all, a person! That’s how he should be treated, without prejudice and judgment. (H, F, J)

These quotes indicate that respect and inclusion of every person, regardless of their culture are prominent values.

The participants also mentioned values derived from religion and tradition:

We place a high emphasis on the love of Israel in our culture since every Chabad (Hassidic sect) invests nights and days for the sake of the public around the world, regardless of race, religion, or gender … I will do everything in my power to love, accept, and accommodate those who are different from me, even if their beliefs are contrary to how I live. (B, M, J)

The pictures in Table 3 demonstrate these values.

4.3 Family

The participants also wrote about the ways their families influenced the development of their culture, as shown by the following quotes:

Being the ninth child in a family of ten, I grew up in a very traditional Moroccan Jewish environment. My older brothers helped my parents with education, and I learned the importance of maintaining tradition. (N, F, J)

In my mother’s family, I am the first generation born in Israel after my grandparents immigrated from Germany shortly before the Holocaust … The family is one of the founders of Zichron Yaakov [a town in Israel]. (T, F, J)

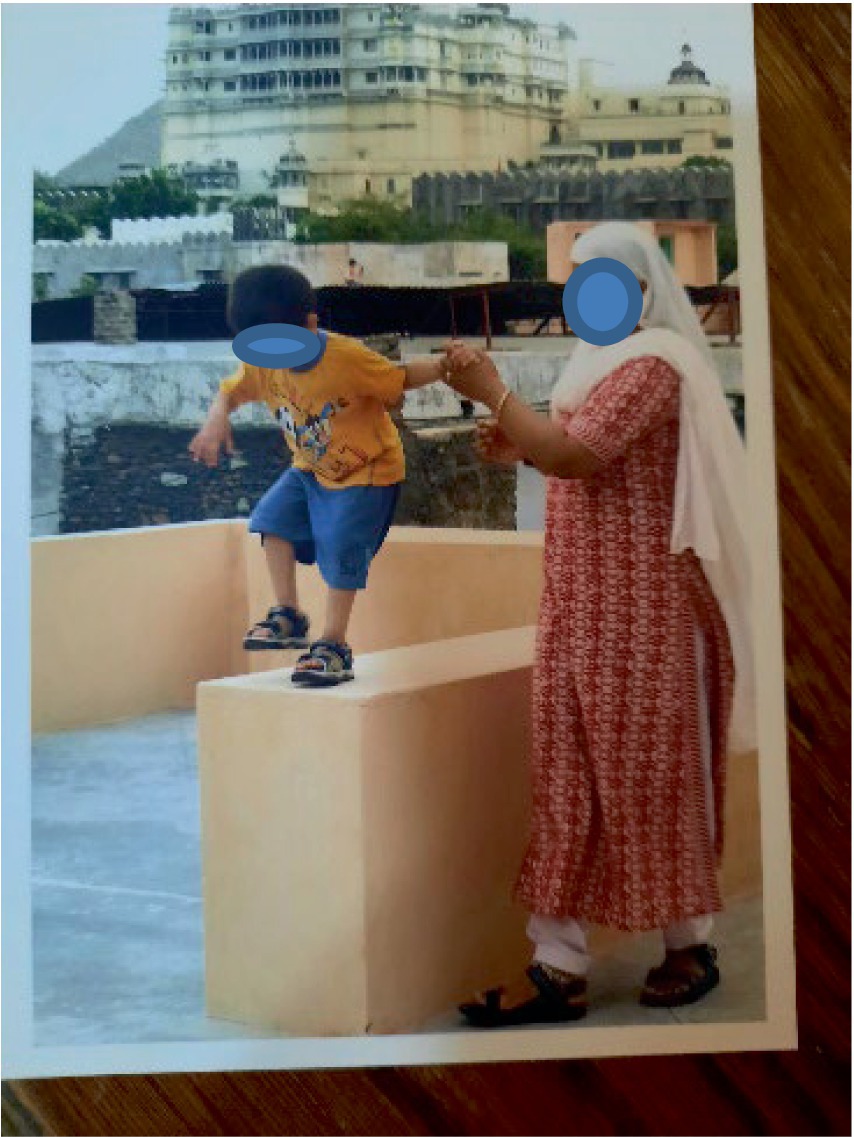

Some participants also shared pictures of their families (see Table 4).

4.4 Multiculturalism in the family

Some of the Jewish teachers described multiculturalism in their family, stemming from the Jewish immigration (aliya) to Israel:

My family is multicultural. My father is from Tunisia, my mother was born in Israel, but her mother is from Afghanistan and her father is from Poland, a Holocaust survivor who came to Tel Aviv with his uncle. I am married to a Persian. (H, F, J)

I come from an extended Jewish family: On one side, the ultra-Orthodox, and on the other side, the Shomer Hatzair (a secular youth movement). I educate my children in the spirit of love and acceptance I received from my parents and grandparents on all sides. (L, F, J)

One of the participants uploaded two pictures that precisely illustrate the meaning of Multiculturalism in the family. In Figure 4 the participant is visiting a Muslim village where her father was born. In Figure 5, she is praying in her parents’ Jewish home.

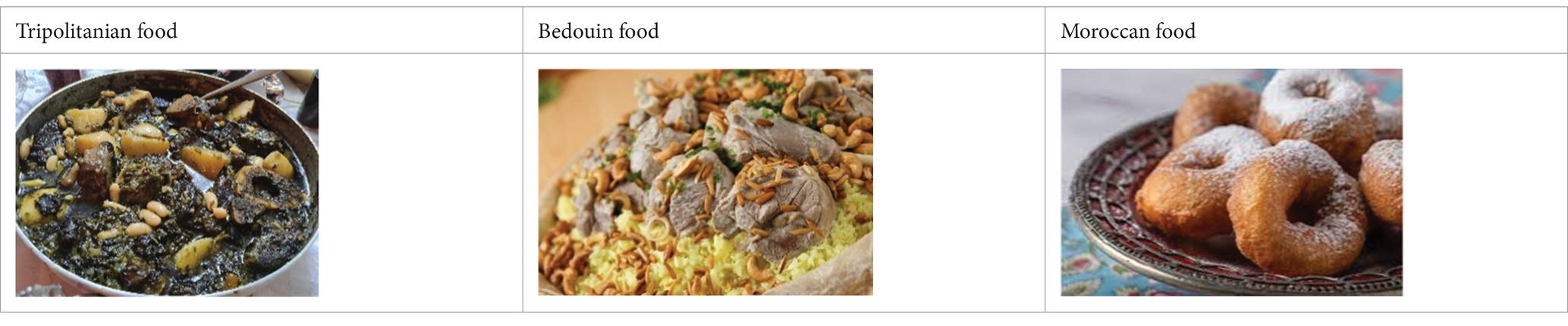

4.5 Food and the story behind it

The participants frequently referred to food as part of their culture, as can be seen in the following quotes:

Our family gatherings are around Iraqi food … my grandmothers share with us their personal stories. Today, I feel an obligation to continue cooking Iraqi food and telling my family story through it. (O, F, J)

Our family preserves our customs by preparing shared meals with delicious Iraqi foods… The foods are passed down from generation to generation, and all family members learn [how to cook] the foods to preserve the unique flavors they brought with them from Iraq. (L, F, J)

These quotes indicate that food enables the creation of connections between the past and the present. The participants uploaded many pictures of food, revealing the importance of food to their culture (see Table 5).

4.6 History

The participants refer to significant historical events, as shown in the following quotes:

I grew up in a very secular “Polish home.” My parents are second-generation Holocaust survivors, so food was and still is a big deal. (Y, F, J)

My parents made aliya from Ethiopia in Operation Moshe. (S, F, J).

4.7 Language

Some quotes referred to participants’ languages:

The Yemeni language sounds a bit like Arabic, but its uniqueness is in the music and the prayer hymns. (A, F, J)

Persian culture stands out mainly when I’m at my parents’ house, among other things, through the language. (D, F, J)

Some of my friends and family who grew up in Iraqi homes like to speak Iraqi. (O, H, J)

It should be noted that the participants rarely mentioned their home language, maybe because Hebrew is the official language in Israel.

RQ3: What characterizes the connection among the teachers during the TPD program?

To address this research question, we also employed content analysis. We looked specifically at people’s responses to others’ posts to answer this research question. One main theme emerged from the data analysis: Looking for similarity. This had five sub-themes: We come from the same culture, we share similar characteristics, we are connected, we are all human, and solidarity (see Figure 2).

4.8 We come from the same culture

My culture is very similar to yours. I really like Tel Aviv, I am also gay, and I also believe in social equality and diversity. (T, M, J)

B responded to H in their language, Arabic and not Hebrew, the TPD program language:

Hello sister Hadeel. I agree with you that women in Arab society have many responsibilities, and everyone depends on them. Our society is patriarchal, and change may take time.

4.9 We share similar characteristics

My family celebrates all Jewish holidays, including Novy God (A Soviet holiday celebrated on New Year’s Day), and I am very attached to the values you grew up with. (V, F, J)

Yemeni culture is very similar to Arab culture. I really like Yemeni food. Rosh Ha’Ain [a Jewish town] is very close to us, and I go there, and many Yemenis come to us, to Kfar Qasem [Arab town]. (B, M, A)

Tripolitanian culture is very similar to Tunisian culture, where I came from. During Passover, we also lift a Passover bowl over our heads. (A, F, J)

4.10 We are connected

Nature and simplicity are very important to me, as they are to you. (A, F, J)

I am connected to the values you mentioned—humanity first. I wish we knew how to be patient and tolerant toward each other. (A, F, J)

4.11 We are all human

My “religion” is science, and my “culture” is absolute freedom from the bars of cultural definitions. (Sh, M, J)

I could say about myself that I am a woman, Ashkenazi, Jewish, and secular, but it seems to me that first and foremost I try to be a person and try to accept everyone who is like me, and those who are different from me. (I, F, J)

4.12 Identification

With all my heart, I agree with your statement about every individual’s right to choose what is best for them. (Y, F, J)

I felt so connected to what you wrote! I grew up in a traditional home, but as I grew older, I moved from the religious side, but always kept the tradition of holidays and customs and really enjoy them. (H, F, J)

4.13 Learning about other cultures

The content analysis also reveals the willingness of the participants to learn about different cultures, as presented in the following quotes:

I enjoy learning about the uniqueness of different denominations. It is so interesting and enriches me culturally! (E, F, J)

We need to learn about Arab culture and learn Arabic as a second language in order to live in peace and harmony in our country. (M, F, J)

The Muslim culture interests me a lot. (R, F, J)

Getting to know another culture was a pleasure for me, and you made me search and read more about it. (L, F, A)

Most of the quotes indicate that participants wanted to know more about other cultures.

It is interesting to note that the Jewish participants expressed their wishes to learn Arabic and know more about Muslim culture. This may be because students do not learn enough Arabic or learn about Arabic culture and history in the formal Jewish education system. Arab formal education, on the other hand, teaches Jewish history, culture, and Hebrew. However, one Arab participant referred to her want for deeper familiarity with a specific sector within Jewish culture.

4.14 Asking questions

Asking questions was not part of the task. However, we can carefully argue that the questions imply participants’ curiosity and desire to receive more information on a variety of topics

I love how music connects us and makes us feel good. Do you understand the language? Do you understand what was said or did you enjoy the music itself? (M, F, J)

Your writing made me curious about you and raised many questions, including what you teach and to what age group. (L, F, J)

What makes you like one culture more than another? (Z, F, J)

Which differences and similarities do you see between the two families and cultures? (O, F, J)

4.15 Feelings and emotions

The teachers expressed positive feelings toward each other such as sympathy, appreciation, enjoyment, and excitement.

My sympathies go out to you, and I pray the violence in Arab society can be resolved. It cannot be tolerated, and my prayers are already being sent your way. (P, M, J)

I admire you for having the courage to move to the other side of the country and choose to build your home there! (M, F, J)

I enjoyed reading what you wrote, and I really appreciate how education accepts differences. (K, F, J)

I was excited by what you wrote. It is my wish, as educators and citizens, that this sentence will always be a light to guide us. (S, F, J)

5 Discussion

In this study, we examined a task given to teachers as part of a TPD program to support teachers who wish to promote a shared society in Israel. Indeed, teachers from various groups in Israeli society enrolled in the TPD program and got to know each other in depth through interactive activities that encouraged acquaintance and discussion. This study examines teachers’ processes throughout the TPD program and an interactive activity where teachers shared their core cultural components with teachers from other cultures.

The first research question dealt with the changes in teachers’ attitudes regarding multiculturalism before and after the TPD program. We found that the teachers who signed up for the TPD program had positive attitudes toward multiculturalism to begin with. Therefore, their attitudes were not significantly changed after the TPD program. Considering the complex situation and the lack of opportunities to meet different groups in Israeli society and the education system in Israel (Abu-Saad, 2004; Agbaria, 2018; Sabbagh and Resh, 2014), the online TPD program allowed the teachers to create social connections and meet other teachers they would not usually encounter or get to know. These meetings and connections occurred despite Israeli society’s current tensions and social rifts. However, given that the teachers had positive attitudes toward multiculturalism even before the TPD rogram, their attitudes on this point did not change following the process they underwent.

Following the second research question regarding the cultural characteristics evident in the interactive activity during the TPD program, we found that the teachers shared their core cultural components. For example, mostly identity and values, but also family, food and the story behind it, history, and language, which were all reflected in the pictures they chose and the text they wrote. Additionally, in pictures that present visible artifacts (Sever, 2016), they added the stories behind them or how they interpret them (Banks and Banks, 2019). In other words, the interactive activity encouraged them to look at other teachers’ core cultural components. This point is significant because people usually notice only the peripheral components of a person from another culture (Sever, 2016). Indeed, multicultural societies should wish to learn about and accept diverse core cultural values (Sever, 2016; Spencer-Oatey, 2012). The current research demonstrates how learning about core cultural values through an online TPD program and an interactive activity that fosters meaningful intercultural meetings among teachers from various groups is possible.

Following the third research question about the connection characteristics among the teachers during the TPD program, we found, through an inductive analysis, another interesting point. The teachers looked for similar characteristics and commonalities and mostly mentioned their similarities. At the same time, they tried to avoid controversial issues, mentioning that everyone is connected as human beings. Indeed, teachers in diverse societies look for commonalities when they meet each other and try to avoid conflicts, especially in divided societies (Shapira et al., 2021). A study conducted in Israel found that consensus-seeking among participants from diverse ethnic groups is driven by intense emotions, which can either lead to favorable agreement and shared feelings but with a lack of challenging discussions or, on the flip side, discomfort, avoidance, negative feelings, and a lack of regulation, resulting in frustration and reduced participation (Firer et al., 2021). In other words, dialog in a divided society is intricate and multifaceted. Sharing core cultural components might be the first phase of such dialog.

Despite the social-cultural rifts (Sabbagh and Resh, 2014) and the division in Israel’s public education system (Abu-Saad, 2019; Agbaria, 2018), the teachers expressed positive emotions and identification with each other. The teachers also started a discussion by asking questions without being instructed. Therefore, it is possible to improve intercultural relations and celebrate diversity and societal multiculturalism through online contact (Shapira et al., 2021; Dovidio et al., 2011; Pettigrew et al., 2011; Vezzali et al., 2014). In our study, teachers did not only share their core cultural components, but they were also positive and curious about each other. They expressed positive emotion and identification, asked questions, and received answers from teachers they did not have a chance to meet every day.

Such an experience is even more crucial for teachers who wish to educate for a shared society. Indeed, teachers should develop their skills and undergo personal development—teachers as learners—before cultivating different skills in the classroom (Shapira, 2016; Jennings and Greenberg, 2009; Osher et al., 2016). The present study demonstrates how teachers can experiment with getting to know teachers from different groups. Moreover, such meetings can be a model for teachers who wish to bring their students together with students from other cultures.

5.1 Limitations and suggestions for future research

The teachers attending the TPD program were those who wanted to participate in a program called “Educators for Shared lives.” Indeed, their attitudes toward multiculturalism were initially positive. Therefore, we recommend conducting a similar study among teachers who do not choose to participate in such a TPD program.

It is important to note that the TPD program had additional parts, such as getting to know each other through cards and planning a lesson for their students. Although we examined the effect of the TPD program as a whole, we also recommend investigating other parts. Furthermore, we recommend conducting a similar study in other countries to learn about such processes in different contexts.

5.2 Implications of the study

The current research demonstrates that fostering intergroup relations and encouraging meaningful acquaintance between cultures is possible, even in a diverse and often confrontational society such as Israel. Furthermore, it demonstrates that intergroup relations can be enhanced through online interactions. A facilitator interested in promoting meaningful acquaintance between different cultures can explain the core and peripheral cultural components to the participants and encourage the meeting using an interactive tool that allows the sharing of images presenting and explaining the participants’ cultures. Additionally, facilitators can stimulate discussions centered on the commonalities between different cultures, thereby fostering a deeper understanding and appreciation among participants.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Kinneret Ethics Committee—Ethics/40/2022. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

NS: Writing – original draft. MA: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The content of this manuscript, “How can Multiculturalism be Celebrated Through Teacher Training?” has been presented in ECER 2023 at the University of Glasgow, Scotland. “The Value of Diversity in Education and Educational Research.”

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1333697/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

2. ^The sample size necessary for paired sample t-tests, according to G Power, is 34 to detect a medium effect size (0.5) with a power of 0.80. Our sample size is 68.

3. ^The letter A indicate Arab participant, the letter J Jewish participant. The letter F indicate female, and the letter M indicate male.

References

Abu-Saad, I. (2004). Separate and unequal: the role of the state educational system in maintaining the subordination of Israel’s Palestinian Arab citizens. Soc. Identities 10, 101–127. doi: 10.1080/1350463042000191010

Abu-Saad, I. (2019). Palestinian education in the Israeli settler state: divide, rule and control. Settler Colonial Stu. 9, 96–116. doi: 10.1080/2201473X.2018.1487125

Agbaria, A. K. (2018). The “right” education in Israel: segregation, religious ethnonationalism, and depoliticized professionalism. Critical Stu. Educ. 59, 18–34. doi: 10.1080/17508487.2016.1185642

Aylward, T., and Mitten, D. (2022). Celebrating diversity and inclusion in the outdoors. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 25, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s42322-022-00104-2

Baldwin, J. R., Faulkner, S. L., Hecht, M. L., and Lindsley, S. L. (2006). Redefining culture: perspectives across the disciplines. London: Routledge.

Banks, J. A., and Banks, C. A. M. (2019). Multicultural education: issues and perspectives. 7th Edn. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Bennett, M. J. (2017). Developmental model of intercultural sensitivity. Int. Encyclopedia Interc. Commun. 1, 1–10. doi: 10.1002/9781118783665.ieicc0182

Bingham, A. J. (2023). From data management to actionable findings: a five-phase process of qualitative data analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods. 22, 1–11. doi: 10.1177/16094069231183620

Borko, H. (2004). Professional development and teacher learning. Zeist: Woudschoten Conference Center, 3–15.

Cusher, K., and Mahon, J. (2009). Intercultural competence in teacher education. Cham: Springer, 185–213.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute, 1–2.

DeJaeghere, J. G., and Zhang, Y. (2008). Development of intercultural competence among US American teachers: professional development factors that enhance competence. Intercult. Educ. 19, 255–268. doi: 10.1080/14675980802078624

Dhiman, S., Modi, S., and Kumar, V. (2019). Celebrating diversity through spirituality in the workplace: transforming organizations holistically. J. Values Based Leadership 12:6. doi: 10.22543/0733.121.1256

Dovidio, J. F., Eller, A., and Hewstone, M. (2011). Improving intergroup relations through direct, extended and other forms of indirect contact. Group Proc. Intergroup Relations 14, 147–160. doi: 10.1177/1368430210390555

Dusi, P., Rodorigo, M., and Aristo, P. A. (2017). Teaching in our society: primary teachers and intercultural competencies. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 237, 96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2017.02.045

Fincher, R., Iveson, K., Leitner, H., and Preston, V. (2014). Planning in the multicultural city: celebrating diversity or reinforcing difference? Prog. Plann. 92, 1–55. doi: 10.1016/j.progress.2013.04.001

Firer, E., Slakmon, B., Dishon, G., and Schwarz, B. B. (2021). Quality of dialogue and emotion regulation in contentious discussions in higher education. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 30:100535. doi: 10.1016/j.lcsi.2021.100535

Ghazaie, M., Rafieian, M., and Dadashpoor, H. (2021). Celebrating diversity: a framework for urban discourses. Local Dev. Soc. 2, 41–60. doi: 10.1080/26883597.2021.1883993

Hidalgo, N. M. (2013). Multicultural teacher introspection. Freedom’s Plow Teach. Multicultural Classroom 18, 99–106. doi: 10.4324/9781315021454-6

Holladay, C. L., Knight, J. L., Paige, D. L., and Quiñones, M. A. (2003). The influence of framing on attitudes toward diversity training. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 14, 245–263. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.1065

Hymel, S., and Katz, J. (2019). Designing classrooms for diversity: fostering social inclusion. Educ. Psychol. 54, 331–339. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2019.1652098

Jahoda, G. (2012). Critical reflections on some recent definitions of "culture.". Cult. Psychol. 18, 289–303. doi: 10.1177/1354067X12446229

Jennings, P. A., and Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 79, 491–525. doi: 10.3102/0034654308325693

Jokikokko, K. (2005). Interculturally trained finnish teachers’ conceptions of diversity and intercultural competence. Intercult. Educ. 16, 69–83. doi: 10.1080/14636310500061898

Kinnvall, C., and Lindén, J. (2010). Dialogical selves between security and insecurity: migration, multiculturalism, and the challenge of the global. Theory Psychol. 20, 595–619. doi: 10.1177/0959354309360077

Kymlicka, W. (2015). The three lives of multiculturalism: Theories, policies and debates. Revisiting multiculturalism in Canada. Leiden: Brill Publishers.

Leszczensky, L., and Pink, S. (2019). What drives ethnic Homophily? A relational approach on how ethnic identification moderates preferences for same-ethnic friends. Am. Sociol. Rev. 84, 394–419. doi: 10.1177/0003122419846849

Lumpkin, A. (2008). Teachers as role models teaching character and moral virtues. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 79, 45–50. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2008.10598134

Maruyama, G., Moreno, J. F., Gudeman, R. H., and Marin, P. (2000). Does diversity make a difference? Three research studies on diversity in college classrooms. Washington, DC: American Council on Education and American Association of University Professors.

Natividad Beltrán del Río, G. (2021). A useful framework for teacher professional development for online and blended learning to use as guidance in times of crisis. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 69, 7–9. doi: 10.1007/s11423-021-09953-y

Osher, D., Kidron, Y., Brackett, M., Dymnicki, A., Jones, S., and Weissberg, R. P. (2016). Advancing the science and practice of social and emotional learning: looking back and moving forward. Rev. Res. Educ. 40, 644–681. doi: 10.3102/0091732X16673595

Parkhouse, H., Lu, C. Y., and Massaro, V. R. (2019). Multicultural education professional development: a review of the literature. Rev. Educ. Res. 89, 416–458. doi: 10.3102/0034654319840359

Pettigrew, T. F., Tropp, L. R., Wagner, U., and Christ, O. (2011). International journal of intercultural relations recent advances in intergroup contact theory. Int. J. Intercultural Relat. 35, 271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.03.001

Pizmony-Levy, O., and Kosciw, J. G. (2016). School climate and the experience of LGBT students: a comparison of the United States and Israel. J. LGBT Youth 13, 46–66. doi: 10.1080/19361653.2015.1108258

Pohan, C. A., and Aguilar, T. E. (2001). Measuring Educators' beliefs about diversity scale in personal and professional contexts. Am. Educ. Res. J. 38, 159–182. doi: 10.3102/00028312038001159

Rew, L., Becker, H., Cookston, J., Khosropour, S., and Martinez, S. (2003). Measuring cultural awareness in nursing students. J. Nurs. Educ. 42, 249–257. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20030601-07

Sabbagh, C., and Resh, N. (2014). Citizenship orientations in a divided society: a comparison of three groups of Israeli junior-high students-secular Jews, religious Jews, and Israeli Arabs. Educ. Citizenship Soc. Justice 9, 34–54. doi: 10.1177/1746197913497662

Sever, R. (2016). Preparing for a future of diversity - a conceptual framework for planning and evaluating multicultural educational colleges. Rev. Educ. Res. 10, 23–49. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Rita-Sever/publication/305245696

Shapira, N. (2016). Design principles for promoting intergroup empathy in online environments. 12, 25–246.

Shapira, N., and Amzalag, M. (2021). Online joint professional development: a novel approach to multicultural education, Journal for Multicultural Education, 15, 445–458. doi: 10.1108/JME-07-2021-0109

Shapira, N., and Mola, S. (2022). Teachers “looking into a mirror” - a journey through exposure to diverse perspectives. Intercult. Educ. Routledge, 33, 611–629. doi: 10.1080/14675986.2022.2143694

Shapira, N., et al. (2021). Utilizing television sitcom to foster intergroup empathy among israeli teachers. Int. J. Multicult. Educ. 22, 1–23. doi: 10.18251/IJME.V22I3.2225

Simonsen, K. B., and Bonikowski, B. (2020). Is civic nationalism necessarily inclusive? Conceptions of nationhood and anti-Muslim attitudes in Europe. Eur J Polit Res 59, 114–136. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12337

Spencer-Oatey, H. (2012). What is culture? A compilation of quotation. London: GlobalPAD Open House, 2.

Suleiman, R., Yahya, R., Decety, J., and Shamay-Tsoory, S. (2018). The impact of implicitly and explicitly primed ingroup – outgroup categorization on the evaluation of others pain: the case of the Jewish–Arab conflict. Motiv. Emot. 42, 438–445. doi: 10.1007/s11031-018-9677-3

van de Weerd, P. (2020). Categorization in the classroom: a comparison of teachers’ and students’ use of ethnic categories. J. Multicultural Disc. 15, 354–369. doi: 10.1080/17447143.2020.1780243

Vezzali, L., Hewstone, M., Capozza, D., Giovannini, D., and Wölfer, R. (2014). Improving intergroup relations with extended and vicarious forms of indirect contact. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 25, 314–389. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2014.982948

Villegas, A. M., Strom, K., and Lucas, T. (2012). Closing the racial/ethnic gap between students of color and their teachers: an elusive goal. Equity Excell. Educ. 45, 283–301. doi: 10.1080/10665684.2012.656541

Keywords: diverse society, multiculturalism, online interaction, intercultural relations, multicultural education

Citation: Shapira N and Amzalag M (2024) How can multiculturalism be celebrated through teacher training in Israel? Front. Educ. 9:1333697. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1333697

Edited by:

Cheryl J. Craig, Texas A&M University, United StatesReviewed by:

Sina Westa, University for Continuing Education Krems, AustriaJulia Mori, University of Bern, Switzerland

Copyright © 2024 Shapira and Amzalag. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Noa Shapira, U2hhcGlyYS5ub2FAbXgua2lubmVyZXQuYWMuaWw=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Noa Shapira

Noa Shapira Meital Amzalag

Meital Amzalag