- 1Education Science Department, Université du Québec à Rimouski, Rimouski, QC, Canada

- 2Faculty of Education, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, QC, Canada

This article examines supervisory practices in vocational education and training teaching internships within a blended-learning system. Using a multiple-case study of five triads made up of a university supervisor, a cooperative teacher from the workplace and a student teacher, practices were analysed through the lens of supervisory functions: support, mediation between theory and practice, collaboration, evaluation and internship management. Findings show that support and evaluation practices are dominant within triads. The management function is characterized by practices surrounding the selection and use of digital tools to supervise student teachers in a blended-learning system. The collaboration function appears to be inconsistent from one triad to another, while the mediation between theory and practice function plays a limited role in the practices of all supervisors, despite being identified as one of their main responsibilities.

1 Introduction

In the Canadian province of Quebec, practical teacher training is considered crucial to the development of professional skills (Gouvernement du Québec, 2020) and is conducted in close collaboration with practice settings while remaining the university’s responsibility. Universities that offer a bachelor’s degree in vocational education (BVE) have incorporated practical training into their curricula since the program’s launch in 2003. Vocational education and training (VET) teachers must complete a minimum of 700 h of practical training through internships in Vocational Training Centers (VTC) prior to graduation. However, in its 2008 orientation document, the Quebec education department concluded its description of internship guidelines for the various teacher training programs by stating that “certain aspects have yet to be defined, particularly in the case of vocational training education programs” [translation] (Gouvernement du Québec, 2008, p. 24). Indeed, as Gagnon (2013) reminds us, “an entire culture of supervising student teachers in the workplace still needs to be developed” [translation] (p. 113) in this area of instruction. While there is now greater awareness of issues pertaining to VET teacher training (Gagnon and Coulombe, 2016), the topic of teaching internship in this area has received less attention.1

The research presented in this article aims to answer the following question: What are the practices of university supervisors for VET teaching internships in a blended-learning system? To answer this question, the problem statement is presented to contextualize the issues relating to teaching internship supervision in general before presenting the specific challenges of initial VET teacher training and supervision in a blended-learning system. In the third section of the article, the conceptual framework defines what is meant by teaching internship supervision and the concepts of practices and blended-learning system. This section closes with the presentation of an analysis grid of practices categorized into five supervision functions. The fourth section details the interpretive methodology using a multiple-case study. The five-triad makeup of the sample and the data collection methods chosen to document the cognitive and behavioral dimensions of the practices are presented. To close this section, the qualitative data analysis approach presenting the case studies is outlined. The fifth section discusses the findings and is divided into five subsections that present the use practices, grouped by supervisory function within the five triads. For each case, a figure presenting the articulation of the supervisory functions is included. These figures illustrate the commonalities and variations between the cases.

The article concludes with a discussion based on the findings. The discussion highlights the specificities of VET teaching internship supervision within a blended-learning system and is grouped into three themes that were revealed in the findings. The first theme addresses the commonalities in cases within a blended-learning system. The second theme discusses the impact of the supervisory context on supervisors’ functions, especially the collaboration function. Lastly, the mediation function, which seems to be marginalized or minimally present in the practices of all triads, is addressed and discussed through the lens of support for student teachers’ reflective process. The article’s conclusion presents the limitations of the research, along with upcoming research that will continue to expand knowledge of supervision of vocational training internships and other training fields.

2 Problem statement

Pre-service teachers who complete internships prepare for their professional reality by immersing themselves in the concrete conditions of the job (Paulsen and Schmidt-Crawford, 2017). Triads, made up of a university supervisor (US), a cooperative teacher (CT) who is active in the practice setting and a student teacher, are a common supervision system for teaching internships, both in Quebec and abroad (Allen et al., 2014; Campbell and Lott, 2010; Denis, 2017; Labeeu et al., 2018; Portelance et al., 2016; Veuthey, 2018). For VET teaching internship, the partnership between the practice setting and the university also falls under the triad model; however, there is a key difference in terms of its members’ traditional roles. Because VET teachers are hired for their expertise in a trade they have learned and practice (plumbing, computer graphics, cooking, etc.), many of them teach for one to several years prior to pursuing teacher training (Balleux, 2011). A minority of VET teachers prepare to begin teaching professionally by enrolling in the mandatory teaching bachelor’s program before securing a teaching contract (Tardif and Deschenaux, 2014).

As a result, most VET teaching internships are done on the job, with student teachers who are professionally autonomous and who hold temporary teaching certificates issued by Quebec’s education department. Consequently, cooperative and student teachers occupy “equal” positions (Gouvernement du Québec, 2008); they may even have an equivalent amount of experience and are frequently colleagues with full-time teaching positions. Understandably, this situation creates unprecedented organizational (Coulombe and Gaudreault, 2008; Gagnon, 2013), pedagogical (Gagné and Gagnon, 2022), and relational challenges during initial teacher training done on the job (Gagnon and Mazalon, 2016). Moreover, in research specifically focusing on the characteristics and role of VET cooperative teachers, Gagné and Gagnon (2022) conclude that “performing all duties that require them to challenge ideas, take critical stances or analyze practices remains perilous for cooperative teachers” [translation] (p. 246). Considering these findings, we2 believe that the contribution of the university supervisor within the triad must be given greater focus in the context of VET teaching internships.

After a literature review, it is still difficult to assess the significance of the university supervisor’s role in the VET teaching internship triad. In the United States, there is a tradition of research about the university supervisor. Supervision models such as clinical supervision (Acheson and Gall, 1987; Cogan, 1972; Goldhammer, 1980), developmental supervision (Burns, 2012; Burns and Badiali, 2016; Glickman et al., 2014), or differentiated supervision (Glatthorn, 1984) offer guidelines and preferred steps, phases, or cycles, including direct observations of student teachers during their internships. While they are useful for understanding the context in which supervision occurs, referencing supervision models has limitations when it comes to describing the practices of supervisors. Moreover, models do not fully define the functions occupied by the university supervisor within training systems or the actions they operationalized to supervise. The statement of steps or phases does not inform how the university supervisor acts during these phases nor the decisions made before, during, and after the interactions between the student teacher, de cooperative teacher, and the university supervisor (Zeichner and Tabachnick, 1982).

While studies conclude that the university supervisor’s contribution to the student teachers’ training is indisputable (Bates et al., 2011), their practices appear to be underestimated (Burns et al., 2016) and undertheorized (Cuenca, 2010). The presence of research supported by a self-study approach by one or more supervisors highlighting the need to deepen their practices is notable. Indeed, a variety of articles stemming from self-study, supported by the analysis of field notes, reflective journals, exchanged emails, and reports of conversations or open exchanges between colleagues gathered by one or several supervisors who are also researchers exist (Bullock, 2012; Butler and Diacopoulos, 2016; Butler et al., 2023; Cuenca, 2010; Dangel and Tanguay, 2014; Donovan and Cannon, 2018; McDonough, 2014, 2015; Schneider and Parker, 2013). These studies expose a similar issue, emphasizing the improvisation that novice supervisors must demonstrate in response to expectations while receiving minimal or no training (Bullock, 2012; Cuenca, 2010; McDonough, 2014). In fact, university supervisors left to themselves tend to reproduce what they have encountered and to use a default approach supported by their background or previous models, even if these are not necessarily relevant (Burns and Badiali, 2015; Butler and Diacopoulos, 2016; Cuenca, 2010).

In Quebec, few researchers make supervisors a key component of their research, preferring to concentrate on the student teachers. Also, the work of the university supervisor is mostly approached from the perspective of collaboration with the cooperative teacher (Portelance et al., 2016; Portelance and Caron, 2021) rather than focusing on their practices. Besides, when seeking to learn more about academic supervision in VET teaching internships or similar contexts, there is an almost complete lack of knowledge on the subject. This is a problem, as there is little theoretical basis to define the practices of university supervisors and to frame their functions with VET student teachers.

The research presented in this article seeks to document university supervisor practices within the specific context of a remote BEV. Internships for this university program, which are offered both through blended learning and remotely, require the use of a wide range of digital technologies for supervision. Studies by Hamel (2012) and Pellerin (2010) have already demonstrated that it is possible to effectively supervise internships for student teachers based far from the university remotely. A literature review on remote supervision in various post-secondary fields (Petit et al., 2019) reveals that although data on remote internship supervision does exist, it primarily focuses on the digital tools used in the systems and on perceptions rather than on trainers’ actual practices. However, it is now known that using digital technology for remote supervision requires university supervisors to modify their practices and tends to change the way the triad works together (Petit, 2018). Furthermore, the limited knowledge of the practices of university supervisors in the context of VET, underscores the importance of further documenting the remote supervision context in this training sector.

The overall aim of this research is thus to present an overview of supervisory practices used in VET teaching internships in a blended-learning system. This article presents a portion of the findings about the functions performed by the university supervisors from five triads during a university term. More specifically, we examine how each university supervisor articulates the five supervisory functions: support, mediation between theory and practice, collaboration, evaluation and internship management (Dionne et al., 2021).

3 Conceptual framework

The conceptual framework addresses elements that help create a portrait of practices associated with teaching internship supervision. Through the concept of a blended-learning system, the university supervisors’ actions are situated in the specific context of a BVE program that offers this type of internship, which relies on the use of digital technology. Next, we present a framework for analyzing supervisory practices. This is illustrated in a diagram, the form of which is used to present the findings in each case. First, however, we must define what is meant by supervisory practices in the context of teaching internships.

3.1 Teaching internship supervision

Teaching internship supervision is a specialized field within the broader field of teacher supervision that specifically falls under the responsibility of the university (Lawless, 2016). Although it is sometimes tinged with negative perceptions about the notion of being supervised by an outsider and despite confusion about the distinction between evaluation and supervision (Maes et al., 2018), the fact remains that internship supervision is associated with the teacher training field (Boutet, 2002). For the purposes of this study, teaching internship supervision is defined as a series of functions performed on an ongoing basis by a person designated to support the student teachers’ learning in an internship context (Burns et al., 2016).

We chose to approach internship supervision from the perspective of practices consisting of “acts and procedures that are particularly observable because they are recurrent, whose effectiveness has been proven by a subject or group of subjects, and that have been institutionalized during their experience” [translation] (Trinquier, 2014, p. 222). For Van Manen (1999), to speak of practices is to discuss “preferred ways of acting, tacit knowledge, habituated actions, patterned presuppositions, critical presumptions, knowledge, traditions, and so forth” (p. 65). We can thus refer to supervisory practices, because they require professional conduct from the university supervisors that is reflected in their ways of acting (Altet, 2000) as they perform their duties. There is therefore no single unified practice for supervision, as is the case for teaching, nor is one single method applied (Bru, 2002).

3.2 Studying practices in a blended-learning context

The supervisors’ practices in this research are documented specifically in the context of a blended-learning supervision arrangement, i.e., a combination of remote activities conducted through digital means and traditional face-to-face instruction (Graham, 2013). We use Albero’s (2010) three-pronged approach as a framework for interpreting the system, exploring it from three angles: the ideal system, which establishes the principles, concepts and values that structure training; the functional reference system, which defines the content, the roles of the actors and the working documents; and the lived system, which represents how the system is applied by the people, both learners and trainers, using it.

Due to their responsibility for internship activities during the university term, the university supervisors are primarily linked to the lived aspect of the system. They necessarily have a subjective interpretation of the ideological and material framework that is presented to them when they perform their duties with the student teachers. Although the training system established to structure and identify modes of supervision is a closed one, given it is imposed by the university program (Jézégou, 2019), it is still embodied (Charlier et al., 2006) by the supervisors who operate at its core. When the people who use it feel a sense of ownership over it, they can modify it or steer it further from its objectives to meet their own needs or correct its failings (Albero, 2010). Training systems, like practice models, “provide blueprints to shape and guide action” [translation] (Bru, 2002, p. 68). However, despite serving as indicators or frameworks, systems cannot guarantee that practices are consistent or even harmonized. The way the system is applied, and thus the way it is experienced, vary from one person to another, and even for the same person over time (Lenoir, 2007).

3.3 A grid to analyze supervisory practices

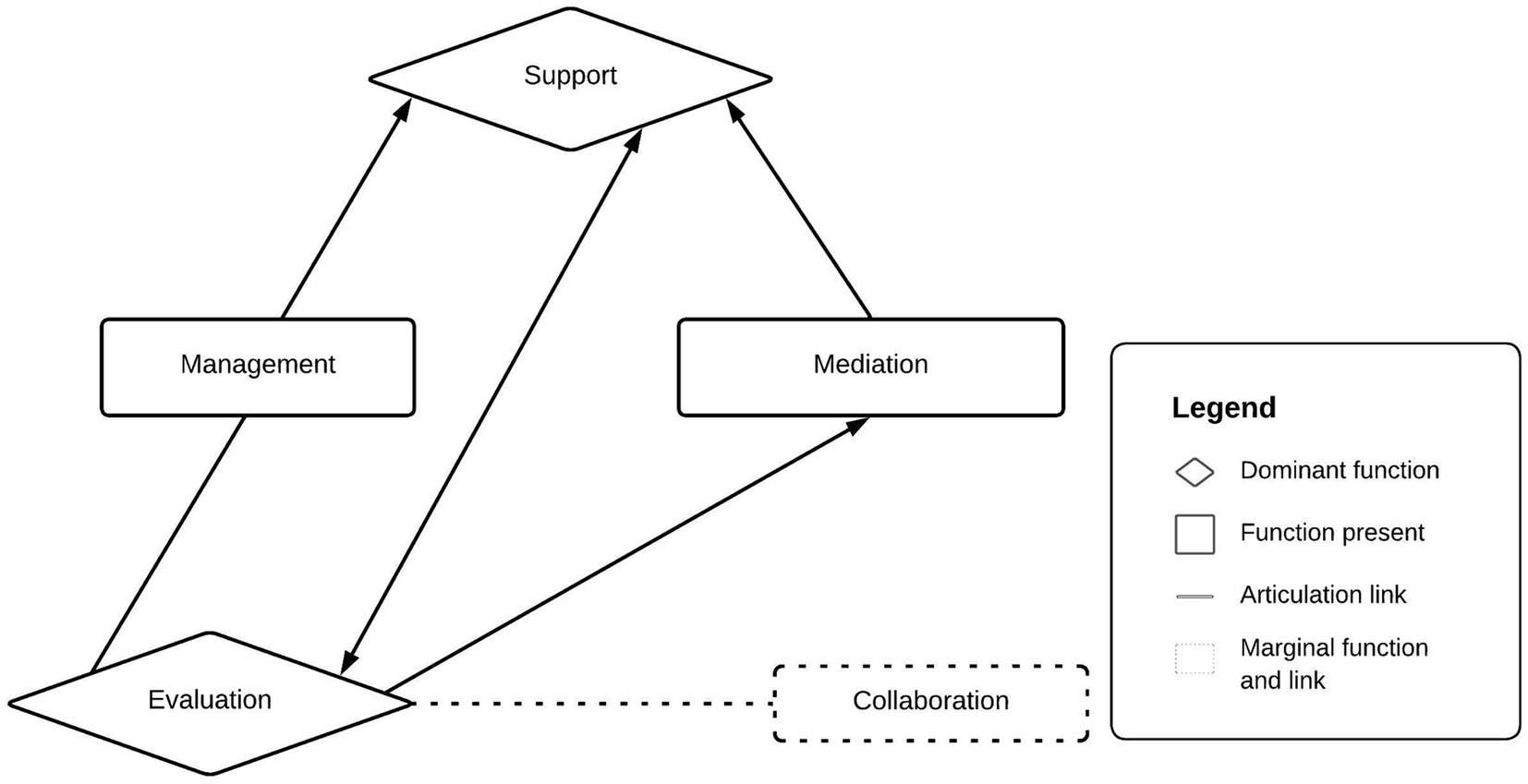

To document the university supervisor practices within this blended-learning internship supervision system, an analytical framework was developed using five frames of reference identifying functions (Villeneuve and Moreau, 2010), roles (Gervais and Desrosiers, 2005), skills (Portelance et al., 2008), activities (Cohen et al., 2013) and tasks (Burns et al., 2016). Though each of these frames of reference addresses supervision from its own angle, the fact remains that they all describe what the university supervisor does or should do to benefit the student teacher, ensure collaboration with the cooperative teacher and meet university requirements. Through a careful cross-sectional analysis of their content, recurrent and expected actions, procedures and behaviors were identified as supervisory practices. Upon completion of the analysis, these practices were grouped into five functions based on the definition of Burns et al. (2016), which defines supervision as a series of functions performed by the supervisor to support the student teachers’ training. These five functions are support, mediation between theory and practice, collaboration, evaluation and internship management (Dionne et al., 2021). Figure 1 presents these five functions and provides a short description of each one.

Figure 1. Supervisory functions [adapted from Dionne et al. (2021)].

The data collected was analyzed on the basis of these five functions. In Figure 1, we can see that each function is associated with a pole. Because supervision is tailored to a university teacher training program, the university supervisors’ practices involve student teachers and cooperative teachers in addition to meeting the guidelines of the training program.

4 Methodology

Van Manen (1999) emphasizes that practices are not directly accessible, observable or measurable at first glance. On one hand, there is the visible component, such as gestures, behaviors and speech; on the other hand, there is a cognitive component that involves “preparation, planning, and decision-making” [translation] (Altet, 2002, p. 85). For these reasons, supervisory practices are examined using a multiple-case study (Miles and Huberman, 2003) of an interpretative nature (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016), which necessitates close proximity to the participants. The case study requires the use of multimethodology, which makes it possible to document the wide range of supervisory practices. It also helps in the consideration of elements that are impossible to quantify (Roy, 2010) and too complex for investigation strategies or more experimental methods (Collerette, 2009). As set out in the research question, supervision of VET teaching internships supported by a blended-learning system is still a little-known phenomenon that requires further exploration in order to define its form and detail its practices. By creating descriptive portraits organized in a similar way for all case studies, we are using a case-oriented strategy (Miles and Huberman, 2003) that enables us to compare them and identify similarities and differences that guide the discussion of the findings.

The unit of analysis for each case was a triad comprised of a university supervisor, a cooperative teacher and a student teacher. Although there were three individuals in the unit of analysis and each one had consented to participate in the study, only the university supervisors were considered direct participants in data collection, which documented their practices within a specific triad. To join the study, university supervisors were required to have supervised at least one internship before and to be in a supervisory position at the time of the study. The university supervisors, who were recruited due to their supervisory roles at a Quebec university whose internships were supervised using a blended-learning system, were asked to identify the members of the triad. No selection criteria were applied to cooperative teachers. Student teachers who teach in a VET program using an individualized instructional approach, via distance education, or entirely in the workplace with their students, were excluded from the study. Similarly, student teachers who did not have a teaching assignment (Tardif and Deschenaux, 2014) during the study and who were required to take part in their cooperative teacher’s classroom were not selected. The choice of this non-probabilistic, intentional and convenient sample was intended to create typical triads that were both rich and representative of the usual VET teaching internship supervision context (Miles and Huberman, 2003; Pires, 1997).

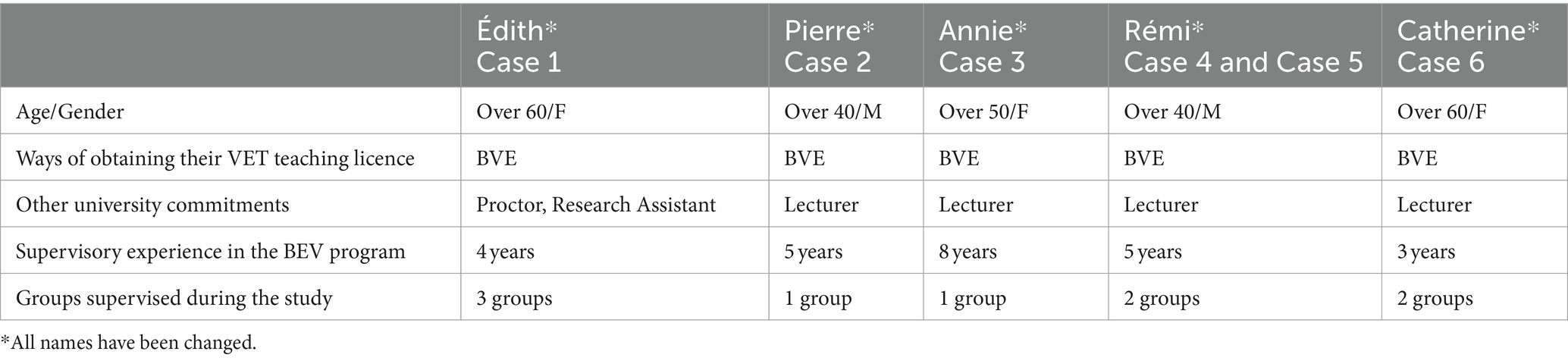

The initial goal was to recruit three triads, but five supervisors answered the call. One university supervisor offered to recruit two separate triads, one comprised of members who knew each other from previous supervision and another that included a university supervisor and a cooperative teacher whom the university supervisor was meeting for the first time. This university supervisor is therefore included in two cases. Table 1 presents the characteristics of participating university supervisors from each triad recruited.

These supervisors were lecturers. They were hired for a term according to the program’s needs. They could supervise between one and four groups of student teachers (about 10 student teachers per group). To be hired as a supervisor for this university’s BVE, the minimum qualification requirements were a BVE and 5 years of experience in VET teaching. Except for Rémi, all supervisors exceeded the basic training requirement by having a master’s degree specializing in the field of VET education. Two supervisors were retired VET teachers and pedagogical conselors (Catherine and Édith). Annie, Pierre, and Rémi were still VET teachers or pedagogical counselors. These candidates had not received any specific training to supervise internships. General instructions regarding clinical supervision modalities were provided to them for observations and the triad’s meetings. They also received evaluation documents including observation grids and expected levels of skill development for each internship. During the intership, supervisors conducted various formative assessments. At the end of the term, they had to carry out a summative assessment to certify the achievement of the internship objectives. One professor, who is a scholar of supervision and serves as VET internship supervisor, was available to answer questions, assist in problem-solving, clarify aspects of the system and provide guidelines. However, supervisors are responsible for their own professional development regarding supervision.

4.1 Data collection

The university supervisors’ practices were approached by seeking to understand their “behavioral and cognitive dimensions in a context-sensitive manner” [translation] (Deaudelin et al., 2005, p. 4). It was therefore necessary to examine declared practices (Deaudelin et al., 2005) and to “observe actual practices in order to define their components” [translation] (Grenon and Larose, 2009, p. 168). Consequently, two types of data were collected through multiple means to ensure triangulation of sources (Miles and Huberman, 2003). First, data documenting reported practices was collected as part of the study (Van der Maren, 2003). This was done through semi-structured interviews (Savoie-Zajc, 2010), video follow-up interviews (Tochon, 1996) and records kept by the university supervisors (Baribeau, 2005). Data collection also made it possible to gather invoked (or field) data, which exists independently of the study (Van der Maren, 2003) and testifies to actual practices. Data was collected through video recordings by the researcher in the natural contexts of supervision visits and dyad and triad meetings (Knoblauch et al., 2017) and through periodic observation (Martineau, 2005) of digital learning environments (DLEs), which were recorded using screen capture.

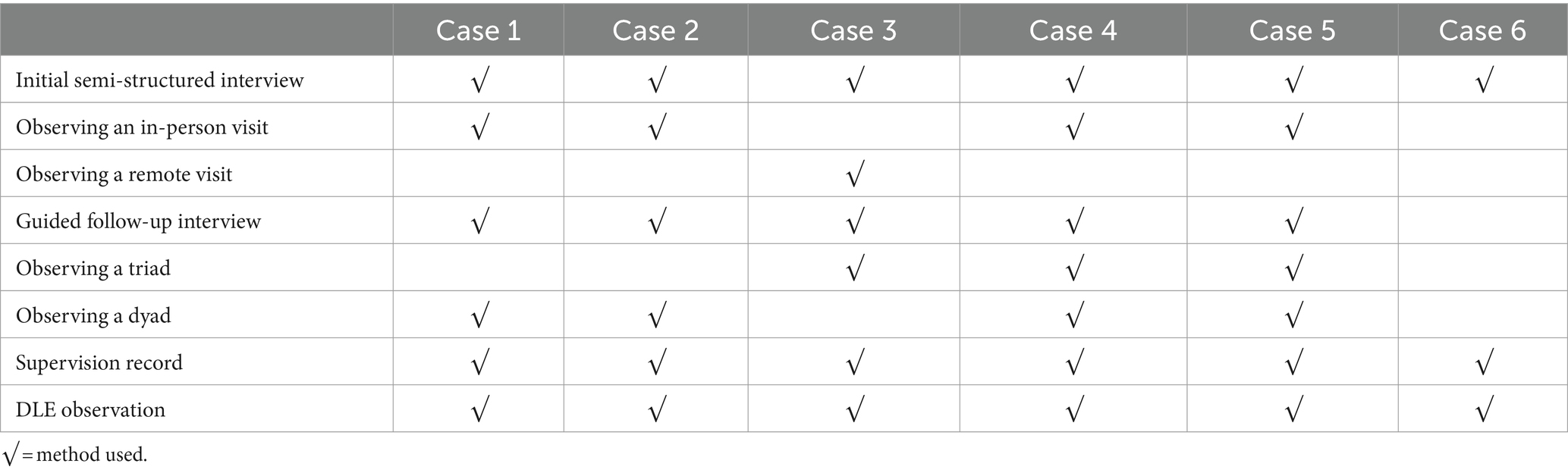

However, it should be noted that data collection that was intended to take place during the winter 2020 university term was abruptly halted due to the public health emergency measures implemented in response to the global COVID-19 pandemic in March. VTC visits and remote observation were canceled for all of the cases and the internships ultimately ended before all supervisory phases were completed. Table 2 illustrates which data collection methods were used (or not used) for each case.

Table 2 shows that there was only one documented case of a remote visit. The Case 3 university supervisor (Annie) had decided to begin the term using this method of observation, whereas the others had opted to begin with an in-person visit. The Case 6 university supervisor (Catherine) did not have time to conduct an in-person or remote supervisory visit before schools were closed. This meant that we were unable to gather video data, which limited our ability to document her actual practices. As a result, this case was excluded from the study. Finally, the fact that some university supervisors did not hold meetings as a dyad or triad during the recorded observations was their choice and unrelated to the pandemic.

Interviews were transcribed verbatim. Video recordings of in-person and remote visits were also transcribed verbatim whenever the university supervisor was speaking to a member of the triad. When there were no verbal interactions involving the university supervisor, their actions and gestures were briefly described (e.g., the US is moving closer to see the demonstration, the US is taking notes on their computer, the US is looking at the student teacher’s notebook, etc.). These transcriptions and descriptions taken from the videos were subsequently coded and analyzed.

4.2 Analytical approach

Data analysis was initially performed using NVivo12 software. Verbatim transcripts and video descriptions, university supervisor records and screen captures of the DLE were uploaded to the software for coding. Thematic analysis, which involves “systematically identifying, grouping and examining the discursive themes addressed in a corpus” [translation] (Paillé and Mucchielli, 2021, p. 270), was selected to process the data. The data was broken down into comparable units (Deslauriers, 1991) using two questions related to our research question: (1) What does the supervisor say they are doing in this excerpt? (2) What does the supervisor do in this excerpt?

An approach described by Bardin (2013) whereby the meaning of the coded extracts takes precedence over the form they take was adopted. Data was reviewed “line by line” (Miles and Huberman, 2003, p. 115), making it possible to compile a list of themes based on an action verb describing what the university supervisor does or says they are doing (e.g., sending their verdict to the university at the end of the internship, transferring the cooperative teacher comments to the final evaluation, etc.). Through coding, the themes were progressively ordered, paired and reformulated. During each stage of the data reduction and reflective process, a tracking grid was used to record changes and track the analysis process. Once the corpus was fully deconstructed, we were left with 253 themes classified into 16 thematic clusters and nine headings. Given that there is no “agreed-on data setups among qualitative researchers, so each analyst has to […] invent new ones” (Miles and Huberman, 2003, p. 175), we chose to produce descriptive profiles of each case. We examined the excerpts on a case-by-case basis to take a comprehensive look first at the themes, then at the thematic groupings, and finally at the full content of each heading. Once this was complete, an initial long profile of the practices of the university supervisors for each case was drafted. A second summary profile was subsequently written to highlight the emergence of links and discontinuities illustrating the articulation of the supervision functions. These shorter profiles are presented in this article.

5 Results

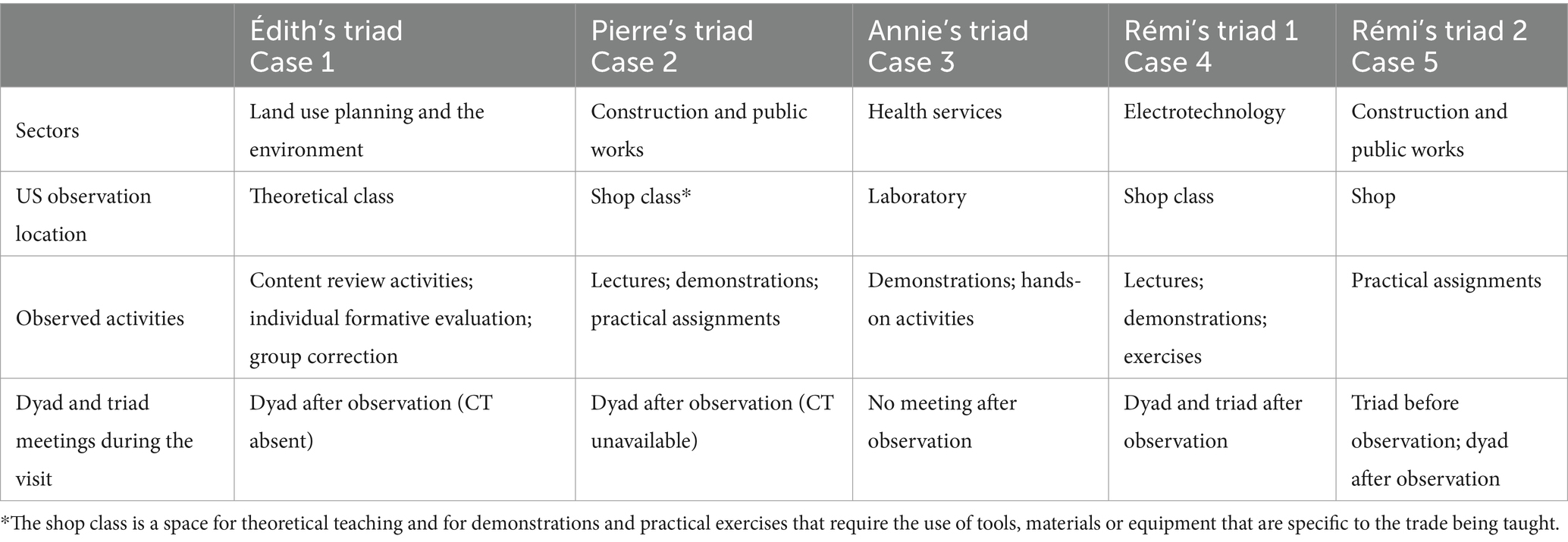

First, we outline the supervision context for each triad. Table 3 shows a wide range of training environments and sector areas supervised in vocational training. For all triads except Annie’s, the visit took place in person at the VTC.

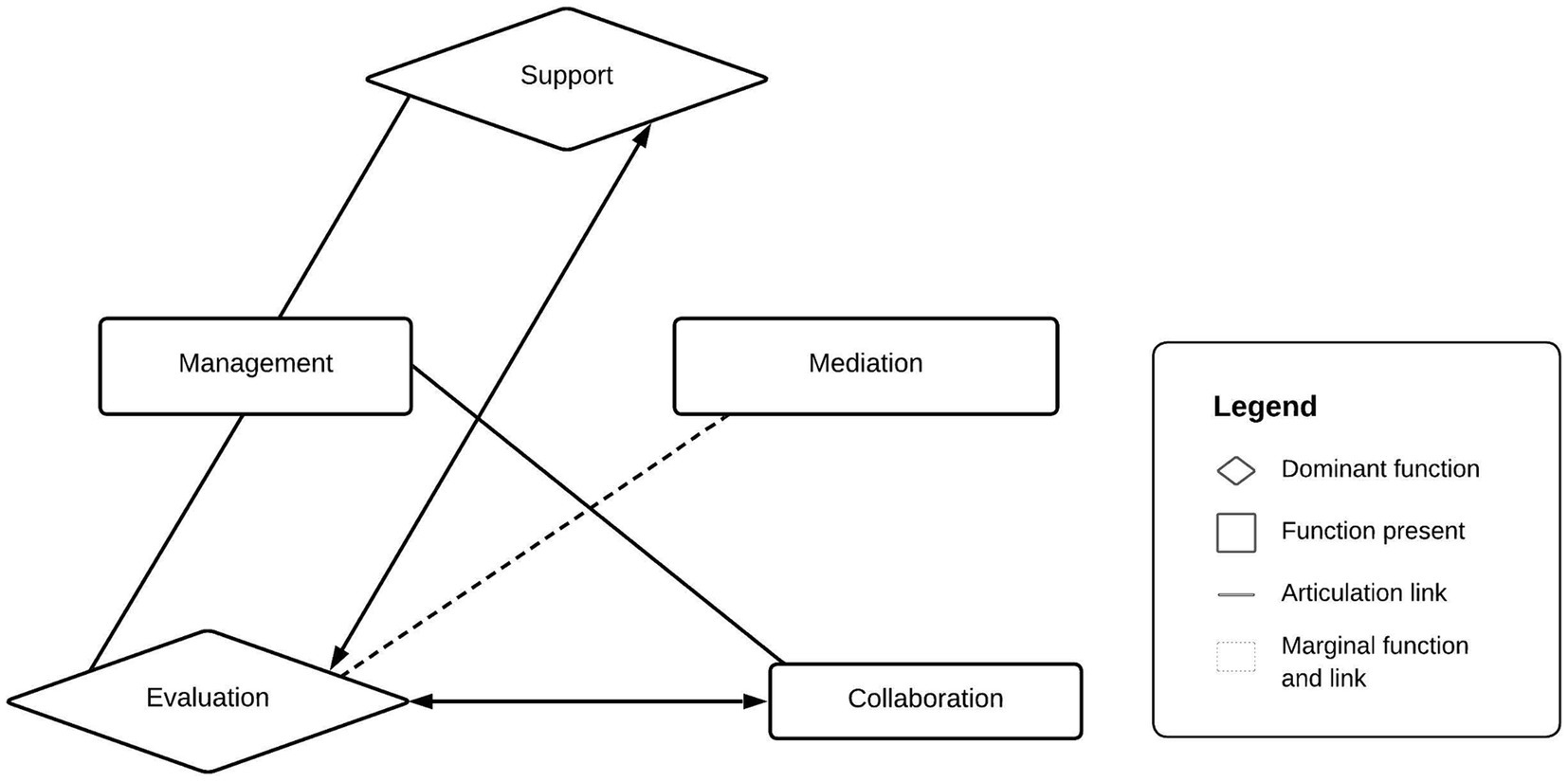

The following parts of the findings section contain a summary of each triad highlighting the links between the functions and specificities of the supervision practices that emerged from the data analysis. A diagram was produced to illustrate the articulation between the functions and their importance to the university supervisors from each triad (see Figures 2–6). Functions classified as dominant are those that incorporate the most actual practices. These practices were addressed during interviews and observations, revealing that they are more important for supervisors. Functions classified as marginal include practices that came up infrequently during interviews or were directly observed rarely or not at all. The same logic applies to relatively infrequent, marginal or absent links between functions. The arrows illustrate aspects revealed in the portraits regarding articulations between the dominant, present and marginal functions. The diagrams were designed to mirror the supervisory function analysis framework shown in the conceptual framework (see Figure 1). All the data was originally collected in French and subsequently translated into English for the purpose of this article. The following legend is used to identify the origin of the excerpts: INI for the initial interview, FUI for the video follow-up interview, and VID for the video recording.

5.1 Édith’s triad

In light of the supervisory practices observed and described by Édith in this triad, significant links were identified between the support and evaluation functions, particularly thanks to the feedback provided throughout the internship. Figure 2 depicting how functions were articulated in this case also shows the positioning of management practices, which often corresponded to decisions that met the needs of the student teachers and contributed to the success of the internship. The mediation between theory and practice function was positioned in relation to the two main functions in Édith’s case. Finally, the collaboration function appeared to be decreasing in importance due to the physical absence of the cooperative teacher from the triad and the university supervisor’s disengagement with this function, which affected her evaluation practices.

The first link identified was between the support and evaluation functions. Through various groups and individual feedback strategies, Édith maintains the relationship and prompts the student teachers to reflect through written or verbal dialogue once her work is done and after making her observations. She explained:

[In assignments], I include questions: how could you teach this content? You know your area of expertise; how can you teach it to students? I get them thinking about that as well. There’s collaboration that happens when I provide feedback, which is ultimately formative and what the teacher is going to send back to me (INI).

She added: “Whenever there’s an observation, we talk to each other. We tell each other what we have experienced and whether it was remote or in person. I think that’s essential” (INI). In addition to contributing to the support function, evaluation was also directly linked to the mediation between theory and practice function. By observing a content review activity and a formative evaluation, Édith was able to compare the student teacher’s planning with the contents of the training program and the evaluation tool given to the students. She was also able to make a number of observations:

I was actually trying to connect the formative aspect to the skill components. To draw a connection between what I saw of the volume, the skills that needed to be learned and the formative aspect. Which I had a lot of trouble doing, since I wasn’t able to pinpoint specific things (FUI).

Her observations were used to provide immediate feedback and support mediation between the theoretical requirements of the vocational training program and their application by the student teacher. This also impacted the type of support Édith provided when she was aware that the student teacher, who was new to teaching environment and land planning, had not quite mastered these aspects: “This teacher only has 3 years of experience. When you are first starting out as a teacher, you do not really make those connections” (FUI). She directed the student teacher (Glickman et al., 2014) to reference materials for her program and asked her to redo a planning exercise to get a more accurate assessment of her planning skills.

For certain internship management decisions, Édith’s actions fell under both support and evaluation. For example, she sometimes extends assignment due dates to a student teacher’s request or modifies her supervision schedule to help the trainees progress and assist them with planning. Regarding one student teacher to whom she had already given extensions on assignments and whom she had continued supervising after the end of the term, she justified her decisions as follows: “He has excellent thinking skills. His teaching is good and his assignments are impeccable. But because he does not hand in his assignments, he’s going to fail? That’s not right!” (INI). These decisions primarily fall under management, as they pertained to overall internship organization (schedules, availability, submitting assignments, etc.). However, Édith’s decisions also assist with support and evaluation by applying differentiated supervision principles (Glatthorn, 1984) to meet student teachers’ needs without changing the internship objectives.

The link between the management function and evaluation function was also apparent in the way Édith scheduled her VTC visits. Despite the high number of student teachers in the term the research was conducted, Édith planned the internship around their availability, adapting to the various vocational training settings and the complex nature of internships. As she explained:

I have a student who teaches healthcare and is still doing an internship [with her students], except for the next 3 weeks, when she has theoretical teaching, lab, etc. […]. In cases like that, I start with the student who has something very specific so I can go to observe them during that time (INI).

Furthermore, the type of teaching situations that she can observe to assess student teachers’ performance is also a factor that influenced her decisions. For this triad, Édith was surprised to find herself sitting in on a content review session. Finding this type of instruction less useful for observing teaching practices, she noted that she could have rescheduled her visit if she had been informed ahead of time:

I still had three or four free days. Instead of going in for that period, I would have gone to another. That’s why I say that sometimes, students arrange for the observation to be a little less intensive. That’s fine, but it means I need to be even more careful when scheduling visits (FUI).

Finally, a link between management and support was apparent in her choice of digital tools. Édith said she prefers the in-person aspect of the blended-learning system and considers the remote aspect less conducive to building relationships with her student teachers. Nevertheless, Édith selected digital tools that facilitate remote communication between her and the student teachers, recognizing the value of using web conferencing from the beginning of the internship to build relationships with the student teachers quickly: “Contacting them by Skype and seeing them beforehand helps me get my bearings. I get that part out of the way” (INI).

Conversely, collaboration was not a function that was articulated with the others. During her visit, Édith learned that the cooperative teacher was on leave. The cooperative teacher’s absence made the evaluation process more complex for Édith, who had to compensate for the limits of her professional judgment with a longer self-regulation process. In the dyad, she noted how her observations were limited: “I wish I had gotten the cooperative teacher’s opinion too. I can only give my own opinion, which is fairly arbitrary” (FUI). This absence also made it more challenging to provide feedback, which was entirely based on her own observations: “It’s as if there’s a missing link, in the sense of having someone else there to observe and say that yes, I’m emphasizing this, or that we did not emphasize that” (FUI). The unavailability of this triad’s cooperative teacher underscored Édith’s progressive abandonment of practices associated with the collaborative function. Over the years, after making a variety of attempts to include the cooperative teacher in the triad, she now simply creates the necessary conditions to establish a basic partnership (Gervais, 2008) without expecting any further contribution during the internship.

5.2 Pierre’s triad

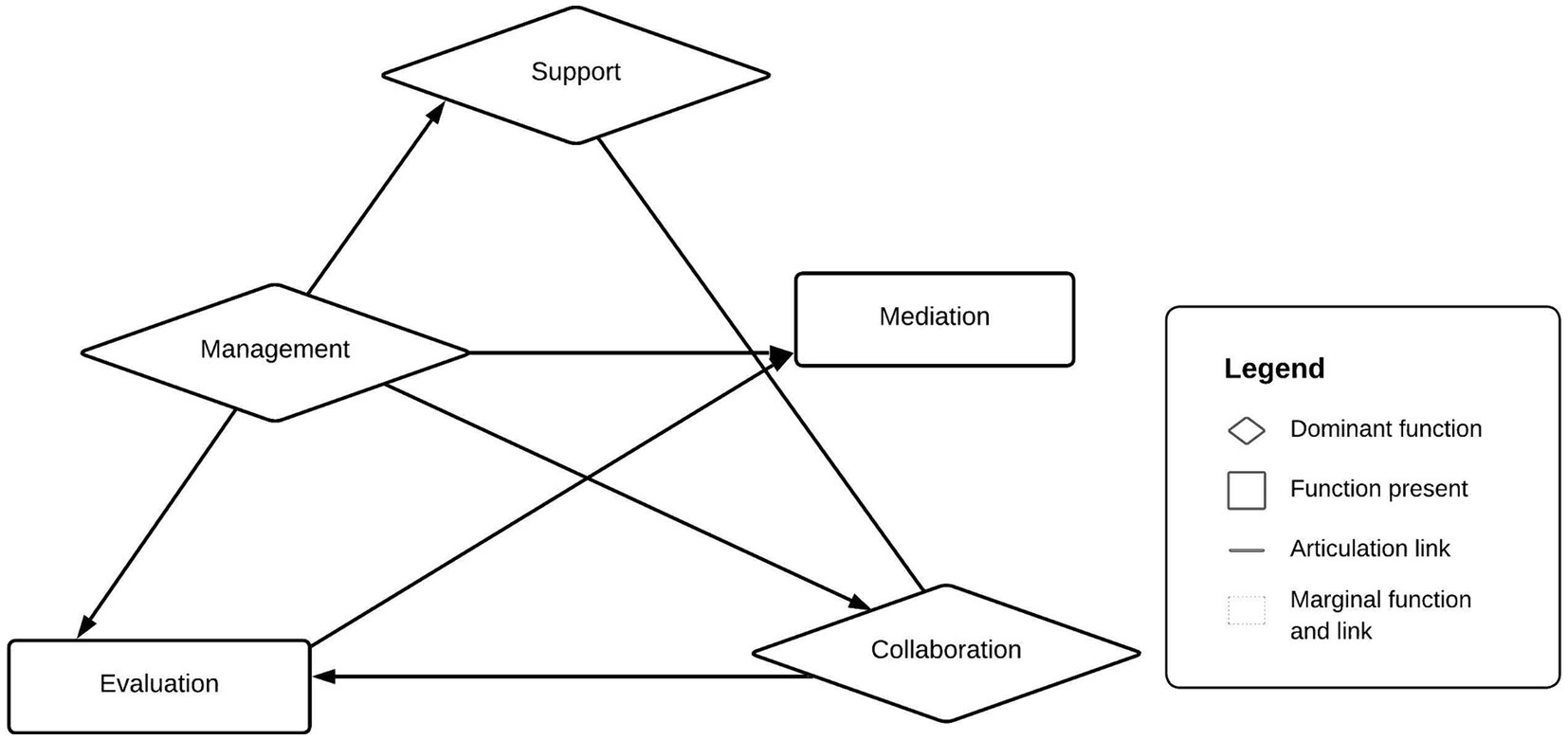

An analysis of the interview data and of Pierre’s observations revealed a strong connection between the support and evaluation functions, to which the collaboration function was also closely linked. The one-on-one support Pierre provided also appeared to be a determining factor in the way he managed digital tools. Figure 3 depicts how functions were articulated in this case.

Pierre’s main focus in terms of support was the progress of the student teacher, who taught construction and public works. Pierre used knowledge of the student teacher at the beginning of the internship as a baseline: “I take the teachers as they are in that moment: what they are like, how they interact with the students and how I can help them progress” (INI). To evaluate progress during the internship, Pierre set goals for the next observation: “After the first observation, I identify any shortcomings and set two or three goals for the next observation” (INI). Nevertheless, he emphasized that the student teacher should not view the observation as an evaluation. In an attempt to reduce the student teachers’ stress, Pierre explained how he tries to downplay this aspect, despite his belief that it really is an evaluation:

When I see that a student is stressed, I’ll often tell them that I’m not evaluating them, just observing them. I’m just watching how they teach. That’s it. It’s not an evaluation. But when it comes down to it, it is, because we use our observations in our summative evaluation of the internship. But does the student need to be stressed out about an evaluation just then? No. Not at all (INI).

Pierre attempted to distance himself from the concept of an evaluation when he observed the student teachers’ teaching (“I’m observing; it’s not an evaluation”). However, he maintained that despite being formative, evaluations are graded (“in my view, formative evaluations have grades”).

To keep track of the information he gathered about the student teachers, Pierre has developed an organized, systematic evaluation process using indicators and criteria selected with the internship objectives in mind (Leroux and Bélair, 2015). He had also developed a personal observation grid to make sure not to overlook anything he wanted to observe and to justify the final grade he will give. However, he said he does not reveal how each criterion is weighted. According to him, not disclosing the cooperative teacher’s feedback makes it possible to avoid damaging relationships within the triad, given that the cooperative teachers and student teachers are generally colleagues in VET teaching internships. The collaboration function therefore appeared to be linked to the evaluation function. On one hand, Pierre asks the cooperative teacher to help evaluate the student teachers by giving them a grade; on the other, this is included in the final grade without specifically being disclosed to the student teachers in order to maintain a good collaborative climate.

Based on the available data for this case, the practices associated with the collaboration function also appeared to be closely linked to the management function. An email sent to the cooperative teachers at the beginning of the internship showed that Pierre introduced himself, shared documents and issued a few instructions. He also said that he checks with the cooperative teachers by email and via telephone throughout the term to make sure they had been observing the student teachers. While these examples of practices implied a one-way relationship, it was in fact difficult to determine the nature of his collaboration with the cooperative teacher, because no triad sessions were observed.

The management function was also influenced by the type of support preferred by Pierre, who prioritizes communication channels that allowed him to provide student teachers with one-on-one support. Despite working with a blended-learning system that is supported by multiple digital technology options, he prefers synchronous and one-on-one communication: “I prefer verbal communication to the digital learning environment. It’s more personal.” (INI) This statement was corroborated by an analysis of Pierre’s DLE, which did not include an asynchronous group discussion channel. He also prefers telephone calls at the beginning of the internship when contacting student teachers for the first time. He explained: “I find it’s better to start with a phone call. […] I do not want to see how and where they are. I want them to be transparent. That’s why I prefer to start with a phone call” (INI).

The decisions Pierre made to meet the trainees’ needs were also evidence of the link between support and management. Since he had another full-time job, Pierre had limited availability to answer questions or visit the VTCs. However, if he believes the situation is urgent, he will act quickly. For example, if a student teacher is having a problem, Pierre calls them promptly at their request, even if this falls outside his usual availability. He said being able to provide the student teacher with a listening ear, knowing that they are “stressed about their academic performance” (FUI) and that they sometimes need more support to complete their work during the internship.

Finally, the mediation function between theory and practice did not appear to be directly related to the other functions, as demonstrated in Figure 3. Pierre stated in the initial interview that he does not intentionally draw links to theoretical aspects. He also mentioned making a clear distinction between the practical portion of the internship, during which he evaluates teaching performance, and the student teachers’ written work throughout the term. He adds: “I make a clear distinction between them. The practical component is one thing, and the theoretical component is another” (INI). However, when providing feedback after the observation, he explicitly mentioned a theory, referencing authors to remind the student teacher that students retain more information if they are given the opportunity to practice the techniques they are being taught. The mediation function could therefore be associated with the evaluation function, but without establishing a formal link.

5.3 Annie’s triad

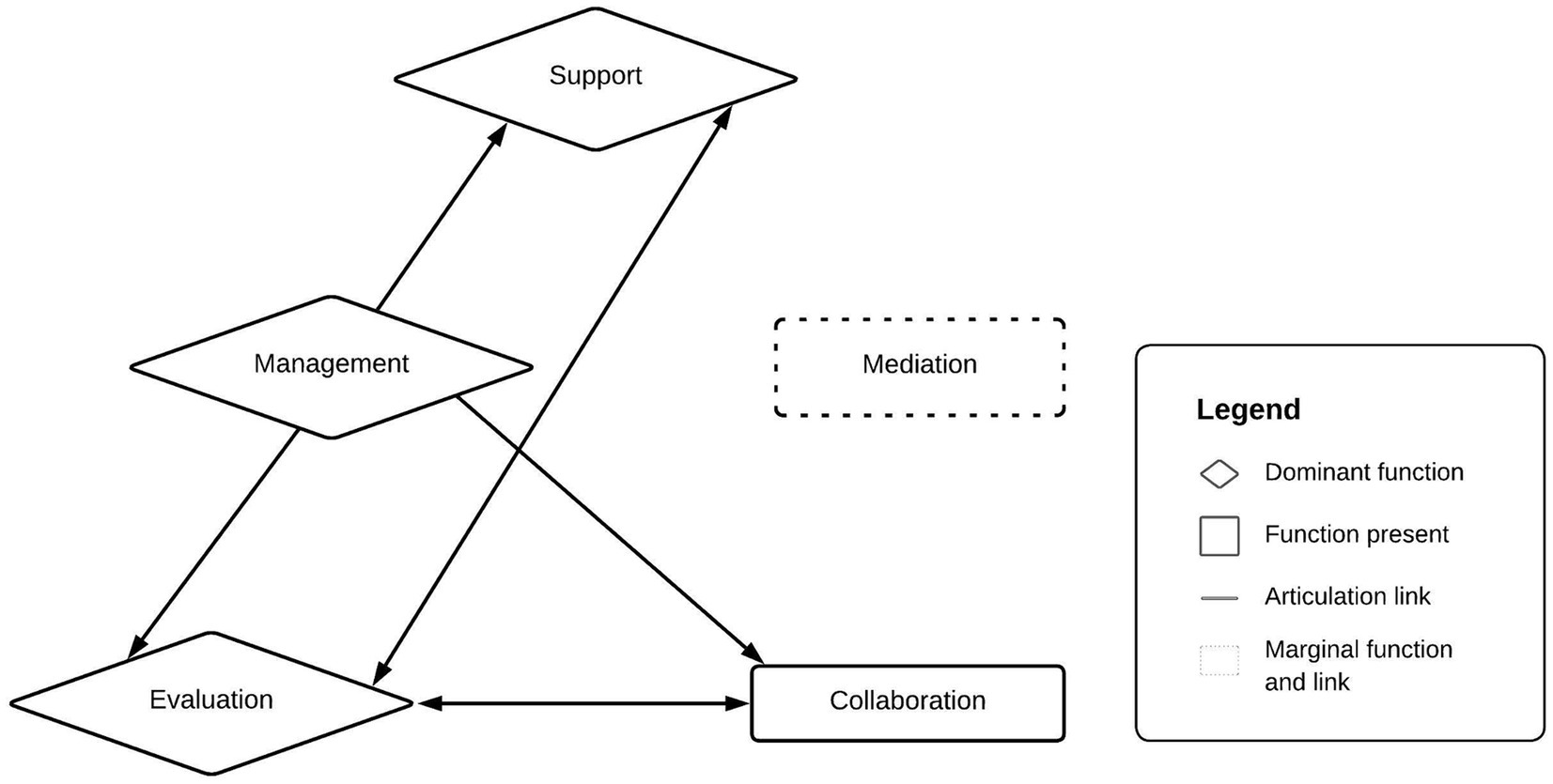

In the case of Annie’s triad, three functions were especially evident from the analysis: support, management and collaboration. In particular, management decisions appeared to influence all the functions that Annie performed throughout the internship. Additionally, by choosing to include the cooperative teacher from the outset in a remote preparatory triad meeting, Annie made collaboration a priority in her supervision. Figure 4 depicts how functions were articulated in this case.

First, the links between management and support were particularly apparent in Annie’s choice and use of various digital tools, which allowed her to maintain a certain presence remotely (Petit et al., 2021). In her view, the written and video messages she shared on the DLE homepage, her contributions to the discussion forums and the numerous emails she sent out to everyone helped build relationships within the group. Regarding the introduction forum, to which Annie was an active contributor, she explained that participating served two purposes: (1) “To establish my credibility, who I am, why I’m supporting them and why I’m qualified to support them” (INI) and (2) “To get to know them: it’s my way of creating a relationship that’s not just cognitive and pedagogical” (INI). She also continually sought to reassure student teachers, both during meetings and in the DLE. Knowing the stress that can arise from a practical training course that includes observations, she said:

I always try to reassure them. I’ve been through the same thing. The less experience student teachers have, the more stressful it is for them. Some have written to me and verbalized that even though it’s their second internship, it’s stressful for them. [There are] a lot of messages to reassure them throughout the term (INI).

When observing the student teacher remotely during lab demonstrations and hands-on activities, she reminded her to behave and move normally, regardless of the camera. Annie explained that the goal of these recommendations was always to reassure the student teacher: “I really wanted her to feel comfortable and to reassure her. That was my goal” (FUI).

From the beginning of the internship, Annie placed a strong emphasis on collaboration. She sought to involve the cooperative teacher by arranging a remote triad meeting at the beginning of the term. In addition to helping manage her visit to the VTC and saving her organizational time, this approach allowed her to witness the close relationship between the two people and to recognize the cooperative teacher’s contribution to the triad. She emphasized their unique role in observing the student teacher, as demonstrated by the following excerpt:

I always say it in writing, but I like to reiterate it and I’ll say it at the final triad: thank you so much for agreeing to support Audrey. Having you there is very valuable to us, because one supervisor can only see so much. We’re not there in the thick of it with the student teacher. So thank you! (VID).

However, she also recognized that not every cooperative teacher is as open or available: “In the middle of the internship, I email them back asking them if everything is OK and if they’d like to have a meeting. Usually, they do not even get back to me, but at least I try.” (INI) Despite this, Annie tries to stay in touch throughout the internship.

Annie’s management practices also influenced some of the evaluation methods she used. She preferred remote observation at the beginning of the term, primarily to avoid having to drive during the winter months when her student teachers were far away from her home. Her travel management also allowed her to adapt to the situation of the student teacher who taught in the healthcare sector and whose schedule was complex and provided few opportunities for evaluation at the VTC during the teaching period. Showing that she was taking her situation into account, she told her: “Once I’ve met all the students and drawn up my schedule, I’ll let you know. If it does not work out, I’ll make a special visit to your VTC. It’s no problem. I try to schedule them all at the same time, but I can also adapt to your situation” (VID).

Likewise, Annie chose to provide feedback in writing (Rodet, 2000), given that the student teachers are often very busy and have trouble finding the time to meet as a dyad at the end of the remote observation period. However, she recognized that this method of communicating the results of the observation is more labor-intensive: “With verbal feedback, you do not have to proofread or pay attention. […] If the person does not understand, they make that clear, either nonverbally or verbally” (FUI). The decision to communicate results in writing had an impact on the way Annie mediated between theoretical and practical knowledge; Annie included references to concepts and theories in her feedback (e.g., explicit teaching, the student-teacher relationship and the sections of a lesson plan). The DLE programming, which is linked to the management function, also allowed her to provide the student teachers in the group with a variety of resources, such as links to other sites on various topics that may or may not be related to the course content.

Ultimately, Annie’s case spoke to the important relationships between the management function and the other functions, as demonstrated in Figure 4. In particular, her choice of tools and the decisions she made to organize the internship influenced her evaluation, support and collaboration practices. For Annie, the beginning of each term is an opportunity to experiment. To explain her organization at the beginning of the internship, she stated the following regarding a digital tool: “I do not like routine. I see how I’m feeling. Like I said, I have not decided which one I’ll use this term. Actually, yes, I think I know which one I’m going to use, and it’s not the same one as in the fall” (INI). She then asks the student teachers questions and reads their comments at the end of the internship to decide whether she will continue using the same approach in future terms.

5.4 Rémi’s triads

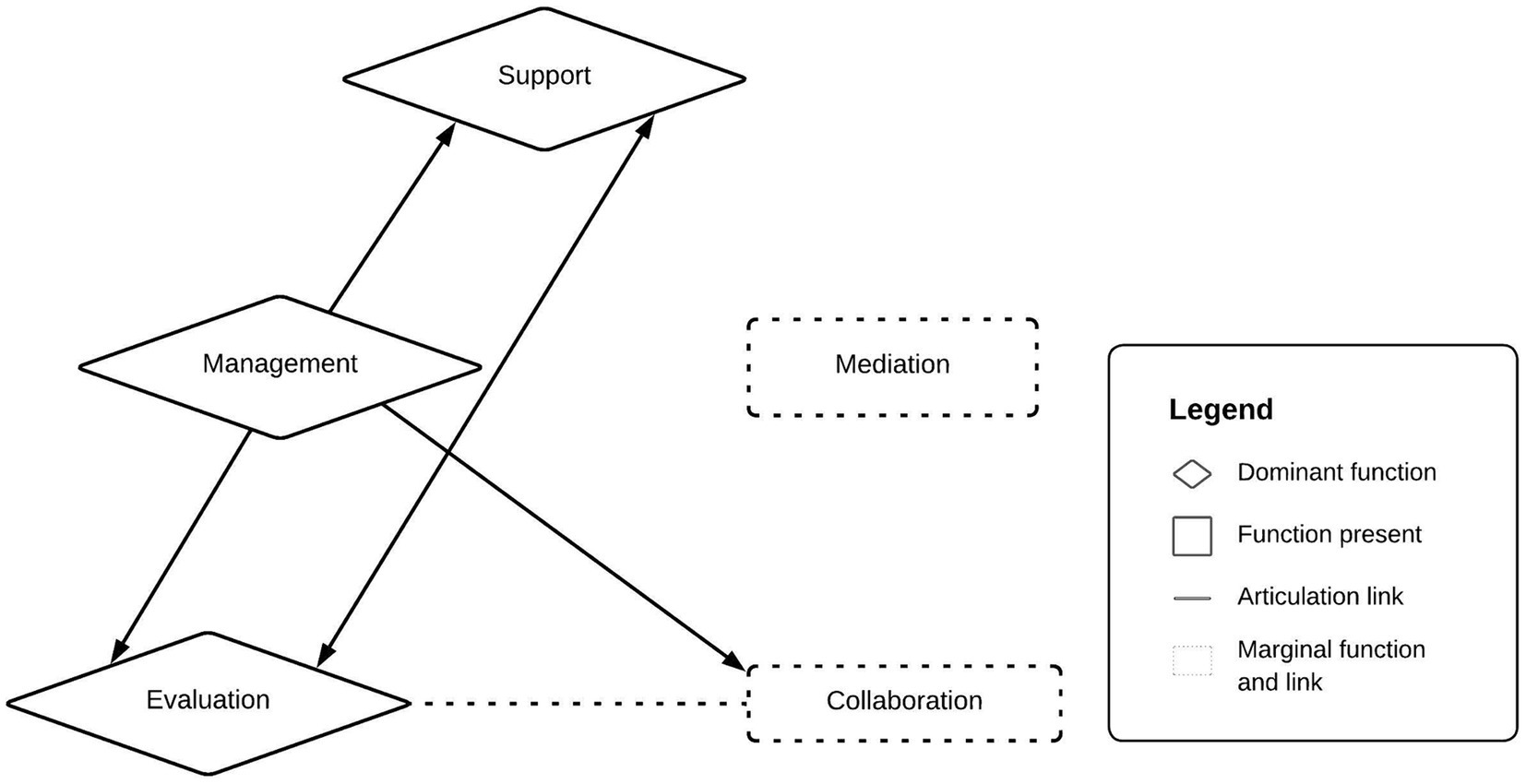

The way functions were articulated in Rémi’s two triads appeared similar at first glance, particularly regarding his internship management practices; this was a function that stands out in both cases. Indeed, the ways he established communication, organized the internship and maintained the relationship to support the student teachers and cooperative teachers were related to the support, evaluation and collaboration functions in both triads. Similarly, the absence of practices related to the mediation between theory and practice function positioned this function in a peripheral position compared to the others. However, even though the connections between support and evaluation were central to both triads, the type of support he provided and his approach to evaluating the student teachers differed, as they were adapted to the specific realities of each triad. Finally, given the cooperative teachers’ different levels of engagement, we could see that Rémi used various practices, which impacted the evaluation function. Figures 5, 6 depict how functions were articulated in these cases.

An analysis of the data revealed significant links between management and support practices from the outset of the internship. For Rémi, being available and responding to student teachers promptly is a key factor that shaped his actions and the digital tools he used. At the beginning of the term, Rémi explained that he establishes a communication strategy that takes student teachers’ potential stress about the internship into account:

They’re often scared when you call them. I can hear it in their voices. Shortness of breath, trouble speaking. They’re very nervous. So, for me, one of my priorities is to make myself available, put them at ease and make them feel comfortable communicating. Making sure we are able to talk is my priority (INI).

By prioritizing one-on-one support through multiple communication channels, he said he can “deliver on his promises” of being constantly and readily available, given the vocational training student teachers’ characteristics.

That’s what I tell them from the very first interview: Do not struggle with an issue all by yourself. I know you work evenings and I know you work weekends, so for me, it’s not OK for you to struggle all by yourself. […] I do not have a set schedule. That’s what I tell them. I try to keep them waiting for as short a time as possible (INI).

Illustrating his ability to always be available and to support student teachers in their use of digital technology and internship activities, Rémi described himself as a “technology polyglot.” The data also showed that student teachers from both triads had numerous phone calls, text messages (SMS), emails and a few discussions on forums with Rémi to inquire about various topics (assignments, availability, observation visits, etc.). According to Rémi, the digital tools he uses for supervision also enabled him to collaborate remotely with the cooperating teacher to conduct a joint evaluation while observing the student teachers’ teaching, thus forging a new connection between management and collaboration functions. However, it was not possible to observe this type of collaboration in either triad.

The links between support and evaluation were also clearly visible in both triads. However, Rémi’s attitude to evaluating the student teachers differed, which impacted the way he supported each of them. In the first triad (Figure 5), for example, Rémi drew on practices associated with remedial support (De Ketele, 2014), claiming to be searching for anything “not normal” in the teaching practices of the electrotechnology student teacher he was observing for the first time. As he explained, “I was bothered by the fact that he wasn’t asking enough questions. He was just giving answers. When I looked more closely, there was definitely something that bothered me about the way he was working with the students” (FUI). In the post-observation meeting, Rémi’s aim was to “make the student teacher aware of” the benefits of changing some of his practices. He focused on specific aspects of his teaching and asked him questions: “I make him elaborate. I ask open-ended questions and follow-up questions. I’m never satisfied with his answers, and I force him to go further and give me more information” (FUI). Demonstrating maximum responsibility during the discussion (Glickman et al., 2014), Rémi alternated between providing positive feedback and identifying aspects he considered weaker while acknowledging that the trainee was struggling with receiving his feedback: “It’s hard for him. That’s what I’m realizing. Right away, I instinctively start toning down my comments. I hedge my words” (FUI).

With the second triad (Figure 6), Rémi adopted practices that more closely resemble sharing-based support (De Ketele, 2014) when dealing with a building and public works student teacher he had previously supervised. Regarding his approach to this student teacher, he explained:

With him, I was mostly confirming things. I found nothing or almost nothing new, only tiny improvements, or this evening, just a small improvement from my first evaluation of him. I came away from supervising him in the previous internship feeling very energized. I was really impressed by him as a teacher, and I still am (FUI).

Rémi’s goal for the observation was mainly to confirm what he already knew about the student teacher. Although he still provided prescriptive feedback, Rémi primarily relied on the student teacher’s prior knowledge to justify his comments (De Ketele, 2014). The dyad’s post-observation meeting also involved a discussion about the student teacher’s academic studies as he was reconsidering the way he wrote his assignments.

In both cases, support was thus inseparable from evaluation. On one hand, Rémi was looking for shortcomings in a student teacher he was meeting for the first time and whose skill level he was not familiar with. On the other, he recognized and confirmed the existing knowledge of the student teacher he had already supervised and wanted to convey what “[he] has just experienced as a supervisor” during his visit.

As far as collaboration went, Rémi had to adjust his expectations about each cooperative teacher’s involvement, which changed the role collaboration played in the triads, especially in terms of evaluation. When dealing with cooperative teachers, Rémi expected to “receive a lot of information.” As he explained, “the very nature of the relationship between the cooperative teacher and the student teacher is an important factor, because it impacts my collaboration” (INI). In the first triad meeting held during the VTC visit, Rémi noted that the cooperative teacher had conducted observations and held meetings with the student teacher beyond what was required for the internship. As a result, Rémi was able to discuss and confirm his observations on various topics. He also instructed the cooperative teacher about the coming phases of the internship, telling him how he had contributed to his supervision work: “You’ll have one more observation between now and the end and we’ll have one more triad to do. I’m going to want your input. Another issue is the collective aspect. I’m not here […]. I’ll need your opinion” (VID). He also took the opportunity to initiate a discussion about various aspects of VET teaching practices. However, he acknowledged that the collaboration is sometimes limited: “It is not always possible, depending on the cooperative teacher, because I can only respond to them. I’ve had cooperative teachers who would not or could not have that type of discussion with me” (FUI).

With the second triad, the fact that the cooperative teacher had not conducted any observation since the beginning of the term meant that, despite wanting to, Rémi was unable to rely on a real contribution from the cooperative teacher to assist with his evaluation. In his words, “I’ll be honest: I do not think there was much observation planned. My understanding is that I will not be able to ask him about his specific observations in the classroom” (FUI). During Rémi’s visit, despite his questions and interest in engaging the cooperative teacher in the exchanges, the cooperative teacher contributed very little to the discussion and any collaboration remains limited. As a result, the collaboration function was marginal in this triad (Figure 6), despite Rémi’s efforts to include the cooperative teacher in his visit.

In both cases, as demonstrated in Figures 5, 6, few practices fell under the mediation between theory and practice function. Rémi used vocabulary that was specific to VET teaching, the competency framework and the approach taken by the bachelor’s degree program; he said he checked the cooperative teacher’s understanding of the subject. However, no data confirmed the presence of practices related to support or establishing links between theory and practice with or for the student teacher.

6 Discussion

This section discusses the findings considering three themes: the variety of practices within a single institutionalized blended-learning supervisory system, the impact of the VET teaching internship context and the ambiguous role that the mediation between theory and practice function plays in university supervisor practices. These discussion themes answer the initial question, which aimed to identify the specificities of the practices of university supervisors of VET teaching internships in a blended-learning system. The themes help shape the portrait of supervision practices in the context described in the research question.

6.1 Practices that are varied, but framed by a system

In this study, the university supervisors articulate supervisory functions within an institutionalized blended-learning supervisory system. The program internships in which the triads operate are based on a system that is comparable to a closed learning environment as described by Jézégou (2019). University supervisors are not free to modify its structure, which is shaped by the system’s functional reference dimension (Albero, 2010), which in turn determines the pedagogical approach (clinical supervision) and documents that are used. This system is based on the remote supervision model developed by Pellerin (2010), with the addition of an in-person component when the university supervisor visits the VTC. Our findings show that the functions are articulated in each triad in a similar way, making support a dominant function for all university supervisors. The management function, which encompasses practices that require the use of digital technology to supervise remotely and in person within a blended-learning system, is linked to support and evaluation in all of the triads. However, it should also be noted that despite being present and strategically linked to the support and evaluation functions, the management function for two triads (Édith’s and Pierre’s) is not predominant despite the significant role of digital technology in the blended-learning system. Édith stated that she preferred the in-person aspect of the system and used digital technology because the system requires it, while Pierre preferred to make phone calls during the internship and did not provide the student teachers with any group tools such as a forum to ask questions or have discussions on the digital platform.

Despite these commonalities, some individual supervisory practices also vary greatly from one triad to another. Indeed, as Albero (2010) explains, the actual system entails a subjective interpretation by those who use it. For example, the way each university supervisor used digital tools, the one-on-one and group support they provided, the development of certain observation tools, the evaluation procedures, the feedback mechanisms selected, the order of the triad and dyad meetings and the sequence of remote observations all varied. On one hand, the findings show that the way the university supervisor’s functions are articulated is in keeping with the supervisory model imposed by the system. On the other, it also appears that they are reflected in multiple practices, tailored specifically to each triad and based on each person’s unique approach (Altet, 2000; Bru, 2002).

6.2 Impact of the VET teaching internship context on university supervisor practices

The specific context of the VET teaching internship impacts the practices used by the university supervisors. Given that student teachers complete their internship on the job, the findings indicate that the university supervisors are concerned with facilitating and supporting their progress and ensuring their success. This is particularly apparent in the links between the support, management and evaluation functions in every triad. Indeed, despite being responsible for applying institutional constraints to the work and activities being evaluated (Chaubet et al., 2013), the university supervisors are flexible and tailor their decisions to the student teachers’ characteristics. Being available, answering questions quickly, reassuring student teachers, mitigating stressors and building relationships are all university supervisor practices that emphasize the support function for student teachers, who do not always find it easy to balance the various facets of their student, professional and family lives (Deschenaux and Tardif, 2016).

Our findings also show that the VET teaching context that positions cooperative teachers and student teachers as colleagues has a particularly large impact on the collaboration and evaluation functions while supervision is ongoing. Frameworks that describe relationships within the triad traditionally place the cooperative teacher in a central role in relation to student teachers. For Gervais and Desrosiers (2005), the university supervisor assists the cooperative teacher with their work, discusses the student teacher with them and helps them with their assessment. Conversely, Portelance et al. (2008) credit the university supervisor with a leadership role within the triad, working in collaboration with the cooperative teacher and establishing a co-training relationship with them. Additionally, Gervais (2008) mentions that both the university supervisors and cooperative teachers must take action to create a real partnership for the student teachers’ benefit. Our findings show that the university supervisors in the triads studied do demonstrate a form of leadership and use practices to support and emphasize the value of the cooperative teachers (emails, various check-in, phone calls, offering support, a triad at the beginning of the term, specific instructions, and requests, etc.). All university supervisors also stress the importance of seeking the cooperative teacher’s input to evaluate the student teacher.

Despite this, it has not been possible to identify or describe a truly reciprocal partnership being established between a university supervisor and a cooperative teacher (Gervais, 2008), whether to evaluate or support the student teachers. Moreover, even if the university supervisors used collaboration practices, the cases demonstrate the university supervisors’ dependence on the cooperative teachers’ commitment to collaboration. Both of Rémi’s cases are revealing in this regard. While the practices he used to establish contact and schedule meetings were the same from one triad to the next, collaboration was completely different because of the two cooperative teachers’ unequal contribution. In two other cases (Pierre’s and Édith’s), this collaboration was superficial or even non-existent due to the cooperative teacher’s absence during visits. Édith’s past experiences had led her to have no expectations about the cooperative teacher’s contribution to the triad. In Pierre’s case, although he included the cooperative teacher in his evaluation process, the fact that the two individuals were colleagues affected his practices.

As a result, although the university supervisor should have a co-trainer in the workplace, our findings suggest that the university supervisor is completely or partially alone in every role, thus becoming sometimes the student teachers’ only trainer. Contrary to what has been written about the university supervisor’s contribution, they appear to be an essential member of the triad when the placement is in the workplace. Consequently, we believe that the university supervisor’s role should be redefined and (most importantly) valued within the triad, where the unequal involvement of the co-trainers is a far cry from traditional models.

6.3 The absence or marginalization of mediation between theory and practice function

Drawing parallels between the content covered in “theoretical” teacher training activities and practical realities is a known objective of the internship. Through their privileged position in the triad as a bridge between the university and the workplace, the university supervisor is generally assumed to play a key role in drawing these connections between theory and practice (Jacobs et al., 2017). Veuthey (2018) further states that internship settings expect the university supervisor to help student teachers “justify [their] choices by drawing connections with theory and backing up [their] statement with references” [translation] (p. 358). Caron and Portelance (2017) have also clearly shown that student teachers see that the burden of drawing on formal, scientific knowledge falls on the university supervisor, whereas they see the cooperative teacher’s role as more of a response to everyday events and immediate action in the classroom. Despite this perceived function, our results suggest that university supervisors are reluctant to highlight or make these connections between theoretical knowledge and lived experience during the internships. For three triads, no practices incorporate mediation into the patterns by which the university supervisors’ functions were articulated. Rémi stated that he was unfamiliar with the subject matter of the student teachers’ courses. Additionally, despite explicitly referring to authors, Pierre admitted that he did not consciously draw links between theory and practice. While Édith and Annie did make connections between observation and theory in their feedback, only Édith questioned the triad’s student teacher more thoroughly to determine what connections she made between her teaching planning and the prescriptive documents of the profession she teaches.

According to Deprit et al. (2022), prompting student teachers to reflect on their practices during the internship lays “the groundwork for links between theory and practice.” However, even though university supervisors ask student teachers about their experiences and encourage them to reflect on various topics during the internship, Bocquillon et al. (2015) argue that this does not necessarily ensure that they do reflect, or link lived experiences to formal content. To highlight these connections in student teachers from a professionalizing perspective, Vivegnis et al. (2022) argue that the university supervisor must adopt a particular support approach for which specific theoretical training is required. Indeed, the work of Vivegnis et al. (2022) reveals that student teachers, who are rarely able to apply scientific knowledge during their internship, should be supervised by trainers, provided that the trainers themselves are sufficiently trained and knowledgeable. Similarly, Gouin and Hamel (2022) point out that university supervisors sometimes have trouble drawing parallels between theory and practice because they have limited knowledge of the subject matter of the student teachers’ theoretical courses, which aligns with Rémi’s statement. Given that the university supervisors in the triads studied did not receive any supervisory training from the university, there is reason to believe that this has an impact on the mediation between theory and practice function during the internship.

In addition to identifying the university supervisors’ training needs, we must also ask ourselves whether the digital system used is conducive to providing reflective support during the internship. By the results, we know that these university supervisors make themselves available to student teachers promptly and by various means and that they care about meeting their needs. In this way, they provide an affective type of support remotely (Peraya et al., 2014) that is aimed at reassuring trainees and building relationships of trust (Villeneuve and Moreau, 2010). However, most of the action observed through the digital environment in the first half of the internship was one-on-one. Rémi, Édith and Annie set up forums where student teachers could ask questions and introduce themselves, but these were mostly used to impart information rather than to produce or collaborate (Peraya et al., 2014) from a reflective perspective. And yet, according to Collin and Karsenti (2011), “reflective practice support systems would benefit from providing moments of individual reflection (intrapersonal level) that would feed and be fed by moments of collective reflection (interpersonal level)” [translation] (p. 55). A blended-learning supervision system where student teachers are isolated from each other could therefore benefit from more group activities to “prompt reflective dialogue” [translation] (Caron and Portelance, 2017, p. 45) in groups and with the university supervisor. However, regardless of whether these activities are initiated by the university supervisor or integrated into the mandatory blended-learning supervision system (Jézégou, 2019), implementing them remotely or in person is a reminder of the need to train university supervisors to promote reflective support for trainees from a mediation between theory and practice standpoint.

7 Conclusion

Burns and Badiali (2015) see the university supervisor as the least valued person in pre-service teachers’ education, despite significant knowledge, skills and abilities they must leverage in their supervision. As our findings reveal a wide range of supervisory practices, it would appear that the university supervisor’s role in the VET teaching internship triad is critical and should not be underestimated. Support and evaluation practices were predominant in almost all the triads. It is clear that practices relating to internship management function, particularly those pertaining to the choice and use of digital tools to support and evaluate student teachers in a blended-learning system, were present in all triads, if not dominant. However, even if the university supervisors used practices that fall under the collaboration function, they appeared to vary from one triad to another depending on the cooperative teacher’s involvement, which had an impact on the evaluation function. Finally, our findings revealed the limited role of mediation between theory and practice and the weak links that this function had with the other functions within the triads studied. This last point suggests that further research is needed on this subject, but above all, it speaks to training issues for university supervisors, who are not necessarily prepared for this function (Gouin and Hamel, 2022). For Butler et al. (2023), university supervisors require preparation, but also a better recognition of the complexity of their work within institutions. For these authors, supervision is much more than a technical practice and it requires “support, structures, and resources for those engaging in and learning the work of supervision” (p. 58).

One of the main limitations of the findings presented in this article is that data collection was interrupted halfway through the term. This meant it was not possible to obtain data to see if the way the functions were articulated changed along the way. Although the initial interview with the university supervisors provided us with information on their reported practices through a full internship, we do not have the full picture necessary to analyze their actual contextualized practices when observing the student teacher for the second time and at the end of the internship. Similarly, our sample includes only a few university supervisors who supervise a specific BVE program. Considering that the number of remote university training programs has increased in recent years (Bates, 2022), it would be necessary to collect different types of data using larger samples and from other programs where blended-learning systems play a key role in internship supervision.

Second, although the cases under study are triads, the student teacher and cooperative teacher continue to be indirect participants about whom no data was collected. This is justified by the research objectives, which focused on the university supervisor’s practices in the context of a BVE. Now that we have some initial insights into university supervisor practices in VET teaching internships, it will be useful to take a closer look at the other two members of the triad in this subject area, particularly the student teacher.

Indeed, now that we know that the cooperative teacher in the vocational education triad does not necessarily perform the full role traditionally assigned to them with student teachers (Gagné and Gagnon, 2022), it seems important to pursue this research to better understand the dynamic within this unusual triad. The findings presented in this article show that supervisors use practices intended for collaboration with the cooperative teacher, but the analyzed data does not permit a more detailed description of the nature of the collaboration within the triad or confirm whether it is true collaboration (Boies, 2012). In light of recent research by Gagnon et al. (2023) regarding obstacles faced by cooperative teachers in vocational education, it is essential to ask questions to the triad as a whole and find out what relationships are being created, what type of collaboration exists between the trainers and what student teachers think of this type of support. For a next project, it would be interesting to conduct interviews with all three members of several vocational education triads from different universities and even from different teacher education programs.

This is of particular interest, given that the current teacher shortage means that an increasing number of teaching candidates are getting a job before completing their training in the United States (Craig et al., 2023) as well as in Canada (Sirois et al., 2022). This means that teacher training internships on the job are no longer a negligible or exclusive reality in the field of vocational education.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Comité d’éthique de la recherche—Éducation et sciences sociales—Université de Sherbrooke Comité d’éthique de la recherche—Université du Québec à Rimouski. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LD: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CG: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MP: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^In Quebec, vocational training (VT) prepares students for the workplace. It is available to students as young as 16. VT includes more than 150 programs ranging from 600 to 1,800 h in length and spanning 21 sectors areas. It is offered at vocational training centers (VTCs) across Quebec (Gouvernement du Québec, 2023).

2. ^This research was conducted for a doctoral thesis. The use of the pronoun ‘we’ identifies the doctoral candidate and her supervisory team.

References

Acheson, K. A., and Gall, M. D. (1987). Techniques in the clinical supervision of teachers:Preservice and Inservice applications New York, NY: Longman. (Accessed October 31, 2023).

Albero, B. (2010). De l'idéel au vécu: le dispositif confronté à ses pratiques. In B. Albero (Ed.), Enjeux et dilemmes de l'autonomie. Une expérience d'autoformation à l'université. Étude de cas. Maison des Sciences de l'Homme. Available at: https://edutice.archives-ouvertes.fr/edutice-00578668 (Accessed October 31, 2023).