94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 04 April 2024

Sec. Teacher Education

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1330819

This research focuses on the activity of six tutor teachers in training involved in the curriculum of primary student-teachers at the University of Teacher Education in Lausanne, in Switzerland. The post-lesson interviews managed by these tutor teachers in training show that their activity is influenced from past experiences lived as student-teachers and from the training they are following. This research aims to understand and analyze the origin from the tools used to mentor their student-teacher during the post-lesson interviews. The theoretical framework uses the concepts of the clinical activity and the method of self and crossed confrontation interviews. Through the real activity of tutor teachers in training, exposed through the methodologies of self-confrontation, our results highlight the influence of past experiences of tutor teachers in training, as well as the nature of the emotionally significant situations they experienced in the past. The influence in their actual activity as tutor teachers in training and which tools they are using from the training are also presented and discussed.

Current issues in teacher education, such as the emotional overload that often leads beginning teachers to drop out or experience attrition, are subjects of active discussion. The societal significance of teacher training and professional development should prompt deeper reflection on the underlying causes of dropout rates. Teacher education programs, especially those involving mentor teachers, have the potential to mitigate this phenomenon more effectively.

Entering the teaching profession, as depicted in the literature, is a notably intricate and emotionally charged phase (Stewart and Jansky, 2022), akin to navigating a whirlpool, as Erb (2002) symbolically portrays. During these initial years of a teaching career, emotions tend to run high, seldom remaining static, and can ultimately culminate in emotional overload or attrition. This initial emotional burden at the onset of a career (Squires et al., 2022) appears to contribute significantly to the disproportionately high dropout rates among novice teachers in Western educational systems (Rajendran et al., 2020; Amitai and Van Houtte, 2022).

In the United States, for instance, statistics reveal that 14% of novice teachers exit the profession after their first year, followed by 33% after three years, and a staggering 50% after just five years of teaching (Hong, 2010). This phenomenon of attrition, attributed in part to the challenges faced during the initial stages of their careers, may be partially ascribed to insufficient consideration of the emotional dynamics inherent in student interactions (Hagenauer et al., 2015), as well as inadequate acknowledgment of prior experiences in teacher education (Russell and Fuentealba, 2023).

This research focuses on the activity of tutor teachers in training (TTT) during the post-lesson interview. As part of the dual education system at the Institute of teacher education in Lausanne in Switzerland, student-teachers from the bachelor’s degree in primary education are teaching in school placements. The TTT must do post-lesson interviews each time he or she observes a student-teacher teaching in school placement. However, the efficiency of the post-lesson interview modalities shows reservations in the literature, especially regarding the tools that student-teachers need, to foster the development of the student-teachers activity (Bertone et al., 2009).

This research aims to understand and analyze the influence of past experiences on the activity of TTT. More specifically, it focuses on the experiences that TTT had as student-teachers (emotionally significant) and those they have now as TTT studying in the CAS (Certificate of Advanced Studies) to become a tutor teacher. While some past experiences may carry significant emotional weight and directly influence a tutor’s behavior, not all experiences need to be emotionally impactful to influence them. The research will focus on past experiences with significant emotional weight (perezhivania). The goal is to understand which emotionally significant situations they experienced in the past influence their actual activity as TTT and which tools they are using from the CAS.

In the county of Vaud in Switzerland, teacher training takes place in two environments, the Institute of teacher education and directly in schools with students ranging in ages from 4 to 12. Student teachers are required to develop professional skills by articulating academic, theoretical, and practical knowledge (Gremion and Zinguinian, 2021). The Institute of teacher education provides a dual education by mandating tutor teacher (TT) to teach student-teachers professional skills in school placements. They also assess their teaching practices in reference to their level of teaching competences. Following the works of Dewey (1904), Argyris and Schön (1974), the Institute of teacher education gives an importance to reflective practice in teacher training. In this sense, it appears that the post-lesson interview (Talérien et al., 2021) constitutes a pertinent way to foster student-teachers in the development of this reflective competence.

Tutor teachers undertake this role voluntarily with the agreement of their school principal. To be allowed to practice as tutor teacher, they must attest at least 10 years of teaching experience and complete a CAS proposed at the Institute of teacher education. During this training course, TTs are trained in organizing the placement, accompanying, and guiding student-teachers in their teaching. According to the institutional guidelines (Haute école pédagogique du canton de Vaud, 2021, 2022b,c), the TTs set up a contract with his/her student-teacher that specifies their respective expectations and needs. The TT’s activity consists of observing the lessons given by the student-teacher, taking notes about the teaching that will be discussed and shared in the post-lesson interview which may take place right after the lesson or postponed to shortly after. The choice to postpone the interview may be linked to organizational constraints, or it may be a pedagogical intention to foster the student-teacher’s reflective practice. Thus, the TT observes, analyses, and assesses the student-teacher’s competences through oral feedback during the post-lesson interviews. This feedback is formalized in an assessment report at the end of the semester, then in a certification assessment (through 10 competences, Haute école pédagogique du canton de Vaud, 2022a) at the end of the school placement. Moreover, the student-teacher must show a capacity to reflect to his/her practice (Haute école pédagogique du canton de Vaud, 2004/2016). Finally, the background from TT as student-teacher may also influence the way he or she organizes, observes, and analyses the student-teacher in the internship. Following the works of Dewey (1904), the learning is lived like the transition from experience to knowledge. During their activity, TT use their experience and formalize it into knowledges, whether during observations or during post-lesson interviews. Indeed, if we consider that expertise as tutor teacher profession is the result of a multitude of “sedimented” experiences (i.e., what the TT lived as a student-teacher) (Rogalski and Leplat, 2011), we can also argue that regarding to the emotional part of teaching expertise, specific moments, (i.e., “episodic experiences” what TT learned during TT training), have a particular effect on the activity.

During the post-lesson interview, the TT asks the student-teacher about his or her intentions and his or her feelings about the lesson. Through his/her interventions during the lessons, the TT leads the student-teacher to reflectively look at his/her teaching activity (Argyris and Schön, 1974) and to suggest to himself/herself ways of improvement. The post-lesson interview is also an opportunity to help the student-teacher anticipate future teaching and to discuss the challenges and difficulties of the teaching profession.

The post-lesson interview is an important factor in the student-teacher’s professional development (Talérien et al., 2021), as TTs seek to develop student-teachers’ reflective practice, i.e., the analysis of their teaching practices (Haute école pédagogique du canton de Vaud, 2022a). The way in which the TT structures, organizes and regulates interactions influences the student-teacher’s activity. These tools are coming from an experiential training, which is a process of transformation that results from reflection, re-elaboration and putting into words the experiences of life based on challenges encountered in unplanned events (Cavaco and Presse, 2022). This ‘guidance’ is supposed to foster him/her to become a reflective teacher capable of mobilizing theoretical knowledge acquired in the training institute (Amathieu et al., 2018). Thus, progressively, this monitoring during the school placement allows the student to construct his or her experience (Keiler et al., 2020).

However, the TT’s activity during the post-lesson interview is full of dilemmas that questions about the usefulness of this tool (Bertone et al., 2009) because of some undesirable effects (De Simone, 2021). During the interview, the TT plays several roles, including those of coach, expert, and evaluator, which sometimes causes identity tensions (Dejaegher et al., 2019). This plurality of roles can also present him/her with some dilemmas: should the student-teacher identify his strengths and weaknesses by himself? Should the TT give suggestions for improvement or, let the student-teacher to find them by himself/herself (Mieusset, 2017)? Should TT “help to teach” through “immersive practice,” or “help to learn to teach” by focusing on reflexive practice (Chaliès et al., 2009, p. 61)? Should TT provide standard and immediately applicable teaching skills (Méard and Durand, 2004), produce debates (Saujat, 2004), encourage the collective working dimension to cope with emotionally challenging situations (Descoeudres, 2021, 2023), or provide emotional support to student-teachers (Descoeudres and Hagin, 2021)?

Indeed, it seems that during post-lesson interviews, TTs support student-teacher emotionally (Mieusset, 2017), which sometimes leads them to hide their negative opinions about the student-teacher teaching (Bertone et al., 2009). Some TTs prefer to adopt to a role of guidance or to a role of critical friends (Mac Phail et al., 2021). They provide sometimes implicit recommendations which are linked to their proper past experiences and consist of suggesting professional skills, or even of asking student-teachers to conform themselves to the TT ways of teaching (Aspfors and Fransson, 2015). These different injunctions lead to tensions between what TTs want to achieve and what they in fact achieve. Where are the skills used from the TTT during the post-lesson interviews coming from? Are they coming from the CAS or from the past experiences lived when the TTT were themselves student-teachers? This study will attempt to answer two research questions concerning on the one hand the significant past experiences of the tutors (in training as students or currently in training during the CAS) and, on the other hand, the effects of the former on their current activity.

This study borrows a theoretical clinical and developmental framework. The clinical historical activity theory (CHAT) reflects on humans (Clot, 1999, 2008) in a growing perspective and exploits the notions from cultural historical psychology (Vygotski, 1960/2014; Leontiev, 1976). These psychologists assume that the developmental process is based on the internalization of cultural signs. For example, a subject operates to achieve goals and motives through the mediation of tools, mostly received from previous generations or previous experiences (Leontiev, 1976). These external cultural signs are first “learned” in a dissymmetrical situation (with an expert, a subject who masters this tool, in our case the lecturers of TTTs during the CAS). They are then “grafted” gradually in increasingly symmetrical situations (the TTTs try to set up the recommendations received during the CAS). Finally, they are mastered alone (after the CAS, they can act in autonomy as tutor), thus becoming tools of thinking and action for the development of one’s own activity.

To make possible this second stage of development, this internalization implies psychic debates taking place between various simultaneous and opposite options. Intrapsychic conflicts can also emerge during exchanges and discussions between various persons (Descoeudres, 2023). In relation to our research object, this theoretical framework used suggests that TTTs receive “cultural signs” during the CAS, during discussions with peers following the same CAS, and/or during professional discussions with novice or experienced colleagues. Then, they internalize these signs (tools) that can be used with the student-teachers during post-lesson interviews.

Considering emotions as the starting point of the subject’s development, Clot (2008) reminds us that the individual’s development is inseparable from their capacity to be affected by both negative emotions and positive ones. This confirms Vygotski’s transformational and developmental dimension of emotions. Clot (2008) postulates that emotions are situated between sense (motives and goals of the activity) and efficiency (tools, professional skills) and is at the origin of a development of the activity, initiated by the power to be affected (Descoeudres, 2019). The theoretical framework used postulates that the power to be affected (to feel emotions, positive or negative) in each situation, is a condition for a development one’s own activity (Bournel-Bosson, 2011). Vygotski adopts the concept of perezhivania, which means “unforgettable experience” or better Erlebnis in German, in connection with emotionally significant situations, even though the concept of perezhivania is not stabilized and has many meanings depending on the moment. Through this concept Vygotski refers to an unforgettable experience that contributes to the development of the subject (Veresov, 2014).

In relation to our study, we postulate that TTTs lived significant past experiences as student-teachers or as TTTs studying in the CAS, that each subject will mobilize as tools that will foster the development of the own activity. Perezhivania seems the pertinent concept to adopt linked to the theoretical framework that considers the development dependent of the power to be affected. We suppose that these past experiences lived in other environments influence the actual activity of TTTs. This clinical and developmental theoretical framework is relevant fort this study because it is aligned with the objectives, research questions and the method used. Moreover, the concept of perezhivania is coming from Vygotski that confirm a developmental dimension from the emotions and the activity is a central concept of the study.

The method used in this study is linked to the theoretical framework of the cultural historical activity theory (CHAT, Engeström, 1987; Clot, 2008) and aims to identify perezhivania which means unforgettable, because significant past experiences. It is a research-intervention with a double aim, heuristic, and developmental for the participants. The artifact used is the video.

Six volunteer teachers (four women, Ana, Brianna, Cindy and Dana, and two men, Matt and John,1 between 26 and 30 years old), working in six primary schools in the county of Vaud in Switzerland agreed to take part to this qualitative research. The six teachers were teaching in primary schools while also in a graduate program consisting of a two-year long Certificate of Advanced Studies (CAS) at the University of Teacher Education in Lausanne (Switzerland), with a focus on the function of student tutor. In parallel with this training, these six teachers supervised a student in school placement within their respective class.

This study involving human participants was approved by the Ethics Board of the University of Teacher Education in Lausanne. The research was conducted in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.2 The participants provided written informed consent for participation in the study and for the publication of any potentially identifying information included in the article.

The research contract for the six participants stipulated that each TTT filmed a post-lesson interview with his/her student. At the end of the interview, the TTT selected two video-excerpts of about 4 min (significant for him/her) to be analyzed. A researcher conducted a simple self-confrontation (SSC) interview with each TTT. Then the researcher conducted a crossed self-confrontation (CSC) interview with two TTTs and two video-excerpts for each. Finally, the protocol was supposed to end with a focus group interview with the researcher and all participants. This was planned for June 2020, but unfortunately could not take place due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

All SSC and CSC interviews were filmed and then manually transcribed. This paper is based on the verbatim from six SSC interviews and three CSC interviews. In total, 2,194 speaking turns were analyzed.

During the SSCs, the TTTs were asked to report their activity form the post-lesson interview. The researcher’s questions were intended to gain a better understanding of the reasons why the TTT acted in a certain way (or did not act in a certain way) to access to their “real activity” (Clot, 1999), mostly linked with past significant experiences. The researcher’s role was to access the TTT’s real activity (including the impeded part of their activity) by asking questions that provoked the emergence of intrapsychic conflicts, notably through the activity in other environments (e.g., as student-teachers, as TTT in the CAS). The controversy induced by the researcher promoted the evocation of past experiences during the post-lesson interview. This allowed the researcher to access to the impeded part of the activity of the six TTTs in the post-lesson interview situations.

The CSC interviews, involving two TTTs, took place after the SSC interview. On this occasion, each participant was asked to comment during the post-lesson interview about his or her personal activity in the presence of a peer, who would then question, debate, or contradict the activity of his or her colleague, principally about past significant experiences. From these exchanges and confrontations, interpsychic conflicts and “shared solutions” could emerge. The researcher’s role during these CSC interviews was to encourage these exchanges and debates such that the observation of a peer would produce greater knowledge in the viewer as well as greater activity from the respondent.

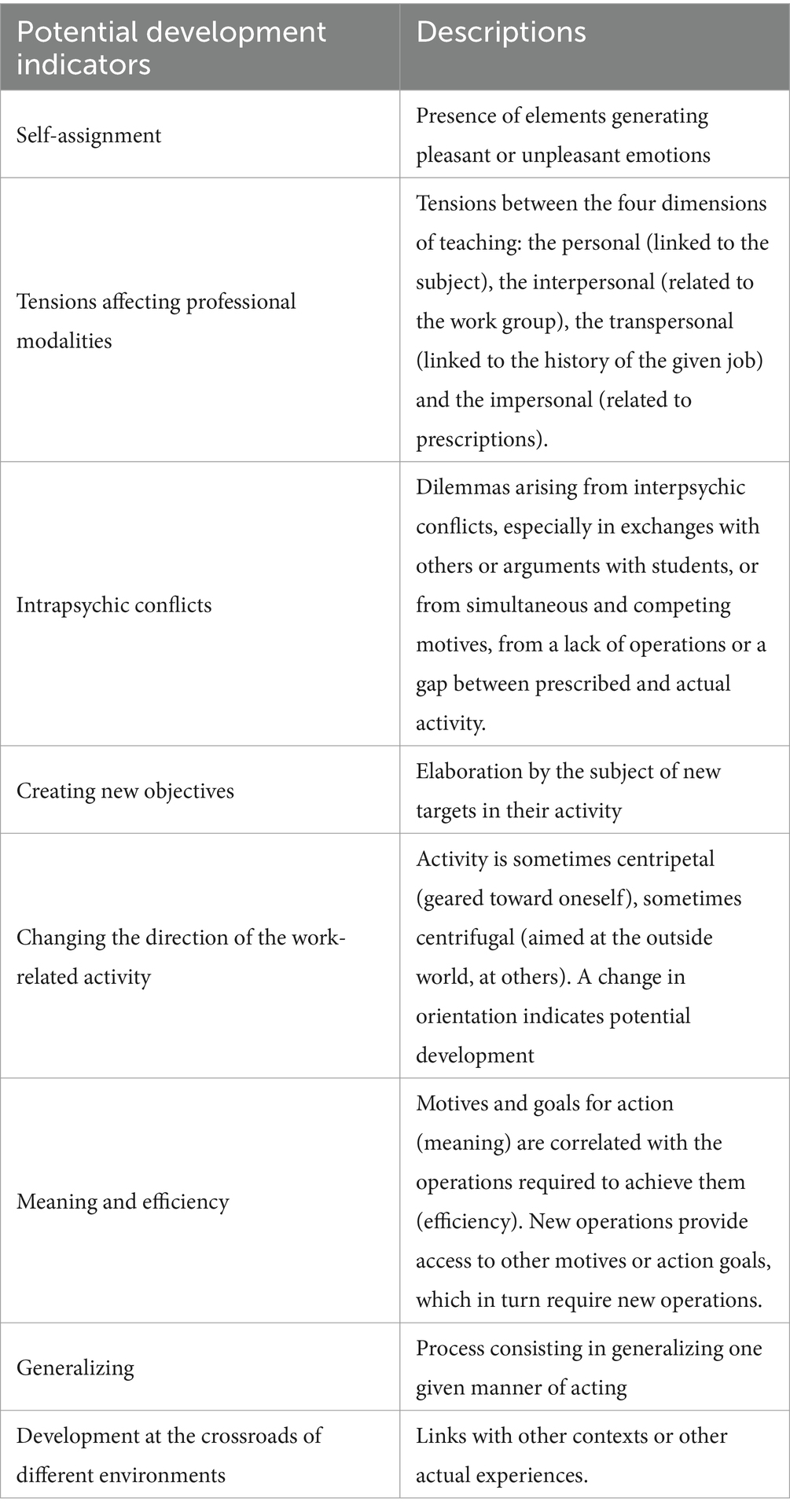

The data processing procedure was borrowed from the method of Bruno and Méard (2018), which provides a tool for coding the verbatim in line with the CHAT, the theoretical framework of this research. It consisted in identifying, in the 2,194 speaking turns, in a double-blind manner by three researchers, the developmental indicators of their activity (Table 1). Each of the 2,194 speaking turns were evaluated by the three researchers in a double-blind manner to identify the developmental indicators of their activity (Table 1): self-affectation, tensions between different instances of the profession, intrapsychic conflicts, self-oriented activity or object-oriented activity, development at the intersection of different environments, process of generalization and creation of new goals. In the verbatim, the perezhivania of TTTs were also identified. Most of these were representations of significant previous experiences as a student-teacher or as an actual TTT, linked to a development at the intersection of different environments. Our approach was to then connect the indicators of potential development to the unforgettable experiences of the TTT and to their effects on the TTT activity. The data was systematically grouped based on similarities through an inductive approach, with stories gradually classified. Following several successive stages conducted independently by two researchers in a double-blind manner, distinct categories emerged, facilitating the exploration of our research questions.

Table 1. Potential development indicators (Bruno and Méard, 2018).

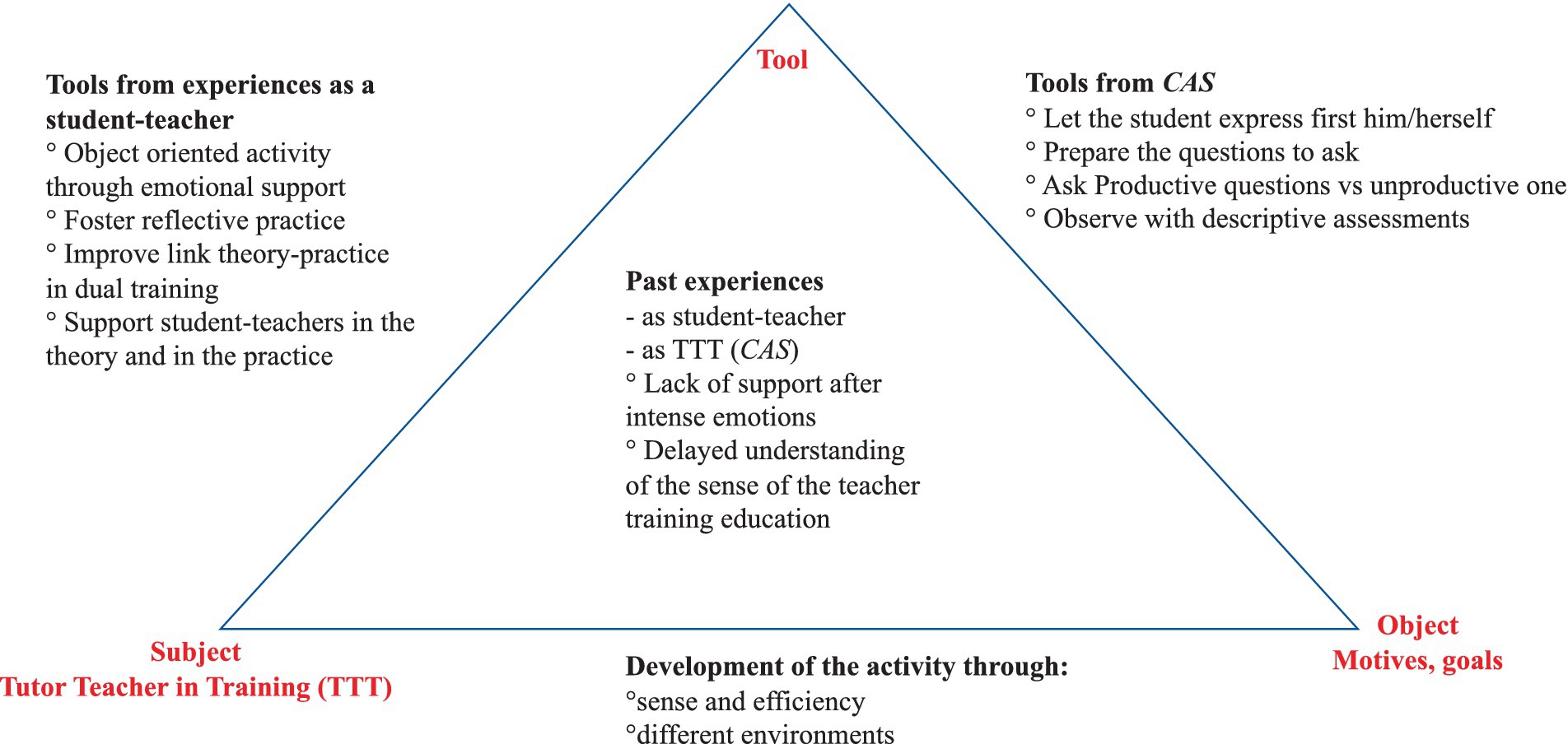

It appears that the situations experienced by TTT stem not only from their current training as tutors in the field, but also from their more or less distant student past, when they were themselves supervised by field tutors during their internship (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Results: the influence of past experiences on the actual activity of tutor teacher in training during post-lesson interviews.

In the first place, the results presented here will highlight the contributions of field tutor-training to the current activity of TTT, and the way in which these contributions operate. Then, the experiences accumulated as students will be presented and analyzed in relation to the current activity, through a few development indicators (Table 1). Finally, the results will attempt to answer the two research questions concerning on the one hand the significant past experiences of the tutors (in training as students or currently in training during the CAS) and, on the other hand, the effects of the former on their current activity.

During the interview conducted after a given teaching period, the tutor in training tries to apply what they were taught during training, namely by letting the trainee speak first to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the class they have just taught. They seem to be putting into practice what comes from another environment, i.e., their current place of training (CAS).

Because in some theoretical approaches we dealt with during training, we saw that it was important to enter the sphere of what may be problematic for the trainee by giving her the chance to talk about how she had experienced her lesson. That enabled us to identify what elements were her strengths, meaning what worked well! And also, what elements were weaknesses which could, in this case, generate problems to work on! (TP22, John).

By giving pride of place to the trainee during the post-lesson interview, such manner of proceeding is a much discussed and praised element of training, which thus comes from another environment (that of training), compared to that of their current activity.

I'd say it's a practice that I'm going to maintain! Because it allows me to go back to what may have been an issue for the student. And it allows me to work on the trainee's training objectives in a more concrete way! (John, TP40).

John generalizes this manner of proceeding by letting the trainees speak first, albeit with some intrapsychic conflicts linked to his questioning, because after all why should not he give his opinion first as a field tutor, before turning to that his trainees? His experience of the various implementation strategies demonstrates that

I notice the difference: when I give my opinion, we're going to work on my opinion, whereas here we're really starting with what the trainee has experienced and, as a result, it will certainly make more sense to her (TP26, John).

John feels that the trainee finds it more meaningful to work on what she has highlighted, rather than to focus on the elements that he would have pointed out first. We thus see a two-fold development in John’s activity: things make sense if the identification of the lesson’s strengths and weaknesses comes from the trainee. In terms of efficiency, John prefers to give the floor to the trainee first. This strategy is “learned” in CAS training, in an environment which is different from that of his usual professional life. Dana’s verbatim comments corroborate John’s in terms of the contributions made by training, in the sense that

It's a departure from what we've been taught in training, in the sense that it does not encourage students to tell us what we expect, or the things we'd like them to tell us, it teaches us to avoid influencing their reasoning to get to a point that is of interest to us, meaning there's really a moment when they're free to explore their own analysis and their vision of things (Dana, TP76).

It already allows me to assess how far the student has gone in their reflective process linked to practice, to see what they can identify as positive, what didn't work so well, and the questions they are asking themselves, rather than me turning up and immediately saying that was good, that wasn't so good (Dana, TP80).

Managing interviews in the best possible way to give maximum benefit for trainees is indeed addressed during tutor training, as shown by the previous results. To make post-lesson interviews as formative as possible, the use of observation tools, in particular descriptive scales, is also a component of the tutor-training CAS.

This is really something that is recommended in this CAS tutor teacher training. It's about focusing your observation, and then using descriptive scales is a good observation medium that should be used at such times! (TP36, John).

Summoning the impersonal modality of the job, John wavers between various degrees of constraint, first evoking a form of recommendation, then an obligation transferred from training into his own practice with his trainee. John seeks to be effective by pointing out in advance what he is going to observe and assess more specifically. Therefore, anticipating his own activity is induced both by the prescription and the training.

One of the avenues I had identified consisted in working on the questions I ask! And the objective behind those questions! In one of the seminars, we saw that we had to be careful about the kind of questions that yield results and those that don’t! I sometimes realize, during interviews with my trainees, that when I don’t get an answer from them, it is often because I have asked an unproductive question. So, apart from answering yes or no, they didn't really have a choice, and thus the trainees who have a sound knowledge base might try to find the answer that would prove satisfactory to me (John, TP84).

This account indicates several developments in John’s activity. Firstly, in terms of efficiency, through the anticipation of the questions to be asked and, by the same token, the identification of the objective to be met. Likewise, development is inherent to the different environments, since in the CAS of the field tutor, John highlights the types of productive and unproductive questions and the influence they have on the way the post-lesson interview goes. This enables him to generalize that the lack of response on the part of the trainee stems mainly from an unproductive question. Thus, the intersection of different environments enables him to generalize his practice.

To conclude on the ways field tutor training contributes to making post-lesson interviews more effective, Dana slightly qualifies her remarks by highlighting a discrepancy between the elements prescribed by CAS training and what she experiences with her student:

it's complicated to keep up with what we've learned in class, i.e., to really come up with objectives defined for the trainees so that we can work on those objectives with them in relation to the skills assessment process. In this type of interview which remains quite superficial, we don’t get the work of reflective feedback done, because it doesn't work with my student.. (Dana, TP101).

This excerpt deserves to be credited for mentioning that implementing the prescriptions passed on during training is not always effective, as they depend upon the context in which they are applied.

The objective of the results presented in the following section is to highlight on the one hand the lack of support experienced by the participants when they were students themselves, and the influence of such lack on their own current activity as field tutors. On the other hand, they provide an illustration of a delayed understanding of the contributions of basic training, as well as the links between theory and practice.

A lack of empathic support (or a lack in training in general) in the past seems to lead to a centrifugal activity on the part of field tutors, who act with their trainees as they would have liked to be treated as students. They first provide support in the case of emotionally negative situations in the classroom (disruptive student behavior in 1-2P):

it was difficult for me because she's a trainee I really like, it's true that she's with me a lot, three days a week. I feel that she's very much involved and she doesn't necessarily get the response that she'd like from the students, and I've also been through that myself and I didn’t get support at the time I went through that it as a trainee, so it affects me all the more (she gestures at her heart as she says this) when I see her in this situation, when she’s completely helpless and overwhelmed by what's going on.

Her aim is to take over during my maternity leave. We've looked into it with the HEP (teaching training institute), so that she can continue as a trainee, but now she's told me that it scares her, because she's going to be on her own, and she's afraid that the students' rowdy behavior will continue, and I can really, really relate because I find it so difficult when you feel you're losing your footing, so I was torn apart, I sympathize and at the same time my role as tutor consists in helping her improve.. (TP13, Ana).

The field tutor establishes a distinction between her roles, which consist mainly in helping her trainee learn the trade and improve, but also in supporting her and showing empathy in difficult moments. In the support interview, her activity as field tutor is geared toward the student, it is centrifugal, aimed neither toward herself nor the students:

So, the roles go together, but let's just say that at that time, I was more concerned with supporting her. I felt it was a priority for her to be able to get what she had on her chest off, and for her to feel that I was there to support her too (TP17, Ana).

When major difficulties arise during the lesson, the field tutor’s activity is directed toward the trainee (centrifugal), although the decision of whether to intervene or not during the lesson raises some ethical concerns:

I was afraid she'd lose all credibility.. well, I could see that tears were welling up in her eyes, that she was about to break down, that it was not stopping and since we still had ten minutes of class left, I said to myself, well, I know that if I separate these children, things will calm down (TP37, Ana).

Ana’s activity seems to be strongly influenced by her past as a student. Indeed, her work was rarely observed by her field tutor in her third year, even though she was having difficulties with the students and feels that she lacked support:

it's true that when I was in third year, that's when it happened. During the first semester I was on an A placement (under constant supervision) with a teacher, and this tutor had such a difficult class in terms of classroom management, she considered that for the students to "relate to" me, she had to get out of the classroom, so in fact she hardly ever observed me on the job. She'd go off to the teachers' room or wherever while I was teaching, and on several occasions, I found myself in situations when the students weren't listening to me, were laughing among themselves, so I didn't feel credible.

Brianna’s experiences as a student cause intrapsychic conflicts and lead to a development at the intersection of different environments for Brianna who had a bad experience with her field tutor at the time:

I try to be benevolent, to guide them, to pay attention to the way I give feedback and I realize in my feedback that sometimes I pick my words very carefully, I’m cautious, because I had a horrible tutor during my first year and I almost quit and I don't want to have that role either, so I still try to give directions, and to refrain from always assessing them, but rather to deliver guidance in a benevolent manner (TP97, Brianna).

Brianna points out the gaps in her training. During her internship, post-lesson interviews focused only what was visible, i.e., on classroom management, but not on the rest, and at no point was she trained to become a reflexive teacher. This affected her in a very negative way, as she felt undervalued.

I found that during the training courses, we tended to focus on what was visible, and they never really talked to me about 'why', so when I came into my classroom the first year, it had to be nice and pretty, but that was it. Then they asked me about everything else, and I was completely lost. I didn't feel like a teaching professional, I felt.. (TP53, Brianna).

The excerpt below highlights the shortcomings that Brianna identifies in hindsight. She is indeed keen to pass on to the trainee the necessity to weave together theory and practice, since she was deprived of it as a student.

We graduated from the HEP (teacher training school) six years ago, and I didn't have the opportunity to have a theory/practice experience as a trainee, and I'm so attached to it that I'm frustrated at not being able to do so, whereas the year before, when I had a first trainee, she was up for it. So of course, as you say, I was the one who put it into words, and she didn't know all that right away, but I brought it up and she was keen to learn, and then she said “well, it's great to see it in real life, because it makes more.. sense in theory”. I've got to learn to say to myself “but there won't always be trainees who are up to my standards and who are into my way of doing things” so “how am I going to manage that?” because in the end, you still must help them make progress, and I know that there are things that don't depend on me. The meaning she puts into her training.. I can have an influence on that, but there are also things.. it's up to her.. (ACC, TP215, Brianna).

Intrapsychic conflicts may be induced by this observation, as Brianna knows that some trainees are not like her, that some do not necessarily give meaning to their training. She must accept this. Her activity thus wavers between centripetal and centrifugal forces.

Ana, who manages to feel empathy for her trainee although she did not benefit from it in her student days, also had a difficult time in her professional training years.

I remember that I didn't have a very good experience during my time at the HEP in the sense that I had the impression that theory and practice belonged to two totally different worlds and then at certain times I was against the HEP because I felt that what I was being told wasn't at all what I was experiencing in my internship, and then that it was all nonsense, and then I didn't see the meaning of it all, and then I understood it later, and I think it's important to be by their side all the way, so that they get it… (ACC, TP232, Ana).

The comments above suggest a development at the intersection of different environments. Since Ana had a very bad experience in her basic training because what was taught in teacher training school seemed to differ from what she practiced in her internship, she wants to make sure this does not happen with her current trainees. She plans on being by their side so that they see meaning in it, and perhaps so that the place of training and the place of internship are not experienced as antinomic.

To conclude, our results highlight two distinct temporalities when it comes to past experiences: on the one hand, a proximate temporality, as inherent to field tutor training (CAS), and on the other, a clearly deferred temporality belonging to the remote era when our participants were themselves students. The results of the verbatim interviews reveal that the tutors in training are anxious to make up for the shortcomings they themselves suffered from when they were students, namely a lack of empathic support in emotionally-charged situations, a lack of supervision, an inappropriate choice of words in the post-lesson interview, a lack of meaning derived from theory, and an alternation between theory and practice that is not clear enough.

The present study which is based on a clinical historical activity analysis through self and crossed confrontation interviews, aimed to explore the influence of past experiences that TTT had as student-teachers and those they have now as TTT studying in the CAS. More specifically, the purposes of the study were to understand which emotionally significant situations they experienced in the past, influence their actual activity as TTT and which tools they are using from the CAS. The discussion of the results is shared in three parts. First, we will identify the necessity to train TT to this task, then we will discuss about the necessity to support emotionally the student-teachers at the entry of the profession. Moreover, the discussion will try to propose a way to incorporate past experiences into tutor training to enhance the effectiveness of tutors.

Finally, the discussion will highlight the importance to help student-teachers to foster the links between theory and practice especially through reflective practice during the post-lesson interviews.

First, the results highlight the importance of past experiences in the development process of TTT supervising student-teachers. During the CAS, TTT learned some tools that they invest, which is not the case in other contexts where TT have no training for this task (Derobertmasure et al., 2011). This training system seems to foster the TTT activity in the sense that TTT are considering various options of regulation that would probably not appear without training. Desbiens et al. (2009) argue that the better trained TT are, the better they can train the trainees themselves.

But it’s not only from the training that TTT put into practice tools, but also from emotionally significant situations lived as student-teachers many years before. As student-teacher during traineeship, they experienced emotional overload (Squires et al., 2022). The student-teacher activity in front of the class produces intense emotions related to dilemmas (Keller and Becker, 2020), unpredictability (Bullough, 2009), and the shock of reality (De Mauro and Jennings, 2016). The image of the whirlpool (Erb, 2002) or those from the rollercoaster (Lindqvist et al., 2022) can help illustrate this stage of one’s career, which is marked by emotionally significant situations during teaching, experienced by teachers at the beginning of their careers (Descoeudres et al., 2022). The entry into the teaching profession is identified in literature as a special, complex, and emotionally intense stage (Stewart and Jansky, 2022). Some teachers adopt turnover (Räsänen et al., 2020) or attrition as coping tactics. A way to avoid turnover or attrition in the early career seems to focus on the emotional dimension of becoming a teacher, in teacher education, through mentoring. In this sense, Waber et al. (2021) reveal the importance of interactions during the traineeship and the social support they need at the beginning of the career (Mukamurera et al., 2019). Waber et al. (2021) and Descoeudres (2023) emphasize the impact of this collective dimension not only through the colleagues but also through the TT. Our results show that the lack of support during emotional overload as student-teacher generate an opposite expertise form TT when his or her student suffers from emotionally significant situations. The time shared between TTT, and student-teachers seems to foster the development process of their activity. The lack of empathic support in the past seems to lead to a centrifugal activity on the part of TTT, who act with their student-teachers as they would have liked to be treated as students.

Incorporating past experiences into tutor training, particularly in the context of addressing potential negative experiences, is a crucial aspect that can significantly enhance the effectiveness of tutors through five different manners. (a) By acknowledging the impact of past experiences (Russell and Fuentealba, 2023): The first step is to recognize that tutors’ past experiences, both positive and negative, can significantly influence their approach to tutoring. By acknowledging this influence, training programs can better tailor their approaches to address any potential challenges stemming from past experiences. (b) By providing psychological support (Kangas-Dick and O’Shaughnessy, 2020): Training programs should incorporate elements of psychological support to help tutors process and cope with any negative experiences they may have encountered in the past. This can include techniques for managing stress, building resilience, and fostering a positive mindset. (c) By cultivating empathy and understanding (Jaber et al., 2018): Training should emphasize the importance of empathy and understanding toward students, recognizing that tutors may have faced similar challenges in their own academic journeys. By cultivating empathy, tutors can better connect with students and provide more effective support. (d) By promoting reflective practice (Fuentealba and Russell, 2023): Encouraging tutors to reflect on their own past experiences can be a valuable tool for personal growth and development. Reflective practice allows tutors to gain insights into how their past experiences may shape their interactions with students and enables them to identify areas for improvement. (e) By creating a supportive environment (Rusticus et al., 2023): Finally, training programs should strive to create a supportive environment where tutors feel comfortable discussing their past experiences and seeking guidance when needed. This can involve fostering a culture of open communication, providing mentorship opportunities, and offering ongoing support throughout the tutoring process. By incorporating these strategies into tutor training programs, educators can help tutors not only recognize the influence of their past experiences but also empower them to overcome any challenges they may encounter and provide more effective support to their students. In summary, teacher training plays a vital role in overcoming personal biases (Varol et al., 2023) and enhancing the effectiveness of post-lesson interviews by providing teachers with structured frameworks, promoting reflective practice, facilitating peer collaboration, emphasizing data-driven decision-making, aligning with professional standards, and fostering continuous learning and development.

Finally, beyond the emotional dimension, our results also show the importance of the delayed understanding of the sense of the teacher training education that induce a particular attention from TTT. In this way, TTT try to facilitate the link between the theory and the practice by supporting the student-teachers in the theory and in the practice in the hope the student-teachers see earlier the sense of the teacher training education. TTT foster the reflective practice (Talérien et al., 2021) by student-teacher during the post-lesson interviews and help them to try to make links between what they learn in the education institute and their activity in the classroom. One of the aims of teacher education is to help student-teachers to develop professional skills by articulating academic, theoretical, and practical knowledge (Gremion and Zinguinian, 2021). Our results show that this lack of education in the past takes an important place now in their TTT activity and that TTT do not want that their student-teacher experience the same lack of links between the theory and the practice. This deficit represents a challenge that TTT try to assume in front of their student-teachers to help them to better articulate theory and practice with the aim to become reflective teachers (Raucent et al., 2021).

Moreover, as TTT we argue that expertise in this profession is the result of the addition of “sedimented” and “episodic” past experiences (Rogalski and Leplat, 2011). “Sedimented” experiences are centered on the repetition of tasks while “episodic” experiences are centered on the singularity of the situations experienced, like for example emotionally significant situations (Descoeudres and Hagin, 2021) or perezhivania. What TT experienced as student-teacher (lack of support from TT during emotional overload) can be defined as an “episodic” or perezhivania who foster the own development, especially now when student-teachers lived emotionally significant situations, even if the process that permits this transfer is not really identified. In English, experience is at the same time Erlebnis (inner experience which results from a lived past experience) and Erfahrung (experience built by such experiences) (Romano, 2021), the challenge of training education is indeed, in this area of emotional competence (Erfahrung), and in that of supporting trainees after emotionally significant situations (Erlebnis). It seems that these past experiences (Erlebnis) allowed one’s to build his or her professional experience (Erfahrung) (Romano, 2021).

This study has several limitations and can open new research perspectives. Firstly, the results obtained in this study could be extended to tutor teachers form other school levels (secondary schools and high schools), not only primary school levels like in this study. In addition, a deeper investigation on the past experiences could be done in a narrative way for example, including additional variables such as emotional competences, age, school placement. Finally, future studies should maintain this longitudinal design that allows a deeply exploration in the professional development of TT. Furthermore, we could extend this study to TTs and not only TTTs and compare if the results are similar between an expert TT and a novice TT. And it’s always better to involve more participants in a study. Maybe this involvement could be promoted in a continue training for TT.

To conclude, our results highlight the importance of past experiences lived in other contexts on the actual activity of TTTs and reveal the importance of them to activate the link between theory and practice during teacher education. To help student-teachers better cope with the emotions lived during the lessons at the beginning of their careers, teacher education should introduce professional practice situations, because maybe not every TT can feel empathy after an emotionally significant situations lived by their trainee. A collective analysis could be performed regularly during the internship to ensure that these novice teachers do not feel alone. This will foster the professional development of their activity and maybe avoid drop out or attrition early in the career. Finally, the better trained the TT are, the better they will be able to train student-teachers. This could also be a benefit for a long and healthy career.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The study involving human participants was approved by the Ethics Board of the University of Teacher Education, Lausanne. The research was conducted in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided written informed consent for participation in the study and for the publication of any potentially identifying information included in the article.

MD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Open access funding by Haute école pédagogique du canton de Vaud (HEP Vaud).

The author thanks Méliné Zuinguinian, Annabelle Grandchamp, François Ottet, and Samyr Chajaï for their contribution to transcribing and analyzing the research data. The author would also like to thank Serge Weber and Jacques Méard for the time spent around this research, with all the team quoted above.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Amathieu, J., Escalié, G., Bertone, S., and Chaliès, S. (2018). Formation par alternance et satisfaction professionnelle des enseignants novices. Les Sciences de l'éducation - Pour l'Ère nouvelle 51, 87–116. doi: 10.3917/lsdle.514.0087

Amitai, M., and Van Houtte, M. (2022). Being pushed out of the career: former teachers' reasons for leaving the profession. Teach. Teach. Educ. 110:103540. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103540

Argyris, C., and Schön, D. A. (1974). Theory in practice: Increasing professional effectiveness Jossey-Bass.

Aspfors, J., and Fransson, G. (2015). Research on mentor education for mentors of newly qualified teachers: a qualitative meta-synthesis. Teach. Teach. Educ. 48, 75–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.02.004

Bertone, S., Chaliès, S., and Clot, Y. (2009). Contribution d'une théorie de l'action à la conceptualisation et à l'évaluation des pratiques réflexives dans les dispositifs de formation initiale des enseignants. Le travail humain 72, 105–125. doi: 10.3917/th.722.0105

Bournel-Bosson, M. (2011). “Rapports développementaux entre langage et activité” in Interpréter l’agir: un défi théorique. ed. D. B. Maggi (Paris: PUF)

Bruno, F., and Méard, J. (2018). Le traitement des données en clinique de l’activité: questions méthodologiques. Le Travail Humain 81, 35–60. doi: 10.3917/th.811.0035

Bullough, R. V. (2009). “Seeking eudaimonia: the emotions in learning to teach and to mentor” in Advances in teacher emotion research. eds. P. A. Schutz and M. S. Zembylas (Dordrecht: Springer)

Cavaco, C., and Presse, M. (2022). Formation expérientielle. D. A. Jorro éd. Dictionnaire des concepts de la professionnalisation Louvain-la-Neuve: De Boeck Supérieur.

Chaliès, S., Cartaut, S., Escalié, G., and Durand, M. (2009). L'utilité du tutorat pour de jeunes enseignants: la preuve par 20 ans d'expérience. Recherche et Formation 61, 85–129. doi: 10.4000/rechercheformation.534

De Mauro, A. A., and Jennings, P. A. (2016). Pre-service teachers’ efficacy beliefs and emotional states. Emot. Behav. Diffic. 21, 119–132. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2015.1120057

De Simone, S. (2021). Tensions et dilemmes inhérents aux postures de tutorat. Dans F. Mehran, M. Frenay, and E. Chachkine (dirs.), Les formations professionnelles. S'engager entre différents contextes d'apprentissage Presses universitaires de Louvain.

Dejaegher, C., Watelet, F., Depluvrez, Y., Noël, S., and Schillings, P. (2019). Conceptualisation de l’accompagnement des maitres de stage et analyse de ses effets chez les stagiaires. Activités 16, 1–28. doi: 10.4000/activites.4183

Derobertmasure, A., Dehon, A., and Demeuse, M. (2011). L’approche par problème: un outil pour former à la supervision des stages. Formation et pratiques d’enseignement en question 13, 203–224.

Desbiens, J.-F., Borges, C., and Spallanzani, C. (2009). Investir dans la formation des personnes enseignantes associées pour faire du stage en enseignement un instrument de développement professionnel. Éducation et francophonie 37, 6–25. doi: 10.7202/037650ar

Descoeudres, M. (2019). Le développement de l’activité des enseignants novices en éducation physique et sportive à l’épreuve de situations émotionnellement marquantes (Thèse de doctorat inédite). Université de Lausanne. Available at: https://serval.unil.ch/resource/serval:BIB_051F85FDE13D.P001/REF

Descoeudres, M. (2021). L’effet des interactions sur le développement de l’activité d’enseignants novices en EPS lors de situations émotionnellement marquantes. STAPS n° 134, 57–73. doi: 10.3917/sta.pr1.0024

Descoeudres, M. (2023). The collective dimension in the activity of physical education student-teachers to cope with emotionally significant situations. Educ. Sci. 13:437. doi: 10.3390/educsci13050437

Descoeudres, M., Cece, V., and Lentillon-Kaestner, V. (2022). The emotional significant negative events and wellbeing of student teachers during initial teacher training: the case of physical education. Front. Educ. 7:970971. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.970971

Descoeudres, M., and Hagin, V. (2021). Emotionally significant situations experienced by physical education teachers in training. Revista De Psicología Del Deporte (Journal of Sport Psychology) 30, 250–256.

Dewey, J. (1904). The relation of theory to practice in education. Dans C. McMurray (dir.), The third NSSE yearbook The University of Chicago Press.

Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by expanding: an activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Orienta-Konsulit.

Erb, C. S. (2002). The emotional whirlpool of beginning teachers’ work. Presented at the Colloque Canadian Society of Studies in Education, Toronto, Canada.

Fuentealba, J. R., and Russell, T. (2023). Encouraging reflective practice in the teacher education practicum: a dean’s early efforts. Front. Educ. 8. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1040104

Gremion, C., and Zinguinian, M. (2021). Introduction. Lorsque l’alternance vient soutenir la professionnalisation. Formation et pratiques d’enseignement en questions 27, 7–14.

Hagenauer, G., Hascher, T., and Volet, S. E. (2015). Teacher emotions in the classroom: Asso-ciations with students’ engagement, classroom discipline and the interpersonal teacher-student relationship. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 30, 385–403. doi: 10.1007/s10212-015-0250-0

Haute école pédagogique du canton de Vaud . (2021). Directive 03_22 Mandat de la praticienne formatrice ou du praticien formateur. Consulté le 13 juillet 2023 sur. Available at: https://www.hepl.ch/files/live/sites/files-site/files/comite-direction/directives/directive-03-22-mandat-prafo-2021-hep-vaud.pdf

Haute école pédagogique du canton de Vaud . (2022a). Évaluation du stage de 3e année. Échelles descriptives et commentaires. Année 2021–(2022).

Haute école pédagogique du canton de Vaud . (2022b). Suivi de stage. Informations et directives pour le stage professionnel en pratique accompagnée. 3e année (stage A). Année 2021–2022.

Haute école pédagogique du canton de Vaud . (2022c). Suivi de stage. Informations et directives pour le stage professionnel en pratique accompagnée. 3e année (stage B). Année 2021–2022.

Haute école pédagogique du canton de Vaud . (2004/2016). Formation des enseignantes et enseignants. Référentiel de compétences professionnelles. Available at: http://www.hepl.ch/files/live/sites/files-site/files/interfilieres/referentiel-competences-2016-hep-vaud.pdf.

Hong, J. Y. (2010). Pre-service and beginning teachers’ professional identity and its relation to dropping out the profession. Teach. Teach. Educ. 26, 1530–1543. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.06.003

Jaber, L. Z., Southerland, S., and Dake, F. (2018). Cultivating epistemic empathy in preservice teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 72, 13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2018.02.009

Kangas-Dick, K., and O’Shaughnessy, E. (2020). Interventions that promote resilience among teachers: a systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 8, 131–146. doi: 10.1080/21683603.2020.1734125

Keiler, S., Diotti, R., Hudon, K., and Ransom, J. C. (2020). The role of feedback in teacher mentoring: how coaches, peers, and students affect teacher change. Mentor. Tutor. Partnersh. Learn. 28, 126–155. doi: 10.1080/13611267.2020.1749345

Keller, M. M., and Becker, E. S. (2020). Teachers’ emotions and emotional authenticity: do they matter to students’ emotional responses in the classroom? Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 27, 404–422. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2020.1834380

Lindqvist, H., Weurlander, M., Wernerson, A., and Thornberg, R. (2022). The emotional journey of the beginning teacher: phases and coping strategies. Res. Pap. Educ. 38, 615–635. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2022.2065518

Mac Phail, A., Tannehill, D., and Ataman, R. (2021). The role of the critical friend in supporting and enhancing professional learning and development. Prof. Dev. Educ., 1–14. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2021.1879235

Méard, J., and Durand, M. (2004). “Masquer le savoir à des stagiaires qui réclament des recettes” in Les dilemmes des formateurs [Communication] (Colloque d’Ingrannes, France)

Mieusset, C. (2017). Les dilemmes du maître de stage D. A. Jorro, J.-M. KeteleDe, and F. Merhan (eds), Les apprentissages professionnels accompagnés De Boeck Supérieur.

Mukamurera, J., Lakhal, S., and Tardif, M. (2019). L’expérience difficile du travail enseignant et les besoins de soutien chez les enseignants débutants au Québec. Activités 16:3801. doi: 10.4000/activites.3801

Rajendran, N., Watt, H. M. G., and Richardson, P. W. (2020). Teacher burnout and turnover intent. Aust. Educ. Res. 47, 477–500. doi: 10.1007/s13384-019-00371-x

Räsänen, K., Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., Soini, T., and Väisänen, P. (2020). Why leave the teaching profession? A longitudinal approach to the prevalence and persistence of teacher turnover intentions. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 23, 837–859. doi: 10.1007/s11218-020-09567-x

Raucent, B., Verzat, C., Van Nieuwenhoven, C., and Jacqmot, C. (2021). Accompagner les étudiants: Rôles de l'enseignant, dispositifs et mises en oeuvre. De Boeck Supérieur.

Rogalski, J., and Leplat, J. (2011). L’expérience professionnelle: expériences sédimentées et expériences épisodiques. @ctivités 8, 5–31. doi: 10.4000/activites.2556

Russell, T., and Fuentealba, R. J. (2023). Self-study of teacher education practices: the complex challenges of learning from experience. Int. Encycl. Educ. 7, 458–468. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-818630-5.04053-7

Rusticus, S. A., Pashootan, T., and Mah, A. (2023). What are the key elements of a positive learning environment? Perspectives from students and faculty. Learn. Environ. Res. 26, 161–175. doi: 10.1007/s10984-022-09410-4

Saujat, F. (2004). Comment les enseignants débutants entrent dans le métier. Formation et pratiques d’enseignement en questions 1, 97–106.

Squires, V., Walker, K., and Spurr, S. (2022). Understanding self-perceptions of wellbeing and resilience of preservice teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 118:103828. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103828

Stewart, T. T., and Jansky, T. A. (2022). Novice teachers and embracing struggle: dialogue and reflection in professional development. Teach. Teach. Educ. Leadersh. Profess. Dev. 1:100002. doi: 10.1016/j.tatelp.2022.100002

Talérien, S. J., Chaliès, S., and Bertone, S. (2021). Generating professional development by supporting reflexivity in continuing education: a case study in kindergarten. Swiss J. Educ. Res. 43, 155–168. doi: 10.24452/sjer.43.1.12

Varol, Y. Z., Weiher, G. M., Wenzel, F. S. C., and Horz, H. (2023). Practicum in teacher education: the role of psychological detachment and supervisors’ feedback and reflection in student teachers’ well-being. Eur. J. Teach. Educ., 1–18. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2023.2201874

Veresov, N. (2014). “Emotions, perezhivanie et développement culturel: le projet inachevé de Lev Vygotski” in Sémiotique, culture et développement psychologique. eds. D. C. Moro and N. M. Mirza (Presses universitaires du Septentrion)

Vygotski, L. S. (1960/2014). Structure des fonctions psychiques supérieures. L. S. Vygotski Dans (dir.), Histoire du développement des fonctions psychiques supérieures. La Dispute.

Keywords: tutor teacher, post-lessons interviews, past experiences, self-confrontation interviews, professional development

Citation: Descoeudres M (2024) The influence of past experiences on the activity of tutor teachers in training. Front. Educ. 9:1330819. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1330819

Received: 31 October 2023; Accepted: 22 March 2024;

Published: 04 April 2024.

Edited by:

Dominik E. Froehlich, University of Vienna, AustriaReviewed by:

Oriane Petiot, Université de Bretagne Occidentale, FranceCopyright © 2024 Descoeudres. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Magali Descoeudres, TWFnYWxpLmRlc2NvZXVkcmVzQGhlcGwuY2g=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.