- 1Global Health and Innovation Lab, Faculty of Health Sciences, School of Health Studies, University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada

- 2Department of Health and Society, University of Toronto, Scarborough, ON, Canada

- 3Information and Instructional Technology Services, University of Toronto, Scarborough, ON, Canada

Storyline animations can be used as immersive academic tools to engage students’ learning experiences. Based on Kolb’s experiential learning theoretical framework, we produced and pilot-tested a new storyline animation encompassing the Sustainable Development Goals for undergraduate students in a health studies course and utilized student survey responses to gather their feedback. In this paper, we outline the design, implementation, and feedback from students, culminating in five key lessons. First, simplicity should be the goal. Second, segments should be short and accessible. Third, interposed questions, discussion forums, and varying storyline routes improve interactivity. Fourth, relatability, positionality, and empathy enhance learning and immersion. Fifth, supplementary materials can improve learning. Based on these findings, we offer recommendations across the five lessons to help educators overcome challenges and facilitate the implementation of similar pedagogical opportunities in their curricula.

1 Introduction

Students face numerous challenges when beginning their studies in global health pedagogy. First, the sheer breadth and complexity of global health issues may be overwhelming (Faerron Guzmán, 2022; Karakulak and Stadtler, 2022). Topics such as infectious diseases, healthcare disparities, and the social and structural determinants of health require a multidisciplinary approach to attain a deep understanding of the interconnectedness of these issues. This challenge can be addressed through animations, which can help students visualize these connections, as demonstrated in previous studies using animations as a pedagogical approach to learning (Ahmed et al., 2015; Liu and Elms, 2019).

Second, global health pedagogy often involves working in resource-limited settings or with marginalized communities that are unfamiliar to the students. For example, learning about varying cultural norms, different healthcare systems and their components, and diverse histories and political climates may be challenging. To effectively communicate this material, adapting these topics into a storyline may be beneficial for students from different backgrounds and may also enhance their empathy, positionality, and perspective, as shown in the results of our research and in previous studies (Ezezika and Jarrah, 2022; Petty et al., 2020).

Third, global health pedagogy may present specific ethical dilemmas, including the challenge of decolonizing global health and global health pedagogies, and leading students to critically evaluate their biases and values. For instance, complex issues, such as power imbalances and the distribution of limited resources between countries, are often discussed in global health. As a result, animations may help stimulate students to evaluate these complex dilemmas as they strive to be autonomous, well-informed individuals themselves.

Finally, global health pedagogy is constantly evolving, and new social arrangements, research, innovations, and technologies continue to push the boundaries of this field to ensure equitable treatment and access around the globe. To be informed about the latest global health priorities, students face the arduous task of staying up to date on the latest evidence-based interventions, best-practice guidelines, and evolving geopolitical context. Thus, having continuous storylines that can be amended as time passes allows educators to keep up with the latest knowledge and look at the past to see how we have evolved (like a virtual museum).

Importantly, discussing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through case studies presents a set of challenges. First, the SDGs encompass numerous interconnected and complex, and at times, contentious issues, ranging from poverty eradication to climate action. Incorporating these goals into specific case studies requires deliberately selecting and balancing relevant targets and indicators and weaving them into an engaging storyline. Capturing the multidimensional essence of the SDGs in case studies is also challenging. Second, the inspiration for case studies is often influenced by real-world scenarios, which in turn encompass many contextual factors. As such, not every potential storyline can be explored when attempting to bring the SDGs to life through case studies; therefore, the author(s) of a case study must attempt to capture and convey as many contextual factors as possible without bombarding the reader. Indeed, while the SDGs are far reaching, not every government agency, academic department, or private and public sector organization can be mentioned in a single case.

1.1 Purpose of the SDG storyline

Creating engaging and immersive experiences into storylines for the digital environment has been recognized as an educational learning tool within pedagogical practices, particularly in the realm of hybrid learning, which combines online and lecture-based learning methods (Hoban et al., 2013; Kickmeier-Rust et al., 2007; Yang, 2012). Animated storylines—the merging of audio messages with tailored visual cues and graphics (Liu and Elms, 2019)—have been shown to help make learning more memorable, and they have the potential to provide practical application to real world problems of the content learned (Novak, 2015; Rossiter, 2002).

Storyline animations in the health field have been implemented across multiple hybrid learning formats (Ahmed et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2019; Li et al., 2013). For example, in a pilot study conducted by Johnson et al. (2019), online animated simulations were used as an educational tool for healthcare professionals to help foster cultural competency in poverty and food insecurity. Likewise, animated graphics were used in an electronic game that consisted of a storyline involving 10 topics about mental health literacy, which was pilot-tested with undergraduate students to enhance mental health literacy for youth (Li et al., 2013).

We previously created and piloted a storyline animation module to a senior-level health studies class, in order to gain insight on how the module impacted their learning experience (Ezezika and Jarrah, 2022). The module contained two main parts—the animated storyline surrounding the SDGs and a quiz supplementing the animation. The animation was centered on a family living in a fictional rural village in a developing country. The lives of the family and others in the village were showcased to portray the typical challenges of living in a country ravaged by war and conflict, and the poor health systems accompanying this. The 17 SDGs were explored throughout the entirety of the storyline animation, along with how they relate to the fictional characters.

Findings from qualitative semi-structured interviews with students who viewed the storyline revealed three interconnected themes regarding the animation’s impact on their learning experiences. First, the animated storylines allowed students to improve their empathy toward individuals and communities facing global health challenges and recognize their positionality in relation to others living in different circumstances. Second, the storyline provided a broader perspective and helped situate the students’ learning in the context of other courses and programs. Finally, the storyline encouraged students to retain and apply the knowledge gained from the SDG storyline to other course projects and global health problems (Ezezika and Jarrah, 2022). However, the students pointed to concerns around engagement and the length of the animation. We, therefore, revised the SDG storyline animation to incorporate student feedback to make the animation more engaging. This included adding higher-quality graphics and breaking the animation into shorter segments. Moreover, the animated storyline was also adapted into a teaching case study, which includes the written storyline script, several graphics from the animated video, along with the supplemental questions (Ezezika et al., 2023a). The purpose of this case study was to increase accessibility accommodations and provide another mechanism to access this content at zero cost for learners. We also created a second storyline animation on the History of International Aid, which also reflected the feedback students provided on the first SDG storyline animation. Similarly, we also adapted the second storyline animation into a teaching case study, that includes the written storyline, embedded with graphics, and supplemental questions (Ezezika et al., 2023b), with the overall goal of increasing the accessibility to these storylines and making it available at zero cost for learners.

2 Pedagogical framework and principles

2.1 Four-dimensional framework

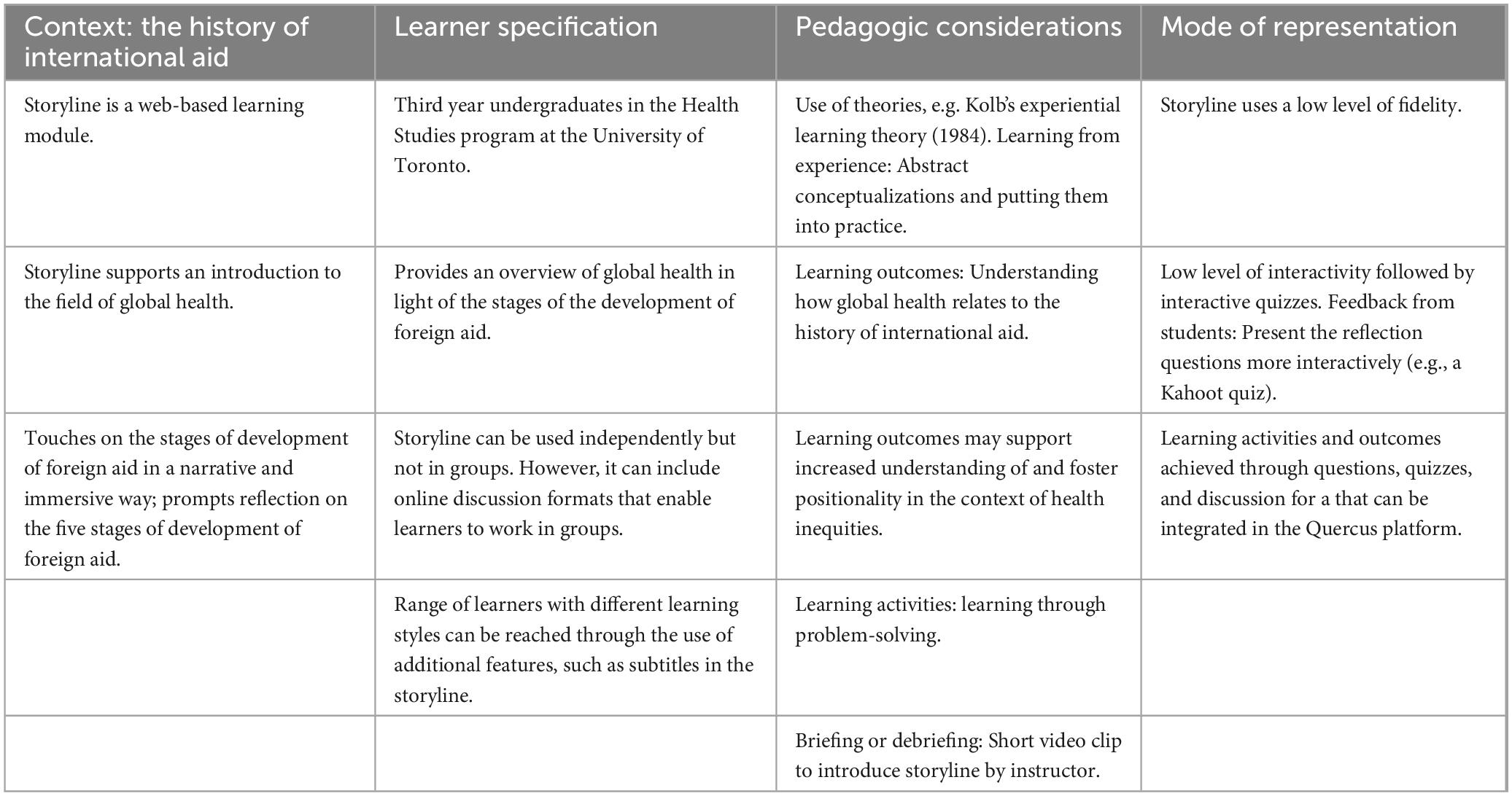

Through the process of examining the qualitative findings shared by students from the first SDG storyline animation, refining it, creating a second storyline animation on the History of International Aid, and adapting both into case studies to increase accessibility accommodations and make them available online at zero cost, we sought to reflect on the overall design, implementation, and critical lessons gleaned from these experiences. First, we used the Four-Dimensional Framework to evaluate the History of International Aid animation. We had previously evaluated and published the first SDG storyline animation using the same framework, but not for the second History of International Aid storyline animation. Second, we used Kolb’s theoretical framework to contextualize the usage of both storyline animations within a learning environment. Before this, we had not published literature that grounds the usage of our storyline animations to this theoretical framework and doing so provides the opportunity to contextualize the animated storylines with the experience of learning through a theoretical approach. Lastly, we share lessons learned from this design and implementation, with the overall goal of helping others interested in creating similar animated storylines to share across classrooms. Unlike the first SDG storyline animation, we did not conduct qualitative semi-structured interviews for the second history of international aid storyline animation. However, we utilized the Four-Dimensional Framework to evaluate the History of International Aid animation (Table 1).

Table 1. Evaluation of the history of international aid storyline using the four-dimensional framework.

The use of the four-dimensional framework supported the systematic assessment of the design, development, and delivery of this animated tool within a learning environment, ensuring that each stage of the process—conceptualization, implementation, and student engagement—was critically evaluated for effectiveness and impact on learning outcomes. Moreover, we previously applied this same framework to assess the first SDG storyline animation (Ezezika and Jarrah, 2022), where it helped to identify key factors that contributed to student comprehension, interaction with course materials, and the overall pedagogical value of using animated narratives to teach complex global health topics. This prior assessment provided valuable insights that informed the refinement and improvement of the current iteration of the animated tool.

2.2 Kolb’s experiential learning framework

Kolb’s experiential learning cycle explores how learning occurs when knowledge is created through grasping and transforming experience (Kolb, 1984). The framework has four stages: (1) concrete experience, (2) reflective observation, (3) abstract conceptualization, and (4) active experimentation. Grasping experience refers to assimilating information and is connected to stages 1 and 3, while transforming experience is about reflecting and implementing the information, and is associated with stages 2 and 4.

In concrete experiences, learners engage with an experience. In our SDG storyline, at this stage, the students immersed themselves in the animated storyline by observing and hearing about the imagined experiences of others. In the reflective observation stage, learners reflect on the experiences they encountered. In this case, students were prompted to reflect on their experiences with the animated storyline by being presented with reflection questions pertaining to the five modules. Next, in abstract conceptualization, learners form new ideas or adjust their current understanding based on reflections from the previous stage. Here, the students drew deductions by integrating previous knowledge and course concepts with the new learning experience. Finally, in active experimentation, learners apply the knowledge gained from the learning experience (Growth Engineering, 2023). Students were able to try out what they learned through discussions regarding the animated storyline, and they were also able to apply their new knowledge and skills to other projects in their course.

Reflection plays an essential role in reinforcing experiential learning as it facilitates students’ enjoyment of learning, retention of concepts, and application of knowledge to real-world problems and personal experiences. This enables students to integrate new knowledge with their existing understanding by connecting their learning to prior knowledge and establishing relationships.

Furthermore, reflection promotes metacognitive development by fostering self-awareness of students’ learning strategies and thinking processes. It allows them to identify their strengths and areas needing improvement. This self-awareness represents the first stage of reflection. The second stage, critical thinking, becomes evident as students consider their own positionality, analyze situations, examine assumptions, consider different perspectives, and evaluate their experiences. This critical thinking process enables students to apply new information to a given situation and gain a deeper understanding of complex issues.

Reflection also facilitates the transfer of learning from one context to another, as students reflect on past experiences and identify transferable skills and knowledge. Educators can then assess how students apply their acquired knowledge to real-life scenarios. This leads to the third stage of reflection, in which students gain insights and understanding of a concept within a specific situation (Ezezika and Johnston, 2022).

A similar course involving third- to fifth-year health studies students used Kolb’s experiential learning theoretical framework to assess the impact of an entrepreneurial pitch project on experiential learning through semi-structured interviews (Ezezika and Gong, 2021). During the concrete experiences stage, students interacted with external stakeholders, presented their projects to them, underwent cross-examination, and collaborated with their teammates. This stage provided an experience resembling a job interview and workplace environment, encouraging professionalism and communication skills. In the reflective observation stage, students focused on delivering their entrepreneurial pitch, engaged in critical self-reflection, and learned about their strengths. Moving to the abstract conceptualization stage, the students used the entrepreneurial pitch experience to apply their course knowledge in scaling interventions in the real world. They leveraged their existing knowledge to reflect on the practicality and limitations of their pitch. Finally, the students engaged in the active experimentation stage, which encompassed two key areas. First, they applied their knowledge of cultural norms to refine their innovation, seeking support through interviews with key stakeholders to identify potential cultural challenges. Second, they used a specific understanding of their target country to assess the potential success of their proposed solution (Ezezika and Gong, 2021).

3 Learning environment

The animated SDG storyline was developed for third-year undergraduate students at the University of Toronto, Scarborough Campus (UTSC), enrolled in the Global Health and Human Biology (HLTC26) course. The course is part of the Health Studies major program offered by the Department of Health and Society (DHS). The DHS offers two streams—Population Health (B.Sc.) and Health Policy (B.A.). The population health stream focuses on areas such as epidemiology, ageing, and the lifecycle, as well as various determinants of health, including biological and social factors. On the other hand, the health policy stream examines the impact of healthcare systems, public health policies, and governmental and civil responses to health-related societal issues. Students pursuing a Health Studies major often complement their studies with other programs, such as psychology, human biology, or mental health studies. These students are typically in their 20s and are actively working toward attaining a Bachelor of Science (BSc) or Honors Bachelor of Science (HBSc) degree.

3.1 SDG storyline

The storyline was first created as a written story centered on a single family in a low-resource setting and served to showcase the various family dynamics and SDG intricacies, including poverty, education, gender norms, and maternal health. From there, the storyline grew in an attempt to encompass more SDG topics, such as conflict and war, international aid, and varying health systems. The creation of the storyline can best be described as a “snowball effect,” in which a simple family dynamic was pealed out to ultimately unravel higher systemic community, national, and global topics.

The animated storyline introduces Dewroze, a resource-strained village whose inhabitants, including young Ada and her family, struggle amidst political unrest and violence. The story highlights the family’s profound socio-economic challenges due to school closures, health issues, poverty, and the war’s impact on the community. It concludes with Ada’s father criticizing government neglect and unequal fund distribution, encapsulating the residents’ struggles (Global Health Innovation Lab, 2023a).

Once the storyline and animation were created, they were carefully reviewed to generate comprehensive teaching notes, interactive questions, an answer key, and additional educational resources for educators and students to use. The teaching notes were carefully crafted to guide educators in effectively utilizing the animated storyline in their teaching. They include an overview of the key concepts, learning objectives, possible lesson plans, suggestions for classroom discussions, and possible additions or modifications. Interactive questions were developed to accompany each module and prompt critical thinking and reflection about situations presented in the storyline and potential solutions. For example, the following two questions are included in the first SDG animation, with additional online link resources students can access:

1. Ada’s inability to attend school (SDG 4) is closely related to the political unrest in Dewroze (SDG 16). Interactions between SDGs can be positively correlated (i.e., progress or limitations in one SDG are associated with progress or limitations in another SDG) or negatively correlated (i.e., progress in one SDG can hinder progress in another SDG).

a. How does a negative change in peace, justice and strong institutions impact the quality of education in Dewroze? (Hint: Feel free to refer to the SDGs here).1

b. How do you think Ada’s inability to attend school may impact her in the future?

c. In Dewroze, do you think the interaction between SDG 4 and SDG 16 is positively correlated or negatively correlated?

2. With his leg injury, seed prices going up, and recent droughts in the village, Ada’s father, Chido, has been having difficulty yielding enough crops, like other farmers in the village. As a result of this misfortune, imagine a developed country offers to provide Dewroze with labour and funds to sustain their agriculture, and promises to purchase their yield. How can the developed country use this action as a means to purposely keep a poor country underdeveloped, based on the dependency theory in international development? To read more about dependency theory, visit: https://www.proquest.com/openview/4039da2e926a00f581534e12d7421167/1?pqorigsite=gscholar&cbl=47510

An answer key was created to provide educators with guidance on the expected responses to the interactive questions and a tool to evaluate students’ understanding. Supplementary resources were also integrated throughout the interactive questions to enhance students’ learning experience and facilitate their understanding of key concepts. All resources associated with the modules were reviewed by team members for feedback, and meetings were scheduled as needed. This process led to simplifying the teaching notes, adding visuals, refining the questions and the answer key, updating the additional resources, and enhancing the format.

The process of developing teaching notes, interactive questions, an answer key, and additional educational resources for the History of International Aid storyline followed the same approach as that of the SDG storyline. However, the creation and animation of the History of International Aid storyline differed in several ways. Unlike the fictional case-study narrative in the first storyline, the History of International Aid focuses on presenting a walkthrough of significant events in the five main stages of foreign aid development. Thus, instead of telling a fictional story, it aimed to provide an informative account of the subject matter. Regarding animation style, the History of International Aid storyline deviated from the hand-drawn illustrations used in the first storyline (Figure 1). Instead, pre-existing images and pictures aligned with the module’s theme were employed and enhanced with effects such as zooming in and out (Global Health Innovation Lab, 2023b). The scope of this second animation revolved around examining the major public health inititaitves implemented throughout history, and is intended to provide a greater context of looking at public health through a historic lens. Specifically, there were 5 modules to this animation, each outlining major public health intitiatives during a specified time. Module 1 examined major initaitives that were implemented before World War 1, Module 2 centres on the 1940s to 1950s, Modeul 3 focusses on the 1960s to 1970s, Module 4 examines the 1980s to 1990s, and lastly, Module 5 brings us into The New Millenium. Occasionally, simple looped animations were incorporated to enhance visual engagement. These adaptations were made to effectively convey the historical information and engage learners in a different manner than the fictional SDG storyline.

Figure 1. Animation pictures (SDG Storyline). (A) Ada stays by her mother’s side and helps with cooking and cleaning, because the school closed due to the war (Global Health Innovation Lab, 2023a). (B) Ada’s mom, Zaineb, is feeling weak and tired due to anemia and skipping meals to leave enough food for her children and husband, who is the sole breadwinner (Global Health Innovation Lab, 2023a). (C) Rabby, the oldest child, helped their father with the farm until he was drafted by a rival gang to join the war at 14 years old (Global Health Innovation Lab, 2023a). (D) Zaineb used to make jewelry working at a local organization, and even though it gave her intense back pain, at least she was able to make some money to help Ada’s father (Global Health Innovation Lab, 2023a). (E) When Ada’s father, Chido, asks for her help at the farm due to his leg injury, Zaineb explains that Ada is doing her best to help around the house and look after her little sisters (Global Health Innovation Lab, 2023a).

3.2 Animation

After the fictional storyline was created, an animation was generated for students to watch and learn about the SDGs. The full animation runs approximately 15 minutes, with a 2-minute introduction. The graphic designer curated visual elements for the animated storyline by researching and collecting a diverse range of images that aligned with the storyline’s content and could serve as inspiration for the animation. The graphic designer also assembled a collection of images, drawings, sketches, photographs, and animations to showcase potential animation styles. The samples were shared with student members of the Global Health and Innovation Lab (GHIL), who voted on the best animation style. Once the preferred animation style was selected, a sample animation was crafted for one of the modules to serve as a prototype, and feedback from GHIL members was collected on how to enhance the animation. The sample animation underwent further polishing, with attention to details, timing, transitions, and visual appeal. When the first module was finalized, the remaining modules were animated.

3.3 Beta testing and student advisory

The studio recording and testing of the voiceover for the animated storyline was a collaborative process. Members of the GHIL were given the opportunity to voice a character in the animation. Volunteers were selected, and a meeting was arranged to assign characters, review the script, and conduct sample readings. The voiceover artists familiarized themselves with the script independently and practiced their parts, selecting the required tone, emotions, and delivery style. The team then gathered at the UTSC studio to set up the necessary audio recording equipment in a studio designed to minimize background noise and create an ideal recording environment. Each person was guided through the recording process with instructions on recording techniques, microphone positioning, volume control, line delivery, and character portrayal. After each attempt, valuable feedback was offered to help the voiceover artists improve their performances until the desired recordings were achieved. When the recordings were complete, they were fine tuned and refined, ensuring their synchronization with the animation and affirming that no rerecordings were needed (Global Health Innovation Lab, 2023a). The student advisory then reviewed the animations, helping to prepare them for implementation in a course.

4 Implementation and instructor’s guide

The animated storyline was successfully implemented (Global Health Innovation Lab, 2023a) and evaluated in a 3rd year undergraduate global health course at UTSC, with valuable feedback collected through a survey administered to the students. When asked about the aspects they enjoyed in the web-based learning module, students expressed a strong preference for the animated and visual nature of the storyline, highlighting its effectiveness in conveying content. The storyline itself and the accompanying voiceovers were also highly regarded, as they allowed students, particularly visual learners, to immerse themselves in the lives of Ada and her family. This approach helped students develop a deeper understanding of how the obstacles faced by the characters impacted their health and how these obstacles were embedded in a broader social, political and historical context.

Students indicated they preferred the use of the short videos (Global Health Innovation Lab, 2023a) over a single lengthy one because the shorter videos held their attention across the learning module. However, when asked about areas needing improvement, some suggested a slower speed for better absorption of the material. Students also expressed a desire for more interactive reflection questions to reinforce the main concepts covered. Additionally, they requested the inclusion of video transcripts to aid comprehension, although they did not point to specific areas of concern.

To further enhance the web-based learning module, students indicated their preference for the inclusion of solutions at the end of the videos. They believed this would reinforce their understanding of the material and provide insights into addressing the issues affecting the depicted population. Another suggestion was to include a conclusion video to summarize the key issues covered in the modules and connect them to the SDGs and global health. They also expressed a desire for interactive questions at the end of each video, possibly in the form of a Kahoot quiz, to encourage critical thinking before engaging in deeper reflection. Furthermore, there was a request to place more emphasis on the different social determinants of health. Finally, the students recommended adding captions to the videos to make them more accessible.

5 Discussion: lessons learned

5.1 Lesson 1: simplicity should be the goal

In creating animated storylines for global health pedagogy, simplicity should be the guiding principle. Given the breadth and complexity of global health issues, it is critical to make the plot straightforward, allowing students to engage with complex themes such as the social determinants of health or addressing SDG-related health challenges. In their interviews, the students expressed appreciation for simple plots and characters that allowed them to engage with the content without distractions.

Additionally, a simple storyline increases the chance for students to easily connect the story back to the course content. Specifically, a straightforward storyline provides the opportunity for students to explore the course content through an immersive lens without being too bombarded and confused. In turn, this will not only increase the chance that they will connect the story back to the course content, but it may also lead them to forge greater insights and genuine curiosity surrounding a particular topic, and in so doing, provide a point of entry into more complex scenarios and nuanced analysis.

A simple storyline deconstructs complex conceptual topics making them easier to grasp, analyze, and contemplate. It may be difficult to encapsulate all topics in a single storyline and keep it simple. A solution to this is to create multiple parts, each emphasizing a particular point or idea that together come to form a larger conceptual topic. Examples of such applications of simplicity in the health field include the use of online animated simulations as educational tools for healthcare professionals (Johnson et al., 2019) and an electronic game using animated graphics to create a storyline around 10 mental health topics for undergraduate students (Li et al., 2013). These approaches help distill complex global health issues into digestible formats.

Our storyline, set in the fictional village of Dewroze, introduced undergraduate health studies students to characters dealing with challenges such as war, conflict, and poor health systems. Importantly, the storyline was separated into five animation modules. This allowed the weaving of all 17 SDGs into the narrative, addressing complex topics such as poverty (SDG 1), maternal health (SDG 3), education (SDG 4), and gender norms (SDG 5) in a simplified manner. This approach also aligns with principles shared by Addo et al. (2022) regarding teaching SDGs through case studies. They argue that case studies simplify students’ exploration of complex interactions. Recognizing the complexity and interconnectedness of global issues, our storyline aims to engage students by simplifying these intricate subjects into smaller segments that are more digestible.

5.2 Lesson 2: short segments and greater accessibility

According to student feedback, it is advisable to break down longer storylines into shorter segments. For example, our first storyline module was 15 minutes long, providing students with a greater opportunity for reflection. This does not necessarily require changing the storyline, but rather providing points within the storylines where students can pause and reflect. Additionally, to enhance the accessibility of educational content for all students, special consideration should be given to the structure and delivery of animated storylines. The modules should be device-compatible, accompanied by transcripts, include captions, and offer students control over the speed of the videos, including the option to slow down for detailed comprehension.

Examples of accessible formats can be found in the experiential web-based program implemented by Bälter et al. (2022), which focuses on sustainable development, digital health literacy, digital learning, and child nutrition. This self-paced web-based program features digital materials, web-based video seminars, group assignments, module tests, and interactive elements. It exemplifies a move toward more accessible formats to accommodate learners’ schedules. This is especially important, as there were challenges in the program related to scheduling conflicts and poor web connectivity, which prompted solutions to provide flexibility, accommodations, extensions, and unlimited data packages. Moreover, the authors predicted student mastery to optimize learning outcomes by repeatedly refining the program, which was shown to reduce learning time by half compared to traditional courses, and by a quarter for newly developed programs, in a randomized control study (Bälter et al., 2022).

Finally, an approach to increase accessibility of the storyline is to create an interdisciplinary and creative learning environment in which students have the opportunity to interact with each other in a group setting as they watch the storyline. This can spark conversations that highlight the interconnectedness of students coming from various academic backgrounds (Alm et al., 2021). This recommendation is emphasized in the work of Alm et al. (2021), who enrolled students from three faculties in their poster project so they could push the boundaries of their discipline and address sustainability concerns. An interdisciplinary approach can also make the content accessible to students from various backgrounds. In relation to an animated storyline, the same approach can be taken in which students from various academic backgrounds watch the animated storyline and facilitate conversations to elicit various viewpoints and perspectives, which overall can help make the course content more accessible to everyone.

5.3 Lesson 3: interposed questions, discussion forums, and varying routes improve interactivity.

Incorporating application-based questions into the storyline can significantly enhance students’ learning experiences. Our study revealed that students greatly appreciated opportunities to actively apply the knowledge gained from the online module. In our first storyline, we presented interactive questions to the students after they viewed the animation. According to their interviews, the students would have preferred to have the questions interspersed throughout the storyline to improve participation and make the learning more active.

Feedback from students indicated a preference for questions presented in an interactive format, similar to Kahoot, an online game-based learning platform, at the end of each module. Through this, students may have the opportunity to think about the questions before diving into a deeper reflection of the video. Moreover, this approach may also stimulate dialogue and foster collaboration among students while achieving the course learning outcomes. This was shown by Bälter et al. (2022), who developed a web-based program for sustainable development with a focus on digital learning, digital health literacy, and child nutrition, and they integrated questions aligned with learning objectives to engage participants actively. However, this approach has seen limited adoption outside of North America, suggesting opportunities for further implementation and scalability (Bälter et al., 2022).

In addition to interspersing questions throughout the animations, future iterations may also consider incorporating an online portal where students can discuss their thoughts and reflections on the storyline content, which may aid their learning experience and foster collaboration in the classroom. For example, a discussion post can be posed to students, such as “What alternative route(s) could have been taken in the storyline?”, which would prompt students to explore their creativity while learning and engaging with other student posts and broaden their perspectives. Alternatively, students could be given greater control over the storyline. Specifically, a few students suggested incorporating a feature into the storyline that asks them to make choices or major decisions during the animation that affect the storyline, as this could provide a deeper immersive experience. This will create multiple routes for the storyline and provide the chance for students to discuss these various routes with each other, which may also facilitate a more engaging learning experience.

5.4 Lesson 4: relatability, positionality, and empathy enhance learning and immersion

Creating personable characters is crucial in an animated storyline. According to our study, students connected better with storylines that contained relatable characters, which improved their learning experience. They found it easier to empathize with the characters and remember the information being presented when they could connect with them. Weaving multiple perspectives into the storyline is also important, as it adds depth and context to the plot. For example, the students appreciated the inclusion of both institutional and personal perspectives in our storyline, as it highlighted certain issues within the fictional village of Dewroze.

Crafting strong characters with relatable personalities, motivations, and arcs increases the chances of evoking emotions from viewers. Engaging students through these immersive digital experiences, in which students can feel connected to the characters, is a recognized pedagogical practice, particularly in hybrid learning environments (Hoban et al., 2013). A compelling storyline makes learning more memorable for students (Novak, 2015; Rossiter, 2002).

Moreover, animated storylines offer students an opportunity to engage with complex topics—working in resource-limited and marginalized communities, addressing ethical dilemmas, and critically assessing their own biases and values. By presenting these topics in an immersive storyline, students can situate themselves in resource-limited settings and marginalized communities, helping them gain a better understanding of the issues at hand, especially if the topics are potentially uncomfortable for them. Thus, students are offered an opportunity to position themselves in these circumstances to grapple with and evaluate ethical dilemmas and biases, further deepening their learning experience. The surveys in our study revealed that the animated storyline improved students’ empathy and positionality. Our work aligns with the principles shared by Addo et al. (2022), including the importance of engaging students by bringing real-world stories to life to foster critical thinking and empathy.

5.5 Lesson 5: supplementary material can support learning

Ensuring reinforcement and understanding of the material presented in the storyline can be achieved in several ways. In our study, one student suggested providing solutions at the end of the module, which can help consolidate students’ knowledge and educate them further. Similarly, another student highlighted the value of a conclusion clip, which could be an effective tool for summarizing key issues presented in the modules and drawing correlations with other course content.

Supplementary material can also play a crucial role in enriching the learning experience. Students may find additional resources, such as external links to reputable websites, beneficial in reinforcing the information provided in the module. For instance, URLs linking to resources such as the World Health Organization or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention could provide more context and depth to topics being introduced for the first time. We adopted this technique in the interactive questions supplementing our storyline, and this approach can help students stay up to date with global trends.

Supplementary materials can also include collaborative learning. For example, in a project implemented by Alm et al. (2021), teachers acted as facilitators, supporting students in developing their problem-solving, critical thinking, and reasoning skills. Likewise, in a program by Bälter et al. (2022), high-performing participants were appointed as course ambassadors to encourage learning and foster engagement. Diverse learning opportunities were provided to students in the form of digital materials, web-based video seminars, group assignments, module tests, interactive elements, and a workshop. Participants maintained communication with each other and their teachers beyond the program period, which could open ongoing dialogue and support for learners to further solidify and expand their learning from the program. For future iterations, the researchers used participants’ feedback and click-data to improve learning, learning materials, and teaching. In keeping with these findings, generating similar collaborative learning environments may create long-lasting professional networks that grow over time, as both students and instructors navigate their way to becoming lifelong learners.

6 Conclusion

In applying Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theoretical Framework, the integration of an animated SDG storyline into a third-year undergraduate health studies course proved to be a highly effective pedagogical tool. By engaging students with the storyline and encouraging them to relate the content to both course material and real-world health scenarios, this approach fostered deeper critical thinking and reflection. The combination of visual storytelling, interactive elements, and accessible supplementary resources enhanced students’ ability to actively participate in their learning process, making complex topics, such as the SDGs and global health challenges, more comprehensible and relatable. Through this immersive and interactive experience, students were not merely passive recipients of information; they were active participants, constructing knowledge through the lens of real-world application, which is central to Kolb’s experiential learning model.

From the implementation of this animated SDG storyline, five key lessons were identified to optimize learning outcomes. First, simplicity is crucial, as it allows students to focus on core themes without becoming overwhelmed by unnecessary complexity. Second, dividing the content into short, accessible segments ensures that students can engage with the material in manageable portions, increasing retention and focus. Third, incorporating interspersed, application-based questions enhances interactivity, allowing students to actively process the content throughout the learning experience. Fourth, fostering positionality and empathy through relatable characters and scenarios deepens immersion and facilitates greater emotional engagement with the content. Finally, supplementary materials provide valuable opportunities for further exploration and reinforce key concepts. Overall, this integrative design helped students not only to understand global health issues but also to critically evaluate how these issues intersect with their own lives and the broader world, leading to more meaningful and enduring learning outcomes.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

OE: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. KF: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. MJ: Methodology, Resources, Writing – review and editing. UY: Data curation, Project administration, Software, Writing – original draft. MM: Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review and editing. SS: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The SDG Storyline project was funded by the Learning and Education Fund at the University of Toronto.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the members of the Global Health and Innovation Lab and other students, who supported the beta testing of the storyline and case study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Addo, R., Koers, G., and Timpson, W. M. (2022). Teaching sustainable development goals and social development: A case study teaching method. Soc. Work Educ. 41:1478–1488.

Ahmed, E., Alike, Q., and Keselman, A. (2015). The process of creating online animated videos to overcome literacy barriers in health information outreach. J. Consum. Health Int. 19, 184–199. doi: 10.1080/15398285.2015.1089395

Alm, K., Melén, M., and Aggestam-Pontoppidan, C. (2021). Advancing SDG competencies in higher education: Exploring an interdisciplinary pedagogical approach. Int. J. Sustain. Higher Educ. 22, 1450–1466. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-10-2020-0417

Bälter, K., Javan Abraham, F., Mutimukwe, C., Mugisha, R., Persson Osowski, C., and Bälter, O. (2022). A web-based program about sustainable development goals focusing on digital learning, digital health literacy, and nutrition for professional development in ethiopia and rwanda: Development of a pedagogical method. JMIR Formative Res. 6:e36585. doi: 10.2196/36585

Ezezika, O., Fatima, K., Yogalingam, U., Jarrah, M., and Sicchia, S. (2023a). An introduction to the sustainable developmental goals through the lens of dewroze. Health Stud. Publications.

Ezezika, O., Fatima, K., Yogalingam, U., Jarrah, M., and Sicchia, S. (2023b). History of international aid. Health Studies Publications.

Ezezika, O., and Gong, J. (2021). Experiential learning in the classroom: The impact of entrepreneurial pitches for global health pedagogy. Pedagogy Health Promot. 7, 118–126. doi: 10.1177/2373379920930723

Ezezika, O., and Jarrah, M. (2022). A case study on the impact of a web-based animated storyline module for global health pedagogy: Student perspectives. J. Educ. 202, 26–33. doi: 10.1177/0022057420943188

Ezezika, O., and Johnston, N. (2022). Development and implementation of a reflective writing assignment for undergraduate students in a large public health biology course—obidimma Ezezika, Nancy Johnston, 2023. Sage J. 9.

Faerron Guzmán, C. A. (2022). Complexity in global health– bridging theory and practice. Ann. Glob. Health 88:49. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3758

Global Health Innovation Lab, (2023a). Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Storyline Module. Available online at: https://globalhealthinnovationlab.org/sustainable-development-goals-sdg/ (accessed November 21, 2023).

Global Health Innovation Lab (2023b). History of International Aid. Available online at: https://globalhealthinnovationlab.org/history-of-international-aid/ (accessed November 21, 2023).

Growth Engineering (2023). Demystifying Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory: A Complete Guide—Growth Engineering. Available online at: https://www.growthengineering.co.uk/kolb-experiential-learning-theory/ (accessed June 2, 2023).

Hoban, G., Nielsen, W., and Shepherd, A. (2013). Explaining and communicating science using student-created blended media. Teach. Sci. 59, 32–35.

Johnson, K., Fleck, M., and Pantazes, T. (2019). “It’s the story”: Online animated simulation of cultural competence of poverty—A pilot study. Int. J. Allied Health Sci. Pract. 17.

Karakulak, Ö, and Stadtler, L. (2022). Working with complexity in the context of the United Nations sustainable development goals: A case study of global health partnerships. J. Bus. Ethics 180, 997–1018. doi: 10.1007/s10551-022-05196-w

Kickmeier-Rust, M. D., Peirce, N., Conlan, O., Schwarz, D., Verpoorten, D., and Albert, D. (2007). “Immersive digital games: The interfaces for next-generation E-learning?,” in Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Applications and Services, Vol. 4556, ed. C. Stephanidis (Berlin: Springer), 647–656.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Hoboken, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Li, T. M., Chau, M., Wong, P. W., Lai, E. S., and Yip, P. S. (2013). Evaluation of a web-based social network electronic game in enhancing mental health literacy for young people. J. Med. Int. Res. 15:e80. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2316

Liu, C., and Elms, P. (2019). *Animating student engagement: The impacts of cartoon instructional videos on learning experience. Res. Learn. Technol. 27, doi: 10.25304/rlt.v27.2124

Novak, E. (2015). A critical review of digital storyline-enhanced learning. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 63, 431–453. doi: 10.1007/s11423-015-9372-y

Petty, J., Jarvis, J., and Thomas, R. (2020). Exploring the impact of digital stories on empathic learning in neonatal nurse education. Nurse Educ. Pract. 48:102853. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102853

Keywords: experiential learning, educational animations, sustainable development goals, curriculum design, innovative teaching methods, public health

Citation: Ezezika O, Fatima K, Jarrah M, Yogalingam U, McKee M and Sicchia S (2024) Lessons on developing animated modules to introduce the sustainable development goals in undergraduate global health pedagogy. Front. Educ. 9:1307903. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1307903

Received: 05 October 2023; Accepted: 31 October 2024;

Published: 10 December 2024.

Edited by:

Alberto Paucar-Caceres, Manchester Metropolitan University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Silvia Quispe Prieto, Jorge Basadre Grohmann National University, PeruMelissa Franchini Cavalcanti Bandos, Centro Universitário Municipal De Franca (UNIFACEF), Brazil

Copyright © 2024 Ezezika, Fatima, Jarrah, Yogalingam, McKee and Sicchia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Obidimma Ezezika, b2V6ZXppa2FAdXdvLmNh

Obidimma Ezezika

Obidimma Ezezika Kishif Fatima

Kishif Fatima Mona Jarrah2

Mona Jarrah2 Mark McKee

Mark McKee