- 1Centro Regional de Inclusión e Innovación Social, Universidad Viña del Mar, Viña del Mar, Chile

- 2Facultad de Humanidades y Arte, Departamento de Idiomas Extranjeros, Universidad de Concepción, Concepción, Chile

Feedback remains a controversial topic for several reasons, the most relevant being the effectiveness and students' appraisal of the practice. This article explores second language learners' perceptions of feedback as a teaching and learning strategy. In second language teaching, it is necessary to know learners' previous knowledge and experiences regarding how they receive feedback, since this practice has an impact on the improvement of writing. To this end, in this research, an online questionnaire was distributed to 202 participants taking an English course to ask them about: types of feedback received, preferences regarding feedback, effectiveness of feedback and experiences with feedback. Analysis of their responses, quantitative and qualitative, shows that participants have preferences about how they expect feedback to be given, although these are not consistent with what theory suggests as effective. In addition, participants argue that their experience with feedback is related to a rather normative correction in which teachers focus on attending to microstructural aspects; therefore, students' view of textual quality is linked to normative processes. These aspects are important to address in the development of writing classes for second-language learners.

1 Introduction

Feedback is the information generated among various actors—teachers, peers, oneself—regarding academic performance (Hattie and Timperley, 2007). This dialogue among participants can occur through comments on the text, clarifications, constructive criticisms, reflections for self-assessment, corrections related to both positive and negative aspects to improve the text's quality, the advantages and disadvantages of the written work, and criteria associated with standards of textual coherence (Hattie and Clarke, 2018).

This latter aspect is also addressed by Boud and Molloy (2015), who value feedback for its guiding capacity, enabling the subject to improve their writing. Feedback is a pedagogical action that has an impact on students' learning, thus it is associated with multiple factors (Mandouit and Hattie, 2023). In this way, corrections can focus on the text's ideas, structural elements, or corrective feedback, the latter being studied in greater depth. Ellis (2009) and Sheen (2011) conceptualize feedback as a strategy associated with the term “corrective feedback,” meaning they relate it to purely grammatical aspects of language. Among corrective strategies, direct feedback, where the teacher explicitly provides the correct form or linguistic structure, and indirect feedback, where it is indicated in some way that an error has occurred without explicit mention, have predominated.

While the corrective approach has been dominant, Evans (2013) argues that feedback should be seen as a tool to help the student clarify their doubts and to enhance their learning rather than solely focusing on rules. Thus, this strategy serves not only to promote the quality of writing but also to promote learning. According to this, it is important to understand this corrective practice based on three fundamental aspects: clarifying expectations about learning, understanding the gap between the expected learning and that achieved by the students, and the actions needed to accomplish the expected learning outcomes (Hattie and Timperley, 2007).

Learning to write involves a series of processes and subprocesses associated with planning, textualization, and revision, in which skills and strategies are deployed to produce a written product. However, this practice is a complex task in which not only linguistic and contextual elements are articulated but also intrinsic variables such as motivation to write (Graham and Harris, 2018) and extrinsic variables related to learners' writing experiences. Studies in this area reveal that there is a relationship between motivation and writing performance (Graham et al., 2017), as well as the impact of subjects' practices with their teachers and the tasks they face. Furthermore, the study conducted by Kloss and Muñoz (2022) suggests that success in written production is influenced by the planning and execution of tasks. This highlights the importance of designing tasks with suitable topics for students and considering feedback as part of the writing process.

In this context, one of the issues observed in the writing processes in a foreign or second language is the lack of grammatical accuracy among learners. Specifically in the realm of writing, these errors or lack of precision can affect the intended message and consequently hinder communication between the writer and the reader. Thus, several authors (Ferris and Roberts, 2001; Khansir and Pakdel, 2018; Mendez and Spino, 2023) point out that grammatical errors, in some cases, can be distracting and stigmatizing, which underscores the need to support learners in improving their performance in this aspect.

As it has been stated, studies in corrective feedback generally focus on a quantitative approach, in which the effectiveness of various feedback strategies in improving learners' linguistic accuracy is determined. Therefore, there are not many studies that focus on qualitative aspects surrounding the use of these strategies. The importance of perception studies lies in understanding the cognitive and reflective processes that students undergo when receiving feedback and paying attention to it, as well as identifying the differences in processing when different corrective feedback strategies are used (Mao et al., 2024).

Studies regarding students' perceptions have shown that in general students view feedback positively, attributing it to heightened motivation and self-regulation (Marrs, 2016; Zumbrunn et al., 2013). However, Gamlem and Smith (2013) perceive it negatively due to demotivating aspects, such as critical comments. Understanding students' preferences in these strategies, as discussed by Birenbaum (2007), significantly influences the efficacy of feedback implementation, impacting broader aspects of their learning process, including self-esteem and learning interest. On the other hand, Rowe and Wood (2008) raises concerns about feedback quality and its alignment with student needs, underscoring the necessity of optimizing feedback practices for enhancing both writing abilities and motivation.

According to the above, perceptions about writing and revision vary based on students' practices and experiences. In this context, this paper aims to explore second-language learners' perceptions of feedback as a teaching and learning strategy in the context of higher education. This study contributes to the field of writing and feedback in Second Language Acquisition by providing a deeper understanding of students' perceptions regarding feedback strategies.

2 Method

The methodology of this research is qualitative since it involves an interpretative process that examines a problem associated with students' perceptions regarding feedback (Creswell and Plano, 2011). During the early months of 2023, we distributed an online questionnaire (in Spanish) to students enrolled in an English language course. It focused on gathering data about participants' perceptions of feedback and their academic experiences in this regard. The questionnaire was designed for the purpose of this research based on specialized literature on feedback. Subsequently, it was validated by two experts in the field of second languages, with an estimated Cohen's Kappa validity coefficient (k = 0.68), following the agreement index proposed by Landis and Koch (1977). The sample comprises a total of 202 native Spanish speakers, between 18 and 20 years old. They are currently in their second and third semesters at the university.

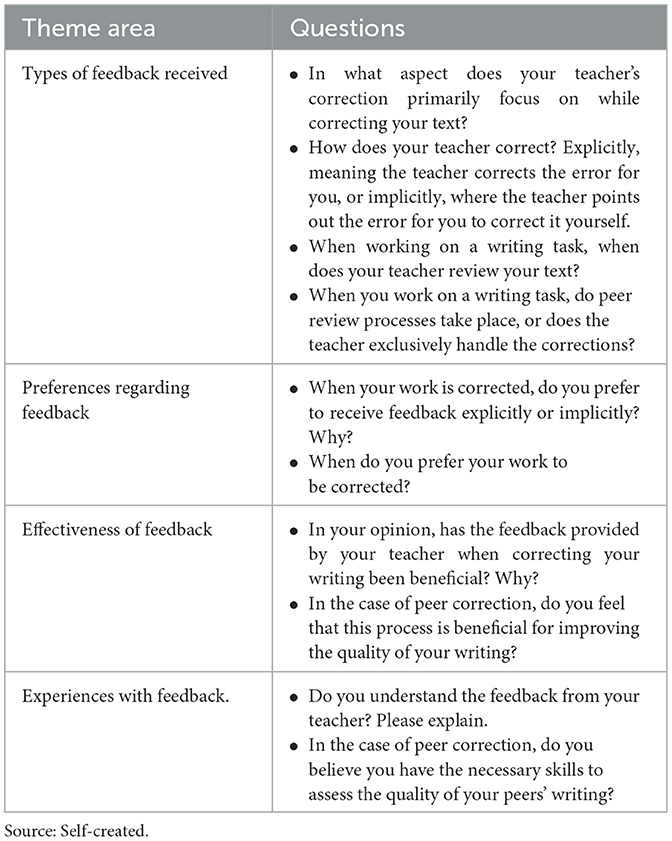

The data processing and analysis were carried out using a qualitative methodology. Students' responses were analyzed using predefined or deductive categories based on the concept of feedback and its characteristics (see Table 1). The presentation of data was done through percentages and thematic analysis. A deductive thematic analysis was applied to the responses to the open-ended questions in the survey, following the model proposed by Nowell et al. (2017) to systematize and increase the traceability and verification of the analysis.

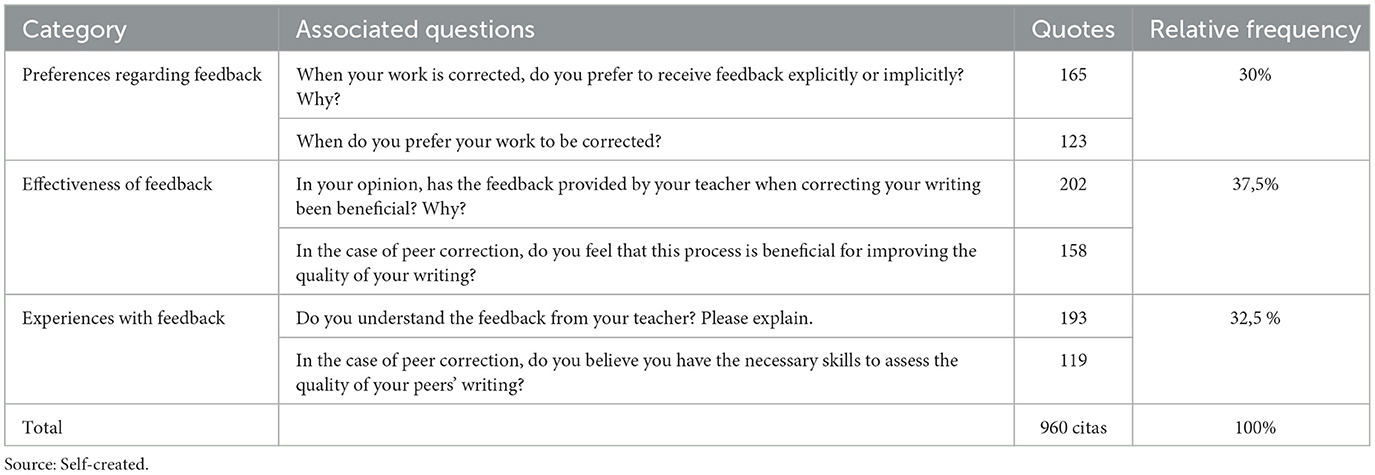

The responses were analyzed by identifying thematic categories through an iterative analysis system between the researchers and support staff. To ensure the reliability of the analysis, reliability procedures were applied through double coding and auditing of the entire analysis. After this analysis, a hermeneutic matrix (see Table 2) was constructed with the categories, questions and quotations associated with each one. For this purpose, the total number of quotations associated with the question and qualitative category were counted. For this study, the excerpts presented in the results section were translated into English.

3 Results

The results will present the findings organized according to the pre-established thematic areas. To achieve this, quantitative data will be presented first, followed by qualitative data when it corresponds.

3.1 Category 1. Types of feedback received

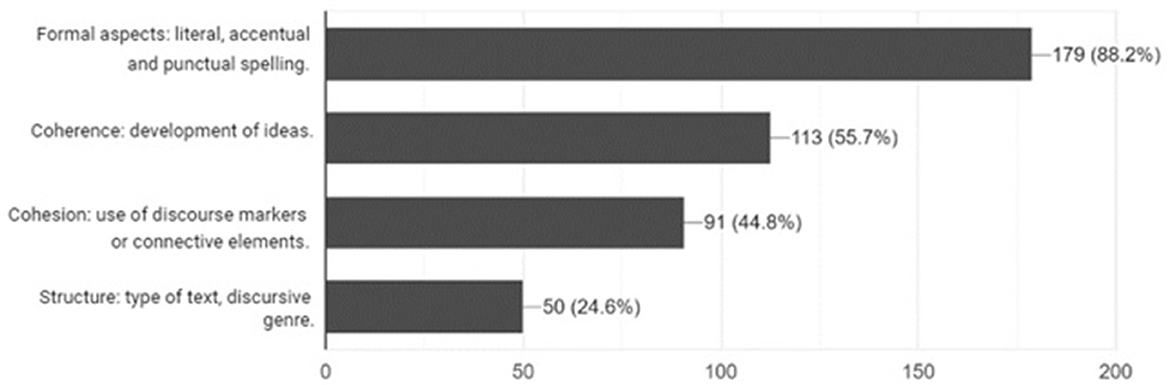

This category is explored through four questions. The first question relates to the key aspects of textual correction carried out by teachers (Figure 1). Of the students surveyed, 88.2% (n = 179) express that teachers predominantly correct formal elements like spelling and punctuation. Additionally, 55.7% (n = 133) indicate that teachers focus on idea development (coherence). Another 44.8% (n = 91) express that corrections are made at the cohesion level. Lastly, 24.6% (n = 50) of respondents state that the emphasis lies in the structure, including text type and discursive genre.

The second question explores the methods teachers use for corrections—implicit, explicit, or a combination of both. Out of the students surveyed, 11.8% (n = 24) mentioned implicit corrections, 31% (n = 63) opted for explicit corrections, while a majority, 57.15% (n = 116), stated that their teachers use a combination of these techniques.

The third question addresses when teachers provide feedback—during the process, at the end, or at both stages. Results indicate that 34% (n = 69) of the students reported receiving feedback solely at the end, after submitting their final version. Additionally, 6.4% (n = 13) mentioned receiving feedback during the process, while the majority, 59.6% (n = 121), indicated receiving feedback at both stages.

Lastly, the fourth question explores whether peer review occurs during writing tasks or if corrections are solely done by the teacher. Results show that 41.9% (n = 85) reported only teacher corrections, 2.5% (n = 4) mentioned exclusive peer corrections, and a majority of 55.7% (n = 113) reported both teacher and peer corrections.

3.2 Category 2. Preferences regarding feedback

This second category is explored through two questions. The first one focuses on student preferences for explicit, implicit, or combined feedback. Among the respondents, 53.7% (n = 109) prefer explicit feedback, 7.4% (n = 15) prefer implicit feedback, and 38.9% (n = 79) prefer a combination of both strategies.

Most students express a preference for explicit corrections. The theory is clear regarding the prevalence of indirect and metalinguistic feedback to improve written production (Hattie, 2013). However, we must consider that the latter implies some knowledge of the language to understand the feedback; otherwise, the learner cannot make the changes or reflect on their mistakes. Therefore, it is appropriate to tailor the type of feedback not only to the language proficiency but also to the type of error under consideration.

“It depends on the type of error, if it is an error of formal aspects, I prefer explicit correction, but if it is an error of coherence and cohesion, I prefer an implicit correction that makes me question why I wrote it that way and why it is wrong.” (s10)

“It depends on the type of text and the context in which it is requested. I believe that both types of corrections are necessary for learning.” (s17)

Some participants prefer a combination of direct and indirect corrections in a single assignment. They believe that certain errors require explicit teacher guidance for detection, as they may not identify them independently. However, they also appreciate the flexibility of implicit correction, as it allows them to make changes based on what they consider relevant.

“Explicitly, because sometimes, after editing and revising a text multiple times, errors tend to go unnoticed, and it's beneficial to point them out immediately. Implicitly, because this way I get a greater variety of suggestions and the freedom to correct certain ideas, structures, or segments within the text without being limited to a single option.” (s6)

“When it comes to errors that don't really have an explanation, just that 'it's that way,' as in the case of prepositions, I prefer explicit feedback. However, if it's due to a grammatical rule, something I could say, for example, 'Oh yes, I made a mistake, here we use 'ing' because there's a phrasal verb before it,' something I could detect myself, I would like implicit feedback.” (s65)

Some participants emphasize the reflective function of implicit feedback. Poorebrahim (2017) claims that “more explicit feedback is better for revising purposes while more implicit feedback is good for learning purposes” (p. 184). Furthermore, Mohammad and Rahman (2016) assert that, despite students' preferring explicit feedback, they acknowledge that implicit feedback fosters awareness, exploration, and autonomy.

“Implicit correction compels the student to thoroughly review the content and draw their own conclusions about the errors, which I believe is more beneficial for learning.”(s1)

“Implicitly is better for the student as it enhances their self-critique. On the other hand, the explicit form helps the student who cannot identify their errors to do so.” (s28)

It is important to highlight the teacher's role in providing feedback, since, according to students' comments, it is always the teacher who corrects and selects the strategy to be used. Nevertheless, Carless et al. (2011) argue that the feedback process should be dialogic, involving students, peers, and the teacher. In addition, feedback should foster learning development through agency, meaning that this process implies active student participation in task elaboration, encouraging reflective and strategic engagement within a self-regulated learning environment (Butler, 2002).

“Because if it lets me correct the error myself, I feel like I learn much more and can better understand why what I did is wrong.” (s18)

The second question concerns when students prefer their work to be corrected—during the process, at the end, or both. The responses show that 16.7% (n = 34) favor corrections during the process, 16.3% (n = 33) at the end, while the majority, 67% (n = 136), prefer corrections at both stages.

The results highlight the importance of adopting a process-oriented approach. This model, as described by Flower and Hayes (1980), comprises three stages: planning, involving decisions on content, objectives, and text organization; translation or textualization, encompassing content development, sentence construction, idea linkage, and syntactic and semantic organization; and revision, which entails text correction aligning with rules and intended ideas. According to this perspective, students value feedback not only upon completing their writing but also during the planning and textualization phases.

“I need to refine the work before submitting the final version, which allows me to achieve a higher grade. And in the end, because there's always room to include things that perhaps I didn't notice at that moment. It's a lengthy process in the end.” (s90)

“During the process, I can receive help in organizing my ideas and expressing them in the best, most coherent way. I can seek clarification on spelling or similar issues. After submitting the work, I review the final correction and realize that there are always things to improve, so I gather the comments and corrections.” (s45)

To make this approach beneficial for writing quality, students must allocate time to the writing process rather than solely perceiving it as a finished product. Otherwise, there won't be a process of reflection or self-evaluation by the writer.

“I don't usually ask for help with drafts, mostly because I tend to do my assignments at the last minute.” (s6)

3.3 Category 3. Effectiveness of feedback

In the third category, covered by two questions, the first one explores the usefulness of teacher feedback. An overwhelming 89.7% of students (n = 182) find the feedback effective, while 10.3% (n = 21) consider it ineffective.

Students confirm that teacher feedback is effective and conducive to learning. Boud and Molloy (2013) discuss the effectiveness of different strategies and advocate for constructivist feedback that involves active student engagement in the process.

“The corrections made by my teacher have allowed me to recognize my most frequent mistakes, which I try to correct or practice with a better understanding of my strengths and weaknesses.” (s26)

The second question explores students' perception of peer correction and its impact on their writing quality. Among those surveyed, 112 (55.2%) find this strategy beneficial, while 29 (14.3%) disagree. Additionally, 62 students (30.5%) reported no experience with peer correction.

Students highly value feedback, viewing it as essential for improving their writing quality. They also recognize that peers can identify aspects that writers may overlook due to their closeness to the text. Lundstrom and Baker (2009) support this perspective, emphasizing the benefits of peer review for both feedback providers and recipients.

“My peers see things that I don't because I am too involved in the text.” (s2)

“It is easier to spot mistakes in our classmates' work, even if they're the same as yours. So next time, you look more closely at your writing or review it as if it weren't your own work.” (s6)

A few students express dissatisfaction or skepticism regarding peer feedback because they perceive their peers as having similar knowledge levels. As a result, they prefer teachers' corrections (Li, 2009). Jensen and Jensen (2011) research highlights potential challenges with peer review, including students struggling to provide feedback due to their lack of expertise. Therefore, it's crucial to teach students how to give feedback to their peers and encourage this practice in the classroom (Hattie, 2013).

“Peer correction can help a bit in identifying errors or 'things that don't sound right,' but I don't recommend it. My peers can make the same or even more mistakes than me, so I don't trust their judgment.” (s4)

“The quality of feedback, especially in L2 texts, is not adequate as it varies depending on the language proficiency of all my peers. I try my best to provide feedback that encompasses not only the coherent development of ideas but also the use of vocabulary, collocations, verbs, and so on. However, I cannot claim to have been fortunate enough to receive a type of feedback that truly improves my texts, except from teachers.” (s7)

Interestingly, a significant number of students mention the absence of peer correction. This situation is complex as peer tutoring not only provides immediate benefits but also extends to future writing tasks (Boillos, 2021). Peer feedback is seen as a practice that strengthens peer relationships and fosters a positive atmosphere that promotes trust among students.

“I have no interest in that”. (s8)

“There is no peer correction”. (s23)

3.4 Category 4. Experiences with feedback

In the fourth category, consisting of two questions, the first one assesses students' comprehension of teacher feedback. A vast majority, 89.7% (n = 182), confirm understanding the feedback, while 10.3% (n = 21) admit to not comprehending it.

Most students report understanding the feedback, regardless of the teacher's approach. They state that direct feedback requires less cognitive effort, whereas indirect comments provide room for deeper thinking and self-evaluation.

“As they are explicit, there is not much to ask or not understand.” (s1).

“When I know where the error is, I can understand it. The teachers usually point to a specific error and why it's incorrect. Sometimes they provide options for correction, and other times, they just indicate what the error is about.” (s4)

The second question assesses students' confidence in evaluating their peers' writing. Out of the respondents, 53.6% (n = 98) feel equipped for this task, while 46.4% (n = 85) admit to lacking the necessary skills. The results show that a significant group of students feel unsure about giving feedback to their peers.

“I simply don't believe I'm the one to correct since I am also a student, and more likely to make mistakes.” (s35)

“I have too many doubts about my skills and abilities, so I wouldn't feel comfortable making corrections.” (s44)

“I don't think I have the complete ability to evaluate my peers, but I think we can complement each other and improve together.” (s191)

4 Discussion and conclusion

The analysis of the responses obtained in the questionnaire reveals a positive perception from the students regarding feedback. They value all types of feedback, with 53.7% preferring direct feedback over indirect feedback, as they require teachers or peers to explicitly point out their errors. However, a few students acknowledge the benefits of indirect feedback for promoting reflection on their mistakes (Kloss and Ferreira, 2019). These learner preferences for explicit correction (Mohammad and Rahman, 2016) contrast with feedback theory and empirical studies advocating for the use of indirect and metalinguistic feedback due to its reflective potential, particularly in enhancing grammatical accuracy (Poorebrahim, 2017).

Regarding the effectiveness of feedback, students argue that it helps them improve their texts, especially in the grammatical dimension, and also serves as a learning mechanism (Carless and Bould, 2018). Nevertheless, they believe that the effectiveness of feedback is contingent on the type of mistake and the timing of revision. Concerning revision, students tend to value teacher feedback (Li, 2009), while expressing skepticism toward peer feedback (Jahbel et al., 2020). This perspective reflects a lack of self-regulation, with students relying heavily on teachers for review and correction (Kloss and Muñoz, 2022).

About feedback as a learning mechanism (Boud and Molloy, 2015; Mandouit and Hattie, 2023), our study shows that students perceive it primarily as an external input provided by teachers (Nieminen and Carless, 2022), playing a peripheral role in their learning process. It is often seen as an oral or written mechanism associated more with the product than the process of learning.

Regarding the lack of grammatical accuracy experienced by second language learners and the role they assign to feedback, it is pertinent to note that students perceive teacher's feedback as effective, emphasizing its role in improving their writing skills. They also associate understanding the feedback provided by the teacher with its effectiveness in reducing grammatical errors (Kloss and Quintanilla, 2023).

Despite these nuances, most study participants have a favorable view of feedback, considering it a valuable element for language learning. This positive view fosters a dialogical relationship between teachers and students, serving as a model for learners to provide feedback to their peers and engage in peer correction (Hattie and Timperley, 2007).

While the focus of the study is to understand students' experiences regarding feedback, it would be interesting to conduct a mixed-methods study that allows correlating the effect of feedback on the quality of the produced texts and students' views of feedback.

Based on the research objective, which was to explore second language learners' perceptions of feedback as a teaching and learning strategy in the context of higher education, several areas for improvement in teacher's feedback practices emerged. These include enhancing training in correction to promote self-revision and peer correction, and developing didactic proposals that include diverse strategies and types of feedback, considering both what is informed by the literature and students' preferences, understanding the complexity of feedback and the impact it has on language learning.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

AQ: Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo, Chile. Proyecto Fondecyt de Iniciación 11240175.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Birenbaum, M. (2007). Assessment and instruction preferences and their relationship with test anxiety and learning strategies. High. Educ. 53, 749–768. doi: 10.1007/s10734-005-4843-4

Boillos, M. (2021). Incidencia de la revisión por pares en la construcción de textos académicos a nivel universitario. Delta 37, 1–21. doi: 10.1590/1678-460x202153017

Boud, D., and Molloy, E. (2013). Rethinking models of feedback for learning: the challenge of design. Assessm. Evaluat. High. Educ. 38, 698–712. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2012.691462

Boud, D., and Molloy, E. (2015). El feedback en educación superior y profesional. Comprenderlo y hacerlo bien. Madrid: Narcea.

Butler, D. (2002). Individualizing instruction in self-regulated learning. Theory Pract. 41, 81–92. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip4102_4

Carless, D., and Bould, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: enabling uptake of feedback. Assessm. Evaluat. High. Educ. 43, 1315–1325. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

Carless, D., Salter, D., Yang, M., and Lam, J. (2011). Developing sustainable feedback practices. Stud. Higher Educ. 36, 395–407. doi: 10.1080/03075071003642449

Creswell, J., and Plano, C. (2011). El diseño y la realización de la investigación de métodos mixtos. Thousand Oaks, CA: Salvia (2011).

Ellis, R. (2009). A typology of written corrective feedback types. ELT J. 63, 97–107. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccn023

Evans, C. (2013). Making sense of assessment feedback in higher education. Rev. Educ. Res. 83, 70–120. doi: 10.3102/0034654312474350

Ferris, D., and Roberts, B. (2001). Error feedback in the L2 writing classes: how explicit does it need to be? J. Second Lang. Writ. 10, 161–184. doi: 10.1016/S1060-3743(01)00039-X

Flower, L, and Hayes, J. (1980). A cognitive process theory of writing. College Compos. Commun. 32, 365–387. doi: 10.58680/ccc198115885

Gamlem, S. M., and Smith, K. (2013). Student perceptions of classroom feedback. Assessm. Educ.: Princ. Policy Pract. 20, 150–169. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2012.749212

Graham, S., Courtney, L., Marinis, T., and Tonkyn, A. (2017). Early language learning: the impact of teaching and teacher factors. Lang. Learn. 67, 922–958. doi: 10.1111/lang.12251

Graham, S., and Harris, K. (2018). An examination of the design principles underlying a self-regulated strategy development study based on the writers in community model. J. Writ. Res. 10, 139–187. doi: 10.17239/jowr-2018.10.02.02

Hattie, J. (2013). “The power of feedback in school settings,” in eds. R. Sutton Feedback: The Handbook of Criticism, Praise, and Advice. Lausanne: Peter Lang.

Hattie, J., and Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 77, 81–112. doi: 10.3102/003465430298487

Jahbel, K., Latief, M., Cahyono, M., and Abdalla, S. (2020). Exploring university students' preferences towards written corrective feedback in EFL context in Libya. Univer. J. Educ. Res. 8, 7775–7782. doi: 10.13189/ujer.2020.082565

Jensen, T., and Jensen, G. (2011). “Engaging students in the peer–feedback process improved peer-feedback on text through the conceptualization of board games,” in Proceedings of ICERI2011 Conference, Madrid, Spain.

Khansir, A. A., and Pakdel, F. (2018). Place of error correction in English language teaching. Educ. Proc. 7, 189–199. doi: 10.22521/edupij.2018.73.3

Kloss, S., and Ferreira, A. (2019). La escritura de crónicas periodísticas informativas: una propuesta de avance desde el feedback correctivo escrito. Revista Onomázein 46, 161–185. doi: 10.7764/onomazein.46.02

Kloss, S., and Muñoz, B. (2022). Escritura en educación superior: hacia una propuesta de producción escrita para enseñar en la disciplina. Revista Brasileira de Lingüística Aplicada 22, 754–773. doi: 10.1590/1984-6398202217944

Kloss, S., and Quintanilla, A. (2023). Think aloud protocols: a technique to assess the understanding of feedback. Formación universitaria 16, 1–12. doi: 10.4067/S0718-50062023000600001

Landis, J. R., and Koch, G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33, 159–174. doi: 10.2307/2529310

Li, M. (2009). Adopting varied feedback modes in the EFL writing class. US China For. Lang. 7, 60–63.

Lundstrom, K., and Baker, W. (2009). To give is better than to receive: the benefits of reviewing to the reviewer. J. Second Lang. Writing 18, 30–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2008.06.002

Mandouit, L., and Hattie, J. (2023). Revisiting “The power of feedback” from the perspective of the learner. Learn. Instruct. 84, 101718. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2022.101718

Mao, Z., Lee, I., and Li, S. (2024). Written corrective feedback in second language writing: a synthesis of naturalistic classroom studies. Lang. Teach. 1–29. doi: 10.1017/S0261444823000393

Marrs, S. (2016). Development of the Students' Perceptions of Writing Feedback Scale (Unpublished Doctoral's Dissertation). Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, United States. doi: 10.25772/BEWY-BG19

Mendez, J., and Spino, L. (2023). Written “corrective” feedback in Spanish as a heritage language: problematizing the construct of error. J. Second Lang. Writ. 60, 100989. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2023.100989

Mohammad, T., and Rahman, T. (2016). English learners perception on lecturers' corrective feedback. J. Arts Humanit. 5, 10–21. doi: 10.18533/journal.v5i4.700

Nieminen, J., and Carless, D. (2022). Feedback literacy: a critical review of an emerging concept. Higher Educ. 85, 1381–1400. doi: 10.1007/s10734-022-00895-9

Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., and Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int. J. Qualitat. Meth. 16:1. doi: 10.1177/1609406917733847

Poorebrahim, F. (2017). Indirect written corrective feedback, revision, and learning. Indones. J. Appl. Linguist. 6, 184–192. doi: 10.17509/ijal.v6i2.4843

Rowe, A., and Wood, L. (2008). Student perceptions and preferences for feedback. Asian Soc. Sci. 4, 78–88. doi: 10.5539/ass.v4n3p78

Sheen, Y. (2011). Corrective Feedback, Individual Differences and Second Language Learning. New York: Springer Verlag.

Keywords: written feedback, ESL, students' perceptions, learners' experience, teacher's practices, error correction

Citation: Kloss S and Quintanilla A (2024) English as second language learners' practices and experiences with written feedback. Front. Educ. 9:1295260. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1295260

Received: 15 September 2023; Accepted: 20 August 2024;

Published: 10 September 2024.

Edited by:

Vita Kalnberzina, University of Latvia, LatviaReviewed by:

Benjamin Carcamo, University of the Americas, ChileTroy Camarata, Baptist College of Health Sciences, United States

Copyright © 2024 Kloss and Quintanilla. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Angie Quintanilla, YW5xdWludGFAdWRlYy5jbA==

Steffanie Kloss

Steffanie Kloss Angie Quintanilla

Angie Quintanilla