94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 09 April 2024

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1288611

Introduction: This study examines the applicability of the Second Language Writing Anxiety Inventory (SLWAI) to a population of 857 native Arabic-speaking Saudi Arabian female university students learning English as a foreign language (EFL).

Methods: Participants were divided into two groups. The first of these consisted of 430 students who participated in the testing portion of the study. The second group consisted of 427 students who participated in the replication portion of this study. The instrument used was the Second Language Writing Anxiety Index (SLWAI). Exploratory factor analysis was first conducted on the testing group to determine which items of this instrument applied to this population. A second factor analysis was then used to confirm the results found with the testing group.

Results: SLWAI is typically used to assess the degree of EFL writing anxiety across three dimensions: somatic anxiety, avoidance behavior, and cognitive anxiety. However, factor analysis of the data collected from both groups revealed that these dimensions are not entirely pertinent to the population studied. The three dimensions that emerged are somatic anxiety and two distinct aspects of cognitive anxiety: proficiency anxiety and appraisal anxiety. No evidence of avoidance behavior was found.

Discussion: These results suggest that the dimensions measured by the SLWAI may not be universal across differing sociocultural populations. This highlights the importance of assessing anxiety in individual populations with consideration to the unique circumstances in which they learn to write in English as a foreign language. By determining unique aspects of writing anxiety in differing populations, EFL instructors may be better able to identify and then target the needs of their students as they work through the process of developing English-language writing skills.

Although writing can undoubtedly be considered one of the most important of the primary linguistic skills that English as a Foreign Language (EFL) students must develop, EFL writing education cannot be viewed as a monolith. Differing populations across the globe experience unique circumstances that can lead to differences in both motivation and anxiety regarding English-language education. As such, EFL writing instruction must not only consider the educational background and level of students at the time of instruction but also the sociocultural environment in which instruction occurs.

EFL university students in Saudi Arabia are currently preparing for their future during a period of unprecedented rapid cultural and economic transition. Although the country still strongly maintains its collectivist and communally hierarchical social structure (Alrabai, 2018), Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 plan aims to shift the primary national revenue source from oil to more sustainable means. Unveiled in 2016 and beginning its implementation in 2018, one key aspect of this plan is to drastically change the educational and economic opportunities of women. In June 2018, women in Saudi Arabia were granted the legal right to drive along with other autonomy rights, increasing their independence as well as their access to both the educational and economic sectors. By the year 2030, over one million new career opportunities are anticipated to have been made available to women in Saudi Arabia (Kasana, 2022). Female university students in particular are in an extraordinarily unique sociocultural environment. As such, the types of academic anxiety experienced by female as opposed to male EFL students in Saudi Arabia may manifest differently due to the emerging academic and employment prospects of women.

To secure employment opportunities in a globalized world, women in Saudi Arabia are expected to attain a sufficient level of English-language proficiency to allow for fluid and effective communication (Rao, 2019). While much of this communication may take place orally, students must also master proficiency in English-language writing to achieve adequate productivity in the workplace. Unfortunately, academic writing, even in one’s native language, is viewed as the most challenging of the four skills of language (Garcia, 2018). Although the other essential language skills (speaking, reading, and listening) exhibit their own particular challenges, writing includes a uniquely complex combination of specialized competencies. Among these competencies are syntactic knowledge, lexical capacity, understanding of morphology and inflection, orthogonal knowledge, familiarity with the appropriate roles of various forms of punctuation, and comprehension of various styles of writing related to different genres (Diab, 1996). When writing as an EFL learner, the genres of writing used may also differ from those used in an individual’s native language (Singh, 2019). Pragmatic demands may add another level of difficulty to this essential core language skill.

Writing is an extremely complex task that is heavily reliant on working memory, a type of memory that serves three of the most essential building blocks of the writing process (Kimberg et al., 1997). The first of these is maintenance, which entails holding information retrieved from the immediate environment long enough for it to be used as required by a given situation or task. The second of these is retrieval, which consists of recovering information from long-term memory and holding it long enough for it to be put to use. The third and most critical function of working memory is information manipulation. It consists of the writer’s ability not only to hold new and past information in consciousness but also to perform operations to transform it. Writing in one’s native language requires the use of cognitive and linguistic resources, which are more difficult to access under anxiety-inducing circumstances (Karr and White, 2022). When writing in a foreign language, these linguistic resources are generally limited as compared to those available in one’s native language. As such, greater focus and attention are required to successfully produce a written product (Kim et al., 2021). Greater demands for effort may lead to greater levels of writing anxiety in EFL learners.

As with other complex tasks, writing is a skill that can best be improved by practice. For many EFL students, this practice takes place in the classroom environment. In this environment, instructors are able to observe writing and provide immediate feedback, thereby allowing students to reflect upon and improve their work (MacArthur and Philippakos, 2023). However, to implement effective, student-centered pedagogy, it is important to understand the distinct needs of particular student populations to best target impediments specific to their writing. These impediments may include unique aspects of writing anxiety in EFL students living under different sociocultural circumstances.

One measure of EFL writing anxiety that has been used across a multitude of populations is the Second Language Writing Anxiety Index (SLWAI; Cheng, 2004). This measure consists of 22 items rated by EFL writing students using a 5-point Likert scale. The SLWAI was originally created and normed on students majoring in English at a Taiwanese university. The items in this measure were found to map onto three different manifestations of writing anxiety: somatic anxiety, avoidance behavior, and cognitive anxiety. It has since been used to assess writing anxiety across these dimensions in EFL students at varying educational and English-language proficiency levels around the globe (e.g., Min and Rahmat, 2014; Dar and Khan, 2015; Golda, 2015; Jebreil et al., 2015; Yastibas and Yastibas, 2015; Kabigting et al., 2020; Nugroho and Ena, 2021; Jaleel and Rauf, 2023).

In rare instances, the SLWAI has been tested in particular foreign-language populations to assess its applicability as a measure of the multidimensional structure of writing anxiety. Li et al. (2018) assessed the validity of the SLWAI on middle-school EFL students in mainland China, where it was found that the three subscales defined by Cheng (2004) applied to the population tested. However, differing results were found by Jang and Choi (2014) when validating this measure on Korean EFL students studying at the college level. In this study, researchers found that 11 of the 22 items of which the SLWAI is comprised did not fit the model used in their study. The results of the work of Jang and Choi (2014) indicate that the SLWAI may not adequately assess the three dimensions of writing anxiety found by Cheng (2004) when applied to EFL learners of unique first language backgrounds and sociocultural circumstances.

In the present study, we examine the applicability of the SLWAI to female EFL university students in Saudi Arabia. That is, whether the SLWAI can best be used either as a universal measure of EFL writing anxiety or as a measure of writing anxiety with unique dimensions within an individual sociocultural student population. The inventory was administered to 857 students at a Saudi Arabian university following a United States-based curriculum. These students were divided into two groups. The first group consisted of 430 participants. It served to test the extent to which the dimensions typically defined by the SLWAI apply to this unique population. The second group consisted of 427 participants whose results were used to confirm those found in the first group. The findings of this study will assist EFL writing instructors in determining the most effective way to use the SLWAI to address the needs of the students with whom they work as they develop their academic writing skills.

Anxiety can be described as an emotional state in which one experiences unpleasant tenseness and apprehension (Sarason et al., 1990). Anxiety can lead to disturbances in sustained attention as well as knowledge retention and retrieval. Anxiety may generalize to much, if not all, of everyday life. However, it may also manifest in unique ways in relation to specific situations and circumstances. One circumstance that often leads to experiencing anxiety is involvement in one or more aspects of the academic environment (Mohebi et al., 2012). For EFL learners, academic anxiety in foreign language classes may manifest as foreign language anxiety (FLA). While FLA often relates primarily to the apprehension and tenseness felt when required to use a foreign language, in the academic setting, FLA includes a complex set of feelings, beliefs, and behaviors related to the experience of the classroom-based, language-learning process. Foreign language classroom anxiety was originally defined by Horwitz et al. (1986) as related to three distinct forms of performance anxiety: communication apprehension, test anxiety, and fear of negative evaluation. Krashen (1987) identified emotional factors, such as anxiety, confidence, and motivation as capable of impacting foreign language learning. Not surprisingly, students who experience anxiety also tend to exhibit lower self-efficacy (i.e., confidence in themselves), emotional intelligence, and writing attainment (Pilotti et al., 2024). Higher levels of FLA are accompanied by lower academic outcomes in EFL classes (Alsowat, 2016; Ozer and Akcayoglu, 2021; Xu et al., 2022), including poor writing quality (e.g., increased use of concrete words, and brevity of exposition; Waked et al., 2023). Deficient performance may in part be due to the relationship between FLA and academic motivation. Decreased academic motivation may in turn lead to foreign language avoidance in which EFL learners utilize all available means to circumvent situations requiring the use of English (Choi et al., 2019). Consistent with this notion is the finding that students’ learning orientation (i.e., a disposition to see formal education as an opportunity to acquire knowledge and skills) is linked to lower writing anxiety and increased contentment (Pilotti et al., 2023).

In addition to the overarching concept of FLA, each of the four skills of language can also induce unique forms of anxiety. These four skills include reading, listening, speaking and writing. In EFL research, much of this anxiety has been examined on what Horwitz et al. (1986) deemed communication apprehension. Of the four skills of language, only speaking and writing demand direct interpersonal communication. Anxiety linked to speaking in EFL learners is an area of particular concern, due to not only its commonality but also its unique manifestations across different speaking environments (e.g., Tian and Mahmud, 2018; Tahsildar, 2019). Various measures have been created to assess speech anxiety, such as the Public Speaking Class Anxiety Scale (Yaikhong and Usaha, 2012) and the Foreign Language Speaking Self-Efficacy Scale (Ocak and Olur, 2018). Similarly, a number of different measures have emerged over the years examining the unique facets of writing anxiety. A well-known instrument for assessing writing anxiety in foreign language learning is the tool developed by Cheng (2004). Notwithstanding its popularity, the measurement of writing anxiety has produced unclear results concerning its dimensionality. Namely, the extant evidence has treated this construct as multidimensional but the dimensions or facets uncovered do not consistently overlap with those of Cheng (2004), especially with Middle Eastern student populations. For instance, Alsowat (2016) reported moderate levels of anxiety in Saudi Arabian female students linked primarily to worrying about failing and testing. Aloairdhi (2019) found that anxiety in the same population was linked to fear of evaluation and low confidence, albeit her study included writing as just one of the skills linked to anxiety. Through SLWAI, Pilotti et al. (2024) found that writing apprehension could be divided into two cognitive components: concerns about appraisal/evaluation and state of mind (e.g., thoughts related to writers’ negative expectations). Instead, Jebreil et al. (2015), who administered SLWAI to Iranian students, reported all dimensions of anxiety uncovered by Cheng (2004) but noted that cognitive anxiety was the most prevalent.

Writing anxiety was first examined in individuals writing in their native language. In probing native speakers of English, ‘writing apprehension’ was defined by Daly and Miller (1975) as a dysfunctional anxiety that may impede the successful completion of writing tasks. Later research further expanded upon this concept to include dislike of the writing process (Madigan et al., 2013). As with general foreign language anxiety, writing anxiety can lead to avoidant behaviors. Instances of the latter are offered by university students who curtail writing anxiety by avoiding registering for writing classes or those who select university majors that require fewer writing courses (Cheng and Liu, 2022).

One measure of writing anxiety that can be used with EFL learners is the SLWAI. The items in this inventory are based on previously existing measures of writing anxiety. Among these are items found in Daly and Miller’s Writing Anxiety Test (1975), McKain’s Writing Anxiety Questionnaire (1991), McCroskey’s Personal Report of Communication Apprehension (1970), MacIntyre and Gardner’s English Use Anxiety Scale as well as their English Classroom Anxiety Scale (1988), and Shell et al.’s English Use Anxiety Scale (1989). In creating this index, Cheng (2004) intentionally intended for the items in the SLWAI to assess the three independent components of writing anxiety found by Lang (1971), which consisted of cognitive, physiological, and avoidance reactions.

Prior to constructing the items in his final inventory, students at a Taiwanese university were asked, through open-ended questions in their native language (Chinese), to describe aspects of the anxiety they felt when writing in EFL. Thirty-three items were originally generated from these questionnaires, which were then evaluated by three professors with a background in psycholinguistics and who had experience working in EFL anxiety. The assessment of face validity was followed by pilot testing on other Taiwanese college-level students. These preliminary assessments of the inventory resulted in reducing the total number of items to 27. Further analyses of these items through testing of a population of 421 EFL Taiwanese students majoring in English confirmed the inclusion of the 22 items used in the SLWAI today.

According to Cheng (2004), the SLWAI tested on Far Eastern student populations assesses three separate dimensions of anxiety linked to writing in a foreign language: somatic symptomatology (i.e., increased physiological arousal), cognitive changes (i.e., worries and concerns about negative evaluations), and behavioral aspects (i.e., avoidance behavior). Somatic anxiety specifically refers to the subjective perception of the physiological correlates of the experience of anxiety, such as increased autonomic arousal, nervousness, upset stomach, elevated heart rate, and sweating.

Cognitive anxiety refers to the thought processes that define the experience of anxiety, including negative expectations, worries about performance, and distracting concerns about the opinions and judgments of others. Avoidant behavior is a manifestation of anxiety that has been examined in both native and non-native writers. The seemingly common desire to simply avoid writing by individuals experiencing writing anxiety conflicts with evidence that writing is a skill that benefits from regular practice (Alharthi, 2021). As in other forms of skill-related anxiety, improved writing performance is associated with decreased writing anxiety (Balta, 2018; Cheng and Liu, 2022). At many academic levels, writing is often taught through the process of practice, feedback, and revision. This process allows writers not only to improve a single piece of composition but also to transfer the skill to other communicative endeavors. With instructor feedback, students navigate the process of more effectively expressing themselves in writing in new styles and genres, likely decreasing the desire to express avoidant behavior toward writing (MacArthur and Philippakos, 2023).

Dedicated written composition courses at the college and university level aim to help students develop the skills needed to write varying forms of composition as well as to learn writing skills that will aid them in their future courses and careers. Crucial to skill development is not only instructor feedback but also the revision process. It is through this process that students are able to put into practice suggestions that will improve their writing skills. In this context, they have the opportunity to examine their own work more thoroughly and decide for themselves how they will execute the suggestions in the feedback they have received (MacArthur and Philippakos, 2023). However, particularly in the context of EFL writers, the type of feedback provided may be most beneficial if tailored to the specific population of a given class. Features for instructors to consider include, age, educational level, English-language proficiency, and sociocultural factors that may impact both anxiety and motivation (Cabrara-Solano et al., 2018; Basoz and Erten, 2019).

For EFL writers, one issue of concern that may differentially impact varying populations is the degree of similarity between learners’ first language and their target language. Linguistic features may impact the degree to which first language interference may complicate developing English-language writing skills. Diab (1996) described the phenomenon of language interference as the detrimental role that the innate knowledge of one’s native language has on the ability to learn a second or foreign language. Due to the particular differences between the morphosyntactic, orthogonal, and phonological structures of English and Arabic, negative linguistic transfer may yield different errors in first-language speakers of Arabic than in EFL students with other first languages.

Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) is the high level of the diglossic linguistic systems existing within the Arabic-speaking nations of the Middle East and North Africa. Diglossia may be defined as a linguistic environment in which a language exists in two distinct forms, one viewed as the higher-level form and the other as the lower-level form. In Arabic, the lower level form is the regional colloquial dialect which is acquired naturally and used in informal situations. The higher-level form, MSA, is standardized throughout Arabic-speaking nations and is used in formal situations. Education in Arabic-speaking nations often takes place primarily in MSA with English-language instruction introduced at varying levels of education (Daqar, 2018).

One key difference between MSA and English is that the base form of a root word in Arabic is often a verb consisting of three consonants which can be inflected to produce nouns as well as other verbs reflecting person, tense, number, and gender (Scott and Tucker, 1974). Differences in word order and the rules of subject-verb agreement may lead to some of the common errors found in the writing of EFL learners who are native speakers of Arabic. Sentences written in MSA often begin with a verb and may only state a noun or pronoun once in a paragraph. As written MSA allows subject drop, this feature often crosses over into the English-language writing of EFL students who are native speakers of Arabic. The comma [,] also plays a notably different role in writing in MSA as compared to its role in English-language writing. This form of punctuation often functions in the capacity of the period [.] in English. As such, it is not uncommon for paragraphs written in MSA to be comprised of what a native speaker of English would perceive to be a single sentence. All of these grammatical features of MSA may be found in the writing of native Arabic-speaking EFL students (Khatter, 2019).

Diab (1996) examined grammatical errors in EFL students who were native speakers of Arabic living in Lebanon. Errors included subject-verb agreement, the use of modifiers for singular and plural nouns, the use of prepositions, and the inflection of nouns to produce both plural forms as well as adjectives and adverbs. For native speakers of Arabic living in Saudi Arabia, Alkhudiry and Al-Ahad (2020) found that writing errors primarily occurred in subject-verb agreement, verb inflection, sentence and word structure, spelling irregularities, and vocabulary. Khatter (2019) also found that the majority of errors in English-language writing in Saudi Arabian EFL students were found in punctuation. All these linguistic features differ greatly between MSA and English, and, as such, are prone to appear as part of the negative transfer effects in the writing of EFL students who have primarily been educatedin MSA.

Awareness that there are numerous differences in the writing systems of one’s native language and English without full knowledge of the specificity of these differences may be anxiety-inducing in EFL writers. This anxiety may be further exacerbated by limited English-language lexical knowledge. As such, it is beneficial to evaluate which particular aspects of writing anxiety most apply to native speakers of a specific language living in a given sociocultural environment. EFL instructors can then best engage with their students and support them through the process of learning to write in their foreign language (Basoz and Erten, 2019).

Much research on EFL student outcomes has traditionally focused on learning about cultures in which English serves as the primary medium of communication. This research is often based upon the premise that language and culture are so thoroughly intertwined that to effectively obtain proficiency in a second/foreign language, students must also become knowledgeable of the culture(s) in which this language is used (e.g., Kramsch and Hua, 2016; Nambiar and Anawar, 2017; Nguyen, 2017). Aldawood and Almeshari (2019) have argued that this approach is most suitable for EFL university-level students in Saudi Arabia due to the interest they show in learning about a new culture. However, some studies have begun to discuss the importance of considering the culture of the country in which EFL learning is taking place during instruction. In studying English in the context of the local culture, EFL students are able to reflect upon the ways that this language applies to both their current and future lives. Alakrash et al. (2021) suggest incorporating aspects of local culture into the EFL curriculum to better engage students. They posit that students will retain greater focus, resulting in improved academic outcomes, if classroom material is seen to be relevant to their personal lives. Similarly, in his study of Saudi Arabian university students, Aldera (2017) found that when presented with EFL teaching material from a culture associated with the English language, students are likely to show more positive attitudes to aspects of the culture that reflect values upheld by their own local culture.

As English has developed into a Linga Franca and has taken on a global role, it may be more beneficial to approach English through the theory of World Englishes. According to this view, different forms and dialects of English develop within individual cultures and environments. Bhatt (2021) defined World Englishes as a “pluricentric view of English, which represents diverse sociolinguistic histories, multicultural identities, multiple norms of use and acquisition, and distinct contexts of function.” In this way, English becomes reflective of the individual society in which it is both taught and used while remaining a universally systematic and structured code of international communication. The concept of World Englishes also allows for generational adaptations of the English language, including new varieties of code-switching as English becomes further assimilated into the lexicon of individual cultures and societies (Sridhar and Sridhar, 2018). Thus, beginning from a framework of the local forms of World English to which their EFL students are exposed, EFL instructors may be better able to circumvent anxiety arising from learning academic and professional forms of English taught in the classroom. Writing anxiety may be the ideal beneficiary of this approach to foreign language instruction.

Participants in this study included a convenience sample of 857 female undergraduate students enrolled in courses of the general education curriculum at a Saudi Arabian University that complies with a US curriculum and advocates a student-centered pedagogy. In this student population, both collectivistic and individualistic orientations exist (Pilotti and Waked, 2024). Collectivism results from tribal and religious traditions, whereas individualism primarily stems from outside influences in an increasingly globalized world. Students’ socioeconomic status may be classified as middle class based on their parents’ income. The Pew Research Center (2016) defines a middle-class income as one that is between 67 percent and 200 percent of the median household income of a country.

Students were divided into two groups. The testing group consisted of 430 participants, while the replication group consisted of 427 participants. The average age of participants was 19.45 years. They were either freshmen or sophomores. To enroll in courses of the general education curriculum, students must obtain an overall International English Language Testing System (IELTS) score of at least 6.0 and a 5.5 IELTS writing score (range: 0–9). As such, the selected sample included a variety of English-language proficiency levels, ranging from modest to competent English-language learners. This population is often neglected in the extant literature in favor of introductory-level learners.

This study used a slightly modified version of the SLWAI known as the SLWAIr. Revisions occurred only in the surface-level wording of some items to simplify vocabulary and to make items more easily understood by the population studied. An example of these revisions could be the alteration of the phrase “write English composition,” which was changed to “write assignments in English.” The development of SLWAIr entailed the assessment of face and content validity as well as test–retest reliability. As reported by Pilotti et al. (2024), for face validity, Cohen’s Kappa Index (CKI) was 0.80, which was above the minimal criterion of 0.60 interrater agreement. The content validity ratio was 0.83, which was above the minimum 0.62 required for the retention of items (Lawshe, 1975). The value of test–retest reliability was 0.94. To ensure optimal reading comprehension, each item of the inventory was also accompanied by an Arabic-language translation written below the revised English-language material. Responses were collected through a 5-point scale from strongly agree (+2) to strongly disagree (−2) with 0 serving as the neutral point. The questionnaire was preceded by a few demographic questions inquiring about participants’ age, nationality, first language, and educational level.

Participants were given approximately 15 min to complete the SLWAIr. They were informed that the study entailed the completion of a questionnaire devoted to their attitudes and reactions to writing in English along with their responses to some demographic questions. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups. The second group was used to assess the replicability of the results obtained in the first group. Students provided informed consent before participation. All materials were displayed online through a link that directed students to the demographic questions and the writing anxiety inventory. To ensure anonymity, no identifying information was preserved in data files. During debriefing, students were provided with a brief review of the phenomenon of writing anxiety in its manifestations and consequences. The data collection process was performed in the last months of the semester to ensure that all participants had sufficient experience with college life. The study was approved by the Deanship of Research. It was deemed to comply with the guidelines of the Office for Human Research Protections of the US Department of Health and Human Services as well as with the American Psychological Association’s ethical standards in the treatment of research participants.

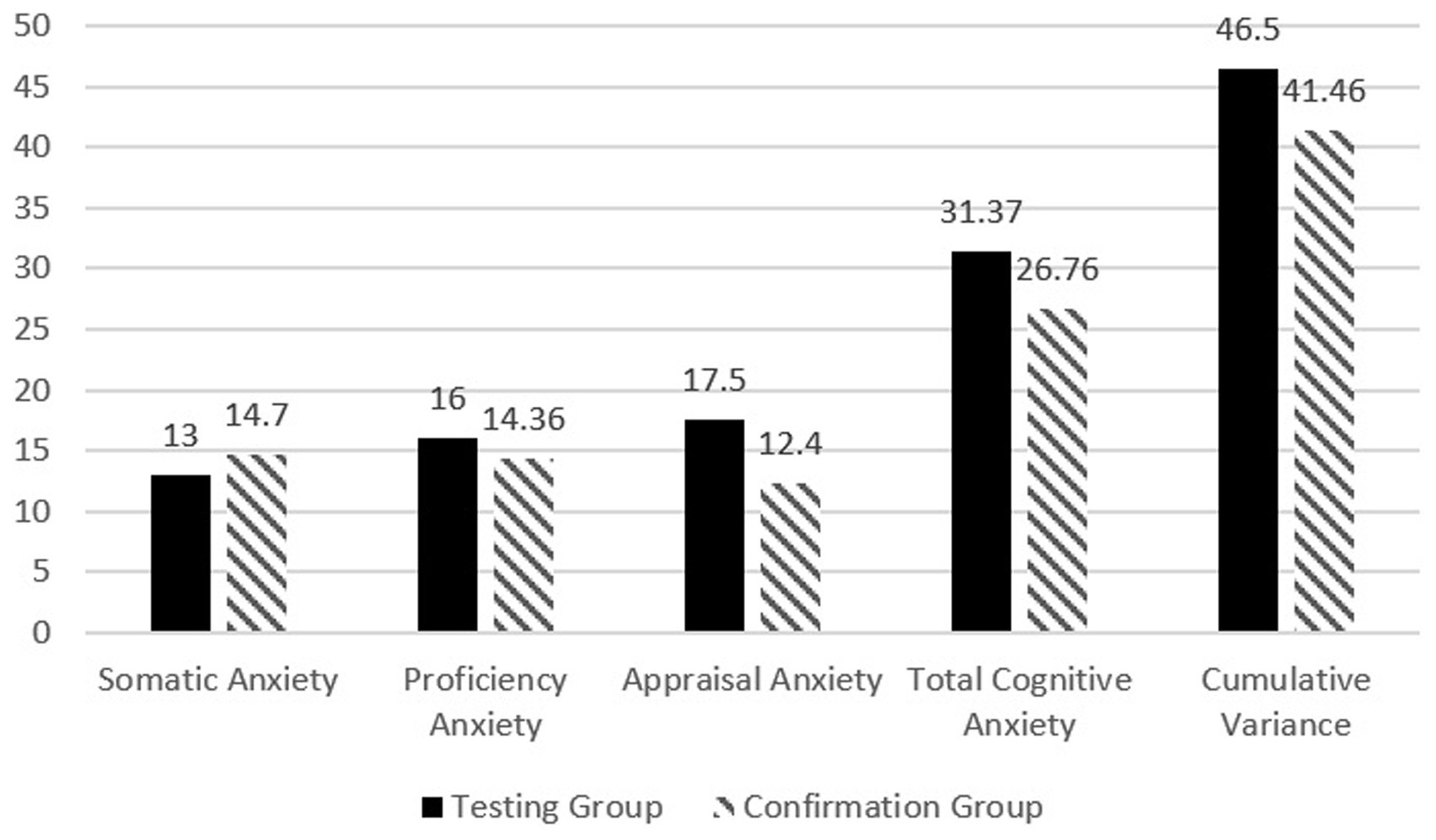

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) was used for data analyses. The data of the SLWAIr were submitted to exploratory factor analysis to determine which items would load onto dimensions of relevance to the selected population. A varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization was applied before analysis. Only items with a factor loading of 0.5 were used to ensure that the variables extracted explained at least 75% of the variance (Taherdoost et al., 2014). The eigenvalue criteria for this analysis were set at a criterion of >1. Similar to Cheng’s original work (2004), data were analyzed using the scree test, rotated percentage of variance accounted for by each dimension, rotated cumulative variance, and rotated component matrix (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Percentage of variance of factors loaded using varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization.

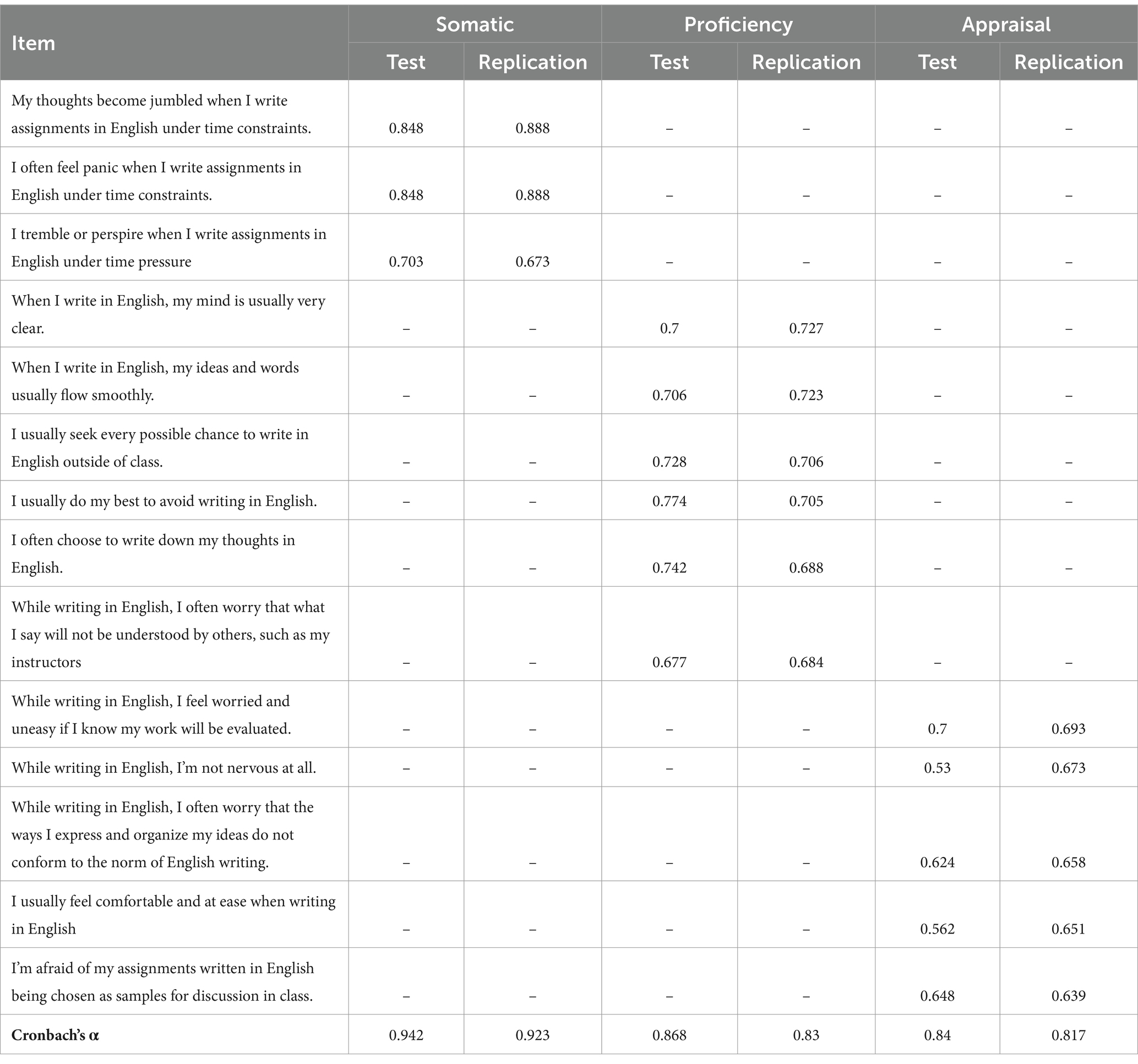

As shown in Table 1, items in the SLWAIr were found to load onto three factors in both the test and replication groups. In Cheng’s (2004) original SLWAI, the dimensions measured included somatic anxiety, avoidance behaviors, and cognitive anxiety. Among the members of the population selected for our study, these factors also included the category of somatic anxiety. However, there was no factor associated with aspects of avoidance behavior. Cognitive anxiety was also found to load onto two distinct factors: proficiency anxiety and appraisal anxiety. Items representing proficiency anxiety related to concerns regarding one’s knowledge and/or understanding of English as reflected in one’s writing. Items representing appraisal anxiety related to concerns regarding the evaluation of one’s writing.

Table 1. Varimax rotated component matrix with Kaiser normalization showing items which loaded onto factors in both the testing and replication groups.

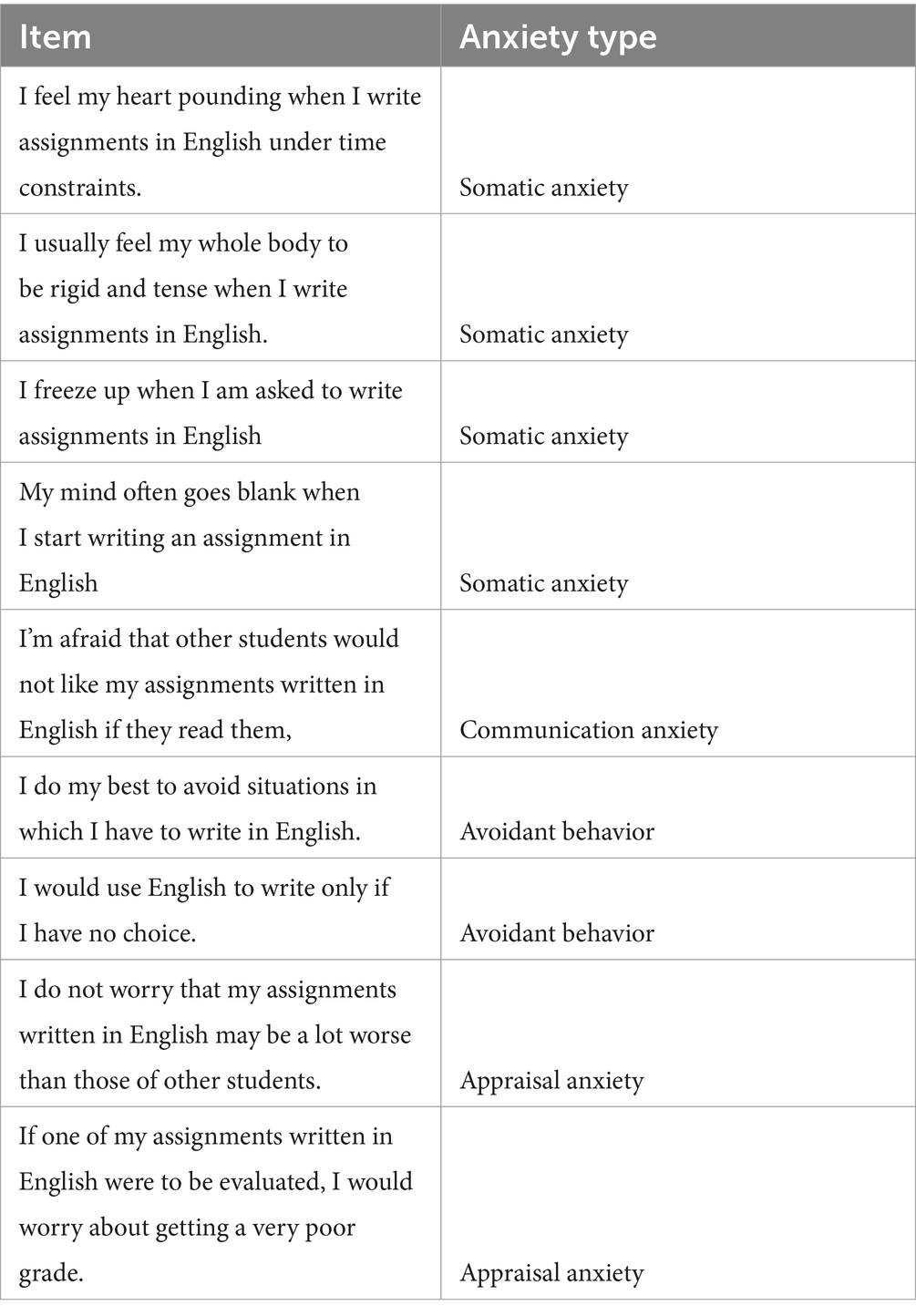

Three items were found to load onto the factor of appraisal anxiety in the test group but not the replication group (see Table 2). Of these items, two can be categorized as avoidant behavior and the other as a manifestation of appraisal anxiety. There were no differences between the two groups in the items that loaded onto the dimensions of communication anxiety or somatic anxiety. Of the 22 items used in the SLWAIr, nine were not found to load onto any dimension (see Table 3). Of these nine items, four can be categorized as somatic anxiety, two as avoidant behavior, two as appraisal anxiety, and one as proficiency anxiety.

Table 2. Items that loaded onto the factor, appraisal anxiety, in the testing group, but not in the replication group using varimax rotated component matrix with Kaiser normalization

Table 3. Items that did not load onto factors in either group using varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization.

In this study, we examined the applicability of SLWAIr to female EFL students from a Saudi Arabian university following a United States-based curriculum. Participants were native speakers of Arabic whose primary language of instruction prior to entering college was MSA. Participants were divided into two groups, one to test SLWAIr on the aforementioned population and the second to perform a replication. At the time of testing, the English-language proficiency of participants ranged from modest to competent as reflected in their scores on the IELTS examination. Results indicated that the three dimensions of writing anxiety originally identified by Cheng (2004) in his seminal work on EFL Taiwanese students do not perfectly fit the dimensions uncovered in EFL Saudi Arabian students. Our results found no evidence of avoidance behaviors but rather two distinct categories of cognitive anxiety (i.e., proficiency anxiety and appraisal anxiety). One possible interpretation of these findings is that for this particular population of EFL students, writing anxiety does not include inclinations of avoidant behavior. Rather, the students examined are primarily concerned with their proficiency in the English language as reflected in their writing as well as how their writing is perceived by others. Alternatively, the absence of reports of avoidance behaviors may be traced to the time at which the data collection was performed. At the start of the semester, opportunities to avoid work are to a certain extent available to students (e.g., procrastination). Thus, in debriefings, students describe instances of avoidance behaviors as rather normal occurrences in their lives. Toward the end of the semester, students become keenly aware that opportunities for delays are no longer available. Thus, their anxiety focuses on proficiency and appraisal of their work. Indeed, when a similar student population was tested at the start of the semester (Pilotti et al., 2024), avoidance behaviors emerged as a dimension of students’ anxiety. It follows that another important factor that needs to be considered in the data collection of self-reported measures is the time of administration. The latter can determine the relevance of specific dimensions at particular times in students’ quotidian lives.

The importance of self-perception of proficiency is not unique to the population of Saudi Arabian female students who participated in our study. Bensalem (2018) also found that higher ratings of self-perception of English-language proficiency in EFL students predicted lower levels of FLA at three public Saudi Arabian universities. The relationship between self-perception of English-language proficiency and FLA has been reported in studies on various language groups in other cultures as well (e.g., Arnaiz and Guillén, 2012; Liu and Chen, 2013; Dewaele and Al Saraj, 2015). Botes et al. (2020) reported that higher levels of self-perceived EFL proficiency predicted not only lower levels of FLA but also higher levels of EFL class enjoyment. However, although the connection between the perception of language proficiency and FLA has been explored, to our knowledge, proficiency anxiety as a form of FLA anxiety, or more specifically, an aspect of EFL writing anxiety, has received scant attention.

Conversely, appraisal anxiety appears to have been more often explored with regard to EFL writing anxiety. Similar to our findings, Aloairdhi (2019) also reported appraisal anxiety to be a significant aspect of writing anxiety for female students at multiple Saudi Arabian universities. Appraisal anxiety in writing activities has also been found in EFL students from a diverse range of linguistic and sociocultural communities, including students in Afghanistan (Quvanch and Na, 2022), Indonesia (Kusumaningputri et al., 2018) and Korea (Jeon, 2018). This finding is unsurprising as the majority of academic communication by EFL learners takes place via writing. Anxiety regarding academic success can be directly linked to appraisal anxiety. Thus, appraisal anxiety may be viewed as a universal factor of writing anxiety among EFL students.

Although dimensions such as appraisal anxiety may be generalizable to other EFL linguistic and sociocultural communities, EFL instructors need to remain cognizant of the background and sociocultural environment of the particular population of students with whom they work. One important factor that must be considered is the native language of speakers within a population. Considerations of the extent to which differences can be found between the writing system of the native and/or primary language of instruction and the English writing system are unavoidable tools of instruction. They can assist instructors in both predicting and understanding the errors in the writing of their EFL students that reflect negative transfer effects. Instructors’ knowledge and understanding of the extent to which the written systems of the native and target language differ may also assist them in tailoring their lesson plans and classroom environment to better target the particular types of language transfer that may exacerbate EFL students’ writing anxiety. Of course, instructors need to remain aware of the range of proficiencies found in any EFL classroom. Although students in the current study ranged from modest to proficient English-language users, for more introductory-level students, differences between the grammar of their native language and that of English along with vocabulary limitations may also hinder EFL students’ understanding of classroom instruction (Goodfellow, 2004; Lalasz et al., 2014).

The results of the current study indicate that for this particular population, writing anxiety manifests as somatic anxiety, proficiency anxiety, and appraisal anxiety. Unlike Cheng’s (2004) original dimensions of the SLWAI, no avoidant behavior was found among this population. This discrepancy may be due in part to the cultural aspects of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia is traditionally both a hierarchical and collectivist culture. The successes and failures of one member of a community may become reflective of the community overall. Additionally, due to the hierarchal nature of the Saudi Arabian culture, obedience to those viewed as authority figures is expected as a social norm. As such, instructors are generally seen as authority figures to be obeyed within the classroom. This approach to conformity and obedience may lead students in the population studied to be less likely to consider avoidance of writing in English as a viable option (Alrabai, 2018), especially at the end of the semester when time no longer appears expendable. Thus, the timing of the administration of a writing anxiety inventory along with cultural norms emerge as notable environmental factors in research on writing anxiety. On the other hand, concerns regarding proficiency may reflect students’ desire to perform at the highest possible standard and best represent themselves to the instructor who is the authority figure in the classroom. Similarly, appraisal anxiety may also reflect students’ desire to possess a tangible reflection of their academic success that may be presented to other authority figures, such as parents and/or guardians. Namely, both proficiency and appraisal concerns are much more likely than avoidance behavior to be insensitive to the timing of the administration of a self-report measure targeting writing anxiety. Such concerns exist across the entire semester (as per the qualitative data collected during debriefing sessions).

For EFL instructors in Saudi Arabia, one long-standing aspect of Saudi Arabian culture may also be impactful. That is, many aspects of daily life are gender segregated, including most educational environments up through the university level. As a result, the sociocultural environments and expectations placed upon male and female Saudi Arabian EFL students may differ. Bensalem’s study (2018) on EFL Saudi Arabian students found a significant difference between the levels of FLA exhibited by male and female university students, with female students showing a greater degree of FLA than their male counterparts. Gender differences may, in part, reflect differences in students’ daily lives as well as social and familial expectations. Elnadi et al. (2020) found that social norms, including expectations of the family and community, impact students’ perceptions of future entrepreneurial goals differently depending on the gender of Saudi Arabian university students. Given these differences, male and female EFL students may best be considered as distinctly separate populations when the assessment of FLA and anxiety affiliated with specific language skills is performed. Further investigation is needed to assess the anxiety dimensions that are relevant to male university students in Saudi Arabia to better determine whether there are in fact gender differences and, if so, what the causes of any differences may be.

Although the aforementioned integral aspects of Saudi Arabian culture are predominantly intended to be upheld, the implementation of Vision 2030 has led to numerous changes within the country. Since the launch of the Saudi Arabian government’s international scholarship program in 2000, educational opportunities for women have drastically increased. Many female students have received government assistance in obtaining university degrees from English-dominant nations. The importance of English as a global language has also become more widely recognized in Saudi Arabia, impacting the K-12 pedagogical structure. Although formal English language education was not previously introduced into many public and private schools until approximately the tenth grade, students now begin English classes in the first grade throughout Saudi Arabia. Many of the Saudi Arabian females in the population tested did not have the opportunity to begin writing in English until fairly far along in their high school educational career. Nevertheless, they are fully aware of the importance of English language proficiency in both their academic and occupational prospects (Kasana, 2022).

Much like the way in which the unique needs of the population tested in this study are reflected in our re-analysis of the SLWAI, EFL educators in other environments may be able to use standardized measures to better identify the types of writing anxiety experienced by the specific population of students with whom they work. This information can be used to adapt the EFL classroom environment to better serve the needs of their students as they navigate the process of learning to write in English. The type and tone of feedback given during the revision process may also be altered through the use of this information to best target the impediments to learning most applicable to instructors’ specific student population. In the population studied, the three dimensions of anxiety students were found to exhibit were somatic, proficiency, and appraisal anxiety. Through practice with targeted instructor feedback, the revision process may become more efficient and effective. Positive feedback focusing on recognizing specific areas of improvement may alleviate proficiency anxiety. Greater practice with instructor feedback prior to the submission of written assignments may lessen students’ appraisal anxiety as they may feel greater reassurance that errors have been adequately addressed. With classroom interaction that directly targets proficiency and appraisal anxiety, somatic symptoms of anxiety may be reduced as well.

As shown in this study, tools such as the SLWAI do not necessarily best serve EFL students when used as definitive measures of universal features. Diverse sociocultural environments may differentially impact the types of anxiety experienced by EFL students learning to write in English. Writing is a complex skill that is essential for academic and occupational success in the current global market. As with other complex skills, anxiety can serve to impede both performance and improvement. By learning what types of writing anxiety most impact their EFL students, instructors will have the opportunity to alter their classroom management, teaching style, and manner of feedback to ensure that they are employing best practices in guiding their students to develop and advance English-language writing skills.

The results of this study raise a number of possible areas to be examined in future research. The first of these is the fact that participants in this study consisted solely of female students studying in one university. Other universities throughout the country also use United States-based curricula and only accept students with moderate to proficient English language skills. Such students are comparable to the participants of this study. Should the findings of this study be replicated in other areas of Saudi Arabia, the argument that the rapid cultural shift of Vision 2030 plays a role in particular dimensions of writing anxiety found in female Saudi Arabian EFL students would be strengthened. Additionally, it may be prudent to study the writing anxiety of university students of lower levels of English language proficiency. If female students display similar results across the country and levels of English-language proficiency, the sociocultural environment of a country can be said to impact the dimensions of writing anxiety.

Undeniably, a key limitation of this study is that only female students were accepted as participants. The premise of selecting only female participants rests upon the notion that, due to the uniquely significant changes in the roles to be played by women under Vision 2030, females in Saudi Arabia exist within a different sociocultural environment than males. The role of males under Vision 2030 does not require a comparable degree of change. However, like their female counterparts, Saudi Arabian males also live within a hierarchical and collectivist culture in which both their successes and failures are partially viewed as the successes or failures of their greater families and immediate communities. Future studies should examine whether these forms of writing anxiety are present in male students in the same university environment(s) as those of female participants. Should similar results be found, this may have implications for the types of writing anxieties found among EFL students in other collectivist and hierarchical cultures beyond Saudi Arabia.

As many other Middle Eastern and North African countries are also both collectivist and hierarchical in nature, it may be prudent to determine whether these results can be replicated in cultures that are not experiencing the rapid sociocultural shift of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030. Replication could be especially beneficial because these countries also often use MSA as the primary language of education at the K-12 level. Should participants include native speakers of Arabic from other countries along the Arabian Gulf, colloquial dialects of Arabic are unlikely to significantly differ. As such, there should be no notable differences in the quantity or type of language transfer experienced by EFL writers in such countries and in Saudi Arabia. Should similar results be found between comparable populations in sociocultural environments that primarily differ only in the rapid shifts brought on by Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, they may indicate that the evolving role of women is not a factor in the types of writing anxiety observed. However, differing findings may provide support for the argument that all sociocultural differences must be considered when using a standardized test such as the SLWAI to assess the forms of writing anxiety experienced by EFL learners.

Perhaps the most pressing issue raised by this study is the examination of whether populations outside the Middle East and North Africa also produce outcomes on standardized tests that cluster around factors unique to their sociocultural environment(s). To best determine whether different cultures induce unique forms of writing anxiety, the examination of standardized writing assessments must be replicated in countries whose primary language of instruction and sociocultural norms and beliefs differ from those predominantly found in the Middle East and North Africa. The findings of this examination could potentially lead to improved pedagogical methodology for teaching writing to EFL learners worldwide.

The results of this study indicate that the specific types of writing anxiety experienced in different sociocultural environments may be differentially accounted for by the reanalysis of some standardized tests. Cheng (2004) developed the SLWAI to assess three distinct forms of writing anxiety: somatic anxiety, cognitive anxiety, and avoidant behavior. However, factor analysis revealed that, for the particular population tested in this study, these forms of writing anxiety were not entirely applicable. For Saudi Arabian females studying at a university during a period of rapid sociocultural shifts, avoidant behavior does not appear to be an issue of concern. Rather, this particular population appears to experience somatic anxiety as well as two distinct forms of cognitive anxiety not originally accounted for by Cheng (2004). These discrepancies indicate that EFL students may benefit from differing pedagogical methods to best lessen both appraisal anxiety and proficiency anxiety. They also indicate that educators working with members of this population need not be overly concerned with avoidant behavior in the classroom, at least at the end of the semester.

The findings of our study have implications for the international use of standardized assessments. They suggest that assessment must be more directly tailored to fit the needs of EFL students in a variety of sociocultural environments. Although the findings of this particular study may be more applicable to communities in Saudi Arabia and the Arabian Gulf, it is also possible that other unique forms of writing anxiety could be discovered by educators through similar reanalyses in other sociocultural environments.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by Prince Mohammed Bin Fahd University Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

AW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. OE: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KE: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RA: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

We are grateful to the members of the Cognitive Science Research Center and the students of the Undergraduate Research Society for their help in data collection and feedback. We are particularly grateful to Miss Amnah Alsaeed, Miss Lama Alqahtani, and Miss Minnah Yassin for their assistance.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Alakrash, H., Edam, B., Bustan, E., Armnazi, M., Enayat, A., and Bustan, T. (2021). Developing English-language skills and confidence using local culture-based materials in EFL curriculum. Linguist. Antverpiensia 1, 548–564. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350324251.

Aldawood, A., and Almeshari, F. (2019). Effects of learning culture on English-language learning for Saudi EFL students. Arab. World English J. 10. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol10no3.23

Aldera, A. (2017). Teaching EFL in Saudi Arabian context: textbooks and culture. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 8, 221–228. doi: 10.17507/jltr.0802.03

Alharthi, S. (2021). From instructed writing to free-writing: a study of EFL learners. SAGE Open 11, 1–15. doi: 10.1177/21582440211007112

Alkhudiry, R., and Al-ahad, A. (2020). Analyzing EFL discourse of Saudi EFL learners: identifying mother tongue interference. Asian ESP J. 16, 89–109. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com.

Aloairdhi, N. M. (2019). Writing anxiety among Saudi female learners at some Saudi universities. Engl. Lang. Teach. 12, 55–65. doi: 10.5539/elt.v12n9p55

Alrabai, F. (2018). “Learning English in Saudi Arabia” in English as a foreign language in Saudi Arabia: New insights into teaching and learning English. eds. C. Moskovsky and M. Picard (Albingdon: Routledge), 102–119.

Alsowat, H. H. (2016). Foreign language anxiety in higher education: a practical framework for reducing FLA. Eur. Sci. J. 12, 193–220. doi: 10.19044/esj.2016.v12n7p193

Arnaiz, P., and Guillén, P. (2012). Foreign language anxiety in a Spanish university setting: interpersonal differences. Revista Psicodidáctica 17, 5–26.

Balta, E. (2018). The relationships among writing skills, writing anxiety and metacognitive awareness. J. Educ. Learn. 7, 233–241. doi: 10.5539/jel.v7n3p233

Basoz, T., and Erten, I. (2019). A qualitative inquiry into the factors influencing EFL learners in-class willingness to communicate in English. Novitas R. 13, 1–18. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1214141.pdf.

Bensalem, E. (2018). Foreign language anxiety of EFL students: examining the effect of self-efficacy, self-perceived proficiency and sociobiographical variables. Arab World English J. 9, 38–55. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol9no2.3

Bhatt, R. (2021). World Englishes. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 30, 527–550. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.30.1.527

Botes, L., Dewaele, J., and Greiff, S. (2020). The power to improve: effects of multilingualism and perceived proficiency on enjoyment and anxiety in foreign language learning. Eur. J. Appl. Linguist. 8, 279–306. doi: 10.1515/eujal-2020-0003

Cabrara-Solano, P., Gonzales-Torres, P., Solano, L., Castillo-Cuesta, L., and Jimenez, J. (2018). Perceptions on the internal factors influencing EFL learners: a case of Ecuadorian children. Int. J. Instr. 12, 366–380. doi: 10.29333/iji.2019.12424a

Cheng, Y. S. (2004). A measure of second language writing anxiety: scale development and preliminary validation. J. Second. Lang. Writ. 13, 313–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2004.07.001

Cheng, X., and Liu, Y. (2022). Student engagement with teacher written feedback: insights from low-proficiency and high-proficiency L2 learners. System 109:102880. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2022.102880

Choi, N., No, B., Hung, S., and Lee, S. (2019). What affects middle school students’ anxiety in the EFL context? Evidence from South Korea. Educ. Sci. 9:39. doi: 10.3390/educsci9010039

Daly, J., and Miller, M. (1975). The imperial development of an instrument to measure writing apprehension. Res. Teach. Engl. 9, 242–249.

Daqar, R. (2018). Diglossic aphasia and the adaptation of the bilingual aphasia test to Palestinian Arabic and modern standard Arabic. J. Neurolinguistics 47, 131–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroling.2018.04.013

Dar, M., and Khan, I. (2015). Writing anxiety among public and private sectors Pakistani undergraduate students. Pak. J. Gender Stud. 10, 157–172. doi: 10.46568/pjgs.v10i1.232

Dewaele, J.-M., and Al Saraj, T. (2015). Foreign language classroom anxiety of Arab learners of English: the effect of personality, linguistic and sociobiographical variables. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 5, 205–230. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2015.5.2.2

Diab, N. (1996). The transfer of Arabic in the English writings of Lebanese students. ESP 18, 71–83.

Elnadi, M., Gheith, M., and Farag, T. (2020). How does the perception of entrepreneurial ecosystem affect entrepreneurial intention among university students in Saudi Arabia? Int. J. Entrep. 24, 1–15. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mohamed-Gheith/publication/344079864_HOW_DOES_THE_PERCEPTION_OF_ENTREPRENEURIAL_ECOSYSTEM_AFFECT_ENTREPRENEURIAL_INTENTION_AMONG_UNIVERSITY_STUDENTS_IN_SAUDI_ARABIA/links/5f534467458515e96d2ef24a/HOW-DOES-THE-PERCEPTION-OF-ENTREPRENEURIAL-ECOSYSTEM-AFFECT-ENTREPRENEURIAL-INTENTION-AMONG-UNIVERSITY-STUDENTS-IN-SAUDI-ARABIA.pdf.

Garcia, M. (2018). Improving students’ writing skills in Pakistan. Eur. Educ. Res. 1, 1–16. doi: 10.31757/euer.111

Golda, L. (2015). Exploring reasons for writing anxiety: a survey. J. English Lang. Liter. Stud. 5, 40–44. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Lilly-Golda/publication/337084415_Exploring_Reasons_for_Writing_Anxiety_A_Survey/links/5dc40fc44585151435efdd70/Exploring-Reasons-for-Writing-Anxiety-A-Survey.pdf.

Goodfellow, R. (2004). Online literacies and learning: operational, cultural and critical dimensions. Lang. Educ. 18, 379–399. doi: 10.1080/09500780408666890

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., and Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. Mod. Lang. J. 70:125. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1986.tb05256.x

Jaleel, A., and Rauf, S. (2023). Exploring the causes of English writing anxiety: a case study of undergraduate EFL learners. Pak. Multidiscip. J. Arts Sci. 4, 1–9. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.7498725

Jang, S., and Choi, S. (2014). Validating the second language writing anxiety inventory for Korean college students. Education. 59, 81–84. doi: 10.14257/astl.2014.59.18

Jebreil, N., Azizifar, A., Gowhary, H., and Jamalinesari, A. (2015). A study on writing anxiety among Iranian EFL students. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. English Liter. 4, 68–72. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.4n.2p.68

Jeon, E. (2018). The effect of learner-centered EFL writing instruction on Korean university students’ writing anxiety and perception. TESOL Int. J. 13, 100–112.

Kabigting, R., Gumangan, A., Vital, D., Villanueva, E., Moseuela, E., Muldong, F., et al. (2020). Anxiety and writing ability of Filipino ESL learners. Int. J. Linguist. Liter. Transl. 3, 126–132. doi: 10.32996/ijllt.2020.3.7.14

Karr, J., and White, A. (2022). Academic self-efficacy and cognitive strategy use in college students with and without depression or anxiety. J. Am. College Health. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2022.2076561

Kasana, S.S. (2022).Saudi Arabia’s vision 2030: a catalyst for realizing women’s rights. The Geopolitics. Available at: https://thegeopolitics.com/saudi-arabias-vision-2030-a-catalyst-for-realizing-womens-rights/.

Khatter, S. (2019). An analysis of the most common essay writing errors among EFL Saudi female learners (Majamaah university). Arab World English J. 11, 364–381. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1271716.pdf.

Kim, M., Tian, Y., and Crossley, S. A. (2021). Exploring the relationships among cognitive and linguistic resources, writing processes, and written products in second language writing. J. Second. Lang. Writ. 53:100824. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2021.100824

Kimberg, D. Y., D'esposito, M., and Farah, M. J. (1997). Cognitive functions in the prefrontal cortex—working memory and executive control. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 6, 185–192. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.ep10772959

Kramsch, C., and Hua, Z. (2016). “Language, culture and language teaching” in Routledge handbook of English language teaching. ed. G. Hall (Albingdon: Routledge), 38–50.

Krashen, S. D. (1987). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall International.

Kusumaningputri, R., Ningsih, T. A., and Wisasongko, W. (2018). Second language writing anxiety of Indonesian EFL students. Lingua Cult. 12, 357–362. doi: 10.21512/lc.v12i4.4268

Lalasz, C. B., Doane, M. J., Springer, V., and Dahir, V. (2014). Examining the effect of prenotification postcards on online survey response rate in a graduate sample. Surv. Pract. 7, 1–7. doi: 10.29115/SP-2014-0014

Lang, P. J. (1971). “The application of psychophysiological methods to the study of psychotherapy and behavior modification” in Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change. eds. A. E. Bergin and S. L. Garfield (Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley), 75–125.

Lawshe, C. H. A. (1975). Quantitative approach to content validity. Pers. Psychol. 28, 563–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x

Li, Z., Cheng, K., and Yi, Z. (2018). Confirmatory factor analysis of second language writing anxiety inventory. Advances Glob. Educ. Res. 2, 241–249. Available at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/216960115.pdf#page=241.

Liu, H.-J., and Chen, T.-H. (2013). Foreign language anxiety in young learners: how it relates to multiple intelligences, learner attitudes, and perceived competence. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 4, 932–938. doi: 10.4304/jltr.4.5.932-938

MacArthur, C. A., and Philippakos, Z. A. (2023). Writing instruction for success in college and in the workplace. New York: Teachers College Press.

Madigan, R., Linton, P., and Johnson, S. (2013). “The paradox of writing apprehension” in The science of writing. Eds. R. Madigan, P. Linton, and S. Johnson (Albingdon: Routledge), 295–307.

McCroskey, J. (1970). Measures of communication-bound anxiety. Speech Monographs 37, 269–277. doi: 10.1080/03637757009375677

Min, L., and Rahmat, N. (2014). English language writing anxiety among final year engineering undergraduates in University Putra Malaysia. Adv. Lang. Liter. Stud. 5, 102–106. doi: 10.7575/aiac.alls.v.5n.4p.102

Mohebi, S., Sharifirad, G., Botlani, S., Matlabi, M., and Rezaeian, M. (2012). The effect of assertiveness training on student’s academic anxiety. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 62, 38–41. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22768456/.

Nambiar, R., and Anawar, N. (2017). Integrating local knowledge into language learning: a study on the your language my culture (YLMC) project. Arab World English J. 8, 167–182. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol8no4.11

Nguyen, T. (2017). Integrating culture into language teaching and learning: learner outcomes. Read. Matrix 17, 145–154. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1139372.

Nugroho, A., and Ena, O. (2021). Writing anxiety among EFL students of John senior high school. J. English Lang. Teach. Learn. Linguist. Liter. 9, 245–259. Available at: https://ejournal.iainpalopo.ac.id/index.php/ideas/article/view/1885.

Ocak, G., and Olur, B. (2018). The scale development study on foreign language speaking self-efficacy. Eur. J. Foreign Lang. Teach. 3, 50–60. doi: 10.46827/ejfl.v0i0.1441

Ozer, O., and Akcayoglu, D. (2021). Examining the roles of self-efficacy beliefs, self-regulated learning and foreign language anxiety in academic achievement of tertiary EFL learners. Participat. Educ. Res. 8, 357–372. doi: 10.17275/per.21.43.8.2

Pew Research Center . (2016). America’s shrinking middle class: A close look at changes within metropolitan areas. Washington, DC: PRC

Pilotti, M. A. E., Al-Mulhem, H., El Alaoui, K., and Waked, A. (2024). Implications of dispositions for foreign language writing: the case of the Arabic-English learner. Lang. Teach. Res. doi: 10.1177/13621688241231453

Pilotti, M. A. E., and Waked, A. (2024). The fading of cultural dispositions in a globalized environment. Int. J. Interdiscip. Cult. Stud. 19, 57–80. doi: 10.18848/2327-008X/CGP/v19i01/57-80

Pilotti, M. A. E., Waked, A., El Alaoui, K., Kort, S., and Elmoussa, O. J. (2023). The emotional state of second-language learners in a research writing course: do academic orientation and major matter? Behav. Sci 13:919. doi: 10.3390/bs13110919

Quvanch, Z., and Na, K. (2022). Evaluating Afghanistan university students’ writing anxiety in English class: an empirical research. Cogent Educ. 9, 1–26. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2022.2040697

Rao, P. (2019). The role of English as a global language. Res. J. English. 4, 65–79. Available at: https://www.rjoe.org.in/Files/vol4issue1/new/OK%20RJOE-Srinu%20sir(65-79)%20rv.pdf.

Sarason, I., Sarason, B., and Pierce, G. (1990). Anxiety, cognitive interference, and performance. J. Soc. Behav. Pers. 5, 1–18.

Scott, M., and Tucker, G. (1974). Error analysis and English-language strategies of Arab students. Lang. Learn. 24, 69–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1974.tb00236.x

Singh, M. (2019). Academic reading and writing challenges among international EFL master’s students in a Malaysian university: the voice of lecturers. J. Int. Stud. 9, 972–992. doi: 10.32674/jis.v9i3.934

Sridhar, S., and Sridhar, K. (2018). A bridge half-built: towards a holistic theory of second language acquisition and world Englishes. World Englishes 37, 127–139. doi: 10.1111/weng.12308

Taherdoost, H., Sahibuddin, S., and Jalaliyoon, N. (2014). Exploratory factor analysis: concepts and theory. Adv. Appl. Pure Math. 27, 375–382. Available at: https://hal.science/hal-02557344/file/Exploratory%20Factor%20Analysis%3B%20Concepts%20and%20Theory.pdf.

Tahsildar, N. (2019). The relationship between Afghanistan EFL students’ academic self-efficacy and English language speaking anxiety. Acad. J. Educ. Sci. 3, 190–202. doi: 10.31805/acjes.636591

Tian, S., and Mahmud, M. (2018). A study of academic oral presentation anxiety and strategy employment of EFL graduate students. Indonesian J. EFL Linguist. 3, 149–170. doi: 10.21462/ijefl.v3i2.78

Waked, A., El Alaoui, K., and Pilotti, M. A. E. (2023). Second-language writing anxiety and its correlates: a challenge to sustainable education in a post-pandemic world. Cogent Educ. 10, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2023.2280309

Xu, L., Wang, Z., Tao, Z., and Yu, C. (2022). English-learning stress and performance in Chinese college students: a serial meditation model of academic anxiety and academic burnout and the protective effect of grit. Front. Psychol. 13:1032675. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1032675

Yaikhong, K., and Usaha, S. (2012). A measure of EFL public speaking class anxiety: scale development and preliminary validation and reliability. Engl. Lang. Teach. 5, 23–35. doi: 10.5539/elt.v5n12p23

Keywords: writing anxiety, English as a foreign language, SLWAI, education and culture, Saudi Arabian education, writing education

Citation: Waked AN, El-Moussa O, Pilotti MAE, Al-Mulhem H, El Alaoui K and Ahmed R (2024) Cultural considerations for the second language writing anxiety inventory: Saudi Arabian female university students. Front. Educ. 9:1288611. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1288611

Received: 25 October 2023; Accepted: 19 March 2024;

Published: 09 April 2024.

Edited by:

Douglas F. Kauffman, Medical University of the Americas – Nevis, United StatesReviewed by:

Sha Luo, Shenzhen University, ChinaCopyright © 2024 Waked, El-Moussa, Pilotti, Al-Mulhem, El Alaoui and Ahmed. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Arifi N. Waked, amohammedwaked@pmu.edu.sa

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.