- Critical Studies in Sexualities and Reproduction, Rhodes University, Makhanda, South Africa

Introduction: Research on school-based sexuality education in South Africa, taught within Life Orientation (LO), has mainly focused on learners’ responses, how teachers approach the subject, and the curriculum content. Critiques have included heteronormative biases, an emphasis on danger, disease and damage, a reinforcement of gendered binaries, and the lack of pleasure or well-being discourses. In contrast, our research focused on the unexpected moments teachers experience, i.e., the ethical, emotional or psychological challenges they encounter in their interactions with learners.

Methods: We interviewed 49 teachers across a range of schools in three provinces. Data were analyzed using narrative thematic analysis.

Results: Teachers’ narratives referred to an alarming array of traumas and psychosocial problems experienced by learners, including sexual abuse, substance abuse, neglect, HIV diagnosis, unsafe abortion, witnessing murders, and attempted suicide. Teaching particular topics, they indicated, triggered learner distress, although, sometimes, distress was triggered by innocuous topics. Teachers felt insufficiently skilled to teach certain topics sensitively to promote the well-being of learners who experienced current or past trauma. They also felt ill-equipped to deal with learners reporting trauma or psychosocial problems to them. Strategies narrated included allowing learners to skip relevant classes, building trust, understanding learners’ needs, being a learner’s advocate, and drawing on learners’ grounded expertise. Teachers spoke of experiencing burnout and secondary trauma themselves.

Discussion: We argue that LO teachers are, in effect, sexual, reproductive and mental health frontline workers. They need in-depth training in learner-centered and dialogical approaches to build trust within the classroom sensitively and in basic screening, containment, referral and lay counselling skills to assist distressed learners outside the class. A wellbeing approach to sexuality education requires providing LO teachers with ongoing support and consultation with peers and mental health professionals to avoid burnout and promote well-being.

Introduction

Research conducted on school-based comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) in South Africa tends to focus on the content of the curriculum (e.g., Macleod, 2009; Macleod et al., 2015), learners’ responses to the lessons (Ngabaza et al., 2016; Adekola and Mavhandu-Mudzusi, 2023) and how teachers approach the teaching of sexuality education (e.g., Francis and Depalma, 2015; Saville Young et al., 2019), including for learners with disabilities (e.g., Hanass-Hancock et al., 2018). In line with international trends (Fine, 1988; Fine and McClelland, 2006), researchers have called for a balanced focus on pleasure (Bhana and Anderson, 2013) and learner-centered approaches (Jearey-Graham and Macleod, 2017; Ngabaza and Shefer, 2019).

In South Africa, comprehensive sexuality education forms part of the learning area, Life Orientation (LO). Research focusing specifically on LO teachers shows that they find it challenging to create an open dialogue regarding sexuality (Francis, 2010; Shefer and Macleod, 2015). Many experience discomfort tackling topics such as LGBTI issues (Francis and Reygan, 2016; Francis, 2019) and equal gendered norms (Ngabaza et al., 2016; Saville Young et al., 2019).

Little attention has been paid, however, to the multiple roles LO teachers may be called upon to perform, including confidante, counselor, and social worker (Helleve et al., 2011). These teachers may need to engage in care work with learners concerning various issues relating to sexuality, including HIV, pregnancy, and sexual violence. While this kind of care work does not fall within the ambit of the curriculum, it is nevertheless important in light of the multiple sexual and reproductive challenges facing learners (Wood and Rolleri, 2014). Such labor assists in cushioning learners from potential trauma (Shefer et al., 2013).

In this study, we aimed to address the following questions: In relation to what sexual and reproductive issues do LO teachers encounter ethical, emotional or psychological challenges (both within and outside of the classroom)? How do LO teachers currently address such challenges? While our initial intention was to highlight sexual and reproductive issues, the interviews surfaced a far broader spectrum of problems, as shown below.

Background

Comprehensive sexuality education in South Africa

Sexuality Education was introduced in South Africa as part of the new LO curriculum in the late 1990s. Its initial focus was predominantly on HIV prevention, and it generally took an abstinence+ approach – abstinence as the most desirable outcome, with faithfulness and condom use tacked on should abstinence fail (Francis and DePalma, 2014). Recently, however, there has been a move towards a rights-based comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) approach, encouraged by the government’s signing on to various international and regional commitments, treaties, legislation, and policy (Ngabaza, 2021). Scripted lesson plans were introduced for CSE in 2020. While some matters are not addressed (for example, learners’ rights under South African legislation to request an abortion in the first trimester of pregnancy), they are a substantial improvement on what was available before (Ngabaza, 2021).

Researchers note the potential of LO to transfer vital social skills to young people, especially in a country wracked by a range of social problems (Shefer and Macleod, 2015) – see discussion below. CSE is viewed as a potential modifier of oppressive norms and attitudes (Francis, 2010; Bhana et al., 2019). However, while this potential is understood, it is widely argued that LO is not fulfilling this mandate for various reasons. The most significant factors focused on are the failings of LO teachers (Ahmed et al., 2009; Helleve et al., 2009; Francis and DePalma, 2014) and the lack of training they have to teach the subject (Pillay, 2012; Bhana, 2016; Jimmyns and Meyer-Weitz, 2020). While it is possible to receive LO-specific teacher training at the university level, it is only provided by some South African universities. Even these tend to neglect the subject in favor of others (Ngabaza, 2021).

Social indicators and trauma in South Africa

Life Orientation teaching occurs in a context where “life” is precarious and vulnerable. According to the World Population Review, South Africa has the third-highest murder rate in the world, at 76.86 per 100,000 people in the population.1 Crimes are frequently violent, with high rates of assaults, rape, and homicides. Several factors have been implicated, including “high levels of poverty, inequality, unemployment, and social exclusion, and the normalization of violence” (see footnote 2).

Violence against women, in particular, has been in the spotlight in recent years. According to the Demographic and Health Survey conducted in 2016 (National Department of Health, Statistics South Africa, South African Medical Council, and ICF, 2019), one in four (26%) ever-partnered (cisgender) women age 18 or older have experienced physical, sexual, or emotional violence committed by a partner in their lifetime. As noted by Sibanda-Moyo et al. (2017), violence against women “feeds on and induces multiple vulnerabilities” (p. 5).

Researchers, policymakers and funders recognize the traumatizing effects of these high levels of crime and violence, along with other social problems, such as high rates of HIV, child-headed households, drug and alcohol misuse, socio-economic inequalities, and high unemployment. For example, Wyatt et al. (2017) report on the Phodiso Programme, an international collaboration between universities in South Africa and the University of California, Los Angeles, with the aim of “focusing on minimizing the negative health and mental health effects of trauma exposure, particularly depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)” (p. 249). In sum, South Africa is a traumatized society in relation to the legacy of apartheid and current levels of violence, crime, inequalities, unemployment, and other social factors.

Outline of the research study

The study’s overarching aim is to contribute towards improving pre-service and in-service training and support for LO teachers, specifically in teaching CSE and in responding to learners’ psychosocial problems. To do so, the following research questions were posed: (1) In relation to what psychosocial issues do teachers encounter ethical, emotional or psychological challenges? (2) How do teachers currently address such challenges within (a) the teaching of LO-based sexuality education and (b) outside the classroom?

The study took a narrative approach. In this approach, the researchers analyze “particular instances, sequences of action [and] the way participants negotiate language” (Riessman, 2011, p. 311). Allowing teachers to tell stories of their challenges and how they have responded to, coped, and dealt with them elicited rich, grounded data.

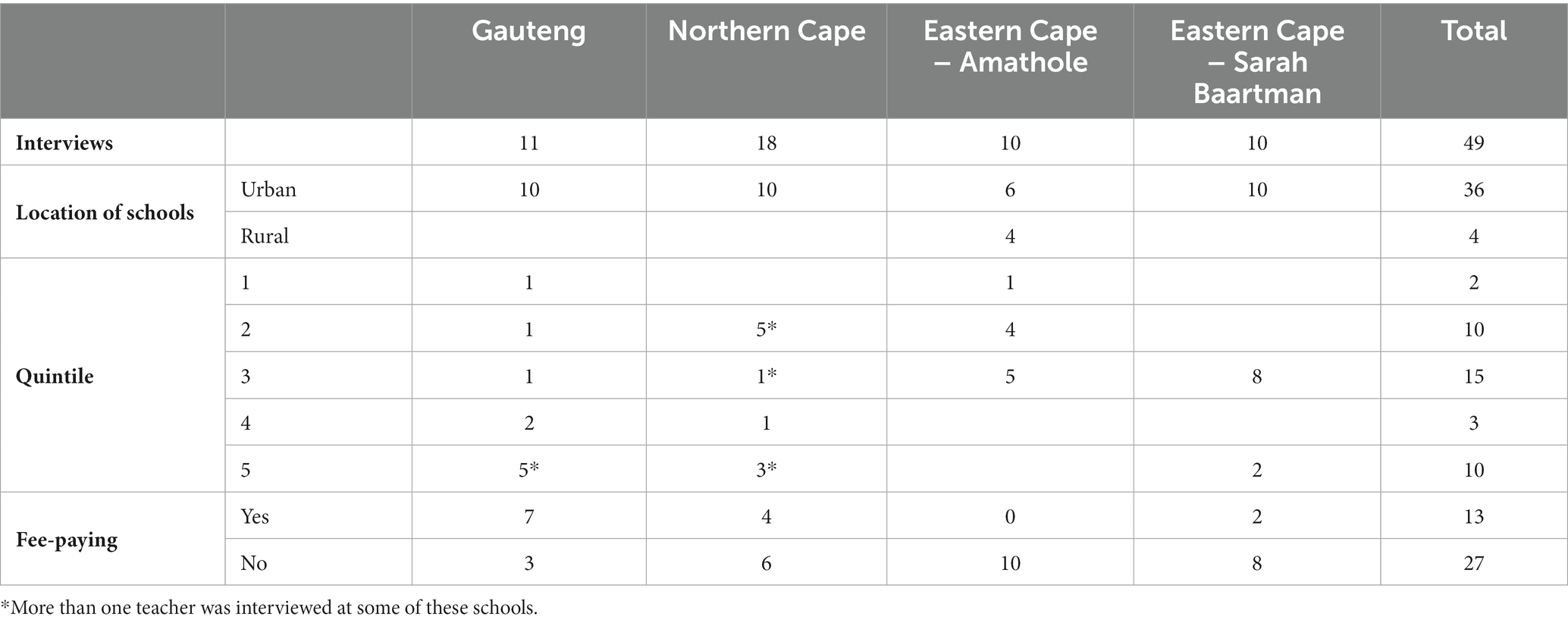

We conducted 49 in-depth narrative interviews with LO teachers working in 40 schools across three South African provinces: Eastern Cape, Northern Cape and Gauteng. This number, considered sufficient for in-depth qualitative interviews, was determined by available funding. Schools were sampled to ensure diversity between quintiles. The DBE considers a community’s income, literacy and unemployment levels when allocating quintile categories (1–5) to schools. Quintiles 1–3 schools are non-fee paying, while quintiles 4 and 5 are fee-paying.

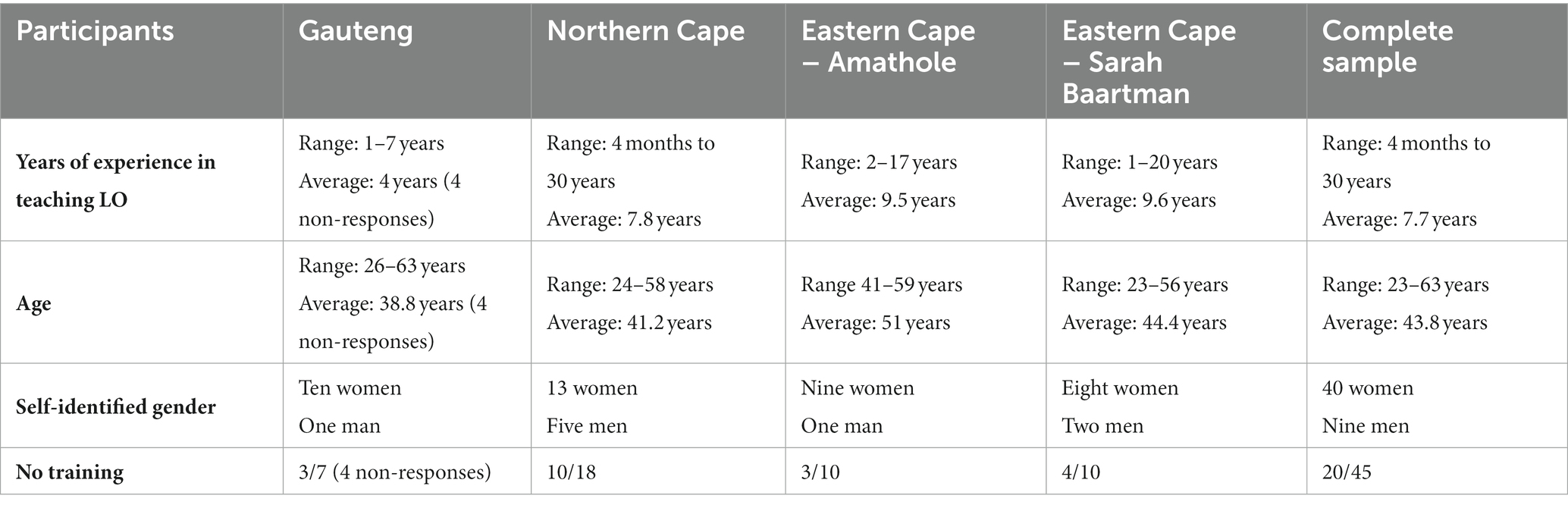

Only public secondary schools were sampled. There was also an attempt to balance rural and urban schools, at least in the Northern and Eastern Cape provinces (Gauteng is largely urban). However, rural schools tended to be less responsive during our recruitment attempts than urban schools (possibly because of connectivity problems), and there were limited schools to recruit in these areas. Ten schools were sampled in Johannesburg, Pretoria and Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipalities in Gauteng. Ten schools were sampled from the Frances Baard District Municipality in the Northern Cape. Twenty schools were sampled in the Eastern Cape: ten from the Amathole District and ten from the Sarah Baartman District. The final sample resulted in more no-fee than fee-paying schools (27 versus 13). This weighting aligns with the fact that about two-thirds of learners attend no-fee schools (Businesstech, 2021). Where schools had more than one LO teacher, all were interviewed where possible. Table 1 outlines the study sample, and Table 2 outlines the sample demographics (four participants did not share their demographic details in Gauteng). Experience in teaching LO varied amongst participants from 4 months to 30 years. On average, however, the participants have a good foundation of experience they could draw on in discussing CSE and LO’s challenges and possibilities.

Of the 45 teachers for whom we collected demographic data, 20 indicated they had not received any training in LO. Some indicated they were tasked with teaching LO because of their lower workload or because their second subject was not taught at the school. The training received by those who indicated they had been trained included workshops conducted by the Department of Basic Education (DBE), having done Psychology or Sociology as part of a degree, an Advanced Certificate in Education, or a Post-Graduate Certificate in Education. Informal training included sessions with social workers or psychologists, and self-teaching, particularly through digital media like YouTube.

Teachers were given the option of being interviewed in their preferred language. The questions posed in the interview invited teachers to relate stories about incidences in which ethical, emotional or psychological challenges arose and how they dealt with each of these challenges. The interviews were conducted by four female fieldworkers trained by the authors. Each fieldworker resides in the province in which they collected data. This was partially because of funding, but also to draw on their local knowledge of schooling conditions.

The interviews were recorded and transcribed, and, where necessary, translated. The majority of interviews were conducted in English, with some in isiXhosa. The data in English were transcribed verbatim, while the data in isiXhosa were transcribed and then translated. Each of these transcripts was checked by an independent bilingual person for accuracy after transcription and translation were completed. Importantly, isiXhosa does not discriminate between male and female pronouns (e.g., “she” or “he” is represented by “u”). We use “they” in these instances.

The interviews were analyzed using narrative thematic analysis (Riessman, 2008). While narrative analyses tend to focus on how a narrative is told, to whom, or for what purposes, narrative thematic analysis is concerned only with what is said. Narrative thematic analysis differs from other thematic analyses in how it codes data. Narrative thematic coding keeps stories intact by using narrative block coding. These narrative blocks encompass a narrative unit defined as a bounded segment about a single incident (Riessman, 2008). Once coding is completed, narrative themes are developed. The two authors were involved in this process. The thematic approach to narrative analysis is popular, especially where experiences in applied settings are valued.

A full ethics protocol served at the Rhodes University Research Ethics Committee – Human Participants. Standard principles of informed consent, anonymity, and data security were applied. A key ethics concern was providing support for teachers if they disclosed sensitive information (e.g., disclosure of sexual violence) of a current learner or if they became distressed in the interview. As this research was conducted under the guidance of the Department of Basic Education, necessary arrangements for follow-up were made regarding, firstly, personal counseling in the case of distress and, secondly, internal mechanisms needed to deal with the disclosure of sensitive information. However, no teacher needed or requested immediate counseling for distress during the study. Neither did they speak to current cases that needed resolution. They did, however, express the need for ongoing support. This is spoken about in the conclusion. Teachers chose or were provided with pseudonyms.

Findings

The findings from this study are presented under three broad thematic areas: narratives of the challenges faced, narratives of strategies used to overcome the challenges, and narratives of personal pain. In the first, the challenges, the following narrative themes emerged: learners present with many psychosocial problems; the content of lessons triggers learners; and we (teachers) struggle to deal with triggering topics or triggered learners. In the second thematic area, strategies used, the following narratives emerged: “She (learner) trusted me (teacher)”: building trust; “I must attend to them”: understanding the learners and responding to their needs; “She (learner) helped me (teacher) with the lesson”: drawing on learners’ expertise, and being the child’s advocate. The third theme consists of one narrative - “It is getting too much”: carrying learners’ pain.

Narratives of the challenges faced

Learners present with many psychosocial problems

In speaking to the question of the challenges they encountered, teachers mentioned many psychosocial problems learners face. These were raised in the context of both in-class and out-of-class interactions, as illustrated below.

Now you know sometimes, when you give these lessons, some learners have experienced these things. Maybe you touch on the point of unplanned pregnancy. Maybe some of the learners already have kids. Now when you give this lesson, it seems like you are addressing them specifically. So, you must be very sensitive now again. You cannot go deeper into this topic because, somehow, you feel like you are being inconsiderate if you do that. Inconsiderate of that learner’s feelings, you understand? You must pull back a bit. But when you do that, you are disadvantaging others (Kay).

Then the child fell pregnant, and when they asked who the father was, they told them that the priest was the father. So, I asked the mother why they did not report it … the parent told me there was an agreement between the priest’s family and their family. They told me that the priest’s family agreed to support the child (Themba).

Kay starts her narrative by indicating that the content of CSE mirrors the problems learners face, then uses unplanned pregnancies as an example. She recognizes the stigmatizing effects of the standard LO narrative – “do not become pregnant while at school” – may have on a pregnant or parenting learner. She describes trying to deal with the dilemma sensitively by separating general discussion from the person of the pregnant learner. Themba relates an out-of-class interaction in which she uncovered transactional sex sanctioned by the family. Transactional sex is not uncommon in South Africa and is recognized as a critical survival strategy for some (Potgieter et al., 2012; Shefer et al., 2012).

Interweaved into the narratives told by teachers were a myriad of psychosocial problems, including sexual abuse, incest, rape, transactional sex, coercive sex, alcohol and drug abuse in the home, neglect and abandonment, broken family relationships, learners taking on caregiving for sick family members, domestic violence, child-headed households, unfiltered pornography, pedophilia, child hunger, misuse of grant funds, murder accusations, bereavement, including deaths in the family, witnessing a murder, drug and alcohol use in the school, menstrual shaming, vandalism, violence, bullying, learner-to-teacher sexual harassment, learners with special needs, including those with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, depression, anxiety, attempted suicide, unsafe termination of pregnancy, learners receiving HIV-positive diagnoses; learners living with HIV, claims of teachers using witchcraft, and death threats against learners As with many social issues, the cases spoken to were often complicated. For example, in one case, a learner was going hungry because their mother was an alcoholic. In another, the teacher suspected incest when the learner attempted suicide.

Learners are triggered by the contents of lessons

Given the wide range of psychosocial problems facing learners, it is unsurprising that a significant narrative theme raised by teachers was teaching topics that triggered emotional responses from learners.

For example, there’s a child even now here at school who burst into tears in class when we were discussing a poem about rape, only to discover that they2 were raped. It was also not a recent rape case; it happened some time ago. They could not cope in class (Bulumko).

It was a girl learner, and we were talking about rape. When we were talking about rape, I noticed that this girl was emotional – they were crying – and I finished my lesson, and after the lesson, I called the learner, and we talked about it. And then they told me their story that they were raped. And no one knows about it, even their parents (Anele).

Rape is, of course, never an easy topic of discussion. These teachers speak, however, to how the discussion produced more than usual emotional responses from a particular learner. In each of the extracts above, the teacher narrates how discussing rape led to a learner revealing that they had been raped. In Bulumko’s story, the effects of the rape are long-term, while in Anele’s rendition, the teacher is the first person to whom the learner has confided about the rape.

While discussing rape directly as a topic may be expected to lead to emotional responses from learners who have been raped, seemingly innocuous topics may also lead to an emotional response.

I told them to visualize and close their eyes while they were sitting, and after 5 min, I took them to that place that is near the river, sitting on the tree and reading their favorite book in peace. I noticed that in the middle of that there is a pupil who stood up and left the class. After that, she told me that she was raped, and she was raped next to a tree. She said the exercise took her back to that night (Thobile).

Here, the visualization activity proposed by Thobile is framed in positive terms – peace, favorite book. However, this triggered a memory for a learner about the rape she had experienced.

As noted above, crying or leaving a classroom are key indicators of distress. Teachers said, however, that they need to be alert about more subtle cues regarding learners being triggered by the content of lessons.

Sometimes I would notice a change in behavior. For instance, a learner who’s normally bubbly and active but suddenly, when I deal with this topic of cyberbullying, they become sort of reserved. And from time to time, I’d expect them to say something because they are not usually quiet throughout the lesson, but suddenly (they become quiet) (Nomlanga).

Some kids actually cage. Do you know when we are saying you are a cage? And it is not easy because I do not know how to speak to this child. … I do not know. This one has a lot of anger, this one is a happy child, but after 2 min, this child is changing again (Amahle).

Here teachers discuss a key indicator that a topic is causing a learner distress – a change in usual behavior. In contrast to the previous extracts, Amahle speaks about the difficulty of engaging with learners triggered by a topic, using the metaphor of a cage.

We struggle to deal with triggering topics or triggered learners

Teachers bemoaned their lack of ability to, firstly, teach topics in a way that does not lead to emotional distress and, secondly, deal with the emotional distress their learners exhibit when triggered by particular topics.

Many teachers expressed concern that they are not skilled enough to teach certain topics such that a learner with past traumatic experiences would benefit instead of being triggered.

So when I’m not connecting with each and everyone, I feel like there’s someone or there’s a learner that I’m busy crushing. … because you, you, you in a class of, of 40 people, you cannot really connect. Someone you’ll think they are quiet because they are quiet, kanti (whereas) you are maybe opening the old wounds (Thabiso).

We have different learners of different ages, so I was told that most of the learners are victims of rape [inaudible] the father is not’ [inaudible]. … So, the learners will ask questions, and I will look at that learner, but she or he does not know that I know [about the previous trauma]. So, for me, it would be difficult to go in-depth because I must think of touching the sensitive parts of the feelings of that specific learner (Monica).

These teachers relay their fears of creating distress in their classes. Thabiso uses a heart-rending description: “a learner that I’m busy crushing.” She ascribes her inability to connect with all the learners to the class size. Monica, similarly, speaks of the difficulty of discussing topics in-depth, citing knowledge of learners with past traumas and not wanting to touch “the sensitive part of the feeling of that specific learner.”

Where learners do confide in the teacher about past trauma (as illustrated in the section above), teachers may not be equipped to contain the learner and put relevant action in place.

And it is not easy because I do not know how to speak to this child. I’ve never been trained, you know? I know how to transfer the knowledge to you, but now, how do I get you to a comfortable space, you know? That’s what most teachers struggle with – getting a learner to be in a comfortable space … and you are thinking, I do not want to say the wrong thing, and then this child is going to be triggered, and then they cry, and then I do not know what to do. So, it is not easy, but I try my best, and I really do my best (Amahle).

Amahle speaks poignantly about her desire to assist a learner who has confided in her. However, her ability to “get [them] to a comfortable space” is limited by her anxiety about saying the wrong thing (thereby making the situation worse) and her lack of training in how to go about engaging the learner in these circumstances.

Narratives of strategies used

Despite teachers indicating that they struggled to teach particular topics or approach distressed learners sensitively, many spoke of helpful ways of dealing with these issues. Teachers were at pains to indicate that sexuality education is not similar to other subjects and that specific pedagogical spaces must be fostered for CSE to succeed. The narratives that emerged under this theme included: she trusted me, understanding the learners and responding to their needs, drawing on learner experience and expertise, and advocating for the learner. Another strategy spoken to was allowing learners to choose. We outline why the latter strategy may not be constructive.

She trusted me

Several teachers spoke about the importance of trust.

They trusted me, and I had to follow those steps to sort of try and sort it out… So, learners need teachers who are open when it comes to LO so that learners can also open up. I was here only two terms when I had that conversation with them on sexuality. Then they were like, “Okay, I think we can trust this teacher. We can ask questions.” … They are confident to come up to the teacher (Akhona).

Most of the kids that are sexually active will come to me because they feel mostly comfortable with me as an LO teacher (Nomthandazo).

These teachers talk about the importance of trust in terms of learners opening up about issues and asking questions. Akhona intimates that there is a cross-over between sensitivity in teaching about sexualities in the classroom and learners feeling comfortable about approaching them outside the class.

Establishing trust is a process referred to by Lindiwe below.

So that girl came to the office and told me that she came to me because she spoke to her friends but thought it would be better if she spoke to me because maybe I would be able to help her. I asked her what her problem was and she told me she’s HIV positive. I asked her where she got the disease from, and she said the person she was in a relationship with. She was expecting me to be shocked by what she was telling me, so when she saw that I was not screaming, but I was calm…. Every time we bump into each other, she says, “Here’s the teacher that helped me,” and I’d say “I told you it would just be us two (who knew)” (Lindiwe).

Lindiwe alludes to the learner expecting “screaming” from the teacher when she disclosed her HIV status. The teacher’s calm and nonjudgmental attitude enabled the learner to divulge her fears (which was the start of a conversation towards acceptance and positive living – not shown in the extract). Apart from being nonjudgmental, Lindiwe emphasized confidentiality, which, according to her, led to a positive outcome.

Trust in LO teachers could have broader effects than just containing and assisting the learner, as related below.

We were doing a topic on relationships… and so this learner came up to me, confessing and affirming what I was saying about broken relationships. They told me that their teachers did not understand them. … I told them, “You’ve got to share. You must not bottle up.” So, they shared that they had a psychological problem, which is depression and anxiety disorder … initially, I had to get permission from the learner that they would like me to share with the principal and the school managers so that this filters down to all teachers so that through them, maybe we could learn a new way of looking and understanding the corners that learners find themselves in (Nomlanga).

Nomlanga relates how, with permission, she used this learner’s experiences with mental health struggles to conscientize the other teachers about this particular learner and other learners and the “corners [they] find themselves in.” It is important to note Nomlanga’s respect for learners’ privacy (asking for permission), which is paramount to fostering trusting relationships.

“I must attend to them”: understanding the learners and responding to their needs

According to various teachers, trust, such as spoken to above, comes from understanding and responding to learners’ needs.

I leave the child to cry and give them a tissue, and I check up on them to see if they are ready to talk. When they are ready to talk, I let them know that if they are not comfortable talking, they do not have to. However, in cases where they do decide to talk, some allow me to call their parents, and they talk in their presence. Some do not want their parents around, so I’d ask if I should refer them or call a social worker. The child will agree, and I’d have to arrange an appointment with the social worker, but others would not want to and would want it kept between me and them. But I will reassure them that anytime they have a problem, they can come to me. Even the teachers know that if anything happens that needs my assistance, they can pull me out of a class (Anathi).

Anathi speaks of listening and responding to what the learner needs in a crisis. She listens carefully to the learner’s expressed needs and actions, whatever the learner is ready for, including using her (the teacher) as a confidante.

Other than attending to learners’ personal needs, teachers also spoke to understanding the different social positions that learners occupy and needing to adjust teaching to suit these.

When discussing crime or poverty, you need to use real-life examples. When you are using these examples, you need to be sensitive because these kids come from different backgrounds and they come from different communities. You might have a learner coming to class where you do not know that child’s situation. And if you make an example of, say, how it is wrong to use or sell drugs, you are not being sensitive because you may get that there’s a learner that comes from a home that sells drugs to make money so that they can attend school (Amahle).

Amahle argues that the simple story of “drugs are wrong” fails to accommodate households whose only means of income to support school-going children is the drug trade. This understanding serves to nuance a simplistic narrative of “do not do drugs”; instead, the multiple socio-economic pressures put on families, particularly in the inequitable economic distribution that characterizes South African society, is understood and dealt with sensitively.

Teachers spoke to a number of strategies that they used in order to understand and respond to learners’ diverse needs. An important one was the keen observation of behavior.

So what happened is that there is a child without parents, who are living with relatives, right? We noticed this child’s performance went down so we called her aside to check and to try to find out what is going on. We discovered that this child is being taken advantage of by the male relatives she lives with. … Even her aunt who is supposed to be the guardian is mis-using her grant money. So then we contacted the social worker (Fezile).

A few years ago, there was a boy in my class whom I assumed was gay, and he was terribly bullied because of that. … I noticed his body language and a few other kids’ body language in class. I addressed it, and I referred to our human rights as individuals and the right to safety and to not be abused and to be understood and heard and also, which is also included in the LO syllabus, is teaching children tolerance (Adam).

Fezile talks about noticing a difference in a learner’s scholastic performance. Importantly, she knows the learner well – usually she (the learner) achieves at a particular level. This allows her to approach the learner, which leads to the discovery of abuse. Adam talks about his observations regarding the bullying of a learner who identifies as gay. These observations include paying attention to comments made and learners’ body language. Having made these observations, he respond by asserting the rights of gay learners.

Teachers spoke about reflections, including self-reflections, as an important mechanism to foster understanding of learners’ needs.

I’d give them time alone to reflect. And they can write to me and say, “Miss, this is what I wrote.” And most teachers are usually lazy to do this, but I read those reflections because it’s a way to get to know your learners. Once you read it, you know what is happening. This learner goes through this, which is why she behaves this way in class. Then you understand who this person is, you know (Amahle).

You walk into a classroom, and your opinion as a teacher cannot be the thing that guides it all. Do you understand? We’re dealing with diversity. And I mean, if I come from a Christian background, it does not mean there’s someone who does not, who’s an atheist, they have not grown up within a church. I cannot force my ideas and ideologies on that child. It does not matter what it is. I might think that I am right. I’m living a good life. It does not mean that they are not living a good life (Linda).

Amahle uses learner reflections to understand them better. She suggests that this helps her to understand why learners do certain things and who they are. This suggests the development of empathy, which is a good starting point from which to engage learners. Linda, on the other hand, argues for self-reflection about not forcing “my ideas and ideologies on that child.” She justifies this through referring to diversity and advocates for tolerance of different views in the classroom.

“She helped me with the lesson”: drawing on learners’ expertise

A strategy referred to by teachers in dealing sensitively with particular topics was to draw on learners’ expertise in the area.

Once I had to teach about different kinds of STDs, including HIV, knowing that a learner had disclosed to me that she was HIV positive. So that challenged me because I had to talk about HIV in the class, and some of the learners knew that this learner was HIV positive. … Fortunately, the learner was confident because she had contracted the virus from her mother at birth. She did not engage in sexual intercourse to contract it. I do not want to lie. It was difficult at first, but the learner participated in the lesson. I felt at ease because the learner knew exactly what happened to her, and she did not see anything wrong with being HIV-positive … Basically, she helped me with the lesson. Instead of being ashamed of her status, she participated in the lesson and tried to assist me while I was teaching by telling us more about HIV and how to prevent oneself from contracting the virus. She really helped me in that regard. Even though I was the teacher, I learnt a lot from her (Kay).

Cause I remember when I talk about different cultures and the removal of skin, the other boys just chip in there and explain thoroughly what is happening when we talk about the healthy part of the sexual uhm spectrum. That you need to undergo the circumcision. There was a Xhosa boy, they went, who took us through how it is done. It’s not about only about the removal of the skin. It’s something more important (Tebza).

HIV/AIDS can be a sensitive topic with potentially stigmatizing effects should a learner be HIV-positive. Kay speaks about grappling with this, but because of the confidence of the affected learner, the class could benefit from their expertise in this regard. Tebza similarly spoke of using the cultural knowledge of a learner to speak how ulwaluko, the traditional circumcision ritual, is practiced and the meaning thereof. Later in the discussion (not featured in the extract), Tebza spoke to the usefulness of these discussions to promote cultural understanding across the diverse range of populations in South Africa.

Being the child’s advocate

Some teachers spoke about being advocates for the children, as seen below.

I asked her (the girl who reported being raped) what we should do and if the police officer took her to the hospital. She said the police van was called and they told them to find a car to take her. I said, “Okay, this case needs to be escalated.” I asked her for the contact details for the police station. I called them and asked for the person who attended to her and told them I was her teacher, and I would be following the steps that they should have followed. … I then called her mother and informed her that the police officer was on their way to fetch her. … I threatened the police officer that if they did not take this case seriously, the school would sue them. I had not even told the principal at this point. … The mother informed me later that everything went well. She was even seen by a social worker or psychologist (Anathi).

We felt that it needed urgent attention because of the report from his granny that the child isolates himself and does not socialize with others. The child’s performance was poor at school, and he had anger. So, we felt this is urgent because it has affected his academic performance. So, we could not sit back and wait for someone. We did not know when we would get them. And then we had to go back home to suggest to the granny that she asks a neighbor who could accompany this boy to casualty in the hospital. It started being clear from the granny that, no, there was ‘this’ and ‘that’ issue, so I availed myself to stand in for the family, and I would stand in for the school, and I went with the child to the hospital. That’s where the child got assistance. I had to tell them that he was not physically sick, but we felt he needed to talk with a psychologist (Bulelani).

Anathi speaks to a situation where they had to advocate on a learner’s behalf to ensure they received the needed follow-up after a learner reported being raped. In this instance, they perform duties outside their strict job description. In desperation, she threatens the police department with legal action. Bulelani goes to extraordinary lengths to ensure the learner gets the needed assistance. Failing immediate assistance from the social workers, family or neighbors, the teacher accompanies the child to the hospital. In both cases, the teachers felt that police, social services and the family had let the learner down, which required their stepping in as advocates for the learner.

However, teachers’ attempts to advocate for the child have limits. Tswere refers below to the difficulties of interacting with the criminal justice system.

But now, what do I do as a teacher because things like that, where do they fit us? The only best place I can tell the learner to go is to the police. Now, with police officers, they want evidence. Where is the evidence? Evidence is just word of mouth. So, everything ends there. What happens to the learner? What happens to her? You see, eventually, because physically, she’s already hurt. Emotionally, you cannot get help (Tswere).

Tswere taps into the difficulties of getting a rape case prosecuted or sentenced. The conviction rates of rape are low precisely because medical evidence is often unavailable. As indicated by Smythe (2015, p. 4), “Rape attrition studies have shown that a minority of rape victims lay a complaint with the police and only a very small percentage of those cases results in conviction.”

Giving learners the option of non-attendance

Some teachers spoke about dealing with potential triggering by allowing learners to choose whether they attend particular classes.

So, when we reach those topics, then they are given an option of either being in class or not being in class or part of that. So, before we start a section, we always have to say, “We’re gonna start a section that has a sensitive topic, umm sensitive content,” so, and then I’d say what the content is, and then I tell them, “If you need to see me so that you can be in a different venue, please come and see me. This is for the purpose of education – it’s not for the purpose of excluding anyone. So, if you need to make sure that you are not in the lesson, please come, and then I’ll organize a venue for you.” (Sonja).

While the strategy of identifying who may be affected through prior knowledge or an open question in the class and giving them the option of non-attendance is laudable, it is not entirely unproblematic. Teachers are likely unaware of everybody in the school affected by sexual violence (as attested to in previous extracts). Additionally, asking learners to extricate themselves from a class addressing sexual violence makes them reveal an association with sexual violence, which could be stigmatizing.

“It’s getting too much”: carrying learners’ pain

At the beginning of these findings, we outlined a long list of emotional, social and interpersonal traumas and issues with which learners cope. As people living in a traumatized society, LO teachers, likewise, may live with or face several problems. It is not surprising, then, that teachers are emotionally affected by their work.

I will not lie. It did affect me… I feel drained after every case. As a result, when I handle cases, I leave the student in my office and go cry in the bathroom under the guise of going to relieve myself. I always feel like the traumatic things that these kids experience are happening directly to me, and even I cannot handle it. … so it’s times like those that I feel it’s getting too much (Anathi).

Every time you hear something about a learner, it cuts deep. I think when you deal with people, it stays in you because I felt like she did not deserve that (Thobile).

Fatigue was the thing because I’d carry ten kids’ baggage with me. Then by the end of the term, I’m so exhausted because I wonder about those ten kids with their different issues, and I am just burnt out (Adam).

I stay stressed about these cases until the stress fades away, even though I know that stress never just goes away. So, whenever something happens, it triggers the stress that already exists within me (Bulumko).

The language teachers use in these extracts indicate caregiver burnout and secondary trauma. The teachers speak about being “affected” or “drained” by learners’ trauma, “exhausted” and “stressed” in having to deal with the problems, and “crying” to cope. The resonance of the learners’ trauma with the teachers’ own lives is referred to by Anathi (“traumatic things these kids experience are happening directly to me”), Thobile (“it stays in you”) and Bulumko (“triggers the stress that already exists within me”). As a result, they feel less able to perform their work – “it’s getting too much.”

Various teachers spoke about having strategies to deal with the emotional toll of dealing with students’ “baggage.”

If I am being honest with you, I get emotionally invested very quickly … And a lot of the time, you kind of need to switch yourself off from certain things. But it is very difficult, especially when it is something sensitive (Bulumko).

So, I decided I did not want to get in too deep because it’s their family things (Bongiwe).

These things affect us as teachers as well. I simply suppress it. I try not to think about it even though when I see them at school, I do feel their pain. But I try hard to forget about it. I just suppress it. It does remain in my thoughts, so I talk to my mother about it at home and tell them what is happening. Other than that, there is nothing else I do. I do not talk to a psychologist or a counselor or anything like that (Hlumisa).

Bulumko and Bongiwe talk about creating boundaries in their work. Bulumko “switches” off, while Bongiwe decides not to interfere in family affairs. These strategies can be seen as self-preserving, but may come at a cost to learners who are in need of help. Hlumisa talks through her problems with her mother but also speaks of difficulties in “suppressing” the issues. Forgetting is hard for her, and without access to mental health care (psychologist or counselor), the issues “remain in my thoughts.”

Indeed, the problem with carrying the burden of care work is that, without support, it also affects the person’s personal life.

If I am hurt, I have to console myself as there is nobody – no psychologist or counseling or therapy – from any side to come and sort it out. So, those are the support mechanisms that we need, yes (Themba).

We need psychosocial support ourselves. The previous LO teacher left. She actually retired early because of that. She had too many learners who had been raped (Amahle).

Here teachers refer to the consequences of not receiving psychosocial services – having to “console [one]self” and experienced teachers leaving the service owing to burnout. Amahle refers directly to the need LO teachers have for psychosocial support themselves.

Discussion

The LO teachers’ narratives in this study mirror the country’s depressing research regarding violence and many psychosocial problems. These include poverty and inequality (South Africa is the most unequal country globally; World Bank, 2022), crime, drug and alcohol disorders, high levels of violence, especially gender-based violence (GBV), and high levels of HIV/Aids. Integral to these social issues are gender inequality, oppressive gender norms, heteronormativity, and hypermasculinity, much of which are rooted in South Africa’s violent history of colonialism and apartheid (Bhana et al., 2019). Within this context, teachers in our sample recognize the precariousness and vulnerability of many learners. The data point to an astonishingly long list of psychosocial problems learners experience.

Our findings show that teachers are sensitive to the possibility that LO lessons will be distressing for learners, particularly when they touch on topics that resonate with traumas or psychosocial problems the learners have experienced. They (teachers) talk of being alert to changes in learners’ behavior as an indicator of their being distressed by the lesson content. Despite this knowledge, or perhaps because of it, teachers feel ill-equipped to teach sensitive topics in ways that benefit those who have been traumatized or live in difficult circumstances and those who have or do not. Additionally, teachers feel they lack the expertise to deal with learners who report traumatic or distressful circumstances outside the classroom.

Nevertheless, teachers narrated a number of strategies to deal with, firstly, the possibility of triggering learners in the classroom and, secondly, learners who report particular traumatic events or psychosocial problems to them. Some strategies, like building trust and understanding and responding to learners’ needs, cut across their engagements with learners in the classroom and individually outside the class. Others are specific to either in or out of the classroom. Drawing on learners’ expertise and providing learners with the option of not attending particular classes were strategies used to diminish classroom distress. Being the learner’s advocate speaks specifically to teachers walking with learners through various processes when they (learners) report problems.

Given the range of psychosocial issues they deal with, teachers spoke poignantly about burnout and secondary trauma. This resulted in their disassociating themselves from their work and, often, learners in need. They indicated that there was little support for them, and, indeed, just under half of the teachers interviewed (for whom we had demographic data) had received no training in teaching LO, including the sensitive topics handled in CSE.

The limitations of this study include that not all provinces are represented in the data. Although the ratio of fee-paying and no fee-paying schools sampled in our study reflect the national picture, we were unable to replicate this in terms of rural versus urban schools. This paper reflects the voices of LO teachers and not those of learners or school authorities, who may view the situation differently.

Conclusion

Our findings point, we argue, to the need to recognize LO teachers as sexual, reproductive and mental health frontline workers. They identify, contain, and refer learners who experience trauma (such as rape) or psychosocial problems (such as coerced transactional sex or unplanned pregnancies); they support learners with problems within the school setting; they advocate for learners outside the school system, especially where other systems of social care and justice fail them; and they provide psycho-education. Indeed, some researchers (Weston et al., 2018) have argued that frontline worker status applies to all teachers: “They are there, ‘in loco parentis,’ one-third of the day, two-thirds of the year, charged with the safekeeping and education of our young” (p. 105).

The South African Department of Basic Education (2014) Policy on Screening, Identification, Assessment and Support (SIAS) does, to some extent, recognize the frontline worker role played by LO teachers. According to the policy, LO teachers should form part of the school-based support team that identifies learning and psychosocial difficulties among learners and the appropriate path for intervention. However, research conducted in KwaZulu/Natal (a province of South Africa) indicated that very few teachers reported being trained to use SIAS tools (Bukola et al., 2020). Indeed, appropriate training and support for LO teachers seem sorely lacking, as indicated by just under half of our sample having received no training.

Training for LO teachers should include not only input on the content of what is to be taught but also learner-centered, dialogical pedagogy (see, for example, Jearey-Graham and Macleod, 2017), basic mental health screening skills, deep listening skills, emotional containment and lay counseling skills, and referral skills. Ongoing support and consultation with peers and other mental health professionals will go a long way in preventing the burnout and secondary trauma reported by our participants. A well-being approach to sexuality education necessitates providing teachers tasked with teaching sexuality education in traumatized societies such as South Africa with such ongoing support.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the dataset is stored in password protected files. CSSR staff have ethics approval and consent from the participants to access these data. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Yy5tYWNsZW9kQHJ1LmFjLnph.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Rhodes University Ethics Committee – Human Participants, Rhodes University, South Africa. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

CM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft. UP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding for this project came from the Centre for Sexualities, AIDS and Gender (CSA&G), University of Pretoria. The CSSR’s work is also supported by the South African Research Chairs initiative of the Department of Science and Technology and National Research Foundation of South Africa (grant no. 87582).

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Tshego Bessenaar of IBIS for facilitating data collection in Gauteng. We thank the principals of the schools for granting us permission to conduct the study with their Life Orientation teachers. The following people conducted the interviews: Abenathi Gqomo; Diemo Masuko; Kanyisa Booi; Relebohile Motana. Thank you for your careful interaction with the LO teachers. The data were translated and transcribed by: Amahle Mtsekana; Andiswa Bukula; Bulelani Nonyukela; Donica Walton; Inathi Matini; Khuselwa Tembani; Lithalethu Hashe; Maliviwe Qharhashe; Mihlali Mbunge; Nonkuthalo Tshaka; Qhawekazi Mahlasela; Thab’sile Mgwili; Thasky Fatyi; Tuleka Ngcingane; Zimbini Sikweza; Zoluntu Luntu. Our major thanks go to the LO teachers who engaged with us in an open and in-depth way about the challenges they face and the possibilities and importance of teaching LO and dealing with learners problems positively. We also thank Remmy Shawa and Thandeka Mvuleni for comments on a report on which this paper is based, and the Department of Basic Education and UNESCO Comprehensive Sexualities Education (CSE) Reference Group for inputs on the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^ https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/crime-rate-by-country

2. ^In isiXhosa, the language in which this interview was conducted, no distinction is made linguistically between genders. For ease of reading we use “them/they” as the pronoun here.

References

Adekola, A. P., and Mavhandu-Mudzusi, A. H. (2023). Addressing learner-Centred barriers to sexuality education in rural areas of South Africa: learners’ perspectives on promoting sexual health outcomes. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 20, 1–17. doi: 10.1007/s13178-021-00651-1

Ahmed, N., Flisher, A. J., Mathews, C., Mukoma, W., and Jansen, S. (2009). HIV education in south African schools: the dilemma and conflicts of educators. Scand. J. Public Health 37, 48–54. doi: 10.1177/1403494808097190

Bhana, D. (2016). Childhood sexuality and AIDS education: The price of innocence 1st. New York: Routledge.

Bhana, D., and Anderson, B. (2013). Desire and constraint in the construction of south African teenage women’s sexualities. Sexualities 16, 548–564. doi: 10.1177/1363460713487366

Bhana, D., Crewe, M., and Aggleton, P. (2019). Sex, sexuality and education in South Africa. Sex Educ. 19, 361–370. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2019.1620008

Bukola, G., Bhana, A., and Petersen, I. (2020). Planning for child and adolescent mental health interventions in a rural district of South Africa: a situational analysis. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 32, 45–65. doi: 10.2989/17280583.2020.1765787

Businesstech. (2021). A growing number of schools in South Africa have a real problem – Unpaid fees. Available at: https://businesstech.co.za/news/finance/463926/a-growing-number-of-schools-in-south-africa-have-a-real-problem-unpaid-fees/#:~:text=In

Department of Basic Education (2014). Policy on screening, identification, assessment and support. Pretoria, South Africa: Department of Basic Education.

Fine, M. (1988). Sexuality, schooling, and adolescent females: the missing discourse of desire. Harv. Educ. Rev. 58, 29–54. doi: 10.17763/haer.58.1.u0468k1v2n2n8242

Fine, M., and McClelland, S. I. (2006). Sexuality education and desire: still missing after all these years. Harv. Educ. Rev. 76, 297–338. doi: 10.17763/haer.76.3.w5042g23122n6703

Francis, D. A. (2010). Sexuality education in South Africa: three essential questions. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 30, 314–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2009.12.003

Francis, D. A. (2019). What does the teaching and learning of sexuality education in south African schools reveal about counter-normative sexualities? Sex Educ. 19, 406–421. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2018.1563535

Francis, D. A., and DePalma, R. (2014). Teacher perspectives on abstinence and safe sex education in South Africa. Sex Educ. 14, 81–94. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2013.833091

Francis, D. A., and Depalma, R. (2015). ‘You need to have some guts to teach’: teacher preparation and characteristics for the teaching of sexuality and HIV/AIDS education in south African schools. Sahara J 12, 30–38. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2015.1085892

Francis, D. A., and Reygan, F. (2016). “Let’s see if it won’t go away by itself.” LGBT microaggressions among teachers in South Africa. Educ. Chang. 20, 180–201. doi: 10.17159/1947-9417/2016/1124

Hanass-Hancock, J., Chappell, P., Johns, R., and Nene, S. (2018). Breaking the silence through delivering comprehensive sexuality education to learners with disabilities in South Africa: educators experiences. Sex. Disabil. 36, 105–121. doi: 10.1007/s11195-018-9525-0

Helleve, A., Flisher, A., Onya, H., Mukoma, W., and Klepp, K. I. (2009). South African teachers’ reflections on the impact of culture on their teaching of sexuality and HIV/AIDS. Cult. Health Sex. 11, 189–204. doi: 10.1080/13691050802562613

Helleve, A., Flisher, A. J., Onya, H., Mũkoma, W., and Klepp, K.-I. (2011). Can any teacher teach sexuality and HIV/AIDS? Perspectives of South African life orientation teachers. Sex Educ. 11, 13–26. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2011.538143

Jearey-Graham, N., and Macleod, C. I. (2017). Gender, dialogue and discursive psychology: a pilot sexuality intervention with south African high-school learners. Sex Educ. 17, 555–570. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2017.1320983

Jimmyns, C. A., and Meyer-Weitz, A. (2020). Factors that have an impact on educator pedagogues in teaching sexuality education to secondary school learners in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 17, 364–377. doi: 10.1007/s13178-019-00400-5

Macleod, C. (2009). Danger and disease in sex education: the saturation of “adolescence” with colonialist assumptions. J. Health Manag. 11, 375–389. doi: 10.1177/097206340901100207

Macleod, C., Moodley, D., and Young, L. S. (2015). Sexual socialisation in life orientation manuals versus popular music: Responsibilisation versus pleasure, tension and complexity. Perspect. Educ. 33, 90–107. doi: 10.38140/pie.v33i2.1908

National Department of Health, Statistics South Africa, South African Medical Council, and ICF (2019). South Africa demographic and health survey 2016. Pretoria: National Department of Health.

Ngabaza, S. (2021). Final report on audit of comprehensive sexuality education curriculum at south African higher education institutions.

Ngabaza, S., and Shefer, T. (2019). Sexuality education in south African schools: deconstructing the dominant response to young people’s sexualities in contemporary schooling contexts. Sex Educ. 19, 422–435. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2019.1602033

Ngabaza, S., Shefer, T., and Catriona, I. M. (2016). “Girls need to behave like girls you know”: the complexities of applying a gender justice goal within sexuality education in south African schools. Reprod. Health Matters 24, 71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.rhm.2016.11.007

Pillay, J. (2012). Keystone life orientation (LO) teachers: implications for educational, social, and cultural contexts. South African J. Educ. 32, 167–177. doi: 10.15700/saje.v32n2a497

Potgieter, C., Strebel, A., Shefer, T., and Wagner, C. (2012). Taxi ‘sugar daddies’ and taxi queens: male taxi driver attitudes regarding transactional relationships in the Western cape, South Africa. Sahara J. 9, 192–199. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2012.745286

Riessman, C. K. (2011). “What’s different about narrative inquiry: case, categories and context” in Qualitative research. ed. D. Silverman (London: SAGE), 310–330.

Saville Young, L., Moodley, D., and Macleod, C. I. (2019). Feminine sexual desire and shame in the classroom: an educator’s constructions of and investments in sexuality education. Sex Educ. 19, 486–500. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2018.1511974

Shefer, T., Bhana, D., and Morrell, R. (2013). Teenage pregnancy and parenting at school in contemporary South African contexts: deconstructing school narratives and understanding policy implementation. Perspect. Educ. 31, 1–10. doi: 10.38140/pie.v31i1.1789

Shefer, T., Clowes, L., and Vergnani, T. (2012). Narratives of transactional sex on a university campus. Cult. Health Sex. 14, 435–447. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.664660

Shefer, T., and Macleod, C. (2015). Life orientation sexuality education in South Africa: gendered norms, justice and transformation. Perspect. Educ. 33, 1–10. doi: 10.38140/pie.v33i2.1902

Sibanda-Moyo, N., Khonje, E., and Brobbey, M. K. (2017). Violence against women in South Africa: a country in crisis. Braamfontein, South Africa: Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation.

Smythe, D. (2015). Rape unresolved: Policing sexual offences in South Africa. Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press

Weston, K., Ott, M., and Rodger, S. (2018). “Yet one more expectation for teachers” in Handbook of school-based mental health promotion. eds. A. W. Leschied, D. H. Saklofske, and G. L. Flett (New York: Springer), 105–126.

Wood, L., and Rolleri, L. A. (2014). Sex education sexuality, society and learning designing an effective sexuality education curriculum for schools: lessons gleaned from the south(ern) African literature. Sex Educ. 14, 525–542. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2014.918540

World Bank (2022). Inequality in southern Africa: An assessment of the Southern African customs union. Washington D.C. Available at: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099125303072236903/pdf/P1649270c02a1f06b0a3ae02e57eadd7a82.pdf

Keywords: comprehensive sexuality education, life orientation, South Africa, trauma, gender-based violence

Citation: Macleod CI and du Plessis U (2024) Teaching comprehensive sexuality education in a traumatized society: recognizing teachers as sexual, reproductive, and mental health frontline workers. Front. Educ. 9:1276299. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1276299

Edited by:

Jacqueline Hendriks, Curtin University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Ayobami Precious Adekola, University of South Africa, South AfricaDamien W. Riggs, Flinders University, Australia

Copyright © 2024 Macleod and du Plessis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Catriona Ida Macleod, Yy5tYWNsZW9kQHJ1LmFjLnph

Catriona Ida Macleod

Catriona Ida Macleod Ulandi du Plessis

Ulandi du Plessis