- 1Department of Educational and Social Work, Social Research Methods and Social Work, University of Applied Science Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany

- 2Faculty of Social Work, Theories of Social Work, Catholic University Eichstätt-Ingolstadt, Eichstätt, Germany

Introduction: As a result of the large-scale arrivals of refugees and migrants, Germany is facing the challenge of providing inclusive education pathways not at least for a successful integration into the labor market. In our research project laeneAs (Ländliche Bildugnsumwelten junger Geflüchteter in der beruflichen Ausbildung/The Rural Educational Environments of Young Refugees in Vocational Training), we focus on educational barriers and good practices within the vocational education and training system (VET) for refugees in rural counties. In particular, racism and discrimination are significant barriers to refugee participation in society and education. Our contribution addresses the following research question: How is educational inclusion discussed and defined in and through real-world labs among stakeholders in four rural districts: social workers, educators, policymakers, administration, and young refugees?.

Methods: We initiated real-world labs as a space for collaborative research, reflection, and development to promote inclusive pathways for young refugees in vocational education and training in four research sites. We used futures labs as a method to identify key challenges and develop action plans as an activating method with stakeholders and refugee trainees. Our data consisted of audio recordings of group discussions in the real-world future labs, which were analyzed using deductive content analysis.

Results: The analysis identified the following areas as important barriers to education and for practice transformation: (1) infrastructural and cultural barriers; (2) day-to-day problems in vocational schools and companies (3) restrictive immigration policies and regulations.

Discussion: Educational barriers are imbedded in a contradictory immigration regime with reciprocal effects so that refugee trainees have difficulties in completing their education and further their social inclusion. On the other side of this contradictory immigration regime, social work and social networks provide fundamental support in obtaining a vocational qualification.

1 Introduction

Germany has become the most important destination for refugees in Europe (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2023). The successful inclusion of young refugees into the vocational education system is considered as one important pathway to compensate for discontinuous educational biographies and provide opportunities for successful labor market integration. Studies have also shown legal and institutional frameworks leading to mechanisms of exclusion in the vocational systems in Germany for refugee students especially those with low qualifications and insufficient German language proficiency (Jacob and Solga, 2015; Korntheuer et al., 2018b). According to the numbers of the Central Register of Foreigners, 14.58% (445.765) of more than 3 million refugees living in Germany by the end of 2022 were aged 16–24 and thus potential addressees for vocational training programs (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2023). The numbers of the Central Office for foreigners use a broad definition for the humanitarian population including among others asylum seekers (without a final decision on their claim), Ukrainians, resettled refugees and denied asylum seekers. In our research and hence in this contribution we use refugee trainees/students as an umbrella term, including youth still in the process of an asylum claim, as well as persons entitled to protection and denied asylum seekers.

There has been a significant increase in research on educational participation of refugee children and youth in Germany from 2015 to 2020. Studies have shown that educational responses to refugee children and youth vary widely in the German federal states. Considerable problems in achieving educational equity within the German education systems and within vocational education are apparent (Massumi et al., 2023). Older youth and young adults are especially vulnerable to educational exclusion (Pavia Lareiro, 2019). Reducing educational barriers within the VET system by changing and adapting the institutional framework and local practices can lead to a more inclusive education system. Improving the inclusiveness of VET can create opportunities for the young refugees with no German school degree and only possessing low (formal) qualifications. However, inclusion for refugees and migrants cannot be limited to strategies and measures that reduce deficits in language skills and everyday competences to cope with the challenges of Western society. Rather, administrative regulations and the organization of educational practices need to be adapted and improved to meet the specific needs of migrants and refugees (El-Mafaalani and Massumi, 2019).

Vocational education in Germany is negotiated and, sometimes, critically discussed under the focus of the shortage of skilled workers and training skills. At the same time, labor market regimes have changed—away from mass unemployment toward a shortage of skilled workers (Ehmke and Lindner, 2015). Against this backdrop, migration is increasingly seen as an opportunity, and even a necessity, so that Germany can remain competitive as an industrial and technological economy in the face of demographic change with an aging society and a growing number of pensioners, especially in rural areas (Mehl et al., 2023).

Since 2015, the rural areas have faced new challenges in establishing (social) services to cope with the arrival of refugees and their sustainable social integration (Ohliger et al., 2017). Refugees have increasingly been allocated to the rural districts, which often have to implement refugee and integration policies for the first time (Rösch and Schneider, 2019). In the rural areas, particularly, there is a backlog in opening up the VET system to diverse trainees in redesigning the educational system to adapt to the needs of refugees and in providing VET-related services to improve social inclusion (Kart et al., 2020). Our contribution focuses on educational barriers in the German VET system for refugees and the ways in which concepts of migration affect educational practices in rural areas, where refugees have been largely underrepresented. The findings are based on the transdisciplinary research and development project laeneAs (Ländliche Bildungsumwelten junger Geflüchteter in der beruflichen Ausbildung/The Rural Educational Environments of Young Refugees in Vocational Training) (Korntheuer and Thomas, 2022). LaeneAs aims both to identify educational barriers that prevent equal participation and to develop sustainable and innovative solutions to support migrants and refugees in VET. To achieve this, real-world labs have been organized to discuss barriers in VET with refugee trainees and stakeholders from the field and to develop innovative educational practices.

In our contribution we ask how educational inclusion is defined and educational practices are negotiated within institutions and among individuals on a local level. We inquire how educational barriers are discussed and prioritized and what kind of practice transformation is envisioned by the participants in the real-world labs. Instead of urban contexts, we focus on the educational inclusion of young refugees in four rural counties in southern and eastern Germany. As an empirical framework, we adopt an applied science approach that places the local knowledge of the research participants at the center of theory building. “The inclusion of a multitude of perspectives by strengthening the discourse between (civil) society and science leads not only to an increase in knowledge production but also to a different type of knowledge that can contribute to finding more sustainable solutions for practical societal challenges and problems” (Thomas et al., 2021). The focus on sustainability of problem-definitions and useful solutions prioritizes the relevance structures of participants from social practice over a social science theory.

Our article is structured in five sections: After the introduction, we draw on current research to highlight the context of integration in German rural areas, describe main structures of the German VET system, and review the state of research on educational barriers for refugee trainees (Section 2). We then state our research questions and explain real-world labs as our methodology for co-constructive knowledge creation and practice transformation in laeneAs (Section 3). In our result and discussion section (Section 4), we discuss important barriers to education and practice transformation: infrastructural and cultural barriers, day-to-day problems in vocational schools and companies and restrictive immigration policies and regulations. Our conclusion (Section 5) points at educational barriers interacting in the context of a contradictory immigration regime as exclusionary conditions on a structural level while buffering effects of social work and social networks of the local community of practice. We conclude by referring to the limitations of our study and proposing directions for future research and practice.

2 State of research on educational barriers and educational practices for refugee youth in VET

2.1 Integration pathways in the rural areas

Scientific interest in the integration pathways of refugees in the rural areas in Germany increased after the large-scale arrival of refugee population in 2015/2016. Nevertheless, research knowledge on specific challenges and resources in rural areas is still scarce. In Germany, integration research often views integration as the adaptation of migrants to existing societal systems. Take, for instance, the use of labor market participation rates among individuals with refugee experience as a key metric for integration success. However, many current models lack a holistic approach, failing to consider the reciprocal roles of the receiving society and the important influence of local conditions upon arrival (Glorius et al., 2021; Korntheuer et al., 2021).

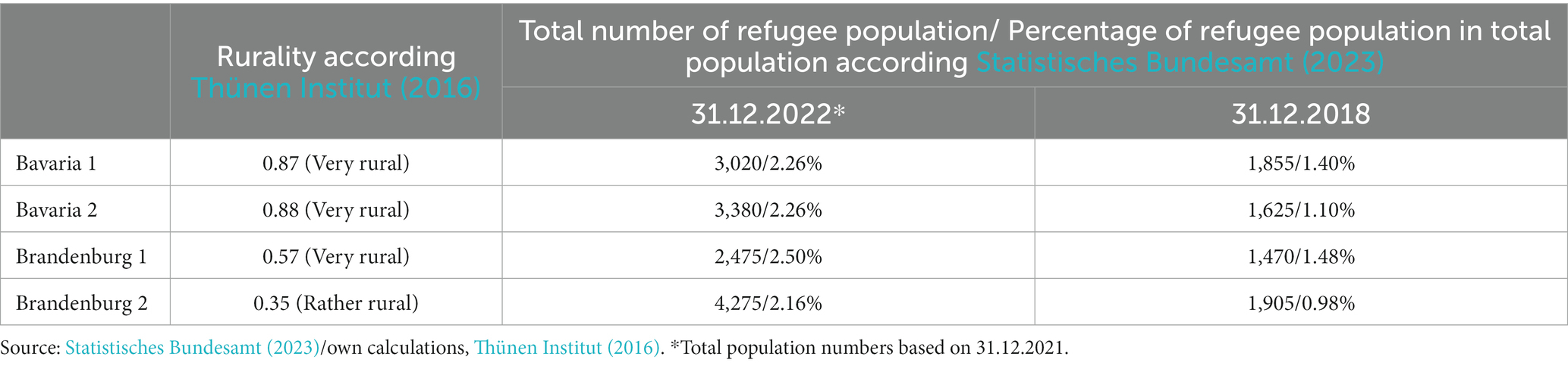

With a focus on concrete counties in rural areas, laeneAs aims to bridge these gaps by framing educational integration as a dynamic two-way process (Berry, 2008). In this approach, various stakeholders from the receiving society interact with young refugee trainees to negotiate, define, and implement educational practices tailored to specific rural contexts. Our research unfolds in three “very rural districts” and one classified as “rather rural,” as per the Thünen institute’s typology (see Table 1).

According to that typology, rural districts are characterized by indicators of low settlement density, a high proportion of agricultural and forestry land, a low population potential, high-share of single- and two-family houses in all residential buildings, and poor accessibility to large centers (Küpper, 2016). With two counties in Brandenburg as an eastern German state and two counties in Bavaria as a southern German state, very different historically evolved, social, and educational policy frameworks are included (Korntheuer and Thomas, 2022). Furthermore, the two counties in Brandenburg are defined as providing less favorable socio-economic living conditions in terms of income, employment, health, education, housing, and public services than the Bavarian counties (Küpper, 2016; Rösch and Schneider, 2019). Like other eastern German states, Brandenburg has a much smaller economy and is characterized by emigration and an aging population. However, it is not only the (elderly) care professions that are suffering from a shortage of skilled workers, but also the craft trades. In Bavaria, there is a very high demand for trainees due to the continuing positive economic situation with low unemployment rates (Seeber et al., 2019).

2.1.1 Number of refugees and asylum seeker in rural areas in Germany

National dispersal and distribution policies for asylum seekers and accepted refugees in Germany increased the role of rural areas since 2015. Once individuals arrive in Germany and go through initial reception facilities, they transition to more permanent accommodation in different federal states using a fixed quota system called the “Königstein key” (Korntheuer, 2017). Asylum seekers, whether accepted or denied, must live in the assigned shelter. The Integration Law of 2016 introduced new rules, also obliging accepted refugees to stay in the federal state where their asylum process occurred for 3 years, leading to a notable increase in the number of refugees in rural areas (Weber, 2023). According to a study by the Ministry of Migration (BAMF) using 2018 data, 52% of asylum seekers in Germany reside in rural areas (Rösch and Schneider, 2019). With the recent arrival of over a million people fleeing the conflict in Ukraine (Brücker et al., 2022), it is reasonable to assume that rural areas have accommodated a significant portion of these newcomers. Increasing numbers of refugee population in the four rural counties in laeneAs between end of 2018 and 2022 support this assumption (see Table 1).

Because of demographic development and lack of qualified labor force, most rural areas have strategic interests that refugee population remain in the area once they are legally accepted. However, Weber (2023) finds population loss through mobility toward urban areas in eastern Germany, but only marginal migration losses were observed in the urban districts. These results raise questions with regard to how integration conditions result in different resources and challenges for refugee population in rural and urban areas.

2.1.2 Specific context factors on integration in rural areas

Knowledge on integration trajectories in rural areas is very scarce so far. The recent mixed-method research project “Future for refugees in rural regions of Germany” is among the few exceptions in this regard. It provides rich knowledge and new insights on the specific context factors for the integration of refugee population in rural areas. Based on a citizen survey of 908 residents and 139 qualitative interviews with refugee residents and experts in eight districts and 32 municipalities the role of the receiving society, local integration politics, and the perspective of the newcomers were analyzed (Glorius et al., 2020, 2021; Mehl et al., 2023). Five central conditions for the integration of refugees in rural areas are specified (Mehl et al., 2023, 10ff.):

• Settlement structure of rural areas poses challenges to everyday mobility: There is limited accessibility of training places, schools, and support services.

• The rural housing market is partly more accessible, but it is generally geared to owning and not renting.

• Lower numbers of migrants in the population result in less possibilities for contact within their own national, ethnic, or linguistic community, which can make arrival more difficult because of the lack of bonding relationships.

• Municipalities have fewer administrative resources, and some of the responsibilities might be located within the administrative governance of the district level and not of the municipality, limiting local decision-making competencies.

• Through social nearness in rural areas, access to administration and decision-makers is associated with low hurdles, and a high level of civic engagement exists.

The role of the residents’ attitudes is stressed by further studies. Schmidt et al. (2020) show that rural population has more skeptical attitudes toward refugees and see less opportunities and chances for their region because of their settlement. Furthermore, refugee population reported more experiences of discrimination in rural areas, although differences were not statistically significant compared to urban areas. More than half of the refugee population in the rural areas reported some experiences of discrimination, but only 10% frequent experiences (Schmidt et al., 2020). On the other hand, more contacts to members of the receiving society than in urban areas were recorded. Glorius et al. (2020) find that long-term residents report only scarce social contacts with migrants. Following the contact hypothesis, they propose a focus of government intervention to reduce concerns about immigration and xenophobia through the strengthening of inter-ethnic social networks in order to create positive narratives between newcomers and residents and reduce abstract worries on both sides.

2.2 The vocational education and training system in Germany

Vocational education and training (VET) is situated between the school system and the labor market and interacts with a wide range of economic and governmental actors and institutions (Euler and Wieland, 2015). Dual vocational training is a form of education that combines on-the-job training in a company with vocational school education, leading to a recognized qualification that serves as an entry point into the labor market. The legal foundation for VET dates to the Vocational Training Act of 1969, which establishes standardized regulations nationwide for company-based training and the recognition of vocational occupations by the state. This legislation outlines requirements for training companies and the overall structure of the training process.

Several potentials are attributed to the VET system, which has a good reputation in the international context [Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF), 2021], such as low youth unemployment (Euler and Wieland, 2015), low entry requirements, successful labor market integration of refugees, financial independence through training allowances, high-quality standards, and diverse occupational profiles. The current success of Germany’s economy is linked to the VET system with low unemployment, especially because of a well-educated workforce (Ebner, 2015). The increasingly complex requirements of a modern work environment necessitate not only the training of practical skills but also the provision of theoretical knowledge through schooling. Dual vocational training combines these two areas of knowledge in the learning environments of the company and the vocational school: The practical part of the training takes place in the company while the vocational school imparts theoretical knowledge. In total, there were 324 vocational occupations registered in Germany in 2022 [Bundesinstitut für Berufliche Bildung (BIBB), 2022]. The vocational occupations are organized in chambers: The chambers represent the interests of the regional economy and offers occupations in areas such as construction, woodwork, metal/electrical, clothing, food, and health.

In Germany, there are three types of secondary school leaving certificates: Hauptschulabschluss (after 9 years), Realschulabschluss (after 10 years), and Abitur (after 12 or 13 years) for university entrance. The dual system is open to all school graduates while many school-based training programs require at least the certificate of the intermediate level (Baethge, 2008; Jacob and Solga, 2015). Challenges in the VET system includes, low remuneration, limited transition to higher education, and segregation of migrant and refugee trainees into less attractive occupations with lower earning potential, like the food industry, gastronomy, and construction (Korntheuer et al., 2018b; Crul et al., 2019). A continuous increase in the rate of university admission compared to a decline in trainees entering VET has been observed since the year 2000. This is interpreted as a devaluation of vocational education (Baethge and Wolter, 2015). The limited permeability of the VET system to higher education is also criticized in terms of educational justice in Germany. Nevertheless, it can be stated that VET in Germany leads to recognized vocational qualifications and offers numerous opportunities for the long-term labor market integration. Initiating training can also provide opportunities to secure residence status for refugees (Schreyer et al., 2015). Various programs and projects aim to promote the uptake of VET by refugees, chambers for example introduced “VET navigators” to support the transition into training places through a counseling service (Rietig, 2016).

2.3 Educational barriers in the German VET system for refugee trainees

The number of unfilled training places has increased over the past decade [Bundesinstitut für Berufliche Bildung (BIBB), 2020, 14]. Due to a shortage of skilled workers, companies are increasingly willing to train and hire young refugees (Vogel and Scheiermann, 2019). Nevertheless, access to in-company training is fundamentally more difficult and takes longer for refugee youth compared to their peers, and more time is needed for a successful transition (Beicht and Walden, 2018). In addition to an insufficient number of applicants, companies cite a lack of German language skills and inadequate professional expertise, a lack of transparency of foreign qualifications, high administrative and support costs, and insecurity regarding residency laws. A lack of experience and uncertainty regarding the support of refugees and a lack of public support services or inadequate services are other important barriers from the perspective of the companies. Furthermore, they are aware of possible reservations on the part of customers and possible critical attitudes on the part of their own staff toward hiring refugees (Kart et al., 2020; Pierenkemper and Heuer, 2020).

From the perspective and experience of refugee trainees, language can also present a barrier, especially with regard to job-related technical jargon. Additional tutoring and support services for trainees can generally be regarded as positive, but at the same time, they represent an additional learning challenge “for the already heavily burdened trainees” (Kart et al., 2020). Moreover, high dropout rates indicate that the monolingual-oriented VET system does not adequately meet the needs of second-language learners (Rietig, 2016).

At the end of 2018, 34% of refugee youth aged between 15 and 25 registered with the Federal Employment Agency were in dual vocational training. In the year 2018, 23.7% of all training contracts of trainees with a foreign passport were terminated within the probation period [Bundesinstitut für Berufliche Bildung (BIBB), 2020]. In addition to legal status, language skills, individual learning requirements, and personal situations of the heterogeneous group of trainees, to which the establishment of diverse (but sometimes confusing) support measures has responded, obstructive framework conditions, structural exclusion mechanisms, and disadvantages also play a role (Ohliger et al., 2017; Matthes et al., 2018; Vogel and Scheiermann, 2019). As highlighted by the literature [Bundesinstitut für Berufliche Bildung (BIBB), 2020], there emerges a pressing call for heightened awareness of diversity within vocational education schools and companies. This acknowledgement becomes pivotal in not only navigating the confusing landscape of support measures but also in fostering a more inclusive and equitable learning environment for all trainees.

In addition, racism and discrimination are significant barriers to the participation of refugees in society (Bucher et al., 2024). In this context, residence status, in particular, plays a significant role in creating inequalities and hierarchies through its pre-structuring influence on participation in the receiving society (Hormel, 2010).

Moreover, discrimination and racism impede labor market integration (Huke, 2020) also in the context of dual vocational education (Chadderton and Edmonds, 2015). Imdorf (2017) illustrates disadvantages affecting the allocation of training places. For instance, a headscarf can affect exclusion according to a qualitative study with refugee women (Koopmann, 2022). Furthermore, conflicts and experiences of discrimination in institutions of (vocational) education can lead to dropouts (Ahmadzadeh et al., 2014; Korntheuer et al., 2018a). Although migration-related heterogeneity is seen as common in companies, refugees are still confronted with racism, discrimination (Huke, 2020). It is stressful and problematic when racism is acted out by superiors and teachers, especially if this behavior is not sanctioned, played down, or even deliberately tolerated. This is even more relevant if the residency permit is linked to the vocational training position (Huke, 2020).

In the process of choosing a vocational occupation, the refugees themselves often set their own interests aside, as they often pressured regarding their residence status and with expectations for them to integrate (Bucher et al., 2024). The career choice process is thus linked to “career pragmatism as an adaptation strategy” (Wehking, 2020, 385). The possibilities for refugees to freely shape their own educational biography are limited (Schlachzig, 2022).

Certified competences and qualifications can often not be provided; and some job profiles are hardly comparable to those in the country of arrival, which, in combination with formally restrictive recognition practices of foreign credentials, results in a considerable devaluation of degrees and informally acquired competences (Chadderton and Edmonds, 2015). In the context of forced migration, it is also a point of criticism that the apprenticeship remuneration is insufficient for livelihood and does not support, for example, family assistance or the repayment of debts incurred during the journey. Therefore, the argument for financial incentives in the context of forced migration is not valid (Rietig, 2016).

Generally, there is paucity on the research on vocational training in rural areas. Limited mobility is one central barrier for trainees in rural areas. A driver’s license, for instance, is often a recruitment requirement for trainees in companies, especially because of the lack of public transportation (Kart et al., 2020). On the other hand, positive factors in rural areas are diverse informal structures that facilitate social participation (Ohliger et al., 2017; Schiff and Clavé-Mercier, 2019). Civic society such as volunteerism, civil initiatives, or neighborhood assistance can support social participation and facilitate the access to the local labor market (Kordel, 2016; Schäfer, 2019; Wagner, 2019). Programs can support the local integration of refugees into the labor market: company networks, the commitment of welfare associations and volunteers also for digital services (Rösch et al., 2020).

3 Research design and methods

3.1 Research question

In our paper, we address educational barriers and pathways of changing practices by asking the following research question: How is educational inclusion discussed and defined in and through real-world labs among social workers, educators, policymakers, and young refugees? To narrow down the scope of our analysis, we will present data on the following aspects: How are educational barriers defined and prioritized in the established practices of the rural VET system by administrators, practitioners, and refugees? What kind of changes and improvements are envisioned in the real-world labs toward new educational policies and practices at the micro level? What challenges and obstacles are discussed by the participants? How are the educational practices perpetuated and challenged by the different stakeholders in the field with a focus on institutional and everyday racism?

3.2 Real-world laboratories

LaeneAs aims at transdisciplinary research on educational barriers and collaborative development of educational practices. To achieve this, we initiated real-world labs as a space for collaborative research, reflection, and development (Defila and Di Giulio, 2018, p. 13; Engels and Walz, 2018) to promote inclusive pathways for young refugees in VET (Korntheuer and Thomas, 2022). Scheller et al. (2020, 52) note: “Real-world Laboratories (RwLs) have become a popular social experimentation approach at the intersection between science and society, especially in the field of sustainability and transformative studies.” Controlled experiments are conducted in real-world contexts rather than in scientific laboratories (Schäpke et al., 2018). In the social sciences in particular, real-world labs are often initiated in accordance with the principles of participatory research methods as a co-constructive way of including the lifeworld views and expertise of citizens and stakeholders in social fields in the research process (Bergold and Thomas, 2012) with the aim of (1) collecting data to answer scientific questions about educational barriers; (2) developing best practice models; and (3) ensuring sustainability by including the expertise, experiences, and perspectives of key stakeholders and refugee trainees.

Real-world labs offer a transdisciplinary and transformative approach that combines research and practice development (Singer-Brodowski et al., 2018). Applying this transformative approach, we initiated research that aims at generating socially robust knowledge about real-world phenomena and new solutions to social and educational problems. Transformative science “goes beyond observing and analyzing societal transformations, but rather takes an active role in initiating and catalyzing change processes” (Schneidewind et al., 2016, 2). We did not create research spaces as artificial settings but situated them in already established social fields in four rural counties as a re-contextualization of science to meet “grand challenges” of society (Rip, 2018, 35). They can be characterized as a variant of action research, which was introduced by Kurt Lewin in the 1940s. The research cycle is ideally constructed in “a spiral of steps, each of which is composed of a circle of planning, action, and fact-finding about the result of the action” (Lewin, 1946, 38). Transdisciplinarity includes not only perspectives from different academic fields, but also from practitioners and people with lived experience (of, for example, forced migration). Citizens’ perspectives, their social concerns, and social innovations from the field are taken seriously into account in a joint research process (Scheller et al., 2020). Thomas et al. (2021) conceptualize the “research forum,” according to Kemmis and McTaggart (2005), as a communicative space. Representations, meanings, and practices of people from the social field under study do not primarily fulfill the function of mere data. Rather, a research forum is initiated as a framework for deliberative discussion to achieve a higher level of social self-understanding among the participants of the research group. By inviting the stakeholders and institutions involved in the organization of VET, we provide a forum where taken-for-granted knowledge and already established routines can be discussed and deliberated on. The scientific method supports the “decentration” by stepping back from and taking a “second look” at the implicit and tacit knowledge already socially constructed in the field. Alongside the real-world labs, we set up a participatory peer research group for each research site (Thomas, 2021a,b).

We invited young trainees who came to Germany as refugees to identify educational barriers and to envision good practices as improvements of the existing VET system. The guiding idea is that through peer research, refugees become empowered to develop and articulate their own voice in order to engage with the professionals in the real-world labs (Sauer et al., 2019). This empowerment should encourage the refugees to take the position of active spokespersons to counterbalance the position of the professionals as experts in their fields of education. To redress this power imbalance, the refugees in the peer projects learn to research their own situation, to reflect on their experiences, and to articulate their perspectives not only as personal narratives but also in a conceptual way by generalizing their subjective stance toward a more structural analysis of their situation. Although the peer research is important for the research process, in this paper, we focus on data from the joint workshops in the real-world labs.

3.3 Future labs

Real-world labs provide the methodological framework of laeneAs for combining research and development as a transdisciplinary space. We used future labs to concretize this methodology into practical steps to guide discussions among participants in the real-world labs for developing action plans for innovative solutions. Future labs were used as the guiding method for the first three out of the six real-world lab workshops that we planned for laeneAs at each research site. The first three workshops were held at intervals of one to 2 months over a period of about 6 months at each of our four research sites. Our data comprises three workshops at each of our four research sites, making a total of 12 workshops. The second series of three hands-on workshops at each research site is yet to come and will focus on project development to implement the action plans and on project evaluation. The workshops at all four research sites lasted an average of 4–6 h.

Future workshops (Zukunftswerkstätten) consist of three steps (Jungk and Müllert, 1987; Alminde and Warming, 2020): (1) a critique phase, (2) a fantasy phase, and (3) an implementation phase. The flow of the workshops is generally characterized by a continuous alternation between:

• Discussions in the forum as an assembly of all participants to define common objectives and results.

• Creaking up into small working groups to discuss topics in more detail, and finally.

• Coming back together in the forum to share insights and to synthesize common findings that guide the work progress of the whole group.

Our workshops started with the critique phase (1) with the aim of exploring the current state of VET for refugee trainees in the rural areas. Educational barriers were identified through group discussions focusing on the “strengths and challenges.” In small groups, a brainstorming exercise was used to identify the strengths and challenges that, according to the stakeholders, are relevant in the district. Strengths were recorded on green cards, challenges on red cards and neutral aspects on yellow cards. The topic on the cards were then presented, pinned, and discussed in the large group of the forum. The identified topics were finally ranked by the participants according to their relevance (Figure 1).

(2) In the “fantasy phase,” utopian thinking of a different future was initiated, according to the general brainstorming rules that no censorship is allowed and no contributions are excluded for reasons of realism and pragmatism. Utopian thinking should go beyond the horizon of established practices and conventional thoughts. Following the topics identified by the stakeholders as the most relevant to rural areas—such as mobility, companies, language, etc.—the practical challenges were further specified in working groups (a) by identifying objectives, (b) strategies, and (c) obstacles and barriers to implementation. In the fantasy phase, a mural was created together, and the participants discussed their drawings with each other. The challenges and goals mentioned were then translated into positive formulations. Ideas for solutions, actions and obstacles were brainstormed and drawn on a worksheet. (3) In the implementation phase, the participants finally selected one to two goals to develop implementable “action plans.” To guide the process, we developed a working sheet (see Figure 2) that aimed to define feasible steps with a timetable over a six-month period, with clear responsibilities for each person in implementing the different aspects of the action plan.

The advantage of using the method of future labs is that the transformative and transdisciplinary development of action plans is directly linked to the definitions of problems and barriers provided by the stakeholders. The fantasy phase enabled them to think beyond the pragmatic approaches already applied in their social practices and to develop strategies linked to their competencies and resources.

3.4 Sampling

LaeneAs conducts the real-world labs in the German states of Brandenburg and Bavaria in two rural counties each. Relevant stakeholders were invited to the workshops using snowball sampling (Browne, 2005). In addition, the stakeholders in the rural counties know each other, if not personally, then at least who represents the different institutions involved in the VET system. Without aiming for representativeness, we contacted the identified stakeholders in the counties (vocational schools, educational projects, administration, companies, chambers, social work). We also invited trainees, through training schools and social (migration) work, to for the real-world labs and peer research. In the 12 workshops that we held so far, the number of participants for each workshop consisted of 8–15 participants in Bavaria (on average, 11 professionals and 2 peer researchers) and 8–20 participants in Brandenburg (on average, 14 professionals and 1 peer researcher).

There is a variety of interest and participation of the stakeholders in the real-world labs. Representatives from social work and vocational schools participate in the workshops more regularly, while training companies show less interest or ambition. Two of the participating training companies are larger companies in the region, which can be interpreted as an indication that smaller companies may not be able to achieve regular participation. Attending the workshops is also a challenge for the refugees, as they must take time off from their training companies or have long travel distances. As a result, the composition of participants in the workshops is heterogeneous not only from site to site but also from workshop to workshop, with a fixed group of committed participants who ensure the continuity of the teams.

3.5 Data collection and analysis

Our data consists of audio recordings of the discussions in the future labs as our methodic realization of the first three real-world lab sessions (Berg and Lune, 2017, 144; Thomas et al., 2021). After transcription, we analyzed the data by using the qualitative data analysis application “Atlas.ti” and applied a deductive content analysis (Schreier, 2012; Kuckartz, 2014). The first step of our data analysis was, that we defined our central categories that we applied for an in-depth analysis. The categories were based on the list of overarching topics defined in the critique phase as they were raised and ranked by the workshop participants (see above). Secondly, we used this list of categories to read carefully all transcripts of the discussion in the workshops. Relevant data segments/quotes were coded according to the list of categories. We identified for all categories 1,102 quotes. Finally, we carried out for every category, e.g., housing, gender, racism a comparative thematic analysis (Charmaz, 2006) by examining the content of all the quotations. Sub-codes were developed inductively by cluster quotes that are thematic related to each other to describe in detail the structure and dynamics of the educational barriers identified in relation to good practice (Figure 3). We quote the citations in the following by using the quotation number given by Atlas.ti (e.g., 12:08 means document 12 and quotation 8).

4 Results and discussion: social representations of educational barriers and ideas for transformative practices

The main findings of the study can be summarized as follows: The educational landscape in the German counties is characterized by the contradiction of exclusionary conditions at the institutional and cultural level, while at the level of local practice, there is a strong commitment to creating inclusive educational pathways. To highlight the factors that perpetuate and challenge educational practices, we present the results from both perspectives below: The first dimension focuses on the social representations that determine the definitions of educational barriers of the different stakeholders. The second dimension is concerned with the ideas for institutional and cultural changes in social practices developed in the workshops to improve the inclusion of refugees and migrants in the German VET systems. The categorizations developed in the workshops may not adequately capture all the details of the discussions, and the rankings are not directly comparable between the different research sites. However, we used the key topics as central codes to identify segments of data that related to educational barriers or good practice. Stakeholders and refugees identified the following areas as important educational barriers and areas of good practice: (1) immigration policy practice, (2) racism and discrimination, (3) language, (4) mobility, (5) housing, (6) training companies and schools, (7) networks. We added as a main code for further analysis the category “gender,” which was not added by the workshop participants to the list of main challenge, but which we considered relevant after reviewing the data.

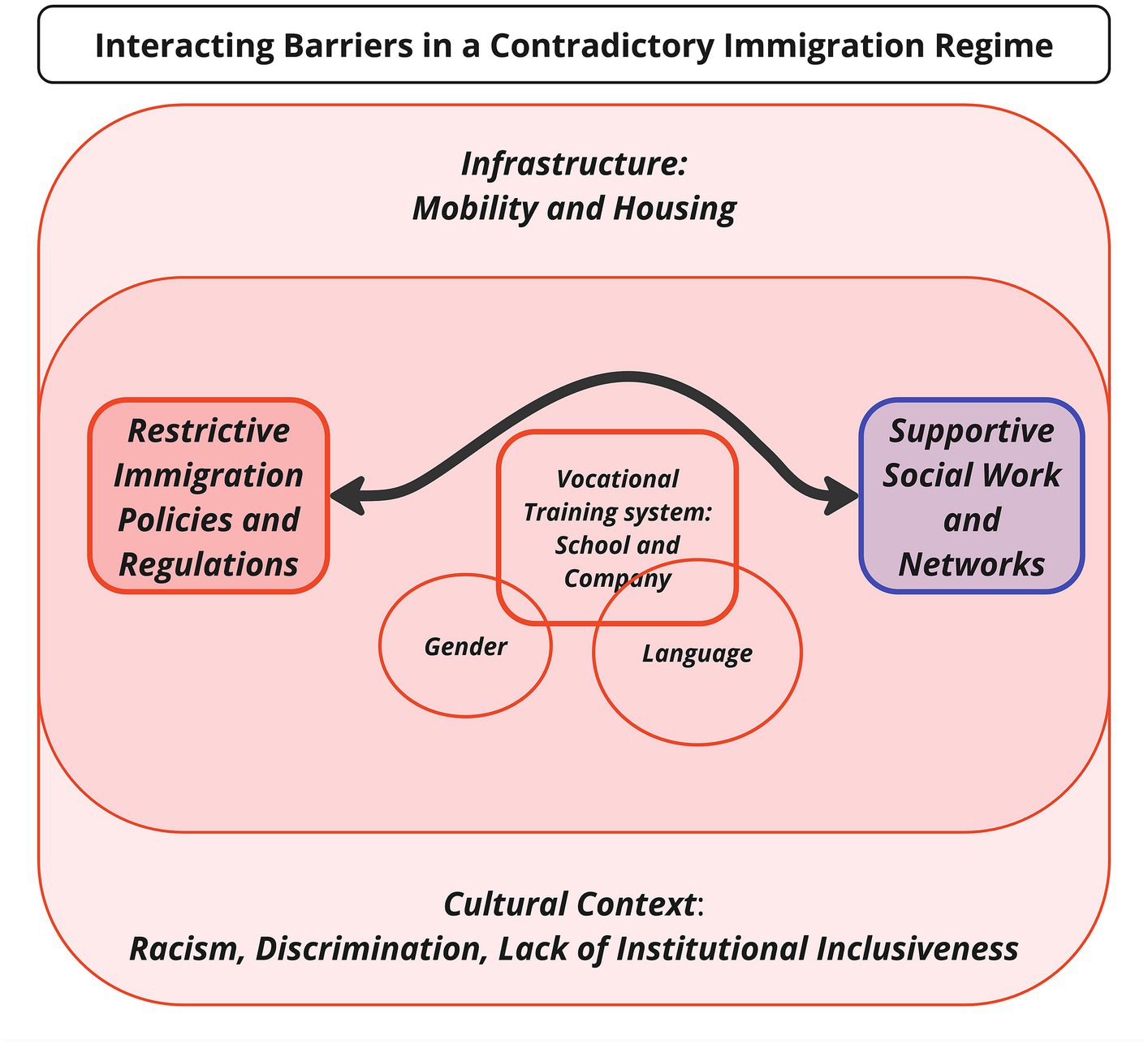

The main finding of the study is the dynamic of “interacting barriers in a contradictory immigration regime.” The main obstacles are not just individual barriers to successful completion of education and long-term access to social institutions and spheres of life in Germany. The data analysis revealed three main areas that stand in the way of successful educational processes. The successful integration of refugees into the labor market is hampered by:

1. Infrastructural and cultural barriers due to inadequate and restricted access to housing and mobility on the one hand, and exclusion due to racism, discrimination, and a lack of institutional inclusiveness on the other.

2. Day-to-day problems that are virulent in vocational schools and companies, occur due to inadequate language skills, and caused by gender-specific challenges and exclusion.

3. Restrictive immigration policies and regulations.

In the following, we would like to take a closer look at these three levels of exclusionary educational barriers in relation to possible solutions, as they were discursively represented by educational actors and refugees in the real-world lab workshops.

4.1 Bus schedules and stereotypes – infrastructural and cultural barriers

On the level of infrastructural and cultural barriers, inadequate housing, mobility, racism, and discrimination becomes apparent as main barriers for successful participation in the VET system as discussed by refugee trainees and practitioners.

Living and learning are substantially shaped by the conditions in mass shelters if trainees are not allowed or unable to move out of the asylum accommodation. Peer researchers point out how living with up to five people, who, in most cases, are strangers in a room of 12 sqm with shared kitchen and bathrooms facilities, results in psychological burdens, lack of space for learning as well as troubles of getting sleep in a noisy and sometimes violent environment. Trainees discuss high density of social and emotional problems, such as sharing a room with people under psychological distress and with mental health conditions and being object to frequent visits from police as well as feeling unsafe and discriminated in these surroundings.

Furthermore, shelters are generally socially isolated and sometimes placed in remote areas, leading to mobility issues and lack of contact with German native speakers. Direct consequences for the participation in VET are lack of language practice and limited capacity and space for acquisition and practice of the learning content of the vocational training. Insufficient internet connection in the shelter is mentioned as a relevant obstacle for online-based learning. If the young people stay in the mass shelter and already earn an apprenticeship salary, they are obliged to pay for their accommodation. Some trainees in the Bavarian counties share their perspective on this unfair situation. They have accumulated debts for inadequate housing and continue to be financially and psychologically burdened after moving out.

The often long duration of accommodation in the shelter system is caused by restrictive residency policies and limited accessibility of the private housing market for the trainees. Residence obligations during the asylum process and the new residency requirements (Weber, 2023) for recognized refugees hinder an improvement of the housing and living conditions. Even if trainees are allowed to move out from the shelter, access to their own apartment or shared apartments is limited due to the lack of housing in the Bavarian counties and due to discriminatory selection of tenants in all our four sites. Moreover, the arrival of refugees from Ukraine adds to already difficult situations and is perceived as discrimination against refugees from other contexts: “Ukrainian come and get immediately an apartment and with you it took 3 years” (45:19). In Brandenburg, however, housing is generally not scarce but still needs to be made accessible to refugees.

But even if private housing is found, trainees report that search for accommodation takes time and remains dissatisfying: a “very, very long way and then we got a very bad apartment” (35:12). Fraudulent and abusive renting terms by landlords are mentioned as well. Generally, the housing in rural areas comes with a limited access to mobility and a lifestyle that is less attractive for some of the trainees, such as less diverse possibilities for social contacts, leisure activities, and workplace opportunities. On the other hand, being not distracted by the diverse opportunities of city life allows to focus on the vocational training mentioned as a positive factor by the peer researchers.

Educational practice in the context of forced migration needs a holistic perspective on the life and learning situation of young trainees and cannot be limited to formal education structures, as is becoming apparent through the negotiations in the research forum. As one workshop discussion pointed out, envisioning change is limited to the lack of social housing, which is seen as an unchangeable fact. Other stakeholders demand the promotion of social housing and the cooperation with housing companies.

Most of the practice ideas developed involve action at an intermediate level of social change: building institutional structures such as flat-shares or trainee dormitories in areas with good infrastructure. Such solutions could be provided by mayors, pastors, community institutions or NGOs already working in the field. In addition, companies can also be part of the solution by helping their employees to find suitable housing and by assisting them with the bureaucratic steps involved. One specific idea, building on an existing program, is to organize a buddy system targeting elderly people living alone in large flats or detached houses, combining housing and mutual support for refugee trainees and elderly people. One research site discussed how an advocacy group of young trainees could be initiated to raise awareness and work on concrete solutions, such as advocating for a ‘quiet room’ in the collective accommodation for undisturbed study. As a solution at the individual level, it is discussed how young refugees can be made fit for the housing market and how deficits in housing competences can be compensated.

Closely related to the rural housing and accommodation facilities, poor accessibility of educational institutions and support services is another challenge (Fick et al., 2023). In all research locations, limited mobility due to poor infrastructure and lack of public transportation is identified as a main barrier, according to the participants. Lack of mobility is one reason why VET is not taken up or is discontinued, as reported: “There are training places, apprenticeships, but what is difficult, as I said, is always this distance in the first place, to actually get there” (16:11). According to reports from some practitioners, it is difficult for trainees, most of whom are already under a lot of strain, to take up offers of tutoring or language support due to mobility problems and the high time commitment involved.

Refugee trainees who might not be able to afford a driver’s license or are minors anyway are particularly dependent on public transport. Therefore, it is especially important for stakeholders involved in vocational orientation to pay more attention to the young person’s circumstances and realistic training options. The generally high cost of public transportation is also a problem in everyday life. A lack of flexibility regarding scheduled working hours also makes vocational training harder to organize under the circumstances of reduced mobility in rural areas. The topic of mobility is closely connected to housing, as shown in the workshops (see section 4.6).

Participants point out that applications for reallocation are either rejected by the authorities or take so long to be processed that employment is terminated. According to one official, the residence requirement for refugees can only be lifted after the six-month probation period. The main problem is not the lack of mobility, but the legal and political framework that must be considered. The inability to change residence flexibly is a clear barrier, but the loss of existing support networks is also mentioned:

They are partly integrated where they live, know the people, the structures and so on, then they find a training position here. So, I think it’s a shame that you have to change your place of residence just because the buses do not run (16:17).

On the other hand, it becomes clear that a highly pronounced social isolation in rural areas often leads to frustration due to the lack of opportunities to meet people and make friends. This confirms the ambivalence regarding social contacts and relationships in rural space (Glorius et al., 2020; Schmidt et al., 2020).

As described above, lack of mobility emerges as a major structural barrier to the realization of vocational training. It also has a general impact on social participation. In developing solutions to this problem, participants in the workshop discussions often express the feeling of being quite limited. Ideas are strongly linked to alternative means of transport to public transport, whose structural development is considered necessary but not realistic: “Expansion of local public transport has always been a political issue, but so far nothing happened” (46:54). For example, there are frequent calls for transportation subsidies and funding of driving licenses for trainees in rural areas. In addition, participants focus on the development of alternative local infrastructure, for example through the possible use of e-scooters and e-bikes, the establishment of local shuttle services for trainees, and car-sharing options or concepts for organizing car-pooling. As empirical research shows, the level of civic engagement in rural spaces is quite high (Fick et al., 2023) that could be utilized: “Because we have poor public-transport infrastructure. Perhaps a circle of supporters is a very important point” (47:94). On an individual level, smaller projects such as cycling courses for women combined with the free distribution of bicycles are also cited as successful practical examples.

As a central cultural barrier, racism and discrimination is identified as a main barrier not only to vocational training but also in different contexts (Bucher et al., 2024): “and this latent racism, the main racism, that people are exposed to on a daily basis, whether it’s at the immigration office, at Lidl [supermarket], or anywhere else” (37:7). Combined with a lack of inclusive opening processes and diversity-sensitive competencies, it has to be seen as a cross-sectional topic. Participants identify structural, institutional, and everyday racism in society, public authorities, companies, and schools as a problem. Discrimination is also experienced in the housing market. There are many reports of different kinds of constant racist experiences in the everyday lives of the trainees:

“Looks, exactly. Looks, […] you are looked at. […] A grandmother from across the street came out and looked at me the whole time. And me, I was like, ‘Why is she looking at me so strangely, so that I’m noticing it?’ And I’m like, ‘I was looking back at her, sure, but why do not you keep your eyes off me?’ That really made me—I thought about it on the subway until I got home. And that day, I cried” (44:32).

In addition, the lack of personal contact between long-term residents and refugee newcomers in rural areas fosters rejection (Glorius et al., 2020). The same goes for the lack of willingness to change on the part of society with one-sided expectations of adaptation by refugees. The absence of self-representation is particularly evident in rural areas:

“On a more structural level, another challenge here in the county is that there is no migrant self-organization where the target group can represent itself, can be represented politically. And where problems can also be named. Perhaps not only from a white perspective, as it is the case here right now” (14:62).

Unequal and disrespectful treatment, racist and dismissive behavior, and comments in the workplace can come from superiors, colleagues, and customers; as a study by Huke (2020) and our participants state, “and then there is simply racism in the company. I simply know young people who run away because they simply cannot stand what they encounter there, and no one is there to mediate” (18:19). The lack of inclusive openness of companies is also related to a lack of experience and diversity-sensitive competencies, as is repeatedly co-constructed as a main barrier in the workshops. There are also companies that exploit young refugees as cheap labor. For example, there are reports of long-term internships during which employers keep raising hopes for a training position that, eventually, is not granted.

At vocational school, young refugees experience being clearly underestimated, as evidenced by teachers tending to focus on their presumed deficits. In addition, the existing unequal treatment and hierarchization of different groups of refugees also leads to conflicts at school.

Discrimination on the part of authorities often manifests itself in the form of arbitrariness, unequal treatment in connection with residence law or the recognition of competencies, prejudices on the part of employees, poor communication, and linguistic discrimination, to name a few (see section 4.1).

One participant illustrates the central goal regarding racism and discrimination: “This social equality, we just have to get better at. And it does not matter what social discussion you are having, whether it’s migration, disability, whatever. The bottom line is always the same, that people need to treat people equally” (45:13). Another important prerequisite is more equality before the law, which also means that there should no longer be any hierarchization of refugees depending on their origin, which is made relevant to the new arrival of Ukrainians (Brücker et al., 2022), who get easier access through different legal frameworks and experience less discriminatory practices. Since the legal framework conditions are difficult to change, the participants focus on practical approaches that can be implemented on the local level, such as municipal inclusion and integration concepts that focus more on the issue of racism. This is linked to the demand to consider and take up anti-racism and anti-discrimination work as a network task of different stakeholders.

Due to the limited social contact between long-term residents and refugee newcomers it is suggested that social encounters should be increasingly facilitated through various formats. At the institutional level, it is important to promote intercultural competencies through training, events, and increased public relations work.

The establishment of an independent anti-discrimination office as a contact point for those affected, and as an important factor in the fight against racism and discrimination in general, is mentioned as an important measure. Especially regarding public authorities, there is also a need for an institutional and independent complaint management.

4.2 Head scarfs, childcare and safety nets – training facilities, language and gender

The following problems arise in relation to the institutionalized form of vocational training in Germany: The necessity to earn more money than offered by the apprenticeship salary during vocational training can be more important for the refugee training than the long-term value of education, so this becomes an educational barrier. For young people, it is not always easy to convey the value of education and the related effort. However, VET leads to higher, long-term income and serves as a kind of “safety net” (Ebner, 2015): “But the young people… often do not know or aren’t aware that if they want to earn decent money or achieve more, then vocational training is the basic requirement” (46:44).

The financial aspect, which creates an important incentive for vocational training in contrast to non-paid academic education, does not apply to young refugees due to “financial constraints” resulting from the need to support their families abroad. The same is valid for the duration of the training, which is considered as too long. The vocational prospects are not tangible in the present, and from the perspective of a young person, 3 years of training seems to be a long period of time.

The size of the training company also plays a crucial role (Torfa et al., 2022) in successful training processes. Smaller companies have less resources to support the special needs of refugees and are economically dependent on the performance of trainees.

In vocational schools, cross-cutting issues are illustrated by the workshop participants that particularly pertain to educational barriers in rural areas: (institutional, individual, and structural) language requirements, (non-existent/non-recognized) school qualifications, childcare during training, and mobility as exclusion and dropout criteria. The absence or non-recognition of foreign credentials is discussed as a major barrier for young refugees. Within the vocational schools themselves, staff shortages and the obligation to follow standard curriculum pose significant barriers. The challenges in language proficiency are not only outlined by practitioners but also by the trainees themselves. The fact that vocational training in Germany fails due to insufficient language and vocational school competencies has already been empirically proven (Tratt, 2020; Albrecht, 2023) and is reflected in the discussions during the workshops.

Postponing vocational training to work and earn money is problematized as an individual solution that jeopardizes lifelong integration in the labor market. The increase in apprenticeship pay is also seen as a necessary structural change in the vocational training system. Refugee youth are expected to put aside the pressure to earn money by explaining to them the education and labor market system in Germany, with the positive long-term prospectives: “Will you help your family? Then pursue a good vocational training, yes, and then you can soon send money back to your home country” (46:62).

To strengthen the responsibility and pro-activity of the training companies, various aspects are being negotiated as additional on-the-job offerings and improvements, such as language support, tutoring, higher salary, support for mobility and housing, supporting networks, and innovative initiatives (Torfa et al., 2022). The personnel commitment of training companies is highlighted through success stories. For example, refugee trainees are allowed to attend language courses in working hours. This reflects the changing strategies of companies to become attractive employer and to take social responsibility seriously (Einwiller et al., 2019) also for refugees (Baethge, 2014) by expanding and developing intercultural competencies (Vogel and Scheiermann, 2019).

Teachers and practitioners in vocational schools are interested in support from other “non-school institutions” by improving language proficiency and integration into the German society, communities, and social networks. A language-focused schooling in separate classes is advocated, although current research shows that this likely results in early dropout or non-attendance by the students because of the double load of work and learning (Crul et al., 2019). Another attempt to provide support that addresses childcare during training was made by a vocational school in one of our Brandenburg counties that has already established a daycare facility on their campus.

Language barriers in training occur at different levels: directly in the training, both in the vocational school and in the company, and as an access barrier to society in general. Insufficient language and vocational school skills often lead to dropping out of VET (Tratt, 2020). At the same time, organizational difficulties with language courses and access are also described by workshop participants. In Germany, in particular, high expectations are placed on the correct and precise use of language.

The challenge of language proficiency during VET is twofold: On the one hand, trainees must learn technical terms and understand theoretical contexts (Vogel and Scheiermann, 2019). A central barrier in training arises from the focus of the educational system on technical and theoretical knowledge, neglecting, at the same time, the insufficient language skills of the refugees as a pre-condition for learning. One trainee articulates the following: “Yes, so I had that problem too during my training. I could not speak German well from the start, and then I had different subjects, different fields of study that I had never heard of before, like WISO [economics and social sciences]” (30:2). The necessity to invest time and effort into learning German and into vocational training becomes a double burden to cope with. The young people usually do not fail in the exams of their training programs because of insufficient knowledge but because of a lack of language skills. Language as an educational barrier is also not taken into account by the different chambers that administer the exams—e.g., by extending the exam time.

On the other hand, even the trainees complain that their language competency is not sufficient to adequately communicate in business life, not only in conversations with customers but also among employees. Young people report that they do not even have the confidence when it comes to talking to customers. Language, thus, becomes a general barrier to accessing society, especially when refugees are confronted with the expectation of accurate usage of the German language. In rural areas, this is exacerbated by the fact that people often use the local dialect: “But I think especially in the training sector, in the trades, they just use the gibberish without taking it into account” (45:58). On the part of the trainees, not being able to sufficiently follow a conversation leads to discouragement and speechlessness.

Language education in schools for young people whose first language is not German has been criticized as insufficient (Söhn and Özcan, 2006). A social worker explains, “We have a lot of young people who have really started training and drop out because they just do not understand. And they do not learn German in the vocational school” (18:15). As a solution to the problem, trainees take external language courses, which, at the same time, reinforce the separation of language and vocational education (Korntheuer et al., 2018a).

Furthermore, the organization of and access to German courses by state programs beyond vocational schools are inadequate. Many refugees are not able to attend them because mandatory shelters are remote from the next villages (see section 4.1) and, therefore, do not have a sufficient command of the language, despite having lived in Germany for a long time. This is even more relevant in rural areas because of mobility restrictions. In addition, bureaucratic regulations, which determines that teachers can be hired only with a certified qualification in “German as a foreign language,” prevent a sufficient supply.

In vocational training, priority is given, in particular, to the learning of content, while the teaching of language skills remains inadequate. Vocational school curricula and schedules are still exclusively focused on the qualifications that German trainees bring with them. Instead, more emphasis should be placed on language acquisition already at school. In addition, the organization of cultural leisure activities—sports clubs, choirs, creative workshops—can create meeting places that facilitate German language learning. Finally, intercultural competence needs to be developed in rural areas increase the sensitivity of institutions for the special needs and problems of young refugees, including language learning [Bundesinstitut für Berufliche Bildung (BIBB), 2020].

Particularly the category “woman” is discussed from a gender perspective as a decisive barrier to education in relation to “childcare” and “wearing a headscarf.” The under-representation of women with forced migration experiences, which already appears in secondary education [United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 2018], continues in vocational education.

The headscarf as a signifier for backward-oriented, traditional, and religious orientations of women (Hametner et al., 2021) is often brought up as a gendered barrier to education in the workshops. Othering becomes an explanation for intercultural reservations, especially in companies, so that girls and women are not accepted into vocational training. The workshop participants complain in general about rejection, exclusion, discrimination, and racism against non-Germans, explained by the low level of experience in dealing with cultural diversity in rural areas. A peer researcher reports on her own experience.

“In my village it is also the case that if you see a person, for example one now in a company, who wears a headscarf, everyone asks themselves: ‘What should we do now’, so to speak? ‘I have not seen anyone wearing a headscarf yet’” (44:29).

Cultural prejudices are especially relevant for east Germany, where migrants who do not comply with the appearance of Western Europeans was virtually non-observable in the public until 2015.

Another gender-specific barrier to education for girls and women is the special responsibility for childcare and care work. “Caring responsibilities” was identified by Burke et al. (2023) as a central barrier to access tertiary education, which Sharifian et al. (2021) also interpreted as a “sociocultural barrier.” The connection between caring, time-consuming mobility and insufficient childcare creates complex coordination tasks, which even increase when women also take up vocational training, a job or even a language course. One social worker complains, “Yesterday, for example, I had a woman she came from Village A—who now has to wait 2 years for a place in a childcare center. How is she supposed to do a German course?” (23:44).

Rejecting both gendered discrimination as well as racism and cultural discrimination is seen as the central strategy to overcome educational disadvantages caused by the intersectional overlay between gender and racism. “But one thing was that it was a bit linked to these headscarf reservations. That education is, in a utopian idea, an absolutely discrimination-free space, and everyone can profess their religion or whatever” (22:3).

Despite the legal right to childcare in Germany, it remains insufficient to serve the needs in rural areas for all parts of society. The workshop participants complain about the inflexibility of the authorities in setting up care close to place of residence or training. For the further development of good practice, participants discuss that childcare must fit to the individual demands of the women, consider their mobility needs, and be located close schools and workplaces.

4.3 “… that magic word: bureaucracy” – immigration policies and regulations

Asylum and migration laws and policies are mentioned throughout the real-world labs as constant and important obstacles for successful training pathways. The way a practitioner puts it with a certain sarcastic undertone: “We have been talking about it all day long: laws and policies […] you know just these typical restrictions in Germany that we are struggling with on an everyday basis. […] that magic word in Germany: bureaucracy” (23:51).

The Asylum Seekers Benefits Act, residence obligations, and residency requirements, exclusion from language learning and educational support programs based on the lack of a permanent residency, insecurity of residence with the so-called tolerated status and ineffective or inaccessible policies for the recognition of foreign credentials are among the most frequently mentioned structural obstacles. Complex and restrictive residence laws intersecting with educational pathways are well established as barriers for refugee students and trainees in educational research in Germany (Korntheuer et al., 2018a; Vogel and Scheiermann, 2019). In the real-world labs, these barriers are co-constructed, in reference to the “typical” German feature of dense and restrictive policy practice and intense bureaucracy.

Navigating the ever-changing laws and bureaucratic processes of authorities poses challenges not only for refugee trainees and our peer researchers but also for educational practitioners and training companies. A complex network of authorities—including the foreigners’ office, job center, labor office, youth office, agencies for recognizing foreign credentials, social services, and educational administration—adds to the difficulties. For smaller and medium-sized companies, bureaucratic and residency requirements present significant hurdles. Training a refugee youth without permanent residence may be viewed as a risky investment due to the potential for deportation. Regulations further contribute to challenges, leading to exclusion from language courses and support programs for youth without permanent residence or those still living in shelters during apprenticeship.

Not only are the responsibilities and bureaucratic process hard to navigate, but authorities also lack language support, intercultural sensitivity, and goodwill to effectively support the refugee trainees. The term “blockade,” as an institutionally created and insurmountable inaccessibility of authorities, is stated several times and at different real-world lab sites in this context. Getting beyond the “blockade” seems only possible when an educational practitioner or a German volunteer comes along for support, a result that is supported by further studies (Huke, 2020). Furthermore, appointments are very difficult to schedule and, in some cases, only possible during the hours of training and vocational school.

The lack of communication and information transfer between authorities and institutions can also turn into barriers. There are likely to be underlying differences in institutional and structural objectives, including securitization versus educational integration, which lead to conflicts of interest with a strong impact on the individual level of trainees.

The lack of recognition of foreign credentials and educational certificates stems partly from lack of information and complex systems. Not having credentials or work experience recognized can lead to the acceptance of less qualified jobs or occupations in a field of work outside personal interests, this situation is critically questioned by some practitioners.

Some of the participants call for legal changes in asylum and residence law as well as in social benefits at the federal level. At the same time, however, there is irritation as to whether this is the right level at all, or at which level practice development can and should be considered. The reasons for the lack of accessibility are either discussed as individual or structural and institutional. On the individual level, motivated and courageous people in public authorities are named as a starting point for an improved accessibility or, alternatively, a person that acts as an “navigator for authorities.” On a more institutional and structural level, different aspects are summarized under the term inclusive opening processes as a practice goal:

The first was multilingual information sheets and forms and then as a second easy language, as a third interpreter/ language mediator pool or translation devices, training and education for staff, and open office hours. We had digitalization of the forms and explanations […] multilingual staff and a complaints office/quality management (50:54).

To overcome the “blockade” of authorities, it is necessary to exercise some pressure through public relations and directly reach out to the authorities again. Results and networks of laeneAs might be a starting point to do so. The co-construction of barriers and improvements for practice move far beyond educational institutions and processes. In their discussion of the official and bureaucratic hurdles, various participants state clearly that individual deficits cannot be assumed here and that these barriers should not be seen as a “failure” on the part of the young people but rather as structural conditions that hinder successful training pathways.

5 Conclusion: exclusionary conditions on a structural level and good intentions of local practices

The main findings of the study can be summarized as follows: The educational landscape in the counties is characterized by the contradiction of exclusionary conditions at the institutional and cultural level, while at the level of local practice, there is a strong commitment to creating inclusive educational pathways. In the workshops, we collected rich data on how educational barriers and inclusion were discussed and defined by the participants, who were stakeholders at formal (schools, training companies, chambers) and non-formal (social work, counties, and administration) educational institutions and refugees in training. Insufficient infrastructure and restrictive immigration policies are identified as the central barriers to education. A complaint of the participants was that the key problems and challenges of inclusive education are insufficiently addressed because of lacking contacts to decision-makers: federal and state politicians in the respective ministries and administrations. Solutions are, therefore, negotiated at a more intermediate and micro level of practice. Against these barriers, the importance of social work and local networks is always emphasized in the real-world labs as key for successful education and inclusion.

In summary, two strategies in the German integration regime can be juxtaposed, which, although interlocking in a contradictory way, are both expressions of political decision-making and funding. On the one hand, restrictive immigration policies and regulations, which go hand in hand with rural areas characterized by a lack of experience with a diverse population, embedded in general attitudes of racism and discrimination, are identified in the workshops. On the other hand, there are state inclusion strategies to bring “legitimate” migrants into education, which are implemented with great commitment at the local level by the actors participating in the real-world labs (Figure 4).

5.1 Interacting educational barriers

The overall framework in which educational barriers for refugee trainees are embedded is characterized by immigration policies and regulations that are implemented in the form of an obstructive and exclusionary bureaucracy and lack of an inclusive culture of authorities and institutions. Especially in the cultural context of rural areas, experiences and competences with cultural diversity are rather low. It is also reported that the integration efforts and educational aspirations of refugee trainees are often not supported or even blocked by the foreigners’ office, the employment office, the labor office, the youth office, the authorities for the recognition of foreign qualifications, the social services, and the education administration. This also reflects a lack of inclusive openness and intercultural competence on the part of local authorities, training companies, and vocational schools. The peer researchers, in particular, and the actors from local authorities and social work, point to the discouragement and shame in the face of experiences of unequal and disrespectful treatment as well as racist and dismissive behavior.

More generally, the experience of restrictive immigration policies and regulations is framed by the infrastructural challenges of rural areas. For instance, with inadequate public transport, mobility in rural areas can only be achieved through individual transportation. But driver’s license and a car are mostly unaffordable for the refugees because of low salaries during training. Starting vocational training is difficult if the company is not in the immediate vicinity of the assigned accommodation, especially if the residence policy in the county is restrictive and does not allow moving to another place. The issue of reduced mobility is also linked to inadequate accommodation. Refugee shelters are often built in remote areas with little or no public transport so that access to education is difficult to achieve. Without owning a home, the trainees lack a basic space to retreat to study and to recover from an eight-hour working day.

Insufficient language competencies become major barriers for the refugees from successfully completing their vocational training. Living in shelters isolates them from the German population, reduces the opportunities to train German, and psychologically burdens the trainees. Language courses quite often do not serve the special needs and existing language skills of the trainees, in particular, considering the challenges in rural areas—limited mobility, too few refugees to initiate language courses, lack of qualified teachers. Finally, gender is a category that is intersectionally interwoven with ethnicity and racism and acts as a decisive barrier. Stigmatization and discrimination as well as traditional representation of gender roles leads, finally, to an under-representation of refugee women in vocational education.

5.2 Supportive institutions and good practices for an inclusive education