- 1School of Early Childhood and Inclusive Education, Faculty of Creative Industries, Education and Social Justice, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 2School of Education, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup, WA, Australia

- 3School of Education, Faculty of Arts, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 4Department of Early Childhood Education and Care, Faculty of Administrative, Economics and Social Sciences, University of West Attica, Athens, Greece

- 5Faculty of Education and Human Development, The Education University of Hong Kong, New Territories, Hong Kong, China

The National Quality Framework (NQF) was intended to drive continuous improvement in education and care services in Australia. Ten years into implementation, the effectiveness of the NQF is demonstrated by steady improvements in quality as measured against the National Quality Standard (NQS). The process of assessing and rating services is a key element in the NQF, drawing together regulatory compliance and quality assurance. This paper draws on findings from a national Quality Improvement Research Project investigating the characteristics, processes, challenges and enablers of quality improvement in long day care services, concentrating on Quality Area 1 Educational program and practice and Quality Area 7 Governance and leadership. This was a mixed-method study focusing on long day care services that had improved their rating from Working toward NQS to Meeting NQS or to Exceeding NQS. The study comprised three phases, and in this paper, we draw on Phase 3 to understand the contribution of the NQS Assessment and Rating (A&R) process to continuous quality improvement from the standpoint of providers and professionals delivering these services. Phase 3 involved qualitative case studies of 15 long day care services to investigate factors that enabled and challenged quality improvement. Data was collected during two-day site visits, using professional conversations and field notes to elicit the views and experiences of service providers, leaders and educators. In this paper, we look at how the A&R process is experienced by those involved in service provision, with a focus on the factors that enabled and challenged quality improvement. Recognizing the interchangeability of enablers and challenges, three broad themes emerged: (i) curriculum knowledge, pedagogical skills and agency; (ii) collaborative leadership and teamwork; and (iii) meaningful engagement in the A&R process. The study found that meaningful engagement in the A&R process informed priorities for ongoing learning and acted as a catalyst for continuous quality improvement. Apprised by stakeholder views and experiences of A&R, we offer a model to foster stakeholder participation in quality assurance matters through affordances of meaningful engagement.

Introduction

Regulation and the establishment of quality standards frameworks continue to be used by governments across the world as key policy levers to professionalize the early childhood workforce and to improve the quality of early childhood education and care (ECEC) (OECD, 2018; Hotz and Wiswall, 2019; Melhuish and Gardiner, 2019; UNICEF, 2019). Widely viewed as an artefact of neoliberalism (Sims and Hui, 2017), the efficacy and impact of government-led quality assurance frameworks in realizing these goals has been questioned. Common areas of concern relate to the role of regulation in setting minimum quality standards; the tendency to focus on structural quality elements that are more easily quantified and measured (Slot et al., 2015; Moloney, 2016); and the potential for regulation to lead to universal, isomorphic and narrow definitions of what constitutes quality practice (Bourke et al., 2018). The collective impact is often seen to be promulgation of a technical view of the work of educators, contrary to the espoused policy intent to support and strengthen professional identity and practice within the ECEC workforce (Fenech et al., 2006; Sims and Waniganayake, 2015). Acknowledging these concerns, the potential contribution that policy and regulation can play in raising quality and supporting a professional ECEC workforce has also been recognized.

The role of regulation in laying the groundwork for structural quality elements that are known to contribute to process quality and improved child outcomes has been established (Wangmann, 1995; Slot, 2018). Advocating the importance of a qualified ECEC workforce, Goffin (2015) argues the need for greater consideration of the role that state governments play in promoting and supporting a professional workforce through certification and licensure. Examining the Australian National Quality Standard [NQS] (ACECQA 2011), Siraj et al. (2019) concluded this fulfills three important functions: (i) drawing attention to factors that influence service quality, (ii) ensuring a minimum quality threshold across the ECEC sector, and (iii) potentially providing quality improvement processes and tools to support services to work toward higher quality provision.

It is also important to acknowledge change and improvement in systemic approaches to regulation and quality assurance in ECEC, and the emergence of various models and approaches globally. For example, many previous critiques have pointed to the limitations of detailed and prescriptive regulatory tools and approaches (e.g., Slot et al., 2015; Pianta et al., 2016). Australian leader in quality assurance Wangmann (1995) advocated the need for regulation and a national accreditation system to drive quality improvement, paving the way for the current integrated National Quality Framework [NQF].

Over recent years, there has been increased attention to the characteristics of effective regulation and standard setting in ECEC. The recent OECD policy review entitled Quality beyond regulations (2018–2022) examined ECEC policy approaches in a selection of OECD countries, including Australia, Ireland, Luxembourg and Sweden to “identify and discuss the main policy levers that can enhance process quality” (OECD, 2022, 1). Governance, standards and funding is identified as one of five key policy levers to improve quality in ECEC, sitting alongside curriculum and pedagogy, workforce development, data and monitoring, and family and community engagement. The review offers “policy pointers” (p. 3) to inform the design and implementation of effective regulation and quality assurance systems. Key considerations include ensuring a comprehensive and coherent framework that addresses all ECEC services; building in a strong focus on process quality; building shared understanding of quality standards; promoting self-evaluation and a culture of continuous quality improvement; optimizing the use of data to improve quality; and facilitating the voices of parents and children in quality assurance processes (OECD, 2022, 3–4).

Drawing on the broader literature on effective regulation and quality assurance processes in education, there is also general agreement that standards need to address the key determinants of quality, be informed by contemporary theory, research and practice, and be subject to regular review and updating (Tayler, 2011). Emphasis is also placed on regulatory tools and processes that enable professional autonomy and agency within the local ECEC context (Irvine and Price, 2014) and extend beyond the identification of quality inputs to describe quality in terms of children’s experiences and outcomes (Jackson, 2015). Importantly, as highlighted by Bourke et al. (2018), it is also not just about the mandating of quality and/or professional standards, but how they are understood and used. For example, are standards seen as regulatory or developmental or perhaps a combination of both approaches?

The assessment and rating of practice through state-based and national quality rating and improvement systems is a common feature of regulation and quality assurance in many countries (Harrison et al., 2019). Australia’s NQF offers one contemporary example, that includes a national Assessment and Rating (A&R) process. Despite the expanded use of quality rating and improvement systems in government-led quality assurance practices, there is a paucity of research on their use and impact on professionalization and quality improvement goals in ECEC. Recognizing the efficacy of top-down policy is determined at the local level (McLaughlin, 1991), this study explores the contribution of the National Quality Standard (NQS) and its associated Assessment and Rating (A&R) process to continuous quality improvement in Australian long day care services, from the standpoint of providers and professionals delivering these services. The study seeks to deepen understanding of the challenges and barriers to quality improvement in long day care, alongside strategies and supports associated with meaningful and sustained quality improvement.

Australia’s national quality framework

Australia has a strong track record in quality assurance in ECEC (Ebbeck and Waniganayake, 2003), implementing the world’s first national Quality Improvement and Accreditation System (QIAS) in 1993 and celebrating almost three decades of national standards and quality assurance in ECEC. In the 1990s, Australian researcher and architect of the QIAS June Wangmann advocated the need for a comprehensive and integrated approach to quality assurance in ECEC. Underpinned by her research into contributing and determining components of quality, Wangmann (1995) argued the value of legislated minimum national standards and a quality framework that promoted and supported services to adult-child quality. Aligning to structural quality factors, contributing components were seen to provide “the most favorable conditions in which good quality outcomes are most likely to ensue” (Wangmann, 1995, 74), and could be generally addressed in regulation. Aligning to process quality, determining components focused on adult-child relationships and interactions, and partnerships with families, aspects more difficult to address in regulation. Drawing on this distinction, Wangmann (1995) observed the need for both regulation and accreditation, arguing that each addressed distinct but complementary functions. The QIAS introduced a four-point quality rating scale, designed to support quality improvement and to assist parents to make informed ECEC choices. While marking a significant landmark in Australian ECEC, the QIAS was limited to long day care services, built on state-based legislation and regulations.

Building on this solid foundation, and informed by contemporary policy and research perspectives, the introduction of the NQF in 2012 marked another important milestone in Australian ECEC (Irvine and Price, 2014; Jackson, 2015). Drawing on the recent OECD (2022) review as a point of reference, key changes in Australian regulation and quality assurance included: the move from separate state-based regulation and licensing to a national law and regulation; the integration of minimum regulatory standards and higher quality aspirational standards within one National Quality Standard (NQS); expanded scope to include all ECEC services, including some previously excluded services such as state-funded preschools and kindergartens; and establishment of the Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA) to oversee the NQF and drive quality improvement, working with all levels of government. Our analysis is that the NQF addresses most of the policy considerations for “building strong quality assurance systems for ECEC” (OECD, 2022, 3), supported by a public commitment to ongoing review and improvement of ECEC quality policies and practices.

Promoting the importance of early learning (Siraj et al., 2019) and the professional work of educators in ECEC (Irvine and Price, 2014), the NQF strengthened the focus on process quality (Tayler et al., 2013), with an emphasis on educational programs and practices (Jackson, 2015). This is supported by two national Approved Learning Frameworks, and introduction of the ‘educational leader’ role to lead the educational program at the ECEC service. Acknowledging the influence of context on quality practice, the NQS places emphasis on educators exercising professional autonomy and judgment and applies performance-based standards (Irvine and Price, 2014). In this way, the NQS goes “beyond the process to the outcome that is achieved (Jackson, 2015, 517), focusing attention on children’s experiences and outcomes. Reflective of performance standards approaches, the NQS promotes quality practice, informed by theory and research, but stops short of prescribing what this looks like (ACECQA, 2022a).

The NQS A&R process is promoted as a key contributor to realizing continuous improvement. All ECEC services in receipt of public funds, including parent fee subsidies, are required to participate in the NQS A&R process. Drawing together regulatory compliance and quality assurance, ECEC services are assessed against the seven quality areas of the NQS: QA1 Educational programs and practices; QA2 Health and safety, QA3 Physical environment, QA4 Staffing arrangements, QA5 Relationships with children, QA6 Collaborative partnerships with families and communities, and QA7 Governance and leadership. Promoting self-evaluation and a culture of continuous quality improvement (OECD, 2022), there are two interrelated tools designed to support critical reflection and evaluation of practice: (i) the Quality Improvement Plan (QIP) which is developed by the ECEC service and (ii) the A&R Report which is developed by the Regulatory Authority.

Under the NQF, all ECEC services are required to develop and maintain a QIP. While the format may vary, all QIPs are expected to include an evaluation of service policies and practices against the NQS and National Regulations, identify current strengths as well as quality priorities, strategies and progress toward improvement. The QIP must be readily available at the service to parents, regularly updated, and is used by the Regulatory Authority in assessing the quality of the service. The QIP is reviewed by a trained assessor, who undertakes a site visit (generally 1–2 days depending on the size of the service) and gathers evidence of quality through observation of practice, discussion with providers and educators and review of documentation. Assessors use an agreed digital tool (NQS Assessment and Rating Instrument 2020), collect evidence and rate each quality area leading to an overall service rating, and prepare an Assessment and Rating Report for the service, which includes the service rating. Like the QIP, there is consistency in the areas addressed within the Assessment and Rating Report, however, some jurisdictional differences in approach are evident (Harrison et al., 2019), including the report format, level of detail and descriptions of practice, and inclusion of suggestions to support quality improvement.

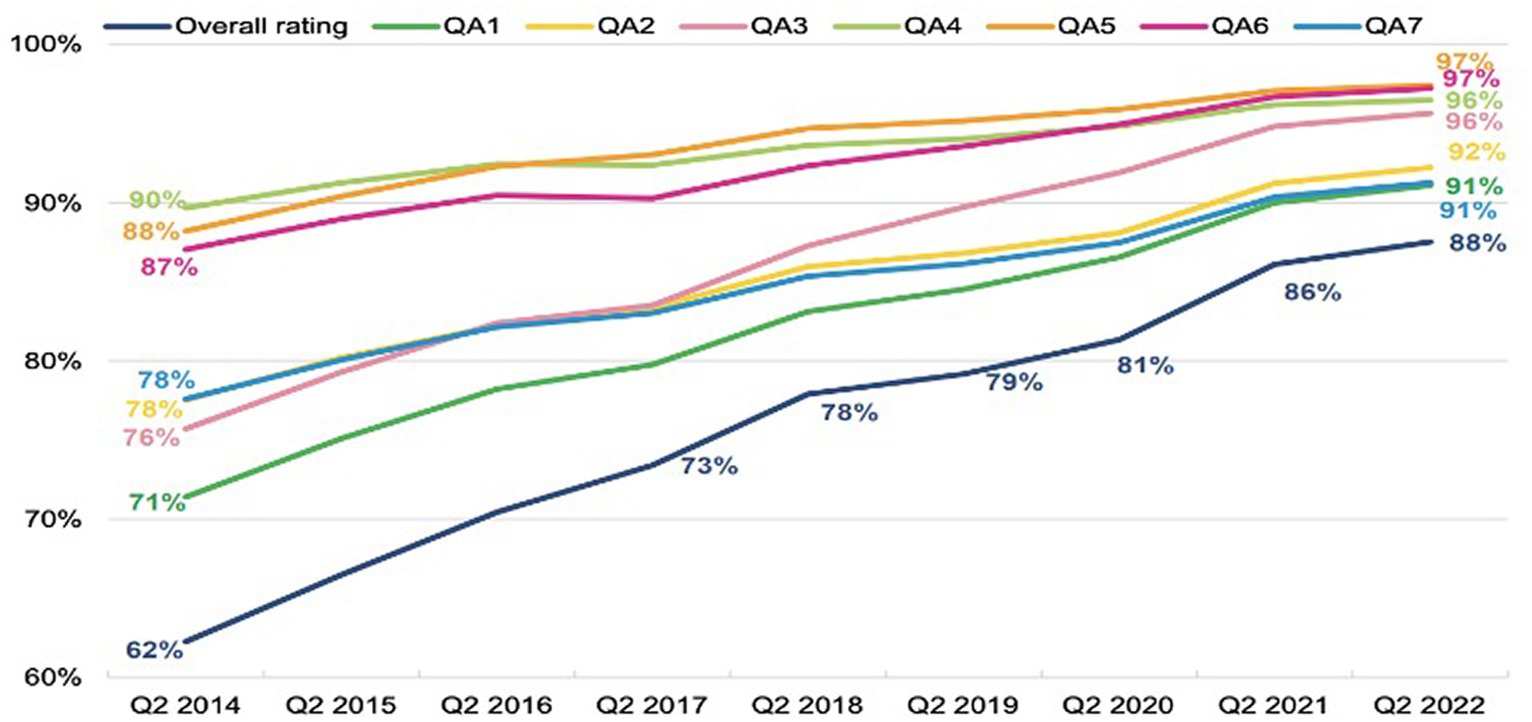

Ten years into implementation, the effectiveness of the NQF is demonstrated by steady improvements in quality as measured against the National Quality Standard (NQS). See Figure 1 for the proportion of services rated Meeting NQF by overall rating and quality area.

However, little is really known about the role and contribution of the NQS A&R process to the overarching goal of continuous quality improvement, within individual services and at the broader systems level. Drawing on findings from a national Quality Improvement Research Project (Harrison et al., 2019) investigating quality improvement in Australian long day care services, this paper addresses this gap. This research team investigated how the A&R process is experienced by those involved in service provision, with a focus on factors that enabled and challenged meaningful engagement, sustained quality improvement and an improved quality rating.

Research design

The design of this research has been influenced by a socio-cultural epistemology where knowledge and understandings are constructed and negotiated in the everyday contexts of the participants (Creswell and Creswell, 2018). Vygotsky (1978) claimed that our understandings are shaped by our own comprehension of our social, cultural and historical backgrounds and realities are conceptualized as complex and socially constructed. Therefore, the researchers used methods to generate meaning about individual participants’ experiences within context, recognizing that individuals may have different experiences of the same phenomena, in this case, the A&R process.

The overarching study comprised three sequential phases and applied a mixed-methods approach (Creswell, 2015) to investigate quality improvement in long day care services. The aim was to identify the characteristics, processes, challenges and enablers of quality improvement in long day care services that had achieved a higher quality rating over two successive assessments. ACECQA who commissioned this project chose two of the seven quality areas in the NQS to study: QA1 Educational program and practice and QA7 Governance and leadership. These two areas were selected based on longitudinal data suggesting high correlation with quality improvement (ACECQA, 2022b).

Briefly, the three phases comprised: (i) Statistical analysis of the characteristics of 1,936 long day care services that had achieved improvement from Working towards NQS to Meeting or Exceeding NQS, drawn from the National Quality IT system dataset (Harrison et al., 2023); (ii) qualitative analysis of deidentified QIPs and Assessment and Rating Reports from 60 long day care services from the Phase 1 pool, representative of the diversity of the sector (Davis et al., 2023; Hatzigianni et al., 2023); and (iii) multiple case studies (Stake, 2006) focusing on quality improvement in 15 long day care services (see Harrison et al., 2019, 2023 for a detailed description of the study design). In this paper, we report on findings emerging from Phase 3 of the study which investigated the following two research questions: (i) What are the challenges and barriers associated with quality improvement? and (ii) What are the strategies and additional supports that promoted quality improvement in long day care services?

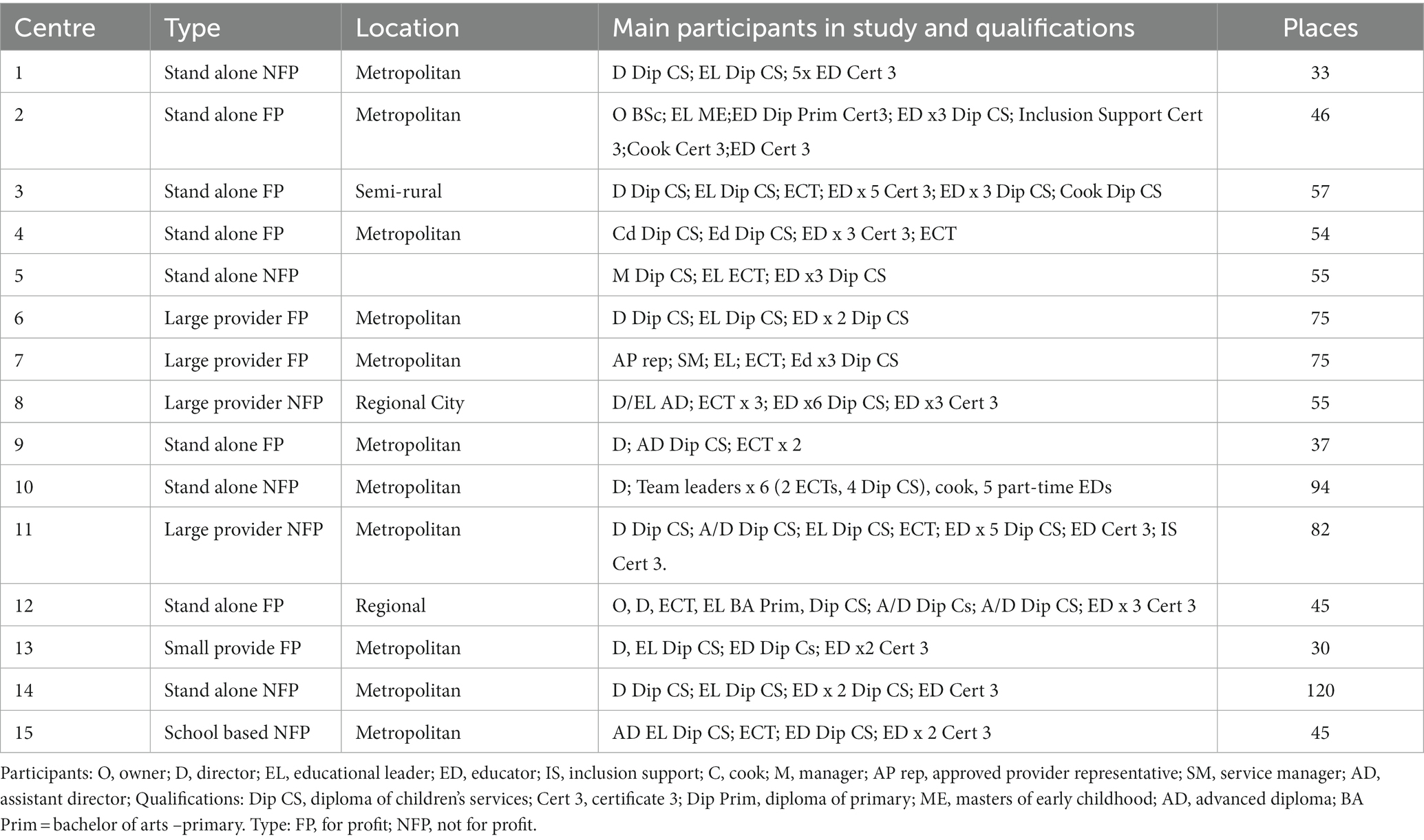

Drawing on the Phase 1 dataset and findings, a process of purposeful selection was used to recruit 15 long day care services, reflective of the diversity of services across Australia (e.g., jurisdiction, type of provider, size of provider, community disadvantage), excluding services that participated in Phase 2 of the study. Table 1 provides an overview of demographic details for the case study sites and participants. The study was undertaken by a team of 10 researchers, from four universities located in different Australian states and territories. Leveraging the location and contextual knowledge of team members, one member of the research team was linked to each case study site. The researcher spent 2 days on site in each service and engaged in observations and professional conversations (Irvine and Price, 2014) with a cross section of stakeholders (i.e., approved provider, service leader, educational leader, early childhood teacher and educators). These were individual conversations, undertaken in a quiet private space within the long day care centre. Researchers sought to investigate stakeholder views and experiences of the A&R process and enablers and challenges associated with quality improvement. Examples of questions included:

• Looking at QA1 Educational programs and practices, what did you focus on and why?

• Who was involved? Why?

• What areas of your work did you feel most confident about? Why?

• What areas, if any, were you concerned about? Why?

• What do you think had the greatest positive impact? Why?

Hand-written field notes and an agreed case study template assisted in the development of a detailed case study report for each of the 15 services. This was returned to the ECEC service for review, edit and verification. The 15 de-identified case study reports were then shared with the whole research team. Individual researchers independently engaged in a process of thematic analysis to derive first impressions of challenges and barriers, strategies and support to quality improvement within and then across the case studies. Equipped with their individual analyses, the whole research team met in person for a full-day collaborative thematic meta-analysis discussion, facilitated by an expert early childhood researcher as a critical friend.

In this paper, we focus on the analysis of the case studies to explore the contribution of the NQS A&R process, including the Quality Improvement Plan and Assessment and Rating report, in driving and supporting continuous quality improvement within individual services and at the broader system level.

Findings

Our primary interest was the service approach to, and lived experience of, assessment and rating. Concentrating on QA1 Educational program and practices and QA7 Governance and leadership, we look at the challenges and barriers providers and professionals associated with quality improvement, and the strategies and additional supports they perceived had led to sustained quality improvement, evidenced by an improved quality rating.

Findings are discussed under three broad themes: (i) curriculum knowledge, pedagogical skills and agency; (ii) collaborative leadership and teamwork; and (iii) meaningful engagement in the Assessment and Rating process. There was some variation across the case study sites as to whether these themes presented as challenges or enablers, and evidence of a challenge being resolved to become an enabler across the two points of assessment. As such, under each theme, we discuss challenges and barriers alongside strategies and supports for sustained quality improvement.

Curriculum knowledge, pedagogical skills and agency

Across the case studies, QA1 was commonly described as the ‘most important’ and ‘most challenging’ area within the NQS. It was also widely considered to be the starting point to drive quality improvement. Recognizing the holistic and integrated nature of the NQS, some participants advocated the benefits of focusing on QA1 in terms of the impact on other quality areas, in particular, QA5 Relationships with children and QA6 Collaborative partnerships with families and communities.

“It’s all about QA1” and “QA1 demands time”, “it’s about building knowledge and confidence” (EL, CS7).

There was a strong shared focus on promoting children’s learning, development and wellbeing, and the starting point for most was building deep knowledge and understanding of the national Approved Learning Framework.

“The planning focussed on the EYLF and knowledge of the NQS [including EYLF] was given as the most important change from the first to second rating” (EL, CS15).

Notably, one service leader reflected that the assessor had encouraged the service to focus on QA1 in preparation for A&R and felt this had been good advice. She reflected that the team focussed on QA1 for 12 months, “learnt it together” and that “having only one area to focus on made it easier in a way for the staff” (CD, CS14). She attributed the service’s award of Exceeding NQS to having time to explore, to engage in team conversations and to think more deeply about their practices, with impact on all areas of their professional work.

Closely aligned to building curriculum knowledge, was strengthening pedagogical skills, in particular the planning cycle - observing, assessing, planning, implementing and evaluating children’s learning (Australian Government Department of Education, 2022). Educators’ understanding and implementation of the full planning cycle was identified as a shared challenge and ongoing priority for professional learning and improvement. In particular, the sometimes adhoc nature of planning, absence of clear connections between observations, planning and assessment of learning, was identified as a barrier to effective learning and teaching. The case studies revealed a range of strategies to build capability, including the introduction of shared templates, mentoring and coaching by the educational leader, peer mentoring and collaborative teamwork.

[A] “key focus has been program training, concentrating on the planning cycle – observe, analyse, plan, evaluate and follow-up. This was supported with the introduction of a template and the expectation that educators would complete “one planning cycle per month per child” (EL, CS7).

[The service focus was] “to close the loop of the planning cycle to describe ‘what’s next’. The Assistant Director described having to go back to the ‘basics’. She said that programming had seemed ‘pretty random’ and she introduced the idea of focus children ‘to make sure no children were missed’” (CD, CS15).

Integral to this goal was building team capability, supporting all staff to contribute to the planning cycle as well as strengthening child voice in planning.

“Being consistent with their planning across all rooms and with all ages of children is the main challenge…. some educators need extra support. They need to go beyond ‘aesthetics’ … They have to realise the links with children’s learning and also try to involve younger children in their planning more” (CD, CS5).

“The voice of children was an area that the Assistant Director said needed to be shown in the planning for the centre. She described the ‘idea of having a program meeting with children… and ask what they want next week’” (AD, CS15).

Involving families in planning and assessment of learning was a focus in some centres. While identified as a shared challenge, some teams appeared resigned to limited engagement, while others continued to explore and experiment with ways to facilitate family input in planning and assessment of learning.

“While consultation with families has met with limited success, the use of technology is being explored as a more contemporary way of informing and connecting with them” (CD/EL, CS10).

Across the case studies, capacity to engage in critical reflection was identified as a barrier to improving practice, and there was a strong focus on teaching critical reflection as part of the planning and assessment cycle. In this context, emphasis was placed on using professional conversations to support educators to think more deeply about their practice, i.e., what they do and why. Interestingly, an explicit goal here was to build educator confidence and ability to articulate their professional practice to a variety of audiences (e.g., colleagues, families and Authorized Officers during Assessment and Rating).

“The [NQS] assessment picked up planning cycles, so we have been focusing on this and have travelled a distance. So too, training at all levels is focusing on building critical reflection skills to help all educators to ‘look deeper’ and to be able to explain what they do and their reasons for working in that way…‘It’s show me and tell me what you are doing and why’. The intent is to help educators to feel comfortable responding to questions and talking about their practice” (AM, CS7).

“The centre continues to use the critical reflection questions in each room and the critical reflection book to support educators to consider why they operate in certain ways and to explore changes to practice, both in their room and across the centre”(CD/EL, CS10).

Documenting teaching and learning was identified as a continuing source of concern for service leaders and educators, and a shared challenge across the case study services. Several service leaders reported that ‘staff lacked confidence in programming’ and were frequently asking ‘are we writing enough’? Again, there was mention of templates, however, most centres enabled educators to exercise agency in how they used templates and/or documented learning and teaching. The case studies highlighted the important role of approved providers and service leaders in managing expectations and providing the necessary time and support for curriculum documentation.

“‘I don’t want them to write pages, it needs to be meaningful. I don’t want them to be at home all weekend doing paperwork’. Each room has its own style of programming and it is the ‘quality of thinking that is important’ – [it] doesn’t have to be pretty’” (CD/EL, CS8).

“Documentation was a major concern for ensuring improvement… As a strategy, the Director had allocated staff much more time to document children’s learning. All educators were given 2 hours per week and the Educational Leader had a full day with the Director replacing her. The Educational Leader explained this was ‘critical in having time to plan and reflect’” (EL, CS1).

Collaborative leadership and teamwork

Most participants perceived that effective leadership was a key enabler of quality improvement. So, perhaps it is not surprising that building leadership capability was a focus for many of the case study sites. This was particularly evident in services operated by larger ECEC organisations. The focus here tended to be on positional leadership roles, for example, the centre director and educational leader.

“The current management acknowledges the importance of leadership and has had a strong focus on building leadership capacity across the organisation” (CD, CS7).

“Leadership is the key. When you don’t have good leadership you can really see it… I look up to them and take note of what they do and follow in their footsteps” (ED, CS15)

Within this context, emphasis was placed on the role of the educational leader in driving quality improvement (see Douglass, 2019). There were significant differences in how this role was conceptualized, understood, and supported within centres, with some evidence to suggest greater appreciation and investment by approved providers in the role over time.

“In the first A&R, the centre ‘didn’t really have a dedicated educational leader’. [An educator] ‘was thrown into the role at the last minute by the previous management, but had no time allocated for the role’… [Now] ‘There is a spotlight on educational leadership within the centre’… Seeking to support the educational leader ‘to be a good mentor’, the approved provider provides training for educational leaders and the area manager hosts a weekly educational leader network meeting via Zoom. In the case study centre…the educational leader is rostered one regular day per week for the role and perceives her role to be ‘about bringing the team together’” (EL, CS7).

Ensuring the ‘right person’ was appointed to this role was a shared challenge. While there were differences in views about qualifications, this was seen to be about pedagogical leadership, requiring strong pedagogical knowledge supported by effective leadership skills. Some teams reflected on past experience and observed the positive impact of a new educational leader within the centre.

“‘The appointment of a new educational leader brings fresh perspectives to practice’… ‘It’s a learning journey for everyone’… ‘He supports staff to ensure curriculum knowledge is updated and evident in documentation’… ‘He acts as a role model, working alongside educators, demonstrating the use of the agreed planning cycle and the appropriate language in order to embed these in everyone’s practice…’ The educational leader visits the rooms each week and regularly unpacks learning stories and documentation. Changes to programs are overseen by the centre director and educational leader together” (CD, CS10).

The case studies placed emphasis on building shared understanding of the role of educational leader, and team expectations for quality improvement. Key strategies included a clear role description, orientation and induction processes for all staff, and investment in ongoing professional learning and support for the educational leader and team. Some centres also highlighted the need for a unified centre leadership team, characterised by positive and supportive relationships between the approved provider, centre director and educational leader.

Acknowledging the contribution of dedicated and skilled leaders, the case studies pointed to collaborative leadership and teamwork as a critical enabler. Reflecting on different experiences of leadership, participants highlighted the positive impact of leadership that unified the team, facilitated conversations, enabled educator voice and different ways of working – with evidence-informed rationale.

“Given the multicultural diversity of the staff team at this centre, and with ‘lots of staff changes’, many staff remarked about the importance of having time to talk together. Staff spoke about ‘working together and coming up with ideas together’, and ‘team bonding’ through ‘team building activities’… Centre staff felt that ‘together’ they were a ‘strong team’, ‘supportive’ of each other and that using ‘people’s strengths’ can make the difference” (EL/ECT/, CS2).

“Educators described the centre director who also fulfilled the role of educational leader as knowledgeable and skilled. ‘She leads the team, challenges staff, does the leg work, makes work fun’… She plays an active role in stimulating and facilitating professional conversations between educators. ‘There is lots of discussion’. Educators spoke of a leader who ‘works with individuals recognizing their strengths, limitations and family contexts’ and ‘was always there for staff’… ‘She doesn’t come across as the boss, she works with the team. She makes staff feel comfortable and they feel they can contribute’” (ED, CS8).

The approved provider was seen to have a key role to play in establishing and maintaining conditions that supported a positive work culture and environment. Educators spoke about the importance of trust and respect, alongside the provision of time and resources (human and physical) to undertake their professional work and drive quality improvement. The impact of this was a sense of belonging to the centre, resourced learning environments and stable teams who trusted each other and worked well together.

“A positive organisational culture was also a common supporting element for participants… Most of them have been working for the centre for more than 15 years and trust each other. Specific elements of their everyday practice, such as hours of planning, [above ratio] staffing arrangements, strong relationships with parents and self-assessments were also seen as supportive factors for doing well” (ED/EL, CS5).

“There was also strong agreement from both new and old staff… that the owners were ‘friendly and treated everyone with respect’ and were ‘supportive of staff and families’… Many educators noted the owner’s acknowledgment of staff and how they ‘felt appreciated’ and this had contributed directly to their ‘sense of belonging at the centre’” (ED, CS2).

Leadership, support and investment in continued professional learning was seen to be a key contributor to a positive and supportive work environment. The case studies promoted the benefits of strategic and intentional approaches to staff development, that included engagement in external activities (conferences, workshops and networks) as well as optimizing team learning through mentoring, coaching and conversations within the centre.

“The centre director’s inclination to provide opportunities for educators to attend professional learning to improve their practice was seen as very supportive. Staff meeting agendas always include items about the QAs [NQS Quality Areas] for discussion… and also involve critical conversations about how research and theory underpin staff practice. At different times, each educator is asked to reflect on research that impacts their practice and share with the meeting, thus supporting them to make and maintain connections between theory and practice. Casual staff are encouraged to attend and attendance is paid for 4 times per year” (CD, CS10).

“Performance review is not just about performance, it’s about learning and development” (CD, CS8).

We note that leadership wasn’t a focus for all participants. There were a small number of participants, mostly educators, who reinforced their focus on QA1 and other ‘practice areas’, asserting leadership wasn’t their role and ‘they did not have time to think about leadership’.

Meaningful engagement in the Assessment and Rating process

The case studies provided illustrations of what we conceptualize as meaningful engagement with the Assessment and Rating process, with evidence of positive impact on team relationships, collaboration and improved practice. Participants highlighted factors that enabled or constrained their engagement in the Assessment and Rating process, which extended beyond the centre to include relationships and interactions with the Regulatory Authority.

Reinforcing previously identified themes and factors, participants described collaborative approaches to the development of the QIP as an enabler supporting team engagement in planning, implementation and evaluation of quality improvement strategies. In several centres, participants contrasted this with prior experiences where a positional leader was solely responsible for the QIP.

“All staff were involved in the development of the QIP which took place over a year. This was very different to the first time as the previous Director did not include staff in its development” (CD/EL, CS1).

‘‘The staff prepared for the Assessment and Rating by working as a team to develop the QIP. The Centre Director/Educational Leader met with all team leaders and used their input’’. (CD/EL, CS3).

Facilitating educator voice in the QIP was identified as a key enabler to sustained quality improvement, building a sense of shared leadership, responsibility and accountability to drive agreed practice change.

‘‘The current leadership team was keen to ensure that everyone’s voice was being heard in developing the QIP. The owners have trust in staff expertise in delivering good early childhood programs and provided necessary support… In developing the current QIP all staff have one Quality Area as their focus and these were self-identified…An experienced staff member was paired with someone less experienced…At monthly meetings, these staff teams reported on progress to date… Educators spoke of moving away from ‘being told what do to’ with the previous QIP to ‘now being asked for their ideas’” (ED, CS2).

“The development of the QIP led by the director involves all staff. As this document is updated, the director sends sections to each room for comment and suggestions. They attempt to have families comment too. Everyone is encouraged to add comments/questions about processes in the centre” (CD/EL/ECT, CS10).

Importantly, there was a strong focus on using the QIP as a strategic planning tool, to establish shared goals, improvement strategies and track progress toward goals.

“Leaders and some educators reflected that the QIP provides a framework to track ‘the centre’s journey’. ‘It helps you to look at where you have come from and where you can improve’” (ED, CS7).

“The director specifically emphasised the QIP, seeing it as a dynamic report that needs regular feedback” (CD, CS6).

The case studies revealed some differences in how the services conceptualized and prepared for A&R, including within the same centre over time prompted by new leaders and past experience. Differentiating between first and second assessments, several leaders placed emphasis on showcasing quality and improvement in everyday practice.

“The CD/EL said she wanted ‘the [A&R] process to be a positive experience’. She worked with the team and her co-director to be prepared. She guided staff saying, ‘if you don’t think the assessor is seeing your strengths point it out’ and ‘do your normal day – you'll be fine’… Staff of all qualifications cited ‘teamwork’ and ‘conversations during staff meetings’ as important processes in the lead up to A&R … In essence, the philosophy of the centre is that they do not complete the QIP for A&R but rather ‘we do this for the betterment of the centre’” (CD, CS3).

“While there was some discussion about getting things ready for A&R, there was also a general sense of ‘business as usual’. An early childhood teacher noted that she felt ‘what they were doing was right and she tried not to worry about A&R’. Another educator commented ‘there is not a lot of preparation – what you see is what you get’” (ECT/ED, CS8).

While there appeared to be less emphasis on preparation, there was a strong shared focus on supporting educators to engage with the A&R process, in particular, to feel comfortable, confident and able to articulate their professional practice.

“To do well you need to be confident in what you are doing and you need to be able to explain what you are doing and why you are doing it. It’s about showing where you have been and where you are going. It’s not about being perfect. It’s about the journey” (AD, CS7).

Here participants identified the centre’s relationship with the Regulatory Authority and the assessor’s approach on the day as enabling or constraining meaningful engagement. Several participants contrasted their two experiences of A&R, highlighting more collaborative and supportive approaches the second time.

“To prepare for the first A&R process, the centre director and assistant director attended a local information session hosted by the Regulatory Authority… The new A&R process was presented as collegial and supportive, with greater emphasis on observing and discussing practice and less emphasis on documentation. However, this was ‘not the lived experience of this centre’. All educators… described it as a negative experience, attributed to the lack of clarity about what was required, and the compliance approach taken by the assessor. The assessor sat in the corner with her IPAD and did not engage staff or children in conversation. The centre director described it as a ‘lazy visit’… The second A&R visit was a more positive experience, described by one educator as ‘more relaxed and engaging’…largely attributed to the approach taken by the assessor… Educators noted there were more conversations seeking to understand practice and some positive feedback. Several noted they felt ‘more comfortable’ ‘more confident in ourselves’ and ‘able to simply do what we normally do’” (CD/AD/ED, CS8).

“All participants compared the [two] visits and identified important differences. The [first] assessor was not as friendly and made them feel nervous. There were concerns around her professionalism and the usefulness of her queries and feedback. They all agreed the [second] assessment was a much more constructive and positive experience leading to confidence and working harder to achieve better results in the future” (CD/AD/EL/ECT/ED, CS5).

Across the case studies, participants identified the benefits of their engagement in the A&R process, with a particular focus on the contribution of the QIP and A&R report to quality improvement. Service leaders focused on using A&R to ‘unify the team’ and get everyone to look ‘at the bigger picture’ (CD, CS1). Leaders and educators reported ‘feeling closer together’ and being ‘a stronger team’ for having gone through the process (CS3). One educator reflected ‘the process of A&R unified us, and we found opportunities to see each other’s strengths’ (ED, CS4). Many participants commented on the A&R process and report as ‘useful in promoting and supporting continuous quality improvement’ and as a ‘prompt to consider where to next’ (ED, CS8).

“The previous A&R report was used as a basis for quality improvement… ‘The assessment picked up the planning cycles, so we have been focusing on this and have travelled a distance’ (EL)…‘It’s good for the next time we go through it. You see it’s not a lot to get to the next level. It makes you look forward to the next one because you know you can get there’” (AD, CS7).

“The report was really useful in reflecting on current practice and to stimulate conversations about ways to improve” (CD, CS11).

“The Assistant Director described the QIP and the A&R feedback ‘as a compass for myself, I have used all the feedback’” (AD, CS15).

Ultimately though, the case studies pointed to the need to build a centre learning community where all members are supported to meaningfully engage in the Assessment and Rating process, and are open and able to critically reflect upon and evaluate feedback gathered to inform continuous quality improvement.

“The management team drove the changes that were needed in QA1 with sound communication channels to both the staff and families. The Board was also very involved and supportive… The focus on agency and children’s choices required every room to rethink how they involved children in the program and routines. For many it was confronting but the educational leader and room leaders were committed to making the changes and the process was a collaborative team effort” (CD, CS14).

Discussion

The Australian NQF builds on a lengthy history and commitment to systemic approaches to regulation and quality improvement in ECEC. Using the OECD Quality Beyond Regulations (2022) review as a current point of reference we have suggested the NQF provides an example of contemporary regulation and quality assurance in ECEC. From a systems perspective, the explicit aim of the NQF is to “raise quality and drive continuous improvement and consistency in children’s education and care services” (ACECQA, 2023, 8) across Australia. Aligning to the OECD recommendations, the NQF covers all education and care services, targets key determinants of quality based on current evidence (Siraj et al., 2019; Thorpe et al., 2022), strengthens the focus on process quality, promotes self reflection and evaluation, and enables the standards to be met in different ways promoting educator agency and professional practice (Irvine and Price, 2014; Jackson, 2015).

Our research interest was the translation of policy into practice. Using multiple case study methodology (Stake, 2006), we explored the lived experience of Assessment and Rating, focusing on the factors that enabled and challenged meaningful engagement, sustained quality improvement and an improved quality rating. The concept of meaningful engagement is important here. Based on the study findings, meaningful engagement in A&R is characterised by leadership that: facilitates the authentic involvement of all team members; enables individual and collective voice and agency in decision-making, supports an inclusive learning community, and promotes shared leadership, responsibility and accountability for quality improvement. Importantly, while recognizing the critical leadership role of the approved provider and positional leaders within the service, meaningful engagement is reliant on collaborative leadership and teamwork, inclusive of children, families and the Regulatory Authority (Douglass, 2019).

The study findings show that meaningful engagement in the A&R process informed priorities for ongoing learning and acted as a catalyst for continuous quality improvement, consistent with stated policy expectations (Siraj et al., 2019). The dominant focus was process quality, in particular, building individual and collective capacity to enhance teaching and learning. Interestingly, there was also evidence that engagement with A&R provided a platform for team building and effective teamwork. Recognizing the association between educator stress and engagement in Quality Rating and Improvement Systems, this was an unexpected finding. Reflective of previous studies (Grant et al., 2018), educators in our study talked about the stress of external observation and assessment, and expressed some anxiety about preparation and documentation. However, our analysis revealed a range of strategies employed by services to build educator knowledge and confidence, reducing stress and anxiety and strengthening engagement over time.

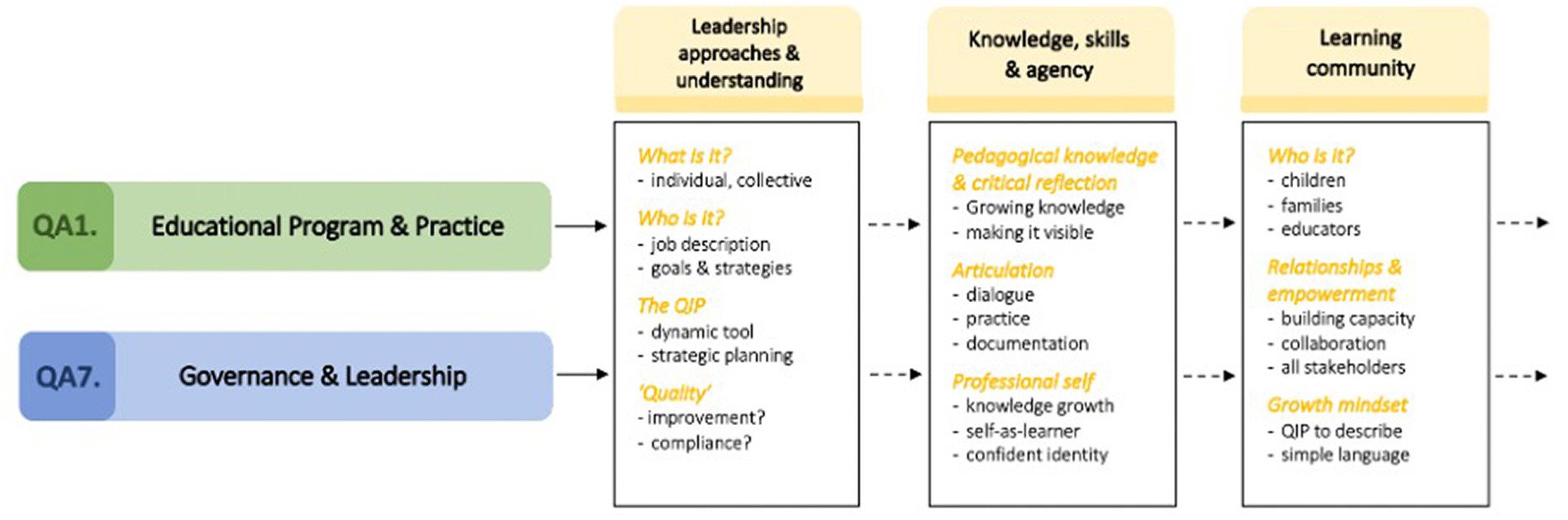

We embarked on analysing the findings of this study to better understand how to get the most out of the NQS Assessment and Ratings process at the grassroots level, in order to achieve sustained quality improvement in ECEC settings in Australia. While acknowledging different ways of working, the study highlights three critical enablers of meaningful engagement demonstrated by providers and practitioners and associated with genuine and sustained quality improvement and an improved quality rating. These are:

i. Leadership understandings and approaches

ii. Knowledge, skills and agency

iii. Learning communities

Combining these three elements, we offer a model to foster stakeholder participation in quality assurance matters within ECEC services through affordances of meaningful engagement (see Figure 2). Our model serves as a representation of the aspects in QA 1 and 7 that assisted services to improve their rating and successfully engage staff in the A&R processes. Each of the enablers are discussed in turn, with reference to extant literature as appropriate. Recognizing the critical role of leadership in driving and enabling quality improvement (Waniganayake et al., 2023), we begin with leadership understandings and approaches.

Leadership understandings and approaches

In this study, the way that leadership was understood and enacted at different levels across the roles of the approved provider, centre director, educational leader and educators built a context that empowered all individuals to lead in some way and was critical to driving quality improvement. With the exception of a few, the majority of educators, believed they had a role to play in leading quality practices and that leading was both a collective and an individual activity. The approved providers in these services held the view that to improve quality, positional leadership roles were important and needed to be well defined and receive investment of both time and resources. Sebastian et al. (2016) found that organizational leaders played a key role in flattening power structures to a more distributive leadership approach and fostering leadership in others. Kangas et al. (2015) and Eskelinen and Hujala (2015) in Finland describe how administrators can influence the development of leadership in a service, as they set the organizational conditions that enable or constrain leadership across the staff team. In this study, leaders knew their roles and responsibilities and were able to filter top-down policies such as the implementation of the NQS in ways that made them non-threatening to others as shown in taking a team learning approach to the A&R visit. Campbell-Barr and Leeson (2016) suggests that an active egalitarian style of leadership promotes a positive workplace environment that enables the successful contextualization and implementation of top-down policies.

Leaders were strategic in thinking through and co-developing goals and strategies for improving practice using the NQS. The QIP became a living, dynamic document with input from all stakeholders: approved providers, children, families, centre staff and other professionals, including the Regulatory Authority through the A&R report. Leaders in these services built an understanding that optimizing outcomes through quality improvement for children was a shared responsibility and everyone was accountable to each other for the realization of this. Sims et al. (2018) found that many educational leaders concentrated on compliance, yet in contrast in this study, leaders worked hard to instil an understanding of the NQS and Assessment and Rating process as a tool of continuous quality improvement, not as compliance.

An aspect of this leadership approach was a strong shared focus on building all educator’s deep knowledge and understanding of the national Approved Learning Framework as the foundation for curriculum and pedagogy. This is discussed next.

Knowledge, skills and agency

For meaningful engagement to occur, a strong shared focus on building deep knowledge and understanding of the national Approved Learning Framework as the foundation for curriculum and pedagogy was key. It was shown that educational leaders required a strong foundational knowledge of early childhood curriculum and pedagogy as outlined in the Early Years Learning Framework (DEEWR, 2009). They were also required to be articulate and knowledgeable about learning processes so they could lead the learning of others. This was also found by Moyles et al. (2002) in the Study of Pedagogical Effectiveness in Early Learning (SPEEL) where effective early childhood leaders were those who were able to combine specialist knowledge and professional capabilities with centre philosophy and reflective dispositions. Additionally, the educational leaders saw themselves as leaders of teaching and learning across staff teams and who sought new ideas and ways of working by engaging with theory and research. Effective pedagogical leadership assists in “forming a bridge between research and practice through dissemination of knowledge and shaping agendas (Siraj and Hallet, 2014, 112).

The educational leaders in this study were able to articulate professional practice in ways that others with varied backgrounds and qualifications could understand. This is not an easy task. As Sims et al. (2018) observe, educational leaders need to interpret legislation, policy and curriculum documents before they can model and support educators in their centre. Educators spoke of a different understanding of their professional self, as well as themselves as learners who grew when pedagogical knowledge was shared through dialog, and reflective practices became embedded in their daily work (see Douglass, 2019). Critical reflective practice was important for not only changing practices but also assisted with educator’s confidence and ability to articulate and make visible in their planning and documenting of the what, why and how of their work in relation to the NQS. A key aspect of an educational leader’s work was monitoring pedagogical and planning documentation, but this was embedded in a discourse of relationships which was also found by Sims et al. (2018). Educational leaders knew that to be successful ownership was necessary and some sense of power in changing processes or leading practices for change. Staff agency and trust brought about engagement in learning and professional development, and strategies to support change and sustain improved practice (Douglass, 2019).

Finally, the case studies promote the need for, and shared benefits of, cultivating a learning community within the centre, inclusive of all members of the community (e.g., educators, children, families, all staff and the approved provider).

Learning communities

In the settings in this study that improved ratings, leaders and educators had built a learning community that involved educators, children, families, community members and other professionals. It was seen there was a role for the approved provider and centre director in creating and maintaining a work culture that enabled a learning community where relational trust was built and time and resources were given. Inviting and facilitating child and family input into quality improvement aligns with the objectives of the NQF and has been identified as key to strengthening process quality and improved ECEC internationally (Edwards, 2021). Leaders in this study were shown to build learning communities by empowering others, boosting morale and enthusiasm and supporting effective structures to evaluate practice for improvement. By thinking of the setting as a learning community, educators in this study were invited to contribute to the development of the QIP and A&R report which served to bring the team together. The structures put in place by leaders and staff teams are important aspects in terms of building confidence about quality improvement practices, professional learning and collaboration fostered with specific goals for improvement (Douglass, 2019). Eadie et al. (2021, 69) found that quality improvement occurred when there was a ‘whole-of-service’ approach to quality improvement that assisted in strengthening educator knowledge and skills.

Attention to relational elements in building learning communities that empowered educators was important in this study and also found in other studies (see Sims et al., 2018). Indeed, the Guide to the National Quality Framework (ACECQA, 2023, 308) in Quality Area 7.2 the text describes effective leadership that “builds and promotes a positive organizational culture and professional learning community”. Many services in the case studies exercised leadership that reflected this definition as they took a community learning approach to the A&R process that built collegiality and capacity of all stakeholders. To improve quality Douglass (2019) reports that collegial relationships and providing a range of supports for staff such as professional development and mentoring programs are a strategy that may be used to increase the capacity of staff. The A&R process was not seen by educators as a big stick or one-off performance but rather an ongoing learning opportunity supported by mentoring, coaching, professional learning and the building of reflective practices. Through mentoring and coaching, feedback was regularly given to educators that was timely, relevant and explained how educators could improve in line with effective feedback practices (Keiler et al., 2020). Leaders in services built the growth mindsets (Dweck, 2016) of educators who were open to setting goals in learning and where the trying out new practices, making mistakes and adjusting were all seen as part of the learning process. The QIP was an open and shared strategic planning document. It was simply written, and educators used it and understood their part in it and were encouraged to give feedback for improvement.

While we have focussed on the centre community here, we draw attention to the role of the Regulatory Authority in enabling the meaningful engagement of all stakeholders in quality improvement. The study findings highlight the influence of the leadership approach of the assessor in building shared understanding of the NQS and A&R process, asking the right questions and helping educators to feel comfortable and able to articulate their practice. The assessor’s knowledge and skill in undertaking the assessment (Moloney, 2016) and developing the A&R report is also critical here, recognizing the contribution of an informed and well-written report to centre learning communities.

Conclusion

This study showed that meaningful engagement in the A&R process of the NQS provides a platform for genuine and sustained quality improvement. Meaningful engagement requires leadership at all levels and approaches that build an understanding that leadership is both an individual and collective activity. It also involves leaders with strong pedagogical knowledge as well as knowledge of how to lead others’ learning. Critical reflection and articulation of practice assist educators to grow as educators and learners as well as developing a confident professional identity. The building of a learning community was key to sustained quality improvement where all stakeholders were involved, and relationships were fostered in empowering ways. Further, learning communities were developed where educators were open to change, feedback and as a result growth mindsets were developed.

Meaningful engagement is dependent on the efficacy of the broader regulation and quality assurance system, specifically, quality standards and expectations that reflect current research and practice wisdom, strengthen the focus on process quality, enable educator agency and engage all stakeholders in the quest for continuous quality improvement. This includes commitment and investment from the Regulatory Authority to drive continuous quality improvement in the system, working in genuine collaboration with those involved in providing and using these services.

Situated within a national Quality Improvement Research Project, we acknowledge limitations to the study findings. The study scope was limited to quality improvement in 15 long day care services, undertaken at a point in time, and situated within the Australian ECEC policy context. While we hypothesize similar enablers and challenges to quality improvement in other Australian ECEC settings, based on NQS snapshot data (ACECQA, 2022a), our findings cannot be generalized to other settings or countries. We also recognize that quality improvement is both contextual and temporal; what works in one service may not work in another and within one service different approaches and strategies may be needed at different times. Acknowledging these limitations, the study findings provide unique insights into the contribution of a contemporary Quality Rating and Improvement System to sustained quality improvement, informed by the lived experience of providers and professionals engaging with the system. Our model offers research- based guidance to support the meaningful engagement of all stakeholders in quality assurance matters, for consideration by both practitioners and policy makers.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Macquarie University Human Ethics Research Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

SI and LB were lead authors of the paper. All authors were part of the National Quality Improvement Project, led by LH. SI, LB, MW, FH, RA, MH, LH, and BD collected the data in the Phase 3 case studies. SI, LB, MW, FH, RA, MH, LH, BD, and HL were involved in the analysis of this data. LL was the senior research assistant for this study. All authors contributed to this paper.

Funding

The overarching National Quality Improvement Project was funded by the Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

ACECQA. (2022b). NQF snapshot. Q2 2022. A quarterly report from the Australian Children’s education and care quality authority. ACECQA: Sydney.

AGDE (2022). Belonging, being and becoming: The early years learning framework for Australia (V2.0), Canberra, Australia: Australian Government Department of Education for the Ministerial Council.

Bourke, T., Ryan, M., and Ould, P. (2018). How do teacher educators use professional standards in their practice. Teach. Teach. Educ. 75, 83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2018.06.005

Campbell-Barr, V., and Leeson, C.. (2016). Quality and leadership in the early years: research, theory and practice. London, UK: SAGE Publications.

Creswell, J. W, and Creswell, J. D.. (2018). Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. (5th Edn.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Davis, B., Dunn, R., Harrison, L. J., Waniganayake, M., Hadley, F., Andrews, R., et al. (2023). Mapping the leap: differences in quality improvement in relation to assessment rating outcomes. Front. Educ. 8, 1–23. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1155786

Douglass, A. (2019). “Leadership for quality early childhood education and care” in OECD education working papers, vol. 211 (Paris: OECD Publishing)

Dweck, C. S. (2016). Mindset: the new psychology of success (Updated Edn.). New York, NY: Penguin Random House.

Eadie, P., Page, J., and Murray, L. (2021). “Continuous improvement in early childhood pedagogical practice: the Victorian advancing early learning (VAEL) study” in Quality improvement in early childhood education. eds. S. Garvis and H. L. Taguchi (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 69–91.

Ebbeck, M., and Waniganayake, M.. (2003). Early childhood professionals: Leading today and tomorrow. Sydney: Mac Lennan and Petty.

Edwards, S. (2021). “Process quality, curriculum and pedagogy in early childhood education and care” in OECD education working papers, vol. 247 (Paris: OECD Publishing)

Eskelinen, M., and Hujala, E. (2015). “Early childhood leadership in Finland in light of recent research” in Thinking and learning about leadership: Early childhood research from Australia, Finland and Norway. eds. M. Waniganayake, J. Rodd, and L. Gibbs (Sydney: Community Child Care Cooperative NSW), 87–101.

Fenech, M., Sumsion, J., and Goodfellow, J. (2006). Regulation and risk: early childhood education and care services as sites where the ‘laugh of Foucault’ resounds. J. Educ. Policy 23, 35–48. doi: 10.1080/02680930701754039

Goffin, S. (2015). Professionalizing early childhood education as a field of practice: A guide to the next era. St. Paul, MN: Redleaf Press.

Grant, S., Comber, B., Danby, S., Theobald, M., and Thorpe, K. (2018). The quality agenda: governance and regulation of preschool teachers’ work. Camb. J. Educ. 48, 515–532. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2017.1364699

Harrison, L. J., Andrews, R., Hadley, F., Irvine, S., Waniganayake, M., Barblett, L., et al. (2023). “Protocol for a mixed-methods investigation of the structures and processes that support quality improvement in early childhood education and care in Australia” in Child and youth services review, vol. 155, 107278.

Harrison, L.J., Hadley, F., Irvine, S., Davis, B., Barblett, L., Hatzigianni, M., et al., (2019). Quality improvement research project. Commissioned by the Australian Children’s education and care quality authority. Olney: Routledge Available at: https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-05/qualityimprovement-research-project-2019.PDF

Harrison, L. J., Waniganayake, M., Brown, J., Andrews, R., Li, H., Hadley, F., et al. (2023). Structures and systems influencing quality improvement in Australian early childhood education and care services. Aust. Educ. Res., 1–23. doi: 10.1007/s13384-022-00602-8

Harrison, L. J., Wong, S., Press, F., Gibson, M., and Ryan, S. (2019). Understanding the work of Australian early childhood educators using time-use diary methodology. J. Res. Child. Educ. 33, 521–537. doi: 10.1080/02568543.2019.1644404

Hatzigianni, M., Stephenson, T., Harrison, L. J., Waniganayake, M., Li, H., Barblett, L., et al. (2023). The role of digital technologies in supporting quality improvement in Australian early childhood education and care settings. Int. J. Child Care Educ. Policy 17:5. doi: 10.1186/s40723-023-00107-6

Hotz, V. J., and Wiswall, M. (2019). Child care and child care policy: existing policies, their effects, and reforms. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 686, 310–338. doi: 10.1177/0002716219884078UNICEF

Irvine, S., and Price, J. (2014). Professional conversations: a collaborative approach to support policy implementation, professional learning and practice change in ECEC. Australas. J. Early Childhood 39, 85–93. doi: 10.1177/183693911403900311

Jackson, J. (2015). Constructs of quality in early childhood education and care: a close examination of the NQS assessment and rating instrument. Australas. J. Early Childhood 40, 46–50. doi: 10.1177/183693911504000307

Kangas, J., Venninen, T., and Ojala, M. (2015). Distributed leadership as administrative practice in Finnish early childhood education and care. Educ. Manag. Admin. Lead. 44, 617–631. doi: 10.1177/1741143214559226

Keiler, L. S., Diotti, R., Hudon, K., and Ransom, J. C. (2020). The role of feedback in teacher mentoring: how coaches, peers, and students affect teacher change. Mentor. Tutor. 28, 126–155. doi: 10.1080/13611267.2020.1749345

McLaughlin, M. W. (1991). “Learning from experience: lessons from policy implementation” in Education policy implementation. ed. A. R. Odden (New York: State University of New York Press), 185–196.

Melhuish, E., and Gardiner, J. (2019). Structural factors and policy change as related to the quality of early childhood education and care for 3 – 4 year olds in the UK. Front. Educ. 4. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00035

Moloney, M. (2016). Childcare regulations: regulatory enforcement in Ireland. What happens when the inspector calls. J. Early Child. Res. 14, 84–97. doi: 10.1177/1476718X14536717

Moyles, J., Adams, S., and Musgrove, A. (2002). Early years practitioners’ understanding of pedagogical effectiveness: defining and managing effective pedagogy. Int. J. Prim. Element. Early Years Educ. 30, 9–18. doi: 10.1080/03004270285200291

OECD. (2018). Building a high-quality early childhood education and care workforce: further results from the starting strong survey 2018, TALIS, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD. (2022). Quality assurance and improvement in the early education and care sector, OECD education policy perspectives. Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Available at: https://www.oecdilibrary.org/docserver/774688bfen.pdf?expires=1681103731&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=57D8145CD8F0B1016C523A3A6424EAAF

Pianta, R., Downer, J., and Budget, H. (2016). Quality in early education classrooms: definitions, gaps, and systems. Futur. Child. 26, 119–137. doi: 10.1353/foc.2016.0015

Sebastian, J., Allensworth, E., and Huang, H. (2016). The role of teacher leadership in how principals influence classroom instruction and student learning. Am. J. Educ. 123, 69–108. doi: 10.1086/688169

Sims, M., and Hui, S. K. F. (2017). Neoliberalism and early childhood. Cogent Educ. 4: 1–10. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2017.1365411

Sims, M., and Waniganayake, M. (2015). The performance of compliance in early childhood: neoliberalism and nice ladies. Glob. Stud. Early Childhood 5, 333–345. doi: 10.1177/2043610615597154

Sims, M., Waniganayake, M., and Hadley, F. (2018). Educational leadership: an evolving role in Australian early childhood settings. Educ. Manag. Admin. Leader. 46, 960–979. doi: 10.1177/1741143217714254

Siraj, I., and Hallet, E.. (2014). Effective and caring leadership in the early years. London: SAGE Publications Inc.

Siraj, I., Howard, S. J., Kingston, D., Neilsen-Hewett, C., Melhuish, E. C., and de Rosnay, M. (2019). Comparing regulatory and non-regulatory indices of early childhood education and care (ECEC) quality in the Australian early childhood sector. Aust. Educ. Res. 46, 365–383. doi: 10.1007/s13384-019-00325-3

Slot, P. (2018). “OECD education working paper no. 176” in Structural characteristics and process quality in early childhood education and care: a literature review (OECD). New York: Elsevier Inc.

Slot, P. L., Leseman, P. P., Verhagen, J., and Mulder, H. (2015). Associations between structural quality aspects and process quality in Dutch early childhood education and care settings. Early Child. Res. Q. 33, 64–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.06.001

Tayler, C. (2011). Changing policy, changing culture: steps toward early learning quality improvement in Australia. Int. J. Early Childhood 43, 211–225. doi: 10.1007/s13158-011-0043-9

Tayler, C., Ishimine, K., Cloney, D., Cleveland, G., and Thorpe, K. (2013). The quality of early childhood education and Care Services in Australia. Australas. J. Early Childhood 38, 13–21. doi: 10.1177/183693911303800203

Thorpe, K., Houen, S., Rankin, P., Pattinson, C., and Statton, S. (2022). Do the numbers add up? Questioning measurement that places Australian ECEC teaching as ‘low quality. Austr. Educ. Res. 50, 781–800. doi: 10.1007/s13384-022-00525-4

UNICEF. (2019). A world ready to learn: prioritizing quality early childhood education. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/turkiye/media/7071/file/A%20World%20Ready%20To%20Learn%20-%20Global%20Report%202019.pdf

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: the development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wangmann, J. (1995). Towards integration and quality Assurance in Children’s services. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Keywords: quality improvement, early childhood education and care, assessment and rating, meaningful engagement, long day care

Citation: Irvine SL, Barblett L, Waniganayake M, Hadley F, Andrews R, Hatzigianni M, Li H, Lavina L, Harrison LJ and Davis B (2024) The quest for continuous quality improvement in Australian long day care services: getting the most out of the Assessment and Rating process. Front. Educ. 9:1207059. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1207059

Edited by:

Douglas F. Kauffman, Medical University of the Americas – Nevis, United StatesReviewed by:

Louise Tracey, University of York, United KingdomEliana Bhering, Fundação Carlos Chagas, Brazil

Copyright © 2024 Irvine, Barblett, Waniganayake, Hadley, Andrews, Hatzigianni, Li, Lavina, Harrison and Davis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Susan Lee Irvine, cy5pcnZpbmVAcXV0LmVkdS5hdQ==

Susan Lee Irvine

Susan Lee Irvine Lennie Barblett

Lennie Barblett Manjula Waniganayake

Manjula Waniganayake Fay Hadley

Fay Hadley Rebecca Andrews

Rebecca Andrews Maria Hatzigianni

Maria Hatzigianni Hui Li

Hui Li Leanne Lavina

Leanne Lavina Linda J. Harrison

Linda J. Harrison Belinda Davis

Belinda Davis