- Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

This study reports on the synergistic liaison between student wellbeing and academic support in higher education. The study took place at a large, urban university in South Africa within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Brief interviews were conducted between September and November 2021, with undergraduate students (n = 645, Mage = 22; SD = 2) from a variety of scientific fields. The guiding question for the brief interviews was, ‘What contributes to your wellbeing at the university?’ Responses were captured in statu nascendi (as it develops) by fieldworkers from the helping professions and then transferred to a comprehensive Electronic Data Sheet. The raw verbal response data were analyzed using an open coding process where major and minor themes were initially indicated. A theme emerged around the intricacies of academic support and intrapersonal processes that are central to the wellbeing of students in higher education. Academic support was apparent in the provisioning of resources for learning, quality communication from lecturers, peer-to-peer support, and collective positive student experiences. Beyond these external resources, intrapersonal factors including a focus on the self, a sense of responsibility, and ensuring mental balance, while sustaining a sense of accomplishment academically, emerged as critical to student wellbeing. Efforts to continually improve student experience are still paramount within the higher education space, and this can be accompanied by psychosocial interventions aimed at promoting a strong sense of positive selfhood. These interventions could be designed to promote internal resources that allow students to capitalize on institutional provisioning in the achievement of academic goals and wellbeing.

1 Introduction

Even though much credence has been given to the importance of student wellbeing in higher education in recent years (Albright et al., 2022; Eloff and Graham, 2020; Graham and Eloff, 2022; Wade et al., 2015), indications are that 43% of students internationally who enter university or college education do not complete their undergraduate degree in 6 years (Schreiner, 2015). According to The Open University in the UK, among 29 countries sampled in 2015, the UK has the lowest dropout rate at 19%, than Germany (28%), Australia (35%), and the USA (37%). Comparatively, in 2005 in South Africa, the Department of Education reported that of the 120,000 students who enrolled in higher education in 2000, 36,000 (30%) dropped out in their first year of study. A further 24,000 (20%) dropped out during their second and third years. Of the remaining 60,000, 22% graduated within the specified 3-year duration for a generic bachelor’s degree (Moeketsi and Maile, 2008). This trend persists in other low-income countries despite various attempts, strategies, and additional techniques aimed at addressing and enhancing student retention and success (Thomas and Hanson 2014). This dilemma can be attributed to various factors, including inadequate preparation for higher education, lack of commitment among students, unsatisfactory academic experiences, ineffective matching between students and courses by institutions, insufficient social integration, financial difficulties, and personal circumstances (Sondlo, 2019). A study by Millea et al. (2018) found higher graduation rates for students who were in smaller classes, who were grant or scholarship recipients, and who were academically prepared for university studies. These findings seem to suggest that universities should invest in smaller class sizes, optimize student financial aid infrastructure, broaden access to scholarships, and facilitate pre-university preparation programs. Perspectives from academic staff in the USA suggest that students could benefit from a holistic support system that integrates both student-centered and course-centered approaches, in collaboration with centrally located university counselors (Crawford and Johns, 2018). Many other studies, however, have also flagged variance in terms of student success and its relation to socioeconomic and racial background variables in student populations (Banks and Dohy, 2019; Gershenfeld et al., 2016), thereby suggesting even more intricate dynamics between the environments within which students pursue tertiary studies and their personal, subjective wellbeing. The broader objective of the current study was therefore to investigate the coalescence of student wellbeing, the underpinning intrapersonal processes, and academic support in higher education.

When considering concerns about high dropout rates and extended degree completion times among undergraduate students in relation to wellbeing, it is essential to closely examine the granular aspects of academic support at the disposal of the students. Louis (2015, p. 99) has pointed out that an inherent purpose within the convergence of higher education and positive psychology (i.e., wellbeing studies) is in fact “discovering how best to promote student success and growth during the college years and beyond.”

In this study, wellbeing is conceptualized as the experience of positive emotions, the absence of negative affect, a satisfactory evaluation of life (hedonia), and psychological functioning (eudaimonia). In terms of psychological functioning, student wellbeing encompasses experiencing competency, efficacy, and academic achievement. The hedonic and eudaimonic consideration of wellbeing is grounded in a number of frameworks, but the most relevant is Keyes’ (2002) mental health continuum. To foster these indicators of wellbeing for students, the nature of the academic environment is critical. In a diary study by Robayo-Tamayo et al. (2020) on the mediating role of academic resources in the relationship between personal resources (internalized or intrapersonal processes) and variables of wellbeing, a positive relationship between academic support and academic engagement was found. In addition, Robayo-Tamayo et al. (2020) found a positive relationship between self-efficacy, levels of curiosity, and academic engagement among undergraduate students. In the context of the pandemic, Liu et al. (2021) highlighted that among a large sample of Australian students, student wellbeing, which is influenced by factors such as physical health, emotional support, relationships, resilience, counseling, and course-based support, should be considered critical interventions going forward.

As a rationale for the study, if we acknowledge the intricate dynamics between student wellbeing and the environments within which tertiary education students study, the specific nature of academic support needs further exploration and explication. In addition, it is important to understand the role of the individual in this process, including the intrapersonal and intrapersonal dynamics that may contribute to wellbeing. This understanding is vital because such evidence will serve as recommendations for psychological interventions and changes within South African education institutions, aimed at enhancing student experience and reducing dropout rates.

The focus of the current study was to investigate the ways in which academic support and intrapersonal processes contribute to wellbeing in higher education during a critical life transition from late adolescence into early adulthood. The study also aimed to contribute to knowledge development at the intersection of wellbeing research and academic support in a South African context.

The current brief report asked the following primary research question: “What is the nature of intrapersonal processes and academic support for student wellbeing in higher education?”

2 Method

The study was conducted at a research-intensive university in a large metropole in the Gauteng Province of South Africa. During the year of the study, the university was home to 37,820 undergraduate and 16,278 postgraduate students who study on multiple campuses (Mallick, 2022) in nine faculties. The majority (58%) of the total undergraduate student population is female, 41% are male, and 1% are undisclosed. The language of instruction is English. Academic support is provided by 24 faculty student advisors (FSAs), 16 peer advisors, and between 500 and 600 student tutors who are appointed annually on a part-time basis. The university initiated a data-driven approach to student wellbeing in 2017 and has since been collecting student wellbeing data annually via a mixed-methods approach. Data collection strategies include brief interviews, online surveys, and focus groups. Permission to conduct the study was received from the University of Pretoria, Faculty of Humanities Ethics Committee under the ethics number HUM0180232HS.

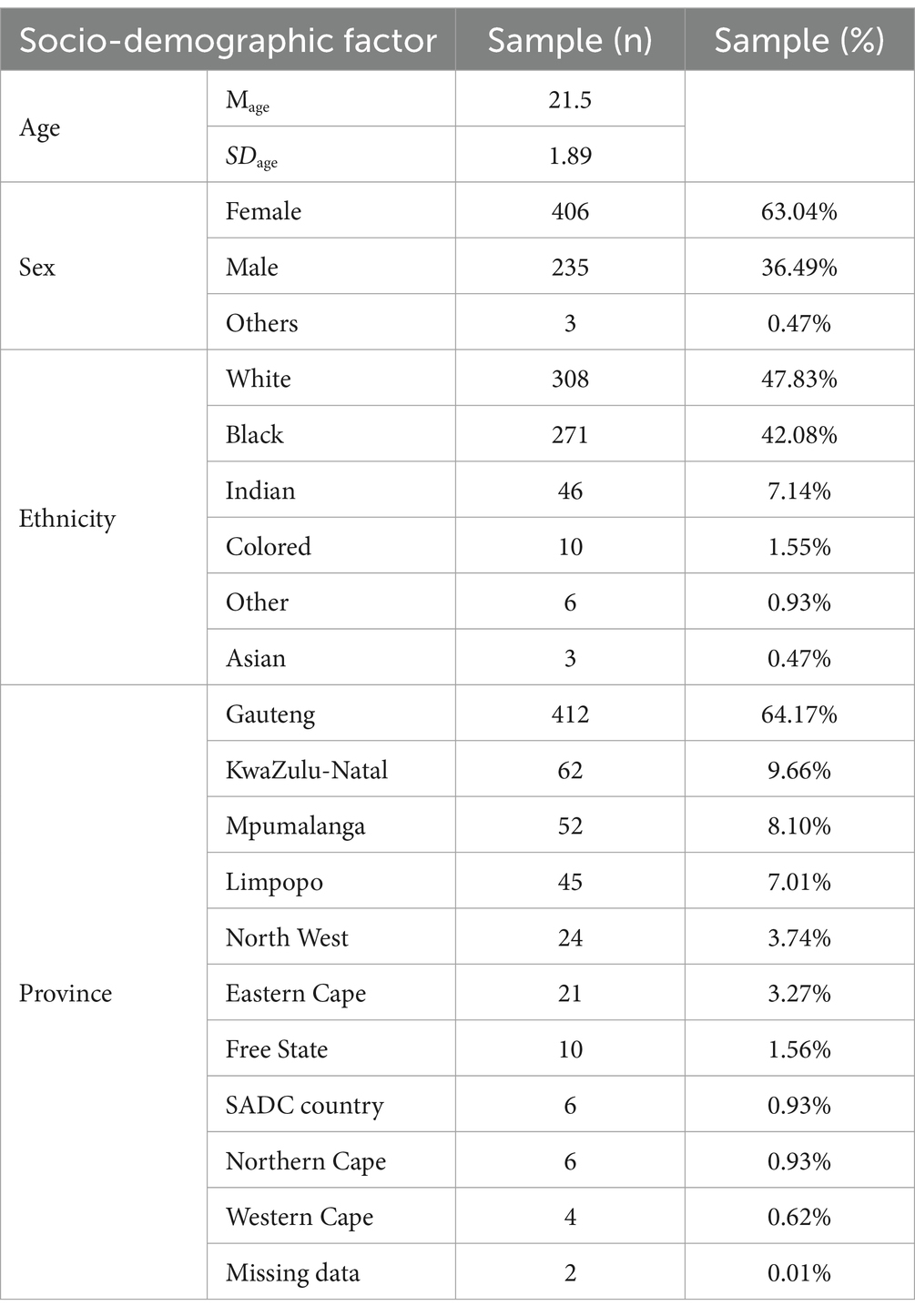

The current study reports on the brief interview data that were collected from undergraduate students in the second semester of the academic year (September–November 2021) in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. A team of postgraduate students (n = 39) in the helping professions were trained as fieldworkers. Fieldworker training included practical fieldwork skills, a short theoretical overview of wellbeing research, and ethics in research. Participants were randomly recruited by fieldworkers approaching students in person on campus during the week (Monday–Friday), between 07:30 and 17:00 over a period of 8 weeks. The undergraduate status of the students was confirmed, and they were provided with a short background of the study and asked whether they would be interested in participating in a brief interview. In some instances, fieldworkers were provided with contact details of other students who may also have been interested in participation. Subsequently, the brief interviews were conducted either in person or online with undergraduate students from all the faculties at the university. During the brief interviews, participants (n = 645, M age = 22; SD = 2) completed biographical details (see Table 1) and then answered one question, i.e., ‘What contributes to your wellbeing at the university?’. Responses were captured in statu nascendi by the fieldworkers and collated in a collective electronic dataset.

Thematic analysis as outlined by Braun and Clarke (2013) was followed in making sense of the data and determining emerging themes and patterns. Given that the data comprised short answers from a large number of participants, inductive thematic analysis was followed to extract core themes related to the research questions of personal and institutional factors contributing to student wellbeing. For each participant response, we coded the data that pointed to factors responsible for wellbeing. In the next step of the analysis, we determined the extent to which each code was relevant to the individual or institution. As a way of thematizing, we further looked out for patterns in the existing categories that spoke to the nature of support for wellbeing and presented these as themes in the Results section. Verbatim responses from participants have been added to each theme accompanied by researcher-assigned participant number, age, and gender.

3 Findings

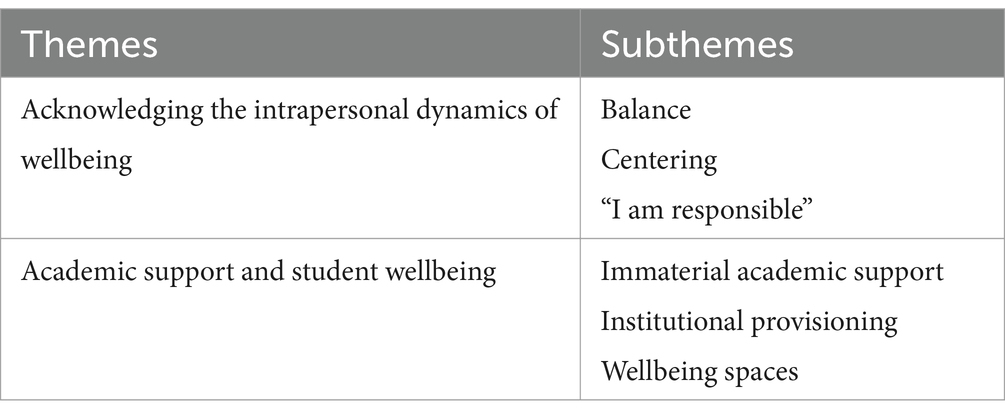

In this section, we highlight not only the key findings emerging from our study including the intrapersonal but also the external support mechanisms that drive student wellbeing in this sample of South African students (see Table 2).

3.1 Acknowledging the intrapersonal dynamics of wellbeing

In our endeavor to comprehend the factors contributing to student wellbeing, we examined both internal psychological processes and external institutional dynamics, which appear to complement each other in fostering student wellbeing. Among these intrapersonal processes were “balance,” “centering” and “ownership/responsibility for wellbeing.”

3.1.1 Balance

Many students attributed their wellbeing to achieving balance, which involved recognizing the significance of self-care while dedicating the required effort to attain academic goals. Participants noted the importance of taking breaks and knowing when it is time to pay attention to school work and when it is time for pleasurable activities.

I'd say taking breaks when I need to. Doing something that gets me out [SIC] the house then coming back and working. Getting inspiration and motivation online. (P 596, 21-year-old, female).

Related to this theme was the importance of time management and having a well-balanced lifestyle. Participants’ reports showed that they valued their academic pursuits and were well motivated to invest the necessary efforts to achieve their goals while making sure that they were functioning well in other domains of life.

Uhm, okay I think having a balanced lifestyle with sport and family combining it with studies to keep it balanced (P 445, 21-year-old, male).

Beyond time management in terms of juggling between work and pleasure, participants also referred to the need for mental balance.

Ability to focus on studies. It is the balance of physical, mental, emotional, and financial wellness/health (P 530, 19-year-old, female).

Balance is also important. I try to find a way to balance all areas in my life, especially my mental health […] (P 599, 20-year-old, female).

The extracts referred to above point to the need to experience psychological stability in order to function well. Mental balance seems to draw on the inner harmony and calmness that is experienced by the individual (Delle Fave et al., 2023). It also points to the intertwined nature of physical, emotional, and material aspects of life and how each contributes to experiencing that state of inner requiem, tranquility, and stability (Wissing et al., 2019).

3.1.2 Centering

The theme of centering puts the individual at the heart of wellbeing experiences and recognizes the need to continuously reflect “on the person” in an attempt to promote wellbeing. Through centering, some participants rediscovered themselves and were able to assertively decide on who or what they desired to become.

Being responsible, ability to discover myself, […] (P 20, 21-year-old female).

Time away from things, free time to focus on oneself, manageable stress […]. that’s make my wellbeing complete [SIC]. (P 22, 21-year-old, female).

Students in this study felt that it was important to find themselves and discover who they are beyond academics. Centering allowed them to look beyond the university context for activities that contribute to their sense of selfhood and identity, encouraging them to invest time in these pursuits.

I try to find things outside of university life that I am good at to find my self-worth in something other than just what I study. This is very important to do things that you are good at and makes you happy like petting my dogs and going for walks with them, hiking, and things like that. (P 218, 22-year-old, male).

3.1.3 I am responsible

In this theme, we emphasize how students assume responsibility for their wellbeing by managing both their mental and academic environments. For instance, Participant 192 indicated that she was responsible for maintaining a positive mindset despite the external demands she had to manage. Furthermore, there was an emphasis on personal organization which in a sense allowed for feelings of control and even mastery (Ryff, 2014; Wilson Fadiji et al., 2022).

Being a student can be stressful, what adds to that is the current circumstances of online learning, it makes keeping a positive mindset impossible at times. However, ways that contribute to my wellbeing is prioritizing and organising my weekly tasks on a calendar to ensure that I stay on top of work and meet my deadlines. This helps to minimize my stress. I allow myself to take small breaks in between my studies. This includes going outdoors and exercising as it helps to clear my mind and allow me to breathe in the fresh air. Lastly, I try to keep a positive mindset and stay motivated no matter what. I try not to let failure knock me down, instead I learn from it and use it as motivation to continue trying until I succeed. [SIC] (P 192, 20-year-old, female).

Being able to decide what needed the most attention at different points in time ensured that students were not overwhelmed or felt helpless. Even in situations where things do not turn out as expected, a positive mindset and sense of control allowed students to still thrive as they found alternative solutions for the challenges they encountered.

3.2 Academic support and student wellbeing

We also investigated how the institutional environment might contribute to student wellbeing. These include intangible support, social interactions, and the university physical spaces that emerged as playing a role in student wellbeing.

3.2.1 Immaterial academic support

This form of academic support encompasses the nature of relational and social interactions occurring between students and the university. This includes interactions with lecturers, administrators, tutors, and faculty advisors. For instance, participants in our study did indicate that they appreciated it when lecturers communicated frequently, were understanding, and gave tasks that were manageable.

The lecturers being helpful and doing their part. Things being organised and knowing what is expected of me. Open communication between the lecturers and the student has really helped. The support and motivation I get. … So I think that if the lecturers were supportive and more organised it would help us be organized and understand what we are doing and help us feel less stress. I also think it’s important for our wellbeing if we can communicate with the lecturers and they can communicate with us to always know what is expected and then some lecturers will send emails of clickUP1 messages saying good luck and I really appreciate that. (P 595, 22-year-old, female).

3.2.2 Institutional provisioning

Institutional provisioning encompasses all types of material support provided by the university, which was identified as crucial for wellbeing. This includes having tutors, faculty advisors, counselors, and psychologists available to provide support. This was particularly important because of the alienation brought on by the pandemic as well as all the changes that students needed to cope with.

With the COVID-19 pandemic, it was difficult to adjust to online learning as I was used to my routine of having face-to-face lectures and being on campus daily. Our lecturers managed to make the online learning experience the same as being on campus. We have consultation sessions online with lectures and tutors for any assistance that we need. This has made a big difference as it enables us to understand the content better and make sure we can ask questions and enquire about what we don’t understand. This has made an impact on my wellbeing as an online university student. (P 195, 21-year-old, female).

Students noted that the availability of lecturers and tutors made a big difference in their wellbeing experiences as they did not have to feel helpless during this period. They were able to effectively continue with their academics because of the support available. Other students made mention of the services of psychologists and counselors that contributed to their ability to feel and function well. It is noteworthy that the presence of these services and not the actual use of them was instrumental in fostering wellbeing.

They have programs that the student can make use of where psychologists, doctors, and nurses help support the wellbeing of students, although I have never made use of those programs. I know that it is there if I should need it. … The res [SIC] also has a wellbeing committee (P 198, 20-year-old, female).

It is also necessary to mention that not every student was satisfied with the nature of institutional provisions being made available. Some students indicated that there were long queues to see a psychologist, and the mental health emails did not necessarily translate into any useful help for students.

3.2.3 Wellbeing spaces

When discussing wellbeing spaces, we refer to the structural provisions made by the university to create an environment conducive to learning. These provisions include experiencing a sense of safety, having access to and being able to stay in university residences, access to the sports ground, and availability of Wi-Fi, water, and electricity. The university as a wellbeing space is one that not only caters to the academic needs of the students but also provides an internalized sense of belonging and ownership of key areas of the university required for student wellbeing. It is not just about the availability of these spaces, but rather about students feeling that such spaces are genuinely accessible to them.

As a student, I would say the provision of a safe environment for learning and academic activity constitutes my wellbeing at the University of Pretoria … In a general sense, this would mean environments free from persecution for any reason, free from environmental hazard, and free from physical harm from outside sources (see 2016/2017 protests at the Hatfield campus). Additionally, and more specifically to my work at the University, provision of appropriate safety equipment and training for the handling of hazardous materials. (P 508 23-year-old, male).

For some students, it was important to experience the university as a second home, one that supports and caters to the needs of the individual, both emotional and material. Students wanted to be valued as important stakeholders whose feelings and opinions did matter within the university space.

As a res student, one thing that also contributed to my wellbeing is my housing committee and supportive house parents. Each res event made me feel like I belong and that made me feel at home. I am an introvert so making friends isn't easy for me. […] My house parents felt more like my biological parents. They took their time to get to know me and that made me more comfortable within the residence. The house committee were [SIC] always there whenever I needed assistance […]. House events brought some sense of belonging and it also made me realize that I must take a breather in between academics (P 580, 23-year-old, female).

4 Discussion

The amplification of intrapersonal and contextual factors in the conceptualization of subjective wellbeing has been emphasized by researchers who refer to the ‘Second and Third Wave of Positive Psychology’ (Wilson Fadiji et al., 2022; Wissing et al., 2022, p. 3), in which a strong relational ontology and trends toward contextualization and interconnectedness are proposed when wellbeing is studied (Schutte et al., 2022). In doing so, harmony and harmonization between various epistemological ‘coda’ in wellbeing research is intentionally sought. In wellbeing studies in tertiary education, this trend carves out conceptual pathways in which wellbeing is understood beyond the individual level while intrapersonal factors are acknowledged increasingly.

The current study provides empirical support for a conceptualization that integrates both contextual and intrapersonal symbiotic relationships in understanding wellbeing. Students are embracing personal agency in relation to their wellbeing, positioning it in close proximity to their “academic wellbeing.” Additionally, they engage in centering activities that expand their notions of “support” beyond the immediate environment.

Students themselves have pointed out the importance of the quality of the learning environment, as well as the inherent support structures (Eloff et al., 2022), in relation to their subjective wellbeing. These learning environments can include physical campus spaces such as libraries, places for rest, access to food, and exercise facilities. The support structures may include social support, access to counseling and psychological services, and academic support. The presence of these physical and social resources must be accompanied by accessibility, a sense of ownership, and constant availability in order for wellbeing to be influenced positively.

In studying the directionality between academic support, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and goal progress in students in the US context, Sheu et al. (2022) hypothesized these factors as “mediators that channel the effects of personality and affective variables on academic wellbeing” (Sheu et al., 2022, p. 1). Their study identified “academic support as the temporal precursor of self-efficacy and outcome expectations, and self-efficacy as the antecedent of outcome expectations and goal progress” (Sheu et al., 2022, p. 1). The students in the current study imbue meaning to immaterial support within their learning environments, even as they acknowledge the available “material” support, alongside centering, balance, and taking ownership for their academic outcomes.

In a study that evaluated the sociocultural influences affecting participation and understanding of academic support services in higher education, it was found that the impact of academic support is strongly associated with the quality of the relationships between the various stakeholders, e.g., students, student leaders, and mentors (Weuffen et al., 2021). These findings suggest that while the explicit goal of academic support may be the development of academic skills, the creation of a sense of belonging and a culture of inclusivity at the university is also critical (Wilson Fadiji et al., 2023). The findings in the current study indicate a similar trend, students refer to the importance of interactions with their lecturers and tutors, the availability of wellbeing spaces, and the sense of belonging they experience in their affiliative groups where they engage at the university.

5 Conclusion

The present study aimed to explore how intrapersonal processes and academic support contribute to student wellbeing within the higher education context. A key finding from this study is the importance of placing the individual at the heart of their own wellbeing by promoting mental balance and prioritizing self-care. In this regard, the acknowledgment of the intrapersonal dynamics of wellbeing, with specific reference to balance, centering, and personal responsibility is key. Simultaneously, the importance of academic support in the form of “immaterial” support, institutional provisioning, and wellbeing spaces, should echo the appeal to students to support their own wellbeing. All of these intrapersonal dynamics function only in a higher education space with adequate institutional provisioning. Such provisions must be evidently available and accessible to all students (see also Wilson Fadiji et al., 2022). Despite the use of a short, single interview question, which is a limitation of the study, we believe that the findings are worthwhile for student wellbeing promotion. The strength of the study lies in the large sample size employed in qualitative research that provided a broad spectrum of data on the factors contributing to student wellbeing. There is room for more in-depth exploration, as the current methodology does not allow this for this level of analysis. However, this limitation is compensated for by the large sample size. We suggest that while efforts to continually improve student experience are still critical within the higher education space, this can be accompanied by psychosocial interventions aimed at promoting a strong sense of positive selfhood, which is also central to the individual’s academic functioning. In terms of support that can be provided by higher education institutions, these can include training of lecturers and other academic staff on the importance of the immaterial support they offer to students. Furthermore, students at times need to be continually reminded of the institutional provisioning that is available, and where these are non-existent, resources may be vested in them. For future research consideration, further exploration of what wellbeing means in African student samples is encouraged. Additionally, interventions designed at promoting intrapersonal wellbeing factors should be tested for their impact.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Pretoria, Faculty of Humanities. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

IE was responsible for the background and introduction. AW prepared the initial draft of the data analysis and results. IE and AW were involved in writing the discussion. All authors were involved in the conceptualisation of the manuscript, and continuously revised the manuscript until publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^This is a learning management tool and platform.

References

Albright, G., Black, L. M., Graham, C., Stowe, A., Schwiebert, L., and Lanzi, R. (2022). Trajectories of college student mental health and wellbeing during the Covid-19 pandemic. J. Adolescent Health 70:S77. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.01.063

Banks, T., and Dohy, J. (2019). Mitigating barriers to persistence: a review of efforts to improve retention and graduation rates for students of color in higher education. High. Educ. Stud. 9, 118–131. doi: 10.5539/hes.v9n1p118

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for beginners. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Crawford, N. L., and Johns, S. (2018). An academic’s role? Supporting student wellbeing in pre-university enabling programs. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 15:2. doi: 10.53761/1.15.3.2

Delle Fave, A., Wissing, M. P., and Brdar, I. (2023). Beyond polarization towards dynamic balance: harmony as the core of mental health. Front. Psychol. 14:1177657.

Eloff, I., and Graham, M. (2020). Measuring mental health and wellbeing of South African undergraduate students. Global Mental Health 7, 1–10. doi: 10.1017/gmh.2020.26

Eloff, I., O’Neil, S., and Kanengoni, H. (2022). Factors contributing to student wellbeing: student perspectives in Embracing wellbeing in diverse african contexts: research perspectives. eds. L. Schutte, T. Guse, and M. P. Wissing (Cham: Springer), 219–246.

Gershenfeld, S., Ward Hood, D., and Zhan, M. (2016). The role of first-semester GPA in predicting graduation rates of underrepresented students. J. Coll. Student Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 17, 469–488. doi: 10.1177/1521025115579251

Graham, M. A., and Eloff, I. (2022). Comparing mental health, wellbeing and flourishing in undergraduate students pre-and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:7438. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19127438

Keyes, C. L. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. J. Health Soc. Behav., 207–222.

Liu, C., McCabe, M., Dawson, A., Cyrzon, C., Shankar, S., Gerges, N., et al. (2021). Identifying predictors of university students’ wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic—a data-driven approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:6730. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18136730

Louis, M. C. (2015). “Enhancing intellectual development and academic success in college: insights and strategies from positive psychology” in Positive psychology on the college campus. eds. J. C. Wade, L. I. Marks, and R. D. Hetzel (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 99–131.

Mallick, Y. (2022). Core students statistics. Available at: https://www.up.ac.za/department-of-institutional-planning/article/2834454/core-students-statistics (Accessed August 29, 2022).

Millea, M., Wills, R., Elder, A., and Molina, D. (2018). What matters in college student success? Determinants of college retention and graduation rates. Education 138, 309–322.

Moeketsi, L., and Maile, S. (2008). High university drop-out rates: A threat to South Africa’s future. HSRC policy brief.

Robayo-Tamayo, M., Blanco-Donoso, L. M., Roman, F. J., Carmona-Cobo, I., Moreno-Jimenez, B., and Garrosa, E. (2020). Academic engagement: a diary study on the mediating role of academic support. Learn. Individ. Differ. 80:101887. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2020.101887

Ryff, C. D. (2014). Self-realisation and meaning making in the face of adversity: A eudaimonic approach to human resilience. J. Psychol. Afr. 24, 1–12.

Schreiner, L. A. (2015). “Positive psychology and higher education. Positive psychology on the college campus” in Positive psychology on the college campus. eds. J. C. Wade, L. I. Marks, and R. D. Hetzel (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 1–25.

Schutte, L., Guse, T., and Wissing, M. P. (2022). Embracing wellbeing in diverse African contexts: research perspectives. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Sheu, H. B., Chong, S. S., and Dawes, M. E. (2022). The chicken or the egg? Testing temporal relations between academic support, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and goal progress among college students. J. Couns. Psychol. 69, 589–601. doi: 10.1037/cou0000628

Sondlo, M. (2019). Stakeholder Experiences of the Quality Enhancement Project in Selected South African Universities. University of Pretoria (South Africa).

Thomas, G. B., and Hanson, J. (2014). Developing social integration to enhance student retention and success in higher education: the GROW@ BU initiative. Widening participation and lifelong learning, 16, 58–70.

Wade, J. C., Marks, L. I., and Hetzel, R. D. (2015). Positive psychology on the college campus. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Weuffen, S., Fotinatos, N., and Andrews, T. (2021). Evaluating sociocultural influences affecting participation and understanding of academic support services and programs (SSPs): impacts on notions of attrition, retention, and success in higher education. J. Coll. Student Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 23, 118–138. doi: 10.1177/1521025118803847

Wilson Fadiji, A., Chigeza, S., and Shoko, P. (2022). Exploring Meaning-Making Among University Students in South Africa During the COVID-19 Lockdown. In Emerging Adulthood in the COVID-19 Pandemic and Other Crises: Individual and Relational Resources. Cross-Cultural Advancements in Positive Psychology. eds. S. Leontopoulou and A. Delle Fave vol 17. (Cham: Springer International Publishing).

Wilson Fadiji, A., Luescher, T., and Morwe, K. (2023). The dance of the positives and negatives of life: student wellbeing in the context of# Feesmustfall-related violence. In S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 37, 1–25.

Wissing, M. P., Schutte, L., and Wilson Fadiji, A. (2019). Cultures of positivity: Interconnectedness as a way of being. In Handbook of Quality of life in African Societies. eds. I. Eloff (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 3–22.

Wissing, M. P., Schutte, L., and Liversage, C. (2022). Embracing well-being in diverse contexts: the third wave of positive psychology and african imprint in Embracing well-being in diverse african contexts: research perspectives. Cross-cultural advancements in positive psychology. eds. L. Schutte, T. Guse, and M. P. Wissing vol 16. (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 3–30.

Keywords: wellbeing, student wellbeing, academic support, higher education, psychosocial intervention

Citation: Wilson Fadiji A and Eloff I (2024) Student wellbeing and academic support in higher education. Front. Educ. 9:1119110. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1119110

Edited by:

Meriem Khaled Gijón, University of Granada, SpainReviewed by:

Emmanuel Biracyaza, Université de Montréal, CanadaRutger Kappe, Inholland University of Applied Sciences, Netherlands

Copyright © 2024 Wilson Fadiji and Eloff. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Angelina Wilson Fadiji, YW5nZWxpbmEud2lsc29uZmFkaWppQGRtdS5hYy51aw==

Angelina Wilson Fadiji

Angelina Wilson Fadiji Irma Eloff

Irma Eloff