94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 03 April 2023

Sec. Special Educational Needs

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.982788

This article is part of the Research TopicAdvancing Research on Inclusion and Engagement in Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) with a Special Focus on Children at Risk and Children with DisabilitiesView all 11 articles

A correction has been applied to this article in:

Corrigendum: Exploring Swedish preschool teachers' perspectives on applying a self-reflection tool for improving inclusion in early childhood education and care

Introduction: In order to provide opportunities for high-quality early childhood education and care for each child, inclusive settings need to develop and sustain their potential to enable participation in terms of attendance and involvement for diverse groups of children. In 2015–2017, the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education completed a project on inclusive early childhood education, focusing on structures, processes, and outcomes that ensure a systemic approach to high-quality inclusive early childhood education. Within the project, a self-reflection tool for improving inclusion, the Inclusive Early Childhood Education Environment Self-Reflection Tool (ISRT), was developed. For purposes of future implementation of the ISRT, the present study focused on the teachers' perspective regarding the ISRT's potential to contribute to enabling all children's participation, defined as attending and being actively engaged in the activities in early childhood education and care. The specific aim was to explore Swedish preschool teachers' perceptions of the ISRT based on their experiences of applying the tool.

Methods: Twelve preschool teachers participated in semi-structured interviews about their experiences of applying the tool. The interviews were analyzed with a thematic analysis.

Results: The thematic analysis resulted in three main themes concerning the teachers' perception of (1) the construction of the ISRT, (2) the time required for using the tool, and (3) the tool's immediate relevance for practice. Each of these themes contained both negative and positive perceptions of the tool.

Discussion: Based on the negative and positive perceptions identified in the three main themes, future research and development of the ISRT in Swedish preschools are discussed. On a general level, the results are discussed in relation to the implementation of the ISRT in terms of acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility.

Children learn and develop through the stimulation and challenges they experience in their social and physical environments. In the early years, Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) provides opportunities for social interaction and learning, and many children spend a large part of everyday life in ECEC. According to the Sustainable Development Goals 2030 Agenda (SDG2030; UN, 2015), quality ECEC is a universal right of all children based on access and participation opportunities in a context where they are engaged and learn. This means that the environment and the practices need to respond to the diversity and needs of all children in an inclusive ECEC.

During the past few decades, the benefits of high-quality ECEC have been acknowledged by the European community and international policymakers [e.g., the United Nations (UN, 2015); United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 1994); United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF); the World Bank; and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2017)]. Furthermore, based on the 1994 Salamanca Statement and the Dakar Framework Education for All from 2000, the Incheon Declaration for Education 2030 sets out a vision for education for the next 15 years based on the UN SDG 2030 (UN, 2015), where an articulated focus on inclusion likewise was emphasized for pre-primary education. The vision of inclusion formulated in these declarations aligns with the general principle for special education in ECEC. It is docking into the fundamental need to be valued and feelings of being a member of a social group as essential in children's everyday life (Haustätter and Vik, 2021). Therefore, inclusion cannot be limited to access to ECEC. It also involves a focus on all children's participation, i.e., that the children are actively engaged in the everyday activities in the setting (Imms and Granlund, 2014; Imms et al., 2017).

The European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (EASNIE) describes inclusion by defining it as all learners of any age being provided with meaningful, high-quality educational opportunities in their local communities, alongside their friends and peers (EASNIE, 2022). This definition focuses that both attendance and participation are necessary to enable inclusion, encompassing both “being there” and “being engaged”. Engagement can be defined by how much time the child interacts in a developmentally and contextually adequate way with the environment (McWilliam and Bailey, 1992; McWilliam and Casey, 2008). Consequently, being engaged in everyday life in ECEC is crucial for children's social and cognitive development and learning, such as playing and interacting with adults, peers, and materials (Aydogan et al., 2015). Engagement leads to child wellbeing, achievements, and positive development (Castro et al., 2017). It is central in studies of early childhood education and inclusion as it can be regarded as an indicator of positive functioning in the early years.

A prerequisite for child wellbeing, achievements, and positive development in an inclusive environment is a high-quality education (Taguma et al., 2013; Soukakou, 2016; Castro et al., 2017; Ginner Hau et al., 2020; Lee and Janta, 2020; Lundqvist, 2020). Earlier research has proven high-quality ECEC to have positive, long-lasting effects on children's development and learning (Shonkoff and Phillips, 2000; Heckman, 2006, 2011; Pianta et al., 2009; Shonkoff, 2010; Melhuish et al., 2015). Recent research in the United States shows that attending ECEC is not per se associated with favorable development and learning later in life. This is instead associated with several factors related to the quality of ECEC (Durkin et al., 2022). Regarding inclusion in ECEC, there is evidence that inclusive settings tend to have higher quality than non-inclusive settings and that high quality is a prerequisite for children's wellbeing and favorable development (Lee and Janta, 2020).

Building teacher capacity for inclusive teaching is fundamental for providing meaningful, high-quality educational opportunities. Subsequently, the education system needs to ensure that the teachers are initially adequately qualified for inclusive teaching and supported throughout their careers. However, most education systems have no comprehensive capacity-building frameworks for inclusive teaching (Brussino, 2021). In order to ensure that teachers have and retain adequate competencies, they have to be regarded as lifelong learners, and continuous professional learning becomes central. The strategies to promote teacher capacity for inclusive teaching in terms of continuous development can, for example, be formal and informal in-service training (Brussino, 2021).

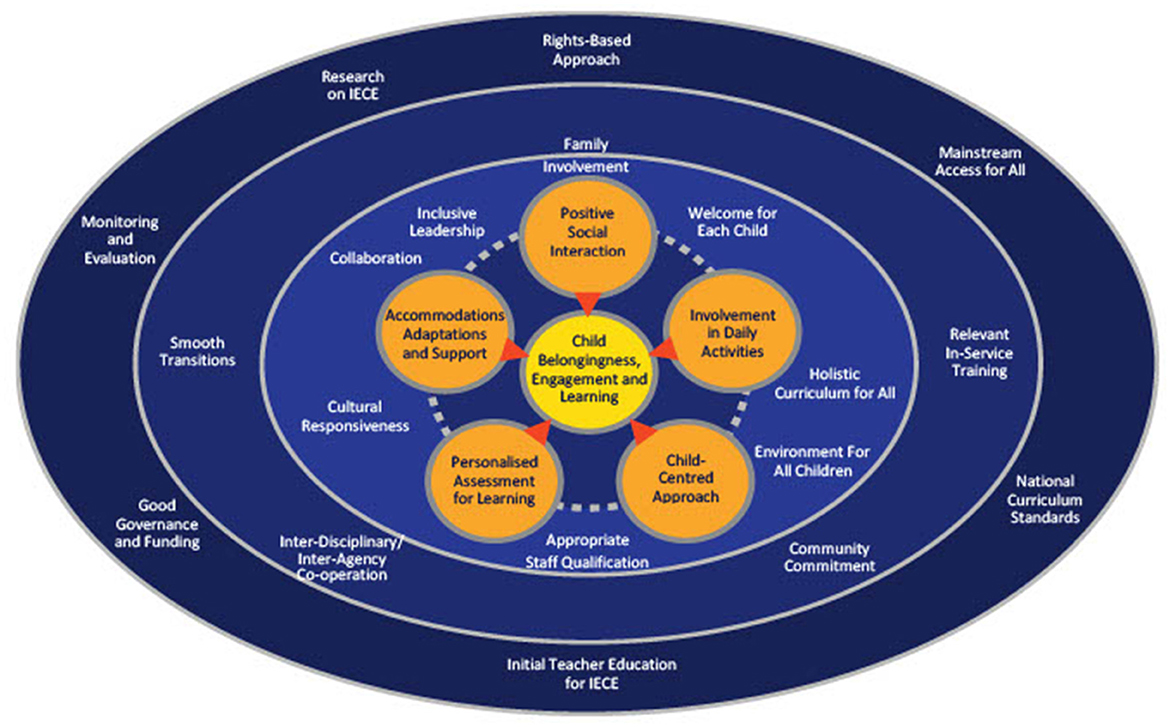

There are several guides and tools for promoting inclusion, which can be used both in teacher training and in schools that want to achieve an inclusive education context (Sandoval et al., 2021). One such tool is the Inclusive Early Childhood Education Environment Self-Reflection Tool (ISRT; EASNIE, 2017b). It was developed as a part of a project on inclusive early childhood education by the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (EASNIE). The ISRT focuses on proximal processes in everyday life in ECEC, i.e., play and interaction with adults, peers, and materials. The proximal processes are necessary for wellbeing, learning, and development and are related to participation, defined as attending, and being actively engaged (Imms et al., 2017). In the ISRT, “engagement” means being actively involved in everyday activities, being the core of inclusion (EASNIE, 2017b), and being an essential aspect of quality in educational settings. The ecosystem model for Inclusive Early Childhood Education (IECE) (see Figure 1) can be used as a model to explain the interaction between ECEC policy and practice to promote child engagement and learning (EASNIE, 2016, 2017a). It can be used to scrutinize the processes in the everyday activities in preschool and support preschool teachers in recognizing factors at different levels that are related to the engagement and learning of all children in preschool. The model is inspired by ecological system theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2006) and based on data from 32 European countries in a project by the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (EASNIE, 2016, 2017a). Furthermore, the model can support practitioners' work to plan, improve, monitor, reflect on, and evaluate inclusion in their everyday practices in IECE. The inclusive process per se reflects the interactions between the child and other children, the practitioners, and the physical environment enabling all children to belong, engage, and learn. National, regional, and local contexts and conditions in the surrounding environments are highlighted as essential structures for the organization and support for IECE.

Figure 1. The ecosystem model of inclusive early childhood education (cited from EASNIE, 2017a, p. 37).

According to the ecosystem model for IECE, there are five primary processes through which children are involved in the everyday life of the setting as follows: positive interaction, involvement in daily activities, a child-centered approach, personalized assessment for learning and accommodations, and adaptations and support. These processes within the setting are supported by the next level by including parents, welcoming each child, a holistic curriculum, a social and physical environment for all children, qualified staff, cultural responsiveness, inclusive leadership, and collaboration. There are additional supportive structures in the surrounding society, such as community commitment, interdisciplinary collaboration, support for transitions, and possibilities for staff training. At the highest level in the model are national/regional structures, rights-based policies for ECEC, mainstream access for all children, national curriculum standards, government and financing, monitoring and evaluation, and initial teacher education.

Based on the ecosystem model of Inclusive Early Childhood Education, the Inclusive Early Childhood Education Environment Self-Reflection Tool (ISRT) was developed (EASNIE, 2017b). Furthermore, it is the five primary processes in the everyday activities in the preschool that are focused on the tool but supportive structures at other levels are also included. The ISRT is available in 25 languages on EASNIE's website, free of charge. For the validation process of the English version of ISRT, refer to EASNIE (2017b).

The ISRT can be applied to capture the social, learning, and material/physical environments in the ECEC setting. It consists of eight dimensions with questions reflecting the preschool's inclusiveness. The dimensions are as follows:

1. Overall welcoming atmosphere (seven questions),

2. Inclusive social environment (seven questions),

3. Child-centered approach (seven questions),

4. Child-friendly physical environment (six questions),

5. Materials for all children (seven questions),

6. Opportunities for communication for all (six questions),

7. Inclusive teaching and learning environment (seven questions), and

8. Family-friendly environment (six questions).

The questions are designed to provide an overall picture of the inclusiveness of the preschool setting. For validation of the tool, see EASNIE (2017b). The ISRT is a non-copyright material and is designed to be used in accordance with the needs of stakeholders and contexts. It is important to recognize that the ISRT is neither a standardized instrument that is supposed to be implemented for a specific purpose defined by the authors, nor is the use connected with strict routines in how it should be applied. Instead, the ISRT provides the practitioners with questions that might support them in reflecting on their practices in relation to inclusion. It aims to support a reflective process by focusing on the preschool's social, learning, and physical environment. The instructions for how to apply the tool clearly state that the tool is intended to be used flexibly, guided by the needs of the practitioners, setting, and organization. It is not designed as a standardized assessment or evaluation tool. Preschool settings are encouraged to decide to focus on all aspects or to select some and, if needed, to add their own questions. Due to this flexible approach, the tool can be applied for multiple purposes and guide improvement by various stakeholders, individually or in a group.

In a previous study (Ginner Hau et al., 2020), the ISRT was used in the Swedish preschool context to understand practitioners' perspectives on inclusive processes and supportive structures. From the process of data collection and the obtained data, the ISRT was considered to be a tool that worked well to collect information on practitioners' views of inclusive processes and supportive structures. In addition to the report on the development of the ISRT (EASNIE, 2017b), there are, to the best of our knowledge, few studies on the ISRT.

In the present study, we explore the Swedish early childhood education teachers' perception of the ISRT based on their experiences of applying the tool. In Sweden ECEC is referred to as preschool. Swedish ECEC is a part of the national school system, regulated by Education Act (SFS, 2010:800) and the national preschool curriculum (Swedish National Agency for Education, 2021). Special preschools for children with disabilities are few and predominantly in larger cities. These preschools serve mainly children with autism spectrum disorders and children with severe multiple disabilities. Thus, regular preschools are strongly recommended for all children to have maximal opportunities to interact with their peers. Swedish preschool staff expresses that they need professional support in order to manage the group and the individual child in need of support (The Swedish Schools Inspectorate, 2017). However, it has been suggested that further development is needed for practice to align with the intentions of inclusive education on the policy level (Garvis et al., 2022). The context for this study is, thus, full-day ECEC and that the preschools are required to have the capacity to welcome all children.

Our previous study (Ginner Hau et al., 2020) identified the ISRT as a potentially useful tool for developing inclusion through a reflective approach that is sensitive to the needs of the practitioners (Ginner Hau et al., 2020). For purposes of future implementation of the ISRT, the present study focused on teachers' perspectives regarding the ISRT's potential to contribute to enabling all children's participation, defined as attending and being actively engaged in the activities in early childhood education and care. The specific aim was to explore Swedish preschool teachers' perceptions of the ISRT based on their experiences of applying the tool.

Based on this aim, the following research questions were formulated:

1. What are the preschool teachers' perceptions of the ISRT, based on their experiences of working with the tool?

2. What possibilities and barriers do the preschool teachers perceive to applying the ISRT in order to facilitate inclusive practices?

As previously mentioned, the ISRT has a high degree of flexibility. Therefore, the application of ISRT cannot be evaluated like a standardized evaluation or assessment tool in terms of to what degree users have adhered to how the tool is intended to be implemented. Hence, we chose to explore the teachers' perceptions of using the ISRT with a semi-structured interview that was analyzed inductively in a thematic analysis (cf., Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2013).

In the current study, 12 preschool teachers participated. The participants were all preschool teachers with a university degree and no further special education qualification. They worked at seven different preschools with children aged 1–5 years in a municipality in Greater Stockholm. The teachers have experience meeting children with varying cultural backgrounds, as many have immigrant backgrounds, and more than 100 languages are spoken in the municipality. All the participating preschool teachers had used the ISRT together with collogues at their regular team meetings at the preschools.

Participants were recruited among preschool teachers that had participated in our previous study (Ginner Hau et al., 2020). Preschools were selected in the order they had reported to have worked with all dimensions of the ISRT. No more than one teacher from each team working with the ISRT was recruited. For recruitment of participants and data collection, two students in the Special Education Program at the Department of Special Education, Stockholm University, Sweden, were involved in the project as a part of their theses. The students contacted the heads of the unit in preschools that had applied the tool and asked for permission to contact the individual preschool teachers. Altogether, contact was taken with 16 of the preschools that had worked with the ISRT.

In the preschools that chose not to participate, either heads of units or teachers declined participation. Without any exception, both heads of units and teachers that chose not to participate did so due to lack of time. After getting permission from the heads of the unit, the students directly asked preschool teachers that had worked with the tool for participation in this study. After an initial contact over the phone, potential participants were emailed with more detailed information about the study and asked to answer the email if they consented to participate. As the recruitment of participants turned out to be challenging, we preliminary regarded 12 participants as sufficient for the objective of the present study. After a preliminary analysis of the collected data, we concluded that no further recruitment was necessary.

Data were collected with individual interviews. These were booked and took place in the participants' workplace, with one out of the two students as the interviewer. The interviews were semi-structured following an interview guide developed by the students and the first author (see Table 1). The interview guide consisted of open-ended questions that focused on the teacher's experience using the ISRT, i.e., questions concerning their experiences of using the ISRT. The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The length of the recorded interviews was 20–30 min, and the transcriptions were 5–7 pages (Times New Roman 12, simple line spacing).

Data were analyzed with a thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2013). We used an inductive approach and carefully followed the phases formulated by Braun and Clarke. Initially, the first author read the interviews in their entirety and took continuous familiarization notes. These notes were the content of potential interest, content perceived as familiar/unfamiliar, ideas for coding, and responses to the data. The familiarization was followed by semantic and selective coding of the transcripts. In this phase, the first author inductively coded data relevant from the perspective of the aim of the study. When the coding was finalized, the first author listed the codes and relevant data for each. As a next step, the first author reviewed coded data and generated initial themes. Similar codes were clustered together to create initial themes that were distinctive and could be regarded as part of a larger whole. In line with Braun and Clarke (2022), the second author reviewed six initial themes and discussed them with the first author in this phase. The two authors agreed on the following six themes for the teachers' perceptions of the ISRT: (a) The ISRT helps to shed light on areas that otherwise would be invisible, (b) the ISRT includes a considerable number of questions that are difficult to know how to answer, (c) the ISRT is helpful by creating the kind of time that is required for reflection, (d) the ISRT requires time that does not exist, (e) the ISRT is with the proper prerequisites as a useful tool, and (f) the ISRT is constructed in a way that makes it unclear how it shall be useful in everyday practices. In this phase of the analysis, the two authors also discussed and agreed that the six themes had a pattern of being contradictive pairs. Even if the themes could be regarded as contradicting each other, as presented in the Result section, pairing the six themes, they constituted three theoretically meaningful main themes. Therefore, the authors considered it more meaningful to pair these six themes into three qualitatively concerning aspects of the preschool teachers' experiences working with the tool. In the continuous process of reviewing and developing themes, the first author identified the nature and character of the pattern of the contradictive pairs and also reviewed their potential to be themed, which the second author then reviewed. Consequently, the first and the second authors discussed the quality, boundaries, and meaningfulness of the three themes and related data. Thenceforth, the first author revised the names of themes and formulated definitions in dialog with the second author. The themes and definitions were not changed in the last phase of writing the results, but when writing the results, we elaborated and further developed them in discussing the results. All themes are illustrated with quotes from the participants.

The current study has followed Swedish legislation of research on people. A review from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority was not required. However, we have followed the All European Academies (2017) code of conduct for research integrity.

Recruitment of participants was conducted so that it would not be possible for employers or colleagues to get information about who had agreed to participate and who had not. Limited background information was collected in order not to enable the identification of participants by employers or colleagues. In addition, general background information was regarded to have a limited value for the study's explorative approach. When transcribing the interviews, all personal details were omitted.

All participants were informed about the study via e-mail and in connection to the interviews. They were asked to give their consent in replying to the initial e-mail. All information about the study was repeated at the beginning of the interview. The participants were informed about the aim of the study, that it was voluntary, and that they could withdraw at any time without any consequences. They were also told that no one other than the interviewers and researchers of the current study would have access to the data and that the data would be anonymized. They got the information that data would be used for a student's master thesis and research on the ISRT. The participating preschool teachers also gave their consent before the interview started.

The three main themes were as follows: (1) The suitability of the construction of the ISRT, which was composed of (a) the ISRT helps to shed light on areas that otherwise would be invisible, and (b) the ISRT includes a considerable number of questions that are difficult to know how to answer. (2) The time required for applying the ISRT, where time shortage was identified as central in applying the ISRT. This was constituted by (c) the ISRT is helpful in creating the time required for reflection, and (d) the ISRT requires time that does not exist. (3) The ISRT's immediate relevance for preschool practice. This theme covered the practitioners' perception of the ISRT based on whether it has instant relevance for practice, which was constituted by (e) with the proper prerequisites the ISRT is a useful tool, and (f) the ISRT is constructed in a way that makes it unclear how it shall be useful in everyday practices.

The ISRT is described as composed of questions that helped the preschool teachers shed light on inclusive structures and processes that otherwise would be invisible to them. However, at the same time, the tool is described as including a considerable number of questions that the participants are unsure how to answer. The statements that signify this theme concern the adequacy of how the questions are formulated, which was a common topic in data and manifested in the interviews in completely contradictive statements. The questions were, on the one hand, considered to be highly adequate. Participants described them as good, clear, and easy to understand and answer. They were also described as constituting a good starting point for reflection on inclusive practices by covering a broad area of relevant topics. To an equal extent, they were described negatively as inadequate and unclear. Participants expressed that they had “got stuck” as they could not figure out the meaning of some questions and that the formulation of many questions was odd. It was also brought up that the yes/no construction of some of the questions in the ISRT did not encourage reflective discussions and that such questions were perceived as contradictive as the ISRT is formulated as a tool for reflection. The following quotations illustrate the theme suitability for the construction of the ISRT:

[The questions were] clear, that... you didn't have to sit and think that much, as soon as a colleague said something, the rest of us could spin on it. (Participant 11)

But there were some questions that felt like, what do they want to know, what are they looking for, and what do they actually mean [for example] by cultural diversity? (Participant 12)

I think all questions are relevant, and we have more or less discussed all questions. (Participant 3)

We thought the questions were rather strangely worded. (Participant 8)

Working with the ISRT is explained by the participating preschool teachers to require time that does not only exist but also creates a temporal space necessary for discussing inclusion. Time is a central aspect for all interviews. Time is described as the main obstacle to using the tool in practice and also reported as the explanation for why participants have not continued working with the ISRT. There are also statements concerning the abundance of documentation the participants are expected to handle in their everyday practices. Consequently, the ISRT requires time that does not exist.

On the other hand, there are statements by the participants regarding the tool as creating the necessary temporal space for discussing central aspects of participation and engagement for each child. Moreover, some participants considered the tool suitable for focusing on a limited number of dimensions or questions at a time by dividing it into smaller sections. The theme time required for applying the ISRT is illustrated by the following quotations:

The only obstacle is the time pressure that you need to organize it with everything you have to do, then I thought these were questions that were really about our work and what is important, but it is so incredibly extensive. It's really our whole everyday practice, so the obstacle is probably just the time. I mean, it must not be an obstacle. We need to find a structure that makes it possible to work with it continuously. (Participant 1)

Then it is the amount of time it takes, and we have a lot of other things … we have forms that we have to fill in every week, every month, and every semester so there is a lot of paperwork. (Participant 9)

We really appreciated this day [working with the tool] when we got to talk about all these areas... (Participant 5)

Time is always an obstacle in preschool because you must prioritize, and working with the children must come first. It is difficult to prioritize reflection and to sit with a bunch of papers and leave our colleagues on their own with the children … it won't be good for the children if you are away too much. (Participant 5)

The ISRT is described both as relevant and irrelevant to preschool practices. Participants believed the tool to have the potential to be very useful with the proper prerequisites. They also thought it was a tool that was very useful for practice. At the same time, it is also described as being constructed in a way that makes it unclear how it shall be useful in practice. The tool is described as relevant as it corresponds with the preschool curriculum. It contributes to daily practice clarifications and gives the participants a good overview of their work. The participants also gave concrete examples of the outcome of reflections on the practice that the tool has initiated. The tool is also suggested as a relevant starting point for weekly reflections.

On the contrary, the ISRT is mentioned as a part of a constant inflow of tools that shall be applied in preschool that does not contribute to practice. The tool is also said to cover broad and general areas, thus not relevant for everyday practices. Contradicting the aforementioned statement that the tool is relevant by being in line with the curriculum is that the tool is not meaningful because many yes/no questions are more or less like a checklist related to the curriculum. The theme of ISRT's immediate relevance for preschool practice is illustrated by the following quotations:

So, this is a good tool for us, also because teachers come and go. This is a tool that can guide us toward the goals we have. (Participant 4)

It is evident that it is carefully developed and that it is based on the curriculum. I think it is very good because all these questions are what our mission is. (Participant 12)

We can get preschool teachers who have completed an education that can do this, but then we have preschool teachers who can barely formulate a vision regarding the activities she wants to run. So, it becomes difficult to add a tool like this that requires you to know what inclusion means. You should know and be able to formulate yourself. I also see this as a shortcoming. (Participant 10)

… it was pretty easy to use, I thought, but I do not know what function it should fill. (Participant 8)

For the purposes of future implementation of the ISRT, the present study focused on the teachers' perspective regarding the ISRT's potential to contribute to enabling all children's participation, defined as attending, and being actively engaged in the activities in early childhood education and care. The specific aim was to explore Swedish preschool teachers' perceptions of the ISRT based on their experiences of applying the tool. In the analysis of the interviews, we identified three main themes on a general level related to the teachers' experiences of using the ISRT. The first general central theme concerned the suitability of the construction of the ISRT. This theme dealt with both negative and positive perceptions of how the questions in the ISRT are constructed. The positive perceptions underlined that the ISRT includes questions covering significant aspects of inclusive education. The negative perceptions stressed that it was unclear how to answer a considerable amount of the questions. In general, this generates contradictive implications for future adaptations of the ISRT for Swedish preschools and probably for ECEC. It indicates that an adaptation would require studying the teachers' perception of individual questions in more detail.

The second general central theme concerned the time required for working with the ISRT. In our data, lack of time was expressed as a barrier to applying the ISRT. The tool was also regarded as an opportunity to create temporal space for discussions that would not take place otherwise. As described initially, Swedish ECEC is a full-day preschool for children aged 1–5 years. Considering the context of full-day preschools, it is reasonable to assume that a barrier to using the tool is the limited opportunities for joint reflections, such as the ISRT requires. However, as expressed in the interviews, making time available to work with the ISRT is itself a way to prioritize joint reflections. This might be particularly valuable in a context such as Swedish preschools. Both with regard to the full-day preschool offering limited opportunities of joint time for reflection and that for a universal preschool that welcomes all children, such reflections can be regarded as a prerequisite for a high-quality ECEC. From this perspective, our results imply that the ISRT can contribute to creating opportunities to overcome barriers associated with a lack of time for joint reflections.

Finally, the ISRT's relevance for practice was a central general theme. The theme captured data that described the ISRT as relevant for practice if applied under the proper circumstances and also statements regarding the ISRT as irrelevant for practice. This theme implies the need for in-depth studies of the teacher's view of specific sections of the tool. This could be a way to find out more in detail why some teachers consider the tool irrelevant. Based on such detailed information, adaptations to the Swedish context might increase to what degree the tool is considered relevant. As the tool is constructed in a European context, it is reasonable to assume that implementation in other European contexts will raise questions similar to our interviews. Therefore, even if one of the ISRT's strengths is that it is based on data from more than 30 European countries, some adaptations for individual countries might be necessary to make the tool relevant for inclusive everyday practices.

At a higher level of abstraction, the qualities of the themes align with general aspects of implementation. As we discussed initially, a core feature of ISRT is the tool's flexibility, which is supposed to be adjusted to the specific needs of each preschool context. It is up to the end users to decide for what purposes the tool shall be applied in their particular settings (cf., EASNIE, 2017b). In contrast to standardized tools, the ISRT has no clear directions for how it should be applied. Instead, it is intended to be implemented in the most useful ways for practice. Even so, on this more abstract level, the identified themes can be considered to correspond to fundamental implementation challenges in general. The interpretation of the results led us to connect each of the three main themes to three central concepts of implementation: acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility (Proctor et al., 2011). Therefore, regarding the ISRT as an innovation for supporting teachers to promote inclusive education, these three concepts could be considered aligned with the three inductively identified main themes.

Proctor et al. (2011) have defined acceptability as “the perception among implementation stakeholders that a given treatment, service, practice, or innovation is agreeable, palatable, or satisfactory” (Proctor et al., 2011, p. 67). For the acceptability of the ISRT, the perceptions of how the questions in the tools are formulated are central. As mentioned previously, the construction of the questions was both appreciated and criticized by participants. It could be interpreted that those who appreciated the questions understood the instrument's basis as a reflection tool. They used the questions as a starting point for reflections rather than questions that shall be answered. In contrast, those who perceived the tool as a regular evaluation tool and tried to understand the exact meaning of the questions and deliver a clear answer probably became more frustrated.

Based on Karsh (2004) and Proctor et al. (2011, p. 69) define feasibility as “the extent to which a new treatment, or an innovation, can be successfully used or carried out within a given agency or setting”. Whether the ISRT is feasible for practice is likely to depend on several factors. However, the time aspect can be assumed to be critical. Similar to the other two themes, this theme is constituted of contradictive statements that clearly establish time as a central aspect of the tool's feasibility. What is unexpected is that the tool is actually perceived as creating time for discussions of inclusive education. While some participants find the tool far too extensive, others introduce ideas on how the tool could be applied by discussing one area at a time based on the needs of the settings. It might be that those who find the tool feasible regarding time have acknowledged the possibilities they have to design how to apply the ISRT, whereas those who find the tool too demanding in regard to time might perceive it as a traditional evaluation tool.

Appropriateness is defined as “the perceived fit, relevance, or compatibility of the innovation or evidence-based practice for a given practice setting, provider, or consumer; and/or perceived fit of the innovation to address a particular issue or problem” (Proctor et al., 2011, p. 69). In line with this definition, the results from the current study concerning participating preschool teachers' beliefs of the relevance of the ISRT in promoting inclusive education can be considered as corresponding to the concept of appropriateness. Some experience the tool as helpful in everyday practices, whereas others find it difficult to see the ISRT's relevance for practice. It should be noted that some of the difficulties the participants express could be related to the freedom they have to adjust the tool for the needs of their specific settings might not be sufficiently communicated.

This study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to explore teachers' perceptions of applying the ISRT. The study provides valuable information for future implementation of the ISRT. However, the study also has limitations, mainly related to the limited number of participants recruited from a geographically restricted area. For confidentiality reasons, we chose not to collect detailed information about the participants. Further knowledge about the participants could have contributed to the comprehensiveness of our data. None of the participants had a special education degree, thus, this type of instrument might have been unfamiliar to them. In addition, the participants had limited experience with using the tool, and we did not follow their processes for applying it over time. The teachers' perceptions of the tool are, however, in line with the findings in our previous study, for example, concerning problems with how some of the questions are constructed (Ginner Hau et al., 2020). The results should not be generalized. Nevertheless, our results could be assumed to have relevance for other contexts inside and outside Sweden. There is a need for further implementation studies on the ISRT.

The ISRT is a tool that should support reflective processes regarding the preschool's social, learning, and physical environment (EASNIE, 2017b). According to its instructions, it is a tool intended to be used flexibly, guided by the needs of the practitioners, setting, and organization. The ISRT should not be implemented as a standardized assessment or evaluation tool. Even so, some participants appear to assume that they are supposed to apply the ISRT for evaluative purposes. One possible explanation for this could be the emphasis on evaluations in Swedish preschools (Swedish National Agency for Education, 2011, 2018). Possibly, this can have led practitioners to regard the purposes of discussions and documentation to be solely evaluative rather than joint reflections having an intrinsic value.

Furthermore, evaluations in Swedish preschools usually aim to identify measures that need to be undertaken, which might also have hindered practitioners from appreciating the reflective approach of the ISRT. Therefore, introducing a tool such as the ISRT in a context such as the Swedish preschools requires careful consideration of what barriers a well-established evaluative tradition might constitute for implementing a tool that aims to promote reflective processes. However, some of the questions of the ISRT partly have a construction that does not necessarily support reflection (Ginner Hau et al., 2020). Revising the formulation of some questions might enhance the potential of the tool to encourage reflection.

Feasibility in the Swedish context could be improved by guiding stakeholders in planning their work with the ISRT. For example, by adding concrete instructions and examples pointing to the importance of deciding what they want to achieve when using the tool. Such instructions might improve users' confidence in choosing their purposes with the tool and adapting it to their needs in developing inclusive education. A more general interpretation is that for an unstandardized tool without fixed procedures, there are challenges in communicating how it should be applied.

One of the strengths of the ISRT is that it is based on information about structures and processes collected in ECEC in most European countries (EASNIE, 2017a,b). There are, however, linguistic aspects that should be considered. The tool was constructed with English as the working language, and the validation was performed based on the English version (cf., EASNIE, 2017b). The tool has been translated into more than 20 languages, of which Swedish was one. However, ecological validation is necessary for using the ISRT in different countries with different languages and practices. Subsequently, the results regarding comprehensiveness may be interpreted as the necessity for such an ecological validation for the tool to be implemented in Swedish preschools.

Finally, exploring the application of the ISRT, both in the current study and in our previous study (Ginner Hau et al., 2020), the results can be interpreted as shedding light on participation not only as a key for inclusion in terms of children's participation but also in terms of practitioners' active engagement. In turn, this could be regarded in the light of the potential to increase the preschools' capacity to enable all children's participation. The development and use of tools such as the ISRT require that teachers are motivated to be engaged in each child's active participation and inclusive practices. Hence, acceptance, appropriateness, and feasibility for tools such as the ISRT might best be achieved by co-production in close collaboration with practitioners in preschools.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

HG contributed to the initial conception and design of the study, the design of procedures and performing of the data collection, and has lead the writing of the manuscript. HG performed data-analysis in continuous cooperation with HS and with EB in the final discussions of the analysis and interpretation of the results. HS and EB have contributed to the drafting the manuscript as well as revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors have approved the submitted version.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the participating municipality and the preschools who generously contributed to this report. Also, the authors acknowledge Amal Abbas and Emelie Addensten, for taking part in the data collection as students at the Department of Special Education, Stockholm University. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the support from the National Agency for Special Needs Education and Schools, SPSM. This work has developed from a project implemented and publications produced by the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education: https://www.european-agency.org/projects/iece.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

All European Academies (2017). Code of Conduct for Research Integrity, Revised Edition. ALLEA. Available online at: https://www.allea.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/ALLEA-European-Code-of-Conduct-for-Research-Integrity-2017.pdf (accessed March 14, 2023).

Aydogan, C., Dale, C., Farran, D. C., and Sagsöz, C. (2015). The relationship between kindergarten classroom environment and children's engagement. Eur. Early Childh. Educ. Res. J. 23, 604–618. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2015.1104036

Braun, V., and Clarke, C. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2013). Successful Qualitative Research. A Practical Guide for Beginners. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2022). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qual. Psychol. 9, 3–26. doi: 10.1037/qup0000196

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U., and Morris, P. A. (2006). “The bioecological model of human development,” in Handbook of Child Psychology, Vol.1: Theoretical Models of Human Development, 6th Edn, eds W. Damon, and R.M. Lerner (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley), 793–828.

Brussino, O. (2021). “Building capacity for inclusive teaching: Policies and practices to prepare all teachers for diversity and inclusion,” in OECD Education Working Papers, No. 256 (Paris: OECD Publishing).

Castro, S., Granlund, M., and Almqvist, L. (2017). The relationship between classroom quality-related variables and engagement levels in Swedish preschool classrooms: a longitudinal study. Eur. Early Childh. Educ. Res. J. 25, 122–135. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2015.1102413

Durkin, K., Lipsey, M. W., Farran, D. C., and Wiesen, S. E. (2022). Effects of a statewide pre-kindergarten program on children's achievement and behavior through sixth grade. Dev. Psychol. 58, 1385. doi: 10.1037/dev0001301

EASNIE (2016). “Inclusive early childhood education: an analysis of 32 European examples,” in eds P. Bartolo, E. Björck-Åkesson, C. Giné and M. Kyriazopoulou. Odense: Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education. Available online at: https://www.european-agency.org/sites/default/files/IECE%20%C2%AD%20An%20Analysis%20of%2032%20European%20Examples.pdf (accessed March 14, 2023).

EASNIE (2017a). “Inclusive early childhood education: new insights and tools – final summary report,” in eds M. Kyriazopoulou, P. Bartolo, E. Björck-Åkesson, C. Giné, and F. Bellour (Odense: European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education). Available online at:https://www.european-agency.org/sites/default/files/IECE-Summary-ENelectronic.pdf (accessed March 14, 2023).

EASNIE (2017b). “Inclusive early childhood education environment self-reflection tool,” in eds E. Björck-Åkesson, C. Giné, and P. Bartolo (Odense: European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education). Available online at: https://www.european-agency.org/sites/default/files/IECE%20Environment%20Self-Reflection%20Tool.pdf (accessed March 14, 2023).

EASNIE (2022). About us – Who We Are. European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education. Available online at: https://www.european-agency.org/about-us/who-we-are#:~:text=The%20European%20Agency%20for%20Special,ensuring%20more%20inclusive%20education%20systems (accessed March 14, 2023).

Garvis, S., Uusimaki, L., and Sharma, U. (2022). “Swedish early childhood preservice teachers and inclusive education,” in Special Education in the Early Years. International Perspectives on Early Childhood Education and Development, Vol. 36, eds H. Harju-Luukkainen, N. B. Hanssen, and C. Sundqvist (Cham: Springer), 87–100.

Ginner Hau, H., Selenius, H., and Björck ?kesson, E. (2020). A preschool for all children? - Swedish preschool teachers' perspective on inclusion. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 26, 973–991. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2020.1758805

Haustätter, R., and Vik, S. (2021). “Inclusion and special needs education: towards a framework of an overall perspective of inclusive special education,” in Dialogues Between Northern and Eastern Europe on the Development of Inclusion: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives, eds N. B. Hanssen, S.-E. Hansèn, and K. Str?m (London: Routledge), 18–32.

Heckman, J. J. (2006). Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science 312, 1900–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.1128898

Heckman, J. J. (2011). The economics of inequality: the value of early childhood education. Am. Educ. 35, 31–35.

Imms, C., and Granlund, M. (2014). Participation: are we there yet. Aust. Occup. Therapy J. 61, 291–292. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12166

Imms, C., Granlund, M., Wilson, P., Steenbergen, B., Rosenbaum, P., and Gordon, A. (2017). Participation, both a means and an end: a conceptual analysis of processes and outcomes in childhood disability. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 59, 16–25. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13237

Karsh, B. T. (2004). Beyond usability: designing effective technology implementation systems to promote patient safety. Qual. Saf. Health Care 13, 388–394. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.010322

Lee, S., and Janta, B. (2020). Strengthening the Quality of Early Childhood Education and Care Through Inclusion. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union. Available online at:https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/d25366dd-c578-11ea-b3a4-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed March 14, 2023).

Lundqvist, J. (2020). “A good education for all children during early schoolyears – characteristics, evaluation and development,” in Specialpedagogik för Lärare, ed M. Westling Allodi (Stockholm: Natur and Kultur), 115–140.

McWilliam, R. A., and Bailey, D. B. (1992). “Promoting engagement and mastery,” in Teaching Infants and Preschoolers With Disabilities, 2nd Edn, eds D. B. Bailey, and M. Wolery (New York, NY: Merrill), 229–256.

McWilliam, R. A., and Casey, A. M. (2008). Engagement of Every Child in the Preschool Classroom. Paul H Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

Melhuish, E., Ereky-Stevens, K., Petrogiannis, K., Aricescu, A., Penderi, E., Rentzou, K., et al (2015). A Review of Research on the Effects of Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) on Child Development. WP4.1 Curriculum and Quality Analysis Impact Review (CARE). Available online at: https://ecec-care.org/fileadmin/careproject/Publications/reports/new_version_CARE_WP4_D4_1_Review_on_the_effects_of_ECEC.pdf (accessed March 14, 2023).

OECD (2017). Starting Strong 2017 – Key OECD Indicators on Early Childhood Education and Care. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/education/starting-strong-2017-9789264276116-en.htm (accessed March 14, 2023).

Pianta, R., Barnett, W., Burchinal, M., and Thornburg, K. (2009). The effects of preschool education: What we know, how public policy is or is not aligned with the evidence base, and what we need to know. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 10, 49–88. doi: 10.1177/1529100610381908

Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., et al. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administ. Policy Mental Health Serv. Res. 38, 65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7

Sandoval, M., Muñoz, Y., and Márquez, C. (2021). Supporting schools in their journey to inclusive education: review of guides and tools. Support Learn. 36, 20–42. doi: 10.1111/1467-9604.12337

SFS 2010:800. Skollag. Available online at: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/skollag-2010800_sfs-2010-800 [Education act] (accessed March 14, 2023).

Shonkoff, J. (2010). Building a new biodevelopmental framework to guide the future of early childhood policy. Child Dev. 81, 357–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01399.x

Shonkoff, J. P., and Phillips, D. A. (2000). From Neurons to Neighborhood. The Science of Early Childhood Development. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Soukakou, E. P. (2016). Inclusive Classroom Profile (ICP) Manual, research edition. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Swedish National Agency for Education (2011). National Curriculum for Preschool. Stockholm: Skolverket. Available online at: https://www.skolverket.se (accessed March 14, 2023).

Swedish National Agency for Education (2018). National Curriculum for Preschool. Stockholm: Skolverket. Available online at: https://www.skolverket.se (accessed March 14, 2023).

Swedish National Agency for Education (2021). Children and Staff in Preschool. Available online at: www.skolverket.se (accessed June 10, 2022).

Taguma, M., Litjens, I., and Makowiecki, K. (2013). Quality Matters in Early Childhood Education and Care: Sweden 2013. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/education/school/SWEDEN%20policy%20profile%20-%20published%2005-02-2013.pdf (accessed March 14, 2023).

The Swedish Schools Inspectorate (2017). How the Preschool Works With Support for Children in Need of Special Support. Skolinspektionen.

UN (2015). The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations. Available online at: http://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/?menu=1300 (accessed March 14, 2023).

Keywords: early childhood education and care, teachers' perspective, engagement, involvement, participation, inclusion, self-reflection tool

Citation: Ginner Hau H, Selenius H and Bjorck E (2023) Exploring Swedish preschool teachers' perspectives on applying a self-reflection tool for improving inclusion in early childhood education and care. Front. Educ. 8:982788. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.982788

Received: 30 June 2022; Accepted: 23 February 2023;

Published: 03 April 2023.

Edited by:

Geoff Anthony Lindsay, University of Warwick, United KingdomReviewed by:

Majlinda Gjelaj, University of Pristina, AlbaniaCopyright © 2023 Ginner Hau, Selenius and Bjorck. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hanna Ginner Hau, aGFubmEuaGF1QHNwZWNwZWQuc3Uuc2U=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.