94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 17 May 2023

Sec. Language, Culture and Diversity

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.967148

This study aims at exploring the multilingual practices of users in digital communication. The study utilizes “translanguaging’ as a framework to analyze and unravel these multilingual practices based on four stances of translanguaging. The data for the study are gathered through an open-ended questionnaire that seeks detailed views of respondents who are active users of Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter, Instagram, and other social platforms. The study includes participants from diverse sociocultural backgrounds with the ability to have knowledge of more than one language with proficiency. The results correlate with the first two points of model, i.e., translanguaging blurs the boundaries between languages to convey meanings and introduce new concepts but deviates from the last two points. It also throws light on the impact of digital communication on local languages and presents suggestions for the preservation and promotion of local languages in the digital landscape, such as the provision of accurate translations of native languages, digital dictionaries, keyboards, and software.

According to the constitution of 1973, both English and Urdu are recognized as official languages in Pakistan, but Eberhard et al. (2020) claim that Pakistan is a multicultural and multilingual country with at least 70 official languages. However, Urdu is the country’s primary language, while English is spoken primarily among the country’s upper-class (Rahman, 2006). Balti, Burushaski, and Brahui are all part of the ethnic group, but many others in addition to them are spoken in different parts of the country. Because of this, each province has its ethnic groups with their own culture and language.

The study samples comprised postgraduate students from various campuses of the University of Education, Lahore, Pakistan. Multiple campuses of the university cover almost all the regions that touch the Punjab province. In Punjab, Punjabi is spoken across the province, with its northern border shared with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where the Hindko dialect is spoken. In the east, Multani and Seraiki are spoken as official languages. Except for a few indigenous communities along the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Afghanistan borders, most of Baluchistan province’s residents speak Balochi. People of Karachi city prefer Urdu over Sindhi, the provincial language spoken in Sindh province. The northern part of this province has found that the Seraiki language is both useful and pleasant. The people of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa speak Pushto as their common language, except for the northern area, where Chitrali is spoken. Pakistan’s zones have more overlapping regional languages, which promotes multilingualism. Pashtoons in Hazara District know Pushto and Hindko, and many Hindkowals can speak Pushto. Sindhi and Seraiki speakers over the Sindh–Punjab border are bilingual. The reason for engaging postgraduate students is that they know various languages with research backgrounds.

With over 61.34 million internet users, digital communication has become more important in all walks of public and professional life in Pakistan (Jamil, 2021). As Warschauer et al. (2002) point out, English was the dominant language online for a long time, and this has had a significant effect on Peoples’ linguistic preferences. Approximately 80% of the global population on the web was reported to interact in English in the mid-1990s (Kimball, 1997), but this dropped to 72% in 2002 (O’Neill et al., 2003), so current internet trends show that the internet is not just for English users but for many other languages too. Some of these languages belong to small linguistic groups that are spread out geographically or lack the economic means to fully capitalize on mass media campaigns (Warschauer et al., 2002). Nowadays, people all around the world may use the internet to write to one another in their native languages and dialects (Warschauer et al., 2002). According to Top Ten Internet Languages in The World (2019) the Internet has matured into a reliable worldwide communications platform. As a result, 70% of all online conversations take place in languages other than English, making the Internet a truly global and cosmopolitan space (Lee, 2007), and Grosjean (2010) argues that many individuals, even if they are fluent in just one language, utilize (Translanguaging) another language for communication.

Translanguaging describes this fluid and dynamic multilingual discursive technique. The term “bilingual” comes from the Welsh word “Trawsiethu,” and it refers to the process of communicating in two languages (L1 for input and L2 for output), as explained by Williams (2009). Baker (2011) describes translanguaging as a complex discursive process that Garcia and Kano (2014) call inequality in language. Moreover, this process is including how language users create and maintain new language practices. This strategy asserts that the use of many languages in discourse does not favor any one language over another in the cultural realm, and thus helps those who speak a language other than the majority language to feel more at ease.

COVID-19’s wave of digitization has changed literacy and language policies not only in Pakistan but around the world (Lundby, 2014). From 2020 to 2021, the use of digital media among young Pakistanis grew by 21%, suggesting that it may play a role in easing intergenerational communication and academic progress. In the words of Turkle (1996) and Nakamura (2013), it is common to think of the Internet as a place where people can reinvent themselves online and where language borders can be dismantled because of the widespread use of digital tools for producing, writing, conversing, and remixing in both formal and informal settings.

Multiple studies in CMC (computer-mediated communication) have attempted to probe the connection between digital multilingualism and identity negotiation in cross-cultural online communication. Moreover, research into CMC has also evolved to include analyses of data on multilingual concerns communicated over a variety of channels (Androutsopoulos, 2015), including e-mail (Said et al., 2007), instant messaging (Lee, 2007), and chat rooms. Despite extensive studies on conventional communicational technologies in CMC, the prospective changes in linguistic practices concerning translanguaging have received less attention owing to recent paradigm shifts during the COVID-19 era.

The purpose of this research is to explore the language preferences and possible causes of multilingual practices, factors involving linguistic choices, and the effects of digital communication on the indigenous languages of Pakistan. Moreover, this research also investigates the contexts in which members of certain communities use their native tongues and the languages they interact with outside of those communities. The importance of digital media in fostering the use and adoption of indigenous languages for communication is also highlighted. Policymakers may use the results to assist indigenous languages to survive among the local populace.

The study is limited to all campuses of the University of Education Lahore, Pakistan, and its postgraduate students who are regular digital media users and belong to diverse cultures. The choice of respondents from the University of Education Lahore is mainly because of the ease of availability of people belonging to different parts of Pakistan in one space and their acquaintance with digital multilingual practices. These students fulfill the criteria for the research participants. Moreover, the study is beneficial to explore the general multilingual practices of digital media in the Pakistani context since the world is progressing forward to digitalization and globalization. The study also highlights the consequent benefits as well as harms of translanguaging and multilingual practices faced by people in Pakistan by keeping in mind their native languages.

Monolingual prejudices have a long and storied history, and as a result, linguistic hybridity is typically seen as a socially unacceptable and linguistic stigma that is increasing periodically (Crystal, 1986; Heller, 2007; Baker, 2011; MacSwan et al., 2017). According to Creese (2017), this linguistic stigma can be noticed in pedagogy which is an ideologically maintained social practice or idea that a certain language (or set of languages) has intrinsic worth and should be imposed on the whole country to maintain a certain level of communication quality. However, Gafaranga (2007) see this idea from a different perspective and considers that bilinguals lack proficient knowledge of either language. Against semi-lingual, researchers (Cummins, 2000; Grosjean, 2010; Baker, 2011) started to promote multi-lingual language used in classrooms and have challenged the notion of other critics who considered the use of multiple languages as a deficiency.

In the age of digitalization, it is not unusual to witness the practice of various languages that are often both multilingual on different platforms on social media (Androutsopoulos, 2015; Dovchin, 2017; Dumrukcic, 2020). At present, digital use has become a basic need in our lives. Castells (2010) claims that online communication on social media is completely different from previously monolingual interactions because it is not only a medium of communication but also a platform to present ourselves to the rest of the world. However, Hine (2000) considers this communication as a for-granted reality. In line with Castells and Hine, Lee (2007) argues that the reason for multiple language practices is related to lexical choices based on multilingual resources in their digital interactions.

The Internet is often considered a digital space for the reconstruction of identity (Turkle, 1996; Nakamura, 2013). Many CMC researchers (Warschauer et al., 2002; Boyd and Ellison, 2007; Williams, 2009; Androutsopoulos, 2015) tried to explore the relationship between digital multilingualism and the negotiation of identities in a multicultural interaction on the internet. People use social media platforms for commenting and posting to interact and such interactions from various cultures give birth to translanguaging patterns. Moreover, Bolander and Locher (2015), Schreiber (2015), Bou-Franch and Blitvich (2018), and Nguyen et al. (2018) have also conducted a study on the connection between social media and language used to address the construction of identity because these social platforms provide all their users with ample space to express themselves, their identities, and their core value. Modern technology offers creative ways of sharing and interacting with people.

Both code-switching and translanguaging have their characteristics. Code-switching, as described by Auer (2019, p. 1), is “the juxtaposition of two codes (languages) that is perceived and interpreted as a locally meaningful event by participants,” and as further defined by Lewis et al. (2012, p. 657), “creative strategies used by the language user” to accomplish discourse-related tasks in everyday interaction. Despite their superficial similarities, code-switching and translanguaging refer to distinct cognitive processes. Translanguaging study claims that bilinguals and multilingual have a highly complex system encapsulating the competencies that are part of the repertoires of their language which includes styles, pragmatic competence, abstract concepts, a variety of semiotics, registers, cultural and social norms, and multi-model features (Canagarajah, 2011; Otheguy et al., 2015; Wei, 2018). This shows that there is an epistemological variation between code-switching and translanguaging. Garcia and Kleyn (2016) argue, code-switching bases on two different cognitive systems while translanguaging talks about one integrated system developed by the features from various languages. Translanguaging also encompasses various notions as being part of a certain culture or standing in or out of a community.

The theory has been advocated by many researchers (Garcia, 2009; Canagarajah, 2011; Wei, 2014; Creese et al., 2018), but the present study is based on Myers-Scotton and Jake (2009) stance on translanguaging and multilingual practices because, unlike most other approaches to Code Switching (CS), Myers-Scotton and Jake (2009) argues that translanguaging model enjoys widespread appeal among linguists and psycholinguists because of its universality and suitability to address the research questions. As Jake, Heredia and Altarriba (2001, p. 166) posit, a major gap in the study of “code-switching” is the absence of appropriate models from which to derive testable research hypotheses. Interestingly, literature on language acquisition and development is often cited by proponents of the two main approaches to general linguistics, the nativist approach (Chomsky, 1972; Crain and Nakayama, 1987; Radford, 2004) and the functional approach (Bresnan, 2000; Croft, 2000). Moreover, the translanguaging model shows that people follow translingual practices to introduce new concepts and ideas that for Valdés (1981) is a “rational choice” of people, while Myers-Scotton and Bolonyai (2001) consider it as a personal “choice” where people excludes certain items from their interactions to recall proper lexical items during communication and to impress others. The translanguaging model has been modified and exploited by various researchers by focusing on classroom environment, educational spheres, and impacts of translanguaging in their English medium classrooms (Omar, 2007; Jorgensen and Fenger, 2008; Li and Zhu, 2013; Conteh, 2018; Rafi and Fox, 2020; Zahra et al., 2020; Ali, 2021; Hussain and Khan, 2021) but missed a chance to explore these practices on a digital platform in Pakistan. To fill the gap, this article will focus on the current phenomenon that remains unexplored in the Pakistani digital landscape. Earlier, any researcher, to the best of researchers’ knowledge, has not analyzed and highlighted this issue that the present study aims at bridging this gap.

This research delves into the translanguaging and multilingual behaviors of digital media users. Participants in the research are regular users of digital platforms for social or professional communication. The study is based on an open-ended questionnaire due to restrictions brought by the active COVID-19. Another reason for choosing an open-ended questionnaire is to get a comprehensive view of participants regarding their linguistic choices and to know the personality traits of the respondents relevant to this study on digital platforms. Researchers used several social media channels including Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter, and Instagram to contact the respondents. The open-ended questions were sent, and responses were collected by using Google Forms which consists of ten questions. Questions focus on how respondents feel about multilingual practices, what they view as the obstacles to monolingualism, and how they feel digital media relates to the survival of their original language. Each question is developed using an Excel sheet and similar responses are placed in one category. Each question is discussed, and the results are elaborated on in the results section. The qualitative method was used to draw conclusions on the chosen framework. The research relies on an in-depth survey of respondents to learn more about their preferences in online language interaction on WhatsApp, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, which are some of the digital channels available. The following criteria are developed for the study:

1. The study included participants belonging to different age groups, sociocultural backgrounds, gender, and mother languages studying at all campuses of the University of Education.

2. All participants are supposed to know and speak more than one language and one of them should preferably be English.

3. The participants are supposed to be active users of digital media and digital communication on platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, and Instagram.

4. Each participant is given ample time to respond to the open-ended questions of the study based on their own experience in digital communication.

The target population was postgraduate students from nine campuses at the University of Education, Pakistan. The selection or reason of postgraduate students is that they have enough knowledge and command of multiple languages that were not possible at the undergrad level due to (Nonnative English country). Moreover, the target population hail from a wide range of cultural backgrounds and is often exposed to languages other than their own. Regarding the mechanism, we missed students from other universities due to the constraint of the COVID-19 period as well as the non-availability of proper respondents that fulfill our study criteria. As most of the universities either do not have enough students from different regions/province who have command of multiple languages or universities campuses are available at the edge of regions/provinces hence it made it difficult to get a multilingual student. Moreover, even if researchers succeeded in contacting a few students from other universities but they did not respond and participated enthusiastically. As a bonus, the researchers were able to collect data quickly and efficiently by contacting around 300 respondents who are now studying at the various campuses of the University of Education, Lahore Pakistan. Respondents belong to diverse sociocultural backgrounds with the ability to have knowledge of more than one language with proficiency and to fulfill our purpose,

The study comprises 25% males and 42% females of age groups ranging between 27 and 45. The researchers received 80% responses but 67% were filled with the notion of gravity. The campuses’ total population ratio explains why so many different languages are spoken there. Lahore campuses—like all of Pakistan—are dominated by the Punjabi language. Other languages are spoken exclusively in certain campuses of University of Education, Lahore Pakistan while Urdu is spoken throughout the country. This increases the potential audience size of Punjabi and Urdu languages. Only 1.6% of the population can speak Sindhi fluently, 3.3% speak Seraiki, 3.3% speak Burushki, 36.1% speak Urdu, 50.8% speak Punjabi, and 3.3% speak both Urdu and Punjabi as their native tongue. Participants are all fluent in more than one language and meet all other research requirements (Figures 1, 2).

The survey revealed that 34.4% of participants prefer using the English language for communicating on digital platforms such as Facebook, WhatsApp, and Twitter, whereas 37.7% of participants feel comfortable translanguaging between Urdu and English for better communication. However, 20% of participants use Urdu and their native languages during interaction on these digital platforms (Figure 3).

The study highlighted that a higher percentage of the participants prefer the use of their native languages in Romanized font. Approximately 50.8% use Romanized letters to communicate in digital space, whereas 49% of users prefer their native language font. The ratio of people who mix both fonts is 3.3% (Figure 4).

The survey showed that due to the relative ease of writing in English, 19.7% of participants prefer to communicate in that language. A quarter of respondents (29.5%) rate convenience as more important than difficulty. In total, 26% of participants use their native language for interaction in part because they are fluent in it and want to present their native languages in digital space, and 24% of participants make linguistic choices to convey their message effectively by translanguaging due to limited knowledge of languages (Figure 5).

Digital communication is often seen as friendly and highbrow by the participants. The possibility to continue developing their bilingualism and expanding their linguistic horizons is made possible by this. Most respondents (78.8%) credit digital communication for fostering international understanding and cooperation, while 14.8% report being dissatisfied with its lack of sophistication. Yet 6.6% of the sample is undecided on this issue (Figure 6).

As a result of language obstacles and difficulties in expression, internet communicators often resort to translanguaging services. Table 1 in the index contains the collected replies. Several of these replies are included in the text below too:

Example 1.

‘Sometimes people do not understand what I am saying. Lack of communication creates misunderstanding.’ (Respondent 1).

Example 2.

‘Sometimes people do not understand what I am saying. Lack of communication creates misunderstanding.’ (Respondent 2).

Example 3.

‘some words are misunderstood by people. Having limited language proficiency. Symbols may be misunderstood.’ (Respondent 3).

Most respondents agreed that modern forms of electronic communication, such as social media, are helping to break down barriers between different languages and spreading the idea of translanguaging, in which there is no such thing as a “deaf language” or “foreign language,” but rather the languages of minorities are used to communicate. Table 2 of the index contains the replies; here is a selection of them.

Example 1.

It provides a platform to communicate. (Respondent 1).

Example 2.

Sort of as with the vast use of abbreviations and short forms of words people now, easily communicate with anyone, anywhere. (Respondent 2).

Example 3.

Because it is mixing the languages’ originality. People use code. Switching for their ease and neither of the structure or form of languages is followed. (Respondent 3).

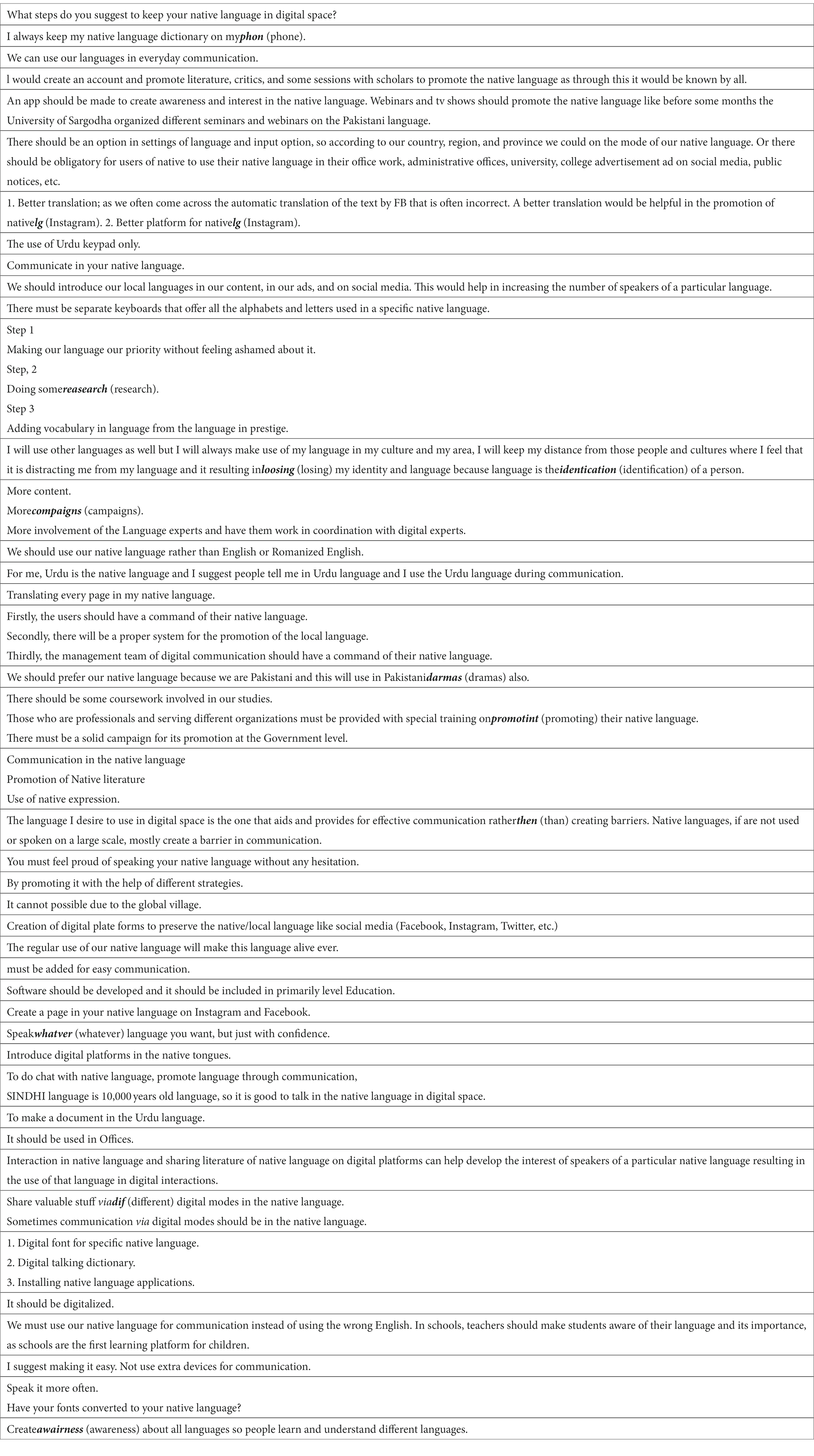

According to 75.3% of participants, digital communication can be used for the preservation and promotion of native languages and suggested steps to keep their native languages on the internet. Table 3 contains all the responses of the participants. Some of the responses are as follows:

Table 3. Respondents’ replies pertaining to importance of digital Communication and promotion of Native Languages.

Example 1.

I always keep my native language dictionary on my phone (Respondent 1).

Example 2.

We can use our languages in everyday communication. (Respondent 2).

Example 3.

I would create an account and promote literature, critics, and some sessions with scholars to promote the native language as through this it would be known by all. (Respondent 3).

The new pandemic COVID-19 has shifted a huge mass of the population in the country to digital platforms, to get an education, work from home and connect with their friends and family. This interaction is carried out through different linguistic choices on part of the user. This section addresses the research questions in light of our findings and the four principles of Myer-Scotten (1979) chosen for the study.

The study revealed that digital multilingualism is blurring the boundaries between languages through integrated communications in various languages due to ease of communication and comprehension. Most of the respondents use both Urdu and English for interactions on these social platforms while preferring Romanized English for writing Urdu. Myer-Scotten (1979) claim that most people use translanguaging to impress other people which for Myers-Scotton and Jake (2009) is an appealing factor for users. Creese et al. (2018, p. 193) posit that we are all ‘multilingual’, and concepts like translanguaging challenge traditional concepts such as ‘standard’ and ‘target’ language, with their implied hierarchies of languages. Our study with 45.7% of respondents agrees with this by claiming that users integrate languages to convey their messages but that does not necessarily mean they want to impress people in informal communications. Moreover, most of the respondents may be using translanguaging without being aware of it since all of them are multilingual and there is a possibility of its unconscious use to impress others. The responses in the examples show and propose that translanguaging, among other concepts, opens important questions related to language choice by illuminating how linguistic resources are deployed in our societies and how this resource deployment reproduces, negotiates, and contests social difference and social inequality.

Example 1.

‘Use of English words instead of Urdu because of the general trend.’ (Respondent 17).

Example 2.

‘It is difficult to see the reality in digital communication, the communicator might pose or fake things. The proverb “Social media is fake” is quite relatable here.’ (Respondent 27).

The responses of respondents postulate that people incorporate multilingual practices to convey their meanings and interact effectively Myers-Scotton and Jake (2009) calls a ‘mixture of languages’ because people fail to recall lexical items at that moment. Scotten further claims that people use multilingual practices to introduce new concepts. In line with Scotten, researchers Canagarajah (2011), Wei (2011), Axelrod and Cole (2018) propose the notion of ‘translanguaging space’ at a digital platform where multilingual repertoires interact and co-produce new meanings. Various factors affect the linguistic choices of the digital media users in Pakistan such as lack of proficiency in one language due to its colonizing history (ex-colony of British), no mutual ground for languages, and introduction of alienated subjects and conveyance of meanings to avoid misunderstandings (Crystal, 1986; Mansoor, 2005; Hussain and Khan, 2021; see example no 1). Our result shows that among the respondents, 43.5% favored multilingual practices and integration of languages (translanguaging) as a tool to communicate effectively while 13.3% claimed, this integration of language has gained momentum due to a lack of knowledge of one language, and the remaining remained neutral.

Example 1.

Sometimes I do not find s lexical item to convey what I want to say. Then I switch to my native language. (Respondent 9).

Example 2.

‘Sometimes people do not understand what I am saying. Lack of communication creates misunderstanding.’ (Respondent 2).

Most of the audience complies with the stance of Myer-Scotten (1979) that they seek refuge in language while introducing new concepts.

Digital communication can be used as an effective medium for the propagation and revitalization of native languages where social media is a “mediated sites” (Reershemius, 2017) and people can resign and spread language (Kukulska-Hulme, 2012). However, some people considered multilingual practices on digital media as a threat to their native languages instead of a ‘heritage language’ that has less worth in their arguments (Stewart, 2014; Velázquez, 2017). However, when we talk about the prestige of multilingualism and translanguaging, our result shows that 35% of people regarded it as a source of prestige whereas the remaining focused on using their native language for communication and interaction. Moreover, the results show that female respondents are mostly in the favor of these multilingual and translanguaging practices and find it as a way to convey meanings and bridge the gap of the lack of knowledge, whereas male respondents are inclined toward seeing it as a threat to the survival of their native language and also suggested that our national and cultural languages are our source of pride, and we should not hesitate to use them. This reflects that even today translanguaging is carrying the burden of being labeled as an inferior phenomenon in Pakistani digital space but there is still room vacant to spread awareness about how social media can be used as a constructive tool to avoid native languages from extinction. Digital translanguaging can aid second language learning. Melo-Pfeifer and Araújo e Sá (2018) identify various multilingual interactions in romance chat rooms as a source of multiple language acquisition. The constant exposure to translingual utterances on the digital platform by incorporating languages can promote language learners to use various words and phrases from other languages.

Example 1.

‘We must use our native language for communication instead of using the wrong English. In schools, teachers should make students aware of their language and its importance, as schools are the first learning platform for children’. (Respondent, 27).

Example 2.

‘To do chat with native language, promote language through communication, SINDHI language is 10,000 years old language, so it is good to talk in native language on digital space’. (Respondent 54).

The study concludes that digital multilingualism is blurring the boundaries between languages through integrated communications of various languages. Moreover, the study reveals respondents make frequent use of multi-lingual practices and translanguaging to interact with people with diverse linguistic backgrounds to convey their messages and meanings effectively. Most of the respondents did not find digital communication as a threat to their native language. Although, they suggested various steps that should be taken to promote and preserve their native languages in the digital space such as the availability of accurate translations, the development of digital applications, digital talking dictionaries, and awareness campaigns on digital platforms in native languages to keep them alive and preserved.

Suffice it to say that the study complies with the first two stances of Myer-Scotten (1979), i.e., people follow translingual practices and code-switching due to a lack of knowledge or failure to recall proper lexical items during communication and to introduce new concepts and ideas. On one side of the study’s graph, individuals utilize mixed-language interactions to exclude others from conversations, while on the other, translingual activities are used to impress others. The study shows that translanguaging can open horizons of ease and facility for people who lack complete knowledge of one language in digital markets and online workspaces. It is a source to connect people from diverse cultural backgrounds with the efficacy of interaction.

This study will help the researchers to focus on the resilience of people they have toward translanguaging. Moreover, this study will be helpful for immigrant children who always have a fear of identity concerning their language vulnerability.

Tables 1–3 reveal the response of various respondents.1

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

MA and SN have drafted the manuscript. SK did a substantial contributions to the conception, analysis and ZB did a interpretation of data for the work. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^Bold and italic words are the real response from respondents therefore authors have not changed them to make a clear difference. Moreover, the authors have corrected those words albeit covered them in parenthesis.

Ali, A. (2021). Understanding the role of translanguaging in L2 acquisition: applying Cummins’ cup model. J. Cult. Ling. 2, 15–25. doi: 10.37301/culingua.v2i1.10

Androutsopoulos, J. (2015). Networked multilingualism: some language practices on Facebook and their implications. Int. J. Biling. 19, 185–205. doi: 10.1177/1367006913489198

Auer, P. (2019). Translanguaging’or ‘doing languages’? Multilingual practices and the notion of ‘codes. Lang. Multiling, 13, 1–31.

Axelrod, Y., and Cole, M. W. (2018). ‘The pumpkins are coming… vienen las calabazas… that sounds funny’: translanguaging practices of young emergent bilinguals. J. Early Child. Lit. 18, 129–153. doi: 10.1177/1468798418754938

Baker, C. (2011). Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Bolander, B., and Locher, M. A. (2015). “Peter is a dumb nut”: status updates and reactions to them as ‘acts of positioning’in Facebook. Pragmatics 25, 99–122.

Bou-Franch, P., and Blitvich, P. G.-C. (2018). Relational work in multimodal networked interactions on Facebook. Internet Pragmat. 1, 134–160. doi: 10.1075/ip.00007.bou

Boyd, D. M., and Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social network sites: definition, history, and scholarship. J. Comput. Commun. 13, 210–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x

Canagarajah, S. (2011). Codemeshing in academic writing: identifying teachable strategies of translanguaging. Mod. Lang. J. 95, 401–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01207.x

Castells, M. (2010). Globalisation, networking, urbanisation: reflections on the spatial dynamics of the information age. Urban Stud. 47, 2737–2745. doi: 10.1177/0042098010377365

Conteh, J. (2018). Translanguaging as pedagogy–a critical review. Routledge Handb. Lang. superdiversity, 473–487. doi: 10.4324/9781315696010-33

Crain, S., and Nakayama, M. (1987). Structure dependence in grammar formation. Language (Baltim). 63, 522–543. doi: 10.2307/415004

Creese, A. (2017). “1. Translanguaging as an everyday practice” in New Perspectives on Translanguaging and Education (De Gruyter: Bristol: Multilingual Matters), 1–9.

Creese, A., Blackledge, A., and Hu, R. (2018). Translanguaging and translation: the construction of social difference across city spaces. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 21, 841–852. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2017.1323445

Crystal, D. (1986). Prosodic development. Lang. Acquis., 2, 33–48. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511620683.011

Cummins, J. (2000). Language, Power, and Pedagogy: Bilingual Children in the Crossfire. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Dovchin, S. (2017). The role of English in the language practices of Mongolian Facebook users: English meets Mongolian on social media. English Today 33, 16–24. doi: 10.1017/S0266078416000420

Dumrukcic, N. (2020). Translanguaging in social media. Output for FLT didactics. heiEDUCATION J. Transdisziplinäre Stud. zur Lehrerbildung.

Eberhard, D. M., Simons, G. F., and Fennig, C. D. (2020). Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 22nd Edn. Dallas: SIL International.

Gafaranga, J. (2007). code-switching as a conversational strategy. in Handbook of multilingualism and multilingual communication, 5, 17.

Garcia, O. (2009). “Education, multilingualism and translanguaging in the 21st century” in Social Justice Through Multilingual Education (Bristol: Multilingual Matters), 140–158.

Garcia, O., and Kano, N. (2014). Translanguaging as process and pedagogy: developing the English writing of Japanese students in the US. Multiling. Lang. Educ. Oppor. Chall., 258–277. doi: 10.21832/9781783092246-018

Garcia, O., and Kleyn, T. (2016). Translanguaging with Multilingual students. Learning From Classroom Moments. New York, NY; London: Routledge. 258.

Heredia, R. R., and Altarriba, J. (2001). Bilingual language mixing: why do bilinguals code-switch? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 10, 164–168. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00140

Hussain, S., and Khan, H. K. (2021). Translanguaging in Pakistani higher education: a neglected perspective! J. Educ. Res. Soc. Sci. Rev. 1, 16–24.

Jamil, S. (2021). From digital divide to digital inclusion: challenges for wide-ranging digitalization in Pakistan. Telecomm. Policy 45:102206. doi: 10.1016/j.telpol.2021.102206

Jorgensen, J. N., and Fenger, R. (2008). Languaging: Nine Years of Poly-lingual Development of Young Turkish-Danish Grade School Students. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen, Faculty of Humanities.

Kimball, S. (1997). Cybertext/cyberspeech: writing centers and online magic. Writ. Cent. J. 18, 30–49. doi: 10.7771/2832-9414.1378

Kukulska-Hulme, A. (2012). “Language learning defined by time and place: a framework for next generation designsLeft to my own devices: learner autonomy and Mobile-assisted language learning–Google books” in Innovation and Leadership in English Language Teaching. ed. J. E. Díaz-Vera (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited).

Lee, C. K.-M. (2007). Affordances and text-making practices in online instant messaging. Writ. Commun. 24, 223–249. doi: 10.1177/0741088307303215

Lewis, G., Jones, B., and Baker, C. (2012). Translanguaging: developing its conceptualisation and contextualisation. Educ. Res. Eval. 18, 655–670. doi: 10.1080/13803611.2012.718490

Li, W., and Zhu, H. (2013). Translanguaging identities and ideologies: creating transnational space through flexible multilingual practices amongst Chinese university students in the UK. Appl. Linguist. 34, 516–535. doi: 10.1093/applin/amt022

MacSwan, J., Thompson, M. S., Rolstad, K., McAlister, K., and Lobo, G. (2017). Three theories of the effects of language education programs: an empirical evaluation of bilingual and English-only policies. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 37, 218–240. doi: 10.1017/S0267190517000137

Mansoor, S. (2005). Language Planning in Higher Education: A Case Study of Pakistan. Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

Myers-Scotton, C., and Bolonyai, A. (2001). Calculating speakers: codeswitching in a rational choice model. Lang. Soc. 30, 1–28. doi: 10.1017/S0047404501001014

Myers-Scotton, C., and Jake, J. (2009). A Universal Model of Code-switching and Bilingual Language Processing and Production, England: Cambridge University Press.

Melo-Pfeifer, S., Lee, J. B., Rossi, R. A., Ahmed, N. K., Koh, E., and Kim, S. (2018). Continuous-time dynamic network embeddings. In Companion proceedings of the the web conference, 969–976.

Nguyen, G. H., and Araújo e Sá, M. H. (2018). Multilingual interaction in chat rooms: translanguaging to learn and learning to translanguage. International journal of bilingual education and bilingualism, 21, 867–880.

Nakamura, L. (2013). Cybertypes: Race, Ethnicity, and Identity on the Internet United Kingdom: Routledge.

Otheguy, R., García, O., and Reid, W. (2015). Clarifying translanguaging and deconstructing named languages: A perspective from linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review 6, 281–307.

O’Neill, E. T., Lavoie, B. F., and Bennett, R. (2003). Trends in the evolution of the Public Web. D-lib Mag. 9, 1–10. doi: 10.1045/april2003-lavoie

Radford, A. (2004). Minimalist Syntax: Exploring the Structure of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rafi, M. S., and Fox, R. K. (2020). Translanguaging and multilingual teaching and writing practices in a Pakistani University: pedagogical implications for students and faculty. HumaNetten Nr 45 Hösten 2020, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3827643

Rahman, T. (2006). Language policy, multilingualism and language vitality in Pakistan. Trends Linguist. Stud. Monogr. 175:73.

Reershemius, G. (2017). Autochthonous heritage languages and social media: writing and bilingual practices in low German on Facebook. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 38, 35–49. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2016.1151434

Said, G., Waschauer, M., and Zohry, A. (2007). Language choice online: globalization and identity in Egypt. Multiling. Internet, 7, 302–316.

Schreiber, B. R. (2015). “I am what I am”: multilingual identity and digital translanguaging. Lang. Learn. Technol. 19, 69–87.

Stewart, M. A. (2014). Social networking, workplace, and entertainment literacies: the out-of-school literate lives of newcomer Latina/o adolescents. Read. Res. Q. 49, 365–369. doi: 10.1002/rrq.80

Top Ten Internet Languages in The World (2019). Internet Statistics. https://www.internetworldstats.com/stats7.htm. (Accessed April 4, 2023).

Turkle, S. (1996). Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. New York, NY: Simon \& Schuster, 347.

Valdés, G. (1981). Codeswitching as deliberate verbal strategy: a microanalysis of direct and indirect requests among bilingual Chicano speakers. Lat. Lang. Commun. Behav., 21, 95–108.

Velázquez, I. (2017). Reported literacy, media consumption and social media use as measures of relevance of Spanish as a heritage language. Int. J. Biling. 21, 21–33. doi: 10.1177/1367006915596377

Warschauer, M., Said, G. R.El, and Zohry, A. G. (2002). Language choice online: globalization and identity in Egypt. J. Comput. Commun. 7,:JCMC744, doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2002.tb00157.x

Wei, L. (2011). Moment analysis and translanguaging space: discursive construction of identities by multilingual Chinese youth in Britain. J. Pragmat. 43, 1222–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2010.07.035

Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging knowledge and identity in complementary classrooms for multilingual minority ethnic children. Classr. Discourse 5, 158–175. doi: 10.1080/19463014.2014.893896

Williams, L. (2009). Sociolinguistic variation in French computer-mediated communication: a variable rule analysis of the negative particle ne. Int. J. Corpus Linguist. 14, 467–491. doi: 10.1075/ijcl.14.4.02wil

Keywords: multilingualism, translanguaging, Pakistan, local languages, COVID-19, social media

Citation: Ahmad MS, Nawaz S, Khan S and Bukhari Z (2023) Digital Pakistan in COVID-19: rethinking language use at social media platforms. Front. Educ. 8:967148. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.967148

Received: 26 July 2022; Accepted: 03 April 2023;

Published: 17 May 2023.

Edited by:

Bo Yin, Yangtze Normal University, ChinaReviewed by:

Khan Sardaraz, University of Science and Technology Bannu, PakistanCopyright © 2023 Ahmad, Nawaz, Khan and Bukhari. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Muhammad Sohail Ahmad, c29oYWlsLmFobWFkQHVlLmVkdS5waw==; Shazmeen Nawaz, c2hhem1lZW5uYXdhekBob3RtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.