- Department of Industrial Psychology, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa

Introduction: A qualitative evidence synthesis was employed, to identify and synthesize the best evidence on the experiences of precariously employed academics in high education institutions.

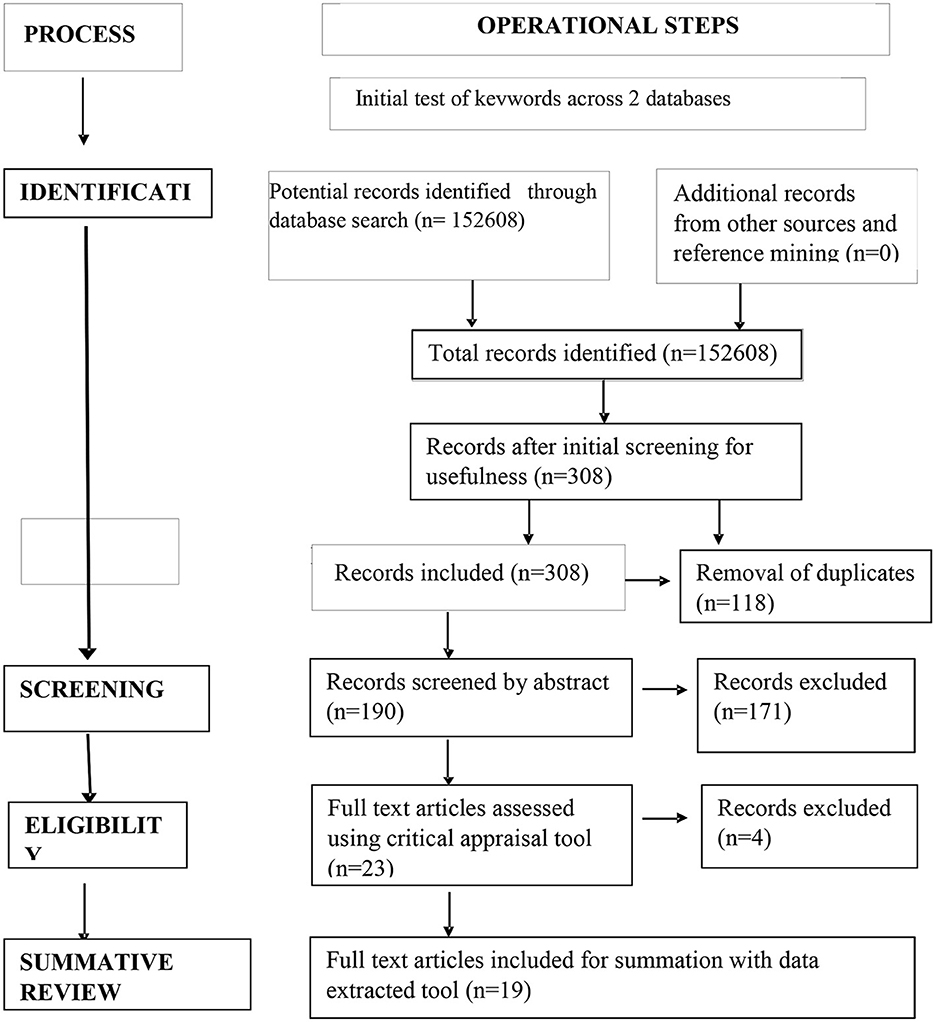

Methods: The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) principles were followed. The identified studies were screened by titles and abstracts (n = 308)-full-text (n = 19), employing these inclusion criteria: studies reporting on precarious employment experiences in higher education; part-time or fixed-term academic positions; qualitative studies between 2010 to 2021. The selected studies were not limited to a particular geographical location. A quality appraisal was conducted. Data were extracted while findings from the included studies (n = 19) were collated using meta-aggregation with the Joanna Briggs Institute Qualitative Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-QARI). The primary study findings emanated from research conducted across 14 countries both from the northern and southern hemispheres.

Results: Ninety-four extracted findings were aggregated into 19 categories and then grouped into five synthesized findings: (1) Precarity is created and perpetuated through structural changes in the global economy and wider higher education landscape; (2) Coping strategies precariously employed academics used to endure precarious employment in higher education; (3) Gendered dimensions shaping employment precarity in academia; (4) Impact of precarious employment on academics; (5) Impact of academic precarity on the university.

Discussion: These precariously employed academics felt overwhelmed, vulnerable, exploited, stressed, anxious, and exhausted with their employment conditions. These circumstances include operating in unstable and insecure employment with no guarantees of permanent employment. The need to reassess policies and practices within higher education institutions is necessary and could offer these precariously employed academics the much-needed support and assistance to combat the effects of precarious employment.

1. Introduction

In recent years, higher education institutions (HEIs) have endured radical transformations globally. The rapidly growing trend of casualisation in the academic workforce is under scrutiny (O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019). This inclination is partial because of a decrease in permanent posts and changes to university employment practices owing to unpredictable international funding sources (Blackham, 2020). HEIs globally must contend with shrinking state funding leading to financial instability; however, limited research explores the experiences of those in precarious academic employment by what can be observed as the most vulnerable within the academic ranks (O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019).

Researchers and activists across various disciplines emphasize the widespread employment of precarious workers to conduct core activities in HEIs (Ragins and Cornwell, 2001; De Cuyper et al., 2009; Blustein et al., 2016; Allan et al., 2017). Research focusing on academic labor often excludes those in non-standard forms of employment (O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019) and has yet to be comprehensively explored from a global perspective. Oakley (1995) and Reay (2000, 2004) offer exceptions, asserting that contract academics are positioned in the lower ranks of HEIs, drawing parallels between contract work and housework concerning how it is undervalued compared to other forms of academic labor.

Various dimensions of precarious employment exist. First, precarious work departs from the norm of stable, permanent, and full-time employment. Researchers explored the ways employment differed from the standard flexible form (Spreitzer et al., 2017), atypical, non-standard work (Kalleberg, 2000) and alternative work arrangements (Katz and Krueger, 2019).

Tompa et al. (2007) operationalised two forms of non-standard work, such as involuntary part-time work and involuntary temporary work—uncertainty concerning continuity work quantity. Second, precarious employment encompasses economic insecurity in low income or lack of access to benefits, such as health insurance and retirement benefits. For example, precarious employment might not offer a living wage or stable income, satisfying basic needs (Allan et al., 2017).

Third, precarious work offers employees inadequate power and autonomy. This deficit can lead to limited collective bargaining rights or limited access to processes to express grievances and opportunities to exercise organizational rights (Allan et al., 2021). Fourth, precarious employment often entails a lack of rights and protection in the workplace. Several organizations lack workplace guidelines and regulations to safeguard against exploitation and harassment (Sterling and Allan, 2020). Organizations with workplace policies, may not implemented them (Allan et al., 2021).

Last, precarious employment could entail unsafe working conditions in a physical or psychosocial capacity (Tompa et al., 2007). For example, those in precarious employment often rely on their employers to survive, therefore, placing them in vulnerable positions, often entailing harassment and abuse (Perry et al., 2020).

In a neoliberal university, precarious workers are often undervalued, overused, and stigmatized, lacking the capacity to secure a permanent position within the academy (O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019). Research, considered a core skill within the academy, is devalued if conducted by academics in precarious employment (O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019). Further research is required because of the rising occurrence and practice of precarious work arrangements. This research is significant because the impact on individuals in these precarious roles are wholly underestimated and deserve to be highlighted to address unequal work practices, inequalities and minimizing the negative impact on the health and wellbeing of precariously employed academics.

Further research would present a comprehensive understanding of the reported experiences of individuals engaged in precarious work, especially in higher education; therefore, this article attempts to synthesize the reported subjective experiences of precarious employment within HEIs.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

A qualitative evidence synthesis identified published literature on experiences of precarious work within HEIs. Qualitative evidence synthesis can be described as a methodology involving primary study findings. These conclusions are systematically collected and interpreted in expert judgements, illustrating a comprehensive understanding of this phenomenon (Bearman and Dawson, 2013).

This qualitative evidence synthesis (QES) aimed to identify and synthesize the published evidence on the subjective experiences of academics in precarious employment in HEIs. This review employed the meta-aggregative approach entrenched in the pragmatism philosophy. Subscribing to the theory that power is knowledge and the real value comes in practical use and implementation (Pearson and Hannes, 2012).

2.2. Eligibility criteria

Research was included in the review based on the predetermined criteria, such as focusing on precarious work experiences within the higher educational contexts (all forms of higher educational institutions) conducted from 2010 to 2021. For the review, precarious work includes non-permanent academic work, such as part-time, short-term, fixed-term, hourly paid, zero-hour contracts and individuals in non-tenured academic employment (Allmer, 2018). The criteria include the various academic roles within HEIs. Studies needed to be peer-reviewed articles published in the English language. The study samples had to represent academic staff in precarious employment within HEIs. The last decade indicated a rapid increase in non-standard employment practices in HEIs, leading to the timeframe for synthesis (Blackham, 2020). Studies conducted in languages other than English were excluded.

2.3. Search strategy

The databases include ScienceDirect, Scopus, Emerald Insights, South African electronic publications, Wiley Online, Google Scholar, Sage Journals Online, and Annual Reviews, provided their scope of publications and relevance to the research focus area. Two reviewers systematically searched these databases in November 2021. Initial feasibility searches indicated relevant and suitable findings to continue with the review. The keywords included in this review are “precarious employment, higher education, academia, experiences, fixed-term contracts, fixed-term employment, temporary employment, and academics”. Combinations of keywords were used, including the Boolean operator AND, and NOT, to search the selected databases (Figure 1) systematically. The search strings used for this review are:

1. Precarious employment AND higher education.

2. Precarious employment AND academia.

3. Precarious employment AND experiences AND higher education.

4. Fixed-term contracts AND higher education AND academia.

5. Fixed-term employment AND higher education AND academia.

6. Temporary NOT permanent employed AND academics.

The limiters applied to this review included full-text, peer-review, and English language, published between 2010 to 2021. Both reviewers applied these limiters consistently to the included search strings.

2.4. Study selection

Academic staff employed within HEIs formed the target population for this review. Studies included qualitative research designs from publications. The research needed to report on the experiences of those in precarious academic roles within HEIs. This study comprises a QES of selected primary research study findings and, therefore, excludes previous QES reviews conducted. Studies that did not include academics in the target population, did not form part of the synthesis.

2.5. Research outcomes

Two reviewers screened the selected studies independently at various stages of the selection and inclusion processes. The search strategy yielded (n = 152,608) records. Records after initial screening titles (n = 308) and the duplicates were removed (n = 118). Records were screened by titles and abstracts (n = 190), with records excluded (n = 171). The total was assessed using the critical appraisal tool (n = 23) with (n = 4) excluded. The total number of articles included for summation with the Joanna Briggs Institute Qualitative Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-QARI) (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2014) data extraction tool (n = 19).

2.6. Methodological appraisal

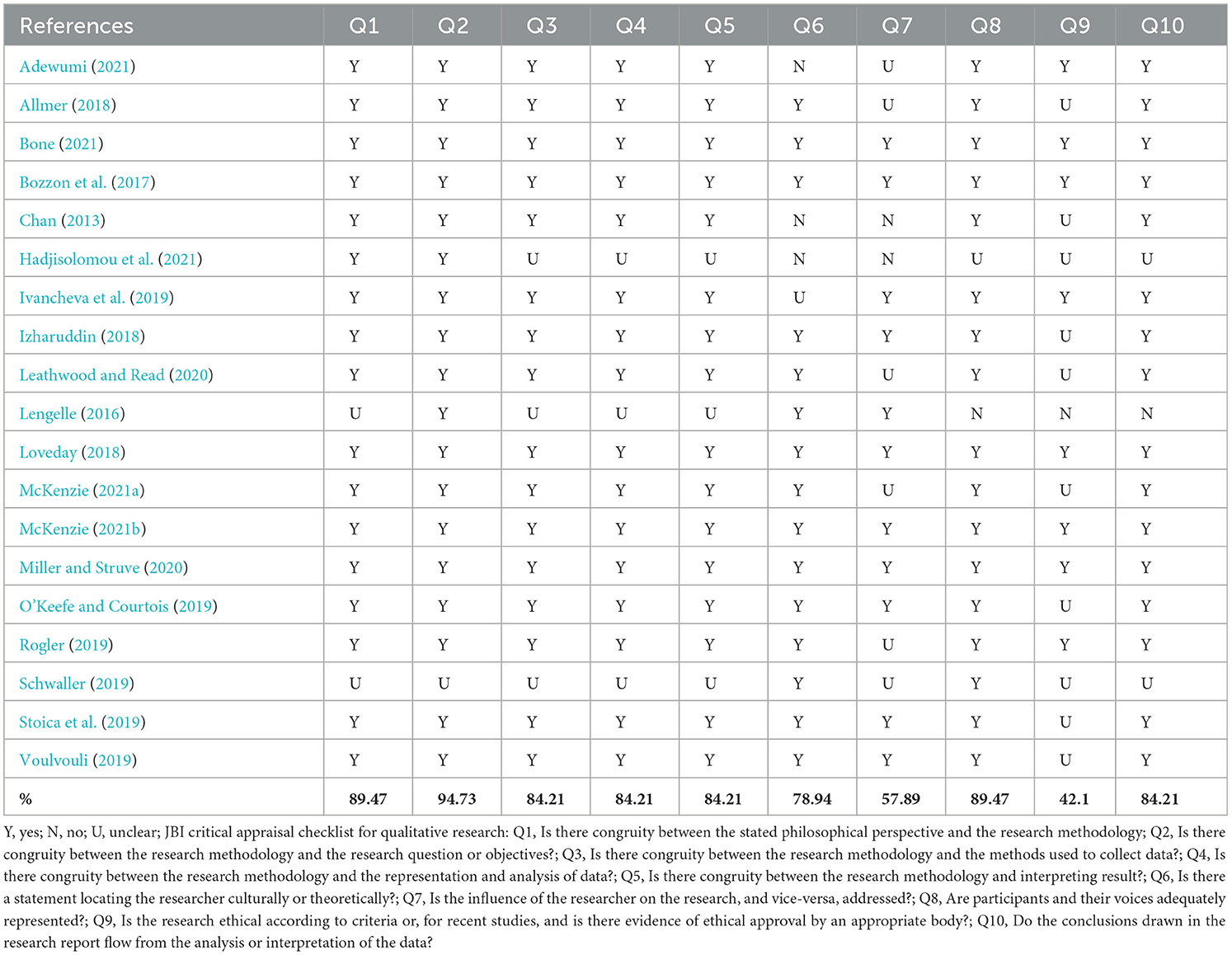

The primary studies included in the synthesis were assessed for methodological quality by employing the JBI-QARI (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2014). The JBI-QARI tool is a 10-point quality assessment checklist, with each question rated as “yes”, “no”, or “unclear”. This tool emphasizes the association between philosophical observation and research methodology. Emphasis is also placed on the congruity among the selected methodology, the data collection methods, the analysis, and the interpretation of the research findings (Lockwood et al., 2015). The appraisal tool was used to assess the methodological quality of the primary studies, it was not used as an exclusionary measure. Two researchers operated independently to quality appraise the primary study findings. Credibility was assigned to the respective primary studies based on the reviewer's perception of the support level provided for the study findings. Only reliable findings were included (Lockwood et al., 2015). Most of the included studies (n = 19) illustrated sound methodological quality (Table 1).

2.7. Data extraction

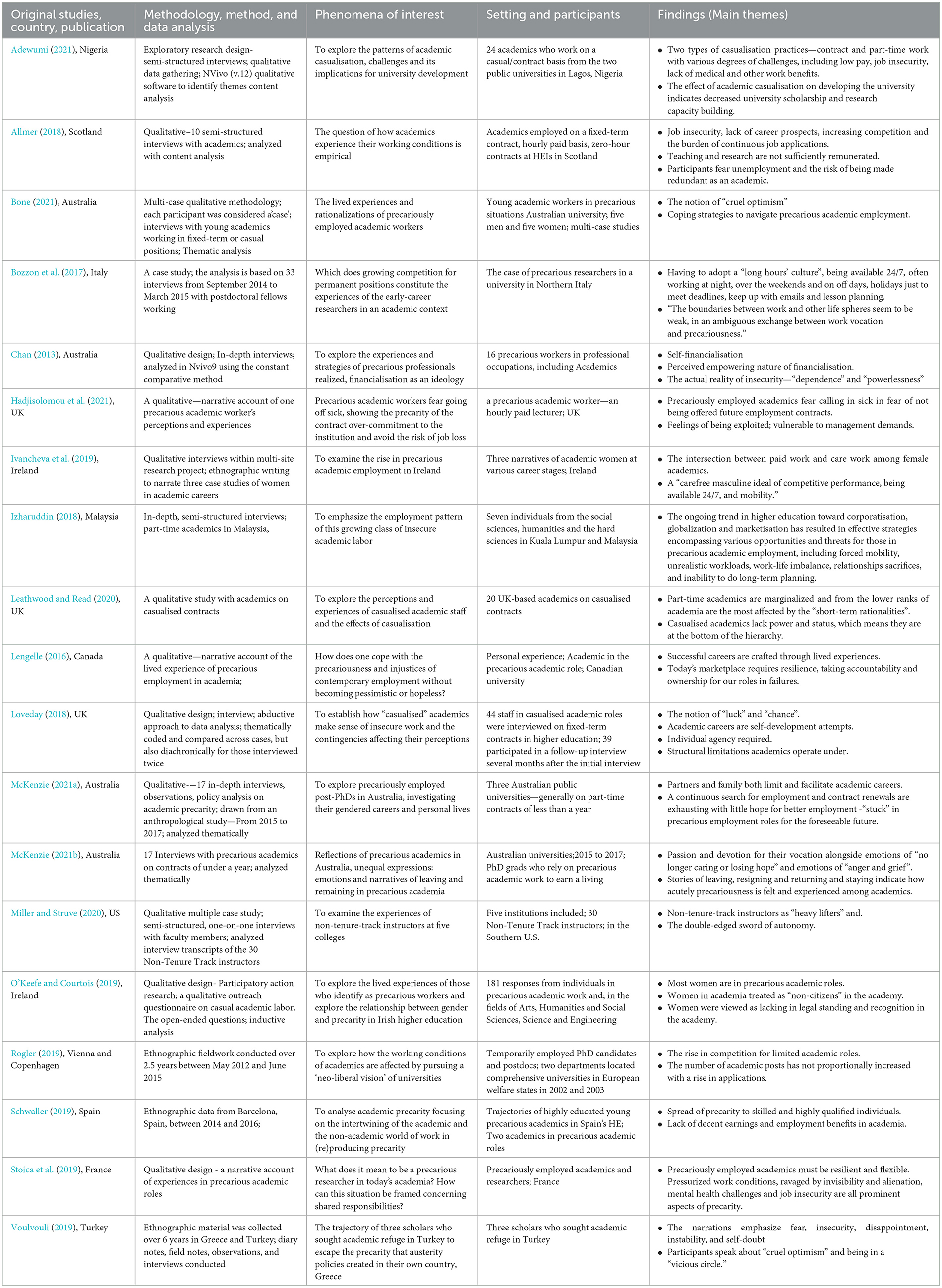

Data were extracted using the JBI-QARI extraction tool from the selected studies. This extraction tool is fairly straightforward and widely used, especially among novice researchers. The data selected for extraction included the references to each primary study, country, phenomena of interest, participants, methodology, setting, and main findings (Table 2). Standardized data extraction forms were used in Microsoft Excel™ spreadsheets with clear fields to reduce extraction errors.

2.8. Data synthesis

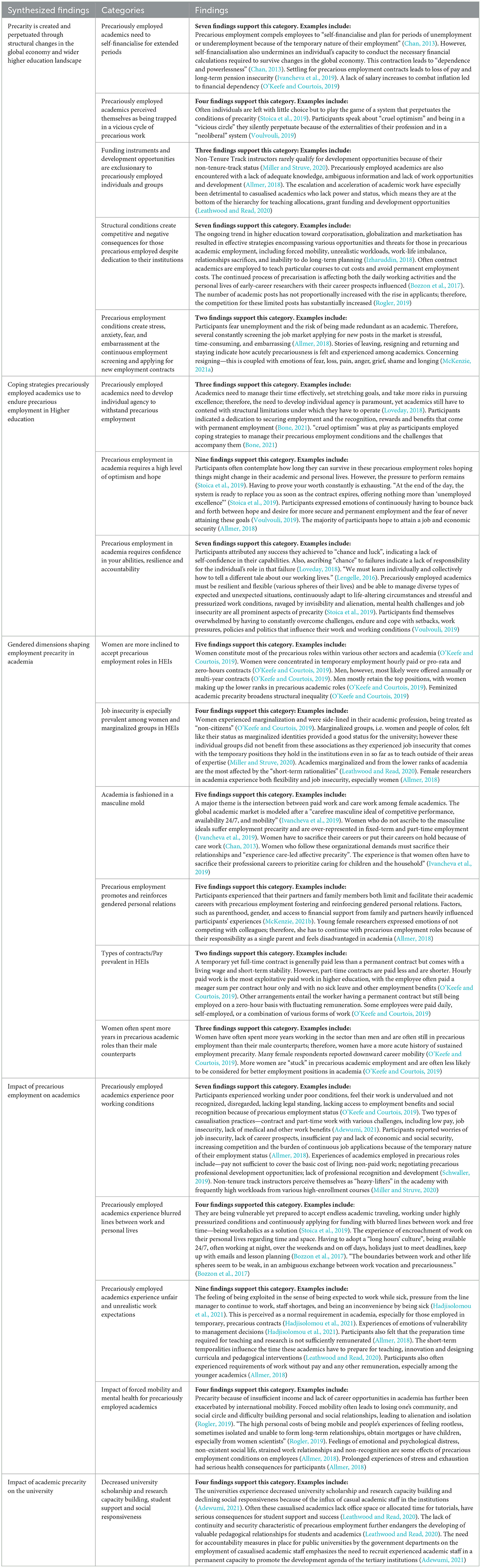

The findings from the selected qualitative studies were collated with meta-aggregation in JBI-QARI. The JBI guidelines describe meta-aggregation as an analytical method for collecting qualitative research findings, classified into similar themes for an improved understanding (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2014). In data extraction, the data were categorized into unequivocal, credible/plausible, and not supported/unsupported data. Unequivocal data were used with direct illustrations selected for the final data analysis. The illustrations were arranged into findings with no further interpretation from the researchers. The study findings were organized and transformed into categories, presenting synthesized findings through meta-aggregation (Lockwood et al., 2015). Table 2 shows the main findings extracted from the primary studies and Table 3 illustrate how the main findings were synthesized through the process of meta-aggregation.

Table 3. Synthesized findings, illustrated as synthesized categories, underlying categories and findings, and supporting each category.

Ninety-four findings were divided into 19 categories, followed by five synthesized findings: (1) Precarity is created and perpetuated through structural changes in the global economy and wider higher education landscape; (2) Coping strategies precariously employed academics apply to endure precarious employment in higher education; (3) Gendered dimensions shaping employment precarity in academia; (4) Impact of precarious employment on academics; (5) Impact of academic precarity on the university (Table 3).

2.9. Ethical considerations

This synthesis employed published primary research findings in the public domain, freely available or subscription to researchers and research institutions. The primary researcher received ethical approval from the research institution (HSSREC Reference Number: HS21/5/32).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the studies

This section offers a summary of the pertinent characteristics of the primary studies forming this review (detailed information can be found in Table 2). The nineteen primary studies were conducted in Australia, the United Kingdom, Ireland, the United States of America, Nigeria, Spain, Vienna, Copenhagen, Canada, Scotland, France, Turkey, Italy, and Malaysia. The studies employed qualitative methodological approaches, encompassing ethnographic, case study, and phenomenological methods. The primary studies involved employees in precarious academic roles in university institutions from various departments and fields, including Arts, Humanities, Social Sciences, Hard Sciences, Engineering, and Social and Cultural Anthropology.

Academics, course administrators, researchers, research assistants, and academic support roles were among the participants. Participants were employed under precarious conditions in fixed-term contracts, non-tenure instructors, casual academics, temporarily employed PhD candidates and postdoctoral candidates, casual contracts, hourly paid, zero-hour contracts, part-time contracts, and freelance academics.

The data for the primary studies were collected in settings, such as university offices, university rooms, and cafes. Data were collected individually through in-depth interviews, semi-structured interviews, qualitative outreach questionnaires, case studies, diary notes, observations, field notes, and biographical interviews. The data for the primary studies were analyzed using constant comparative methods, abductive approaches, inductive-, content-, and thematic analysis.

3.2. Review findings

3.2.1. Precarity is created and perpetuated through structural changes

The first synthesized finding comprises five categories, with 23 findings. The first category, “Precariously employed academics need to self-financialise for extended periods,” was substantiated by seven findings. Precariously employed academics are often concerned about when and where their next employment will be, complicating planning and managing family responsibilities, leading to financial dependency, and powerlessness (Chan, 2013; Allmer, 2018; O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019; McKenzie, 2021a).

“One participant indicated that it is not a matter of choice but rather the consequences of precarious work that forces people to be financially self-disciplined:

I always have to keep in the back of my mind that I have to keep a certain amount of savings-−3 or 4 weeks' rent or so. I think I have about $2,000 saved. I think that is enough to get me by for 6 weeks or so. That is something that is always there, I could lose my job tomorrow. (Ben)” (Chan, 2013, p. 370)

This strategy of financial self-discipline is not sustainable and even more precarious given the unpredictable and unstable income of these precariously employed individuals. With savings and having a budget becomes difficult when your income is unsure.

“When you are a contractor, you make sure you have a bit of a buffer in the bank and hopefully that gets you on to something else before you run out … because you can lose your buffer! (Nick).” (Chan, 2013, p. 371)

“A female researcher tells me that she could not concentrate on her work anymore due to the insecure job situation. The precarious nature of the job worries her and is constantly in her head:

At the moment it is just the insecurity, the precarious nature … when it gets to next year, what if I don't get anything, it is that worry. Constantly in your head, that worry. (Participant 8)” (Allmer, 2018, p. 388)

“A contract researcher tells me that she feels insecure in terms of not knowing when and where the next contract might come from, not knowing what percentage of full-time equivalent she might be able to secure and not knowing when a particular project might start.” (Allmer, 2018, p. 388)

The second category, “Precariously employed academics perceived themselves being trapped in a vicious cycle of precarious work”, was supported by four findings. Academics had to continuously search for employment provided the temporary nature of their employment contracts. They persistently pursue a career in academia, hoping they will eventually secure permanent employment; having “cruel optimism” and being in a “vicious circle” they silently perpetuate because of structural changes as part of the “neoliberal system” (O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019; Stoica et al., 2019; Voulvouli, 2019; Bone, 2021; McKenzie, 2021a).

“Many interviewees are constantly screening the job market and applying for new jobs. A fellow at a Russell Group University mentions that fixed-term academics like him are constantly looking for something else. ‘The longer we are teaching fellows, the less research output we generate so the harder it is to compete with the people who are outside, who are already in lectureship posts' (Participant 1), he continues. People complain that finding a new job is time- and energy-consuming, tiring and humiliating:

Oh, it is just time wasting. It is tiring. It is … I don't know if I can say, it is humiliating at the same time … And if it is not writing applications for jobs, it is also writing applications for projects and I just want to do something else.” (Participant 6) (Allmer, 2018, p. 388).

Another participant explained:

“So those of us still in the race often come to terms with our precariousness by reasserting it. This has been described by Laurent Berlant as ‘cruel optimism', which she defines as a state in which ‘something you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing.” Reasserting the precarious condition in which we live impedes us from stepping out of this vicious circle. We keep hoping that by doing the same things somehow the results will change. Berlant's description of ‘cruel optimism' reminded me how hard I had to strive to convince my university's Research Unit to approve the rent for my apartment while working in the field.” (Voulvouli, 2019, p. 59)

The third category, “funding instruments and development opportunities are exclusionary to precariously employed individuals and groups”, was substantiated by three findings. Academics in precarious employment roles are often ineligible for professional development opportunities and grant funding because they lack power and status. This deficiency positions them at the bottom of the hierarchy for funding and development opportunities (Allmer, 2018; Leathwood and Read, 2020; Miller and Struve, 2020).

“Although NTT instructors were interested in pursuing professional development opportunities, many did not have access to or the bandwidth participate in pedagogical or community-building offerings.” (Miller and Struve, 2020, p. 444)

“Eleanor, a part-time instructor, explained:

I see emails here and there about diversity training being offered to faculty, but I have not participated, and whether or not they may be just as open to adjunct staff, but it's something that I just haven't been immersed in, or taken advantage of on my part, or “been explicitly sort of encouraged or directed that way.” (Miller and Struve, 2020, p. 446)

“Trudy also noted, “I don't get things that other faculty get. I don't get sabbaticals. I don't get funding for travel, and it's because I'm not tenure track.” These comments indicate that NTT instructors were highly aware of status differentials among faculty members.” (Miller and Struve, 2020, p. 446)

The fourth category, “structural conditions create competitive and negative consequences for precariously employed academics despite dedication to their institutions”, was supported by seven findings. The influence of corporatisation, globalization, and universities becoming capitalist-based corporations often leads to cost-cutting measures. These measures include continuously employing academics in temporary capacities, forced to be mobile, having unrealistic work expectations, work-life imbalance, sacrificing relationships, unable to do long-term financial planning, and suffering constant stress and anxiety with little hope for improvement (Bozzon et al., 2017; Izharuddin, 2018; Adewumi, 2021).

“Most of the participants are concerned about the insecure nature of their job and aspire to economic security.

“I really wanted a more secure position', claims Participant 2, ‘I would rather have a permanent position and stop wondering where I will be in 5 years' stresses Participant 6.” (Allmer, 2018, p. 287)

“A postdoctoral researcher emphasizes that her insecure job situation was depressing, making her feel devalued and affected her self-esteem. A female researcher tells me that she could not concentrate on her work anymore due to the insecure job situation. The precarious nature of the job worries her and is constantly in her head:

At the moment it is just the insecurity, the precarious nature … when it gets to next year, what if I don't get anything, it is that worry. Constantly in your head, that worry. (Participant 8) (Allmer, 2018, p. 287)

“Another participant from the Lagos State University added: Of course, one of the most utilized types of academic casualization work is this widely accepted contract work. In this university where I am currently teaching as a casual worker staff, I make bold to tell you that the whole essence why this is happening is because the university is bent on cutting cost. And I do not think this is justified in anyway. I am wondering while PhD holders would be placed on contract rather than being given full type employment. This is not appropriate as most of us only get paid with what the university set as our pay and not in line with the universal public universities payment structure (IDI/P8/2019).” (Adewumi, 2021, p. 18)

The fifth category, “precarious employment conditions create stress, anxiety, fear, and embarrassment”, was substantiated by two findings. Precariously employed academics are forced to compete for limited posts continuously and project funding provided the temporary nature of their employment. This situation is further exacerbated because of underfunded massification in higher education and efforts to limit the duration of studies (Allmer, 2018; Rogler, 2019).

“When I am away… I am more stressed … I think about the job more, like, and I am worried that I am away, it worries me … when I go to the office … I feel better, then when I do not … even if I have taken annual leave. (Participant 10)” (Allmer, 2018, p. 289)

Fear and risk of unemployment force temporary academics to continue to screen the job market for their next employment opportunities, which is stressful and time-consuming; precariousness is acutely experienced among academics contemplating departing academia with emotions of fear, loss, pain, shame, anger, grief while desiring stability, and security (Allmer, 2018; McKenzie, 2021b).

“Participants mention their fears and worries of being unemployed and the risk of being made redundant as academic. Many interviewees are constantly screening the job market and applying for new jobs. A fellow at a Russell Group University mentions that fixed-term academics like him are constantly looking for something else. ‘The longer we are teaching fellows, the less research output we generate so the harder it is to compete with the people who are outside, who are already in lectureship posts' (Participant 1), he continues. People complain that finding a new job is time- and energy-consuming, tiring and humiliating:

Oh it is just time wasting. It is tiring. It is … I don't know if I can say, it is humiliating at the same time … And if it is not writing applications for jobs, it is also writing applications for projects and I just want to do something else. (Participant 6)” (Allmer, 2018, p. 288)

“if I think back over the last year I would say some of the times when I have been the most anxious would have been related to employment” (Max1). (Bone, 2021, p. 283)

3.2.2. Coping strategies to endure precarious employment in higher education

The second synthesized finding includes three categories. The first category, “precariously employed academics need to develop individual agency to withstand precarious employment”, was substantiated by two findings. Precariously employed academics need to manage their time effectively, take more risks, set goals, and pursue excellence. The need to develop individual agency is, therefore, paramount; however, academics are constrained by structural limitations in the institution (Loveday, 2018; Bone, 2021). Given the structural limitations and the fact that university institutions largely benefit from utilizing contract academic staff, it would only be fair to offer these precariously employed individuals the necessary support to combat the adverse effects of their insecure employment. This is where the University human resource management and staff development should look at offering assistance to precariously employment staff to improve their working conditions and the negative effects of precarious employment as well as prioritize the professional development of these precarious/contract staff who carry out core university functions. This should form part of the recruitment and retention strategy of universities.

“…it is really unclear to me where I will be and what I will be doing in 5 years… sometimes I find that really comforting because it means that I can just do what I am doing now without being stressed about where it is getting me and I do find that a source of comfort… But it makes me nervous as well because, you know, I think there are plenty of people who have very clear plans and talking to them makes me nervous because I have a lot of friends who are finishing PhD's who are ‘you have to do this, you have to have done this by this time, you have to have”… (Bone, 2021, p. 283)

“A young researcher tells me that speaking to other precariously employed academics helps to understand patterns of anxieties. She feels it might be better to organize those who are in similar situations and take some agency, instead of feeling alone and powerless:

There is an awareness that there is loads of us in the same position which is the only comfort about it. I think it does get to the point where you just have to take some agency … Maybe we should try and use that, the people who are in a similar position to me, we should actually … rather than just feeling like we are alone, we should do something about that, instead of just waiting about. (Participant 8)” (Allmer, 2018, p. 389)

The second category, “precarious employment in academia requires a high level of optimism and hope”, is supported by ten findings. Precariously employed academics used coping strategies to manage their conditions and overcome challenges. They often contemplate the persistence of these conditions and survival, hoping their conditions will improve; they are continuously putting their life on hold, constantly attempting to prove their worth is “exhausting”; most stay passionate about their work and hope for better positions, continuously bouncing back and forth between hope and desire for secure and permanent employment (Allmer, 2018; Stoica et al., 2019; Voulvouli, 2019; Bone, 2021; McKenzie, 2021b).

“I would kind of hope that the shorter-term stuff would give me a better chance of getting the longer-term stuff but I don't know that for sure. I really don't know how long I could stand it. Hopefully as long as I need to (Mia3).” (Bone, 2021, p. 282)

“I'd be better off trying something else, trying a field where I actually can grow and develop more and get recognition for that whereas I don't feel like that exists within higher education so much” (Max3) (Bone, 2021, p. 285)

“At the end of the day, the system is ready to replace you as soon as the contract expires, offering nothing more than ‘unemployed excellence'.” (Stoica et al., 2019, p. 80)

The third category, “precarious employment in academia requires confidence in your abilities, resilience and accountability”, is substantiated by seven findings. Any success or failures precariously employed academics achieved were attributed to luck and chance. This aspect indicates a lack of responsibility for the individual in success or failure; working in academia requires resilience, flexibility, managing various types of expected and unexpected situations, holding oneself accountable, and taking responsibility for one's choices (Lengelle, 2016; Loveday, 2018; Stoica et al., 2019; Voulvouli, 2019).

“The possibilities of academia are enticing, and this helped to maintain participant commitment. Jasmine, for example, employed a similar strategy by rationalizing her actions as part of building her experience and reputation. However, while relatively optimistic that her actions and dedication would pay-off, Jasmine feared that her efforts would not “translate” into anything more permanent in the future (Jasmine3). Jasmine described her adopted “CV build” strategy in each of her interviews, but in her final interview Jasmine appeared as perplexed as ever about how to get a permanent job:

I am hoping that that will help. There is still that question of how you actually get the jobs, I haven't worked that one out yet. Because it does make you think about, not only what you are doing and what you are putting into the job but that reassessing kind of thing: Am I really, is it worth what I am doing, you know? (Jasmine3)” (Bone, 2021, p. 285)

“Another hourly paid woman says:

One loses a sense of value of their work and what they are doing. Colleagues do not feel the need to greet you as you do not have a vote at School level, and I could go on. (Female, 42, hourly paid).” (O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019, p. 4 71)

3.2.3. Gendered dimensions shaping employment precarity in academia

The third synthesized finding comprises five categories. Nine findings supported the first category, “job insecurity is especially prevalent among women and marginalized groups and accepting of precarious employment roles in HEIs”. Women constitute most precariously employed roles in academia and various other sectors. Women are especially concentrated in the temporary, hourly paid, or pro-rata and zero-hours contracts; being side-lined, overlooked and settling for precarious employment contracts often leads to loss of income and long-term pension insecurity; academic precarity is being feminized, which broadens structural inequality (Allmer, 2018; Ivancheva et al., 2019; O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019; Leathwood and Read, 2020; Miller and Struve, 2020).

“Lack of workplace supports was noted by a number of our respondents as they indicated this contributed to their sense of being exploited. One woman wrote:

There is a huge imbalance between the continuous service I provide for the institution and the absolute lack of any support/security provided for me as an employee in return (Female, 36, hourly paid).” (O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019, p. 470)

“Another woman explains:

It's not just about money. It's about treating hourly paid workers as colleagues, providing support, including them in meetings, treating them with respect (Female, 31, hourly paid).” (O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019, p. 471)

Five findings supported the second category, “academia is fashioned in a masculine mold”. Academia is modeled after a “carefree masculine ideal” of competitive performance, 24/7-h availability, and mobility; women have to manage paid work with care work and family and child care responsibilities and cannot compete with the “masculine ideal”, leading to women sacrificing or putting their careers on hold because of care work; women are over-represented in fixed-term and part-time employment arrangements (Chan, 2013; Ivancheva et al., 2019).

“Fourthly, women report being forced to delay having children or that being pregnant acted as a barrier to securing steady employment. Two women, both hourly paid:

The guys are all pro-rata. Now I'm pregnant, and they have decided to advertise my position. I have been told I have no entitlement to renewed hours next year. I know I will do the interview with a big bump and receive a “we regret to inform you”… I will be unsuccessful in alleging discrimination as they can just appoint someone with the same qualifications as me. Even if I was successful in taking a case the most I can get is 2 years wages, which won't keep me going very long, and I will never work there again. It is worth it? (Female, 33, hourly paid)” (O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019, p. 474)

“I am embarking (finally) on having a family. I know this will dramatically restrict my already low chances of getting anywhere soon … I am worried about how I will survive (Female, 43, mixed casual—part-time permanent and hourly paid)” (O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019, p. 474)

“I don't have children. I'm thirty-five now. We would like to have kids, but we both feel that we shouldn't have children until I have some security. It's not even the money. It's the time, the moving around. I couldn't leave a baby and live in another city or country … Colleagues of mine were asked at interview boards if they planned to have children … [They] stopped wearing their wedding rings.” (Ivancheva et al., 2019, p. 456)

The third category, “precarious employment promotes and reinforces gendered personal relations”, was substantiated by two findings. Precariously employed academics experience their partners and family limit and facilitate their academic careers with precarious employment, fostering and reinforcing gendered personal relations; parenthood, gender, and access to financial support profoundly influence academics' employment experiences (Allmer, 2018; McKenzie, 2021a).

The fourth category, “types of contracts/pay offered in HEIs”, was supported by two findings. Hourly paid work was observed as the most exploitative paid work in higher education, with employees earning a meager sum per contract hour with no sick leave and other employment benefits (O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019).

“Lecturers, tutors and third level educators on these basic minimal contracts are being taken for a ride. We work for less than minimum wage … We incur none of the basic benefits we should. We can't be sick because we only get paid for when we are present. We don't get maternity leave, compassionate leave or anything else (Female, 30, hourly paid).” (O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019, p. 473)

“Our respondents repeatedly spoke of their economic insecurity with one woman writing she felt ‘underpaid and unappreciated. I currently work 4 jobs to make a living' (Female, 34, hourly paid).” (O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019, p. 474)

Another woman wrote: “At the moment it's just about enough to pay the bills, but I'm never certain from one semester to the next how much work I'll be able to get” (Female, 29, hourly paid) (O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019, p. 474).

This economic insecurity speaks to women's wider precarity in their everyday lives; as illustrated by another respondent's account: “I have sleepless nights trying to figure out how to pay bills; I'm getting into debt and the only option now is to emigrate—again” (Female, 42, hourly paid). (O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019, p. 474)

“One month it would have been… eight lectures, twelve tutorials and fifty essays, paid according to the hourly rate for lectures … Basically it was a zero-hour contract …” (Ivancheva et al., 2019, p. 456)

“I try to remain hopeful that I can obtain funding for research for 1 or 2 years and then maybe get some more funding and then get a permanent job in a university. (Male, 34, hourly paid)”

The fifth category, “women often spent more years in precarious academic roles than their male counterparts”, was substantiated by four findings. Women often spend more years working in academia than men and are often still in precarious employment than their male companions; therefore, women have a more acute history of sustained employment precarity; women are often “stuck” in precarious employment, less inclined to occupy permanent roles than their male counterparts (O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019).

“A female respondent working on a part-time contract offset by social welfare speaks instead of survival. She is forced to commute 2 hours into work and expresses a clear sense of hopelessness and a limited expectation of her career trajectory:

I cannot plan ahead. I do not think I will be able to afford to do this type of work, financially or psychologically, and am looking at other options, which are few in this area and in the current climate … I have been looking for additional part-time work to help financially but am already working full-time in practice. We are encouraged to see this work as an opportunity, but in reality know that there is little hope for more than a 9 month, temporary contract. This is unsustainable. (Female, 27, part-time pro rata).” (O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019, p. 470)

“Another woman report feeling ‘[h]opeless and trapped' (Female, 43, hourly paid). Yet another, also on hourly pay, stated: ‘If I am to have any prospects at all I need to leave academia' (Female, 27, hourly paid). This gendered hope is reflective of the reality of working in the neoliberal university where precarious work becomes a permanent trap rather than a temporary phase.” (O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019, p. 470)

“I have been teaching across modules but never having one on my own. And I have been doing the job of a part-time department coordinator for almost 12 years, coming in two and a half days a week, but I never had a contract. I looked around and realized I had been so stupid—everyone around me was doing a quarter of my work for triple my pay.” (Ivancheva et al., 2019, p. 454)

3.2.4. Impact of precarious employment on academics

The fourth synthesized finding includes four categories. The first category, “precariously employed academics experience poor working conditions”, was derived from seven findings. Academics in precarious employment experienced job insecurity, working under poor conditions, vulnerable to harassment, sensed being undervalued, insufficient income to sustain a living, disregarded, no legal status in the institution, lacking career prospects, lacking access to employment benefits and social recognition, the burden of continued job search because of their precarious employment status (Allmer, 2018; O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019; Schwaller, 2019; Stoica et al., 2019; Miller and Struve, 2020; Adewumi, 2021).

“I have never had a sabbatical, and only took [maternity] leave on my third baby. Baby 1—no leave, afraid I would lose my job, baby 2 worked all my teaching hours in one term before the birth, as I was afraid I would lose my position, only on the third baby was I in a permanent part-time contract and able to take official [maternity] leave … as I am the sole breadwinner, I am afraid to put my head above the parapet (Female, 44, permanent part-time).” (O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019, p. 473)

I feel my work is not valued enough, I feel aggrieved and exploited … I know I do the same work as my full-time colleagues, have similar levels of responsibility etc., yet get paid a fraction of a full-time lecturer's salary. There are a number of very important, and time-consuming, tasks that I do for free on behalf of the Department and School, which should be done by permanent members of staff, but either they don't care (lower level of vested interest in attracting students), or are also stretched too far … All my research I do in my non-existent spare time and without financial support apart from the College travel fund, which means that my typical working week is 60–80 hours … Even so my salary is—with luck, as this year—just about a third of a Postdoc's salary at point 1 of the scale. Needless to say, I am always under pressure to take on extra work, so I spend the summers tour guiding around the country and attending one conference on a self-financed basis, which I can't really afford, instead of doing research and getting a much-needed break … My chances of getting permanency or even a full-time job at (institution)? Zilch (Female, 43, mixed casual—part-time permanent and hourly paid).” (O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019, p. 472)

“As contract academics, we are not being treated as humans, even when it is clear that a lot of us are PhD holders for that matter. We are not enlisted for any health or medical allowance in case we fall ill. So you can see that the conditions of this work is so terrible. Talking about what we are paid as casual academics, I can boldly tell you that this pay does not only fall short of the input we put to work, but one that belittle our academic qualifications. We are only put on what is conventionally called “pay-as-you-go” as our salary does not reflect any salary structure in the country (IDI/P4/2019).” (Adewumi, 2021, p. 20)

“You see as casual academics, you cannot be talking of any compensation in this university and this is wrong because the law is clear on this. If you make any attempt to say you want to protest for your rights, you will be thrown out immediately. I have seen cases where my colleague was involved in an accident while commuting down to teach classes and the university say they cannot offer him any medical treatment not to talk of any compensation. So the conditions of this work is that you are not entitled to anything in terms of health, unlike the permanent academic staff who have access to the school clinic including their dependents (IDI/10/2019).” (Adewumi, 2021, p. 20)

The second category, “precariously employed academics experience blurred lines between work and personal lives”, was supported by four findings. Those in precarious academic roles often have to adopt a “long hours culture”, being available 24/7, working at night, over the weekends and on off days and holidays to meet deadlines and to keep up with the heavy workload; not having fixed working hours forces individuals to work without disconnecting from work and having a balanced lifestyle (Bozzon et al., 2017; Hadjisolomou et al., 2021).

“The encroachment of work on the private/personal sphere in terms of times and space:

But I also worked at home, so I worked some times in the morning, I worked at weekends… so it was pretty flexible, but still I worked a fair amount and I was always there [at the workplace] on most days. Some days I worked at home maybe.” (Ex-postdoc STEM, Woman, 34)” (Bozzon et al., 2017, p. 341)

“The downside of working at university is that there are no fixed working hours. This makes people feel forced to work around the clock, without ever disconnecting (Ex-postdoc STEM, Woman, 35).” (Bozzon et al., 2017, p. 341)

“When I don't have to work during the weekends and the evenings this will be a novelty (Current postdoc SSH, Man, 40).” (Bozzon et al., 2017, p. 341)

“Always. I worked at Easter, Christmas…it makes me laugh because it's like a collective disease in this environment (Ex-postdoc SSH, Woman, 36).” (Bozzon et al., 2017, p. 342)

“I am a single mum … I don't feel like I can be as competitive as other people … I do feel at a disadvantage. … It feels like you are really restricted in what you can do … As well it is that insecurity, it is just like a vicious circle because you are having to keep on these short insecure contracts, because you can't compete on a level to get something permanent. It is … it perpetuates (Participant 8).” (Allmer, 2018, p. 390)

The third category, “precariously employed academics experience unfair and unrealistic work expectations”, was substantiated by nine findings. In academia among precariously employed academics is the expectation to work while unwell; vulnerable to management decisions; preparation time for teaching and learning insufficiently remunerated; often working without pay and other benefits, especially among the younger early-career academics; the expectation of maintaining professional development yet not be eligible for development funding and research activities because of continuously searching and applying for new contracts and employment (Allmer, 2018; Leathwood and Read, 2020; Miller and Struve, 2020; Hadjisolomou et al., 2021).

“So that is really difficult because I am kind of caught in the funny cycle, because I have my job to maintain … just to buy food, because I can't stop eating over the summer holidays. So I need to have some kind of job to have an income, but that doesn't allow me to have the time to write articles, get published, to do these kind of things (Participant 3).” (Allmer, 2018, p. 391)

“I started worrying about my health as I had taught many of those students in the preceding weeks. I was terrified and surprised by the University's decision to continue with the blended teaching strategy, ignoring the ineffectiveness of the measures to stop the spread of the virus on the campus. I continued coming in to work. I could, by law, refuse to do so on the grounds that this puts my health at risk. However, when you are working on an hourly paid or temporary contract the reality is that the employment regime of academia does not allow you to refuse work as teaching hours are pre-defined. It is a very competitive sector for us (casual workers). It can be a case of one day you are in and the next day you are out. I did not want to be the troublemaker and the rebel here. It would be too risky for my employment status and job security. Thus, I continued delivering my face-to-face classes as directed by the University.” (Hadjisolomou et al., 2021, p. 8)

The fourth category, “impact of forced mobility and mental health for precariously employed academics”, was derived from four findings. Forced mobility often leads to an individual losing community, social circle, difficulty building personal relationships, inability to make long-term commitments or start a family leading to isolation, alienation, and emotional and psychological distress (Allmer, 2018; Rogler, 2019).

“Now I have to face a new change in my life and I am forced to leave my country and start all over again: new job, new friends, new everything. At 36 years old maybe I would prefer not to do so. If I had the chance I would be very happy to live here, but since I haven't had this chance…we'll leave and go to England. (Ex-postdoc STEM, Woman, 36)” (Bozzon et al., 2017, p. 342).

3.2.5. Impact of academic precarity on the university

The fifth synthesized finding is based on one category, “decreased university scholarship, research capacity, student support and social responsiveness”, supported by four findings. Universities experienced a decline in university scholarship, research capacity building, and social responsiveness because of the influx of casual academic staff in the institution. These academics lack office space and time to dedicate to student support; a lack of employment continuity and academic support further weakens the developing of sustained pedagogical relationships between students and academics; accountability measures are needed for public universities to ensure proper recruitment of experienced academic staff are employed in a permanent capacity to promote the development agenda of higher education (Leathwood and Read, 2020; Adewumi, 2021).

“It is sad that the university has taken a leap from corporate establishments whose goal is profit-driven rather than knowledge and solution-driven. The way we are employed and laid off is so embarrassing I must say. The way academics are retrenched is so draining and extremely difficult, especially for people with families to cater for. I mean, how can someone with higher qualifications like a PhD be treated in this manner? (IDI/13/2019).” (Adewumi, 2021, p. 22)

“It is not farfetched to link the influx of casual academics, whose responsibilities as academics do not include conducting research, to the dwindling research capacity and development of Nigerian universities (IDI/13/2019).” (Adewumi, 2021, p. 22)

“I am of the opinion that the research development of universities in Nigeria is losing its prominence. This is obvious since the large part of universities workforce are now recruited on casual basis and these people are relived from research activities. There is no way this will not affect the development agenda of universities; I have to be honest with you. I mean how do you explain a cohort of academics who only teach and not research to contribute to the research capacity and development of universities. So for me, the longer this academic casualization practice linger, the longer the development of universities will continue to wane (IDI/17/2019).” (Adewumi, 2021, p. 22)

4. Discussion and recommendations

This systematic qualitative review synthesizes the experiences of academics in precariously employed academic roles in HEIs into five findings. The review centers on studies published between 2010 and 2021, meeting the inclusion criteria. The findings indicate that precarity is created and perpetuated through structural changes in the global economy and the wider higher education global landscape. Global forces are changing the landscape and purpose of higher education globally (Blackham, 2020). Universities are increasingly managed with a neoliberal ideology, translating to corporate cost-cutting and commercializing universities (Blackham, 2020). These changes have benefitted university institutions at the expense of the employees. Precariously employed staff often bare the worse of these structural changes and university management models. A recommendation would be for university management should reassess their employment practices and the impact on the staff. Human resource management has to proactively look at measures to combat the adverse effects of temporary employment contracts and the impact on the wellbeing of staff that is excluded from employment-related benefits.

Widespread labor market trends caused changes in neoliberal capitalism, historically leading to a rise in casualisation, devaluation, and feminisation of care work (Boris and Klein, 2012). This led to the growing practice of employing temporary and part-time academics to conduct core university activities to save on permanent employment costs (Greenaway and Haynes, 2003; Blackham, 2020). The effect of precarious academic employment is evident on the employee and the institution. Universities are saving on costs consequently precariously employed academics are having to pay the price for university employment practices. Why is it that universities are progressively moving to casualisation of academic staff without taking into account the impact on employees?

The findings also emphasize the need for individuals to develop coping strategies to endure precarious employment in higher education. To survive the temporary, unstable, and insecure employment conditions, individuals must develop agency, resilience, accountability, confidence, and optimism to withstand and (hopefully) thrive in uncertain and unpredictable employment conditions (Lengelle, 2016; Allmer, 2018; Loveday, 2018; Stoica et al., 2019; Voulvouli, 2019; Bone, 2021; McKenzie, 2021b).

Resilience could aid the individual in their struggle with precarious employment; however, this could lead to a lack of solidarity among colleagues and peers, disregarding the structural precarity dimensions (Stoica et al., 2019). Pedersen et al. (2003) established that insecurity is linked to uncertain work continuity, lack of autonomy over tasks, the strain of being available 24/7, income insecurity, and the effects of unequal treatment. Compared to permanent employees, this poses a significant stressor in the lives of precarious employees.

Building the capacities to withstand these conditions and effects could aid in combating possible harm caused. Malenfant (2007) explored the effect of insecure employment on employees' wellbeing. The author illustrated the adverse influence of intermittent work and the association between insecurity and continuous job searching on employees' mental health. Ill health is associated with employment-related stress, a lack of access to employee medical benefits, and employees constantly forcing themselves to obtain and sustain employment (Clarke et al., 2007). Forms of employment that deviate from the standard benefits and protection offered in typical employment are harmful to people's health and wellbeing (Matilla-Santander et al., 2021). Precariousness was linked to poor mental and physical health (Julià et al., 2017).

What is the role and responsibility of the employer (University) in this employment relationship and how can they be held accountable for the employment conditions they create? This is perhaps an opportunity for Human Resource practitioners to formulate initiatives that are geared toward the needs of precariously employed academics. For example, having career development and career pathing available to temporary and contract staff allowing them to advance their qualifications, skills, expertise and overall career prospects.

The findings further displayed the gendered dimensions shaping employment precarity in academia. Women and other marginalized groups were more willing to accept temporary/part-time employment, indicating more perseverance in securing permanent employment (Ivancheva et al., 2019; O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019). Precariousness proved to be socially distributed with a disproportionate effect on groups employed in precarious, vulnerable employment. These groups include the youth, women, foreign nationals, and individuals from lower socio-economic conditions, leading to critical health implications (Julià et al., 2017).

According to Arat-Koc (1997) and Bakan and Stasiulus (1997), women, immigrants, and people of color continue to occupy more precarious employment roles in the labor market. Cranford et al. (2003) established an over-representation of women in precarious employment, fashioned by constant gender inequalities in households. This leads to women holding more responsibilities for unpaid care work compared to their male counterparts. The academic culture appears more favorable to men with no care and family responsibilities. They have the time to build publication records and bolster their résumés for career promotional activities (Chan, 2013; Ivancheva et al., 2019; McKenzie, 2021b).

Research verifies that men mostly engage in precarious employment to pursue further education and professional development. Few men make the trade-off between part-time work to caregiving work. Conversely, women mostly engage in temporary and part-time work to balance and organize caregiving and family responsibilities (Women in Canada, 2001; Vosko, 2002).

Stone and Lovejoy (2004) established that highly driven female career academics exited the labor force; two-thirds confirmed a lack of support from their husbands in household care responsibilities. When women start a family, they encounter the “maternal wall” leading to sacrificing their career advancement (Correll et al., 2007). Female academics experience career sacrifices for successive childbirths and other career-related responsibilities (Mason et al., 2013).

How can universities respond to these challenges experienced by women in precarious academic roles? Historically, marginalized groups have always endured these challenges why are knowledge and solution-driven institutions not rising to eradicate and minimize the effects of these conditions instead of perpetuating them? Universities could offer funding opportunities to minority groups and other marginalized individuals to begin to readdress the inequalities and marginalization experienced by temporary and contract staff. Universities could reassess their policies on promotion criteria, to not unfairly discriminate and or exclude women who could not advance their publication record or qualification due to household care and family responsibilities.

The findings emphasize the stark working conditions and influence of precarious employment on academics. The conditions reported ranged from: undervalued, underpaid, insufficient income, job insecurity, a lack of recognition, a lack of access to employment benefits, vulnerable to harassment, exploitation, a lack of legal standing, a lack of autonomy, a lack of control, unrealistic workloads, stress and anxiety, and a lack of development opportunities (Bozzon et al., 2017; Allmer, 2018; O'Keefe and Courtois, 2019; Rogler, 2019; Schwaller, 2019; Stoica et al., 2019; Miller and Struve, 2020; Adewumi, 2021; Hadjisolomou et al., 2021).

Precarious employment is observed as a social determinant of health. Employment conditions affect employees, their families, and the community's health (Benach et al., 2014). Empirical exploration into job insecurity consistently indicates a link between mental ill-health and perceived job loss/insecure employment (De Witte, 1999; Sverke et al., 2002; Ferrie et al., 2008). Studies established that fixed-term contracts have adverse effects on the health outcomes of employees concerning burnout, occupational injuries, mental health issues, increase in sickness absence (Joyce et al., 2010). University policies could be redesigned to include temporary and contract staff in receiving medical and health benefits to assist employees to manage their health and wellbeing.

The findings referenced the influence of academic precarity on university institutions. The influence of continued employment in temporary and part-time capacities decreases university scholarship, research capacity building, student support, and the ability to be socially responsive (Leathwood and Read, 2020; Adewumi, 2021). For universities in developing countries, these factors are aspirational goals in readdressing past inequalities (Adewumi, 2021).

5. Limitations

This review only included studies reported in English—studies reporting in other languages were excluded. The restriction on other languages could lead to disregarded research. An effort was made to identify related research studies, and systematic screening and search; however, some studies could have been overlooked. This review included studies published between 2010 to 2021. Future reviews could include a dissimilar timeline to create further understanding of the experiences of precariously employed academics in HEIs. The findings emphasized in this review were mainly conducted in the Northern hemisphere, with only one study being conducted in an African context. Future reviews and studies could approach this divergence in the literature to emphasize the experiences of precariously employed academics in African HEIs.

6. Conclusions

The findings of this review present a stark overview of the experiences of academics in precarious employment positions in HEIs. Most of the findings are based on HEIs in developed economies and mostly in the Northern hemisphere. Dominant themes from the findings emphasize employees' desire and hope for more secure and permanent employment. Several of these precariously employed academics felt overwhelmed, vulnerable, exploited, stressed, anxious, and exhausted with their employment conditions. They operate in unstable and insecure positions with no guarantees of secure or permanent employment. Several must contend with the structural implications of neoliberal systems that universities operate under. The collective experience is mutual among several participants in the included studies. The human resource department and university management must critically assess how their policies and practices influence this category of employees to combat the adverse effects of continued job insecurity and employment instability.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SS and MD both contributed to the review article and approved the submitted version. All authors were responsible for writing and approving this article.

Funding

Funding were provided by the New Generation of Academics Programme (nGAP)—offered by the Department of Higher Education and Training.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adewumi, S. A. (2021). Academic casualization and university development in a selected public higher institution in lagos, nigeria samson adeoluwa adewumi elsabe keyser. Afr. J. Develop. Stud. 11, 7–29. doi: 10.31920/2634-3649/2021/v11n2a1

Allan, B. A., Autin, K. L., and Wilkins-Yel, K. G. (2021). Precarious work in the 21st century: A psychological perspective. J. Vocat. Behav. 126, 103491. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103491

Allan, B. A., Tay, L., and Sterling, H. M. (2017). Construction and validation of the Subjective Underemployment Scales (SUS). J. Vocat. Behav. 99, 93–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.01.001

Allmer, T. (2018). Precarious, always-on and flexible: A case study of academics as information workers. European J. Communication 33, 381–395. doi: 10.1177/0267323118783794

Arat-Koc, S. (1997). “From ‘Mothers of the Nation' to Migrant Workers,” in Not One of the Family, A. Bakan and D. Stasilus (Toronto: University of Toronto Press) 53. doi: 10.3138/9781442677944-005

Bakan, A., and Stasiulus, D. (1997). “Making the Match: Domestic Placement Agencies and the Racialization of Women's Household Work.” Signs, 20, 303. doi: 10.1086/494976

Bearman, M., and Dawson, P. (2013). Qualitative synthesis and systematic review in health professions education. Med. Educ. 47, 252–260. doi: 10.1111/medu.12092

Benach J, Vives A, Amable M, Vanroelen C, Tarafa G, and Muntaner C. Precarious employment: understanding an emerging social determinant of health. Annu Rev Public Health. (2014) 35:229–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182500.

Blackham, A. (2020). Unpacking precarious academic work in legal education. Law Teacher 54, 426–442. doi: 10.1080/03069400.2020.1714276

Blustein, D. L., Olle, C., Connors-Kellgren, A., and Diamonti, A. J. (2016). Decent work: A psychological perspective. Front. Psychol. 7, 1–10. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00407

Bone, K. D. (2021). Cruel optimism and precarious employment: the crisis ordinariness of academic work. J. Business Eth. 174, 275–290. doi: 10.1007/s10551-020-04605-2

Boris, E., and Klein, J. (2012). Caring for America: Home Health Workers in the Shadow of the Welfare State. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195329117.001.0001

Bozzon, R., Murgia, A., Poggio, B., and Rapetti, E. (2017). Work–life interferences in the early stages of academic careers: The case of precarious researchers in Italy. European Educational Research Journal 16, 332–351. doi: 10.1177/1474904116669364

Chan, S. (2013). “I am King”: Financialisation and the paradox of precarious work. Economic and Labour Relations Review 24, 362–379. doi: 10.1177/1035304613495622

Clarke, M., Lewchuk, W., de Wolff, A., and King, A. (2007). “This just isn't sustainable”: Precarious employment, stress and workers' health. Int. J. Law Psychiatry, 30, 311–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2007.06.005

Correll, S. J., Benard, S., and Paik, I. (2007). Getting a job: is there a motherhood penalty? Am. J. Sociol. 112, 1297–1338. doi: 10.1086/511799

Cranford, C. J., Vosko, L. F., and Zukewich, N. (2003). Precarious employment in the Canadian labour market: A statistical portrait. Just Labour. 3, 6–22. doi: 10.25071/1705-1436.164

De Cuyper, N., Notelaers, G., and De Witte, H. (2009). Job Insecurity and Employability in Fixed-Term Contractors, Agency Workers, and Permanent Workers: Associations with Job Satisfaction and Affective Organizational Commitment. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 14, 193–205. doi: 10.1037/a0014603

De Witte, H. (1999). Job insecurity and psychological well-being: review of the literature and exploration of some unresolved issues. Eur. J. Work Organis. Psychol. 8, 155–177. doi: 10.1080/135943299398302

Ferrie, J. E., Westerlund, H., Virtanen, M., Vahtera, J., and Kivimaki, M. (2008). Flexible labor markets and employee health. Scand. J. Work, Environ. Heath 2008, 98–110. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.278

Greenaway, D., and Haynes, M. (2003). Funding higher education in the UK: The role of fees and loans. Econ. J. 113, 485. doi: 10.1111/1468-0297.00102

Hadjisolomou, A., Mitsakis, F., and Gary, S. (2021). Too Scared to Go Sick: Precarious Academic Work and ‘Presenteeism Culture' in the UK Higher Education Sector During the Covid-19 Pandemic. Work, Employ. Soc. 36, 501. doi: 10.1177/09500170211050501

Ivancheva, M., Lynch, K., and Keating, K. (2019). Precarity, gender and care in the neoliberal academy. Gender, Work Organiz. 26, 448–462. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12350

Izharuddin, A. (2018). Precarious intellectuals: The freelance academic in Malaysian higher education. Kajian Malaysia 36, 1–20. doi: 10.21315/km2018.36.2.1

Joanna Briggs Institute. (2014). The Joanna Briggs Institute: The Systematic Review of Economic Evaluation Evidence. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers' Manual. p. 1–40. Available online at: https://nursing.lsuhsc.edu/JBI/docs/ReviewersManuals/Economic.pdf (accessed September 10, 2021).

Joyce, K., Pabayo, R., Critchley, J. A., and Bambra, C. (2010). Flexible working conditions and their effects on employee health and well-being. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, CD008009. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008009.pub2

Julià, M., Vanroelen, C., Bosmans, K., Van Aerden, K., and Benach, J. (2017). Precarious employment and quality of employment in relation to health and well-being in Europe. Int. J. Health Serv. 47, 389–409. doi: 10.1177/0020731417707491

Kalleberg, A. L. (2000). Part-time, temporary and contract work. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 26, 341–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.341

Katz, L. F., and Krueger, A. B. (2019). The rise and nature of alternative work arrangements in the United States, 1995–2015. ILR Rev. 72, 382–416. doi: 10.1177/0019793918820008

Leathwood, C., and Read, B. (2020). Short-term, short-changed? A temporal perspective on the implications of academic casualisation for teaching in higher education. Teach. Higher Educ. 27, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2020.1742681

Lengelle, R. (2016). Perspectives in HRD: Narrative Self-rescue: A Poetic Response to a Precarious Labour Crisis. New Horizpns Adult Educ. Human Resour. Develop. 28, 46–49. doi: 10.1002/nha3.20130

Lockwood, C., Munn, Z., and Porritt, K. (2015). Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 13, 179–87. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000062

Loveday, V. (2018). Luck, chance, and happenstance? Perceptions of success and failure amongst fixed-term academic staff in UK higher education. Br. J. Sociol. 69, 758–775. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12307

Malenfant, R. (2007). Intermittent work and well-being: One foot in the door, one foot out. Curr. Sociol. 55, 1977. doi: 10.1177/0011392107081987

Mason, M. A., Wolfinger, N. H., and Goulden, M. (2013). Do babies matter? Gender and family in the ivory tower. Rutgers University Press.

Matilla-Santander, N., Martín-Sánchez, J. C., González-Marrón, A., Cartanyà-Hueso, À., Lidón-Moyano, C., and Martínez-Sánchez, J. M. (2021). Precarious employment, unemployment and their association with health-related outcomes in 35 European countries: a cross-sectional study. Crit. Public Health 31, 404–415. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2019.1701183

McKenzie, L. (2021a). Un/making academia: gendered precarities and personal lives in universities. Gender Educ. 34, 262–279. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2021.1902482

McKenzie, L. (2021b). Unequal expressions: emotions and narratives of leaving and remaining in precarious academia. Soc. Anthropol. 29, 527–542. doi: 10.1111/1469-8676.13011

Miller, R. A., and Struve, L. E. (2020). “Heavy Lifters of the University”: non-tenure track faculty teaching required diversity courses. Innov. Higher Educ. 45, 437–455. doi: 10.1007/s10755-020-09517-7

Oakley, A. (1995). Public visions, private matters. Professorial inaugural lecture, The Institute of Education.

O'Keefe, T., and Courtois, A. (2019). ‘Not one of the family': Gender and precarious work in the neoliberal university. Gender, Work Organiz. 26, 463–479. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12346

Pearson, A., and Hannes, K. (2012). Obstacles to the Implementation of Evidence-Based Practice in Belgium: A Worked Example of Meta-Aggregation.

Pedersen, H. H., Hansen, C. C., and Mahler, S. (2003). Temporary agency work in the European Union. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

Perry, J. A., Berlingieri, A., and Mirchandani, K. (2020). Precarious work, harassment, and the erosion of employment standards. Qualit. Res. Organiz. Manag. 15, 331–348. doi: 10.1108/QROM-02-2019-1735

Ragins, B. R., and Cornwell, J. M. (2001). Pink triangles: Antecedents and consequences of perceived workplace discrimination against gay and lesbian employees. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 1244–1261. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.6.1244

Reay, D. (2000). “Dim dross”: Marginalised women both inside and outside the academy. Women Stud. Int. Forum 23, 13–21. doi: 10.1016/S0277-5395(99)00092-8

Reay, D. (2004). Cultural capitalists and academic habitus: Classed and gendered labour in UK education. Women Stud. Int. Forum 27, 31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2003.12.006

Rogler, C. R. (2019). Insatiable greed: performance pressure and precarity in the neoliberalised university. Soc. Anthropol. 27, 63–77. doi: 10.1111/1469-8676.12689

Schwaller, C. (2019). Crisis, austerity and the normalisation of precarity in Spain – in academia and beyond. Soc. Anthropol. 27, 33–47. doi: 10.1111/1469-8676.12691

Spreitzer, G. M., Cameron, L., and Garrett, L. (2017). Alternative work arrangements: two images of the new world of work. Ann. Rev. Organiz. Psychol. Organiz. Behav. 4, 473–499. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113332

Sterling, H. M., and Allan, B. A. (2020). Construction and Validation of the Quality of Maternity Leave Scales (QMLS). J. Career Assess. 28, 337–359. doi: 10.1177/1069072719865163

Stoica, G., Eckert, J., Bodirsky, K., and Hirslund, D. V. (2019). Precarity without borders: visions of hope, shared responsibilities and possible responses. Soc. Anthropol. 27, 78–96. doi: 10.1111/1469-8676.12700

Stone, P., and Lovejoy, M. E. G. (2004). Fast-Track Women and the “Choice” to Stay Home. Ann. AAPSS 596, 62–83. doi: 10.1177/0002716204268552

Sverke, M., Hellgren, J., and Naswall, K. (2002). No security: a meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 7, 242–64. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.7.3.242

Tompa, E., Scott-Marshall, H., Dolinschi, R., Trevithick, S., and Bhattacharyya, S. (2007). Precarious employment experiences and their health consequences: Towards a theoretical framework. Work 28, 209–224. doi: 10.3233/wor-2011-1140

Vosko, L. F. (2002). ‘Decent Work': The Shifting Role of the International Labour Organisation and the Struggle for Global Social Justice. London,Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi: SAGE Publications. 19–46. doi: 10.1177/1468018102002001093

Keywords: precarious employment, academics, higher education, academia, contract employment, contract lecturers, precarious work

Citation: Solomon S and Du Plessis M (2023) Experiences of precarious work within higher education institutions: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Front. Educ. 8:960649. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.960649

Received: 03 June 2022; Accepted: 09 May 2023;

Published: 24 May 2023.

Edited by:

Wadim Strielkowski, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, CzechiaReviewed by:

Julie A. Hulme, Keele University, United KingdomElsabe Keyser, North-West University, South Africa

Copyright © 2023 Solomon and Du Plessis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shihaam Solomon, c3NvbG9tb25AdXdjLmFjLnph

Shihaam Solomon

Shihaam Solomon Marieta Du Plessis

Marieta Du Plessis