- 1Emirates College for Advanced Education, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

- 2Khalifa University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

- 3Open Polytechnic, Auckland, New Zealand

- 4Rabdan Academy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

- 5Zayed University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

- 6United Arab Emirates University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Since the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic, early research already indicates that the personal and professional impact on academics juggling parenting responsibilities with their academic work has been immense. This study, set in the United Arab Emirates, explores the experiences of academic parents and looks at ways in which various aspects of their professional lives have been affected by the pandemic. Survey data from 93 participant parents indicated that certain elements of research productivity have been reduced during the pandemic, and having to support children with online schoolwork while teaching online themselves has been particularly stressful. Working from home with no dedicated space was a frequent challenge for the academic parents, and this impacted their ability to perform research tasks that demanded quiet spaces, e.g., reading and writing. However, the data also indicated that parents appreciated greater working flexibility, a reduction in commuting time, and being able to be more involved in their family lives. Some indications were perhaps unexpected, such as no statistically significant impact being observed on academic parents’ ability to interact with students or peers at their institutions while working from home. The implications of these findings to faculty and institutions are discussed.

Introduction

The global COVID-19 pandemic created additional challenges for parents as they attempted to balance working from home with added full-time childcare responsibilities and domestic chores. Research has shown that parents have been less productive than their child-free peers since the start of the pandemic (see, e.g., Myers et al., 2020; Staniscuaski et al., 2021). More specifically, there has been an immense personal and professional impact on academics juggling their parenting responsibilities with their academic work. However, academic parents’ experiences from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) are still missing in the literature. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate how academic parents’ working lives in the UAE were affected during the COVID-19 pandemic by exploring the changes to their working patterns, daily roles and responsibilities, and how this impacted their ability to manage work.

Academic parenthood: literature review

Juggling responsibilities at work and home

Gender disparities were present in the homes of academics well before the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies have repeatedly shown that female academics perform more household labor than men, sometimes to the detriment of their academic work (e.g., Schiebinger et al., 2008; Rafnsdóttir and Heijstra, 2013). Recent research indicates that the pandemic has increased domestic responsibilities for women (e.g., Minello et al., 2021). Bianchi et al. (2012) showed that having young children at home increases housework for both genders, yet increases the housework for females threefold that of males. Furthermore, Suitor et al. (2001) found that female faculty spent 113% more time on childcare than their male counterparts. This is likely to impact the academic’s ability to work quietly on research writing and therefore may impede their research productivity. Fairweather (2002) points out that “each faculty member is expected to be … the complete faculty member – simultaneously productive in both teaching and research” (p. 27). Constantly juggling work responsibilities and family life responsibilities may contribute to a cumulative disadvantage (Bailyn, 2011; Grant and Elizabeth, 2015). Literature strongly indicates that academic parenting struggles can be more significant for mothers than for fathers for a variety of reasons, including practical ones such as pregnancy and maternity leave, but also due to persistent ideas about the caretaking of young children as being a predominantly feminine concern (Fairweather, 2002).

Rosewell (2021) argues that research about the experiences of fathers in the academy continues to lag behind that of mothers; however, it is important to recognize the challenges and barriers faced by all in academia. Academic fathers are unlikely to have their commitment to work questioned in ways that mothers might experience; however, academic parenting appears to present as a barrier to what is referred to as the ‘ideal worker norm’ where there is an expectation of total dedication to the employer. The “bias against active fathering” (Reddick et al., 2011, p. 6) is perceived as ‘choosing’ to be an active father at the expense of one’s career.

However, institutions have expectations of academic fathers who are research productive, and such men can be marginalized if they are unable to fulfil these expectations (Reddick et al., 2011). Since childcare is so deeply associated with females, it can make it challenging for academic fathers to get recognition too (Minnotte, 2020; Nash and Churchill, 2020). Manager bias may make it difficult for fathers to request flexibility, which may have been necessary at times under COVID-19. Like academic mothers, fathers also experience criticism and penalties for family involvement and, at times, have their dedication to academia questioned (Ecklund and Lincoln, 2016; Sallee et al., 2016; Nash and Churchill, 2020).

Academic parenthood and the pandemic: what could be predicted from what is already known?

Given what is already known about academic parenthood and its impact on academic life, it is possible to predict some likely outcomes for academic parents during this time. Literature often indicates that parents have been less productive than their child-free peers during the pandemic as they face the additional challenge of balancing working from home with full-time childcare responsibilities and domestic chores (see, for example, Myers et al., 2020; Staniscuaski et al., 2021). While some research suggests that this trend existed before the pandemic too, other studies contradict this. For example, Krapf et al. (2017) investigated almost 10,000 academic researchers and did not find any correlation between motherhood and reduced research productivity, in general. However, they discovered that becoming a mother before 30 negatively impacts research output. Moreover, Joecks et al.’s (2014) study of 400 business and economics researchers found that female researchers without children were less productive than female researchers with children. So the research around this question is mixed, though more weighted toward an acceptance of the fact that faculty with caring responsibilities have a more challenging time meeting academic expectations.

This has left many academic parents, particularly those with young children, feeling overwhelmed (Fertig, 2020). Given the well-established gender divide in academic parenting (Santos and Cabral-Cardoso, 2008; Schiebinger et al., 2008; Kan et al., 2011; Klein and Myrdal, 2013; Derrick et al., 2019), academic mothers have had to make the most adaptations to their daily lives (see, for example, Andersen et al., 2020; Nash and Churchill, 2020; Minello et al., 2021). These changes to everyday life have affected academic parents’ professional and personal lives, including work priorities, increased childcare requirements, and combining the work/home environment, and they are likely to have long-term consequences.

A study of academic mothers during the lockdown in Italy and the United States found that online teaching was their main working priority, as opposed to other aspects of academic work (Minello et al., 2021). This has encompassed modifying lessons for online learning and the teaching time itself, whether synchronous or asynchronous. Female faculty sometimes tend to have more teaching responsibilities (Viglione, 2020), so it is likely that the finding by Minello et al. (2021) is not uncommon, and the sudden shift to online teaching caused by the pandemic may have affected females, and therefore mothers, disproportionately. Some institutions would already have been using learning platforms prior to the pandemic, but unless they were teaching online, this would have been infrequent or hybrid use, which is quite different from the situation which developed during the pandemic. The focus on teaching during the pandemic often resulted from deliberate institutional decisions and academic policies (Minello et al., 2021), although it is generally seen as a less important element in terms of promotion and tenure, where research is prioritized (Kibbe, 2020).

Domestic responsibilities for women have been increased by the pandemic, in both concrete ways such as supervision and support of children’s home learning, and in more subtle ways such as the emotional work of dealing with children and other family members’ anxieties (e.g., Fertig, 2020; Power, 2020; Minello et al., 2021). With the shutdown of schools and childcare facilities, women have assumed more responsibility for childcare at home than men (Sevilla and Smith, 2020; Viglione, 2020). Other support systems, such as grandparents, have been unavailable in many cases due to inability to travel distances. Juggling these responsibilities simultaneously with working from home has challenged academic mothers.

Research work requires time, silence, concentration, and inspiration, but these conditions are difficult to find where the space for the academic is not separated from the family, making the segregation of the roles of parent and academic more challenging (Nash and Churchill, 2020). Indeed, for most academic mothers, the home represents yet another workplace (Hochschild, 1989).

In a study on productivity among academics during the first 2 months of the COVID-19 lockdown in the U.S., faculty with 0–5 year-old children reported significantly fewer working hours compared to all other groups (these were – no children, children in other age ranges). They also completed significantly less peer review work and submitted fewer articles as first author (Krukowski et al., 2021). Fertig (2020) explains that “while drops in productivity during COVID-19 are gendered, maintaining research productivity in absence of childcare has been untenable for all caregivers” (p. 331). There is already empirical evidence demonstrating parents (and women, in particular) being less ‘research productive’ than men during the pandemic, and there are signs of this disparity across academic disciplines. Women are publishing less than men compared to the same time period in 2019 (Andersen et al., 2020; Oleschuk, 2020; Ribarovska et al., 2021), and female first authorship is also less visible in emerging COVID-19-related literature (Amano-Patiño et al., 2020). A Brazilian study that took place around the same time with 3,345 participants found that parenthood had a significant impact on manuscript submissions, with more childless peers submitting manuscripts than those with children, for both women and men (Staniscuaski et al., 2021). Similarly, a U.S. study (Krukowski et al., 2021) found that female academics’ first- and co-authored article submissions decreased during the pandemic quite significantly. This echoes other findings of reduced numbers of manuscript submissions authored by women during the pandemic, especially where women are the first authors (Andersen et al., 2020; Minello, 2020; Viglione, 2020). We note that other studies have shown gender disparities in publishing or general research productivity prior to the pandemic too (e.g., Mueller et al., 2017), but this is likely to have increased during the pandemic, according to the studies mentioned previously. Where academic parents, specifically, were studied, the age of their children was also associated with productivity; there was a negative association between women with at least one child aged between 1 and 6 years old and the submission of manuscripts (Staniscuaski et al., 2021). However, other academics have suggested that some ‘silver linings’ of the pandemic have been the ability to access research conferences more easily since they are held virtually (Nash and Churchill, 2020), compared to previous situations. This is important, aswWomen are known to often forego networking and research dissemination opportunities that research conferences provide due to childcare considerations and concerns (Dickson, 2019).

These studies into productivity largely reflect research data collected during the first few months of the pandemic. At that time, the pandemic was not predicted to last as long as it has, and people (including academic parents), were doing what they needed to survive, perhaps assuming it was a short-term disruption to their lives. As the pandemic continued, divisions between parents and non-parents may have continued to be exacerbated.

Parents’ experiences during COVID-19 in the Gulf region

Parents in the Arab Gulf region, as was the case with parents internationally (e.g., Brown et al., 2020; Cluver et al., 2020), have experienced major challenges amidst the outbreak of COVID-19 and the enforcement of a series of preventive measures. Coinciding with the shift to remote work, quarantine, and social distancing protective measures, the mode of learning in the Gulf region countries switched to online and, at times, to hybrid learning between March 2020 to October 2021. With education being transferred from schools to homes, parents became tasked with supporting their children through their remote learning experiences. A recurring theme in Said et al.’s (2021) study reflected gender differences in domestic and other duties, as well as in attending to the educational needs of children during COVID-19. Their examination of the gender differences was carried out in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and the disproportionate responsibility placed on mothers as the primary caretakers was consistent amongst participants from different cultural backgrounds. Additional motherly duties expected of mothers included those that pertain to learning from home such as printing resources, setting up timetables, following up on children’s work throughout the school day, and ensuring their children’s well-being during remote study (Said et al., 2021). The burden was heightened due to accompanying circumstances such as work commitments, social distancing, and increased concern for family and loved ones (Saddik et al., 2021). Consequently, academic mothers in the UAE may have shouldered a heavier burden than childless academics and perhaps academic fathers.

In the UAE, moderate to severe anxiety and worry in working females were reported in association with COVID-19 (Saddik et al., 2021). Working mothers spoke of multiple mental health concerns and pressures of time management that negatively affected their work (Said et al., 2021). However, to our knowledge, only two studies have so far investigated the status and experiences of the academic community in a country in the Gulf region. In Kuwait, depression was reported among university students during the pandemic, reportedly with higher incidence rates among females compared to males (Alsairafi et al., 2021). In Saudi Arabia, the academic community reported experiencing acute mental health disorders including anxiety, depression, and insomnia constantly or occasionally (Alfawaz et al., 2021). A detailed picture of the experiences of UAE academics during the current pandemic is as yet missing.

Study purpose

The overarching purpose of this study was to investigate how the working lives of academic parents living in the UAE were affected during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specific aims were to explore the changes to their working patterns, daily roles, and responsibilities, and how this impacted their work and ability to manage work.

Research questions

1. In what ways have academic parents been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in their domestic spheres (e.g., additional responsibilities, changes to working environment, etc.)?

2. How, if at all, have academic parents’ working lives and productivity been affected by these changes to their working environment, including levels of support (e.g., institutionally)?

3. What differences, if any, are observed between female and male academics for the aspects named in RQ 2?

Methodology

The research study utilized a mixed-methods design to benefit from both quantitative and qualitative features. Specifically, having more respondents answer closed-ended questions permits more objective and generalizable conclusions, yet having the human experience expressed through the subjects’ own words allows access to in-depth information to formulate a better understanding of the phenomenon. The research team utilized the literature discussed earlier to self-develop the survey questionnaire. The researchers could not locate appropriate pre-developed tools to adapt, likely due to the UAE’s unique contextual nuances and the pandemic being a relatively recent occurrence with limited publications on the subject at the time of instrument creation.

A survey questionnaire (see Supplementary Appendix) containing 39 questions was produced that included 15 demographic questions relating to gender, nationality, the number and ages of their children, marital status, use of domestic help, etc. The remaining survey questions investigated respondents’ perceptions of how the COVID-19 pandemic affected their work-life balance and work productivity, and their suggestions to help working academic parents alleviate some of the challenges faced. We defined research productivity in the survey items as involvement in the following facets: academic reading, research proposal writing, grant writing, research data collection, manuscript preparation and submission, publication, and research dissemination (e.g., through conferences). The survey mostly contained closed-ended questions (e.g., multiple choice, Likert scale, etc.). However, three open-ended responses were also asked, including how the pandemic affected aspects of home and work life, what institutions could do better to support their faculty during the pandemic, and ways in which life had become easier due to the changes brought on by the pandemic.

Each item, and construct within which the item was positioned, was carefully discussed by the researching team and debated for its relevance and validity. Since we are a team of seven experienced faculty members from across six different UAE institutions, we had strong contextual knowledge within which to base our discussions and to decide upon items to include or exclude in the survey questionnaire. We also carefully assembled the constructs based on key themes arising from the body of research literature which exists on structural and practical barriers faced by academic parents both prior to, and (according to research which was beginning to emerge at the time of writing) during the pandemic. These themes include practical support structures, children’s home learning situations, academic parents’ home working environments, family/spousal/paid help/ institutional support, the benefits of interactions with students and colleagues, research and teaching support, work-home boundaries and work-life balance.

We piloted the survey questionnaire with a small group of faculty parent colleagues and made adjustments to survey items based on their feedback.

Even though instruction in tertiary educational institutions in the UAE is predominantly in English, respondents could take the survey in English or Arabic. This provision was for Arabic faculty members who might have preferred to respond to the survey using their mother tongue. To ensure correct translation, the English survey was translated by a bilingual Research Assistant and then back-translated by Arabic-speaking research team members. Using purposive sampling, the survey was sent to faculty by the Research Office or equivalent at eight tertiary institutions in the UAE after gaining IRB approval at each institution since reciprocal IRB arrangements do not exist in the UAE. The data collection period was from approximately March to June 2021. Our survey response rate was close to 30%, a fairly typical response rate for online survey questionnaires (Nulty, 2008).

Research participants

The target population for this research study was full-time academics working in private or public higher education institutions in the UAE who were parents of at least one child under 18 years old living full-time at home with them during the COVID-19 pandemic. The research sample consisted of 93 academics, 61% female and 39% male, with 82% of the survey respondents being expatriates and 18% UAE nationals. Of the 93 faculty, just over half reported holding an academic administrative role in addition to their faculty role. Eighty-eight percent of the participants had a spouse, but just 56% of them reported having childcare assistance from their spouse. While 62% of the respondents employed domestic help for household chores, only 35% hired childcare. Forty-one percent reported that provision of care for children was undertaken predominantly by the faculty parent themselves, while other care options included: spouses (33%), nannies (21%), and extended families (5%).

Data analysis

The quantitative data were first analyzed descriptively for percentages, means, frequency, and standard deviation. We also explored statistically significant relationships between certain variables, such as the provision of a private closed space to work at home, and outcomes such as the level of challenge in teaching and research productivity in relation to the research questions. Finally, ordered logit regression analyses were carried out for these associations. Inferential statistical tests informed whether significant differences existed between academic parents’ responses, where a variable was being explored, and whether there were significant differences in participant responses pre- and post-pandemic, among other factors. The open-ended questions were analyzed through a phenomenological lens to create themes and sub-themes, primarily based on the conceptual framework whereby information was coded and grouped.

Research ethics

The risk to participants of responding to the anonymous online survey was deemed minimal. However, because of the possible instability, increased stress, and trauma experienced by individuals due to the pandemic, the research team was aware that some respondents might encounter psychological vulnerabilities while completing the survey. The researchers tried to mitigate possible stressors by carefully reviewing the items for appropriacy and sensitivity with multiple reviewers and reminding participants that completing the survey was voluntary, so they could stop at any time or skip questions that they did not wish to answer. Another issue was that participating in research takes time that many busy academic parents do not have in excess; therefore, the researchers ensured that the survey could be finished in approximately 15 min through trial runs. Finally, our online data collection method through Qualtrics™ maintained anonymity since the data were collected in one centralized database without email or IP addresses.

Findings

This section reports the results of the responses gathered using the survey instrument. Data on how participants were affected by the pandemic, information about their physical workspaces, number of children, and research productivity are reported here.

Ways COVID-19 impacted academic parents’ domestic spheres

More than one-third of the participants (34%) had worked entirely at home since the onset of the pandemic in March 2020, with the remainder experiencing a mixture of home and on-campus work, which had varied over the course of the pandemic. A relatively large proportion of the participants (42%) said that their child or children’s school learning situation had been entirely at home throughout the pandemic, with the remainder having children who were educated in varying models of home and school. The participants were asked if they had been personally affected by illness due to COVID-19, and over one-third (37%) stated that either they or their immediate family had had the virus. In addition, slightly less than half (48%) of the faculty had been affected due to issues such as close contact with a positive case and needing to quarantine either because of this or travel.

Support from others in looking after children had varied as a result of the pandemic, with 64% of participants experiencing greater levels of support from their spouses, presumably due to their increased physical presence in the home. A large proportion (82%) of the academic parent participants agreed or strongly agreed that their domestic responsibilities in relation to their children had increased. Close to three-quarters of the sample agreed or strongly agreed that involvement with helping and supervising children’s schoolwork and domestic responsibilities other than in connection with children had increased.

Ways COVID-19 impacted academic parents’ working lives and productivity

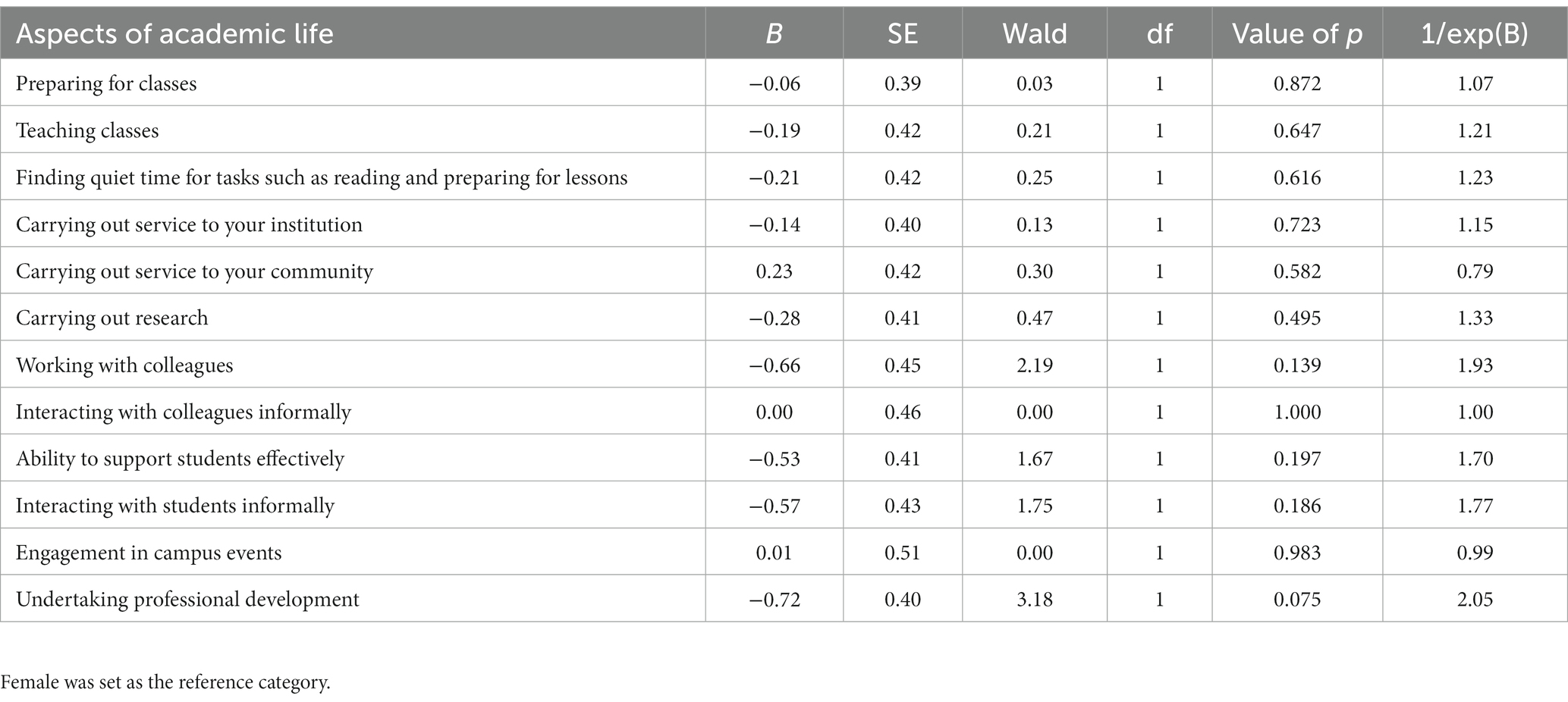

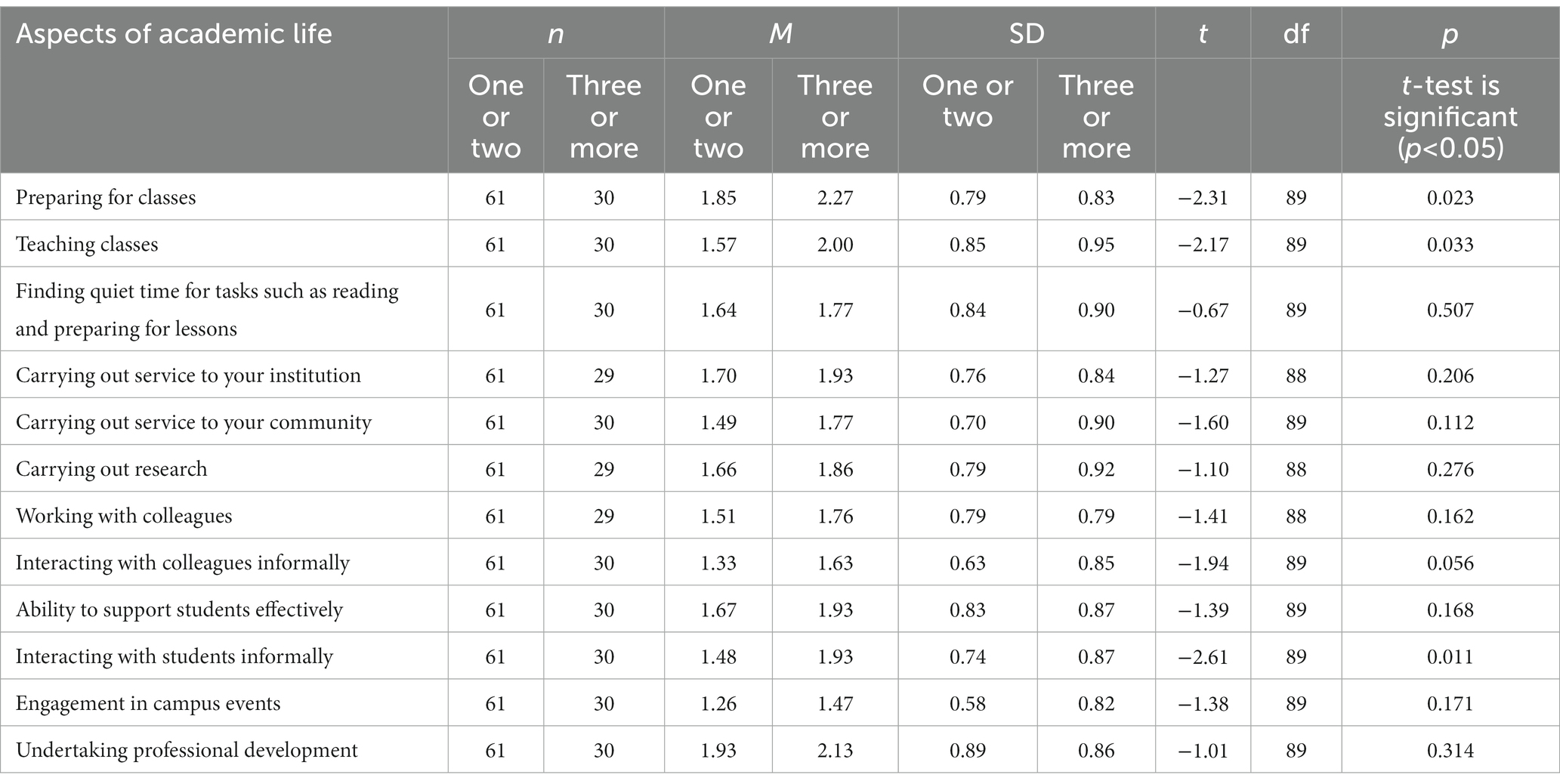

Table 1 presents the levels of ease or difficulty with which academic parents experienced academic life during the pandemic compared to before.

Table 1. Levels of comparative ease of dealing with aspects of academic life during the pandemic (n = 93).

Overall, the responses indicated that most aspects of academic life had become more challenging since the onset of the pandemic. Predictably, aspects that regularly occurred in a face-to-face context (such as engagement in campus events, interacting with colleagues informally, working with colleagues, and carrying out community service) became more difficult. The spontaneous nature of these interactions and subsequent intellectual stimulations was a theme of the qualitative responses too, as this response shows:

I miss being on campus and being around colleagues to discuss research-related stuff.

This sense of professional isolation extended to relationships between teachers and students. Another qualitative response exemplifies how the participant felt about not being able to connect face-to-face with their students:

It has been much more difficult to connect with and understand the needs of students when the only interaction is online, and students never turn on their cameras. Online teaching has left me feeling totally disconnected from them and that has caused stress, knowing that I am not able to address their needs as well.

Notably, though, around a third of the participants reported finding preparing for classes easier, while a similar proportion of the sample found that class preparation had become more difficult. These findings are corroborated by some of the qualitative data responses, where participants pointed out their preference for remote teaching due to the extra family time it afforded, flexibility, and gain of time spent previously commuting, e.g.,

Working remotely may be much better than working in person. There are tasks that can be done virtually without the need to come to campus.

I think online learning is great and should continue to be an option in the future along with remote work for parents, especially of very young children.

One mother spoke positively about the additional time which working from home had provided to set up her child and herself for the day’s online schooling:

I got extra time at morning as a mother to take care of my kid and prepare her and myself for the online classes.

Other parents also enjoyed the extra time at home with their families which the situation of working from home, as well as a reduction in activities in general, created, as these excerpts show:

Extra-curricular activities were all canceled so I spent no time driving my daughter to extra classes and waiting for her.

Not having to rush in the mornings – travel time to school and office no longer a factor so kids get additional ‘lie in’ time not just at weekends.

Other respondents were less positive about their online experiences. They felt that the responsibility of doing this while managing home responsibilities had created stress and often left them feeling ill-equipped to teach remotely due to “exhaustion and the lack of sufficient resources.” Some academic parents articulated the sense of a “loss of work and home time balance due to the pandemic” and struggled to maintain clear delineations and boundaries between work and home, e.g.,

Because we spend most of the day in front of the screen, there is some kind of overlap between personal, family and professional life.

The omnipresence of domestic help in the UAE, as in most Gulf countries, and the support in the home that this provides many academic parents was a theme in some qualitative responses. Two examples are provided here:

lt helps so much to have a nanny. The nanny culture and domestic help culture has helped the UAE a lot during the pandemic.

Yes, I am not rushing out the door in the morning and am able to spend more time with my son. I am also better able to see any issues that arise with his nanny.

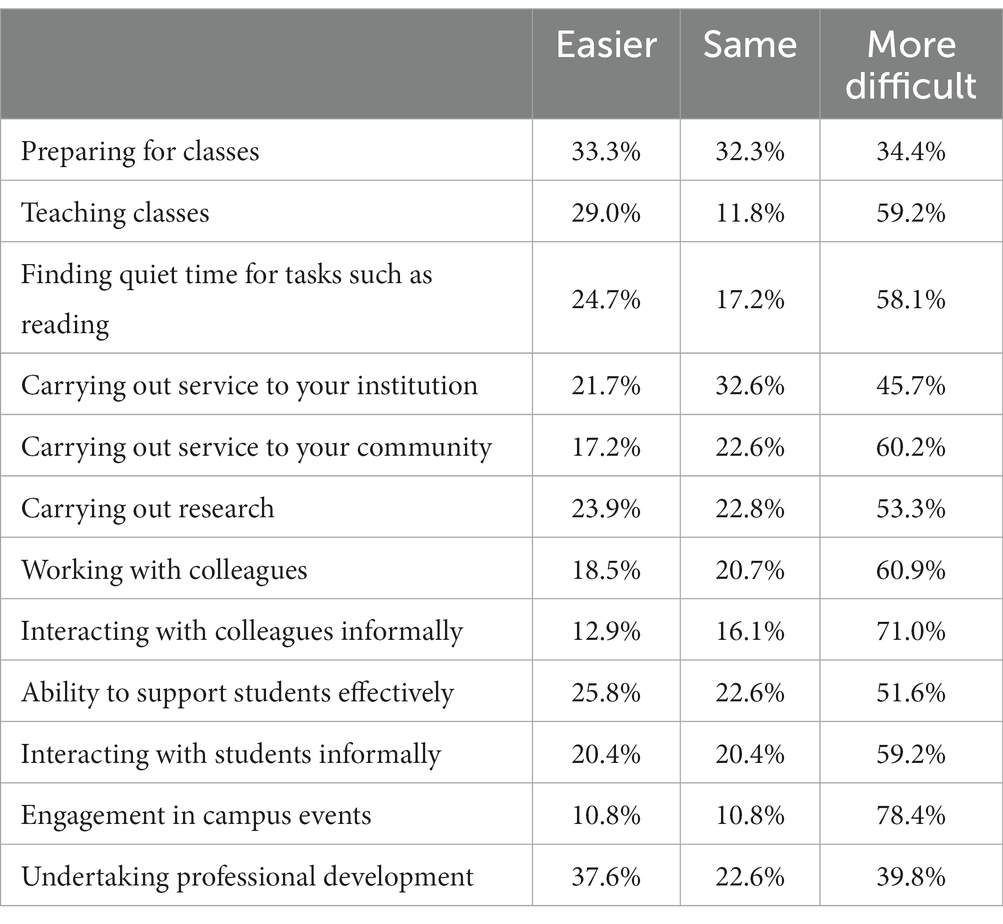

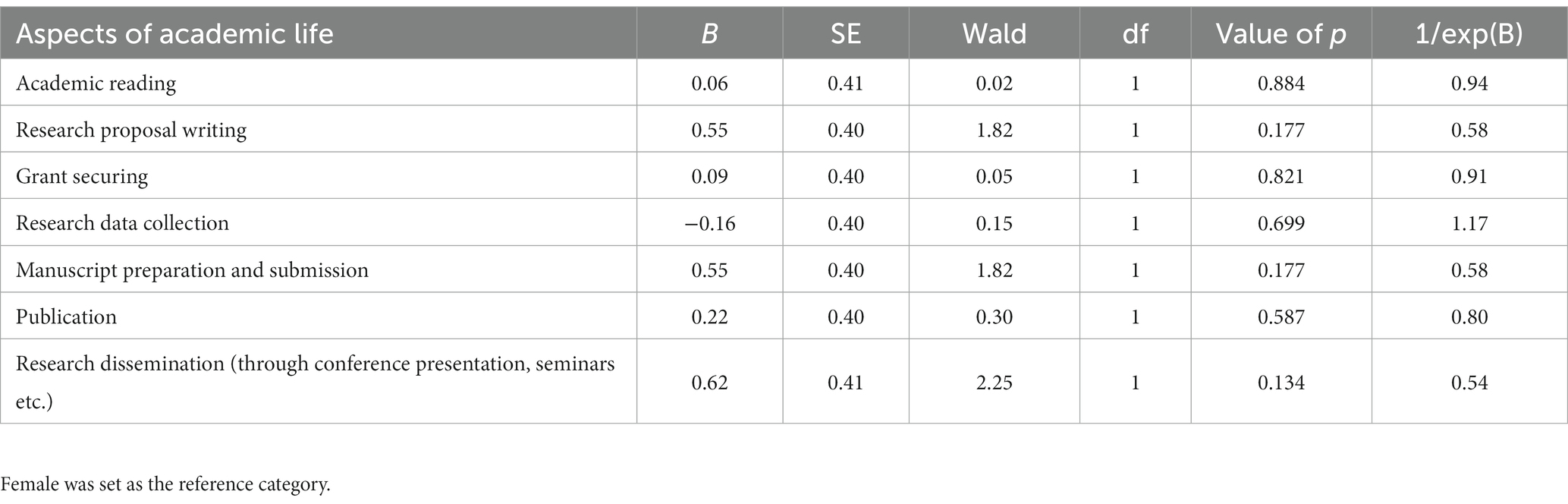

We conducted statistical analyses of the items in Table 1 in order to compare the levels of ease or difficulty with which academic parents (males and females) experienced academic life during the pandemic compared to before. We used ordered logit regression to compare these responses based on gender, but found no statistically significant differences between males and females in all aspects of academic life presented in Table 1 (see Table 2 for this analysis).

Physical workspace

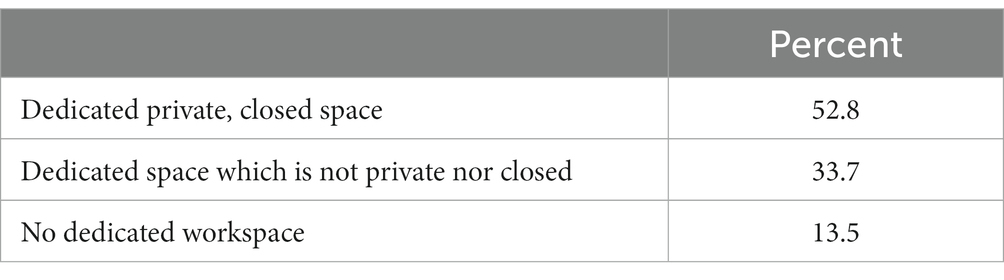

Table 3 shows the participants’ physical working space provision in the home. This was important as we hypothesized that this might have a direct bearing on the likelihood of being able to work effectively in the home, which is used in analysis later.

Since access to a private, closed workspace was an important consideration for participants, we used ordered logit regression to compare these responses from Table 3 to those in Table 1. However, we found no statistically significant differences between these two groups of academic parents (those with private closed space and those without) in all aspects of academic life presented in Table 1.

We hypothesized that the relative proximity of children while the faculty parents were working at home might be important, given the possibility of interruptions to work. Over half of the participants had children present or near them while working, and almost 70% reported having been distracted or interrupted as a result, a rather startling statistic. Around 12% of the participants said they were responsible for their children while they were teaching their online lessons, while approximately one-third said their spouses were also accountable for the children and 31% reported that a helper, nanny, or family member, was also responsible (these options were not limited to one only, and participants could choose as many options as applied).

Number of children

We considered that the number of children faculty parents have living with them at home might influence the degree of challenge, musing that parents with only one or two children might experience the challenges of academic life as more manageable than those with three or more. A relatively large proportion of participants have one or two children living with them, while 33% have three or more.

Further analyses (ordered logit regression) were carried out to investigate the possible effect of the number of children faculty parents have living with them (one or two, three or more) on each aspect of faculty life noted in Table 1. The assumption of homogeneity of proportional odds was first assessed. For each aspect of academic life, the value of p associated with the −2 log-likelihood test was greater than 0.05, which indicated homogeneity of regression coefficient across the three response categories (easier, same, more difficult). The results presented in Table 4 showed there were statistically significant differences between faculty parents with three or more children and those with one or two children in three aspects of academic life, including preparing for classes, teaching classes, and interacting with students informally. The odds of faculty parents with three or more children considering preparing for classes to be easy was 2.64 times that of faculty parents with one or two children, a statistically significant effect, Wald χ2(1) = 5.29, p = 0.021. Regarding the teaching classes aspect, the ordered logit regression model was also statistically significant, Wald χ2(1) = 4.48, p = 0.034, the odds of faculty parents with three or more children considering teaching classes to be easy was 2.53 times that of faculty parents with one or two children. Similarly, the odds of faculty parents with three or more children considering interacting with students informally to be easy was three times that of faculty parents with one or two children, a statistically significant effect, Wald χ2(1) = 6.42, p = 0.011.

Table 4. Comparing the academic experiences of faculty parents based on the number of children they have living with them at home (n = 93).

Research productivity

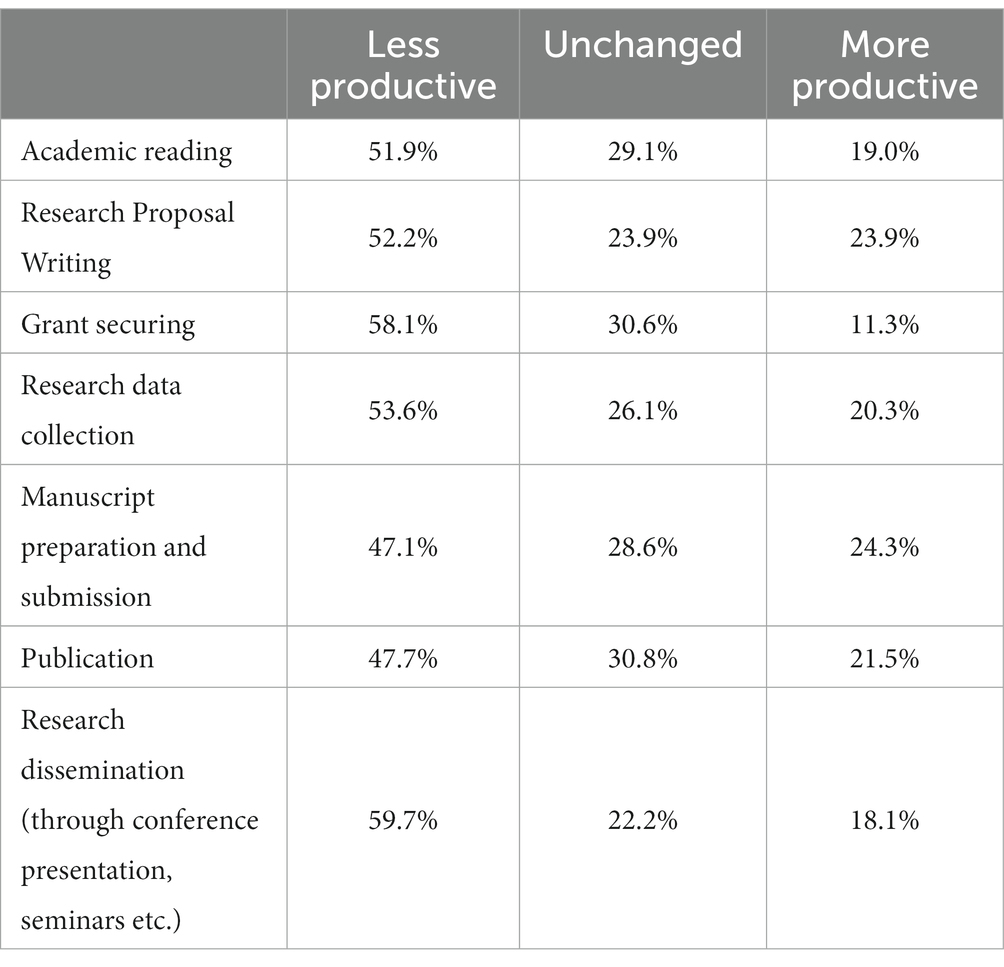

Faculty were asked to reflect on the relative priority they placed upon research compared to teaching. The percentages of the sample who prioritized research over teaching prior to the pandemic were approximately similar (10 before and 12% during). However, those who prioritized teaching over research had increased compared with before the pandemic (49% before and 60% during). Table 5 shows how the pandemic affected the participants’ perceptions of aspects related to research productivity.

Table 5. Participants’ perceptions of changes to aspects of research productivity because of the pandemic (n = 92).

Hypothesizing that those who had private closed workspaces to work at home might find these aspects of academic life less challenging, we used ordered logit regression to analyze differences between these groups of parents, but there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups (p < 0.05). Further ordered logit regression were carried out to investigate the possible effect of faculty having children beside them (yes/sometimes, no) on each aspect of research productivity noted in Table 5. It was found that there was a statistically significant difference between these groups of parents in one particular area of research work – academic reading, Wald χ2(1) = 5.80, p = 0.016, the odds of faculty parents who do not have their children beside them when teaching online from home considering academic reading to be more productive was 2.8 times that of faculty parents who did have their children beside them.

We then analyzed the research productivity outlined in Table 5 to compare faculty parents with one or two children living with them and those with three or more, using ordered logit regression, and found no statistically significant differences between these two groups of parents in aspects of research productivity. In other words, research productivity did not appear to be linked to the number of children living at home with faculty.

More than half of respondents (52%) stated that since the pandemic began, support with their research from their institution had decreased. This is an important figure, and we can use this as a basis to review the qualitative responses. While grant funding by internal and external sources may have been curtailed during the pandemic for some, one participant commenting on the research conflict explained that even though she actually had greater access to grant funding, the challenges she was facing in her teaching meant that she was not in a position to avail them:

Research grant options at my institutions have increased. However, I am teaching four different courses in one semester to students who open the computer and are not really there.

Support with one’s teaching was mostly articulated through practical offerings of IT help with technical difficulties, providing teaching and learning platforms, making professional development courses about online teaching available, and informal professional development support. For those participants who voiced experiences of not feeling supported by their institutions, these were often due to workload – increased class sizes and consequently increased marking, etc., or the lack of support from an individual line manager. Participants expressed frustration about the perceived lack of understanding their management had about the challenges of teaching online, as these responses show:

Top management thinks that teaching online is easy. Most of them do not teach even one class, so they do not know what it is like.

Comparing female and male academics’ reported research productivity

Table 6 presents academic parents’ (males and females) perceptions of changes to aspects of research productivity because of the pandemic. No statistically significant differences between males and females were found in all aspects of research productivity presented in Table 5.

Table 6. Comparing academic parents’ perceptions of changes to aspects of research productivity because of the pandemic based on gender (n = 92).

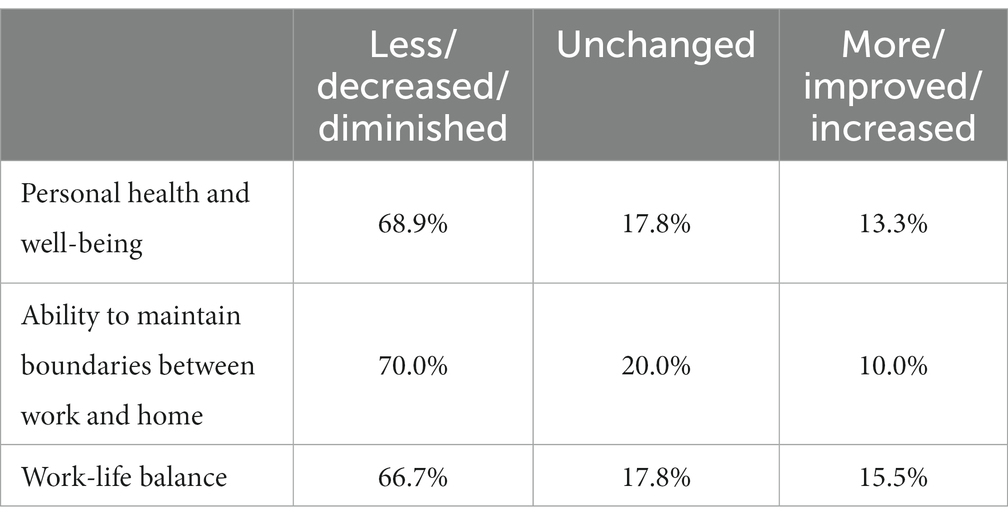

Faculty health and well-being

Table 7 presents the quantitative findings of participants’ sense of their health, well-being and work-home balance, and generally indicates that all areas have been negatively impacted since the onset of the pandemic.

Echoing this pattern in the quantitative data, one participant responded:

During the lockdown/school from home period, I found my responsibilities in all areas growing significantly, often to the point of overload and at the expense of my health.

Some also expressed concern that fears over safety, e.g., the sufficiency of COVID protocols during the pandemic, were not taken seriously enough by institutions, with mixed experiences of support for this and for student and faculty well-being, e.g.,

Focus should be on mental wellbeing instead of academics during the pandemic. This is an issue that is not being addressed in primary nor tertiary education levels.

Discussion and implications

While academic parents were dealing with a sudden shift in teaching delivery mode and being away from their classrooms, offices and resources, they were also faced with supporting children undergoing similar changes. Although many academic parents in the UAE employed help for housework, some specifically for childcare, 82% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that they had experienced increased domestic responsibilities. Almost two-thirds of participants also reported greater levels of support for looking after children from spouses, yet three-quarters of participants still agreed or strongly agreed that they were more involved with helping or supervising their children. This could be due to other childcare provisions including extended family being no longer available or the academic parent having an increased presence in the home leading to more involvement in domestic tasks, even if they may have had a finely tuned routine and division of labor prior to the pandemic. This is supported by other studies, which showed that academics (females particularly) at home during the pandemic had to take on many tasks that had not previously been their responsibility (Yildirim and Eslen-Ziya, 2021). Over one-third of respondents reported being personally affected by illness, with either themselves or their immediate family contracting the COVID-19 virus, giving the research team a useful insight into the situation faced by participants. Any illness for oneself or a family member is likely to impact the ability to work negatively, but an illness that is relatively new and without a known cure at the time of data collection is likely to cause additional mental and emotional burdens.

Given changes to working life, the additional stress of supporting children through the pandemic and online schooling, and dealing with the virus itself, it is no surprise that aspects of academic life became more challenging. More than half of the participants reported that teaching their classes, finding quiet time for tasks such as reading and preparing, engaging in campus events and community service, and interacting informally with colleagues had become more difficult for them. The faculty response to the survey question regarding their well-being indicated that a high proportion had felt this aspect of their lives had suffered. Perhaps this was partly related to missing the human interactions afforded on campus and the stimulation of colleagues’ conversations. Possibly these interactions and conversations release stress, providing a sense of normalization which was then missing for the participants. A significant number (58.1%) of participants also reported facing more challenges in interacting with students informally, and the stress caused by feeling disconnected from students was a common theme in the qualitative responses. A large proportion participants also reported a lack of support from institutions in terms of both research and academic tasks – this is something which institutions would do well to analyze and identify key areas of support lacking, since we can see from the qualitative responses that it adversely affected many participants and in some cases caused a direct chasm between academics and administration. While we did not specifically ask participants about their perceptions of institutional support in relation to their health, well-being, and work-home balance, given that at least 60% of respondents reported that these aspects had deteriorated during the onset of the pandemic, it would be interesting to investigate what, if anything, institutions had done in this regard, and how it was perceived by faculty, particularly parents. Interestingly, no significant differences were found between the perceptions which female and male parents had of difficulty or ease with life during the pandemic compared to before. This was perhaps surprising, given what is known about the often profound differences between female and male academics’ experiences (see for example Mason et al., 2013; Sallee et al., 2016), and as discussed earlier, the impact that these gendered disparities often have on research productivity. One possible explanation could be that the common practice of having paid help to support with household tasks, chores, childcare in the UAE could have mitigated some of the stress and workload differences between the genders. It is also possible that a larger sample would have shown some disparity, but for this group we did not observe this.

Academic parents having a dedicated, closed, private workspace was hypothesized to support the effective completion of academic tasks; however, our analysis showed no statistically significant differences between parents who did or did not have such spaces. This may indicate that simply having access to such a private workspace did not mean that the faculty was actually able to avail the benefits of that space, perhaps being so taken up by other tasks such as supervision of schoolwork and increased domestic responsibilities. Alternatively, interruptions from their children being so prevalent might have meant that they were not able to take advantage of it in any case.

While the percentages of faculty prioritizing research productivity over teaching did not substantially change, their prioritizing teaching over research during the pandemic did. Presumably, this was in part as a result of the changed teaching mode and having to prepare resources and build courses on unfamiliar platforms, for example. This type of ‘urgent’ task tends to mean that research can take a ‘back seat’ in the list of a busy academic’s priorities but doing so means that research productivity would likely decrease. Indeed, previous research supports our analysis (see, for example, Fertig, 2020; Myers et al., 2020; Staniscuaski et al., 2021) in that more than half of the participants perceived that they had become less productive in research (using various indicators such as writing proposals, securing grants, collecting data, preparing, submitting, and disseminating research). We were also interested in finding out whether the challenges to research productivity were exacerbated by faculty having stated that a child or children were seated close beside them while they worked. We were somewhat surprised to discover that in all but one of the tasks, academic reading, no statistically significant difference between the groups was found. This could be related to academic parents overcompensating by ‘working overtime’ to meet their professional research responsibilities even during trying times. The majority reported that the pandemic negatively impacted their health, well-being, and work-home balance. We did not specifically ask faculty to state their academic rank, and it is possible that there would have been differences in research productivity (and impact on one’s academic work in general) between these groups. We suggest that future studies with a larger sample size could include this question in their survey questionnaire since different ranks may have disparate expectations of research productivity.

Nonetheless, around half of all participants reported they were less prolific in all aspects of research productivity due to the pandemic. Given that the effects of the pandemic are still ongoing at the time of writing, these findings are likely not constrained to the period under study. Furthermore, given that the majority of our survey participants were female, this could have significant consequences for future promotional prospects and pathways for female academics, echoing previous findings (see, for example, Alon et al., 2020; Nash and Churchill, 2020; Wenham et al., 2020). With this recent decrease in scholarly visibility, women are less likely to be invited to speak at conferences or to serve in other academic roles, such as manuscript and grant reviews. Since women already face bias in these areas (Helmer et al., 2017; Witteman et al., 2019), these combined factors will lead to a quantifiable decline in publications and grant submissions from women. As these are the currency of academia (Kibbe, 2020), the career trajectories of academic mothers may be adversely and disproportionately affected by the effects of the pandemic (Alon et al., 2020; Wenham et al., 2020) and may have promotional pathways derailed or postponed as a result. Controversially, Nash and Churchill (2020) have argued that “COVID-19 provides another context in which universities have evaded their responsibility to ensure women’s full participation in the labor force” (p. 1). There have been some calls for institutions to attempt to level the playing field by altering promotional pathways, changing grant calls, extending ‘tenure’ periods, etc. (Oleschuk, 2020). It remains to be seen how higher education institutes in the UAE respond in support of academic parents.

There was also no statistically significant difference between the number of children living with academic parents in how these challenges were perceived. Possible reasons for this could be that in larger families, older children might already be accustomed to looking after younger children and, in particular, helping them with schoolwork, thus compensating for more children in a house where a faculty member is attempting to work. There may also be well-established routines within a large household, dating from before the pandemic and partly established by the schools with the online lesson schedule. Larger families may also be more likely to have more domestic help, like a live-in nanny. For all faculty members, it is possible that the presence of children actually mitigated remote working troubles as they may have desired to provide good role modeling during working hours (no leisurely surfing!).

Conclusion

Our study has highlighted the juggling act of academic parenting and has shown that the pandemic has created situations of both challenge and ease for those in the dual role of an academic and a parent. While the survey data suggested that academic parents felt that some aspects of their research productivity were reduced during the pandemic, the data also indicated no statistically significant impact on academic parents’ perceived ability to interact with students or colleagues at their institutions while working from home. Based on these findings, it is imperative for institutions to take into account the ability of faculty to fulfil their professional obligations from home, especially post-pandemic, since their children will most likely be in school or daycare. Therefore, moving into a post-pandemic era, many academic parents would like flexible work conditions to remain at their institutions, predominantly supporting a hybrid model that combines the advantages of working from home and on campus. While flexible working options can lead to greater equality, it is vital to ensure that they do not lead to more ingrained traditional gender roles in the family or workplace whereby the expectations are that men use the time to enhance their work performance (Lott and Chung, 2016) and women take on additional family responsibilities (Hilbrecht et al., 2008). However, with justice and professionalism in mind, flexible work options may afford academic parents the freedom they need to balance their work and home life better while perhaps reducing their stress levels and improving their happiness and well-being, thus, possibly leading to increased work productivity and satisfaction, enhanced academic reviews and improved equity. It is our hope that the study findings can support work to reduce the burden on female academics as institutions work to strengthen attempts for equity and improvement in all aspects of faculty life, including evaluations for promotion.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Emirates College for Advanced Education IRB. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MD as study PI was responsible for developing the study concept and research design, and contributed to and oversaw all sections of this manuscript. JM contributed to the literature review, wrote the methodology section, contributed to the discussion section and was responsible for final proof-reading and revisions. RA carried out the data analysis and contributed to the findings section. MM contributed to both literature review and discussion section of the manuscript. MA, DE, and PT contributed to the literature review. All authors were involved in planning the study methodology and development of the data collection tool.

Funding

The researchers would like to acknowledge Emirates College for Advanced Education for their support of this work via an internal grant, and the research assistants involved in this project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer PRC declared a shared affiliation with the author JM to the handling editor at the time of review.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.952472/full#supplementary-material

References

Alfawaz, H. A., Wani, K., Aljumah, A. A., Aldisi, D., Ansari, M. G., Yakout, S. M., et al. (2021). Psychological well-being during COVID-19 lockdown: insights from a Saudi state University’s academic community. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 33:101262. doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2020.101262

Alon, T., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J., and Tertilt, M. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on gender equality. Discussion Paper Series 224_2020_163. University of Bonn and University of Mannheim.

Alsairafi, Z., Naser, A. Y., Alsaleh, F. M., Awad, A., and Jalal, Z. (2021). Mental health status of healthcare professionals and students of health sciences faculties in Kuwait during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:2203. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18042203

Amano-Patiño, N., Faraglia, E., Giannitsarou, C., and Hasna, Z. (2020). “Who is doing new research in the time of COVID-19? Not the female economists” in Publishing and measuring success in economics. eds. S. Galliani and U. Panizza (London: Centre for Economic Policy Research)

Andersen, J. P., Nielsen, M. W., Simone, N. L., Lewiss, R. E., and Jagsi, R. (2020). Meta-research: COVID-19 medical papers have fewer women first authors than expected. eLife 9:e58807. doi: 10.7554/eLife.58807

Bailyn, L. (2011). Redesigning work for gender equity and work-personal life integration. Commun. Work Family 14, 97–112. doi: 10.1080/13668803.2010.532660

Bianchi, S. M., Sayer, L. C., Milkie, M. A., and Robinson, J. P. (2012). Housework: who did, does or will do it, and how much does it matter? Soc. Forces 91, 55–63. doi: 10.1093/sf/sos120

Brown, S. M., Doom, J. R., Lechuga-Peña, S., Watamura, S. E., and Koppels, T. (2020). Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse Negl. 2:110. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104699

Cluver, L., Lachman, J. M., Sherr, L., Wessels, I., Krug, E., Rakotomalala, S., et al. (2020). Parenting in a time of covid-19. Lancet 395:64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30736-4

Derrick, G. E., Jaeger, A., and Chen, P-Y., Sugimoto, C. R, Van Leeuwen, T. N., and Lariviere, V. (2019). Models of parenting and its effect on academic productivity: preliminary results from an international survey. In Proceedings of the 17th international conference on Scientometrics & Infometrics. International Society for Informetrics and Scientometrics, 1670–1676.

Dickson, M. (2019). Academic motherhood in the United Arab Emirates. Gend. Place Cult. 26, 719–735. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2018.1555143

Ecklund, E. H., and Lincoln, A. E. (2016). Failing families, failing science. New York: University Press.

Fairweather, J. S. (2002). The mythologies of faculty productivity: implications for institutional policy and decision making. J. High. Educ. 73, 26–48. doi: 10.1080/00221546.2002.11777129

Fertig, E. J. (2020). A mentee’s baby registry: supporting new academic parents in 2020. Cell Syst 11, 331–335. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2020.09.002

Grant, B. M., and Elizabeth, V. (2015). Unpredictable feelings: academic women under research audit. Br. Educ. Res. J. 41, 287–302. doi: 10.1002/berj.3145

Helmer, M., Schottdorf, M., Neef, A., and Battaglia, D. (2017). Gender bias in scholarly peer review. eLife 6:e21718. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21718

Hilbrecht, M., Shaw, S. M., Johnson, L. C., and Andrey, J. (2008). ‘I’m home for the kids’: contradictory implications for work–life balance of teleworking mothers. Gend. Work Organ. 15, 454–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0432.2008.00413.x

Joecks, J., Pull, K., and Backes-Gellner, U. (2014). Childbearing and (female) research productivity: a personnel economics perspective on the leaky pipeline. J. Bus. Econ. 84, 517–530. doi: 10.1007/s11573-013-0676-2

Kan, M. Y., Sullivan, O., and Gershuny, J. (2011). Gender convergence in domestic work: discerning the effects of interactional and institutional barriers from large-scale data. Sociology 45, 234–251. doi: 10.1177/0038038510394014

Kibbe, M. R. (2020). Consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on manuscript submissions by women. JAMA Surg. 155, 803–804. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.3917

Krapf, M., Ursprung, H. W., and Zimmermann, C. (2017). Parenthood and productivity of highly skilled labor: evidence from the groves of academe. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 140, 147–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2017.05.010

Krukowski, R. A., Jagsi, R., and Cardel, M. I. (2021). Academic productivity differences by gender and child age in science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine faculty during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Women's Health 30, 341–347. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8710

Lott, Y., and Chung, H. (2016). Gender discrepancies in the outcomes of schedule control on overtime hours and income in Germany. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 32, 752–765. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcw032

Mason, M. A., Wolfinger, N. H., and Goulden, M. (2013). Do babies matter: Gender and family in the ivory tower. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Minello, A. (2020). The pandemic and the female academic. Nature 17. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01135-9

Minello, A., Martucci, S., and Manzo, L. K. C. (2021). The pandemic and the academic mothers: present hardships and future perspectives. Eur. Soc. 23, S82–S94. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2020.1809690

Minnotte, K. L. (2020). Academic parenthood: navigating structure and culture in an elite occupation. Sociol. Compass 15, 1–14. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12903

Mueller, C., Wright, R., and Girod, S. (2017). The publication gender gap in US academic surgery. BMC Surg. 17, 1–4. doi: 10.1186/s12893-017-0211-4

Myers, K. R., Tham, W. Y., Yin, Y., Cohodes, N., Thursby, J. G., Thursby, M. C., et al. (2020). Unequal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on scientists. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4, 880–883. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0921-y

Nash, M., and Churchill, B. (2020). Caring during COVID-19: a gendered analysis of Australian university responses to managing remote working and caring responsibilities. Gend. Work Organ. 27, 833–846. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12484

Nulty, D. D. (2008). The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: what can be done? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 33, 301–314. doi: 10.1080/02602930701293231

Oleschuk, M. (2020). Gender equity considerations for tenure and promotion during COVID-19. Can. Rev. Sociol. 57, 502–515. doi: 10.1111/cars.12295

Power, K. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the care burden of women and families. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 16, 67–73. doi: 10.1080/15487733.2020.1776561

Rafnsdóttir, G. L., and Heijstra, T. M. (2013). Balancing work–family life in academia: the power of time. Gen. Work Organ. 20, 283–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0432.2011.00571.x

Reddick, R. J., Rochlen, A. B., Grasso, J. R., Reilly, E. D., and Spikes, D. D. (2011). Academic fathers pursuing tenure: a qualitative study of work-family conflict, coping strategies, and departmental culture. Psychol. Men Masculinity 13:1. doi: 10.1037/a0023206

Ribarovska, A. K., Hutchinson, M. R., Pittman, Q. J., Pariante, C., and Spencer, S. J. (2021). Gender inequality in publishing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Behav. Immun. 91, 1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.11.022

Rosewell, K. (2021). Academics’ perceptions of what it means to be both a parent and an academic: perspectives from an English university. High. Educ. 83, 711–727. doi: 10.1007/s10734-021-00697-5

Saddik, B., Hussein, A., Albanna, A., Elbarazi, I., Al-Shujairi, A., Temsah, M.-H., et al. (2021). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adults and children in the United Arab Emirates: a nationwide cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 21. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03213-2

Said, F., Jaafarawi, N., and Dillon, A. (2021). Mothers’ accounts of attending to educational and everyday needs of their children at home during COVID-19: the case of the UAE. Soc. Sci. 10:141. doi: 10.3390/socsci10040141

Sallee, M., Ward, K., and Wolf-Wendel, L. (2016). Can anyone have it all? Gendered views on parenting and academic careers. Innov. High. Educ. 41, 187–202. doi: 10.1007/s10755-015-9345-4

Santos, G. G., and Cabral-Cardoso, C. (2008). Work–family culture in academia: a gendered view of work–family conflict and coping strategies. Gen. Manage. 23, 442–457. doi: 10.1108/17542410810897553

Schiebinger, L., Henderson, A. D., and Gilmartin, S. K. (2008). Dual-career academic couples: What universities need to know. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Sevilla, A., and Smith, S. (2020). Baby steps: The gender division of childcare during the COVID-19 pandemic. Bonn: IZA Institute of Labor Economics.

Staniscuaski, F., Kmetzsch, L., Soletti, R. C., Reichert, F., Zandonà, E., Ludwig, Z. M. C., et al. (2021). Gender, race and parenthood impact academic productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic: from survey to action. Front. Psychol. 12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.663252

Suitor, J. J., Mecom, D., and Feld, I. S. (2001). Gender, household labor, and scholarly productivity among university professors. Gend. Issues 19, 50–67. doi: 10.1007/s12147-001-1007-4

Viglione, G. (2020). Are women publishing less during the pandemic? Here’s what the data say. Nature 581, 365–366. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01294-9

Wenham, C., Smith, J., and Morgan, R., Gender and COVID-19 Working Group (2020). COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak. Lancet 395, 846–848. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30526-2

Witteman, H. O., Hendricks, M., Straus, S., and Tannenbaum, C. (2019). Are gender gaps due to evaluations of the applicant or the science? A natural experiment at a national funding agency. Lancet 393, 531–540. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32611-4

Keywords: academic parents, COVID-19, productivity, family responsibility, universities

Citation: Dickson M, Midraj J, Al Hakmani R, McMinn M, Elsori D, Alhashmi M and Tedam P (2023) Academic parenthood in the United Arab Emirates in the time of COVID-19. Front. Educ. 8:952472. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.952472

Edited by:

Jorge Membrillo-Hernández, Tecnologico de Monterrey, MexicoReviewed by:

Peter R. Corridon, Khalifa University, United Arab EmiratesMatthias Krapf, University of Basel, Switzerland

Kaitlin Mallouk, Rowan University, United States

Copyright © 2023 Dickson, Midraj, Al Hakmani, McMinn, Elsori, Alhashmi and Tedam. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Martina Dickson, bWFydGluYV9kaWNrc29uQGhvdG1haWwuY29t

Martina Dickson

Martina Dickson Jessica Midraj

Jessica Midraj Rehab Al Hakmani

Rehab Al Hakmani Melissa McMinn3

Melissa McMinn3 Deena Elsori

Deena Elsori Mariam Alhashmi

Mariam Alhashmi