- 1School of Teacher Education and Leadership, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 2School of Teacher Education and Leadership, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 3School of Information Systems, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 4School of Management, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

It is well established that women bear greater caring responsibilities than men, however little is known about how this care work influences the decision-making processes of female carers who are considering Higher Education (HE). These deliberations occur well before women commit to enrolling and frequently result in carers making decisions to delay or not pursue HE, with consequences for their own careers and the persistence of gender inequalities more broadly. A scoping review of academic literature published since 1980 which followed the PRISMA-ScR process for scoping reviews was conducted to answer the research question “What is the scope of the literature regarding the influence of caregiver responsibilities on Australian women’s tertiary education decision making processes?” Studying the literature in one national context enabled the influences of personal as well as contextual influences to be identified. The results show that very little is known about how women who have caring responsibilities make decisions about whether or not to undertake HE studies. Important issues were identified such as the lack of a clear definition of carer and recognition of this cohort as an equity group. A complex array of personal, cultural and structural factors which may enable women’s HE decisions were identified, including the desire to achieve personal life goals, the encouragement and support of family members and supportive workplaces. However, constraints such as competing time demands, the continuing prevalence of traditional gendered expectations and idealised notions of HE students as unencumbered were also noted. No studies directly addressed decision-making processes, or how the many elements combined to influence female carers prior to enrolment. The paucity of research points to an urgent need for studies which will address the gaps in knowledge. This review points to new directions in research and decision-making theories to encompass the role of context and care in decisions, and provides some advice meanwhile to inform career practitioners, HE providers and career researchers.

1. Introduction

Women frequently wrestle with questions about whether they can balance higher education HE study with their caring responsibilities. These deliberations occur well before they commit to enrolling and often female carers make decisions to delay or not pursue HE. Female carers are the focus of this article, as they are an under-represented group in higher education. They are a vulnerable group who contribute at least $10.9 trillion of unpaid labour annually to the global economy (Coffey et al., 2020), yet may not be recognized as an equity group for HE purposes (Australian Government Department of Education, Department of Employment and Workplace Relations, 2020). For individual female carers, foregoing HE studies can impact mental health and manifest in lowered self-esteem, a lowered sense of self-fulfilment and identity issues (Cass et al., 2009; O’Shea, 2015; Irfan et al., 2017). Foregoing HE may also result in restricted workforce opportunities, increased vulnerability to redundancy, early retirement, lower wages, lower superannuation and a higher risk of poverty (Cass et al., 2009; Bimrose et al., 2015). At a societal level, there are economic, productivity and social mobility costs when women are under-utilised and/or underemployed (Wainwright and Marandet, 2010).This scoping review considers what research has been done and what needs to be done to understand the challenges that female carers confront, and what insights can inform career practitioners who support female carers.

Higher Education has long been recognised as a potential strategy for closing the persistent gender wage gap and addressing precarity. Global watchdogs including the World Economic Forum and the United Nations consistently highlight gender-based economic, political, educational and health inequalities (United Nations, General Assembly, 2015; World Economic Forum, 2021). Despite women’s participation in the labour force rapidly increasing over the course of the last century (Esteban et al., 2018), increasing participation rates in HE often hide the fact that women are more likely to have lower paid, casual and often precarious employment situations (Parvazian et al., 2017) and that caring demands can preclude enrolment for many female carers.

Care work is time-consuming and can include providing “unpaid care and support to family members and friends who have a disability, a mental illness, chronic conditions, a terminal illness, alcohol or other drug issues, or who are frail or aged” (International Alliance of Carer Organisations, 2021) Unpaid care work also includes the care of children, domestic work and voluntary community work (Australian Government Workplace Gender Equality Agency, 2016). Women undertake the majority of this unpaid care work (Bainbridge and Broady, 2017; Aarntzen et al., 2019; Schultheiss., 2021), with seven in 10 (71.8%) of Australian primary carers being women (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2019). Recent statistics suggest that “women undertake more than three-quarters of all unpaid care work … [and] 12.5 billion hours of unpaid care work every day” (Coffey et al., 2020). Globally, the estimated monetary value of care work is $10.9 trillion annually (Coffey et al., 2020); in Australia, it has been estimated to be $650.1 billion annually (Australian Government Workplace Gender Equality Agency, 2016). However, the economic contribution of women as carers is undervalued (Bimrose et al., 2019) and these contributions are omitted from national accounting measures (Australian Government Workplace Gender Equality Agency, 2016; Lynch et al., 2020).

It is well established in the fields of career education (Doherty and Lassig, 2013; Patton, 2013), economics (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2017; Craig and Churchill, 2021; DeRock, 2021), and feminist scholarship (Berik, 2018) that unpaid care work can hinder women’s employment opportunities and thus economic advancement. Higher education is frequently proposed as a response by policy reports, discussion papers, articles and commissions (Australian Human Rights Commission, 2008, 2013; Commonwealth of Australia, 2014; Gammage et al., 2019; Coffey et al., 2020; Kettell., 2020; International Alliance of Carer Organisations, 2021). Yet few researchers have focused on female carers’ decisions relating to HE (Lyonette et al., 2015; Bainbridge and Broady, 2017). There is international recognition that female caregivers face a range of challenges in HE study, however the focus of these articles tends to be on mothers rather than carers more broadly, and on the influence of care work on female carers post-enrolment as opposed to at the decision-making stage.

Care work brings additional time demands (OECD Development Centre, 2014), emotional giving (Fisher and Tronto, 1990), financial costs (Economic Security for Women, 2019; Gammage et al., 2019), and health precarity (Caputo et al., 2016), all of which can potentially influence women as they contemplate HE choices. It has been noted that “generational overlap” has increased demands on the “sandwich generation,” those generally middle-aged carers who are “squeezed” by simultaneously providing care for aging parents and children or grandchildren (Alburez-Gutierrez et al., 2021, p. 997). A study by Do and Brown (2014) found that sandwich carers faced increased health risks owing to the higher burden of caregiving and consequent reduction and self-care. Kavanaugh and Stamatopoulos (2021) highlight the particular inattention to young carers who have “existed on the fringes of the caregiving literature” (p. 487). Lynch et al. (2020) have expressed concern that while care is a salient political issue, “academic debates about social justice, outside feminist scholarship, do not generally define care relations (namely affective relations of love, care and solidarity) as key considerations” (p. 158).

As Lyonette et al. (2015) noted in their national (UK) longitudinal study, this care work does have “a significant impact on women’s choices and experiences before entering HE, during HE and afterwards” (p. 6). Caregivers are non-traditional students (McCall et al., 2020) who are more likely to withdraw from HE study (Kearney et al., 2018). While HE institutions may pride themselves on championing progress and equality, O’Hagan et al. (2019) have concluded that the role of universities within a culture of academic capitalism does not encourage universities to “challenge gender orders, but reinforces older hierarchies and traditional gender inequalities” (p. 218). In order to challenge these hierarchies and inequalities, more insights into the influences on female carer HE study decision-making processes are needed.

Decisions about HE constitute a significant aspect of career decision making for many women (Xu, 2021), yet the tertiary education decision-making processes of female care givers is a particularly ill-defined field. This article is a scoping review of research that focuses on Australian female carer decisions in HE. A scoping review is a systematic process of literature searching, in this case informed by PRISMA-ScR scoping review protocols (Tricco et al., 2018), that enables researchers to “identify knowledge gaps, scope a body of literature and clarify concepts” (Munn et al., 2018, p. 1). As the topic of Australian female carers and their decision-making processes about HE study has not been comprehensively reviewed previously, a scoping review is an appropriate choice to map and synthesise the key concepts which underpin the body of literature.

2. Researching decision making for HE study – The importance of context

National cultural contexts as well as more personal carer responsibilities have a profound impact on decisions relating to work and study for women (Schultheiss., 2021). This was illustrated around the world by COVID-19 when different public health policies were introduced requiring children to stay home from school with restrictions regarding access to day care, aged care, disability respite care and palliative respite care, necessitating an increase in unpaid care work (Australian Government Department of Health, 2020; Bahn et al., 2020; Douglas, 2020; Carer Respite Alliance, 2021). In Australia, social media commentary suggested that women primarily took on the additional care work that was required due to COVID-19 (Churchill, 2020). It is possible that this additional care work contributed to women postponing decisions to study in HE. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (2020) (Table 22), there was a statistically significant decrease in the proportion of women aged 15–64 years studying for a qualification at Certificate III or above level in 2020 (13.2%) compared to 2019 (14.4%). Such disruption underscores the importance of researching the influence of this care work in specific national contexts to understand the ongoing structural and cultural issues to do with work and study on women’s decisions about HE study. This review focused on HE in Australia, where Year 12 (senior year of high school) applicants represented only 35.1 percent of total applications for undergraduate degrees in 2021 (Australian Government Department of Education, Skills and Employment, 2021). Alternative entry points to Australian universities now dominate enrolments with mature age applicants (21+) able to utilise pathways which include enabling and bridging courses, vocational education and training pathways, credit for recognised learning and portfolio entryways which take into consideration work experience, endorsed programs and letters of support for applicants (Education Services Australia, 2022). There are opportunities for women with caring responsibilities to enter into HE study at multiple timepoints. However, the expectation that Australian students undertaking HE pay course fees, and the conditions attached to Australian Government Study Assist programs which assist eligible Commonwealth supported students to pay their HE fees with a loan (Australian Government, 2021a) may prohibit female carers from applying.

Eligibility requirements, including income and asset tests may preclude female carers on a broad range of factors including income from any paid work they may do, owning a home, having managed investments and/or superannuation or having a partner, as their partner’s income may impact any eligibility for payments (Australian Government, 2021b). For female carers who have foregone employment or reduced their paid working hours because of care work requirements, reduced finances may mean that they are less likely to enrol (Andrewartha and Harvey, 2021). While there are a range of pathways through which mature age students might enter Australian universities, national study support structures may make this prohibitive for female carers.

This scoping review has focused on one national context, Australia, as access to HE also differs according to different contexts, and “client’s cultures and context influence their career development” (McMahon, 2019, para. 9). Xu (2021) likewise notes that career decision making is heavily subject to the context within which decisions are made. Country specific policies and funding arrangements for HE may directly impact carers and influence the decisions that they make regarding HE enrolment (International Alliance of Carer Organisations, 2021). While this study is one of context, it points to the need for similar research to be conducted in other national contexts.

3. Decision making and care work in career theories

Calls for more diverse perspectives and for career theories that cater to the distinct needs and patterns of women have long been made. Patton and McMahon (2021) noted that the development of Traditional career theories and models such as Person-Environment models and the work of theorists including Super, Holland, and Tiedeman have been criticized as being “profoundly and, often unwittingly, influenced by broader macrolevel forces” which marginalized some sectors of the population, including women (Blustein, 2017, p.181). These theories have faced criticism regarding the way in which “white, male and middle-class assumptions” (Blustein, 2017, p. 183) including notions of traditional and stable career patterns comprised of continuous, full-time employment, have led to sexist constraints on women’s career options.

While few theories have been specifically designed for women, there are theories that have made adaptations and/or provision for the consideration of women’s careers. These have included Gottfredson’s Theory of Circumscription and Compromise which has been used to help women understand the ways in which they may have discounted careers deemed non-traditional for their gender (Bimrose, 2019). Hackett and Betz’ Self-efficacy theory (Patton and McMahon, 2021) factored in research which had demonstrated a difference in the self-efficacy of women and men, including evidence which showed that “women’s self-efficacy expectations with respect to a number of career variables serve as a relevant barrier to career choice and development” (p. 292). This theory has helped women to perceive the ways in which “gender role socialization” may have limited their options (Bimrose, 2019, p. 398) and has served to enhance self-confidence and a consideration of a broader range of career options – including those which are non-traditional with regard to gender. The metatheoretical Systems Theory Framework (Patton and McMahon, 2021) may support practitioners who are working with women to better understand the key influences on their career development. As clients are central to this theory, it serves to empower individuals through the telling and deeper understanding of their own stories, the identification of their own career issues and through collaboratively determining constructive actions, and thus is an effective theory for working with women.

While these theories have enabled practitioners to support women in their career development, they do not account for influences that prominent researchers have emphasised, including the fact that “women and girls have experienced, and continue to experience, persistent, deeply entrenched systemic disadvantages in their lives, including labour markets around the world” (Bimrose, 2019, p. 395). Blustein (2015) has questioned the degree to which existing theories can adequately address these complex issues. While Bimrose (2019) has noted that work is currently being done in an attempt to fill theoretical gaps with regard to women, Patton and McMahon (2021) have noted that “the construction of a unified theoretical understanding of women’s working lives and careers remains incomplete” (p297). An alternative theory of decision making that makes provision for the interconnections of career choices and care work could prove to be a welcome addition to the theoretical field.

One alternative explored in this article is Margaret Archer’s sociological critical realist Theory of Reflexivity (2000, 2007), which informed the conceptual framework for this review. Archer enables a study of personal, cultural and structural influences on decision making through a recognition of how individuals continually weigh up circumstances in an ongoing process of reflexivity (2007). According to Archer, learning about oneself via reflexive processes can enable individuals to develop a modus vivendi or ‘life worth living’ (2012). This is in line with one of the core aims of career counselling; to help clients achieve satisfaction by supporting them in the important decisions they make about their lives.

Archer (2007), identifies individual reflexivity as the core process of decision making and defines it as “the regular exercise of the mental ability… to consider themselves in relation to their (social) contexts and vice versa” (p. 4). It is exercised through the internal conversations which human beings commonly engage in (Archer, 2003). These inner conversations are important, as they are the foundation upon which people make decisions. Archer believes that the ability to conduct internal conversations makes most people “active agents … who can exercise some governance in their own lives, as opposed to ‘passive agents’ to whom things simply happen” (2007, p. 6). While this review does not focus on inner reflexivity, it does draw on Archer’s theory to scope out the personal, cultural and structural conditions that enable individuals to make decisions about what matters most to their lives. Additionally, ‘how’ the individual reflexively deliberates between personal, cultural, and structural considerations can be noted by examining how some conditions enable and constrain decision makers. Importantly, Archer (2012) acknowledges that the responses of individuals to the constellation of constraints and enablements they face will be unique. In these ways, Archer’s reflexivity theory facilitates a consideration of the range of factors which influence decisions and actions.

Archer’s Theory of Reflexivity has been utilised in previous studies in various work contexts (Willis et al., 2017; Baker, 2019; Ryan et al., 2019; Ryan and Barton, 2020). Naicker et al. (2016) considered “cultural and agential enablements and constraints” on their school leadership practices (p. 3). Baker (2019) drew on Archer to note that a deeper consideration of the constraints which operate as barriers to HE decision making could then serve as a catalyst for the implementation of supports which may enable students in this regard. Archer’s theory is a fitting choice given the range of well-acknowledged constraints female carers face in the pursuit of HE.

4. Methods

The objectives of this review are to determine the scope of the Australian literature on the topic of female carers and their decisions about HE study. This scoping review focused on research which has been conducted over the past 30 years. The process that was followed was the PRISMA-ScR Extension for Scoping Reviews (Tricco et al., 2018) to answer the following research question:

1. What is the scope of the literature regarding the influence of caregiver responsibilities on women’s tertiary education decision making processes?

The sub-questions for this review are:

1.1 What are the key concepts and definitions within this extant literature?

1.2 What is the focus in the literature about the influence of caregiver

responsibilities on women’s tertiary education decision making processes?

1.3 What future research possibilities are evident?

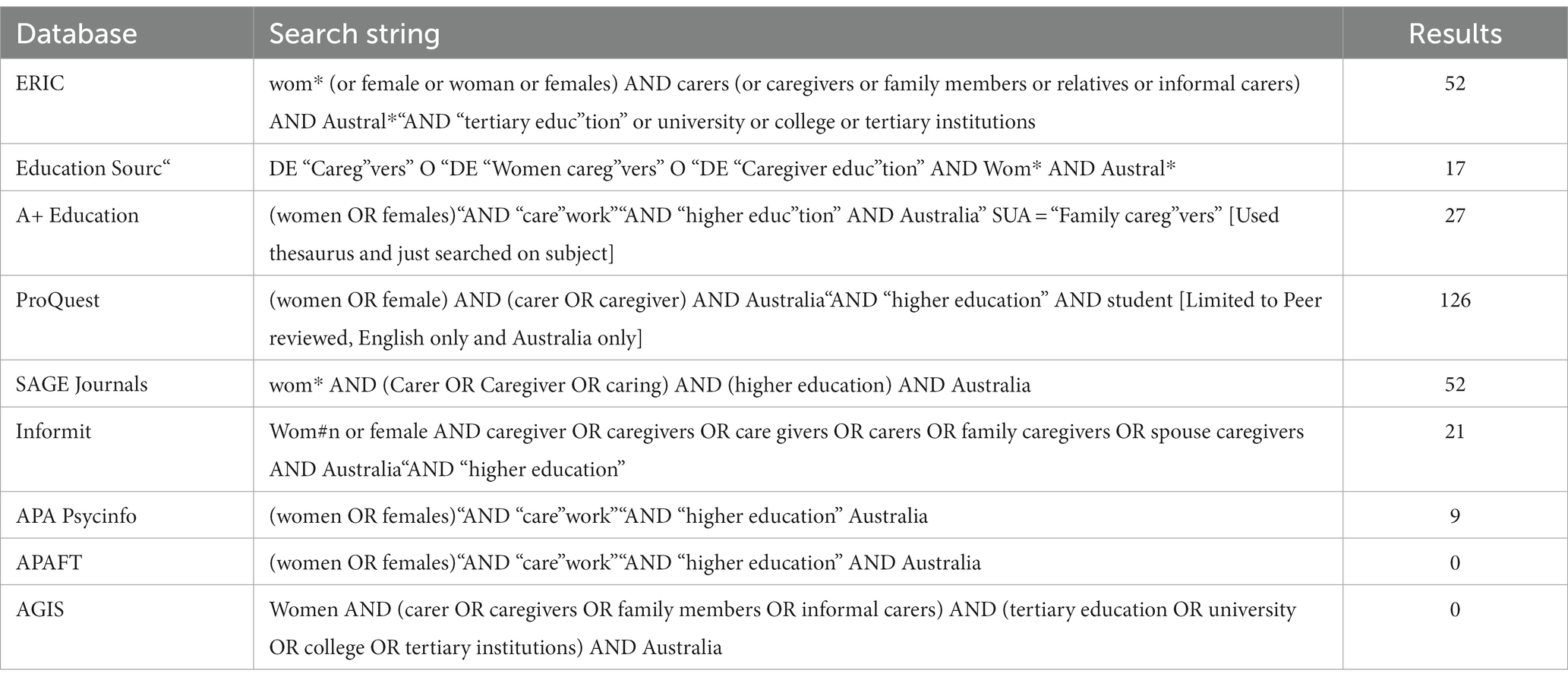

A keyword search was conducted across nine academic data bases which were selected to provide coverage of a range of higher education sources (see Table 1) using search terms listed within the thesaurus of each database (where available). As there are common synonyms for each of the key search terms, “OR” was utilised in most searches.

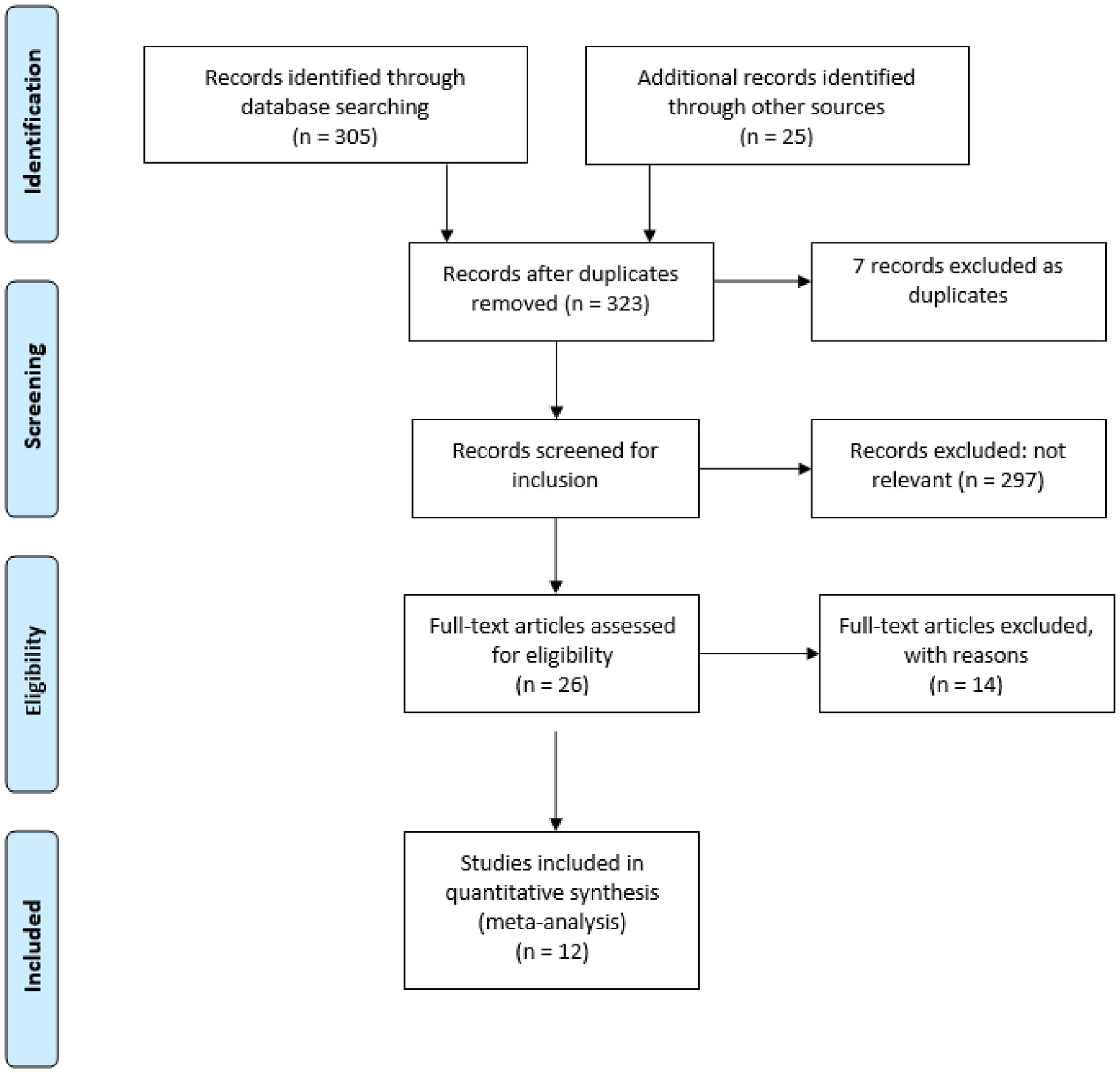

Sources were included if they were focused on female, unpaid caregivers, HE study, Australian context, and were peer-reviewed in order to ensure the quality and reliability of the research. Papers which had been published since 1980 and were written in English were included. Bibliographic databases were searched between August 2020 to January 2021 utilising the Search Strings as listed in Table 1: ERIC, Education Source, A+ Education, Proquest, SAGE Journals, Informit, APA Psycinfo, APAFT and AGIS. The electronic database search was supplemented by searching Google Scholar and scanning the abstracts of the first 50 of the 17,900 results returned and the titles of the next 100. During each of the database searches, notes were entered into an Excel spreadsheet, including the authors, year of publication, record title, journal of publication and the abstract. The initial search returned 305 sources. Following an abstract scan of each of these, inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied and sources were retained or removed from the list.

Seven duplicates were removed and 26 sources were selected for detailed reading. Following this final phase, 13 sources were removed because they did not meet the criteria for inclusion, and one could not be located and thus was not included in this analysis. The remaining 12 sources were selected for inclusion in this study (Figure 1).

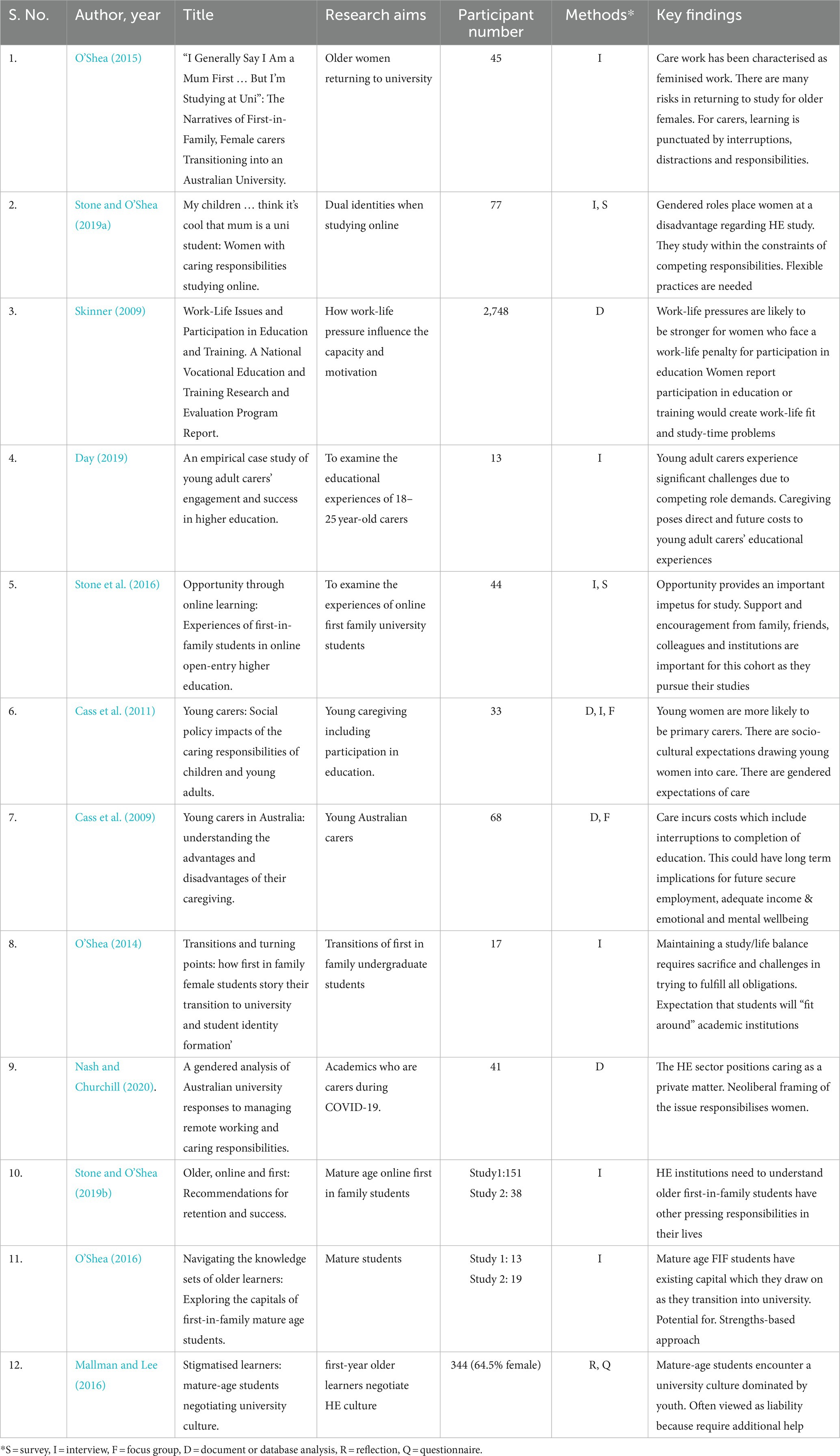

A majority of the included papers were journal articles (9/12) with the remaining three being Government or research centre which drew on a range of national data. Research which was undertaken for the journal articles was predominantly qualitative and the three national reports were mixed method studies, utilising interviews and quantitative analyses of existing data sets (Cass et al., 2009, 2011; Skinner, 2009; Table 2).

5. Results

The initial scoping review highlighted that only a few Australian studies have considered the influence of care work on the decisions that women make regarding HE study (RQ1). The decision-making processes prior to enrolment in programs of study was not the focus of any of the articles and were only incidentally referred to, with the focus being on the influence of caring post-enrolment in study. Widening participation may be an aspiration of HE institutions (O’Shea, 2014; Grant-Smith et al., 2020), however the fact that only 12 studies were located in a thorough search demonstrates that within an Australian context, little attention has been paid to this cohort of would-be learners. As Andrewartha and Harvey (2021) noted, “despite the large number of carers, their distinctive characteristics, and their educational challenges, little research has been conducted on carer access to, and achievement within, Australian HE” (p. 1). O’Shea (2015) likewise highlighted the need for further research in this area, saying “female caregivers are significantly represented in student populations across the globe, yet insight into the dilemmas and obstacles regularly encountered by these remains notably absent” (p. 255). Given the fact that universities are presently seeking to broaden their student base and the size of the potential student pool (Mallman and Lee, 2016; Grant-Smith et al., 2020) it seems both surprising and concerning that more interest has not been directed toward this group.

5.1. Who is regarded as a carer?

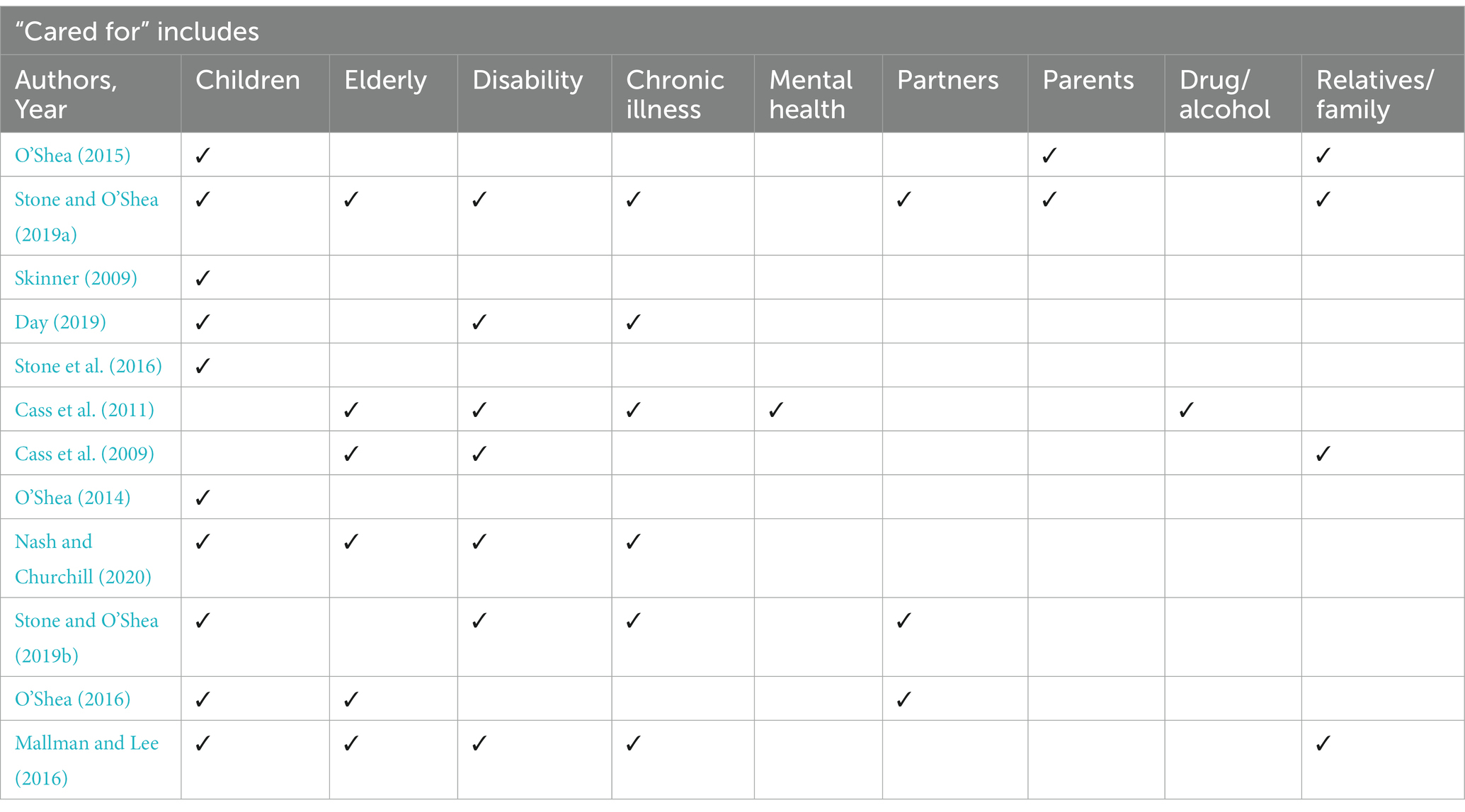

There are varied definitions and conceptualisations of care/caregiving/carer within the literature (RQ1.1). Cass et al. (2009, 2011) and Day (2019), defined young carers as ‘those who provide support to’ others. Carers were more usually defined by focusing on who is included in the “cared for” group (see Table 3). These ranged between care for “children, elderly parents and relatives” (O’Shea, 2015) to “caring for the disabled, those with long-term health problems or elderly family members” (Nash and Churchill, 2020, p. 834). While no definition was provided in six of the articles (Skinner, 2009; O’Shea, 2014, 2016; Mallman and Lee, 2016; Stone et al., 2016; Stone and O’Shea, 2019a,b), some reference was made to those who are cared for. Care for friends, neighbours or others who have no relation to the caregiver was not evident. The range of responsibilities highlights the challenges for potential students, and the challenge of definition may be one reason why the experiences of this group are under-studied.

The definition of carer is clearly not straightforward. Categorical definitions do not address the complexity of the carer’s role which will often include multiple carer responsibilities that impact their life beyond engagement with those who are cared for. Importantly, while these studies do not focus directly on the decision-making processes undertaken prior to enrolling in HE study, their focus on practical ramifications of the choice to study on the lives of students and their significant others is informative.

The majority of studies used qualitative interviews which were thematically analysed in order to gather data. The studies tended to focus on two carer groups, mature age students or student mothers and the challenges they face in achieving successful HE outcomes after enrolment (RQ1.2). O’Shea and Stone are the leading researchers with six of the included studies authored or co-authored by these Australian researchers. These studies focus on the experiences of mature age, female, first-in-family caregivers who are undertaking university studies, together with the effect of online study options for this cohort. Three of the other studies focused on young carers between 15 to 24 years of age (Cass et al., 2009, 2011), and 18–25 (Day, 2019). Skinner’s (2009) report for the National Centre for Vocational Education Research focused on the work-life pressure which influence individuals’ capacity and motivation to engage in education and training, while the remaining articles considered how mature age students experience the dynamics of university (Mallman and Lee, 2016) and the impact of neoliberalism on women (Nash and Churchill, 2020). These influences are likely to both enable and constrain women when they are engaged in decisions about their HE and are therefore examined in detail in the following section.

5.2. Influences that can enable women in study decision making

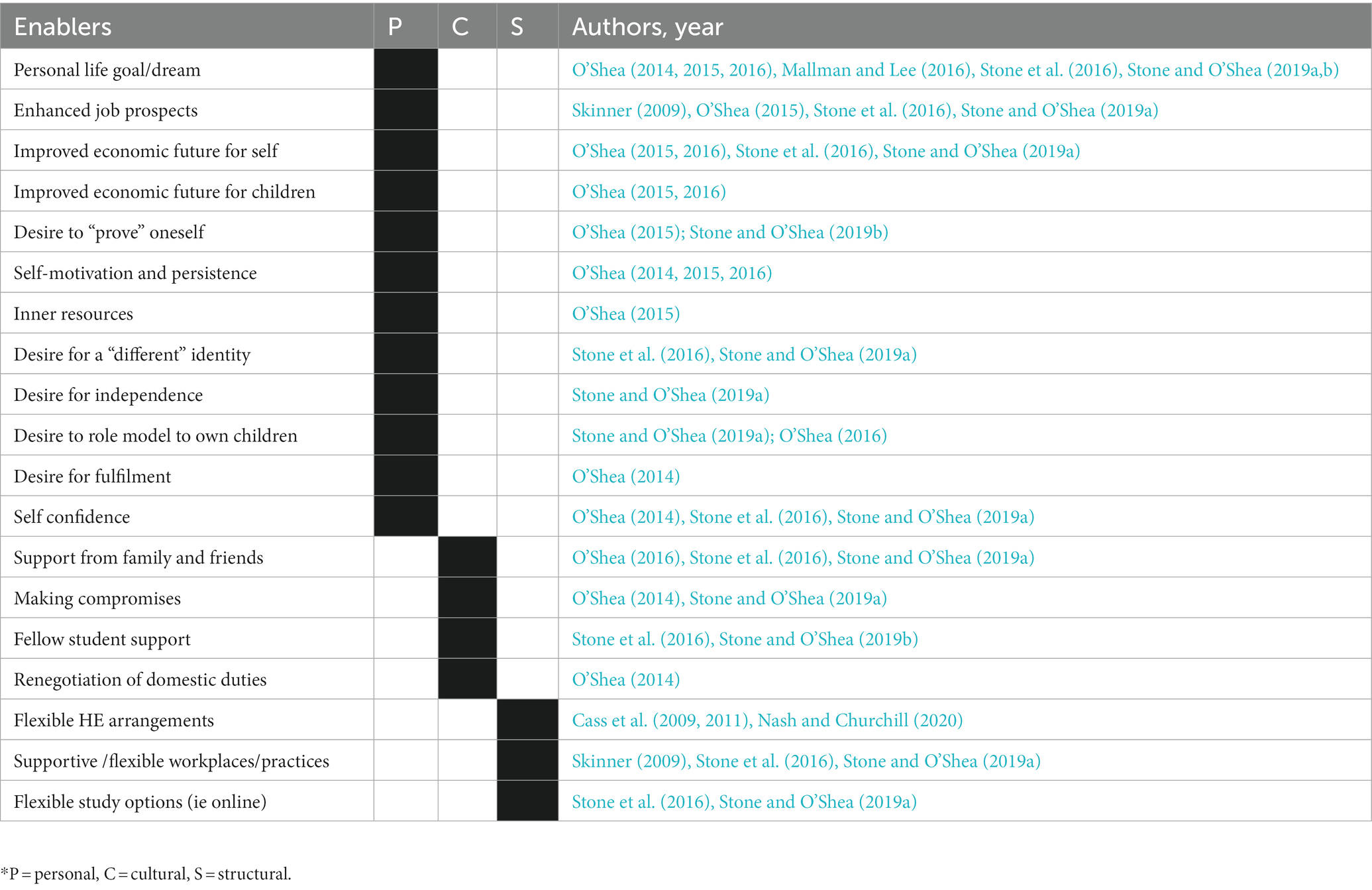

According to Archer’s (2003) theory of decision making, personal, cultural and structural influences often operate either alone or in conjunction with one another to enable individuals to make and enact decisions.

5.2.1. Personal influences and factors

Personal influences include the range of intrapersonal “emotions, beliefs, worldviews, efficacy and capabilities” which may influence individuals’ deliberations and decision-making (Ryan and Barton, 2020, p. 222) A range of personal factors and influences which enabled women to decide in favour of enrolment in HE studies were identified. O’Shea (2015) found regionally located, first in family, first year university students drew on a range of personal influences including the desire to pursue a long-held dream, a desire to do something for themselves, personal achievement – to “prove oneself” (O’Shea, 2015; Stone and O’Shea, 2019b) and the desire for independence and the development of an “own” identity (Stone et al., 2016; Stone and O’Shea, 2019a). Stone and O’Shea’s (2019a) mixed methods study of interviews and surveys with 77 women revealed a similar range of personal factors including “the fulfilment of a long-deferred dream.” Personal life goals and dreams were likewise identified in Stone and O’Shea’s remaining articles (O’Shea, 2014, 2016; Stone et al., 2016; Stone and O’Shea, 2019b). Mallman and Lee’s (2016) qualitative study explored the ways that 344 first year learners negotiated the culture of HE. Participants comprised 64.5% females, who identified similar enablers which propelled them toward HE studies. As one female participant (aged 46–55 years) noted “being at university fulfils a dream I have nurtured for many years” (p. 691). As these studies have demonstrated, personal aspirations are powerful motivators which enable women to make decisions for their futures.

Stone and O’Shea’s, 2019a study, together with Stone et al.’s, 2016 study highlighted women’s desire to be a role model to their own children as a motivation. Three studies (O’Shea, 2014; Stone et al., 2016; Stone and O’Shea, 2019a) noted the importance of self-confidence and three study of O’Shea’s (2014, 2015, 2016) highlighted self-motivation and persistence. These align with O’Shea’s (2015) noting of the importance of “inner resources” (p. 253) and how personal attributes may serve as enablers for women’s pursuit of HE studies.

5.2.2. Cultural factors and influences

A range of social and cultural influences enabled the participants in the included studies to commit to HE studies. Archer notes that cultural conditions are those that are grounded in ideas (2007). As Stone et al.’s (2016) noted, “the decision to engage in university study takes place within a social milieu that sometimes positively and sometimes negatively influence’s the student’s experience” (p. 157). The participants in the study of Stone and O’Shea (2019a) emphasised the importance of family members and friends in providing encouragement to pursue HE studies. Participants spoke of family members as the source of “inspiration and encouragement in making the decision” to study (p. 102) and of children who “inspired me” (p. 102). The study of Stone et al.’s (2016) similarly demonstrated the impetus family members and friends had provided regarding commencing and continuing HE study. One student noted that “encouragement and support from my husband helped with the decision to go back and do a degree” (p. 157). The study of O’Shea’s (2016) reiterated the importance of these social networks and further outlined the practical supports provided including childcare, financial support and provision of food. Participants in the study of Stone and O’Shea’s (2019a) discussed the fact that as students, they desired support in the form of understanding; that family and friends would understand their need for time and an environment which is conducive to study. While some participants received this support, it was not forthcoming in all cases, with complaints that “I’m not available [and] I’m always tired and angry … because of the time I spend studying” indicated by participants (p. 104).

5.2.3. Structural factors and influences

This scoping study also highlighted the enabling influence of supportive workplace and HE environments. These are examples of what Archer theorises are the material, or structural conditions that inform decision making (2007). In the study of Skinner’s (2009), which examined national data from the Australian Work and Life Index it was stated that

Developing policies, practices and workplace cultures that support flexible work practices tomeet study needs is likely to support and encourage all workers’ participation in education and training, and women in particular. Indeed, in this study, time supports were most often discussed by participants in terms of having more time off work to study (p. 9).

Appreciation for supportive workplaces was noted in the study Stone and O’Shea’s (2019a) with one participant noting that her workplace had allowed her to have “time off for exams and placement” (p. 103). The difference that this sort of support makes to HE students was reiterated in the study of Stone et al.’s (2016) where it was acknowledged that sometimes the leaders in organisations are the ones who encourage their employees to engage in study.

Online and flexible study options were another enabling structural factor. Caregivers in Stone and O’Shea’s, 2019a study emphasised that flexible work options made it possible for them to engage in HE studies, an enabling influence echoed in the study of Stone et al.’s (2016). One female caregiver shared that she “had family members with serious illness and dementia” whom she cared for and that she could not have engaged in study in any other way (Stone and O’Shea, 2019a, p. 102). Another caregiver stated that for people with children, online options had “changed the whole ball game of going to university” (Stone and O’Shea, 2019a, p. 102). With regard to workload, the participant narratives indicated a variety of experiences. For some, their HE institutions had provided flexibility regarding workload and assessment; others found navigating their HE institutions to be less supportive (Cass et al., 2009, 2011). The personal, cultural and structural conditions that were identified as mostly enabling for women carers engaging in HE are summarized in Table 4.

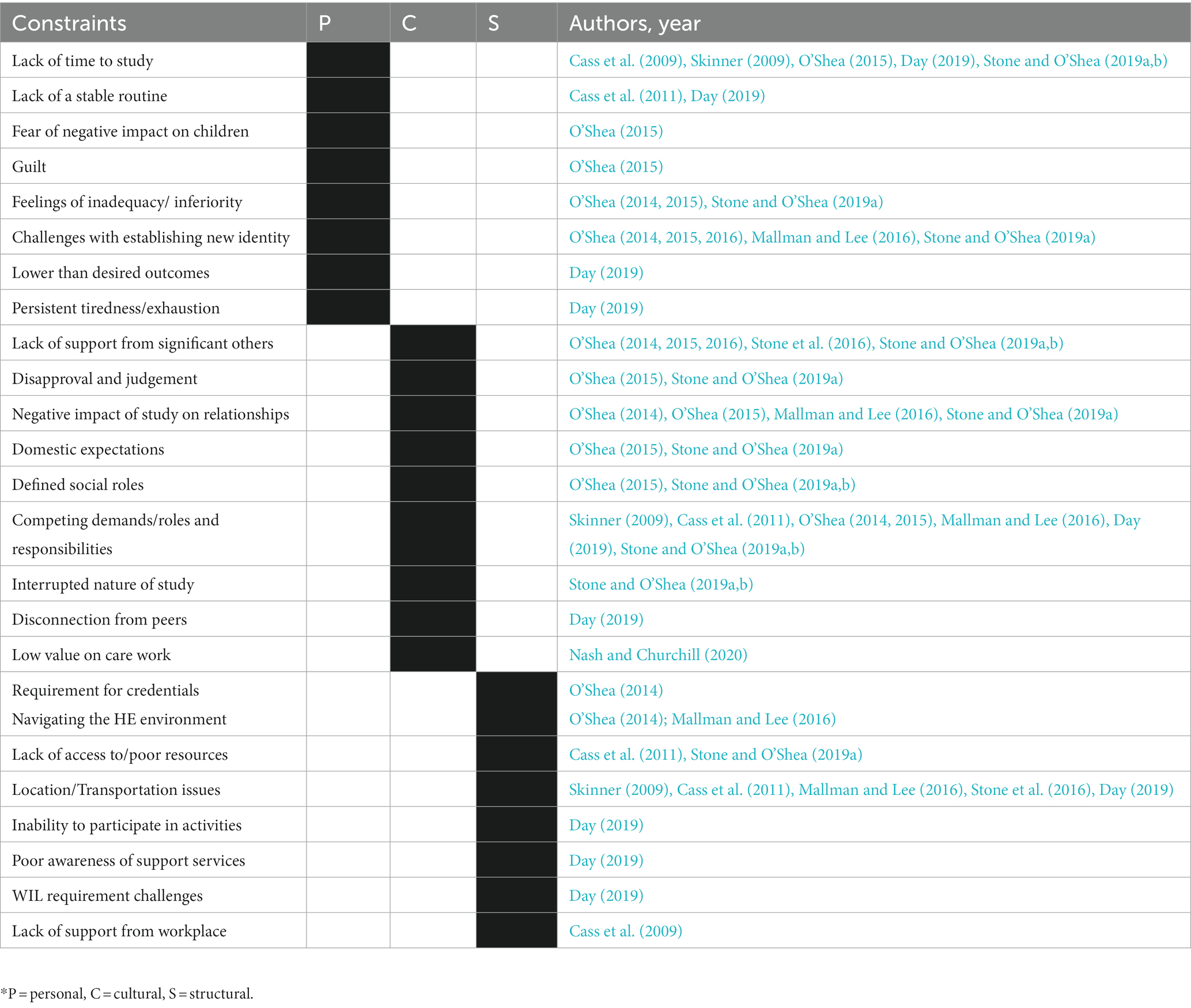

5.3. Influences that can constrain women in study decision making

Constraints may limit or control the degree to which female carers are able to exercise agency regarding HE decisions. A sound understanding of the range of personal, cultural and structural influences (Archer, 2003, 2007, 2012) which individuals may experience as constraining their HE decision-making will enable CDPs, HE providers and researchers to support these women and to consider strategies for overcoming potential barriers.

5.3.1. Personal factors and influences

While there are risks for all mature age students who choose to return to study after a significant period, the literature indicates that there are distinct risks for women, including a risk to their emotional well-being. For carers, the decision to study is fraught with emotions, with guilt frequently associated with the student role. Anecdotes included by several of the participants in the study of Stone and O’Shea’s (2019b) and in O’Shea’s, 2014 study reported feeling guilty and selfish as a result of participating in HE. Participants in Cass et al.’s, 2011 study registered worry, stress and depression, and it was noted in O’Shea’s, 2015 study that women feel anxious that time dedicated to study will come at the cost of time with those they care for and result in a “failure” to fulfil what seven of the articles referred to as domestic responsibilities or domestic labour expectations. In several studies (O’Shea, 2014, 2015; Stone and O’Shea, 2019a,b), participants expressed feelings of inadequacy, inferiority and uncertainty as to whether or not they ‘deserved’ to be a HE student. Concerns about not really belonging in a HE institution were shared and O’Shea observed that women who had not studied for some time may “regard themselves as imposters” (2014, p. 135). The studies highlighted the influential role that emotion may play in constraining women’s decisions about HE study.

The risk which HE study may pose to existing identities has also proven to be a constraint upon women’s decisions. In O’Shea’s, 2015 study, she noted that “the theme of ‘male as breadwinner, female as homemaker’ remains dominant” (p. 253) and in her 2014 study of mature age students, she observed that older women may have “taken up the roles of mother and homemaker” (p. 137). For those women who have primarily seen themselves as homemakers or caregivers, the taking on of a new identity, that of “student,” can pose risks (Mallman and Lee, 2016). This new student identity may have to find its place alongside of several well-established identities, such as wife, mother, daughter, employee, and may “exist in contradiction to the established self” (O’Shea, 2014, p. 138). While the formation of this new identity is important and may contribute to a new sense of self (Stone et al., 2016), it has been noted that there are complexities in trying to establish a new identity – one which brings with it a level of independence and future focus -without compromising the existing caregiver identity which continues to exist in tandem and which continues to matter (O’Shea, 2015, 2016). The process of trying to balance these identities can create context sensitive identities which require persistent juggling that is not only challenging, but emotionally exhausting (O’Shea, 2015, p. 246). A sense of identity can help individuals to make complex decisions, as understanding ‘who you are’ can drive ‘what you do’, therefore challenges to established identities can prove to constrain women’s decisions.

Another tension is carer’s heightened risk of not being able to effectively manage the competing demands on their time (O’Shea, 2015, 2016; Nash and Churchill, 2020). Stone and O’Shea’s study found that “managing the entire family’s responsibilities in addition to their own studies was regarded as quite normal” (2019a, p. 103). The normalised experience of this persistent juggling act was evident in eight of the studies. Carers in the study of Day’s (2019) referenced their constant tiredness and exhaustion. Caring for others made it difficult for caregivers to establish a routine conducive to regular attendance at classes and dedicated periods of time for study. The interrupted nature of study for carers was noted by Stone and O’Shea (2019a); with one participant commenting, “there’s never a normal day in my house … Things are just never constant” (2019, p. 9). Half of the studies referred to the lack of time to study (Cass et al., 2009; Skinner, 2009; O’Shea, 2015; Day, 2019; Stone and O’Shea, 2019a,b) yet the need for women to have to justify the time they did spend studying was also noted (Stone and O’Shea, 2019a). Day (2019) observed that carer responsibilities could influence carers’ studies to a degree where they felt they were not achieving to their potential and were receiving lower than desired results. O’Shea (2015, 2016) also found that women fear that engagement in study poses a high risk of failure, a perception that tends to be reinforced by unsupportive family members and friends. Anticipation of the juggle may be sufficient to deter a woman from enrolling without recognising the normalized expectations at the root of the dilemma.

5.3.2. Cultural factors and influences

Recent Australian studies have highlighted the gendered nature of HE experiences, including the enduring social identification of women as carers and men as providers (O’Shea, 2015). This persistent view of women as carers has proven “resistant to change” (Stone and O’Shea, 2019a, p. 99), with many women acknowledging that the onus is on them alone to figure out how to incorporate tertiary studies without negatively impacting on homelife (Stone and O’Shea, 2019a). As O’Shea reflected, women “bear the primary responsibility for making [HE study] work, the tacit permission of partners relying on their ability to maintain a ‘balance’, which actually meant the need to guarantee little intrusion or interruption within the domestic space” (2015, p. 253). A recurrent theme throughout the interviews with female caregivers was that of men openly expressing their concern about how their partner’s move into HE would impact upon them (O’Shea, 2015), indicating the ways in which persistent societal views of women’s’ roles may prove to constrain HE study decisions.

As it is women who still primarily bear the responsibility for caregiving and thus the organisation of family timetables and interactions, it is women who are most at risk of being blamed for disruption to existing family and social networks (O’Shea, 2014, 2015; Mallman and Lee, 2016; Stone and O’Shea, 2019a). A return to study can also lead to conflicts within relationships, as not all significant others (partners and/or family members and friends) will be supportive of this endeavour. It has been noted that significant others may be disapproving of (O’Shea, 2015) and resistant to HE enrolment (O’Shea, 2014) and in fact “hinder” a return to study (O’Shea, 2016). For women who are juggling the roles of carer and breadwinner, there are risks that “… returning to education will be perceived as a ‘selfish’ act resulting in possible ‘suffering’ for dependents” (O’Shea, 2016, p. 36), and which can result in judgement (Stone and O’Shea, 2019a). O’Shea has noted that “becoming a student challenges existing feminine identity positions that embrace the ideologies of (hetero) sexuality, maternalism, and domesticity. The learner identity may threaten the mother identity, as it is perceived as “outside” the ideology of the feminine” (2015, p. 246). Therefore, the negative reactions can be understood in reference to the “clearly defined social and gender roles that … women [are] expected to adopt” (O’Shea, 2015, p. 251). Some will attempt compromises and a renegotiation of domestic duties, moves which are “not typically embraced or welcomed by many of the partners” (O’Shea, 2014, p. 148). For other women, it may require an acceptance that support will not be forthcoming and that they must draw on inner resources such as self-determination to pursue their dreams of HE studies (O’Shea, 2014). While social influences can enable women to commence and persist with the pursuit of HE studies, they can just as easily constrain their decisions and ability to do so.

In several of the studies (Stone et al., 2016; Stone and O’Shea, 2019a; Stone and O’Shea, 2019b), participants referred to the importance of fellow student support. According to Mallman and Lee (2016), mature-age students will “select universities they feel are for people like them” as “friendship and community cohorts play a large part in one’s ability to imagine a place for oneself at university” (p. 697). However, it can be difficult for prospective students who are carers to identify whether particular universities are “for people like them.” Universities do not generally collect or publish data on student carers, perhaps because student carers are not one of the identified groups in the annual HE statistics each university must report to the Government. In their 2021 report, Supporting carers to succeed in Australian Higher Education, Andrewartha and Harvey noted that

a major barrier to increased support for student carers was the lack of data collection at the institutional, state, and national levels. Without reliable data, the size and nature of the student carer population remains undetermined and there is no empirical evidence of access, success, or outcomes for this group. It would be beneficial to be able to systematically identify carers at application or enrolment (p. 1).

The majority of universities publish no information online which has been specifically designed for current or prospective student carers. The provision of such information may serve to reassure or carers that there are other caregivers undertaking study, and that peer support with people in similar situations may be found.

5.3.3. Structural factors and influences

Female caregivers are presented with a broad range of structural barriers which may constrain their decisions about HE study including the gendered division of labour regarding care work. Recognition that women work a “second shift” of family care work after a day of paid work has been in evidence since the 1980s (Nash and Churchill, 2020). Caregiver responsibilities do not evaporate upon enrolment into a program of study. For caregivers, periods of learning must be worked around caring responsibilities and will frequently be disrupted by these (O’Shea, 2015). This cohort are “… unable to enact the student role in the ways expected by university discourses (O’Shea, 2015, p. 255) as there is an enduring view within tertiary education institutions of students as independent, unencumbered learners (O’Shea, 2015; Nash and Churchill, 2020). Consequently, female carers are generally unable to engage in dedicated and uninterrupted periods of study and may view any difficulties which they experience with their studies as a failure on their own part, as opposed to the result of system which lacks the support structures which would facilitate their success (Day, 2019). Nash and Churchill (2020) have already raised the important point that “… the gendered inequalities associated with caring and paid work are collective and structural” (p. 834). The continued idealisation of the independent learner perpetuates a set of beliefs about students and their situations that works against female caregivers rather than support them. The dominant ideology privileges unencumbered students and absolves educational institutions of a responsibility to address the underlying structures which can undermine female carer’s educational pursuits (Churchill, 2020). Furthermore, these existing structures would seem to legitimise these gendered inequalities, thereby rendering them invisible and making it difficult to both identify and challenge them.

Further exacerbating the challenges females caregivers face when deliberating about HE enrolment is that universities are not gender-neutral, rather they “… ascribe roles and identity positions that are based on deeply embedded assumptions about men and women as well as masculinity and femininity” and that these gendered assumptions about the student role are more based on a masculine ideal “that is not distracted or defined by domestic responsibilities, poverty or self-doubt” (O’Shea, 2015, p. 254). This fact can present female caregivers with hidden obstacles which may impact negatively upon their studies and “responsibilise women for their academic success” (Nash and Churchill, 2020, p. 834). Neoliberal ideology promotes the notion that talent, hard work and dedication to this work will be rewarded and is a notion that Berlant (in Nash and Churchill, 2020, p. 835) terms “cruelly optimistic.” “Cruelly,” because the research highlights the fact that there are many talented women in the academic realm who are consistent and committed employees, but also caregivers and who find that they do not have the same opportunities to succeed that their male counterparts do.

In other words, even though women remain the primary caregivers, they are continually judged in ‘modalities of academic masculinity’ in which research success is premised on a strong career drive and the prioritization of organizational commitments over relational ties to children, parents and other family members (Nash and Churchill, 2020, p. 835).

Mallman and Lee (2016), Day (2019), and Stone and O’Shea (2019a,b) and all referenced structural barriers such as inflexible and unsuitable timetables, mandatory attendance requirements, inflexible due dates for assessment tasks and insufficient information provided to these learners. One participant in Cass et al.’s, 2011 study stated that “if you did not fit into the system, then you could not participate in the system” (p. 83). The study of Day’s (2019) highlighted the fact that for many carers, attendance at scheduled classes was challenging enough; participation in non-scheduled class activities such as collaborative and peer-assisted learning activities, was rarely possible. This can exacerbate feelings of ‘disconnection’ from peers (Day, 2019), an important element in the building of a student identity (Mallman and Lee, 2016). Further, it highlights the point that decision making is an interconnected challenge in that issues of cohort disconnection are social, but caused by a lack of flexibility, support and understanding at an organizational level.

Additional structural constraints noted by study participants included a lack of access to or poor resources, including poor internet and access to library services (Cass et al., 2011; Stone and O’Shea, 2019a). Transportation issues faced by carers were noted in five of the studies (Skinner, 2009; Cass et al., 2011; Mallman and Lee, 2016; Stone et al., 2016; Day, 2019) and Day noted that where support services for non-traditional students are available, universities have not put in place the systems to effectively communicate their availability to students. Further, HE bureaucracy can present challenges, with O’Shea (2014) and Mallman and Lee (2016) noting the complexities that many learners face when attempting to navigate an unfamiliar bureaucratic HE environment. Inflexible placement and WIL requirements can present an additional barrier to prospective student carers who may baulk at enrolment in a course of study which will require the making of alternate care arrangements, which may not always be possible (Day, 2019). The literature suggests that HE institutions have a role to play in addressing their own gendered nature and prohibitive systems and processes, and that they should be advocates and agents of positive change for members of non-traditional cohorts. While traditional notions of the “ideal student” have served HE institutional interests well, this antiquated view of what it is to be a student results in organisational systems and structures which constrain the decisions that carers make about study (Table 5).

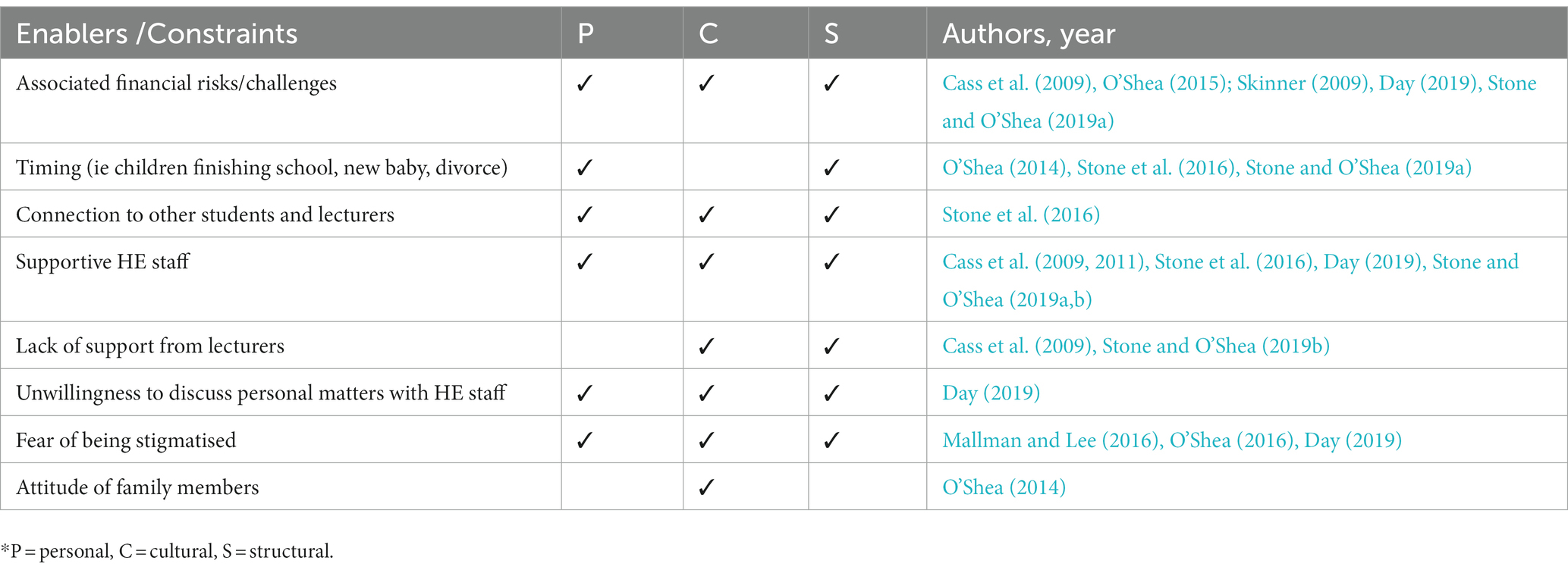

5.4. Context sensitive influences: Those which both enable and constrain women’s study decisions

While many of the factors and influences which have been noted in the literature can readily be designated as enabling or constraining there remain those which may both enable and constrain women’s decisions about HE study. Furthermore, these factors and influences may fit more than one of the “personal,” “cultural” or “structural” categories which have been discussed.

5.4.1. Financial factors and credentialisation

Financial factors may be considered as a positive motivator which can enable women’s decisions to enrol in HE study. Financial considerations for HE studies featured as personal motivators in vignettes of O’Shea’s (2015), including women’s desire to provide a more financially secure future for themselves and their families. This desire was also reflected in Stone and O’Shea’s later studies (Stone et al., 2016; Stone and O’Shea, 2019a). Stone and O’Shea (2019b) noted the importance of study in terms of its potential to help women to re-enter the employment market, secure or improve their employment and wage options and to better their children’s lives. Enrolment in HE studies as a means to enhance job prospects was noted in four studies (Skinner, 2009; O’Shea, 2015; Stone et al., 2016; Stone and O’Shea, 2019a). For other women, a desire to “earn my own way,” as opposed to relying on government benefits was expressed (O’Shea, 2016). O’Shea (2014) observes that pursuing HE study is a necessity for many women who must “maintain economic viability” following life events such as divorce and separation (p. 137). In this way, financial considerations may be viewed as personal enablers as they may motivate women to pursue HE studies.

Financial factors may also constrain women’s decisions to enrol in HE study. The financial cost of study is high, and prospective students may feel concern about the debt which such a course of action will incur (O’Shea, 2016). This can prove to be prohibitive and to deter women from enrolment into HE studies. Financial factors may be considered as personal enablers or constraints as they relate to notions of personal identity which are inclusive of women’s beliefs, worldviews and abilities to provide for themselves and their families. They may also be considered as cultural enablers or constraints. Stone and O’Shea (2019b) noted the powerful societal perception of education as an indicator of achievement. This perception may act as a cultural enabler, particularly for women with a desire to “prove” themselves (O’Shea, 2015; Stone and O’Shea, 2019b). Financial factors may also be considered as structural enablers or constraints. While personal beliefs about the importance of financial security may serve to enable women to commit to HE studies, as participants in O’Shea’s studies noted, some families raised financial burdens as a concern. For mature age learners, return to study may bring the fear that failure would financially burden their families. University debts are structural, with organisations – most often governments, determining the nature and form of these. However, it is worth noting that debts are frequently framed as ‘personal’ issues. They therefore serve to reinforce and maintain structural systems which may impose a penalty (Nash and Churchill, 2020) on women who have taken time out of the workforce for care of others.

Likewise, the increasing “credentialisation of the workforce” (O’Shea, 2014, p. 137) may be viewed as a structural enabler or constraint. Structural requirements for recency of formal qualifications may motivate and thereby enable women to pursue HE study, but these may also be viewed as symptomatic of an ingrained and systemic failure to recognise in any meaningful way the broad array of experiential capital that care work may bring to an individual (Stone and O’Shea, 2019b). It is important for women to be able to recognise these influences on their decision making so the impact of them may be understood in practice.

5.4.2. Timing

Timing is frequently regarded as an enabler of women’s HE studies. In three studies (O’Shea, 2014; Stone et al., 2016; Stone and O’Shea, 2019a) it was noted that for many women, deliberations about study are precipitated by a significant life event or change of circumstances, such as the dissolution of a relationship, the arrival of a baby, diagnosis of a chronic illness in a significant other or a traumatic event. These events and circumstances are generally regarded as ‘personal’, however a view could be taken that events such as the birth of a child is actually a cultural condition, as prevailing societal expectations are for women to put their careers on hold when a baby arrives. Similarly, prevailing societal expectations are for women to take up the role of carer in cases where significant others become chronically ill or experience an incident which requires them to be cared for. Likewise, it may be regarded as a structural condition, as the lack of effective policies and supports to ensure that women are able to continue without a career interruption, ‘enable’ women to study by virtue of a forced career break. While flexibility is desirable, these examples highlight the fact that decision making is responsive to a range of conditions and must be understood within these broad contexts and the context of career.

5.4.3. He staff support

In half of the studies considered, carers indicated that they had found support from HE staff and fellow students to be a cultural enabler for their studies (Cass et al., 2009, 2011; Stone et al., 2016; Day, 2019; Stone and O’Shea, 2019a,b). Others indicated a personal constraint of a discomfort or unwillingness to contact lecturers to discuss their situations, sometimes for fear of being stigmatised (Mallman and Lee, 2016; O’Shea, 2016; Day, 2019), which could be viewed as a personal or a cultural constraint. Participants in Cass et al. (2009) and Stone and O’Shea’s (2019b) studies suggested that there had been a lack of support from their lecturers, which could be viewed as a cultural constraint. This lack of support could also be considered a structural constraint. If the prevailing attitude within a HE institution is that the student will ‘fit’ the institution (O’Shea, 2014) and if there is a failure to understand the distinct needs of students who are carers (Stone and O’Shea, 2019a, 2019b), then it is unlikely that the institution will have in place the systems, practices and resources which will encourage prospective carers to commence HE studies or to thrive (Table 6).

6. Discussion

The global gender inequalities which continue to impact on women’s career journeys include inequalities in the distribution of care work. Even though women now outnumber men in HE enrolments, this scoping review, in answering Research Question 1 about the scope of the field, has demonstrated that there is very little research in Australia that has focussed specifically on how the disproportionate share of care work which is born by women influences their decisions to pursue HE study and their capacity to achieve to their full potential. The participants in the included research articles discerned a broad range of personal, cultural and structural influences which enabled their decisions to study a HE degree. However, the participants also discerned a broad range of personal, cultural and structural influences which constrained their deliberations. Furthermore, a number of influences were demonstrated to both enable and constrain women’s deliberations and decisions, according to the individual and her specific context. This finding highlights the fact that women are not a homogenous group. Acker (1994) (in O’Shea, 2015, p. 244) argues that

educational research should treat women as a discrete group without losing sight “of the diversity of women and the dangers of generalization”. Hence women should not be solely bracketed by gender but instead recognised as unique social beings that are similarly dealing with gendered positions, such as the role of caregiver.

Carers likewise will experience the practical effects of care work and the broad array of factors which influence their HE study decisions. The summary tables provide some guidance for career practitioners. However, in answering the additional research questions through this scoping study there are some clear areas of focus where future research work may facilitate greater support for women (RQ1.3).

Firstly, the concept of care has primarily been considered through a perspective that focusses on who is cared for and on the types of care that are provided. Such a categorical approach does not easily enable the examination of conditions that are shared across categories or consider that women may have several types of carer roles. Alternatively, analysing the conditions in terms of enabling and constraining influences, demonstrates that there is often an interplay of personal, cultural and structural influences when women are asked about their experiences of HE studies and care work. Attention to how the concept of care is defined has implications for women in terms of the visibility of care work and the respect which this is accorded socially and organizationally. Prevailing conceptualisations of care work impact upon the support which female carers are able to access as HE students and the lack thereof may critically influence decisions that are made regarding enrolment. Further research about the intersections of care work, as well as attention to definitions in ongoing studies will be of benefit to the field.

Secondly, while notable research work has occurred in relation to carers and HE study in Australia and internationally (Lyonette et al., 2015; Kettell, 2020; Lynch et al., 2020), gaps in the literature regarding the decision-making processes that women undertake prior to their enrolment in HE studies remain. The pre-enrolment stage has not yet been the focus of study in an Australian context and was not evident in a scan of international literature. Nor have the changes that may occur in carer’s HE deliberations over time, or the conception of decision making as more than an individual and rational approach been a focus of study. Yet practitioners who work with clients who are considering HE studies would be highly aware of the ways in which contexts, emotions and relationships can influence deliberations and an ultimate decision. Research that considers more situated career decision-making processes are needed to generate deeper understandings of the ways women deliberate about HE study. Additional decision-making theories are needed to encompass common career counselling situations where female carers with ostensibly similar situations can deliberate and draw different but personally appropriate conclusions.

Finally, the importance of structural conditions that influence how women experience a broad range of enablers and constraints were made visible. As Mallman and Lee (2016) highlighted, “the ideal learner, from an institutional view, is young, well-resourced and not bound by conflicting family obligations; in other words, able to build their life entirely around the ‘greedy institutions’ of HE (p. 686). This scoping study has demonstrated that while female carers may face numerous barriers which inhibit an “ideal learner” identity, HE institutions contribute to the challenges through the imposition of structural obstacles, both tangibly and ideologically. This scoping review points a relatively new area of research with regard to the decision-making processes female carers undergo prior to enrolment in HE programs of study. This research could inform policies and approaches which will enable females to pursue HE study, and new areas of action for HE institutions and CDPs regarding the provision of support as they make the decisions to do so.

7. Conclusion

This scoping review focused on experiences of women in Australia as career decisions are among the most important that individuals will make for themselves, their dependants and significant others and they are context dependent. The paucity of research about female carers in Australian literature is similarly hard to find in international contexts. Further, it is well acknowledged that this is a cohort to whom little attention has been paid and whose work is undervalued.

This scoping review has revealed insights into the factors and influences which are enabling or constraining women’s decisions as they deliberate about enrolment in HE study. The literature review has also pointed to gendered aspects to caring which impact on women not only as they study but as they work through the initial decision of whether or not to pursue HE studies. Neoliberal HE structures and approaches are leading to a reinforcement of gender stereotypes which disadvantage women, and a continuation of the current gender segregation of the Australian workforce. These responses are constraining female carers’ decisions regarding HE study and their ability to succeed once a commitment to study has been made. This scoping review has highlighted the fact that despite the ostensibly positive enrolment figures, a broad range of issues perpetuate the inequalities that continue to negatively influence female carer’s enrolment into HE study.

Career development practitioners, high school teachers and university lecturers are well positioned to address these issues. There has long been a social justice aspect to the work of educators and counsellors. Helping individuals to consider the enablers and constraints which may be influencing their HE study decisions is an important aspect of work with this cohort. However, to date, too little attention has been given to female carers’ narratives. The issue of care work and its influence on educational decision-making processes is one which requires urgent attention, and collaborative and strategic responses. Research which investigates these processes is needed and HE institutions and policy makers must draw on this research and recognise care in a way that better reflects how students experience it” (Alsop et al., 2008, p. 624). As the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated, global issues may rapidly change the composition and expectations of the workforce and may also influence the decisions that women with caring responsibilities make about HE. Future research work regarding female carers as prospective HE students could lead to further understandings of the enablers and constraints that are factoring into their decision-making processes and equip those who work with these cohorts to better support women as they deliberate about enrolment into HE study.

Author contributions

DM: conceptualization, methodology, writing – original draft preparation, and reviewing and editing. JW, AG, and ML: conceptualization, methodology, and reviewing and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acker, S. (1994). Gendered education-sociological reflections on women, teaching and feminism. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Aarntzen, L., Derks, B., van Steenbergen, E., Ryan, M., and van der Lippe, T. (2019). Work-family guilt as a straightjacket. An interview and diary study on consequences of mothers’ work-family guilt. J. Vocat. Behav. 115:103336:103336. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2019.103336

Alburez-Gutierrez, D., Mason, C., and Zagheni, E. (2021). The “Sandwich generation” revisited: global demographic drivers of care time demands. Popul. Dev. Rev. 47, 997–1023. doi: 10.1111/padr.12436

Alsop, R., Gonzalez-Arnal, S., and Kilkey, M. (2008). The widening participation agenda: the marginal place of care. Gend. Educ. 20, 623–637. doi: 10.1080/09540250802215235

Andrewartha, L., and Harvey, A. (2021). Supporting carers to succeed in Australian higher education. Report for the National Centre for student equity in higher education, Curtin University. Melbourne: Centre for Higher Education Equity and Diversity Research, La Trobe University.

Archer, M. S. (2003). Structure, agency, and the internal conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Archer, M. S. (2007). Making our way through the world: Human reflexivity and social mobility. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Archer, M. S. (2012). The reflexive imperative in late modernity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2019). Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings. Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/disability/disability-ageing-and-carers-australia-summary-findings/latest-release (Accessed January 17, 2022).

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2020). Education and work, Australia. Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/education/education-and-work-australia/may-2020 (Accessed January 17, 2022).

Australian Government (2021a). Study Assist. Available at: https://www.studyassist.gov.au/wAustraliay/australia (Accessed January 17, 2022).

Australian Government (2021b). Services Australia. Available at: https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/most-viewed-payments-for-higher-education?type%5Bvalue%5D%5Bpayment_service%5D=payment_service (Accessed January 11, 2022).

Australian Government Department of Education, Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (2020). 2020 section 11 equity groups. Available at: https://www.dese.gov.au/higher-education-statistics/resources/2020-section-11-equity-groups (Accessed January 27, 2022).

Australian Government Department of Education, Skills and Employment (2021). Undergraduate applications, offers and acceptances 2021. Available at: https://www.dese.gov.au/higher-education-statistics/resources/undergraduate-applications-offers-and-acceptances-2021 (Accessed January 18, 2022).

Australian Government Department of Health (2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19) – Information for residential respite providers. Available at: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/06/coronavirus-covid-19-information-for-residential-respite-providers.pdf (Accessed January 17, 2022).

Australian Government Workplace Gender Equality Agency (2016). Unpaid care work and the labour market. Available at: https://www.wgea.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/australian-unpaid-care-work-and-the-labour-market.pdf (Accessed January 25, 2022).

Australian Human Rights Commission (2008). Women’s human rights: United Nations convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women. Available at: https://discrimination/publications/women-s-human-rights-united-nations-convention-elimination#Heading192 (Accessed January 17, 2022).

Australian Human Rights Commission (2013). Investing in care: Recognising and valuing those who care. Volume 1, Research Report, Australian Human Rights Commission, Sydney.

Bahn, K., Cohen, J., and Meulen Rodgers, Y. (2020). A feminist perspective on COVID-19 and the value of care work globally. Gend. Work. Organ. 27, 695–699. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12459

Bainbridge,, and Broady, T. R. (2017). Caregiving responsibilities for a child, spouse or parent: the impact of care recipient independence on employee well-being. J. Vocat. Behav. 101, 57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.04.006

Baker, Z. (2019). Reflexivity, structure and agency: using reflexivity to understand further education students’ higher education decision-making and choices. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 40, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2018.1483820

Berik, G. (2018). To measure and to narrate: paths toward a sustainable future. Fem. Econ. 24, 136–159. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2018.1458203

Bimrose, J. (2019). “Guidance for girls and women” in International handbook of career guidance. eds. J. Athanasou and H. Perera. 2nd Edn. (Springer International Publishing), 385–412.

Bimrose, J., McMahon, M., and Watson, M. (2015). Women’s career development throughout the lifespan: An international exploration. London: Routledge.

Bimrose, J., McMahon, M., and Watson, M. (2019). “Women and social justice: does career guidance have a role?” in Career guidance for emancipation: Reclaiming justice for the multitude. ed. T. Hooley (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Frances Group)

Blustein, D. L. (2015). “Implications for career theory” in Women’s career development throughout the lifespan. eds. J. Bimrose, M. McMahon, and M. Watson (Routledge), 219–230.

Blustein, D. L. (2017). “Integrating theory, research and practice: lessons learned from the evolution of vocational psychology” in Integrating theory, research and practice in vocational psychology: Current status and future directions. eds. J. P. SampsonJr., E. Bullock-Yowell, V. C. Dozier, D. S. Osborn, and J. G. Lenz (Florida State University Libraries), 179–187.

Caputo, J., Pavalko, E. K., and Hardy, M. A. (2016). The long-term effects of caregiving on Women’s health and mortality. J. Marriage Fam. 78, 1382–1398. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12332

Carer Respite Alliance (2021). Repositioning respite within consumer directed service systems. Available at: https://www.carersnsw.org.au/uploads/main/Files/5.About-us/News/Repositioning-respite-within-consumer-directed-service-systems.pdf (Accessed January 17, 2022).

Cass, B., Brennan, D, Thomson, C, Hill, T, Purcal, C, Hamilton, M, et al. (2011) Young carers: Social policy impacts of the caring responsibilities of children and young adults. [report prepared for ARC linkage partners] October 201

Cass, B., Smith, C., Hill, T., Blaxland, M., and Hamilton, M. (2009). Young Carers in Australia: Understanding the advantages and disadvantages of their care giving FaHCSIA social policy research paper no. 38. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1703262 (Accessed December 15, 2021).

Churchill, B. (2020). No one escaped COVID’s impacts, but big fall in tertiary enrolments was 80% women. Why? The conversation. Available at: https://theconversation.com/no-one-escaped-covids-impacts-but-big-fall-in-tertiary-enrolments-was-80-women-why-149994 (Accessed December 15, 2022).

Coffey, C., Espinoza Revollo, P., Harvey, R., Lawson, M., Parvex Butt, A., Piaget, K., et al. (2020). Time to care: Unpaid and underpaid care work and the global inequality crisis. Oxford: Oxfam GB for Oxfam International

Commonwealth of Australia (2014). Report of the Australian government delegation to the 58th session of the United Nations: Commission on the status of women. Tuesday, 11 March. Available at: https://www.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/CSW58_australian_delegation_report.pdf (Accessed January 11, 2022).

Craig, L., and Churchill, B. (2021). Working and caring at home: gender differences in the effects of Covid-19 on paid and unpaid labor in Australia. Fem. Econ. 27, 310–326. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2020.1831039

Day, C. (2019). An empirical case study of young adult carers’ engagement and success in higher education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 25, 1597–1615. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1624843

DeRock, D. (2021). Hidden in plain sight: unpaid household services and the politics of GDP measurement. New Pol. Eco. 26, 20–35. doi: 10.1080/13563467.2019.1680964

Do, Cohen, S. A., & Brown, M. J. (2014). Socioeconomic and demographic factors modify the association between informal caregiving and health in the Sandwich generation. BMC Public Health, 14:362. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-362

Doherty, C., and Lassig, C. (2013). “Workable solutions: the intersubjective careers of women with families” in Conceptualising women’s working lives moving the boundaries of discourse. ed. W. Patton (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers), 83–103.

Douglas, J. (2020). Number of Melbourne families providing palliative care at home soars under coronavirus lockdown. ABC News. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-09-24/number-of-people-dying-at-home-surges-in-lockdown/12681140 (Accessed January 28, 2022).

Economic Security for Women (2019). White paper: The impact of unpaid care work on women’s economic security in Australia. Available at: https://www.security4women.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/eS4W-White-Paper-Carer-Economy_20191101.pdf (Accessed January 14, 2022).

Education Services Australia (2022). Alternative pathways to higher education. My Future. Available at: https://myfuture.edu.au/career-articles/details/alternative-pathways-to-higher-education (Accessed February 3, 2022).

Esteban, O., Sandra, T., and Max, R. (2018). Women’s employment. Our World in Data. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/female-labor-supply (Accessed December 15, 2021).

Fisher, B., and Tronto, J. (1990). Toward a feminist theory of caring. Circles of care: Work and identity in women’s lives, 35–62.

Gammage, S., Sultana, N., and Mouron, M. (2019). The hidden costs of unpaid caregiving. Fin. Dev. 56, 21–23.

Grant-Smith, D., Irmer, B., and Mayes, R. (2020). Equity in postgraduate education in Australia: widening participation or widening the gap? National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education Report. Available at: https://www.ncsehe.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/GrantSmith_2020_FINAL_Web.pdf (Accessed December 7, 2021).

International Alliance of Carer Organisations (2021). Global state of caring. Available at: https://internationalcarers.org/wp_content/uploads/2021/07/IACO-Global-State-of-Caring-July-13.pdf (Accessed January 17, 2022).

Irfan, O., Ansari, A., Qidwai, W., and Nanji, K. (2017). Impact of caregiving on various aspects of the lives of caregivers. Curēus 9:e1213. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1213

Kavanaugh,, and Stamatopoulos, V. (2021). Young Carers, the overlooked caregiving population: introduction to a special issue. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 38, 487–489. doi: 10.1007/s10560-021-00797-2

Kearney,, Stanley, G., and Blackberry, G. (2018). Interpreting the first-year experience of a non-traditional student: a case study. Stud. Success 9, 13–23. doi: 10.5204/ssj.v9i3.463

Kettell., (2020). Young adult carers in higher education: the motivations, barriers and challenges involved - a UK study. J. Furth. High. Educ. 44, 100–112. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2018.1515427

Lynch, K., Ivancheva, M., O’Flynn, M., Keating, K., and O’Connor, M. (2020). The care ceiling in higher education. Irish Educ. Stud. 39, 157–174. doi: 10.1080/03323315.2020.1734044

Lyonette, C., Atfield, G., Behle, H., and Gambin, L. (2015). Tracking student mothers’ higher education participation and early career outcomes over time: initial choices and aspirations, HE experiences and career destinations. Institute for Employment Research, University of Warwick Coventry CV4 7AL.

Mallman, M., and Lee, H. (2016). Stigmatised learners: mature-age students negotiating university culture. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 37, 684–701. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2014.973017

McCall,, Western, D., and Petrakis, M. (2020). Opportunities for change: what factors influence non-traditional students to enrol in higher education? Aust. J. Adult Learn. 60, 89–112.

McMahon, M. (2019). Does theory matter to the practice of career development? CareerWise. Available at: https://careerwise.ceric.ca/2019/02/08/does-theory-matter-to-the-practice-of-career-development/#.YQNw544za9J

Munn, Z., Peters, M., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., Mcarthur, A., and Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 18:143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Naicker, I., Grant, C. C., and Pillay, S. S. (2016). Schools performing against the odds: Enablements and constraints to school leadership practice. S. Afr. J. Educ. 40, 1–11. doi: 10.15700/saje.v40n4a2036

Nash, M., and Churchill, B. (2020). Caring during COVID-19: a gendered analysis of Australian university responses to managing remote working and caring responsibilities. Gend. Work. Organ. 27, 833–846. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12484

O’Shea, S. (2014). Transitions and turning points: how first in family female students story their transition to university and student identity formation. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 27, 135–158. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2013.771226

O’Shea, S. (2015). “I generally say I am a mum first … But I’m studying at Uni”: the narratives of first-in-family, female carers transitioning into an Australian university. J. Div. HE 8, 243–257. doi: 10.1037/a0038996