- Department of Teacher Education, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland

In Finland, graduating teachers are expected to become “transformational agents” who are able to critically reflect upon and evaluate what types of changes are necessary in education and who can also implement the required changes. However, based on previous studies, teacher education seems to have little influence on future teachers’ core perceptions of teacher’s work. Instead, previous studies have demonstrated that new teachers’ perceptions might draw on tradition and cultural-historical phases of the Finnish teacher profession, and normative ideas concerning the ideal characteristics of a “good” teacher or student teacher. In this study, we examine how student teachers’ perceptions of teacherhood build upon and who has the power to define the “ideal teacher.” Based on our study, we suggest that to understand how the perception of the ideal teacher is formed and how teacher education could better influence the transformation of these perceptions, we must consider the unofficial power relations among student teachers. These power relations seem to originate from the hegemonic discourse of the “typical student teacher,” which contains and renews traditional perceptions of teaching and teachers as authorities and experts transmitting subject content knowledge and skills to pupils. This discourse seems to be renewed among student teachers and has more impact on students’ perceptions than the official aims of teacher education. Hence, in our study, the unspoken sociocultural power relations come to light in different ways, in the peer relations between student teachers but also in the students’ conceptions of the teacher educators. We suggest that by unraveling the unofficial power relations in the sociocultural context of teacher education and by focusing on supporting every student teacher’s agency and critical reflection, it is possible to transform the perceptions about the ideal teacher.

1 Introduction

Teachers are highly respected professionals in Finnish society. The MA-level qualification supports the general respect for the teaching profession, which is not a second choice for students, as it is in many other western countries. Although primary and special teacher education programs remain popular among university applicants [see Education Statistics Finland (VAKAVA), 2022], enrollment has decreased in recent years, and studies have demonstrated that an increasing number of teachers are considering changing their professional field early in their careers (Heikonen et al., 2017; Räsänen et al., 2020). Further in the article by TE we refer to the Finnish MA-level teacher education for primary school teachers. In this study, we examine how student teachers’ perceptions of teacherhood build upon and on the question of who holds the power to define the “ideal teacher.” Our primary data consist of thematic interviews with 16 first-year student teachers attending a 5-year degree program in primary school TE at one medium-sized Finnish university. A small amount of additional data, gathered from written self-reflections of four of the interviewed students when they reached their fifth year, was also considered in the analysis. By examining student teachers’ perceptions on teacherhood, we aim to identify themes that have powerful influence in defining the attributes and characteristics of the ideal teacher, according to the students’ thinking. Based on previous studies, the search for the critical potential of TE—and thus the teaching profession—can be enhanced by making visible the process of teacher formation and by examining the actualization of the characteristics and norms associated with the profession. Through research, the definitions and discourses regarding teacherhood can be diversified, thus encouraging teachers to realize their autonomy and agency, with respect to critical societal issues as well, which have traditionally been excluded from the Finnish teaching profession.

Societal and cultural changes, such as growing diversity of students, regional and school segregation, and increasing influence of socioeconomic background on learning outcomes transform the nature of teachers’ work. From a societal point of view, recent concerns have included research findings on increasing inequalities, a decline in learning outcomes, greater segregation between residential areas and schools, and mental health challenges of children and young people [e.g., Bernelius and Kosunen, 2023; Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture, 2023; Juvonen and Toom, 2023; World Health Organization (WHO), 2023]. Problems in schools, teachers’ heavy workload, and burnout are also frequently featured in the media, which raises concerns and triggers public discussion about how difficult it is to work as a teacher.

Finnish universities, including those offering TE programs, have autonomy over their institutions and decisions concerning their curricula and how TE is organized. Legislation prescribes only certain frameworks for the qualifications of different professional groups (e.g., teachers in special education and primary school education). Formally, the contents of TE curricula play a key role in the educational system, equipping future teachers with the skills, attitudes, and knowledge needed in contemporary schools (see Husu and Toom, 2016). In reality, the process is much more complicated, and student teachers construct their perceptions of teacherhood from varied sources of information and also outside TE’s sphere of influence, which might be potentially problematic. However, when systemic changes are needed at either the social or the individual level in the school environment, the focus first shifts to TE. Traditionally, TE has paid attention to the questions and disciplines of didactics, pedagogy, and psychology, but social science, especially sociology, has also been one of the subjects studied in TE. These traditions have roots in the history of schools, which for a long time emphasized “banking” rather than “problem-posing” in education (Männistö et al., 2023), considering schools as institutions where pupils are socialized into the existing norms of the society, and teachers are authorities delivering information to new generations.

In Finland, graduating student teachers are expected to become transformational agents who can critically reflect on and evaluate what types of changes are necessary in education and implement them (Toom and Husu, 2016). According to the Finnish Education Evaluation Centre (2018), the graduating students should be persuasive and creative innovators who are able and willing to develop their own work methods, as well as the school communities (Niemi et al., 2018). Traditional views on teachers as experts who transfer knowledge to new generations are no longer valid (see Simola et al., 2017), and TE is called for to support students in developing critical reflective views regarding teaching. Traditionally perceived in Finland as individualistic and personally experienced, the teaching profession is being extended to become more collaborative, and teachers are expected to develop their work with colleagues and other stakeholders (see Husu and Toom, 2010; Blömeke et al., 2015; Toom and Husu, 2016, p. 17–22). However, transforming teachers’ and student teachers’ perceptions and core assumptions regarding their profession is challenging and time consuming (e.g., Lindén, 2010; Lanas and Kiilakoski, 2013; Lanas and Hautala, 2015; Fornaciari, 2020). Furthermore, research on student teachers’ perceptions of teacherhood has been relatively scarce (see Syrjäläinen et al., 2006b; Räihä, 2010; Säntti, 2010; Juutilainen et al., in peer review).

Based on previous studies (e.g., Britzman, 2003; Furlong, 2013; Androusou and Tsafos, 2018; Fornaciari, 2020), TE might not have great influence on future teachers’ core perceptions of their work. Instead, previous research has demonstrated that new teachers’ perceptions might draw on tradition and cultural-historical phases of the Finnish teaching profession (e.g., Simola et al., 2017; Fornaciari, 2020) and normative ideas about the ideal characteristics of a “good” teacher or student teacher (e.g., Lanas and Kelchtermans, 2015; Juutilainen et al., 2023). In Finland, the unproblematized status of the school and the teacher in the national-cultural narrative has traditionally granted autonomy to teachers, allowing them to rely on their moral compass to guide their professional actions. Additionally, TE as an institution has been relied on to select and educate future teachers who are suitable for society’s needs. Finnish success in international tests, such as PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment), has been considered as providing sufficient evidence that the school system in Finland functions as a whole, with TE as part of it (e.g., Husu and Toom, 2010, p. 2).

2 Cultural and societal framework of the study

2.1 Good teacher competencies

Society sets both explicit and implicit expectations for teachers; teachers’ work is not only defined by the national curricula and current policy aims but also molded by the surrounding culture and norms. Theoretical analyses and empirical studies of teacher competencies and characteristics are abundant. The definition of a good teacher is full of ideals (Kostiainen and Rautiainen, 2011, p. 159). While it is possible to identify common elements across a wide range of studies, there is no agreed, empirically based articulation of a teacher’s core competencies (e.g., Husu and Toom, 2016). According to Pantić and Wubbels (2010), teachers’ professional competence is comprehensively built on four dimensions: values and raising children; understanding and contributing to the development of the educational system; content knowledge, pedagogy, and curriculum; and self-evaluation and professional development.

Teachers’ work has been regarded in diverse ways at different times, with varying priorities and objectives, and teachers’ professional actions reflect the understanding of human nature, knowledge, and learning of their generation. In Finnish society, the expectations for teachers have taken on various emphases in different decades. In the 1970s, good teaching skills were considered central in teacher training. In the 1980s, the role of the teacher as an expert was emphasized. In the 1990s, reflection and an investigative approach were highlighted. In the 21st century, the teacher has been perceived as a societal agent and ethical visionary, actively developing society (Aarnos and Meriläinen, 2007).

In the Finnish context, teachers have always represented not only pedagogical expertise but also the so-called model citizenship, reflecting the educational ideology and the prevailing ethos of society at a particular time. Teachers were expected to demonstrate the integrity of their role in and out of school, to be good role models for their students, and to conform to cooperation, order, and discipline. Educators had to strive for good conduct in all respects. In fact, from a historical point of view Finnish primary school teachers are argued to be rather traditional than critical in their relationship with society. Schools and teachers in Finland have traditionally been perceived as preservers of the status quo rather than agents of change, and teacherhood is still associated with conservative norms and ideals (e.g., Lanas and Kiilakoski, 2013; Lanas and Kelchtermans, 2015; Simola, 2015; Fornaciari and Männistö, 2017; Juvonen and Toom, 2023).

According to current professional thinking, the classroom teacher should have an understanding of the elements outside the classroom (e.g., curriculum level, school system, school and municipal policies) that guide their actions and influence their work, as well as a willingness to influence the social realities outside the classroom (see National Board of Education, 2004, 2014; Niemi et al., 2018; University of Jyväskylä Teacher education Curriculum, 2020). Toom and Hsu (2016, p. 20–22) considers teachers’ societal competence in relation to the aims of TE, which involves strengthening the knowledge, skills, and competencies for teaching and education that a pluralistic and egalitarian society requires of teachers. In Finnish society, the increasing diversity of students’ cultural, social, and economic backgrounds also emphasizes the importance of the ethical and moral nature of teaching (see also Biesta and Burbules, 2003). Contemporary research on schools and teachers, along with administrative documentation, advocates the development of a more active relationship with society (see National Board of Education, 2004, 2014; Niemi et al., 2018; University of Jyväskylä Teacher education Curriculum, 2020). The current generations of students enter TE in a new climate of social debate and with fresh expectations. Societal awareness and critical reflection on societal practices have also emerged as desired qualities among TE applicants (see Mankki and Räihä, 2019; Fornaciari, 2020). The portrait of an ideal teacher is actively produced in academia, such as in TE, and in administrative policy documents; it is also driven by other stakeholders, such as labor and business interests. In current project-based development efforts, the ideal teacherhood is often produced jointly by all these actors.

2.2 Changing society, changing teacherhood?

Finnish society is changing in the broader context of varying everyday realities of schools at national and regional levels. The growing diversity of students, the variety of lifestyles, and pluralism are changing the work of teachers in many ways, also in Finland, even though it lags comparative countries (in Northern Europe) in this development. The Finnish uniform culture, with its ethnic and cultural homogeneity, has been a distinctive feature of Finnish schools. To date, relatively little cultural competence and understanding of (among others) social or demographic changes and their impacts on the school environment have been required of Finnish teachers. As previously noted, the traditional image of the Finnish teaching profession is rather conservative, and Finnish TE has typically attracted fairly like-minded students with relatively similar backgrounds and expectations on the profession (see Syrjäläinen et al., 2006a; Räihä, 2010).

However, accelerating cultural and social changes are slowly changing the nature of teachers’ work, as well as the objectives and the general perspective of their work in Finland. From a societal point of view, the greatest challenges for Finnish schools in the future are related to how they will be able to implement the all-encompassing task of fostering equality of people with diverse backgrounds (e.g., immigrants, socioeconomical status, gender, region). Internationally, the Finnish school system has so far done quite well in terms of educational equality and uniformity (see Bernelius and Huilla, 2021). However, research has shown that among the OECD countries, Finland has the largest literacy gap between migrant and migrant background students and non-migrant students (Helakorpi et al., 2023). Not only do migrant students and students with migrant backgrounds show poorer academic performance, but they are also bullied more in school. Students with migrant backgrounds also have a greater risk of dropping out of school after comprehensive education (Souto, 2020, p. 317–329). Global goals of sustainability education also fail to translate into concrete actions by the time they reach everyday life in Finnish schools (see Mykrä, 2023). Furthermore, Lehtonen’s (2023) study demonstrates that regarding gender and sex education, teacher training, teaching, and the textbooks used in schools are often still heteronormative in Finland, and teachers lack the tools and motivation to resist heteronormative starting points in their work. Indeed, many studies have identified the demand for a societal focus as a significant aspect of teacherhood, with an emphasis on understanding the needs of a changing society and actively contributing to its development (see Syrjäläinen et al., 2006a; Husu and Toom, 2010, 2016; Lanas and Hautala, 2015; Husu and Toom, 2016; Clandinin and Husu, 2017; Fornaciari, 2020).

Although the teaching profession in Finland is highly autonomous and there are no formal external evaluations of teachers’ work, teacherhood is strongly influenced by different social, cultural, and historical ideals and norms (Britzman, 2003; Furlong, 2013; Lanas and Kelchtermans, 2015; Uitto et al., 2015; Fornaciari and Männistö, 2017; Androusou and Tsafos, 2018; Dugas, 2021). Hence it is reasonable to question whether and despite the contemporary TE objectives, administrative policies and guidance and the national primary curriculum have changed the actual practices in terms of school cultures or teachers’ attitudes and societal thinking, among others. Culturally and historically shaped perceptions of teacherhood are socially constructed and reconstructed. Although education paradigms have changed and continue to evolve, perceptions of teacherhood are undergoing slow transformation (Vuorikoski and Räisänen, 2010; Simola, 2015; Fornaciari and Männistö, 2017). Teachers’ defense mechanisms against the changes in their work have also been identified in studies regarding teachers’ professional agency (see Säntti, 2010; Hökkä, 2012; Vähäsantanen, 2013; Fornaciari, 2020).

2.3 Teacher education and student teachers’ perceptions of teacherhood

The current Finnish TE is research based, and its aim is to prepare teachers who will use contemporary research as the basis for their work and thus reform the field to meet the needs of society and children (Toom et al., 2010; Lanas and Kiilakoski, 2013). In addition to the knowledge of and skills in traditional school subjects, the professional skill development of today’s teachers emphasizes mastery of the so-called generic skills, such as interaction, information processing, thinking and reflection, and digital technology skills. Thus, research on teaching and teacherhood also stresses the centrality of guiding students’ learning processes, rather than merely transferring knowledge to them, and the role of the teacher as part of a collaborative, knowledge-creating community (Luukkainen, 2004, p. 16–17; Tynjälä, 2004, p. 175–188; Toom and Husu, 2016) The current TE and research rhetoric call for critical teacherhood with a comprehensive understanding of education (Rautiainen et al., 2014), but there is no consensus on how well contemporary TE actually instills critical societal elements in the educational thinking and teacherhood of future teachers (see Värri, 2007; Kinos et al., 2015; Lanas and Hautala, 2015; Nikkola and Harni, 2015; Fornaciari and Männistö, 2017).

Perceptions of teacherhood refer to collectively internalized, culturally and socially constructed ideas about the nature of the teaching profession and the appropriate personality for the job (e.g., Lanas and Kelchtermans, 2015). Such perceptions are strongly influenced by individuals’ own experiences, as well as the ways in which the people in their homes, immediate social surroundings, and wider social environment discuss and understand teachers and teacherhood (Alsup, 2006; Furlong, 2013; Lanas and Kelchtermans, 2015; Uitto et al., 2015; Androusou and Tsafos, 2018; Dugas, 2021). Almost all aspiring teachers have school experiences and around 13,000 h of classroom observations of the school administration and a teacher’s daily duties are like. Teachers themselves are likely to have expectations of a personally fulfilling career, expectations that have begun to form in their years as students, observing and learning what teachers and school are like (Lortie, 1975; see also Britzman, 2003; Furlong, 2013). Indeed, socialization in teacherhood starts at an early stage, and studies show that teacher training may be viewed by the students as a formal, compulsory step on the way to a vocation whose tasks and ideal profile are defined outside higher education. Juvonen and Toom (2023, p. 121–127) describe this as a two-dimensional expectation setting for teacher work—teaching as a profession defined by society, on one hand, and teacher work perceived by teachers themselves, on the other hand. Cultural expectations of school and normality begin to form in our years as students, and similar to all the other people, teachers, as products of cultural socialization and through their actions, reflect what is viewed as culturally normal. Skills learned through observations and a strong motivation for entering the field of teaching may mean that student teachers are eager to complete their degree efficiently; to this end, adapting to TE, rather than pausing to criticize it, seems logical. Furthermore, Kuusisto and Rissanen’s (2023) study showed that the majority of future teachers set instrumental goals for their work. Through the teaching profession, students sought to find meaning in their lives and to bring economic security to themselves and their families. For many students, the profession had prevalently pedagogical goals of growth and nurturing (see also Fornaciari and Rautiainen, 2020). This poses a challenge for TE, as student teachers have a level of experiential thinking that is difficult to contest in the TE education.

The discrepancy between students’ preconceptions and teacher conceptions aspired for in TE arises in relation to contemporary teacher perceptions, which have been outlined by official documentations by the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture (2016) and rooted also in TE programs. However, TE departments in Finland have great autonomy in how they interpret and implement the official guidelines in their curriculum. It has also been argued that the TE institution as a place where previous thinking and attitudes about learning, the school’s function, and teacherhood are challenged does not fully reflect reality, according to some studies (see Räihä, 2006; Syrjäläinen et al., 2006a; Lanas and Kelchtermans, 2015; Juvonen and Toom, 2023). In TE, the school as a societal structure is insufficiently reflected, although the superficial self-reflection of teachers is emphasized, and some studies have found that the overall impact of TE on the perceptions, attitudes, professional identity, and agency of future primary school teachers is relatively weak, and students’ perceptions do not substantially change during their studies (e.g., Britzman, 2003; Alsup, 2006; Räihä, 2006; Husu and Toom, 2010; Furlong, 2013; Kallas et al., 2013; Lanas and Hautala, 2015; Androusou and Tsafos, 2018; Matikainen et al., 2018; Fornaciari, 2020; Fornaciari et al., 2023; Juvonen and Toom, 2023).

As noted, contemporary perceptions of teacherhood are characterized by notions of the teacher as a multifaceted societal actor, an innovative expert, and a democratic developer of the school and working community (see Blömeke et al., 2015; Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture, 2016; Husu and Toom, 2016; Raiker and Rautiainen, 2019). Therefore, a central task and objective of TE is to train and enable active future professionals to critically analyze and improve their own work, further hone their expertise, raise their students as active citizens, reform education and their school, and thus, contribute to meeting the challenges of modern society (e.g., Toom and Husu, 2016; University of Jyväskylä Teacher education Curriculum, 2020; Metsäpelto et al., 2022; Juvonen and Toom, 2023). However, this kind of TE seems to be in the margins and mainly related to singular development projects instead of manifesting as mainstream TE.

3 Research design

3.1 Data collection

The primary data for this study comprise thematic interviews with 16 first-year student teachers attending a 5-year degree program in primary school TE offered at a Finnish university. The interviews were conducted between February and June 2014 in Finnish. The interviewees were between 18 and 27 years old, with a mean age of 20.5 years. The themes of the interviews focused on the students’ experiences of studying in TE; what they perceived as important in their studies, how they experienced the learning environment and their peer group in TE, and how they perceived themselves as TE students. In addition, the interview themes covered the student’s previous school experiences, their path to teacher education and perceptions of themselves as learners in school. Throughout the interview, the students were encouraged to talk freely about the themes, emphasizing issues that were relevant to them. All interviews were transcribed, which produced a total of 255 pages of transcribed text (Times New Roman, 12-point font size, 1.5 line spacing). The quotations that are cited here to illustrate the data were translated from Finnish to English by the second author, who also conducted the interviews. Additional data were gathered in the autumn of 2017, when the same students were in their fifth year of TE. Four of the students who were interviewed in 2014 wrote a reflective essay about their experiences in TE. They were asked to write freely about their experiences in TE, what they perceived as important in their studies for their future profession, and what they thought and felt about their approaching graduation and starting their teaching career. Each essay was approximately two pages in length. Despite the small amount of these additional data, they shed light on the socially and culturally constructed and shared ways of understanding teaching as reflected in the students’ narratives.

3.2 Master and counter narratives

In this study, we based our analysis on a previous study that used the same data from 16 student teacher interviews, exploring student teachers’ agency in teacher identity construction through master narratives and counter-narratives (Juutilainen et al., in peer review). In the previous study, narrative analysis was applied. Master and counter-narratives can reveal prevailing norms and alternative, sometimes even opposing means to narrate experiences and relationships (e.g., Hyvärinen, 2020; Lueg et al., 2020; see also Heikkilä et al., 2022). Master narratives are understood as culturally expected and accepted courses of events and actions, framing what is interpreted as “normal” or “typical” (Bamberg, 2004; Hyvärinen, 2020). Master narratives are always embedded in certain social and cultural contexts and can be contested and challenged through counter-narratives (Bruner, 1991; Bamberg, 2004; Hyvärinen, 2020).

Based on the narrative inquiry, three narratives were configured (for detailed information, see Juutilainen et al., 2023): the master narrative of sustaining an internalized teacher identity, the counter-narrative of transforming the teacher identity, and the counter-narrative of questioning the teacher identity. The results of Juutilainen et al.’s (2023) study revealed that the most prevalent narrative in the student teachers’ stories—the master narrative of sustained teacher identity—reflected an orientation to and engagement in those aspects of TE that corresponded to the students’ preconceptions of teaching as “practice.” Here, the teacher’s profession was understood mainly through teachers’ practical actions undertaken with their pupils in the classroom. This master narrative seemed to represent a traditional teacher perception, which is more focused on preservation than on change and is strongly affected by the apprenticeship of observation (see Lortie, 1975). In other words, it involves observing teachers’ work from a pupil’s viewpoint and internalizing normative preconceptions of what it means to be a teacher based on childhood experiences and teacher role models, the impact of home discourses, and cultural images and expectations of teachers (see Knowles, 2003; Alsup, 2006; Lanas and Kelchtermans, 2015; Uitto et al., 2015).

The counter-narratives in the study of Juutilainen et al., 2023 acquired their meanings in relation to the master narrative, opposing the established expectations of the latter. The counter-narratives were also present in the data to a considerable yet smaller extent. The counter-narrative of transforming teacher identity illuminated a transformation from students’ preconceptions of teaching, which were somewhat similar to the master narrative, to TE’s institutional, culturally situated narrative of the contemporary teacher. Thus, the teacher perception in this narrative seemed to represent a kind of unquestioned model teacher perception of contemporary TE.

The counter-narrative of questioning the teacher identity (Juutilainen et al., 2023) entailed questioning and a critical stance toward the normative societal master narratives of teaching and learning in school, extending across different contexts and times. This counter-narrative represented a teacher perception that entailed critical reflection on what is at the core of the teacher’s profession. This kind of critical reflection and ability to evaluate and implement the changes that are needed in education is a goal of TE today (see Toom and Husu, 2016). However, this counter-narrative was found only in a few student teachers’ storylines.

3.3 Thematic analysis

Based on Juutilainen et al.’s (2023) results about the narratives and how those illuminated student teachers’ core perceptions of the teaching profession, we wanted to investigate what aspects had the most power in defining “the good teacher” for future professionals in Finland. Based on the prevalence of the master narrative in the data, it seemed that TE might not have the most powerful influence on students’ perceptions; we started to wonder, then what or who had the power to define the ideal teacher? Consequently, we formulated our specific research questions: What is the foundation on which student teachers’ perceptions of teacherhood are built, where is the “ideal teacher” defined, and by whom?

Thus, we explored the data from the 16 student interviews using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006), aiming to identify recurrent themes that seemed powerful in affecting student teachers’ perceptions according to the student teacher narratives. Then, we proceeded to investigate these thematized aspects in relation to the narratives found in the previous study to see if different narratives would correspond to different themes of powerful influences. In this phase, we also included in our analysis the written essay data from the four students. Due to the small amount of this data, we did not aim to make any generalizations on how student teachers’ perceptions evolved during TE. However, these four students, by chance, differed in their narrations in the first-year interviews in such a way that one of them employed mainly the master narrative, two applied mainly the counter-narrative of transformation, and one used the counter-narrative of questioning in her storyline. Thus, we looked for themes influencing the teacher perceptions also from these written essays, as they offered us a glimpse into possible power relations that might affect students’ teacher perceptions even more than the official aims of TE.

The most significant aspect emerged from the essay of the student who had used the counter-narrative of questioning in her interview when she was in her first year of studies. At that time, she already described some unofficial power relations within the peer group and contested some norms of a typical student teacher; nevertheless, she was sure of wanting to become a teacher. However, in her written essay during her fifth year, it became evident that the contradictions among her peers and with respect to the typical student teacher norm had increased during her years of studies; concurrently, she started to have self-doubts, thinking that she was too “non-teacher-like. This observation provides an important insight into what might happen if unofficial power relations were not brought to light in TE. Thus, in the Results section, we consider this finding further regarding the counter-narrative of questioning.

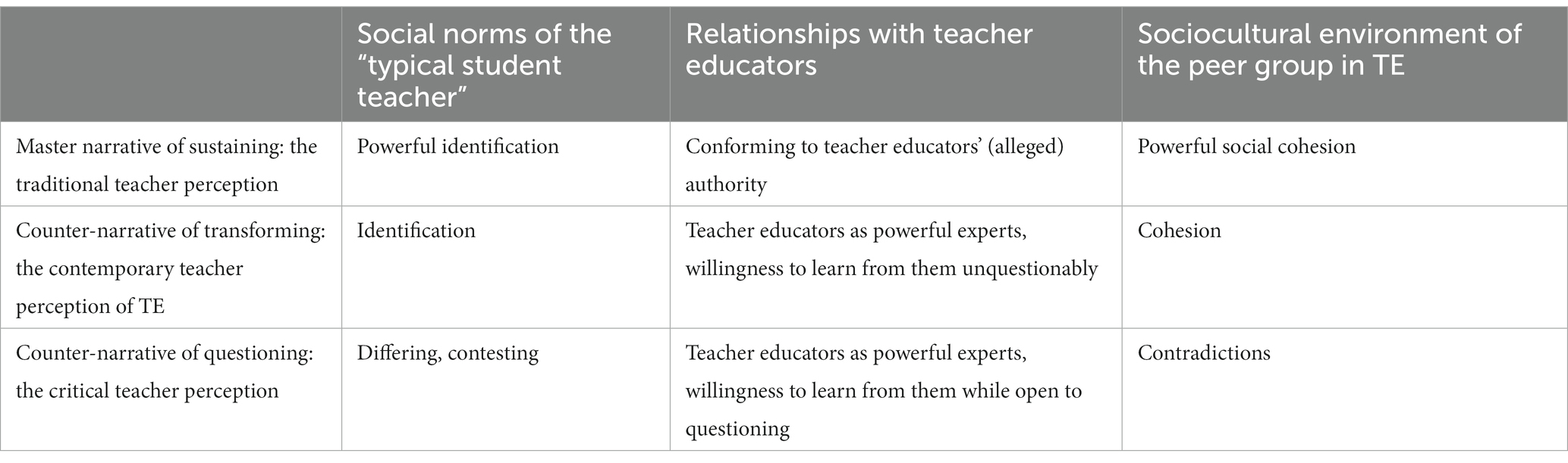

Through our thematic analysis, we found that the themes influencing student teachers’ perceptions of the ideal teacher were the social norms of the “typical student teacher,” the student teachers’ relationships with teacher educators, and the sociocultural environment of the peer group in TE. When these themes were observed concurrently with the master and counter-narratives in Juutilainen et al.’s (2023) study, we found that the effects of these themes differed between master and counter-narratives. Therefore, in the results of this study, we used the three narratives together as a framework to describe how the different powerful aspects influenced student teachers’ perceptions (Table 1).

4 Results

4.1 The powerful influence of social norms of the “typical student teacher”

In this research, it seemed that during the participants’ TE studies, the critical teacher perception was confronted with the traditional one, which was apparently maintained through the master narrative among the “typical student teachers.” Based on our findings, we suggest that the social norms of typical student teachers have the most power and influence on student teachers’ perceptions of the ideal teacher.

Our findings suggest that teacherhood is principally framed by sociocultural norms and ideals, which may be reproduced among student teachers and guide their construction of professional thinking even more strongly than the explicit goals of TE. The implicit norms and informal power relations within the student teacher community seemed to influence the transformation of perceptions and the construction of professional agency. The master narrative in the student teachers’ accounts reflected their orientation to and interest in those aspects of TE that corresponded to their internalized preconceptions of teaching as a practical job, emphasizing the implementation and reproduction of practices. The theme that seemed highly powerful in affecting the student teachers’ perceptions comprised the social norms of the typical student teacher. These norms seemed to go beyond time and context since the student teachers referred to the “typical” expected characteristics or normative behaviors of future teachers, manifested already when they were pupils in school. Being active, well-behaved pupils, earning high grades, complying with the school norms, and following the teachers’ instructions were perceived as characterizing future teachers’ own school paths.

I was always one of the front-row girls… Quite good and talented, I did not have to work too hard, but I still did because I wanted to get the highest grades. But I also got along with my classmates; I am social, too, and it has been a significant part of school life to have friends. Maybe I’m also kind of a leader type in a group, so I guided the back-row boys also to work, told them what to do, and so on. But I think I was that kind of pupil that teachers appreciated because I was curious and interested but in a good, moderate way, not like jumping on the walls for excitement. Maybe I was even a little too good, like, so we are the ones who are going to be teachers; have all teachers been like this? (L04).

I think I have always been a kind of basic good pupil, probably the kind of typical future class teacher (K11).

In TE, the social norms of the typical student teachers seemed apparent to the students. They described strong cohesion with their peers and feelings of “everyone being the same.” The typical characteristics and expected behaviors of the normative student teachers were talkativeness, being extroverts and social, and conscientious in their TE studies by aiming to accomplish what they believed was expected of them, striving to receive good grades, and qualifying as teachers. The social norms of the typical student teachers also included a kind of activeness, but it seemed that it meant participating eagerly in the tasks suggested by the teacher educators because the students seemed to allege that teacher educators had the authority to which they wanted to conform. Furthermore, normative activeness seemed oriented toward the tasks that involved social interaction and playful activities that could be put into practice with pupils.

These social norms of typical student teachers seemed to have a powerful influence on student teachers’ being and learning in TE. Conforming to the norms seemed to guarantee belonging to the peer group, having friends, and enjoying their time in TE.

I belong to those who have power [in the learning group]. Because when I have an opinion, I say it out loud, and I have noticed that others listen to me. I can be myself in the group—maybe it’s because most of the students here are like the same. So, you do not feel any different from them (L04).

[The most important thing in TE] is my peer group. We are so close that we are almost like a little family. Also, I have a feeling that everyone here is the same. Well, not everyone, but there are so many congenial people here; it is funny. It has been funny to notice how similarly we think about things (K08).

It was especially significant from the TE perspective that the norms of typical student teachers seemed to reinforce sustaining the traditional teacher perception. This was because the norms implicitly included orienting to and engaging in those areas of TE that were concordant with the students’ traditional preconceptions of the teaching profession. For example, typical student teachers were considered active in participating in the “practical” activities, such as teaching practice or subject studies, that were deemed as a teacher’s “real work.” On the contrary, lectures and what was perceived as more theoretical studies (e.g., the basic studies on education) were disliked. Therefore, to conform to the norm, students needed to engage in the practical activities and avoid theoretical studies.

4.2 Relationships with teacher educators as powerful influence

In the counter-narrative of transforming, which indicated student teachers’ perceptions evolving from the traditional preconceptions to a teacher perception that was represented in contemporary TE, the most powerful influence seemed to come from their relationships with the teacher educators. Within this narrative, the students expressed their wish to learn new perspectives, engage in reflection, and transform their conceptions of teaching. They also described their admiration for their teacher educators, which, on one hand, might have enhanced their willingness to learn; on the other hand, it might have prevented them from critically reflecting on the cultural and institutional stories of contemporary TE.

I really respect [teacher educators], and yeah, you could say that I kind of admire them. The way they lead the group is something I would like to do as well as a teacher. So, I kind of see them as models for myself. And I have not really seen anything from them yet that I would criticize, so it’s also kind of scary because then I could be misled. Maybe I eagerly accept everything they say because I kind of admire them (N06).

[The teacher educators] are important to me. If they were someone else, I do not know if I would be this excited because they show their own motivation, and I feel that I have never had these good teachers before (N01).

TE and the discourses produced and maintained there are also bound to a specific time and culture, thus influencing the student teachers’ socialization in the profession, either explicitly or implicitly (see Sitomaniemi-San, 2015; Lanas, 2017). Through critical reflection, student teachers can become aware of the channels of socialization in the teaching profession and experience more agency in relation to their profession and in defining their own sense of teacherhood (see Mezirow, 1995; Taylor, 2003; Leijen et al., 2020).

Within the counter-narrative of transformation, it seemed that some of the social norms of the typical student teachers were applicable since student teachers described similar traits of being “good pupils” in their own school years, which seemed to have led them to TE. They expressed their feelings of belonging to their peer group and the kind of “sameness,” as described in the master narrative. However, some accounts indicated that within this narrative, student teachers did not necessarily seek to have close friends from their peer group but regarded them as mere colleagues in TE studies. Thus, it seemed that despite experiencing social cohesion in their peer group, they were not as dependent on their peers as within the master narrative.

To me, peers represent, like the learning group. Like I do not want to have a best friend from them; I already have best friends in life… I want to see them as a group, and I can easily ask them about TE stuff. But I do not share more personal things with them, and I do not feel the need to (N06).

Therefore, in this narrative, their relationships with teacher educators seemed to hold the most power in influencing students’ perceptions. Nevertheless, student teachers seemed to experience enough identification with their peer group’s social norms that they felt they belonged in the group.

4.3 Sociocultural environment of the peer group in TE: contradictions and contesting the social norms

The social norms for typical student teachers became even more evident since few student teachers described going against the norm. The counter-narrative of questioning illuminated a critical teacher perception, emphasizing engagement in questions such as a teacher’s agency in alleviating social injustices (see also Hilferty, 2008; Lanas and Kiilakoski, 2013; Pantić, 2015; Quinn and Carl, 2015; Matikainen et al., 2018; Magill, 2021). This kind of orientation to teacherhood can be perceived as suggesting the transformative agency that is expected from future teachers. However, this counter-narrative had minimal appearance, and it was constructed in relation to the master narrative and the traditional teacher perception through questioning and criticism.

Resisting the master narrative of a typical student teacher appeared to span across different contexts and times since this counter-narrative included descriptions of resisting or questioning school norms in one’s own school years as a pupil or acting against the normative, expected behavior described in the master narrative.

R08: [I was] kind of a wild child, energetic and lively, did a lot of mean things, and like [adults saying], ‘Is that kid ever going to become anything sensible’ (…), not like a very ‘good pupil’? (R08).

I have always criticized teachers a lot. Both in the classroom and discussion in general. In my family, we have always talked a lot; we have been encouraged to tell our opinions. And in high school, I did that a lot; I feel that teachers do not look back and think of me with joy because I think I was always like, ‘Why cannot we do this like this?’ or ‘Why do not pupils ever get to [write on] the board? Why do only teachers do?’ (K10).

Within this counter-narrative, there also appeared contesting and acting against the typical student teacher norms. Student teachers described feeling somehow different from their peers or noticing underlying contradictions.

I have wondered, is it just that there happens to be people in my group who have all been really good in school and have always worked hard in school?… I have wondered, is everybody here like that, that they stress a lot about school? Because I want to think like, you cannot always do everything the way the teachers say; you should also think for yourself, so you do not do something that is useless… You need to question sometimes what the teachers say (K10).

I have experienced my peer group as kind of contradictory. There are some cliques in the group, a few of them, which create even more boundaries there. Kind of like an invisible boundary. And nobody says anything about it out loud, but many probably notice it (R08).

The counter-narrative of a critical teacher was based on a desire to understand the theoretical foundations of teaching, which were fundamentally different from the traditional emphasis on practice and content knowledge. Engagement in TE occurred through theoretical and critical examinations of educational issues. Issues such as ethics and values in education, the well-being of children and families, and social inequalities were identified as significant in TE. At the same time, the interest in these issues seemed to create boundaries between these student teachers and the typical ones.

I feel that I am not on the same page with my peers. Perhaps I am too critical a thinker, questioning things and reality. Little girls who have grown up in a bubble do not necessarily understand the things that I think are important in education. These include issues like inequalities in school and segregation of social realities. Personally, I think it’s absolutely essential that the teacher should remove or reduce those in education (R08).

As we had a glimpse of this particular student teacher’s further study path through the additional data collection, it is significant to note that in the description from the fifth year of studies, the narrative of questioning and critical teacher perception seemed to have led to an experience of being a “non-teacher” at the end of the studies.

I do not know if I’m non-teacher-like if I’m not that interested in teaching math or pushing facts to children. I do not know if I’m in the right field. I do not know if I should have become a sociologist or a social service worker. Maybe I’m non-teacher-like. Maybe I want to lift up people who are in unequal positions too much and probably save the whole society from ethical injustice. I guess I should concentrate more on just teaching… (R08).

This can be a concern for TE if the experience of being a “non-teacher” causes people to leave the profession (see also Lanas, 2017). Diverse pupils with various needs require different teachers, and critical and transformative teacher agents are needed to meet societal and educational challenges, such as the needs of increasingly multilingual and culturally and socially resilient schools (see Pantić, 2015; Husu and Toom, 2016; Matikainen et al., 2018; Magill, 2021; Juvonen and Toom, 2023). Diversity would thus be desirable in the future from the perspective of the renewal of the teaching profession.

5 Discussion

In this study, we have aimed to describe the socially and culturally constructed and shared ways of understanding teaching and its nature as reflected in TE students’ speech. We have done this through teacher students’ accounts of constructing teacherhood. Hence, even though we have not aimed to describe individual students, it cannot be avoided completely when illustrating the varying construction of teacherhood. Neither has it been our intention to generalize about the changes that TE does or does not bring to students’ perceptions of teaching. We also recognize that other communities of practice and influential agents which are beyond our study focus (e.g., family, media, religion, political stance) are contributing to the teacher students’ perceptions of teachers’ work. However, in our research, we have been able to identify some of the ways in which students discuss and identify TE culture, the potential for change, and the challenges they face.

Based on our study, we suggest that to understand how the perceptions of the ideal teacher are formed and how TE could better influence the transformation of these perceptions, we must consider the unofficial power relations among student teachers. These power relations seem to originate prevalently from the hegemonic discourse on the typical student teacher, which contains and might renew traditional perceptions of teaching and teachers as authorities and experts who transmit subject content knowledge and skills to pupils. This discourse seems to be renewed among and between student teachers and have more impact on students’ perceptions than the official aims of TE. Thus, in our study, the unspoken sociocultural power relations come to light in different ways, not only in the peer relations among student teachers, but also in their conceptions of teacher educators.

As mentioned above, the 2020s teachers are expected to become “change agents” who can critically reflect on and evaluate what types of changes are necessary in education and schools and also implement the required changes. Thus, TE is called for to support student teachers in developing critical reflective views about teaching and learning. This study’s results suggest that it is important to support collaborative examination of and critical reflection on teacher perceptions in TE to enable future primary teachers to construct professional transformative and critical thinking. However, the research data in this study was collected in 2014 and 2017, and more current data are needed to examine how recent trends in Finnish education system and regarding teachers’ role and expertise are reflected in today’s student teachers’ views. Nevertheless, the need for teachers’ critically reflective societal orientation can be recognized already in the early 2000’s educational administrative documentations (e.g., National Board of Education, 2004, 2014; Husu and Toom, 2016).

The master narrative of our analysis appeared to propose social and cultural norms attached to being a typical future teacher. This may restrict student teachers’ possible identities and professional agency construction to the targeted modern teacher figure. Furthermore, the traditional views of teachers as experts transferring content knowledge through practical work can be perceived as somewhat contradictory to the goals set for Finnish TE, for example, by the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture (2016).

Based on our study, we also make suggestions on how future teachers’ perceptions about the ideal teacher could be better influenced in TE. Culturally and historically shaped conceptions of the teaching profession recur powerfully in the sociocultural environment where student teachers live. For this reason, TE must emphasize the problematization of traditional conceptions of the teaching profession, strongly and unanimously promote the somewhat incongruous (with respect to the traditional visions) conceptions about the modern teacher, and pay attention to the dismantling of student teachers’ biases and preconceptions. We suggest that unraveling the unofficial power relations in the sociocultural context of TE and focusing on supporting every student teacher’s agency and critical reflection will make it possible to transform the perceptions about the ideal teacher In this regard, to promote critical thinking and democracy education and challenge the TE culture in Finland, certain different experiments have been conducted in TE in recent years,1,2 but in the big picture, these aspirations still play a minor role. There are also plenty of theoretical models to support this work (see Kincheloe, 2012; Brookfield, 2017; Korthagen, 2017; Dugas, 2021).

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

AF: Writing – original draft. MJ: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^For example, Critical Model of Integrative Teacher Education (CITE; see Nikkola et al., 2013) is one of the most long-term development projects implemented to break the traditional TE formula. This program aims to reach thinking beyond the traditional understanding of learning and teaching based on core subject certainty. The program is built on the idea that it is more important to understand the complexities of learning than to control them by didactic means.

2. ^The DERBY study group (see Hiljanen et al., 2021) is built on the idea that teacher training plays a major role in how schools and teachers (and society as a whole) should prepare for the social and cultural challenges of today’s world, such as climate change, extremism, and populism, as well as their causes.

References

Aarnos, E., and Meriläinen, M. (2007). Paikoillanne, valmiit, nyt! Opettajankoulutuksen haasteet tänään: valtakunnallinen opettajankoulutuksen konferenssi Kokkolassa 2006. Kokkola: Kokkolan yliopistokeskus Chydenius.

Alsup, J. (2006). Teacher identity discourses: Negotiating personal and professional spaces. Mahwah, N. J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Androusou, A., and Tsafos, V. (2018). Aspects of the professional identity of preschool teachers in Greece: investigating the role of teacher education and professional experience. Teach. Dev. 22, 554–570. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2018.1438309

Bamberg, M. (2004). “Considering counter-narratives” in Considering counter-narratives. Narrating, resisting, making sense. eds. M. Bamberg and A. Andrews (Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins Publishing Company), 351–371.

Bernelius, V., and Huilla, H. (2021). Koulutuksellinen tasa-arvo, alueellinen ja sosiaalinen eriytyminen ja myönteisen erityiskohtelun mahdollisuudet. VALTIONEUVOSTON JULKAISUJA, Nro 2021:7, Valtioneuvosto. Available at: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-383-761-4

Bernelius, V., and Kosunen, S. (2023). ““Three bedrooms and a nice school”—residential choices, school choices and vicious circles of segregation in the education landscape of Finnish cities” in Finland’s famous education system: Unvarnished insights into Finnish schooling. eds. M. Thrupp, P. Seppänen, J. Kauko, and S. Kosunen (Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore), 175–191.

Biesta, G. J., and Burbules, N. C. (2003). Pragmatism and educational research. Jyväskylä: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Blömeke, S., Gustafsson, J.-E., and Shavelson, R. (2015). Beyond dichotomies. Competence viewed as continuum. Z. Psychol. 223, 3–13. doi: 10.1027/2151-2604/a000194

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Britzman, D. P. (2003). Practice makes practice: A critical study of learning to teach. Revised Edn. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Clandinin, D., and Husu, J. (2017). “Mapping an international handbook of research in and for teacher education” in The sage handbook of research on teacher education. eds. D. Clandinin and J. Husu (London: SAGE Publications Ltd), 1–22.

Dugas, D. (2021). The identity triangle: Toward a unified framework for teacher identity. Teach. Dev. 25, 243–262. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2021.1874500

Education Statistics Finland (VAKAVA). (2022). Applicants in VAKAVA entrance examination in education 2015–2022. Available at: https://www.helsinki.fi/fi/verkostot/kasvatusalan-valintayhteistyoverkosto/hakeminen/tilastot (Accessed May 10, 2023).

Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture. (2016). Opettajankoulutuksen kehittämisohjelma. Hallituksen kärkihanke. Available at: https://okm.fi/documents/1410845/4583171/Opettajankoulutuksen+kehitt%c3%a4misohjelma+(13.10.2016) (Accessed November 12, 2022).

Finnish Education Evaluation Centre. (2018). “Maailman parhaiksi opettajiksi: Vuosina 2016–2018 toimineen Opettajankoulutusfoorumin arviointia”. Julkaisut 27, Kansallinen koulutuksen arviointikeskus.

Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture. (2023). Sivistyskatsaus kuvaa Suomen koulutus- ja kulttuurisektorin kehitystä viime vuosikymmenien ajalta nykypäivään. Available at: https://okm.fi/-/sivistyskatsaus-kuvaa-suomen-koulutus-ja-kulttuurisektorin-kehitysta-viime-vuosikymmenien-ajalta-nykypaivaan (Accessed March 24, 2023).

Fornaciari, A. (2020). Luokanopettajan yhteiskuntasuuntautuneisuus ja sen kriittinen potentiaali. University of Jyväskylä Dissertations.

Fornaciari, A., and Männistö, P. (2017). Yhteiskuntasuhde osana luokanopettajan ammattia – Traditionaalista vai orgaanista toimijuutta? Kasvatus 48, 353–368.

Fornaciari, A., and Rautiainen, M. (2020). Finnish teachers as civic educators – from vision to action. Citizensh Teach Learn 15, 187–201. doi: 10.1386/ctl_00028_1

Fornaciari, A., Rautiainen, M., Hiljanen, M., and Tallavaara, R. (2023). Implementing education for democracy in Finnish teacher education. Schools 20, 164–186. doi: 10.1086/724403

Furlong, C. (2013). The teacher I wish to be: exploring the influence of life histories on student teacher idealised identities. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 36, 68–83. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2012.678486

Heikkilä, M., Iiskala, T., Mikkilä-Erdmann, M., and Warinowski, A. (2022). Exploring the relational nature of teachers’ agency negotiation through master- and counter-narratives. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 43, 397–414. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2022.2038541

Heikonen, L., Toom, A., Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., and Soini, T. (2017). Student-teachers’ strategies in classroom interaction in the context of the teaching practicum. J. Educ. Teach. 43, 534–549. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2017.1355080

Helakorpi, J., Holm, G., and Liu, X. (2023). “Education of pupils with migrant backgrounds: a systemic failure in the Finnish system?” in Finland’s famous education system: Unvarnished insights into Finnish schooling. eds. M. Thrupp, P. Seppänen, J. Kauko, and S. Kosunen (Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore), 319–333.

Hilferty, F. (2008). Theorising teacher professionalism as an enacted discourse of power. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 29, 161–173. doi: 10.1080/01425690701837521

Hiljanen, M., Tallavaara, R., and Rautiainen, M., and Männistö, P. (2021). Demokratiakasvatuksen tiellä? Toimintatutkimus luokanopettajaopiskelijoiden kasvusta demokratiakasvattajiksi. Kasvatus ja aika 15, 350–368. doi: 10.33350/ka.111332

Hökkä, P. (2012). Teacher educators amid conflicting demands: Tensions between individual and organizational development. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä. Academic dissertation.

Husu, J., and Toom, A. (2010). “Opettaminen neuvotteluna – oppiminen osallisuutena: opettajuus demokraattisena professiona” in Akateeminen luokanopettajakoulutus: 30 vuotta teoriaa, käytäntöä ja maistereita. Kasvatusalan tutkimuksia. eds. A. Kallioniemi, A. Toom, M. Ubani, and H. Linnansaari (Finnish Educational Reseach Association: Helsinki), 133–147.

Husu, J., and Toom, A. (2016). Opettajat ja opettajankoulutus – suuntia tulevaan. Selvitys ajankohtaisesta opettaja opettajankoulutustutkimuksesta opettajankoulutuksen kehittämisohjelman laatimisen tueksi. Helsinki: Ministry of Education and Culture publications, 33.

Hyvärinen, M. (2020). “Toward a theory of counter-narratives: narrative contestation, cultural canonicity, and tellability” in The Routledge handbook of counter-narratives. eds. K. Lueg and M. W. Lundholt (Milton Park, UK: Taylor and Francis), 17–29.

Juutilainen, M., Fornaciari, A., Mäensivu, M., and Metsäpelto, R.-L. (in peer review). Opettajankoulutuksen transformatiivinen potentiaali luokanopettajaopiskelijoiden opettajuuskäsitysten muutoksessa.

Juutilainen, M., Metsäpelto, R.-L., Mäensivu, M., and Poikkeus, A.-M. (2023). “Beginning student teachers’ agency in teacher identity negotiations” in Teacher development

Juvonen, S., and Toom, A. (2023). “Teachers’ expectations and expectations of teachers: understanding teachers’ societal role” in Finland’s famous education system: Unvarnished insights into Finnish schooling. eds. M. Thrupp, P. Seppänen, J. Kauko, and S. Kosunen (Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore), 121–135.

Kallas, K., Nikkola, T., and Räihä, P. (2013). “Elämismaailma opettajankoulutuksen lähtökohtana” in Toinen tapa käydä koulua. Kokemuksen, kielen ja tiedon suhde oppimisessa. eds. T. Nikkola, M. Rautiainen, and P. Räihä (Tampere: Vastapaino), 19–58.

Kincheloe, J. L. (2012). Critical pedagogy in the twenty-first century: Evolution for survival. Counterpoints 422, 147–183.

Kinos, J., Saari, A., and Lindén, J. and Värri, V.-M. (2015). Onko kasvatustiede aidosti opettajaksi opiskelevien pääaine? Kasvatus 46, 176–182.

Knowles, J. G. (2003). “Models for understanding pre-service and beginning teachers’ biographies: illustrations from case studies” in Studying teachers’ lives. ed. I. F. Goodson (London: Routledge), 99–152.

Korthagen, F. (2017). Inconvenient truths about teacher learning: towards professional development 3.0. Teachers Teach 23, 387–405. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2016.1211523

Kostiainen, E., and Rautiainen, M. (2011) in Uusi koulu—oppiminen mediakulttuurin aikakaudella. ed. K. Pohjola (Jyväskylä: Jyväskylän yliopisto), 159–171.

Kuusisto, E., and Rissanen, I. (2023). Kohti päämäärätietoista yhteiskunnallista opettajuutta? Opettajaopiskelijoiden tulevalle työlleen asettamat päämäärät. Kasvatus 54, 385–398.

Lanas, M. (2017). Giving up the lottery ticket: Finnish beginning teacher turnover as a question of discursive boundaries. Teach. Teach. Educ. 68, 68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.08.011

Lanas, M., and Hautala, M. (2015). Kyseenalaistavat sopeutujat – Mikropoliittisen lukutaidon opettaminen opettajankoulutuksessa. Kasvatus 46, 48–59.

Lanas, M., and Kelchtermans, G. (2015). “This has more to do with who I am than with my skills”–student teacher subjectification in Finnish teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 47, 22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2014.12.002

Lanas, M., and Kiilakoski, T. (2013). Growing pains: teacher becoming a transformative agent. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 21, 343–360. doi: 10.1080/14681366.2012.759134

Lehtonen, J. (2023). “Rainbow paradise? Sexualities and gender diversity in Finnish schools” in Finland’s famous education system: Unvarnished insights into Finnish schooling. eds. M. Thrupp, P. Seppänen, J. Kauko, and S. Kosunen (Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore), 273–288.

Leijen, Ä., Pedaste, M., and Lepp, L. (2020). Teacher agency following the ecological model: how it is achieved and how it could be strengthened by different types of reflection. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 68, 295–310. doi: 10.1080/00071005.2019.1672855

Lindén, J. (2010). Kutsumuksesta palkkatyöhön? Perusasteen opettajan työn muuttunut luonne ja logiikka. University of Tampere, Department of Education. Academic dissertation.

Lueg, K., Bager, A. S., and Lundholt, M. W. (2020). “Introduction. What counter-narratives are: dimensions and levels of a theory of middle range” in The Routledge handbook of counter-narratives. eds. K. Lueg and M. W. Lundholt (Milton Park, UK: Taylor and Francis), 1–14.

Luukkainen, O. (2004). Opettajuus – Ajassa elämistä vai suunnan näyttämistä? Tampere: Tampereen yliopistopaino.

Magill, K. R. (2021). Identity, consciousness, and agency: critically reflexive social studies praxis and the social relations of teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 104:382. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103382

Mankki, V., and Räihä, P. (2019). Valintakriteerien ydin ja opettajankouluttajien väliset erot luokanopettajakoulutuksen opiskelijavalinnassa. Ammattikasvatuksen aikakauskirja 21, 47–63.

Männistö, P., Fornaciari, A., and Rautiainen, M. (2023). Doctoral-level teacher educators in Finland. Beiträge zur Lehrerinnen-und Lehrerbildung 41, 92–103. doi: 10.36950/bzl.41.1.2023.10057

Matikainen, M., Männistö, P., and Fornaciari, A. (2018). Fostering transformational teacher agency in Finnish teacher education. Int J Soc Pedag 7:4. doi: 10.14324/111.444.ijsp.2018.v7.1.004

Metsäpelto, R.-L., Heikkilä, M., Hangelin, S., Mikkilä-Erdmann, M., Poikkeus, A.-M., and Warinowski, A. (2022). Osaamistavoitteet luokanopettajakoulutuksen opetussuunnitelmissa: Näkökulmana Moniulotteinen opettajan osaamisen prosessimalli. Kasvatus 52, 164–179. doi: 10.33348/kvt.111437

Mezirow, J. (1995). “Uudistava oppiminen” in Kriittinen reflektio aikuiskoulutuksessa. ed. L. Lehto (Helsinki: Helsingin yliopiston Lahden tutkimus- ja koulutuskeskus)

Mykrä, N. (2023). “Ecological sustainability and steering of Finnish comprehensive schools” in Finland’s famous education system: Unvarnished insights into Finnish schooling. eds. M. Thrupp, P. Seppänen, J. Kauko, and S. Kosunen (Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore), 87–104.

National Board of Education. (2004). National Core Curriculum for basic education. Finnish National Board of education. Available at: https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/perusopetuksen-opetussuunnitelman-perusteet_2004.pdf (Accessed September 14, 2023).

National Board of Education. (2014). National Core Curriculum for basic education. Finnish National Board of education. Available at: https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/perusopetuksen_opetussuunnitelman_perusteet_2014.pdf (Accessed September 14, 2023).

Niemi, H., Erma, T., Lipponen, L., Pietilä, M., Rintala, R., Ruokamo, H., et al. (2018). Maailman parhaiksi opettajiksi: Vuosina 2016–2018 toimineen Opettajankoulutusfoorumin arviointi. Available at: https://karvi.fi/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/KARVI_2718.pdf (Accessed September 14, 2023).

Nikkola, T., Rautiainen, M., and Räihä, P. (2013). Toinen tapa käydä koulua. Kokemuksen, kielen ja tiedon suhde oppimisessa. Tampere: Vastapaino.

Nikkola, T., and Harni, E. (2015). “Vaihtoehtoinen tapa järjestää koulutusta ja koulutuksellinen hallinta” in Kontrollikoulu: näkökulmia koulutukselliseen hallintaan ja toisin oppimiseen. ed. E. Harni (Kampus Kustannus: Jyväskylä), 208–226.

Pantić, N. (2015). A model for study of teacher agency for social justice. Teachers Teach 21, 759–778. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2015.1044332

Pantić, N., and Wubbels, T. (2010). Teacher competencies as a basis for teacher education–views of Serbian teachers and teacher educators. Teach. Teach. Educ. 26, 694–703. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.10.005

Quinn, R., and Carl, N. M. (2015). Teacher activist organizations and the development of professional agency. Teachers Teach 21, 745–758. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2015.1044331

Räihä, P. (2006). “Rakenteisiin kätketyt asenteet opettajankoulutuksen tradition ja opiskelijavalintojen ylläpitäjänä” in Aktiiviseksi kansalaiseksi: Kansalaisvaikuttamisen haaste. ed. S. Suutarinen (PS-kustannus), 205–235.

Räihä, P. (2010). Koskaan et muuttua saa! Luokanopettajakoulutuksen opiskelijavalintojen. Uudistamisen vaikeudesta. Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 1559. Academic dissertation.

Raiker, A., and Rautiainen, M. (2019). “Education for democracy in England and Finland: insights for consideration beyond the two nations,” in Teacher education and the development of democratic citizenship in Europe. eds. A. Raiker, M. Rautiainen, and B. Saqipi (Routledge), 1–16.

Räsänen, K., Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., Soini, T., and Väisänen, P. (2020). Why leave the teaching profession? A longitudinal approach to the prevalence and persistence of teacher turnover intentions. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 23, 837–859. doi: 10.1007/s11218-020-09567-x

Rautiainen, M., Vanhanen-Nuutinen, L., and Virta, A. (2014). Demokratia ja ihmisoikeudet: Tavoitteet ja sisällöt opettajankoulutuksessa.

Säntti, J. (2010). “Muuttuuko opettaja -ja mihin suuntaan” in Akateeminen luokanopettajakoulutus: 30 vuotta teoriaa, käytäntöä ja maistereita. eds. A. Kallioniemi, A. Toom, M. Ubani, and H. Linnansaari (Helsinki: Finnish Educational Reseach Association), 181.

Simola, H. (2015). Koulutusihmeen paradoksit: Esseitä suomalaisesta koulutuspolitiikasta. Tampere: Vastapaino.

Simola, H., Kauko, J., Varjo, J., Kalalahti, M., and Sahlström, F. (2017). Dynamics in basic education politics—understanding and explaining the Finnish case. London: Routledge.

Sitomaniemi-San, J. (2015). Fabricating the teacher as researcher: A genealogy of academic teacher education in Finland. University of Oulu. Tampere: Juvenes Print.

Souto, A.-M. (2020). Väistelevää ohjausta—opinto-ohjauksen yksin jättävät käytänteet maahanmuuttotaustaisten nuorten parissa. Kasvatus 51, 317–329.

Syrjäläinen, E., Eronen, A., and Värri, V. M. (2006a). “Opettajaksi opiskelevien kertomaa: Opettajaksi opiskelevien yhteiskunnallinen asennoituminen ja käsityksiä omista vaikuttamismahdollisuuksistaan yliopistossa” in Kansalaisvaikuttaminen haasteena opettajankoulutukselle -tutkimuksen loppuraportti (Helsinki: Historiallis-yhteiskuntatiedollisen kasvatuksen tutkimus- ja kehittämiskeskus)

Syrjäläinen, E., Värri, V.-M., Piattoeva, N., and Eronen, A. (2006b). “Se on sellaista kasvattavaa, yleissivistävää toimintaa – Opettajaksi opiskelevien käsityksiä kansalaisvaikuttamisen merkityksestä” in Kansalaisvaikuttamisen edistäminen koulussa. Historiallis-yhteiskuntatiedollisen kasvatuksen tutkimus- ja kehittämiskeskuksen tutkimuksia. eds. J. Rantala and J. Salminen, vol. 5, 39–66.

Taylor, E. W. (2003). Attending graduate school in adult education and the impact on teaching beliefs: a longitudinal study. J. Transform. Educ. 1, 349–366. doi: 10.1177/1541344603257239

Toom, A., and Husu, J. (2016). “Finnish teachers as “makers of the many”. Balancing between broad pedagogical freedom and responsibility” in Miracle of education, 2. eds. H. Niemi, A. Toom, and A. Kallioniemi. revised ed (Rotterdam: Sense), 41–55.

Toom, A., Kynäslahti, H., Krokfors, L., Jyrhämä, R., Byman, R., Stenberg, K., et al. (2010). Experiences of a research-based approach to teacher education: suggestions for future policies. Eur. J. Educ. 45, 331–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3435.2010.01432.x

Uitto, M., Kaunisto, S.-L., Syrjälä, L., and Estola, E. (2015). Silenced truths: relational and emotional dimensions of a beginning teacher's identity as part of the micropolitical context of school. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 59, 162–176.

University of Jyväskylä Teacher education Curriculum. (2020). Primary teacher education curriculum 2020–2023. Available at: https://www.jyu.fi/edupsy/fi/laitokset/okl/opiskelu/luokanopettajakoulutus/opetussuunnitelmat-ja-opetusohjalmat (Accessed November 17, 2022).

Vähäsantanen, K. (2013). Vocational teachers’ professional agency in the stream of change. Jyväskylä Studies in Education, Psychology and Social Research 460. Academic dissertation.

Värri, V.-M. (2007). Miksi opettajankoulutuksesta täytyisi kehittyä kriittisen kasvatusajattelun areena? Teoksessa E. Aarnos & M. Meriläinen In: 2007 Paikoillanne valmiit, NYT! Opettajan koulutuksen haasteet TÄNÄÄN. Valtakunnallinen opettajankoulutuksen konferenssi Kokkolassa 2006, 22–43.

Vuorikoski, M., and Räisänen, M. (2010). Opettajan identiteetti ja identiteettipolitiikat hallintakulttuurien murroksissa. Kasvatus & Aika 4, 63–81.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2023). Finnish girls’ mental health deteriorated during COVID-19 pandemic, new data show. Available at: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/09-03-2023-finnish-girls--mental-health-deteriorated-during-covid-19-pandemic--new-data-show (Accessed March 25, 2023).

Keywords: teacher education, Finnish school, teacher student interaction, power relations, teacher competence

Citation: Fornaciari A and Juutilainen M (2023) Who has the power to define the ideal teacher? Insights into the social structure of Finnish teacher education. Front. Educ. 8:1297055. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1297055

Edited by:

Niina Meriläinen, Tampere University, FinlandReviewed by:

Lina Kaminskienė, Vytautas Magnus University, LithuaniaKristiina Skinnari, University of Jyväskylä, Finland

Copyright © 2023 Fornaciari and Juutilainen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Aleksi Fornaciari, YWxla3NpLmZvcm5hY2lhcmlAanl1LmZp

Aleksi Fornaciari

Aleksi Fornaciari Maaret Juutilainen

Maaret Juutilainen