94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 08 January 2024

Sec. Special Educational Needs

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1277218

Introduction: Compared to other countries, Sweden did not introduce sudden lockdowns and school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, the country chose a less restrictive approach to managing the pandemic, such as staying at home with any symptoms of cold or COVID-19, washing hands, and maintaining social distancing. Preschools and compulsory schools remained open. In this context, limited evidence exists about how Swedish families of students with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) experienced collaboration with school professionals to support their children during the COVID-19, and how the pandemic affected parents’ perceptions of quality of their family life. The present study investigated parental perceptions of satisfaction with family-school collaboration and with family quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: Twenty-six parents of students with SEND who attended general lower secondary schools (grades 7-9) completed a survey using three measures: the demographic questionnaire, the Beach Center Family Quality of Life scale (FQOL), and the Family-School Collaboration scale – the adapted version of the original Beach Center Family-Professional Partnership Scale. Descriptive statistics, Pearson correlations were used to analyse data.

Results: Parents felt less satisfied with family-school collaboration related to child-oriented aspects; they were least satisfied with their emotional well-being aspect of family quality of life. Strong, significant and positive associations were found between family-school collaboration and disability-related support aspect of FQOL.

Discussion: The findings point to the importance of family-school partnerships in promoting students’ positive school achievements, and in enhancing FQOL. The findings have practical implications for professional development of pre- and in-service teachers within the existing curricula of teacher preparation programs. Implications for further research are discussed given the study’s small sample size and challenges in recruitment of participants.

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic made many countries worldwide adopt various mitigation strategies such as lockdowns, school closures, and social distancing, which led to rapid changes in modes of teaching and learning forcing schools to move quickly to distance education and homeschooling (Page et al., 2021). These measures have unprecedentedly affected lives and well-being of children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) and their families due to disruption of educational support, individualized behavioral interventions, childcare support, or other services and programs (Ziauddeen et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2021). Research has shown that due to the pandemic, parents of children with SEND experienced tremendous challenges trying to balance the demands of meeting educational and socioemotional needs of their children and other family responsibilities, which resulted in increased parenting stress, depression, anxiety and unsatisfactory family quality of life (Asbury et al., 2021; Couper-Kenney and Riddell, 2021; Chen et al., 2022; Sideropoulos et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2023).

There is limited evidence about how families of students with SEND in Sweden perceived their children’s schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic. We could identify only two studies that investigated families’ perspectives of their children’s education during the initial phase of the pandemic. Thorell et al. (2022) quantitively examined experiences of homeschooling among parents to children (aged 5–19 years) with neurodevelopmental and/or mental health conditions in seven European countries, including Sweden. The majority of the Swedish parents (including parents to children aged 13–16 years) reported that provision of special educational support by schools during homeschooling was insufficient. Fridell et al. (2022) qualitatively explored the lived experiences of parents of children with autism and found that during homeschooling, putting extra efforts to deal with new routines and added pedagogical responsibilities were stressful for parents and affected them negatively. Although informative, these studies do not provide detailed information about parents’ perceptions of family quality of life (FQOL) and patterns of collaboration between parents and teachers during this critical period of children’s education. The present study contributes to the literature and reports findings on perceptions of parents to students with SEND attending general lower secondary schools on family-school collaboration and satisfaction with different aspects of FQOL during the COVID-19 pandemic in Sweden.

Family-school collaboration in general and special education has been defined as an agreement between family members and school professionals “to build on each other’s expertise and resources, as appropriate, for the purpose of making and implementing decisions that will directly benefit students and indirectly benefit other family members and professionals” (Turnbull et al., 2015, p. 161; Francis et al., 2022). A characteristic feature of effective family-school collaboration is two-way communication (Francis et al., 2022) that contributes to student academic achievements and inclusive school culture (Haines et al., 2015), helps decrease teacher stress and burnout (Haines et al., 2022), and enhances FQOL in families of children with SEND (Hsiao et al., 2017). For example, research conducted before the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic showed that parents’ satisfaction with special educational support services provided to their preschool- and school-aged children as well as high quality partnerships between parents and professionals had a positive impact on FQOL (Summers et al., 2007; Kyzar et al., 2016; Hsiao et al., 2017; Balcells-Balcells et al., 2019). However, we could locate only two studies that specifically explored relationships between family-school partnership and FQOL domains and subdomains using the Beach Center Family-Professional Partnership Scale (Summers et al., 2005a,b) and the Beach Center FQOL Scale (Hoffman et al., 2006). In their study with parents of children with autism, Eskow et al. (2018) found that parent satisfaction with child-focused partnerships was related to increased FQOL, while satisfaction with family-focused partnership was not. Kyzar et al. (2020) applied the re-examined versions of the original Family-Professional Partnership and FQOL scales with families of children with deaf-blindness and found that parents’ higher satisfaction with two partnership subdomains – connection- focused and capacity-focused – was associated with higher parent satisfaction with family interaction/parenting well-being aspects of FQOL.

In disability and special education research, the multidimensional concept of FQOL is based on recognition that disability affects the whole family system and that a child with special needs or a disability is best supported in the family context by service providers who work collaboratively with families to address the child’s needs (Summers et al., 2005a,b). FQOL extends the concept of quality of life (QoL) (Zuna et al., 2009) – a multifaceted social construct that is centered on self-determination, community participation, and well-being of an individual with a disability (Schalock et al., 2008; Samuel et al., 2012), and focuses on the individual’s physical, psychological, emotional, and social functioning (Ali et al., 2021). Thus, the concept of FQOL represents a shift from supporting and addressing needs of the individual with disability to improve his or her quality of life conditions to a more holistic view of support provision, targeting the entire family to improve the quality of various aspects of family life (Summers et al., 2005a,b; Samuel et al., 2012).

Studies that investigated an impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on FQOL among parents of children with SEND documented deteriorated emotional well-being and dissatisfaction with provision of disability-related support to their children (Chan and Fung, 2022; Romaniuk et al., 2022). On the other hand, Bolbocean et al. (2022) found no statistically significant differences in FQOL in families of children with autism and intellectual disability between the time periods before and during the first year of the pandemic, indicating family resilience due to other factors, such as positive parent–child relationships. Research on FQOL during the COVID-19 from perspective of parents of children with SEND is currently lacking in Sweden.

Compared to other countries, Sweden did not introduce sudden lockdowns; instead, the Swedish government chose a less restrictive approach to managing the pandemic based on the recommendations of the Public Health Agency of Sweden (PHA), such as staying at home if one had symptoms of an infection, washing hands, and maintaining social distancing. Also, Sweden was one of the few countries that during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic implemented a partial school closure when upper secondary schools were closed but preschools and compulsory schools (primary, middle, and lower secondary levels) remained opened (National Agency for Education, 2021a; National Agency for Education, 2021b). During the second wave of the pandemic, with the continuing spread of the COVID-19 nationally and high infection rates reaching peaks in December 2020 and January–February 2021 (Public Health Agency of Sweden, 2021), the lower secondary schools around Sweden started providing remote/distant education entirely or partially with the reliance on digital technology while the students with SEND were asked to come to schools for face-to-face, in-classroom education (National Agency for Education, 2021a). However, the majority of the schools reported provision of remote/distant education for only 2 weeks at the beginning of the spring term that started in January 2021 (National Agency for Education, 2021a). By the end of April 2021, the number of municipalities providing remote/distant education at lower secondary schools fully or partially decreased to one-third (National Agency for Education, 2021b). Yet, both the students and the school staff were to follow the PHA’s recommendations to stay at home with any slightest symptom of cold or COVID-19 infection.

In this context, there is a need to understand to what extent the general lower secondary schools could meet the needs of students who required educational accommodations and special educational support. The Swedish Education Act (2010: 800) ensures provision of support to all learners in general compulsory schools in form of (a) additional instructional or environmental accommodations provided by general teachers (e.g., substituting written assignments with oral presentations, giving students more time to complete assignments, arranging a special workplace in the classroom), and (b) special support as documented in the students’ individual educational plans (IEP) and provided by general and special teachers either individually, in small groups, or remotely. Furthermore, both general and special education policies emphasize home-school collaboration as one of the important aspects in supporting children’s learning [Education Act (2010: 800)]. Internationally, family-school collaboration has been listed as one of the key principles of successful inclusive practices in schools (Booth and Ainscow, 2016; Haines et al., 2017; Bradford et al., 2023). Nevertheless, available evidence suggests that during the pandemic, many students with SEND attending general lower secondary schools (grades 7–9) did not receive special educational support largely due to the absence of special teachers who were on sick leave (Swedish Schools Inspectorate, 2020; Public Health Agency of Sweden, 2021). This is despite the fact that 6.8% of all students enrolled in grades 7–9 during the academic year 2021–2022 (n = 361,952) had IEPs (National Agency for Education, 2022a,b) and, therefore, were entitled to receiving special educational support. Of them, the highest number of students with IEPs (n = 10,700; 8.9%) attended grade 9 (National Agency for Education, 2022a,b). Moreover, as Fridell et al. (2022) described, parents of these children in Sweden reported challenges in communication with school staff which became one of the stress factors affecting parents’ wellbeing.

To our knowledge, no studies to date have investigated parents’ perceptions of FQOL and patterns of collaboration and partnership between parents and teachers during the pandemic in Sweden using valid and reliable measures. Understanding parents’ views could help school professionals and policy makers increase awareness about these families’ life situation during that unprecedented time, and therefore, facilitate the design and use of individualized and responsive support practices provided to children with SEND and their families based on strong parent-professional partnerships during post-pandemic times or if similar crisis should occur in the future.

The present study aimed to investigate perceptions of parents to students with SEND attending general lower secondary schools on family-school collaboration and satisfaction with different aspects of FQOL during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The study addressed the following research questions:

To what extent were parents of children with SEND satisfied with family-school collaboration during the COVID-19 pandemic?

What were parents’ perceptions of their satisfaction with different aspects of family quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Were there relationships between parents’ perceptions of family-school collaboration and FQOL?

The conceptual framework of the study was the family-centered approach to provision of special educational services to children with SEND defined as practices that are respectful to families, individualized, and responsive, information sharing and family choice, parent-professional collaboration, and provision of support to produce optimal child and family outcomes (Dunst, 2002). In this approach, family empowerment is a central construct. The study also draws on seven principles of positive family-school collaboration described by Blue-Banning et al. (2004), and conceptualized by Turnbull et al. (2015) as trusting family-professional partnership: (1) communication (professionals being open, honest, tactful, listening without judgment, communicating frequently and avoiding jargon, providing information); (2) respect (treating families with dignity, valuing the child and the child’s and family’s strengths); (3) equality (feeling equally powerful in educational decision making for the child and family); (4) professional competence (having high expectations for the child’s progress; meeting the child’s individual needs, willingness to learn); (5) advocacy (advocating for the child or family with other professionals); (6) commitment (sharing a sense of assurance about devotion and loyalty to the child and family, and a belief in the importance of the goals being pursued on behalf of the child and family), and (7) trust (being reliable, discreet). To our knowledge, the present study is the first in Sweden that applied the conceptual framework of trusting family-professional partnership to investigate the parents’ perceptions of family-school collaboration and relationships with perception of FQOL during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This study is part of the larger research project that aims to investigate an impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on well-being of families of students with SEND in general lower secondary schools. The study used a cross-sectional, survey-based research design. Ethical approval was obtained from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr 2021–06167-01).

The parents were asked to participate in the study if their children (1) were enrolled in grades 8 and 9 during the academic years 2021–2022 (data collection began during the spring term 2021 and finished in December 2022); (2) received additional educational accommodations and/or special educational support due to difficulties in achieving academic goals in school subjects, and had an IEP; (3) had a disability or a chronic medical condition and received additional educational accommodations and/or special educational support. Parents were not included in the study if their children started attending grade 7 at lower secondary schools during the autumn term 2021 as these children attended middle secondary schools (grade 6) during the spring term 2021.

As Sweden does not ask schools to register students’ disabilities, recruitment could only be made using a general outreach to a wide range of gatekeepers. Parents were recruited using purposive sampling strategies by contacting school professionals responsible for provision of special educational support services (principals, deputy principals, special educators/special teachers) of both public and independent schools located in all 290 municipalities in Sweden. An additional strategy of recruiting parents was via social media platform (Facebook groups), created by interest organizations where parents were members. Besides, the researchers’ asked parents about participation in the study through their personal social network. At the beginning of the recruitment process, the first author contacted school professionals and chair persons of national and local interest organizations by email. The email message contained information about the study’s aims, procedure, and a request for assistance to identify parents according to the eligibility criteria. The message enclosed a copy of an information letter to parents with the link to a web-based self-administrated surveys. The information letter described the study’s aims, the procedure for data collection and analyses; it informed about parents’ right to withdraw at any time without explanation, and about confidentiality and protection of obtained data. Totally, 1,360 schools were contacted by email between February and September in 2022; among them 1,076 were municipal schools and 284 were independent schools. A reminder was sent to all schools in October 2022. Of all contacted schools, the school principals of 560 (41%) schools replied; of those who replied 181 (32.2%) sent an auto-message informing about their unavailability (e.g., being on a sick leave, on vacation, a conference), 110 (19.6%) replied that they either retired, stopped working as school principals, or changed their position in the municipality (e.g., started working as school principals at elementary schools); in other instances, deputy school principals answered that they would forward information about the study further to those colleagues who were responsible for provision of special support at their schools. Further, 191 (34.1%) schools did not agree to send information letters to parents, while 78 (13.9%) agreed to help to contact the parents. However, of those who agreed to assist with the study, only a handful of schools (n = 16) reported the exact number of parents (n = 70) they directly contacted and sent the information letters with the link to the online survey. Other schools did not want to inform the research team about the number of eligible parents and agreed to distribute the information letter to parents of all students via their password protected school platforms where all parents had access to. For this reason, it is not possible to report the precise number of eligible parents who were informed about the study and its aims via schools. Similarly, it is not possible to report the exact number of parents who received information about the study via interest organizations’ social media platforms. The reasons for declining participation in disseminating information about the study can be manifold, we turn to this more in the discussion.

The study’s web-based surveys were provided in Swedish and were accessible between 18 February and 24 December 2022. The surveys were designed and data was collected using Survey&Report, version 4.3. Participants read the information letter and completed an online informed consent before accessing the anonymous survey. Thirty-seven parents accessed the survey, of them 25 completed and submitted their responses. One parent who consented to participation requested a paper-based version of the survey; the survey was posted to the parent who filled in and returned it to the researchers by post. Overall, 26 parents (n = 26) were recruited to the study. Of them, 21 parents were recruited via schools, 2 – via interest organizations, and 3 – via the researchers’ social network.

Participants were 26 parents to children attending general lower secondary schools (grades 7–9) identified as having SEND, and were eligible for obtaining educational support at schools in form of additional accommodations and/or special support. Of the 26 parents (age range 34–58 years, M = 45.96, SD = 6.14), 23 (88.5%) were mothers and 3 (11.5%) were fathers. The majority of parents were Swedish-speaking (n = 21, 84%) and had a university degree (n = 17, 65.4%). All parents reported living without extended family members (e.g., grandparents) in the same household during the pandemic; of them 80.8% reported they owned their residence (houses or apartments) and had a middle or high income. Parents and their children represented various geographical areas in Sweden (see also Table 1 for additional socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants).

Of the 26 students with SEND (age range 14–16 years, M = 15.16, SD = 0.62), 8 (30.8%) were girls and 18 (69.2%) were boys. Seventeen parents (65.4%) reported that their child had at least one diagnosed disability or a chronic medical condition, while nine parents (34.6%) reported no disability or chronic medical condition for their children. According to the parents, children who had a disability or a chronic medical condition had also two or more co-occurring conditions (Table 2).

A Demographic Survey was developed specifically for the purposes of this study; the survey collected information on parents’ socio-demographic characteristics, such as age, gender, educational background, employment, first language and country of origin as proxies for ethnicity, monthly income after taxes deducted, housing, and number of family members living together, and which municipality child’s school was located. The survey also collected information on child’s characteristics, such as age, grade; whether child had disability or chronic condition. Information about type of schools (municipal or independent) and schools’ geographic location were also collected.

Family—School Collaboration Scale (FSC) – an adapted version of the Beach Center Family – Professional Partnership Scale (FPP; Summers et al., 2005a,b, 2007) – was used to investigate parents’ perceptions of family-school collaboration. The scale consists of 18 items and two subscales: Child-Focused Relationships and Family-Focused Relationships. The Child-Focused subscale contains 9 items that assess parental perceptions of the quality of the professional’s relationships with their child, and the Family-Focused subscale contains 9 items that assess parental perceptions of the quality of the professional’s relationships with the whole family. Responses are rated with each item on a five-point scale (from 1 – “very dissatisfied” to 5 – “very satisfied”). The reported internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) for the original scale is 0.93; for the Child-Focused Relationship subscale is 0.90, and for the Family-Focused Relationship subscale is 0.88. In this study, Cronbach’s α for the whole scale was 0.94; for the Child-Focused Relationship subscale α = 0.93; for the Family-Focused Relationship subscale α = 0.85, indicating very good internal consistency reliability for the scale and the subscales with our sample.

Beach Center Family Quality of Life (FQOL) Scale – 2005 version (Hoffman et al., 2006). The Beach Center FQOL Scale assesses family perceptions of satisfaction with different domains of family quality of life (Summers et al., 2005a,b). The scale contains 25 items and five subscales (domains) with very good psychometric characteristics: Family Interaction (six items, α = 0.92), Parenting (six items, α = 0.88), Emotional Well-being (four items, α = 0.80), Physical/Material Well-being (five items, α = 0.88), and Disability-related Support (four items, α = 0.92). Responses are rated from 1 – “very dissatisfied” to 5 – “very satisfied.” In the current study, Cronbach’s α for the whole scale was 0.90, and for its five subscales Cronbach’s α was 0.73, 0.69, 0.81, 0.76, and 0.65, respectively.

For the purposes of the present study, the items of the two above original scales were adapted (where appropriate) and translated from English into Swedish. The procedure for translation and adaptation was in part informed by the guidelines for cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures proposed by Guillemin et al. (1993). The first author who is proficient in Swedish and English translated the items of the original scales from English into Swedish. Modifications and adaptations were made to the items comprising the disability-related support subscale of the FQOL to fit the rules of the Swedish school system. For example, the phrase “my family member with a disability” was changed into “my family member who is in need of special support or who has a disability/a chronic medical condition.”

In the original Beach Center Parent-Professional Partnership Scale, we made the following adaptations and modifications: (1) the title of the measure was changed into “Family-School Collaboration” (Swedish translation “Familj-skolan samverkan”) (FSC), (2) the wording of item 16 was slightly changed from “Is a person you can depend on and trust” to “Have a person you can trust.” In addition, adaptations were made in the introduction and instructions to the surveys: the parents were asked to think about their perceptions of satisfaction with collaboration with school professionals and satisfaction with FQOL during the pandemic. Translations of the adapted versions were then reviewed by a parent to an adolescent with SEND who had Swedish as mother tongue. Next, back translation from Swedish into English was performed by a professional translator who did not have prior knowledge of the scales’ content. There were only a few items that had discrepancies in back-translated versions. To resolve these discrepancies, the first author consulted a senior colleague – a professor-level researcher in the field of special education who is a native English speaker and proficient in Swedish. The final Swedish translations of the scales were then used to create an online survey in the Survey&Report web application. The online survey consisted of three parts: participants’ demographics information, the FSC, and the FQOL.

The data were analyzed using SPSS (version 29). Given our sample size (n = 26), we followed the recommendations for conducting studies with small sample sizes (Lancaster et al., 2004; Hertzog, 2008; Spurlock, 2018). Thus, we did not use methods for statistical hypothesis testing; instead we focused on the description of strategies, procedures, and processes used in the study. We analyzed data using preliminary descriptive statistics; Cronbach’s alpha was used as a measure of homogeneity to examine internal consistency reliability. For further analyses, means and total scores of the FSC scale, the FQOL scale, and their subscales were calculated. To examine relationships between parents’ responses to the FSC scale and the FQOL scale, we conducted bivariate Pearson correlation analyses and its non-parametric alternative – Spearman Rank Order correlation (rho). In addition, a set of bivariate correlation analyses was performed between the FSC’s subscales and the five subscales of the FQOL scale. Furthermore, using the SPSS software, we computed 95% confidence intervals (CI) to estimate population parameter from our sample data (Cohen et al., 2013). To interpret and report the strength of the relationships between variables, we used the guidelines suggested by Cohen (1988), such as 0.10 < r < 0.30, small; 0.30 < r < 0.50, moderate; r > 0.50, large. Due to our sample size, we did not conduct regression analyses; for the same reason, we did not perform test–retest reliability and factor analyses for both scales.

Parents’ ratings of the FSC revealed an average satisfaction with the family-school collaboration (M = 3.43, SD = 0.70 for overall scale) with satisfaction ratings ranged from 2.62 to 4.23. The mean score for the child-focused relationships subscale was 3.07 (SD = 0.94) and for the family-focused relationships subscale was 3.78 (SD = 0.56). At the level of individual items, the item with the highest satisfaction score was item 12 ([School professionals] use words and expressions that you understand), followed by item 18 (Are friendly). The item with the lowest satisfaction was item 2 (Have the skills to help your child succeed). Other items that yielded lower (below the mean) satisfaction scores were item 1 (Help you gain skills or gain information to get what your child needs), item 3 (Provide support and services that meet the individual needs of your child), item 9 (Value your opinion about your child’s needs), and item 8 (Build on your child’s strengths). All these items comprise the child-focused relationships subscale (Table 3).

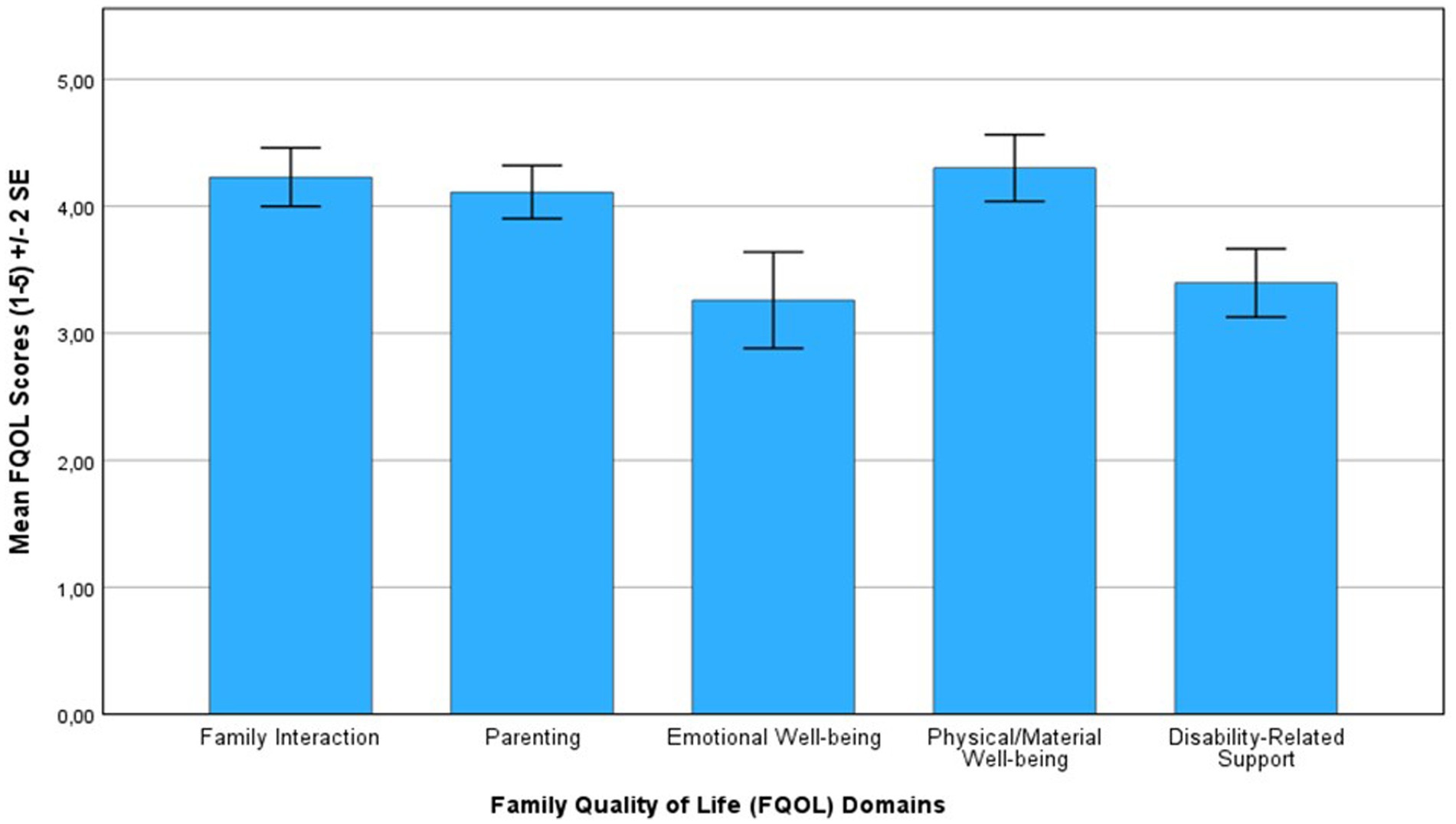

The mean scores for each item of the FQOL scale (Table 4) demonstrate that parents’ ratings ranged from 2.76 (SD = 1.09) to 4.72 (SD = 0.46) with the lowest level of parent satisfaction for item 3 (My family has the support we need to relieve stress) and the highest satisfaction for item 20 (My family gets dental care when needed). The mean score of the overall FQOL scale was 3.90 (SD = 0.50). Figure 1 shows the results of analyses for five subscales comprising the Beach Center FQOL scale. The subscale Physical/Material Well-being had the highest parent satisfaction rating (M = 4.25, SD = 0.66), followed by Family Interaction (M = 4.18, SD = 0.55), Parenting (M = 4.06, SD = 0.55), Disability-Related Support (M = 3.39, SD = 0.65). The subscale Emotional Well-being showed the lowest parent satisfaction (M = 3.27, SD = 0.90).

Figure 1. Mean FQOL subscales scores (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

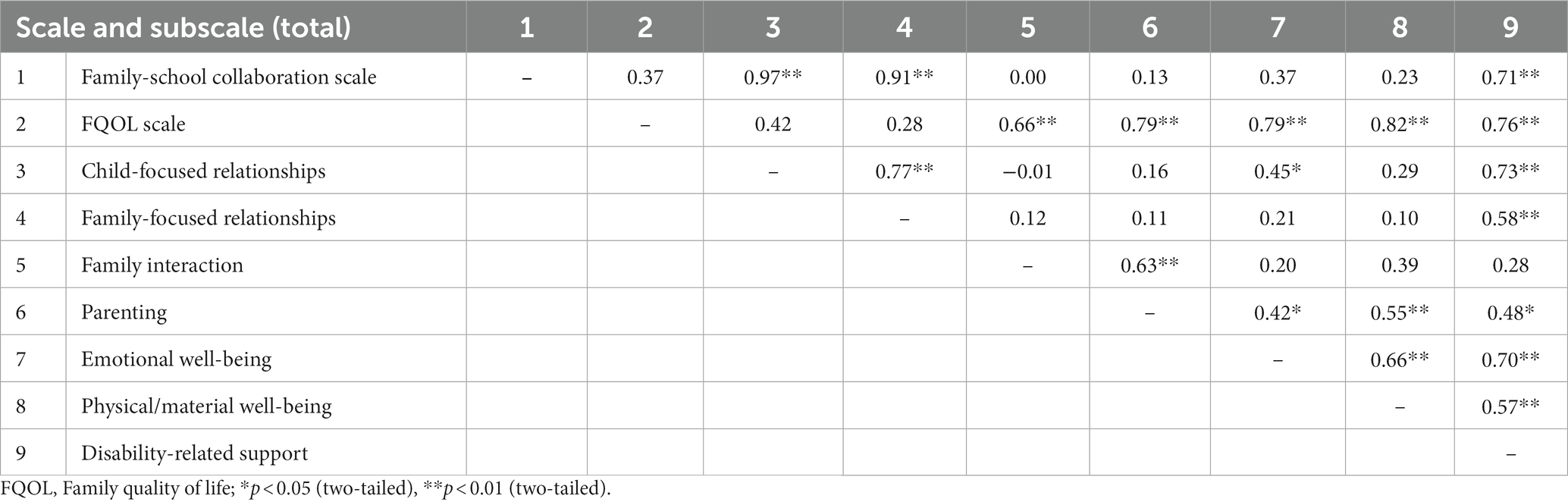

The results of bivariate correlation analyses are presented in Table 5. The correlation analyses between perceived family-school collaboration and perceived FQOL revealed no significant relationships between these variables (r = 0.37, n = 22, p = 0.90, 95% CI = [−0.06, 0.68]). However, the results showed a strong, positive correlation between the total FSC scale score and one of the domains of the FQOL scale – Disability-Related Support (r = 0.71, n = 23, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.41, 0.86]), indicating that high levels of parents’ satisfaction with family-school collaboration were associated with parental satisfaction with provision of special educational support to their children during the pandemic. The analyses between the subscales of both measures showed that there was a significant moderate, positive correlation between the Child-Focused Relationships subscale of the FSC scale and the Emotional Well-being domain of the FQOL’s scale (r = 0.45, n = 24, p = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.060, 0.72]) with high levels of parent satisfaction with child-oriented collaboration associated with higher levels of satisfaction with parents’ emotional well-being. Furthermore, there were significant strong, positive correlations between Child-Focused Relationships and Disability-Related Support (r = 0.73, n = 23, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.45, 0.87]), and between Family-Focused Relationships and Disability-Related Support (r = 0.58, n = 24, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.23, 0.79]), suggesting that high levels of parent satisfaction with child- and family-oriented collaboration were associated with higher levels of parent satisfaction with provision of support to the child during the COVID-19 pandemic. The wide confidence intervals for r obtained as a result of the correlation analyses could indicate that our study sample is not an optimal representation of the population of all Swedish parents of adolescents with SEND who attended lower secondary schools during the pandemic. This points to a need to replicate the current study with large samples in future research.

Table 5. Pearson product moment correlations between measures of perceived Family-School Collaboration and FQOL.

The present study explored perceptions of family-school collaboration and of family quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic among Swedish parents of adolescents with SEND. Before discussing the study’s findings, it is important to emphasize that these findings should be viewed as preliminary due to its small sample, and, therefore, be approached with caution.

In our study, parents’ ratings on individual items comprising the child-oriented domain of the FSC scale (research question 1) showed the lowest levels of parental satisfaction with family-school collaboration related to school professionals such as knowledge of child’s needs or skills to help the child succeed or to meet the child’s individual needs. Previous research that examined families’ collaboration and partnership with schools during the COVID-19 revealed that families whose children with disabilities received school-based services had lower satisfaction with their partnership with professionals as they did not feel that teachers met their children’s needs, effectively tracked their children’s services, or advocated for their children (Francis et al., 2021; Murphy et al., 2023).

Our results may also point to inequity in education for students with SEND during the pandemic in Sweden (Åstrand, 2020) and indicate a school-centric thinking in collaboration with families of students with SEND when the needs of teachers and schools outweighed the needs of the students and their families. As Francis et al. (2022) noted, “In school-centric models, educators are viewed as experts, and families’ views, needs, and preferences are seldom addressed or even recognized as valid” (p. 44). However, establishing and maintaining strong home-school partnerships to meet educational needs of students with SEND in general classroom settings is paramount, and has been highlighted as one of the clear lessons learned due to the COVID-19 pandemic worldwide (Bradford et al., 2023).

The study’s second research question addressed parental satisfaction with FQOL in different life domains. The results of parents’ ratings showed the lowest level of satisfaction with emotional well-being, followed by disability-related support that yielded the mean satisfaction score slightly above the average. Hoffman et al. (2006) conceptualized these two domains as resources – social support from family and friends, and support from service providers. Our findings may suggest that parents had limited resources in a form of social support provided by friends or extended family members during the pandemic. For instance, it is possible that parents in our study could not receive needed instrumental and emotional support from their elderly relatives – the children’s grandparents – who had to follow the PHA’s recommendations to keep social distancing, which may have adversely affected parents’ emotional well-being and contributed to elevated stress. A recent Swedish study by Eldén et al. (2022) provides empirical support to this explanation, showing that grandparents had to interrupt their contacts with and provide care after their grandchildren who experienced school difficulties or had chronic illnesses. Furthermore, these results also concur with previous studies of family life and accommodations of parents of children with disabilities in Sweden, which showed low satisfaction of emotional support in their lives (Wilder and Granlund, 2015).

The finding of a lower parental satisfaction with disability-related support domain could be related to the absence of qualified teachers during the pandemic. Öckert (2021) reported that in Sweden during the period of March–December 2020, absenteeism among school staff and teachers in preschools and compulsory schools increased by nearly 70 percent which was significantly higher than in 2019. This led to the additional workload for teachers of the absent colleagues and the use of substitute teachers, which presented inevitable consequences for quality of education in compulsory schools (Öckert, 2021), and thus, for provision of additional accommodations and special educational support to children with SEND as indicated in our study.

Interestingly, the correlation analyses (research question 3) revealed positive relationships between the child-focused relationships domain of the FSC scale with the FQOL’s emotional well-being domain. Furthermore, overall family-school collaboration was positively related to disability-related support, which could indicate that the more satisfied parents were with family-school collaboration around their child and family as a whole, the more satisfied they were with the quality of support provided to their children. Prior research with parents of school-aged children demonstrated that family-professional partnerships interacted with FQOL, support adequacy, and reduced stress (Burke and Hodapp, 2014; Kyzar et al., 2016; Hsiao et al., 2017). However, our findings should be approached with considerable caution as correlational statistical analyses used in the study do not allow to establish causal relationships. Future research should investigate interrelations between family-school collaboration, FQOL, parental stress, and provision of support, using other statistical methods with larger samples.

This study has several limitations. First, although the study’s participants seem to align closer with national statistics regarding cultural/ethnic background of the whole population in Sweden in 2022 that had 73.1 and 26.9% individuals with Swedish and immigrant backgrounds, respectively (Statistics Sweden, 2022), our sample, nevertheless, tends to overrepresent parents with Swedish background. Also, parents in our sample are not representative in terms of population’s socioeconomic, educational background and gender in Sweden: for example, in 2022, 41.5% women and 27% men aged 35–54 had higher educational background (Statistics Sweden, 2023), whereas the majority of the participants in our study had higher education and were predominantly women. In disability and special educational research, it is common that mothers are overrepresented (Braunstein et al., 2013) as in many cases they are primary caregivers of children with special needs or disabilities (Bourke-Taylor et al., 2010). Second limitation is the study’s small sample size, which implies that the results of statistical analyses cannot be generalized to a wider population. The study faced methodological constraints related to the recruitment of study participants both via schools and interest organizations. Nevertheless, our study could provide important information about feasibility and practicality of the chosen sampling and recruitment procedures that can be helpful for future research to address similar research questions (Hertzog, 2008). Therefore, the detailed reporting of the methodological decisions and procedures made due to the study’s small sample size can be seen as the study’s strength. Lessons to be learnt from our study design is that it is very difficult to reach parents of children with SEND through schools as gatekeepers. The reasons for declining participation in disseminating information about the study to parents can be manifold. Although considering the study’s first aim (i.e., to what extent were parents of children with SEND satisfied with family-school collaboration during the COVID-19 pandemic), one reason for principals and teachers to decline could have been that they did not want their work to be scrutinized in the difficult work time during the pandemic. In the future, established collaboration with schools and representatives of interest organizations is needed for effective recruitment of research participants for large-scale studies.

To the researchers’ knowledge, the present study was the first in Sweden that used the translated and adapted versions of the original the Beach Center FQOL and the FPP scales in the context of the Swedish educational support system, and therefore, the study can be seen as the pilot exploration of the use of these measures in general, and during the COVID-19 pandemic, in particular. These sound and well-known measures have been widely used in research within the field of special and inclusive education in several countries before and during the pandemic. The study’s preliminary analyses demonstrated good psychometric properties (Cronbach’s alpha) of the measures with our sample size (n = 26). In fact, studies that empirically examined reliability estimates of measures with small samples found that these estimates were robust in samples n ≥ 20 (e.g., Hobart et al., 2012). However, future research should investigate further reliability and validity of the translated measures with larger representative samples of parents of children with SEND in Sweden. These studies should focus further on the core aspects of parent-professional partnerships and their impact on educational outcomes for children with SEND and on parent outcomes during ordinary conditions and extraordinary circumstances similar to the COVID-19 crisis.

The study’s findings have implications for professional development. Existing curricula in pre-service and in-service teacher preparation programs should incorporate training modules focusing on the key principles of trusting family-school partnerships (Turnbull et al., 2015) aimed to facilitate development of positive and effective collaboration between parents of students with SEND and teachers to achieve optimal student and family outcomes.

The study’s findings suggest that in order to address the unique needs of students with SEND and to support families, it is vital that schools ensure that educational support is provided by qualified teachers, and that all school professionals strive to develop trustful partnerships with families by showing respect, trust, honesty, and by regularly communicating with them. This is especially important during times of crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the dataset includes a small number of participants and some collected data could potentially be identifiable. Therefore, raw, anonymized data cannot be provided upon request. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to RZ-E, cmFuby5lbmdzdHJhbmRAc3BlY3BlZC5zdS5zZQ==.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr. 2021-06167-01). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their informed consent to participate in this study.

RZ-E: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JW: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the postdoctoral fellowship awarded to RZ-E by the Department of Special Education, Stockholm University, Sweden. Open access was funded by Stockholm University.

We would like to thank all parents for their participation in the study. We also thank the school staff and the representatives of the interest organizations for their help with recruitment of participants.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ali, U., Bharuchi, V., Ali, N. G., and Jafri, S. K. (2021). Assessing the quality of life of parents of children with disabilities using WHOQoL BREF during COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Rehab. Sci 2, 1–9. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2021.708657

Asbury, K., Fox, L., Code, A., and Toseeb, U. (2021). How is COVID-19 affecting the mental health of children with special educational needs and disabilities and their families? J. Autism Dev. Disord. 51, 1772–1780. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04577-2

Åstrand, B. (2020). The Swedish school and the corona-pandemic: on school equity and segregation. In external perspektiv. Segregation och COVID-19. Delegationen mot segregation, part 6, 1–36. Available at: https://umu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1506467/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Balcells-Balcells, A., Giné, C., Guardia-Olmos, J., Summers, J. A., and Mas, J. M. (2019). Impact of supports and partnerships on family quality of life. Res. Dev. Disabil. 85, 50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2018.10.006

Blue-Banning, M., Summers, J. A., Frankland, H. C., Nelson, L. L., and Beegle, G. (2004). Dimensions of family and professional partnerships: constructive guidelines for collaboration. Except. Child. 70, 167–184. doi: 10.1177/001440290407000203

Bolbocean, C., Rhidenour, K. B., McCormack, M., Suter, B., and Holder, J. L. (2022). Resilience, and positive parenting in parents of children with syndromic autism and intellectual disability. Evidence from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on family’s quality of life and parent-child relationships. Autism Res. 15, 2381–2398. doi: 10.1002/aur.2825

Booth, T., and Ainscow, M. (2016). The index for inclusion: A guide to school development led by inclusive values. (4th ed.). Cambridge: Index for Inclusion Network.

Bourke-Taylor, H., Howie, L., and Law, M. (2010). Impact of caring for a school-aged child with a disability: understanding mothers’ perspectives. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 57, 127–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2009.00817.x

Bradford, B., Loreman, T., and Sharma, U. (2023). Principles of inclusive practice in schools: what is COVID-19 teaching us?. in International Encyclopedia of Education 4th Ed., Vol. 9. Eds. R. J. Tierney, F. Rizvi, and K. Erkican, Springer. 115–125. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-818630-5.12054-8

Braunstein, V. L., Peniston, N., Perelman, A., and Cassano, M. C. (2013). The inclusion of fathers in investigations of autistic spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 7, 858–865. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2013.03.005

Burke, M. M., and Hodapp, R. M. (2014). Relating stress of mothers of children with developmental disabilities to family-school partnerships. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 52, 13–23. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-52.1.13

Chan, R. C. H., and Fung, S. C. (2022). Elevated levels of COVID-19-related stress and mental health problems among parents of children with developmental disorders during the pandemic. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 52, 1314–1325. doi: 10.1007/s10803-021-05004-w

Chen, S., Cheng, S., Liu, S., and Li, Y. (2022). Parents’ pandemic stress, parental involvement, and family quality of life for children with autism. Front. Public Health, 10, 1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1061796

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd. New York: Academic Press.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., and Aiken, L. S. (2013). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge: Abingdon, UK

Couper-Kenney, F., and Riddell, S. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on children with additional support needs and disabilities in Scotland. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 36, 20–34. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2021.1872844

Dunst, C. J. (2002). Family-centered practices: birth through high school. J. Spec. Educ. 36, 141–149. doi: 10.1177/00224669020360030401

Education Act. (2010: 800). Available at: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/skollag-2010800_sfs-2010-800

Eldén, S., Anving, T., and Alenius Wallin, L. (2022). Intergenerational care in corona times: practices of care in Swedish families during the pandemic. J. Fam. Res. 34, 538–562. doi: 10.20377/jfr-702

Eskow, K. G., Summers, J. A., Chasson, G. S., and Mitchell, R. (2018). The association between family-teacher partnership satisfaction and outcomes of academic progress and quality of life for children with autism. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 15, 16–25. doi: 10.1111/jppi.12221

Francis, G. L., Jansen-van Vuuren, J., Gaurav, N., Aldersey, H. M., Gabison, S., and Dacison, C. M. (2021). Family-school collaboration for students with disabilities in Ontario, Canada. Network for International Policies and Cooperation in Education and Training (NORRAG), 43–51. Available at: https://resources.norrag.org/resource/659/states-of-emergency-education-in-the-time-of-covid-19

Francis, G. L., Kyzar, K., and Lavín, C. E. (2022). “Collaborate with families to support student learning and secure needed services” in High leverage practices for inclusive classrooms. eds. J. McLeskey, L. Maheady, B. Billingsley, M. T. Brownell, and T. J. Lewis, vol. 3 (New York: Routledge), 43–53.

Fridell, A., Norrman, H. N., Girke, L., and Bölte, S. (2022). Effects of the early phase of COVID-19 on the autistic community in Sweden: a qualitative multi-informant study linking to ICF. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:1268. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031268

Guillemin, F., Bombardier, C., and Beaton, D. (1993). Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 46, 1417–1432. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90142-n

Haines, S. J., Francis, G. L., Gershwin, M., Chiu, C.-Y., Burke, M. M., Kyzar, K., et al. (2017). Reconceptualizing family-professional partnership for inclusive schools: a call for action. Inc 5, 234–247. doi: 10.1352/2326-6988-5.4.234

Haines, S. J., Gross, J. M. S., Blue-Banning, M., Francis, G. L., and Turnbull, A. P. (2015). Fostering family-school partnerships in inclusive schools: using practice as a guide. Res. Pract. Persons Severe Disabl. 40, 227–239. doi: 10.1177/1540796915594141

Haines, S. J., Strolin-Goltzman, J., Ura, S. K., Conforti, A., and Manga, A. (2022). It flows both ways: relationships between families and educators during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Sci. 12:745. doi: 10.3390/educsci12110745

Hertzog, M. A. (2008). Considerations in determining sample size for pilot studies. Res. Nurs. Health 31, 180–191. doi: 10.1002/nur.20247

Hobart, J. C., Cano, S. J., Warner, T. T., and Thompson, A. J. (2012). What sample size for reliability and validity studies in neurology? J. Neurol. 259, 2681–2694. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6570-y

Hoffman, L., Marquis, J. G., Poston, D. J., Summers, J. A., and Turnbull, A. P. (2006). Assessing family outcomes: psychometric evaluation of the family quality of life scale. J. Marriage Fam. 68, 1069–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00314.x

Hsiao, Y.-J., Higgins, K., Pierce, T., Schaefer Whitby, P. J., and Tandy, R. D. (2017). Parental stress, family quality of life, and family-teacher partnerships: families of children with autism spectrum disorder. Res. Dev. Disabil. 70, 152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2017.08.013

Kyzar, K. B., Brady, S. E., Summers, J. A., Haines, S. J., and Turnbull, A. P. (2016). Services and supports, partnership, and family quality of life: focus on deaf-blindness. Except. Child. 83, 77–91. doi: 10.1177/0014402916655432

Kyzar, K. B., Brady, S., Summers, J. A., and Turnbull, A. (2020). Family quality of life and partnership for families of students with deaf-blindness. Remedial Spec. Educ. 41, 50–62. doi: 10.1177/0741932518781946

Lancaster, J. A., Dodd, S., and Williamson, P. R. (2004). Design and analyses of pilot studies: recommendations for good practice. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 10, 307–312. doi: 10.1111/j.2002.384.doc.x

Lee, V., Albaum, C., Tablon Modica, P., Ahmad, F., Willem Gorter, W., Khanlou, N., et al. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on the mental health and wellbeing of caregivers of autistic children and youth: a scoping review. Autism Res. 14, 2477–2494. doi: 10.1002/aur.2616

Murphy, A. N., Bruckner, E., Pinkerton, L. M., and Risser, H. J. (2023). Parent satisfaction with the parent-provider partnership and therapy service delivery for children with disabilities during COVID-19: associations with sociodemographic variables. Fam. Syst. Health 41, 92–100. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000720

National Agency for Education. (2021a). [Skolverket (2021a). Fjärr-och distansundervisning på högstadiet. Intervjuer med huvudmän med anledning av COVID-19-pandemin. Januari 2021]. Available at: https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.2a6bcc30176f24c38893d1/1611155811961/pdf7715.pdf

National Agency for Education. (2021b). Skolverket (2021b). Fjärr-och distansundervisning på högstadiet. Intervjuer med huvudmän med anledning av COVID-19-pandemin. April 2021. Available at: https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.645f1c0e17821f1d15c7f7/1619528410771/pdf8040.pdf

National Agency for Education. (2022a). Comments to NAE’s general recommendations on the work with extra accommodations, special support, and individual education plans. [Kommentarer till Skolverkets allmänna råd om arbete med extra anpassningar, särskilt stöd och åtgärdsprogram]. Available at: https://www.skolverket.se/publikationsserier/allmanna-rad/2022/kommentarer-till-allmanna-rad-for-arbete-med-extra-anpassningar-sarskilt-stod-och-atgardsprogram

National Agency for Education. (2022b). Special support in compulsory school. Academic year 2021/22. [Skolverket (2022). Särskilt stöd i grundskolan. Läsåret 2021/22]. Available at: https://www.skolverket.se/publikationer.

Öckert, B. (2021). “School absenteeism during the COVID-19 pandemic – how will student performance be affected?” in Swedish children and youth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Evidence from research on childhood environment, schooling, educational choice and labour market entry. ed. A. Sjögren (Ehof Grafiska AB: Uppsala), 37–81.

Page, A., Charteris, J., Anderson, J., and Boyle, C. (2021). Fostering school connectedness online for students with diverse learning needs: inclusive education in Australia during the COVID-10 pandemic. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 36, 142–156. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2021.1872842

Public Health Agency of Sweden (2020). COVID-19 in children and adolescents. A knowledge summary – Version. 2 (Folkhälsomyndigheten).

Public Health Agency of Sweden (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on daily life of schoolchildren. [Så har skolbarns vardagsliv påverkats under COVID-19-pandemin]. Available at: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/contentassets/639c11720c724721ab014feaf59fad1d/sa-har-skolbarns-vardagsliv-paverkats-covid-19-pandemin.pdf

Romaniuk, A., Ward, M., Henriksson, B., Cochrane, K., and Theule, J. (2022). Family quality of life perceived by mothers of children with ASD and ADHD. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 8, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10578-022-01422-8

Samuel, P. S., Rillota, F., and Brown, I. (2012). The development of family quality of life concepts and measures. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 56, 1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01486.x

Schalock, R. L., Bonham, G. B., and Verdugo, M. A. (2008). The conceptualization and measurement of quality of life: implications for program planning and evaluation in the field of intellectual disabilities. Eval. Program Plann. 31, 181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2008.02.001

Sideropoulos, V., Dukes, D., Hanley, M., Palikara, O., Rhodes, S., Riby, D. M., et al. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on anxiety and worries for families of individuals with special education needs and disabilities in the UK. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 52, 2656–2669. doi: 10.1007/s10803-021-05168-5

Spurlock, D. R. (2018). What’s in a name? Revisiting pilot studies in nursing education research. J. Nurs. Educ. 57, 457–459. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20180720-02

Statistics Sweden (2022). Population in Sweden by country/region of birth, citizenship and Swedish/foreign background, 31 December 2022. Available at: https://www.scb.se/en/finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/population/population-composition/population-statistics/pong/tables-and-graphs/foreign-born-citizenship-and-foreignswedish-background/population-in-sweden-by-countryregion-of-birth-citizenship-and-swedishforeign-background-31-december-2022/

Statistics Sweden (2023). Educational attainment of the population 2022. Available at: https://www.scb.se/contentassets/1b5417716c8d4b3d888d009fb3ebea6b/uf0506_2022a01_sm_a40br2309.pdf

Summers, J. A., Hoffman, L., Marquis, J., Turnbull, A., Poston, D., and Nelson, L. L. (2005a). Measuring the quality of family-professional partnerships in special education services. Except. Child. 72, 65–81. doi: 10.1177/0014402905072001

Summers, J. A., Marquis, J., Mannan, H., Turnbull, A. P., Fleming, K., Poston, D. J., et al. (2007). Relationship pf perceived adequacy of services, family-professional partnerships, and family quality of life in early childhood service programmes. Intl. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 54, 319–338. doi: 10.1080/10349120701488848

Summers, J. A., Poston, D. J., Turnbull, A. P., Marquis, J., Hoffman, L., Mannan, H., et al. (2005b). Conceptualizing and measuring family quality of life. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 49, 777–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00751.x

Swedish Schools Inspectorate (2020). Utbildning under påverkan av coronapandemin: sammanställning av centrala iakttagelser från en förenklad granskning av 225 gymnasiskolor. Available at: https://www.skolinspektionen.se/globalassets/02-beslut-rapporter-stat/granskningsrapporter/ovriga-publikationer/2020/covid-19/utbildning-under-paverkan-av-coronapandemin_gymnasieskolan-hosten-2020.pdf

Thorell, L. B., Skoglund, C., de la Peña, A. G., Baeyens, D., Fuermaier, A., Groom, M. J., et al. (2022). Parental experiences of homeschooling during the COVID-19 pandemic: differences between seven European countries and between children with and without mental health conditions. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 31, 649–661. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01706-1

Turnbull, A. P., Turnbull, H. R., Erwin, E. J., Soodak, L. C., and Shogren, K. A. (2015). Families, professionals, and exceptionality: Positive outcomes through partnerships and trust. New York. NY: Pearson.

Wilder, J., and Granlund, M. (2015). Stability and change in sustainability of daily routines and social networks in families of children with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 28, 133–144. doi: 10.1111/jar.12111

Xu, J.-Q., Poon, K., and Ho, M. S. H. (2023). Brief report: the impact of COVID-19 on parental stress and learning challenges for Chinese children with SpLD. J. Autism Dev. Disord. doi: 10.1007/s10803-023-05983-y

Ziauddeen, N., Woods-Townsend, K., Saxena, S., Gilbert, R., and Alwan, N. A. (2020). Schools and COVID-19: reopening Pandora’s box? Public Health Pract. 1, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.puhip.2020.100039

Keywords: family quality of life, family-school collaboration, parents’ perspectives, special educational needs, COVID-19, Sweden

Citation: Zakirova-Engstrand R and Wilder J (2024) Family quality of life and family-school collaboration during the COVID-19 pandemic: perceptions of Swedish parents of adolescents with special educational needs. Front. Educ. 8:1277218. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1277218

Received: 14 August 2023; Accepted: 11 December 2023;

Published: 08 January 2024.

Edited by:

Farah El Zein, Emirates College for Advanced Education, United Arab EmiratesReviewed by:

Signhild Skogdal, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, NorwayCopyright © 2024 Zakirova-Engstrand and Wilder. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rano Zakirova-Engstrand, cmFuby5lbmdzdHJhbmRAc3BlY3BlZC5zdS5zZQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.