94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 30 November 2023

Sec. Teacher Education

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1272671

This article is part of the Research TopicAdvancing Research on Teachers' Professional Vision: Implementing novel Technologies, Methods and TheoriesView all 15 articles

In classrooms, ethnic minority students are often confronted with several disadvantages – such as lower academic achievement, more negative teacher attitudes, and less teacher recognition – which are all well examined in educational research. This study sought to understand if more negative teacher attitudes and lower teacher recognition are reflected in teacher gaze. Controlling for student behavior, do teachers look more on ethnic majority than on ethnic minority students? If teachers have a visual preference for ethnic majority students in their classrooms, then we would expect that teachers show a higher number of fixations, longer duration of fixations, and shorter times to first fixation on ethnic majority compared with ethnic minority students. To test this assumption, we designed an explanatory sequential mixed-method study with a sample of 83 pre-service teachers. First, pre-service teachers were invited to watch a video of a classroom situation while their eye movements were recorded. Second, after watching the video, they were asked to take written notes on (a) how they perceived the teacher in the video attended to ethnic minority students and (b) which own experiences they can relate to situations in the video. Finally, a standardized survey measured participants’ age, gender, ethnic background, explicit attitudes toward ethnic minority students, self-efficacy for teaching ethnic minority students, and stereotypes associated with the motivation of ethnic minority students. Results indicated that, in contrast to our hypothesis, pre-service teachers had longer fixation durations on ethnic minority compared with ethnic majority students. In addition, pre-service teachers’ explicit attitudes correlated positively with number (r = 0.26, p < 0.05) and duration (r = 0.31, p < 0.05) of fixations, suggesting that pre-service teachers with more positive attitudes toward ethnic minority students also looked more and longer on ethnic minority students. Furthermore, qualitative analyses indicated that pre-service teachers associated the disadvantaged situations for ethnic minority students with teachers’ stereotypes and student language difficulties; they also referred to their own ethnic minority when reflecting on specific situations in the video. We discuss these findings considering their significance for teacher education and professional development and their implications for further research on dealing with student diversity.

Ethnic minority students tend to suffer from educational inequalities, including lower academic achievement and less teacher recognition (Gomolla, 2006; Vieluf and Sauerwein, 2018). Reasons for the emergence of these inequalities are not yet clearly understood, but there seems to be evidence suggesting that teacher attitudes and stereotypes toward ethnic minority students may play a role (Glock and Krolak-Schwerdt, 2013; Tobisch and Dresel, 2017). In education, the critical race theory has emerged as a conceptual tool to analyze ethnic minority student experiences (Ledesma and Calderón, 2015). The critical race theory began as a movement in the 1970s as a group of US lawyers and activists who wanted to combat against racism. The theory is now applied interdisciplinarily in various fields, including education, where the aim is to understand issues about day-to-day experiences at school, tests and grades, and controversies in the curriculum (Delgado and Stefancic, 2023). These issues benefit from being explored with multiple methods for a solid analysis of disadvantaged groups (Lynn and Parker, 2006). In addition to critical race theory, the intersectional theory claims that it is important to have an understanding for ethnic minority groups and their differences in social justice, inequality, and social change (Atewologun, 2018). The intersectional theory began in the late 1980s with the aim to focus on different women of different ethnicities; the term intersectional has since been used to cross gender and class with characteristics like race, ethnicity, nationality, citizenship, sexuality, and others (Zinn et al., 1986). Drawing upon critical race theory and intersectional theory, this mixed-methods study explores the gaze and visual preference of pre-service teachers associated with ethnic minority students in classrooms. We assumed that, independent of student behavior, pre-service teachers with negative attitudes and stereotypes toward ethnic minority students would look less frequently and less long at ethnic minority students and, instead, favor ethnic majority students in the classroom. To our knowledge, this study is among the first to report correlations between eye-tracking metrics and attitude measures of pre-service teachers. Findings of the study would thus add to the growing literature on student ethnicity, equity, and teacher professional vision to understand the emergence of inequalities in the classroom (Van Es et al., 2022).

Ethnicity is a complex concept, controversially discussed in the research literature. Additionally, definitions and meanings have been developed through the years. In general, ethnicity “refer[s] […] to primarily sociological or anthropological characteristics, such as customs, religious practices, and language usage of a group of people with a shared ancestry or origin in a geographical region” (Quintana, 1998, p. 28). Moreover, it describes “groups that are characterized in terms of a common nationality, culture, or language” (Betancourt and López, 1993, p. 631). In more detail, we can say that “[e]thnicity refers to a characterization of a group of people who see themselves and are seen by others as having a common ancestry, shared history, shared traditions, and shared cultural traits such as language, beliefs, values, music, dress, and food” (Cokley, 2007, p. 225). The German Statistical Federal Office (2021) defines a person as an ethnic minority person if s/he or one parent was born without German citizenship. However, this definition, excludes second generation immigrants, whose parents have German citizenship but are culturally and linguistically connected with their heritage (for a more differentiated discussion about this topic, see Will, 2019).

The Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) examined the proportion of ethnic minority students by referring to the country of birth of the students and their parents. This resulted in an unexpectedly high percentage of 22, illustrating the high proportion of ethnic minority students in Germany (Baumert and Schümer, 2001). In 2023, school authorities observed an increase of 18 percentage points of students with a foreign passport compared to the previous school year, now resulting in 39% of ethnic minority students in German classrooms (German Statistical Federal Office, 2023).

In classrooms, ethnic minority students are often confronted with a number of disadvantages, including lower academic achievement, more negative teacher attitudes, and less teacher recognition. As Gomolla, (2005, p. 46) noted, educational issues “relating to ethnic background have increased rather than diminished” (Gomolla, 2006, p. 46). The Program for International Student Assessment (Baumert et al., 2001; Hopfenbeck et al., 2017) showed that there are massive gaps in reading and mathematics competence between ethnic minority and majority students. Similarly, teacher expectations tend to be lower for ethnic minority students which also relates to ethnic minority students’ lower levels of academic self-concept, self-efficacy, self-conscience, and self-esteem (Stanat and Christensen, 2006; Chmielewski et al., 2013; McElvany et al., 2023).

One possible reason for the differences in academic achievement between ethnic minority and ethnic majority students might be attributed to the way teachers interact with and evaluate their students (Glock et al., 2013a,b). For example, Glock and Krolak-Schwerdt (2013) reported that evaluations of both in-service and pre-service teachers are biased by student ethnicity, favoring ethnic majority students. Tobisch and Dresel (2017) showed that teacher ratings of student achievement expectations and achievement aspirations were accurate for ethnic minority students but overrated and too positive for ethnic majority students. The research field on ethnic minority and majority students’ academic achievements shows an increasing awareness of the award gap between different ethnic groups. The award gap describes the difference between different ethnical groups in their educational level (Cramer, 2021). Prior research investigated causes of this award gap, “such as poverty, age, school type and learning style” (Cramer, 2021, p. 2). However, there are more causes, which are still unexplored. Sleeter (2008) documented that pre-service teacher expect less from ethnic minority compared with ethnic majority students. Ebright et al. (2021) reported that US teachers reprimand black students more likely than white students for the same misbehavior. Moreover, Weber (2003) showed that Turkish minority students experienced verbal and nonverbal discrimination from German teachers who believed Turkish minority girls were not deserving a high level of education. Such results often derive from studies conducted with ethnic majority teachers’ attitude (Kleen et al., 2019). Other studies documented that teachers’ attitudes toward ethnic minority students have been associated with teachers’ judgments and behavior (Van den Bergh et al., 2010; Kumar et al., 2015) which are primarily negative (Glock et al., 2013a,b; Glock and Karbach, 2015; Glock and Klapproth, 2017). Further evidence suggests that teachers tend to have more negative attitudes toward (Kleen and Glock, 2018) and lower recognition of Vieluf and Sauerwein (2018) ethnic minority compared with ethnic majority students. These findings document some of the disadvantages ethnic minority students tend to experience as a result of negative teacher attitudes.

On a theoretical note, attitudes are cognitive associations when evaluating objects (Fazio, 2007). Other approaches in this discourse adopt sociological perspectives, but our approach adopts a more psychological approach with a focus on teacher attitudes. The sociological perspective debates on this topic with theories such as the critical race theory and intersectional theories mentioned above (chapter 1). With a psychological approach we aim to show relations and differences in teacher attitude toward ethnic minority students. Following the attitude theory proposed by Eagly and Chaiken (2007), teacher attitudes toward ethnic minority students can be defined as psychological tendencies that are expressed by evaluating ethnic minority students with some degree of favor or disfavor. On a conceptual level, attitudes toward ethnic minority students are important components in theory models of teacher professionalism when dealing with student diversity (Baumert and Kunter, 2013 Nett et al., 2022).

A number of studies explored pre-service teachers’ attitudes toward ethnic minority students (Stephens et al., 2021). For example, Glock et al. (2019) showed that pre-service teachers had more positive attitudes toward ethnic minority students. Other aspects that are part of attitude research are self-efficacy and stereotypes (Hachfeld et al., 2012). Self-efficacy is a phenomenon that have an influence on the success of a person’s action and can change in different situations (Bandura, 2002). It describes a person’s believes in their capability to accomplish a task successfully. Thus, teachers with higher self-efficacy are more likely to be task-driven and therefore, exhibit a positive and effective behavior in the classroom (Zee and Koomen, 2016). When investigating self-efficacy in an ethnically diverse classrooms, studies tend to report differential experiences with ethnic minority and majority students (Thijs et al., 2012). Siwatu (2011), for example, reported that pre-service teachers in multicultural schools had higher self-efficacy when teaching ethnic majority students than teaching ethnic minority students. Furthermore, teachers seem to have biased expectations toward ethnic minority students (van den Bergh et al., 2010) and also perceive their relationship less positive with ethnic minority students compared with ethnic majority student (Thijs et al., 2012). In addition, teacher expectations can lead to self-fulfilling prophecies, with lower expectations being associated with lower student learning and attainment (Gentrup et al., 2020).

Moreover, stereotypes are attitudes toward a group of people with specific heterogeneity characteristics (Smith, 1998; Macrae and Bodenhausen, 2000). Thus, stereotypes influence a person’s perception and judgment unconsciously (Smith, 1998). However, categories such as ethnical heritage, gender, social heritage, or age seem to trigger stereotypes (Chang and Demyan, 2007; Tenenbaum and Ruck, 2007). In school contexts, previous research shows that due to stereotypes, teacher expectations on academic and social competence vary with regard to the ethnical heritage of the student (Parks and Kennedy, 2007; Tenenbaum and Ruck, 2007; Glock et al., 2013a,b). Teachers were less inclined to refer ethnic minority students to giftedness and talent programs compared to ethnic majority students (Elhoweris et al., 2005). Hence, ethnic minority students tend to be challenged with more difficulties in school, teacher stereotypes and, ultimately, lower future academic perspectives than ethnic majority students (Pigott and Cowen, 2000).

In addition, teacher recognition is an essential component for a fundamental student-teacher relationship (Honneth, 1995; Stojanov, 2015) on a personal and professional level with positive outcomes for students’ learning and achievements. It includes three interrelated modes: emotional support, cognitive respect, and social esteem (Honneth, 1995). Moreover, teacher recognition at school is a “method and aim of pedagogical practice” (Prengel, 2006). However, studies report that ethnic minority students experience negligence in classrooms (Prengel, 2013) which can lead to disadvantages in terms of performance evaluation and the assignment to social positions (Prengel, 2002; Fraser and Honneth, 2003; Helsper et al., 2005; Helsper, 2008). Thus, ethnic minority students are more likely to experience lower teacher recognition than ethnic majority students; as Vieluf and Sauerwein (2018, p. 3) note: “At school, learning takes place within and through intersubjective relations between students and teachers as among classmates, which are […] structured by recognition.” Yet, recognition from teachers is a central component for a positive student-teacher relationship (Prengel, 2008, 2013). Jenlink (2009) showed that there is a fine line between social esteem and the reduction of an individual’s value. Thus, according to the performance of a person, their social esteem can vary and therefore, influence their individual value. As Vieluf and Sauerwein (2018, p. 5) note, ethnic minority students “might be at greater risk of experiencing misrecognition in terms of cognitive respect and social esteem at school than their peers” (Vieluf and Sauerwein, 2018, p. 5) who are ethnic majority students. The authors documented that ethnic minority students experienced less cognitive respect from their teachers compared to ethnic majority students, concluding that ethnic minority students “were treated in an unfair or offensive way by their teachers” (Vieluf and Sauerwein, 2018, p. 17) because teachers’ expectations were lower for these group of students.

Taken together, not only attitudes, self-efficacy, and stereotypes but also teacher recognition might predict pre-service teachers’ judgment of ethnic minority students’ competencies in classroom situations. According to the two-stage model of dispositional attributions (Trope, 1986), people base their trait judgments on two processes: Identification and categorization. The identification stage builds on situational, behavioral, and identity cues (Trope, 1986 Trope, 2004). This means that prior knowledge about the person, such as group membership (Gawronski and Creighton, 2013) is necessary to identify stereotypical characteristics of this person. The salience of stereotypical trait attributes is also positively related to attitudes (Fishbein, 2008). Thus, attitudes have been shown to predict trait judgments (Olson and Fazio, 2004).

The categorization stage builds on the behavior, identity, and the situation of the person (Trope, 1986). These three types of information have different effects on trait judgment (Trope, 1986). On the one hand behavioral and identity information positively influence the strength of trait judgments and on the other hand situational information reduce strength (Trope, 1986). As mentioned in the first stage, knowledge about the person, such as group membership (Gawronski and Creighton, 2013), is necessary to identify stereotypical characteristics which can evoke attitudes toward that group of people (Gonsalkorale et al., 2010).

Overall, these findings suggest disadvantages for ethnic minority students. However, it is still unclear what these disadvantages are based on. The question arises if these disadvantages are rooted in the gaze of teachers.

Teachers’ professional vision is known as a key competence of professional teachers (Berliner, 2001; Gegenfurtner et al., 2011; Lachner et al., 2016; König et al., 2022; Anderson and Taner, 2023). It is defined as the ability of teachers to recognize and interpret relevant classroom situations (Seidel and Stürmer, 2014). Seidel and Stürmer (2014) distinguish between two dimensions: noticing and knowledge-based reasoning. Through noticing, teachers identify relevant classroom situations. With reasoning, teachers interpret the identified situation.

Studies in the field of teacher professional vision are often conducted with eye-tracking technology to precisely observe teachers’ eye movements during classroom events and to make them accessible for further analysis (Goldberg et al., 2021; Keskin et al., 2023). Previous eye-tracking research used a number of different metrics (Grub et al., 2020, in press); some important metrics for this present study include the number of fixations, the duration of fixations, and time to first fixation. Holmqvist et al. (2011) described fixations as a period in which the eye has little to no movement. In a broader sense, fixations are an indicator of which areas of the environment teachers attend to, and from which areas information is received from, or which stimuli are important. The number and duration of fixations describe the frequency and the period of time of a particular fixation on a particular area of interest. The time to first fixation describes the time until the first fixation on a particular area of interest occurs (Holmqvist et al., 2011; Grub et al., 2020). In order to determine certain gaze behavior from the eye movements, these parameters are meaningful. Previous studies showed that pre-service teachers frequently fixate on student behavior and levels of student engagement (Cortina et al., 2018; Schnitzler et al., 2020; Goldberg et al., 2021). Moreover, some studies have shown that pre-service teachers’ pay less attention to critical classroom situations than in-service teachers (van den Bogert et al., 2014; Wolff et al., 2016). In addition, pre-service teachers are less likely to observe the whole classroom and monitor more students at the same time (McIntyre et al., 2020; Kosel et al., 2021). These are findings showing that pre-service students have more difficulty getting an overview of the class.

However, the challenge to get an overview expands with ethnic minority students in the classroom because of racism and discrimination (Schedler et al., 2019). In terms of ethnic minority students, there is little research done yet with eye tracking. Comparing the eye movements of teachers on ethnic minority and majority students requires more investigation. With eye tracking we can have access into cognitive processes and explicitly show individual behavior. Therefore, some questions are arising. If it is true that pre-service teachers allocate their attentional resources to individual students and if it is also true that teacher attitudes and stereotypes can influence levels of teacher recognition dedicated toward individual students (or particular student groups, such as ethnic minority students), then it would be interesting to explore the associations between teacher attitudes and their fixations on ethnic minority students. To our knowledge, however, previous studies have not yet examined the extent to which teacher fixations differ between ethnic minority and majority students and the extent to which attitudes, self-efficacy, and stereotypes correlate with different eye tracking measures in the classroom.

This study had two aims. A first aim was to examine differences in pre-service teachers’ fixations on ethnic minority and ethnic majority students. We hypothesized that pre-service teachers would have a higher fixation number (Hypothesis 1a), longer fixation durations (Hypotheses 1b), and shorter times to first fixation (Hypotheses 1c), on ethnic majority compared with ethnic minority students. A second aim was to investigate associations of the number of fixations, duration of fixations, and time to first fixation with teacher attitudes, self-efficacy, and stereotypes. We assumed that pre-service teachers gaze on ethnic minority students would correlate positively with explicit attitudes (Hypothesis 2a) and self-efficacy (Hypothesis 2b) toward ethnic minority students and negatively with stereotypes (Hypothesis 2c). To triangulate the quantitative survey and eye-tracking data, we used qualitative analyses of pre-service teachers’ written notes to contextualize how they perceived the teacher behavior of the teacher shown in the video reconstruct their own lived experiences.

Participants were N = 83 pre-service teachers (66 women, 17 men) with a mean age of 21.4 years (SD = 2.9). Data for the study were collected during the spring term of 2022. We invited pre-service teachers from three seminars of a national teacher education program of a large university in Southern Germany to participate in the study for course credit. They were on average in their third semester (SD = 1.6). The pre-service teachers were enrolled in different programs preparing for four different school types: A total of 60.2% participants were enrolled in the primary education program (Grundschule), 18.1% participants in higher-track secondary education (Gymnasium), 12% in middle-track secondary education (Realschule), and 9.6% in lower-track secondary education (Mittelschule). School type did not significantly moderate any of the measures, so we combined participants across programs. Anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed for all participants, with written informed consent obtained prior to the study.

Pre-service teachers were invited to individual laboratory sessions to watch a 10-min-video of an authentic classroom situation on a 1,920 × 1,080 px screen while their eye movements were tracked. Before watching the video, the eye-tracking system was adjusted to the individual features of the participant based on a nine-point calibration. Participants were seated approximately 60 cm from the display. The video showed an art class in third grade. Ethnic minority and majority students sat in front of the blackboard with their back to the camera and had a discussion with an experienced female teacher about the artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser. The students were closely listening to the teacher and were not disruptive (in terms of being loud and interrupt the interactions) through the 10-min-video. In the class were 13 students with five of them being ethnic minority students. However, the pre-service teachers who participated in our study were not told who of the students came from ethnic minorities. The teacher in the video encouraged the students to create own ideas for redesigning the school building following Hundertwasser’s aesthetic and style. Figure 1 shows a screenshot of the stimulus material.

Figure 1. Visualizing of the video. We marked ethnic minority students in yellow and ethnic majority students in blue.

Participants were instructed to watch the video and focus on the behavior of the teacher while she interacted with the students. Afterwards, the pre-service teachers were asked to take written notes on two questions: “How does the teacher interact with ethnic minority students? Do you remember situations in which you made experiences with ethnic minority students in class?” Finally, participants completed a multi-item questionnaire with items on their age, gender, semester, study program, ethnic background, explicit attitudes toward ethnic minority students, self-efficacy for teaching ethnic minority students, and stereotypes associated with the motivation to learn of ethnic minority students.

Measures included eye movements, demographic information, explicit attitudes, self-efficacy, and stereotypes.

Eye movements were recorded with a Tobii Pro Spectrum screen-based eye-tracker with a temporal resolution of 1,200 Hz and analyzed with the Tobii Pro Lab 1.123 software.1 From the classroom videos, two ethnic minority students (one female, one male) were chosen because they were unambiguously identifiable as ethnic minority based on skin color and first name. These two ethnic minority students were matched with two ethnic majority students (one female, one male) who showed similar levels of hand-raising behavior, classroom talk, and sitting position. All four target students were defined as areas of interest (AOI). AOIs were created manually. Because the video was dynamic, AOIs were transient and of varying size, with an average pixel size of 88 × 146 px for the ethnic minority students and 84 × 145 px for the ethnic majority students. Data for each AOI were aggregated to determine the number of fixations, fixation duration, and time to first fixation on ethnic minority vs. majority students.

Demographic information was measured with items on pre-service teacher age (in years), gender (female, male, nonbinary), teacher education program (primary, lower-secondary, middle-secondary, higher-secondary), number of semesters, and birth place of their parents (coded as 0 = Germany, 1 = Russia, 2 = Macedonia, 3 = Poland, 4 = Romania, 5 = Thailand, 6 = Kazakhstan, 7 = Turkey, 8 = Hungary, 9 = Moldova, 10 = Slovakia, 11 = Kosovo).

Explicit attitudes toward ethnic minority students were measured with a 101-point feeling thermometer (Alwin, 2007). We adapted the instruction from Norton and Herek (2013) and asked: “Think of an imaginary thermometer with a scale from zero to 100. The warmer or more favorable you feel toward ethnic minority students, the higher the number you should give it. The colder or less favorable you feel, the lower the number. If you feel neither warm nor cold toward ethnic minority students, rate it 50.” Lower rating (minimum = 0) indicated more negative feelings and higher ratings (maximum = 100) indicated more favorable feelings.

Self-efficacy for teaching ethnic minority students was measured with four items adapted from Hachfeld et al. (2012) on a 5-point Likert scale. An example item is: “I am confident that I can adapt my teaching to the needs of ethnic minority students.” Cronbach’s alpha was α = 0.98.

Stereotypes about the school-related motivation of ethnic minority students was measured with five items adapted from Hachfeld et al. (2012) on a 5-point Likert scale. An example item was: “Ethnic minority students are less interested in school-related topics.” Cronbach’s alpha was α = 0.99.

To address Hypotheses 1a–1c, a series of Mann–Whitney U Tests were performed because the data were non-normally distributed. Thus, we used non-parametric methods to analyze differences in the number of fixations, duration of fixations, and time to first fixation on ethnic minority and ethnic majority students. Moreover, we performed a linear regression. We defined attitudes, self-efficacy, and stereotypes as independent variables and we analyzed number of fixations, duration of fixations, and time to first fixation as dependent variables. To address Hypotheses 2a–2c, one-tailed Pearson correlations using attitudes, self-efficacy, stereotypes, and all fixation measures were calculated. The written notes were analyzed qualitatively following the systematic data analysis approach. Braun and Clarke (2006) noted that a thematic analysis is helpful in analyzing qualitative data when aiming to search for patterns or themes in the data material. Therefore, two trained raters (κ = 0.85) used their guideline to conduct a thematic analysis with our qualitative data. Following an inductive approach, we identified three categories (positive, negative, and neutral) and five subcategories (motivation, stereotypes, no difference, language difficulties, and experience) that emerged from the written notes in which pre-service teachers reported positive, negative, and neutral thoughts with respect to their own lived experiences and how they perceived the teacher behavior in the video.

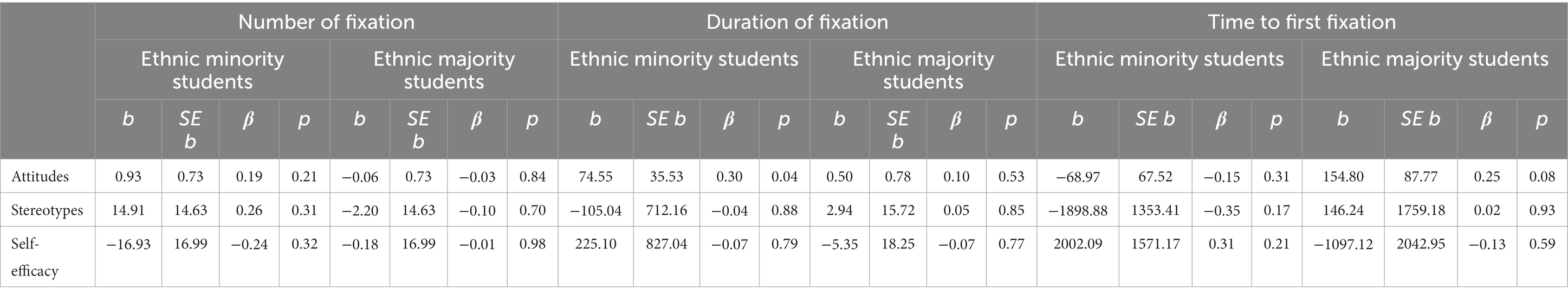

Hypothesis 1 assumed that pre-service teachers would have a higher fixation number (Hypothesis 1a), longer fixation durations (Hypotheses 1b), and shorter times to first fixation (Hypotheses 1c), on ethnic majority compared with ethnic minority students. Table 1 reports mean and standard deviation estimates for all fixations measures per student group. Mann–Whitney U Tests revealed a significant difference in fixation duration, U = 379.00, Z = −2.10, p < 0.05, with longer fixation durations on ethnic minority compared with ethnic majority students. Differences in fixation number and time to first fixation were statistically non-significant. Moreover, the regression coefficient shows that there is an influence on fixation duration. Therefore, pre-service teachers with a positive attitude toward ethnic minority students have longer fixations toward ethnic minority students. Since the value of p (<0.04) is smaller than 0.05, this relation is statistically significant. Hence, our findings show a relation between pre-service teachers’ fixation duration and ethnic minority students (see Table 2).

Table 2. Regression analysis of number of fixation, duration of fixation, and time to first fixation with attitudes, stereotypes, and self-efficacy.

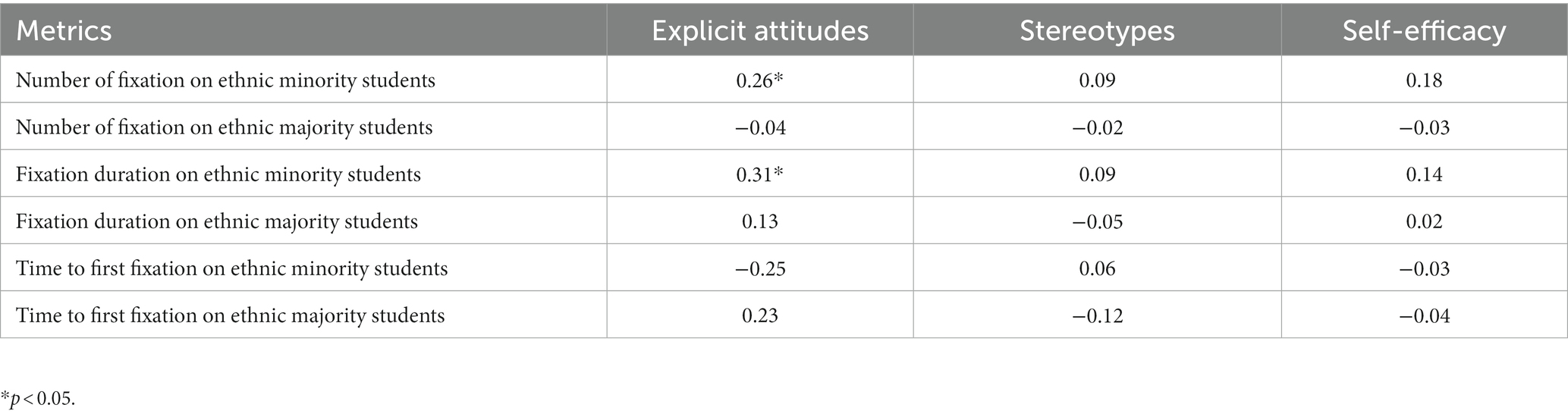

Hypothesis 2 assumed that pre-service teachers’ gaze on ethnic minority students would correlate positively with positive explicit attitudes (Hypothesis 2a) and self-efficacy (Hypothesis 2b) toward ethnic minority students and negatively with stereotypes (Hypothesis 2c). Table 3 presents Pearson correlations between these measures. Results show significantly positive correlations of explicit attitudes toward ethnic minority students with the number (r = 0.26, p < 0.05) and duration of fixations (r = 0.31, p < 0.05) on ethnic minority students. Analyzing pre-service teachers’ ethnical background in this context showed no significant correlation.

Table 3. Correlation of eye-tracking metrics with explicit attitudes, stereotypes, and self-efficacy.

To identify additional thoughts related to ethnic minority students, we asked the pre-service teachers to explain how they perceived the teacher behavior shown in the video and to reconstruct their own lived experiences (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The three main categories were positive, negative, and neutral, referring to participants’ assessment of the behavior of the teacher shown. Overall, pre-service teachers stated positive (53 units), negative (46 units), and neutral (43 units) perceptions of teacher behavior in the video and about their own lived experiences (see Table 4 for details).

In the positive category, pre-services teachers reported for example: “In addition, she is very considerate of the ethnic minority students”; “[…] and let them speak often”; “the teacher […] complimented […] the ethnic minority students.”

In the negative category, pre-service teachers reported for example: “[I]t seemed to me that the teacher paid less attention to the ethnic minority students and rarely picked them”; “I noticed that she strongly complimented ethnic majority students”; “I can imagine that she did not include ethnic minority students who have less language skills”; “[h]aving ethnic minority background myself, I could see that in the teachers’ behavior.”

In the neutral category, pre-service teachers reported for example: “I believe that the teacher did not treat the ethnic minority students any different”; “[…] the teacher makes no distinction between ethnic minority and majority students”; […] “[…] she calls each child without paying attention to their ethnic background and leaves none out.”

The written notes of the pre-service teachers showed a wide range of positive, negative, and neutral viewpoints, which might indicate no explicit racist bias or any preferences for ethnic majority or minority students. To analyze the written notes more deeply, these three categories were subsequently specified into five more detailed subcategories. The subcategories motivation, no difference, and stereotypes refer to the assessment of the pre-service teachers on the behavior of the teacher shown. The subcategory language difficulties reflect statements of students for whom German was not their first language. The subcategory experience refers to own experiences of the per-service teachers. Pre-service teachers stated most frequently motivation (54 units) and no difference (43 units), followed by stereotypes (35 units), language difficulties (8 units), and experience (4 units).

In the motivation subcategory, pre-service teachers reported for example: “She tries to bring all the ethnic minority students along by speaking very clearly and slowly, also gesticulating more to what is being said […]”; “[t]he ethnic minority students are also motivated to speak again and again”; “[…] when the ethnic minority student said something, she repeated and strongly emphasized his answer positively.”

Looking into the subcategory no difference, pre-service teachers reported for example: “If a child did not abide by the rules, she pointed this out, regardless of the ethnic minority background”; “she does not favor or disadvantage any of the ethnic minority or majority students”; “I do not remember any special or different treatment.”

Furthermore, in the stereotypes subcategory, pre-service teachers reported for example: “I feel that the teacher somewhat neglected the ethnic minority students, even though these students wanted to participate and engage in class”; “[…] it can also be seen that the teacher unconsciously makes a distinction between ethnic minority and majority student”; “The compliments could be a bit more pronounced with ethnic minority students, because I noticed that she complimented a lot of ethnic majority students and ignored the ethnic minority students. I think she was judgmental.”

In the subcategory language difficulties, pre-service teachers reported for example: “You could hear that [the ethnic minority student] had difficulties with sentence structure. The teacher could have been more responsive to him”; “[…] forgets the special support ethnic minority students need because they have not yet fully mastered the language”; “[ethnic minority students] need special language support because they do not fully master the language. She did not pay attention to that.”

Lastly, in the experience subcategory, pre-service teachers reported for example: “I have an ethnic minority background myself, I could see that in the teachers’ behavior”; I also have an ethnic minority background and therefore know that this sometimes happens”; “I can also say from my experience that this happens very often and also happened to me because I also have an ethnic minority background.”

By dividing the categories into these five subcategories, it can be seen that pre-service teachers mostly recognize teacher behavior with a positive attitude toward ethnic minority students with the explanation that the teacher is motivating the students by highlighting their behavior and inviting them to participate. Only a few pre-service teachers reconstructed their own lived experiences. This can be partly attributed to the fact that (a) only 20.8% of the participants reported of own ethnic minority background and (b) participants reported 11 different cultural heritages, hampering systematic comparisons.

The aim of this study was to explore relations of pre-service teachers’ gaze, attitudes, and student ethnicity. With respect to the first aim of this study, an analysis of pre-service teacher fixations on ethnic minority and majority students showed a significant difference in terms of fixation duration: Contrary to our hypothesis, pre-service teachers fixated longer on ethnic minority than on ethnic majority students. Reasons for this visual preference are likely independent of student behavior (Goldberg et al., 2021), hand-raising (Kosel et al., 2021), or classroom talk (Kosel et al., 2021) because we controlled for these parameters. This visual preference can neither be explained by the pixel size of the AOIs which were comparable for ethnic minority and majority students. Instead, a likely explanation for the longer fixation durations on ethnic minority students might be associated with the positive attitudes and levels of self-efficacy that pre-service teachers reported when working with ethnic minority students, which could demonstrate their positive levels of teacher recognition (Vieluf and Sauerwein, 2018).

An alternative explanation is that pre-service teachers had longer fixation durations on ethnic minority students because they required more time monitoring students who potentially needed guidance (Schnitzler et al., 2020) or were assumed to show off-task behavior (Hendrickson, 2018; Ebright et al., 2021), which would reflect their metacognitive monitoring (Gegenfurtner et al., 2020). However, it can also be interpreted as unconscious bias and deficit thinking which is itself an example of the award gap. Findings of the present study confirm previous evidence reported in Ebright et al. (2021) because pre-service teachers fixate more and longer ethnic minority students.

Such an explanation would also emerge when reflecting on the qualitative analysis of the written notes taken after watching the classroom video, in which some pre-service teachers indicated an awareness of the students’ language difficulties, which could have resulted in a higher allocation of attentional resources. Furthermore, the findings indicate that pre-service teachers’ explicit attitude correlates with their duration of fixation and number of fixations on ethnic minority students which indicates that a positive explicit attitude toward ethnic minority students was related to more and longer fixations on ethnic minority students. However, we could not find any associations with self-efficacy and stereotypes. This might be because pre-service teachers were not in the position of teaching but watching a classroom video on action, in which they might not feel the presence and affiliation and shared histories with the students (Short et al., 1976; Kreijns et al., 2004). Another possible explanation could relate to a self-serving bias: pre-service teachers were perhaps less willing to admit they had negative stereotypes on pre-service teachers’ motivation to learn—which is not specific to our study but a frequent problem in survey-based research in the social sciences more broadly.

Looking at the qualitative data, the written notes reflect a broad range of positive, negative, and neutral comments. While most of the pre-service teachers reported positive notes—suggesting that the in-service teacher in the video had a positive, motivating approach toward ethnic minority students—other pre-service teachers commented on negative aspects of the observed classroom situation (such as the management of student language difficulties) and their own lived experiences. Regarding pre-service teachers’ visual focus of attention to ethnic minority and ethnic majority students, the results showed that the pre-service teachers’ descriptions of student-teacher relationship shown in the video can be explained by the triangulation of the qualitative and quantitative data. The results may indicate that paying attention to social relations in the classroom requires teachers to have more and longer fixations on disadvantaged students. Prior studies have shown that teachers often distribute their attention unevenly among their students (Dessus et al., 2016; Haataja et al., 2019). However, these studies focused on teachers’ expertise and students’ achievements. The findings of the present study indicate that pre-service teachers’ pay attention to the social relations between the teacher and the students shown in the video and thus report more positive observations. Other negative reports in terms of stereotypes, language difficulties, and own experiences may indicate that pre-service teachers’ can detect the complexity of classroom situations and therefore, distribute their attention among ethnic minority and majority students. In terms of practical implications, these findings can inspire video-based teacher education programs to let pre-service teachers reflect on their own attitudes and stereotypes and afford pre-service teachers a safe space for reconstructing their own, perhaps disadvantaged, experiences made in their own school biographies. This could be done in such a way that pre-service teachers have the opportunity to play certain situations in classrooms through videos and explicitly have the opportunity to discuss them with fellow students or even experts. In addition, by showing them their own gaze movements after watching classroom videos, is a possibility to use the eye-tracking device as an instrument of reflection.

This study has some limitations that should be noted. First, we limited our work on using an authentic classroom video which was shown in the laboratory on a screen-based eye tracker, so we could not control classroom dynamics shown in the video (e.g., seating arrangement or situational circumstances). In addition, we also could not control factors such as bright colors in the video or restless movements of pre-service teachers’ pupils. Still, authentic classroom videos are often used studies on teacher professional vision and teacher noticing (Cortina et al., 2018; Henderson and Hayes, 2018; Grub et al., 2022; Van Es et al., 2022; Keskin et al., 2023). Future research can consider using a mobile eye tracker in real-world or virtual reality classrooms to explore teacher fixations in action. Second, our sample included only pre-service teachers which limits the generalizability of our results to the population of in-service teachers. A comparison between pre-service and in-service teachers can be addressed in future studies. Third, we observed four students who were similar in their classroom behavior and pixel size. To extend these first exploratory results presented here, future studies could consider adding a larger number of students, or even all students in class. Fourth, we used questionnaire items to assess explicit attitudes toward ethnic minority students. Future studies might want to consider using implicit association tests to minimize the effects of a self-serving bias on any of the attitude measures (Glock et al., 2013a,b; Glock and Karbach, 2015; Kleen et al., 2019 Tobisch and Dresel, 2017).

In conclusion, this study is among the first to explore the relations between attitude and fixation measures in a sample of pre-service teachers. The study is also among the first to address any differences in teacher gaze between ethnic minority and majority students. Future research is encouraged to address the nexus of teacher professional vision and teacher attitudes as an important aspect of teacher professionalism in culturally diverse classroom contexts.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

ÖK: Writing – original draft. SG: Writing – review & editing. IK: Writing – review & editing. AG: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author is grateful for financial support of the Young Researchers Travel Scholarship Program of the University of Augsburg.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Alwin, D. F. (2007). Margins of error: a study of reliability in survey measurement. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

Anderson, J., and Taner, G. (2023). Building the expert teacher prototype: A metasummary of teacher expertise studies in primary and secondary education. Educ. Res. Rev. 38:100485. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100485

Atewologun, D. (2018). Intersectionality theory and practice. D Atewologun Oxford research encyclopedia of business and management. Oxford Oxford University Press

Bandura, A. (2002). Social cognitive theory in cultural context. Appl. Psychol. 51, 269–290. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00092

Baumert, J., Klieme, E., Neubrand, M., Prenzel, M., Schiefele, U., Schneider, W., et al. (2001). “Deutsches PISA-Konsortium” in PISA 2000. Basiskkompetenzen von Schülerinnen und Schülern im internationalen Vergleich (Leske + Budrich)

Baumert, J., and Kunter, M. (2013). Stichwort: Professionelle Kompetenz von Lehrkräften. Z. Erzieh. 9, 469–520. doi: 10.1016/50187-893X(14)70553-1

Baumert, J., and Schümer, G. (2001). Familiäre Lebensverhältnisse, Bildungsbeteiligung und Kompetenzerwerb. In Deutsches PISA-Konsortium (Eds.), PISA 2000. Basiskompetenzen von Schülerinnen und Schülern im internationalen Vergleich (pp. 323–410). Opladen Leske + Budrich.

Berliner, D. C. (2001). Learning about and learning from expert teachers. Int. J. Educ. Res. 35, 463–482. doi: 10.1016/S0883-0355(02)00004-6

Betancourt, H., and López, S. R. (1993). The study of culture, ethnicity, and race in American psychology. Am. Psychol. 48, 629–637. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.48.6.629

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Chang, D. F., and Demyan, A. L. (2007). Teachers’ stereotypes of Asian, Black, and White students. Sch. Psychol. Q. 22, 91–114. doi: 10.1037/10445-3830.22.2.91

Chmielewski, A. K., Dumont, H., and Trautwein, U. (2013). Tracking effects depend on tracking type: an international comparison of students’ mathematics self-concept. Am. Educ. Res. J. 50, 925–957. doi: 10.3102/0002831213489843

Cokley, K. (2007). Critical issues in the measurement of ethnic and racial identity: A referendum on the state of the field. J. Couns. Psychol. 54, 224–234. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.224

Cortina, K. S., Müller, K., Häusler, J., Stürmer, K., Seidel, T., and Miller, K. F. (2018). Feedback mit eigenen Augen: Mobiles Eyetracking in der Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung [Feedback through one’s own eyes: mobile eye tracking in teacher education]. Beiträge zur Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung 36, 208–222. doi: 10.25656/01:17097

Cramer, L. (2021). Alternative strategies for closing the award gap between white and minority ethnic students. elife 10:e58971. doi: 10.7554/eLife.58971

Delgado, R., and Stefancic, J. (2023). Critical race theory: an introduction. New York, NY New York University Press.

Dessus, P., Cosnefroy, O., and Luengo, V. (2016). “Keep your eyes on ‘em all!’: A mobile eye-tracking analysis of teachers’ sensitivity to students” in Adaptive and adaptable learning. eds. K. Verbert, M. Sharples, and T. Klobučar (Cham: Springer), 72–86.

Eagly, A. H., and Chaiken, S. (2007). The advantages of an inclusive definition of attitude. Soc. Cogn. 25, 582–602. doi: 10.1521/soco.2007.25.5.582

Ebright, B., Cortina, K. S., and Miller, K. F. (2021). “Scrutiny and opportunity: Mobile eye tracking demonstrates differential attention paid to black students by teachers” in Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association. USA

Elhoweris, H., Mutua, K., Alsheikh, N., and Holloway, P. (2005). Effect of children’s ethnicity on teachers’ referral and recommendation decisions in gifted and talented programs. Remedial Spec. Educ. 26, 25–31. doi: 10.1177/07419325050260010401

Fazio, R. H. (2007). Attitudes as object–evaluation associations of varying strength. Soc. Cogn. 25, 603–637. doi: 10.1521/soco.2007.25.5.603

Fishbein, M. (2008). “An investigation of the relationship between the beliefs about an object and the attitude toward the object” in Attitudes: their structure, function, and consequences. eds. R. H. Fazio and R. E. Petty (New York, NY: Psychology Press), 133–136.

Fraser, N., and Honneth, A. (2003). Redistribution or recognition? A political-philosophical exchange. London: Verso.

Gawronski, B., and Creighton, L. A. (2013). “Dual process theories” in The Oxford handbook of social cognition. ed. D. E. Carlston (New York: Oxford University Press), 282–312.

Gegenfurtner, A., Lehtinen, E., and Säljö, R. (2011). Expertise differences in the comprehension of visualizations: a meta-analysis of eye-tracking research in professional domains. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 23, 523–552. doi: 10.1007/s10468-011-9174-7

Gegenfurtner, A., Lewalter, D., Lehtinen, E., Schmidt, M., and Gruber, H. (2020). Teacher expertise and professional vision: Examining knowledge-based reasoning of pre-service teachers, in-service teachers, and school principals. Front. Educ. 5:59. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00059

Gentrup, S., Lorenz, G., Kristen, C., and Kogan, I. (2020). Self-fulfilling prophecies in the classroom: Teacher expectations, teacher feedback and student achievement. Learn. Instr. 66:101296. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101296

German Statistical Federal Office (2021). Datenreport 2021. Ein Sozialbericht für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Bonn: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung

German Statistical Federal Office (2023). Datenreport 2023. Ein Sozialbericht für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. Bonn.

Glock, S., and Karbach, J. (2015). Preservice teachers’ implicit attitudes toward racial minority students: Evidence from three implicit measures. Stud. Educ. Eval. 45, 55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2015.03.006

Glock, S., and Klapproth, F. (2017). Bad boys, good girls? Implicit and explicit attitudes toward ethnic minority students among primary and secondary school teachers. Stud. Educ. Eval. 53, 77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2017.04.002

Glock, S., Kneer, J., and Kovacs, C. (2013a). Preservice teachers’ implicit attitudes towards students with and without immigration background: A pilot study. Stud. Educ. Eval. 39, 204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2013.09.003

Glock, S., Kovacs, C., and Pit-ten Cate, I. (2019). Teachers’ attitudes towards ethnic minority students: effects of schools’ cultural diversity. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 89, 616–634. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12248

Glock, S., and Krolak-Schwerdt, S. (2013). Does nationality matter? The impact of stereotypical expectations on student teachers’ judgements. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 16, 111–127. doi: 10.1007/s11218-012-9197-z

Glock, S., Krolak-Schwerdt, S., Klapproth, F., and Böhmer, M. (2013b). Beyond judgment bias: how students’ ethnicity and academic profile consistency influence teachers’ tracking judgments. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 16, 555–573. doi: 10.1007/s11218-013-9227-5

Goldberg, P., Schwerter, J., Seidel, T., Müller, K., and Stürmer, K. (2021). How does learners’ behavior attract preservice teachers’ attention during teaching? Teach. Teach. Educ. 97:103213. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2020.103213

Gomolla, M. (2005). Schulentwicklung in der Einwan‐derungsgesellschaft: Strategien gegen institutionelle Diskriminierung in England, Deutschland und in der Schweiz. Münster: Waxmann

Gomolla, M. (2006). Tackling underachievement of learners from ethnic minorities: A comparison of recent policies of school improvement in Germany, England and Switzerland. Curr. Issues Comparat. Educat. 9, 46–59.

Gonsalkorale, K., Alle, T. J., Sherman, J. W., and Klauer, K. C. (2010). Mechanisms of group membership and exemplar exposure effects on implicit attitudes. Soc. Psychol. 41, 158–168. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000023

Grub, A.-S., Biermann, A., and Brünken, R. (2020). Process-based measurement of professional vision of (prospective) teachers in the field of classroom management. A systematic review. J. Educ. Res. Online 12, 75–102. doi: 10.25656/01:21187

Grub, A.-S., Biermann, A., and Brünken, R. (in press). “Eye tracking as a process-based methodology to assess teacher professional vision” in Teacher professional vision: Theoretical and methodological advances. eds. A. Gegenfurtner and R. Stahnke (Routledge)

Grub, A.-S., Biermann, A., Lewalter, D., and Brünken, R. (2022). Professional vision and the compensatory effect of a minimal instructional intervention: a quasi-experimental eye-tracking study with novice and expert teachers. Front. Educat. 7:890690. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.890690

Haataja, E., Toivanen, M., Laine, A., and Hannula, M. S. (2019). Teacher-student eye contact during scaffolding collaborative mathematical problem-solving. Int. J. Math Sci. Technol. Educat. 7, 9–26. doi: 10.31129/LUMAT.7.2.350

Hachfeld, A., Schröder, S., Anders, Y., Hahn, A., and Kunter, M. (2012). Multikulturelle Überzeugung. Herkunft oder Überzeugung? Welche Rolle spielen der Migrationshintergrund und multikulturelle Überzeugung für das Unterrichten von Kindern mit Migrationshintergrund? Z. Entwicklungspsychol. Padagog. Psychol. 26, 101–120. doi: 10.1024/1010-0652/a000064

Helsper, W. (2008). Schulkulturen - die Schule als symbolische Sinnordnung. Z. Pädag. 53, 63–80. doi: 10.25656/01:4336

Helsper, W., Sandring, S., and Wiezorek, C. (2005). “Anerkennung in institutionalisierten, professionellen pädagogischen Beziehungen. Ein Problemaufriss” in Integrationspotenziale einer modernen Gesellschaft. eds. W. Heitmeyer and P. Imbusch (Wiesbaden, Springer VS), 179–206.

Henderson, J. M., and Hayes, T. R. (2018). Meaning guides attention in real-world scene images: evidence from eye movements and meaning maps. J. Vis. 18, 1–18. doi: 10.1167/18.6.10

Hendrickson, M. (2018). Teacher response to student misbehavior: Assessing potential biases in the classroom [bachelor thesis, University of Michigan]. DeepBlue. Available at: https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/147364/mhendr.pdf

Holmqvist, K., Nyström, M., Andersson, R., Dewhurst, R., Jarodzka, H., and Van de Weijer, J. (2011). Eye tracking: a comprehensive guide to methods and measures. Oxford Oxford University Press.

Honneth, A (1995). The struggle for recognition: the moral grammar of social conflicts. Cambridge, MA MIT Press.

Hopfenbeck, T. N., Lenkeit, J., El Masri, Y., Cantrell, K., Ryan, J., and Braid, J.-A. (2017). Lessons learned from PISA: a aystematic review of peer-reviewed articles on the programme for international student assessment. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 63, 333–353. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2016.1258726

Jenlink, P. M. (2009). “Affirming diversity, politics of recognition, and the cultural work of school” in The struggle for Identity in Today’s Schools: Cultural recognition in a time of increasing diversity. eds. P. M. Jenlink and F. H. Townes (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education), 14–29.

Keskin, Ö., Seidel, T., Stürmer, K., and Gegenfurtner, A. (2023). Eye-tracking research on teacher professional vision: a meta-analytic review. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Kleen, H., Bonefeld, M., Glock, S., and Dickhäuser, O. (2019). Implicit and explicit attitudes toward Turkish students in Germany as a function of teachers’ ethnicity. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 22, 883–899. doi: 10.1007/s11218-019-09502-9

Kleen, H., and Glock, S. (2018). The roles of teacher and student gender in german teachers’ attitudes toward ethnic minority students. Stud. Educ. Eval. 59, 102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2018.04.002

König, J., Santagata, R., Scheiner, T., Adleff, A.-K., Yang, X., and Kaiser, G. (2022). Teacher noticing: a systematic literature review of conceptualizations, research designs, and findings on learning to notice. Educ. Res. Rev. 36, 1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100453

Kosel, C., Holzberger, D., and Seidel, T. (2021). Identifying expert and novice visual scanpath patterns and their relationship to assessing learning-relevant student characteristics. Front. Educat. 5, 1–16. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.612175

Kreijns, K., Kirschner, P. A., Jochems, W., and Van Buuren, H. (2004). Determining sociability, social space, and social presence in (a)synchronous collaborative groups. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 7, 155–172. doi: 10.1089/109493104323024429

Kumar, R., Karabenick, S. A., and Burgoon, J. N. (2015). Teachers’ implicit attitudes, explicit beliefs, and the mediating role of respect and cultural responsibility on mastery and performance-focused instructional practices. J. Educ. Psychol. 107, 533–545. doi: 10.1037/a0037471

Lachner, A., Jarodzka, H., and Nückles, M. (2016). What makes an expert teacher? Investigating teachers’ professional vision and discourse abilities. Instr. Sci. 44, 197–203. doi: 10.1007/s11251-016-9376-y

Ledesma, M. C., and Calderón, D. (2015). Critical race theory in education: A review of past literature and a look to the future. Qual. Inq. 21, 206–222. doi: 10.1177/1077800414557825

Lynn, M., and Parker, L. (2006). Critical race studies in education: Examining a decade of research on US schools. Urban Rev. 38, 257–290. doi: 10.1007/s11256-006-0035-5

Macrae, C. N., and Bodenhausen, G. V. (2000). Social cognition: Thinking categorically about others. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 51, 93–120. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.93

McElvany, N., Lorenz, R., Frey, A., Goldhammer, F., Schilcher, A., and Stubbe, T. C. (2023). IGLU 2021. Lesekompetenz von Grundschulkindern im internationalen Vergleich und im Trend über 20 Jahre. Göttingen Waxmann Verlag.

McIntyre, N., Mulder, K. T., and Mainhard, M. T. (2020). Looking to relate: Teacher gaze and culture in student-rated teacher interpersonal behavior. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 23, 411–431. doi: 10.1007/s11218-019-09541-2

Nett, U. E., Dresel, M., Gegenfurtner, A., Matthes, E., Peuschel, K., and Hartinger, A. (2022). Förderung der Lehrkräfteprofessionalität im Umgang mit Heterogenität in der Schule. In A. Hartinger, M. Dresel, E. Matthes, U. E. Nett, K. Peuschel, and A. Gegenfurtner (Eds.), Lehrkräfteprofessionalität im Umgang mit Heterogenität. Theoretische Konzepte, Förderansätze, empirische Befunde (pp. 21–40). Münster: Waxmann.

Norton, A. T., and Herek, G. M. (2013). Heterosexuals’ Attitudes Toward Transgender People: Findings from a National Probability Sample of U.S. Adults. Sex Roles. 68, 738–753. doi: 10.1007/s11199-011-0110-6

Olson, M. A., and Fazio, R. H. (2004). Trait inferences as a function of automatically activated racial attitudes and motivation to control prejudiced reactions. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 26, 1–11. doi: 10.1207/s15324834basp2601_1

Parks, F. R., and Kennedy, J. H. (2007). The impact of race, physical attractiveness, and gender on education majors’ and teachers’ perceptions of student competence. J. Black Stud. 37, 936–943. doi: 10.1177/0021934705285955

Pigott, R. L., and Cowen, E. L. (2000). Teacher race, child race, racial congruence, and teacher ratings of children’s school adjustment. J. Sch. Psychol. 38, 177–196. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4405(99)00041-2

Prengel, A. (2002). “Ohne Angst verschieden sein?” – Mehrperspektivische Anerkennung von Schulleistungen in einer Pädagogik der Vielfalt” in Pädagogik der Anerkennung. Grundlagen, Konzepte, Praxisfelder. eds. N. Hafeneger, P. Henkenborg, and A. Scherr (Frankfurt: Wochenschau Verlag), 203–221.

Prengel, A. (2006). Pädagogik der Vielfalt: Verschiedenheit und Gleichberechtigung in Interkultureller, Feministischer und Integrativer Pädagogik. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Prengel, A. (2013). Pädagogische Beziehungen zwischen Anerkennung, Verletzung und Ambivalenz. Opladen: Budrich.

Quintana, S. M. (1998). Children’s development understanding of ethnicity and race. Appl. Prev. Psychol. 7, 27–45. doi: 10.1016/S0962-1849(98)80020-6

Schedler, J., Elverich, G., Achour, S., and Jordan, A. (2019). “Rechtsextremismus und Schule: Herausforderungen, Aufgaben und Perspektiven” in Rechtsextremismus in Schule, Unterricht und Lehrkräftebildung, Edition Rechtsextremismus. (pp. 1–17). eds. J. Schedler, G. Elverich, S. Achour, and A. Jordan (Wiesbaden: Springer) doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-26423-9_1

Schnitzler, K., Holzberger, D., and Seidel, T. (2020). Connecting Judgment Process and Accuracy of Student Teachers: Differences in Observation and Student Engagement Cues to Assess Student Characteristics. Front. Educat. 5, 1–28. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.602470

Seidel, T., and Stürmer, K. (2014). Modeling and measuring the structure of professional vision in preservice teachers. Am. Educ. Res. J. 51, 739–771. doi: 10.1007/s1046-020-09532-2

Short, J., Williams, E., and Christie, B. (1976). The social psychology of telecommunications. London John Wiley & Sons.

Siwatu, K. O. (2011). Preservice teachers’ sense of preparedness and self-efficacy to teach in America’s urban and suburban schools: does context matter? Teach. Teach. Educ. 27, 357–365. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.09.004

Sleeter, C. (2008). “Preparing White teachers for divers students” in Handbook of research on teacher education. eds. S. Feiman-Nemser and D. J. McIntyre (New York, NY: Routledge), 559–582.

Smith, E. R. (1998). “Mental representation and memory” in Handbook of social cognition. eds. D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, and G. Lindzey (New York: McGraw-Hill), 391–445.

Stanat, P., and Christensen, G. S. (2006). Where immigrant students succeed: A comparative review of performances and engagement in PISA 2003. Paris OECD.

Stephens, J. M., Rubi-Davies, C., and Peterson, E. R. (2021). Do preservice teacher education candidates’ implicit biases of ethnic differences and mindset toward academic ability change over time? Learn. Instr. 78:101480. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2021.101480

Stojanov, K. (2015). “Educational justice as respect egalitarianism” in Paper presented at the annual conference of the society for philosophy of education of Great Britain. Oxford

Tenenbaum, H. R., and Ruck, M. D. (2007). Are teachers' expectations different for racial minority than for European American students? A meta-analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 99, 253–273. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.253

Thijs, J. T., Westhof, S., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2012). Ethnic incongruence and the student-teacher relationship: The perspective of ethnic majority teachers. J. Sch. Psychol. 50, 257–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2011.09.004

Tobisch, A., and Dresel, M. (2017). Negatively or positively biased? Dependencies of teachers’ judgments and expectations based on students’ ethnic and social backgrounds. Soc. Psychol. Educat. 20, 731–752. doi: 10.1007/s11218-017-9392-z

Trope, Y. (1986). Identification and inferential processes in dispositional attribution. Psychol. Rev. 93, 239–257. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.93.3.239

Trope, Y. (2004). Theory in social psychology: Seeing the forest and the trees. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 8, 193–200. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0802_13

Van den Bergh, L., Denessen, E., Hornstra, L., Voeten, M., and Holland, R. W. (2010). The implicit prejudiced attitudes of teachers: Relations to teacher expectations and the ethnic achievement gap. Am. Educ. Res. J. 47, 497–527. doi: 10.3102/0002831209353594

Van den Bogert, N., Van Bruuggen, J., Ksotons, D., and Jochems, W. (2014). First steps into understanding teachers’ visual perception of classroom events. Teach. Teach. Educ. 37, 208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2013.09.001

Van Es, E. A., Hand, V., Agarwal, P., and Sandoval, C. (2022). Multidimensional noticing for equity: theorizing mathematics teachers’ systems of noticing to disrupt inequities. J. Res. Math. Educ. 53, 114–132. doi: 10.5951/jresematheduc-2019-0018

Vieluf, S., and Sauerwein, M. N. (2018). Does a lack of teachers’ recognition of students with migration background contribute to achievement gaps? Eur. Educat. Res. J., 1–12. doi: 10.1177/14749041/18810939

Weber, M. (2003). Heterogenität im Schulalltag. Konstruktionen ethnischer geschlechtlicher Unterschiede. Opladen. Leske + Budrich.

Will, A.-K. (2019). The German statistical category “migration background”: Historical roots, revisions and shortcomings. Ethnicities 19, 535–557. doi: 10.1177/1468796819833437

Wolff, C. E., Jarodzka, H., Van den Bogert, N., and Boshuizen, H. P. A. (2016). Teacher vision: Expert and novice teachers’ perception of problematic classroom management scenes. Instr. Sci. 44, 243–265. doi: 10.1007/s112251-016-9367-z

Zee, M., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2016). Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teacher well-being: a synthesis of 40 years of research. Rev. Educ. Res. 86, 1–35. doi: 10.3102/0034654315626801

Keywords: ethnic minority students, teacher professional vision, fixation, eye tracking, pre-service teacher

Citation: Keskin Ö, Gabel S, Kollar I and Gegenfurtner A (2023) Relations between pre-service teacher gaze, teacher attitude, and student ethnicity. Front. Educ. 8:1272671. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1272671

Received: 04 August 2023; Accepted: 30 October 2023;

Published: 30 November 2023.

Edited by:

Christian Kosel, Technical University of Munich, GermanyReviewed by:

Simon Munk, Technical University of Munich, GermanyCopyright © 2023 Keskin, Gabel, Kollar and Gegenfurtner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Özün Keskin, b2V6dWVuLmtlc2tpbkB1bmktYS5kZQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.