Corrigendum: Meaningful connection in virtual classrooms: graduate students' perspectives on effective instructor presence in blended courses

- 1Department of Educational Leadership, Policy, and Technology Studies, College of Education, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL, United States

- 2Department of Modern Languages and Classics, College of Arts and Sciences, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL, United States

This qualitative study explored 15 graduate students’ perspectives on effective online instructor presence. Analysis of interviews, a survey, and a focus group revealed students value early relationship-building through consistent participation, authentic personality-sharing, and learner-centered course design. Results indicate effective instructor presence fosters trust, satisfaction, engagement, and positive student mindsets while reducing stress and anxiety. Students preferred visible, accessible instructors who connect through prompt communication, constructive feedback, and active listening. Additional findings suggest leveraging synchronous interactions enhances social presence and relationship-building. However, disconnected instructor presence caused frustration and negative emotions. Overall, intentional instructor presence is critical for successful online instruction and profoundly shapes learners’ holistic experiences beyond solely academic goals. While limited to one program, these learner-centered insights provide a starting point for identifying high-impact presence-building strategies tailored to graduate contexts.

Introduction

Effective online instructor presence is increasingly vital as remote and hybrid learning expand. However, creating a meaningful instructor presence remains an evolving puzzle requiring learner-centered insights. While prior research demonstrates the benefits of instructor presence for satisfaction, engagement, and learning outcomes (Caskurlu, 2018; Law et al., 2019; McNeill et al., 2019; Um and Jang, 2021), few studies deeply explore graduate student perspectives, especially within blended environments. This qualitative study helps fill that gap by interviewing graduate learners about the specific behaviors, actions, and dispositions facilitating effective instructor presence in virtual classrooms.

Current literature conceptualizes instructor presence as the specific actions and behaviors through which an instructor projects themselves as a real person to students, as well as how the instructor is socially and pedagogically positioned within the online community (Richardson et al., 2015). Instructor presence is connected with academic performance, student engagement, a sense of community, and collaborative learning (Garrison et al., 2000, 2001; Shea et al., 2014; Wang and Liu, 2020).

The aim of the current study is to advance the understanding of effective online graduate instruction by gathering rich, qualitative insights into the specific behaviors, actions, and dispositions that facilitate instructor presence from a learner perspective.

Prior quantitative studies demonstrate the benefits of instructor presence, but few qualitatively explore student interpretations of how presence is established, especially in blended contexts. This study helps fill the gap by interviewing graduate students to unveil practical techniques for relationship-building, engagement, and interpersonal connections from their lived experiences. This exploratory approach will provide in-depth insights into the pedagogical and relational approaches students find most meaningful for presence, tailored to graduate needs in blended environments.

Literature review

Instructor presence

Establishing effective instructor presence has emerged as an important focus in online education research, yet exactly how to create meaningful presence remains an evolving area of inquiry. Going beyond the concept of teaching presence within the Community of Inquiry framework, instructor presence encapsulates the individual behaviors, actions, and dispositions of the teacher as a real person forming interpersonal connections with learners (Richardson et al., 2015). Instructor presence influences key outcomes like student performance, engagement, satisfaction, and sense of community (Arbaugh et al., 2008; Shea et al., 2014; Khalid and Quick, 2016).

Online instructor presence can determine students’ performance (Arbaugh et al., 2008; Law et al., 2019), engagement behaviors (Zhang et al., 2016; McNeill et al., 2019), and learning satisfaction (Khalid and Quick, 2016; Kyei-Blankson et al., 2016), the latter of which has been shown to influence students’ intention to continue to use online learning (Um and Jang, 2021).

Recent studies reveal complex, multifaceted aspects of effective online instructor presence. For example, Trammell and LaForge (2017) identified behaviors like using video conferencing, giving timely feedback, and sharing personal stories as key strategies for presence. Similarly, Van Wart et al. (2019) found instructors enhanced presence by leveraging announcements, audio/video, and interactive tools to create an approachable, caring persona. However, Lowenthal and Dennen (2017) note obstacles like workload and communication challenges can impede presence.

While quantitative measures provide useful data on instructor presence (Armellini and De Stefani, 2016), few studies deeply explore student perceptions and preferences through qualitative methods. A learner-centered perspective is critical for delineating the aspects of presence most influential on satisfaction, engagement, and learning. As Clark et al. (2015) argue, “a priority for future research should be exploratory studies that give voice to the lived experiences of participants” (p. 194).

As open questions remain around which specific instructor dispositions and pedagogical approaches graduate students find most meaningful when establishing presence, especially in blended and synchronous contexts (Martin and Bolliger, 2018), this study aims to address that need by qualitatively analyzing student interpretations of effective online instructor presence. Findings will provide humanizing insights to guide professional development and identify high-impact presence-building strategies tailored to graduate contexts.

Online presence

The unique features of online environments have led to the change and expansion of the instructor role. As instructors assume various roles in online instructional environments, they establish an online presence (Richardson et al., 2016). “Online presence” refers to the ways in which instructors make themselves socially and pedagogically present in the online learning environment (Garrison, 2015). This can involve having a personal page on the course website, being active in discussion forums, keeping the video camera on during live sessions, using audio feedback on assignments, responding promptly to student emails and questions, and facilitating frequent interaction with and among students (Garrison et al., 2000).

Social and facilitating roles are emphasized in online environments because of the lack of physical interaction and presence. To overcome the geographical barriers associated with learning at a distance, online instructors should actively facilitate discussion, provide timely feedback, and enable social connections with and among students (Anderson et al., 2001; Picciano, 2002). This online presence helps create a sense of community for students who may feel isolated or disconnected in online courses (Garrison and Arbaugh, 2007; Vesely et al., 2007).

Theoretical framework

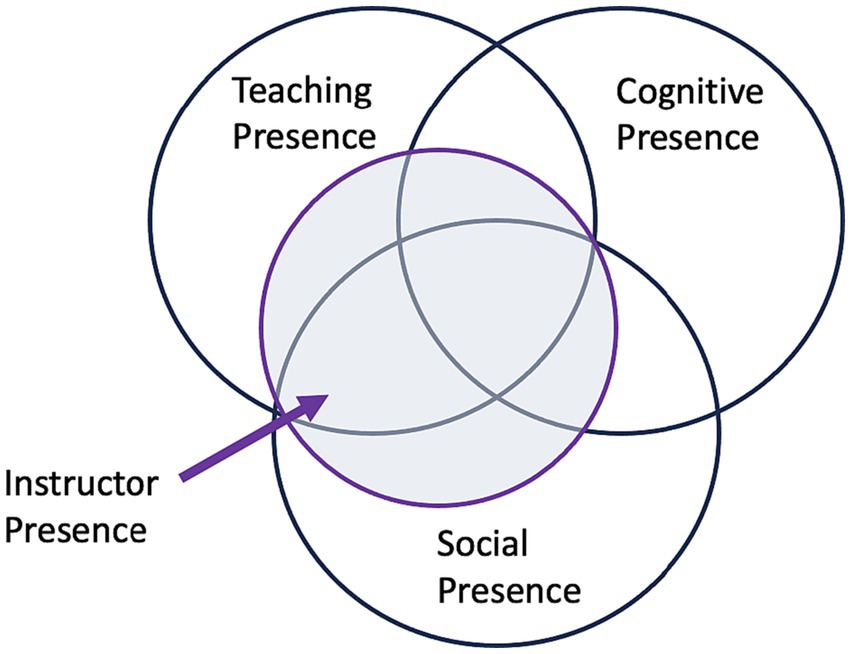

The theoretical framework leveraged for this study is the construct of instructor presence. Instructor presence (Figure 1) is comprised of three key components: behaviors, actions, and position. Behaviors refer to how an instructor interacts with students in an online environment. Actions are the specific things an instructor does to project themselves as a real, engaged person to students. Position relates to how an instructor situates themselves socially and pedagogically within the online community. In other words, instructor presence includes the behaviors and actions an instructor displays, as well as the position they establish through roles, styles, and interactions with students (Feeler, 2012; Richardson et al., 2015). This multidimensional concept encompasses not just what instructors do, but how they situate themselves in relation to students in a virtual setting.

Research question

In this study, we aim to answer the following question: What do students articulate as significant factors in establishing and maintaining an effective online instructor presence? Concerning the guiding question, it is important to clarify that this study focuses on the instructor presence component of the CoI framework theory, which connects both cognitive and social presence (Richardson et al., 2015).

While establishing presence is essential for successful online learning, there has been limited qualitative research exploring instructor presence from the graduate student viewpoint, particularly within blended asynchronous and synchronous environments and instructional technology programs. This study aims to uncover practical techniques for relationship-building, engagement, and interpersonal connections by interviewing graduate students regarding the specific behaviors, actions, and positions that promote meaningful instructor presence in virtual classrooms.

Methods

Approach

The study was carried out using a qualitative approach, as the descriptive, exploratory nature of qualitative inquiry contributes unique value to expanding knowledge and informing policy, practice, and research in ways quantitative data alone often cannot (Merriam and Tisdell, 2015). Qualitative methods like interviews and observations enable the collection of personalized, descriptive data based on individuals’ lived experiences in their own words (Mohajan, 2018). Additionally, the inductive approach of qualitative research allows unexpected themes and insights to emerge directly from the data. This can challenge assumptions and lead to new theories and directions for future research (Creswell and Poth, 2018).

This project stems from discussions about the role of instructor presence in fully online courses. The aim was to understand how graduate students define and experience effective instructor presence. Through an iterative process, the authors identified the guiding research question and qualitative methods to elicit learners’ interpretations of presence-building strategies.

Researcher descriptions

The authors have research expertise in instructional technology and online learning. Author #1 holds a Ph.D. in Instructional Leadership focused on technology and presence. Author #2 brings experience from graduate degrees in Instructional Technology and Language/Literacy. Their training positioned instructor presence in blended environments as a key research interest.

Their familiarity with graduate distance learning allowed them to sensitively capture learner perspectives through interviews, surveys, and focus groups. Professional relationships with the students enabled the coordination of data collection. The authors’ combined expertise in online pedagogy and qualitative methods facilitated gathering insights into meaningful presence-building behaviors, actions, and dispositions.

Participants

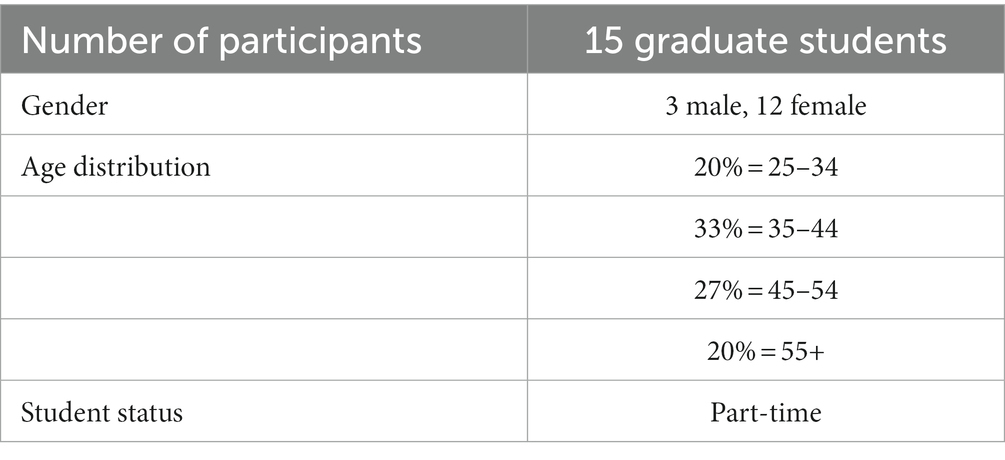

The study participants (Table 1) were graduate students (n = 15) enrolled in a 100% online instructional technology program at an R1 university in the southeastern United States. All students were enrolled in at least one online IT course during the Fall 2022 semester and had completed at least one IT course before the Fall 2022 semester. Among the students, 20% (n = 3) were men and 80% (n = 12) were women. The duration of the study was approximately 9 weeks.

In this study, while the participants’ program is 100% online, their collective experience was not 100% asynchronous for all learners. Participants reported that several instructors in the program offered several synchronous Zoom meetings during the courses, which were optional for students to attend. It is possible that the synchronous components may have altered the way the study participants would have responded in a 100% online and 100% asynchronous instructor presence.

Participant recruitment and selection

Author #1 obtained IRB approval to conduct the research before participant recruitment began. To recruit participants, Author #1 emailed all graduate students enrolled in the instructional technology master’s degree program at an R1 university and invited them to participate if they met the criteria (i.e., a student in good standing at the R1 university, completion of one course in the instructional technology master’s degree program, and currently enrolled in one course in the instructional technology master’s degree program during the semester in which the study was being conducted).

If a learner responded to the initial email indicating they fit the criteria of the study and were interested in participating, Author #1 replied by email and delivered more information on study participation and the consent document. Before signing their consent forms, participants were given the chance to ask questions about the study and their participation. Over 9 weeks, 15 graduate students took part in the study.

While all 15 students participated in the semi-structured interviews, time limitations and schedule constraints resulted in some students participating in the subsequent survey and focus group more than others. Ten students participated in the open-ended survey and four students participated in the focus group.

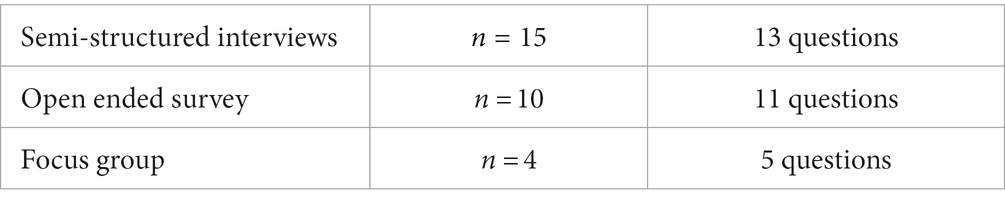

Data collection tools

To examine the factors that participants identified as significant in establishing and maintaining an effective online instructor presence, we conducted semi-structured interviews, an open-ended survey, and a focus group (Table 2). During each data collection segment of the study, participants were asked to articulate their insights, observations, and experiences related to effective instructor presence methods, strategies, and behaviors in online courses at the R1 university.

Since this is a qualitative study, using multiple methods with open-ended questions allows for a more comprehensive exploration of students’ perspectives on instructor presence. Here is how each method contributes: The semi-structured interviews with all 15 participants provide rich, descriptive details about their experiences and thoughts on instructor presence. The open-ended nature gives flexibility to probe and clarify. The qualitative survey completed by 10 out of 15 students allowed for gathering more perspectives. The survey questions also corroborated findings from the interviews. The focus group, despite its small size with 4 participants, brought out collaborative reflections not found in the individual interviews.

Though each method had limitations, the convergence of findings across the datasets strengthens credibility through triangulation. The multi-method approach provides a well-rounded understanding of how students experience instructor presence.

Semi-structured interviews

Semi-structured interviewing is a common technique for exploratory research aimed at gathering rich, descriptive insights from participants. This method combines structure with flexibility (Longhurst, 2003). The interviewer prepares core questions in advance but can also ask follow-up questions tailored to the participant’s responses. This conversational style provides more flexibility than fully scripted interviews or surveys (Given, 2008). As a result, semi-structured interviews allow researchers to collect more detailed, nuanced qualitative data about people’s lived experiences, perceptions, and opinions (Adams, 2015).

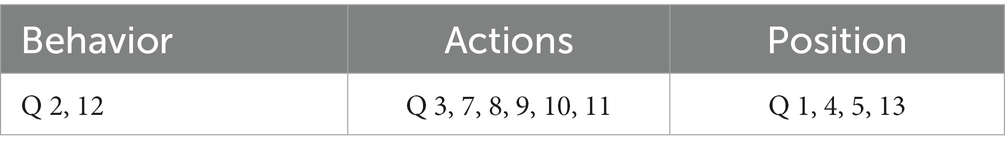

Before conducting the semi-structured interviews on Zoom, the authors created 13 predetermined, open-ended questions (Supplementary Appendix A). The interview questions were based on the three key components of instructor presence: behaviors, actions, and conditions (Richardson et al., 2015). Table 3 shows the three instructor presence components and the corresponding semi-structured survey questions.

For example, interview question 3, “In what ways and how were you and your peers introduced to the course by the instructor?” relates to the “position” component of instructor presence. Interview question 12, “How is feedback shared with students?” corresponds to the “behavior” component of instructor presence.

As the interview questions were semi-structured, the authors adapted to the participants’ responses during the interview. The authors were able to ask probing questions and get to know the individual participants on a more personal level, which is valuable for the current study and future research (Jain, 2021). As outlined in the consent form, the interviews were video and audio-recorded. The length of each interview was approximately 30–45 min.

Survey

An 11-item survey (Supplementary Appendix B), administered through Qualtrics, was used as a data collection tool after the semi-structured interviews were completed and analyzed. The qualitative results reinforced some of the interview findings, lending more credibility to the study through method triangulation. By conducting the survey post-analysis, the authors gathered more perspectives, gained insights into the participants’ opinions, and were better prepared to plan and conduct the survey (Jain, 2021).

To develop the survey questions, the researchers examined the 13 interview questions and determined that more information was needed from the participants in terms of specific examples of instructor presence behavior, actions, and position, description of how instructors can improve the effectiveness of their behavior, actions, and position, and how the behavior, actions, and position affected the participants’ own behavior, reactions, and perceptions. Questions included, “What examples of effective online instructor presence can you list?” and What is your reaction when an effective instructor presence exists in an online course?”

Focus group

Focus groups allow researchers to efficiently gather a breadth of perspectives, attitudes, and beliefs about a topic in a short time span (Krueger and Casey, 2015). The group discussion dynamic sparks ideas and insights that individual interviews may not reveal, as participants hear others’ views and experiences (Stewart et al., 2007). Interaction within the group highlights areas of agreement, disagreement, and nuance in perspectives (Morgan, 2019). While small focus groups can generate fewer data and tentative findings compared to larger samples (Stewart et al., 2007), this data collection method reinforces and complements the semi-structured interview data and survey results, producing insights beyond the sum of individual contributions.

For this study, participants were asked to respond to five focus group questions (Supplementary Appendix C). By conducting the focus group after analyzing the survey replies, the authors were better able to create targeted focus group questions to clarify and gain more detailed responses.

To develop the focus group questions, the researchers reviewed the 11 survey questions and decided that the concepts of trust, academic barriers, community, and the day one course experience should be examined in more depth. Examples of those questions include: “Thinking about the concept of trust in any online course, describe how or ways in which this can be established through instructor presence” and “Thinking about the first day of an online course, how can you be introduced to that course in a very effective way? What would that look like?

The focus group lasted 1 h and was conducted with four participants. Four to seven participants are standard for focus group data collection to gain additional insights into the participants’ viewpoints and perceptions (Krueger and Casey, 2000) related to effective instructor presence strategies and methods in courses.

Data analysis

Transcripts from the semi-structured interviews were analyzed using inductive and deductive content analysis. Content analysis is a qualitative research method used to systematically analyze written, verbal, or visual communication artifacts (Elo et al., 2014). It involves coding and categorizing data to identify themes, patterns, biases, and meanings represented in texts or images (Vaismoradi et al., 2013). Overall, content analysis is a flexible method used to generate knowledge, new insights, representations of facts, and practical guidance by producing data from examining human communications (Krippendorff, 2018).

Transcripts from the focus group and the text document from the open-ended survey were analyzed using inductive content analysis. In the deductive analysis, the following instructor presence components were adopted: behaviors, actions, and position.

Author #1 transcribed the interview and focus group audio files verbatim using Rev.com. Participants’ responses to the open-ended survey were exported from Qualtrics into a text document. Following an inductive approach to coding, Author #1 and Author # 2 reviewed the transcripts and text document for accuracy and read the transcripts and text document to become familiar with the data.

The transcripts and the text document were analyzed using inductive and deductive content analysis. Inductive coding was used to identify codes, categories, and themes from the data (Ezzy, 2002; Richardson et al., 2016). In the deductive analysis, the instructional presence components were also applied.

The data were coded manually and with NVivo, a qualitative data analysis software tool. Throughout data analysis, Author #1 and Author #2 independently coded the transcripts and text document and met weekly to discuss codes and apply cross-case analysis. Cross-case analysis allows authors to locate and discuss similarities and differences articulated by the participants (Richardson et al., 2016) regarding their perceptions of effective online instructor presence. To determine the final codes used in the data analysis, the authors met to examine, discuss, and resolve any discrepancies to reach a 100% consensus (Creswell, 2014). After coding, the data was examined for patterns and subsequent themes to answer the study’s research question.

Results

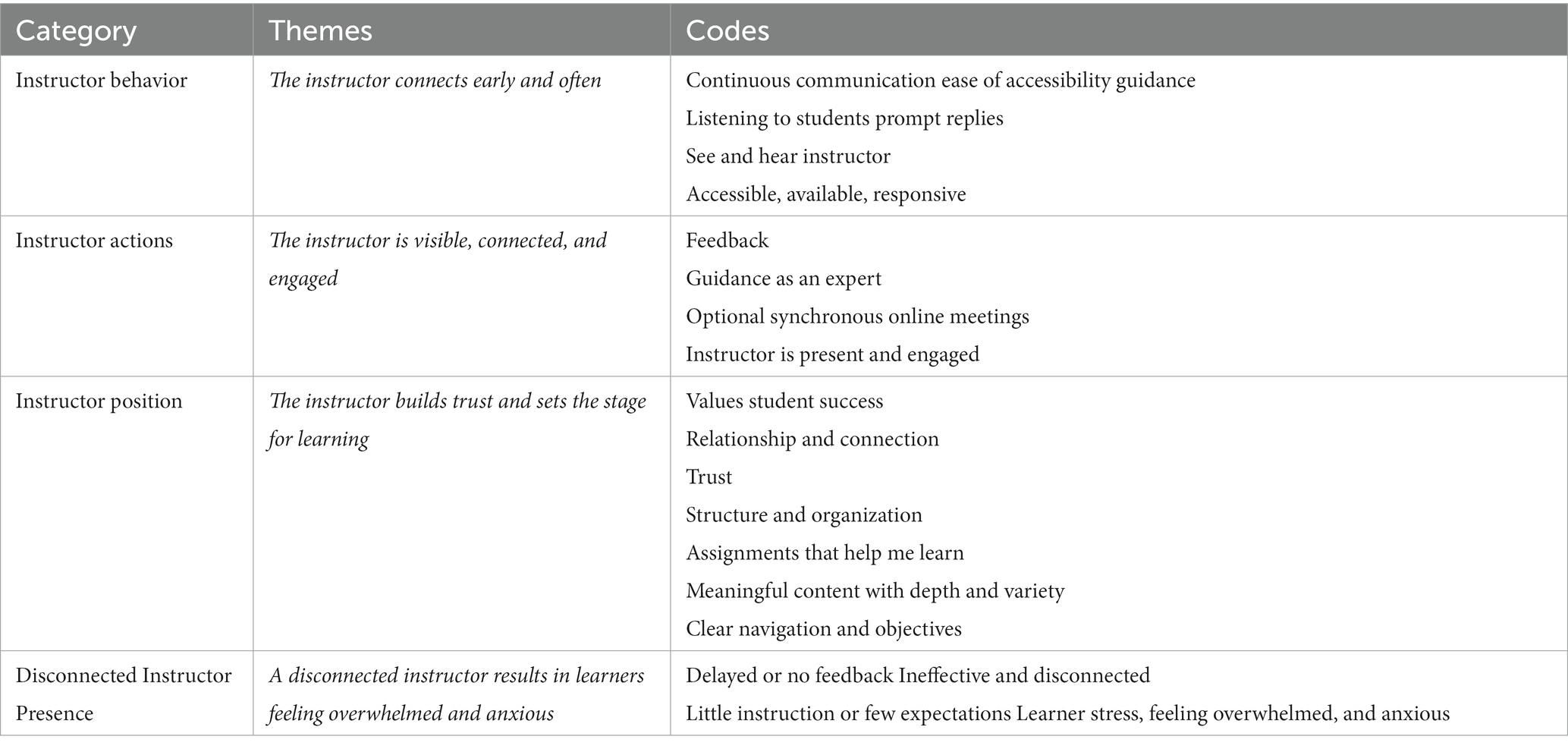

Based on the analysis of 15 interviews, 10 surveys, and one focus group, the findings are categorized by data collection method to answer the research question: What do students articulate as significant factors in establishing and maintaining an effective online instructor presence?

Findings from the semi-structured interview

Several themes emerged in relation to the semi-structured interview questions (Supplementary Appendix A).

The resulting themes, as seen in Supplementary Appendix are: (1) The instructor connects early and often, engaged, (2) The instructor is visible, connected, and engaged, (3) The instructor builds trust and sets instructor presence results in students feeling, and (4) Disconnected instructor presence results in students feeling overwhelmed and anxious.

The instructor connects early and often

In their descriptions of Facilitating Discourse, several of the participants (n = 11) indicated that continuous communication is necessary for students to be successful in online courses. Many participants (n = 7) described that weekly videos from the faculty helped them connect to the course material and the instructor, along with course announcements and group or individual emails. One participant commented:

I think those weekly videos are a good place to address misconceptions from the past week or like, yeah, I noticed several of you made the same error in this assignment. Here's a different way of thinking about it

Visibility of the instructor or being able to see and hear the instructor was viewed by many participants (n = 12) as a crucial part of a successful, satisfying online learning experience. Visibility also included an instructor who interacts, pays attention to the students’ needs, and is present in the course. One participant described:

Being able see the faces of the professors makes things really easier to go through. It makes you feel more confident and actually makes it easier to communicate with your professors. the instructor does a weekly recording of themselves, kind of going over the material. So you still get to see their face, you still get to interact with them.

Additionally, participants (n = 10) emphasized that ease of communication with and accessibility to the instructor as important factors. Participants (n = 10) also described that they enjoyed autonomy in online courses but desired the ability to reach out to the instructor and receive a prompt reply. Most participants (n = 10) expected an instructor’s reply within 24 h. Participants also felt less stress in an online course if they believed they could reach out to an instructor with no repercussions. One participant shared:

I think is just the responsiveness of an instructor. if someone is able to respond to me within 24 hours, I'm pretty much like, oh wow, that's awesome.

The instructor is visible, connected, and engaged

Nearly every participant (n = 12) agreed that effective online instructor presence means that the instructor is accessible, available, and responsive to students. Equally important to participants was that the instructor is a real person who is also engaged and approachable from day one and throughout the entire course. One participant responded:

I keep wanting to say the word prioritization, making the online course feel like it's just as important as if we were face-to-face. They are almost as engaged in the course material as the students. It is just as focused as if it were in person.

Most of the participants (n = 9) underscored that an effective online instructor presence means that the instructor values student success. One participant responded:

I do feel like that instructor is present and cares about whether or not we're actually understanding and getting the information. It's not just lip service, it's thoughtful responses.

All participants (n = 15) mentioned that quick, constructive, and detailed feedback created trust and was necessary for deep learning. Participants (n = 8) preferred feedback that conveyed positivity, and encouragement, and provided specific information on improving the quality of a submission. Several participants (n = 5) emphasized that they felt less anxiety and more trust if the instructor conveyed constructive feedback in a way that was not negative and shared that mistakes are part of the learning process and it provides an opportunity for growth, not punishment. One participant commented:

I know he will tell me if something is good or not good. So I trust that he will provide me with good information. And he always does.

One participant responded:

So, the having the opportunity to do a rough draft, get feedback and turn it in is invaluable to me. It. It gives you the opportunity to show what you already know, but it's a safe place to mess up. And I really do find that I learn more from mistakes than from what I did right.

The instructor builds trust and sets the stage for learning

When we interviewed participants about significant factors that represent or convey an effective online instructor presence, they had much share about the topic and how they experienced it.

Participants described that effective online instructor presence is demonstrated when an instructor gives students the opportunity to know them. Participants (n = 10) described cultivating feelings of trust, confidence, and support when an online instructor connects with students in a way that is deeper than surface level.

Several of the participants (n = 9) placed emphasis on the importance of being able to establish a relationship with the instructor and not feeling like just another student in the course. Part of that relationship building, according to many participants (n = 8), means the ability to see and hear the instructor. One participant explained:

When a professor establishes an online presence throughout the course, you get to really know their style. You got to see their face and interact with them a lot more, which built more of a relationship. It felt more like being in a classroom setting.

Several participants described the significance of not just learning content but learning new skills applicable to learners’ jobs and lives (n = 8) and the need to have assignments that push them out of their comfort zone (n = 4). Additionally, it was pointed out that scaffolding is crucial for deep comprehension with new information building on earlier information everything builds off the week prior (n = 7). One participant commented:

I can look at the modules and I can look at sort of the goal of each section. And I feel pretty confident that I could. Based on how is organized tell you, okay, this is what they want me to get out of this course

Several of the participants (n = 13) voiced that content depth and variety are extremely helpful as a learner. Many participants voiced that more than a textbook was needed to understand and digest the course material, describing that the use of video, podcasts, articles, visuals, and short summaries provide different perspectives on a particular topic. One participant explained:

I could like go for a walk right, and listen rather than just like sitting more. I can read the notes for this or I can listen to it and I absorb things better if I read them than if I just hear them.

It was also expressed by participants (n = 11) that they desired an expert instructor, both in the synchronous and asynchronous environments, who was an established professional with the ability to effectively teach online. Participants expected that instructors be an expert in the subject being taught.

Disconnected instructor presence results in students feeling overwhelmed and anxious

Several participants (n = 7) talked about the learner stress, feeling overwhelmed, and anxious. Students relayed that these feelings surfaced after viewing the way the instructor presents the structure, flow, and workload required in a course. Relatedly, if the online course navigation is confusing, the content is outdated, or the instructor is uncomfortable with technology, it triggers feelings of learner stress and unease. Several participants (n = 4) expressed that feelings of being overloaded caused them to drop a course. One responded:

There was one class that I withdrew from because I felt overwhelmed. The first thing I did as a student, I would go through and look at every module, and if I felt like, oh my goodness, this is going to be overwhelming, or I do not feel like I can do this.

Nearly half the participants (n = 7) described the frustration caused when the instructor offered few or no instructions and few or no expectations of the students in the online course. Additionally, a few participants (n = 3) mentioned feeling tense and confused when an instructor changed due dates and did not notify the students. One participant explained:

I think in this class I'm in, it's been taking like three weeks for me to get feedback on my assignments.

Delayed communication and delayed assignment feedback, especially when the feedback lacks depth or substance caused participants (n = 7) additional stress and feeling overwhelmed. One participant responded:

If I send you an email and you don't respond for a week, there's challenges with that as a virtual student.

Several participants (n = 8) expressed concern and frustration with ineffective instructor presence, specifically when an instructor is disconnected, does not participate, or communicate, and is not engaged with the course or the students. One participant shared:

You're just standing back there as God of some sort that just watches it all happen.

Additional frustration was expressed by participants (n = 4) who perceived assignments to be punitive, worth zero credit, or were related to using technology for technology’s sake and not pushing learning or skill-building forward. One participant responded:

It was basically writing a paper every single week, which I got to say was not my favorite. And it reflected that. When I did my course evaluation, I also said that’s not effective because it’s just punitive at that point.

Another participant replied:

This specific class, we have quizzes at the end, but personally, I don't like the quizzes because he doesn't give us a value on them. He gives us a zero. And to me a zero is like just completely devastating because I take my studies very seriously.

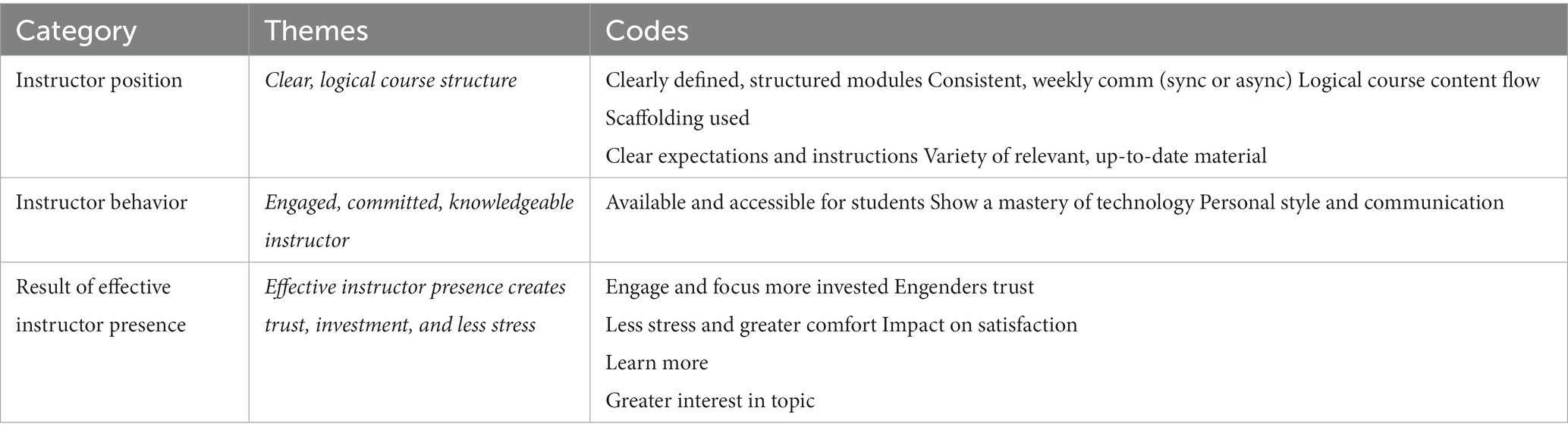

Findings from the survey

Several themes emerged in relation to the open-ended survey questions (Supplementary Appendix B) asking participants (n = 10) to answer questions based on the three components of online instructor presence: behavior, actions, and position. The resulting themes (Table 5) were: (1) Clear, logical course content and structure, (2) Engaged, committed, knowledgeable instructor, and (3) Effective instructor presence creates trust, investment, and less stress.

Clear, logical course content and structure

Most of the survey participants (n = 8) desired clear expectations and instructions from the instructor from day one and throughout the course. Similarly, participants (n = 8) identified that a logical flow of course content reflected effective online instructor presence and mentioned that the organization of the course should be easy to understand. All survey participants (n = 10) agreed that effective online instructor presence means that the instructor has prepared the course with clearly defined, structured modules that are scaffolded and built from a base of previous understanding. One participant commented:

As clearly as possible. As structured as possible. Built-in flexibility when appropriate. For me, start with the big picture and zoom down into the specifics. I know not everyone sees the world that way, but it helps me.

Many of the participants (n = 8) agreed that it is crucial to have relevant, up-to-date content in a course. Participants also expressed that they want to know why a task or assignment is important, not just do it because it is required.

Engaged, committed, knowledgeable instructor

All survey participants (n = 10) shared that effective online instructor presence was reflected by being available and accessible for students throughout the entire course. This included the instructor responding quickly and fully to emails and communication from students, without making students feel intimidated. It also means providing students a timeframe during which they can expect their grades and grading promptly with the addition of rich, critical feedback for improvement. One participant explained:

Comment on the positives. Critique the negatives with an eye toward improvement. I do enjoy a gold star, whether through video or written comments, but I appreciate hearing the instructor's perspective.

A need for consistent, weekly communication from the instructor was also discussed by all participants in their responses (n = 10). That communication can take many forms, including posting a video introduction, holding a synchronous welcome meeting, in addition to optional Zoom sessions, and sharing text, video, or audio updates and encouragement. One participant shared:

A rousing speech! I'm with you. I'll help you. You can do this! Here are tips to succeed.

Effective instructor presence creates trust, investment, and less stress

Nearly all the participants (n = 9) shared that effective online instructor presence helped them engage, invest in the course material, put forth more effort, and focus on learning and skill development. Additionally, participants explained that effective online instructor presence causes them to feel less stressed about assignments. Participants (n = 9) expressed that effective online instructor presence engenders trust in the instructor and facilitates greater comfort and interest in the course topic. Additionally, participants (n = 7) shared that effective online instructor presence impacts student learning and satisfaction. One participant explained:

I feel that I do better in courses where there is an effective teaching presence. Generally, it means the difference of me checking boxes and engaging with material. It increases my investment and I grasp more information.

Most of the participants (n = 8) reported that an instructor’s personal style and communication are reflective of effective online instructor presence, particularly in terms of the instructor’s personality and compassion. Participants commented that when instructors share their personal style it establishes credibility and introduces them as a real person.

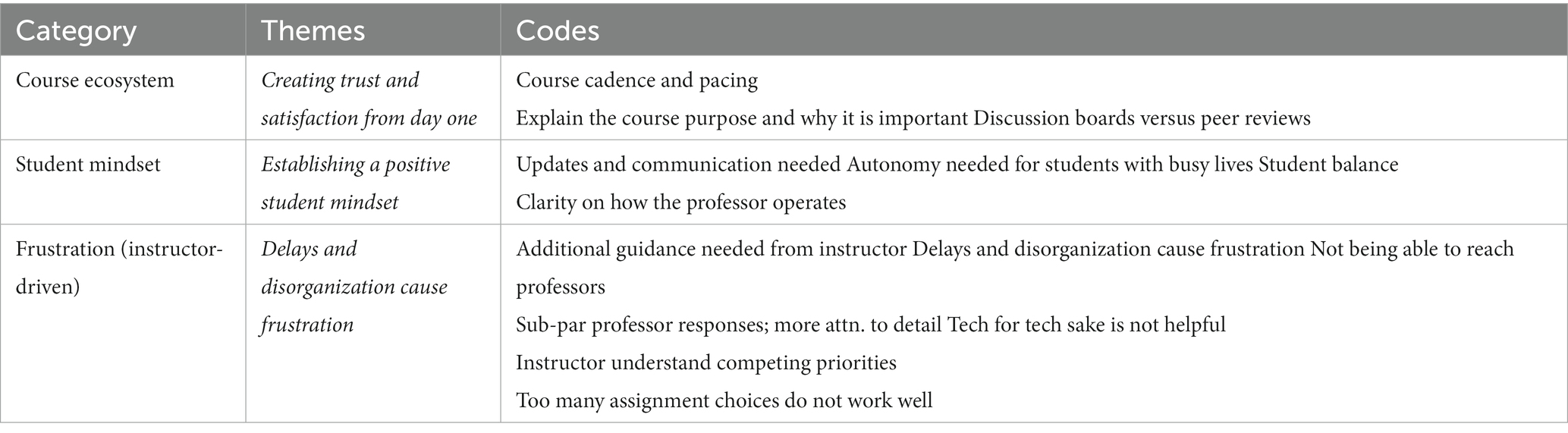

Findings from the focus group

From examining the focus group responses, several themes were determined after analyzing the data to gain additional insights into the participants’ viewpoints (Krueger and Casey, 2000) related to effective online instructor presence behavior, actions, and position. The resulting themes (Table 6) were: (1) Creating trust and satisfaction from day one, (2) Establishing a positive student mindset, and (3) Instructor delays and disorganization cause frustration.

Creating course satisfaction from day one

All participants (n = 10) indicated that effective online instructor presence strategies include creating a comfortable course cadence and pacing. Participants shared that chunked content helped avoid cognitive overload and uniformity with assignment due dates helped reduce stress levels. Additionally, participants stressed the importance of consistent course structure and organization, including inside the individual modules and module sections. One participant explained:

I know that for every class it’s split into the different like modules and sections, but if there’s consistency in the way that each of those look, it makes it a lot easier to be able to go in and say, okay, I need to start here. Look at this, look at this. And just that consistency definitely helps me to be able to be successful.

Participants (n = 10) stressed the need to understand why the course was important and the reason why the context, activities, and skills are necessary. Other participants (n = 5) explained that receiving context and information from the instructor before the course began helped ground them in the course and assisted students in more quickly assimilating to the course requirements and content. One student shared this about day one of a course:

Just giving the syllabus and the course schedule I feel like is not enough. I feel like there needs to be like a video or a Zoom or something where there can be a little bit more like conversation about the course.

Participants (n = 10) had a lot to say about discussion boards and peer reviews. Most participants (n = 9) shared that they disliked discussion boards, found them stressful, and questioned the value and purpose of this activity. Several participants (n = 5) debated whether the purpose of discussion boards was to interact with peers or whether it was to determine if students understood the material, citing that the activity should not be included because it’s always been included as part of a course. The participants (n = 9) also expressed that the ability to communicate with the instructor easily and quickly, if needed, resulted in satisfaction and the perception of effective online instructor presence.

Establishing a positive student mindset

Most participants (n = 8) agreed that autonomy and the ability to work at their own pace in an online course is needed for graduate students with busy lives. Additionally, many participants (n = 9) described that it takes time and gaining trust in the instructor before it feels comfortable to engage and communicate inside the course and about the material. One participant responded:

I’m not ready to just launch into the, the bulk of the content of the course until I feel like I’m really clear on how this instructor works.

Participants (n = 5) were also successful in establishing a positive student mindset when they could have productive conversations with the instructor. It was also helpful for participants to have access to instructors at times that were convenient for busy, working adults.

Instructor delays and disorganization cause frustration

All participants (n = 10) expressed concern regarding the inability to contact or receive guidance and answers from instructors, particularly after hours when the student is required to work a 9–5 day. One student explained:

I do not feel like I can ever get that communication and that foundation, it, it’s almost like I do not trust that professor to take care of me, so to speak.

Another student commented:

I work during the traditional school day, so if a professor is only going to reply to things or whatnot during the workday, it can be very hard to have an open back-and-forth of communication and get all of the questions I need answered while I’m trying to also wrangle 37 students at the same time. So being able to communicate with my professors during the evening is the best thing for me and not being able to do that is a roadblock.

Other participants (n = 4) described frustration over receiving incomplete or vague instructor responses and shared their annoyance when instructors do not pay attention to detail or respond to emails or questions thoroughly. One participant responded:

Then there are some [instructors] who like answer the first thing and, and that you are left with two other questions that were never addressed. And so that’s when I start to get stressed out. Well, I need these other two questions answered, but they already did not answer them.

Many participants (n = 8) articulated confusion and frustration over course expectations not conveyed by the instructor in a timely manner or missing information in the syllabus or instructions. Additionally, the participants expressed that it is overwhelming to have work to complete in week one of the course without advance notice or information in the course on day one.

To pile all on the very first day if the student is like juggling a number of classes, just really front loads and can be kind of caused this flurry of stress right at the very beginning. It is really defeating to feel like I’m already behind the ball.

Other participants (n = 3) described concerns surrounding decision fatigue when an instructor offers too many choices or options when completing an assignment or when the assignment appeared to be using technology for technology’s sake.

I’ve had a course before where the professor had this really cool technology tool that he wanted us to use, but nobody could figure out how to use it. And there were so many emails and Zoom calls of us trying to use it that the actual purpose of the assignment kind of got lost behind this technology tool.

Trustworthiness

We employed several strategies to ensure the trustworthiness of this qualitative study’s findings:

Credibility: Using three different data collection methods (interviews, a survey, and a focus group) allowed for triangulation of the results. Additionally, we utilized member checking by sharing preliminary findings with participants to check the accuracy of our interpretations.

Transferability: We provided thick description of the context, participants, and findings to enable readers to evaluate the potential transferability to their settings. However, as a small sample at one institution, transferability is limited.

Dependability: We utilized code-recode strategy by coding the transcripts twice with a 1-week interval and comparing for consistency. We also maintained an audit trail detailing the data collection, analysis, and interpretation processes.

Confirmability: As researchers familiar with the graduate program context, we practiced reflexivity through reflective journaling and memoing to surface any biases or assumptions. We used direct participant quotes to ensure findings were shaped by their perspectives rather than our own.

All three data sources revealed the importance of timely, caring communication for effective instructor presence. The need for instructors to be engaged and accessible was also a consistent theme across data sources. Additionally, findings from all three sources converged around students’ desire for authentic relationship-building from instructors. Participants’ need for clear course structure and organization emerged in both interviews and the survey. The interview findings highlighted reducing negative emotions, which did not appear in other data.

While qualitative studies cannot demonstrate generalizability, these strategies bolster the credibility and trustworthiness of the findings within the framing of a small, exploratory study. Further research is needed to assess the transferability of these instructor presence insights to other student populations, disciplines, and institutional types.

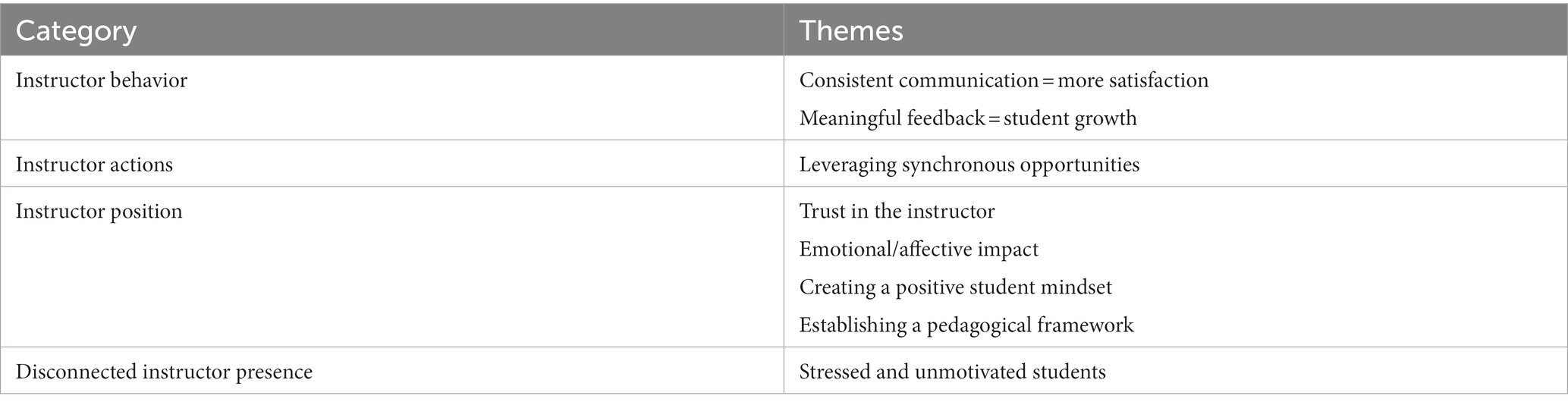

Discussion

This qualitative study investigated effective online instructor presence through the lens of graduate students enrolled in a master’s-level instructional technology program. The study’s finding that instructor presence positively impacts satisfaction aligns with previous studies showing links between presence and student satisfaction (Khalid and Quick, 2016; Kyei-Blankson et al., 2016). The importance of timely communication and feedback found in this study echoes previous work identifying these as key strategies for presence (Trammell and LaForge, 2017; Van Wart et al., 2019). Additionally, participants emphasized the need for an expert instructor, which aligns with prior literature on the importance of subject matter expertise for presence (Wang and Liu, 2020).

The findings (Table 7) also provide deeper insights into instructor presence in a blended learning environment. The study also revealed new distinctions around relationship-building, emotions, and mindset as related to instructor presence, in addition to the importance of trust and establishing a positive student mindset. The participants in this study clearly desired some synchronous aspects in addition to purely asynchronous instructor presence-building. Additionally, participants identified specific pedagogical approaches like scaffolding, that add to general strategies like timely feedback.

Instructor behavior

Consistent communication = more satisfaction

Participants in the current study echoed what has been shared in the academic literature, that regular and high-quality interaction in online distance education courses (Beese, 2014). The study participants cited that effective online instructor presence entails consistent, weekly communication, either synchronously or asynchronously. As stated in the academic literature, this includes how the instructor interacts with learners throughout the course and the response from the instructor when faced with a variety of situations and circumstances (Van Wart et al., 2020). The participants articulated that especially during pinch points in the semester (e.g., the start of the course, assignment due dates, end of the course) it is crucial to have ease of instructor accessibility, prompt replies and guidance, and an instructor who listens to students.

Participants in the study clearly articulated that positive, constructive instructor communication and interactions with the instructor, are tied to their satisfaction, which is also supported by the academic literature (Akyol and Garrison, 2008; Arbaugh et al., 2008; Khalid and Quick, 2016, Um and Jang, 2021). Additionally, as found in this study, and in existing research, learners with higher satisfaction are more apt to have tenacity, perseverance, and be more invested in learning (Um and Jang, 2021).

Meaningful feedback = student growth

As shown in the current literature, the study’s participants also articulated the need for quick, customized, constructive, and detailed feedback (Richardson et al., 2016; Wang and Liu, 2020). Participants preferred constructive feedback that provided specific information on improving the quality of a submission. Several participants shared that they preferred feedback that provided an opportunity for growth. Many of the study participants also enjoyed optional synchronous online meetings that contained substantive information and stressed the importance of receiving instruction from an expert on the topic being studied in the course. Participants in the study also reported that meaningful feedback helped them engage and focus more on the course.

Instructor actions

Leveraging synchronous opportunities

The study results indicate that participants valued replicating some of the connection and visibility of face-to-face instruction in online contexts. Appreciated the ability to see and hear instructors synchronously at times, which mirrors aspects of in-person courses. Leveraging synchronous tools is a strategy online instructors can leverage to increase presence and visibility while retaining asynchronous flexibility. Synchronous spaces can enhance social presence, allow instructor personality to shine through, and provide dedicated relationship-building time apart from asynchronous content delivery.

Instructor position

Trust in the instructor

One theme realized during data analysis in the current study was the concept of trust as it relates to effective online instructor presence. Specifically, the study participants articulated that when trust in an online instructor is developed and maintained, it leads to a more effective and satisfying learning experience.

The concept of trust, as directly related to instructor presence, has received very limited attention in the academic literature. Sheridan and Kelly (2010) mention trust as an indicator of belonging and community building, Akyol and Garrison (2008) cite social presence and its role in facilitating safety and trust in communities of learning, and Shea et al. (2006) discuss trust in the process of developing a learning environment and development of trust as a component of effective learning communities.

Trust in the instructor, as a theme in the current study, as described by participants, was created when an instructor values student success and when students can develop a relationship and connection with the instructor.

Emotional/affective impact

Instructor presence has significant emotional and affective implications for students. The results of this study revealed students often feel stress, anxiety, frustration, and feeling overwhelmed in online courses with poor instructor presence. Conversely, effective instructor presence helped mitigate these negative emotional states. As complex learners, students’ cognitive engagement and academic success in online courses are deeply intertwined with their emotional experiences and affective states. Instructors must be cognizant of the emotive impact their presence can have, from providing reassuring course introductions to transparent communication reducing uncertainty. While more research is needed, instructors can employ strategies like conveying empathy, checking in on student well-being, allowing revisions to reduce anxiety over perfectionism, and explicitly addressing the human need we all have for connection and relationship even in digital spaces. By proactively fostering positive emotional experiences through how presence is established, instructors can profoundly shape the learner’s holistic journey beyond solely academic goals. The affective and emotional aspects of online learning deserve ongoing attention.

Establishing a positive student mindset

Participants also shared a concept that has not been extensively examined in the literature related to an effective online instructor presence: the ability to establish a positive student mindset. Participants in this study articulated a hesitancy to launch into or fully engage and commit to working in a course until they are very clear on how an instructor operates in the online course environment. Specifically, when participants felt less stress and greater comfort in a course, it was easier to establish a positive student mindset. The study participants shared several ways that an instructor could assist students with establishing a positive mindset or approach: when autonomy was extended to students, including the ability to work at a student’s own pace, especially for graduate students with busy lives.

Additionally, participants articulated that the ability to establish a positive student mindset was possible when students felt the instructor valued student success and when students felt a relationship and connection with the instructor was authentic. Many of the participants agreed that it was also helpful when the instructor was perceived to be encouraging and expressed that mistakes were expected and part of the learning process.

Additionally, several participants described that it could take time to establish a positive student mindset, especially if instructors do not share facets of their style and personality. Once a positive mindset can be established, the more quickly students feel comfortable engaging and communicating inside the course and about the material.

Establishing a pedagogical framework

As articulated by participants in the current study, many factors, including different aspects of instructor presence, impact the online student experience, as detailed in the current academic literature (Farrell and Brunton, 2020). Specifically noted by study participants were factors including clearly defined objectives, well-structured modules, logical course flow, scaffolding, easy navigation, and clear expectations and instructions. In addition, participants in the study also desired consistency in modules, assignments that help students learn, meaningful content with depth and substance, and a variety of relevant, up-to-date material delivered in audio, video, text, and images. As discussed by participants, an instructor should have a mastery of technology and technology tools, as described by Singh et al. (2022).

Disconnected instructor presence

Stressed and unmotivated students

As has been cited in the academic literature, a lack of instructor presence negatively impacts students’ success. An instructor who provides little or no interaction with students also influences online course dissatisfaction (Cole et al., 2014), which can lead to retention issues (Allen and Seaman, 2013). Additional factors cited in the literature representing a disconnected instructor presence include a lack of academic community and no support available from instructors (Zembylas, 2008; Farrell and Brunton, 2020). These components foster students’ decreased motivation and feelings of isolation (Zembylas, 2008; Farrell and Brunton, 2020).

As cited in the current study, participants expressed frustration and disappointment in many of the following areas: delayed feedback or missing feedback, insubstantial instruction, few expectations shared by the instructor, sub-par professor responses, little attention to detail, delays and disorganization, inability to reach instructors, and instructors using technology only for technology’s sake. As a result of a disconnected or absent instructor presence, learners cited feelings of stress, feeling overwhelmed, unmotivated, and anxious. Based on feelings of feeling overwhelmed, several participants dropped out of previous online courses.

Conclusion

This qualitative study explored graduate student perspectives on effective online instructor presence within a master’s program. Through interviews, a survey, and a focus group, insights emerged into behaviors, actions, and dispositions students find meaningful for presence.

Key findings indicate students value early relationship-building through consistent participation, authentic personality-sharing, and learner-centered course design. Results reveal effective instructor presence fosters trust, satisfaction, engagement, and positive mindsets while reducing negative emotions. Students preferred visible, accessible instructors who connect through prompt communication, constructive feedback, and active listening.

While limited to one context, these learner-centered insights suggest intentional instructor presence is critical in virtual classrooms and profoundly shapes holistic learner experiences. Results provide an initial framework to inform professional development and identify high-impact presence strategies tailored to graduate contexts. Further research across diverse settings would strengthen framework development.

By understanding and implementing relationship-building, participatory, responsive, learner-focused approaches students find meaningful, instructors can enhance presence to improve instructional quality, build trust and satisfaction, and empower learners. This study offers a starting point for identifying key presence-building approaches in graduate online education.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, the sample comprised graduate students from a single instructional technology program who are not representative of all online learners. Additionally, the perspectives come from students currently enrolled in online courses at one R1 university. The findings may not generalize to other graduate programs, undergraduate contexts, or two-year colleges. Further research should gather data from diverse student populations and institutions to strengthen transferability.

Additionally, this study was limited to asynchronous online courses. Comparing outcomes between asynchronous and synchronous environments could provide useful insights. The data collection methods of interviews, a survey, and one focus group, while allowing for triangulation, provide a small sample size. Expanding the sample size through quantitative analysis could reinforce the qualitative findings.

Implications for future studies

This study establishes a foundation for further inquiry into learner perspectives on effective online instructor presence. Additional research should explore presence-building from the instructor’s viewpoint through interviews and observations. Comparing student and instructor interpretations could reveal disconnects to address through training.

Longitudinal data collection could provide a richer understanding of how students’ preferences and needs related to online presence evolve over time. Studying presence across different graduate disciplines and course formats would highlight variations in strategies.

Finally, a large-scale quantitative analysis of the relationships between specific instructor presence-building techniques, student satisfaction, and learning outcomes would extend this exploratory study. Findings could inform comprehensive framework development to optimize online instruction across diverse contexts.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Alabama. The research was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in the study was provided by the participants.

Author contributions

LM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SB: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1271245/full#supplementary-material

References

Adams, W. C. (2015) Conducting Semi-Structured Interviews. In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation, (Eds.) J. S. Wholey, H. P. Harty, and K. E. Newcomer, (Wiley), 492–505.

Akyol, Z., and Garrison, D. R. (2008). The development of a community of inquiry over time in an online course: understanding the progression and integration of social, cognitive and teaching presence. JALN 12, 3–22. doi: 10.24059/olj.v12i3.66

Allen, I. E., and Seaman, J. (2013). Changing course: ten years of tracking online education in the United States. Babson Park, MA: Babson Survey Research Group and Quahog Research Group. Available at: http://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/changingcourse.pdf

Anderson, T., Rourke, L., Garrison, D. R., and Archer, W. (2001). Assessing teaching presence in a computer conferencing context. Online Learning Journal, 5. doi: 10.24059/olj.v5i2.1875

Arbaugh, J. B., Cleveland-Innes, M., Diaz, S., Garrison, D., Ice, P., Richardson, J., et al. (2008). Developing a community of inquiry instrument: Testing a measure of the Community of Inquiry framework using a multi-institutional sample. The Internet and Higher Education 11, 133–136. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.06.003

Armellini, A., and De Stefani, M. (2016). Social presence in the 21st century: An adjustment to the Community of Inquiry framework. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47, 1202–1216. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12302

Beese, J. (2014). Expanding learning opportunities for high school students with distance learning. Am. J. Dist. Educ. 28, 292–306. doi: 10.1080/08923647.2014.959343

Caskurlu, S. (2018). Confirming the subdimensions of teaching, social, and cognitive presences: a construct validity study. Internet High. Educ. 39, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2018.05.002

Clark, C., Strudler, N., and Grove, K. (2015). Comparing asynchronous and synchronous video vs. text based discussions in an online teacher education course. Online Learn 19, 48–69. doi: 10.24059/olj.v19i3.668

Cole, M., Shelley, D., and Swartz, L. (2014). Online instruction, e-learning, and student satisfaction: a three year study. Int. Rev. Res. Open Dist. Learn. 15, 111–131. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v15i6.1748

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design Choosing among Five Approaches. 4th Edition, SAGE Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks.

Elo, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kanste, O., Pölkki, T., Utriainen, K., and Kyngäs, H. (2014). Qualitative Content Analysis: A Focus on Trustworthiness. SAGE Open, 4. doi: 10.1177/2158244014522633

Farrell, O., and Brunton, J. (2020). A balancing act: a window into online student engagement experiences. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 17, 1–19. doi: 10.1186/s41239-020-00199-x

Feeler, W. (2012). Being there: a grounded-theory study of student perceptions of instructor presence in online classes (Publication No. 1266830430) [Doctoral dissertation, ProQuest LLC].

Garrison, D. R. (2015). Thinking collaboratively: learning in a community of inquiry. New York: Routledge.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., and Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: computer conferencing in higher education. Internet High. Educ. 2, 87–105. doi: 10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., and Archer, W. (2001). Critical thinking, cognitive presence, and computer conferencing in distance education. Am. J. Dist. Educ. 15, 7–23. doi: 10.1080/08923640109527071

Garrison, D. R., and Arbaugh, J. B. (2007). Researching the community of inquiry framework: review, issues, and future directions. Internet High. Educ. 10, 157–172. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2007.04.001

Given, L. M. (ed.). (2008). The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. SAGE Publications.

Jain, N. (2021). Survey Versus Interviews: Comparing Data Collection Tools for Exploratory Research. The Qualitative Report, 26, 541–554. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2021.4492

Khalid, N. M., and Quick, D. (2016). Teaching presence influencing online students' course satisfaction at an institution of higher education. Int. Educ. Stud. 9, 62–70. doi: 10.5539/ies.v9n3p62

Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. 4th Edn SAGE Publications, Inc.

Krueger, R. A., and Casey, M. A. (2000). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

Krueger, R. A., and Casey, M. A. (2015). Focus group interviewing. In Handbook of practical program evaluation, (Eds.) K. E. Newcomer, H. P. Hatry, and J. S. Wholey. (4th edn). (Jossey-Bass), 506–534.

Kyei-Blankson, L., Ntuli, E., and Donnelly, H. (2016). Establishing the importance of interaction and presence to student learning in online environments. World J. Educ. Res. 3:48. doi: 10.22158/wjer.v3n1p48

Law, K. M. Y., Geng, S., and Li, T. (2019). Student enrollment, motivation, and learning performance in a blended learning environment: the mediating effects of social, teaching, and cognitive presence. Comput. Educ. 136, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2019.02.021

Longhurst, R. (2003). Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. In Key methods in geography, (Eds.) N. Clifford, M. Cope, T. Gillespie, and S. French (SAGE), 117–132.

Lowenthal, P. R., and Dennen, V. P. (2017). Social presence, identity, and online learning: research development and needs. Distance Educ. 38, 137–140. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2017.1335172

Martin, F., and Bolliger, D. U. (2018). Engagement matters: Student perceptions on the importance of engagement strategies in the online learning environment. Online Learning 22, 205–222. doi: 10.24059/olj.v22i1.1092

McNeill, L., Rice, M., and Wright, V. (2019). A confirmatory factor analysis of a teaching presence instrument in an online computer applications course. Online J. Dist. Learn. Admin. 22, 1–16.

Merriam, S. B., and Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

Mohajan, H. (2018). Qualitative research methodology in social sciences and related subjects. Journal of Economic Development, Environment, and People, 7, 23–48. doi: 10.26458/jedep.v7i1.571

Picciano, A. G. (2002). Beyond student perceptions: issues of interaction, presence, and performance in an online course. JALN 6, 21–40. doi: 10.24059/olj.v6i1.1870

Richardson, J. C., Besser, E., Koehler, A., Lim, J., and Strait, M. (2016). Instructors’ perceptions of instructor presence in online learning environments. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 17, 82–104. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v17i4.2330

Richardson, J. C., Koehler, A., Besser, E., Caskurlu, S., Lim, J., and Mueller, C. (2015). Conceptualizing and investigating instructor presence in online learning environments. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 16, 256–297. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v16i3.2123

Shea, P., Hayes, S., Uzuner-Smith, S., Gozza-Cohen, M., Vickers, J., Bidjerano, T., et al. (2014). Reconceptualizing the community of inquiry framework: An exploratory analysis. The Internet and Higher Education, 23, 9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2014.05.002

Shea, P., Li, C., and Pickett, A. (2006). A study of teaching presence and student sense of learning community in fully online and web-enhanced college courses. The Internet and Higher Education, 9, 175–190. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2006.06.005

Sheridan, K., and Kelly, M. A. (2010). The indicators of instructor presence that are important to students in online courses. MERLOT J. Online Learn. Teach. 6, 767–779.

Singh, J., Evans, E., Reed, A., Karch, L., Qualey, K., Singh, L., et al. (2022). Online, Hybrid, and Face-to-Face Learning Through the Eyes of Faculty, Students, Administrators, and Instructional Designers: Lessons Learned and Directions for the Post-Vaccine and Post-Pandemic/COVID-19 World. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 50, 301–326. doi: 10.1177/00472395211063754

Trammell, B. A., and LaForge, C. (2017). Common challenges for instructors in large online courses: strategies to mitigate student and instructor frustration. Journal of Educators Online, 14.

Um, N., and Jang, A. (2021). Antecedents and consequences of college students’ satisfaction with online learning. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 49, 1–11. doi: 10.2224/sbp.10397

Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., and Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing and Health Sciences, 15, 398–405. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12048

Van Wart, M., Ni, A., and Lui, C. (2019). Integrating academic and social engagement: a model of interaction for online learners. Distance Educ. 40, 469–496. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2019.1681892

Van Wart, M., Ni, A., Medina, P., Canelon, J., Kordrostami, M., Zhang, J., et al. (2020). Integrating students’ perspectives about online learning: a hierarchy of factors. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 17:53. doi: 10.1186/s41239-020-00229-8

Vesely, P., Bloom, L., and Sherlock, J. (2007). Key elements of building online community: Comparing faculty and student perceptions. Journal of Online Teaching and Learning, 3.

Wang, Y., and Liu, Q. (2020). Effects of online teaching presence on students’ interactions and collaborative knowledge construction. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 36, 370–382. doi: 10.1111/jcal.12408

Zembylas, M. (2008). Adult learners’ emotions in online learning. Distance Education. 29, 71–87. doi: 10.1080/01587910802004852

Keywords: instructor presence, distance education, online education, online learning, online learners, graduate students, higher education

Citation: McNeill L and Bushaala S (2023) Meaningful connection in virtual classrooms: graduate students’ perspectives on effective instructor presence in blended courses. Front. Educ. 8:1271245. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1271245

Edited by:

Patrick R. Lowenthal, Boise State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Larisa Olesova, University of Florida, United StatesKathleen Sheridan, University of Illinois Chicago, United States

Copyright © 2023 McNeill and Bushaala. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Laura McNeill, amxtY25laWxsQHVhLmVkdQ==

Laura McNeill

Laura McNeill Saad Bushaala

Saad Bushaala