- 1Nucleus of Computational Thinking and Education for Sustainable Development (NuCES), Center for Research in Education (CIE-UMCE), Department of History and Geography, Metropolitan University of Educational Sciences, Santiago, Chile

- 2Department of Language, Literature and Social Sciences Education, Faculty of Education, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

The research presented is positioned under the issue of hate speech prevalent in society, particularly its emergence in schools. In recent years, we have witnessed the presence of a phenomenon that is not new; however, it poses challenges to the teaching and learning processes for educators. Specifically, feminist movements and those advocating for diversity and nonconformity have triggered a strong response filled with violent and discriminatory messages and actions. To obtain some answers to this challenge, a case study was conducted with 6 teachers from various schools in Chile. Semi-structured interviews were carried out to explore, from their perspectives, aspects such as the origins of hate speech, the possibilities and proposals that teachers have for creating counter-narratives against hate, the effects of hate messages from gender perspectives in their teaching practices, and finally, the processes carried out with students. Among the main conclusions, it can be mentioned that there is a violent disruption that deepens gender inequalities, a situation that is becoming normalized and is of great concern for educators. Teachers express that they lack the tools and competencies to address these problems, other than continuing with the treatment of official content.

1. Introduction

In recent years, various feminist movements have emerged in society advocating for diversity and the recognition of gender dissidence. However, hate speech has also emerged that promotes traditional and conservative practices that marginalize, violate, and exclude those who stand for diversity. Education, particularly the teaching of history and social studies, has not been immune to this problem. Teachers face complex challenges when confronting this type of language in their practice. Therefore, a qualitative case study offers teachers suggestions for addressing these classroom challenges. Six teachers were interviewed at different stages and emphasized the importance of teacher training, the influence of social media, and the development of counter-hate narratives through work with history and social studies content. The results show that teachers view these speeches as complex situations that abruptly interrupt their teaching and that they have limited resources to manage them. However, numerous opportunities exist to work toward eliminating inequalities and spaces of violence and marginalization while adopting a gendered perspective.

2. Theoretical framework

The spread of hate messages and narratives is not new in society or history. As Izquierdo Grau (2019) notes, aspects such as discrimination, violence, and marginalization, while not new, are articulated in contemporary hate speech. Emcke (2017) argues that it is complex to understand the return of narratives and actions that spread hate and violence, something that happened in the past and was thought not to happen again after all the traumatic experiences, such as the Holocaust and dictatorships. Thus, Waldron (2012) explains that hate speech aims to attack human rights and dignity. The Council of Europe (2017) defines hate speech as follows:

“The hate speech covers all forms of expression which spread, incite, promote or justify racial hatred, xenophobia, antisemitism or other forms of hatred based on intolerance, including intolerance expressed by aggressive nationalism and ethnocentrism, discrimination and hostility against minorities, and migrants and people of immigrant origin” (p. 31).

Parekh (2012) states that three characteristics can describe hate speech:

• Hate speech focuses on a particular group of people with one or more common characteristics.

• Various “undesirable” characteristics and traits are given, which are often false.

• The hated group is marginalized and suppressed. Attempts are made to ensure that they are not part of society, as their presence is perceived as violent, hostile, and unpleasant.

One of the problems society faces in the presence of hate speech is related to the “spectacle” created around the victims. The more violent and unusual the narrative or action is, the more approval and reproduction the “spectacle” receives (Emcke, 2017). As a result, groups of people with common characteristics, such as a particular culture and religion, a particular skin color, and a sexual, gender, or identity orientation that differs from the traditional one, generally receive the most hate speech (Gagliardone et al., 2015; Ortega-Sánchez et al., 2021a). Therefore, a large part of the population is in a vulnerable physical and psychological state that limits their capacities and competencies to participate in eliminating inequalities of which they are a part (Arroyo et al., 2018; Apolo et al., 2019).

Similarly, Santisteban (2017) and Arroyo et al. (2018) argue that hate speech and narratives construct an “enemy image” around the hated group. They blame the community for everything we disagree with and interpret their actions as threats to our values, identity, and way of life. The authors mentioned an earlier claim that among the characteristics that are constructed around the hated group, the following could be mentioned: (a) distrust of the group targeted by the hate narratives; (b) blaming them for everything that is not agreed upon or dislikes; (c) all actions of the group have the intention of harming the others; (d) the hated group wants to destroy our way of life; (e) everything good and evil for the group is harmful to the others; (f) empathy towards the people targeted by the hate narratives is denied. Sponholz (2016) adds that hate speech focuses on attacking individuals and communities, not their ideas and values.

Social media and traditional media are the main mechanisms for spreading such narratives. The phenomenon of globalization contributes to the rapid spread of these messages, affecting countless spaces and people (Djuric et al., 2015). This rapid spread makes dealing with hate speech a social and controversial issue, as we need to understand what is happening in classrooms concerning the presence of such speech (Barendt, 2019). The presence and massiveness of the Internet have led to the emergence of new communication spaces where hateful comments and speech that are broadcast and disseminated find an audience that instantly massifies them immediately (Gagliardone et al., 2015). These communication spaces are exacerbated by hate speech spreading anonymously and shared by communities as a common narrative. Such hate stories are accompanied by a lack of identity online. The sense of impunity, therefore, motivates them to continue their attacks (Gagliardone et al., 2015; Castellví et al., 2022).

According to Ballbé Martínez et al. (2021), an effective strategy is addressing social issues based on spreading hate speech. This strategy must necessarily be combined with education for critical and participatory citizenship. Lilley et al. (2017) note that civic education should teach ways of exploring that enable students to understand the world’s challenges from a socially responsible, critical, and ethically engaged perspective. Benejam (2002) states that social sciences instruction should focus on developing social thinking while also performing a counter-socializing task by attempting to uncover the ideological background of any social action. Pagès and Santisteban (2014), on the other hand, state that citizenship education should help provide critical analysis and reflection skills to achieve social justice by eliminating inequalities between genders, ethnicities, and classes. As Ortega-Sánchez et al. (2021b) state, citizenship is now linked to the global dissemination of information, which means that what is expressed can instantly reach different places and spaces. Ross and Vinson (2012) note that developing critical thinking should enable students to address complex and real social problems they face.

Lewison et al. (2002) suggest that four dimensions should guide citizenship education: (a) question what is established; (b) question the diversity of positions; (c) focus on sociopolitical issues; and d) promote social justice. Starting with citizenship, following Tuck and Silverman (2016), the priority must be on constructing counter-narratives to hate that promote the fight against extremism. The focus must be on human rights and social justice. Santisteban et al. (2018) explain that hate narratives can be addressed in teaching and learning social sciences through the following ideas: (a) identifying social conflicts, (b) identifying the context in which the narratives emerge, (c) identifying the actors involved, (d) reflecting on the arguments made, (e) interpreting the emotions associated with the narratives, (f) promoting empathy, (g) promoting the protection and preservation of human rights over each argument.

According to Waldron (2012), hate speech impairs human dignity and prevents people from developing recognition and diverse, plural, and particular identities outside the traditional norm. Denying identities and dissident groups on gendered grounds results in dehumanization that justifies the perpetration of violence and human rights violations (Osler, 2015; Castellví et al., 2022). Butler (2004) and Sales Gelabert (2015) agree that excluding people and their identities are directly linked to violence. As Sales Gelabert (2015) states:

“dehumanization allows, enables, and legitimizes the exercise of violence against dehumanized groups or groups excluded from the definition of the human” (p. 57).

Following Massip Sabater et al. (2021), citizenship education for constructing hate-counter-narratives can focus on Castellví et al.'s (2019) proposal. The author proposes three phases for developing critical thinking: (a) analysis and reflection on social problems and the information offered; (b) proposal of criteria based on social knowledge and the protection of democracy; and (c) participation in the defense of social justice. Ortega-Sánchez et al. (2021a) assert that, given the violence and discrimination that occur in society, it is urgent to include processes of reflection and questioning in the teaching of social sciences. This reflection and questioning would not be possible if teacher education programs did not include in their curricula and syllabi content and processes that enable teachers to incorporate such issues into teaching and learning. Ranieri (2016) notes that education is a fundamental pillar in constructing counter-narratives of hate and creating a consciousness that contributes to its eradication.

Gagliardone et al. (2015) and Osler (2015) agree that initial teacher education is essential to provide future teachers with the skills they need to work toward social change in the face of gender inequities. Gagliardone et al. (2015) argue that building counter-narratives of hate should focus on (a) critical media literacy and reflection on information, (b) global and digital citizenship education, and (c) the development of critical thinking. As Ortega-Sánchez et al. (2021b) add, teacher education must provide tools to interpret social reality and promote participation in problematic contexts, such as where hate speech is disseminated. This tool is not unproblematic, as Castellví et al. (2019) assert that emotions and feelings permeate our relationships. Indeed, much hate speech does not respond to coherent structures but reflects irrationality and is largely not a valid category for social analysis. Nevertheless, research shows that emotional literacy is generally not part of teacher education in the social sciences (Yuste Munté, 2017).

2.1. Gender perspectives, teacher training, and theoretical advancements

In social sciences education, studies by Díez Bedmar (2022), García Luque and Peinado (2015), García Luque and de la Cruz (2019), Marolla Gajardo et al. (2021), Marolla (2019a,b), and Ortega-Sánchez et al. (2021a) have focused on investigating teaching and learning processes from gender perspectives. In general, they all agree that even educational processes working from history are framed in the reproduction of patriarchal hegemonic social structures that highlight male protagonism over the inclusion of diversity (García Luque and Peinado 2015; García Luque and de la Cruz, 2019). Balteiro and Roig-Marín (2015) and Díaz de Greñu and Anguita (2017) agree that the persistence of androcentric structures in the teaching of history and social sciences, among other factors, causes the private and daily life to be undervalued and considered little relevant as knowledge of the past and present society. This undermines the protagonism of public activities such as politics, war, and the economy, where powerful men stand out (Crocco, 2008). Conversely, traditionally private life has been dominated by women and girls (Díez Bedmar, 2022).

Learning history and social sciences from gender perspectives implies a change in the epistemological understanding under which we understand knowledge structures (Ortega-Sánchez and Olmos Vila, 2019). For this, critical thinking must be a fundamental objective in learning processes. This would mean, that students can analyze and understand the sources and purposes of historical content and knowledge. That is, the absence and ignorance we have about the actions, narratives, and history of sexual and gender dissidences, does not obey the lack of sources or information, but rather a political and ideological decision, from patriarchal structures, about who we grant a past and present history (Wiley et al., 2014).

It is essential that teacher training programs, therefore, undergo a reformulation that allows them to provide the necessary competencies, tools, and knowledge to future teachers so that they not only include new narratives and protagonists (Heras-Sevilla et al., 2021; Marolla Gajardo et al., 2021), but also be agents that contribute to social transformation in terms of justice (Santisteban, 2017; Massip Sabater and Castellví Mata, 2019). Muzzi et al. (2019) propose that the inclusion of women, dissidences, and other marginalized and silenced groups implies a deconstruction of hegemonic male normalcy patterns in favor of the systematic construction of a new normality where everyone who has been silenced by tradition has a place. Fontana (2002) says that it is imperative to overcome the excessive protagonism of dominant, powerful, and white men in developed societies, by constructing new historiographies that recognize the historical experiences of all those who have been invisibilized. Thus, educational spaces, in general, are one of the most affected fronts by marginalization situations, since it is where social and cultural patterns are produced and reproduced that will then be transmitted to society (García Luque and de la Cruz, 2017, 2019; de la Cruz et al., 2019).

If new identities are included in the teaching and learning processes, it is necessary to question who the protagonists will be included in the new narratives and, in particular, which type of people will be targeted to promote a teaching and learning towards diversity (Massip Sabater and Castellví Mata, 2019). In other words, an inclusion from a critical perspective involves questioning which identities will be given a voice, and therefore, how recognition policies will be worked on Díez Bedmar (2022). As Santisteban and González-Monfort (2019) and Massip Sabater and Castellví Mata (2019) say, it is convenient to consider the intersectional analysis as an axis that would allow us to understand the complexities we face in the fight against gender inequalities, as well as other types of social problems that occur in determined contexts.

It is not a matter of including in educational structures more historical contents and processes about women, diversities and gender dissidences (Heras-Sevilla et al., 2021). Ortega-Sánchez (2020) and Díaz de Greñu and Anguita (2017) agree that the goal is to rethink the entire educational process, from the curriculum, programs, to the contents and practices carried out by the teaching staff, in favor of a recognition policy towards diversities as agents and protagonists of a history that claims their narratives. Other discourses must be created that promote the deconstruction of inequalities and that cause the installation of new models of expression of diverse identities (De Lauretis, 2015). Heras-Sevilla et al. (2021) propose that the work mentioned before follows the stages of what they call “gender technology,” where: (a) gender is a representation of society; (b) gender representations have performative categories; (c) gender is constantly being constructed and; (d) gender can be deconstructed.

As García Luque and de la Cruz (2017, 2019) and García Luque and Peinado (2015) say, teacher training from gender perspectives must equip future teachers with a “gender awareness.” In other words, the competence to be able to analyze and reflect on their own sexist and discriminatory patterns, and at the same time, on how such practices are translated into their daily life, work, and the rest of people who are part of society. This is possible by having a citizenship education that critically reflects on diverse identities and their participation and action in democratic construction (Triviño Cabrera and Chaves Guerrero, 2020). Teachers must recognize that the school space is a place of permanent conflict for the ideological and political control of the course of society (Bartual-Figueras et al., 2018), but at the same time it offers the possibilities to develop critical pedagogies that fight against sexism and propose social justice as a goal (Saleiro, 2017).

To promote a critical and participatory citizenship education, one of the minimum requirements is that the teaching of history and social sciences should provide students with references and protagonists with whom to identify (Marolla, 2019a,b; Marolla Gajardo et al., 2021). However, the solution does not pass through including a curriculum and programs saturated with contents, new knowledge about women, dissidents, ethnicities, among others (Pagès, 2018). The path is to deconstruct the entire educational and training process, delivering epistemologies that enable students to have the tools to understand society’s problems, and in that way, participate with the goal of transforming inequalities (Molet Chicot and Bernard Cavero, 2015; Ortega-Sánchez and Pagès, 2018; Crocco, 2019; Heras-Sevilla et al., 2021).

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Study design

A qualitative methodology was used with an interpretive approach based on a phenomenological-hermeneutic design (van Manen, 2003; Ricoeur, 2006). These perspectives are useful because the construction of reality is governed by the multiple views of different individuals (González-Monteagudo, 2000–2001). The aim is to generate an interpretation of an understudied phenomenon where thoughts, values, and beliefs are interwoven to shape reality (Gutiérrez, 2017). The hermeneutic perspective is developed by searching for the experiences and their meanings (Ricoeur, 2006). This perspective is included in phenomenological definitions, highlights subjectivities, and privileges the understanding of reality through the meanings that emerge from the associated concepts (van Manen, 2003). It should be noted that for Ricoeur (2006), the hermeneutic process involves both understanding and explaining. In other words, interpretive design with a phenomenological focus provides the opportunity to examine complex experiences so that we can understand the world through understanding those experiences.

The study consisted of three phases following the study by Miles et al. (2014). The stages were: (a) reducing the information, establishing categories and codes that allow the creation of themes; (b) processing the information by assigning relationships between themes and categories; (c) interpreting the categories and themes in light of the study’s goals.

3.2. Instruments and participants

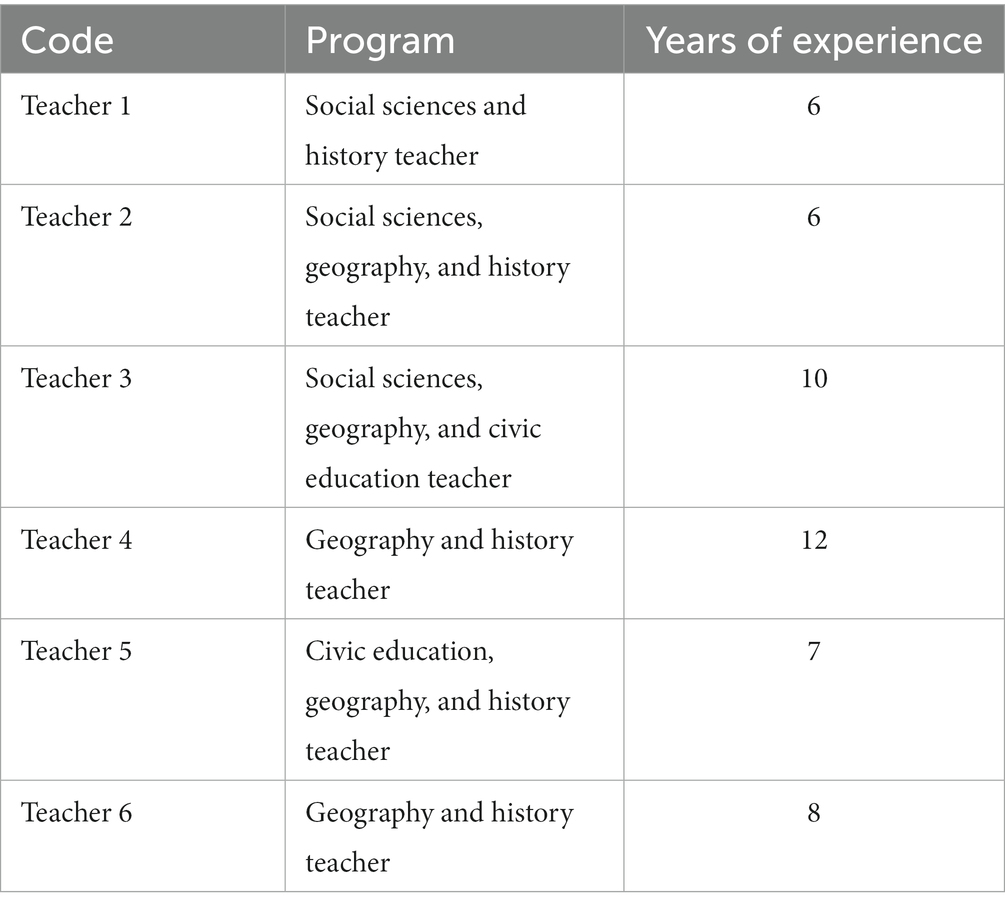

Participants were selected using criteria based on informant characteristics and study objectives (Bisquerra and Alzina, 2004). The criteria were: (a) more than 5 years of teaching experience; (b) coming from history, social science, or geography training programs; (c) having knowledge at the user-level knowledge of social media platforms; and (d) being willing to participate in the different phases of the study. The main characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

The instruments used were the semi-structured interview and the focus group. These instruments were deemed the most suitable for establishing a conversational and trusting atmosphere that would allow the participants to express their ideas freely (Marshall and Rossman, 2016). An expert judge validation was carried out (10), who contributed various improvement ideas. In addition, a pilot test was applied to students who were not part of the study, as defined by Birt et al. (2016). The information was processed using the Atlas.ti v.8 software for qualitative data analysis.

3.3. Data analysis

The information was analyzed through different stages, following the guidelines of Flick (2004) and Kuckartz (2014): (a) code and category collection; (b) joint interpretation of codes and categories, establishing groupings by theme; (c) theme reduction through data relationships; (d) final categorization and interpretation. To understand the results, an analysis matrix and theme organization was developed based on its relationship with the study objectives (Flick, 2004). Following Richards and Lockhart (2008), the defined stages and themes can be summarized as: (a) definition of hate speech; (b) presence or absence of hate speech in society and education; (c) interactions and manifestations of students where hate speech emerges; (d) possibilities and limitations for working with hate speech in teacher education. The obtained data was transcribed faithfully to the words of the participants (Flick, 2004). Categories from gender perspectives are not included, since such a construct is included implicitly (and often explicitly) in the hate speeches that are expressed. That is, a gender category will not be worked on, since expressions of hate contain and manifest not only gender discrimination, but also class, race, ethnicity, religion, among others.

3.4. Ethical criteria

The definitions outlined in the Helsinki Declaration were implemented, ensuring: (a) informing participants of the data being worked on; (b) guaranteeing anonymity and confidentiality to individuals; (c) sharing the data with participants before it is published so that they can express their stance on suppressing or changing something said (Simons, 2009; Birt et al., 2016).

4. Results

The results will be presented under two large sections: “Initial teacher training to address hate speech” and “the influence of social networks on the production of hate speech.” They are organized in this way since the categories stated in section 3.3 are contained in the proposed topics. At times, such categories are intertwined in their themes and contents, so to offer an orderly, clear and non-repetitive presentation of the results, it is advisable to construct two large themes where those categories can be seen contained.

4.1. Initial teacher education to address with hate speech

Teacher 1 argues that their training programs have not provided them, as teachers, with the necessary competencies to work from gender perspectives. This becomes even more complex if it is added that there is no initiative from the Chilean Ministry of Education to include such aspects in future teacher education programs:

“Then, it is difficult when from Mineduc, from the State, there is no initiative, or there is not a greater interest in generating this training that we lacked in university” (Teacher 1-Interview).

From the teachers’ narratives, it is possible to recognize that they consider the breadth of social networks to be a space with educational potential, provided that the teachers who use them make the appropriate educational decisions to determine the purposes of their use:

“As I tell you, it can be used as a tool that facilitates learning or, on the contrary, as a tool where prejudices are promoted, where hate speech is promoted” (Teacher 4- Interview).

An important aspect raised by teacher 5 is related to continuous and professional training. In this sense, he considers it fundamental to promote that teachers can be updated in new educational dynamics and knowledges, such as the social problems of the 21st century and the strategies and paths to work with them in the classrooms. Teacher 5 adds that it is fundamental to generate non-traditional learning processes that pursue the development of skills and competencies such as critical thinking, argumentation, distinction between facts and opinions, as well as a reflective reading on social structures:

“we must develop critical thinking in students, for this we have to work with sources of information, and distinguish facts from opinions or contrast different sources, I think it is important to talk about hate speech, fake news too, and other aspects that are relevant in the 21st century” (Teacher 5-Interview).

Conflicts should be worked from the problematization of social structures, as well as social and controversial issues that can be discussed in the classrooms. In effect, a structural reform of the curriculum should be promoted, as well as such learning instances being meaningful and promoting student participation:

“in addition to promoting that girls and boys get involved in the learning processes. I think it is important to bring the conflicts and fix the conflicts in the classroom so that children can appropriate them, but feel the need to participate, comment, express an opinion, generate reflection instances and look for alternative solutions to what is established” (teacher 5-Interview).

In the narratives of the interviewees, continuing education appears as a relevant element in relation to the approach of hate speech from gender perspectives. A first aspect to highlight with respect to continuing education is related to the relevance that some teachers assign to working with hate speech from gender perspectives in the education of girls, boys and young people in school:

“Even so, I think it is very necessary that we train ourselves even more in all these topics, especially with feminism, with sexual dissidences, which we will see much more in our practices” (teacher 2-Focus Group).

Regarding continuing teacher education, teachers understand that it is necessary to access educating instances on feminism and sexual dissidence; educating on the knowledge and development of teaching tools that facilitate approaching their classes from a gender perspective; education on how to act from a work and administrative standpoint in potential situations of violation of rights related to this dimension, among others. For some teachers, their continuing education is a personal matter, which develops them both as individuals and professionals, while also helping students and their families to face processes of gender identity definition.

In this line, some teachers indicate that during their initial teacher education, there were no adequate and sufficient opportunities to learn about gender issues. Without the necessary tools to work from and towards social justice, the teaching staff agrees that their classes could become potential sources of elaboration and circulation of hate speech from gender perspectives:

“Regarding teacher education, I think it was a bit deficient and it should be like a process throughout life […] in any profession, it is constant training” (teacher 5-Focus Group).

Regarding possibilities to consider for the development of continuing education processes in these topics, some teachers indicate that it is a cross-sectional responsibility. They argue that there are spaces and possibilities offered by the social environment for the teaching staff to choose to educate themselves or increase their knowledge about gender, whether for the improvement of their educational practices or for the improvement in their daily lives:

“there are a lot of feminist organizations or sexual diversity organizations that do free courses to instill these themes in schools” (teacher 1-Interview).

4.2. The influence of social networks on the production of hate speech

Teacher 1 states that social networks generate an ideal space for different speeches to be emitted, especially those that manifest situations of hate. They affirm that the comments are directed towards populations and communities traditionally discriminated and marginalized, all from the anonymity offered by social networks: “all these opinions and evaluations, or judgments, about women, children, foreigners, intensify with social networks, where there are no faces, no physical contact, a contact where we can actually sit down and talk.

“Hate intensifies more when we are not face-to-face” (teacher 1-Interview).

With regards to this, teacher 3 states that social networks are one of the main spaces from which hate speech is produced and reproduced. Even in such spaces, social problems are generated, such as harassment:

“I think the internet and social networks are a main factor of the speeches, or of everything that can be delivered in the lives of young people, through hate speech, words that can affect another, but in a harmful way” (teacher 3-Focus Group).

Teacher 5 states that social networks undoubtedly have a fundamental influence in the construction and reproduction of hate speech. For this teacher, the key is to work from the promotion of critical thinking, and in activities such as the distinction between facts and opinions, being able to delve into analysis, reflection, and ideological identification strategies:

“it is important to promote critical thinking, to work on what distinguishes data from opinions, facts from opinions, so that students can identify which things narrated there are real, are facts, and which are ideas made by people or the editorial line” (teacher 5-Focus Group).

Regarding the content of social media, the participants recognize that it is a factor that students appropriate and reproduce:

“When I’ve asked where they get that opinion from. They mention a social network or a publication referring to a social network to support their opinion” (teacher 2-Interwiew).

Therefore, students establish trust relationships with the content and information distributed on the networks:

“This proximity to social networks in the digital era promotes a certain uncritical acceptance of everything that is published there” (teacher 3-Interview).

On the other hand, the teaching staff references the pandemic situation as a space that potentiated the emergence of hate speech from the use of social media. The shift from daily physical contact to permanent digital contact would have allowed the emergence of scenarios of violence that found a suitable space in the anonymity of the turned off cameras and the use of chats for communication:

“I think that social networks, no matter how well used they are, tend to a certain extent to deliver words, images, etc., that may harm other people. And since everything around social networks is hidden behind a screen, these situations that generate hatred are developed, dilated, and sharpened” (teacher 3-Interview).

From the teachers’ narratives, it can be inferred that certain resources present on social networks, such as memes, incite hatred towards certain groups, shaping a certain valuation towards them. One of the participating teachers indicates that for him, it is easy to see how certain memes or videos are influencing the students’ view of, for example, sexual minorities or inclusive language, since these go viral on social networks:

“Sometimes I find students repeating, replicating these discourses, replicating this ridicule” (teacher 4-Focus Group).

Due to the algorithms of social media, it’s very likely that a student who has a discriminatory view towards minority groups will constantly be exposed to similar views from other people through social media, which would help reinforce their belief that their view is correct:

“On the internet, people are constantly sharing these hate speeches, because in the end, that’s how social media is functioning today, these are speeches that generate more likes, […] in some way, students are exposed to these hate speeches” (teacher 6-Focus Group).

In this regard, the teaching staff mentions that social media is used to help students identify hate speech through the investigation of news that show different perspectives. The implemented educational strategy allows students to analyze the same news and determine how the journalist or media editorial promotes or not a gender perspective. Recognizing the potential for citizens to learn to identify these differences in the information we interact with on a daily basis, and the need to recognize hate speech. Similarly, teacher 4 states that schools face many complexities in confronting hate speech produced by boys and girls. Their comments are directed at the influence of the family in the production and reproduction of hate speech, both from within the family itself and from private use of social media:

“Hate speech is the expression of what they bring from their own home related to social media and their family” (teacher 4-Interview).

5. Discussion

The results highlight the need for collaborative work within schools, supported by multidisciplinary teams that accompany the work of teachers, in order to raise counter-hegemonic discourses that can generate changes in some students’ representations of gender. Recognizing the shortcomings in working from a gender perspective, the option to transform these issues into axes within the decision-making processes within schools emerges.

On the other hand, teachers indicate that there are few formal training opportunities on gender issues. They consider it crucial to be able to count on updates that allow them to conceptually and pedagogically appropriate the theme. From their own accounts, the proposal emerges that public policy must make decisions that allow instruction on gender issues to be included on the agenda of public policies.

Continuing teacher education is what has allowed some of the participants to gradually build a clearer vision of how to approach hate speech issues from a gender perspective. To some extent, the credentials that are evident from the continuing teacher education promote greater empowerment when making decisions about reinterpreting and implementing the prescribed curriculum.

In turn, post-degree education have allowed them to build a different relationship with the curriculum. To some extent, the maturation in the relationship they establish with it has allowed them to know it better and to detect those spaces and opportunities that open up for addressing social issues. A critical gaze from teachers towards initial training is evident. The participants agree that this would allow explaining the traditionality of the educational system and the absence of teaching social and controversial issues.

Deficient initial education is interpreted as one of the causes that leads this type of teacher to have and maintain a traditional perspective of teaching, not promoting innovation in the approach of their classes, and leaving out topics that would allow analyzing society. Rather, what prevails is a teaching focused on repetition and memorization based on white and Western male characters with some type of political, economic, and/or military power.

Despite the limitations, teachers identify a series of strategies that contribute to the development of attitudes of appreciation of diversities and sexual and gender dissidences. Thus, the participants affirm that, in order to work with hate speech, it is necessary to learn to identify it through a reading between the lines of the information with which we relate daily. This first learning focused on oneself as an educator who recognizes that his/her role must contribute to promoting a human rights-centered education is what allows us to think about proposals for addressing hate narratives.

Participating teachers argue that they must be attentive to situations that occur in the classroom and that could evidence the emergence of prejudices, stereotypes, or violation of the rights of some groups, instead of ignoring these situations, or just punishing those who are acting in a discriminatory or offensive manner. The path is to propose learning situations that contribute to transforming inequalities, encourage the development of critical thinking, and thus generate counter-hate narratives.

The resources present on social networks are also seen as an opportunity to work on hate speech. It is useful to work with the content of social networks as sources of information, to analyze and contrast them. This is a useful strategy, for example, to teach children to differentiate between facts and opinions and help them recognize hate speech.

National or international contingency situations are also valued as a key resource for addressing hate speech. It is important to note that teaching from social and controversial issues motivates students, as they understand that situations experienced in daily life can enter the classroom to be analyzed, seek their origins, and in turn, propose possible solutions.

The problem faced by educational processes and the teaching of social sciences is related to the phenomenon of globalization and social networks. In addition, civic education is a disputed field in terms of the formation of values and behaviors (Campos Zamora, 2018). Considering what Cabo Isasi and García Juanatey (2016) say, hate speech is expanding more and more quickly, both in everyday social circles and in audiovisual media such as social networks. As a consequence, it is urgent to propose civic education as an educational axis in the teaching of social sciences (Izquierdo Grau, 2019). This author adds that students have difficulties to face and understand hate narratives. This is due to the influence that networks have on the construction of their concepts, where the veracity and reliability of sources is not analyzed.

Butler (2004) and Fraser (2019) agree that exclusion and the inability to generate identities causes the denial of recognition policy positioning. This is because only what is perceived with the ability to assume such a social status can be recognized. Hate speech, in that way, denies personal stories, emotions, and empathy (Sales Gelabert, 2015).

In the context of deconstructing the social structures that have produced and reproduced inequalities, it is worth mentioning Santos and Aguiló Pons (2019), who state that any change that is desired must first position a struggle against the patriarchal, colonial, and capitalist system, from where most of the inequalities arise and are generated. Therefore, caution must be taken in the way in which new protagonists are included, as if it is done within existing structures, only social hegemonies will be reinforced (Díez Bedmar, 2022). Massip Sabater and Castellví Mata (2019) write:

“The diversification of protagonists makes sense when we can aspire to the construction of a joint narrative that understands all people and communities as social agents and attends to their experiences, concerns, and circumstances” (pp. 146–147).

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the datasets for this article are not publicly available due to concerns regarding participant anonymity. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to amVzdXMubWFyb2xsYUB1bWNlLmNs.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee USACH institutional ethics committee N°248/2023 on 26/04/2023. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JM-G: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JC-M: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by Fondecyt Project 11231022 “Hate speech from a gender perspective through contingency situations in initial history teacher training programs in Chile”.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Apolo, M., Calderón, C., and Amores, J. (2019). El discurso del odio hacia migrantes y refugiados a través del tono y los marcos de los mensajes en Twitter. Rev. Asoc. Española Invest. Comun. 6, 361–384. doi: 10.24137/raeic.6.12.2

Arroyo, A., Ballbé, M., Canals, R., García, C. R., Llusà, J., López, M., et al. (2018). “El discurso del odio: Una investigación en la formación inicial” in Buscando formas de enseñar: Investigar para innovar en didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales. eds. E. E. López, C. R. Torres, G. Ruíz, and M. Sánchez Agustí (Valladolid: AUPDCS), 413–424.

Ballbé Martínez, M., González Valencia, G. A., and Ortega Sánchez, D. (2021). Invisibles y ciudadanía global en la formación del profesorado de Educación Secundaria. Bellaterra 14, 3–15. doi: 10.5565/rev/jtl3.910

Balteiro, I., and Roig-Marín, A. (2015). “Reflexiones sobre la integración de cuestiones de género en la enseñanza universitaria” in Investigación y propuestas innovadoras de Redes UA para la mejora docente. eds. E. J. D. Álvarez Teruel and M. T. T. Ybáñez (ICE), Alicante: Universidad de Alicante. 851–870.

Barendt, E. (2019). What is the harm of hate speech? Ethical Theory Moral Pract. 22, 539–553. doi: 10.1007/s10677-019-10002-0

Bartual-Figueras, M. T., Carbonell-Esteller, M., Carreras-Marín, A., Colomé-Ferrer, J., and Turmo-Garuz, J. (2018). La perspectiva de género en la docencia universitaria de Economía e Historia. Rev. d’Innovació Docent Univ. 10, 92–101. doi: 10.1344/RIDU2018.10.9

Benejam, P. (2002). La didáctica de las ciencias sociales y la formación inicial y permanente del profesorado. Enseñanza de las ciencias sociales: revista de investigación 1, 91–95. Available at: https://raco.cat/index.php/EnsenanzaCS/article/view/126133

Birt, L., Scott, S., Cavers, D., Campbell, C., and Walter, F. (2016). Member checking: a tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qual. Health Res. 26, 1802–1811. doi: 10.1177/1049732316654870

Bisquerra, R., and Alzina, R. B. (2004). Metodología de la investigación educativa. Spain: Editorial La Muralla.

Cabo Isasi, A., and García Juanatey, A. (2016). El discurso del odio en las redes sociales: un estado de la cuestión. Ajuntament de Barcelona. Available at: http://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/bcnvsodi/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Informe_discurso-del-odio_ES.pdf

Campos Zamora, F. (2018). Existe un derecho a blasfemar? Sobre libertad de expresión y discurso del odio. Doxa. Cuadernos de Filosofía del Derecho 41, 281–295. doi: 10.14198/DOXA2018.41.14

Castellví, J., Massip, M., and Pagès, J. (2019). Emociones y pensamiento crítico en la era digital: Un estudio con alumnado de formación inicial. REIDICS: Revista de Investigación en Didáctica de las. Ciencias Soc. 5, 23–41. doi: 10.17398/2531-0968.05.23

Castellví, J., Massip Sabater, M., and González-Valencia, G. A. (2022). Future teachers confronting extremism and hate speech. Humanit. Soc Sci. Commun. 9:201. doi: 10.1057/s41599-022-01222-4

Council of Europe (2017). We can! Taking action against hate speech through counter and alternative narratives. Strasbourg: European Youth Centre.

Crocco, M. (2008). “Gender and sexuality in the social studies” in Handbook of research in social studies education. eds. L. Levstik and C. A. Tyson (New York: Routledge), 172–196.

de la Cruz, A., Díez Bedmar, M. C., and García Luque, A. (2019). “Formación de profesorado y reflexión sobre identidades de género diversas a través de los libros de texto de Ciencias Sociales,” in Enseñar y aprender didáctica de las ciencias sociales: La formación del profesorado desde una perspectiva sociocrítica. Eds. M. J. Hortas, A. Dias D’Almeida, and N. de Alba Fernández. (Lisbon: AUPDCS-Politécnico de Lisboa), 273–287.

Díaz de Greñu, S., and Anguita, R. (2017). Estereotipos del profesorado en torno al género y a la orientación sexual. Rev. Elect. Int. Form. Prof. 20, 219–232. doi: 10.6018/reifop/20.1.228961

Díez Bedmar, M. C. (2022). Feminism, intersectionality, and gender category: essential contributions for historical thinking development. Front. Educ. 7, 1–8. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.842580

Djuric, N., Zhou, J., Morris, R., Grbovic, M., Radosavljevic, V., and Bhamidipati, N. (2015). “Hate speech detection with comment embeddings” in WWW ‘15 companion: Proceedings of the 24th international conference on world wide web. eds. A. Gangemi, S. Leonardi, and A. Panconesi (New York: Association for Computing Machinery)

Fraser, N. (2019). La justicia social en la era de las «políticas de identidad»: Redistribución, reconocimiento y participación. Apuntes Invest. CECYP 2, 17–36.

Gagliardone, I., Gal, D., Alves, T., and Martínez, G. (2015). Countering online hate speech. Paris: UNESCO.

García Luque, A., and de la Cruz, A. (2017). “Coeducación en la formación inicial del profesorado: Una estrategia de lucha contra las desigualdades de género” in Investigación en didáctica de las ciencias sociales. Retos preguntas y líneas de investigación (pp. 133–142). eds. R. Martínez, R. García-Moris, and C. R. García Ruíz (Córdoba: AUPDCS-Universidad de Córdoba)

García Luque, A., and de la Cruz, A. (2019). La didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales y la construcción de masculinidades alternativas: Libros de texto a debate. Clío: History and History Teaching, 99–115.

García Luque, A., and Peinado, M. (2015). LOMCE: ¿es posible construir una ciudadanía sin la perspectiva de género? Iber: Didáctica de las ciencias sociales. Geografía Hist. 80, 65–72.

González-Monteagudo, J. (2000–2001). El paradigma interpretativo en la investigación social y educativa. Cuestiones pedagógicas: Revista de ciencias de la educación. 15, 227–246.

Gutiérrez, L. (2017). Paradigmas cuantitativos y cualitativos en la investigación socio-educativa: Proyección y reflexiones. Paradigma 14, 7–25. doi: 10.37618/PARADIGMA.1011-2251.1996.p7-25.id181

Heras-Sevilla, D., Ortega-Sánchez, D., and Rubia Avi, M. (2021). Conceptualización y reflexión sobre el género y la diversidad sexual. Hacia un modelo coeducativo por y para la diversidad. Perfiles Educ. 43, 148–165. doi: 10.22201/iisue.24486167e.2021.173.59808

Izquierdo Grau, A. (2019). Literacidad crítica y discurso del odio: Una investigación en Educación Secundaria. REIDICS. Rev. Invest. Didáct. Cien. Soc. 5, 42–55. doi: 10.17398/2531-0968.05.42

Kuckartz, U. (2014). Qualitative text analysis: a guide to methods, Practice & Using Software. SAGE Publications.

Lewison, M., Flint, A. S., and Van Sluys, K. (2002). Taking on critical literacy: the journey of newcomers and novices. Lang. Arts 79, 382–392.

Lilley, K., Barker, M., and Harris, N. (2017). The global citizen conceptualized. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 21, 6–21. doi: 10.1177/1028315316637354

Marolla, J. (2019a). La ausencia y la discriminación de las mujeres en la formación del profesorado de historia y ciencias sociales. Rev. Elect. Educ. 23, 1–21. doi: 10.15359/ree.23-1.8

Marolla, J. (2019b). La inclusión de las mujeres en las clases de historia: Posibilidades y limitaciones desde las concepciones de los y las estudiantes chilenas. Rev. Colomb. Educ. 1, 37–59. doi: 10.17227/rce.num77-6549

Marolla Gajardo, J., Castellví Mata, J., and Mendonça dos Santos, R. (2021). Chilean teacher educators’ conceptions on the absence of women and their history in teacher training programmes. A collective case study. Soc. Sci. 10, 106–125. doi: 10.3390/socsci10030106

Marshall, C., and Rossman, G. (2016). Designing qualitative research. 6th Edition: SAGE, Thousand Oaks.

Massip Sabater, M., and Castellví Mata, J. (2019). Poder y diversidad. Los aportes de la Interseccionalidad a la didáctica de las ciencias sociales. Clío 45, 139–154. doi: 10.26754/ojs_clio/clio.2019458646

Massip Sabater, M., Santisteban, A., and González, N. (2021). “Els contra-relats de l’odi: Un estudi amb professorat en formació” in El futur comença ara mateix. L’ensenyament de les ciències socials per interpretar el món i actuar socialment (Barcelona: UAB-GREDICS Adjuntament de Barcelona), 149–163.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., and Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative Data Analysis. A Methods Sourcebook. Sage

Molet Chicot, C., and Bernard Cavero, O. (2015). Políticas de género y formación del profesorado: Diez propuestas para un debate. Temas Educ. 21, 119–129.

Muzzi, S., Tosello, J., and Santisteban, A. (2019). La perspectiva de género en los currículos de historia y ciencias sociales de Italia y Argentina: Una reflexión para la formación del profesorado. In M. J. Hortas, A. Dias D’Almeida, and N. Alba-Fernándezde (Ed.), Enseñar y aprender didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales: la formación del profesorado desde una perspectiva sociocrítica (pp. 234–242). Lisbon: AUPDCS.

Ortega-Sánchez, D. (2020). “Problemas sociales, identidades excluidas y género en la enseñanza de la Historia” in Lección inaugural del curso académico 2020–2021 (Burgos: Universidad de Burgos)

Ortega-Sánchez, D., and Olmos Vila, R. (2019). Historia enseñada y género: Variables sociodemográficas, nivel educativo e itinerario curricular en el alumnado de Educación Secundaria. Clío: History and History Teaching, 83–98.

Ortega-Sánchez, D., and Pagès, J. (2018). Género y formación del profesorado: Análisis de las Guías Docentes del área de Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales. Cont. Educ. Rev. Educ. 21, 53–66. doi: 10.18172/con.3315

Ortega-Sánchez, D., Pagès, J., Massip Sabater, M., Santisteban, A., and González, N. (2021a). “Influencia de las emociones en los relatos sociales sobre las diversidades de género en Twitter: Un análisis desde el profesorado en formación” in El futur comença ara mateix. L’ensenyament de les ciències socials per interpretar el món i actuar socialment. eds. M. Massip Sabater, N. González, and A. Santisteban (Barcelona: UAB-GREDICS Adjuntament de Barcelona), 313–321.

Ortega-Sánchez, D., Pagès, J., Quintana, J., Sanz de la Cal, E., and Anuncibay, R. (2021b). Hate speech, emotions and gender identities: a study of social narratives on twitter with trainee teachers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:4055. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18084055

Osler, A. (2015). Human rights education, postcolonial scholarship and action for social justice. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 43, 244–274. doi: 10.1080/00933104.2015.1034393

Pagès, J. (2018). Aprender a enseñar historia. Las relaciones entre la historia y la historia escolar. Trayect. Univ. 4, 53–59.

Pagès, J., and Santisteban, A. (2014). “Una mirada desde el pasado al futuro en la didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales” in Una mirada al pasado y un proyecto de futuro: investigación e innovación en didáctica de las ciencias sociales. ed. J. P. I. A. Santisteban, vol. 1. 1st Edn. (Servei de publicacions de la UAB), 17–39.

Parekh, B. C. (2012). Hate speech: is there a case for banning hate speech? Public Policy Res. 12, 213–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1070-3535.2005.00405.x

Ranieri, M. (2016). Populism, media and education: Challenging discrimination in contemporary digital societies. London & New York: Routledge.

Richards, J. C., and Lockhart, C. (2008). Estrategias de reflexión sobre la enseñanza de idiomas. Madrid: Edinumen.

Ricoeur, P. (2006). Teoría de la interpretación. Discurso y excedente de sentido Siglo XXI Editores. New York: Universidad Iberoamericana.

Ross, E. W., and Vinson, K. D. (2012). La educación para una ciudadanía peligrosa. Enseñanza de las Ciencias Soc. 11, 73–86.

Sales Gelabert, T. (2015). Lo humano, la deshumanización y la inhumanidad. Apuntes filosófico-políticos para entender la violencia y la barbarie desde. J. Butler. Análisis. Revista de investigación filosófica 2, 49–61. doi: 10.26754/ojs_arif/a.rif.20151922

Saleiro, S. P. (2017). Diversidade de género na infância e educação: contributos para uma escola sensível ao (trans) género. Ex Aequo 36, 149–165. doi: 10.22355/exaequo.2017.36.09

Santos, B. d. S., and Aguiló Pons, A. (2019). Aprendizajes globales: Descolonizar, desmercantilizar y despatriarcalizar desde epistemologías del Sur. Editorial Icaria.

Santisteban, A. (2017). “La investigación sobre la enseñanza de las ciencias sociales al servicio de la ciudadanía crítica y la justicia social” in Investigación en didáctica de las ciencias sociales. Retos preguntas y líneas de investigación. eds. E. R. Martínez Medina, R. García-Moris, and C. R. G. Ruíz (Córdoba: AUPDCS- Ediciones Universidad de Córdoba), 558–567.

Santisteban, A., Arroyo, A., Ballbé, M., Canals, R., García, C. R., Llusà, J., et al. (2018). “El Discurso del Odio: Una investigación en la formación inicial” in Buscando formas de enseñar: Investigar para innovar en Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales. eds. E. López, C. R. García, and M. Sánchez (Universidad de Valladolid / AUPDCS), 423–434.

Santisteban, A., and González-Monfort, N. (2019). Education for citizenship and identities. In J. Á. Pineda-Alfonso and N. Alba-Fernáde(Ed.). Handbook of research on education for participative citizenship and global prosperity (pp. 551–567). London & New York: IGI Global.

Sponholz, L. (2016). Islamophobic hate speech: what is the point of counter-speech? The case of Oriana Fallaci and the rage and the pride. J. Muslim Minority Affairs 36, 502–522. doi: 10.1080/13602004.2016.1259054

Triviño Cabrera, L., and Chaves Guerrero, E. (2020). Cuando la Postmodernidad es un metarrelato más, ¿en qué educación ciudadana formar al profesorado? REIDICS. Rev. Invest. Didáct. Cien. Soc. 7, 82–96. doi: 10.17398/2531-0968.07.82

Tuck, H., and Silverman, T. (2016). The counter-narrative handbook. Institute for Strategic Dialogue: London.

Wiley, J., Steffens, B., Britt, M. A., and Griffin, T. D. (2014). Writing to learn from multiple-source inquiry activities in history. Brill.

Yuste Munté, M. (2017). L’empatia i l’ensenyament-aprenentatge de les Ciències Socials a l’Educació Primària a Catalunya. Un estudi de cas [Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona]. En TDX (Tesis Doctorals en Xarxa). Available at: http://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/402238

Keywords: initial teacher education, gender, hate speech, inequality, social studies education

Citation: Marolla-Gajardo J and Castellví-Mata J (2023) Transform hate speech in education from gender perspectives. Conceptions of Chilean teachers through a case study. Front. Educ. 8:1267690. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1267690

Edited by:

Delfín Ortega-Sánchez, University of Burgos, SpainReviewed by:

Noelia Pérez-Rodríguez, University of Seville, SpainNicolás De-Alba-Fernández, Sevilla University, Spain

Copyright © 2023 Marolla-Gajardo and Castellví-Mata. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jesús Marolla-Gajardo, amVzdXMubWFyb2xsYUB1bWNlLmNs

Jesús Marolla-Gajardo

Jesús Marolla-Gajardo Jordi Castellví-Mata

Jordi Castellví-Mata